Abstract

In this research, we created and tested the validity of a Marginalized-Group-Focused Diversity Climate Scale (MGF-DCS) following Hinkin’s (1998) best practices. Previously, no measure of diversity climate has been validated. Furthermore, addressing challenges concerning the basis of diversity climate perceptions, we reviewed disparate diversity climate definitions and scales to identify its core components and sources, focusing on the treatment of organizational members who identify as marginalized group members. Using full-time employee samples (N = 1639), tests of content validity (study 1), exploratory factor analysis (study 2), confirmatory factor analysis (study 3), convergent and discriminant validity (study 4), and criterion validity (study 5) were conducted. Results suggest that the MGF-DCS comprises three subscales: (1) interpersonal valuing of marginalized groups; (2) organizational representation and inclusion of marginalized groups; and (3) organizational anti-discrimination. Furthermore, the MGF-DCS exhibited measurement invariance across marginalized group identification. In study 5, using the MGF-DCS, we tested how perceptions of diversity climate predict organizational and personal outcomes, as moderated by participants’ marginalized group identification. In general, the more participants perceived their workplaces to have a positive diversity climate, the better they saw social dynamics in their workplace (e.g. higher cohesion) and the better their personal outcomes (e.g. lower job stress); in some cases, these benefits were stronger for employees identifying as marginalized group members (e.g. less experienced discrimination). Thus, the MGF-DCS provides a reliable and valid assessment of diversity climate in organizations that can be used to advance theory, research, and diversity management practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Due to changing demographics, workplace diversity, that is, compositional differences between individuals in a work unit (e.g. Roberson et al., 2017; Thomas, 1991), is becoming an increasingly important organizational issue (Walsh & Volini, 2017). Yet, increasing demographic diversity and instituting diversity policies are not sufficient to foster positive workplace outcomes (e.g. Guillaume et al., 2012; Kossek et al., 2003). Rather, the outcomes of diversity are contingent upon organizational contextual factors, such as climate and culture (Guillaume et al., 2017). The construct of diversity climate has thus garnered attention, as it captures individuals’ subjective perceptions of the extent to which diversity is valued within the work context and how positively employees identified as marginalized group members are treated (Mor Barak et al., 1998). Marginalized groups are those in society that have been and/or currently are less accepted, treated as less valuable, and experience discrimination based on their group status (Berry, 1997).

Over the past three decades, scholars have conducted foundational work to advance research and understanding of diversity climate (e.g. Cox, 1991; Kossek & Zonia, 1993; Mor Barak et al., 1998). For instance, it has been found that in workplaces with positive diversity climates, employees report higher job satisfaction and lower turnover intentions (e.g. Chrobot-Mason & Aramovich, 2013; Hofhuis, et al., 2016), and there is some evidence that they perceive less discrimination (Boehm et al., 2014). Still, the diversity climate literature faces several challenges. To date, researchers have yet to reach a unified understanding of what constitutes diversity climate, leading to fragmented definitions and blurred boundaries between diversity climate and related—yet separate—constructs in the diversity, inclusion, and equity (DEI) research and practice space (McKay and Avery, 2015), such as inclusion climate (Nishii, 2013) and justice climate (Rupp et al., 2007).

There is also inconsistency in the literature as to what bases of diversity matter and thus the focus of diversity climate (i.e. only employees identified as marginalized group members vs. all employees), as well as the sources that employees use to form an overall perception of diversity climate (e.g. policies vs. colleagues). Consequently, diversity climate scales differ in their operational definitions and face operational challenges, including failure to specify the treatment of organizational members belonging to marginalized group, lack of domain coverage, inclusion of non-climate items, and absence of systematic validation efforts, leading critics, such as Cachat-Rosset et al. (2017), to purport that “the predictive validity of diversity climate research is at stake” (p. 10).

Accordingly, we offer the following potential contributions of the current research. The literature review of existing definitions and measures of diversity climate allows us to identify its boundaries and discern its core components and sources. Based on this review, we are able to identify key components and sources of diversity climate that focus on the treatment of marginalized organizational members. This aspect of diversity climate has been underdeveloped, and the present work can provide scholars and practitioners with a validated measure of psychological diversity climate (i.e. at the individual level) that centres diversity research and applied questions on the perceived organizational treatment of marginalized individuals. Importantly, we provide evidence of the invariance of the measure between employees with marginalized identities and employees with non-marginalized identities. As an example of how this measure can be leveraged by scholars and practitioners, we use this validated measure to explore substantive research questions about how diversity climate relates to organizational and employee outcomes, depending on participants’ marginalized group identification. Finally, in this research, we focus on individuals’ perceptions of diversity climate, as this focus allows us to validate the new measure using employees from various occupations, organizations, and industries, allowing for broader generalization of study findings. Validation studies for psychological climates are needed so that, with aggregation across unit members, later studies of organizational climate can be conducted (Ostroff et al., 2012).

What Is Diversity Climate?

In this section, we identify major themes in the diversity climate literature, present different perspectives, and provide conclusions about the basis of diversity climate perceptions, in addition to what the components and sources of diversity climate should be.

What Is the Basis of Diversity Climate Perceptions?

Most broadly, diversity climate has been defined as employees’ perceptions of the degree to which an organization values and integrates diversity into its structures (Kaplan et al., 2011; Leslie & Gelfand, 2008), pays attention to diversity issues (Hobman et al., 2004), and fosters and maintains diversity while eliminating discrimination (Gelfland et al., 2007; Pugh et al., 2008). Accordingly, some researchers conceptualize and define diversity climate without specifying any bases of diversity (e.g. Kaplan et al., 2011) or they refer to “employees” as the target (e.g. Chrobot-Mason & Aramovich, 2013; Chung et al., 2015). With such conceptualizations and operationalizations, workplace diversity can refer to any attribute on which employees differ, including demographic (e.g. gender), job-related (e.g. functional background), or psychological characteristics (e.g. personality), and can overlook issues of group-based discrimination (e.g. racism, sexism).

By referring to all employees, diversity climate can become contaminated with related constructs such as justice climate (Rupp et al., 2007) and inclusion climate (Nishii, 2013). This view of workplace diversity has been criticized for assuming that all differences carry the same weight in terms of how they affect individual and organizational functioning (Prasad et al., 2005). Indeed, the construct of inclusion climate purposefully focuses on the fair treatment of all employees, in terms of being involved in decision making, receiving equitable outcomes, and being able to bring their whole selves to work (Nishii, 2013). Previous research demonstrates that when a more positive inclusion climate exists, greater demographic diversity (e.g. gender) is associated with more positive team processes (Bodla et al., 2018; Nishii, 2013). Thus, inclusive climates can help with diversity management (Mor Barak et al., 2016). Yet, there is danger in expanding definitions of diversity to include traditionally advantaged groups (e.g. white, non-disabled, cisgender, heterosexual men), as such definitions of diversity may heighten marginalized group members’ concerns about their own inclusion within the organization.

Many scholars clearly delineate and define diversity climate as one where members of marginalized groups (including women, visible minorities, sexual orientation minorities, and people with disabilities) are treated fairly and included (e.g. McKay et al., 2007; Mor Barak et al., 1998) and where workplace discrimination is eliminated (e.g. Gelfland et al., 2007; Pugh et al., 2008). Such an emphasis recognizes the unequal power relations that exist in societies broadly and in organizations specifically, due to people’s identification with traditionally advantaged or historically marginalized groups, which results in their differential treatment and outcomes (Linnehan & Konrad, 1999; Prasad et al., 2005). Correspondingly, some measures of diversity climate identify specific forms of diversity (i.e. cultural differences; Hofhuis et al., 2012) or specific marginalized groups (i.e. women; Virick & Greer, 2012, or minorities; Hopkins et al., 2001). Other scales more broadly capture diversity along a mix of potentially marginalized identities including binary gender, age, race, religion, ethnicity, and culture (e.g. Mor Barak et al., 1998; Pugh et al., 2008). Nonetheless, other forms of diversity, such as (dis)ability, sexual orientation, and gender identity are not captured.

