Abstract

To foster and sustain an ethical culture, organizations need to attract and retain people with high ethical standards. However, there is a lack of knowledge about which organizational characteristics influence the pre- and post-entry work attitudes and behaviors of people with high ethical standards. To fill this gap, we drew on person–organization fit (PO fit) theories and developed the Hazardous Organization Tool (HOT) based on a broad personality trait that is strongly related to ethical standards and predictive of unethical workplace behavior—honesty-humility from the HEXACO personality model. The HOT consists of 9 items that describe organizations that are rated as more attractive by people with low ethical standards. The HOT can be used to measure the extent to which people are attracted to hazardous organizations (HOT-A) and the extent to which people perceive an organization to be hazardous (HOT-P) with different instructions but identical scale options, ensuring commensurability for testing complex fit effects. We examined the validity of the HOT in four samples (total N = 1260). We found moderate to strong correlations between attractiveness ratings of the items (HOT-A) and honesty-humility (ranging from − .31 to − .56) and dark personality traits (ranging from .37 to .63). In addition, hazardous organization perceptions (HOT-P) were related to negative work attitudes and motivation, particularly for employees who were not attracted to hazardous organizations (those with high ethical standards). Overall, the current study suggests that the Hazardous Organization Tool is a valid measure. Implications for the PO fit literature and management practice are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Organizational culture, a social control system that can impose normative influence on the behaviors of managers and employees (Chatman & O’Reilly, 2016), has been consensually deemed as important for the survival and success of organizations (e.g., Chatman et al., 2014; Graham et al., 2022; Guiso et al., 2015). Especially in recent years, organizations have shown great interest in creating an ethical culture. There are several potential reasons for this. First, fostering an ethical culture is often deemed an important social responsibility by itself that organizations want to commit to (Carroll et al., 2016). Second, an ethical culture provides economic added value to organizations (Graham et al., 2022; Guiso et al., 2015). For example, Guiso and colleagues (2015) found that ethical culture was positively correlated with organizational performance. Third, ethical culture can suppress unethical workplace behaviors that are harmful to employers (Kish-Gephart et al., 2010). Fourth, commitment to an ethical culture can be used as a marketing strategy. In doing so, organizations may want to increase public, investor, and employee trust (Kochan, 2003). Moreover, an ethical culture may attract employees with high ethical standards (Guiso et al., 2015) who are less likely to engage in unethical workplace behaviors even without contextual constraints (e.g., De Vries et al., 2017; Kish-Gephart et al., 2010). Although many organizations advertise their commitment to an ethical culture, most of them are not successful at fostering one (Guiso et al., 2015). What is worse, there is a negative relation between the ethical culture as advertised by organizations and the ethical culture as reported by their CEOs (Graham et al., 2022). Such ethical contradictions may be detrimental to employee well-being and may increase turnover—especially among those with high ethical standards—which in turn may lead to an increasingly unethical culture.

Some scholars have proposed the appointment of an ethical CEO as a potential solution (e.g., Ogunfowora, 2014). Others argue that this is a necessary but not sufficient step (e.g., Neville & Schneider, 2021a, 2021b). They argue that employees are not only influenced by the organizational culture but that they also consciously or unconsciously set boundaries for and shape the culture through their daily behaviors (Schneider, 1987; Schneider et al., 1995; Neville & Schneider, 2021a, 2021b; see also Graham et al., 2022; but see Chatman, 2021). This suggests that organizations that want to become more ethical should attract, recruit, and retain people who support high ethical standards so that these people can help the organization to progressively foster and strengthen an ethical culture (De Vries, 2018; Neville & Schneider, 2021a, 2021b). A crucial prerequisite to do so is developing a comprehensive understanding of which organizational characteristics are perceived as aversive to these people.

In this study, we aim to answer this question by, first of all, delineating important characteristics that make an organization more (less) attractive to people with low (high) ethical standards, as attraction is the first stage of person–organization interaction process (De Vries et al., 2016a, 2016b; Schneider, 1987; Schneider et al., 1995). For this purpose, we drew on personality and person–organization fit (PO fit) theories and chose the HEXACO honesty-humility factor (Ashton et al., 2004) as the starting point for our research program given its strong positive relation with ethical standards (De Vries & Van Kampen, 2010). We reviewed the evidence related to honesty-humility to infer which organizational characteristics should influence the pre- and post-entry work attitudes and behaviors of people high in honesty-humility. Based on the literature review, we identified five organizational characteristics that make organizations (un)attractive to people with low (high) ethical standards: in such organizations managers and/or employees (a) are more tolerant of sexual misconduct, (b) support power inequality, (c) are strongly motivated by monetary incentives, (d) disregard ethical standards, and (e) hide knowledge. We call these organizations hazardous organizations, as they may represent an exciting environment for some people (i.e., people with low ethical standards) but may also be conducive to behaviors that other people (i.e., people with high ethical standards) perceive as risky, ethically dubious, and even repulsive.Footnote 1 Second, we developed and validated a 9-item “Hazardous Organization Tool” (HOT) that describes hazardous organizations, and that can be used to measure both the attractiveness of these organizations to people (Hazardous Organization Tool-Attractiveness, HOT-A) and to measure people’s perception of organizations (Hazardous Organization Tool-Perception, HOT-P).Footnote 2 Third, we show that hazardous organizations are more likely to attract and retain people with low ethical standards (i.e., low in HEXACO honesty-humility and high in dark personality traits).

By introducing the HOT, the current study makes two primary contributions. First, previous research suggests that an organization’s ethical culture may not be the only organizational characteristic that influences the pre- and post-entry work attitudes of people with high ethical standards towards the organization (e.g., Lukacik & Bourdage, 2020), but a comprehensive understanding of these “other” organizational characteristics is still lacking. This study is the first to uncover a broader range of relevant organizational characteristics. We show that these organizational characteristics affect both the pre-entry (i.e., organizational attractiveness) and post-entry work attitudes (e.g., job satisfaction) of people with high ethical standards (i.e., high in HEXACO honesty-humility and low in dark personality traits). Moreover, when used to measure organizational attractiveness/culture preference, it showed stronger correlations with personality traits indicative of ethical standards than a widely used measure of ethical culture (i.e., the updated Organizational Culture Profile, OCP; Chatman et al., 2014), demonstrating better convergent validity. Thus, the HOT is a more comprehensive and effective tool that can help organizations know if they are at risk of being unattractive to and have a negative impact on employees with high ethical standards.

Second, most existing measures were developed and validated to measure either the person or the organization (e.g., the Corporate Ethical Virtues Questionnaire; Kaptein, 2008) and cannot be easily adapted to measure the other variable in a commensurable manner. In contrast, the HOT employs identical items (nominal equivalence) and scale options (scale equivalence) when measuring both the person and the organization, thus ensuring commensurability (Edwards & Shipp, 2007). This feature makes the HOT suitable for testing complex hypotheses regarding fit or congruence effects (e.g., the asymmetric congruence hypothesis; Humberg et al., 2020). In addition, our choice of the broad personality trait of HEXACO honesty-humility for scale development also answers a call in the PO fit literature for more research that considers the content of the person and organization, which allows for a deeper understanding of the PO fit effects (Chapman et al., 2005; Edwards & Shipp, 2007; see also Barrick & Parks-Leduc, 2019). Taken together, the personality-centered approach we demonstrate in the current study provides an avenue for future research to further explore and compare PO fit effects from the perspective of different broad and narrow personality traits (e.g., honesty-humility and its facet fairness; Ashton et al., 2004) on work attitudes and behaviors, which will ultimately advance theories of person–organization fit in particular and person–environment fit in general.

In the next sections, we first explain the theoretical basis for constructing the HOT. Second, we summarize six characteristics of hazardous organizations. Third, we explain our strategy for validating the HOT. Fourth and finally, at the end of the introduction, we provide an overview of the research program in which we developed and validated the HOT.

