Abstract

Continuous heating transformation (CHT) diagrams and continuous cooling transformation (CCT) diagrams of precipitation-hardening steels have the drawback that important information on the dissolution and precipitation of Cu-rich phases during continuous heating and cooling are missing. This work uses a comparison of different techniques, namely dilatometry and differential scanning calorimetry for the in situ analysis of the so far neglected dissolution and precipitation of Cu-rich phases during continuous heating and cooling to overcome these drawbacks. Compared to dilatometry, DSC is much more sensitive to phase transformation affecting small volume fractions, like precipitation. Thus, the important solvus temperature for the dissolution of Cu-rich phases was revealed from DSC and integrated into the CHT diagram. Moreover, DSC reveals that during continuous cooling from solution treatment, premature Cu-rich phases may form depending on cooling rate. Those quench-induced precipitates were analysed for a broad range of cooling rates and imaged for microstructural analysis using optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy and transmission electron microscopy. This information substantially improves the CCT diagram.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Precipitation-hardening stainless steels are iron–chromium–nickel alloys containing precipitation-hardening elements such as aluminium, titanium, niobium, and copper (e.g. [1,2,3]). The strength of such precipitation-hardening steels can be increased substantially by an age-hardening process, resulting in a microstructure with fine precipitates that hinder dislocation gliding and, thereby, increase the strength. Age hardening makes use of the decreasing solubility of the matrix lattice with respect to the major alloying elements at decreasing temperature [4]. The heat treatment process of age hardening consists of three major steps, solution treatment (which for steels typically takes place in the austenite region), quenching and ageing. The solution treatment aims to achieve a solid solution. A certain duration of soaking at solution temperature is often used to finalise the dissolution processes and/or obtain a homogeneous distribution of the dissolved alloying element atoms within the matrix. During quenching, the alloying elements need to be kept in solid solution, resulting in supersaturation of the base material. This condition is far from equilibrium and is, thus, unstable. From this unstable supersaturated solid solution during the final ageing treatment, a high number density of nano-scale precipitates grows, which hinder the dislocation movement and, thereby, increase the strength. In this work, precipitation-hardening steels that use Cu as a precipitation-hardening element are considered. The precipitation sequences of those steels are still a topic of recent research [2, 5, 6] and the precipitation sequence from the supersaturated martensitic phase can be expressed as Cu–Fe rich clusters → Fe–Cu-rich precursors with orthorhombic 9R structures → Cu-rich twinned FCC precursors → FCC Cu [6,7,8]. A core/shell structure with Ni surrounding fine Cu precipitates is also reported to occur within the sequence of Cu-precipitation [9].

To choose appropriate heat treatment parameters for a specific steel in practical heat treatment shops, typically, continuous heating transformation (CHT) and continuous cooling transformation (CCT) are used. CHT and CCT diagrams of precipitation-hardening steels were typically recorded by dilatometry, focussing on the ferrite/martensite to austenite and reverse transformation but disregarding the dissolution and precipitation of Cu-rich phases during continuous heating and cooling, see Figs. 1 and 2.

Continuous heating transformation diagram for steel X5CrNiCuNb16-4 [10]

Continuous cooling transformation diagram for steel X5CrNiMoCuNb14-5 [11] (© Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Co.KG, München)

Figure 1 shows a published continuous heating transformation diagram for precipitation-hardening steel X5CrNiCuNb16-4 [10]. Although the precipitation of Cu in the martensitic phase is illustrated, the important further dissolution of Cu in the austenitic phase is missing. To that extent, the CHT diagram is incomplete. Thus, an appropriate solution treatment temperature cannot be chosen based on that diagram.

Figure 2 shows a published continuous cooling transformation diagram for precipitation-hardening steel X5CrNiMoCuNb14-5 [11]. It only focuses on the martensitic transformation. Since the solubility of Cu decreases with decreasing temperature, there must be quench-induced precipitation if cooling is sufficiently slow. It will be shown later that quench-induced precipitation is indeed occurring at technically relevant cooling rates. However, the CCT diagram is also incomplete. One cannot assess how fast the steel needs to be cooled to supersaturate the Fe matrix with Cu.

