Abstract

Background

Due to the absence of curative treatments for inborn errors of immunity (IEI), children born with IEI require long-term follow-up for disease manifestations and related complications that occur over the lifespan. Effective transition from pediatric to adult services is known to significantly improve adherence to treatment and long-term outcomes. It is currently not known what transition services are available for young people with IEI in Europe.

Objective

To understand the prevalence and practice of transition services in Europe for young people with IEI, encompassing both primary immunodeficiencies (PID) and systemic autoinflammatory disorders (AID).

Methods

A survey was generated by the European Reference Network on immunodeficiency, autoinflammatory, and autoimmune diseases Transition Working Group and electronically circulated, through professional networks, to pediatric centers across Europe looking after children with IEI.

Results

Seventy-six responses were received from 52 centers, in 45 cities across 17 different countries. All services transitioned patients to adult services, mainly to specialist PID or AID centers, typically transferring up to ten patients to adult care each year. The transition process started at a median age of 16–18 years with transfer to the adult center occurring at a median age of 18–20 years. 75% of PID and 68% of AID centers held at least one joint appointment with pediatric and adult services prior to the transfer of care. Approximately 75% of PID and AID services reported having a defined transition process, but few centers reported national disease-specific transition guidelines to refer to.

Conclusions

Transition services for children with IEI in Europe are available in many countries but lack standardized guidelines to promote best practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Inborn errors of immunity (IEI) are a heterogeneous group of rare disorders with increased, poor, or absent function in components of the innate and/or adaptive immune systems. Primary immunodeficiencies (PID) and autoinflammatory diseases (AID) represent the majority of known IEI [1, 2] PID are characterized by infection susceptibility, often associated with autoimmune, inflammatory, and malignant complications. In contrast, the dominant feature in AID is recurrent or chronic inflammatory episodes that are systemic, distinct from autoimmune diseases and associated with an increasingly wide clinical phenotype [3, 4]. The majority of AID and more severe forms of PID manifest in childhood although additional manifestations and new complications occur over life. Marked improvements in the diagnosis and management of PID and AID in the last decades have improved the outlook for many patients, but at the same time bring new challenges to the care of these patients—many of whom have multi-morbidity [5,6,7]. This modification of the natural history of the disease is associated with an increased survival of pediatric patients with PID and AID, who now need transfer to adult services for life-long follow-up [8] Therefore, a well-established interdisciplinary transition protocol is considered a standard of care for these patients and their families’ needs to be carefully planned and managed [9].

Transition has been defined as “A purposeful, planned process that addresses the medical, psychosocial, and educational/vocational needs of adolescents and young adults with chronic physical and medical conditions as they move from child-centered to adult-oriented health care systems”[10], while transition can often be used to refer to the physical move of care to adult services. It is important to make a distinction between this “transfer” and “transition” which also includes the psychological shift whereby the young adult becomes responsible for their own care. To date, despite there already being well-established transition guidelines for patients with other life-long immune-mediated conditions that emerge in childhood, such as rheumatic diseases [11], asthma, and allergy [12], transition pathways for PID and AID have been less clearly defined. Moreover, there are significant differences among European countries regarding pediatric and adult specialist healthcare provision for patients with PID and AID [13], and to date there are no available data for dedicated transition programs for these rare disorders.

The European Reference Networks (ERN) are virtual networks involving healthcare providers across Europe (https://ec.europa.eu/health/ern_en). ERNs aim to tackle complex or rare diseases and conditions that require highly specialized treatment and a concentration of knowledge and resources. To date, there are 24 ERNs involving 25 European countries, over 300 hospitals with over 900 healthcare units and covering all major disease groups. Among them, the European Reference Network on Rare Immunodeficiency, Autoinflammatory and Autoimmune Disease (ERN-RITA) brings together leading European centers with expertise in diagnosis and treatment of rare immunological disorders including PID, AID and autoimmune diseases.

The ERN-RITA Transition Working Group aimed to define the current practices in transition for patients with PID and AID diseases across European health centers as a first step to creating global guidance for transition of these patients.

Methods

A survey (Supplementary file2) asking about current transition numbers and practice was developed by the ERN-RITA steering group. The survey was circulated to clinicians working in European pediatric PID and AID services in June 2018 through personal and professional networks. To enhance the response rate and capture additional centers, the same questionnaire was sent or re-sent in November 2019 to centers who had not submitted responses to the first circulation. Clinicians were asked to complete separate questionnaires for their cohorts of patients with PID and AID and only one response per center for each was permitted. Ethical approval was not required for collection of this information.

