Abstract

The supervision of field experiences is an indispensable component of Board-Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA®) training. During the supervised field experience, supervisors regularly provide performance feedback to trainees for the purpose of improving fidelity of implementation of various assessments and interventions. Emerging evidence supports the efficacy of using telehealth to train teachers and parents to implement interventions, but no study has evaluated the effectiveness of the remote delayed performance feedback among individuals completing BCBA® training. We used videoconference equipment and software to deliver remote delayed performance feedback to seven participants enrolled in a graduate program and completing supervised field experience. Remote delayed performance feedback was provided regarding participants’ implementation of caregiver coaching. The results indicate that delayed performance feedback provided remotely increased the correct implementation of caregiver coaching. These preliminary results indicate the efficacy of remote supervision and delayed performance feedback.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Professionals seeking certification within the field of behavior analysis are required to accrue experience hours to ensure they receive extensive supervision of their implementation of common behavior-analytic teaching strategies (BACB, 2022). Not only is quality supervision imperative to improve the professional’s implementation of high-quality services, but effective and intensive supervision improves client outcomes (Eikeseth et al., 2009). The Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB) Handbook explicitly state that “The purpose of supervision is to improve and maintain the behavior-analytic, professional, and ethical repertoires of the trainee and facilitate the delivery of high-quality services to trainee’s clients.” (BACB, 2022, pg. 17). Many aspects of the provision of supervision are outlined in the Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts (2021). This includes the volume of supervisees a supervisor can oversee, the extent to which a supervisor is competent to provide supervision, and the way in which supervisors should provide performance feedback to their supervisees. The Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts specifies that performance feedback is provided in a reasonable time frame, is designed to positively impact performance, and is documented when appropriate.

Performance Feedback

In educational settings, performance feedback is not a strictly defined protocol, rather a set of elements that can be combined in a number of variations to best fit the context (Fallon et al., 2015). At a minimum, performance feedback involves the acknowledgement of correctly and incorrectly implemented intervention components (Minor et al., 2014; Roscoe et al., 2006). However, according to a review of the literature, several additional elements are common including praise and reinforcement, role-play, a review of graphically displayed data, problem-solving, and goal setting (Fallon et al., 2015). Performance feedback is meant to act as an instruction or guide for trainees and can function as either a reinforcer or punisher depending on how it is used (Mangiapanello & Hemmes, 2015). Although the mechanisms behind performance feedback are not clearly understood, researchers have demonstrated the importance of the discriminative function when the individuals receiving feedback are sufficiently motivated to master the target skill (Roscoe et al., 2006).

In a meta-analysis on performance feedback that included applications from a variety of educational and professional settings, Sleiman et al., (2020) found that performance feedback most often produced large and very large effect sizes with Tau-U scores ranging from 0.81 to 0.91. Previous reviews had suggested that performance feedback was more effective when introduced in combination with other intervention components (e.g., goal setting; Alvero et al., 2001; Balcazar et al., 1985); however, within this meta-analysis, the applications of performance feedback in isolation were as effective and, in some instances, more effective than multi-component interventions. These researchers also collected data on the effectiveness of immediate feedback (i.e., feedback delivered within 60 s from when the target behavior occurred) in comparison to delayed feedback. Although many of the included studies did not incorporate immediate feedback, immediate feedback was found to be more effective relative to delayed feedback. In contrast, the findings of Zhu and colleagues (2020) support the use of delayed performance feedback as an independent intervention. Based on these contrasting results, additional research is needed to determine under what conditions delayed feedback is most effective.

Effective and Remote Supervision

Delivery of performance feedback traditionally involves a supervisor on site to provide feedback directly face-to-face (Fallon et al., 2015). However, with recent advancements in technology (e.g., telehealth), it is becoming a more common practice for supervisors (e.g., BCBAs®) to provide feedback remotely (Neely et al., 2017; Warrilow & Eagle, 2020). Remote supervision has many benefits in regard to providing efficient and effective feedback and supervision across individuals. Efficiency of supervision can directly relate to the number of supervisees to which a supervisor can provide high-quality supervision. This can, in turn, increase the number of well-trained BCBAs®, thus increasing the number of clients who can benefit from behavioral services. The importance of efficient supervision has been highlighted by the exponential increase in the number of BCBA® certificants. Deochand and Fuqua (2016) reported a 400% increase of BCBA® certificants across two 8-year periods starting in 1999 and concluding in 2014. Based on their analysis, they predicted that as of 2020, there could be between 42,000 and 60,000 BCBAs® if the trend of growth was to continue. As of April 1st, 2021, there were 45,915 BCBA® certificants within the United States (BACB, 2021). With this growth trajectory, it is likely that there will be more professionals seeking certification in the coming months and years.

Despite this exciting growth rate within the field of behavior analysis, supervisors report not having enough time to implement quality supervision (Sellers et al., 2019). It is necessary to develop strategies to ensure that supervisors have enough time to handle the increasing demand. One such strategy is the use of remote supervision. BCBAs® may find that they can provide support and consultation to a greater number of families when using remote supervision because behavior analytic services become accessible to individuals who would normally be excluded based on where they live (Chipchase et al., 2014; Wacker et al., 2013). Remote supervision also promotes collaboration among professionals due to reduced burdens related to traveling (Katzman, 2013). The use of remote supervision can also allow supervisors to provide more strategic supervision such that they can observe and support trainees at critical times during their sessions (e.g., while addressing challenging behavior, when implementing a new protocol) rather than supervising at an arbitrarily scheduled time. Additionally, trainees have reported that although they preferred in-person supervision, they were satisfied with remote group and individual supervision (Simmons et al., 2021).