It was shown in prior work, that differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) can be used for in situ analysis of precipitation kinetics in precipitation-hardening steels [5, 12, 13]. However, most of the DSC work on such steels only consider heating up to temperatures of about 700 °C, which is not sufficient to detect the final dissolution of Cu. Moreover, there is very little DSC work on cooling [14]. Recently a sophisticated DSC method for the analysis of solid–solid phase transformations has been adapted to allow quantitative evaluation during cooling from solution temperatures up to 1100 °C [15].

This work aims for the in situ detection of both the dissolution of Cu-rich phases during heating as well as quench-induced precipitation during continuous cooling using dilatometry and DSC. This allows the improvement of CHT diagrams by including the dissolution of Cu. For the further improvement of CCT diagrams, a complementary microstructural analysis was done on different length scales using optical microscopy (OM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM).

Materials and methods

In this work, the martensitic, precipitation-hardening steel X5CrNiCuNb16-4 was analysed in two different batches. Samples were either taken out of a conventional hot rolled bar (dimensions Ø 15 x 3000 mm) in annealed (1038 °C, 1 h) and quenched condition, or from laser beam melted (LBM) cylinders (dimensions Ø 7 × 65 mm) in the as-built condition. The chemical composition of both materials, analysed by optical emission spectroscopy, are shown in Table 1.

The transformation of steel X5CrNiCuNb16-4 during heating to austenitisation temperature and cooling to room temperature was investigated in the 30 to 1100 °C temperature range, both by dilatometry and calorimetry. A Type Bähr DIL 805 A/D quenching dilatometer was used. Heating and cooling rates in the 0.1–100 K/s range were selected for investigating the X5CrNiCuNb16-4 steel. Dilatometer samples with 4 mm diameters and 10 mm lengths were turned from the cylindrical blanks. At least three individual samples were used for each scan rate. The execution and evaluation of the tests were based on the methods presented in [16, 17].

A Setaram Labsys Evo instrument, equipped with the highly sensitive Calvet DSC sensor [18], was used for DSC-experiments. This instrument allows scanning rates in the 0.01–0.3 K/s range. A detailed description of the execution and evaluation of the calorimetric experiments can be found in [15]. The technical ceramic Rescor960 (Al2O3) was used as reference material. The dimensions of the sample and reference materials were Ø 4.9 mm × 11.6 mm. These were placed in ceramic crucibles, which were placed in platinum crucibles. The tests took place in argon atmospheres. At least four individual samples were used for each scan rate investigated by DSC.

Vickers hardness tests (ISO 6507-1) were carried out to establish the effect of different rates of cooling on subsequent mechanical properties using a Shimadzu type HMV-2 microhardness tester. Therefore, austenitised and controlled cooled samples were artificially aged (480 °C, 60 min). Additional X5CrNiCuNb16-4 samples were sealed in quartz tubes with an argon atmosphere to prevent oxidation and heat-treated in a controlled furnace to achieve very low cooling rates of 10−3 K/s and 10−4 K/s.

The microstructure of selected samples was investigated using OM, SEM and STEM to prove quench-induced precipitation. All samples for OM and SEM were embedded in epoxy, ground and polished according to standard preparation methods. The images were recorded for samples in a polished condition using OM with a Leica DMI5000 M microscope. The samples for SEM were analysed using a field emission SEM Zeiss MERLIN®VP Compact equipped with an EDS detector Bruker XFlash 6/30 and analysis software Bruker Quantax ESPRIT Microanalysis software (version 2.0). SEM-secondary electron (SEM-SE) images were obtained using a high-efficiency Everhart–Thornley-type HE-SE detector at 5 kV acceleration voltage. Representative areas of the samples were analysed and mapped to determine the elemental distribution based on the EDS (energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy)-spectra data using the QUANTAX ESPRIT Microanalysis software (version 2.0). The embedded, ground and polished samples were mounted on the SEM carrier with adhesive conductive carbon and aluminium tape. For the EDS analysis, the acceleration voltage was set to 20 kV.

The samples for STEM were cold cut out of the heat-treated dilatometer samples to discs to Ø 3 mm × 300 µm. Subsequently, the discs were ground to about 100 µm thick and electropolished using a Struers TenuPol device with an electrolyte consisting of 65–85% Ethanol C2H6O, 10–15% 2-Butoxy-Ethanol C6H14O2 and 5–15% Water H2O. The STEM investigations were performed using a JEOL JEM ARM200F at 200 kV. The images were taken using the high angle annular dark-field (HAADF) detector. The microscope was equipped with a JED-2300 spectrometer for STEM–EDS analysis.