We contend that assessing the perceptions of treatment of all organizational members without distinguishing between advantaged or disadvantaged members weakens the purpose of studying responses to diversity. When aggregating or averaging the perceptions of representation, inclusion, and fairness of all employees, the experiences of exclusion and discrimination suffered by the marginalized minorities are diluted in the treatment of the advantaged majority. We instead propose that diversity climate definitions and measures should capture organizational members’ perceptions of how members of marginalized groups are treated. Having marginalized group members as the referent of diversity climate requires respondents to report on the treatment of those who face greater systemic and interpersonal discrimination (e.g. Ren et al., 2008; Rotundo et al., 2001; Sears & Mallory, 2014; Triana et al., 2015), less organizational fairness (e.g. Ramamoorthy & Flood, 2004; Snyder et al., 2010), and lower job satisfaction (Wee Koh et al., 2016) compared with their non-marginalized counterparts. By focusing on a climate for the treatment of marginalized group members (vs. all employees), employees’ perceptions of climate should more strongly predict outcomes for marginalized versus non-marginalized organizational members. Moreover, and importantly, a focus on the treatment of marginalized groups helps set the boundary of diversity climate from DEI associated constructs (e.g. justice, inclusion). Finally, an emphasis on “marginalized groups” (vs. specifying groups) allows for flexibility in the use of a diversity climate measure, as marginalization is a product of the context (e.g. historical, societal, political) and such understandings of who marginalized groups are differ across time and place (Prasad et al., 2005).

What Are the Theoretical Components and Sources of a Diversity Climate Focused on Marginalized Groups?

Representation and Worth of Marginalized Groups

The representation of employees identified as marginalized group members across different levels and areas of an organization (i.e. that employees are structurally integrated) is a core component of many definitions (e.g. Cox, 1994; Hobman et al., 2004; Kossek & Zonia, 1993) and measures of diversity climate (e.g. Chrobot-Mason & Aramovich, 2013; McKay et al., 2007). However, it has been argued that for representation to have real impact, marginalized group members in those roles must be respected and have power (Dwertmann et al., 2016). Others emphasize that, in a positive diversity climate, the worth of people identified as marginalized group members is recognized, such that they are valued and have influence (e.g. Dwertmann et al., 2016; Hobman et al., 2004; Lauring & Selmer, 2012). Putting this together, we propose that perceptions of the representation of organizational members belonging to marginalized groups and the recognition of their worth are integral components of a positive diversity climate.

Inclusion and Authentic Belonging of Marginalized Groups

Several definitions (e.g. Cox, 1994; Kaplan et al., 2011; McKay et al., 2007) and measures of diversity climate (e.g. Chrobot-Mason & Aramovich, 2013; Mor Barak et al., 1998; Pugh et al., 2008) involve the integration and social inclusion of employees identified as marginalized group members, that is, their embeddedness in social networks (e.g. friendships) and feelings of belongingness to fulfill the social identity need of assimilation. However, theories of social inclusion (e.g. Brewer’s Optimal Distinctiveness Theory, 1991) and organizational inclusion (Nishi, 2013; Shore et al., 2011) add uniqueness to belongingness, emphasizing the importance of treating employees in a way that makes them feel like they can be their unique, authentic selves, to fulfill the social identity need of differentiation. Indeed, an emphasis on fostering belongingness, without authenticity, can engender pressures on marginalized groups to assimilate and conform to the dominant organizational norms without appreciating their unique identities (Shore et al., 2011). Thus, we propose that a necessary component of a positive diversity climate is the social inclusion that results in experiences of authentic belonging (i.e. fulfilling both needs for assimilation and differentiation) among organizational members belonging to marginalized groups.

Justice for Marginalized Groups

Justice climate refers to the perceptions of the extent to which there are fair processes, outcomes, and interpersonal treatment within an organization or unit (Colquitt, 2001), without considering the identity of the members, and it is not necessarily related to the diversity of the workforce. In contrast, justice, or providing fair outcomes, procedures, and interpersonal treatment for employees identified as marginalized group members is a vital component of many definitions (e.g. Chrobot-Mason & Aramovich, 2013; McKay et al., 2007) and measures of diversity climate (e.g. Kossek & Zonia, 1993; Mor Barak et al., 1998). It is not possible to have a positive diversity climate if employees identified as marginalized group members are treated less fairly than their non-marginalized counterparts (Mor Barak et al., 1998). Hence, we propose that justice for organizational members belonging to marginalized groups, as perceived by members of the organization, is a necessary element of a positive diversity climate.

Elimination of Discrimination Against Marginalized Groups

The elimination of discrimination (i.e. any negative or harmful treatment based on group status against marginalized group members, Ensher et al. (2001) is seen in several definitions (e.g. Drach-Zahavy & Trogan, 2013; Gelfland et al., 2007; Pugh et al., 2008) and measures of diversity climate (e.g. Chrobot-Mason & Aramovich, 2013). A positive diversity climate cannot emerge if employees identified as marginalized group members experience discrimination, which is the opposite of them being valued, included, and treated fairly. Given that anti-discrimination efforts are a critical aspect of a positive diversity climate, we propose that organizational members need to perceive organizational efforts to eliminate discrimination against marginalized groups.

Diversity Climate’s Sources

Regarding diversity climate’s sources, there is little agreement in the field as to what or to whom people look to get a sense of workplace diversity climate. Some definitions emphasize formal organizational values, policies, and practices (e.g. Dwertmann et al., 2016; Leslie & Gelfand, 2008; McKay et al., 2007). Others additionally (Chrobot-Mason and Aramovich, 2013) or solely (e.g. Hopkins et al., 2001; Lauring & Selmer, 2012) highlight the attitudes and behaviours of other organizational members. Cachat-Rosset et al. (2017) conducted a systematic review and proposed three main sources of diversity climate based on an integration of the literature: pro-diversity values communicated by the organization and its leaders (i.e. organizational intent), pro-diversity policies and practices (e.g. programs), and other organizational members’ pro-diversity attitudes and behaviours. We therefore incorporate these three sources of diversity climate in our theorizing.

Based on our analysis of the literature, to help guide our development of a new measure of diversity climate focused on the treatment of marginalized groups, we propose a provisional definition of psychological diversity climate (for a revised definition based on findings, see the results and discussion of study 3), as referring to individuals’ perceptions of the degree to which, at work, organizational members belonging to marginalized groups are (a) represented and valued, (b) socially included with authentic belonging, (c) treated fairly, and (d) not discriminated against, as demonstrated by top leadership and organizational values, organizational policies and practices, and the general attitudes and behaviours exhibited by other organizational members. This definition clarifies the conceptual boundary between diversity climate and inclusion climate. Although inclusion climate and diversity climate measures have been conflated in previous work (e.g. Davies et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019), our definition of diversity climate actively excludes the perceived organizational treatment of people from historically advantaged groups as a focus of diversity climate; however, it does include their perceptions of how marginalized others are treated in the organization. Furthermore, we view diversity climate as encompassing elements that are not covered in current conceptualizations and operationalizations of inclusion climate, that is, the representation of marginalized group members and the elimination of discrimination against them.

Challenges with the Existing Diversity Climate Scales

Our process of scale development was informed by our critical review and evaluation of existing measures of diversity climate. Five key problems were identified, which we propose how to rectify. We address each in turn. First, some measures of diversity climate include items that tap the degree to which all employees are socially included and integrated (Chrobot-Mason & Aramovich, 2013; Mor Barak et al., 1998). To avoid construct contamination of diversity climate with more general conceptualizations of inclusion climate, we propose that diversity climate scales should focus only on the inclusion and authentic belonging of employees identified as marginalized group members.