Results

Respondent demographics

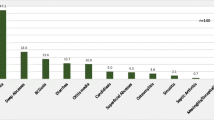

The survey was sent to 154 clinicians, from 106 centers, in 87 cities in 23 countries in Europe (Supplementary Fig. 1). In total, 76 responses were received from 52 centers, in 45 cities across different 17 countries. Forty-four responses were received from PID centers based in 39 cities in 15 countries, while the remaining 32 responses were obtained from AID centers across 29 cities in 13 countries in Europe. Of the 76 responding centers, 38 centers (50%) are members of the RITA-ERN network.

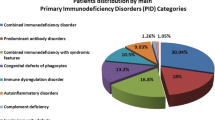

PID services reported treating larger numbers of patients than AID services (Table 1), reflecting the relative prevalence of the two conditions. Forty-one percent (13/32) of AID services reported treating less than 50 pediatric patients compared with 19% (8/43) of PID services. In contrast, 42% (18/43) of PID services follow more than 200 pediatric patients while only 6% (2/32) of AID centers follow cohorts of this size.

As guidance for other immune-mediated conditions recommend that the transition process is started in early adolescence [11, 12] the centers were asked how many pediatric patients with PID or AID they cared for between the ages of 12 and 18. The majority of centers follow fewer than 50 patients in this age group (71%, 22/31 of the AID services and 50%, 22/44 of the PID services). None of the AID services and only 18% (8/44) of the PID services cared for more than 100 patients in this transition age range (Table 1). The vast majority of centers transfer only up to ten patients to adult care each year (91%, 29/32 AID services, and 73%, 32/44 PID services) while a small proportion of PID centers (5%, 2/44) transition 20–40 patients per year (Table 1).

Logistics of the transition process

To determine whether patients continue to receive specialist care in adulthood, centers were asked where they transitioned patients to. Fifteen respondents (20%) had more than one option for transfer of care. The vast majority of centers that responded reported referring patients to specialist adult PID/AID centers (86%, 38/44 PID services and 77%, 24/31 AID services: Fig. 1). In keeping with the fact that AID are often cared for within rheumatology services rather than immunology clinics, 32% (10/31) pediatric AID centers referred to adult rheumatologists. No centers discharged without hospital follow-up although a small number referred patients to non-specialist adult internal medicine physicians (16%, 7/44 PID services and 19%, 6/31 AID services).

The transition process started at a median age of 16–18 years for both PID and AID services (Fig. 2a). A higher proportion of AID than PID services started transition before the age of 16 years (55%, 17/31 of AID centers compared with 30%, 13/44 of PID centers). A significant minority of services reported initiating the transition process after patients turn 18 (23%, 10/44 of PID services and 13%, 4/31 of AID services). The median age for the end of the transition process was 18–20 years for both PID and AID (Fig. 2b) with a small proportion of centers reporting that the end of transition occurred after the age of 20 years (14%, 6/44 of PID centers and 10%, 3/31 of AID centers). In keeping with this, patients were most frequently transferred to adult care between the ages of 18–20 years (Fig. 2c) with a smaller proportion of centers transferring patients before 18 years of age (32%, 14/44 of PID services and 32%, 10/31 of AID services). Delay in transfer to over 20 years of age was reported by a minority of centers (9%, 4/44 of PID centers and 6%, 2/31 of AID centers).

The majority of centers reported that patients were referred to an adult center a similar distance from the patient’s home (75%, 33/44 pediatric PID services and 23/31, 74% pediatric AID services; Supplementary Fig. 2). Only one AID center reported that the adult center was further from the patient’s home but 20%, 9/44 PID services and 19%, 6/31 AID services responded that the distance between the patient’s home and adult center varied for each patient.

Transition partner and process

The majority of the response sites reported having formal transition partners in place (91%, 40/44 of PID services and 94%, 29/31 AID services). Transfer was typically directly to adult centers, with only 7% (3/44) PID services and 16% (5/31) AID services transitioning to intermediate adolescent services (Table 2). Few PID or AID respondents reported transferring their patients to adult care services with dedicated young adult clinics (11%, 5/44 PID and 29%, 9/31 AID services). Joint appointments with healthcare professionals from pediatric and adult services were common prior to the transfer of care (75%, 33/44 PID and 68%, 21/31 AID centers), involving physicians, nurses, psychologists, and specialists from other medical teams. The number of joint clinics held for each patient was determined by the severity of illness. PID services described holding 1–5 joint clinics, with 4–5 appointments for patients with more complex diseases. In contrast, the AID services reported holding 1–3 appointments for each patient. The vast majority of the services examined described full integration of patient records with the adult care provider, with only 21% (9/43) PID centers and 27% (8/30) AID services responding negatively to this item (Table 2).