Results and discussion

Continuous heating to the solution treatment temperature

The conventional martensitic precipitation-hardening steel X5CrNiCuNb16-4 (designated as “conv”) was analysed during continuous heating using dilatometry and DSC, see Fig. 3a, b. The precipitation of Cu-rich precursor phases is seen in both methods. In the dilatometer curve, the precipitation reaction is seen as a weak slope discontinuity, indicating a relative shortening of the sample with respect to the expansion of the martensitic matrix at about 500 °C and it is hard to determine the characteristic temperatures of precipitation start and end from this dilatometer curve. Certainly, in the first derivative of the strain curve, this specific reaction is seen more clearly. In DSC, a clear exothermic signal in a temperature range of about 400–500 °C indicates a precipitation process that can be attributed to the precipitation of Cu [19,20,21,22,23]. Even at lower temperatures, 300–400 °C, an endothermic peak can be seen during continuous heating in DSC. Probably, this peak indicates the dissolution of relatively fine Cu–Fe clusters that were present in the initial state prior heating. Obviously, its dissolution does not cause a measurable change in volume/length since no slope change is seen in the dilatometer curve and its first derivative.

The austenite transformation is much easier to see in the dilatometer curve, which is why the dilatometric signal is typically used to characterise the formation of austenite, which is completed at a temperature of about 750 °C. In DSC, in the relevant temperature range, an overlap of several reactions makes the curve interpretation difficult since DSC measures the sum of any occurring heat effect. From about 500 to 750 °C, a stronger endothermic peak is seen, which has a shoulder at about 700 °C. In this temperature range, the austenite transformation overlaps with the magnetic transition [13, 24, 25] and, as will be discussed later, potentially also with the dissolution of Cu-rich particles.

The essential final dissolution of Cu-rich precipitates in the austenite matrix is not seen in the dilatometer curve in Fig. 3a. However, in the first derivative curve, an undefined signal has been observed at temperatures above the nominal austenitisation finish temperature. Since the matrix has been converted from martensite to austenite, the reference system has changed. It is well known that the thermal expansion of austenite is more pronounced than that of martensite. At this point, it is not possible to differentiate between a thermally induced change in length and a transformation induced change in length. In the literature, a comparable signal was detected for martensitic hardening steel M350 and precipitation-hardening steel 13–8 PH [10, 26]. The involved authors attributed this anomaly to a second step of austenite formation. However, they also investigated X5CrNiCuNb16-4 and could not observe this behaviour in this steel. Furthermore, in this work, such an undefined signal has not been observed in X5CrNiCuNb16-4 LBM.

This dissolution and, particularly, the completion of this dissolution is seen well in DSC (Figs. 3b, 7), as indicated by the endothermic peak between about 800 and 1000 °C. That is, the drop of the DSC curve back to its zero level at about 980 °C can be taken as the heating rate specific solvus temperature. Above this temperature, the whole amount of Cu will be in solid solution.

To verify that the last endothermic peak at about 870 °C is indeed related to the dissolution of Cu, we did stepwise heating/quenching and reheating experiments. Figure 4 shows the methodology. At first, all samples were austenitised at 1040 °C for 30 min and quenched at 100 K/s to guarantee all samples were in the same initial condition. After stepwise heating in the dilatometer to distinct maximum temperatures, the samples were immediately quenched at 100 K/s to room temperature. To prove the dissolution of Cu during stepwise heating, we evaluated the reheating DSC signal. During reheating, the exothermic peak between about 400 and 500 °C was considered as this refers to the precipitation of Cu-rich precursor phases and can only be present if Cu before has been solved into the matrix. As an orientation, a DSC heating curve up to 1100 °C is shown as reference in Fig. 4b, allowing one to match certain maximum temperatures from stepwise heating to the original DSC signal we intend to interpret.

Figure 5 shows the resulting DSC reheating curves. The exothermic precipitation peak increases its peak area with increasing maximum temperature up to about 1000 °C, which correlates with the drop of the DSC curve to zero in Fig. 3. For maximum temperatures of 1000 °C and higher, the precipitation peak is very similar and a highly similar supersaturation prior to precipitation can be concluded, showing that the HRSS is indeed about 980 °C. Thereby this important result can be evaluated from the DSC heating curves and can be integrated as a major improvement in the CHT diagram given in Fig. 6.