Second, some measures of diversity climate capture respondents’ personal experiences of fair and respectful treatment (e.g. McKay et al., 2008). In other words, they capture experienced fairness or justice, which involve respondents’ beliefs about whether they are personally treated fairly (Ambrose & Schminke, 2009). However, climate involves respondents’ perceptions of routines and behaviours of others and not how the respondent personally thinks or feels (Schneider & Barbera, 2014; Schneider et al., 2013). Third, some measures of diversity climate assess justice climate (e.g. Mor Barak et al., 1998), which involves the fair treatment of all employees (Rupp et al., 2007). However, we propose that diversity climate should capture the perceptions of employees about how fairly employees identified as marginalized group members are treated.

Fourth, some measures of diversity climate assess respondents’ personal attitudes about diversity and toward marginalized groups (e.g. Hopkins et al., 2001; Kossek & Zonia, 1993; Mor Barak et al., 1998). However, personal attitudes should not be assessed with climate measures (Schneider & Barbera, 2014). Therefore, we propose that a diversity climate measure should only focus on employees’ perceptions concerning how other organizational members feel about diversity and how marginalized groups are treated.

Fifth, the mostly widely used scales in the literature differ in terms of the components and sources of diversity climate they capture, and none has undergone systematic validation efforts (see McKay et al., 2008; Mor Barak et al., 1998; Pugh et al., 2008). For example, given that the McKay et al. (2008) and Pugh et al. (2008) diversity climate scales are only 4-item long, it is difficult to achieve broad domain coverage. Moreover, while the Mor Barak et al. scale identifies different marginalized identities as bases of diversity and captures the components of representation and worth, justice, as well as inclusion, it does not capture authentic belonging or elimination of discrimination. Relatedly, the McKay et al. scale captures the components of representation and worth, as well as justice, but it does not identify marginalized identities as bases of diversity, nor does it tap inclusion and authentic belonging or discrimination. The Pugh et al. scale identifies different marginalized identities as bases of diversity and captures inclusion and authentic belonging, as well as elimination of discrimination, but it does not tap representation and worth, or justice. Finally, none of the three scales captures organizational members’ pro-diversity attitudes and behaviours. While all three scales capture diversity policies and practices, only the McKay scale captures leadership values. Thus, a diversity climate scale is needed that covers all of the key theorized components and sources of diversity climate and that has undergone validation.

The Current Research

This paper aims to provide a theoretically sound, validated tool to measure diversity climate. The use of this tool can create consistency in the operationalization of the construct and help advance the field. We develop and validate a new measure of diversity climate and test its relations to important organizational and employee outcomes. We assess diversity climate at the individual level (i.e. psychological diversity climate) by tapping individuals’ self-reported perceptions of the work context (e.g. organizational values, policies, practices). We chose to focus on psychological climate, rather than organizational climate, so that validation efforts could be conducted with employees from a wide variety of organizations to increase the potential generalizability of the scale.

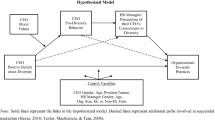

We follow the steps outlined by Hinkin’s (1998) best practices, beginning with content validity analysis (study 1), exploratory factor analysis (study 2), confirmatory factor analysis (study 3), convergent and discriminant validity analysis (study 4), and criterion validity analysis (study 5). Successful tests will reveal the following: (1) a scale with high face validity, better domain coverage than existing scales, and a clear factor structure (studies 1–3), (2) which converges with other measures of diversity climate and diverges from potentially confounding constructs (study 4), and (3) is able to predict relevant constructs, and where appropriate, differentially so for those who identify as a marginalized versus non-marginalized group member (study 5).

Across the five studies, participants were restricted to employees in the USA and Canada, as the diversity management practices are similar in the two countries (Prasad and Milles, 1997) but might differ in other cultural contexts, thereby affecting aspects of diversity climate (e.g. Holvino and Kamp, 2009; Klarsfeld et al., 2012).

Item Generation

We generated a large, initial item pool of 140 items relying on our conceptualization of diversity climate for marginalized groups, thus using a deductive method for item generation (Hinkin, 1998). The pool was created by adapting items from existing diversity climate scales (e.g. McKay et al., 2007; Pugh et al., 2008) and measures related to diversity climate, such as inclusion climate (Nishii, 2013) and diversity promises (Chrobot-Mason, 2003). We also generated novel items to capture diversity climate’s domain more comprehensively. We worded all novel and adapted items to be clear, succinct, single-barreled, refer to marginalized employees/groups, and have “this organization” as the referent. We refined items using a series of piloting studies (N = 133) with employees from MTurk, yielding 55 items. In the piloting studies, participants rated item clarity and unclear items were eliminated from the pool. We also had participants provide feedback on the item-sort task, and based on their feedback, we refined the instructions and definitions used.

Scale Development: Studies 1–4

Study 1: Content Validity

The purpose of study 1 is to test the content validity of the diversity climate items that we generated. We use an item-sort task to ensure that the items are conceptually aligned with diversity climate and not related—yet separate—constructs (Anderson & Gerbing, 1991), namely, overall justice (i.e. the degree to which one perceives a positive justice climate and that one is treated fairly; Ambrose & Schminke, 2009) and psychological safety (i.e. beliefs about whether it is comfortable for employees to express themselves at work; Edmondson, 1999). Like overall justice, diversity climate for marginalized groups involves justice climate. Like psychological safety climate, diversity climate for marginalized groups involves worth of employees and authentic belonging. However, our diversity climate items only focus on employees identified as marginalized group members, and more broadly encompass their representation, inclusion and authentic belonging, and whether the organization promotes anti-discrimination efforts. A successful test of content validity would reveal that the newly generated diversity climate items are more likely to be sorted into our definition of diversity climate for marginalized groups (vs. overall justice and psychological safety) than would be expected by chance (Anderson & Gerbing, 1991; Howard & Melloy, 2016). Accordingly, content validity would demonstrate that the diversity climate items are not contaminated with related constructs, unlike some existing diversity climate scales that appear to suffer from this problem.

Method

Participants

Thirty-five participants from MTurk, who were required to be full-time employees, proficient in English, and reside in the USA or Canada, completed the study. Following data cleaning, data of 21 women and 10 men, aged 24 to 62 (M = 45.40, SD = 10.83) were retained, which falls within recommended sample size (Howard, 2018). All resided in the USA (see supplemental materials for details about data cleaning for all studies).

Procedure

Participants were invited to complete a research study investigating how individuals think about and distinguish between concepts related to the workplace. After providing consent, participants read definitions for the three constructs. Diversity climate for marginalized groups was defined as “the degree to which an organization, its leaders, and people demonstrate that they value diversity and historically marginalized employees by including them socially, treating them fairly, and not discriminating against them.” We provided participants with a definition of historically marginalized groups as, “those who belong to groups that have been treated in society in an exclusionary or discriminatory way, either historically and/or currently (e.g., women, racio-ethnic minorities, LGBTQ + , people with disabilities, etc.).” This definition was provided across all studies. Psychological safety was defined as, “the degree to which people perceive that, in their work team, other team members can be trusted to support them and other employees, and that the team members will not punish or reject them.” Perceived overall justice was defined as, “the degree to which a person believes that he or she, personally, is treated fairly by his or her organization and that his or her organization is fair.”

Participants sorted 55 diversity climates items (e.g. “Top leadership in this organization demonstrates a visible commitment to diversity”), seven Psychological Safety Scale items (e.g. “Members of this team are able to bring up problems and tough issues”, Edmondson, 1999), and six Perceived Overall Justice Scale items (e.g. “Overall, I’m treated fairly by my organization”, Ambrose & Schminke, 2009) to the best fitting construct or to “other.” Three instructional attention check items were included (e.g. “In this organization, there are many marginalized employees. Please sort into other”). The order of items was randomized. We omitted data from participants who failed two or more of the three attention checks. Participants then completed demographics (i.e. gender, age, employment status, English proficiency, country of residence). As a conscientiousness check, participants rated how honestly and accurately they performed (1 = not at all, 2 = somewhat, 3 = moderately, and 4 = very). We omitted data from participants who scored below three on this item. Finally, participants received a unique code to be remunerated $0.40 for their participation via MTurk. This remuneration rate, and the ones we follow in subsequent studies, are in line with a median hourly rate of MTurk worker payment of $1.77/hour (Hara et al., 2018).

