Abstract

The Child Problematic Traits Inventory (CPTI) enables the assessment of psychopathy dimensions as early as age three. The current study employs a multi-informant approach (i.e., fathers, mothers, and teachers) to further investigate the unique associations between psychopathy dimensions, as measured by the CPTI, with theoretically relevant constructs of interest, such as conduct problems, oppositionality, empathy, and social relations, in early childhood (N = 1283, M age = 6.35). Although associations with conduct, aggressive, and oppositional behaviours differed in strength, our findings supported the importance of all psychopathy dimensions in predicting behavioral problems. Our findings also suggested a unique association of the callous-unemotional dimension with affective empathy. Furthermore, stronger associations were identified between the callous-unemotional and impulsive need for stimulation dimensions with social problems (e.g., peer and family relations) compared to the grandiose-deceitful dimension. Current findings can inform prevention and intervention efforts aiming to alter the development of psychopathic traits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adult psychopathic personality is a multidimensional syndrome consisting of a constellation of co-occurring interpersonal, affective, and behavioral traits, such as a sense of superiority, lack of remorse, and impulsivity (e.g., Fanti et al., 2018; Patrick et al., 2009). Increased research interest in understanding this construct’s etiology, developmental trajectory, and stability has led to the downward extension of psychopathy in childhood. In addition, their consistent associations with aggressive behavior (e.g., Kimonis et al., 2006), conduct problems (e.g., Frick et al., 2000), and delinquency (e.g., Marsee et al., 2005) have supported the importance of assessing the three-factor structure of psychopathy in childhood and adolescence (Salekin, 2017).

This evidence has led researchers to describe psychopathic personality as a developmental phenomenon rooted in early childhood (Frick et al., 2014), stressing the need for a more accurate assessment of these traits early in development. The Child Problematic Traits Inventory (CPTI) was developed to assess psychopathic traits as early as age three (Colins et al., 2014). Specifically, the CPTI was based on the three-factor conceptualization of psychopathic personality and includes an interpersonal (labeled: Grandiose-Deceitful; GD), an affective (labeled: Callous-Unemotional; CU), and a behavioral (labeled: Impulsive-Need for Stimulation; INS) dimension. Prior work with both teacher and parent ratings has suggested that the CPTI enables a reliable and valid assessment of psychopathic traits that can be measured early in development, linking psychopathy to theoretically important temperamental dimensions and aggressive behavior (e.g., Colins et al., 2014; López-Romero et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). Aiming to extend the literature on the CPTI as well as the early assessment of psychopathy (e.g., Lopez-Romero et al., 2022), the current study was designed to replicate prior work by examining associations with behavioral, aggressive, and oppositional problems. In addition, we extend prior findings by examining associations between the three psychopathy dimensions with individual and contextual variables that may shape childhood development, such as empathic deficits, peer problems, and parenting practices (Colins et al., 2022).

Externalizing Problems

Psychopathic traits assessed early in development are related to several externalizing difficulties such as conduct problems, antisocial, oppositional defiant, and aggressive behaviors (e.g., DeLisi, 2009; Frick et al., 2014). Prior research examining the role of psychopathic traits in the development of externalizing problems has mainly focused on the CU or affective dimension of psychopathy (e.g., Fanti et al., 2013;, 2018; Kimonis et al., 2016). This line of work has supported that antisocial children and adolescents characterized by CU traits are at high risk for severe and stable behavioral problems (e.g., Andershed et al., 2018; Frick et al., 2014). In addition, Colins et al. (2020) have shown that CU traits in childhood predicted oppositional behavior and conduct problems a year later after controlling for baseline conduct problems.

Notwithstanding the significant progress in the study of externalizing problems and CU traits, mounting research findings support the importance of interpersonal and behavioral dimensions in predicting conduct problems, aggression, and delinquency (Frick & White, 2008; Lopez-Romero et al., 2022; Salekin & Andershed, 2022). The behavioral dimension of psychopathy, which refers to impulsivity, need for stimulation, sensation seeking, and proneness to boredom, has a vital role in explaining severe antisocial behavior (Fanti et al., 2018; Fronger et al., 2018). Importantly, Mathias et al. (2007) found that impulsiveness is a risk factor for conduct disorder symptoms early in development. Further, the interpersonal dimension of psychopathy, consisting of grandiosity and deceitfulness, has proven to be an indicator of aggressive behavior, bullying, and conduct disorder symptoms (e.g., Fanti et al., 2018; Fanti and Henrich, 2015; López-Romero et al., 2018). In addition, the interpersonal dimension was more strongly related to relational aggression than the CU dimension (Lau & Marsee, 2013). However, a limited number of studies have investigated the unique associations of the three psychopathy dimensions with overt and relational aggression, which is an aim of the current study.

The Distinction Between Affective and Cognitive Empathy

Empathy dysfunction is closely related with the psychopathy construct (Blair, 2007; Dadds et al., 2009), although there are some contradictions regarding associations with cognitive and affective components of empathy. Cognitive empathy refers to an individual’s ability to understand the affective state of others, while affective empathy is described as the ability to respond and resonate with others’ emotional states (e.g., Georgiou et al., 2019b; Walter, 2012). Agreeing with existing theories (Blair, 2007; Frick et al., 2014; Waller et al., 2020), individuals high on CU traits are more likely to show deficits in affective empathy (Georgiou et al., 2019a) and are less likely to sympathize with the victims of violence (Fanti et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2010). Additional work suggested that CU traits are negatively associated with both affective and cognitive empathy (Georgiou et al., 2019b). Agreeing with these findings, substantial empirical research indicated a negative association between CU traits and the ability to identify and understand others’ emotions, which describe cognitive empathy (e.g., Blair et al., 2001; Dadds et al., 2008a). Moreover, research suggested a deficit of children high on CU traits in recognizing and reacting to emotions such as fear and sadness, which is attributed to deficits in emotional processing as well as the ability to “see others perspective” (Blair et al., 2001; Dadds et al., 2008a; Demetriou & Fanti, 2022; Fanti et al., 2017).

Despite the research emphasis on the relation between CU traits and empathy deficits in childhood and adolescence (e.g., Jones et al., 2010; Waller et al., 2020), research in adult populations has also considered impaired empathic processing as a core feature of the interpersonal dimension of psychopathy (Baskin-Sommers et al., 2014). This line of research suggests that greater emotional understanding enhances the expression of dishonest and deceitful behaviors of narcissistic individuals, which enables them to manipulate others in order to satisfy their personal needs and their exaggerated sense of self (Ritter et al., 2011). Indeed, prior work supported a positive correlation between grandiosity and cognitive empathy (Pajevic et al., 2018). However, additional work suggested that individuals high in the interpersonal dimension of psychopathy exhibit deficits in recognition of facial emotional expressions (Marissen et al., 2012) and show little empathic concern in emotional contexts (Ritter et al., 2011). Thus, existing findings do not offer definitive conclusions regarding the association of the interpersonal dimension of psychopathy with cognitive empathy, and it is unclear how the interpersonal dimension relates to affective empathy.

