Abstract

Chromogenic thin films are crucial building blocks in smart windows to modulate the flux of visible light and heat radiation into buildings. Electrochromic materials such as tungsten oxide are well established in those devices. Sputter deposition offers a well-suited method for the production of such layers, which can also be used on an industrial scale. Tungsten oxide films were prepared by means of reactive ion-beam sputter deposition. The choice of distinct gas mixtures as well as the growth temperature during the sputtering process allows to tune the properties of the resulting layers. Especially, the variation in the growth temperatures was found to have an impact on the structure of the resulting samples and, as a consequence, on their optical and electrochemical properties. By specific choice of the reactive gas, the deposition of colorless transparent as well as blue films of different composition is possible. The optical transmittance in the visible spectral range was up to 75% for as-deposited oxygen-rich layers. Additionally, hydrogen-doped tungsten oxide samples were grown. Superior electrochromic switching was observed for H\(^{+}\)-doped layers, probably by some kind of preconditioning. This resulted in a value for the standardized optical coloration efficiency of 26.5 cm\(^{2}\)/C.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Because of the global climate change, energy-saving and sustainable technologies are becoming more and more important. Therefore, the demands on technologies for the conversion, storage and use of renewable energies are constantly growing [1]. The building sector plays an important role in terms of energy saving potential. For example, this sector consumes 23% of global primary energy and 30% of global electricity demand [2]. The further development of technologies that enable energy to be used efficiently and economically is, therefore, of foremost interest. In particular, the class of so-called smart windows offers an approach to save energy in the building sector by efficiently regulating incident light [3]. This can be achieved by the use of electrochromic (EC) thin films. Electrochromism denotes the reversible change of optical absorbance driven by an externally applied voltage; thus, EC materials allow for the modulation of the incident light.

The mostly studied EC materials include conjugated conducting polymers, transition metal oxides as well as metal coordination complexes [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Due to their diversity in composition and structure as well as their superior performance, electrochromism based on thin film transition metal oxides has become increasingly important in the last decade. Exemplarily, there has been significant progress in terms of new materials [10,11,12,13,14,15] as well as novel designs and concepts [14, 16,17,18,19]. Among the various transition metal oxides, tungsten oxide is the most intensively studied material and has been established as material of choice in this field, especially with regard to its extraordinary EC properties like high color efficiencies, high cyclability and high environmental stability, among others [20, 21]. The underlying process of electrochromism is widely accepted as a result of simultaneous injection/extraction of electrons and cations [22] and complies with the following reaction

where x describes the number of incorporated ions and electrons, respectively. The type of ions, such as H\(^{+}\), Li\(^{+}\) or Na\(^{+}\), is represented by M\(^{+}\). The intercalation reaction of electrons and ions into the film can cause a reduction of the W\(^{6+}\)-states to W\(^{5+}\)- or W\(^{4+}\)-states [6]. This leads to a modification of the electronic structure of the material, whereby photons in the visible range of the electromagnetic spectrum can be absorbed. Simultaneously, the color impression of the tungsten oxide layer changes. The untreated tungsten oxide layer appears colorless transparent, whereas a blue coloration occurs upon electrochemical reduction with simultaneous incorporation of charge-neutralizing ions. A reversal of this process, i.e., the removal of ions (deintercalation), results in a decolorization of the layer.

Tungsten and its oxides are, further, of great interest because of their high availability, low price factor and high chemical stability. The special properties result from the different level of oxygen deficit in phases of WO\(_x\), which were investigated by Magnéli and are thus known as Magnéli phases [23, 24]. In addition to their EC characteristics, tungsten oxides can be successfully applied in, e.g., gas sensors, catalysts or electrode materials in lithium-ion batteries [25,26,27,28,29].

The EC properties of tungsten oxide layers depend on the composition, the crystal structure and the morphology [8, 30,31,32]. Compared to crystalline films, amorphous WO\(_3\) exhibits more rapid coloration and improved efficiency but inferior stability [30, 31]. Hence, using low-dimensional nanostructures has been proven effective to achieve faster switching, increased reversibility and enhanced durability [30, 32]. This is due to the higher surface accessibility and shorter diffusion path length versus the bulk counterpart [30]. The film characteristics are strongly dependent on the growth technique. A multitude of different techniques were used, metal organic chemical vapor deposition [33], the sol–gel process [34, 35], pulsed laser deposition [36,37,38] or sputter deposition [39, 40], among others. Especially, sputter-deposited coatings show some intrinsic advantages, such as a strong layer adhesion, a constant film thickness of homogeneous structure, high growth rates and a high degree of reproducibility, which trigger their dominance in industrial scale. Nevertheless, there are drawbacks in conventional setups such as the contact between the substrate and the plasma during deposition. Therefore, the temperature of the substrate surface can rise significantly. In this article, ion-beam sputter deposition (IBSD) was used for the synthesis of tungsten oxide films to achieve a more precise control of the sample temperature and, thus, the layer properties [41]. This favors the deposition of amorphous tungsten oxide films, since otherwise plasma irradiation of the substrate surface raises the temperature, promotes atom migration and, as a consequence, can lead to crystallization of the material. For the same reason, films already present on the substrate, e.g., for stack preparation, can be spared the harsh conditions of a contact to the plasma. Besides, smooth and compact surfaces can be realized, which is in contrast to conventionally sputtered thin films being rather rough and porous. The basic characteristics of ion-beam sputtered tungsten oxide coatings as well as the possibilities to improve the coating properties due to variation in synthesis parameters like gas mixture and growth temperature will be described. As-grown samples are investigated by means of their optical, compositional and EC characteristics.

Experimental

Tungsten oxide (WOx) films were prepared by ion-beam sputter deposition. The sputtering setup consists of the vessel of radio frequency (RF) ion source, which incorporates the plasma, and the main process chamber in which the sputter target and the substrate are mounted. The ion beam extracted from the ion source is directed onto the target, where the material of the target is atomized. In comparison with conventional sputtering systems such as direct current (DC) or RF sputtering, in IBSD systems obviously there is no direct contact between plasma and substrate and, as a consequence, the temperature of the substrate surface will not rise significantly. Further details concerning the IBSD setup can be found in reference [41].

