Abstract

This study advances the understanding of the mechanisms that link past challenge and hindrance stressors to resilience outcomes, as indicated by emotional and psychosomatic strain in the face of current adversity. Building on the propositions of Conservation of Resources Theory and applying them to the challenge-hindrance framework, we argue that challenge and hindrance stressors experienced in the past relate to different patterns of affective reactivity to current adversity, which in turn predict resilience outcomes. To test these assumptions, we collected data from 134 employees who provided information on work stressors between April 2018 and November 2019 (T0). During the first COVID-19 lockdown (March/April 2020), the same individuals participated in a weekly study over the course of 6 weeks (T1–T6). To test our assumptions, we combined the pre- and peri-pandemic data. We first conducted multilevel random slope analyses and extracted individual slopes indicating affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity in positive and negative affect. Next, results of path analyses showed that past challenge stressors were associated with lower affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity in positive affect, and in turn with lower levels of emotional and psychosomatic strain. Past hindrance stressors were associated with greater affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity in positive and negative affect, and in turn to higher strain. Taken together, our study outlines that past work stressors may differentially affect employees’ reactivity and resilient outcomes in the face of current nonwork adversity. These spillover effects highlight the central role of work stressors in shaping employee resilience across contexts and domains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Throughout their lives, most individuals experience adversity (e.g., Bonanno, 2005) which represents a major risk factor for the development of psychopathology (Green et al., 2010). Individual resilience prevents adversity-related declines in psychological well-being and mental health (Fisher et al., 2019; King et al., 2016). Consequently, researchers strive to identify the antecedents of resilience and throughout this process outline the central role of past experiences (e.g., King et al., 2016; Seery et al., 2010; Ungar, 2011). In this study, we focus on the experience of past work stressors and examine how they influence employees’ demonstration of resilience outcomes, that is the maintenance of psychological well-being in the face of current adversity, specifically COVID-19-related adversity. Note that we refer to adversity as a stressful experience that lies outside the “business-as-usual” context (i.e., the COVID-19 pandemic), whereas work stressors represent stressful experiences that employees encounter frequently within their work environment (see Britt et al., 2016; Kuntz et al., 2017).

To date, a handful of studies have examined the relationship between work stressors and resilience, with resilience operationalized as a capacity, that is, a hypothetical but not demonstrated ability to maintain health and functioning in the face of adversity (Crane & Searle, 2016; Jannesari & Sullivan, 2021; Kunzelmann & Rigotti, 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). These studies conjointly drew on the challenge-hindrance framework (Cavanaugh et al., 2000; O’Brien & Beehr, 2019) and showed that challenge stressors positively whereas hindrance stressors negatively relate to employees’ resilience capacity. However, research remains limited in two important ways. First, the mechanisms that mediate the relationship between past work stressors and resilience outcomes remain un(der)explored. That is, how do past work stressors influence the way that individuals react to current adversity, which in turn predicts health and functioning in the face of current adversity? Identifying such explanatory mechanisms is essential to advance our understanding of the role that everyday stressors play in predicting employee resilience, and further facilitates the development of more targeted programs that organizations can offer to prevent stress-related pathology (e.g., Kalisch et al., 2015). Second, resilience researchers showed that measuring resilience as a hypothetical capacity does not adequately predict actual, real-life adaptation to adversity (Bonanno, 2012; Britt et al., 2016; Waaktaar & Torgersen, 2010). As a result, research to date does not allow for the conclusion that work stressors are related to positive adaptation in the face of real-life adversity.

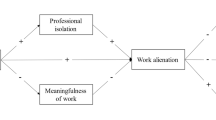

Accordingly, in this study, we aim to advance the understanding of the mechanisms that link past work stressors to resilience outcomes in the face of current real-life adversity. To this end, we draw on the Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory (Hobfoll, 1989) as an overarching theoretical model and combine it with the challenge-hindrance framework (Cavanaugh et al., 2000) as well as the concepts of stress inoculation (Meichenbaum, 1977) and stress sensitization (Post, 1992). Specifically, we argue that past challenge stressors are associated with an inoculation process in which individuals experience a net resource gain that expands their coping capacities by overcoming the challenges. This prevents the experience of acute psychological distress in the form of heightened affective reactivity in the face of current adversity, that is decreasing positive and increasing negative affect (see e.g., Cohen et al., 2005; Houben et al., 2015). Lower affective reactivity, in turn, is expected to facilitate the demonstration of resilience outcomes, namely the maintenance of psychological well-being in the face of adversity (e.g., Fredrickson et al., 2003; Hobfoll, 2011; O’Neill et al., 2004). In contrast, hindrance stressors are expected to trigger a sensitization process characterized by resource losses, resulting in diminished coping capacities and thus increased affective reactivity to adversity and lower well-being (e.g., Hobfoll, 2011; Post, 1992). Thus, taken together, we propose that everyday work stressors experienced in the past influence individuals’ affective reactivity to current adversity, which in turn predicts emotional and psychosomatic well-being in the face of current adversity. Figure 1 illustrates our conceptual research model.

Conceptual model: challenge and hindrance stressors experienced in the past as antecedents of the resilience process to current adversity. Note. Direct paths from challenge and hindrance demands at T0 to outcome variables at T6 are omitted for clarity of presentation. Affective reactivity was operationalized as individual slopes extracted from multilevel analysis. Slopes indicated an individual’s average weekly relationship between COVID-19-related adversity and positive as well as negative affect

This study makes three main contributions. First, we go beyond previous research that focused on the direct impact of work stressors on hypothetical resilience (e.g., Crane & Searle, 2016; Jannesari & Sullivan, 2021). By integrating the propositions of COR theory with the challenge-hindrance framework, we offer an explanation for how work stressors experienced in the past may influence resilience outcomes in the face of current adversity, namely through shaping affective reactivity to current adversity. This approach not only enhances our understanding of the stressor-resilience relationship and broadens the nomological network of the challenge-hindrance framework but also holds important implications for stress research in general. Specifically, it advances our understanding of the long-term effects of stressors on strain. This is crucial given that studies that have examined the stressor-strain relationship while controlling for autoregressive effects found heterogeneous relationship patterns, with relationships being positive, nonsignificant, or even negative (Guthier et al., 2020). Stressor-induced changes in affective reactivity to future adversity may provide an explanation for this heterogeneity.

Second, we acknowledge the assumption inherent in COR theory and the concepts of stress inoculation and sensitization that past experiences shape reactivity and positive adaptation to different forms of future adversity across contexts and domains (e.g., Belda et al., 2016; Dienstbier, 1989; Freedy & Hobfoll, 1994; Hobfoll, 2011). Building on this assumption, we investigate whether past work stressors predict the way individuals adapt to current adversity that arises from a context outside the work setting, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The important implications of such spillover effects are evident, as they may serve as a foundation for facilitating positive adaptation not only to one type of adversity but to multiple or all forms of adversity (e.g., Kalisch et al., 2015) through work design.

Third, we address the criticism from resilience researchers who have highlighted the limitations of operationalizing resilience as a hypothetical construct (Britt et al., 2016; Waaktaar & Torgersen, 2010), an approach commonly used in previous studies of the stressor-resilience relationship (e.g., Crane & Searle, 2016; Jannesari & Sullivan, 2021). To overcome this limitation, we specifically focus on observing affective reactivity to adversity and the subsequent maintenance of well-being, indicating the demonstration of resilience (Fisher et al., 2019). By adopting this perspective, we gain valuable insights into how work stressors contribute to shaping adaptive processes in the face of real-life adversity.