Theoretical Background

To identify the characteristics of hazardous organizations, we drew on two theories from the personality and PO fit literature. In their attraction-selection-attrition (ASA) model, Schneider et al., (1995, p.749) proposed that “people find organizations differentially attractive as a function of their implicit judgments of the congruence between those organizations’ goals (and structures, processes, and culture as manifestations of those goals) and their own personalities.” Similarly, the situation activation mechanism from the situation, trait, and outcome activation (STOA) model suggests that people are attracted to situations that match their personality traits (De Vries et al., 2016a, 2016b). Both theories propose that attraction to organizations is determined by the degree of match between the person’s personality traits and organizational characteristics, namely PO fit (Barrick & Parks-Leduc, 2019).

PO fit can also affect who tends to stay in an organization. The ASA model posits that people who fit an organization tend to stay in it (Schneider, 1987; Schneider et al., 1995). The outcome activation mechanism from the STOA model posits that people are more likely to receive desirable outcomes when they act in situations that match their personality traits (De Vries et al., 2016a, 2016b). Therefore, it is expected that employees who fit an organization are more likely to have positive experiences that make them want to continue working for the organization.

In summary, both the ASA and STOA model claim that people are more likely to be attracted to and stay in organizations that possess characteristics that match their personality traits. Evidence supporting this claim has accumulated over the past few decades (see Barrick & Parks-Leduc, 2019; Van Vianen, 2018, for more comprehensive reviews). Chapman and colleagues (2005) found that PO fit is an important correlate of recruitment outcomes including organizational attractiveness, job pursuit intentions, acceptance intentions, and job choice. Similarly, Uggerslev and colleagues (2012) found that PO fit is the strongest predictor of applicant attraction beyond many other documented predictors (e.g., job characteristics, recruiter behaviors) across different stages of recruitment (Uggerslev et al., 2012). PO fit is also associated with desirable post-entry work attitudes and lower turnover rates (Arthur et al., 2006; Kristof‐Brown et al., 2005; Verquer et al., 2003).

Honesty-Humility and Organizational Attractiveness

People low versus high in honesty-humility can be characterized by traits related to deceitfulness, slyness, greediness, and pretentiousness versus sincerity, fairness, greed avoidance, and modesty (Ashton et al., 2004). Previous research has shown that people low rather than high in honesty-humility have slightly worse in- and out-role job performance (Lee et al., 2019; Pletzer et al., 2021) and are more likely to engage in counterproductive workplace behaviors, including misconduct (e.g., knowledge hiding; Ogunfowora et al., 2022), deviance (e.g., absenteeism; De Vries & Van Gelder, 2015; Lee et al., 2019; Pletzer et al., 2019), and unethical business decisions (De Vries et al., 2017). This suggests that people low in honesty-humility are more likely to pursue personal interests at the expense of others when the situation permits (De Vries et al., 2016a, 2016b), presumably due to their indifference to ethics and their ability to morally disengage from their wrongdoing (De Vries & Van Kampen, 2010; Ogunfowora et al., 2022). Importantly, honesty-humility is strongly associated with morality (0.66; De Vries & Van Kampen, 2010). Taken together, this literature suggests that honesty-humility is a sound measure of people’s endorsement of high ethical standards and a strong predictor of their ethical behavior in the workplace.

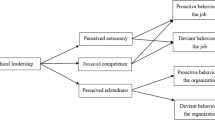

As noted in the previous section, both the ASA and STOA model suggest that people are more likely to be attracted to organizations that possess characteristics matching their personality traits. We therefore define hazardous organizations as those where the reward structure allows people low in honesty-humility (i.e., low in ethical standards) to pursue their interests relatively uninhibitedly, regardless of the interests of other individuals, groups, or organizations, which correspond to low honesty-humility (i.e., low ethical standards). We then conducted a literature review of articles on honesty-humility and summarized characteristics that may constitute hazardous organizations that are more attractive to people low in honesty-humility.

Six Characteristics of Hazardous Organizations

To ensure that we could identify the characteristics of hazardous organizations as comprehensively as possible, we reviewed the literature listed on hexaco.org, a HEXACO personality research repository that lists most articles on the HEXACO personality model that have been published by the end of 2019.Footnote 3 To supplement the list, we manually searched for articles published after 2019. Based on this review, we identified six characteristics that correspond to our definition of hazardous organizations. The six characteristics were differentiated based on content overlap agreed upon by the authors. Three of these characteristics reflect the ease with which people in organizations can obtain Individual Ends that are more attractive to people low rather than high in honesty-humility (i.e., sex, power, and money; De Laat, 2020; Lee et al., 2013; Zettler et al., 2020). The other three characteristics reflect configurations of descriptive organizational norms (i.e., commonly enacted behaviors that create an expectation to conform to the same behavior; e.g., Dannals & Miller, 2017) that provide Organizational Means for people low in honesty-humility to pursue their personal ends. We elaborate on each of these characteristics below (see Table 1 for a summary).

The first characteristic of hazardous organizations is Sex Tolerance. People low in honesty-humility are more likely to engage in uncommitted sexual “quid pro quo” relationships (e.g., Ashton & Lee, 2008; Lee et al., 2013). We therefore speculate that applicants low rather than high in honesty-humility may be more attracted to organizations where “loose” sexual behaviors and misconduct are more often tolerated (e.g., exchanging sexual favors to obtain a promotion is more tolerated).

The second characteristic of hazardous organizations is Power Inequality. People low in honesty-humility may prefer a social system that perpetuates inequality and prioritizes enhancing self-esteem through the pursuit of power and success over protecting the welfare of others (Lee et al., 2010; Leone et al., 2012). Moreover, in Lukacik and Bourdage’s (2020) study, applicants low in honesty-humility were more attracted to organizations with Powerful and Achievement-Oriented organizational images. Therefore, vertical organizations that support power inequality and instigate internal competition are more likely to be attractive to applicants low rather than high in honesty-humility.

The third characteristic of hazardous organizations is Money Orientation. People low in honesty-humility feel entitled to higher levels of wealth and are attracted to making more money, even if it means taking financial or physical risks (Ashton et al., 2010; Julian et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2013). The preference for money may be due to the desire to demonstrate financial success and superiority (e.g., through conspicuous consumption; Ashton & Lee, 2005; Lee et al., 2013). Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that organizations where organizational members are strongly motivated by financial incentives may be more attractive to applicants low rather than high in honesty-humility.

The fourth characteristic of hazardous organizations is Loose Ethical Standards. De Vries and colleagues (2017) found that people low in honesty-humility were more likely to be lured by unethical business proposals when they perceived high corruption in their environment (e.g., their organization fails to stipulate that corruption will be punished). Ogunfowora (2014) found that applicants high in honesty-humility were more likely to apply for jobs in organizations led by a CEO who adhered to high ethical standards while their counterparts were indifferent to the CEO’s ethics. Similarly, Lukacik and Bourdage (2020) found that applicants high in honesty-humility were more attracted to organizations with Benevolent and Universal organizational images (e.g., high relevance of equality, honesty, responsibility; Schwartz, 1992). Taken together, organizations with loose ethical standards provide more affordances for selfish behaviour, and people low in honesty-humility may feel more comfortable to taking advantage of these affordances. Therefore, we speculate that, compared to applicants high in honesty-humility, applicants low in honesty-humility are more likely to be attracted to organizations that demonstrate loose ethical standards.

The fifth characteristic of hazardous organizations is Knowledge Hiding. De Laat (2020) found that people low in honesty-humility were reluctant to share knowledge with colleagues. This is likely because that critical and unique knowledge can endow the owner with power, status, and a large network (Wang & Noe, 2010). Therefore, we speculate that people low rather than high in honesty-humility will be more attracted to organizations where valuable information and knowledge can be exclusively occupied (e.g., knowledge is more accessible to high-level members).

