Abstract

The current study addresses the formal and informal board leadership roles in new high-tech firms. Overall, we find that board leadership affects international engagements in idiosyncratic ways. Initially, we conjectured that the board leadership role structure would influence time to new markets, but the leadership role structure fails to do so, which indicates that neither a divided board leadership structure nor a dual board leadership structure matters. Instead, we find that the facilitating role of board chair leadership does. Although board chair leadership efficacy has a deliberating effect, we find it to have an interactive effect with a more resourceful board, indicating that efficacious leadership is more important than we typically would expect. Noteworthy, these dynamic interactions not only contribute to advancing new high-tech firms, but also contribute to shaping a resilient high-tech entrepreneurial ecosystem from within.

Resumen

El presente estudio aborda los roles de liderazgo formal e informal en los consejos de administración de las nuevas empresas de alta tecnología. En términos generales, apreciamos que el liderazgo del consejo afecta al compromiso internacional de forma idiosincrática. En principio suponíamos que la estructura del rol de liderazgo en el consejo influía en el tiempo que se tardaba en dirigirse hacia nuevos mercados, pero dicha estructura no parece afectarle. Esto indica que ni una estructura de liderazgo dividida ni una dual son relevantes. En cambio lo que descubrimos fue que el papel facilitador del liderazgo del presidente del consejo sí importa. Aunque la eficacia del liderazgo del presidente del consejo tiene un efecto deliberativo, se observa una interacción con un consejo con más recursos, lo que indica que el liderazgo eficaz es más importante de lo que se esperaba. Es relevante destacar que estas interacciones dinámicas contribuyen tanto al progreso de las nuevas empresas de alta tecnología como a desarrollar un ecosistema emprendedor de alta tecnología resiliente internamente.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Summary highlights

Contribution: This paper contributes to the literature on international entrepreneurship. Specifically, the paper contributes to our understanding of international entry under conditions near fundamental uncertainty, and as such, we contribute to the literature on whether to shape or adapt to the future.

The purpose of the paper: The study aims to better understand the role of board structural leadership in new entrepreneurial high-tech firms under conditions near fundamental uncertainty.

Research question: We direct our attention to board leadership structure, specifically, the informal and formal role structure of board leadership, and question how these structures matter in overcoming not only the liabilities of smallness but also the liability of foreignness in new high-tech firms.

Core method and data used: We make use of an event history methodology known as Cox regression. The data set is based on a survey questionnaire designed to uncover board work processes in high-tech new firms. The survey was conducted after a series of interviews with CEOs to fine-tune the survey questions.

Research findings: The findings are intriguing as we do not find that board leadership role structure affects the timing of entry into international markets. However, we find that efficacious board leadership has a deliberating effect on internationalization speed, but that the interactional dynamics with a resourceful board enhances the speed to international markets.

Theoretical implications: We find that an efficacious board chair interacting with resourceful board members is the most important factor when considering expansion. As such, the work adds to the resource dependency theory, but it also adds somewhat to the process view of entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Practical implications: The practical implications for aspiring high-tech new firms are to secure a chairperson who can recruit and interact efficaciously with a resourceful hoard.

Future research direction: Future studies may look into other role structures, and not only the formal board leadership structure. We found that an efficacious chairperson tended to deliberate more but was decisive when interacting with other board members. Future research may fruitfully elaborate to what extent a leader-based approach to board leadership is more effective than the follower-based approach, or is the relation-based approach even more effective?

Introduction

To provide a reasonable return on R&D investments, new technology-based firms seek growth to reach the critical mass they need. This growth predominantly comes from either product-related innovation or internationalization (Kyläheiko et al. 2011). In the case of the adoption of the latter strategy, the firm needs to undergo a rapid, immediate, and extensive internationalization. This is the defining feature of firms that in the internationalization literature have been labeled international new ventures (Aspelund et al. 2007).

An immediate, rapid, and extensive internationalization strategy is resource-demanding. Not only does it require financial resources to build effective and efficient international market channels, but it also requires access to human and market-related knowledge sources. In addition, the international market capabilities of the firm need to be built simultaneously as the entrepreneurs create the other necessary elements of the organization. This is often referred to as the double hurdles of international new venture formation (Liesch and Knight 1999). In order to overcome the double hurdles of international new venture foundation, entrepreneurs commonly use hybrid structures (Oviatt and McDougall 1994), business networks (Coviello 2006), or similar organizational arrangements to tap into human or market knowledge resources they need, but cannot afford to control through ownership.

In this stream of research, corporate governance has been given special attention because the board of directors can provide entrepreneurs access to resources normally out of their reach (Bjornali 2017; Bjornali and Aspelund 2012; Calabrò et al. 2009). In the current study, we address the formal and informal role of board leadership and look into the factors that contribute to unleash the services from board directors with heterogeneous expectations, typically formed by their imaginativeness and idiosyncratic life experiences. Specifically, we ask what role does directors from the wider entrepreneurial ecosystem play, and under what conditions are these directors useful? Ács et al. (2017) claim that “servant” leadership may be the mechanism that unleash the knowledge potential that resides in the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Such facilitating leadership is typically best enabled by “seasoned” entrepreneurs and may usually take the form as CEOs, dual CEOs, and/or as investors and board chairs.

