Abstract

Academic research is increasingly emphasizing the critical role of business models (BMs) and business model innovation (BMI) in the international entrepreneurship (IE) domain, yet empirical studies on the topic are quite limited. This study demo0nstrates the role of BMI and entrepreneurial orientation (EO) in the internationalization of small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Specifically, we explored the mediating role of BMI in the relationship between EO and international performance among internationalizing SMEs. Drawing on a cross-industrial sample of 95 international Finnish SMEs, we empirically test the hypothesized relationships by developing a confirmatory factor analysis measurement model with subsequent application of ordinary least squares multiple regression. The results suggest that BMI positively and significantly mediates the relationship between EO and international performance. In addition, EO has a positive and significant effect on SMEs’ BMI. Thus, the findings of the study imply that both BMI and EO are important drivers of international performance for internationalizing SMEs. The study contributes to the IE literature by illustrating the dynamics of BMI and providing evidence of the linkages between strategic orientations and BMI in the international performance of SMEs.

Résumé

La investigación académica enfatiza cada vez más el carácter crítico del modelos de negocio y la innovación de modelos de negocio en el ámbito del emprendimiento internacional, sin embargo los estudios empíricos acerca del tema son bastante limitados. Este estudio demuestra el papel que juega la innovación de los modelos de negocio y la orientación emprendedora en la internacionalización de las pequeñas y medianas empresas. Específicamente, exploramos el carácter mediador de la innovación de los modelos de negocio en las relaciones entre la orientación emprendedora y el desempeño internacional de las PYMEs que se internacionalizan. En base a una muestra interindustrial de 95 PYMES finlandesas internacionales, se contrastan empíricamente las hipótesis mediante el desarrollo de un modelo de medición de análisis factorial confirmatorio con la posterior aplicación de regresión múltiple de mínimos cuadrados ordinarios. Los resultados muestran que la innovación de los modelos de negocio media de manera positiva y significativa la relación entre la orientación emprendedora y el desempeño internacional. Asimismo, la orientación emprendedora tiene un efecto positivo y significativo en la innovación del modelo de negocio de las PYMES. Así pues, los resultados del estudio implican que tanto la innovación de los modelos de negocio como la orientación empresarial son importantes impulsores del desempeño internacional en la internacionalización de las PYMES. El estudio contribuye a la literatura sobre emprendimiento internacional ilustrando la dinámica de la innovación de modelos de negocio y aportando evidencia sobre los vínculos existentes entre las orientaciones estratégicas y la innovación de los modelos de negocio en el desempeño internacional de las pequeñas y medianas empresas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Summary highlights

Contributions: The study contributes to the emerging discussion on the dynamics of business models, business model innovation (BMI), and international performance in international entrepreneurship and strategic orientation literature. It does so by jointly analyzing the effect and linkages between BMI, entrepreneurial orientation (EO), and international performance of internationalizing SMEs. Practical and managerial implications are also provided as a result.

Purpose: There are limited studies examining the combined effected of EO and BMI on international performance in IE research. We explore internationalizing SMEs, by examining BMI as a mediating variable in the EO–international performance relationship. Thus, by linking EO and international performance through the lens of BMI, we elucidate the role of BMI in SME internationalization as well as strategic orientations in the IE domain. The study responds to the question: What effect do BMI and EO have in the international performance of SMEs?

Data: Data were collected from a cross-industrial sample of SMEs in Finland through a structured online survey instrument based on a 7-point Likert scale. A total of 95 internationalizing SMEs comprised the final sample used in the analysis.

Finding/Results: The results demonstrate that EO has a positive and significant effect on BMI, with BMI also being positively and significantly related to the international performance of internationalizing SMEs. The results show that BMI mediates the relationship between EO and international performance. This implies that SMEs that innovate their BMs in response to the unfamiliar, dynamic, and uncertain international market conditions are able to enhance their international performance. The model suggests that the direct relationship between EO and international performance is positive but non-significant.

Theoretical implications and recommendations: The study links together the literature on business models and strategic orientations in illustrating international entrepreneurial behavior. More specifically, it indicates that internationalizing SMEs modify their BMs to satisfy the international market contexts and requirements. Therefore, having the ability to make modifications to the business model and possessing entrepreneurial mindsets allows SMEs to thrive and perform better in foreign markets. By examining EO and the BMI activities, that influence systematic changes in a firm’s core processes, we can gain more insights on SME business models and their implications to international performance.