The sixth and final characteristic of hazardous organizations is Entrepreneurial Orientation. Lumpkin and Dess (1996) distinguished five components of entrepreneurial orientation: autonomy, innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, and competitive aggressiveness. Risk-taking refers to an organization’s willingness to invest in risky projects and take bold steps to achieve organizational goals. Competitive aggressiveness refers to an organization’s tendency to take aggressive actions to confront rivals and gain market share (for the definitions of the other components, see Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). Compared to their counterparts, people low in honesty-humility have been found to have a relatively high risk tolerance when pursuing financial interests (Ashton et al., 2010) and are more likely to engage in aggressive behaviors (Zettler et al., 2020). Therefore, we speculate that people low rather than high in honesty-humility may feel more comfortable joining organizations that are willing to engage in aggressive expansion by taking financial risks than organizations that stick to steady—and less financially risky—development (Table 2).

Validity of the HOT

Descriptions of hazardous organizations (Hazardous Organization Tool, HOT) were constructed in accordance with the above six characteristics. As we mentioned above, the HOT can be used to measure the extent to which people are attracted to hazardous organizations (HOT-A) and the extent to which people perceive an organization to be hazardous (HOT-P). The hazardous organizations described by the HOT should negatively influence the pre- and post-entry work attitudes of people with high ethical standards. Therefore, it is preferable to have two separate pieces of validity evidence for the two HOT measures. First, given that hazardous organizations should negatively influence the pre-entry work attitudes of people with high ethical standards, the attractiveness ratings of the HOT (HOT-A; representing the most primary pre-entry work attitude) should be more negatively related to personality traits that indicate high ethical standards (convergent validity) and less strongly related to personality traits that are weakly related or unrelated to ethical standards (divergent validity). Moreover, previous research has found significant relations between personality traits that indicate low ethical standards (though less strongly compared to honesty-humility) and preferences for organizational cultures other than ethical culture. Therefore, the HOT-A should be positively related to preferences for an ethical culture and other somewhat similar organizational cultures (convergent validity) and less strongly related to preferences for dissimilar organizational cultures (divergent validity). Second, given that hazardous organizations should negatively influence the post-entry work attitudes of people with high ethical standards, perceptions of their current employers as hazardous (HOT-P) should be related to employees’ negative (post-entry) work attitudes, especially for those with high ethical standards (low in HOT-A; predictive validity). We followed this logic to assess the (convergent, divergent, and predictive) validity of the HOT measures, which are detailed below (see Table 2 for an overview).

Convergent and Divergent Validity

We first validated the HOT-A by examining whether people low rather than high in honesty-humility score higher on the HOT-A (Hypothesis 1, Table 2). Because of the theoretical and empirical distinction between the HEXACO personality traits (i.e., differential correlations with morality; Ashton & Lee, 2007; De Vries & Van Kampen, 2010), the lack of correlations between the HOT-A and HEXACO personality traits other than honesty-humility will demonstrate divergent validity of the HOT-A (Hypothesis 2, Table 2).

Although we developed the HOT based on honesty-humility evidence, other constructs such as dark personality traits can also measure ethical standards (e.g., Moshagen et al., 2018). The dark triad refers to three socially undesirable personality traits: narcissism, psychopathy, and machiavellianism (Jonason & Webster, 2010). They likewise represent individual differences in social exploitation (Jonason et al., 2009). Similarly, the Dark Factor of Personality (Moshagen et al., 2020) is defined as “the general tendency to maximize one’s individual utility—disregarding, accepting, or malevolently provoking disutility for others—, accompanied by beliefs that serve as justifications” (p. 657). Previous findings support the empirical overlap between these two dark personality conceptualizations and low honesty-humility (Hodson et al., 2018; Moshagen et al., 2018), and their relations with morality (Jonason et al., 2015; Moshagen et al., 2018). Therefore, positive relations between the HOT-A and the Dark Triad (Jonason & Webster, 2010) and Dark Factor of Personality (Moshagen et al., 2020) will demonstrate convergent validity of the HOT-A (Hypothesis 3, Table 2).

People who are attracted to hazardous organizations (i.e., less concerned with ethical standards) are presumably more motivated to work by external (e.g., self-interest) than internal incentives. Five dimensions of work motivation have been conceptualized: amotivation, external regulation, introjected regulation, intrinsic motivation, and identified regulation (Gagné et al., 2015). Amotivation refers to the lack of motivation to work. External regulation is defined as working to obtain rewards or avoid punishments. Introjected regulation refers to working out of internal drives (e.g., guilt). Intrinsic regulation is defined as working for enjoyment, whereas identified regulation is defined as working for internalized instrumental value or meaning embedded in work rather than for inherent enjoyment or satisfaction. According to the extant literature, people with low rather than high ethical standards (as measured by honesty-humility) can be characterized as lacking work motivation or being more motivated to work for obtaining rewards (e.g., resources) rather than for enjoyment, identification, value, or meaning (e.g., Lee et al., 2013). Therefore, positive correlations of the HOT-A with amotivation, external regulation, and negative correlations with introjected regulation, intrinsic motivation, and identified regulation will demonstrate convergent validity of the HOT-A (Hypothesis 4, Table 2).

To validate the HOT-A, we chose a widely used culture (preference) measure, the updated Organizational Culture Profile (OCP; see Measures section for details; Chatman et al., 2014). There are six cultures in the OCP: adaptability (sample culture keywords include being innovative, risk taking), integrity (having integrity, having high ethical standards), collaborative (working in collaboration with others, being team oriented), results-oriented (being results oriented, having high expectations for performance), customer-oriented (being customer oriented, listening to customers), and detail-oriented (paying attention to detail, emphasizing quality). Given that loose ethical standards also characterize hazardous organizations, we speculate that people who are more attracted to hazardous organizations are less attracted to an integrity culture. Using an earlier version of the OCP, Judge and Cable (1997) found that applicants high in agreeableness (as measured by the NEO-FFI; Costa & McCrae, 1992) indicated higher preferences for supportive and team-oriented cultures and lower preferences for aggressive, outcome-oriented, and rewards-oriented cultures. These culture dimensions have been relocated to the collaborative (supportive and team-oriented), adaptability (aggressive), and results-oriented (outcome- and rewards-oriented) dimensions in the updated OCP (Chatman et al., 2014). Given that NEO agreeableness has also been found to be positively related to morality (e.g., Zhou et al., 2019), we take Judge and Cable’s (1997) findings as suggestive evidence of the culture preferences of people with low ethical standards. We therefore speculate that people who report higher HOT-A are also more attracted to adaptability and results-oriented cultures, and less attracted to a collaborative culture. Overall, positive correlations of the HOT-A with preference for adaptability and results-oriented cultures, and negative correlations with preferences for integrity and collaborative cultures will demonstrate convergent validity of the HOT-A (Hypothesis 5, Table 2). The lack of correlations of the HOT-A with preferences for customer-oriented and detail-oriented cultures will demonstrate divergent validity of the HOT-A (Hypothesis 6, Table 2).

Predictive Validity

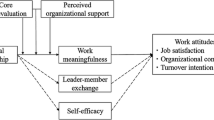

As we mentioned above, the HOT-P can be used to measure the extent to which people perceive an organization to be a hazardous organization that is characterized by abundant individual rewards, a lack of clear or strong ethical standards, an obsession with aggressive expansion, and financial risk-taking. These characteristics are presumed to negatively influence work attitudes. Specifically, individual rewards to compete may make employees feel more stressed due to the presence of potential rivals and intensive competition (Wiltshire et al., 2014). People are more likely to witness unethical behavior in an organization that cares less about ethics, and thus experience decreased well-being (Giacalone & Promislo, 2010). Aggressive expansion activities and financial risk-taking decisions can lead to more uncertainty and harm employees’ well-being (Nelson et al., 2001). Therefore, negative correlations of the HOT-P with positive work attitudes will demonstrate predictive validity of the HOT-P. The current study focuses on four work attitude outcomes: job satisfaction, organizational identification, job stress, and turnover intention (Hypothesis 7, Table 2).