Results and Discussion

Substantive validity tests examine whether an item is correctly assigned to its intended construct at a rate greater than chance (Anderson & Gerbing, 1991). Following recommendations (Howard & Melloy, 2016), for a diversity climate item to pass this check, it needed to be correctly sorted by 21 of the 31 participants. Fifty-two of the 55 items met or exceeded the critical value (see Table 1 in supplemental materials for detailed results).

Study 2: Exploratory Factor Analysis

Using exploratory factor analysis (EFA), this study’s objective is to explore the underlying factor structure of the diversity climate items and, based on the results, to reduce the number of items to create a more parsimonious scale. A successful outcome of the current study would be to (a) find items with clear and strong factor loading that have broader domain coverage of the theorized components and sources of diversity climate, compared with existing scales, and (b) generate dimensions and/or an overarching scale with good reliability.

Method

Participants

We adhered to Schwab’s (1980) recommendation of item-to-participant ratio of 1:10 for EFA. Accounting for attrition, we recruited a total of 572 participants from MTurk. The same selection criteria were used as in study 1, and participants were required to not participate in previous studies of this scale validation project. Data of 520 full-time employees (273 women, 242 men, four gender non-binary) aged 19 to 87 (M = 36.90, SD = 11.12) were retained. Participants’ most common ethnic origins were White (75.19%), Black/African American (7.69%), Asian (6.35%), and Latinx (3.85%). Of the participants, 11.54% identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual or other; 11.73% identified as disabled; and 4.04% identified as Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, or Hindu. Furthermore, 55.19% identified as a non-marginalized group member and 44.81% identified as a marginalized group member. Most resided in the USA (98.65%) with the rest residing in Canada.

Procedure

Participants were invited to complete a study validating a new scale of workplace diversity climate. As in study 1, after obtaining consent, participants read a definition of “historically marginalized employees.” In random order, participants were asked to rate their agreement for 52 diversity climate items. A sample item is “Top leadership in this organization is committed to making historically marginalized employees feel included” (1 = very strongly disagree to 9 = very strongly agree). We chose a 9-point Likert scale given evidence indicating that 9-point rating scales (vs. 7- and 5-point) yield the greatest user preference for self-expression (Preston & Colman, 2000). Three instructional attention check items were also included. After completing the diversity climate items, participants were asked, “When responding to the questions above, which marginalized groups were you primarily thinking about?.”

Participants then completed a lengthier demographics questionnaire than that used in study 1, which included gender/gender identity, age, employment status, racio-ethnic background, country of residence, sexual identity, religious identification, disability status, and parents’ socioeconomic status. We asked participants if they identify as a “non-marginalized group member” or a “marginalized group member.” The same conscientiousness check as in study 1 was administered. Participants received a unique code to be remunerated $0.40 for their participation via MTurk.

Results and Discussion

A scree plot suggested a three-factor model. The parallel analysis results also indicated that three factors should be retained (eigenvalues = 31.15, 1.87, 0.58, parallel analysis 95th percentile eigenvalues = 0.72, 0.62, 0.57). We conducted an EFA using principal axis factoring (given preliminary analyses indicating KMO = 0.99, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity χ2 (1326) = 26,811.52, p < 0.001; Howard, 2016; Kaiser, 1970) and an oblique promax rotation, as dimensions could be correlated (see Table 1).Footnote 1 We used a promax rotation because it can maximize a simple factor structure (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001).

We retained items if they had a pattern coefficient of 0.40 or higher, did not load above 0.32 on another dimension, or if the cross loading had a difference less than 0.20 (Howard, 2016; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). Accordingly, eight items were eliminated. Furthermore, if a retained item was highly redundant in content with another item that had higher loading (> 0.50), it was eliminated (n = 23). We determined that a lower-loading item (e.g. “In this organization, historically marginalized employees are always welcome at social events”) was redundant if it captured the same content as a higher-loading item (e.g. “In this organization, historically marginalized employees are involved in social gatherings by other workers”). Finally, if an item did not have high face validity for its respective dimension (n = 3), it was eliminated to achieve a simple factor structure (Thompson, 2004). Accordingly, three items were deleted because their content did not match the content of most of the other items loading on that dimension. In total, 18 items were retained to create the Marginalized-Group-Focused Diversity Climate Scale (MGF-DCS). The three dimensions were strongly correlated (r ranged from 0.71 to 0.79), which may be a product of large, unrestricted variance in the item scores (Wiberg & Sundström, 2009), as sample participants were from a wide variety of occupations, organizations, and sectors, where diversity climate perceptions may differ. Reliability for the overall 18-item scale and for the three dimensions surpassed 0.85, exceeding researchers’ recommended alpha of 0.80 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

MGF-DCS’s Dimensions

The EFA results indicate that dimensions emerged neither based on the four theorized components of diversity climate (i.e. representation and worth, inclusion and authentic belonging, justice, and discrimination) nor based on the three theorized sources (organizational and leadership values, policies and practices, and other organizational members’ attitudes and behaviours). Rather, dimensions tended to cross both the components (i.e. worth, inclusion and authentic belonging; representation and inclusion; discrimination) and sources of diversity climate (i.e. interpersonal and organizational).

Dimension 1: Interpersonal Valuing of Marginalized Groups

The first dimension consisted of seven items that appear to measure the degree to which other organizational members (e.g. managers, supervisors, other employees) promote the valuing, inclusion and authentic belonging, and fair treatment of marginalized group members, as reflected by their attitudes and everyday behaviours (e.g. “In this organization, managers and supervisors draw on the talents of historically marginalized employees”). Participants’ perceptions of the degree to which managers and other employees include, value, and treat fairly employees from marginalized groups may go hand in hand possibly because managers may role model positive diversity-related behaviours for employees. This is in line with previous research showing that managers role model prosocial behaviours for employees (e.g. Hunter et al., 2013).

Dimension 2: Organizational Representation and Inclusion of Marginalized Groups

The second dimension consisted of six items representing the degree to which the organization promotes the representation and inclusion of marginalized group members, as reflected by top leadership, organizational values, and policies, practices, and culture (e.g. “This organization demonstrates complete commitment to its historically marginalized employees”). Perceptions of leaders’ and the organization’s pro-diversity values may go hand in hand with perceptions of pro-diversity organizational policies, practices, and culture, as organizational policies, practices, and culture represent the enacted values of the organization and its leadership (e.g. Nishii et al., 2008).

Dimension 3: Organizational Anti-discrimination

The third dimension consisted of five items reflecting the degree to which the organization prevents, combats, and resolves bias and discrimination against marginalized groups, as reflected by leaders’ and organizational values, policies, practices, and culture (e.g. “In this organization, there is work being done so that historically marginalized employees can feel safe from discrimination”). Again, leaders may be seen to be the source of anti-discrimination policies, practices, and culture. Whereas the first two dimensions involve promotion-oriented features of diversity climate (i.e. striving for representation, worth, inclusion and authentic belonging, and justice), this dimension involves prevention-oriented features of diversity climate (i.e. targeting prevention and elimination of discrimination).

Summary of Domain Coverage

We found that the MGF-DCS has three dimensions that do not cleanly map onto the theorized four components (i.e. representation and worth, inclusion and authentic belonging, justice, and elimination of discrimination) or three sources (i.e. top leadership and organizational values, policies and practices, and organizational members’ attitudes and behaviours) of diversity climate. Rather, one dimension clearly focuses on coworkers’ and supervisors’ attitudes and behaviours, encompassing different components of diversity climate; one dimension focuses on positive actions of the organization; and one dimension focuses on the organization avoiding negative actions. Thus, the MGF-DCS’s apparent multidimensional structure captures all proposed components and sources of diversity climate, thereby ensuring broader domain coverage of diversity climate than existing scales. In contrast, of the widely used diversity climate measures, the Mor Barak scale captures the components of representation and worth, justice, and inclusion, but not authentic belonging or discrimination. The McKay scale captures representation and worth, and justice, but not inclusion and authentic belonging or discrimination. The Pugh scale captures inclusion and authentic belonging, and discrimination, but it does not tap representation and worth, or justice. Concerning the sources, all three scales capture policies and practices, only the McKay scale captures leadership values, and none of the three scales captures organizational members’ attitudes and behaviours.