Theoretical Background

A Conservation of Resource Perspective on Individual Resilience

COR theory was developed by Hobfoll (1989) to explain human motivation and the sources of psychological distress (see also Halbesleben et al., 2014). The central tenet of COR theory is that humans seek to protect their current resources and acquire new ones, where resources are defined as objects, personal characteristics, conditions, or energies that are valued by an individual (Hobfoll, 1989) and that facilitate goal attainment (Halbesleben et al., 2014). According to the theory, psychological distress occurs when there is (a) a threat of a net loss of valued resources, (b) an actual net loss of valued resources, or (c) a failure to gain valued resources after significant effort (Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll et al., 2018). Hobfoll (1989) further outlines that achieving overall or net resource gains is an active process in which individuals must invest resources, such as energy, in order to gain new resources, such as self-efficacy. In addition, resource gains and losses are likely to affect individuals in the long run, as they can trigger gain and loss spirals, respectively. That is, individuals who have gained resources are more capable of additional resource gains (i.e., gain spirals), whereas an initial resource loss begets future losses (i.e., loss spirals, Hobfoll, 2001; Hobfoll et al., 2018).

Importantly, according to COR theory, resource gains and losses influence an individual’s responses to future stress events or adversity and thus their resilience (Freedy & Hobfoll, 1994; Hobfoll, 2011). Specifically, resource gains relate to having a wider range of resources that expand an individual’s coping capacity, facilitating positive adaptation, preventing further resource losses due to adversity, and consequently preventing the experience of psychological distress and inhibited well-being. In contrast, resource losses relate to lower resource levels which are associated with insufficient coping capacities and increased vulnerability to future stress events, leading to additional resource losses and, consequently, increased psychological distress and lower well-being (Freedy & Hobfoll, 1994; Hobfoll, 1989). Taken together, COR theory posits that resource gains and losses will shape individual resilience to future adversity, with gains leading to increased resilience and losses leading to increased vulnerability. In what follows, we will apply a stressor lens to these propositions of COR theory, incorporating the challenge-hindrance framework and the concepts of stress inoculation and stress sensitization into the theoretical model.

Challenge-Hindrance Framework: Stressor-Induced Net Resource Gains and Losses

Building on transactional stress theory (Lazarus & Folkman, 1987), Cavanaugh et al. (2000) introduced the challenge-hindrance framework to the stress literature, arguing that there are two distinct types of work stressors: challenge and hindrance stressors (see also LePine, 2022). Overcoming either type of stressor requires individuals to invest energy resources and effort, and thus is likely to result in strain (Cavanaugh et al., 2000). In the case of challenge stressors, the investment of energy resources and effort is expected to lead to the acquisition of other valued resources (see also Hobfoll, 1989), including the experience of mastery, goal attainment, and personal development such as increases in self-efficacy (e.g., Webster et al., 2010), resulting in an overall net resource gain (see also Cavanaugh et al., 1998). A net gain in resources following exposure to challenges is also the underlying principle of the concept of stress inoculation (Meichenbaum, 1977). The concept suggests that much like exposure to pathogens strengthens immunity to infectious disease; exposure to challenge stressors provides a training opportunity to acquire effective coping strategies and to develop regulatory capacities which strengthens individual resilience to future adversity (e.g., DiCorcia & Tronick, 2011; Meichenbaum, 1977). Similar processes are described by Bandura (1977), who outlines that performance accomplishments (i.e., mastery experiences) represent the primary source of self-efficacy which in turn facilitates positive adaptation to adversity (see also Bandura, 2001). Resources built through challenge-induced stress inoculation are further expected to positively affect adaptation to adversity across contexts (i.e., cross-inoculation) and thus likely enhance resilience to qualitatively distinct forms of adversity (see Ayash et al., 2020; Dienstbier, 1989; Freedy & Hobfoll, 1994; Schilbach et al., 2021).

In contrast, in the case of hindrance stressors, the investment of energy resources and effort is not met by any resource gains in return (e.g., Webster et al., 2010). In fact, hindrance stressors represent barriers to goal attainment and are related to the experience of failure and frustration, and thus impede personal development (e.g., Cavanaugh et al., 2000; Kern et al., 2021; Shawney & Michel, 2022). Accordingly, hindrance stressors are associated with a net resource loss and the investment of energy and effort is not accompanied by a subsequent gain of valued resources (see e.g., Crane & Searle, 2016; Webster et al., 2010). According to COR theory, such losses are associated with psychological distress and increased vulnerability to future adversity (Hobfoll, 1989, 2011). The concept of stress sensitization which was developed to explain why stressors can lead to affective disorders (Post, 1992), makes similar assumptions. It argues that exposure to negative stressful experiences (e.g., hindrance stressors) triggers hyperreactivity to the same or different stressors in the future (Belda et al., 2015; Post, 1992; Stroud, 2020). Thus, similar to the concept of stress inoculation, stress sensitization posits a cross-context effect in which individuals experience heightened stress reactivity to a variety of different stressful events (i.e., cross-sensitization). Such heightened reactivity inhibits positive adaptation and represents an important risk factor for individual resilience (e.g., Rutter, 2012). Researchers illustrated that (cross-)sensitization likely occurs via maladaptive cognitive and behavioral processes which lead to continuous resource losses. For example, Farb et al. (2015) proposed that sensitization occurs through dysphoric attention (i.e., fixation on the negative) and dysphoric elaboration (i.e., rumination), which are related to the formation of negative schemata, in which individuals develop a negative view of the self and the world. These processes likely lead to a loss of valued resources including efficacy beliefs, or social support (e.g., Lyubomirsky et al., 1999; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). Such losses render individuals increasingly vulnerable to subsequent stressful events and inhibit their resilience (Friedmann et al., 2016).

The Link Between Past Work Stressors and Adaptation to Current Adversity

Resilience is a process of positive adaptation to adversity. Fisher et al. (2019) outline that adversity, resilience mechanisms, and resilience outcomes represent the elements of the resilience process. Adversity indicates that an individual is facing negative and stressful life experiences (e.g., Kuntz et al., 2017; Obradović et al., 2012). It can be viewed on a continuum characterized by the intensity, the chronicity, the predictability, and the frequency of events (e.g., Britt et al., 2016; Estrada et al., 2016). Adversity further represents a precondition without which the resilience process cannot be observed (e.g., Britt et al., 2016; Fisher & Law, 2021). In this article, we refer to adversity as an event that occurs outside of the “business-as-usual” context (i.e., COVID-19 adversity), following the definition of Kuntz et al. (2017; see also Britt et al., 2016). However, we note that work stressors (e.g., overload) may also constitute adversity, especially if they are chronically present (see Fisher et al., 2019).

When individuals face adversity, they will exhibit psychological and/or physiological reactions and engage in strategies to overcome adversity. Fisher et al. (2019) referred to these reactions and strategies as resilience mechanisms. Optimally, these mechanisms allow individuals to exhibit resilient outcomes that indicate health, functioning, well-being, or the absence of problems (e.g., burnout) despite adversity (Fisher et al., 2019; Hartmann et al., 2020). In the following sections, we will elaborate on the elements of the resilience process in more detail and derive their hypothesized relationships with past work stressors.

Adversity

In this study, we use the COVID-19 pandemic as an adverse event, specifically the first lockdown in Germany, which likely induced adversity in several ways. For example, concerns about one’s own health and the health of loved ones represent highly adverse experiences (Trougakos et al., 2020). Additionally, individuals were confronted with changes in daily life, such as social distancing, the inability to pursue hobbies, or the need to cope with increased private stressors (Rudolph et al., 2021). As such, the COVID-19 pandemic provides an appropriate context in which to study resilience (see e.g., Prime et al., 2020).