Just over three quarters of PID and AID services reported having a defined transition processes for transfer of care to adult services (34/44 and 24/31 respectively; Fig. 3a). However, the majority of PID and AID services reported a lack of national disease-specific transition guidelines to refer to (86%, 38/44 and 80%, 24/30 respectively; Fig. 3b). The PID services describing the complete or partial use of national transition guidelines were located in Poland and the UK, while the AID services were based in Italy, Finland, and the UK. Few centers reported transition-specific research programs at their site (20%, 9/44 PID and 29%, 9/31 AID centers; Table 2).

The majority of centers did not report specific difficulties in identifying adult care for their patients (Supplementary Fig. 3). However, for those who did, the lack of specialist adult center (9%, 8/23 PID and 27%, 3/11 AID centers) was the biggest difficulty. If reporting problems, the majority of clinicians identified a number of different weaknesses of the transition process in their services—with 54 respondents (71%) listing more than one difficulty. Lack of time to prepare the documents and/or funding and resource in adult services, fragmentation of adult services, lack of holistic care in both and adult pediatric services, lack of suitable centers to transition to, and patients not wanting to engage were reported as the main weaknesses of the transition process (45%, 33%, 33%, 26%, 22%, 22%, and 18% of services, respectively) (Supplementary Table 1). This survey did not capture specific problems with the suitability of adult services for transition. However, responders did note that it is often the transfer of services for all the various comorbidities in the adult sector, rather than transfer for PID itself that is problematic, and that different arrangements for transition may be required for different AID diagnoses. The lack of provision for patients with learning disability or mental health difficulties compared to pediatrics was also noted as a weakness of the process.

Prior to transfer, services report discussing a number of different topics or concerns with their patients, with the majority of services discussing the patient’s understanding of the disease (92% of services), and medication (88%), genetics (86%), compliance with treatment (88%), and responsibility for own health care (82%), preference for transition center (71%) and expectations of adult services (70%) (Supplementary Table 2). Around half of services discussed mental health or wellbeing, vocational expectations, sexual health, substance use, and/or life expectancy.

Challenges for smaller centers

The data were reviewed to determine whether there were differences between sites transferring more or less than 10 patients to adult services each year. Sixty-one services transferred less than 10 patients each year, but only 12 transferred more than 10. Services transitioning less than ten patients each year treated fewer pediatric patients in total and within the 12–18 year age range (Supplemental Fig. 4a and b). A higher percentage of centers transferring more than ten patients a year reported transferring patients between the ages of 16 and 18, having a defined process for transition, having integrated medical files, and having joint clinics with adult and pediatric centers (Table 3). A higher percentage of centers transferring less than ten patients a year reported initiating transition and/or transferring care after the age of 18, transferring to services with a specialist young adult clinic, and having disease-specific guidelines (Table 3).

Discussion

Successful transition from pediatric to adult services is a key component of clinical care for chronic conditions that predicts treatment adherence and medical outcome [14,15,16,17]. Transition for rare diseases (RD), such as PID and AID, present specific challenges, particularly for patients with multisystem disorders. In general, across Europe, pediatric PID and AID care occurs mainly in specialist centers of varying sizes while dedicated adult services are less well defined. Thus, provision for patients with PID and AID exhibits regional differences, creating variation in the patient care pathway as seen for other RD—a specific issue that ERNs seek to address [18]. This ERN-RITA study is the first report of transition practices for patients with PID and AID across European health centers and aimed to understand the current processes and key barriers to transition for these RD.

This survey was circulated to pediatric centers caring for patients with PID and AID and therefore the results reflect the pediatric heath care professional (HCP) perspective. Our results report that the majority of pediatric centers have transition processes in place although only a minority start early in adolescence, which is recommended as it leads to better knowledge and skills and long-term outcome [19]. As the majority of the pediatric PID and AID services begin the transition process when the patient is between the ages of 16 and 18, the processes of transition and transfer to adult services often occur closely together, reducing time for adjustment for patients and their families. The most frequently reported factor influencing age of transfer was “patient considered ready for transition,” but data were not gathered on whether readiness for transition is evaluated by patients themselves or by medical teams. This is especially important because 18% of the total respondents reported patient unwillingness to engage as one of the main weaknesses of their transition program. Furthermore, patient readiness has been observed to influence optimal transition in terms of health-related outcomes and the development of self-management skills by patients [20, 21]. Generic transition guidelines suggest that the process of transition should start when the patient is 13 or 14 at the latest [22], in order to enhance patient familiarity with the adult unit and staff prior to transfer and augment patient readiness for transfer. It may be advisable for centers to administer questionnaires measuring the patient’s readiness to transition and tailor transition plans accordingly to address the unique concerns of each patient.

