Abstract

In this paper, indium-doped zinc oxide (IZO) films were grown by spray pyrolysis, using zinc acetate and indium acetylacetonate precursors. The focus was on developing a solution recipe based on water as solvent, with only minor acetic acid content, as well as keeping the substrate temperature as low as possible—at 360 °C. The process is therefore environment friendly and energy efficient. Despite the challenging conditions, the resulting IZO films were highly transparent and conductive. Their texture deviates strongly from the (002) texture of ZnO and depends on the indium content, which also influences the resistivity. The latter attains its minimum for an indium concentration of 4 at.% in the solution and decreases for increasing film thickness, reaching the value of (5.0 ± 0.1) × 10−3 Ω cm, mainly due to the increase in carrier mobility. The stability of the resistivity after high dose of UV irradiation was found to increase with the carrier density and the film thickness. Thick, highly doped films show minimal resistivity modification even after a total dose of 12.1 kJ/cm2 UVA/UVB irradiation. Finally, to demonstrate its applicability in devices, the IZO electrode was used for the fabrication of a lead-perovskite absorber solar cell, yielding an energy conversion efficiency of 6% and 910 mV open-circuit voltage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Zinc oxide (ZnO) is a wide-bandgap n-type semiconductor, which is optically transparent in the visible range and exhibits significant conductivity upon doping [1]. Thus, it can be used in applications which require transparent electrodes (TEs), such as modern optoelectronic devices (e.g., flat screens and touch panel displays), thin film photovoltaics or low-emissivity windows [2]. The TE market is currently dominated by tin-doped indium oxide (ITO), which has the drawback of having indium as main constituent, which is a scarce and expensive element. This cost factor is a motivation to search for alternatives, which reduce the indium consumption, such as doped ZnO materials. The use of ZnO is especially advantageous if it is deposited with a low-cost method, such as spray pyrolysis [3]. Typical donors for ZnO are halide anions or the group 13 metals Al, Ga or In. Indium doping has delivered the best reported resistivity for films grown by spray pyrolysis, with values ranging from 9 × 10−4 to 5 × 10−3 Ω cm [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. In these films, the In-dopant concentration was less than 4 at.%.

In spray pyrolysis, the low-chain length alcohols methanol [5, 10, 12], ethanol [9] and isopropanol [4, 11, 13,14,15] are predominantly used as solvents, either pure or in combination with water. As these alcohols are flammable, they can pose a safety hazard when sprayed on a hot surface, which is a disadvantage for the large-scale implementation of this technique. Moreover, methanol, the most popular among the used solvents, is highly toxic. This can pose a danger, as aerosols and vapors produced in the spraying process can be taken up via inhalation. Zaleta-Alejandre et al. [7] showed that it is possible to replace these chemicals with water as main solvent, making the solution more inexpensive and environment friendly. In their approach, a mixture of water and acetic acid (HAc) was used, obtaining a minimum resistivity of 8 × 10−3 Ω cm, at elevated substrate temperature of 450 °C. The investigated materials were, however, quite thin (<250 nm); thus, their sheet resistance was too large (>300 Ω/sq.) for practical device implementation.

Based on this approach, the aim of the present work was to develop a process for preparing transparent and conductive In-doped ZnO (IZO) films by spray pyrolysis with a sheet resistance value lower than 50 Ω/sq. To enhance the upscaling potential of the technique, the focus was set on low-cost and low-risk, aqueous-based solution recipes, as well as low substrate temperatures. The dependence of the IZO film sheet resistance on the solution composition and the film thickness was investigated, as well as the resistance stability under high dose of UV irradiation and thermal treatment. Finally, the work concludes with the implementation of the optimized IZO electrode in organohalide lead-perovskite absorber solar cells.