Effective supervision is required for advancing the professional development of behavior analysis trainees. Performance feedback that allows a trainee to improve their accurate delivery of assessments and interventions is critical in improving treatment fidelity (DiGennaro-Reed et al., 2011; Minor et al., 2014; Zawacki, et al., 2018). Treatment fidelity refers to the extent to which the implementation of an intervention adheres to the predetermined protocol (Perepletchikova et al., 2007; Waltz et al., 1993). This includes all the necessary responses encompassed within the intervention including presenting the correct antecedent stimuli and providing the appropriate consequence (Minor et al., 2014). When interventions are not implemented with high levels of fidelity, the effectiveness of the intervention is substantially compromised (Fryling et al., 2012). In contrast, high levels of treatment fidelity typically result in improved outcomes, including correct responding and lower levels of challenging behavior (Carroll et al., 2013; Suess et al., 2014). For example, researchers have demonstrated that participants’ compliance was higher for demands that were associated with 100% fidelity and considerably lower for demands that were associated with 50 or 0% fidelity (Wilder et al., 2006).

Remote supervision includes a supervisor providing training, observation, and feedback from a different location (Zhu et al, 2020). In a typical telehealth model, trainees connect with clients and supervisors via a videoconferencing platform such as VSee® (e.g., Gerow et al., 2021), Vidyo (e.g., Tsami et al., 2019), or Zoom (e.g., Zhu et al., 2020). For example, Zhu and colleagues used delayed performance feedback to increase therapist fidelity of implementation for discrete trial training (DTT) and incidental teaching. Following each session, the researcher provided performance feedback to the interventionist at an unspecified time prior the next client session. Initially, the researchers introduced performance feedback for only one of the teaching procedures (e.g., DTT) to compare fidelity with and without feedback. They found that participants fidelity of implementation only improved following the introduction of remote delayed performance feedback.

Caregiver Coaching

A slightly different remote supervision arrangement includes supervisors observing trainees providing caregiver coaching (Neely et al., 2017). For example, trainees may provide remote coaching to caregivers who then directly implement the procedures with their child. Typically, when caregivers are coached to implement behavioral interventions with high fidelity, there is a corresponding improvement in their child’s behavior such as an increase in socially significant skills or reduction in challenging behavior (Gerow et al., 2021; Lindgren et al., 2020; Machalicek et al., 2016). Despite these positive findings, there are some important differences between providing caregiver coaching in-person and via telehealth which must be considered (Lerman et al., 2020). These differences include technological difficulties as well as logistical difficulties such as modeling desired behavior over video or helping intervene if the child engages in challenging behavior. Trainees must receive adequate supervision when providing caregiver coaching remotely to ensure they accurately and effectively shape the caregiver’s behavior.

Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to evaluate the extent to which remote delayed performance feedback increased the percentage of correctly implemented caregiver coaching steps among behavior analysis trainees. We also evaluated the social validity of remote supervision.

Method

Participants

Seven graduate students enrolled in a master’s degree program in educational psychology participated in this study. The participants were enrolled in an applied behavior analysis specialization, had completed about half of the courses of the university’s verified course sequence, and were completing a supervised field experience according to BACB standards (BACB, 2022). To be eligible to participate in this study, the graduate student must have accurately implemented no more than 70% of the steps for caregiver coaching during baseline. This criterion was selected due to being below the mastery criterion level by a considerable amount which would allow for improvement following delayed performance feedback. All seven participants met this criterion. All participants had successfully completed coursework on DTT and preference assessments and had supervised experience implementing both procedures directly with clients. Course and field experience evaluations conducted prior to this study indicated they had sufficient knowledge of both procedures. Each student had to demonstrate 85% accuracy in implementing these procedures with a doctoral student serving as the confederate child. In addition, participants experienced providing remote caregiver coaching under the supervision of their instructor during their fieldwork course. In accordance with the institutional review board (IRB) approval for this study, each participant gave verbal consent after reviewing the study consent form prior to beginning the study.

A confederate caregiver and child also participated in research sessions. Across all sessions, the second author served as a confederate caregiver and directly implemented the procedures. Her 3-year-old typically developing child served as the child during all sessions.

Settings and Materials

The following individuals were present for each session: (a) the participant, (b) one or two experimenters, and (c) a confederate caregiver and child (i.e., the second author and her child). Each participated in telehealth sessions via Zoom from different locations. Participants were free to log in to sessions at a location of their choosing; therefore, at times some participants logged-in from classrooms located on campus or at the university-affiliated applied behavior analysis clinic. For other sessions, the participants logged in from their own homes. The experimenters and confederate caregiver logged in from their homes for all sessions.

To participate in the study, participants and experimenters needed either a laptop computer or tablet equipped with a built-in or external camera, speakers, and microphone. Technology was available to be provided to the participants, but all participants preferred using their personal equipment. Experimenters also used their personal technology. The confederate caregiver used a personal iPad® tablet with a stand during sessions.

Across all sessions, the participant coached the confederate caregiver to implement either DTT or a multiple stimuli without replacement (MSWO) preference assessment. Session-specific materials were used by the confederate caregiver and child such as counting manipulatives and flashcards for DTT sessions and a variety of the child’s toys during the preference assessment.

