Abstract

The objective of the review was to explore the relevance of the relationship of compassion and attachment to mental health. APAPsycInfo, APAPsycArticles, CINAHL, MEDLINE, Social Science Database, Sociology Database, PTSDpubs, Pubmed, and Web of Science were searched from their inception until November 9, 2021. Peer-reviewed empirical studies exploring the compassion–attachment relationship in individuals with mental health difficulties through outcome measures were included. Studies were excluded if non-empirical, with non-clinical/subclinical samples, in a language other than English and if they did not consider the compassion–attachment relationship. Risk of bias was assessed through The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale and the Downs and Black Checklist. Seven eligible studies comprising 4839 participants were identified, with low to moderate risk of overall bias. Findings indicated a more straightforward relationship between self-compassion and secure attachment and confirmed the relevance of compassion and attachment to psychological functioning. Limitations concerned study design, the use of self-report measures, and low generalisability. While suggesting mechanisms underpinning compassion and attachment, the review corroborates the role of secure attachment and self-compassion as therapeutic targets against mental health difficulties. This study is registered on PROSPERO number CRD42021296279.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Conceptualised as an emotion regulation framework, attachment theory posits that individuals’ intrapersonal and interpersonal relational styles develop from internalised experiences with a primary caregiver (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019). Internal working models of the self (e.g. lovable/unlovable), others (e.g. trustworthy/untrustworthy, rejecting) and relationships shape information processing and interpersonal functioning (Mallinckrodt, 2010). As opposed to attachment security, which indicates the ability to create interdependent relationships and presume a positive working model of self and others, attachment insecurity may signal fears of abandonment and rejection or difficulties in balancing relational intimacy and autonomy (Miljkovitch et al., 2015). Specifically, literature on attachment theory has identified: an anxious/preoccupied style with a negative working model of self and a positive working model of others; an avoidant/dismissive style with a positive working model of self and a negative working model of others; an avoidant/fearful style with a negative working model of self and others; and a disorganised style which is a conceptually and clinically different style from all the rest and is expressed through inconsistent strategies in managing distress because of unresolved loss or trauma in the relationship with caregivers (Tironi et al., 2021).

Clinically, early experiences related to the lack of caring and responsive environments overstimulate the neural connections of the threat system, which impairs the development of compassion in adulthood (Gilbert, 2020). The therapeutic relationship arguably functions as an attachment bond (Bowlby, 1988) wherein the client considers the therapist as a wiser figure, seeks relational proximity, relies on the therapist as a safe haven at times of psychological distress, receives the therapist as a secure base towards psychological growth, and experiences separation anxiety at times of unavailability, breaks or endings (Mallinckrodt, 2010). If security-based strategies fail to meet their attachment needs, clients can resort to hyperactivating strategies (e.g. magnifying interpersonal anxiety which prevents the therapist from being experienced as a safe haven or secure base) or deactivating strategies (e.g. refusing relational proximity which prevents the therapist from becoming a safe haven or a secure base) through cognitive and affect regulation processes (Mallinckrodt, 2010).

Attachment theory provides a framework to understand how disruptions in early caregiving experiences might lead to difficulties with compassion (Merritt & Purdon, 2020). Compassion has been conceptualised as a multi-layered phenomenon encapsulating relational, behavioural, and emotional dimensions including feeling for a person who is suffering, distress tolerance, the universal recognition and understanding of human suffering and a desire to alleviate this (Strauss et al., 2016). In its orientation, compassion can be directed towards oneself (i.e. self-compassion), others and experienced from others (Gilbert, 2020). Self-compassion has been defined as comprising self-kindness, the recognition of suffering as part of the shared human experience and mindful receptivity to thoughts and feelings (Bluth & Neff, 2018). Similarly, compassion for others involves care towards others’ suffering with a desire to support, a sense of connectedness in the face of human suffering and ‘balanced awareness’ of others’ suffering (Pommer et al., 2020). Compassion from others refers to the ability to appreciate and experience others’ compassion (Gilbert, 2020). Conversely, fear of compassion can be defined as the fear or avoidance involved in the response to compassion in its threefold manifestation, which might evoke fears of rejection, judgement or emotion dysregulation (Kirby et al., 2019). Whilst they can reciprocally influence one another, the different orientations of compassion can be independent, suggesting the value of exploring their distinctive expression.