The films were deposited from a metallic tungsten target of Kurt J. Lesker Company (purity of 99.95%) by reactive sputtering in an argon–oxygen mixture. For some layers, hydrogen was used as additional reactive gas to deposit hydrogen-doped films. All gases got a purity of 99.999%. A fixed argon flux of 2 sccm was used for all samples. The ion source was operated at an RF power of 220 W. To influence the degree of crystallization of the layers, films were deposited under ambient as well as elevated growth temperatures. K GlassTM coated with fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) with a thickness of 300 nm was used as substrate in order to establish an electrical contact for electrochemical measurements.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was carried out with a diffractometer type D5000 of Siemens company using the Cu-K\(_{\alpha }\) emission line. The measurements were taken in Bragg–Brentano geometry with a rate of 2\(^\circ\)/min. A Lambda 900 spectrometer from PerkinElmer Instruments was used to measure the optical properties of the layers. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) were conducted to analyze the crystallite surface structure. The SEM measurements were taken using a Zeiss–Merlin setup. For the AFM investigations in air, a Smart SPM 1000 (AIST-NT) was used, utilizing NanoWorld Pointprobe SEIHR-20 AFM probes designed for non-contact mode imaging. Raman spectroscopy was carried out with a 633 nm laser in a range between 100 and 1500 cm\(^{-1}\). Additionally, a colored sample was examined for analysis by Raman spectroscopy. This sample was intercalated with Li\(^{+}\)-ions by means of a cyclic voltammetry measurement. As electrolyte, a 1 M solved lithium perchlorate (LiClO\(_{4}\)) in propylene carbonate was used. The potential was varied with a rate of 10 mV/s until − 0.7 V were reached. Further details about the electrochemical measurement setup are described below. To gain more precise information about the composition of the film and the chemical bonds, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted. The PHI VersaProbe system utilizes an Al anode (Al-K\(_{\alpha }\) = 1486.6 eV). Measurements were taken with a source angle of 45\(^\circ\) and with charge neutralization on the sample surface. All resulting spectra were referenced to the carbon signal (C 1s) at 284.8 eV. Depth profiles of the films were studied via in situ argon ion etching with an acceleration voltage of 0.5 or 1 kV. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra were measured at 4 K with a microwave power of 201,17 mW and a microwave frequency of 9.49 GHz. For these investigations, tungsten oxide was deposited on polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) foil. The use of PTFE foil allows to remove the deposited layer from the substrate so that the remaining powder can be examined in a quartz ampule. Selected samples were examined for their EC properties. Cyclic voltammetry was conducted in an IviumStat potentiostat between − 0.7 and 1.5 V with potential sweeps of 10 mV/s. The electrochemical half-cell consisted of a platinum wire (counter electrode), a leak-free Ag/AgCl reference electrode and a tungsten oxide layer (working electrode). The electrolyte used was 0.1 M sulfuric acid. During the cyclic voltammetry measurements, UV–Vis spectroscopy was simultaneously performed with a TEC5 spectrometer at the reversal points of the potential. These reversal points can be considered as the state of the intercalated and deintercalated layer. Due to the sweep rate of the potential, this would result in a switching time of 220 s. For the classification of the optical switching performance of the investigated layers, the electrochromic characteristics listed in the following were used. For building glazing, the European standard EN 4102 [42] serves as the basis for calculating the optical characteristics. The standardized transmission T\(_{{\rm vis}}\) is of special importance with respect to the use as window coating. This takes into consideration the spectral sensitivity of the human eye V(\(\lambda\)). The corresponding values can be found in reference [43]. Here the spectral range from 380 to 780 nm is examined, with the strongest weighting at about 555 nm. Furthermore, the intensity distribution of the incident light is taken into account. For the calculation, the CIE (International Commission on Illumination) Standard Illuminant D65 is used as the reference light source. This can be found in the ISO 11664-2 standard [44]. From these values, the standardized transmission T\(_{{\rm vis}}\) is calculated as follows:

This results in the standardized optical coloration efficiency:

in which the bleached (b) and colored (c) state of the standardized transmission and the charge involved is taken into account.

Tungsten oxide thin films were grown by ion-beam sputter deposition, a less common sputtering variant. We showed the possibility of influencing technologically relevant samples characteristics by using different preparation parameters (e.g., gas mixture or growth temperature). This allows to tune the elemental composition, optical properties or to influence the structure and the degree of crystallization in the resulting thin films. Variation in these properties allows for a positive selection of parameters guaranteeing layers with beneficial EC characteristics. Exemplarily, layers of a significantly altered morphology and a much more compact structure can be produced. Additional in operando doping with hydrogen allows to further optimize the cycling behavior. The high reproducibility as well as the high purity of IBSD-grown layers render ion-beam sputter deposition a suitable candidate for growth of tungsten oxide and, most likely, other chromogenic materials.

Results and discussion

Figure 1a shows the transmittance in dependence on wavelength for pristine tungsten oxide films deposited at room temperature and varied O\(_2\) flux up to 10 sccm. The corresponding photographs are shown as well with the O\(_2\) flux during the deposition decreasing from left to right. Obviously, layers produced under high O\(_2\) flux are highly transparent. Below a certain threshold in the O\(_2\) flux, however, a blue coloration of the layers occurs. This points at partial presence of W\(^{5+}\)- and W\(^{4+}\)-states and, hence, an oxygen deficit of the samples.