Meeting the adult team prior to transfer has been identified as a significant factor in predicting better outcomes for young people living with long-term conditions [23]. This occurred in the majority of, but not all, centers transitioning young adults with PID or AID through the provision of joint in-person or virtual clinics attended by HCPs from both pediatric and adult centers prior to the transfer of care. Although special care services for young people are recommended by the International Patient Organisation for Primary immunodeficiencies (IPOPI) [24], only a small proportion of PID and AID clinics surveyed reported transferring their patients to adult services with designated young adult clinics, with even fewer transferring their patient cohort to adolescent immunology clinics prior to adult services. These practices may reduce the confidence of young adults to manage their health, as only 60% or less of all the services in this sample discuss broader psychosocial and occupational concerns like fertility, sexual health, substance use, mental health and wellbeing, vocational and life expectations, and health insurance with their patients prior to transfer (see Supplementary Table 3). Transition to adolescent centers or dedicated young adult clinics may thus allow for the provision of holistic care to young patients by addressing health and wellbeing concerns specific to this developmental stage alongside those stemming from their IEI.

While a minority of services reported difficulties in transferring patients to adult services, there were shared difficulties in the process of transition where these were reported, particularly the lack of engaged specialist adult services, which may be a contributing factor to delayed transition in some centers. Fragmentation of healthcare teams across different services also may present challenges in identifying suitable adult centers equipped to offer all required aspects of interdisciplinary care for young patients with multimorbidity. In addition, many services identified lack of time to prepare documentation as the main weakness of their transition program, and/or incomplete integration of medical records across pediatric and adult services. It is our opinion that each pediatric service, and adult services who receive transfer should have a nominated transition lead and dedicated administrative staff to oversee documentation and allow for more seamless transition.

At present, while the majority of the pediatric PID and AID clinics across Europe reported using a defined transition process to transfer patients to adult services, few reported having access to national disease-specific guidelines for transition. In the interest of optimizing health-related outcomes for adolescents undertaking increased responsibility of their health, it may be advantageous to develop disease-specific guidelines that outline gold-standard transition practices and outcomes based on consensus from multidisciplinary healthcare professionals. Since the completion of this study, the French Network for Autoimmune and Autoinflammatory Diseases and Italian Primary Immunodeficiency Network have published their consensus statements on management of transition from pediatric to adult care in patients affected with childhood-onset IEI aimed at improving clinical practice in this area, with a helpful focus on different requirements for specific types of IEI [25, 26]. Future work could also focus on guidelines to support the clinical management of IEI patients with certain comorbidities (such as learning disabilities) and those requiring long-term follow-up after corrective or novel treatments (such as stem cell therapies).

This study was the first large-scale survey of transition practices for primary immunodeficiency and autoinflammatory conditions in Europe. However, it is important to recognize that there may be a bias in reporting related to the geography of the responding centers. The majority of the response sites in this study were based in the UK, Belgium, Italy, and Spain, and these findings may not be representative of transition programs and patient cohorts in regions with fewer response sites, like Central and Eastern Europe and Scandinavia. The challenges are likely to be different in different regions which may have an impact for translating guidelines to practice. In addition, most information came from countries with established Adult Immunology Services. This study did not examine a patient and family/carer perspective, which may be different to a professional overview. Hence, it will be important for future research to explore patient and family/carer experiences of transition and their reported difficulties with the process. Finally, it is possible that findings from this study were affected by selection bias—with centers already invested in transition practices being more likely to respond to the survey. Hence, results from this survey may not reflect transition policies in centers with less-established transition programs.

Further work is needed to develop comprehensive national and international illness-specific transition guidelines for PID and AI. These should establish practices to enable young people to develop independence with respect to their healthcare and address aspects of life and wellbeing impacted by specific health conditions. Future work should also consider factors conducive to successful and unsuccessful transition, for example, avoiding transfer of care during active disease phase, and any guidelines should highlight the need to understand the proportion of young patients who are lost to follow-up or show a decline in treatment adherence subsequent to the transfer of care. Accordingly, the next step for the RITA–ERN transition group is to develop good practice recommendations for transition in these populations and identify the outcome measures that can be used in future studies to assess the impact of transition guidance on the long-term health of adults living with childhood-onset IEI.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bousfiha A, Jeddane L, Picard C, Al-Herz W, Ailal F, Chatila T, et al. Human inborn errors of immunity: 2019 update of the IUIS phenotypical classification. J Clin Immunol. 2020;40(1):66–81.

Tangye S, Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Cunningham-Rundles C, Franco J, Holland S, et al. The ever-increasing array of novel inborn errors of immunity: an interim update by the IUIS committee. J Clin Immunol. 2021;41(3):666–79.