Measures

Our primary dependent variable was the percentage of correctly implemented caregiver coaching steps (see Table 1). The dependent variable included 15 steps which remained consistent across all sessions. The 15 steps were identified using information from both Shuler and Carroll (2019) and Fallon et al., (2015). We recorded all data via direct observation (via video conferencing) either live during the caregiver coaching session or via a recording of the session. Each step was recorded as correct if the participant engaged in the behavior throughout the session and incorrect if they did not. Because the participant was providing coaching to the confederate caregiver, they collected data on the caregiver’s implementation of the procedures (Table 2) and the confederate child’s responding. The experimenter collected these data simultaneously to calculate interobserver agreement. Two of the steps on the caregiver coaching data sheet specified that the participant collected data with 80% or greater agreement with the experimenter for the confederate caregiver behavior and the child behavior. Therefore, during each session, the participant collected data on two data sheets (one for the confederate caregiver and one for the confederate child) and the experimenter collected data on three data sheets (one for the participant, one for the confederate caregiver and one for the confederate child).

Prior to the beginning of the study, the first author conducted data collection training using written directions and role-play activities with the third and fourth authors. These training continued until data collectors had an acceptable percentage of inter-rater reliability (i.e., 80%). During these role-play activities, the second author served as the confederate caregiver and the third and fourth authors practiced collecting data on one another, the confederate caregiver, and the child.

To assess interobserver agreement (IOA), a second experimenter independently collected data for each participant for a minimum of 33% of sessions across all phases. An agreement was scored if both experimenters indicated the participant correctly or incorrectly completed a step; a disagreement was scored if any scoring for a step differed between observers. The number of steps with agreements was divided by the total number of steps and then multiplied by 100 to convert the number into a percentage. IOA results are presented in Table 3.

Treatment Fidelity

To evaluate the fidelity of implementation of the independent variable (i.e., experimenter’s delivery of delayed performance feedback to participants), a second experimenter observed which steps the experimenter delivered correctly. These steps included providing the participants with all the necessary materials, collecting data, providing feedback noting correct and incorrect responses, and providing opportunities for role-play and asking questions. Across all participants, there were seven steps during baseline for experimenter fidelity and 12 steps during intervention for experimenter fidelity. The fidelity of implementation was calculated by dividing the number of steps of delayed performance feedback delivered correctly by all steps and then multiplied by 100 to obtain a percentage. The percent of sessions in which fidelity was measured along with treatment fidelity results are also presented in Table 3.

Experimental Design

Two concurrent multiple baseline designs across participants (Kennedy, 2005) were used to evaluate the efficacy of the delayed performance feedback on participants’ delivery of caregiver coaching. We describe performance feedback as delayed because it occurred more than 60 s after the target behavior (Sleiman et al., 2020). We used one multiple baseline design to evaluate the effectiveness of remote delayed performance feedback on participants’ coaching caregivers to implement DTT and a second to evaluate participants’ coaching caregivers to implement an MSWO preference assessment.

Procedures

General

Sessions consisted of the participant coaching the confederate caregiver to implement five DTT trials or one MSWO preference assessment with five items. Sessions ranged from 10 to 20 min in duration. We conducted one session per day across one to two days per week for all participants. The frequency of sessions remained consistent across baseline and treatment.

We randomly assigned four participants to coach the confederate caregiver to implement DTT and three participants to coach the confederate caregiver to implement an MSWO preference assessment. For DTT sessions, each participant coached the confederate caregiver to implement DTT to target a unique goal. See Table 4 for assignments.

Prior to the first session, we informed participants of which procedure they would coach the confederate caregiver to implement. At the beginning of every session, the experimenter provided the participants with three items (a) a treatment fidelity data sheet for the assigned procedure (i.e., DTT or MSWO preference assessment) for which the participant could use to measure the confederate caregiver’s correct implementation, (b) written, lay-term instructions of the assigned procedure the participant could share with the confederate caregiver, and (c) a data collection form for child behavior for which the participant could use to collect data on the child’s correct and incorrect responding. However, we did not provide any instructions to collect data or share lay-term instructions with the caregiver until delayed performance feedback was delivered during the intervention condition.

The second author served as a confederate caregiver, conducting DTT and preference assessments with her son. The confederate caregiver was a faculty member in the master’s program in which all participants were enrolled but had not served as an instructor for any of the participants’ courses. The use of a confederate caregiver allowed for control of the frequency of errors made during sessions, thus controlling the number of opportunities for the participant to praise correct implementation and correct errors. We separated programmed errors into those that were errors of commission and errors of omission. Programmed errors during DTT included (a) the wrong materials were present (commission), (b) failing to solicit attention prior to delivering the instruction (omission), (c) providing an incorrect instruction (commission), (d) prompting early (commission), (e) providing the incorrect prompt (commission), (f) incorrect implementation of error correction (commission), (g) failing to provide praise contingent upon the child’s correct response (omission), (h) failing to provide access to preferred items contingent upon the child’s correct response (omission), (i) praising an incorrect response (commission), and (j) failing to initiate the next trial (omission). Programmed errors during preference assessments included (a) failing to place toys correctly in front of child (omission), (b) providing an incorrect instruction (commission), (c) allowing the child to select multiple items at once (commission), (d) failing to remove nonselected items (omission), (e) failing to rearrange the items (omission), (f) incorrect duration of access to the selected item (commission), and (g) failing to initiate the next trial (omission).

During the first four sessions, the caregiver committed errors on approximately 30% of steps of both DTT and the MSWO preference assessment. Errors were reduced to 20% during the fifth session and again to 10% in the eighth session to reflect a natural anticipated pattern (denoted by asterisks in Figs. 1 and 2). That is, a caregiver would be expected to commit fewer errors after more exposure to caregiver coaching sessions. A systematic decrease in errors has been used in prior research employing a confederate learner (e.g., Gerencser et al., 2017). Errors were randomly assigned across the steps of both procedures.