Materials and methods

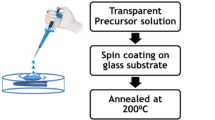

The solutions were prepared by adding appropriate amounts of zinc acetate dihydrate (ZnAc2, 0.1 M Zn(CH3COO)2·2H2O, puriss. p.a (≥99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich 96459), indium acetylacetonate (In(acac)3, 0–8 at. % In(OCCH3CHOCCH3)3, ≥99.99% Sigma-Aldrich I3300) and acetic acid (HAc, 4–12 vol%, ≥99.99% Sigma-Aldrich A6283) to ultrapure water (>18.2 MΩ). The solutions containing In were then further heated to 80 °C for 2 h in order to dissolve the In(acac)3. If residual white solid remained in the solution, it was allowed to settle to the bottom of the flask. The thin films were deposited on a Sono-Tek ExactaCoat system, using a Sono-Tek Impact Nozzle, spraying in vertical geometry. The nozzle used ultrasonic atomization and was operated at a frequency of 120 kHz and a power of 3 W. The scan speed of the nozzle was 25 mm/s. A complete substrate scan, representing one deposition cycle, lasted 8 s. A total of 570 cycles resulted to a thickness of 800 nm, which was the standard thickness unless otherwise stated. Pressurized air was used as shaping gas (0.5 bar), and the solution was sprayed with a rate of 0.8 ml/min. Borosilicate microscope slides (Schott Nexterion D, 75.6 × 25 × 1 mm) were used as substrate after being cleaned in an ultrasonic bath for 5 min at 60 °C in a Hellmanex III solution and then rinsed with DI water and dried. The slides were placed on an aluminum plate residing on the hot plate, which was set to 360 °C during deposition.

The thickness of the films and the grain morphology were analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeiss Ultra 40) both in cross section and in plane view. The crystal structure was additionally investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Panalytical XPert MPD). Direct transmittance was measured by a Fourier transform (FT) spectrometer (Bruker Vertex 70) in the range of 300–2400 nm. The same instrument was used to measure specular reflectance spectra at an angle of 13°. Sheet resistance, carrier density and mobility values were extracted from Hall-effect measurements, which were performed in the van der Pauw geometry, with a magnetic field of 0.3 T. An average value and a standard deviation of these quantities were extracted for each sample (1 cm2) from a number of measurements, which were conducted within a period of several days. The samples were measured in dark conditions to ensure resistance stability. Elemental analysis was performed using optical emission spectroscopy (OES, Perkin-Elmer Optima 5300 DV).

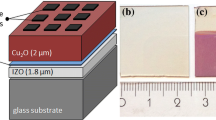

For the fabrication of the Pb-perovskite solar cell, the IZO-coated glass substrate was used to spin-coat the solar cell films inside a glovebox, in N2 atmosphere. Firstly, a PEDOT:PSS layer (Clevios PH1000) with DMSO additive was deposited and annealed at 100 °C for 5 min. Then, the methylammonium lead iodide/chloride MAPbI3-xClx (Ossilla, I101) absorber was coated and annealed at 90 °C for 3 h. A PC70BM layer (Merck) followed, which was annealed at 90 °C for 10 min. Finally, a layer of ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) (Nanograde N-10) was deposited atop and annealed at 90 °C for 5 min. The sample was then taken out of the glovebox, and top Al contacts were evaporated through a shadow mask. The cells were not further encapsulated, and their current–voltage curves were measured at ambient atmosphere under dark and illuminated conditions using a solar simulator (AM1.5G spectrum).

Results

Solution composition

Highly uniform ZnO thin films were produced by spray pyrolysis in our research group, using ZnAc2 as precursor [16]. This compound is believed to form basic zinc acetate in a first thermal decomposition step, which is volatile and can thus decompose in a CVD-like manner [17]. One of the targets in the present work was to retain this growth type of the undoped ZnO after introduction of In as dopant. To achieve this, the dopant source should be volatile and not interfere with the decomposition of ZnAc2. Fulfilling both requirements, In(acac)3 was chosen as dopant precursor, as it is both volatile and chemically quite stable due to the chelation effect. However, this compound showed only limited solubility in the used HAc–water mixture, and thus, it was necessary to heat the solutions to 80 °C for 2 h. In this period, In(acac)3 dissolved, most probably by partially replacing acetylacetonate ligands with water or acetate ions [18].