Broderick L. Hereditary autoinflammatory disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2019;39(1):13–29.

Betrains A, Staels F, Schrijvers R, Meyts I, Humblet-Baron S, De Langhe E, et al. Systemic autoinflammatory disease in adults. Autoimmun Rev. 2021;20(4):102774.

Ebadi M, Aghamohammadi A, Rezaei N. Primary immunodeficiencies: a decade of shifting paradigms, the current status and the emergence of cutting-edge therapies and diagnostics. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2015;11(1):117–39.

Barlogis V, Mahlaoui N, Auquier P, Pellier I, Fouyssac F, Vercasson C, et al. Physical health conditions and quality of life in adults with primary immunodeficiency diagnosed during childhood: a French reference center for PIDs (CEREDIH) study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(4):1275-1281.e7.

Barlogis V, Mahlaoui N, Auquier P, Fouyssac F, Pellier I, Vercasson C, et al. Burden of poor health conditions and quality of life in 656 children with primary immunodeficiency. J Pediatr. 2018;194:211-217.e5.

Mahlaoui N, Warnatz K, Jones A, Workman S, Cant A. Advances in the care of primary immunodeficiencies (PIDs): from birth to adulthood. J Clinic Immunol. 2017;37(5):452–60.

Christie D, Viner R. Chronic illness and transition: time for action. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 2009;20(3):981–xi.

Blum R, Garell D, Hodgman C, Jorissen T, Okinow N, Orr D, et al. Transition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions. J Adolesc Health. 1993;14(7):570–6.

Foster H, Minden K, Clemente D, Leon L, McDonagh J, Kamphuis S, et al. EULAR/PReS standards and recommendations for the transitional care of young people with juvenile-onset rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(4):639–46.

Roberts G, Vazquez-Ortiz M, Knibb R, Khaleva E, Alviani C, Angier E, et al. EAACI Guidelines on the effective transition of adolescents and young adults with allergy and asthma. Allergy. 2020;75(11):2734–52.

Papa R, Cant A, Klein C, Little M, Wulffraat NM, Gattorno M, et al. Towards European harmonisation of healthcare for patients with rare immune disorders: outcome from the ERN RITA registries survey. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):33.

Pai ALH, Ostendorf HM. Treatment adherence in adolescents and young adults affected by chronic illness during the health care transition From pediatric to adult health care: A literature review. Child Health Care. 2011;40(1):16–33.

Lotstein DS, Seid M, Klingensmith G, Case D, Lawrence JM, Pihoker C, et al. Transition from pediatric to adult care for youth diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):e1062–70.

Foster BJ. Heightened graft failure risk during emerging adulthood and transition to adult care. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30(4):567–76.

Asad H, Collins IJ, Goodall RL, Crichton S, Hill T, Doerholt K, et al. Mortality and AIDS-defining events among young people following transition from paediatric to adult HIV care in the UK. HIV Med. 2021;22(8):631–40.

Tumiene B, Graessner H. Rare disease care pathways in the EU: from odysseys and labyrinths towards highways. J Community Genet. 2021;12(2):231–9.

Nagra A, McGinnity PM, Davis N, Salmon AP. Implementing transition: ready steady go. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2015;100(6):313–20.

Zhang LF, Ho JS, Kennedy SE. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of transition readiness assessment tools in adolescents with chronic disease. BMC Pediatr. 2014;9(14):4.

Stinson J, Kohut SA, Spiegel L, White M, Gill N, Colbourne G, et al. A systematic review of transition readiness and transfer satisfaction measures for adolescents with chronic illness. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2014;26(2):159–74.

Willis ER, McDonagh JE. Transition from children’s to adults’ services for young people using health or social care services (NICE Guideline NG43). Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2018;103(5):253–6.

Colver A, Rapley T, Parr JR, Mcconachie H, Dovey-Pearce G, Le Couteur A et al. Facilitating the transition of young people with long-term conditions through health services from childhood to adulthood: the transition research programme. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library, 2019. 244 p. (Programme Grants for Applied Research; 4).

Growing older with a PID: transition of care and ageing [Internet]. Ipopi.org. 2017 [cited 8 November 2021]. Available from: https://ipopi.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/IPOPI-recommendations-transition-of-care-and-ageing-FINAL_web.pdf

Cirillo E, Giardino G, Ricci S, Moschese V, Lougaris V, Conti F, et al. Consensus of the Italian Primary Immunodeficiency Network on transition management from pediatric to adult care in patients affected with childhood-onset inborn errors of immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(5):967–83.