However, not everyone was affected by the pandemic in the same way. While some lost a loved one, experienced financial worries, or had to cope with changing childcare arrangements, others were more fortunate. Additionally, given the dynamic nature of the pandemic and the frequent changes in regulations and restrictions as well as potentially varying levels of personal (e.g., energy) and structural resources (e.g., social support), there are likely to be inter- and intrapersonal differences in the adversity experienced. For example, during one week, parents may have been able to send their children to school, while the following week, schools may have had to close due to infections. To account for these inter- and intraindividual differences, we asked employees weekly about the extent to which they experienced COVID-19 adversity, so that we obtained an individual adversity indicator for each person and each week. In addition to experiencing different levels of adversity, individuals will also differ in their affective responses to changing adversity. For example, while person A may remain calm and serene despite increasing adversity, person B may become increasingly nervous and anxious. In what follows, we will discuss the relevance of such affective reactivity and elaborate on how it may explain the relationship between past work stressors and resilience outcomes in the face of current adversity.

Affective Reactivity as a Resilience Mechanism

We focus on affective reactivity, which is the tendency to experience negative changes in affective states in response to specific events, in this study COVID-19 adversity (Sliwinski et al., 2009; Spear, 2009), as a resilience mechanism (i.e., how individuals react to adversity, Fisher et al., 2019). Fisher et al. (2019) emphasize that greater reactivity to adversity results in “increasingly large deviations from normal or optimal functioning, which is indicative of lower resilience” (p. 605). In simpler terms, as reactivity to adversity increases, the likelihood of maintaining good health, functioning, and ultimately demonstrating resilience decreases. Note that affective reactivity is only one of several potential resilience mechanisms. Fisher et al. (2019) provide an overview of other relevant mechanisms, such as cognitive appraisal, suppression of competing activities, or seeking social support. We chose to focus on affective reactivity as a resilience mechanism because it is an indicator of acute psychological distress and vulnerability to stressors and adversity (e.g., Charles et al., 2013; O’Neill et al., 2004; Piazza et al., 2013). In addition, it can be seen as a reflection of the adequate resources that individuals have to cope with an adverse situation: According to COR theory, when resources are adequate, individuals can protect themselves from adversity-induced resource losses by employing appropriate coping strategies and making effective use of existing resources. When resource losses are not experienced or anticipated, personal harm can be prevented, and thus, individuals will not respond to adversity with psychological distress (e.g., Hobfoll et al., 2018), that is, affective reactivity. In contrast, when resources are insufficient, individuals will be unable to protect themselves from additional adversity-induced resource losses. These actual or anticipated resource losses, in turn, lead to vulnerability to future adversity and thus to greater affective reactivity (e.g., Hobfoll, 2011; Hobfoll et al., 2018).

To date, affective reactivity has mainly been studied in the context of the negative valence of affect (i.e., aversive mood states such as anger, contempt, fear, and nervousness; Watson et al., 1988). The positive valence (i.e., the extent to which a person feels enthusiastic, active, and alert; Watson et al., 1988) of affect is only rarely included in the study of affective reactivity (Ong et al., 2006). However, we argue that the negative and positive valence need to be considered because they serve different functions within the resilience process (e.g., Ong et al., 2006; Posner et al., 2005). Notably, research based on the broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 2001) has demonstrated that negative and positive affect play different roles in positive adaptation. For instance, Fredrickson et al. (2003) found that negative affect following adversity had a positive whereas positive affect had a negative correlation with the development of depression. In addition, Tugade and Fredrickson (2004) showed that positive affect was linked to reduced cardiovascular reactivity and faster cardiovascular recovery during acute stress. These findings are further supported by Folkman and Moskowitz’s review (2000), suggesting that a lesser decrease in positive affect in response to stress signals the potential for mastery or gain and holds significant adaptive value. Accordingly, we included reactivity to COVID-19 adversity in positive and negative affect as a resilience mechanism.

Previously, we argued that past challenge stressors may act as inoculation stressors by promoting the experience of mastery and personal growth, resulting in a net gain of resources (see e.g.,Cavanaugh et al., 2000 ; Crane & Searle, 2016 ; Webster et al., 2010). For example, individuals who have faced and successfully overcome challenge stressors in the past may believe that they can adequately cope with difficult and stressful situations, that is, they developed efficacy beliefs (e.g., Dienstbier, 1989; Webster et al., 2010). Such efficacy beliefs add to the coping repertoire of individuals, allowing them to cope more effectively with future adversity (Bandura, 2001). Adequate resources, in turn, prevent (anticipated) resource loss and thus the experience of psychological distress (e.g.,Hobfoll, 1989 ; Hobfoll et al., 2018). Initial empirical support for this line of argument comes from Dienstbier and PytlikZillig (2016), who outlined that certain activities (e.g., mental challenges) are associated with psychological toughness including emotional stability. Furthermore, Schilbach et al. (2021) illustrated that moderate challenge stressors related to lower levels and greater stability of psychological distress during an acute laboratory stress event. Therefore, we hypothesize:

-

H1: Past challenge stressors are associated with lower affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity in (a) positive and (b) negative affect.

Furthermore, given their tendency to be detrimental and harmful to personal resources (Cavanaugh et al., 2000; Crane & Searle, 2016; Webster et al., 2010), we argued that hindrance stressors likely act as sensitizing stressors, resulting in net resource losses. For example, repeated exposure to hindrance stressors may relate to repeated experiences of failure (Cavanaugh et al., 2000). Failure despite the investment of effort, in turn, is associated with feelings of helplessness (Ursin & Eriksen, 2007), where individuals stop actively coping with stressful situations and lose their efficacy beliefs about overcoming future stress and adversity (e.g., Webster et al., 2010). Given these resource losses, individuals sensitized by hindrance stressors are at greater risk of experiencing additional resource losses in the face of novel adversity such as COVID-19 adversity, and thus are likely to experience greater psychological distress (e.g., Hobfoll, 1989) in the form of affective reactivity (see also Belda et al., 2015, 2016; Stroud, 2020). Accordingly, we hypothesize:

-

H2: Past hindrance stressors are associated with greater affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity in (a) positive and (b) negative affect.

Affective Reactivity and its Relationship to Resilience Outcomes

In this study, we chose emotional and psychosomatic strain during the COVID-19 pandemic as resilience outcomes. We did so for two main reasons. First, Hartmann et al. (2020) state that resilience outcomes can be modeled by examining the absence of problems—such as emotional strain—despite adversity. Second, Fisher et al. (2019) outline the need to consider the time frame in which resilience processes occur. We surveyed working employees over a 6-week period. We did not expect individuals in this sample to develop clinical psychopathology within such a relatively short time frame and therefore used emotional and psychosomatic strain as short- to medium-term indicators of resilience outcomes that may influence the risk of psychopathology over time (e.g., Santa Maria et al., 2017).

COR theory posits that psychological distress, such as affective reactivity to adversity, arises from actual or anticipated resource losses, which can lead to a cycle of further losses (Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll et al., 2018). These loss cycles have a detrimental impact on individuals’ psychological and physical well-being. For instance, when adversity induces a decrease in positive affect (i.e., affective reactivity to adversity in positive affect), individuals may experience impaired attentional functioning, reduced social contacts, and diminished motivation for activities that would otherwise provide positive reinforcements (Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005). The absence of positive reinforcements may lead to a continuous decline in psychological well-being (e.g., De Wild-Hartmann et al., 2013). Similarly, when adversity triggers an increase in negative affect (i.e., affective reactivity to adversity in negative affect), it may initiate resource loss cycles through excessive negative rumination (e.g., Moberly & Watkins, 2008) or deterioration of relationship quality (e.g., Lépine & Briley, 2011). These factors can result in additional resource losses, such as declining levels of self-efficacy, optimism (e.g., Lyubomirsky et al., 1999), or social support (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008), further inhibiting psychological well-being (see also Charles et al., 2013; Houben et al., 2015; O’Neill et al., 2004). Accordingly, we hypothesize:

-

H3: Affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity in (a) positive and (b) negative affect is positively related to emotional exhaustion during the COVID-19 pandemic.