The HAc content in the solution influenced the dopant dissolution process and consequently the properties of the films. For this reason, the HAc content needed to be optimized. In Table 1, the impact of different HAc concentrations (4, 8, 12 vol%) on the resistivity, Hall carrier density and mobility are shown. Comparing the 4 and the 8 vol% samples, the resistivity shows a distinctive drop from (1.9 ± 0.3) × 10−2 Ω cm to (7.3 ± 0.6) × 10−3 Ω cm, which is mainly due to a twofold increase in the carrier density from (4.1 ± 0.8) × 1019 to (8.2 ± 0.4) × 1019. This most probably arises from the limited solubility of In(acac)3 in the 4 vol% solution, from which a white precipitate had to be filtered off before the deposition took place. An additional increase in HAc to 12 vol% did not lead to a further resistivity improvement, and therefore, the HAc content was set to 8 vol% for the further experiments.

In the next step, the concentration of In(acac)3 was varied from 0 to 8 at.% in order to find the optimum value. The actual In content in the films, extracted by OES, is shown in Table 2. Similar In concentration in the film as in the solution was found for the IZO-2 and IZO-4 samples. In contrast, significantly smaller In concentrations in the film as compared to the solution were found for IZO-6 and IZO-8, which arises most probably from the limited In-dopant solubility. Indeed, marked precipitation could be observed in these solutions. A higher degree of In incorporation might be possible by increasing the HAc concentration.

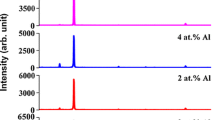

The dopant incorporation resulted in changes in the film morphology, as could be observed by both SEM and XRD. In Fig. 1, the plane-view micrograph of the undoped sample features stacked platelet structures, of hexagonal shape, vertically protruding from the surface. The most prominent peak in the diffractogram of this material (Fig. 2 (a)) is the (002) reflection at 34.53° corresponding to the zincite phase (ICDD 00-036-1451). This rough microstructure is typical for ZnO grown by pyrolysis of solutions with water and HAc as solvent [19, 20]. The IZO samples, however, showed a different grain morphology. IZO-2 consisted of platelet-shaped crystals, tilted 90° to the substrate and organized in bigger agglomerates. The XRD pattern of this material showed a (100) texture. For this doping level, the films are approximately 150 nm thicker than the other films (as seen from SEM cross-section micrographs), although the same amount of precursor solution was used in all cases. This difference in thickness presumably arises from the less dense crystal stacking of the IZO-2 sample. The IZO-4 sample, on the other hand, showed a smooth surface composed of small grains (Fig. 1). For this film, the (110) peak at 56.54° is dominant (Fig. 2a). Nearly, the same diffraction pattern could be obtained for the IZO-6 sample, although it appeared to have a rougher surface in the SEM micrographs (Figs. 1, 2a). This preferential (110) orientation is unique among the reported high-quality sprayed IZO films, of which the majority exhibited a (101) texture [4, 6, 9,10,11, 13,14,15]. In the IZO-8 sample, the (110), (100) and (101) reflection peaks are practically equal, showing that the film is composed of grains with various orientations (Fig. 2a). The elongated, platelet-like grains appearing in the SEM image can be inferred to the (100) orientation (like in the IZO-2 sample) (Fig. 1). In addition to the change in peak intensity, a continuous shift of the peak positions to lower Bragg angles with increasing doping concentration could be observed (Fig. 2b). This shift amounts up to 0.18° between the ZnO and the IZO-8 sample and is attributed to the uniform lattice expansion caused by the introduction of the bulky In-dopant into the ZnO lattice. Using the Scherrer formula [21], an almost linear decrease in the domain size is observed as a function of the In doping for both the (110) and the (100) peak, underlining the gradual loss of texture in the highly doped films (Fig. 2c).

It should be noted that, apart from the solution composition and deposition conditions, the use of a seeding layer can also influence the texture of the film. It was reported in [13], for example, that a (002)-textured ZnO seeding layer modified the structure of the IZO film grown atop by spray pyrolysis, from granular to columnar. Nevertheless, the seeding layer could not impose completely its texture to the subsequent IZO film, which maintained its preferential (101) orientation. In the present study, the use of seeding layer was not investigated.