Regarding impulsivity, Almeida et al. (2015) provided findings suggesting a greater propensity of impulsive individuals to feel empathic concern (Seara-Cardoso et al., 2012). Thus, the affective and interpersonal dimensions might be differentially associated with empathy compared to impulsivity. To disentangle the unique effects of each psychopathy dimension, the current study will investigate their differential associations with affective and cognitive empathy after controlling for their co-occurrence. Examining the relationships between the three psychopathy dimensions and empathic concern can inform the development of effective prevention and intervention programs early in development.

Social Context: The Importance of Familial and Peer Relations

A prominent line of research in psychopathy has focused on the negative impact of psychopathic traits on children’s social relations with peers and family members (e.g., Fanti et al., 2017; Muñoz et al., 2008; Waller et al., 2013). Based on the emphasis given to the affective dimension of psychopathy, research has well established the relation between CU traits and parenting practices. According to Waller and colleagues (2014), children with CU traits are relatively insensitive to typical parental socialization efforts (i.e., effective discipline strategies), which might be due to their fearlessness and insensitivity to punishment or distress of others (Fanti et al., 2023a, b; Frick et al., 2014). Fearlessness and low sensitivity to punishment associated with CU traits might lead parents to adopt less effective practices, such as corporal punishment, inconsistent discipline, and poor monitoring (Barker et al., 2011; Fanti, Mavrommatis et al., 2023). Indeed, harsh and punitive discipline practices are associated with higher CU traits and conduct problems (Mills-Koonce et al., 2016; Pasalich et al., 2012). Having a child who lacks empathic concern and, at the same time, exhibits behavioral problems can be very distressing to parents (e.g., dissatisfaction with their role as a parent and in their parenting performance), and lead to negative parenting practices over time (Fite et al., 2008).

Additional work suggested that it is important to test how various psychopathy dimensions predict parenting practices early in development (e.g., Ručević et al., 2022). Although findings are limited, research in adolescent community samples also linked the interpersonal dimension of psychopathy with parental inconsistency, poor monitoring, and supervision (Mechanic & Barry, 2015; Trumpeter et al., 2008). Regarding the behavioral dimension, research supports that the failure of the environment to provide external control through consistent parental monitoring increases the risk for severe and stable delinquent behavior, as it fails to compensate for children’s deficient internal regulatory competencies (Lynam et al., 2000).

Moreover, several positive parenting practices, such as parental warmth, involvement, and care, serve as protective factors decreasing the development of conduct problems among individuals high on CU traits and impulsivity (Menting et al., 2016; Wall et al., 2016). Longitudinal research suggests that mutual positive affect and cooperation between parents and children early in life can enhance social norms’ internalization and moral development (Kochanska et al., 2005; Waller et al., 2017). Moreover, positive parenting practices and warmth can provide an appropriate behavioral model for children high on impulsivity to learn how to cope with self-control deficits (Menting et al., 2016). Furthermore, positive parenting is related to positive forms of grandiosity and increased self-esteem that enables the healthy development of social competence and social interactions (Horton et al., 2006). However, all these findings were not consistently derived from research on children populations, creating many gaps in our understanding regarding the role of the three distinct but interrelated phenotypic dimensions of psychopathy in shaping parental responses. To advance our understanding of the crucial role of family context and parental practices early in development, the current study investigated the association of all psychopathy dimensions with both positive and negative parental strategies.

In addition to familial relations, psychopathy dimensions in childhood have been related to impaired peer relations and poor peer social support (e.g., Fanti, 2013; Fanti et al., 2013). Lahey (2014) notes that individuals with CU traits are characterized by “a cold insensitivity to the feelings and needs of others” that lead to severe social functioning impairments. Mounting evidence associates CU traits with peer dislike (Piatigorsky & Hinshaw, 2004), lower perceived social competence (Barry et al., 2008), increased levels of peer impairments (Waschbusch & Willoughby, 2008), and low peer social support (Fanti, 2013). In addition, findings support that impulsive children demonstrate behavioral dysregulation that may be challenging to their social relations, as their peers may experience difficulty tolerating it (Hoza, 2007). Moreover, chilren’s impulsive reactions and rule-breaking can increase barriers in social interactions, negatively influencing social connections with peers (Andrade & Tannock, 2012). According to Kerr and colleagues (2012), manipulative traits, a characteristic of the interpersonal dimension, can also increase peer problems, leading to antisocial behaviors. It is important to understand the quality of relationships in childhood between children high on psychopathic traits and their significant others, as social relations are important for later moral and conscious development.

Current Study

Following recent research advances focusing on the assessment of psychopathy early in development, the current study aimed to investigate the unique associations of different psychopathy dimensions with externalizing problems (e.g., conduct problems, overt and relational aggression), empathic concern, and social context (e.g., peer and family relations). Using a cross-sectional multi-informant approach, we collected data from fathers, mothers, and teachers. By linking psychopathy dimensions with external constructs of interest, we aimed to enhance the understanding of this population’s behavioral and social manifestation early in development. In relation to externalizing problems, we hypothesized that all three psychopathy dimensions would be related to oppositional and conduct problems. We also aimed to explore potential differences in the association between psychopathic dimensions with overt and relational forms of aggression. Regarding empathic concern, we hypothesized that the GD and CU dimensions, but not INS, will relate to lower empathy. However, it was expected that CU traits would be more strongly associated with diminished affective empathy, in accordance with the affective nature of their difficulties and their limited prosocial emotions.

Concerning social context, it was hypothesized that all dimensions would impose increased challenges for children’s peers and parents. However, we expected our findings to provide new evidence as to how each dimension would be uniquely related to peer problems as well as positive and negative parental practices. Due to the unemotional nature of CU traits, we expected these traits to prevent the development of affective relations with parents that are based on warmth and care. In addition, CU traits were expected to impose more severe difficulties in parents’ attempts for consistent parenting, increasing levels of parental distress. The impulsivity and inability for behavioral control, related to the INS dimension, were expected to be associated with higher rates of inconsistent discipline strategies. Further, the interpersonal difficulties, shown by individuals high on the GD dimension, were expected to be related to increased difficulties in peer relationships and more harsh and inconsistent discipline parenting strategies.

Method

Participants

According to parental responses, the sample consisted of 1283 preschool and primary school children living in the Republic of Cyprus and was divided evenly between boys (n = 638) and girls (n = 645). Children’s ages ranged between 3 and 9 years (Mage = 6.35, SD = 1.31). Additionally, data were collected from 986 teachers, enabling associations between parent and teacher reports (49% girls). The sample was diverse in terms of parental educational levels: 7.4% of fathers and 4.5% of mothers did not complete high school, 32.5% of fathers and 25% of mothers had a high school education, and 49.5% of fathers and 60.9% of mothers had a university degree.

Procedure

Following approval of the study by the National Bioethics Committee and the Centre of Educational Research and Assessment (CERE) of Cyprus, Pedagogical Institute, Ministry of Education and Culture, 47 private and public nursery schools, and 69 primary schools in three provinces (Nicosia, Larnaca, and Limassol) were randomly selected for participation. Schools were contacted by phone and were informed about the study’s aims. School boards interested in participating received details about the purpose and procedure via email or fax. Parents/ guardians were informed of the nature of the study, and 81% consented to their participation. Teachers, fathers, and mothers completed a battery of questionnaires, which took approximately half an hour for teachers and an hour for each parent to complete.