The complete continuous heating transformation diagrams for both X5CrNiCuNb16-4 materials considering the dissolution of Cu-rich phases are shown in Fig. 6. Due to the severe overlap of endothermic reactions at temperatures between about 500 and 750 °C the onset of single reactions can only be estimated. For the start of the final dissolution of the Cu-rich phases, we determined the local minimum of the DSC curve at 750 °C for X5CrNiCuNb16-4 conv, see Fig. 4b. The characteristic temperatures of the austenite transformation were taken from dilatometry. Therefore, for the first time, the heating rate specific solvus temperatures of Cu dissolution is integrated into a CHT diagram; compare Fig. 1 from literature with this work, as shown in Fig. 6.

These diagrams are only valid for the specific initial condition, which is as-quenched for the conventional material and as-built for the LBM material, respectively. Comparing the two steels, differences are seen, see Fig. 6a, b. The LBM materials show higher transformation temperatures. Whether this difference is due to the production route (conventional vs. LBM) or due to the deviation in chemical composition (especially Cu-content, see Table 1) has not been investigated up to now.

To investigate the influence of different initial heat treatment conditions, as shown in Fig. 7, shows a comparison of heating DSC for four initial conditions of X5CrNiCuNb16-4 conv during continuous heating with 0.1 K/s. We compared two cooled conditions with remaining supersaturation (rapidly quenched at 100 K/s and cooled at 0.01 K/s) with two aged conditions (peak aged condition: 480 °C, 60 min [27] and an overaged condition: 480 °C, 1800 min). Comparing the heating of the as-quenched state with the state cooled at 0.01 K/s, both conditions show a clear precipitation peak between about 400 and 500 °C. In the slower cooled condition, the peak area is decreased due to lower initial supersaturation. In contrast, during heating of the aged conditions, no precipitation peak is seen, but instead, the subsequent endothermic peak is substantially broadened and begins at lower temperatures. Moreover, this endothermic peak has now a shoulder at 530 °C. This additional endothermic reaction consequently relates to the dissolution of the Cu-rich precipitates formed during the preceding ageing process. i.e. when constructing a CHT diagram of an initially aged state, Cu dissolution can already start in the ferritic/martensitic matrix before austenitisation.

Continuous cooling from solution treatment temperature

In Fig. 8, selected continuous cooling curves of X5CrNiCuNb16-4 LBM obtained by dilatometer (Fig. 8a) and DSC (Fig. 8b) are shown. In the dilatometer during cooling, only the martensitic transformation is detected, while DSC also clearly shows a two-stage exothermic precipitation reaction, ranging from about 1000 to 780 °C. We denote those as high-temperature precipitation (HTP, ≈ 1000 to 880 °C) and low-temperature precipitation (LTP, ≈ 880 to 680 °C).

In Fig. 9a, continuous DSC cooling curves of X5CrNiCuNb16-4 LBM are shown. In Fig. 9b, the specific precipitation enthalpy (integrated area from precipitation peaks) and the hardness in the as-quenched and the aged condition are plotted depending on cooling rate. From Fig. 9a, the kinetic development of the two quench-induced precipitation reactions can be assessed in a broad range of cooling rates. HTP dominates at slow cooling at 0.01 K/s and it is increasingly suppressed with increasing cooling rate. LTP first increases its precipitation enthalpy. With further increasing cooling rate, the LTP is suppressed also. This happens at cooling rates at which the HTP is suppressed nearly completely. This type of kinetic behaviour, i.e. the interplay between a precipitation reaction at higher temperatures and a subsequent one at lower temperatures is known for other age-hardening alloys, including a wide range of Al alloys and Mg alloys [28].

For X5CrNiCuNb16-4 conv, even during slow cooling at 0.01 K/s, only one precipitation peak is seen between about 800 to 640 °C, as shown in Fig. 10a. However, the results shown in Fig. 7 indicate a substantial remaining supersaturation after this slow cooling. In comparison with Fig. 9a, we assume this peak to belong to the LTP and expect that an HTP will be present if cooling would be performed even slower (which is not possible with an acceptable signal to noise ratio in the DSC instrument used here).

