Abstract

Paraeducators are often tasked with supporting students with complex communication needs (CCN) without being well prepared to promote their communication. Previous studies have focused on training paraeducators to promote communication during non-instructional contexts for limited or unspecified communication types. We extend the literature by targeting the diversity of communication opportunities during academic instruction. We used a multiple-probe-across-participants design to test the effects of behavioral skills training to increase the number and variety of communication opportunities (i.e., mands, tacts, and intraverbals) provided by three paraeducators providing instruction for students on the autism spectrum with CCN. The training package resulted in improvements in communication opportunities across all paraeducator-learner dyads. This study serves as an example of one method to promote diverse communication opportunities for students with CCN during academic instruction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Communication is a fundamental human right and is crucial for full participation in daily life (TASH, 2016). Because communication is integral to everyday routines, people may take it for granted. For example, only with communication are people able to interact with others, build social relationships, express preferences and personal feelings, refuse undesired interactions and objects, and share opinions with others (Brady et al., 2016). For people with complex communication needs (CCN; e.g., individuals on the autism spectrum who have limited vocal language), communicating with others is a significant challenge that impedes their ability to fully participate in daily life (Light & Drager, 2007). One possible solution is the use of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) systems as a means of communication for people with CCN (Biggs et al., 2018; Drager et al., 2010).

The use of an AAC system does not guarantee meaningful opportunities to communicate. MacSuga-Gage and Gage (2015) suggested that individuals with CCN should have 3–5 opportunities to respond (OTR) per minute; however, observational studies have found that students using AAC systems may have significantly fewer OTR than recommended. As one example, Andzik et al. (2016) found that students, on average, received 17 OTR per hour (i.e., 0.28 OTR per min). Relatedly, students may receive limited opportunities to communicate beyond using basic requests (Andzik et al., 2016; Chung et al., 2012). These findings suggest that instructors may benefit from additional training in strategies to create communication opportunities for students with CCN (e.g., Chung & Carter, 2013).

The practitioners best positioned to support communication throughout the school day for students with CCNs are likely paraeducators. Paraeducators outnumber special education teachers with slightly more than one paraeducator full time equivalency for each special education teacher (1.2:1; U.S. Department of Education, 2020). This ratio is reportedly as high as 12:1 in some special education classrooms (Suter & Giangreco, 2009). Given these ratios, paraeducators may be able to provide the greatest number and variety of opportunities to communicate for students with CCNs. Unfortunately, paraeducators typically have little or no training in strategies to improve communication opportunities (Carter et al., 2009), which remains an important area of research.

Behavioral skills training (BST; Miltenberger, 2015) is an evidence-based practice used to teach complex skills, including strategies to increase OTR by educators (Brock et al., 2017; Kirkpatrick et al., 2019). The core components of BST are instruction (i.e., describing the steps of a skill), modeling (i.e., demonstrating correct performance of a skill), rehearsal (i.e., simulated performance of the skill), and feedback (i.e., written or verbal praise or correction based on performance; Miltenberger, 2015). Several recent studies have successfully used BST to improve paraeducators provision of communication opportunities for students with CCNs (Andzik & Cannella-Malone, 2017; Douglas et al., 2013; Wermer et al. 2018). As one example, Wermer et al. (2018) found that three brief trainings (10–20 min) using BST resulted in paraeducators arranging a greater number of OTR and opportunities to initiate communication for students with CCNs. These studies suggest that BST can be used to teach paraeducators to improve communication opportunities for students with CCNs by increasing the number of OTR. Nevertheless, the extant literature has not considered methods to improve paraeducators’ provision of diverse communication types. Specifically, prior research has only considered OTR for narrow (e.g., requests only) or unspecified communication functions. Strategies that encourage paraeducators to provide OTR across a range of functions (i.e., verbal operants) have not been described in the extant research.

In the present study, we evaluated the effects of BST on paraeducators’ arrangement of OTR across nine communication types for students using AAC during instructional sessions. Specifically, we addressed the following research questions:

-

1.

What are the effects of a BST training package on the number of different opportunities paraeducators used to promote communication for students on the autism spectrum with CCN?

-

2.

To what degree does the BST training package affect total number of opportunities to respond for students?

-

3.

How do paraeducators rate the goals, procedures, and outcomes of the training to increase use of the different communication opportunities?