With regard to psychosomatic symptoms, researchers outlined that affective reactivity in negative affect is associated with physiological loss cycles, as it triggers physiological stress responses that tax the body over time (McEwen, 2000) and increase the likelihood of health complaints (Charles et al., 2013; Piazza et al., 2013). Meta-analytic evidence supports this assumption showing that greater stress reactivity indicates a greater risk for the development of cardiovascular symptoms (Chida & Steptoe, 2010). Furthermore, several field studies suggest that stress-induced affective reactivity in negative affect positively relates to unhealthy habits (e.g., smoking and alcohol consumption; Schlauch et al., 2013), which may further promote the development of physical symptoms such as recurring back pain, migraines, or stomach problems (e.g., Piazza et al., 2013). In addition, a greater adversity-induced decrease in positive affect may also contribute to increased psychosomatic symptoms over time. Tugade and Fredrickson (2004) demonstrated that individuals who experienced lower positive affect during an acute stress event have prolonged cardiovascular reactivity (see also, Fredrickson & Levenson, 1998). Such prolonged stress reactivity may trigger similar loss processes to those described above and thus likewise contribute to psychosomatic symptoms (e.g., McEwen, 2000). Accordingly, we hypothesize:

-

H4: Affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity in (a) positive and (b) negative affect is positively related to psychosomatic symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, combining hypotheses H1 to H4, we derive the following mediation hypotheses:

-

H5: Past challenge stressors are negatively related to emotional exhaustion during the COVID-19 pandemic via lower affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity in (a) positive and (b) negative affect.

-

H6: Past challenge stressors are negatively related to psychosomatic symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic via lower affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity in (a) positive and (b) negative affect.

-

H7: Past hindrance stressors are positively related to emotional exhaustion during the COVID-19 pandemic via higher affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity in (a) positive and (b) negative affect.

-

H8: Past hindrance stressors are positively related to psychosomatic symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic via higher affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity in (a) positive and (b) negative affect.

Method

Participants and Procedures

In 2018, we invited 182 German organizations to participate in our study. To incentivize participation, we offered organizations parts of a psychological risk assessment, which is a mandatory procedure in Germany. Thirteen organizations agreed to take part. All organizations allowed employees to complete the surveys at work, and some offered additional incentives for participation, such as a drawing of wellness vouchers. To be eligible to participate, employees had to work at least 20 h per week. Participants were recruited through information sessions or intranet postings. A total of 572 employees enrolled in the study and completed the initial survey. Participants then provided information on their work stressors in a weekly diary over the course of 3 weeks and further completed two additional surveys six and 12 months after the last weekly survey. Thus, we obtained information on employees’ stressors on up to five measurement occasions over the course of 13 months between April 2018 and November 2019 (T0)Footnote 1. We chose to use the repeated measures of work stressors over an extended period of time to gain a robust insight into the general working conditions of participants that may be related to inoculation (i.e., resource gains) or sensitization processes (i.e., resource losses), to control for seasonal effects that may be associated with high or low work stressors, and to further reduce the impact of common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Subsequently, in March 2020, we used the first COVID-19-induced lockdown in Germany as an opportunity to examine the resilience process and re-contacted the same participants. Participants were invited to complete a baseline survey, followed by six weekly surveys (T1–T6). In the weekly surveys (T1–T5), participants provided information on COVID-19 adversity and their positive/negative affect. In addition, emotional exhaustion and psychosomatic symptoms were measured at week one (T1) and week six (T6). We used a 6-week weekly study mainly for two reasons: first, given the dynamics of the pandemic and associated the changing (government) regulations, we expected that levels of adversity would vary not only between individuals, but also within individuals. To account for these within-person variations in COVID-19 adversity, and given that regulations changed weekly rather than daily, we decided to administer weekly surveys. Second, our goal was to examine how short-term reactivity (i.e., affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity) accumulates to shape mid- to long-term psychological well-being as an indicator of resilience outcomes. Because stress-induced psychosomatic symptoms take several weeks to develop (e.g., Keller et al., 2020), we chose to administer our survey over the course of 6 weeks.

We incentivized participation in the 6-week weekly study in the following ways: We sent out a summary of key findings including specific suggestions on how to maintain or strengthen individual resilience after the data collection was completed. In addition, we raffled 25 vouchers (20€ each) obtained from a social catering company. Ethical approval was obtained prior to data collection.

The baseline survey of the 2020 weekly study was completed by 199 employees, resulting in a response rate of 34.8%. Individuals who participated in the 2020 weekly study did not differ in age, gender, or education from those who only participated in the 2018/2019 panel study. Given that we were interested in weekly affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity, we excluded 17 individuals who did not respond to at least one of the weekly surveys. Of the resulting 182 participants, 134 individuals completed at least one of the 2018 weekly diary study follow-up surveys (i.e., at six- or 12-month follow-up) and also completed T1 and T6 during the COVID-19-induced lockdown. We based our analyses on these 134 individuals who provided a robust insight into their general work conditions (i.e., by providing information on their work stressors for at least 7 months), and whose participation in T1 and T6 allowed us to test whether mediator variables would predict outcomes at T6 over and above outcomes at T1. In the final sample, the mean age was 46.2 years (SD = 10.84), 70.5% of participants were female and 51.9% of the participants held an (applied) university degree. Additionally, 82.9% were in a relationship and 52.2% reported having at least one child. On average, participants worked for 36.2 h per week (SD = 9.91). Our sample consisted of office/knowledge workers, mainly employed in the (public) service and the financial sectors.

Measures

We measured all study variables in German. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics, intercorrelations, and reliability indices.

Challenge and Hindrance Stressors

We assessed work stressors at T0 (i.e., at up to five measurement occasions between April 2018 and November 2019) using the challenge-hindrance scale developed by Rodell and Judge (2009). Participants indicated their responses on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), referring to either their workweek (for the first three measurement occasions) or the past 6 months (for the last two measurement occasions). The challenge stressor scale consists of eight items assessing time pressure, workload, complexity, and responsibility with two items each. In this study, we focused on responsibility and complexity as challenge stressors. Unlike time pressure and workload, for which the empirical evidence regarding their challenging potential is mixed (e.g., Schilbach, Haun, et al., 2023; Schmitt et al., 2015), these stressors show a clear challenging tendency: Kim and Beehr (2020), for example, showed that responsibility and learning demands (i.e., a construct closely related to complexity) were positively related to challenge and negatively related to hindrance appraisal. Similarly, Schilbach, Arnold, et al., (2023) showed that complexity was appraised as challenging regardless of co-occurring stressors but was appraised as hindering only when co-occurring stressors were high. Thus, we excluded the four items assessing workload and time pressure and tested our hypotheses based on the four items assessing complexity and responsibility (e.g., “My job has required me to use a number of complex or high-level skills,” “or “I’ve felt the weight of the amount of responsibility I have at work”). Hindrance stressors were measured using all eight items developed of the Rodell and Judge (2009) scale, which assesses levels of role conflict, role ambiguity, red tape, and daily hassles. Sample items were “I had to go through a lot of red tape to get my job done” or “I had many hassles to go through to get my projects/assignments done.”