In their process study of entrepreneurial ecosystems, Spigel and Harrisson (2017) point to “recycled” entrepreneurs that facilitate effective ecosystem operations, and they hold that entrepreneurial ecosystems can best be understood as “ongoing processes where entrepreneurs acquire resources, knowledge, and support, increasing their competitive advantage and ability to scale up” (p. 158), and that “well-functioning ecosystems depends on leadership from the entrepreneurial community” (p. 164). Henceforth, as Ács et al. (2017) point out, a facilitating leadership is not only vital for developing the entrepreneurial ecosystem, but could equally be crucial in facilitating growth and global entry engagements among new ventures.

Thus, this study aims to better understand board leadership in new technology ventures in relation to the emerging governance literature on new entrepreneurial firms (Garg 2020) applied to international entry. In particular, we direct our attention to board leadership role structure, specifically, the informal and formal role structure of board leadership, and how they matter in overcoming the liabilities of smallness and foreignness of new high-tech firms.

Contextual background

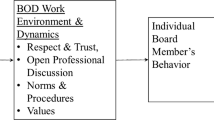

In a call for new directions in governance research, Garg (2020) states: “The venture context also provides a unique opportunity to explore the interplay of formal board structures and informal processes as business complexity changes with firm growth” (p. 260). In the current study, we perceive of boards as a social system involving not only leadership structure but also leadership roles. Specifically, we aim at unpacking the underlying interactional dynamics, and especially the mechanisms of board deliberations that are not immediate salient, but nonetheless present, and difficult to capture (Kakabadse and Morley 2021). The contents of these deliberations are difficult to capture because they comprise multiple judgments over multiple processes, involving known, unknown, and unknowable uncertainties (Packard and Clark 2020).

In many ways, we depart from Peng (2004a, 2009) “What determines the international success and failure of firms?”, where his take on these matters is with formal and informal institutional lenses. Peng (2004b) also employed insights from resource dependency theory (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978), and we note that board leadership structure is a matter of formal institutions (regulated by the law), and informal institutions reflect what one “ought” to do, based on norms and expectations. As such, the deliberation processes may be guided by not only formal but also informal institutions not very different from those role structures elaborated by Ma et al. (2021) who conceptually explored the formal and informal role structure of top management teams—that is, the role structures between the CEO and the other top management team members (e.g., CTOs, CFOs, and CIOs).

In contrast, we address the formal and informal role structure of the CEO-board relationships and assess how they relate to critical strategic decisions such as international engagement, and entry, and we do so under conditions of true or fundamental uncertainty.

Alvarez and Porac (2020: 742) state that “managing under fundamental uncertainty is a very different animal compared to managing under more predictive environments” because knowledge and routine contingencies have yet to be identified. With new firms, based on new technology, launched in international markets, we arguably have a situation we may label as fundamental uncertainty, at least an unarticulated uncertainty, a type of uncertainty that we do not have a good language for. Approaching such uncertainties require competence and tactfulness. Ehrig and Foss (2022) contend that there are insights in decision-making that look into how decision-makers cope with the unknown unknowns. They point to belief revision theory from the cognitive sciences and relate it to the firm level and to the adaptation mode.

In contrast, we address what Wiltbank et al. (2006) label the transformation mode. Wiltbank et al. (2006: 983) hold that firms in the adaptive mode need to “move faster to a rapidly changing environment,” whereas firms in the transformative mode “transform current means into co-created goals with others who commit to building a possible future.” Henceforth, instead of adapting to an environment, we elaborate the active shaping of it, as has also been highlighted by Rindova and Courtney (2020), and we address the deliberations that facilitates those processes. Etemad (2007, 2019) indicates that knowledge, or technology (based on new firms), could be influential factors in accelerating such processes.

Finally, we draw on the observational insights from Leblanc (2005) when we link the facilitating role of the board chair to external board members and international engagement. Our underlying conjecture is that entrepreneurial actions within the unknown and the unknowable require (1) a core leadership structure and (2) and a deliberating process—a tactfully and transformative belief revision process with others that commit to build a possible future—in where Leblanc (2005) points to the engaged chairperson. It is the engaged chairperson, that together with board members from the entrepreneurial ecosystem that shapes the environment. By introducing a new service or a new product, one contributes to shaping the environment.

Hypotheses

In what follows, we develop two hypotheses, one that relates to the more formal board leadership structure, and the other relating more to the informal deliberation processes facilitated by the chairperson in the formal role, within the context of fundamental uncertainty.

For the first hypothesis, we draw on contrasting insights from both stewardship and agency theory regarding board leadership structure, as such leadership structure contributes to shape an otherwise uncertain decision-making environment, before we develop the second hypothesis with insights from resource dependency theory (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978).

The formal role, board leadership structure

In a meta-analysis of board composition, Dalton et al. (1998) found that the structural leadership dimension of the boards fails to be consistently linked to firm performance. As a meta-analytical finding, this is a substantive insight that carries weight. Nonetheless, Li et al. (2018) assert that future studies could usefully investigate different aspects of board leadership in entrepreneurial firms. Given the challenges affiliated with internationalization, the relationship between leadership structure and internationalization, and not least the leadership’s timing of the internationalization processes, and thus the speed to those international markets, are beneficial and useful to understand better. At least for knowledge-intensive new firms that are rather specialized, such as new high-tech firms.