From the hardness in the as-quenched and aged conditions, as shown in Figs. 9b, 10b, critical cooling rates (CCR) to suppress premature Cu-precipitation of 10–20 K/s for the LBM steel and about 1 K/s for the conventional steel can be determined. Above these rates, the hardness in the aged condition reaches a saturation level. Interestingly, the as-quenched hardness for both alloys shows a maximum for cooling rates about one to two orders of magnitude slower. This indicates a direct hardening contribution of the fine quench-induced precipitates formed in this cooling rate range, i.e. the LTP. This behaviour has previously been shown for some age hardening Al- and Ni-based alloys [15, 28].

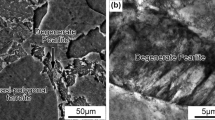

The changes in the microstructure related to the precipitation reactions observed in DSC can be assessed in Figs. 11 and 12. From Fig. 11, in OM images, copper-coloured polygonal-shaped precipitates are seen. At the slowest cooling rate applied here, 0.0001 K/s, they reach dimensions of up to some µm and substantially decrease in size with increasing cooling rate. The systematic change in size with increasing cooling rate proves that those particles originate from cooling. In detail, particularly seen from the 0.0001 K/s image, there are two populations of quench-induced copper-coloured precipitates, some very coarse and some finer. It is expected that the larger particles originate from the HTP, while the smaller particles might originate from the LTP. In SEM those particles appear bright. SEM–EDS revealed that those precipitates are enriched in Cu indeed (Fig. 13). Based on their size and the above-mentioned precipitation sequence [7, 8], we expect at least the coarse particles to be fcc-Cu. The dark spherical spots seen in Fig. 11 are pores from the LBM process.

HAADF-STEM on samples cooled at 0.03 K/s also shows two populations of Cu-rich precipitates in Fig. 14. There are few potentially globular particles with diameters of about 100 nm and several smaller particles with sizes of about 10 to 30 nm. For the larger ones, STEM–EDS showed enrichment in Cu and enrichment in Ni seems possible (EDS spectrum (028) in Fig. 14c). From the similar contrast of the smaller ones, we also conclude a Cu enrichment. The EDS spectra of a grain containing a large number of the addressed smaller particles (030) and grain without precipitates (026) are shown in Fig. 14d. The comparison of both suggests enrichment in Cu as well as in Ni for the smaller particles. The enrichment of the quench-induced precipitates in Cu but potentially also in Ni is consistent with earlier findings on the precipitation sequence [9] but needs further investigation in future. The increased as-quenched hardness at this cooling rate (Fig. 9) suggests that the quench-induced particles give an own hardening effect, which would fit the 10 nm size of the smaller particles seen in Fig. 14. As indicated above, some grains contain a high number density of quench-induced precipitates, while other grains seem to contain very little of those. In Fig. 15, a STEM bright-field image shows substantial contrast differences between the two types of grains—within the grain in which a high number of quench-induced precipitates is seen, the BF-STEM images indicate a high density of dislocations. In contrast, the grain without precipitates seems also to contain much fewer dislocations. This might hint on the nucleation mechanism of the quench-induced precipitates. In general, in this type of steel, a high density of dislocations is known to complicate the TEM investigation of the age-hardening precipitates [7, 29].

a, b HAADF-STEM images of Cu-rich precipitates in X5CrNiCuNb16-4 LBM samples cooled at 0.03 K/s and marked areas for EDS investigation. Two populations of precipitates are seen: some few globular ones with ∅ ≈ 100 nm (probably originating from the HTP at this relatively fast cooling rate) and several much smaller ones with ∅ ≈ 10 to 30 nm (probably originating from the LTP); c, d EDS spectra of relevant particles, spectra in (c) corresponds to areas 027 and 028 in (b), while spectra in (d) correspond to areas 026 and 030 in (b)

Bright field STEM image of the same sample area in shown Fig. 14, indicating a substantial difference in the dislocation density between grains that contain a higher or, respectively, low number of quench-induced precipitates

STEM–EDS additionally shows Nb-rich particles (probably niobium carbides) at intersections of grain boundaries, compare EDS spectrum (027) in Fig. 14c. In the OM-images, the niobium carbides appear grey. Those particles are very rarely found, particularly after very slow cooling. They may contribute an additional precipitation reaction at very slow cooling rates in DSC.