The In doping not only modified the morphology but also the electrical properties of the films, as shown in Fig. 3. The ZnO resistivity (3.30 ± 0.04) Ω cm is much higher compared to the IZO films, which range from (1.60 ± 0.1) × 10−2 Ω cm for IZO-2 to (7.3 ± 0.6) × 10−3 Ω cm for IZO-4. The reason for this is the low carrier density of ZnO, which is ca. 2 orders of magnitude lower than for the IZO films. The carrier density presents a maximum for the IZO-6 film and then marks a pronounced decrease for IZO-8. On the other hand, the mobility of the doped films is significantly lower compared to ZnO. Among the IZO films, the mobility increases with the dopant concentration with the exception of IZO-6. The mobility depends on several factors, such as the carrier density, the film texture, the grain structure and segregation of impurities at the grain boundaries. Since the films present pronounced morphological modifications as a function of the In concentration, it is very difficult to explain why the doped films’ mobility presents the observed behavior. The range of the observed mobility values is in accordance with the literature for IZO films deposited by spray pyrolysis [4, 13].

Due to the observed minimum in resistivity and in order to keep the In-consumption at the lowest possible level, the dopant concentration was chosen to be 4 at.% (in solution) for the further experiments.

The ZnO sample had a hazy appearance with low direct transmittance in the visible range of the spectrum (Fig. 4a) due to the high film roughness, in agreement with the literature for ZnO films of similar morphology [20]. The smoother surface of the IZO films is manifested in the appearance of distinct Fabry–Perot fringes (Fig. 4b–e) and in the increase in the overall transmittance below 1000 nm. The 800-nm-thick films exhibited an average specular transmittance between 81.6 and 82.8% (including the glass substrate) in the window 400–1000 nm. At higher wavelengths (>1500 nm), the transmittance is sharply decreasing for the IZO films due to the pronounced free carrier absorption.

In parallel, the band edge shifts to lower wavelengths for the IZO films compared to ZnO, which is attributed to the Burstein–Moss effect. Nevertheless, the bandgap values of the IZO films, as extracted from Tauc plots [22] (Fig. 4f) and appear in Table 2, cannot be explained by the Burstein–Moss effect alone, which predicts a bandgap widening proportional to \( n^{{\frac{2}{3}}} \) [23]. Indeed, despite the larger carrier density of the IZO-4 film compared to IZO-2, both films yield the same optical bandgap. Likewise, IZO-6 has a lower optical bandgap despite its larger carrier density compared to IZO-2. The bandgap assumes its lowest value among doped films for the IZO-8. This behavior may be explained with the argumentation of Sans et al., who stated that heavy doping of ZnO materials with In introduces anti-bonding indium–oxygen states [23]. These hybridize with the ZnO conduction band and lead to a downshift of the optical bandgap. This downshift scales with the In concentration in the film which can compensate the Burstein–Moss widening and gives rise to the observed trend of the optical bandgap versus In doping.

Optimization of the film thickness

In the previous section, it was shown that the IZO-4 films offered the best combination of electrical and optical properties. Therefore, this doping concentration was chosen for further experiments. In the next step, the optical and electrical properties as a function of the film’s thickness were investigated. The thickness was varied in the range from 400 to 1600 nm. The target was to obtain films with sheet resistance values suitable for device applications (<50 Ω/sq.).

Figure 5a, b show cross-section and plane-view SEM micrographs of the 1600-nm-thick film. XRD analysis (Fig. 5c) revealed that the 400-nm film is not preferentially oriented, as multiple reflections showed similar intensity. The (110) texture became increasingly dominant with increasing film thickness. Figure 5d shows the peak area of the individual reflections as a function of the film thickness. While the (100) and the (101) reflections do not show a significant trend, a steady increase with the film thickness can be observed for the (103) and mostly for the (110) reflections. Thus, it can be concluded that in the first few hundred nanometers competitive crystal growth occurs in the film, from which the <110> direction emerges as the preferred growth orientation. Once this occurs, the films continue their growth along the <110> direction.

Independent of their thickness, the films remain highly transparent in the visible range, as can be seen in the transmittance spectra in Fig. 6. The average transmittance in the spectral range 400–1000 nm decreases on average by 2.6% per 400 nm thickness from initially 85.4 to 78.7% (Fig. 7a). The number of Fabry–Perot interferences increases, as expected, with increasing thickness, while the transmittance in the IR range decreases.