Study 3: Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The goal of study 3 is to confirm the factor structure of the MGF-DCS found in study 2 using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Thus, we hypothesize that a three-factor higher-order model of diversity climate (model 1) would emerge composed of (1) an interpersonal valuing dimension, involving perceptions of organizational members’ valuing, authentically including, and treating fairly employees identified as marginalized group members; (2) an organizational representation and inclusion dimension, involving perceptions of organizational dedication and policies to promote representation and inclusion of employees identified as marginalized group members; and (3) an organizational anti-discrimination dimension, comprising perceptions of organizational dedication and policies to work on eliminating bias and discrimination against employees identified as marginalized group members.

Psychological climate theory posits that people make sense of their work environments using overarching schemas (Burke et al., 2002; James & James, 1989). Therefore, for the hypothesized model and for some alternate models, we test a higher-order structure of diversity climate, where first-order factors in each model are explained by a higher-order diversity climate factor. To test the validity of three-factor higher-order model of diversity climate, we compare its fit with theoretically plausible alternate models. A successful confirmatory factor analysis test would reveal that the hypothesized model shows a significantly better fit than the alternate models. Therefore, evidence from the current study could confirm if the MGF-DCS has broader domain coverage than existing scales.

The first alternate model (model 2) is in line with intraorganizational network theory postulating that organizations are systems consisting of formal (e.g. organizational structures, processes, policies, values) and informal networks (e.g. interpersonal social interactions; Soda & Zaheer, 2012). Thus, we test a two-factor higher-order model based on diversity climate’s sources, whereby one dimension comprises diversity climate at the organizational level (i.e. organizational representation and inclusion, organizational anti-discrimination), and the second dimension comprises diversity climate at the interpersonal level (i.e. interpersonal valuing), with the first-order factors explained by a higher-order diversity climate factor.

In the second alternate model (model 3), we test the notion that discrimination is a separate component from all other components of diversity climate, given that efforts to eliminate and combat discrimination might not automatically translate to efforts to value marginalized group members (Avery, et al., 2008; Priola et al., 2014). Therefore, we test a two-factor higher-order model based on diversity climate’s components, whereby one factor comprises interpersonal valuing, and organizational representation and inclusion (i.e. promotion-oriented features of a positive diversity climate) and a second factor comprises organizational anti-discrimination (i.e. prevention-oriented features of a positive diversity climate), with the first-order factors explained by a higher-order diversity climate factor.

In the final alternate model (model 4), we test the notion that diversity climate is a single overarching construct, suggesting that evaluations are holistic. Thus, we test a one-factor model where diversity climate is a first-order construct that is manifested by each of the scale items with no separate dimensions (i.e. a unidimensional model).

Finally, our goal in study 3 is to conduct multigroup CFA (mCFA) to assess if the MGF-DCS’s factor structure remains the same for employees with marginalized identities and employees with non-marginalized identities, given that the former report perceptions of less positive diversity climates in their organizations than do the latter (Kossek & Zonia, 1993; Mor Barak et al., 1998; Oberfield, 2016). The mCFA analysis includes a series of model comparisons, starting with an assessment of whether the MGF-DCS demonstrates the same factor structure across the two groups (i.e. configural invariance), the relations between the items and each corresponding dimension are comparable (i.e. metric invariance), there are no systematic response biases to the items (i.e. consistently differing item intercepts) between the groups (i.e. scalar invariance), and the measurement error of each item is comparable across the groups (i.e. strict invariance). A successful test of mCFA would reveal that the MGF-DCS exhibits the same structure for participants with marginalized and non-marginalized identities and, therefore, can be reliably used to explore group differences in diversity climate.

Method

Participants

We adhered to sample size recommendations of 200 to 300 plus participants for CFA (MacCallum et al., 1999). Accounting for attrition, we recruited a total of 334 participants from MTurk. The same selection criteria were used as in previous studies. Data of 143 women, 143 men, four gender non-binary, full-time employees aged 18 to 71 (M = 35.40, SD = 10.32) were retained. Participants’ most common ethnic origins were White (71.13%), Black or African American (10.31%), Asian (6.87%), and Latinx (4.12%). Of the participants, 16.49% identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual or other; 11.00% identified as disabled; and 5.50% identified as Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, or Hindu. Furthermore, 52.92% identified as a non-marginalized group member and 47.08% identified as a marginalized group member. Most resided in the US (93.47%) with the rest residing in Canada.

Procedure

The same procedure was used as in study 2 with participants completing the 18-item MGF-DCS.

Results and Discussion

CFA with maximum likelihood estimation was conducted. We examined chi-squares and alternative fit indices to determine model fit. Cutoff criteria for model fit was a RMSEA value of 0.07 (Steiger, 2007), with values between 0.08 and 0.10, indicating mediocre fit (MacCallum et al., 1996), and TLI and CFI values greater than 0.90, indicating acceptable fit (Hooper et al., 2008). Fit indices for the hypothesized three-factor model (model 1) indicated acceptable fit (Table 2). Indices also revealed adequate fit for the alternate models; however, model 1 exhibited significantly better fit than model 2 (Δχ21 = 22.2, p < 0.001), model 3 (Δχ21 = 42.4, p < 0.001), and model 4 (Δχ23 = 84.5, p < 0.001). Thus, model 1 was used.

Each item loaded highly on its respective factor (> 0.40). Modification indices indicated that two items had high error correlations with other items in the scale, implying redundancy. Thus, two items were removed from subscale 2 (Organizational Representation and Inclusion, see supplemental materials for details). When running CFA on the 16-item scale, there was a case of a negative estimated variance for subscale 2. In line with recommendations set forth by Dillon and colleagues (1987) and Kolenikov & Bollen (2012), we investigated whether sampling fluctuations or structural misspecification caused this negative variance. The confidence intervals for the estimated variance of subscale 2 included zero, 95% CI [− 0.16, 0.08], demonstrating evidence for correct model specification. Furthermore, the likelihood ratio test was non-significant (p = 0.217), indicating that a restricted model (i.e. where the variance of Subscale 2 is specified) and a non-restricted model (i.e. where all parameters are freely estimated) fit the data equally well. Thus, we proceeded to fix the variance of this latent factor to a near zero number (Dillon et al., 1987).

The fit for the final 16-item three-factor model was good (CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.07, χ2 = 236.13, df = 102, p < 0.001). The three subscales were strongly correlated (rs ranged from 0.78 to 0.83). Cronbach’s alpha for the overall 16-item scale and for each of the three subscales exceeded 0.85 (Appendix).

mCFA Results

A series of multigroup CFAs were conducted to test measurement invariance for employees with marginalized (n = 137) and non-marginalized (n = 154) identities. We added model constraints in each step and compared each of the more constrained models to the less constrained one to determine if adding each restriction (i.e. constraining factor loadings, item intercepts, or error variances across the two groups) significantly worsened model fit (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016). We relied on a change in CFI (ΔCFI) and RMSEA (ΔRMSEA) of ≤ 0.01 to determine if the more restricted model displayed an equally good fit to the data (Rutkowski & Svetina, 2014). The results supported full measurement invariance of the 16-item scale, indicating configural invariance (χ2204 = 456.99, RMSEA = 0.05, and CFI = 0.96), metric invariance (ΔRMSEA = 0.003 and ΔCFI = 0.001), scalar invariance (ΔRMSEA = 0.001 and ΔCFI = 0.001), and strict invariance (ΔRMSEA = 0.001 and ΔCFI = 0.002).