Given that the hypotheses were tested at the between-person level, we conducted a partially saturated multilevel confirmatory factor analysis (MCFA) to obtain between-person model fits (Ryu & West, 2009). In conducting the MCFAs, we also included workload and time pressure items (Rodell & Judge, 2009) to assess the appropriateness of excluding these items from the challenge stressor scale. Consistent with our assumptions, a three-factor model with complexity and responsibility items comprising one factor, time pressure and workload items comprising a second factor, and hindrance stressor items comprising a third factor (χ2 (101) = 386.51, p<.001; CFI = .91, TLI = .79, AIC = 24857.53, RMSEA = 0.07) fit the data significantly better than a model in which the time pressure, workload, complexity, and responsibility items were modeled as one factor and the hindrance stressor items were modeled as a second factor (χ2 (103) = 542.07, p<.001; CFI = .86, TLI = .68, AIC = 24959.63, RMSEA = 0.08), or a single-factor model (χ2 (104) = 662.00, p<.001; CFI = .82, TLI = .59, AIC = 25056.14, RMSEA = 0.09).

Affective Reactivity

Following common procedures, we operationalized affective reactivity as individual slopes reflecting between-person differences in within-person affective reactivity to COVID-19-related adversity (e.g., Charles et al., 2013; Lawson et al., 2021). Thus, affective reactivity scores consist of two elements: COVID-19 adversity and positive/negative affect. COVID-19 adversity and affect were measured weekly between T1 and T5. We assessed levels of perceived adversity with a single item (i.e., “During this week, to what extent did you feel that the pandemic situation had a negative impact on you?”; see e.g., Feldman et al., 2004; Schilbach, Arnold, et al., 2023). We measured positive and negative affect using a validated short version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Thompson, 2007; Watson et al., 1988). The PANAS consists of five adjectives indicating positive affect (i.e., determined, attentive, alert, inspired, active) and five adjectives indicating negative affect (i.e., afraid, nervous, upset, hostile, ashamed). For both, adversity and affect, participants provided responses on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Note that in the analytic approach section, we describe in more detail how COVID-19 adversity and positive/negative affect were combined to indicate affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity.

Emotional Exhaustion

We assessed emotional exhaustion at T1 and T6 using the three-item short version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (see e.g., Kinnunen et al., 2014; Kronenwett & Rigotti, 2019; Maslach & Jackson, 1986). A sample item was “I felt emotionally drained.” Participants referred to their experiences in the past week and indicated their responses on a scale from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree).

Psychosomatic Symptoms

Psychosomatic symptoms were assessed at T1 and T6 using a six-item scale (Mohr & Müller, 2014). A sample item was “I experienced headaches or pain in my back, neck or shoulders.” Participants referred to their experiences in the past week and indicated their responses on a scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (very often).

Analytic Approach

In a first step, we generated our independent variable and aggregated the experienced challenge and hindrance stressors from the weekly diary as well as the six- and 12-month follow-up (i.e., T0) in such a way that we obtained a mean level of past work stressors per individual based on up to five measurement occasions spread over 13 months (M = 4.65 measurement occasions).

In a second step, following the procedures of, for example, Lawson et al. (2021), we used the weekly questionnaires completed between T1 and T5 to obtain indicators of affective reactivity. On average, individuals provided information on COVID-19-related adversity and positive/negative affect on 4.69 occasions. Given the hierarchical data structure (i.e., weeks nested within individuals), we tested for the appropriateness of multilevel modeling by examining intraclass correlations (ICC1s). ICC1s of .64 for COVID-19 adversity, .62 for positive affect, and .68 for negative affect supported the adequacy of multilevel analysis. We then group-mean centered COVID-19 adversity (see e.g., Enders & Tofighi, 2007) and estimated a random slope model such that we obtained two slopes per individual indicating an individual’s relationship between weekly COVID-19 adversity and weekly positive and negative affect. The analysis was based on 629 observations nested in 134 individuals. Overall, there was a negative relationship between COVID-19 adversity and positive affect (B = −0.11, SE = 0.04, p = .003) and a positive relationship between COVID-19 adversity and negative affect (B = 0.08, SE = 0.03, p = .004). Thus, on average, employees reported lower levels of positive affect and higher levels of negative affect during weeks in which they experienced more COVID-19 adversity. Individual slopes ranged from −0.46 to 0.04 for positive affect as the dependent variable and from −.07 to .23 for negative affect as the dependent variable. These individual slopes were used as indicators of positive and negative affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity and thus as the mediator variables of our research model (see also Lawson et al., 2021)Footnote 2.

Third, we conducted a path analysis to test the proposed main effects. To provide an indication of effect size, we report standardized coefficients (e.g., Cohen, 1988; Fey et al., 2022) which can be considered of practical significance when they are .20 or higher (Ferguson, 2009). In addition, given the relatively small sample size of 134 individuals, to test mediation hypotheses, we followed the recommendation of Koopman et al. (2015; see also Yuan & MacKinnon, 2009) and computed Bayesian credibility intervals (CIs). This approach does not impose restrictive normality assumptions on the sampling distributions of the estimates. Thus, it does not rely on large sample approximations, making it well suited for studies with smaller samples (Yuan & MacKinnon, 2009). In addition, Koopman et al. (2015) show that in smaller samples, the Bayesian approach is associated with a lower risk of type I error compared to bootstrapping, thus increasing the precision of results. We tested our hypotheses in an overall model using Mplus, version 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017)Footnote 3.

Results

In Table 2, we present the results of testing H1 to H4. There was a positive relationship between challenge stressors and affective reactivity (i.e., the average within-person relationship between COVID-19 adversity and affect) in positive affect (β = .32, SE = .10, p = .001). Given that the values of affective reactivity in positive affect ranged from −0.46 to 0.04, the results suggest that challenge stressors were associated with a value closer to zero, and thus with a less steep negative relationship between COVID-19 adversity and positive affect, indicating lower affective reactivity in positive affect. In contrast, challenge stressors were not related to affective reactivity in negative affect (β = −.02, SE = .10, p = .874). Thus, we accept H1a and reject H1b. Results further indicated that hindrance stressors were negatively related to affective reactivity in positive affect (β = −.25, SE = .10, p = .011). Thus, higher hindrance stressors were associated with a stronger negative relationship between COVID-19 adversity and positive affect, indicating greater affective reactivity in positive affect. In addition, hindrance stressors were positively related to affective reactivity in negative affect (β = .30, SE = 0.10, p = .003). Given that the values of affective reactivity in negative affect ranged from −.07 to .23, hindrance stressors were associated with a stronger positive relationship between COVID-19 adversity and negative affect, indicating greater affective reactivity in negative affect. Therefore, we accept H2a and H2b.

Controlling for emotional exhaustion at T1, we found a negative relationship between the affective reactivity in positive affect and emotional exhaustion at T6 (β = −.20, SE = .07, p = .002). Thus, the lower the affective reactivity in positive affect (i.e., a value closer to zero), the less emotional exhaustion was reported, whereas a higher affective reactivity in positive affect (i.e., a more negative value) was associated with greater emotional exhaustion. Accordingly, the results support H3a. There was no relationship between affective reactivity in negative affect and emotional exhaustion at T6 (β = −.04, SE = .07, p = .597). Accordingly, we reject H3b.