Measures

Child Problematic Traits Inventory (CPTI; Colins et al., 2014). The 28-item CPTI questionnaire was used to assess the three psychopathy dimensions under investigation. Both teachers and parents assessed each item based on how the child typically behaves, using the following response scale: “Does not apply at all” (1), “Does not apply well” (2), “Applies fairly well” (3), and “Applies very well” (4). A psychopathy total score was also calculated (sum of 28 items). Previous studies have supported the psychometric properties of the CPTI based on both parent and teacher reports in terms of factor structure, internal consistency, and validity (e.g., Colins et al., 2018; Lopez-Romero et al., 2019). Mother and father reported CPTI scores, which were highly correlated (r =. 66 for GD, r = .60 for CU, r = .64 for INS, and r = .67 for the total score), were combined at the item level by taking the higher rating between parents. The resulting Cronbach’s alphas for the GD (α = 0.91), CU (α = 0.95), INS (α = 0.92), and the total score (α = 0.96) were high, evidencing excellent internal consistencies. Cronbach’s alpha for teacher reports (α = 0.90 for GD, 0.94 for CU, 0.92 for INS, 0.95 for total) were also high.

Griffith Empathy Measure (GEM; Dadds et al., 2008b). GEM is a 23-item parent-reported measure that assesses cognitive (6 items) and affective (9 items) empathy. Items are rated on a 9-point Likert scale (-4 = “strongly disagree” to 4= “strongly agree”). Affective empathy refers to the appropriate affective response to other’s situations than to one’s own, whereas cognitive empathy is the ability to take the perspective of others. Previous studies demonstrated good test-retest reliability and internal consistencies for the total score of empathy as well as for the cognitive and affective subscales (Dadds et al., 2008a; Georgiou et al., 2019a, b). In the present study, total GEM (α = 0.74), affective (α = 0.71), and cognitive (α = 0.67) scale scores demonstrated acceptable internal consistency. Mother and father reports were correlated at 0.53 for cognitive empathy, 0.54 for affective empathy, and 0.55 for total empathy, and were combined at the item level by taking the higher rating.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997). Child prosocial behavior, peer problems, and conduct problems were assessed by parents using the 15-item SDQ. Each subscale contains five items rated on a three-point Likert-type scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true, or 2 = certainly true). Mother and father reports showed strong correlations for conduct problems (r = .66), peer problems (r = .56), and prosocial behavior (r = .56) and were combined at the item level by taking the higher rating. The Cronbach’s alphas for conduct problems (α = 60), prosocial behavior (α = 0.59), and Peer Problems (α = 0.67) were acceptable.

Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI; Eyberg and Pincus, 1999). The ECBI is a 36-item parent-rating scale of child behavior problems. Parents rate the intensity and the frequency of the child’s behaviors on a 7-point scale (1= “never” to 7= “always”). For the current study, items referring to oppositional defiant behavior and conduct problems were included. Mother and father reports were highly correlated for oppositional defiant behavior (r = .69) and conduct problems (r = .63) and were combined by taking the higher rating between parents. Both oppositional defiant (α= 0.89) and conduct (α = 0.77) problems had good internal consistency.

Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ; Frick, 1991). APQ contains 42 items, rated from 1 (never) to 5 (always), assessing five subscales: parental involvement, positive parenting, poor monitoring/supervision, inconsistent discipline, and corporal punishment. Mother and father reports were moderately correlated, from 0.40 to 0.52, and were combined at the item level by taking the higher rating. The APQ scales generally showed adequate internal consistency ranging from 0.78 to 0.85.

Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI; Parker et al., 1979). The PBI is a 25-item scale that assesses parental care and parenting distress/overprotection. The items are rated on a 1 to 4 Likert-type scale, ranging from “Very like this” to “Very unlike this”. The reliability and validity of the PBI have been demonstrated in prior work (Wilhelm et al., 2005). For the current study, only the items of parental care were included. Mother and father reports were significantly correlated (r = .45) and were combined at the item level by taking the higher rating, resulting in a parental care subscale score with acceptable alpha (α = 0.69).

Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF; Abidin, 1995). PSI-SF is a 36-item scale comprising three subscales: Parental Distress, Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction, and Difficult child. For the current study, and based on our interest in parents’ characteristics, only the 12 items referring to parental distress were included. Parents rated each item from “Strongly disagree” (1) to “Strongly agree” (5), with higher scores indicating increased levels of parental distress. This subscale assesses the parents’ understanding of their ability to rear their child appropriately, the existence of social support, the stress experienced by their role as a parent, and its cost on other life roles due to child-rearing demands. Mother and father scores were significantly correlated (r = .50) and were combined by taking the higher rating between parents. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the parental distress subscale was good (α = 0.87) and similar to prior work (Fanti & Centifanti, 2014).

Preschool Social Behavior Scale-Teacher Form (PSBS-T; Crick et al., 1997). The PSBS-T is a 25-item teacher-report measure of children’s expression of aggression and prosocial behavior among peers. The Likert response scale for each item ranges from 1 (“Never or almost never true”) to 5 (“Always or almost always true”). For the purposes of the current study three subscales were assessed: relational aggression, overt/physical aggression, and prosocial behavior. Cronbach’s alpha showed all three scales to be highly reliable, ranging from 0.88 to 0.92.

Plan of Analyses

Initially, we ran zero-order correlations between parent and teacher-reported CPTI scales. We then conducted a series of multiple regression analyses with behavioral, emotional, and social context variables as outcomes and the three CPTI scales as independent variables. This analysis aimed to identify the unique contributions of each CPTI subscale score after accounting for their shared variance. For all analyses, standardized regression coefficients (β) from regression models incorporating all three CPTI subscales as predictors are presented alongside zero-order correlations. For comparison purposes, we also report correlations with the total psychopathy score. All the analyses were conducted in SPSS 28.0.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The Means (M) and Standard Deviations (SD) of the parent- and teacher-reported psychopathy dimensions are shown in Table 1. In general, parents reported higher psychopathic traits compared to teachers. Psychopathic traits were significantly inter-correlated, with stronger correlations between the CU and GD dimensions. Parent and teacher reports were also significantly correlated, although correlations were weak, suggesting variation in parent and teacher-reported psychopathic traits. Before proceeding with the regression analysis, the relevant assumptions of this statistical analysis were tested. Normality assumptions were met for all independent variables and multicollinearity was not a concern in all analyses.

Externalizing Problems and Prosocial Behaviors

As shown in Table 2, all three psychopathy dimensions were positively correlated with behavioral problems measured by ECBI (oppositional defiant behavior and conduct problems) and SDQ (Conduct Problems and Peer Problems) questionnaires. Unique associations were identified in the context of regression analysis for all the psychopathy dimensions. The INS dimension demonstrated the strongest association with oppositional defiant behavior (β = 0.42, p < .01) as assessed by ECBI, whereas CU (β = 0.18, p < .01) and GD (β = 0.10, p < .05) dimensions contributed to the prediction of oppositional defiant behavior to a weaker extend. The GD and INS dimensions accounted for the greatest proportion of variance on conduct problems, as measured by ECBI and SDQ questionnaires, with CU traits showing a weaker association. Interestingly, in the regression analysis, only CU traits were uniquely and negatively associated with prosocial behavior (β = -0.32, p<.01).