These results suggest that for employees with marginalized identities and those with non-marginalized identities, the scale’s underlying factor structure is the same (i.e. configural invariance); the strength of the relations between items and their underlying subscales is similar between the groups (i.e. metric invariance); there is no systematic bias in how the two groups responded to the items (i.e. scalar invariance); and the residual errors for items are similar across the groups (i.e. strict invariance). Given these validation efforts, we appear to have a measure of diversity climate for which no systematic group (i.e. marginalized vs. non-marginalized identities) differences are found. Thus, in future studies conducted in specific organizational contexts, if a marginalized versus non-marginalized group difference is found, researchers can be more confident that this is due to differing experiences of diversity climate and not inherent differences in the scale’s structure.

Given the CFA results, we revise our initial definition of diversity climate to reflect the three-dimensional structure confirmed in study 3. We define workplace diversity climate at the psychological level as:

Individuals’ perceptions of the degree to which: (a) organizational members value, socially and authentically include, and treat fairly employees identified as marginalized group members, (b) the organizational leadership, policies, and culture promote the representation and social inclusion of employees identified as marginalized group members, and (c) the organizational leadership, policies, and culture work to eliminate discrimination and bias against employees identified as marginalized group members.

Supplemental Analyses and Results

Given the satisfactory fit of the one-factor model of diversity climate and the high correlations among the three subscales in the hypothesized three-factor model, it is unclear whether it is appropriate to examine an overall MGF-DCS scale score or whether there is utility in examining the MGF-DCS’s subscales. To further investigate whether it is most appropriate to treat the MGF-DCS at the subscale or total scale level, we conducted a bi-factor CFA in which variance among scale items is partitioned into the following: (a) a general factor and (b) specific subscales controlling for the general factor (see Dunn & McCray, 2020; Reise, 2012). We also compared the bi-factor model’s fit to the three-factor and one-factor models. Furthermore, we examined model-based internal reliability estimates (e.g. omega coefficients, omega hierarchical) to investigate the subscale and total scale’s reliability. Finally, we followed Haberman’s (2008) guidelines to examine the practical utility of using subscale scores by calculating the proportional reduction in mean squared error (PRMSE) for the three subscale scores and the total scale score. The findings were mixed.

First, the results revealed the bi-factor model had good fit (CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.05, χ2 = 163.60, df = 88, p < 0.001). Model fit comparisons further revealed that the bi-factor model exhibited better fit than a one-factor model (Δχ216 = 149.61, p < 0.001), revealing that some multidimensionality exists. In other words, there is variance accounted for by the subscales that is not accounted for by the overall scale. In addition, model fit comparisons revealed that the bi-factor model exhibited better fit than the three-factor higher-order model (i.e. interpersonal valuing, organizational representation and inclusion, and organizational anti-discrimination with a higher order diversity climate factor, Δχ214 = 70.08, p < 0.001). This reveals that in addition to variance in the items accounted for by the subscales, there is also variance accounted for by the overarching diversity climate construct.

The model-based internal reliability estimates (omega coefficient ω) revealed all three subscales (0.90, 0.91, 0.87) and the overall scale (0.96) were reliable. The omega hierarchical value (ωh) for the general factor was 0.92, demonstrating that it explains most of the variance in the total scale score, above and beyond the variance attributed to specific subscales. The omega hierarchical subscale (ωhs) values were all below 0.11, indicating that none of the three subscales explains variance above and beyond the general diversity climate factor. However, given the high omega reliability coefficient values and the better fit of the bi-factor model compared with the one-factor model, we followed Haberman (2008) to investigate the utility of subscale scores, computing the PRMSE for the three subscales. Results revealed that for each subscale, the PRMSEs value exceeded the PRMSEx value of the total scale score, revealing added value of subscale scores.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that, on the one hand, none of the three subscales uniquely explain variance above and beyond the general diversity climate factor when considered simultaneously. On the other hand, the better model fit of the bi-factor model compared with the one-factor model and results from the Haberman procedure suggest a certain degree of multidimensionality and possible utility in examining subscale scores. Accordingly, our findings indicate that it could be appropriate to treat the MGF-DCS at the subscale level or at the overall scale level. When doing the latter, to calculate an average score of the MGF-DCS, given that the three subscales have different numbers of items, we suggest that means be calculated at the subscale level before they are averaged. Theory and research questions should guide whether researchers investigate overall diversity climate with the MGF-DCS or if they investigate scores of the Interpersonal Valuing subscale, the Organizational Representation and Inclusion subscale, and the Organizational Anti-Discrimination subscale.

Study 4: Convergent and Discriminant Validity

The purpose of study 4 is to assess the convergent and discriminant validity of the 16-item MGF-DCS (Hinkin, 1998). To assess convergent validity, we seek to examine the MGF-DCS’s relation to alternative measures of the same construct (Carlson & Herdman, 2012; Hinkin, 1998), that is, diversity climate. We purposively excluded neighbouring constructs, such as inclusion or justice climate, which are associated with the research and practice of DEI in organizations, but do not explicitly investigate the perceived organizational treatment of employees with marginalized identities. Therefore, we examine how the MGF-DCS relates to three commonly used measures of diversity climate, namely, Mor Barak et al.’s (1998) Diversity Perceptions Survey, McKay et al.’s (2008) Diversity Climate Scale, and Pugh et al.’s (2008) Diversity Climate Scale. A successful test of convergent validity would demonstrate that the MGF-DCS strongly correlates with these measures of diversity climate.

For discriminant validity, we test the MGF-DCS’s independence from constructs it should not theoretically relate to, and with which it should not be confounded (Hinkin, 1998). A successful test of discriminant validity would reveal null or weak relations between the MGF-DCS and measures of non-related constructs. First, we considered impression management, which is people’s tendency to want to appear favourable or provide desirable responses when responding to surveys (Reynolds, 1982). It is important to demonstrate that higher scores on the MGF-DCS are not driven by participants’ desire to appear favourably. We predict:

The Marginalized-Group-Focused Diversity Climate Scale should not significantly relate to employees’ impression management.

Second, we considered the personality dimension of honesty-humility, that is, the degree to which people tend to be fair, genuine, and cooperative (Ashton & Lee, 2009). To ensure that perceiving a more positive diversity climate is not confounded with respondents’ being fair and benevolent and, therefore, a desire to see their organization as pro-diversity, we tested that scores on the MGF-DCS are unrelated to individual differences in honesty-humility. Thus, we predict:

The Marginalized-Group-Focus Diversity Climate Scale should not significantly relate to employees’ honesty-humility.

Method

Participants

A sample size of 67 participants was needed to achieve a power of 0.80 to detect a medium effect size of 0.30. Accounting for attrition, a total of 134 participants were recruited from MTurk. The same selection criteria were used as in previous studies. Data of 58 men, 27 women, full-time employees aged 22 to 59 (M = 34.35, SD = 9.64) were retained. Participants’ most common ethnic origins were White (62.35%), Latinx (18.82%), Black (14.11%), and Asian (2.35%). Of the participants, 28.24% identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual or other; 22.35% identified as disabled; and 3.53% identified as Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, or Hindu. Furthermore, 55.29% identified as a marginalized group member and 44.71% identified as a non-marginalized group member. Most participants resided in the US (98.82%) with the rest residing in Canada.

Procedure

The same procedure as in study 3 was used. Participants received a unique code to be remunerated $0.50 for their participation via MTurk.

Measures

All measures were rated on a 9-point scale from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 9 (very strongly agree).

-

1.

MGF-DCS

The 16-item MGF-DCS from study 3 was administered. As we pre-registered hypotheses at the scale level for study 4, we use a single scale score. We calculated subscale means and averaged their scores to calculate a mean MGF-DCS score.

-

2.

Diversity Perceptions Survey

Mor Barak et al.’s (1998) 16-item Diversity Perceptions Survey captures employees’ perceptions of organizational fairness, organizational inclusion, personal comfort with diversity, and personal value for diversity. A sample item is, “Managers here have a track record of hiring and promoting employees objectively, regardless of their race, sex, religion, or age.”

-

3.