Georgin-Lavialle S, Hentgen V, Truchetet ME, Romier M, Hérasse M, Maillard H, et al. La transition de la pédiatrie à l’âge adulte: recommandations de prise en charge de la filière des maladies auto-immunes et auto-inflammatoires rares FAI2R [Transition from pediatric to adult care: Recommendations of the French network for autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases (FAI2R)]. Rev Med Interne. 2021;42(9):633–8.

RITA-ERN Transition Working Group Consortium Collaborators

Wouters, C. MD PhD30,31, Meyts, I. MD PhD30,31, van der Werff ten Bosch, J. E. MD, PhD32, Goffin, L. MD33, Ogunjimi, B. MD PhD34-36, Gilliaux, O. MD37,38, Kelecic, J. MD39, Jelusic, M. MD PhD40, Fingerhutová, Š. MUDr41, Sediva, A. MD PhD42, Herlin, T. MD PhD43, Seppänen Mikko R. J. MD PhD44, Aalto, K. MD PhD45, Ritterbusch, H. RN19, Insalaco, A. MD46, Moschese, V. MD PhD47, Plebani, A. Professor of Pediatrics MD PhD23, Cimaz. R. MD48, Canessa, C. MD49, Dellepiane, R. M. MD50, Carrabba, M. MD PhD51, Barzaghi, F. MD52, Tommasini, A. MD PhD53, van Laar, J.A.M. MD PhD11, Wulffraat, N. M. Prof MD PhD54, Marques L. MD55, Carreras, C. MD56, Sánchez-Manubens J. MD PhD57, Alsina, L. MD PhD58,59, Seoane Reula, M. E. MD PhD60, Mendez-Echevarria, A. MD PhD61,62, Gonzales-Granado, L. I. MD63-65, Santamaria M. MD PhD66, Neth, O. MD PhD67, Ekwall, O. MD PhD25,68, Brodszki, N. MD PhD69, Hague, R. MD70, Devlin, L. A. MB BChBAO MRCPCH MD FRCPath71, Brogan, P. MBChB PhD72, Arkwright, P.D. MB PhD73, Riordan, A. MD74, McCann, L. MRCPCH MMedSc74, McDermott, E. FRCP, FRCPath, DM75, Faust, S. N. PhD76,77, Carne, E. MSc78

30Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Pediatric Immunology, KU Leuven - University of Leuven, B-3000, Leuven, Belgium

31Department of Pediatrics, Division Pediatric Rheumatology, University Hospitals Leuven, B-3000, Leuven, Belgium

32Department of Pediatrics UZ Brussel, Brussels, Belgium

33Pediatric Rheumatology Department, Hôpital Universitaire des Enfants Reine Fabiola (HUDERF) – Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium

34Division of Paediatric Rheumatology, Department of Paediatrics, Antwerp University Hospital, Antwerp, Belgium

35Division of Paediatric Rheumatology, Department of Rheumatology, Ziekenhuis Netwerk Antwerpen, Antwerp, Belgium

35Division of Paediatric Rheumatology, Department of Paediatrics, Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel, Jette, Belgium

36Centre for Health Economics Research and Modeling Infectious Diseases, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

37Pediatric department, CHU of Charleroi (Hôpital civil Marie Curie), Charleroi, Belgium

38Laboratory of experimental medicine (ULB222), Medicine faculty, Université libre de Bruxelles, ISPPC, CHU of Charleroi, Charleroi (Lodelinsart), Belgium.

39University Hospital Center Zagreb, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Clinical Immunology, Allergology, Respiratory Diseases and Rheumatology, Kišpatićeva 12, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia

40Professor of Paediatrics, University of Zagreb, School of Medicine, Croatia

41Centre for Paediatric Rheumatology and Autoinflammatory Diseases, Department of Paediatrics and Inherited Metabolic Disorders, 1st Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, General University Hospital in Prague, Ke Karlovu 2, 128 08 Prague 2, Czech Republic

42Department of Immunology, Motol University Hospital, 2nd Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic

43Department of Pediatrics, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark

44Rare Disease and Pediatric Research Centers, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Central Hospital, Finland

45Pediatric Rheumatologist, Pediatric Rheumatology, New Children’s Hospital, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland

46Division of Rheumatology, Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù, 00146 Roma, Italy

47Pediatric Immunopathology and Allergology Unit, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Policlinico Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy, Saint Camillus International University of Health and Medical Sciences, Italy

48Department of Clinical Sciences and Community Health, University of Milano, Italy

49Division of Pediatric Immunology, Department of Health Sciences, University of Florence and Meyer Children’s Hospital, Florence, Italy

50Department of Pediatrics Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico Milano, Italy

51Immunodeficiency and Autoinflammatory Disorders Centre, Internal Medicine Department. Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico of Milan, Italy

52San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, Pediatric Immunohematology and Bone Marrow Transplantation Unit, Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy

53Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo and University of Trieste, Trieste, Italy

54Department of Pediatric Rheumatology, Pediatrics Division, University Medical Center Utrecht, University Utrecht, the Netherlands

55Paediatric Immunodefciencies and Infectious Diseases Unit, Paediatric Department, Department Centro Materno-Infantil do Norte, CHUPorto, Porto, Portugal

56Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia

57Pediatric Rheumatology Unit, Department of Pediatrics, Hospital Universitari Parc Taulí Sabadell, Spain

58Pediatric Clinical Immunology and Primary Immunodeficiencies Unit, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona, Spain

59Functional Unit of Immunology, Sant Joan de Déu Hospital, Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

60Multidisciplinary Immunodeficiencies Unit of adults and children, Gregorio Marañon Hospital, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain

61Department of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, La Paz University Hospital, 28046 Madrid, Spain

62Translational Research Network in Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 28009 Madrid, Spain

63Primary Immunodeficiencies Unit, Pediatrics Hospital 12 octubre, Madrid, Spain

64Instituto de Investigación, Hospital 12 octubre (imas12), Madrid, Spain

65School of Medicine, Complutense University, Madrid, Spain

66Prof Immunology, H.U. Reina Sofia, Faculty of Medicine, University of Cordoba, Cordoba, Spain

67Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Rheumatology and Immunology Unit, Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Institute of Biomedicine of Seville (IBIS)/ Universidad de Sevilla/CSIC, Red de Investigación Translacional en Infectología Pediátrica RITIP, Seville, Spain

68The Department of Rheumatology and Inflammation Research, The Sahlgrenska Academy at University of Gothenburg, Sweden

69Department of Pediatric Oncology and Immunology, Children’s Hospital, Skåne University Hospital, Lund, Sweden

70Royal Hospital for Children, Glasgow, Scotland

71Regional Immunology Service, Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast, BT126BA

72UCL GOS Institute of Child Health, London UK

73Department of Paediatric Allergy & Immunology, Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, Manchester, UK

74Alder Hey Children’s Foundation Trust, Liverpool, UK

75Clinical Immunology and Allergy Department, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust

76NIHR Southampton Clinical Research Facility and Biomedical Research Centre, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, Southampton, SO16 6YD, UK

77Faculty of Medicine and Institute for Life Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, SO17 1BJ, UK

78Immunodeficiency Centre for Wales, Cardiff, UK

Funding

This study was supported by the ERN-RITA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

MI, BN, NM, LO, LR-S, HL, GH, MZA, AG, VD, RR, LS, CV, ARG, SS, JN, KW, ASK, JA, MC, TA, SB, PS-P, SOB, and MC contributed to the study conception, design, and material preparation. Data collection was performed the RITA-ERN Transition Working Group Consortium. Data analysis was performed by MI, BN, SOB, and MC. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MI, SOB, and MC, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

All authors agreed to this publication.

Consent to participate

Consent to participate was requested in the email invitation sent to professionals which included information about what data would be collected and how data provided would be used.