Taking a look at the optical transmission of the layers in the spectral range between 300 and 650 nm, this tendency is also well established. As opposed a measurement of the substrate (FTO layer on glass) for which absorption occurs up to 310 nm, the films of tungsten oxide absorb up to about 370 nm, well in line with their colored appearance. Oxygen-rich tungsten oxide samples deposited with an O\(_2\) flux of 6 sccm and above reach a transmittance in the visible spectral range of up to 75%, close to the 80% of the substrate. The general transmission profile of these samples is comparable. However, for samples produced under lower O\(_2\) flux a decrease in the measured transmittance can be seen. In particular, an O\(_2\) flux of 5.15 sccm was found to be the lowest O\(_2\) flux which reproducibly yields widely colorless transparent samples. Additionally, the sample shows the highest transmittance for the violet and blue spectral range. Samples grown with higher oxygen deficit (deposited at an O\(_2\) flux of 5 sccm and less) show a bluish color impression accompanied by a shift in the onset of absorption toward higher wavelengths and increased absorption in the longer wavelength range. Figure 1b depicts the transmittance series for films prepared at a constant substrate temperature of 400 \(^\circ\)C. Again, the upper part of the figure shows photographs of the samples. In general, the transmission measurements of these samples also show the decrease in the transmittance for oxygen-poor samples as well as the shift of the onset of absorption. Compared to the previous series, however, the O\(_2\) flux below which blue coloring occurs shifts to higher values. This is clearly visible for the sample deposited under an O\(_2\) flux of 5.15 sccm. Here, the sample grown at a growth temperature of 400 °C exhibits a dark blue color impression, while the one deposited at RT was colorless. Thus, different compositions can be obtained for samples deposited under the same O\(_2\) flux but at different growth temperatures. Consequently, the different color impression allows an assessment of the composition of the films. This is in accordance with the literature, where a ratio of O/W > 2.5 is reported to show a transparent widely colorless aspect, while for O/W \(\simeq\) 2.5 a bluish color and for O/W < 2.5 a metallic character of the films was observed [45]. It should be noted that the coloration discussed in the previous paragraph is not to be mistaken for the coloration which results from de- and intercalation processes, cf. Fig. 1c.

Optical transmittance curves and photographs of tungsten oxide samples IBSD-grown at room temperature (a) and 400 \(^\circ\)C (b) under variation of the O\(_2\) flux superimposed to the fixed 2 sccm of Ar. The bluish coloration of some samples stems from tungsten excess and is not to be confused with the bluish coloration of tungsten oxide when reduced in an electrochemical cell at a potential of − 0.7 V versus Ag/AgCl (intercalated state) or 1.5 V versus Ag/AgCl (deintercalated state) in contact to 0.1 M sulfuric acid (c)

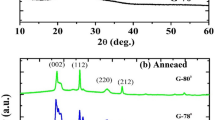

Figure 2a shows X-ray diffractograms of samples deposited under different growth temperatures and with a varying composition. Herein, the films grown at RT without additional heating of the substrate do not reveal any reflexes besides those to be assigned of SnO\(_2\) (marked in the upper scale [46]), which belong to the FTO substrate. Thus, no crystalline WO\(_3\) was grown at room temperature. In order to be able to produce crystalline samples, an increase in the growth temperature is necessary. Accordingly, the samples deposited at a growth temperature of 400 \(^\circ\)C show reflexes of WO\(_3\) phases. A dominant signal arises in the region of 20\(^\circ\)–25\(^\circ\). However, since the reflection appears rather broad, a clear assignment to a single lattice plane is not possible. A comparison with the predicted reflexes for monoclinic WO\(_3\) (blue squares in Fig. 2a) indicates that a superposition of (002), (020) and (200) reflexes might be present [47]. It should be noted that these signals might be as well assigned to the presence of a triclinic phase [48]. Furthermore, Fig. 2a comprises an additional marked area at 45\(^\circ\)–55\(^\circ\) with two broad signals for which a clear assignment is not possible and a superposition of different reflexes is most likely. Additionally, around the (101) reflection of FTO further low-intensity signals seem to be overlayed, apparent in a significant broadening of the FTO-related signal. Again, reflections of the monoclinic tungsten oxide are the obvious cause. In conclusion, it is seen that polycrystalline tungsten oxide films were prepared in the 400 \(^\circ\)C-series and an influence of the chosen O\(_2\) flux during the deposition can be seen. The highest degree of crystallinity is observed for the sample sputtered at an O\(_2\) flux of 8 sccm.

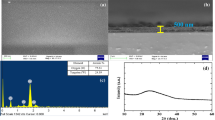

X-ray diffractograms of samples of varying composition, deposited at RT (green) or at 400 \(^\circ\)C (red) compared to reference values of SnO\(_2\) (red bars on top) and monoclinic WO\(_3\) (shown by blue squares) (a). SEM images of films deposited under different O\(_2\) flux at RT (b)–(e) or at 400 \(^\circ\)C, cf. (f) and AFM images of samples, deposited at room temperature under a moderate O\(_2\) flux of 5.15 sccm (g) and under oxygen-poor conditions (h). Compared to the surface of a sample grown at 400 \(^\circ\)C (i), the surface roughness is significantly smoother

The morphology of the layers was investigated in SEM and AFM measurements. Smooth and compact films of WO\(_3\) were realized. In Fig. 2b–e, SEM images of films deposited under different O\(_2\) flux and without additional heating of the substrate during deposition are shown. For O\(_2\) flux up to 8 sccm, compact films without any pronounced grain structure are formed. The sample deposited at an O\(_2\) flux of 10 sccm shows a similar morphology with some protrusions of 0.2–0.3 \(\upmu\)m size without, however, any distinct orientation, in a line with the findings of X-ray diffraction. In Fig. 2f, the influence of the growth temperature on the surface structure at a fixed O\(_2\) flux of 5.15 sccm during deposition is shown. A morphology different from the samples shown in Fig. 2b–e should be emphasized. Unlike those samples, the film in Fig. 2f shows well-separated grains with a size up to 0.3 \(\upmu\)m but less pronounced crystal facets. In Fig. 2g, the surface of a sample deposited at RT and a moderate O\(_2\) flux of 5.15 sccm is shown as analyzed by AFM. Individual grains of about 0.2 \(\upmu\)m size appear interconnected without sharply defined grain boundaries. The root-mean-square surface roughness was determined to be around 9 nm. In comparison, Fig. 2h shows the morphology of a sample synthesized at RT under oxygen-poor conditions. Again, no sharply defined grains are recognizable. However, the grains seem to be a bit more extended. The determined roughness of the surface is approximately 7 nm. At an increased deposition temperature of 400 \(^\circ\)C, larger round-shaped grains of about 0.5 \(\upmu\)m lateral expansion were obtained, cf. Fig. 2i, leading to an increased roughness of around 20 nm, much higher than for the unheated samples.