Practical implications and recommendations: The study highlights that a firm’s ardent approach to innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking fosters the proper management of SME internationalization activities especially in an uncertain and competitive market environment. Thus, an entrepreneurial mindset and engagement in BMI are paramount for SMEs to remain competitive and to satisfy international market requirements. BMI is also considered a valuable ad hoc approach for SMEs especially for supporting internationalization strategies and augmenting for resource and capability constraints.

Limitations and future research: The single-country context and cross-sectional nature of the data used in this study may limit generalizability across contexts. Multi-country data would provide an opportunity for more variation, and future research should analyze specific industry sectors in multiple country contexts to develop the range of within-industry and contextual generalizations. Future studies could consider in-depth qualitative inquiry to gain more insights into business model changes and the mechanisms through which they affect international performance. In the same vein, further research will also benefit from clarifying the inconsistencies that exist in both EO and BMI measurement scales and constructs, thereby improving the robustness of IE research. Thus, it will be fruitful to conduct more studies that explore and foster theoretical grounding in the synergies between BMI dynamics and other strategic orientations variables as this will benefit the emerging field of BM and BMI and push research on entrepreneurial firms forward.

Introduction

International entrepreneurship (IE) research is increasingly reflecting on the strategic issues and challenges that entrepreneurial firms face as they recognize and seize opportunities in foreign markets (Shane and Venkataraman 2000; Zahra et al. 2005). Similarly, in corporate practice, small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) strive to gain a foothold in markets across national borders, in a bid to remain profitable and grow (Schneider and Spieth 2013). They do so by modifying their products, services, and BMs to satisfy the requirements of these markets (Nummela et al. 2004; Onetti et al. 2012; Child et al. 2017). SMEs, therefore, deliberately carve out strategies to establish continuous and ongoing value to prosper (Aspara et al. 2010). This study explores the relationship between business model innovation (BMI) and entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and the implications of BMI and EO for the international performance of SMEs. Although prior studies on this topic have investigated EO and BMI separately or examined only their direct effects (Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Wiklund and Shepherd 2005; Zott and Amit 2008; Aspara et al. 2010), studies on the combined effect of BMI and EO on international performance outcomes remain scarce. Indeed, there is a limited extant IE literature examining the combined role of strategic orientations and firm activities such as BMI, in the SME internationalization process (See Schneider and Spieth 2013; Hagen et al. 2017; Acosta et al. 2018). More so, there are few studies which explore the response of entrepreneurial SMEs—in terms of reconfiguring their value proposition, appropriation, and capture mechanisms, and how these affect their international performance (Knight and Cavusgil 2005; Aspara et al. 2010; Jantunen et al. 2005; Coviello 2015; Foss and Saebi 2017; Acosta et al. 2018). Thus, examining the dynamics of business model activities and the role of EO in internationalizing enterprises are vital (Aspara et al. 2010; Jantunen et al. 2005; Foss and Saebi 2017, 2018). This study was aimed at answering the research question: What effect do BMI and EO have in the international performance of SMEs?

In exploring IE, EO is relevant (Miller 1983; Lumpkin and Dess 1996, 2001) because the phenomenon explores a combination of entrepreneurial activities such as opportunity seeking and exploitation, innovation, proactiveness, and risk-seeking behavior of entrepreneurs across national borders (McDougall and Oviatt 2000; Zucchella et al. 2018). Thus, studies focusing on the influence of EO on internationalization activities can be valuable for understanding the peculiarities of SME internationalization in general (Laufs and Schwens 2014; Wiklund and Shepherd 2005; Jantunen et al. 2005; Acosta et al. 2018). Similarly, investigating entrepreneurial actions and the effects of their internationalization activities in foreign markets alongside other variables, such as organizational changes, BMI and performance would be valuable towards advancing IE research (Jantunen et al. 2005; Zucchella et al. 2018). Business model, and IE research, in general, would achieve milestones by including other strategic orientation constructs, such as EO (Aspara et al. 2010; Jantunen et al. 2005; Foss and Saebi 2017, 2018).