The resistivity shows a steady decrease from initially (1.2 ± 0.3) × 10−2 Ω cm (400 nm) to (5.0 ± 0.1) × 10−3 Ω cm (1600 nm) (Fig. 7a). Both the Hall carrier density and mobility of the thinnest film are significantly lower (Fig. 7b) compared to the other films, which explains the distinct drop in resistivity between the 400- and 800-nm-thick films. The reason might be alkali ions diffusion from the glass substrate to the films, as observed in the literature [11]. These ions act as acceptors in ZnO and can thus reduce the carrier density in the films [24]. The further decrease in resistivity for thicker films is mainly driven by the higher Hall mobility values. The mobility presents an almost twofold increase from 7.5 ± 0.6 to 13.1 ± 0.7 cm2/(V s) as the thickness increases from 400 to 1600 nm.

Stability under UV irradiation and increased temperature

The influence of UV exposure on the electrical properties of the deposited films was also investigated. As a semiconductor, ZnO increases its electrical conductivity when illuminated with photons with energy higher than its bandgap. The regular photoelectric effect occurs and disappears in a timescale of nanoseconds [25]. However, an additional, slower effect of the UV light on the resistivity can be observed in ZnO materials. Since this effect is built up and attenuated in a much larger time frame, it is often called “persistent photoelectric effect” in the literature. It can be explained by the following mechanism [25, 26]: electron–hole pairs are firstly generated by UV light absorption. The subsequent hole diffusion to the grain boundaries leads to an oxidation of the chemisorbed species present at these sites, which can lead to their desorption. Since only holes are consumed by this process, an accumulation of electrons in the crystal occurs and leads to an increase in the carrier density. In parallel, the grain boundary scattering is reduced and, thus, also the electron mobility is improved. The resulting decrease in the film’s resistivity can be, however, reversed by the re-adsorption of ambient gases, unless the film is efficiently sealed. This is the basic principle of UV annealing, which can offer a fast, low-temperature improvement in the conductivity of polycrystalline ZnO films [26].

The evolution of the films’ sheet resistance upon UV exposure is shown in Fig. 8. The samples were illuminated for 120 h, which corresponds to a dose of 12.1 kJ/cm2. The extent of the resistivity change strongly depends both on the carrier density and on the morphology of the films. The most significant change was observed for the undoped ZnO film, which showed a drop of the sheet resistance from an initial value of 42 to 2.04 kΩ/sq. The strongest reduction was observed in the first 7 h. The strong effect of UV exposure on the ZnO film can be explained by its high surface roughness, and consequently its high surface area, which facilitates both the desorption and re-adsorption of ambient gaseous species.

The IZO sheet resistance generally showed a much weaker dependence on the UV exposure, albeit with qualitatively similar features to the undoped film. The largest resistance decrease occurs in the beginning of the UV exposure. The sheet resistance of the IZO-2 was still declining at the end of the illumination period, similar to the undoped sample. The same is true for the IZO-8 sample but to a lower extent. The large resistance change for the IZO-2 sample might arise from the platelet-like morphology (Fig. 1) with increased grain boundary area. In contrast, the IZO-4 and IZO-6 samples show only a small resistance decrease during illumination. These are the films with a strong (101) texture, which additionally exhibited the highest carrier density. The smallest change in resistivity was observed for the 1600-nm-thick sample. Considering the limited penetration depth of the UV irradiation, only the strongly textured part of the film is likely affected.

The reduction in resistance did not reverse significantly even after 6 weeks, during which the materials have been stored in ambient conditions. The undoped ZnO and the IZO-2 showed an increase in sheet resistance from 2.04 to 3.2 kΩ/sq. and from 110 to 126 Ω/sq., respectively. The other materials, with higher In content, showed, however, only an increase smaller than 6% from their minimum resistance value.

In order to find the reason for this persistent effect, reflectance spectra of these samples were recorded in the infrared range, which are shown in Fig. 9.