Baseline

During baseline sessions, the experimenter provided no remote delayed performance feedback to the participants regarding their caregiver coaching performance with the confederate caregiver and child. Baseline sessions continued until the participant indicated the session was complete. That is, we did not artificially limit the length of the session, rather the participant ended the session when they believed the preference assessment or 5 DTT trials were complete. We provided participants with data sheets for child responding and caregiver treatment fidelity and written caregiver instructions.

Intervention

During intervention, experimenters informed participants they could ask questions prior to implementing caregiver coaching sessions and the experimenter delivered remote delayed performance feedback immediately after the confederate caregiver coaching session. Immediately after the session, the confederate caregiver was dismissed, and the experimenter and participant remained in the videoconference meeting to deliver remote delayed performance feedback. During this time, the experimenter presented the data she collected regarding the steps of caregiver coaching implemented correctly and incorrectly using the screen share function in Zoom. The experimenter then (a) praised each step the participant implemented correctly, (b) described the participants’ errors, (c) provided a rationale as to why those errors need to be corrected, (d) assisted in problem-solving by offering instructions of how to improve performance, (e) provided the opportunity for the participant to practice implementing that step correctly via role-play, and (f) provided opportunities for the participant to ask questions. For example, if the participant only provided three praise statements during the session, the experimenter praised the participant for providing three praise statements, but also reminded them to praise once during each trial to ensure they provided at least five praise statements. Or if the participant did not provide the caregiver with an opportunity to ask questions, the experimenter would provide feedback regarding the importance of soliciting questions and provide the participant with the opportunity to practice soliciting this information.

Role-play during delayed performance feedback involved the experimenter serving as a mock confederate caregiver while the participant practiced the steps they missed or could improve upon to receive further feedback. For example, the participant might practice providing a rationale for why the child should only select one toy for the experimenter who was serving as the mock caregiver. We defined rationale as any explanation provided regarding why correct implementation of the procedures was important, that aligned with the principles of behavior analysis, and was communicated using verbal behavior appropriate for the intended audience (i.e., a caregiver). For example, if the participant provided feedback that the confederate caregiver did not secure the child’s attention prior to presenting the instruction, the participant also needed to explain that securing the child’s attention before presenting the instruction is important because it is an indication or clue that the child is listening to the instruction and therefore is more likely to respond. If the explanation was inaccurate (e.g., securing attention is required but not important) or used language that was not appropriate to the audience this was not scored as providing a rationale. Our mastery criterion for caregiver coaching was defined as the participant implementing caregiver coaching with 85% fidelity across three consecutive sessions. This mastery criterion was selected based on a prior review that reported the majority of studies incorporated mastery criteria of 80–90% fidelity of implementation (Neely et al., 2017).

Social Validity

After meeting mastery criterion, participants were asked to complete an eight-question survey regarding remote delayed performance feedback. For the first seven questions, participants responded to statements regarding remote delayed performance feedback using a five-point Likert-type scale with 1 indicating strong disagreement with the statement, 2 indicating disagreement with the statement, 3 indicating a neutral response to the statement, 4 indicating agreement with the statement, and 5 indicating strong agreement with the statement. The specific statements are listed in Table 5. The final question asked participants to rank a preference for remote versus in-person performance feedback. All participants had received in-person performance feedback outside of participating in this study.

Results

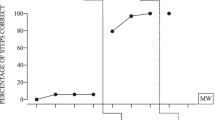

The results of remote supervision on participants’ correct coaching of a confederate caregiver to conduct DTT is presented in Fig. 1. All four participants conducted few caregiver coaching steps correctly during baseline. Sandra’s correct implementation of caregiver coaching at baseline was low with a mean of 28% of steps implemented correctly (range = 20–43%) and data demonstrated a decreasing trend. During intervention, the trend increases, stabilizing at a high level in the final three data points with little variability across the phase (M = 75%, range = 20–100%). Sandra met mastery criterion within five remote supervision sessions. Meagan’s correct implementation of caregiver coaching at baseline was also at a low and stable level with a mean of 17% of steps implemented correctly (range = 7–27%). There is very little variability in Meagan’s baseline data, but there is a short increasing trend followed by a decreasing trend just prior to intervention. During intervention, there was a sizeable change in level beginning with the second intervention session. Data were mostly stable with a very slight increasing trend. During intervention, Meagan implemented a mean of 77% (range = 13–100%) of caregiver coaching steps correctly. Meagan met mastery criterion within five sessions. During baseline, Jamie’s correct implementation of caregiver coaching had an initial decreasing trend, becoming stable in the final baseline sessions with a mean of 19% of steps implemented correctly (range = 13–43%). There was an immediate effect during intervention, with a considerable increase in level and an increasing trend. During intervention, Jamie implemented a mean of 86% (range = 60–100%) of caregiver coaching steps correctly. Jamie met mastery criterion in four remote supervision sessions. Finally, during baseline Heather’s correct implementation of caregiver coaching was low with some slight variability and a mean of 26% of steps implemented correctly (range = 20–33%). There was substantial increase in level during intervention to a mean of 77% (range = 40–93%). Her intervention data have little variability and a slight increasing trend. Heather met mastery criterion within four sessions.

