Abstract

Silicone/phosphor composite, which serve as mechanical protection and light conversion material, is an integral part of white light-emitting diode (LED) package. In this paper, a comprehensive study is conducted to investigate the effect of humidity and phosphor on moisture absorption, hygroscopic swelling, mechanical behavior, as well as thermal properties of silicone/phosphor composite in comparison with the pure silicone. SEM/EDAX and FTIR were performed to identify the phosphor and silicone compositions. Through moisture sorption test, it has been observed that the addition of phosphor significantly lowers the capacity of moisture absorption, but accelerates the diffusivity of moisture absorption. The hygroscopic swelling test showed that the phosphor has little effect on the swelling compared to the pure silicone sample. Both moisture absorption/desorption and hygroscopic swelling/de-swelling are reversible. Strain ramp test revealed that the phosphor enhances the stiffness of the composite. The moisture absorption, however, has negligible impact on mechanical stiffness for both pure and composite samples. Finally, thermal expansion test showed that the coefficient of thermal expansion does not change with the addition of phosphor into pure silicone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

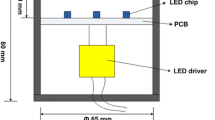

High power phosphor-converted white light-emitting diodes (pc-WLEDs) have been accepted as an important substitute for traditional lighting sources due to their high luminous efficiency, low power consumption, longer lifetime and their environmental friendliness [1, 2]. In pc-WLEDs system, silicone or silicone-based materials are commonly used as an encapsulant due to good optical properties like high refractive index, good ultraviolet light resistance [3], and high thermal stability [4] and the resistance to discoloration at high temperature [5]. In pc-WLEDs, the silicone encapsulants are combined with phosphors to form a composite for blue light conversion and chip protection. As shown in Fig. 1, LED packages have evolved from traditional wire-bond-based package to flip-chip package with silicone/phosphor composite used as film to encapsulate LED chip in chip-scale package (CSP) or chip-on-board (COB) package [2].

The function of silicone/phosphor composite in white LED package a traditional packaging structure; b chip-scale-package (CSP) or chip-on-board structure [2]

From the recent study [6,7,8,9], it has been observed that most degradation of white LED products is mainly caused by the degradation of encapsulants. Some researchers [10,11,12,13] reported that high temperature and high humidity usually contributed to LED’s failure. Although silicone encapsulant exhibits better thermal stability than epoxy-based resins, the darkening and carbonization phenomenon were observed under high temperature and high humidity condition [14, 15]. Absorption of moisture from environment causes the change in silicone properties like coefficient of thermal expansion and elasticity modulus [16, 17]. The water trapped inside silicone capsule may cause bubble generation [18], dissolution of the phosphors [19], and light scattering [13]. Fan et al. [20, 21] studied the interaction of silicone and phosphor, and showed that moisture could be the reason behind degradation of silicone/phosphor composite due to pH change. It further causes the degradation of light-conversion efficiency of phosphors and the transmittance of silicone. Due to this reason it suffers a high temperature treatment during operation [22, 23]. Higher temperature at the phosphor/binder interface can cause discoloration, decohesion, and cracking of the interface layer [24]. Zhang et al. [25] reported that heat treatment of multicolor phosphor films leads to serious degradation of luminous intensity. According to the study of Wang et al. [26], the introduction of phosphor powder into the silicone matrix shortens the cure rate, while ultraviolet radiation and temperature accelerate the cure of silicone/phosphor composite by increasing the rate of cross-linking. Khalilullah et al. [27] tested the silicone/phosphor composite under high moisture condition and found irreversible swelling despite the reversibility of moisture absorption/desorption. Another study [28] revealed that addition of phosphor with a high temperature aging will stiffen the silicone matrix significantly. Increased Young’s modulus of the silicone was observed with aging time which causes severe stress conditions and cracks in the material. Recently, Fan et al. [29] investigated the curing mechanism of phosphor/silicone composites and evaluated their mechanical properties after a high moisture ageing test. Tang et al. studied the reliability of the chip-scale packaged LEDs under overdriving condition [30].