Controlling for psychosomatic symptoms at T1, we found a negative relationship between affective reactivity in positive affect and psychosomatic symptoms at T6 (β = −.30, SE = .07, p < .001). Thus, lower affective reactivity in positive affect was associated with fewer psychosomatic symptoms whereas a higher affective reactivity in positive affect was associated with more psychosomatic symptoms. This result supports H4a. In addition, consistent with H4b, we found a positive relationship between affective reactivity in negative affect and psychosomatic symptoms at T6 (β = .20, SE = .07, p = .008). Thus, greater affective reactivity in negative affect was associated with higher levels of psychosomatic symptoms. Note that all significant effects were of practical relevance (Ferguson, 2009) and of small to medium size (Ferguson, 2009; Fey et al., 2022).

In Table 3, we illustrate the results of testing H5 through H8. In support of H5a, there was a negative indirect effect of challenge stressors on emotional exhaustion via affective reactivity in positive affect (γ = −.06, 95% CI [−.13, −.01]). Challenge stressors were not related to emotional exhaustion via affective reactivity in negative affect (γ = .00, 95% CI [−.02, .02]). Therefore, we reject H5b. Similarly, we found a negative indirect relationship between challenge stressors and psychosomatic symptoms through affective reactivity in positive affect (γ = −.09, 95% CI [−.17, −.03]), but affective reactivity in negative affect did not mediate the relationship between challenge stressors and psychosomatic symptoms (γ = .00, 95% CI [−.04, .06]). Thus, we accept H6a and reject H6b. Additionally, hindrance stressors were positively related to emotional exhaustion through affective reactivity in positive affect (γ = .05, 95% CI [.01, .13]). Thus, we accept H7a. Affective reactivity in negative affect did not mediate the relationship between hindrance stressors and emotional exhaustion (γ = −.01, 95% CI [−.06, .02]). Accordingly, we reject H7b. Finally, hindrance stressors were positively related to psychosomatic symptoms through affective reactivity in positive (γ = .07, 95% CI [.02, .14]) and negative affect (γ = .05, 95% CI [.002, .10]). Therefore, we accept H8a and H8b.

Additional Analyses

We report detailed results of all additional analyses in the Supplemental Material. Below, we summarize the main findings. Given that participants worked throughout the lockdown, it seems possible that the experience of work stressors between T1 and T5 may contribute, at least in part, to the experience of COVID-19-related adversity. In this case, adaptation to adversity would indicate not only inoculation and sensitization across contexts, but potentially a mixture of inoculation/sensitization to the same stressors (i.e., challenge and hindrance stressors) and nonwork adversity (i.e., COVID-19 specific stressors). Accordingly, we controlled for weekly challenge and hindrance stressors between T1 and T5 when extracting individual slopes indicating affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity. Patterns of results persisted, supporting the presence of inoculation and sensitization across contexts.

In addition, we controlled for mean levels of COVID-19 adversity as well as the random intercepts of negative and positive affect based on data collected between T1 and T5. This allowed us to test whether affective reactivity contributes to positive adaptation beyond the levels of adversity as well as general, more stable levels of positive and negative affect (see also Lawson et al., 2021). Result patterns persisted with one exception: The negative relationship between affective reactivity in positive affect and emotional exhaustion now became of marginal significance (β = −.12, SE = .06, p = .063). Yet, overall results suggest that affective reactivity contributes to health-related outcomes beyond the level of adversity and the more stable levels of positive and negative affect, particularly regarding psychosomatic symptoms.

Discussion

Our study showed that challenge stressors experienced prior to the COVID-19 pandemic were associated with lower levels of emotional and psychosomatic strain at the onset of the pandemic through lower affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity. In contrast, past hindrance stressors were associated with greater emotional and psychosomatic strain through greater affective reactivity. Taken together our findings suggest that exposure to work stressors may induce inoculation and sensitization processes, that is, they may influence adaptation to future adversity that originates outside the workplace. This highlights the importance of work design in facilitating employee resilience across contexts and domains.

Theoretical Implications

Our study holds implications for the stressor-resilience relationship, the concepts of stress inoculation and sensitization, and the challenge-hindrance framework. First, we enriched previous research on the stressor-resilience relationship (e.g., Crane & Searle, 2016; Jannesari & Sullivan, 2021) by identifying affective reactivity to adversity as a mechanism to explain why challenge and hindrance stressors differentially relate to resilience outcomes. Note, however, that challenge stressors were only related to resilience outcomes through lower affective reactivity to adversity in positive affect but did not show a significant relationship with affective reactivity to adversity in negative affect. A possible explanation for this finding may be that challenge stressors tend to be positively related to positive affect (e.g., Mazzola & Disselhorst, 2019; Tadić et al., 2015) and unrelated to negative affect (e.g., Kronenwett & Rigotti, 2022; Turgut et al., 2017). Combining these empirical findings with Lazarus’ (1991) assertion that past stress response patterns shape future patterns, it seems plausible that challenge stressors shape affective reactivity to adversity, particularly with regard to positive affect. In contrast, hindrance stressors tend to be positively related to negative and negatively related to positive affect (e.g., Tadić et al., 2015; Turgut et al., 2017). These affective response patterns in positive and negative affect may, in turn, spill over to future stressful events. This is supported by our findings, which show that past hindrance stressors were associated with both affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity in positive and negative affect.

Overall, however, our findings support the assumptions of COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989) and the challenge-hindrance framework (Cavanaugh et al., 2000), suggesting that challenge stressors are associated with stress inoculation and thus, net resource gains whereas hindrance stressors are likely to result in stress sensitization and thus, net resource losses (see also Cavanaugh et al., 1998). Such inoculation or sensitization prevents or exacerbates the experience of psychological distress to future adversity, as indicated by affective reactivity, and thus facilitates or inhibits well-being in adverse times. These findings are also consistent with the work of Fredrickson and Tugade, who demonstrated that negative and especially positive affect are critical predictors of positive adaptation to adversity (e.g., Fredrickson et al., 2003; Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004).

Second, inherent in COR theory and the concepts of stress inoculation and sensitization is the assumption that past experiences shape adaptation to future adversity across different contexts. To date, the concepts of stress inoculation and sensitization have been applied primarily in the fields of animal research and developmental as well as clinical psychology, where scholars typically rely on laboratory or training settings (e.g., Ayash et al., 2020; Saunders et al., 1996). By enriching the concepts of inoculation and sensitization with the propositions of COR theory, applying them to a naturalistic work setting, and demonstrating that past work stressors are related to affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity, we support the validity of the concepts and their value in advancing our understanding of the growth-enhancing or growth-inhibiting potential of work stressors. Moreover, consistent with theoretical assumptions, our findings suggest that work stressors present an opportunity for inoculation as well as a risk for sensitization across contexts. This cross-context effect may be unique to work stressors, as Leger et al. (2022) found no support for the notion that work-related resources shape affective reactivity to home-based stressors. Consequently, work-related challenge and hindrance stressors may be particularly important in shaping employees’ resilience across domains.

Third, by choosing to operationalize resilience as a process consisting of affective reactivity as a resilience mechanism and emotional and psychosomatic strain as resilience outcomes, we followed the recommendations of Hartmann et al. (2020) as well as Fisher and Law (2021) and observed the resilience process in situ. This adds to previous studies (e.g., Crane & Searle, 2016; Kunzelmann & Rigotti, 2021) that focused on the link between work stressors and resilience capacity, that is, a subjectively perceived and hypothetical form of resilience. With this study, we enrich previous findings and show that challenge and hindrance stressors experienced in the past are associated with lower and higher emotional and psychosomatic strain, respectively, through differential affective reactivity patterns to current adversity. As such, work stressors may not only influence employees’ resilience capacity (e.g., Crane & Searle, 2016), but may further impact upon the demonstration of actual adaptive processes.