Hazardous organizations are likely to have a negative impact on work motivation, as prior research has shown. For example, Gagne et al. (2015) found that employees were more likely to report higher levels of identified regulation, intrinsic motivation, and introjected regulation, and lower levels of external regulation and amotivation when working with supervisors who displayed positive (e.g., transformational leadership) rather than negative (e.g., passive leadership) leadership styles. As described above, hazardous organizations make work reward-incentivized and the work environment in such organizations is more likely to be competitive and stressful, which may undermine internal motivation and induce external motivation. Therefore, positive correlations of the HOT-P with amotivation and external regulation, and negative correlations with introjected regulation, intrinsic motivation, and identified regulation will demonstrate predictive validity of the HOT-P (Hypothesis 8, Table 2).

To examine whether hazardous organizations are less likely to retain people with high ethical standards, we also assessed the predictive validity of the HOT in a broader sense by examining the effects of the fit or congruence between the attractiveness of hazardous organizations (HOT-A) and the perception of the organization as hazardous (HOT-P; hereafter referred to as HOT-AP fit or HOT-AP congruence) on work attitudes and motivation. As noted in the theoretical background section, the ASA model posits that people who fit an organization tend to stay (Schneider, 1987; Schneider et al., 1995). The outcome activation mechanism from the STOA model posits that people are more likely to receive desirable outcomes when they work in organizations that fit their personality traits (De Vries et al., 2016a, 2016b). Both theories suggest that people should report positive work attitudes and motivation when their HOT-A and HOT-P converge on all levels. Therefore, positive relations between HOT-AP fit and positive work attitudes and motivation will demonstrate predictive validity of the HOT (Hypothesis 9, Table 2).

Broader Content Coverage of the HOT over an Existing Measure of Ethical Culture

We argue that organizational ethics is not the only organizational characteristic that influences the pre- and post-entry work attitudes of people with high ethical standards, and that the organizational characteristics described in the HOT can encompass broader relevant content than existing measures of ethical culture, e.g., integrity culture as measured by the OCP. This can be examined by comparing semi-partial correlations of both the HOT-A and OCP integrity culture preference (after controlling for their shared variance) with personality traits indicative of ethical standards. Significant and larger semi-partial correlations of the HOT-A than those of the OCP integrity culture preference will demonstrate measurement breadth of the HOT (Hypothesis 10, Table 2).

Overview of the Current Study

As noted above, the main goal of the current study is to construct and validate the Hazardous Organization Tool (HOT) that describes organizations that are aversive to people with high rather than low ethical standards. The HOT can be used to measure both the person (HOT-A) and the organization (HOT-P). To arrive at this goal, we (a) developed an initial item pool to describe hazardous organizations, (b) iteratively selected items from this initial item pool to construct the final HOT, (c) examined the convergent and divergent validity of the HOT-A, (d) examined the predictive validity of the HOT, and (e) examined the measurement breadth of the HOT-A compared to the OCP integrity culture preference.

Method

Sample Size Estimation and Outlier

We aimed for sample sizes of N ~ 300, at which factor analytic (N > 300) and correlational (N > 250) results become stable (Guadagnoli & Velicer, 1988; Schönbrodt & Perugini, 2013). Four infrequency items (e.g., “I never had hair on my head”) were inserted in random places in the HEXACO inventory to detect failure to understand instructions or careless responses (Fekken et al., 1987). We also used a statistical approach to detect noncompliant respondents (Barends & De Vries, 2019). Specifically, participants who failed 50% above of the infrequency questions, whose responses on the six domain scales indicated an average standard deviation above 1.60 (after recoding negatively worded items), or whose responses on the HEXACO-100 items (without the items addressing the Proactivity facet, see also Measures section) had a standard deviation below 0.70 (before recoding negatively worded items), were excluded from analysis (Lee & Ashton, 2018). Note that the sample size of Sample #3 was slightly lower than the sample size we aimed for, but still met the requirements to establish stable factor analytic estimates, when average factor loadings are above 0.40 (Guadagnoli & Velicer, 1988).

Participants and Procedures

We collected four samples. Samples #1, #2, and #4 consisted of working adults recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (Buhrmester et al., 2011). Sample #3 consisted of university students invited through the university research participation system. University students are a relevant population because they will typically enter the job market within a short time and need to decide whether to join organizations that are more or less hazardous. Other sample characteristics can be found in Table 2.

Participants from sample #1 sequentially provided responses to the HEXACO-104, the Dirty Dozen, the initial 85 HOT-A items (details see the sections below), and demographic questions.

When collecting samples #2 and #3, we adopted a time lagged design. Sample #2 was implemented at two time points with 1 week. At time 1, participants were randomly presented with either the selected 36 HOT-A or HOT-P items besides the HEXACO-104 and demographics. At time 2, they completed all other scales (e.g., job satisfaction; see Table 3 and the “Measures” section below for more details). Sample #3 consisted of university students who completed the HEXACO items in their first bachelor year of the psychology program between the beginning of April and May during three consecutive years (2019–2021) along with other scales (time 1). The students were invited to this study through the university research participation system in 2021 (time 2) and provided responses to the 36 HOT-A items along with other scales (see Table 3 and the “Measures” section below for more details).

Data collection of sample #4 adopted the similar design as sample #2. However, due to the omission of creating a code to match participants’ time 1 and time 2 responses, we decided to limit the data collection of sample #4 to time 1. Among the 308 valid responses, 155 completed 36 HOT-A items (sample #4 HOT-A group) while 153 completed 36 HOT-P items (Sample #4 HOT-P group).

Informed consent was obtained online from all participants.

Measures

A summary of which measures were administrated in which samples can be found in Table 3.Footnote 4

Hazardous Organization Tool

The initial set consisted of 243 descriptions, either written by the authors or adapted from published scales, manipulation materials, or master’s theses. After several iterations, including 11 subject matter experts’ evaluations, it was narrowed down to 85 descriptions before the first formal administration (item sources and other details see Supplemental Material Sect. 1). The same set of items can be used to measure two constructs: the extent to which people are attracted to hazardous organizations (hazardous organization attractiveness, HOT-A) and the extent to which people perceive an organization to be hazardous (hazardous organization perception, HOT-P). The HOT-A was measured by preceding the HOT items with the instruction “I would find it attractive to work in an organization …” and the HOT-P with the instruction “My main employer is an organization …” and both were rated on a Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. The Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities for the final 9-item HOT-A ranged from 0.73 (sample #3) to 0.85 (sample #1). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the final 9-item HOT-P was 0.87.

HEXACO Personality

The HEXACO-208 was administrated to measure the six personality traits Honesty-Humility (H), Emotionality (E), Extraversion (X), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C), and Openness to Experience (O) with 32 items for each trait, plus two times eight items measuring the interstitial facets Altruism and Proactivity (De Vries, Wawoe, et al., 2016; Lee & Ashton, 2006). We also obtained peer-report of the HEXACO-208 (sample #3, see Table 3). The HEXACO-104 is the half-length version of the HEXACO-208. Responses were provided on a Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Example items can be found on hexaco.org. The Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities for the six self-report domain scores ranged from 0.84 (sample #2 Conscientiousness) to 0.91 (sample #3 Extraversion), and for the six peer-report domain scores ranged from 0.88 (Emotionality) to 0.93 (Extraversion). The Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities for the self-report Honesty-Humility domain scores were 0.88, 0.88, 0.91, 0.85, and 0.88 in samples #1, #2, #3, #4 HOT-A group, and #4 HOT-P group, respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability for peer-report Honesty-Humility (Sample #3) was 0.91.

Dark Personality Trait

Dirty Dozen. We measured the dark triad in sample #1 with the Dirty Dozen with four items each measuring Narcissism, Psychopathy, and Machiavellianism (Jonason & Webster, 2010). All items were measured on a Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Example items include “I tend to want others to pay attention to me” (Narcissism), “I tend to be callous or insensitive” (Psychopathy), and “I have used deceit or lied to get my way” (Machiavellianism). The Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities for the subscales ranged from 0.71 (Psychopathy) to 0.81 (Machiavellianism).