In these spectra, absorbed species lead to a suppression of reflectance at certain wavenumber window, allowing a qualitative determination of their nature. This was, however, only feasible for the undoped sample. The vibrational modes are masked in the doped films by increased plasmon-related reflectance, arising from the increased free carrier density (Fig. 9c–f). Figure 9a shows the spectrum of the non-UV-exposed ZnO film, while Fig. 9b shows the film stored in ambient conditions for seven weeks after UV illumination, corresponding to the last measurement point in Fig. 8. The most prominent absorption peak is located at 1117 cm−1 and corresponds to the Si–O stretching vibration of the substrate (ν SiO) [27]. Further peak assignment was conducted according to the literature [28]. A broad minimum located around 3600 cm−1 is observed, which can be attributed to O–H stretching vibrations (ν OH). The out-of-plane deformation of this group can be observed as part of the broad depression around 1350 cm−1 (δ OH). This peak is enlarged in the insets in Fig. 9a, b. Especially, the inset in Fig. 9b shows that this feature is composed of at least two single contributions, as two local minima can be observed at 1290 and 1380 cm−1. The OH vibration is responsible for the minimum at lower wavenumbers, while the second contribution can be assigned to symmetric stretching vibration modes from adsorbed carboxylate species (ν s,COOH). Indeed, it might be possible that HAc adsorbs during the cooldown of the substrates in the deposition chamber. If this compound is really present, it should induce also an absorption peak via an asymmetric stretching mode around 1610 cm−1, where a minor depression can be observed (ν as,COOH). Thus, the spectra suggest possible adsorption of HAc, but judging from the corresponding peak sizes its significance appears to be minimal compared to the contribution of OH groups.

Comparing the ZnO spectra before and after annealing, it appears that the height of the hydroxide peaks is diminished after the UV annealing. Integrating both reflection peaks shows that the peak area is reduced by one-third. Chemisorbed water is known to heavily influence the electrical transport in polycrystalline ZnO films. [26] Thus, it appears that the long-lasting annealing effect can be at least partially explained by the desorption of chemisorbed water. The pronounced presence of OH vibrations in the as-deposited films can be attributed to the significant water partial pressure during synthesis, as water is used as solvent. This might lead to distinct chemisorption of water molecules in the production process. It appears that the activity of water under ambient conditions is not sufficient to restore the annealed samples back to their as-deposited state, even after the experiment period of 1350 h.

Last, the temperature stability was tested by heating a 1600-nm-thick IZO-4 film on a hot plate, in ambient atmosphere, at temperatures from 50 to 300 °C, with a step of 50 °C. The heating duration was 30 min at each step. For temperatures below or equal to 250 °C, we observed practically no change of the sheet resistance of the film. Only at 300 °C, the sheet resistance increased by approximately 5%. The thermal stability was further investigated by heating the film at 150 °C for up to 4 h. Again no change in the sheet resistance could be observed.

Implementation in a perovskite solar cell

Finally, the applicability of the IZO films was tested by integrating the 1600-nm-thick layer into a solar cell, employing methylammonium lead iodide/chloride (MAPbI3-xClx) as absorber material. The device was built in superstrate configuration onto the glass/IZO stack, as described in “Materials and methods” section. Figure 10a shows a cross-section SEM image of the solar cell stack, while Fig. 10b shows the corresponding current density–voltage (j–V) curves. A power conversion efficiency of 6% could be achieved with this architecture under AM 1.5G illumination, with a relatively high open-circuit voltage, V oc, of 910 mV, but a rather low short-circuit current density, j sc, of 11.27 mA/cm2. The low current density is not caused by the IZO electrode, as control devices with commercial ITO electrode (j–V curves also shown in Fig. 10b) show even lower j sc and degraded fill factor (FF). The moderate performance of the devices is attributed to the fast degradation of the non-encapsulated perovskite absorber due to the high ambient humidity. The commercial ITO electrode has a sheet resistance of ~10 Ω/sq., significantly lower than the one of IZO, giving rise to a faster increase in the current density at large forward bias values, inferring to a lower series resistance of the cell. We can conclude therefore that the developed IZO electrode is applicable to solar cell devices, even though other factors did not permit to obtain state-of-the-art cell performance. It is important to note also that, apart from the evaporated top Al contact, all other material components of the constructed solar cell are solution-processed.