In this paper, a comprehensive study is conducted to investigate the effect of humidity and phosphor on moisture absorption, hygroscopic swelling, mechanical behavior, as well as thermal properties of silicone/phosphor composite in comparison with the pure silicone. Specifically, in situ hygroscopic swelling/de-swelling behavior is restudied for the repeatability and to confirm the non-existence of irreversible swelling observed in the previous study [27]. SEM/EDAX and FTIR were performed to identify the phosphor and silicone compositions. A series of tests, including in situ moisture absorption/desorption, hygroscopic swelling, strain ramp test, as well as thermal expansion measurement, were conducted.

2 Experimental method

2.1 Materials

Silicone and silicone/phosphor composite materials were used in this study. For both samples, a general manufacturing procedure was provided by a manufacturer company, keeping the chemical composition of the samples unknown. The silicone/phosphor samples were prepared by mixing the phosphor powder with silicone, then a curing process was performed as follows: 1-hour prebake at 100 °C, 2 h curing at 150 °C and then cooling to ambient temperature. The pure silicone sample was prepared similarly but without the addition of phosphor. In this study, the thickness of all test samples is made as ~ 0.5 mm, which is a typical thickness in actual LED package. The concentration of phosphor in composite is ~ 9% in mass fraction.

2.2 SEM/EDAX

Identification of the phosphor in the sample was achieved using energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). Samples were placed in a Hitachi S-3400 N (SEM) equipped with a back-scatter detector and an AMETEK EDAX EDS system. Samples were prepared by securing small pieces cut from the bulk silicone phosphor composite using conductive carbon tape and copper tape to reduce charging of the electrically insulating silicone. To increase the sensitivity of the EDAX analysis the elemental mapping was used to identify subsurface phosphor particles based on threshold X-ray emission at characteristic wavelengths.

2.3 FTIR

Attenuated total reflectance fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) was used to characterize the silicone composite and pure silicone samples. A perkin elmer spectrum Two FTIR was used. Samples were prepared by cutting small pieces from the bulk. Samples were placed in the ATR accessory and the spectra were captured.

2.4 TGA sorption

As shown in Fig. 2, the moisture absorption test was performed using TA TGA Q5000 instrument equipped with environmental chamber having high accurate temperature and humidity control (Accuracy: ± 1% RH). It measures the amount and rate of change in the weight (Weighing accuracy: ± 0.1%) of a material as a function of temperature and time in a controlled environment. The moisture chamber allows in situ weight measurement during moisture diffusion. Dry nitrogen is used to dehumidify the sample chamber and as the moisture carrier to elevate the humidity.

2.5 DMA-RH

Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) was performed using at TA DMA Q800 equipped with the humidity control (see Fig. 2). The DMA-RH accessory enables analyzing the hygroscopic swelling behavior by controlling temperature and relative humidity. Dry nitrogen was used to dehumidify the sample chamber. The samples were cut into 10 × 3 mm size. One of the 3 mm wide ends was held by a fixed clamp and other end was held by movable clamp. Stress–strain curves were measured for pure silicone and silicone/phosphor composite samples with and without the effect of humidity.

2.6 TMA

Thermomechanical analysis (TMA) measures sample displacement as a function of temperature, time and applied force. TMA was used to determine the linear coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) for pure silicone and silicone/phosphor composite samples were measured from 25 °C to 300 °C.

3 Mathematical model for moisture diffusion

In this study 1D-diffusion model was used. In an isotropic medium moisture diffusion can be described by Fick’s diffusion law. The 1-D diffusion equation is expressed by [31, 32] as follows:

Here, C is the concentration of diffusing material in a medium, which changes with position x and time t. D is the diffusivity. Equation 1 can be applied to an infinite plate as shown in Fig. 3 below:

Assume the coordinate of the origin is at the center of the plate, the initial and boundary conditions of moisture absorption can be defined as:

Here, Co is initial concentration in the material and Cs constant moisture concentration at the surface, and h is thickness of the plate.

The solution of Eqs. 1–2 is given by:

The total amount of moisture entering the plate at time t can be calculated as:

Here, \(M_{\infty }\) is the final weight gain of the sample. Equation 5 was used to calculate saturated moisture content Csat from the experimental data. If the volume V is known, then one can calculate the saturated moisture content using following equation:

4 Data regression

Least-square regression method was used to calculate diffusivity D and saturated moisture content Csat. Data regression was done using following equation-.