Dark Factor of Personality. Sixteen items (D16) adapted by Moshagen et al. (2020) were used to measure the Dark Factor of Personality in sample #3 on a Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Example items include “I cannot imagine how being mean to others could ever be exciting” (negatively worded), “People who mess with me always regret it,” and “I would like to make some people suffer, even if it meant that I would go to hell with them.” The Cronbach’s alpha reliability was 0.80.

Organizational Culture Preference

The updated item set of the Organizational Culture Profile (OCP; O’Reilly et al., 1991) was used to measure organizational culture preference in sample #3 (Chatman et al., 2014). We used the Q-sort task as the original instrument. Participants were asked to sort the 54 items into nine categories (from “most characteristic” to “most uncharacteristic”) of an ideal organization’s culture. In the original study, Chatman et al. (2014) performed principal component analysis on the 54 items and iteratively reduced them to 34 items grouped into six factors: Adaptability, Integrity, Collaborative, Results-Oriented, Customer-oriented, and Detail-Oriented. Orthogonal factor scores for the six factors were derived in other analyses (see Chatman et al., 2014). We followed a similar procedure as Chatman et al. (2014), but failed to replicate the original structure, possibly because we used it to measure organizational culture preferences rather than organizational cultures. Therefore, we averaged the 34 items dimension-wise as the organizational culture preference scores for analysis.Footnote 5 Ipsative measures are not amenable to reliability estimation (Judge & Cable, 1997).

Work Attitudes

Work attitudes were provided in sample #2. Job satisfaction was measured by five items from Judge and Klinger (2008); organizational identification by six items from Mael and Ashforth (1992); job stress by four items developed by Motowidlo and Packard (1986); And turnover intention by three items from Yücel (2012). All work attitudes items were rated on a Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Example items include “Each day at work seems like it will never end” (job satisfaction, negatively worded), “When someone praises my main organization, it feels like a personal compliment” (organizational identification), “I almost never feel stressed at work” (job stress, negatively worded), and “I intend to make a genuine effort to find another job over the next few months” (turnover intention). The Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities were 0.93 (job satisfaction), 0.91 (organizational identification), 0.90 (job stress), and 0.93 (turnover intention).

Work Motivation

The Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale was used to measure work motivation in sample #3 (Gagné et al., 2015). This scale contains 19 items to measure five work motivation dimensions: Amotivation (e.g., “I don’t know why I’m doing this job, it’s pointless work”), External Regulation (e.g., “Because I risk losing my job if I don’t put enough effort in it”), Introjected Regulation (e.g., “Because it makes me feel proud of myself”), Intrinsic Motivation (e.g., “Because I have fun doing my job”), and Identified Regulation (e.g., “Because putting efforts in this job aligns with my personal values”). Participants were asked to indicate “why do you or why would you put efforts into your current job” by responding to the items on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = not at all to 7 = completely. The Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities for the five subscales ranged from 0.75 (Amotivation) to 0.92 (Intrinsic Motivation).

Analysis and Results

To arrive at the final validated hazardous organization scales, we (a) explored the factor structure of the 85 HOT-A items and reduced the item set (sample #1, factor analysis),Footnote 6 (b) evaluated the factor structure of the reduced item set consisting of 36 items (samples #1–3, factor analysis),Footnote 7 (c) selected the final 9 HOT items using a genetic algorithm (samples #1–3), (d) examined the convergent and divergent validity of the HOT-A by correlating it to HEXACO personality traits, dark personality traits, work motivation, and organizational culture preferences (samples #1–4, correlation analysis), (e) examined the predictive validity of the HOT by correlating the HOT-P to work attitudes and motivation and by investigating the relations of the HOT-AP fit to work attitudes and motivation (sample #2, correlation analysis and cubic response surface analysis based on polynomial regression analysis),Footnote 8 and (f) examined the semi-partial correlations between self-, peer-report Honesty-Humility, Dark Factor of Personality, and the HOT-A and OCP Integrity culture preference. Additional information about the subsequent analyses (e.g., content of the 85 HOT items, complete correlation tables, factor loading tables, robust analysis results) is provided in the Supplemental Material.

Preliminary Factor Analysis of the 85 HOT-A Items

In the first step, an exploratory factor analysis revealed the presence of (positive versus negative) wording effects (see Supplemental Material Sect. 2). To help remove the wording effects and determine to what extent the content domains are distinct from each other, we fitted a bi-factor exploratory structural equation modelling (ESEM; Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009) model with target rotation method (Reise, 2012) using Mplus version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). Specifically, we fitted a model containing a general factor, six group factors to represent the six a priori content domains, and a method factor to capture variance associated with method effects (e.g., wording effects; see also Biderman et al., 2019; Maydeu-Olivares & Steenkamp, 2018). The general factor was included to capture the shared variance among the six content domains that represent the common organizational characteristic that can satisfy the exploitative needs of people low in Honesty-Humility. The six group factors were specified to capture the unique variance after accounting for other shared variance among the items (e.g., shared variance among all the items captured by the general factor), which is also informative for deciding to what extent the content domains represent statistically discriminant factors (using several indices; see the next paragraph). Each item was set up to simultaneously load onto all factors. Loadings of the items on the general factor and their a priori group factor were freely estimated, whereas loadings on all other non-primary factors were targeted at zero, which conforms to their a priori content domain. Loadings on the method factor were targeted at 0.2 for the positively worded items and at − 0.2 for the negatively worded items. The values of 0.2 and − 0.2 were arbitrary for contrast of the items with different wordings. The differences resulting from setting other values are negligible (see also Biderman et al., 2019; Maydeu-Olivares & Steenkamp, 2018).

The bi-factor ESEM model indicated better model fit indices than the models without the general factor, the method factor, or both (reduced ESEM models; see Supplemental Material Table S5). For example, a chi-square difference test indicated adding the method factor significantly improved model fit,\({x}^{2}\)(78) = 344.23, p < 0.001.Footnote 9 Two indices were calculated: explained common variance (ECV) and percent uncontaminated correlations (PUC; Rodriguez et al., 2016). ECV estimates the proportion of variance accounted for by the general factor to the total variance accounted for by the general factor and group factors. A higher ECV value indicates a stronger general factor. PUC represents the proportion of unique correlations in a correlation matrix indicating only the influence of the general factor to the total number of unique correlations (Rodriguez et al., 2016). As PUC increases, ECV becomes less influential in affecting the potential parameter bias resulting from fitting multidimensional data to a unidimensional model (Bonifay et al., 2015; Reise et al., 2013).

The ECV was 0.60 and the PUC was 0.84. That is, the general factor explained 60% of the total variance and the PUC was sufficiently high so that fitting a unidimensional model to the data might not lead to serious parameter bias. Although the items were developed from six content domains, they failed to emerge as separate factors after removing method variance. Before going into the next step, we selected 36 items (six for each content domain of which two are negatively worded) mainly based on (a) correlation with Honesty-Humility, (b) content diversity, and (c) score distribution (keeping normal distribution as much as possible; see Supplemental Material Table S4).

Factor Analysis of the 36 HOT-A Items

In the second step, we contrasted the bi-factor ESEM models and the reduced ESEM models of the 36 HOT-A items on samples #1–3. The bi-factor ESEM solutions indicated best model fit indices except for sample #3 (Table 4; see Supplemental Material Sect. 2 for more details). The ECV values of the bi-factor ESEM model were 0.65, 0.54, and 0.50 for samples #1, #2, and #3, respectively. The PUC value of 0.53 was identical for all samples. Model-based reliability estimates \({\omega }_{H}\) and \({\omega }_{HS}\) were calculated (Reise et al., 2013; Zinbarg et al., 2005). The \({\omega }_{H}\), which assesses the proportion of variance in the total score attributable to the general factor, was 0.92, 0.89, and 0.86 for samples #1–3, respectively. \({\omega }_{HS}\) assesses the proportion of variance in the subscale score uniquely attributable to the group factor after removing the variance accounted for by the general factor. The \({\omega }_{HS}\) values were all below 0.03 for the six group factors in all samples, indicating that none of the group factors could account for substantially unique variance beyond the general factor. Overall, the above model-based indices support that the 36 items can be viewed as essentially measuring a unidimensional construct.