Method

Participants

Participants included three dyads of paraeducators and students with CCN at a non-public charter school for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD). The first author consulted with school administrators to identify students and staff who met the inclusion criteria. To be included, paraeducators (a) could not have had prior training in strategies to support the communication of students with CCN, and (b) must be currently providing one-to-one instruction to a student who met inclusion criteria. Students must (a) have used an AAC system as a primary means of communication; (b) have been using the AAC system for at least 6 months, (c) be eligible and receiving special education services under intellectual disability or autism classifications, and (d) be qualified for their state’s alternate assessment for students with significant cognitive disabilities.

Consent, permission, and assent procedures were collected by the first author in accordance with procedures approved by a university institutional review board. The paraeducators provided written consent to participate, the participants’ caregiver provided written permission, and the student participants provided assent. To obtain student assent, the experimenter read the assent script aloud to the student who was then given an opportunity to provide assent using their AAC. If the student did not respond, the script was repeated for a second time. If the students still did not respond, assent was assumed. A participant would be removed from the study if they engaged in behavior indicating that they no longer assented to the procedures (e.g., aggression toward the research staff or self-injurious behavior during sessions). No students responded to the assent script or met criteria to be removed from the study.

Monica and Luke

Monica was a 28-year-old Black woman who had been working in special education for 4 years. Monica had a bachelor’s degree and was a Registered Behavior Technician™. Monica provided one-to-one instruction to Luke for 40 min each day. Luke was a 9-year-old White boy on the autism spectrum with attention deficit disorder. He used a standalone AAC system (Prio) with a key guard and LAMP Words for Life (LAMP; Prentke Romich Company, 2012) software. Luke also communicated vocally using 1- to 3-word phrases. His Individualized Education Program (IEP) included two communication goals that related to communication with AAC: using his AAC to answer yes/no questions and labeling numbers 1–20. Luke received 200 min of speech therapy per month. English was the primary language spoken in Luke’s home.

Brandon and Anton

Brandon was a 28-year-old Black man with a bachelor’s degree who had been working in special education for 1 year. Brandon provided one-to-one instruction to Anton for 30 min per day 3–5 days per week. Anton was a 12-year-old Latino boy on the autism spectrum. He used an iPad with no key guard and LAMP software. Anton’s IEP included three goals related to communication with AAC: greeting his communication partner, answering yes/no questions or questions about daily activities, and using 1- to 2-word phrases to make comments or directives. Anton received 3 h of speech therapy per month. Spanish was the primary language spoken in his home. All instruction in Anton’s classroom was provided in English and the output on his AAC system also produced English.

Kim and Jaime

Kim was a 36-year-old White woman with a bachelor’s degree who had been working in special education for 1 year. Kim provided one-to-one instruction to Jaime for 20 min each day. Jaime was a 13-year-old Latino boy on the autism spectrum. Jaime used a standalone AAC system (Accent 800) with a screen divider and LAMP software. Jaime’s IEP included two goals related to communication with AAC: spontaneous requesting for desired items and requesting missing items needed to complete tasks. Jaime received 120 min of speech services per month. Spanish was the primary language spoken in his home. All instruction in Jaimie’s classroom was provided in English and the output voice on his AAC system also produced English.

Setting and Materials

The study took place at a non-public charter school for students with IDD in a large city in the Midwestern United States. The school served approximately 300 students ages 5–22 all of whom were eligible for special education services under the categories of autism spectrum disorders, intellectual disability, other health impairment, emotional disturbance, or multiple disabilities. All research activities occurred in a classroom unused by other students and staff.

Materials included a student desk and chair, a chair for the paraeducator, instructional stimuli, student rewards, and the student’s AAC system. Instructional stimuli included tracing sheets, pencils and crayons, puzzles, matching tasks, coins and bills, number lines, and number cards. Rewards included small edible (e.g., crackers, candy, pieces of fruit, and cookies) and tangible (e.g., toy cars, balls, sorting toys) items. Training materials included an AAC application (i.e., LetMeTalk; AppNotize UG, 2015), which was downloaded on the experimenter’s smart phone and used during modeling and rehearsal sessions.

Measurement

Data were collected from video recordings of 10-min sessions. The data collectors reviewed each video and recorded frequency of the dependent variables using pencil and paper datasheets.