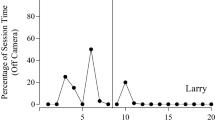

The results of remote supervision on participants’ correct coaching of a confederate caregiver to conduct an MSWO preference assessment is presented in Fig. 2. During baseline, Sam’s level of correct implementation of caregiver coaching was low, with very little variability and a very slight increasing trend in the final data points. During baseline, Sam conducted a mean of 16% of caregiver coaching steps correctly (range = 13–20%). During intervention, the level increased considerably to a mean of 77% (range = 27–100%). Initially, the data were variable with an increasing trend but stabilized in the fifth session. Sam met mastery criterion after seven remote supervision sessions. During baseline, Tamera’s data were at a very low level with no variability and no trend. Tamera conducted a mean of 7% of steps correctly. During intervention, the data first presented a sharp increasing trend, stabilizing during the third intervention session. There was a substantial increase in level and no variability within the data. During intervention, Tamera implemented a mean of 66% (range = 7–93%) of caregiver coaching steps correctly. Tamera met the mastery criterion within five sessions. During baseline, Angela’s data were low with an initial slight increasing trend followed by a decreasing trend. During baseline, Angela conducted a mean of 40% of steps correctly (range = 31–47%). During intervention, we observed an increasing trend that stabilized during the final sessions with a sizeable increase in level to a mean of 79% (range = 27–100%). Angela met mastery criterion within six remote supervision sessions.

It is important to note that across six of seven participants, an immediate and sizable increase in implementation fidelity was not observed during the first intervention session; rather, such an increase was observed during the second intervention session. This is attributed to the fact that participants had yet to receive performance feedback when they implemented caregiver coaching during the first intervention session. Delayed performance feedback was delivered immediately after caregiver coaching; therefore, we would expect this performance feedback to improve the fidelity of caregiver coaching implemented in the second intervention session. The only distinction between baseline and intervention sessions to take place prior to the participants’ implementation of caregiver coaching was the opportunity to ask questions during the intervention phase. In other words, had a participant asked for guidance prior to implementing caregiver coaching during the intervention phase, such guidance would have been provided and likely would have influenced the subsequent implementation of caregiver coaching. However, only one participant asked questions prior to implementing caregiver coaching during the first intervention session. In fact, across all intervention sessions, participants rarely took advantage of the opportunity to ask questions prior to implementing caregiver coaching.

In contrast, participants did ask a variety of questions during the post-session feedback. The participants providing feedback on DTT implementation asked roughly two to four questions per session, whereas participants providing feedback on MSWO implementation asked roughly one question per session. The majority of these questions were related to the timing and consistency of correcting caregiver errors. For example, Angela asked what the best time was to provide correction and Meagan asked how many times during a session she should provide corrective feedback. There were also questions related to an appropriate duration for providing feedback to the confederate caregiver. We observed an increase in correct responding following delayed feedback sessions in which Meagan and Heather asked nine and four questions respectively. We also observed an increase in correct responding following back-to-back delayed feedback sessions in which Sandra and Jamie asked two and four/five questions respectively.

We documented the number of questions asked and the duration of performance feedback for the sessions for which we had access to recordings (80%). On average participants asked 1.7 questions per feedback session. For participants who coached the caregiver to implement DTT, the average number of questions posed was 1.4 for Sandra, 4 for Meagan, 3.3 for Jamie, and 1.6 for Heather. For participants who coached the caregiver to implement an MSWO preference assessment, the average number of questions posed was 0.2 for Sam, 0.5 for Tamera, and 0.66 for Angela.

Across the participants, the experimenters provided performance feedback for an average of 9 min. We did not provide feedback during baseline; thus, these data are from intervention sessions only. For participants who coached the caregiver to implement DTT, the average feedback duration rounded minutes was 7 min for Sandra, 15 min for Meagan, 11 min for Jamie, and 7 min for Heather. For participants who coached the caregiver to implement an MSWO preference assessment, the average feedback duration rounded the minutes was 7 min for Sam, 10 min for Tamera, and 8 min for Angela.

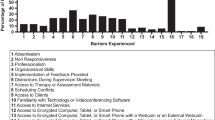

In order to graphically display data related to errors, we collapsed the errors into six categories including pre-session, during session, data collection, BST instructions, BST modeling and role-play, and BST feedback (see Table 1). After calculating the total number of errors, we found that during baseline participants engaged in 346 errors, during intervention participants engaged in 127 errors, for a total of 473 errors. Overall, the most common errors committed by participants across sessions were in the categories of feedback and modeling/role-play (Fig. 3). Of the 346 errors made during baseline, the most common errors committed by participants were in the categories of feedback and presession. Of the 127 errors made during intervention, the most common errors committed by participants were in the categories of feedback and modeling/role-play.

The top graph displays the percent of participant errors made across all sessions (473 total errors). The middle graph displays the percent of participant errors made across baseline sessions (346 baseline errors). The bottom graph displays the percent of participant errors made across intervention sessions (127 intervention errors)

The results of the social validity evaluation are presented in Table 5. A score of 4.0 indicated agreement with positive statements, and a 5.0 indicated strong agreement. Across all seven questions, participant mean responses indicated an agreement to strong agreement with positive statements about remote supervision, with means ranging from 4.1 to 4.7 across statements. When asked to indicate preference for in-person versus remote performance feedback, two participants reported no preference, four participants reported a preference for in-person performance feedback, and a final participant reported a strong preference for in-person performance feedback.

Discussion

In the current study, we sought to evaluate the effectiveness and social validity of remote delayed performance feedback provided to behavior analysis trainees implementing caregiver coaching. The results of this study indicate that delayed performance feedback provided remotely can be used to increase accuracy with caregiver coaching. Moreover, participants met mastery criterion within an average of five remote supervision sessions. Feedback sessions were on average 9 min and ranged from 4 to 25 min. Therefore, the overall time required of the supervisor was relatively short and allowed for supervisors to provide supervision to four supervisees within an hour and a half block of time.