From an evolutionary perspective, compassion captures a form of interpersonal and intrapersonal relationship evolved from the interaction of the three affect regulation functions of the threat, drive and soothing systems (Gilbert, 2020). Specifically, the threat system detects dangers and activate survival mechanisms, the drive system seeks rewarding stimuli and the soothing system has been linked to mammalian caregiving strategies (Gilbert, 2020). Accordingly, compassion is linked to the biopsychosocial functions of caring-attachment behaviours and includes the ability to treat oneself with the same kindness as one has for others in a similar situation of suffering, promoting affiliation (Bluth & Neff, 2018). Conversely, fear of compassion may prevent the ‘neuroception’ of safety required for social engagement behaviours, attachment and autonomic coregulation, increasing the vulnerability to mental health difficulties (Kirby et al., 2019; Porges, 2017). Moreover, compassion is associated with enhanced affect regulation, which describes the ability to effectively manage an emotional experience and has been identified as a transdiagnostic mechanism across a range of psychological disorders (Sloan et al., 2017). Therefore, compassion has been related to the enhancement of psychological wellbeing and the reduction of mental health difficulties (Rooney, 2020) whereas fear of compassion has been linked to increased vulnerability to mental health difficulties (Kirby et al., 2019).

Whilst the internalisation of relational security is associated with the ability to experience the threefold flow of compassion for oneself, towards others and from others, experiences of relational insecurity may lead to low self-compassion or fear of compassion (Gilbert, 2020). Nonetheless, research looking at the relationship between compassion and attachment has yielded mixed results. For instance, although both preoccupied and fearful attachment were correlated with low self-compassion, a focus on compassion has been found to reduce attachment anxiety and avoidance but not disorganised attachment in a healthy population (Navarro-Gil et al., 2020). Furthermore, significant correlations have been detected between self-compassion and avoidant attachment in a clinical population (Mackintosh et al., 2018) but not in a non-clinical sample (Wei et al., 2011). Consequently, clarifying the intersection between compassion and attachment can help shed light on transdiagnostic mechanisms underpinning a range of psychological disorders (Kirby et al., 2019).

Despite the theoretical and conceptual associations between compassion and attachment, the clinical implications of their relationship remain unclear. Whereas previous reviews have explored the links of mental health difficulties to compassion (MacBeth & Gumley, 2012) and attachment (Tironi et al., 2021) as well as the mediating role of emotion regulation in the relationship of mental health with compassion (Inwood & Ferrari, 2018) and attachment (Mortazavizadeh & Forstmeier, 2018), no review has systematically synthesised the relationship between compassion and attachment in individuals with mental health needs. Firstly, as compassion may be shaped by early attachment experiences, a review can assess how insecure attachment styles interact with compassion, compounding vulnerability to psychological difficulties (Tironi et al., 2021). Secondly, findings within the general population may not automatically apply to individuals with mental health difficulties. Accordingly, a review can ascertain whether exploring the relationship between compassion and attachment is clinically useful (Mackintosh et al., 2018). Thirdly, attachment styles may differentially influence the response to compassion-focused interventions (Navarro-Gil et al., 2020). Thus, a review can inform research on evidence-based therapeutic interventions targeting compassion (Craig et al., 2020) as well as on the effectiveness of adaptations to clients’ attachment styles (Berry & Danquah, 2016).

Consequently, considering the body of literature related to both compassion and attachment patterns across psychological disorders (Mortazavizadeh, & Forstmeier, 2018), a systematic review of the findings related to the relationship between compassion and attachment in individuals with mental health needs is warranted.

Objective

The review aims to explore the relationship between compassion and attachment in individuals with mental health difficulties.

Method

Eligibility Criteria

Based on existing literature examining compassion and attachment in relation to mental health, this review focused on findings related to their association which are relevant to clinical practice. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in Table 1 along with the rationale.

Information Sources

The literature search was completed on November 9, 2021 when bibliographic databases were last consulted. The following databases were searched from their inception: APAPsycInfoⓇ, APAPSycArticlesⓇ, Social Science Database, Sociology Database and PTSDpubs (searched through ProQuest LLC interface); CINAHL, MEDLINE, and Pubmed (searched through EBSCOhost interface) and Web of Science (searched through Thomson Reuters interface). Moreover, references cited in studies included in the systematic review were also examined to identify potential studies.