Conclusion

Indium-doped and undoped zinc oxide thin films were grown by spray pyrolysis. ZnAc2 and In(acac)3 were used in a mixture of HAc and water, which gave rise to CVD-like growth at temperatures of 360 °C. The optimum solution recipe was found to consist of 8 vol% HAc and 4 at.% In(acac)3 in solution, which resulted in a dopant incorporation in the material of 3.6 at.%. With this recipe, a resistivity of (7.3 ± 0.6) × 10−3 Ω cm could be obtained for a film thickness of 800 nm. Hall measurements revealed a carrier density of (8.2 ± 0.4) × 1019cm−3 and a carrier mobility of 10.4 ± 1.1 cm2/(V·s). Increasing the layer thickness resulted in a decline in resistivity down to (5.0 ± 0.1) × 10−3 Ω cm, which could be mostly attributed to an increase in Hall mobility up to 13.1 ± 0.7 cm2/(V s). The (110) texture was obtained for sufficiently thick films of highest quality. These materials were also the most stable under UV illumination in terms of electrical resistivity. All samples showed a partially non-reversible decrease in their resistivity after the UV exposure, which can be attributed to the desorption of chemisorbed water. The optimized IZO film was used as a transparent electrode in a Pb-perovskite solar cell, obtaining power conversion efficiency of 6%.

References

Özgür Ü, Alivov YI, Liu C et al (2005) A comprehensive review of ZnO materials and devices. J Appl Phys 98:041301. doi:10.1063/1.1992666

Ellmer K, Klein A, Rech B (2008) Transparent conductive zinc oxide. Springer, Berlin

Perednis D, Gauckler L (2005) Thin film deposition using spray pyrolysis. J Electroceramics 14:103–111. doi:10.1007/s10832-005-0870-x

Major S, Banerjee A, Chopra KL (1983) Highly transparent and conducting indium-doped zinc oxide films by spray pyrolysis. Thin Solid Films 108:333–340. doi:10.1016/0040-6090(83)90082-2

Benouis CE, Benhaliliba M, Sanchez Juarez A et al (2010) The effect of indium doping on structural, electrical conductivity, photoconductivity and density of states properties of ZnO films. J Alloys Compd 490:62–67. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.10.098

Yan W, Tan J, Zhang W et al (2012) Tailoring the structure and properties of ZnO: in films by different kinds of acids. Mater Lett 87:28–30. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2012.07.061

Zaleta-Alejandre E, Camargo-Martinez J, Ramirez-Garibo A et al (2012) Structural, electrical and optical properties of indium chloride doped ZnO films synthesized by Ultrasonic Spray Pyrolysis technique. Thin Solid Films 524:44–49. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2012.09.050

Castañeda L, Maldonado A, Escobedo-Morales A et al (2011) Indium doped zinc oxide thin films deposited by ultrasonic spray pyrolysis technique: effect of the substrate temperature on the physical properties. Mater Sci Semicond Process 14:114–119. doi:10.1016/j.mssp.2011.01.013

Jiao BC, Zhang XD, Wei CC et al (2011) Effect of acetic acid on ZnO: in transparent conductive oxide prepared by ultrasonic spray pyrolysis. Thin Solid Films 520:1323–1329. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2011.04.152

Gómez H, Maldonado A, Asomoza R et al (1997) Characterization of indium-doped zinc oxide films deposited by pyrolytic spray with different indium compounds as dopants. Thin Solid Films 293:117–123. doi:10.1016/S0040-6090(96)09001-3

Castañeda L, García-Valenzuela A, Zironi EP et al (2006) Formation of indium-doped zinc oxide thin films using chemical spray techniques: the importance of acetic acid content in the aerosol solution and the substrate temperature for enhancing electrical transport. Thin Solid Films 503:212–218. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2005.12.263

Biswal R, Maldonado A, Vega-Pérez J et al (2014) Indium Doped Zinc Oxide Thin Films Deposited by Ultrasonic Chemical Spray Technique, Starting from Zinc Acetylacetonate and Indium Chloride. Materials 7:5038–5046. doi:10.3390/ma7075038