As shown in Table 3, similar associations were found for teachers’ reports in relation to the ECBI scale. All three psychopathy dimensions were positively correlated with behavioral problems at the zero-order level; however, only the INS dimension predicted Oppositional Defiant Behavior in the regression analysis. Regarding conduct problems, GD and INS uniquely predicted ECBI conduct problems, although INS and CU dimensions uniquely predicted SDQ conduct problems. Similar to parent reports, only the CU dimension negatively predicted prosocial behavior (β = -0.16, p < .01), as assessed with the SDQ; however, both INS (β = -0.27, p < .01) and CU (β = -42, p < .01) dimensions predicted teacher-reported prosocial behavior with the strongest association being with CU traits. Table 3 also lists the relations with measures of relational and overt aggression assessed by teachers. Consistent with our hypotheses, all three dimensions showed a positive relation with both forms of aggression, with GD accounting for the greatest proportion of variance of relational aggression (β = 0.53, p < .001). Associations between the CU and INS dimensions decreased substantially when accounting for their covariance with the GD dimension. In addition, the three dimensions similarly predicted overt aggression. Finally, the total psychopathy score was significantly related with all externalizing and prosocial behavior measures.

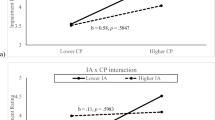

Cognitive and Affective Empathy

Regarding cognitive empathy, all parent-reported dimensions were significantly negatively correlated with children’s ability to understand the affective state of others. However, only the CU (β = -0.33, p < .01) and INS (β = -0.22, p < .01) dimensions predicted cognitive empathy after accounting for their covariance (Table 2). Regarding affective empathy, opposite associations for CU and INS dimensions were identified, with CU traits being negatively (β = -0.28, p < .01) and INS positively (β = 0.22, p < .01) associated with affective empathy. Based on parent reports, only CU traits significantly predicted general empathy (β = -0.45, p < .01). Further, only the teacher reported CU dimension was uniquely negatively associated with all empathy dimensions (Table 3). Interestingly, the total psychopathy scale was negatively related to cognitive and general empathy, but not affective empathy, for both parent and teacher ratings.

Social Context

All three CPTI dimensions were positively and similarly associated with parent-reported peer relation problems in the context of correlation and regression analysis. According to teachers’ reports, only the CU dimension was uniquely associated with peer problems (β = 0.14, p < .01). Concerning APQ parenting practices, CPTI dimensions were negatively correlated with all positive parental practices (i.e., parental involvement, positive parenting, and care); however, GD and INS dimensions were reduced to a non-significant level in the regression analysis predicting parental involvement and positive parenting. Similarly, the CU dimension was more strongly associated with the PBI care scale, with the GD dimension showing non-significant associations in the regression analysis. Moreover, in support of our hypothesis, all CPTI dimensions were positively related to negative parental practices (i.e., poor monitoring, inconsistent discipline, corporal punishment). The GD dimension showed no significant associations with inconsistent discipline in regression analyses. Parental distress showed a positive correlation with all CPTI scales, although mainly the CU and INS dimensions were uniquely associated with increases in parental distress. Finally, the total psychopathy score correlated significantly with peer problems and all parenting variables.

Discussion

The current study aimed to examine the relation of distinct psychopathy dimensions, assessed in childhood, with externalizing problems (i.e., conduct problems, oppositional defiant and aggression), empathic concern (i.e., cognitive and affective), and social relations (i.e., parents and peers). By investigating these associations early in development, we aimed to inform the literature regarding the importance of extending the multifaceted model of psychopathy to childhood. Supporting our hypothesis, the three CPTI factors were distinctively related to behavioural, social, and emotional outcomes highlighting the importance of considering all psychopathic dimensions to understand their unique effects (Ribeiro da Silva et al., 2019). After controlling for their shared variance, a unique contribution of CU traits to affective empathy and prosocial behavior was identified. In addition, the INS dimension more strongly predicted externalizing problems in relation to the other psychopathy dimensions, and the GD dimension was more strongly associated with relational aggression. Moreover, unique associations of the three psychopathy dimensions with parenting practices and peer relations were identified, highlighting the importance of psychopathic traits in forming the child’s social environment (i.e., Salekin, 2017). Findings can inform the development of effective intervention and prevention strategies that can be individualized tailored based on children’s psychopathic characteristics.

Externalizing Problems

Research investigating the causes of severe and stable externalizing problems, such as conduct problems, oppositional defiant behavior, and aggression, has supported the importance of psychopathic traits (see Frick et al., 2014; DeLisi, 2016; Moffitt et al., 2008 for reviews). By accounting for the interrelation between the three psychopathy dimensions, assessed by parents and teachers, the present study extends prior work by providing evidence for their unique associations with behavioral outcomes (Colins et al., 2014). Specifically, we provided support for the unique relation of the CU dimension with externalizing and conduct problems, agreeing with the inclusion of a CU-based specifier in the DMS-5 Conduct Disorder diagnosis (APA, 2013). Extending previous studies, the GD and INS dimensions were also associated with distinct behavioral problems, providing further evidence for the importance of investigating unique patterns of associations across all psychopathy dimensions (Colins et al., 2022).

The INS dimension, which refers to the child’s impulsive need for stimulation, sensation seeking, and proneness to boredom, was proven to play a vital role in predicting oppositional defiant behavioral problems, based on parent and teacher reports. Our findings come in support of Colledge and Blair’s (2001) hypothesis that impulsivity may be an underlying mechanism for the development of externalizing psychopathologies, such as oppositionality (also see Mathias et al., 2007). It might be that their impulsive decision-making often leads them to increased risk-taking acts and severe and stable behavioral problems (DeLisi, 2009). In addition, the GD dimension, but not the affective dimension, was a stronger predictor of conduct problems (see also Frick and White, 2008). According to Lau and Marsee (2013), individuals with an increased sense of grandiosity and glibness/superficial charm are threatened by perceived provocations regarding their self-worth, which may lead to antisocial and aggressive behavior as a way to regain and maintain their positive self-concept and their superiority over others (also see Thomaes et al., 2008). In this manner, their antisocial behavior functions as a means to establish their dominance over others and interpersonal entitlement. Their need to “feel powerful” makes them more prone to serious antisocial and conduct problems (Fanti & Henrich, 2015). An important contribution of the current study is the replication of findings regarding children’s behavioral problems across different informants, ensuring the representativeness of the findings in multiple contexts (i.e., home and school). Further, the identified associations early in development extend previous findings with adolescent samples highlighting this construct’s importance in forecasting future behavior problems and maladjustment (Barry et al., 2018).