The efficiency of supervision is not the only benefit of remote supervision. Access to quality supervision across geographic locations (e.g., rural populations, populations with limited BCBAs®) can be increased with the implementation of remote supervision and performance feedback. This increased access opens opportunities for individuals to seek certification as a BCBA®, regardless of access to BCBA® supervisors in their geographic regions. It also allows for continuity of a supervisory relationship if either the supervisor or supervisee travels or moves during the field experience. During the course of this study, many participants traveled to their hometowns as the study aligned with a break between university semesters. This travel in no way hindered our ability to provide continuous supervision via remote delayed performance feedback. Moreover, the technology necessary to provide remote supervision and feedback is readily available. In fact, all participants and experimenters in this study used their personal technology and no technology-related issues precluded the delivery of delayed performance feedback across any sessions. Although not directly evaluated within this study, it is possible to use the Zoom application on smartphones which would allow for even greater access to remote services for those who do not own tablets or laptop computers.

Within this study, we provided feedback following the completion of the caregiver coaching session, which according to Sleiman et al., (2020) is considered delayed feedback (i.e., feedback provided more than 60 s after the target response). Although Sleiman et al., found that immediate feedback was more effective than delayed feedback, our results align with those of Zhu et al., (2020) which demonstrate that delayed feedback resulted in positive changes in the target behavior. We determined that delayed feedback would be most appropriate because interrupting a therapist who is providing caregiver coaching could result in increased confusion for the caregiver and/or decreased caregiver confidence in the therapist. Therefore, BCBAs® providing remote supervision may consider delayed feedback as an option for situations in which immediate feedback is not ideal.

Prior research on performance feedback has included performance feedback as part of an intervention package with other intervention components such as goal setting or contingent reinforcement (Alvero et al., 2001; Balcazar et al., 1985). Although these intervention packages were shown to be effective, both Sleiman et al., (2020) and Zhu et al., (2020) provide evidence of the effectiveness of performance feedback alone for increasing target responding. In addition, Roscoe et al., (2006) demonstrated that performance feedback alone was more effective than contingent reinforcement alone for increasing fidelity of implementation. They hypothesized that for individuals who are already highly motivated to implement procedures with fidelity, performance feedback alone may be sufficient to change behavior. We also found that performance feedback alone resulted in meaningful behavior change for behavior analysis trainees. It is likely that these trainees were sufficiently motivated to master the target skills.

Some additional interesting findings from this study are related to the questions posed by the participants and the common errors committed by the participants. We observed an increase in correctly implemented caregiver coaching steps for DTT following feedback sessions in which participants asked multiple questions. We did not identify any research studies specifically evaluating the impact of trainee-initiated questions on the effectiveness of performance feedback. However, it is possible that a trainee’s motivation to master the target skill influences the frequency with which they seek additional information by asking questions. Research outside of the field of behavior analysis suggests that asking questions in college classes is an indicator of student motivation (Aitken & Neer, 1993). Future researchers might evaluate whether participants who pose questions when receiving performance feedback perform better than those who do not. If the results of research suggest that posing questions does result in better performance, evaluations of how to contrive motivation within training to occasion trainee-initiated question asking could provide important information for supervisors. We acknowledge that it is possible that the way in which we implemented performance feedback by specifically recruiting questions may have artificially increased question asking. Thus, question asking may have been impacted by the intervention as opposed to question asking having an impact on the effectiveness of the intervention. Future researchers should specifically manipulate opportunities for asking questions to empirically isolate these variables.

The frequency of caregiver coaching errors decreased following the introduction of performance feedback across all categories and individual steps (e.g., solicits question from the caregiver). We found that the category of feedback had the highest percentage of errors for baseline and intervention. The most common errors within this category included failing to correct all errors made by the caregiver and failing to provide a rationale for correcting errors. It is likely that the high standard for correct responding within this category may have resulted in frequent errors. That is, there were multiple caregiver errors to correct during each session and the participant had to correct 100% of them in order for this step to be marked as correct. Therefore, the participant had more opportunities to engage in the response, but the additional opportunities also meant there were more opportunities to respond incorrectly. The other category with a high percentage of errors was modeling/role-play. Specifically, failing to model correct implementation was a common error across both baseline and intervention. This may have been due to the participants being reluctant to model responses for an instructor within their master’s program or perhaps video conferencing is less conducive for modeling. Despite this step continuing to be a common error for participants, the frequency of this particular error across participants decreased from a total of 30 instances during baseline to 18 instances during treatment.

In regard to the social validity of these procedures, six of the seven participants agreed or strongly agreed with statements that remote supervision was helpful, enjoyable, efficient, and likely to result in improvements in their skills as a therapist. One participant reported an oppositive evaluation of remote supervision. Although participants rated remote delayed performance feedback favorably, five out of seven indicated a preference for in-person, versus remote delayed performance feedback, and the remaining two indicated no preference among the two options. These results align with those from Simmons et al. (2021) in which participants reported a preference for in-person supervision but were satisfied with remote supervision.

It is important to consider that this study was conducted about one year into the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused many daily activities that previously took place in person to shift to online. For example, all participants in this study applied to an in-person master’s program, but due to the pandemic, took many courses online across the school year. Similarly, many of their supervised field experiences outside of this study were shifted to online experiences due to the pandemic. A preference for in-person performance feedback may be, in part, due to fatigue associated with a significant portion of daily activities shifted to online format. Moreover, this particular subset of participants had a history of choosing in-person activities (i.e., in-person graduate program) over online activities (i.e., online graduate program); therefore, they may represent a group of individuals with a general preference for in-person activities. However, when necessary and/or when preferred, remote delayed performance feedback may be a viable and effective option for providing quality supervision.