Item Selection for the Final HOT

In the third step, we used a genetic algorithm to construct the final unidimensional HOT due to the nearly infinite number of alternative solutions. Genetic algorithms can solve any optimization problem if the multiple criteria that need to be evaluated can simultaneously be defined by a custom fitness function (Scrucca, 2013). In our case, the genetic algorithm was set to simultaneously consider four criteria when searching for optimal scale solutions: (a) mean correlation with Honesty-Humility domain scores across samples #1–3 (maximized in the search process), (b) mean factor loading of one-factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) solutions across samples #1–3 (maximized), (c) mean SRMR and RMSEA of the one-factor CFA solutions across samples #1–3 (minimized), and (d) a minimum of one-third negatively worded items (an item-ratio cost function that was maximized; see the shared R script at https://osf.io/js7vf/). Extra constraints were set to ensure desirable scale properties: (a) a minimum of one item and a maximum of three items from each content domain and a minimum of seven items were selected to keep enough bandwidth, (b) no factor loadings were below 0.30 in any samples,Footnote 10 and (c) two relatively overlapping items from the Money Orientation domain would not be selected simultaneously.Footnote 11 The item selection was implemented in the R environment (version 4.2.2; R Core Team, 2022) with the R package GA (version 3.2.2; Scrucca, 2013, 2021; for similar applications see Moshagen et al., 2020, Olaru et al., 2019).

As shown in Table 5, model fit indices and the substantial factor loadings of the final solution (all above 0.40 with one exception in sample #2 and two exceptions in sample #3) support the one-factor structure. A conventional one-factor CFA model was also fitted to the data on the HOT-P. The model indicated perfect fit indices with all factor loadings above 0.40 and the Cronbach’s alpha reliability was 0.87. Overall, both HOT measures (the HOT-A and the HOT-P) indicated a nearly identical factor structure. Moreover, the commensurability of the measures ensures its usage in the subsequent cubic response surface analysis based on polynomial regression analysis (Humberg et al., 2020; see Predictive Validity of the HOT section below). The mean scores of the final 9-item HOT-A and HOT-P were used in the next steps.

Convergent and Divergent Validity of the HOT-A

In the fourth step, we examined the convergent and divergent validity of the HOT-A. We conducted a mini meta-analysis of the correlations involving multiple samples (Goh et al., 2016; Table 6). Table 7 presents the correlations that are only based on a single sample. Convergent validity was demonstrated by moderate to strong correlations of the HOT-A with Honesty-Humility (negative), dark personality traits (positive), and organizational culture preferences for OCP Integrity (negative), OCP Collaborative (negative), OCP Adaptability (positive), and OCP Results-Oriented (positive), which supports H1, H3, and H5. The correlations of the HOT-A with all work motivation, albeit weak for external regulation and introjected regulation, also demonstrated convergent validity (supporting H4). Divergent validity was demonstrated by much weaker correlations (most \(\left|r\right|\mathrm{s}<.20\)) with theoretically unrelated variables, such as HEXACO personality traits other than Honesty-Humility (supporting H2 and H6).Footnote 12

Predictive Validity of the HOT

As shown in Table 8, HOT-P indicated moderate to strong significant correlations with all work attitudes (supporting H7), weak to moderate correlations with four of the five work motivation as hypothesized (partially supporting H8 with H8c not supported). Next, we used cubic response surface analysis, based on polynomial regression analysis, to test whether people—whose attraction to hazardous organizations (HOT-A) converges with perception of their employer as hazardous (HOT-P)—report more positive work attitudes and motivation.

Cubic Response Surface Analysis

We conducted cubic response surface analysis in the R environment (version 4.2.2; R Core Team, 2022) with the R package RSA (version 0.10.4; Humberg et al., 2020; Schönbrodt & Humberg, 2021). The package accommodates functions that can estimate and compare second-order and third-order polynomial regression models for the investigation of quadratic and cubic response surface analysis (RSA). Importantly, the model comparison function from this package can help contrast constrained models to the full third-order polynomial regression model. Constrained models are preferred because of being more interpretable when indicating equivalent model fit indices with a full third-order polynomial regression model (Humberg et al., 2020).

The two predictors (the HOT-A and HOT-P) were centered on their grand mean and rescaled by dividing their grand standard deviation. The outcome variables were rescaled by dividing their standard deviations. This helps model convergence and keeps the commensurable nature of the predictors (Humberg et al., 2020).

Results

We first inspected the number of participants in different (in)congruenceFootnote 13 categories as suggested by Humberg et al. (2020). Participants were categorized as congruent in the HOT-A and HOT-P if their scores were within half a grand SD from one another (34.35%; see Humberg et al., 2020; Fleenor et al., 1996). The remaining participants were categorized as incongruent, and as either HOT-A \(\ll\) HOT-P (60.54%) or as HOT-A \(\gg\) HOT-P (5.10%). That is, most participants perceived their organization as more hazardous when compared with their own level of attraction to hazardous organizations.

We found that the rising ridge asymmetric congruence (RRCA) model indicated to be the best model for job satisfaction, turnover intention, job stress, and intrinsic motivation (for a more complete explanation and model comparison results see Supplemental Material Sect. 4). The “asymmetric” means that this model can test whether asymmetry in one direction (e.g., HOT-A exceeds HOT-P) is associated with higher levels of the outcome variable (e.g., job satisfaction) than in another direction (e.g., HOT-P exceeds HOT-A; by inspecting the significance and sign of the coefficient \({\widehat{b}}_{6}\) and it should be negative in this example). The “rising ridge” means that this model can estimate how the mean predictor level affects the outcome variable (the coefficient \({\widehat{u}}_{1}\) with a positive sign representing a positive relation between the mean predictor level and the outcome variable), e.g., higher mean of HOT-A and HOT-P is related to higher job stress. The significance and sign of the coefficient \({\widehat{b}}_{3}\) need to be inspected to investigate the congruence effects of the HOT-A and HOT-P on the outcome variable, and a negative sign represents that the more the HOT-A and -P converge with each other, the higher the outcome variable.

There were congruence effects of the HOT-A and HOT-P on three of the four work attitudes, and one of the five work motivations (Table 9).Footnote 14 Specifically, we found that HOT-AP congruence was associated with higher job satisfaction (\({\widehat{b}}_{3}\) = − 0.28, p < 0.001)Footnote 15 and intrinsic motivation (\({\widehat{b}}_{3}\) = − 0.21, p < 0.01), and lower turnover intention (\({\widehat{b}}_{3}\) = 0.29, p < 0.001), and job stress (\({\widehat{b}}_{3}\) = 0.25, p < 0.01), holding the asymmetric and linear levels of the two predictors constant. In addition, we found asymmetric effects between the HOT-A and HOT-P on turnover intention (\({\widehat{b}}_{6}\) = 0.06, p < 0.01), holding the congruence and linear levels of the two predictors constant, and linear level effects on job satisfaction (\({\widehat{u}}_{1}\) = − 0.63, p < 0.001), turnover intention (\({\widehat{u}}_{1}\) = 0.57, p < 0.001), job stress (\({\widehat{u}}_{1}\) = 0.47, p < 0.001), and intrinsic regulation (\({\widehat{u}}_{1}\) = − 0.45, p < 0.001), holding the congruence and asymmetric levels of the two predictors constant.

Overall, HOT-AP fit was significantly correlated with three out of the four work attitudes and one of the five work motivations in their hypothesized directions (supporting H9a, H9d, H9f, and H9g with H9b, H9c, H9e, H9h, and H9i not supported). Combined with the correlations of the HOT-P with the outcome variables, the current findings generally support the predictive validity of the HOT.