Search Strategy

The search strategy comprised “compassion” and “attachment” to maximise the location of all potentially relevant studies. The Boolean operator “AND” was used to identify these keywords within the “title and “abstract” fields of the databases. The limits applied were English language and peer-reviewed articles to enhance the clinical reliability of findings.

Selection Process

Records identified from each database were exported to a web-based reference manager software and duplicates were removed. Title and abstract screening was conducted by four reviewers. Each record was screened independently by the first author, whereas other three reviewers worked independently to screen one third of the total number of records retrieved. If further information was needed to ascertain the eligibility of the studies, articles were retrieved and their full text was examined by the first author and a second screener. Disagreements regarding the eligibility of studies were resolved through discussion or consultation with another reviewer.

Data Collection Process

Data from each report was collected independently by the first author and checked by another reviewer independently. Inconsistencies were discussed between the first author and the reviewer. Disagreements were resolved with the involvement of another reviewer.

Study Risk of Bias Assessment

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS; Modesti et al., 2016) and the Downs and Black Checklist (D&B; Downs & Black, 1998) were utilised to assess the quality of cross-sectional and intervention studies, respectively. An overall risk of bias judgement was made by adding the quality score of each study and dividing by the number of studies. Specifically, cross-sectional studies could have a maximum score of 10 in the NOS methodological domains, namely sample selection (5 points), comparability (3 points), and outcome (2 points). On average, cross-sectional studies scored 6.8, with an overall score of 5 indicating satisfactory quality. Intervention studies could have a maximum score of 28 in the D&B components of reporting (11 points), external validity (3 points), internal validity—bias (7 points), internal validity—confounding (6 points) and power, whose scoring was modified to rate whether studies performed power calculations (1 point). On average, intervention studies scored 16.5, with an overall score of 15 indicating satisfactory quality. The main author and two reviewers worked independently to assess risk of bias in each study. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus. No additional information was needed from study investigators.

Results

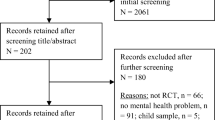

Study Selection

Seven studies were eligible for inclusion, five cross-sectional studies and two experimental studies (placebo controlled and repeated measures). Figure 1 illustrates the selection process in a flow diagram. All eligible reports were retrievable and no additional articles were found upon searching the references of included studies.

Synthesis of Results

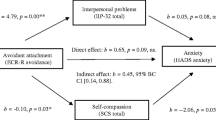

A summary of findings and key characteristics of each study are presented in Table 2. The review highlighted a relationship between compassion and attachment dimensions. In line with the evolutionary understanding of compassion, Barnes and Mongrain (2020) suggested that the personality factor of ‘equanimity’ can be mapped onto the soothing system as described by Gilbert (2020). Indicating positive intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships, equanimity was defined as the presence of balanced mental health, self-compassion, low attachment avoidance and socially desirable characteristics (Barnes & Mongrain, 2020). While the interplay between self-compassion and low attachment avoidance belong to a wider personality trait linked to adaptive psychological functioning (Barnes & Mongrain, 2020), Mackintosh et al. (2018) argued that the relationship between attachment and the development of compassion is not straightforward as individuals with an avoidant attachment style may have negative or positive internal working models. Despite attachment insecurity, a pre-existing positive sense of self and relationship might facilitate the development of self-compassion. Consequently, evidence suggests a more direct association between self-compassion and secure attachment as opposed to the more complex relationship between self-compassion and insecure attachment.

Resonating with the evolutionary differentiation between soothing and threat systems (Gilbert, 2020), Naismith et al. (2019) proposed that adverse childhood experiences predict fear of compassion towards self whereas parental warmth predicts self-compassion. To explain the correlation between fear of compassion towards self and avoidant attachment, Naismith et al. (2019) hypothesised that abusive and/or neglectful environments activate the threat system, triggering a fear response. Moreover, indicating a fear of abandonment as well as difficulties with depending on and getting close to others, fear of compassion may be accompanied by insecure attachment (Gilbert et al., 2014). Similarly, Dudley et al. (2018) suggested that self-compassion is not accessible as long as the threat system is active due to the psychological distress caused by hearing voices. Naismith et al. (2019) argued that the lack of correlation between self-compassion and insecure (i.e. anxious and avoidant) attachment reflects how the overstimulation of the threat system prevents the sufficient activation of the soothing system which leads to the development of compassion and is associated with secure attachment. Thus, findings may be interpreted in line with the evolutionary understanding of compassion.