Drawing on core theoretical approaches dealing with these leadership role structures, we recognize that there are at least two ways of understanding this issue, one way is through stewardship theory, the other through agency theory. While the theoretical underpinnings of stewardship theory are psychological and sociological considerations, the theoretical underpinnings of agency theory are not only economic, but also juridical considerations. Whereas agency theorists would typically argue against CEO duality, holding that the concentration of power would likely be exploited, stewardship theorists, in contrast, would typically argue that a CEO could productively take the role as chairperson. That is, the two management approaches prescribe contradictory solutions. Stewardship theorists prescribe that the firm would benefit from the dual leadership structure, whereas agency theorists would argue otherwise (Donaldson and Davis 1991; Davis et al. 1997).

In smaller firms, and in an entrepreneurial setting, the stewardship approach is likely to prevail due to effectiveness in decision-making. Henceforth, we have reason to believe that the dual leadership structure (that is, the CEO duality—the “one person, two roles” situation) will be beneficial for new high-tech firms as it facilitates some leeway to what Hambrick and Mason (1984) labeled “managerial discretion”—the freedom to act and operate as the CEO deem right, and benefit from the decision-making autonomy embedded in the affiliated power that comes along such positions. CEO duality is advantageous for decision-making speed (Hambrick 2007). In smaller open economics with limited domestic markets, like Norway, entering international markets may be a prerequisite for survival, and we expect that time to international markets will be shaped, in part, by the overall leadership structure of the new firms.

However, we do not know with regard to internationalization, as it may very well be that a divided leadership structure is better. Our main point is that leadership structure ought to matter for the reasons argued above. Henceforth, we therefore conjecture that the leadership structure of the board will affect the timing to engage with international markets. Accordingly, we set forth the following overall hypothesis that we address in this paper:

-

Hypothesis 1: Board leadership role structure will affect the timing to international markets.

The informal role in the formal, the role of facilitating board leadership

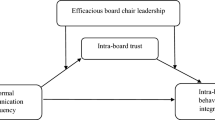

As above, the role of the board chair is also a formal role, and the role shapes the nature of the working relationships among the board members. Although the chairperson has a formal role, the type of leadership associated with this role may be informal. That is, the inherent behavioral capacity to facilitate joint action (Tourish 2014), to engage the board members, and to draw on their competencies, and make the most out of those capabilities (Graen and Uhl-Bien 1995) may be regarded as an informal quality of the chairperson, especially under conditions of fundamental uncertainty (new high-tech firms in new international markets).

Machold et al. (2011) find that board chair leadership efficacy positively influences board strategy involvement. They also find that efficacious leadership is a determinant of constructive team production in the boardroom, and they also refer to Leblanc and Gillies’s (2005) insights who hold that board leadership is the single most important factor for an engaged board. In particular, Leblanc asserts that “the leadership skills of the chair of a board of directors have a direct impact upon the effectiveness of that particular board” (p. 654). He recognizes that this is a qualitative assertion and that we so far do not have quantitative evidence to back such a claim. Leblanc further goes on and argue that:

…the choice of the chair of a board and the effectiveness of that chair once in the position could be considered to be the most important decision that a board of directors makes, other than selecting the CEO. It is doubtful that a strong, engaged board will have a weak chair or an ineffective board will have a strong chair. Board and chair effectiveness go hand-in-hand. (2005, p. 655).

In the current study, board leadership efficacy relates to the board chair’s capacity to facilitate board deliberations and to enact the outcome in the environment. In the context of high-tech firms in smaller countries, international activities are inevitable to reach appropriate markets, but the complexities involved in new technology and new markets are challenging. We must assume that such deliberations comprise multiple judgments over multiple processes, involving multiple uncertainties from the known to the unknowable (Packard and Clark 2020).

Since multiple layers of uncertainties are involved, the resulting multiplexity gravitate not only around the unknown but also the unknown unknowns. Ehrig and Foss (2022: 2) define the unknown unknowns as “future contingencies that lack an ex ante description for at least some decision makes that are later affected by the contingencies.” In other words, many relevant issues are unarticulated and not actually present in the minds of the decision-makers.

A chairperson who is tactful in chairing discussions and using board member’s competencies will draw on their facilitating skills and enable sound deliberations (Kanaldi et al. 2018). Along these lines, a board chair may not rush into, but choose to withhold international activities if the firm is not yet prepared. That is, a chair may consider multiple ways of growth, and may therefore deliberate carefully, and thus choose to withhold international activities if that is considered appropriate. Such an international effort may also reflect an ambidexterity strategy where they explore potential growth opportunities (Mihalache et al. 2014). That is, it is reasonable that an efficacious chairperson will explore and consider international market entry when the circumstances are deemed right—before they exploit the opportunity. Mihalache et al. (2014) found that a shared leadership facilitated ambidexterity. In a similar vein, a facilitating leadership with the board members may yield similar results. That is, careful deliberations may impede the speed to new markets, whereas the mere interaction, that is, the dynamic interaction with board members is speeding up the deliberation process.

Hence, we conjecture that an efficacious board chair will not only deliberate and carefully consider international market opportunities, but also actively explore and engage with, and draw on, the relational ties of heterogeneous, and therefore, resourceful board members, and facilitate interdependent knowledge sharing processes that affect the speed to international markets. Accordingly, we set forth the following interdependency related hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 2: Efficacious board leadership will positively interact with the relationship between available board resources and the timing to enter international markets. Specifically, skillful interactions with other board members will speed up the time to international markets.