Raman spectra of tungsten oxide thin films deposited at different growth temperatures and O\(_2\) fluxes as well as a spectrum of a Li\(^{+}\)-intercalated sample (blue) with band assignments indicated as vertical lines. Bluish WO\(_x\) layers display a higher intensity especially in the range of about 330 and 450 cm\(^{-1}\) attributed to W\(^{5+}\)–O and W\(^{5+}\)=O bonds, whereas in colorless transparent samples W\(^{6+}\)-related Raman modes dominate

Figure 3 shows Raman spectra obtained for samples with different optical impression (colorless transparent or blue) as well as for samples synthesized at different growth temperature. The amorphous samples deposited under an O\(_2\) flux \(\ge\) 5.15 sccm at room temperature show two broad signals of higher intensity in the region of 770 and 950 cm\(^{-1}\). According to the literature, the first one is due to the W\(^{6+}\)–O-bond [49] and is caused by a superposition of the two strongest peaks at 719 and 808 cm\(^{-1}\) [50]. The second peak resulting from the W\(^{6+}\)=O stretching mode of terminal oxygen atoms [51]. With respect to amorphous tungsten oxide, the basic structure can be described by the formation of WO\(_6\)-octahedra. These consist of short W\(^{6+}\)=O-bonds and longer W\(^{6+}\)–O-bonds leading to clusters of deformed octahedra, where the W\(^{6+}\)=O-bonds are expected at the outermost surface of the clusters [51, 52]. The bluish samples (oxygen poor and Li\(^{+}\)-intercalated) yield spectra with a weaker intensity in the region of the W\(^{6+}\)-states. The colorless transparent sample (deposited under an O\(_2\) flux of 5.15 sccm) shows a significant increase in intensity in the range of about 330–450 cm\(^{-1}\) after the intercalation of Li\(^{+}\)-ions. These signals are assigned to the W\(^{5+}\)–O and W\(^{5+}\)=O bonds [52]. Following the model of small polaron transitions by Schirmer et al. [53], the W\(^{5+}\) states contribute to the mechanism that leads to optical absorption. The Raman measurements of the films therefore give an indication of the presence of these states in the stained samples.

Crystalline WO\(_x\) films showed three Raman signals with a high intensity at about 270 cm\(^{-1}\), 690 cm\(^{-1}\) and 810 cm\(^{-1}\), slightly shifted relative to the reported positions 275 cm\(^{-1}\), 719 cm\(^{-1}\) and 808 cm\(^{-1}\) [49, 50]. Beside those modes, both samples show a higher intensity in the signal around 330 cm\(^{-1}\). At this wave number, Ozkan et al. mention the existence of a mode which occurs for crystalline samples [54]. In contrast to the amorphous films, the mode at 950 cm\(^{-1}\) only appears as a weak signal and predominantly for the film prepared at low O\(_2\) flux. Tentatively, we assign this to a removal of doubly bonded W\(^{6+}\) for crystalline tungsten oxide. Thus, the intensity of the 950 cm\(^{-1}\) Raman mode might serve as a measure of the degree of crystallization. In conclusion, a better crystallization is observed for the oxygen-rich sample.

EPR spectra of a transparent (deposited with an O\(_2\) flux of 5.5 sccm at RT) as well as a bluish sample (deposited with an O\(_2\) flux of 3 sccm at RT) (a). W\(^{5+}\) oxidation states are only present for blue samples. O 1s (b, c) and W 4f core level spectra (d, e) measured by XPS at the surface of a film prepared at RT and with an O\(_2\) flux of 10 sccm (b, d) as well as after etching the surface for 300 s at 1 kV (c, e). Features attributed to oxidation states W\(^{4+}\) and W\(^{5+}\) arise after the etching procedure. Calculated W/O-ratio (f) of the film surface or during etching at acceleration voltages of 0.5 kV (open triangles) or 1 kV (solid triangles) for samples prepared at different O\(_2\) flux at RT compared to a film prepared at 400 \(^\circ\)C. Corresponding W\(^{6+}\)/(W\(^{5+}\) + W\(^{4+}\)) ratios (g) resulting from the depth profile of the oxygen-rich and crystalline samples

Figure 4a presents the EPR spectra of a colorless transparent as well as a bluish sample compared to a PTFE film as reference. For all examined samples, a signal can be seen at approximately H\(_1\) = 3370 G and H\(_2\) = 3388 G. For this, a Landé factor of \(g=2.00\) results which is characteristic for free electrons. Two more resonances are seen for the bluish sample at H\(_{3}\) = 3830 G and H\(_4\) = 4412 G. For those signals, Landé factors of \(g=1.77\) and \(g=1.54\) are calculated. These values are in good agreement with those given in the literature [51], assigned to W\(^{5+}\) ions in colored tungsten oxide films confirming the presence of W\(^{5+}\) states in our bluish samples.

XPS measurements on an oxygen-rich sample (deposited with an O\(_2\) flux of 10 sccm) show an O 1s signal consisting of two contributions at binding energies of 530.3 and 531.6 eV, cf. Fig. 4b. The former has been associated with O\(^{2-}\) and W\(^{6+}\) ions, whereas the latter arises from contamination at the surface, such as hydroxyl groups or oxygen as part of carbon-related impurities.