Here, \({\text{M}}_{{{\text{t}},{\text{i}}}}^{\exp }\) is the i-th number of experimental weight gain value at t time and \({\text{M}}_{{{\text{t}},{\text{i}}}}^{\text{cal}}\) is the calculated weight gain value m is the number of total data points in a single experiment. Coefficient of determination (COD) R2 can be obtained by the following equation-.

Here, SSTotal is the sum of squared differences between average value and the data points. R2 is the measure of how much experimental data fits the theoretical model. The values of R2 ranges between 0 to 1. Value 1 means a perfect association of theoretical model and experimental data, whereas 0 means no association.

5 Results and discussions

ATR-FTIR is used to characterize the functional groups of polymer materials. Figure 4 is a representative ATR-FTIR spectra showing the functional groups of pure silicone sample. The spectra for pure silicone and silicone/phosphor composite were found to be identical except minor variations attributed to noise.

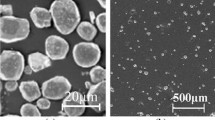

From SEM micrograph of silicone/phosphor composite shown in Fig. 5, the particles can be seen embedded in the silicone matrix and extending out of the sample along the cut. Figure 6 shows an elemental map using the signal at the yttrium Lα peak as a threshold for locating particles. Yttrium was chosen because of its presence in general EDS analysis of the sample and its colocalization with particles in the SEM image.

Figure 7 shows an EDS spectrum taken from the regions thresholded for yttrium. The spectrum is consistent with the composition of Cerium doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet (YAG: Ce), a commonly used phosphor in pc-wLEDs that emits the yellow light. The silicon element in the spectra is from the silicone matrix. The carbon is from side functional groups on the silicone as well as residual signal from the carbon tape used to secure the samples.

Figure 8 represents the TGA-sorption analysis results. It can be seen that the addition of phosphor into silicone reduces the significant amount of moisture upon saturation. From Fig. 6, both moisture absorption and desorption are reversible.

Figures 9 and 10 are the mathematical fitting of the moisture absorption and desorption for both pure silicone and silicone/phosphor composite. It can be seen that both pure silicone and silicone/phosphor composite follows the Fickian diffusion law well. Tables 1 and 2 show the extracted properties from the fit based on the experimental data. We can see that with the addition of phosphor, the diffusivity increases, implying the moisture absorption is accelerated compares to the pure silicone material. The saturated moisture concentration for silicone phosphor is significantly lower than that in pure silicone. For each sample the diffusivity and the saturated moisture concentration are almost same during absorption and desorption phase, which means that the moisture absorption and desorption are reversible.

Figures 11 and 12 describes the hygroscopic swelling and de-swelling during moisture absorption and desorption. The experimental data were taken from a full cycle of moisture absorption and desorption (ramp down–hold–ramp up–hold–ramp down–hold). In these two figures, the dashed line is humidity applied (on the second y-axis on the right). It clearly showed the repeatability and consistency among the seven samples (three pure silicone samples and four silicone/phosphor composite samples). The swelling is reversible for both materials. In the previous study [27], a permanent swelling deformation was observed during the initial humidity ramp up phase. Such a phenomenon occurred in the present testing but it has been attributed to the instrument setup issue. From Figs. 11 and 12, it was also noticed that hygroscopic swelling strain is almost the same for both pure silicone and silicone/phosphor. This indicates that the addition of phosphor into silicone has a little effect on the swelling behavior.

Figure 13 plotted the stress–strain curve with and without humidity during strain ramp test for both pure silicone and silicone/phosphor composite. It can be seen that that the moisture absorption has almost no effect on the stress–strain behavior for both pure silicone and silicone/phosphor composite. However, it is clearly seen that the silicone/phosphor composite has greater stiffness than pure silicone, but the moisture absorption does not change the material stress–strain behavior.

Figure 14 plots the experimental data of the thermal strain as function of temperature from 50 °C to 300 °C. It shows they have almost the same value of the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE, the slope of curve). It indicates that the addition of phosphor into silicone does not change the value of CTE.