Methods

The study is based on a survey study among Norwegian high-tech firms between 2015 and 2018. The sample reflects all high-tech start-ups satisfying the high-tech NACE categories. The selection criteria were that the businesses had to fit two main NACE categories “high-tech knowledge-intensive service” and “high technology.” After selecting firms that satisfied the choice criteria, we ended up with 761 firms. Consistent with calls to use surveys to assess actual board behaviors (Clarysse et al. 2007; Aaberg and Shen 2020), we sent structured questionnaires to the CEOs of those firms. The overall survey had a response rate of 20%, which is typical for this kind of studies. From the total of 149 responses, we could only use 73 of them due to many missing values.

CEOs filled out the questionnaire answering questions about the firm, the leadership structure, and the board. CEOs represent accurate informants in this context because they commonly have the best knowledge of a start-up’s history, performance, process, and culture (Knockaert et al. 2015), and have direct contact with the board (Huse 2007). Challenges with accessing board data from the board room are major setbacks in the development of board behavioral research (Lorsch 2017; Leblanc and Schwartz 2007). Therefore, we deemed first-hand information from CEOs a valid proxy to understanding board dynamics, rather than relying on information found in archives. The survey was pretested by interviewing twenty CEOs during 2014 and 2015, and the survey has been reported to, and approved by, the Norwegian Social Science Data Services and thus complies with ethics and personal data protection requirements—equivalent to the new GDPR data protection requirements in Europe.

We corroborated information on CEO duality, firm age and size, and industry obtained from the questionnaire by checking available data in the company databases. Further, we tested for differences between responding and non-responding firms on archival data variables (i.e., firm size, age, and sales volume). We were also able to collect information on 46 companies that declined to participate. T-test results did not suggest statistically significant differences in mean values for sales volume and firm size but revealed differences regarding firm age. Taken together, our results suggest a probable response bias in that more mature companies were reluctant to participate in the survey, and thus, our results pertain to younger high-tech firms. Most of these high-tech firms stem from the oil and gas industry, and ICT industries, followed by renewable and environmental technology. The average firm age in the sample is 7.83 (s.d. 3.35) years old. The average size of the firms at the time of measurement is 6.62 employees, (s.d. 10.77), and the average number of board members is 4.16 members (s.d. 1.20).

Analytical methods applied

For the statistical analysis, we employed a Cox regression for an event history analysis. When assessing how leadership structure and leadership agency influence speed to enter international markets, an event history approach is appropriate (Lee 1980; Smith 2002). Event history models consider not only the occurrence and timing of an event, but also contribute to estimating the effects of the other variables involved (Heirman and Clarysse 2007). For instance, if the firm fails before the internationalization process starts, or if the firm has not started the internationalizing process before the study period is over, they are right censored. By employing the amount of time before internationalization as the dependent variable, the analysis produces biases (Sørensen 1977; Tuma and Hannan 1978). Employing just the status variable international activity (Yes/No) would exclude data about internationalization on both sides of the study period. However, the event history model that we employ, Cox regression, deals with these issues by making use of not only the measured activity (dummy-coded international activity), but also years of operation prior to internationalization in constructing the hazard rate.

Thus, the method is not only appropriate as it alleviates the weaknesses of the two approaches mentioned, but it is, to our knowledge, the best method available. That is, the Cox proportional hazard model is the most frequently employed distribution-free regression model for the analysis of censored data (Heirman and Clarysse 2007). The hazard ratios, or the relative risks, are reported with standard errors in parentheses. To assess our two leadership hypotheses, two Cox proportional hazard models were estimated using different dependent variables. One with time to international agreement, and the other one with time to first international sale. Both models exhibit roughly the same results, indicating that the findings are robust across measurements. As for measurement issues, and common methods biases, we note that reverse causality should not be an issue here, and with lagged internationalization data, we should neither have any endogeneity issues. Building on Evans (1985), Siemsen et al. (2010: 470–472) show analytically that interaction effects cannot be artifacts of common method bias (or variance). Specifically, they emphasize that “empirical researchers should not be criticized for CMV if the main purpose of their study is to establish interaction effects. On the contrary, finding significant interaction effects despite the influence of CMV in the data set should be taken as strong evidence that an interaction effect exists” (p. 470).

Measurements

The dependent variables

In the current study, we captured the dependent variable in the following way. We asked CEOs whether their firms have had international activities (coded as “1” if yes, otherwise “0”). Further, we asked in which country, and when (if possible to date), the firm made the first strategic agreement and/or first sale outside Norway. We then calculated Time to first international sale by subtracting the year of the firm inception from the year of first international sale. Likewise, we did the same with the Time to first international agreement variable. Since the sample of start-ups contained firms that exhibited various development stages, the latest being without international sales yet, these dependent variables proved to be appropriate in this context and have been used in previous studies (Bjornali and Aspelund 2012).