In relation to aggressive behavior, no apparent difference was identified in terms of the association between the three dimensions of psychopathy with overt aggression, a finding that strengthens the suggestion of commonalities across psychopathic traits and aggressive outcomes (DeLisi, 2009; Fanti et al., 2013; Marsee et al., 2005). Concerning relational aggression, even though all three psychopathy dimensions were strongly correlated with this type of aggression, it was mainly the GD dimension that predicted relational aggression. There is an increased need for children high on the GD dimension to secure their social status over others, which might leas them to exclude others from their peer group or spread rumors when their fragile self-esteem is threatened (Fanti & Henrich, 2015; Knight et al., 2018; White et al., 2015).

The Distinction Between Affective and Cognitive Empathic Concern

Following previous findings, the unique relation between CU traits and affective empathy may explain the difficulties in social interaction and the strong association of these traits with severe behavioral problems and antisocial acts (Frick & White, 2008; DeLisi, 2016). According to Blair et al. (2001), the absence of negative affective arousal early in development can explain these children’s inability to withdraw or inhibit their antisocial responses making them less susceptible to parenting practices (also see Fanti et al., 2023). In addition, present findings provide further support for the literature proposing a number of empathic difficulties in the emotional processing of individuals high on CU traits early in development, such as their decreased orientation to facial emotional expressions and their lower response to distress cues that inhibit their moral and social development (Dadds et al., 2008a, 2012; Viding & McCrory, 2018). Regarding the INS dimension, the positive relation with affective empathy supports the greatest propensity of impulsive-antisocial individuals to feel greater empathic concern (Seara-Cardoso et al., 2012), and that their behavior problems are not due to empathy problems. Such opposing associations with affective empathy were found in prior work that controlled for the overlap between different psychopathy dimensions, pointing to individual differences in dysfunctions associated with empathy (Almeida et al., 2015; Seara-Cardoso et al., 2012). Interestingly, the total psychopathy score was not significantly associated with affective empathy, indicating that it is the CU dimension, which represents the affective component of psychopathy, that relates to emotional deficits in empathic resonance. This finding furthers the discussion regarding the utility of studying the unique relations of each psychopathic dimension with emotional processing deficits.

Interestingly, all three psychopathy dimensions were negatively related to cognitive empathy at the zero-order level, in support of our hypothesis. However, the CU dimension showed a stronger relation with the cognitive subcomponent of empathy, suggesting that the increased difficulties in identifying and understanding other’s emotional experiences might explain their difficulties in social interactions (Fanti, 2013). This finding indicates that by targeting deficits in facial emotion recognition, we can prevent the development of antisocial behaviors among children high on CU traits. Indeed, prior work suggested that even simple instructions to imitate facial expressions can improve antisocial individuals, with or without psychopathic traits, accuracy ratings of facial expressions (Kyranides et al., 2022).

Importantly, the CU dimension was related to deficits in both cognitive and affective empathy. Thus, individuals high on CU traits might show empathy deficits that extend beyond affective sharing and resonating with others, encompassing impairment in the ability to identify and understand emotions. Although these results contradict previous studies (e.g., Jones et al., 2010), our findings support research conducted with children (Georgiou et al., 2019a, b; Dadds et al., 2009). For example, Georgiou et al. (2019a, b) found that cognitive empathy deficits might explain the association between CU traits and externalizing problems, highlighting the importance of dysfunctions in children’s inability to identify thoughts or intentions and in understanding the feelings and emotions of others. It should be noted that these deficits might be specific to childhood, since a compensatory mechanism that enables children to learn how to identify and understand others’ emotions might develop later in life without necessarily sharing or experiencing those emotions (Dadds et al., 2009). According to Mullins-Nelson et al. (2006), this mechanism may explain why adults with psychopathic traits show improvements in cognitive empathy, making the study of empathy deficits across development even more important. Interestingly, the INS dimension was associated with decreased cognitive empathy, suggesting that impulsive individuals might be able to experience and affectively share others’ emotions, but they might not be able to cognitively understand others’ emotional experiences. However, this finding was only true for parent reports and did not reach significance when examining teacher reported psychopathic traits.

Social Context: The Importance of Parent and peer Relations

An important contribution of the current study is the investigation of the unique associations between psychopathy dimensions and social context factors, such as children’s peer relations and parental practices. Current findings supported the association of CU traits with ineffective parenting practices and difficulties in forming social relations with peers, pointing to the social burden facing those around children with CU traits (Haas et al., 2017). Since CU traits are associated with externalizing problems and empathic deficits, it is not surprising that prior research has supported the relationship of these traits with a range of social impairments that result in difficulties in forming relationships with peers (Fanti, 2013; Frick et al., 2014). Only the parent, but not the teacher, assessed INS and GD dimensions were associated with peer problems, suggesting non-consistent associations across informants. Thus, additional work is needed to examine these associations.

In addition, findings support the positive association between CU traits and negative parenting practices, such as corporal punishment (Pardini et al., 2007; Viding et al., 2005), inconsistent discipline (McDonald et al., 2011), and poor monitoring (Barker et al., 2011). CU children’s insensitivity to typical socializing practices might lead parents to adopt more negative and ineffective practices as a reaction to children’s misbehavior (Pasalich et al., 2012), which can then contribute to their behavioral problems (Waller et al., 2017). Moreover, the identified associations between CU traits with positive parenting and involvement provide evidence for a promising area for effective intervention. Kochanska et al. (2005) have shown that positive parenting strategies and parental care can act as protective factors against the development of externalizing problems in children high on CU traits. Importantly, Pasalich et al. (2012) showed that children high in CU traits were more responsive to positive parenting and warmth, which promoted their affective response and the internalization of parental norms and values.

Notwithstanding the importance of the affective dimension in predicting difficulties in children’s social relations, our findings supported the relation between the behavioral dimension of CPTI and parents’ inconsistent discipline strategies. A closer review of the empirical research indicates that the implementation of harsh parenting practices among highly impulsive children is a strong vulnerability factor for developing externalizing behaviors (Slagt et al., 2016). The association of impulsivity with the INS dimension is strongly related to the loss of control that leads parents to adopt ineffective practices, which in turn prevents children from developing healthy prosocial behavior, such as helping or sharing with others (Centifanti et al., 2016).

Interestingly, the GD dimension was not strongly associated with parenting practices, suggesting that social context factors might play a stronger role in the development of callous, unemotional, and impulsive characteristics. Moreover, our findings suggested that parents of children high on both the CU and INS dimensions were more likely to report increased levels of parenting distress. Having a child who is impulsive or callous might lead parents to feel insufficient in their role, a feeling that can result in parents’ distress and lack of support (Fite et al., 2008). By providing evidence for difficulties in social relations, the current study points to the importance of prevention and intervention practices mainly targeting CU and INS dimensions through parent-child relationships. At the same time, GD characteristics might not impose so much distress in parent-child interactions.

Strengths, Limitations and Conclusions

There are several strengths of the current study. First, we included a relatively large community-based sample of children from the age of three. Parents and teachers completed a battery of questionnaires to assess these traits’ expression early in development. We also integrated information from parents and teachers, aiming to cover the full manifestation of the construct (Wang et al., 2018). In addition, this study aimed to extend the literature on the unique contribution of each psychopathy dimension in predicting externalizing problems (i.e., oppositional defiant; conduct problems), social relations (i.e., parenting and peer relations), empathy deficits, and the strong contribution of their overall score in the prediction of these discrepancies.