Figure 4c shows the O 1s signal after an etching time of 300 s upon which additional signals representing oxygen bound to W\(^{5+}\) (signal at 530.8 eV) and W\(^{4+}\) (signal at 530.6 eV). A detailed spectrum of the W 4f core level at the surface is given in Fig. 4d consisting of W 4\({f}_{7/2}\) (at 35.4 eV) and W 4\({f}_{5/2}\) (at 37.5 eV), both associated with the oxidation state W\(^{6+}\). After an etching time of 300 s (Fig. 4e) further contributions have to be considered pointing at the presence of W\(^{5+}\) and W\(^{4+}\) oxidation states, which confirm the assignment in the corresponding O 1s region. Obviously, the surface of the sample only contains W\(^{6+}\) oxidation states. With increasing depth of layer, however, increasingly W\(^{5+}\) and W\(^{4+}\) oxidation states are present. Due to the fact that the sample considered is an oxygen-rich, colorless transparent tungsten oxide layer, a high proportion of W\(^{5+}\) and W\(^{4+}\) states, however, is unlikely. Rather, a preferential oxygen etching during the depth profiling is assumed, which does not allow an exact determination of the concentration ratio by means of XPS. Hence, we discuss the data in terms of a trend of the W/O-ratio within the series. Figure 4f shows the W/O-ratio of an oxygen-poor (blue film), a slightly substoichiometric (deposited under 5.15 sccm and at RT or with a growth temperature of 400 \(^\circ\)C) and an oxygen-rich sample (colorless transparent film), presented in dependence of the O\(_2\) flux during deposition. In each case, the measurement of the surface (squares) and after an etching step (triangles) is shown. The surface of the sample deposited under the lowest O\(_2\) flux provides a nearly stoichiometric W/O ratio of about 0.31. However, due to the low oxygen content during the deposition process, an oxygen deficit can be assumed and the resulting ratio is due to surface contamination of the layer. In contrast, an etching time for 300 s with 1 kV acceleration voltages results in a W/O ratio of about 0.58. However, such a strong substoichiometry of oxygen is more than doubtful since for this ratio, a metallic character would be expected. Comparable trends are evident for the two samples prepared without growth temperatures and with an O\(_2\) flux of 5.15 and 10 sccm. As expected, the examination of the surfaces shows that a higher selected O\(_2\) flux during the deposition process counteracts the deficient incorporation of O\(_2\). However, on the basis of the series shown, only a tendency of the decreasing ratio can be seen. It remains to be mentioned that this results in a slight superstoichiometry of oxygen. Again, it is very likely that this ratio is due to an oxygen-rich contamination of the sample surface from ambient air.

Compared to the measurements of the strongly oxygen-deficient sample, the depth measurements of the other two amorphous layers show comparable trends. Once more, conditions which would correspond to a metallic character have to be determined. A comparison of the trend of the conditions within the data points for the depth profiles provides an analogy in the development of the surface measurements of the samples. For the depth measurements, the W/O ratios are displaced to a higher W/O ratio. Although a direct influence of the oxygen content depending on the chosen O\(_2\) flux during deposition can be seen, a quantitative analysis is hindered. To determine the influence of preferential etching during depth profiling, detailed XPS-measurements were taken under lower acceleration voltages of 0.5 kV for the argon ions. Measurements were taken after an etching time of 180, 360 and 540 s for an oxygen-rich sample and are represented in Fig. 4f as open triangles. After an etching time of 180 s, only a slight substoichiometry with an W/O ratio of 0.34 is found. Further etching resulted in a ratio of 0.4. Despite enhanced substoichiometry of oxygen in the sample for further etching steps, the W/O ratio remains below 0.47, which was measured after an etching time of 300 s at an acceleration voltage of 1 kV. The measurements suggest a less pronounced preferential etching of oxygen at this lower acceleration voltage of 0.5 kV, however, presumably also reduced erosion rates of the layer.

Furthermore, the figure shows the results of XPS measurements on a crystalline film with blue color (deposited under an O\(_2\) flux of 5.15 sccm and at a growth temperature of 400 \(^\circ\)C, red symbols). Compared to the above mentioned samples, a clear deviation of the O/W ratio of 0.54 at the surface is obvious (red square). Although understoichiometry can be expected due to the coloration, the result appears to be too strongly understoichiometric, as the metallic character of the layer can be assumed for this ratio. Simultaneously, it can be observed that the influence of preferential oxygen sputtering is less pronounced here due to the less altered W/O ratio of 0.62 for depth measurement (red triangle).

Figure 4g illustrates the ratio of the oxidation states W\(^{6+}\)/(W\(^{5+}\) + W\(^{4+}\)) for the measurements already discussed in Fig. 4f. Only the thin film produced under the highest O\(_2\) flux and the crystalline sample are shown. For both samples, the measurement of the surface and the depth measurement after an etching time of 300 s (with 1 kV acceleration voltages) is depicted. For the oxygen-rich sample, the additional depth profile was measured with the lower configuration of the acceleration voltage of 0.5 kV and after time steps of 180, 360 and 540 s. The corresponding W\(^{6+}\)/(W\(^{5+}\) + W\(^{4+}\)) ratio decreases during depth profiling. This is due to the preferential removal of oxygen. With increasing depth, the ratio saturates. We tentatively explain this as follows: At the beginning of the measurement (within the first 180 s), the W\(^{6+}\) oxidation states are reduced to W\(^{5+}\) oxidation states. Thereafter, in addition to the reduction of W\(^{6+}\) oxidation levels also W\(^{5+}\) oxidation states are reduced and thus the presence of W\(^{4+}\) oxidation levels increases. Thus, compared to the first 180 s of the etching time, the change of the W\(^{6+}\)/(W\(^{5+}\) + W\(^{4+}\)) ratio decreases again. In contrast, it is clear for the crystalline sample that the determined oxidation states during the measurement result in a nearly non-changing ratio. Thus, the crystalline layer shows, compared to the results of the amorphous samples, a generally deviating behavior with respect to the XPS measurements. The reason for this could be the presence of more stable bonds to oxygen or the concentration ratios being maintained despite etching during the data acquisition.