6 Conclusions

In this paper, the effect of humidity and phosphor addition on silicone/phosphor composite was investigated. We performed an in situ TGA moisture absorption/desorption test for both silicone and silicone/phosphor samples. The results showed both samples follow the Fickian diffusion behavior well. Moisture absorption and desorption are also reversible with the addition of phosphor into silicone. However, the composite reduces the significant amount of moisture absorption compared to the pure silicone, and the diffusion rate increases. In-situ hygroscopic swelling test showed that with and without phosphor, the silicone and composite have almost the same amount of swelling upon moisture absorption. Through the careful experimental analysis, it has confirmed that the previous observation on the permanent swelling for silicone/phosphor composite was false information due to instrument setup issue. The hygroscopic swelling is reversible in absorption/desorption cycle. In strain ramp test, it showed that the moisture has no effect on stress–strain behavior for both silicone and silicone/phosphor samples. But the addition of phosphor enhances the stiffness of material. TMA analysis indicates that the phosphor into silicone does not change the coefficient of thermal expansion in a wide temperature range. In summary, the comprehensive experimental characterization provides a full picture of the effect of humidity and phosphor on the mechanical behavior of silicone/phosphor composite.

References

W.D. van Driel, X. Fan (eds.), Solid state lighting reliability: components to systems (Springer, Berlin, 2012)

W.D. van Driel, X. Fan, G.Q. Zhang (eds.), Solid state lighting reliability part 2: components to systems (Springer, Berlin, 2018)

J.L. Huang, D.S. Golubović, S. Koh, D.G. Yang, X.P. Li, X.J. Fan, G.Q. Zhang, Degradation mechanisms of mid-power white-light LEDs under high temperature-humidity conditions. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 15(2), 220–228 (2015)

J. Huang, D.S. Golubović, S. Koh, D. Yang, X. Li, X.J. Fan, G.Q. Zhang, Rapid degradation of mid-power white-light LEDs in saturated moisture conditions. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 15(4), 478–485 (2015)

G.J. Lu, W.D. van Driel, X.J. Fan, J.J. Fan, C. Qian, G.Q. Zhang, Color shift acceleration on mid-power LED packages. Microelectron. Reliab. 78, 294–298 (2017)

C. Jiang, J.J. Fan, C. Qian, H. Zhang, X.J. Fan, W.L. Guo, G.Q. Zhang, Effects of voids on mechanical and thermal properties of the die attach solder layer used in high-power LED chip-scale packages. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag Manuf. Technol. 99, 1–9 (2018)

M. Meneghini, L. Trevisanello, C. Sanna, G. Mura, M. Vanzi, G. Meneghesso, E. Zanoni, High temperature electro-optical degradation of InGaN/GaN HBLEDs. Microelectron. Reliab. 47(9–11), 1625–1629 (2007)

E. Jung, J.H. Ryu, C.H. Hong, H. Kim, Optical degradation of phosphor-converted white GaN-based light-emitting diodes under electro-thermal stress. J. Electrochem. Soc. 158(2), H132–H136 (2011)

Trevisanello L, De Zuani F, Meneghini M, Trivellin N, Zanoni E, Meneghesso G (2009) Thermally activated degradation and package instabilities of low flux LEDs. In Reliability Physics Symposium, 2009 IEEE International (pp. 98–103). IEEE

X. Luo, B. Wu, S. Liu, Effects of moist environments on LED module reliability. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 10(2), 182–186 (2010)

S.C. Yang, P. Lin, C.P. Wang, S.B. Huang, C.L. Chen, P.F. Chiang, M.T. Chu, Failure and degradation mechanisms of high-power white light emitting diodes. Microelectron. Reliab. 50(7), 959–964 (2010)

P. Singh, C.M. Tan, Degradation physics of high power LEDs in outdoor environment and the role of phosphor in the degradation process. Sci. Rep. 6, 24052 (2016)

C.M. Tan, B.K.E. Chen, G. Xu, Y. Liu, Analysis of humidity effects on the degradation of high-power white LEDs. Microelectron. Reliab. 49(9–11), 1226–1230 (2009)

Velderrain M (2012) Designing low permeability, optical-grade silicone systems: guidelines for choosing a silicone based on transmission rates for barrier applications. In Advances in display technologies II. International Society for Optics and Photonics, Bellingham, p 82800O

C. Damian, E. Espuche, M. Escoubes, Influence of three ageing types (thermal oxidation, radiochemical and hydrolytic ageing) on the structure and gas transport properties of epoxy–amine networks. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 72(3), 447–458 (2001)

V.B. Gupta, L.T. Drzal, M.J. Rich, The physical basis of moisture transport in a cured epoxy resin system. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 30(11), 4467–4493 (1985)