Despite its strengths, our study has several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the findings. Our assessment of the constructs of interest was based on parent and teacher reports. Future research may benefit from experimental measures of empathy that are less subject to bias, such as physiological measurements and laboratory tasks (i.e., the use of emotional videos and tasks). Nevertheless, parents and teachers are critical sources for children’s behavior at home and school, especially in rating externalizing problems and peer relations (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). Regarding participants, we used a community sample of children, and future work should also replicate our findings in clinical samples. Overall, more research is needed to extend the importance of the unique contribution of each psychopathy dimension in different aspects of children’s behavior and social interactions early in development.

In conclusion, to better understand the developmental precursors of severe antisocial and delinquent acts, it is important to investigate how each psychopathy dimension uniquely contributes to children’s behavioral problems, empathic concern, and social relations early in development (Salekin, 2017). At the same time, the three dimensions of psychopathic personality share similar qualities that research needs to examine further. Specifically, findings from the current study indicated that all three psychopathy dimensions are associated with different forms of conduct problems and aggressive behavior. Further, we provide novel evidence for the unique contribution of impulsivity to oppositionality. In contrast, the GD dimension was more uniquely associated with relational aggression, an association that can be explained by their increased need for social dominance. Concerning the emphasis given on the role of the CU dimension, our study supported its importance in predicting behavioral problems, establishing its role in the diagnosis of Conduct Disorder. Also, agreeing with theoretical suggestions, children high on CU traits had a difficulty in expressing empathic concern and develop effective social relations, which was not necessarily true for the other dimensions.

Current findings are consistent with a growing body of research on distinct causal mechanisms leading to antisocial behaviors (Ribiero da Silva et al., 2020; Silverthorn and Frick, 1999), and as such our study can greatly inform the development of effective prevention and intervention strategies. For example, intervention programs that aim to train children with increased levels of CU traits on emotion recognition and affective empathy skills may lead to decreased conduct problems (Dadds et al., 2012). On the other hand, children high on the INS dimension might need programs to enhance their self-regulation abilities in order to avoid high-risk behaviors that violates the rights of others (e.g., oppositionality). In contrast, those high on the GD dimension need to learn how to understand and control their need for social dominance, which might reduce their engagement in relational aggression.

References

Abidin, R. R. (1995). Parenting stress index. Charlottesville, VA: Pediatric Psychology Press.

Almeida, P., Seixas, M., Ferreira-Santos, F., et al. (2015). Empathic, moral and antisocial outcomes associated with distinct components of psychopathy in healthy individuals: A triarchic model approach. Personality and Individuals Differences, 85, 205–211.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

and challenges. Psychological Medicine, 48, 566–577.

Andershed, H., Colins, O. F., Salekin, R. T., Lordos, A., Kyranides, M. N., & Fanti, K. A. (2018). Callous-unemotional traits only versus the multidimensional psychopathy construct as predictors of various antisocial outcomes during early adolescence. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40(1), 16–25.

Andrade, B., & Tannock, R. (2012). The direct effects of inattention and hyperactivity/ impulsivity on peer problems and mediating roles of prosocial and conduct problem behaviors in a community sample of children. Journal of Attention Disorder, 17, 670–680.

Barker, E., Oliver, B., Viding, E., Salekin, R., & Maughan, B. (2011). The impact of prenatal maternal risk, fearless temperament, and early parenting on adolescent callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 878–888.

Barry, C. T., McDougall, K. H., Anderson, A. C., & Bindon, A. L. (2018). Global and contingent self-esteem as moderators in the relations between adolescent narcissism, callous-unemotional traits, and aggressions. Personality and Individuals Differences, 123, 1–5.

Barry, T. D., Barry, C. T., Deming, A. M., & Lochman, J. E. (2008). Stability of psychopathic characteristics in childhood: The influence of social relationships. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35, 244–262.

Baskin-Sommers, A., Krusemark, E., & Ronningstam, E. (2014). Empathy in narcissistic personality disorder: From clinical and empirical perspectives. Personality Disorders, 5(3), 323–333.

Blair, R. (2007). Empathic dysfunction in psychopathic individuals. In T. Farrow, & P. Woodruff (Eds.), Empathy in mental illness (pp. 3–16). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Blair, R. J. R., Colledge, E., Murray, L., & Mitchell, D. G. V. (2001). A selective impairment in the processing of sad and fearful expressions in children with psychopathic tendencies. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29, 491–498.

Centifanti, L. C. M., Meins, E., & Fernyhough, C. (2016). Callous-unemotional traits and impulsivity: Distinct longitudinal relations with mind-mindedness and understanding of others. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57, 84–92.

Colins, O. F., Andershed, H., Frogner, L., Lopez-Romero, L., Veen, V., & Andershed, A. K. (2014). A new measure to assess psychopathic personality in children: The child problematic traits Inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 36, 4–21.

Colins, O. F., Andershed, H., Hellfeldt, K., & Fanti, K. A. (2022). The incremental usefulness of teacher-rated psychopathic traits in 5- to 7- year old in predicting teacher, parent, and child self-reported antisocial behavior at a six-year follow-up. Journal of Criminal Justice, 80, 101771.

Colins, O. F., Andershed, H., Salekin, R. T., & Fanti, K. A. (2018). Comparing different approached for subtyping children with conduct problems: Callous-unemotional traits only versus the multidimensional psychopathy construct. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40(1), 6–15.

Colins, O. F., Fanti, K. A., & Andershed, H. (2020). The DSM-5 Limited Prosocial Emotions Specifier for Conduct Disorder: Comorbid problems, prognosis, and antecedents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(8), 1020–1029.

Colledge, E., & Blair, R. J. R. (2001). The relationship in children between the inattention and impulsivity components of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder and psychopathic tendencies. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 1175–1187.

Crick, N. R., Cass, J. F., & Mosher, M. (1997). Relational and physical aggression in preschool. Developmental Psychology, 33, 579–588.

Dadds, M. R., Cauchi, A. J., Wimalaweera, S., Hawes, D. J., & Brennan, J. (2012). Outcomes, moderators, and mediators of empathic-emotion recognition training for complex conduct problems in childhood. Psychiatry Research, 199, 201–207.

Dadds, M. R., Hawes, D. J., Frost, A. D., Vassallo, V., Bunn, P., Hunter, K., & Merz, S. (2008b). The measurement of empathy in children using parent reports. Journal of Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 39, 111–122.

Dadds, M. R., Hawes, D. J., Frost, A. D., Vassallo, V., et al. (2009). Learning to “talk the talk”: The relationship of psychopathic traits to deficits in empathy across childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 50, 599–606.

Dadds, M. R., Masry, E., Wimalaweera, Y., S., & Guastella, A. J. (2008a). Reduced eye gaze explains, “fear blindness” in childhood psychopathic traits. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 455–463.

da Ribeiro, D., Vagos, P., & Rijo, D. (2019). Conceptualizing psychopathic traits from an evolutionary-based perspective: An empirical study in a community sample of boys and girls. Current Psychology, 40, 3931–3943.