The complete continuous cooling transformation diagrams for both steels X5CrNiCuNb16-4 considering the quench-induced precipitation of Cu-rich phases are shown in Fig. 16. In comparison to Fig. 2, it becomes obvious that this steel is not as quench insensitive as expected. Instead, premature Cu-precipitation takes place at industrially relevant cooling rates, which significantly influence the hardness after ageing. The differences in CCT diagrams regarding production routes (conventional vs. LBM) and chemical composition (especially Cu content, see Table 1) needs further investigation. Furthermore, the LBM material has been austenitised at a higher temperature of 1100 °C (conventional 1040 °C) because the CHT diagram in Fig. 6b requires higher temperatures for Cu dissolution.

Conclusions

Based on a comparative approach of dilatometry and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) for the in situ analysis of precipitation and dissolution reactions during continuous heating and cooling of martensitic precipitation-hardening steels on two variants of X5CrNiCuNb16-4, we can conclude the following:

-

Compared to dilatometry, DSC is much more sensitive to precipitation and dissolution reactions affecting volume fractions of a few per cent. Precipitation during continuous cooling from solution temperature is well seen in DSC, while it is not detected in dilatometry.

-

A substantially improved continuous heating transformation (CHT) diagram was derived, which particularly includes the important aspect of Cu dissolution and its heating rate specific solvus temperature.

-

A substantially improved continuous cooling transformation (CCT) diagram was derived, which for the first time includes the formation of quench-induced Cu precipitates.

-

The hardness in the aged conditions indicates critical cooling rates of 10 to 20 K/s for the higher concentrated LBM material and about 1 K/s for the conventional material.

-

For the LBM steel, a two-stage precipitation sequence was found for the slower cooling rates (two precipitation peaks, denoted high-temperature precipitation (HPT) and low-temperature precipitation (LPT)).

-

Optical, scanning electron and scanning transmission electron microscopy reveal Cu-rich quench-induced precipitation, which substantially decreases in particle size with increasing cooling rate. Within the LBM material after cooling at 0.0001 K/s, particles from the HTP reach dimensions up to some few µm, while at the relatively fast rate of 0.03 K/s, the globular particles from the LTP have ∅ of about 10 to 30 nm.

References

Mariani FE, Takeya GS, Casteletti LC et al (2016) Heat treatment of precipitation-hardening stainless steels alloyed with niobium. Mater Perfom Charact 5(1):38–46. https://doi.org/10.1520/MPC20150039

Hofinger M, Turk C, Ognianov M et al (2020) Precipitation reactions in a Cu–Ni–Al medium carbon alloyed dual hardening steel. Mater Charact. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2020.110126

Irvine KJ, Llewellyn DT, Pickering FB (1959) Controlled-transformation stainless steels. J Iron Steel Inst 192:218–238

Martin JW (1998) Precipitation hardening. Butterworth-Heinemann, Elsevier

Huang D, Yan J, Zuo X (2019) Co-precipitation kinetics, microstructural evolution and interfacial segregation in multicomponent nano-precipitated steels. Mater Charact. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2019.06.028

Han G, Xie ZJ, Li ZY et al (2017) Evolution of crystal structure of Cu precipitates in a low carbon steel. Mater Des 135:92–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2017.08.054

Othen PJ, Jenkins ML, Smith GDW et al (1991) Transmission electron microscope investigations of the structure of copper precipitates in thermally-aged Fe–Cu and Fe–Cu–Ni. Philos Mag Lett 64(6):383–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500839108215121

Othen PJ, Jenkins ML, Smith GDW (1994) High-resolution electron microscopy studies of the structure of Cu precipitates in α-Fe. Philos Mag 70(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/01418619408242533

Couturier L, De Geuser F, Descoins M et al (2016) Evolution of the microstructure of a 15-5PH martensitic stainless steel during precipitation hardening heat treatment. Mater Des 107:416–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2016.06.068

Kapoor R, Batra IS (2004) On the α′ to γ transformation in maraging (grade 350), PH 13-8 Mo and 17-4 PH steels. Mater Sci Eng, A 371(1–2):324–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2003.12.023

Brezina P, Sonderegger B (1978) Wärmebehandlung, Gefüge und Eigenschaften des korrosionsträgen, martensitaushärtbaren Stahles X5CrNiMoCuNb14-5 (14-5 PH). HTM Härtereitechnische Mitteilungen 33(1):1–12