Conflict of interest

BN was contracted to work on this project by Royal Free Hospital and Great Ormond Street Hospital; SB1 has received grant support from the European Union, National Institute of Health Research, UCLH and GOSH/ICH Biomedical Research Centers, and CSL Behring and personal fees or travel expenses from Immunodeficiency Canada/IAACI, CSL Behring, Baxalta US Inc, and Biotest; MC1 has received grant support from the National Institute of Health Research, PIDUK, CSL Behring and the Royal Free Charity and personal fees or travel expenses from Biotest, BPL, CSL Behring, Grifols, HAEUK, Shire, and Takeda; LR-S has received consulting fees from Pfizer and AbbVie, and support for attending meetings or travel expenses from Novartis, Sobi, Medac, AbbVie, and Pfizer; ARG has received research funding from Mallinckrodt and JAZZ Pharmaceuticals; AG and ASK receive research funding from CSL Behring and Takeda; SB2 has received payment or honoraria for speakers bureaus from Sobi and Novartis; PSP has received grant support from the European Union, Instituto Carlos III, Grifols, and CSL Behring and personal fees or travel expenses from CSL Behring, Takeda, and Grifols; JA has received grant support from the European Union, Insituto Carlos III, Fundación Daniel Bravo, research support from Novartis, Sobi, Novimmune, Roche, Pfizer, Lilly, AbbVie, and Amgen, and personal fees or travel expenses from Novartis, Sobi, Roche, Pfizer, Lilly, AbbVie, and Gebro; MC2 has received speaking fees from Novartis Farma, AbbVie, Sobi, and Pfizer; KW is on the advisory boards for Shire Deutschland GmbH and LFB biomedicals, and has received grant support from BMS, honoraria for lectures, symposiums, and meetings from CSL Behring and Shire, and travel expenses from Shire; HL is the President-Elect for ISSAID, Council Member of the Nephrology section of the Royal Society of Medicine, and Vice-Chair of MHRA EAG; HL has received grant support for ImmunAID from EUH2020, consulting fees from Novartis, Sobi, and Roche, payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Novartis and Sobi, and support for attending meetings and/or travel from DADA2 patient society and Sobi; IM is the president of European Society for Immunodeficiencies, a board member of Astra Zeneca Foundation, and a senior clinical investigator at FWO Vlaanderen, IM has received grant support from CSL Behring Primary Immunodeficiencies Chair, European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, FWO Vlaanderen, VIB Grand Challenges Program, KU Leuven Onderzoeksraad, and the Jeffrey Modell Foundation, IM has received honoraria for lecturing by CSL Behring; JVDH has received consulting fees from Novartis and Sobi, and payment for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Sobi; LG is a participant on the Data Safety Monitoring board or Advisory Board for Novartis, and has received payment for presentations from Novartis, and support for attending meetings and/or travel expenses from AbbVie and Novartis; ŠF has received payment or honoraria for presentations and meeting/travel expenses from Sobi; AS has received payment or honoraria for presentations, lectures, speakers bureaus, educational events, or manuscript writing from Takeda, CSL Behring, and Octapharma; TH has received payment for lectures from Novartis, and support for attending meetings from Sobi; TRL is a participant on the advisory board for Sanofi-Pasteur, and has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Takeda; VM is the president of the Vaccine Committee of the Italian Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, and has received personal fees from Takeda and CSL Behring, and travel/meeting expenses from CSL Behring; JAMvL has received payment for expert testimony from Amgen and Sobi; NMW is the coordinator of ERN-RITA, and a participant in an investigator-initiated study on the effect of intranasal administration of palivizumab on respiratory syncytial virus-associated infection. NMW has received grant support from ZONMW and ReumaNederland, and consulting fees from Sanofi-Genzyme and UCB; FOR has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Novartis; PČ has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Takeda; CC is a pediatric representative on the Committee of primary Immunodeficiencies Hospital Universitario y Politecnico La Fe, and has received support for this manuscript from Hospital Universitario y Politecnico La Fe—Valencia, and support for attending meetings and/or travel expenses from CSL Behring; JS-M has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Pfizer, and meeting/travel expenses from AbbVie; LA has received consulting fees from CSL Behring, Grifols, Shire, and Takeda, honoraria for lectures from CSL Behring, Shire, and Takeda, and meeting/travel expenses from CSL Behring, Grifols, Shire, and Takeda; MERS participates on the Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board for Takeda has received meeting/travel expenses from CSL Behring and ALK, and payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Takeda and CSL Behring; LIG-G is a medical advisor for AEDIP and has received grant support from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, co-financed with FEDER funds; OE has received grant support from the Swedish Research Council; LAD has received funding to attend an educational event from CSL, and support to attend a speaker meeting for GPs from ALK; AJJW is a participant on the advisory board for Orchard Therapeutics; PB is a trustee of UK charity Societi, treasurer of International Society of Systemic Autoinflammatory Diseases, and participant on the NOVARTIS gene therapy advisory board, PB has received grant support from the European Union for an investigator-led clinical trial of Prednisolone in Kawasaki disease, consulting fees from Sobi and Novartis, payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Sobi, Roche, and Novartis, and payment for expert testimony from KD Scotland; SS is the Chair of UKPIN, and has received grant support from CSL Behring, and consulting fees from Takeda and Novartis; SF is a participant on the advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Medimmune, Sanofi, Pfizer, Seqirus, Sandoz, Merck, and J&J, and was the chair of UK NICE Sepsis (2014–2016) and Lyme Disease (2016–2018) Guidelines, SF has received the NIHR Senior Investigator Award, grant support from Pfizer, Sanofi, GSK, J&J, Merck, AstraZeneca, and Valneva, and payment for symposiums from Pfizer. No other authors have competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Highlights:

1. An effective transition from pediatric to adult services process improves long-term outcomes for young people with chronic conditions

2. This is the first survey to understand transition practices in Europe for young people with Inborn Errors of Immunity

3. The study highlights variation in practice and a need for national and international guidelines for transition of young people with Inborn Errors of Immunity

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Israni, M., Nicholson, B., Mahlaoui, N. et al. Current Transition Practice for Primary Immunodeficiencies and Autoinflammatory Diseases in Europe: a RITA-ERN Survey. J Clin Immunol 43, 206–216 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-022-01345-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-022-01345-y