Dependent Variables

We measured two primary dependent variables: the total number of OTR provided by the paraeducator and the type of communication opportunity. An OTR was coded for every directive or question from the paraeducator which provided the students an opportunity to use AAC to communicate in response to the question or directive. For example, an OTR was not scored if a paraeducator said “Jaime, touch the letter A” while presenting different letter flashcards as Jaime would not respond using their AAC system. However, if the paraeducator held up a letter “A” flashcard and said “Jaime, what letter is this?” an OTR was scored. Each OTR was also coded as one of nine different types of communication opportunities.

Data collectors recorded nine types of communication opportunities across three primary verbal operants (i.e., mands, tacts, intraverbals; Skinner, 1957). Specifically, each OTR was scored as one of three types of mands (i.e., requests for desired item, missing items, and requests for breaks), tacts (i.e., labeling during instruction, imbedding labeling trials into other types of instruction, and labeling/describing items during downtime) or intraverbals (i.e., fill in statements, greetings, and questions about personal information). During training, these strategies were described as ways to make requests, ways to label things in the classroom, and conversational exchanges.

Request opportunities (mands) included instances in which the parareducator was observed offering or enticing students to request for a desired item or activity (desired items), providing an instructional cue to a student but not supplying the required materials to complete the task (missing items), or offering or prompting a request to escape undesirable tasks if the student appeared frustrated (breaks). Labeling items (tacts) included instances in which the parareducator was observed asking students to label items using their AAC as part of an instructional trial (e.g., showing a student a picture of a cat and saying “what is it?”; labels), asking students to label or describe stimuli during receptive programing (e.g., “what letter did you trace?”) where the initial directive or question (e.g., “trace your name") could be completed without using the AAC (imbedded labels), or describing or labeling toys and activities during leisure time (which involved playing with non-instructional stimuli), for example, identifying the color of a toy car (label leisure). Finally, conversational exchanges (intraverbals) included any time the parareducator presented an antecedent verbal stimulus consistent with an intraverbal fill-in statement (e.g., saying “Ready… set…”), a greeting (e.g., “hello,” or “good morning”) that might be followed by a reciprocal greeting from the student, or requests for personal information (e.g., WH- questions such as “what is your phone number?”).

Interobserver Agreement

Interobserver agreement (IOA) was calculated using the mean count per interval method (Cooper et al., 2020). Observations were divided into 1-min intervals. The total frequency count for each communication strategy was reported for each 1-min interval across observers. Mean count per interval was calculated for each 1-min interval across all measured behaviors, by dividing the smaller count for a given behavior and interval by the larger count (e.g., if the first rater scored four occurrences of imbedded labels and the second rater recorded five occurrences of imbedded labels for the first interval, IOA for imbedded labels for that interval would be 80%). After calculating agreement for each interval, IOA for the 10-min session was calculated by averaging the scores from the 1-min intervals.

An independent observer reviewed 25% of video recordings across participants and intervention phases. Mean IOA for number of OTRs was 90% (range, 87–92%). Mean IOA for types of communication opportunities was 89% (range, 85–91%).

Experimental Design

We used a concurrent multiple-probe design (Gast et al., 2018) staggered across student-paraeducator dyads. The order in which participants received intervention was determined using a random number generator.

Sessions were conducted up to 3 days per week across a period of 58 consecutive school days. Paraeducator and student absences affected the total number of sessions for each dyad.

Pre-assessment

Before baseline, the experimenter conducted an interview with the paraeducator and classroom teacher using a shortened version of the open-ended functional assessment interview (Hanley, 2009). This interview was used to identify the student’s preferred items or activities and their AAC use (i.e., the type of AAC and how it was used).

Baseline

All sessions were conducted in a separate classroom with only the experimenter, paraeducator, and student present. The paraeducator was allowed to organize any materials for instruction. Once prepared, the experimenter would begin recording and say, “I want you to run this like a normal session.” The session ended after 10 min elapsed. During this instructional session, the paraeducator implemented academic instruction on IEP goals as directed by classroom teachers (e.g., matching 2D stimuli, listener skills, completing puzzles).