Hofinger M, Ognianov M, Turk C et al (2019) Early stages of precipitate formation in a dual hardening steel. HTM J Heat Treat Mater 74(5):293–301. https://doi.org/10.3139/105.110390

Maruyama N, Sugiyama M, Hara T et al (1999) Precipitation and phase transformation of copper particles in low alloy ferritic and martensitic steels. Mater Trans 40(4):268–277

Rowolt C, Milkereit B, Gebauer M et al (2018) In-situ phase transition analysis of conventional and laser beam melted AlSi10Mg and X5CrNiCuNb16-4 alloys. HTM J Heat Treat Mater 73(6):317–334. https://doi.org/10.3139/105.110366

Rowolt C, Milkereit B, Andreazza P et al (2019) Quantitative high temperature calorimetry on precipitation in steel and nickel alloys. Thermochim Acta 677:169–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tca.2019.01.026

Reich M, Milkereit B, Bader M et al (2013) Calorimetric and dilatometric study of tempering behavior in the heat affected zone of T24 welding seams. HTM J Heat Treatm Mater 68(6):274–282. https://doi.org/10.3139/105.110202

Verein Deutscher Eisenhüttenleute (1993) Richtlinien für Vorbereitung, Durchführung und Auswertung dilatometrischer Umwandlungsuntersuchungen an Eisenlegierungen (Stahl-Eisen-Prüfblatt 1681:1993)

Calvet E, Prat H, Skinner H (eds) (1963) Recent progress in microcalorymetry. Pergamon Press, Oxford

Antony KC (1963) Aging reactions in precipitation hardenable stainless steel. J Met 15:922–927. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03397271

Hsiao CN, Chiou CS, Yang JR (2002) Aging reactions in a 17-4 PH stainless steel. Mater Chem Phys 74(2):134–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0254-0584(01)00460-6

Goller GN, Clarke WC (1950) New precipitation-hardening stainless steel. Iron Age 165:86–89 and 79–83

Rack HJ, Kalish D (1974) The strength, fracture toughness, and low cycle fatigue behavior of 17-4 PH stainless steel. Metall Trans 5(7):1595–1605

Viswanathan UK, Banerjee S, Krishnan R (1988) Effects of aging on the microstructure of 17-4 PH stainless steel. Mater Sci Eng, A 104:181–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-5416(88)90420-X

Christien F, Telling MTF, Knight KS (2013) A comparison of dilatometry and in situ neutron diffraction in tracking bulk phase transformations in a martensitic stainless steel. Mater Charact. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2013.05.002

Christien F, Saindrenan G, Le Gall R et al (1999) Some aspects of interfacial segregation in martensitic stainless steel 17-4 PH. In: EDEM 99: international conference on environmental degradation of engineering materials, pp 99–104

Kapoor R, Kumar L, Batra IS (2003) A dilatometric study of the continuous heating transformations in 18wt.% Ni maraging steel of grade 350. Mater Sci Eng, A 352(1):318–324

ASTM International (West Conshohocken) A564/A564M:2013 Standard Specification for Hot-Rolled and Cold-Finished Age-Hardening Stainless Steel Bars and Shapes

Milkereit B, Starink MJ, Rometsch PA et al (2019) Review of the quench sensitivity of aluminium alloys: analysis of the kinetics and nature of quench-induced precipitation. Materials. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12244083

Murayama M, Katayama Y, Hono K (1999) Microstructural evolution in a 17-4 PH stainless steel after aging at 400°C. Metall Mater Trans A 30(2):345–353

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. IGF-Project No.: 18.859 B/DVS No.: 13.015 of the Research Association Welding and Allied Processes of the German Welding Society (DVS), Aachener Str. 172, 40223 Düsseldorf, was encouraged via the German Federation of Industrial Research Associations (AiF) within the framework of the Industrial Collective Research (IGF) support programme by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy due to a decision of the German Bundestag.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BM, OK and CR designed the experiments. CR measured the DSC data and prepared the microstructure samples. AS did the SEM work and CK did the TEM analysis. BM and CR wrote the manuscript. All authors joined the discussion and approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rowolt, C., Milkereit, B., Springer, A. et al. Dissolution and precipitation of copper-rich phases during heating and cooling of precipitation-hardening steel X5CrNiCuNb16-4 (17-4 PH). J Mater Sci 55, 13244–13257 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-020-04880-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-020-04880-4