Wienke J, Booij AS (2008) ZnO: in deposition by spray pyrolysis — Influence of the growth conditions on the electrical and optical properties. Thin Solid Films 516:4508–4512. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2007.05.078

Kriisa M, Krunks M, Kärber E et al (2013) Effect of Solution Spray Rate on the Properties of Chemically Sprayed ZnO. In Thin Films. J Nanomater 2013:1–9. doi:10.1155/2013/423632

Vent M, Kärber E, Unt T et al (2012) The effect of growth temperature and spraying rate on the properties of ZnO: in films. Phys Status Solidi C 9:1604–1606. doi:10.1002/pssc.201200008

Edinger S, Bekacz J, Richter M et al (2015) Influence of the acetic acid concentration on the growth of zinc oxide thin films prepared by spray pyrolysis of aqueous solutions. Thin Solid Films 594(Part B):238–244. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2015.04.027

Paraguay DF, Estrada LW, Acosta NDR et al (1999) Growth, structure and optical characterization of high quality ZnO thin films obtained by spray pyrolysis. Thin Solid Films 350:192–202. doi:10.1016/S0040-6090(99)00050-4

Wu P, Gao Y-M, Kershaw R et al (1990) Growth and characterization of gallium (III) oxide films. Mater Res Bull 25:357–363. doi:10.1016/0025-5408(90)90108-E

Vai AT, Kuznetsov VL, Dilworth JR, Edwards PP (2014) UV-induced improvement in ZnO thin film conductivity: a new in situ approach. J Mater Chem C 2:9643–9652. doi:10.1039/C4TC01749H

Chen S, McLachlan M, Sapelkin A, Binions R (2015) Aerosol assisted chemical vapour deposition of transparent conductive ZnO thin films with hexagonal microplate surfaces and ultrahigh haze values. J Mater Chem A 3:22311–22315. doi:10.1039/C5TA06029J

Patterson AL (1939) The Scherrer Formula for X-Ray Particle Size Determination. Phys Rev 56:978–982. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.56.978

Tauc J (1968) Optical properties and electronic structure of amorphous Ge and Si. Mater Res Bull 3:37–46. doi:10.1016/0025-5408(68)90023-8

Sans JA, Sánchez-Royo JF, Segura A et al (2009) Chemical effects on the optical band-gap of heavily doped ZnO: M III (M = Al, Ga, In): An investigation by means of photoelectron spectroscopy, optical measurements under pressure, and band structure calculations. Phys Rev B 79:195105. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.79.195105

Park CH, Zhang SB, Wei S-H (2002) Origin of p-type doping difficulty in ZnO: the impurity perspective. Phys Rev B 66:073202. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.66.073202

Bao J, Shalish I, Su Z et al (2011) Photoinduced oxygen release and persistent photoconductivity in ZnO nanowires. Nanoscale Res Lett 6:404. doi:10.1186/1556-276X-6-404

Morfa AJ, MacDonald BI, Subbiah J, Jasieniak JJ (2014) Understanding the chemical origin of improved thin-film device performance from photodoped ZnO nanoparticles. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cells 124:211–216. doi:10.1016/j.solmat.2014.02.002

Agarwal A, Tomozawa M (1997) Correlation of silica glass properties with the infrared spectra. J Non-Cryst Solids 209:166–174. doi:10.1016/S0022-3093(96)00542-X

Fuchs P, Hagendorfer H, Romanyuk YE, Tiwari AN (2015) Doping strategies for highly conductive Al-doped ZnO films grown from aqueous solution. Phys Status Solidi A 212:51–55. doi:10.1002/pssa.201431145

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Graz University of Technology. This work was funded by the Austrian Climate and Energy Fund within the projects Flex!PV.at (project number: 838621) and flex!PV 2.0 (project number: 853603).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Edinger, S., Bansal, N., Bauch, M. et al. Highly transparent and conductive indium-doped zinc oxide films deposited at low substrate temperature by spray pyrolysis from water-based solutions. J Mater Sci 52, 8591–8602 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-017-1084-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-017-1084-8