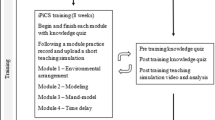

Behavior Skills Training for Communication Opportunities

The experimenter provided individual BST sessions with each paraeducator in the same setting as baseline. The mean training time was 46 min (range, 42–52 min). The experimenter (a) provided a rationale about how the strategies would improve communication outcomes for the student, (b) shared an implementation checklist that detailed how to implement each practice, (c) asked the participant to plan how they could use the different communication opportunities with their student (e.g., create a list of items to request), (d) provided verbal instructions, (e) modeled implementation of each of the opportunities, (f) allowed the paraeducator to rehearse each strategy, (g) provided verbal performance feedback (h) repeated steps d, e, and f as needed, and (i) completed a skills check after all strategies had been taught. During the skills check, the paraeducator was asked to rehearse a brief instructional session with the trainer acting as the student. Paraeducators were instructed to use at least five of the trained communication opportunities and at least ten OTRs. Monica and Luke met this performance criterion. Kim provided only seven OTRs; however, the skills check was not repeated due to time constraints.

Post-Training

Following BST, the paraeducator was observed during instructional sessions using the same procedures as described in the baseline phase. No additional training or feedback was provided to the paraeducators following the individual BST session.

Procedural Fidelity

A second observer viewed video recordings of all BST sessions to assess the degree to which the experimenter delivered the components of BST as described. The observer was trained by providing written and verbal directions, and then given the opportunity to ask questions. The observer used a 19-step implementation fidelity checklist. Fidelity was measured during all BST sessions. Percent fidelity was calculated by dividing the number of steps in the training completed correctly by the total number of steps. Mean procedural fidelity was 98.2% (range, 94.7–100%). Fidelity for Kim was scored as 18 out of 19 steps (94.7%) because the final skills check was not repeated despite her performance falling below the criterion.

Social Validity

Social validity of goals, procedures, and outcomes were assessed using a 12-item paper and pencil survey (Table 1). Survey items were rated on a five-point scale (i.e., 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree) and covered topics including the training components, trainer responsiveness, usefulness of the strategies, paraeducator improvement following training, and benefits for students. Before completing the survey, paraeducators were shown separate 5-min recordings of a baseline and post-BST session.

Results

The effects of BST on paraeducators’ performance are shown in Fig. 1. During baseline, Monica (top panel) provided a single intraverbal opportunity. All other communication opportunities were requesting a break, requesting a desired item, or imbedded labels. Following intervention, tact and mand opportunities remained high and Monica provided at least two intraverbal opportunities during each session. Total OTR increased from an average of 10.7 during baseline to 19 following BST. Brandon (middle panel) almost exclusively provided tact opportunities during baseline. Following BST, tact opportunities remained high and increases in mand and intraverbal opportunities were also observed. Brandon’s total OTR also improved from an average of 8.3 during baseline to 25.3 following BST. Kim (bottom panel) arranged a greater variety of communication types during baseline than Monica or Brandon, although mand opportunities were infrequent (M = 1.25 per observation). Following BST, an immediate increase in total OTRs and number of communication types was observed. During the first observation following BST, Kim provided opportunities to emit seven of the nine distinct communication types. Kim’s total OTRs also increased from an average of 13.5 during baseline to 20 following BST.

Paraeduactor provided opportunities to respond. Column segments show the total number of communication opportunities provided by the paraeducator. Total opportunities to respond are represented by the height of the column. Mand = request desired item, request missing item, and request break. Tact = labels, imbedded labels, and label leisure. Intraverbal = fill ins, greetings, and personal info

Table 1 shows the mean response for all social validity survey items. Paraeducators consistently rated the training components (M = 4.9) and effects of training (M = 4.7) positively; however, one participant rated their improvement following BST neutrally.

Discussion

Despite the importance of arranging frequent and diverse communication opportunities for students with CCNs, students may infrequently receive opportunities commensurate with prior recommendations (Andzik et al., 2016; MacSuga-Gage & Gage, 2015). In the present study, we observed improvements in the total number and variety of communication opportunities presented by paraeducators following BST. These findings suggest that paraeducators’ performance can be improved following a single session of BST. Moreover, the current findings extend previous research by explicitly training paraeducators to provide communication opportunities that are diverse in function. Prior research has typically targeted only basic requests (i.e., mands; e.g., Bingham et al., 2007; Lorah & Parnell, 2017) or have not described the targeted functions (e.g., Andzik & Cannella-Malone, 2019; Douglas et al., 2013; Wermer et al. 2018), yet the current study found that BST resulted in improvements across mand, tact, and intraverbal operants. This finding is noteworthy as the paraeducators differed in the types of communication opportunities provided before training. Specifically, Kim provided several mand, tact, and intraverbal communication opportunities during baseline. In contrast, Brandon almost exclusively arranged tact opportunities. Nevertheless, all the paraeducators exhibited improvements in both the number of communication opportunities and types following BST. It is possible that if the current training emphasized a single type (e.g., mands), similar improvements would not have been observed, which remains an area of future research.