In this study, we considered BMI as a lens for viewing internationalizing SME activities (Foss and Saebi 2017, 2018; Acosta et al. 2018). Prior studies on the emerging concept of BMs drew our attention to the theoretical importance of including the strategic angle of the dynamics of BMs and SMEs’ international activities (Aspara et al. 2010; Wirtz et al. 2016; Child et al. 2017; Foss and Saebi 2017, 2018). Some studies attest that the key activities defining entrepreneurial firms and actions are closely associated with EO, BMI, and improved firm performance (Hamel 2000; Wiklund and Shepherd 2005; Wang 2008; Chesbrough 2010; Zott et al. 2011; Clauss 2017; Foss and Saebi 2017). However, due to ambiguities in the definition and conceptualization of BMs and BMI, the concepts have not been extensively researched (Mitchell et al. 2002; Morris et al. 2005; Malmström et al. 2015; Clauss 2017; Foss and Saebi 2017). Moreover, researchers have highlighted the need for more SME-focused empirical studies on the effects of EO and the international performance implications of firms with an emphasis on BMI (Aspara et al. 2010; Acosta et al. 2018).

As earlier elucidated, the concept of BMI as a mediating variable in the EO–international performance relationship has not been extensively explored in the IE literature (Aspara et al. 2010; Günzel and Holm 2013; Clauss 2017; Foss and Saebi 2017); hence, the study makes the following contributions. First, we introduce the concept of BMI to the relationship between EO and the international performance of internationalizing SMEs. We do so by exploring the dynamics of internationally operating entrepreneurial firms and the consequences of their BMI activities for their international performance, thereby contributing to IE domain, business model innovation, and strategic orientation literature, which is currently limited. Next, we build our argumentation on BMI and EO by examining the perspectives of EO and the dynamics of BMI, which influence some systematic changes in a firm’s core processes (Hwang and Christensen 2008; Cavalcante et al. 2011; Mezger 2014). Furthermore, although managerial practice and academic research have continually shown interest in the concepts of BMI and the entrepreneurial orientation of SMEs (Jantunen et al. 2005; Zucchella et al. 2018; Foss and Saebi 2017), few studies have examined these two streams of research together. Through the lens of BMI mediation, we contribute theoretically and provide managerial implications regarding the EO–international performance relationship.

The paper proceeds as follows. First, it outlines the literature from which we draw our arguments for the hypothesis development. Subsequently, it describes the research methodology and empirical data used to test the hypotheses, followed by the empirical analysis and discussion of the results. The paper concludes with a discussion of the key findings and contribution, the research limitations, and areas for future research.

Literature and hypothesis development

Business model innovation and international performance

As most businesses constantly face market uncertainties, it is crucial that they make intermittent changes, reinvent their business processes, and devise new ways and opportunities to grow and remain profitable (Covin and Slevin 1989; Wiklund and Shepherd 2003, 2005; Amit and Zott 2012; Clauss 2017). IE studies have noted that varying transitions and changes in today’s international business environment largely influence BM lifecycles (Hamel 2000; Cavalcante et al. 2011). Thus, exploring BMs and BMI provide an avenue to study change because they accommodate the flexibility required for firms to change, to meet the demands of a turbulent and uncertain business environment (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010; Cavalcante et al. 2011; Amit and Zott 2012; Hennart 2014). BMs are abstracted as a firm’s core repeated and standard processes, which are necessary for business performance (Cavalcante et al. 2011, Cavalcante 2014). Similarly, with a specific focus on large firms, Sosna et al. (2010) suggest that BMI is a key driver of success, citing examples such as Apple iTunes, Amazon, and Dell.

Pioneers of BM research have varying definitions of the concept. A business model is described as a logic for value creation, delivery, and capture (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010) or as a system of independent and interdependent activities that determine how a firm organizes the business with its stakeholders (Amit and Zott 2012). However, despite the extensive research conceptualizing and defining BMs, most studies abstract their definition of BMs merely at a conceptual (and less operational) level (Cavalcante et al. 2011; Foss and Saebi 2017, 2018). BMs are dynamic and unique, and they have been linked to different fields and theoretical perspectives, such as innovation (Hwang and Christensen 2008), strategic management (Miles et al. 2006; Johnson et al. 2008), high-tech SMEs (Mets 2009), and innovation management (Chesbrough 2010; Bucherer et al. 2012). Some studies link BMI to financial performance (Aspara et al. 2010) while other studies relate BMs and BMI to SME internationalization (Child et al. 2017). BMs are therefore an effective tool which can be used to increase a firms’ stability and robustness as they navigate their day-to-day activities (e.g., Zott and Amit 2008; Foss and Saebi 2017).