The independent variables and the moderator variable

We measured board leadership structure and we measured Board chair leadership efficacy. Board leadership structure is measured by employing the CEO duality variable. CEO duality was coded as “1,” otherwise as “0.” As the moderator, board chair leadership efficacy was measured by means of three items employed by Machold et al. (2011), that derives from Huse (2007, 2009). The chairman’s leadership efficacy was measured by asking the CEO to rate the following three items on a 7-point scale: Our board chair is especially skilled in (a) motivating and using each board member’s competence, (b) formulating proposals for decisions and summarizing board negotiation, (c) chairing board discussions without promoting his/her agenda. Note that this efficacy construct captures the board chair’s ability to facilitate and mobilize board members. It facilitates for what we may perceive as the informal deliberation processes itself, among board members that generate heterogeneous expectations formed by their unique imaginative faculties and based on their idiosyncratic life experiences. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale is .833, and the average variance extracted (AVE), and the composite reliability (CR) are both .811. All these three indices are well within their threshold limits.

The control variables

We counted the number of board members, as well as the year of firm inception, and then calculated time since inception. We included these two measures as control variables as they reflect viable resources underlying the venturing initiative. The number of board members are significant resources as they are foundational and specific to the firm. We assume that each member brings in heterogeneous expectations formed by their imagination and life experience.

A summary of all the variables and the affiliated metrics is provided in Appendix Table 3.

Analysis and results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the variables included in this study. Additional comparative analysis shows that the average firm age of those that have internationalized is 8.02 (s.d. 3.26), and for those that have not yet internationalized is 7.26 (s.d. 3.63), and the difference with regard to CEO duality is almost negligible with .17 (s.d. .38) for those that internationalize, as compared to those that do not (.16, s.d. .37). Most of these firms crossed-bordered in countries such as the USA, UK, Sweden, and Germany. Other less frequent mentioned cross-bordered countries are Australia, Bangladesh, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Denmark Finland, France, Greece, Holland, Indonesia, Ireland, Malaysia, Poland, Russia, Saudi-Arabia, South Africa, and Switzerland.

As for the event history analyses, both Cox proportional hazard models reflect roughly the same results, indicating that the findings are robust across dependent variables. Model 1 and model 2 in Table 2 disentangle the dynamics that matter about speed to international markets, and both models are significant, deemed by their goodness of fit values. Our conjectures where that formal board leadership structure matters and that informal board leadership processes do. We find that board leadership structure does not matter with regard to international engagement. However, we find that board resources play a role in speed to international markets. It is not the amount of board resources, or the leadership efficacy itself, but the interaction between these resources that matters. In other words, a “servant” board chair will typically deliberate and withhold excessive activities until sufficient resources are in place. Such activities could be international activities, as they would necessarily require more attention to deploy. It is neither the amount of board members that matters, as the number of board members relates negatively. It is their dynamics that matters—the dynamics between board members and an efficacious board leader. Henceforth, it is the context and content of these dynamics that should be in focus.

Model 1 and 2 in Table 2 do not indicate support for hypothesis 1 about the leadership structure of the firm (Exp(B) = 1.768; p > .05, and Exp(B) = 1.347; p > .05), although we find support for hypothesis 2 that efficacious leadership interact with a resourceful board (Exp(B) = 1.306; p < .05 and Exp(B) = 1.357; p < .05). Henceforth, we have support for the facilitating related moderation hypothesis, although the facilitating leadership skill itself independently decreases time to international markets (Exp(B) = .315; p < .05) and Exp(B) = .249; p < .01).

Discussion and implications

Extraordinary outcomes are often the result of careful deliberations. Actively involving board members in the deliberation process rather than the final decisions will not only benefit the focal firm, but also their stakeholders, which is considered good stewardship.

Interestingly to note, we do not find that board leadership role structure effects the timing of entry into international markets. However, we find that efficacious board leadership interacting with a resourceful board facilitates not only valuable deliberations, but also what we may understand with good stewardship. Whereas stewardship theory claims that the CEO and the board chair could positively be the same person (Davis et al. 1997), many studies, among them the meta-analytical study by Dalton et al. (1998), as well as the current study, are inconclusive concerning the effects of CEO duality, but we find that skillful board leadership interacting with the board members matters with the timing of international entry, regardless of the leadership structure.

Based on the findings of this study, we corroborate Leblanc’s (2005) observational insights, when he claims that the board chair is the single most important factor of a resourceful board, as he asserts that “the leadership skills of the chair of a board of directors have a direct impact upon the effectiveness of that particular board” (p. 654). And as Leblanc claims, it is doubtful that a strong engaged board will have a weak chair, or that an ineffective board will have a strong chair. Indeed, our data supports the conjecture that an efficacious board chair interacting with other board members is the single most important factor, if not the most important factor in shaping and timing international entry in knowledge-intensive new firms.

Implications are that discretional leadership processes matters, and not least, these dynamics matter when a resourceful board under conditions of unknown and unknowable uncertainty relate to multiple judgments over multiple processes. Could the leader-member exchange theory (known as LMX) also be applicable to board chairs and board members as the form of leadership styles apparently make a difference (Graen and Uhl-Bien 1995)? We may ask, is such leader-based approach to board leadership more effective than the follower-based approach, or is maybe the relation-based approach to board leadership the most optimal in these settings? Particularly, what we have investigated is not the relation-based approach to leadership, but something in between the leader-based approach, and, the follower-based approach, where the chairperson draws on, and “makes the most of follower’s capabilities” (Graen and Uhl-Bien 1995: 224). Although the LMX theory does not distinguish between transactional and transformational leadership (Bass 1990), the latter leadership style has been claimed to relate to creativity (Castro et al. 2008) and may therefore serve to facilitate more creativity and thus innovations in the boardroom (Garg 2020), facilitating more divergent thinking processes, but this is just a speculation.