There are some limitations of this study to consider. First, we used a confederate caregiver to control for error rate and type in baseline and intervention. We believe this was an ethical decision as parents of children with intellectual or developmental disabilities were not exposed to incorrect teaching procedures during baseline. However, this arrangement precludes the determination that remote supervision would have resulted in similar improvements in caregiver coaching with a real caregiver. Another limitation related to using a confederate caregiver was the inclusion of a learner who was a typically developing 3-year-old child. Although all the selected target skills were initially unknown to the child, he was able to master them without extensive teaching trials. This may not have provided an accurate simulation of working with a client with a developmental disability. However, the authenticity of providing feedback to a caregiver interacting with their own child was an important aspect of the study. Future researchers should explore the effectiveness of remote supervision when working with caregivers of children with intellectual or developmental disabilities.

Another limitation is our lack of treatment fidelity data on the confederate caregiver’s engagement in target errors (e.g., failing to secure child attention). Prior to each session, the confederate caregiver and experimenter reviewed the errors to be made for that session. Although we did not directly collect data on the programmed errors, the second author and had over 15 years of experience with implementing DTT procedures and committing the target errors did not present a challenge. Related to the confederate caregiver errors, we recognize that our decision to systematically reduce the number of errors made by the confederate caregiver may have impacted our results. We decided to reduce the errors in this fashion because we wanted to simulate a real-life scenario in which a caregiver’s treatment fidelity would improve over time. We believe that it is unlikely that this decision meaningfully impacted the participants’ percentage of correct caregiver coaching because the components related to error correction were scored with an overall score of correct or incorrect. That is if the confederate caregiver engaged in five errors and the participant corrected four of the errors, this component was marked as incorrect because the participant did not correct all of the errors. There were no sessions in which the confederate caregiver did not make any errors. We do not have data to suggest that by the end of the study each participant could accurately identify 100% of caregiver errors as specific errors (e.g., failing to secure attention) were not consistently presented. That is, if the participant did not correct the caregiver’s failure to secure attention during one session, the caregiver engaging in this specific error in another session would be necessary to determine whether the participant would correct this error in the future. We did not record this level of detail within data collection, nor did we control presentation of specific errors in this manner. Future researchers should consider collecting data that may be more sensitive to the presentation of specific errors. A final limitation is the fact that during the study the participants were more than halfway through their master’s program. It is possible that these procedures may have been less effective with participants at the beginning of their program of study.

In conclusion, we found that delayed performance feedback delivered remotely improved caregiver coaching for seven master’s students. While a growing body of evidence supports telehealth to train others to implement evidence-based educational practices (Neely et al., 2017), this study is a first to specifically evaluate remote delayed performance feedback among individuals completing supervised field experience toward earning a BCBA® credential. Overall, this study provides encouraging evidence of the effectiveness of remote supervision in increasing caregiver coaching. In addition, participants reported satisfaction with the procedures suggesting further research on these procedures is warranted.

References

Aitken, J. E., & Neer, M. R. (1993). College student question-asking: The relationship of classroom communication apprehension and motivation. Southern Communication Journal, 59(1), 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10417949309372923

Alvero, A. M., Bucklin, B. R., & Austin, J. (2001). An objective review of the effectiveness and essential characteristics of performance feedback in organizational settings. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 21(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1300/J075v21n01_02

Balcazar, F., Hopkins, B. L., & Suarez, Y. (1985). A critical, objective review of performance feedback. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 7(3–4), 65–89. https://doi.org/10.1300/j075v07n03_05

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2021). BACB certificant data, Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/BACB-certificant-data.

Behavior Analysis Certification Board. (2022). Board certified behavior analyst handbook, https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2022a/01/BCBAHandbook_220110.pdf

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2022). Ethics code for behavior analysts, https://bacb.com/wp-content/ethics-code-for-behavior-analysts/

Carroll, R., Kodak, T., & Fisher, W. (2013). An evaluation of programmed treatment-integrity errors during discrete-trial instruction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46(2), 379–394. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.49

Chipchase, L., Hill, A., Dunwoodie, R., Allen, S., Kane, Y., Piper, K., & Russell, T. (2014). Evaluating telesupervision as a support for clinical learning: An action research project. International Journal of Practice-Based Learning in Health and Social Care, 2(2), 40–53. https://doi.org/10.11120/pblh.2014.00033

Deochand, N., & Fuqua, R. W. (2016). BACB certification trends: State of the states (1999 to 2014). Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(3), 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0118-z

DiGennaro-Reed, F., Reed, D., Baez, C., & Maguire, H. (2011). A parametric analysis of errors of commission during discrete-trial training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44(3), 611–615. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2011.44-611

Eikeseth, S., Hayward, D., Gale, C., Gitlesen, J., & Eldevek, S. (2009). Intensity of supervision and outcome for preschool aged children receiving early and intensive behavioral interventions: A preliminary study. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(1), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2008.04.003

Fallon, L. M., Collier-Meek, M., Maggin, D. M., Sanetti, L. M. H., & Johnson, A. H. (2015). Is performance feedback for educators an evidence-based practice? A systematic review and evaluation based on single-case research. Exceptional Children, 81(2), 227–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402914551738

Fryling, M., Wallace, M., & Yassine, J. (2012). Impact of treatment integrity on intervention effectiveness. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(2), 449–453. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2012.45-449

Gerencser, K. R., Higbee, T. S., Akers, J. S., & Contreras, B. P. (2017). An evaluation of an interactive computer training to teach parents to implement a photographic activity schedule. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 50(3), 567–581. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.386

Gerow, S., Radhakrishnan, S., Akers, J. S., McGinnis, K., & Swensson, R. (2021). Telehealth parent coaching to improve daily living skills for children with ASD. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 54(2), 566–581. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.813

Katzman, J. G. (2013). Making connections: Using telehealth to improve the diagnosis and treatment of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, an underrecognized neuroinflammatory disorder. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology : THe Official Journal of the Society on NeuroImmune Pharmacology, 8(3), 489–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11481-012-9408-6

Kennedy, C. H. (2005). Single-case designs for educational research. Allyn & Bacon.