The current findings further extend the literature on paraeducator-delivered communication instruction for students with CCN by demonstrating that communication opportunities can be effectively embedded during academic instruction. These results extend previous research on methods to train paraeducators to arrange communication opportunities in non-instructional settings such as recess (Bingham et al., 2007), snack or mealtimes (Wermer et al. 2018), or story times (Douglas et al., 2013). These findings suggest, with sufficient training and support, paraeducators can effectively arrange communication opportunities throughout the school day.

The results from this study provide further evidence of the social validity of BST packages. Paraeducators agreed or strongly agreed that they liked training that included mand, tact, and intraverbal examples and found the BST package to be useful. As previously discussed, much of the instruction and interaction provided to students with IDD may be implemented by paraeducators (Giangreco et al., 2010). While it is important that this instruction takes place under the direction and supervision of a special education teacher, it is also important to ensure that training procedures targeting paraeducator performances are socially valid to ensure proper implementation (Rispoli et al., 2011). While the current findings suggest that BST was socially valid, future research might identify whether paraeducators’ ratings of social validity are correlated with performance outcomes, such as procedural fidelity.

Several limitations of this study should be mentioned and considered as possible areas for future research. First, the current study included individual trainings for each paraeducator. Such an arrangement is likely not feasible in typical school-based settings as school administrators and supervising teachers may have limited time or other resources to train paraeducators. Future researchers might address this limitation by assessing the efficacy and social validity of similar BST packages when delivered to larger groups of paraeducators. Second, the present study included brief (i.e., 10-min) observations, which limit the conclusions that can be made regarding the paraeducators provision of communication opportunities during other instructional or non-instructional periods. Future research might seek to evaluate improvements in paraeducators’ performance that extend beyond the training conditions and consider methods to promote generalization to further improve the efficacy and efficiency of the BST package. Finally, the current study did not include measures of student performance. Although the focus of the current study was on the paraeducator’s behavior, it is unclear whether a greater number or diversity of communication opportunities affected the students’ within-session performance or progress towards their IEP goals. Future research should include measures of student and paraeducator performance, which may also require further refinement of the training package to better support the needs of individual students or paraeducators.

The findings from the current study extend prior research by demonstrating the efficacy of BST to increase the number and variety of communication opportunities for three students with CCN. These results suggest that paraeducators can be taught to support students’ communication needs beyond simple requests and during instructional periods. In doing so, paraeducators might better prepare students with CCN to fully participate in the range of complex and diverse communication experiences available to their peers.

References

Andzik, N., & Cannella-Malone, H. I. (2017). A review of the pyramidal training approach for practitioners working with individuals with disabilities. Behavior modification, 41(4), 558–580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445517692952

Andzik, N. R., & Cannella-Malone, H. I. (2019). Practitioner implementation of communication intervention with students with complex communication needs. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 124(5), 395–410.

Andzik, N. R., Chung, Y. C., & Kranak, M. P. (2016). Communication opportunities for elementary school students who use augmentative and alternative communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 32(4), 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2016.1241299

AppNotize UG. (2015). LetMeTalk (1.4.32) [Mobile app]. App store. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/letmetalk/id919990138

Biggs, E. E., Carter, E. W., & Gilson, C. B. (2018). Systematic review of interventions involving aided AAC modeling for children with complex communication needs. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 123(5), 443–473. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-123.5.443

Bingham, M. A., Spooner, F., & Browder, D. (2007). Training paraeducators to promote the use of augmentative and alternative communication by students with significant disabilities. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 42(3), 339–352.