Y.C. Lin, X. Chen, Moisture sorption–desorption–resorption characteristics and its effect on the mechanical behavior of the epoxy system. Polymer 46(25), 11994–12003 (2005)

C.M. Tan, B.K. Chen, X. Li, S.J. Chen, Rapid light output degradation of GaN-based packaged LED in the early stage of humidity test. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 12(1), 44–48 (2012)

S.I. Chan, W.S. Hong, K.T. Kim, Y.G. Yoon, J.H. Han, J.S. Jang, Accelerated life test of high-power white light emitting diodes based on package failure mechanisms. Microelectron. Reliab. 51(9–11), 1806–1809 (2011)

J. Fan, M. Zhang, X. Luo, C. Qian, X. Fan, A. Ji, G. Zhang, Phosphor–silicone interaction effects in high power white light emitting diode packages. J. Mater. Sci. 28(23), 17557–17569 (2017)

Luo X, Fan J, Zhang M, Qian C, Fan X, Zhang G (2017) Degradation mechanism analysis for phosphor/silicone composites aged under high temperature and high humidity condition. In Electronic Packaging Technology (ICEPT), 2017 18th International Conference on pp. 1331–1336. IEEE

J.C. Hsieh, D.T. Lin, C.H. Cheng, Optimization of thermal management by integration of an SCGM, a finite-element method, and an experiment on a high-power LED array. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 58(4), 1141–1148 (2011)

S.Y. Hui, S.N. Li, X.H. Tao, W. Chen, W.M. Ng, A novel passive offline LED driver with long lifetime. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 25(10), 2665–2672 (2010)

M. Yazdan Mehr, A. Bahrami, W.D. van Driel, X.J. Fan, J.L. Davis, G.Q. Zhang, Degradation of optical materials in solid-state lighting systems (Mater. Rev, Int, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/09506608.2019.1565716

Zhang M, Fan J, Qian C, Fan X, Ji A, Zhang G (2016) Analysis of photoluminescence mechanisms and thermal quenching effects for multicolor phosphor films used in high color rendering white LEDs. In Electronic Packaging Technology (ICEPT), 2016 17th International Conference on p 334–340. IEEE

Wang Z, Fan J, Liu J, Hu A, Qian C, Fan X, Zhang G (2018) Study of ultraviolet assisted cure mechanism of the phosphor/silicone composites used in White LEDs. In 2018 19th International Conference on Electronic Packaging Technology (ICEPT) p 525–530. IEEE

I. Khalilullah, T. Reza, L.B. Chen, M. Placette, M.H.A.K.M. Mazumder, J. Zhou, J.J. Fan, C. Qian, G.Q. Zhang, X.J. Fan, In-situ characterization of moisture absorption and hygroscopic swelling of silicone/phosphor composite film and epoxy mold compound in LED packaging. Microelectron. Reliab. 84, 208–214 (2018)

Y. Pan, F. Zhu, J. Fan, J. Tao, X. Lin, F. Wang, L. Shi, Investigation of mechanical properties of silicone/phosphor composite used in light emitting diodes package. Polymers 10(2), 195 (2018)

J. Fan, Z. Wang, Z. Deng, X. Fan, G. Zhang, High moisture accelerated mechanical behavior degradation of phosphor/silicone composites used in white light-emitting diodes. Polymers 11(8), 1277 (2019)

H. Tang, H. Ye, C.K.Y. Wong, S.Y.Y. Leung, J. Fan, X. Chen, X. Fan, G. Zhang, Overdriving reliability of chip scale packaged LEDs: quantitatively analyzing the impact of component. Microelectron. Reliab. 78, 197–204 (2017)

X.J. Fan, S.W.R. Lee, Q. Han, Experimental investigations and model study of moisture behaviors in polymeric materials. Microelectron. Reliab. 49, 861–871 (2009)

X.J. Fan, E. Suhir (eds.), Moisture sensitivity of plastic packages of IC devices (Springer, New York, 2010)

Acknowledgement

Jiajie Fan would like to acknowledge the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51805147, 61673037).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoque, M.A., Bradley, R.K., Fan, J. et al. Effects of humidity and phosphor on silicone/phosphor composite in white light-emitting diode package. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 30, 20471–20478 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-019-02393-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-019-02393-8