Pivotal studies suggest that BMI involves carrying out novel activities with important functions of creating, capturing, and delivering value as well as capitalizing on opportunities (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2010; Günzel and Holm 2013). According to Amit and Zott (2012), BMI allows managers to create and explore novel and existing market opportunities through three main activity systems: content innovation (the process of adding new activities to a system), structure innovation (linking activities in new ways), and governance innovation (aimed at changing the individuals in performing an activity). Largely, we surmise that BMI is a process of creating and developing new and unique value chain architectures, such as new products or services, market delivery patterns, and even organizational processes to improve firm performance (Chesbrough 2010). However, business models may transition a firm to a completely new competitive landscape or lead to radical modifications of the firms existing business processes (Nadler et al. 1997; Günzel and Holm 2013). Thus, management initiatives and capabilities are fundamental to a company’s competitive performance and differentiation strategy (Amit and Zott 2012). In other words, the capability to incorporate BMI is important for competitive performance and customer value delivery, as well for successful domestic and international operations (Morris 2009; Chesbrough 2010; Child et al. 2017).

Entrepreneurial actions and processes may trigger BM and process changes, which can have either positive or negative implications for redefining the BM, thereby affecting a firm’s international performance (Cavalcante et al. 2011). The literature on BMI illustrates that the main ideas and motives of BMI are twofold. First, BMI aims to fulfill the previously unmet needs of current customers by creating value for them. Second, BMI is motivated by the desire to attract a new customer base, resulting in the development of new value creation and capture mechanisms and activities (e.g., Markides 2006; Chesbrough 2007; Frankenberger et al. 2013). As such, entrepreneurially oriented SMEs have the propensity to create new value for both new and existing customers in international markets. However, the mechanisms put in place are integral because they foster the subsequent value creation and capture activities thereby leading to improved international performance (Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Zahra and Garvis 2000; Child et al. 2017). Furthermore, small firms tend to have the needed ability to effectively and flexibly create value and compete in new international market niches because of their rapid decision-making, structural simplicity, and entrepreneurial mindset (Dean et al. 1998). Aspara et al. (2010) concluded that small northern European firms that put more emphasis on BMI and less emphasis on BM replication showed a higher average value of profitable growth. Therefore, it could be argued that small entrepreneurial firms with a focus on BMI in international markets have higher average international performance rates.

A firm can improve its international performance by using turnaround strategies and initiating processes and activities that allow for developing BM change capabilities (Barker and Duhaime 1997; Bruton and Ahlstrom 2003; Amit and Zott 2012). Using the same logic, firms may improve their performance if they are willing to change, alter, or reinvent their business operations to devise suitable BMs; or develop their BMs by hypothesizing, testing, and revising them (Magretta 2002; Chesbrough 2010; McGrath 2010). Internationalizing SMEs undergo several transitions and changes in their BM lifecycles; therefore, the systematic changes that occur in a firm’s core processes affect a business model and BMI process (Cavalcante et al. 2011; Child et al. 2017). BMI is considered dynamic and requires specific managerial competencies to address change and innovation in an organization (Demil and Lecocq 2010). In line with strategic interpretations of BMs, a firm’s performance could be improved by aligning ideologies and strategies with changes in the business environment and reducing organizational inertia (Doz and Kosonen 2010). The conceptual work of Kim and Mauborgne (2005) supports that firms that creatively adopt BMI as a strategy tend to be more competitive and yield superior performance. Extending this reasoning to performance at the international level, we argue herein that internationalizing firms with a high emphasis on BMI exhibit improved competitive advantage and international growth. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

-

H1)