Semi-Partial Correlation Analysis

In sample #3, we used both the HOT-A and the OCP to measure organizational culture preferences. The amount of overlap between the HOT-A and the OCP Integrity culture preference was moderate (the correlation is − 0.39). As shown in Table 10, the semi-partial correlations of the HOT-A, controlling for the shared variance between the HOT-A and the OCP Integrity culture preference, with self-report and peer-report Honesty-Humility and Dark Factor of Personality were significant in their hypothesized directions (supporting H10a, H10b, and H10c). The semi-partial correlations of the HOT-A were always larger than those of the OCP Integrity culture preference, although the differences were smaller and insignificant for peer-report Honesty-Humility (supporting H10d and H10f with H10e not supported).Footnote 16 Moreover, compared to the simple correlations, there was a small decrease in the semi-partial correlations of the HOT-A with self-report and peer-report Honesty-Humility and Dark Factor of Personality. The decreases in the semi-partial correlations of Honesty-Humility and Dark Factor of Personality with the OCP Integrity culture preference were larger. In general, this is evidence that the HOT can measure meaningful organizational characteristics, not just organizational ethics, that are important to people with high ethical standards.

General Discussion

The observation that most organizations proclaim their commitment to an ethical culture but rarely succeed in having one (see Graham et al., 2022; Guiso et al., 2015) underscores the importance of the current study. Both practitioners and scholars have emphasized the important role of people, not only top leaders (e.g., CEOs) but also employees, in cultivating and strengthening an organizational culture. In fact, 37% of CEOs cited “our employees are not fully committed to the culture” as a major force preventing their organizational culture from being exactly where it should be, and 47% suggested “attracts/retains the wrong type of people in the firm” to be one of the major ways incentive compensation works against their organizational culture (Graham et al., 2022, Table 7). Similarly, Neville and Schneider (2021a) have cautioned that lagging recruitment and selection practices (e.g., “hiring people for a culture that is being left behind”, p. 44) can hold back culture change. Therefore, attracting and retaining people with high ethical standards can contribute in important ways to cultivating and strengthening an ethical culture, complement some additional ways to do so (e.g., selecting employees based on HEXACO Honesty-Humility or integrity; De Vries, 2018), and help create the conditions that enable others (e.g., appointing an ethical CEO; Ogunfowora, 2014). To facilitate a comprehensive understanding of which organizational characteristics influence the pre- and post-entry work attitudes and behaviors of people with high ethical standards, we introduced the Hazardous Organization Tool (HOT).

The final unidimensional 9-item HOT was developed and validated to measure individual differences in attraction to hazardous organizations (HOT-A) and perception of the degree to which a specific organization is hazardous (HOT-P) with different instructions and identical scale options, thus ensuring commensurability. Scores on the HOT-A had a moderate negative correlation with Honesty-Humility, moderate to strong positive correlations with dark personality traits, weak to moderate correlations with preferences for Adaptability, Results-Oriented, Integrity, and Collaborative organizational cultures, weak to moderate correlations with work motivation, and weaker correlations with theoretically unrelated constructs as hypothesized (e.g., HEXACO personality traits other than Honesty-Humility), thus demonstrating convergent and divergent validity. The predictive validity of the HOT was supported by positive correlations of the HOT-P with job stress, turnover intention, amotivation, and external regulation, and negative correlations with job satisfaction, organizational identification, intrinsic motivation, and identified regulation. The predictive validity was also supported by the HOT-AP congruence effects on three of the four work attitude outcomes and one of the five work motivation outcomes: job satisfaction, intrinsic motivation, job stress, and turnover intention. HOT-AP congruence was associated with higher job satisfaction and intrinsic motivation and lower turnover intention and job stress. In addition, all else being equal (e.g., the congruence level), there was a relatively higher turnover intention when the HOT-P exceeded the HOT-A. Furthermore, all else being equal, higher scores on the HOT-A and HOT-P were associated with lower job satisfaction and intrinsic motivation, and higher turnover intention and job stress. Overall, the current study provides evidence for the psychometric properties and the validity of the HOT and supports that hazardous organizations are less likely to attract and retain people with high ethical standards.

Practical Implications

The current literature mainly emphasizes ethical aspects of organizations when discussing attracting and retaining people with high ethical standards (e.g., Ogunfowora, 2014; cf. Lukacik & Bourdage, 2020). However, organizational ethics is clearly not the only relevant characteristic of organizations. By using semi-partial correlation analysis, we showed that the HOT can measure important organizational characteristics other than organizational ethics that affect the pre- and post-entry work attitudes of people with high ethical standards. Knowing these characteristics is especially valuable for organizations that want to cultivate an ethical culture but find it difficult to do so. Moreover, the current study reveals one potential reason for this—they might have ignored aspects that may seem less related to organizational ethics (e.g., promoting competition for salary raises or promotions that lead to a money orientation). People with high ethical standards are more willing to accept and help accelerate culture change to be more ethical and help sustain an ethical culture through their daily behaviors (Neville & Schneider, 2021a, 2021b; c.f., Chatman, 2021). To attract and retain enough people with high ethical standards to bring about such change, it may be necessary to change not only organizational ethics but also other organizational characteristics. The HOT captures these crucial characteristics.

Given the value-added nature of an ethical culture (Graham et al., 2022; Guiso et al., 2015), we assume that most of the organizations that advertise their commitment to ethical culture, but do not have it, aspire to foster an ethical culture. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that some of them simply want to use it as a marketing strategy. It may seem unlikely that applicants have accurate prior knowledge about an organization’s culture before joining it. However, previous research has shown that applicants are motivated and able to gather information about their potential employers from a variety of sources (Judge & Cable, 1997), including but not limited to recruitment websites, newspapers, social media, and word-of-mouth (e.g., Stockman et al., 2020; Van Hoye & Lievens, 2005). Organizations have limited or no control over these external sources, so applicants are likely to gain insight into aspects of the culture, including negative ones (e.g., sexual harassment), and develop hazardous organization perceptions at a very early stage. Moreover, small amounts of negative information may be sufficient to significantly reduce the attractiveness of an organization and limit people’s job pursuit in such an organization (Rozin & Royzman, 2001).

Finally, our research suggests that most people perceive their organization as more hazardous than they want it to be. In sample #2, only a small subset of participants (5.10%) rated their current employer’s hazardousness as less than their attraction to hazardous organizations. In contrast, more than half of the participants (60.54%) reported working for organizations that were more hazardous than they wanted them to be. Given the virtues of an ethical culture, which requires attracting and retaining people with high ethical standards to help foster and maintain it, organizations should consider using the HOT to examine their characteristics.

Theoretical Implications

Consistent with the propositions of the situation activation and outcome activation mechanisms from the STOA model (De Vries et al., 2016a, 2016b), we found that people with low ethical standards are more attracted to hazardous organizations (i.e., situation activation) and are more likely to report positive work attitudes when working in hazardous organizations, albeit to a lesser extent for work motivation (i.e., outcome activation). Given that the HOT was based on HEXACO Honesty-Humility, these findings collectively provide partial support for the HEXACO domain specific effects of Honesty-Humility (De Vries et al., 2016a, 2016b), and thus engage the literature on situational affordances. A full support calls for research on the HOT-AP congruence effects on behavioral outcomes.

The relations between HOT-AP fit and behavioral outcomes (e.g., unethical workplace behavior) may be more complex than with work attitudes and motivation, and different theories may suggest different hypotheses. Barrick and Parks-Leduc (2019) have postulated a substitution model of fit on behavioral outcomes.Footnote 17 They proposed that as long as the beneficial trait or characteristic of either the person or the organization is high, employees are more likely to perform better. As one of the two becomes increasingly high, the relations between the other one and performance measures would be attenuated to near zero. In the case of the HOT, if the substitution effect hypothesis is supported, employees who report either high HOT-A or high HOT-P, regardless of the level of congruence between the two, will be more likely to engage in, for example, unethical workplace behaviors. This substitution effect hypothesis is consistent with the trait activation theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003; Tett et al., 2021) and the trait activation mechanism from the STOA model (De Vries et al., 2016a, 2016b).