The review also revealed the distinctive and compounded impact of compassion and attachment on psychological functioning. Whereas no correlation was found between self-compassion and interpersonal problems, insecure (i.e. avoidant and anxious) attachment was correlated with higher interpersonal problems in individuals with anxiety and depression (Mackintosh et al., 2018). Although attachment anxiety showed no relationship with emotional distress, depression nor anxiety, both low self-compassion and attachment avoidance were significantly correlated with higher emotional distress and anxiety (Mackintosh et al., 2018). However, neither self-compassion nor attachment avoidance were correlated with depressive symptoms (Mackintosh et al., 2018). Furthermore, Kotera and Rhodes (2019) found that self-compassion did not moderate the effects of anxious attachment as correlated with problematic sexual behaviour. Conversely, while no significant correlation was found between insecure (i.e. avoidant, anxious, and fearful) attachment and psychological distress in individuals hearing voices, self-compassion had a significant negative correlation with levels of both severity of and distress from voices (Dudley et al., 2018). Despite the correlation between self-compassion and secure attachment, Dudley et al. (2018) reported that only self-compassion but not secure attachment mediated the relationship between mindfulness of voices and severity of voices. Nonetheless, within the same sample, fearful attachment indicated a lower ability to respond mindfully to voices (Dudley et al., 2018). Thus, the positive correlation between compassion and secure attachment appeared to be a resiliency factor against mental health difficulties.

Evidence indicated the value of considering compassion and attachment in tailoring interventions. Exploring the inhibitors to compassion may help individuals with insecure attachment engage in activities that evoke positive affects in the treatment of depression (Gilbert et al., 2014). If holding a positive self-view, individuals with avoidant attachment may benefit from developing self-compassion when presenting with interpersonal problems and emotional distress (Mackintosh et al., 2018). Similarly, self-compassion was found to be a worthwhile therapeutic target for individuals with anxious attachment who experience their sexual behaviours as problematic (Kotera & Rhodes, 2019), for individuals hearing voices with fearful attachment (Dudley et al., 2018) and for individuals with difficulties associated with a diagnosis of personality disorders and attachment avoidance (Naismith et al., 2019). Therefore, formulations may be enriched by identifying factors to enhance self-compassion depending on individuals’ attachment styles (Naismith et al., 2018).

Discussion

The review aimed to explore the relationship between compassion and attachment in individuals with mental health needs. Although caution is needed in interpreting the evidence because of the paucity of the studies retrieved, findings corroborate the importance of compassion and attachment in line with existing literature.

Specifically, in relation to the objective of the review, findings provided some clarification of the dynamics between the two constructs examined. Firstly, the evaluation of the association between compassion and attachment emphasised how self-compassion and secure attachment are correlated and may act as protective and resiliency factors in samples with depression (Gilbert et al., 2014), problematic sexual behaviour (Kotera & Rhodes, 2019) and for individuals hearing voices (Dudley et al., 2018). However, correlations between self-compassion, fear of compassion and insecure attachment varied in terms of direction and significance (Gilbert et al., 2014; Naismith et al., 2019), with ambivalent and inconclusive findings. Therefore, the review adds to the evidence on the positive role of self-compassion and secure attachment against mental health difficulties. Furthermore, the review highlights the importance of clarifying the dynamics between specific dimensions of insecure attachment and compassion.

Secondly, the exploration of the nature of the relationship between compassion and attachment appeared to corroborate the theoretical link between a developed soothing system, secure attachment and self-compassion (Gilbert, 2020). Findings suggested that the overstimulation of the threat system might lead to fear of compassion and impair access to self-compassion (Gilbert et al., 2014; Naismith et al., 2018, 2019). As opposed to the lack of activation of the soothing system, insecure attachment might be a result of enduring activation of the threat system (Naismith et al., 2019). Moreover, the review points to the need for clarifying the potential role of the drive system in the intersection between compassion and attachment styles. If therapists focused on the emergence of compassion and helped clients amplify its experience experientially, compassion might be pursued as a rewarding experience in the face of threat. Accordingly, attachment-informed models of therapy like Accelerated Experiential Dynamic Psychotherapy (AEDP) emphasise the value of focusing on transformative affects to promote healing and foster psychological growth (Fosha, 2021). Clinically, compassion from the therapist might be resisted as a result of deactivating strategies in individuals with avoidant/dismissive attachment or pursued through hyperactivating strategies in individuals with anxious/preoccupied attachment. Therefore, the review sheds some light on the possible origins of compassion and attachment as having distinctive neural underpinnings (Ashar et al., 2016).