DeLisi, M. (2009). Psychopathy is the unified theory of crime. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 7(3), 256–273.

DeLisi, M. (2016). Psychopathy as Unified Theory of Crime. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

De Los Reyes, A., & Kazdin, A. E. (2005). Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin, 131(4), 483–509.

Demetriou, C., & Fanti, K. A. (2022). Are children high on callous-unemotional traits emotionally blind? Testing eye-gaze differences. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 53(4), 623–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01152-3.

Eyberg, S. M., & Pincus, D. (1999). Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory and Sutter-Eyberg Student Behavior Inventory-Revised. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Fanti, K. A. (2013). Individual, social, and behavioral factors associated with co-occurring conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 811–824.

Fanti, K. A., & Centifanti, M. (2014). Childhood callous-unemotional traits moderate the relation between parenting distress and conduct problems over time. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 45, 173–184.

Fanti, K. A., Demetriou, C. A., & Kimonis, E. R. (2013). Variants of callous-unemotional conduct problems in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 964–979.

Fanti, K. A., & Henrich, C. C. (2015). Effects of self-esteem and narcissism on bullying and victimization during early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 35(1), 5–29.

Fanti, K. A., Konikkou, K., Georgiou, G., Petridou, M., Demetriou, C., & Kyranides, M. (2023a). Physiological reactivity to fear moderates the relation between parenting distress with conduct and prosocial behaviors. Child Development, 94, 363–379.

Fanti, K. A., Kyranides, M. N., Lordos, A., Colins, O. F., & Andershed, H. (2018). Unique and interactive associations of callous-unemotional traits, Impulsivity and Grandiosity with child and adolescent Conduct disorder symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40(1), 40–49.

Fanti, K. A., Kyranides, M., & Panayiotou, G. (2017). Facial reactions to violent and comedy films: Association with callous–unemotional traits and impulsive aggression. Cognition and Emotion, 31(2), 209–224.

Fanti, K. A., Mavrommatis, I., Colins, O., & Andershed, H. (2023b). Fearlessness as an underlying mechanism leading to conduct problems: Testing the intermediate effects of parenting, anxiety, and callous-unemotional traits. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. 10.1007/s10802-023-01076-7.

Fite, P. J., Greening, L., & Stoppelbein, L. (2008). Relation between parenting stress and psychopathic traits among children. Behavioral Science and Law, 26, 239–248.

Frick, P. J. (1991). The Alabama parenting questionnaire. Alabama: University of Alabama.

Frick, P. J., Bodin, S. D., & Barry, C. T. (2000). Psychopathic traits and conduct problems in community and clinic-referred samples of children: Further development of the psychopathy screening device. Psychological Assessment, 12, 382–393.

Frick, P. J., Ray, J., Thornton, L., & Kahn, R. E. (2014). Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 1–57.

Frick, P. J., & White, S. F. (2008). Research review: The importance of callous-unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 359–375.

Fronger, L., Andershed, A. K., & Andershed, H. (2018). Psychopathic personality works better than CU traits for predicting fearlessness and ADHD symptoms among children with Conduct problems. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40, 26–39.

Georgiou, G., Demetriou, C. A., & Fanti, K. A. (2019a). Distinct Empathy Profiles in callous unemotional and autistic traits: Investigating Unique and Interactive Associations with Affective and Cognitive Empathy. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47, 1863–1873.

Georgiou, G., Kimonis, E. R., & Fanti, K. A. (2019b). What do others feel? Cognitive empathy deficits explain the association between callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems among preschool children. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 16, 633–653.

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581–586.

Haas, S. M., Becker, S. P., Epstein, J. N., & Frick, P. J. (2017). Callous-unemotional traits are uniquely associated with poorer peer functioning in school-aged children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46, 781–793.

Horton, R. S., Bleau, G., & Drwecki, B. (2006). Parenting narcissus: What are the links between parenting and narcissism? Journal of Personality, 74(2), 345–376.

Hoza, B. (2007). Peer functioning in children with ADHD. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 655–663.

Jones, A. P., Happé, F. G. E., Gilbert, F., Burnett, S., & Viding, E. (2010). Feeling, caring, knowing: Different types of empathy deficit in boys with psychopathic tendencies and autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 51, 1188–1197.

Kerr, M., van Zalk, M., & Stattin, H. (2012). Psychopathic traits moderate peer influence on adolescent delinquency. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(8), 826–835.

Kimonis, E. R., Fanti, K. A., Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous, X., Mertan, B., Goulter, N., & Katsimicha, E. (2016). Can callous-unemotional traits be reliably measured in preschoolers? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 625–638.

Kimonis, E. R., Frick, P. J., Fazekas, H., & Loney, B. R. (2006). Psychopathy, aggression, and the processing of emotional stimuli in non–referred girls and boys. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 24, 21–37.

Knight, N. M., Dahlen, E. R., Bullock-Yowell, E., & Madson, M. B. (2018). The HEXACO model of personality and Dark Triad in relational aggression. Personality and Individual Differences, 122, 109–114.

Kochanska, G., Forman, D. R., Aksan, N., & Dunbar, S. B. (2005). Pathways to conscience: Early mother–child mutually responsive orientation and children’s moral emotion, conduct, and cognition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 19–34.

Kyranides, M. N., Petridou, M., Gokani, H. A., Hill, S., & Fanti, K. A. (2022). Reading and reacting to faces, the effect of facial mimicry in improving facial emotion recognition in individuals with antisocial behavior and psychopathic traits. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02749-0.

Lahey, B. B. (2014). What we need to know about callous-unemotional traits: Comment on Frick, Ray, Thornton, and Kahn (2014). Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 58–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033387

Lau, K. S., & Marsee, M. A. (2013). Exploring narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism in youth: Examination of associations with antisocial behavior and aggression. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22, 355–367.

Lopez-Romero, L., Salekin, R. T., Romero, E., Andershed, H., & Colins, O. F. (2022). Psychopathic personality configurations in early childhood: A reponse to Dvoskin et al. (2022). Journal of Personality Disorders, 36(3), 254–263.

López-Romero, L., Colins, O. F., Fanti, K., Salekin, R. T., Romero, E., & Andershed, H. (2022). Testing the predictive and incremental validity of callous-unemotional traits versus the multidimensional psychopathy construct in preschool children. Journal of Criminal Justice, 80, 101744.

López-Romero, L., Maneiro, L., Colins, O. F., Andershed, H., & Romero, E. (2019). Psychopathic traits in early childhood: Further multi-informant validation of the child problematic traits inventory (CPTI). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 41, 366–374.

López-Romero, L., Molinuevo, B., Bonillo, A., et al. (2018). Psychometric properties of the spanish version of the child problematic traits Inventory in 3 to 12-year-old spanish children. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35, 842–854.

Marissen, M. A. E., Deen, M. L., & Franken, I. H. A. (2012). Disturbed emotion recognition in patients with narcissistic personality disorder. Psychiatry Research, 198, 269–273.

Marsee, M. A., Silverthorn, P., & Frick, P. J. (2005). The association of psychopathic traits with aggression and delinquency in non-referred boys and girls. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 23, 803–817.