Board deliberations may also be affected by the type of ties the board members have (their external social capital), whether they have multiple “outgoing” or “incoming” board interlocking ties, and the number of such ties, and the strengths of those ties apparently seems to matter. For instance, Yildiz et al. (2021) find that hands-on experience coming from incoming ties is more effective in facilitating international engagement, once these ties are strengthened. How does the multiplexity of such ties relates to the formal and informal role structure of the board? As Yildiz et al. (2021) found that experience coming from incoming ties was more effective in facilitating international engagement once these ties were strengthened, is that what happened in the interaction between board chairs and board members? Currently, we do not know, but it is a promising avenue for further research. Yet, we may speculate, as it is within the nexus of board leadership interacting with heterogeneous expectations from “seasoned” or “recycled” individuals, serving as board members with unique imaginative faculties, that the initial internationalization beliefs are reconsidered and revised.

As firms are in different stages, and have different levels of complexities, and operates in different countries with different legislations and business contexts, also regarding board role responsibilities, and depending on the degree of formal institutions, we may see different optimal arrangements. Legislations regarding board responsibilities and their conduct may vary, and the generalized trust level differ between countries, as well do their cultures. For instance, Norway is a high generalized trust country, and score high on future orientation, but low on power distance and assertiveness (Javidan et al. 2006). We call for more research in a cross-national setting to investigate the effects of those factors on the contribution of boards.

For new high-tech firms entering international markets, the board leadership structure seems to be of less importance. However, what seems to be important is the role of the chairperson, and the leadership practiced—the form of interaction that the chairperson has with the board members. Indeed, our study has weaknesses, and the next section addresses those that we have identified, along with recommendations for future research on leadership in high-tech new firms with cross-border entry ambitions, with an entrepreneurial ecosystem twist to it.

Study limitations and future research

Although the study is based on a robust event history analytical framework, it lacks the contextual richness that more qualitative studies typically facilitate. It is perhaps as Kakabadse and Morley (2021) suggest phenomenological or ethnographic studies could facilitate deeper insights into the leadership dynamics, as a phenomenological epistemology acknowledges that the human experience is complex and may be understood from different viewpoints (Bjornali et al. 2017). For instance, the LMX theory could unpack the multiplexity of the dyadic relationships, and the multiplexities of “incoming” ties (Yildiz et al. 2021) and unpack the potential of joint commitments between board chairs and board members to build a possible future.

Indeed, a shortcoming is the survey methodology employed, as we were only able to show that the interaction between efficacious leadership and the number of board members matters.

Basically, we captured the characteristic of what Leblanc (2005) labeled an “engaged” board. Given that we dealt with a situation with unknown and unknowable uncertainty, it may also be that the time is right to explore design heuristics and focus less on what Bingham and Eisenhardt (2011) labeled as decision heuristics. That is, we did not capture to what extent the deliberations relied on convergent or divergent thinking processes, or what Gilbert-Saad et al. (2018) label as design heuristics which matter under conditions of true or fundamental uncertainty. Future studies may therefore seek to explore to what extent such deliberations are grounded in convergent or divergent thinking processes as we lack insights into the type of deliberations that are taking place regarding international entry engagements and their timing.

Future studies could also seek to disentangle what type of decision-making heuristics, or design heuristics, that are used when the board faces unknown and unknowable uncertainty as is the case when early-stage high-tech firms make international strategy decisions. Whereas fundamental uncertainty may be broken into cross-sectional uncertainty (also known as Akerlofian uncertainty), and longitudinal uncertainty (known as Knightian uncertainty), how these two types of uncertainties relate to board leadership remains unclear. Dew et al. (2004) conceptually delineated their differences, whereas Leunbach et al. (2019) and Leunbach et al. (2020) found these concepts useful when building on insight from Foss and Klein (2012), and Foss et al. (2008) and their judgment approach with an “Austrian” take.

Future studies could also seek to relate board leadership structure and the affiliated roles to the emerging topic of venture governance (Garg 2020), as that literature is void of topics such as speed to markets, not least speed to international markets. For instance, future studies could try to investigate what Garg and Eisenhardt (2017: 1837) label the dyadic relationship between the leaders and board members. In particular, how leaders work with the board members on a “one-on-one basis to develop a partnership with each one of them” (Graen and Uhl-Bien 1995: 229), not unlike the dyadic recommendations of Garg and Eisenhardt (2017).

To what extent are transformational leadership approaches employed? Or are transactional leadership processes more suitable in other cases? Given the dyadic relationship, could transformational leadership be practiced in one dyad, whereas transactional leadership in another? Furthermore, maybe a well-functioning board should not be seen in light of how well behaviorally integrated they are as a team (Erikson et al. 2022), but instead how effective the dyadic working relationship between the board chair and the different board members are?