Thirdly, the clinical relevance of the intersection of attachment and compassion adds to the literature attesting the value of attachment-informed (Berry & Danquah, 2016) and compassion-focused (Craig et al., 2020) interventions. Exploring facilitators and inhibitors to mental health treatments, findings pinpointed different effects of the interplay of attachment, compassion and fear of compassion, suggesting that targeting self-compassion may be relevant across attachment dimensions and mental health difficulties. These findings resonate with the evidence on the effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility of psychological therapies considering compassion (Craig et al., 2020) and attachment (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019), pointing to the potential added value of integrating both compassion and attachment into interventions. As a promising example, Attachment-Based Compassion Therapy (ABCT) has been developed as a culturally sensitive protocol combining practices to develop compassion (towards self, others and from others) and the understanding of the role of attachment styles in mental health (García-Campayo et al., 2016). Accordingly, the review suggests that the relationship between compassion and attachment may be worth exploring amongst individuals with mental health needs.

Limitations of Evidence

In relation to the population, despite meeting clinical levels of distress, participants were often self-selected and at times included individuals with non-clinical level of psychological distress, limiting generalisibility. Specifically, from the total number of 4839 participants in the seven eligible studies, 4375 of them, who stemmed from only one study (Barnes & Mongrain, 2020), were self-selected from the general population through a screening tool for depression. Furthermore, samples were relatively small, biased towards Western White females, and did not include children, adolescents nor older adults, thus preventing applicability to different ethnicities, cultural contexts, and age groups. In relation to the phenomenon of interest, studies mainly explored self-compassion, secure, avoidant and anxious attachment as opposed to fear of compassion and disorganised attachment, which may be more relevant to mental health difficulties (Matos et al., 2017).

In relation to the outcomes, both attachment and compassion were assessed through self-reports which are susceptible to social desirability bias, personal interpretation and are not as comprehensive as interview-based measures. While the psychometric properties of compassion and attachment measures were established in non-clinical samples, only one study (Naismith et al., 2019) considered the negative subscale of the Self-Compassion Scale, which has a stronger predictor of mental health difficulties (Muris & Petrocchi, 2017). Depending on the measures used, attachment was operationalised as a categorical or dimensional construct. On one hand dimensional data provide more statistical power, but on the other hand the clinical interpretation of categorical attachment style is difficult due to lack of consensus. Clinically, if attachment is dimensional, assessment will need to consider the degree to which clients present with insecure and secure patterns (Lubiewska & Van de Vijver, 2020). Furthermore, developmental outcomes of attachment may differ depending on categorical or dimensional classifications, which in turn might change across age groups (Lubiewska & Van de Vijver, 2020). Thus, consistency and the use of different measures could help bring clarity and emphasise the clinical values of attachment classifications. Finally, the cross-sectional design in most studies precluded the establishment of a causal relationship between compassion and attachment.

Limitations of Review Processes

Despite the involvement of reviewers for title and abstract screening, data extraction and quality analysis were performed by the first author with independent screening and/or checking, which could have introduced some risk of error. Because of time constraints, the search strategy was limited to peer-reviewed English articles. Consequently, the inclusion of grey literature, multi-lingual databases and contact with experts in the field could have located additional studies. However, the studies retrieved suggest that research on compassion and attachment is in its early stages and geographically circumscribed, in line with the historical origins of the theoretical framework exploring such constructs (Gilbert, 2020). Furthermore, the search strategy to identify attachment-related studies could have been expanded to include internal working models and similar concepts. Nevertheless, the combination with compassion is likely to have yielded all relevant studies including the exploration of attachment due to the novelty of such focus of investigation (Mackintosh et al., 2018). Thus, the methodological limitations should not change the overall conclusions. Therefore, to the authors’ knowledge, this review is the first attempt to gather findings on the relationship between compassion and attachment.

Diversity Considerations

The studies highlighted a potential ethnocentric bias due to the insufficient inclusion of ethnic minorities. Although the value placed on relationship and independence might vary across cultures and individuals, no information was provided on participants’ understanding of compassion and attachment. Thus, if considered, diversity factors, such as disability, gender and sexual orientation, age, and socioeconomic status, might show distinctive patterns in attachment and/or compassion orientations.