Mathias, C. W., Furr, R. M., Daniel, S. S., Marsh, D. M., Shannon, E. E., & Dougherty, D. M. (2007). The relationship of inattentiveness, hyperactivity, and psychopathy among adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(6), 1333–1343.

McDonald, R., Dodson, M., Rosenfield, D., & Jouriles, E. (2011). Effects of a parenting intervention on features of psychopathy in children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 1013–1023.

Mechanic, K., & Barry, C. (2015). Adolescent grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: Associations with perceived parenting practices. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1510–1518.

Menting, B., van Lier, P. A. C., Koot, H. M., Pardini, D., & Loeber, R. (2016). Cognitive impulsivity and the development of delinquency from late childhood to early adulthood: Moderating effects of parenting behavior and peer relationships. Development and Psychopathology, 28, 167–183.

Mills-Koonce, W. R., Willoughby, M. T., Garrett-Peters, P., Wagner, N., & Vernon-Feagans, L. (2016). The interplay among socioeconomic status, household chaos, and parenting in the prediction of child conduct problems and callous-unemotional behaviors. Development & Psychopathology, 28, 757–771.

Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Jaffee, S. R., Kim-Cohen, J., Koenen, K. C., Odgers, C. L., Slutske, W. S., & Viding, E. (2008). DSM-V Conduct Disorder: Research needs for an evidence base. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 3–33.

Mullins-Nelson, J. L., Salekin, R. T., & Leistico, A. M. R. (2006). Psychopathy, empathy, and perspective-taking ability in a community sample: Implications for the successful psychopathy concept. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 5, 133–149.

Muñoz, L. C., Kerr, M., & Bešić, N. (2008). Peer relationships of youths with psychopathic personality traits: A matter of perspective. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35, 212–227.

Pajevic, M., Vukosavljevic-Gvozden, T., Stevanovic, N., & Neuman, C. S. (2018). The relationship between the Dark Tetrad and a two-dimensional view of empathy. Personality and Individual Differences, 123, 125–130.

Pardini, D., Lochman, J., & Powell, N. (2007). The development of callous–unemotional traits and antisocial behavior in children: Are there shared and/or unique predictors? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36, 319–333.

Parker, G., Tupling, H., & Brown, L. B. (1979). A parental bonding instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 52(1), 1–10.

Pasalich, D. S., Dadds, M. R., Hawes, D. J., & Brennan, J. (2012). Attachment and callous-unemotional traits in children with early-onset conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(8), 838–845.

Patrick, C. J., Fowles, D. C., & Krueger, R. F. (2009). Triarchic conceptualization of psychopathy: Developmental origins of disinhibition, boldness, and meanness. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 913–938.

Piatigorsky, A., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2004). Psychopathic traits in boys with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Concurrent and longitudinal correlates. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 535–550.

Ritter, K., Dziobek, I., Preissler, S., Rüter, A., Vater, A., et al. (2011). Lack of empathy in patients with narcissistic personality disorder. Psychiatry Research, 187, 241–247.

Ručević, S., Farrington, D. P., & Andershed, H. (2022). The role of parental psychopathic traits: Longitudinal relations with parenting, child’s psychopathy features and conduct problems. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-018-9659-5.

Salekin, R. T. (2017). Research Review: What do we know about psychopathic traits in children? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(11), 1180–1200.

Salekin, R. T., & Andershed, H. (2022). Psychopathic personality, and its dimensions in the prediction of negative outcomes: Do they offer incremental value above and beyond common risk factors? Journal of Criminal Justice, 80, 101914.

Seara-Cardoso, A., Neuman, C., Roiser, J., McCrory, E., & Viding, E. (2012). Investigating associations between empathy, morality, and psychopathic personality traits in the general population. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 67–71.

Silverthorn, P., & Frick, P. J. (1999). Developmental pathways to antisocial behavior: The delayed-onset pathway in girls. Development and Psychopathology, 11, 101–126.

Slagt, M., Dubas, J. S., & van Aken, M. A. G. (2016). Differential susceptibility to parenting in middle childhood: Do impulsivity, effortful control, and negative emotionality indicate susceptibility or vulnerability? Infant and Child Development, 25, 302–324.

Thomaes, S., Bushman, B. J., Stegge, H., & Olthof, T. (2008). Trumping shame by blasts of noise: Narcissism, self-esteem, shame, and aggression in young adolescents. Child Development, 79, 1792–1801.

Trumpeter, N. N., Watson, P. J., O’Leary, B. J., & Weathington, B. L. (2008). Self-functioning and perceived parenting: Relations of parental empathy and love inconsistency with narcissism, depression, and self-esteem. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 169, 51–71.

Viding, E., Blair, R., Moffitt, T., & Plomin, R. (2005). Evidence for substantial genetic risk for psychopathy in 7-year-olds. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 592–597.

Viding, E., & McCrory, E. J. (2018). Understanding the development of psychopathy: Progress.

Waller, R., Gardner, F., & Hyde, L. W. (2013). What are the associations between parenting, callous–unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior in youth? A systematic review of evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 593–608.

Waller, R., Gardner, F., Viding, E., Shaw, D. S., Dishion, T. J., Wilson, M. N., & Hyde, L. W. (2014). Bidirectional association between parental warmth, callous-unemotional behavior, and behavior problems in high-risk preschoolers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(8), 1275–1285.

Waller, R., Shaw, D. S., & Hyde, L. W. (2017). Observed fearlessness and positive parenting interact to predict childhood callous-unemotional behaviors among low-income boys. Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(3), 282–291.

Waller, R., Wagner, N. J., Barstead, M. G., Subar, A., Petersen, J. L., Hyde, J. S., & Hyde, L. W. (2020). A meta-analysis of the associations between callous-unemotional traits and empathy, prosociality, and guilt. Clinical Psychology Review, 78, 101809.

Wall, T. D., Frick, P. J., Fanti, K. A., Kimonis, E. R., & Lordos, A. (2016). Factors differentiating callous-unemotional characteristics with and without conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(8), 976–983.

Walter, H. (2012). Social cognitive neuroscience of empathy: Concepts, circuits, and genes. Emotion Review, 4(1), 9–17.

Wang, M. C., Colins, O. F., Deng, Q., Deng, J., Huang, Y., & Andershed, H. (2018). The inventory of child problematic traits: A further validation in chinese children with multiple informants. Psychological Assessment, 30(7), 956–966.

White, B. A., Gordon, H., & Guerra, R. C. (2015). Callous-unemotional traits and empathy in proactive and reactive relational aggression in young women. Personality and Individual Differences, 75, 185–189.

Wilhelm, K., Niven, H., Parker, G., & Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. (2005). The stability of the parental bonding instrument over a 20-year period. Psychological Medicine, 35, 387–393.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Cyprus Libraries Consortium (CLC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee (Centre of Educational Research and Assessment of Cyprus, Pedagogical Institute, Ministry of Education and Culture and Cyprus National Bioethics Committee) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Demetriou, C.A., Colins, O.F., Andershed, H. et al. Assessing Psychopathic Traits Early in Development: Testing Potential Associations with Social, Behavioral, and Affective Factors. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 45, 767–780 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-023-10059-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-023-10059-3