McKay et al.’s (2008) Diversity Climate Scale

McKay et al.’s (2008) 4-item diversity climate scale captures employees’ perceptions of organizational dedication to diversity, respect of differing views, and experienced fair treatment. A sample item is, “The company maintains a diversity friendly work environment.”

-

4.

Pugh et al.’s (2008) Diversity Climate Scale

Pugh et al.’s (2008) 4-item diversity climate scale captures employees’ perceptions of whether the organization allows them to advance without group-based discrimination, facilitates their inclusion, and whether managers aim to recruit and retain a diverse workforce, and manage it well. A sample item is, “Managers demonstrate through their actions that they want to hire and retain a diverse workforce.”

-

5.

Impression management

Impression management was measured using the 13-item Impression Management Scale (Reynolds, 1982), which assesses people’s tendency to respond in a socially desirable manner. A sample item is, “I sometimes feel resentful when I don’t get my way” reverse keyed.

-

6.

Honesty-humility

Honesty-humility was measured using the 10-item honesty-humility sub-facet of the HEXACO-60 (Ashton & Lee, 2009), which assesses the extent to which people are fair, sincere, humble, and not greedy. A sample item is, “I wouldn’t use flattery to get a raise or promotion at work, even if I thought it would succeed.”

Results and Discussion

Preliminary Results

The three subscales of the MGF-DCS were strongly correlated (rs ranged from 0.90 to 0.92). As shown in Table 3, reliability analyses revealed that all measures exceeded researchers’ recommended alpha of 0.80.

Main Results

As hypothesized (H1), the MGF-DCS was significantly and positively correlated with the (a) Diversity Perceptions Survey (r = 0.66, 95% CI [0.52, 0.77], p < 0.001) and (b) McKay et al.’s (2008) (r = 0.82, 95% CI [0.73, 0.88], p < 0.001) and (c) Pugh et al.’s (2008) diversity climate scales (r = 0.87, 95% CI [0.81, 0.91], p < 0.001; Table 3). Thus, the MGF-DCS demonstrates good convergent validity. That the correlations are so strong could be a result of common method variance. Alternatively, despite their brevity and having not undergone systematic validation, in conjunction with their previously demonstrated predictive validity (e.g. McKay et al., 2008; Pugh et al., 2008; Newman et al., 2018; Stewart et al., 2011), these findings could be taken as additional evidence of the construct validity of the McKay and Pugh diversity climate scales. In contrast, a weaker relation was found between the MGF-DCS and Mor Barak et al. (1998) Diversity Perceptions Survey, likely because the latter also assesses respondents’ personal attitudes and values toward diversity (e.g. “I think that diverse viewpoints add value”).

As predicted, our scale did not significantly correlate with impression management (r = 0.10, 95% CI [− 0.11, 0.31], p = 0.326) or honesty-humility (r = − 0.08, 95% CI [− 0.29, 0.14], p = 0.460; Table 3). Thus, social desirability concerns do not appear to be a problem with the MGF-DCS. In contrast, Mor Barak et al.’s (1998) scale exhibited a positive relation with impression management. As well, participants’ personal levels of honesty-humility do not affect how they perceive their organizations’ diversity climate or confound their MGF-DCS scores. Finally, we conducted exploratory analyses to assess the MGF-DCS subscales’ convergent and discriminant validity. The pattern of results remained the same.

The Effects of Diversity Climate on Employees with Marginalized and Non-marginalized Identities: Study 5 Criterion Validity

The goal of study 5 is to test the criterion validity of the MGF-DCS (Hagger et al., 2017). A successful outcome would demonstrate that the scale significantly predicts constructs that exist within its theoretical network, and where appropriate, it exhibits differential predictions for participants with marginalized (vs. non-marginalized) identities. We explore the MGF-DCS’s criterion validity in three ways. First, we examine how the MGF-DCS relates to participants’ perceptions of their organization. Consistent with previous research, we predict that when employees perceive a more positive diversity climate, wherein members hold more positive attitudes toward employees identified as marginalized group members, there should be less interpersonal conflict (Hofhuis et al., 2012) and greater cohesion (Parks et al., 2008). We also reason that organizations that strive to reduce intergroup inequalities by virtue of a more positive diversity climate may have less inequalities among employees in the distribution of demands and resources. Finally, we propose that organizations with a more positive diversity climate will reduce barriers to advancement for marginalized groups and thus have a greater representation of marginalized group members in leadership. Therefore, we predict for all employees:

Those who score higher on the Marginalized-Group-Focused Diversity Climate Scale should report less relational conflict in their organization (Hypothesis 4), greater organizational cohesion (Hypothesis 5), lower workplace inequality (Hypothesis 6), and greater marginalized group leadership (Hypothesis 7).

Second, we propose that employees with marginalized identities should perceive less positive diversity climates than employees who report non-marginalized identities (Kossek & Zonia, 1993; Mor Barak et al., 1998; Oberfield, 2016), possibly due to greater first-hand experience of mistreatment (McCord et al., 2018). Thus, we hypothesize:

Marginalized group members should score lower on the Marginalized-Group-Focused Diversity Climate Scale than non-marginalized group members (Hypothesis 8).

Third, we examine how diversity climate affects employees’ personal outcomes (i.e. experienced discrimination, sexual harassment, experienced justice, job stress, job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and life satisfaction) depending on their marginalized group identification. Regarding experiences of workplace discrimination, research shows that a more positive diversity climate is associated with perceiving less discrimination toward employees with marginalized identities (Boehm et al., 2014). This is likely because organizations with a more positive diversity climate dedicate efforts (e.g. policies, procedures) that minimize marginalized group members’ experienced discrimination and promote socially inclusive interpersonal interactions. However, among White men, (a) exposure to pro-diversity messages (vs. control condition) causes greater expectations of discrimination (Dover et al., 2016), and (b) multiculturalism is implicitly associated with exclusion more so than inclusion (e.g. Plaut et al., 2011). Accordingly, we predict:

Diversity climate should interact with marginalized group identification, such that, among marginalized group members, those who score higher on the Marginalized-Group-Focused Diversity Climate Scale should report having experienced less discrimination personally; however, among non-marginalized group members, those who score higher on the Marginalized-Group-Focused Diversity Climate Scale should report having experienced more discrimination personally (Hypothesis 9).

We further reason that a positive diversity climate should lead to less sexual harassment. Although no previous research has examined the relation between diversity climate and personal experiences of sexual harassment, women (vs. men) and sexual orientation minorities (vs. heterosexuals) have been found to experience greater sexual harassment in the workplace (Konik & Cortina, 2008; Rotundo et al., 2001). Thus, we predict:

Diversity climate should interact with gender and sexual orientation minority status, such that among women and sexual orientation minorities, those who score higher on the Marginalized-Group-Focused Diversity Climate Scale should report having experienced less sexual harassment; however, among heterosexual men, scores on the Marginalized-Group-Focused Diversity Climate Scale should not significantly predict sexual harassment (Hypothesis 10).

Moreover, we examine the interactive effects of diversity climate and marginalized group identification on experienced justice (i.e. how fair the organization is perceived to be, and the fairness of how one is personally treated; Ambrose & Schminke, 2009), job stress, job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and life satisfaction. Research reveals that the effects of a more positive diversity climate on experienced justice, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions are stronger among employees with marginalized (vs. non-marginalized identities, Buttner et al., 2010; Hofhuis et al., 2012; Madera et al., 2016; Newman et al., 2018). Among employees with non-marginalized identities, these outcomes may be less directly contingent on a more positive diversity climate, given that this workplace climate does not directly target the organizational treatment of this group. Therefore, we propose:

Diversity climate should interact with marginalized group identification, such that, among marginalized group members, those who score higher on the Marginalized-Group-Focused Diversity Climate Scale should experience greater justice (Hypothesis 11), lower job stress (Hypothesis 12), greater job satisfaction (Hypothesis 13), lower turnover intentions (Hypothesis 14), and greater life satisfaction (Hypothesis 15). In contrast, among non-marginalized group members, scores on the Marginalized-Group-Focused Diversity Climate Scale should not significantly predict experienced justice (Hypothesis 11), job stress (Hypothesis 12), job satisfaction (Hypothesis 13), turnover intentions (Hypothesis 14), or life satisfaction (Hypothesis 15).