The IBSD grown amorphous as well as crystalline tungsten oxide layers with varying ratios of tungsten oxidation states were examined by means of cyclic voltammetry regarding their EC properties. Figure 5a shows nine cycles of the amorphous, colorless transparent sample deposited under an oxygen flux of 5.15 sccm. For the reduction in the film, accompanied by H\(^{+}\)-intercalation (eq. 1), the current densities become increasingly negative starting at a voltage of about 0.1 V and rapidly becoming more negative at about − 0.48 V. At the reversal point of − 0.7 V, the recorded current densities finally reach a maximum negative value of about 0.14 \(\hbox {mA}/\hbox {cm}^{2}\). Peaks for individual reduction reactions (such as W\(^{6+}\) \(\rightarrow\) W\(^{5+}\) or W\(^{5+}\) \(\rightarrow\) W\(^{4+}\)) cannot be assigned. Upon reversal of the voltage sweep, only a broad oxidation peak is seen. Accordingly, the assignment of single oxidation steps (like W\(^{4+}\) \(\rightarrow\) W\(^{5+}\) or W\(^{5+}\) \(\rightarrow\) W\(^{6+}\)) is not possible. The maximum current densities of about \(2.4\times 10^{-2}\,\hbox {mA}/{\hbox {cm}^{2}}\) occur around a voltage of − 0.45 V. Toward higher voltages, the current densities decay quite quickly, indicating complete oxidation of the film. Based on the continuously increasing current densities upon successive cycling of the potential, the enclosed area of the voltammogram slightly increases with the increasing number of cycles, which suggests that an increasing charge is involved in the process. Consequently, the film is reduced and re-oxidized to an increasing extent.

Cyclic voltammetry (cycles proceeding from lighter to darker color in the plots) for an amorphous (a) and a crystalline sample (c) with the corresponding optical transmission spectra (b) and (d), respectively, measured at the reversal points − 0.7 to 1.5 V. The calculated optical impression at the reversal points [55] is shown above the transmission spectra (b, d)

The optical transmission of the sample at each reversal point of the potential, cf. Fig. 5b, represents the bleached (at + 1.5 V) and colored (at − 0.7 V) states. Rather small differences of transmission of the bleached and colored state can be seen, however, reversibly within every single cycle and increases with the increasing number of cycles, caused by increasing coloration. This is underlined by the optical color impression of the film in the different (de)intercalated conditions at the reversal points (− 0.7 V or 1.5 V) shown in Fig. 5b.

Figure 5c shows nine cycles of cyclic voltammetry on a crystalline WO\(_x\) sample. The characteristics of the first cycle differ slightly from those of the subsequent cycles, in that the current density during reduction/intercalation of the first cycle increases more steeply than for the remaining cycles and two distinct features at approximately − 0.3 and − 0.1 V occur re-oxidation/deintercalation. As for the amorphous film, the charge increases upon successive cycling.

Figure 5d shows the transmittance and the optical color impression for subsequent cycles. Obviously, the switching process is not completely reversible. Particularly in the near infrared range, a proceeding drop in transmittance occurs from cycle to cycle.

Both types of samples can be reduced/intercalated and re-oxidized/ deintercalated. For the crystalline sample, a certain irreversibility reveals caused by incomplete deintercalation. The irreversible switching behavior could be caused by a sweep rate of the potential which was too fast. The more densely packed atomic structure in crystalline samples could hinder the ion diffusion. As already mentioned in Sect. 1, an extended response time of the coloration in crystalline samples is a well-known phenomenon [30]. Thus, inserting protons gradually change the as-grown crystalline samples.

To suppress such behavior, an additional series of samples was grown in which hydrogen was used as additional reactive gas in the sputtering process. It is expected that hydrogen is incorporated into the deposited layers and influences the structure and, consequently, to show an influence on the EC properties.

Figure 6a illustrates photographs of the samples (above) as well as the corresponding optical transmission measurements (below). For this series, the additional H\(_2\) flux was varied between 0.5 and 2 sccm, whereas the O\(_2\) flux of 5.15 sccm and the growth temperature (RT) were fixed. Layers which were produced with a hydrogen flux of 0.8 sccm or above show a blue coloration indicative of partial reduction. Increasing the H\(_2\) flux even further strengthens the coloring. The absorption edge of all samples starts at about 320 nm. In order to prevent coloration of samples due to the deficient oxygen content, the O\(_2\) flux was increased to 7 sccm. At the same time, an H\(_2\) flux of 10 sccm was chosen to achieve a high doping. This resulted in a colorless transparent layer.

Optical transmission spectra and photographs (top) of tungsten oxide films deposited at RT with fluxes of 2 sccm Ar and 5.15 sccm O\(_2\), and increasing additional flux of H\(_2\) (a). Cyclic voltammetry (b) as well as optical transmission at the reversal points (c) measured at a colorless transparent hydrogen-doped WO\(_x\) film (fluxes of 2 sccm Ar, 7 sccm O\(_2\) and 10 sccm H\(_2\)) with the color impression of the film in the current switching state (above the graph)

Figure 6b shows four cyclic voltammetry cycles of such a hydrogen-doped sample. Essentially, the voltammograms resemble those shown in Fig. 5a. However, the coloration current density is more negative. Quite constant current density and charge are observed for all cycles. The transmittance spectra recorded simultaneously and the optical color impression of the layer, cf. Fig. 6c, show a widely reversible switching process of high contrast in transmission. For the reduced/intercalated layer, the transmittance reversibly drops to values as low as 50% at 800 nm as opposed to the irreversible characteristics of the samples reported in Fig. 5. It can, therefore, be proven that hydrogen, used as an additional reactive gas in the manufacturing process, yields samples which have significantly improved EC switching properties.

To compare the electrochromic characteristics of IBSD grown films, Table 1 summarizes the results of an undoped tungsten oxide sample (measurement is shown in Fig. 5a, b) as well as the high doped sample from Fig. 6b, c. A comparison shows a clear increase in the change of the standardized transmission at visible range. For the H\(_2\)-doped sample, this change is about twice as large. At the same time, compared to the undoped sample, a larger charge quantity of 2.3 mC/cm\(^2\) is involved within the cycle under consideration. An improved value of 26.5 cm\(^2\)/C is also obtained for the standardized optical coloration efficiency of the doped sample.