There is a positive relationship between BMI and SMEs’ international performance

Entrepreneurial orientation and business model innovation

Entrepreneurship and EO are different but related concepts that have been used interchangeably in some streams of literature (Lumpkin and Dess 1996, 2001). Lumpkin and Dess (2001) distinguished EO from entrepreneurship by referring to entrepreneurial activities as what individuals or businesses do, and EO as how the activities are conducted. EO refers to the practices, processes, and activities in which firms or entrepreneurial entities become involved in making decisions that lead to innovation and market entry decisions (Lumpkin and Dess 1996, 2001; Wang 2008). Hakala (2013) also describes EO as a strategic orientation that captures the entrepreneurial aspects of a firm’s strategies. Other studies describe EO as an independent posture that involves a firm’s commitment to innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking to develop and implement the firm’s strategies (Miller 1983; Covin and Lumpkin 2011; José Ruiz-Ortega et al. 2013). Proactiveness is a posture of preempting and acting on future needs of the firm (Wiklund and Shepherd 2005). Proactivity reflects the determination of a firm to pursue promising opportunities (Miller 1983). Thus, proactive firms are pace setters or first movers in the competitive market rather than followers (Lumpkin and Dess 1996). Innovativeness is closely linked with the firm’s pursuit of new opportunities, new ideas, and involvement in creative processes, which result in the production of new products, services, and technological processes (Lumpkin and Dess 1996). Risk-taking is the extent and willingness of managers to commit firm resources to activities or projects where the outcomes are unknown, and the cost of failure is high in uncertain market environments (Wiklund and Shepherd 2005; Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Miller 1983).

The issue of BM change is crucial in providing depth to BM and BMI discussion. This is because the objective of the BM change is aimed at identifying and exploring growth opportunities, with the aim of creating sustainable competitive advantages (Müller 2014). However, not all changes in an organization lead to BM changes (Müller 2014; Cavalcante et al. 2011). Rather, only the changes that influence the core standard repeated process of a BM constitutes a change in the business model (Cavalcante et al. 2011 pp.49). BM changes are initiated to fit business operations within specific prevailing business environments (Covin et al. 2006). Firms may correspondingly possess distinct capabilities for implementing and initiating BM changes in distinct market environments (Cavalcante et al. 2011; Cavalcante 2014). However, the extent of change or improvement relating to the development of BMs may vary (Müller 2014) and depends on the target market context and requirements (Child et al. 2017). More so, competitor firms tend to develop business methods or processes that threaten the survival of rival firms. For that reason, managers may respond to such threats by developing unique capabilities that would allow them to change or adjust key standard repeated processes, leading to BMI (e.g., customer loyalty programs, value-added services) as a competitive strategy (Morris et al. 2005; Miles et al. 2006; Johnson et al. 2008).

Achtenhagen et al. (2013) highlighted that strategic actions and capabilities of managers are essential to a BM especially in dynamic and competitive environments. Therefore, resource management, leadership styles, and organizational commitment are critical and can strengthen SME business models over time (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2010; Smith et al. 2010; Achtenhagen et al. 2013). An entrepreneurial mindset is a valuable enabler and driver for innovating BMs especially for internationalizing SMEs (Cavalcante et al. 2011; Amit and Zott 2012; Schneider and Spieth 2013; Child et al. 2017; Foss and Saebi 2017, 2018). For that reason, most entrepreneurial firms consider BMI as a better alternative and/or complementary to a new product or process innovation, especially in resource constraint and uncertain market environments (Amit and Zott 2012; Foss and Saebi 2018).

Furthermore, key organizational processes interact to generate revenue and keep the organization going. These processes are designed to keep the organization competitive in turbulent and dynamic environments, and they are affected by managerial approaches and decisions (Cavalcante et al. 2011; Cavalcante 2014). BMI could be considered a part of a firm’s corporate culture and/or capability (Tellis et al. 2009), with the view that the more innovative a firm is, the better its international performance will be (Aspara et al. 2010; Child et al. 2017). Alternatively, placing emphasis on BMI could be considered a firm’s continuous second-order strategic choice, subject to the choice of preserving or exploiting the firm’s existing resources and procedures versus exploring new ones (Tollin 2008), to provide a clear demarcation between innovativeness in EO and innovation in BMI perspective. We adopted the viewpoint that allows us to consider BMI as a continuous strategic orientation and the conscious renewing of a firm’s core business logic and processes, as opposed to limiting the scope of a firm’s innovative activities to a single product, service, or innovation project (Aspara et al. 2010; Schneider and Spieth 2013).

As earlier highlighted, international entrepreneurs operate in ever-changing business environments. Business continuity and performance in such environments is determined by the entrepreneurs’ ability to interpret the activities of these dynamic environments and, subsequently, develop abilities and implement changes to navigate through turbulent times (Zott 2003; Zahra et al. 2005, 2006). The BM of a firm serves the interlinked purpose of providing stability for the development of the firm activities as well as the flexibility to accommodate changes (Müller 2014; Cavalcante et al. 2011). Lindgardt et al. (2009) suggest that adopting BMI is a valued approach that can be proactively adopted by managers to explore new ways to tackle competitive environments to prosper and grow. Therefore, the adjustment of a firm’s key processes, which foster growth, innovation activities, proactiveness, and the ability to make risky decisions, determines the extent of creating new and unique processes and are important drivers of BMI (Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Aspara et al. 2010; Cavalcante et al. 2011; Hakala 2011). If a manager is unable to identify appropriate change initiatives and/or decisions appropriate for exploiting valuable opportunities, poor performance can follow (Cavalcante et al. 2011).