Another line of research supports synergistic effects of PO fit on behavioral outcomes. For example, Chatman (1989) proposed that PO fit may lead to better extra-role behaviors. Indeed, in a meta-analytic study, Kristof‐Brown and colleagues (2005) found that PO fit was positively related to job performance. To our knowledge, although both the synergistic effect and substitution effect hypotheses have theoretical underpinnings and received empirical support, no prior research has contrasted both hypotheses simultaneously. The commensurable HOT-A and -P provide an opportunity to compare the empirical support for both hypotheses through precisely formulated mathematical models, which can facilitate theoretical precision (Guest & Martin, 2021; see Humberg et al., 2019). Regardless of which hypothesis ultimately receives more empirical support, this future research can help distinguish “fitting in” from “doing well” processes, as suggested by Barrick and Parks-Leduc (2019), to examine whether and how PO fit is related to job performance beyond pre- and post-entry work attitudes.

Overall, the current study illustrates the value of this personality-centered approach. Future research may want to develop commensurable measures to assess organizational attractiveness and perceptions based on other personality traits (e.g., extraversion). For example, organizations whose front-line employees interact intensively with customers may want to attract and hire more extraverted employees and may benefit most from a culture assessment using an extraversion-focused instrument. These instruments can advance the theoretical development of the PO fit literature and Tett and colleagues’ (2021) so-called personality-oriented work analysis.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The current study has both strengths and limitations. The skewed HOT-A scores suggest that the descriptions of hazardous organization may be construed as socially undesirable. In contrast, the HOT-P scores were more normally distributed and had higher means than the HOT-A scores. This divergence suggests that, on average, people work for organizations that are perceived to be more hazardous than they want them to be. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that participants may be somewhat reluctant to admit attraction to hazardous organizations or that perceptions of their current employer as hazardous may be distorted by self-serving bias.Footnote 18 Future observational studies can help to address this issue. For example, by using a vignette-based experimental design or a field study, one might be able to observe how the ethical standards would change at different recruitment stages (e.g., job application, job offer acceptance) when applicants are exposed to low and high hazardous organizations. In addition, as noted above, Neville and Schneider (2021a) have suggested that recruitment and selection practices may lag behind culture changes. Future research might also want to examine whether hiring managers’ commitment to their current (hazardous or not) organizational culture may influence their selection criteria (e.g., the weights assigned to the criteria that indicate ethical standards).

Next, we used the psychometric soundness of the 9-item Hazardous Organization Tool-Attractiveness as the basis for selecting the final items for both the HOT-A and the HOT-P scales. The psychometric properties of the HOT-P may have capitalized on chance. However, if different items had been selected, the measurement of the HOT-A and HOT-P would no longer be commensurable, which would affect the interpretability of the congruence effects of the HOT-A and HOT-P on the outcome variables. To address this concern, we repeated the primary analyses for the top five solutions selected by the genetic algorithm with and without Sex Tolerance items, which had relatively low factor loadings (see Table 5). The results indicated that the measurement properties of the HOT(-A and -P), the correlations, and the HOT-AP congruence effects on the outcome variables (i.e., job satisfaction, intrinsic motivation, job stress, and turnover intention) were highly similar regardless of which HOT items were selected, with only minor variations when Sex Tolerance items were excluded, supporting the robustness of the current findings (see Supplemental Material Sect. 5).

Lastly, we should note that the advantage of the HOT over existing measures of ethical culture (e.g., the updated OCP; Chatman et al., 2014) may be context dependent and that we only assessed the convergent and divergent validity of the HOT-A. Our primary goal was to get a comprehensive understanding of which organizational characteristics influence the pre- and post-entry work attitudes and behaviors of people with high ethical standards. Therefore, we focused on people rather than organizations (this is why we identified organizational characteristics by starting from reviewing the evidence on personality rather than organization). The semi-partial analyses showed that this approach has the advantage of maximizing convergent validity (i.e., the correlations between the HOT-A and Honesty-Humility and dark personality traits). However, the HOT is not intended to replace existing measures of ethical culture in all contexts and in our research we did not yet validate the HOT-P with existing (ethical) culture measures. If researchers or practitioners want to conduct in-depth research on ethical culture or its relations with organizational-level outcomes, other validated measures (e.g., the updated OCP or the Corporate Ethical Virtues Questionnaire; Chatman et al., 2014; Kaptein, 2008) may be useful. However, if researchers want to examine PO fit from the perspective of personal ethical standards, the HOT may be a better choice. Organizations can use it to understand on what aspects, not just organizational ethics, they need to improve if they want to be become a more attractive and desirable place to work for people with high ethical standards.

Conclusion

In this study, we constructed and validated the Hazardous Organization Tool (HOT), which provides commensurable measurements of both the person (HOT-A, which measures the extent to which people are attracted to hazardous organizations) and the organization (HOT-P, which measures the extent to which people perceive an organization as hazardous). Our data show that the characteristics that constitute a “hazardous” organization are more likely to attract and retain people with low ethical standards (i.e., low in HEXACO honesty-humility and high in dark personality traits). Overall, the current study suggests that the Hazardous Organization Tool is a valid measure with potential to inform both research and management practice on the hazards of attracting and retaining people with low ethical standards in organizations.

Data Availability

This study was registered with Open Science Framework. The preregistrations and all data and syntax are openly accessible at https://osf.io/js7vf/.

Notes

Entrepreneurial orientation was hypothesized to be characteristic of hazardous organizations but was proved not to be. See below for more details.

This allows (a) to assess whether the organizations described in the HOT are indeed rated as more attractive (i.e., pre-entry work attitudes) to people with low rather than high ethical standards, by correlating the HOT-A with personality traits that indicate ethical standards, and (b) to assess whether (perceptions of) hazardous organizations indeed negatively affect people with high rather than low ethical standards, by examining the effects of the fit between the HOT-A and HOT-P on post-entry work attitudes. See below for more details.

Due to the number of articles using the HEXACO inventories, this repository has stopped updating references after 2019.

There is data overlap between the current study (sample #2) and another published article on a different topic. See Data Transparency and the Appendix table for more details.

We also used two other formats (i.e., Likert scale item and point allocation task) to measure preferences for the six OCP organizational cultures. The results are consistent across measurement formats. For the sake of brevity, we have included them in Supplemental Material Sect. 6.

Because of the primacy of organizational attractiveness in the person-organization interaction process (De Vries, Tybur, et al., 2016a, 2016b; Schneider, 1987; Schneider et al., 1995), we aimed to prioritize the maximization of the correlation between the HOT-A and Honesty-Humility while ensuring structural validity. We therefore based the factor analysis and item selection on people’s ratings of the attractiveness of the HOT items (HOT-A).

Sample #4 was underpowered for the factor analysis of the HOT-A items (N = 155). Therefore, these data were only included in the subsequent correlation analysis.

When evaluating the factor structure and selecting items for the final HOT, we used the corresponding complete responses to either the HOT-A or HOT-P from sample #2 (N = 343 and 334, respectively). When investigating the HOT-AP congruence effects, we used the complete responses to both the HOT-A and HOT-P from sample #2 across two time points (N = 294).

We used the maximum likelihood parameter estimates with standard errors and chi-square test statistic robust to non-normality (by using the estimator MLR in Mplus; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017) because of the non-normal distributions of the HOT-A item scores. The test statistic for model comparison was corrected following the formula by Satorra and Bentler (2010).

At first, the constraint that no factor loadings were below .30 made algorithm hardly find any optimal solutions. After checking the solutions, it appears that the Entrepreneurial Orientation items always had lowest factor loadings. Although having comparable correlations with Honesty-Humility as other items, it may indicate that the Entrepreneurial Orientation items capture variance related to another independent construct. However, this construct is relatively minor compared with the general construct measured by the rest items so that it did not emerge as a separate factor in the bi-factor ESEM models. When items from this domain were prohibited from selections, the solutions indicated prominently improved performance.