Conclusion

Tungsten oxide thin films were grown by ion-beam sputter deposition, a less common sputtering variant. We showed the possibility of influencing technologically relevant samples characteristics by using different preparation parameters (e.g., gas mixture or growth temperature). This allows to tune the elemental composition, optical properties or to influence the structure and the degree of crystallization in the resulting thin films. Variation in these properties allows for a positive selection of parameters guaranteeing layers with beneficial EC characteristics. Exemplarily, layers of a significantly altered morphology and a much more compact structure can be produced. Additional in operando doping with hydrogen allows to further optimize the cycling behavior. The high reproducibility as well as the high purity of IBSD-grown layers render ion-beam sputter deposition a suitable candidate for growth of tungsten oxide and, most likely, other chromogenic materials.

References

Ahmadi MH, Ghazvini M, Nazari MA, Ahmadi MA, Pourfayaz F, Lorenzini G, Ming T (2019) Renewable energy harvesting with the application of nanotechnology: a review. Int J Energy Res 43:1387–1410

Ürge-Vorsatz D, Cabeza LF, Serrano S, Barreneche C, Petrichenko K (2015) Heating and cooling energy trends and drivers in buildings. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 41:85–98

Tällberg R, Jelle BP, Loonen R, Gao T, Hamdy M (2019) Comparison of the energy saving potential of adaptive and controllable smart windows: a state-of-the-art review and simulation studies of thermochromic, photochromic and electrochromic technologies. Sol Energy Mater Sol C 200:109828. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOLMAT.2019.02.041

Green S, Backholm J, Georén P, Granqvist CG, Niklasson GA (2009) Electrochromism in nickel oxide and tungsten oxide thin films: ion intercalation from different electrolytes. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cells 93:2050–2055

Mortimer RJ (2011) Electrochromic materials. Annu Rev Mater Res 41:241–268

Granqvist CG (2014) Electrochromics for smart windows: oxide-based thin films and devices. Thin Solid Films 564:1–38

Lahav M, Boom ME (2018) Polypyridyl metallo-organic assemblies for electrochromic applications. Adv Mater 30:1706641. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201706641

Wu W, Wang M, Ma J, Cao Y, Deng Y (2018) Electrochromic metal oxides: recent progress and prospect. Adv Electron Mater 4:1800185

Sadeghi K, Yoon J-Y, Seo J (2019) Chromogenic polymers and their packaging applications: a review. Polym Rev 60:442–492

Cai GF, Tu JP, Zhang J, Mai YJ, Lu Y, Gu CD, Wang XL (2012) An efficient route to a porous NiO/reduced graphene oxide hybrid film with highly improved electrochromic properties. Nanoscale 4:5724–5730

Cai G, Tu J, Zhou D, Li L, Zhang J, Wang X, Gu C (2014) Constructed TiO\(_{2}\)/NiO core/shell nanorod array for efficient electrochromic application. J Phys Chem C 118:6690–6696

Zhang JH, Cai GF, Zhou D, Tang H, Wang XI, Gu CD, Tu JP (2014) Co-doped NiO nanoflake array films with enhanced electrochromic properties. J Mater Chem C 2:7013–7021

Zhang JH, Tu JP, Zhou D, Tang H, Li L, Wang XI, Gu CD (2014) Hierarchical SnO\(_{2}\)@NiO core/shell nanoflake arrays as energy-saving electrochromic materials. J Mater Chem C 2:10409–10417

Kim J, Ong GK, Wang Y, LeBlanc G, Williams TE, Mattox TM, Helms BA, Milliron DJ (2015) Nanocomposite architecture for rapid, spectrally-selective electrochromic modulation of solar transmittance. Nano Lett 15:5574–5579

Zhou D, Shi F, Xie D, Wang DH, Xia XH, Wang XL, Gu CD, Tu JP (2016) Bi-functional Mo-doped WO\(_3\) nanowire array electrochromism-plus electrochemical energy storage. J Colloid Interface Sci 465:112–120

Wei D, Scherer MR, Bower C, Andrew P, Ryhanen T, Steiner U (2012) A nanostructured electrochromic supercapacitor. Nano Lett 12:1857–1862

Llordés A, Garcia G, Gazquez J, Milliron DJ (2013) Tunable near-infrared and visible-light transmittance in nanocrystal-in-glass composites. Nature 500:323–326

Cong S, Tian Y, Li Q, Zhao Z, Geng F (2014) Single-crystalline tungsten oxide quantum dots for fast pseudocapacitor and electrochromic applications. Adv Mater 26:4260–4267

Wang JL, Lu YR, Li HH, Liu JW, Yu SH (2017) Large area co-assembly of nanowires for flexible transparent smart windows. J Am Chem Soc 139:9921–9926

Niklasson GA, Granqvist CG (2007) Electrochromics for smart windows: thin films of tungsten oxide and nickel oxide, and devices based on these. J Mater Chem 17:127–156

Mardare CC, Hassel AW (2019) Review on the versatility of tungsten oxide coatings. Phys Status Solidi A 216:1900047. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssa.201900047

Granqvist CG (2000) Electrochromic tungsten oxide films: review of progress 1993–1998. Sol Energy Mater Sol C 60:201–262

Magnéli AA (1950) Structure of \(\beta\)-tungsten oxide. Nature 165:356–357

Magnéli G, Andersson B, Blomberg L, Kihlborg L (1952) Identification of molybdenum and tungsten oxides by X-ray powder patterns. Anal Chem 24:1998–2000

Zhang L, Wang H, Liu J, Zhang Q, Yan H (2020) Nonstoichiometric tungsten oxide: structure, synthesis, and applications. J Mater Sci Mater Electron 31:861–873

Wang L, Wang Y, Cheng Y, Liu Z, Guo Q, Ha MN, Zhao Z (2016) Hydrogen-treated mesoporous WO\(_{3}\) as a reducing agent of CO\(_{2}\) to fuels (CH\(_{4}\) and CH\(_{3}\)OH) with enhanced photothermal catalytic performance. J Mater Chem A 4:5314–5322