In the current study, we took a follower-based approach to board leadership. This is an approach where the board members lead the way under competent facilitation of a chairperson. As such, we also contribute to the process perspective of entrepreneurial ecosystems showing that “servant” leadership from chairpersons is useful in recycling “seasoned” entrepreneurs from the adjacent entrepreneurial ecosystem. The competence and network of these board members typically draws on the “local resources, support, and financing” that helps grow “new ventures into globally competitive firms” (Spigel and Harrisson 2017: 152). We found that an “engaged” board—and the leadership that facilitated it—was crucial in dealing with the multiplexities of the uncertainties involved. Although these activities at first sight may be seen as resource flow out of the ecosystem, it is in fact strengthening the entrepreneurial ecosystem, making it more resilient, as the new high-tech ventures grows into globally competitive firms.

References

Aaberg C, Shen W (2020) Can board leadership contribute to board dynamic managerial capabilities? An empirical exploration among Norwegian firms. J Manage Governance 24(1):169–197

Ács ZJ, Stam E, Audretsch DB, O’Connor A (2017) The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Bus Econ 49(1):1–10

Alvarez SA, Porac J (2020) Imagination, indeterminacy, and managerial choice at the limit of knowledge. Acad Manage Rev 45(4):735–744

Aspelund A, Madsen TK, Moen Ø (2007) International new ventures: review of conceptualizations and findings. Europ J Mark 41(11/12):1423–1474

Bass BM (1990) Bass & Stogdill’s handbook of leadership. Free Press, New York

Bingham CB, Eisenhardt KM (2011) Rational heuristics: the ‘simple rules’ that strategists learn from process experience. Strategic Manage J 32:1437–1464

Bjornali ES (2017) Research on the board of directors in high-tech start-ups: an assessment and suggestions for future research. In: Gabrielsson J (ed) Handbook of research on corporate governance and entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp 111–142

Bjornali ES, Knockaert M, Foss N, Leunbach D, Erikson T (2017) Unraveling the black box of new venture team processes. In: Ahmetoglu G, Chamorro-Premuzic T, Klinger B, Karcisky T (eds) The Wiley handbook of entrepreneurship. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK, pp 317–353

Bjornali ES, Aspelund A (2012) The role of the entrepreneurial team and the board of directors in the internationalization of academic spin-offs. J Int Entrep 10:350–377

Calabrò A, Mussolino D, Huse M (2009) The role of board of directors in the internationalisation process of small and medium sized family businesses. Int J Global Small Bus 3(4):393–411

Castro CB, Periñan MMV, Bueno JCC (2008) Transformational leadership and followers’ attitudes: the mediating role of psychological empowerment. The Int J Human Resource Manage 19(10):1842–1863

Clarysse B, Knockaert M, Lockett A (2007) Outside board members in high-tech start-ups. Small Bus Econ 29(3):243–259

Coviello NE (2006) The network dynamics of international new ventures. J of Int Bus Studies 37(5):713–731

Dalton DR, Daily CM, Ellstrand AE, Johnson JL (1998) Meta-analytic reviews of board composition, leadership structure, and financial performance. Strategic Manage J 19(3):269–290

Davis JH, Schoorman FD, Donaldson L (1997) Toward a stewardship theory of management. Acad Manag Rev 22(1):20–47

Dew N, Velamuri SR, Venkataraman S (2004) Dispersed knowledge and an entrepreneurial theory of the firm. J Bus Venturing 19(5):659–679

Donaldson L, Davis JH (1991) Stewardship theory or agency theory: CEO governance and shareholder returns. Australian J Manage 16(1):49–64

Ehrig T, Foss N (2022) Unknown unknowns and the treatment of firm-level adaptation in strategic management research. Strategic Manag Rev 3(1):1–24

Erikson T, Coleridge C, Bjornali ES (2022) Venture governance and its dynamics: intraboard relationships and CEO duality. Technovation 115:102540

Etemad H (2019) Actions, actors, strategies and growth trajectories in international entrepreneurship. J Int Entrep 17:127–143

Etemad H (2007) The fastest growing SMEs in Canada: their strategies, e-commerce and network practices, Chapter 7. In: Susman G (ed) Small and medium-sized enterprises and the global economy. Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 103–124

Evans MG (1985) A Monte Carlo study of the effects of correlated method variance in moderated multiple regression analysis. Organ Behav Human Decision Process 36:305–323

Foss NJ, Klein PG (2012) Organizing entrepreneurial judgment: a new approach to the firm. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Foss NJ, Klein PG, Kor YY, Mahoney JT (2008) Entrepreneurship, subjectivism, and the resource-based view: toward a new synthesis. Strategic Entrep J 2(1):73–94

Garg S (2020) Venture governance: a new horizon for corporate governance. Acad Manage Perspect 34(2):252–265

Garg S, Eisenhardt KM (2017) Unpacking the CEO–board relationship: how strategy making happens in entrepreneurial firms. Acad Manage J 60(5):1828–1858

Gilbert-Saad A, Sidelok F, McNaugthon RB (2018) Decision and design heuristic in the contect of entrepreneuriual uncertainties. J Bus Venturing Insights 9:75–80

Graen GB, Uhl-Bien M (1995) Relationship-based approach to leadership: development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quart 6(2):219–247

Hambrick DC (2007) Upper echelons theory: an update. Acad Manage Rev 32(2):334–343

Hambrick DC, Mason PA (1984) Upper echelons: the organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad Manage Rev 9(2):193–206

Heirman A, Clarysse B (2007) Which tangible and intangible assets matter for innovation speed in start-ups? J Product Innovation Manage 24:303–315