The identification of affective reactivity to adversity as a link between work stressors and strain outcomes further goes beyond the context of resilience research. While theoretical models such as the Effort Reward Imbalance Model (Siegrist, 1996), the Job Demands-Resources model (Demerouti et al., 2001), or the challenge-hindrance framework (Cavanaugh et al., 2000) postulate a positive stressor-strain relationship, in longitudinal studies where authors controlled for autoregressive effects, result patterns are heterogeneous, yielding positive, nonsignificant, or even negative associations (see Guthier et al., 2020). Our findings suggest that challenge stressors are associated with more favorable affective response patterns to future stressors, that is, affective stability. Greater affective stability, in turn, is associated with less regulatory effort, and thus, individuals are likely to be less strained. In contrast, hindrance stressors appear to elicit unfavorable affective response patterns by initiating additional resource losses, and thus confrontation with future stressful events is associated with greater regulatory efforts that increase employees’ strain. Consequently, it seems possible that challenge and hindrance stressors do not only exhibit different relationship patterns with performance- and growth-related outcomes as postulated by the challenge-hindrance framework (Cavanaugh et al., 2000), but also, and in the long term, with strain-related outcomes. Future research may aim to replicate these findings in a different context (e.g., stress response patterns to daily stressors). In addition, it is important to understand the boundary conditions which may impact upon the indirect stressor-strain relationship (e.g., sufficient recovery experiences in between stressor exposures, Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Moreover, it seems possible that individuals exhibit affective stability because they suppress their negative emotions. Over time, emotion suppression is likely to become detrimental to mental health (e.g., Nezlek & Kuppens, 2008). Thus, the tendency to suppress emotions may be another important boundary condition for challenge stressors to exert desirable effects on strain-related outcomes through affective stability over time.

Limitation and Suggestions for Future Research

Our study has several limitations that suggest directions for future research. First, our sample consisted of office and knowledge workers which prevents us from generalizing our findings to other occupations. This is particularly the case given previous studies that depicted different effects of stressors depending on occupational backgrounds (Bakker & Sanz-Vergel, 2013). Future research could therefore test the replicability of our findings across different occupations (e.g., healthcare).

Second, we must refrain from making causal inferences. For example, we cannot rule out the possibility that individuals who experience lower affective reactivity when faced with adversity also find themselves in more challenging jobs where they are entrusted with complex tasks and responsibilities. Similarly, individuals who already feel strained may be more vulnerable to adversity and thus experience greater affective reactivity. Accordingly, future research should aim to approximate causality by, for example, conducting mixed-methods studies in which individuals are repeatedly exposed to a laboratory stressor and, in parallel, provide information on their work characteristics so that reversed causality effects can be estimated.

Third, we proposed, based on COR theory and the challenge-hindrance framework, that exposure to challenge stressors is likely to result in net resource gains, while exposure to hindrance stressors may lead to net resource losses. Although we provided a detailed explanation for why these relationships are expected, we did not directly examine the actual changes in resource levels. Therefore, for future research, it would be beneficial to investigate the specific resources that change following exposure to work stressors. In particular, self-efficacy and perceived controllability have been highlighted as crucial factors in developing resilience (e.g., Crofton et al., 2015; Stroud et al., 2011), and they are also known to be related to challenge and hindrance stressors (e.g., Olafsen & Frølund, 2018; Webster et al., 2010). Thus, these resources could serve as promising target variables to study the mechanisms underlying stress inoculation and sensitization.

Beyond the recommendations derived from our study’s limitations, we would like to discuss five additional areas for future research that we feel are particularly important. First, although we chose to focus on stressors that appear to have a clear tendency to be appraised as rather challenging or hindering, we did not measure inter- or intraindividual differences in appraisal patterns of work stressors (see e.g., Schilbach, Arnold, et al., 2023; Webster et al., 2011). Future research could examine whether supposedly challenging (e.g., complexity) or hindering (e.g., role conflict) stressors exert inoculating or sensitizing effects only when individuals also appraise these stressors as challenging or hindering, respectively. Moreover, future research could target the interplay between stressor types, given that stressors are likely to co-occur (e.g., Schilbach, Haun, et al., 2023) and the presence of one stressor may alter the effects and thus, the inoculating or sensitizing potential of another (e.g., Kronenwett & Rigotti, 2019; Schmitt et al., 2015).

Second, although we focused on psychological indicators, it is equally important to examine physiological indicators of inoculation (i.e., allostasis) and sensitization (i.e., allostatic load, e.g., McEwen, 2000) in future research because (a) they have extensive implications for individuals’ resilience, health, and longevity (e.g., Beckie, 2012) and (b) studies report heterogeneous relationship patterns between work stressors and the development of allostasis and allostatic load (e.g., Chida & Hamer, 2008; Schilbach et al., 2021; Wirtz et al., 2013). Understanding whether and how challenging and hindering stressors affect physiological systems is essential for a more holistic understanding of the long-term effects of stressors on resilience processes.

Third, it is important to keep in mind that affective reactivity to adversity represents only one possible resilience mechanism. Hence, to obtain a comprehensive understanding of how work stressors shape resilience mechanisms and, consequently, resilience outcomes, it is essential that future research incorporates additional constructs that reflect reactivity and coping, such as cognitive appraisals and seeking instrumental and emotional support in the face of adversity (Fisher et al., 2019).

Finally, little is known about the temporal unfolding of the inoculation and sensitization process. For example, how long does it take for the personal resources gained through stress inoculation to manifest themselves and (when) do these effects begin to wane? Given recent methodological developments including continuous-time modeling (e.g., Guthier et al., 2020; Voelkle et al., 2012), researchers may address such research questions in the future.

Practical Implication

Our findings illustrate that work stressors represent both an opportunity and a risk for the resilience process of office/knowledge workers. Consequently, we would like to draw employers’ attention to the possibility of designing work in a way that it facilitates resilience and prevents the development of vulnerabilities. This seems particularly important given that meta-analytic evidence shows that the effects of resilience trainings in traditional training settings are small and continue to decline over time (Vanhove et al., 2016). Accordingly, formal resilience training programs that typically target mindfulness, emotion regulation, or impulse control (e.g., Joyce et al., 2018; Robertson et al., 2015) should be complemented by interventions that take place in the naturalistic work setting (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2013; Vanhove et al., 2016).

This study provides specific guidance for resilience-enhancing job design for office/knowledge workers. Specifically, the results suggest that to inhibit affective reactivity to future adversity, employees should be given the opportunity to take on challenge stressors in the form of responsibility and complexity. At the same time, employers should aim to reduce hindrance stressors. Toward these goals, leaders could encourage subordinates to take on challenge stressors, specifically responsibilities and complex tasks. However, to ensure the occurrence of net resource gains, it is crucial that challenge stressors do not become overwhelming and that they remain within employees’ ability to manage successfully. To create such conditions, it is imperative for leaders to have a profound understanding of their subordinates’ abilities and needs and to provide adequate resources. Consequently, leaders could undergo training in follower-centric leadership styles, such as transformational (e.g., Sommer et al., 2016) or health-oriented leadership (Arnold & Rigotti, 2021; Stein et al., 2021). Additionally, employers can strive to optimize work processes to minimize hindrance stressors. Furthermore, granting employees sufficient control over the structuring of work processes can facilitate mastery of challenge stressors (e.g., Kühnel et al., 2012) and contribute to a further reduction of hindrance stressors (Dust & Tims, 2020).