Brady, N. C., Bruce, S., Goldman, A., Erickson, K., Mineo, B., Ogletree, B. T., Paul, D., Romski, M., Sevcik, R., Siegel, E., Schoonover, J., Snell, M., Sylvester, L., & Wilkinson, K. (2016). Communication services and supports for individuals with severe disabilities: Guidance for assessment and intervention. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 121(2), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-121.2.121

Brock, M. E., Cannella-Malone, H. I., Seaman, R. L., Andzik, N. R., Schaefer, J. M., Page, E. J., et al. (2017). Findings across practitioner training studies in special education: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Exceptional Children, 84, 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402917698008

Carter, E., O’Rourke, L., Sisco, L. G., & Pelsue, D. (2009). Knowledge, responsibilities, and training needs of paraprofessionals in elementary and secondary schools. Remedial and Special Education, 30(6), 344–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932508324399

Chung, Y. C., & Carter, E. W. (2013). Promoting peer interactions in inclusive classrooms for students who use speech-generating devices. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 38(2), 94–109. https://doi.org/10.2511/027494813807714492

Chung, Y. C., Carter, E. W., & Sisco, L. G. (2012). Social interactions of students with disabilities who use augmentative and alternative communication in inclusive classrooms. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117(5), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-117.5.349

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis. Pearson.

Douglas, S. N., Light, J. C., & McNaughton, D. B. (2013). Teaching paraeducators to support the communication of young children with complex communication needs. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 33(2), 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121412467074

Drager, K., Light, J., & McNaughton, D. (2010). Effects of AAC interventions on communication and language for young children with complex communication needs. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine, 3(4), 303–310. https://doi.org/10.3233/PRM-2010-0141

Gast, D. L., Lloyd, B. P., & Ledford, J. R. (2018). Multiple baseline and multiple probe designs. In J. R. Ledford & D. L. Gast (Eds.), Single case research methodology: Applications in special education and behavioral sciences (pp. 239–282). Routledge.

Giangreco, M. F., Suter, J. C., & Doyle, M. B. (2010). Paraprofessionals in inclusive schools: A review of recent research. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 20(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474410903535356

Hanley, G. P. (2009). Implementation assistance. Practical Functional Assessment. https://practicalfunctionalassessment.com/implementation-materials/.

Kirkpatrick, M., Akers, J., & Rivera, G. (2019). Use of behavioral skills training with teachers: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Education, 28, 344–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-019-09322-z

Light, J., & Drager, K. (2007). AAC technologies for young children with complex communication needs: State of the science and future research directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 23(3), 204–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434610701553635

Lorah, E. R., & Parnell, A. (2017). Acquisition of tacting using a speech-generating device in group learning environments for preschoolers with autism. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 29(4), 597–609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-017-9543-3

MacSuga-Gage, A. S., & Gage, N. A. (2015). Student-level effects of increased teacher-directed opportunities to respond. Journal of Behavioral Education, 24(3), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-015-9223-2

Miltenberger, R. G. (2015). Behavior modification: Principles and procedures. Cengage Learning.

Prentke Romich Company. (2012). LAMP Words for Life (2.26.1) [Mobile app]. App store. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/lamp-words-for-life/id551215116

Rispoli, M., Neely, L., Lang, R., & Ganz, J. (2011). Training paraprofessionals to implement interventions for people autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 14(6), 378–388. https://doi.org/10.3109/17518423.2011.620577

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Suter, J. C., & Giangreco, M. F. (2009). Numbers that count: Exploring special education and paraprofessional service delivery in inclusion-oriented schools. The Journal of Special Education, 43(2), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466907313353

TASH. (2016). TASH resolution on the right to communicate. https://tash.org/about/resolutions/tash-resolution-right-communicate-2016/

U.S. Department of Education. (2020). Office of Special Education Programs. Retrieved from Annual reports to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act: https://www2.ed.gov/about/reports/annual/osep/2020/index.html

Wermer, L., Brock, M. E., & Seaman, R. L. (2018). Efficacy of a teacher training a paraprofessional to promote communication for a student with autism and complex communication needs. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 33(4), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357617736052

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Informed Consent

A university institutional review board approved all procedures in this study, informed consent, intervention approaches, and data collection and review.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anderson, E.J., Brock, M.E. & Shawbitz, K.N. Training Paraeducators to Promote Communication Opportunities for Students with Complex Communication Needs. J Behav Educ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-024-09548-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-024-09548-6