Additionally, we explore how employees with marginalized (vs. non-marginalized) identities differ in their organizational (i.e. conflict, cohesion, inequality, marginalized group leadership) and personal outcomes (i.e. discrimination, sexual harassment, justice, job stress, job satisfaction, turnover intentions, life satisfaction). Similar to our operationalization of marginalized (vs. non-marginalized) groups in Hypothesis 10, when exploring group differences in sexual harassment, we explored differences between (a) women and sexual orientation minorities and (b) heterosexual men.

Finally, exploratory analyses were conducted to examine the utility of testing the effects of MGF-DCS at the subscale level and whether they demonstrate differential predictions. If differential relations are found, this would suggest that the different dimensions of diversity climate can be targeted for different purposes (e.g. improving social relations within the organization or fostering more positive job attitudes), highlighting the utility of the new scale, compared with unidimensional diversity climate measures.

Method

Participants

For our most complex interaction hypotheses (H9 to H15), we required a sample size of 550 participants to achieve a power of 0.80 and detect a small effect size (f2 = 0.02). Accounting for attrition, a total of 853 participants were recruited from MTurk. The same selection criteria were used as in previous studies. Data of 712 full-time employees (397 men, 311 women, 2 gender non-binary, 2 other) aged 18 to 66 (M = 37.16, SD = 10.23) were retained. Participants’ most common ethnic origins were White (81.32%), Black (6.88%), Asian (5.76%), and Latinx (3.37%). Of the participants, 12.50% identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual or other; 11.10% identified as disabled; and 4.49% identified as Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, or Hindu. Furthermore, 60.11% of participants identified as a non-marginalized group member and 39.89% identified as a marginalized group member. Most resided in the USA (91.85%) with the rest residing in Canada.

Procedure and Measures

The same procedure was used as in previous studies. Unless stated otherwise, items were rated from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 9 (very strongly agree).Footnote 2 Reliabilities of each scale are reported in Table 4.

MGF-DCS

The 16-item MGF-DCS was used. As we pre-registered hypotheses at the scale level for study 5, we use a single scale score for the main analyses. We calculated subscale means and averaged their scores to calculate a mean MGF-DCS score.

Relational Conflict

Relational conflict was measured using the 3-item Relational Conflict Scale (Pearson et al., 2002), which assesses perceptions of interpersonal tension among employees. We changed the referent from “work group” to “organization.” A sample item is, “There is personal friction among members of the organization.”

Organizational Cohesion

Organizational cohesion was measured using the 6-item Group Cohesion Scale (Tekleab et al., 2009), which assesses perceptions that employees feel a sense of togetherness and act in unity to achieve goals. We changed the referent to “organization” from “work group.” A sample item is, “The members of this organization stick together.”

Workplace Inequality

Workplace inequality perceptions were measured using the 6-item Workplace Inequality Scale (van der Werf, 2019). A sample item is, “In my workplace, there is inequality in resources among people.”

Marginalized Group Leadership

We provided a definition of historically marginalized groups and then asked participants to “Please estimate what percentage of top leadership roles in your organization are held by historically marginalized group members” on a 100-point slider.

Experienced Discrimination

Experienced discrimination was measured using seven items from the 10-item Perceived Discrimination Scale (Sanchez & Brock, 1996). Items were modified to refer to group-based rather than ethnic or culture-based discrimination. A sample item is, “At work, people look down upon me because of the groups to which I belong.”

Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment was measured using the 16-item Sexual Harassment Questionnaire-Revised (Fitzgerald et al., 1995). A sample item is, “Have you ever been in a situation where someone at work made unwelcome attempts to draw you into discussion of sexual matters?” Items were rated from 1 (never) to 9 (many times).

Experienced Justice

Justice was measured using the 6-item Perceived Overall Justice Scale (Ambrose & Schminke, 2009), which assesses perceptions of whether their organization is fair to them and other employees. A sample item is, “Overall, I’m treated fairly by my organization.”

Job Stress

Job stress was measured using the 4-item Subjective Stress Scale (Motowidlo et al., 1986), which assesses people’s experiences of work-related stress. A sample item is, “I almost never feel stressed at work” reverse keyed.

Job Satisfaction

Overall job satisfaction was measured using the 3-item Job Satisfaction Scale (Cammann et al., 1983). A sample item is, “All in all, I am satisfied with my job.”

Turnover Intentions

Turnover intentions were measured using the 6-item Turnover Intention Scale (Roodt, 2004) A sample item is, “How often have you considered leaving your job?” Items were rated from 1 (never/highly unlikely/very dissatisfying) to 9 (always/highly likely/very satisfying).

Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction was measured by a single item, “In general, I am satisfied with my life” (Cheung & Lucas, 2014).

Results and Discussion

Measurement Results

As in studies 3 and 4, the three subscales of the MGF-DCS were strongly correlated (rs ranged from 0.77 to 0.83). As shown in Table 4, with two exceptions, dependent variables were only weakly to moderately correlated (< 0.70). To ensure that the dependent variables should be treated as separate constructs, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses on all our measures, which revealed that a twelve-factor model where each variable loads on a separate factor had better model fit (CFI = 0.83; TLI = 0.82; RMSEA = 0.07, χ2 = 11,457.16, df = 2636, p < 0.001) than a single-factor model that includes all variables (CFI = 0.39; TLI = 0.38; RMSEA = 0.13, χ2 = 33,629.140, df = 2700, p < 0.001; Δχ264 = 22,172, p < 0.001).

Main Results

Organizational Outcomes

As hypothesized (H4, H5, H6, H7), participants who scored higher on the MGF-DCS perceived less relational conflict (r = − 0.35, 95% CI [− 0.41, − 0.28], p < 0.001), greater organizational cohesion (r = 0.63, 95% CI [0.58, 0.67], p < 0.001), lower workplace inequality (r = − 0.43, 95% CI [− 0.49, − 0.37], p < 0.001), and more marginalized group members in leadership positions (r = 0.27, 95% CI [0.20, 0.34], p < 0.001; Table 4). Thus, it appears that when employees perceive that their organization fosters a more positive diversity climate, it promotes more positive interpersonal interactions, reduces inequalities among employees, and mitigates barriers to marginalized group members moving up the organizational hierarchy.Footnote 3 However, such potential causal relations need to be tested with cross-lagged longitudinal designs.

Group Differences

Consistent with our prediction (H8), we found that participants with marginalized identities reported a less positive diversity climate (M = 6.00, SD = 1.83), compared with participants with non-marginalized identities (M = 6.46, SD = 1.50), t (521.10) = 3.43, p < 0.001, d = 0.273 (Table 5).

Additionally, exploratory analyses revealed that compared with participants who do not identify as marginalized, those with marginalized identities perceives greater conflict (d = 0.221), lower cohesion (d = 0.207), higher workplace inequality (d = 0.300), and they experienced greater discrimination (d = 0.521), lower justice (d = 0.362), greater job stress (d = 0.206), lower job satisfaction (d = 0.294), greater turnover intentions (d = 0.304), and lower life satisfaction (d = 0.244; see Table 5). The two groups were equal only in their perceptions of how well represented marginalized group members are in leadership (d = 0.143), highlighting that this outcome captures participants’ evaluations of more objective (vs. subjective) features of their organization. Furthermore, the two groups were equal in their experiences of sexual harassment (d = 0.059). Group differences may not have emerged for sexual harassment because the measure that we used (Sexual Harassment Questionnaire-Revised; Fitzgerald et al., 1995) blends items that capture respondents’ experiences of being the target of sexual harassment, as well as their perceptions of the frequency with which sexual harassment occurs in their workplace. Overall, we find that employees with marginalized identities perceive a less positive diversity climate, and they experience worse organizational and personal outcomes, compared with employees with non-marginalized identities, with stronger group differences in their experiences of discrimination.

Personal Outcomes