Conclusion

With this study, we showed that challenge stressors experienced in the past were associated to lower emotional and psychosomatic strain at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic through lower affective reactivity to COVID-19 adversity in positive affect. In contrast, hindrance stressors were related to greater COVID-19 adversity-induced affective reactivity in positive and negative affect which increased levels of strain at the pandemic onset. These findings suggest that the experience of past work stressors may cut across domains and influence affective reactivity to current adversity that originates outside the work context, which in turn predicts psychological well-being in the face of adversity. We hope that our study will be followed by research that assesses the causality of the relationship patterns, identifies explanatory mechanisms that link past work stressors to affective reactivity to current adversity, and aims to advance the understanding of the boundary conditions that facilitate stressor-induced resilience and prevent stressor-induced vulnerability across contexts and domains.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to data privacy regulations. Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Note that this data collection was part of a larger project. A data transparency table is included in the online supplement on page 8.

For further information about individuals slopes as indicators of affective reactivity, see page 2 of the supplemental material.

Note that we uploaded our syntax and all measures to the online repository OSF which can be accessed via the following link: https://osf.io/4tfpg/?view_only=105884908324410a9d0c4d19663188fe

References

Arnold, M., & Rigotti, T. (2021). Is it getting better or worse? Health-oriented leadership and psychological capital as resources for sustained health in newcomers. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 70(2), 709–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12248

Ayash, S., Schmitt, U., Lyons, D. M., & Müller, M. B. (2020). Stress inoculation in mice induces global resilience. Translational Psychiatry, 10(1), 200. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-00889-0

Bakker, A. B., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2013). Weekly work engagement and flourishing: The role of hindrance and challenge job demands. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 397–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.06.008

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

Beckie, T. M. (2012). A systematic review of allostatic load, health, and health disparities. Biological Research for Nursing, 14(4), 311–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1099800412455688

Belda, X., Fuentes, S., Daviu, N., Nadal, R., & Armario, A. (2015). Stress-induced sensitization: The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and beyond. Stress, 18(3), 269–279. https://doi.org/10.3109/10253890.2015.1067678

Belda, X., Nadal, R., & Armario, A. (2016). Critical features of acute stress-induced cross-sensitization identified through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis output. Scientific Reports, 6, 31244. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31244

Bonanno, G. A. (2005). Resilience in the face of potential trauma. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(3), 135–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00347.x

Bonanno, G. A. (2012). Uses and abuses of the resilience construct: Loss, trauma, and health-related adversities. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 74(5), 753–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.022

Britt, T. W., Shen, W., Sinclair, R. R., Grossman, M. R., & Klieger, D. M. (2016). How much do we really know about employee resilience? Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 9(2), 378–404. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2015.107

Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., & Boudreau, J. W. (1998). “Challenge” and “hindrance” related stress among U.S. managers. Center of Advanced Human Resource Studies https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cahrswp/126/

Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among U.S. Managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.65

Charles, S. T., Piazza, J. R., Mogle, J., Sliwinski, M. J., & Almeida, D. M. (2013). The wear and tear of daily stressors on mental health. Psychological Science, 24(5), 733–741. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612462222

Chida, Y., & Hamer, M. (2008). Chronic psychosocial factors and acute physiological responses to laboratory-induced stress in healthy populations: A quantitative review of 30 years of investigations. Psychological Bulletin, 134(6), 829–885. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013342

Chida, Y., & Steptoe, A. (2010). Greater cardiovascular responses to laboratory mental stress are associated with poor subsequent cardiovascular risk status: A meta-analysis of prospective evidence. Hypertension, 55(4), 1026–1032. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.146621

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Erlbaum.

Cohen, L. H., Gunthert, K. C., Butler, A. C., O’Neill, S. C., & Tolpin, L. H. (2005). Daily affective reactivity as a prospective predictor of depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality, 73(6), 1687–1713. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00363.x

Crane, M. F., & Searle, B. J. (2016). Building resilience through exposure to stressors: The effects of challenges versus hindrances. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21(4), 468–479. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040064

Crofton, E. J., Zhang, Y., & Green, T. A. (2015). Inoculation stress hypothesis of environmental enrichment. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 49, 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.11.017

de Wild-Hartmann, J. A., Wichers, M., van Bemmel, A. L., Derom, C., Thiery, E., Jacobs, N., van Os, J., & Simons, C. J. P. (2013). Day-to-day associations between subjective sleep and affect in regard to future depression in a female population-based sample. British Journal of Psychiatry, 202, 407–412. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.123794

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

DiCorcia, J. A., & Tronick, E. (2011). Quotidian resilience: Exploring mechanisms that drive resilience from a perspective of everyday stress and coping. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(7), 1593–1602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.04.008

Dienstbier, R. A. (1989). Arousal and physiological toughness: Implications for mental and physical health. Psychological Review, 96(1), 84–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.96.1.84

Dienstbier, R. A., & PytlikZillig, L. M. (2016). Building emotional stability and mental capacity. In C. R. Snyder, S. J. Lopez, L. M. Edwards, S. C. Marques, R. A. Dienstbier, & L. M. PytlikZillig (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of positive psychology (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199396511.013.43

Dust, S. B., & Tims, M. (2020). Job crafting via decreasing hindrance demands: The motivating role of interdependence misfit and the facilitating role of autonomy. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 69(3), 881–912. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12212

Enders, C. K., & Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12(2), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121

Estrada, A. X., Severt, J. B., & Jiménez-Rodríguez, M. (2016). Elaborating on the conceptual underpinnings of resilience. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 9(2), 497–502. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2016.46

Farb, N. A. S., Irving, J. A., Anderson, A. K., & Segal, Z. V. (2015). A two-factor model of relapse/recurrence vulnerability in unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(1), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000031

Feldman, P. J., Cohen, S., Hamrick, N., & Lepore, S. J. (2004). Psychological stress, appraisal, emotion and cardiovascular response in a public speaking task. Psychology & Health, 19(3), 353–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/0887044042000193497

Ferguson, C. J. (2009). An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(5), 532–538. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015808

Fey, C. F., Hu, T., & Delios, A. (2022). The measurement and communication of effect sizes in management research. Management and Organization Review, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1017/mor.2022.2

Fisher, D. M., & Law, R. D. (2021). How to choose a measure of resilience: An organizing framework for resilience measures. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 70(2), 643–673. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12243

Fisher, D. M., Ragsdale, J. M., & Fisher, E. C. (2019). The importance of definitional and temporal issues in the study of resilience. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 68(4), 583–620. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12162

Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2013). Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts and theory. European Psychologist, 18(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2000). Positive affect and the other side of coping. American Psychologist, 55(6), 647–654. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.55.6.647

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Fredrickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition & Emotion, 19(3), 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930441000238

Fredrickson, B. L., & Levenson, R. W. (1998). Positive emotions speed recovery from the cardiovascular sequelae of negative emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 12(2), 191–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999398379718

Fredrickson, B. L., Tugade, M. M., Waugh, C. E., & Larkin, G. R. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.365

Freedy, J. R., & Hobfoll, S. E. (1994). Stress inoculation for reduction of burnout: A conservation of resources approach. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal, 6(4), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615809408248805

Friedmann, J. S., Lumley, M. N., & Lerman, B. (2016). Cognitive schemas as longitudinal predictors of self-reported adolescent depressive symptoms and resilience. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 45(1), 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2015.1100212

Green, J. G., McLaughlin, K. A., Berglund, P. A., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: Associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(2), 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186

Guthier, C., Dormann, C., & Voelkle, M. C. (2020). Reciprocal effects between job stressors and burnout: A continuous time meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 146(12), 1146–1173. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000304

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J.-P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130

Hartmann, S., Weiss, M., Newman, A., & Hoegl, M. (2020). Resilience in the workplace: A multilevel review and synthesis. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 69(3), 913–959. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12191

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513