Lerman, D. C., O’Brien, M. J., Neely, L., Call, N. A., Tsami, L., Schieltz, K. M., Berg, W. K., Graber, J., Huang, P., Kopelman, T., & Cooper-Brown, L. J. (2020). Remote coaching of caregivers via telehealth: Challenges and potential solutions. Journal of Behavioral Education, 29(2), 195–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-020-09378-2

Lindgren, S., Wacker, D., Schieltz, K., Suess, A., Pelzel, K., Kopelman, T., Lee, J., Romani, P., & O’Brien, M. (2020). A randomized controlled trial of functional communication training via telehealth for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(12), 4449–4462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04451-1

Machalicek, W., Lequia, J., Pinkelman, S., Knowles, C., Raulston, T., Davis, T., & Alresheed, F. (2016). Behavioral telehealth consultation with families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Behavioral Interventions, 31, 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1450

Mangiapanello, K. A., & Hemmes, N. S. (2015). An analysis of feedback from a behavior analytic perspective. The Behavior Analyst, 38(1), 51–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-014-0026-x

Minor, L., Dubard, M., & Luiselli, J. K. (2014). Improving intervention integrity of direct-service practitioners through performance feedback and problem-solving consultation. Behavioral Interventions, 29(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1382

Neely, L., Rispoli, M., Gerow, S., Hong, E., & Hagan-Burke, S. (2017). Fidelity outcomes for autism-focused interventionists coached via telepractice: A systematic literature review. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 29(6), 849–874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-017-9550-4

Perepletchikova, F., Treat, T., & Kazdin, A. (2007). Treatment integrity in psychotherapy research: Analysis of the studies and examination of the associated factors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(6), 829–841. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.829

Roscoe, E., Fisher, W., Glover, A., & Volkert, V. (2006). Evaluating the relative effects of feedback and contingent money for staff training of stimulus preference assessments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 39(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2006.7-05

Sellers, T. P., Valentino, A. L., Landon, T. J., & Aiello, S. (2019). Board certified behavior analysts’ supervisory practices of trainees: Survey results and recommendations. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12(3), 536–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-019-00367-0

Shuler, N., & Carroll, R. A. (2019). Training supervisors to provide performance feedback using video modeling with voiceover instructions. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12(3), 576–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-018-00314-5

Simmons, C. A., Ford, K. R., Salvatore, G. L., & Moretti, A. E. (2021). Acceptability and feasibility of virtual behavior analysis supervision. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1–17. Advance online publication. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00622-3

Sleiman, A. A., Sigurjonsdottir, S., Elnes, A., Gage, N. A., & Gravina, N. E. (2020). A quantitative review of performance feedback in organizational settings (1998–2018). Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 40(3–4), 303–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/01608061.2020.1823300

Suess, A. N., Romani, P., Wacker, D., Dyson, S., Kuhle, J., Lee, J., Lindgren, S., Kopelman, T., Pelzel, K., & Waldron, D. (2014). Evaluating the treatment fidelity of parents who conduct in-home functional communication training with coaching via telehealth. Journal of Behavioral Education, 23(1), 34–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-013-9183-3

Tsami, L., Lerman, D., & Toper-Korkmaz, O. (2019). Effectiveness and acceptability of parent training via telehealth among families around the world. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52(4), 1113–1129. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.645

Wacker, D. P., Lee, J. F., Padilla Dalmau, Y. C., Kopelman, T. G., Lindgren, S. D., Kuhle, J., & Waldron, D. B. (2013). Conducting functional analyses of problem behavior via telehealth. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.29

Waltz, J., Addis, M. E., Koerner, K., & Jacobson, N. S. (1993). Testing the integrity of a psychotherapy protocol: Assessment of adherence and competence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 620–630. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.61.4.620

Warrilow, G. D., Johnson, D. A., & Eagle, L. M. (2020). The effects of feedback modality on performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 40(3–4), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/01608061.2020.1784351

Wilder, D., Atwell, J., & Wine, B. (2006). The effects of varying levels of treatment integrity on child compliance during treatment with a three-step prompting procedure. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 39(3), 369–373. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2006.144-05

Zawacki, J., Satriale, G., & Zane, T. (2018). The use of remote monitoring to increase staff fidelity of protocol implementation when working with adults with autism. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 43(4), 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540796918810234

Zhu, J., Hua, Y., & Yuan, C. (2020). Effects of remote performance feedback on procedural integrity of early intensive behavioral intervention programs in china. Journal of Behavioral Education, 29(2), 339–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-020-09380-8

Funding

This study was funded by Baylor University academy of teaching and learning.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, drafted the work, approved the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Baylor University. The procedures used in the study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Akers, J.S., Davis, T.N., McGinnis, K. et al. Effectiveness of Remote Delayed Performance Feedback on Accurate Implementation of Caregiver Coaching. J Behav Educ (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-022-09487-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-022-09487-0