Professional Relevance

Both secure attachment and self-compassion may enhance resilience against mental difficulties. Due to the relevance of compassion across the lifespan, positive parenting interventions may have the potential to buffer the impact of psychological difficulties by fostering attachment security. Similarly, compassion-informed mental health services may provide a paradigm shift in the care of individuals presenting with insecure attachment due to early interpersonal trauma. Specifically, intervention attrition rates may be impacted due to clinicians offering a foreign example of compassionate care towards which clients with insecure attachment may be more ambivalent. Resonating with a biopsychosocial understanding of mental health difficulties, the focus on the compassion–attachment dynamics may contribute to the appreciation of context (e.g. interpersonal dynamics; environment; cultural factors). In line with findings from neuroscience on plasticity, enhancing compassion may reverberate on clients’ neural patterns and shift their attachment towards security (Ashar et al., 2016). Moreover, the relevance of the relationship of compassion and attachment to mental health suggests the importance of adapting interventions based on attachment styles, whilst considering compassion as therapeutic target. Consequently, existing evidence-based interventions could be enriched by formulations including an understanding of compassion and attachment to enhance treatment responsiveness.

Conclusion

Exploring the relationship between compassion and attachment can be a prolific avenue for research and clinical practice. Overall, the review adds to the current knowledge since it highlights a new area of clinical research that may enrich treatment interventions to include compassion and attachment as resilient factors of mental health and wellbeing.

References

Ashar, Y. K., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Dimidjian, S., & Wager, T. D. (2016). Toward a neuroscience of compassion: A brain systems-based model and research agenda. In J. D. Greene, I. Morrison, & M. E. P. Seligman (Eds.), Positive neuroscience (pp. 125–142). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199977925.003.0009

Barnes, C., & Mongrain, M. (2020). A three-factor model of personality predicts changes in depression and subjective well-being following positive psychology interventions. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(4), 556–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1651891

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226

Berry, K., & Danquah, A. (2016). Attachment-informed therapy for adults: Towards a unifying perspective on practice. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 89(1), 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12063

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base. Basic Books.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships; attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). Guilford Press.

Collins, N. L. (1996). Working models of attachment: Implications for explanation, emotion, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(4), 810–832. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.71.4.810

Collins, N. L., & Read, S. J. (1990). Adult attachment, working models and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 644–663. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.644

Craig, C., Hiskey, S., & Spector, A. (2020). Compassion focused therapy: A systematic review of its effectiveness and acceptability in clinical populations. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 20(4), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2020.1746184

Dudley, J., Eames, C., Mulligan, J., & Fisher, N. (2018). Mindfulness of voices, self-compassion, and secure attachment in relation to the experience of hearing voices. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12153

Fosha, D. (2021). Introduction: AEDP after 20 years. In D. Fosha (Ed.), Undoing aloneness & the transformation of suffering into flourishing: AEDP 2.0 (pp. 3–23). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000232-001

García-Campayo, J., Navarro-Gil, M., & Demarzo, M. (2016). Attachment-based compassion therapy. Mindfulness & Compassion, 1(2), 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mincom.2016.10.004

Gilbert, P. (2020). Compassion: From its evolution to a psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 3123. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586161

Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Catarino, F., Baião, R., & Palmeira, L. (2014). Fears of happiness and compassion in relationship with depression, alexithymia, and attachment security in a depressed sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(2), 228–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12037

Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Matos, M., & Rivis, A. (2011). Fears of compassion: Development of three self-report measures. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 84(3), 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608310X526511

Inwood, E., & Ferrari, M. (2018). Mechanisms of change in the relationship between self-compassion, emotion regulation, and mental health: A systematic review. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 10(2), 215–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12127

Kirby, J. N., Day, J., & Sagar, V. (2019). The ‘Flow’ of compassion: A meta-analysis of the fears of compassion scales and psychological functioning. Clinical Psychology Review, 70, 26–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.03.001

Kotera, Y., & Rhodes, C. (2019). Pathways to sex addiction: Relationships with adverse childhood experience, attachment, narcissism, self-compassion and motivation in a gender-balanced sample. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 26(1–2), 54–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2019.1615585

Lubiewska, K., & Van de Vijver, F. J. (2020). Attachment categories or dimensions: The Adult Attachment Scale across three generations in Poland. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(1), 233–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519860594

MacBeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 545–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003

Mackintosh, K., Power, K., Schwannauer, M., & Chan, S. W. (2018). The relationships between self-compassion, attachment and interpersonal problems in clinical patients with mixed anxiety and depression and emotional distress. Mindfulness, 9(3), 961–971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0835-6

Mallinckrodt, B. (2010). The psychotherapy relationship as attachment: Evidence and implications. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(2), 262–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407509360905

Matos, M., Duarte, J., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2017). The origins of fears of compassion: Shame and lack of safeness memories, fears of compassion and psychopathology. The Journal of Psychology, 151(8), 804–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2017.1393380

Merritt, O. A., & Purdon, C. L. (2020). Scared of compassion: Fear of compassion in anxiety, mood, and non-clinical groups. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59(3), 354–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12250

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2019). Attachment orientations and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.006

Miljkovitch, R., Moss, E., Bernier, A., Pascuzzo, K., & Sander, E. (2015). Refining the assessment of internal working models: The Attachment Multiple Model Interview. Attachment & Human Development, 17(5), 492–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2015.1075561

Mortazavizadeh, Z., & Forstmeier, S. (2018). The role of emotion regulation in the association of adult attachment and mental health: A systematic review. Archives of Psychology, 2(9), 1–25. Retrieved from http://www.archivesofpsychology.org

Muris, P., & Petrocchi, N. (2017). Protection or vulnerability? A meta-analysis of the relations between the positive and negative components of self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24, 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2005

Naismith, I., Mwale, A., & Feigenbaum, J. (2018). Inhibitors and facilitators of compassion-focused imagery in personality disorder. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 5(2), 283–291. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2161

Naismith, I., Zarate Guerrero, S., & Feigenbaum, J. (2019). Abuse, invalidation, and lack of early warmth show distinct relationships with self-criticism, self-compassion, and fear of self-compassion in personality disorder. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 26(3), 350–361. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2357

Navarro-Gil, M., Lopez-del-Hoyo, Y., Modrego-Alarcón, M., Montero-Marin, J., Van Gordon, W., Shonin, E., & Garcia-Campayo, J. (2020). Effects of attachment-based compassion therapy (ABCT) on self-compassion and attachment style in healthy people. Mindfulness, 11(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0896-1

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2, 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

Porges, S. W. (2017). Vagal pathways: Portals to compassion. In E. M. Seppälä, E. Simon-Thomas, S. L. Brown, M. C. Worline, C. D. Cameron, & J. R. Doty (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of compassion science (pp. 189–202). Oxford University Press.

Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18, 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.702

Rooney, J. M. (2020). Compassion in mental health: A literature review. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 24(4), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-05-2020-0029

Sloan, E., Hall, K., Moulding, R., Bryce, S., Mildred, H., & Staiger, P. K. (2017). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic treatment construct across anxiety, depression, substance, eating and borderline personality disorders: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.09.002

Strauss, C., Taylor, B. L., Gu, J., Kuyken, W., Baer, R., Jones, F., & Cavanagh, K. (2016). What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clinical Psychology Review, 47, 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.004

Tironi, M., Charpentier Mora, S., Cavanna, D., Borelli, J. L., & Bizzi, F. (2021). Physiological factors linking insecure attachment to psychopathology: A systematic review. Brain Sciences, 11(11), 1477. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11111477

Wei, M., Liao, K. Y., Ku, T. Y., & Shaffer, P. A. (2011). Attachment, self-compassion, empathy, and subjective well-being among college students and community adults. Journal of Personality, 79(1), 191–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00677.x

Wei, M., Russell, D. W., Mallinckrodt, B., & Vogel, D. L. (2007). The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR)-short form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 88(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890701268041

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conceptualisation and design. Literary search and analysis were performed by Nicola Amari, Shona Peacock, Janet Stewart and Dr Erin Alexandra Alford. The manuscript was written by Nicola Amari and critically reviewed by Tasim Martin and Dr Adam Mahoney.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

N/A.

Consent to Participate

N/A.

Consent to Publish

N/A.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amari, N., Martin, T., Mahoney, A. et al. Exploring the Relationship Between Compassion and Attachment in Individuals with Mental Health Difficulties: A Systematic Review. J Contemp Psychother 53, 245–256 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-022-09573-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-022-09573-4