Huse M (2007) Boards, governance and value creation: the human side of corporate governance. Cambridge University Press

Huse M (2009) The value creating board: corporate governance and organizational behaviour. Routledge

Javidan M, Dorfman PW, Sully de Luque M, House RJ (2006) In the eye of the beholder: cross cultural lessons in leadership from project GLOBE. In: Readings and cases in international human resource management. Routledge, pp 67–90

Kakabadse NK, Morley MJ (2021) In search for stewardship: advancing governance research. Eur Manage Rev 18:189–196

Kanaldi SB, Torchia MT, Gabaldon P (2018) Increasing women’s contribution on board decision making: the importance of chairperson leadership efficacy and board openness. Eur Manag J 36(1):91–104

Knockaert M, Bjornali ES, Erikson T (2015) Joining forces: top management team and board chair characteristics as antecedents of board service involvement. J Bus Venturing 30(3):420–435

Kyläheiko K, Jantunen A, Puumalainen K, Saarenketo S, Tuppura A (2011) Innovation and internationalization as growth strategies: the role of technological capabilities and appropriability. Int Bus Rev 20(5):508–520

Leblanc R (2005) Assessing board leadership. Corporate Governance: An Int Rev 13:654–666

Leblanc R, Gillies J (2005) Inside the boardroom: how boards really work and the coming revolution in corporate governance. Wiley, Toronto

Leblanc R, Schwartz MS (2007) The black box of board process: gaining access to a difficult subject. Corporate Governance 15(5):843–851

Lee ET (1980) Statistical methods for survival data analysis. Lifetime Learning Publications, Belmont, CA

Leunbach D, Erikson T, Bjornali ES (2020) A subjectivist approach to team entrepreneurship. Quarterly J Austrian Econ 23(3-4):542–567

Leunbach D, Erikson T, Rapp-Ricciardi M (2019) Muddling through Akerlofian and Knightian uncertainty: the role of sociobehavioral integration, positive affective tone, and polychronicity. J Int Entrep 18:1–20

Li H, Terjesen S, Umans T (2018) Corporate governance in entrepreneurial firms: a systematic review and research agenda. Small Bus Econ 54(1):43–74

Liesch PW, Knight GA (1999) Information internationalization and hurdle rates in small and medium entreprise internationalization. J Int Bus Studies 30(2):383–390

Lorsch JW (2017) Understanding boards of directors: a systems perspective. Annal Corporate Governance 2(1):1–49

Ma S, Kor YY, Seidl D (2021) Top management team role structure: a vantage point for advancing upper echelons research. Strategic Manage J:1–28

Machold S, Huse M, Minichilli A, Nordqvist M (2011) Board leadership and strategy involvement in small firms: a team production approach, corporate governance: An. Int Rev 19(4):368–383

Mihalache OR, Jansen JJP, Van den Bosch FAJ, Volberda HW (2014) Top management team shared leadership and organizational ambidexterity: a moderated mediation framework. Strategic Entrep J 8(2):128–148

Oviatt BM, McDougall PP (1994) Toward a theory of international new ventures. J Int Bus Studies 25(1):45–64

Packard MD, Clark BB (2020) On the mitigability of uncertainty and the choice between predictive and nonpredictive strategy. Acad ManageRev 45(4):766–786

Pfeffer J, Salancik GR (1978) The external control of organizations: a resource dependence perspective. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship

Peng MW (2009) Global Strategy, Cengage, MA., USA

Peng MW (2004a) Identifying the big question in international business research. J Int Bus Studies 35(2):99–108

Peng MW (2004b) Outside directors and firm performance during institutional transitions. Strategic Manage J 25:453–471

Rindova VP, Courtney H (2020) To shape or adapt: knowledge problems, epistemologies and strategic postures under Knightian uncertainty. Acad Manage Rev 45(4):787–807

Siemsen E, Roth A, Oliveira P (2010) Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organi Res Methods 13(3):456–476

Smith PJ (2002) Analysis of failure and survival data. Chapman and Hall, Washington DC

Spigel B, Harrisson R (2017) Toward a process theory of entrepereneurial ecosystems. Strategic Entrep J 12(1):151–168

Sørensen AB (1977) Estimating rates from retrospective questions. In: Heisse DR (ed) Sociological methodology. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Tourish D (2014) Leadership, more or less? A processual, communication perspective on the role of agency in leadership theory. Leadership 10(1):79–98

Tuma NB, Hannan MT (1978) Approaches to the censoring problem in analysis of event histories. In: Schuessler KF (ed) Sociological Methodology. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Wiltbank R, Dew N, Read S, Sarasvathy SD (2006) What to do next? The case for non-predictive strategy. Strategic Manage J 27(10):981–998

Yildiz HE, Morgulis-Yakushev S, Holm U, Eriksson M (2021) Directionality matters: board interlocks and firm internationalization. Global Strategy J:1–21

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the contributors to the Strategic Management Society’s 2022 Special Conference on “Governing Knowledge and Imagination in the Digital Era” at SDA Bocconi in Milan for insightful and clarifying comments. The authors are also thankful for an efficient review process that assisted us in clarifying and sharping the manuscript even further.

Funding

Open access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bjørnåli, E., Erikson, T. & Aspelund, A. The role of board leadership in deliberating international entry. J Int Entrep (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-024-00352-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-024-00352-x