Solis JL, Saukko S, Kish L, Granqvist CG, Lantto V (2001) Semiconductor gas sensors based on nanostructured tungsten oxide. Thin Solid Films 391:255–260

Yoon S, Jo C, Noh SY, Lee CW, Songc JH, Lee J (2011) Development of a high-performance anode for lithium ion batteries using novel ordered mesoporous tungsten oxide materials with high electrical conductivity. Phys Chem Chem Phys 13:11060–11066

Yoon S, Woo S-G, Jung K-N, Song H (2014) Conductive surface modification of cauliflower-like WO\(_{3}\) and its electrochemical properties for lithium-ion batteries. J Alloys Compd 613:187–192

Cong S, Geng F, Zhao Z (2016) Tungsten oxide materials for optoelectronic applications. Adv Mater 28:10518–10528

Wang Y, Runnerstrom EL, Milliron DJ (2016) Switchable materials for smart windows. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng 7:283–304

Zhou D, Xie D, Xia X, Wang X, Gu C, Tu J (2017) All-solid-state electrochromic devices based on WO\(_{3}{\Vert}\) NiO films: material developments and future applications. Sci. China Chem 60:3–12

Cruz-Leal M, Goiz O, Chávez F, Pérez-Sánchez GF, Hernández-Como N, Santes V, Felipe C (2019) Study of the thermal annealing on structural and morphological properties of high-porosity A-WO\(_{3}\) films synthesized by HFCVD. Nanomaterials 9:1298. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9091298

Cronin JP, Tarico DJ, Tonazzi JCL, Agrawal A, Kennedy SR (1993) Microstructure and properties of sol–gel deposited WO\(_{3}\) coatings for large area electrochromic windows. Sol Energy Mater Sol C 29:371–386

Wen-Cheun AB, Chan K-Y, Knipp V (2019) Effect of film thickness on electrochromic performance of sol–gel deposited tungsten oxide (WO\(_{3}\)). Opt Mater 94:387–392

Rougier A, Portemer F, Quédé A, El Marssi M (1999) Characterization of pulsed laser deposited WO\(_{3}\) thin films for electrochromic devices Appl. Appl Surf Sci 153:1–9

Dinca V, Suchea M (2019) Functional nanostructured interfaces for environmental and biomedical applications, vol 363. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Parshina LS, Novodvorsky OA, Khramova OD, Lotin AA, Shchur PA (2019) PLD of thin WO\(_{3}\) films for solid-state electrochromic cells. J Phys Conf Ser 1164:012003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1164/1/012003

Berggren L, Niklasson GA (2003) Optical absorption and durability of sputtered amorphous tungsten oxide films. Solid State Ionics 165:51–58

Kumar KU, Bhat SD, Subrahmanyam A (2019) Electrochromic device with magnetron sputtered tungsten oxide (WO\(_{3}\)) and nafion membrane: performance with varying tungsten oxide thickness—a report. Mater Res Express 6:045513. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/aafef1

Becker M, Gies M, Polity A, Chatterjee S, Klar PJ (2019) Materials processing using radio-frequency ion-sources: ion-beam sputter-deposition and surface treatment. Rev Sci Instrum 90:023901. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5063976

DIN EN 410:2011-04, Glas im Bauwesen - Bestimmung der lichttechnischen und strahlungsphysikalischen Kenngrößen von Verglasungen

DIN 5031-1:1982-03, Strahlungsphysik im optischen Bereich und Lichttechnik; Größen, Formelzeichen und Einheiten der Strahlungsphysik

ISO 11664-2:2008-02, Colorimetry—part 2: CIE standard illuminants

Gerard P, Deneuville A, Hollinger G, Minh Duc T (1977) Color in “tungsten trioxide” thin films. J Appl Phys 48:4252–4255

McCarthy G, Welton J (1989) X-ray diffraction data for SnO\(_{2}\). An illustration of the new powder data evaluation methods. Powder Diffract 4:156–159

Grier D, McCarthy G (1991) North Dakota State University. ICDD Grant-in-Aid, Fargo, North Dakota, USA

Diehl R, Brandt G, Salje E (1978) The crystal structure of triclinic WO\(_{3}\). Acta Crystallogr B 34:1105–1111

Shigesato Y, Murayama A, Kamimori T, Matsuhiro K (1988) Characterization of evaporated amorphous WO\(_3\) films by Raman and FTIR spectroscopies. Appl Surf Sci 33–34:804–811

Salje E (1975) Lattice dynamics of WO\(_{3}\). Acta Crystallogr 31:360–363

Gabrusenoks JV, Cikmach PD, Lusis AR, Kleperis JJ, Ramans GM (1984) Electrochromic colour centres in amorphous tungsten trioxide thin films. Solid State Ionics 14:25–30

Lee SH, Cheong HM, Tracy CE, Mascarenhas A, Benson DK, Deb SK (1999) Raman spectroscopic studies of electrochromic A-WO\(_3\). Electrochim Acta 44:3111–3115

Schirmer OF (1980) Small polaron aspects of defects in oxide materials. J Phys Coll 41:479–484

Ozkan E, Lee S-H, Tracy CE, Pitts JR, Deb SK (2003) Comparison of electrochromic amorphous and crystalline tungsten oxide films. Sol Energy Mater Sol C 79:439–448

Lupó C, Eberheim F, Schlettwein D (2020) Facile low-temperature synthesis of nickel oxide by an internal combustion reaction for applications in electrochromic devices. J Mater Sci 55:14401–14414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-020-04995-8

Acknowledgements

We thank P. J. Klar and D. M. Hofmann for fruitful discussions and their constant support. The work of M. Gies and F. Michel was funded by the DFG via the RTG (Research Training Group) 2204 “Substitute Materials for Sustainable Energy Technologies”.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handling Editor: Kevin Jones.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gies, M., Michel, F., Lupó, C. et al. Electrochromic switching of tungsten oxide films grown by reactive ion-beam sputter deposition. J Mater Sci 56, 615–628 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-020-05321-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-020-05321-y