For internationalizing SMEs, the introduction of new goods and services, as well as the utilization of opportunities, may require modifying the BM in line with target foreign market expectations (Vithessonthi and Thoumrungroje 2011; Child et al. 2017). Although some SME studies highlight that recognizing and utilization of market opportunity may not always lead to superior performance (Guo et al. 2017). An entrepreneur’s ability to change an existing BM or adopt a completely new BM to suit the foreign market is linked with positive international performance (Doz and Kosonen 2010; Onetti et al. 2012; Michea 2016; Child et al. 2017). Hence, the decisions of the manager are pivotal in dealing with changes that occur in the business model and a firm’s organizational processes (Covin and Slevin 1989; Wiklund and Shepherd 2005). Vithessonthi and Thoumrungroje (2011) also note that firms may occasionally benefit from being not first movers but followers, emphasizing the need to proceed with slow and infrequent BM changes—although according to the same study, engaging in rapid and dramatic BM changes could negatively influence the survival of firms. Amit and Zott (2012) argue that in the face of resource scarcity and uncertain future returns, managers need to adopt BMI as an alternative or complement to product and process innovations. This is because even minor BM changes can result in increased performance.

Studies from academics and practice highlight that firms may design and initiate activities and processes aimed at providing stability to their business in line with the changing international business environment (Zott 2003; Pohle and Chapman 2006; Cavalcante et al. 2011). Hennart (2014) argues that a firm’s ability to succeed in the international market is a result of the effectiveness of its BM. Thus, a firm’s ability to be proactive and develop its dynamic capabilities is stimulated by preparatory strategic adjustments, and change initiatives, which lead to BM change and allows the firm to stay ahead of their competition (Jantunen et al. 2005; Teece 2010, 2012). This is particularly true of firms grappling with high costs for research and development (R&D), human resources, product development, and technological innovation (Markides 2006; Jantunen 2005; Wirtz et al. 2016). Zhao et al. (2016) emphasize the need for firms across industries to be able to reconfigure the value offered to customers to reflect changes in technologies, institutions, infrastructure, and stakeholders. BMI is essential because an innovative and well-executed BM has the potential to outperform new technology or even a business idea (Chesbrough 2007). Therefore, to enhance products, services, and process innovation; achieve cost efficiency; promote organizational learning as well as timely execution of resource configurations, firms will benefit by complimenting BMI with their core processes and activities (Zott 2003; Chesbrough 2007).

Managers should also consider adopting a risk-taking attitude to recognize, explore, seize, and exploit both technological and market opportunities (Chesbrough 2007; Child et al. 2017; Guo et al. 2017). In other words, firms should make audacious decisions that lead to an improvement in firm processes, as well as capitalize on new opportunities, thereby enhancing the BMI capability of the firm. Therefore, in line with these perspectives, we posit that EO would foster managerial decisions that lead to BMI as well as the development of capabilities that ultimately lead to modifications in the core processes and activities of the firm’s value creation, delivery, and appropriation system. Thus, we hypothesize that:

-

H2)

There is a positive relationship between the EO of internationalizing SMEs and their BMI.

Entrepreneurial orientation and international performance

As noted above, EO is a willingness to be proactive towards market opportunity, competition, and the ability to be innovative, as well as the commitment to make risky business decisions under uncertainty to gain competitive advantage (Wiklund and Shepherd 2005). Rauch et al. (2009) suggest that EO drives better firm performance, and several other studies (e.g., Bhuian et al. 2005; Rauch et al. 2009; Hakala 2013) find that EO can foster the development of new opportunities, products, services, and business ideas. The positive relationship between EO and organizational performance is also well established (e.g., Acosta et al. 2018). In other words, EO supports the firm’s ability to continuously identify and generate new business opportunities with the aim of achieving a long-lasting competitive advantage (José Ruiz-Ortega et al. 2013; Wiklund and Shepherd 2003, 2005). In exploring the concept of EO and its link to SMEs’ international performance, we examined EO as a single construct by combining innovation, proactiveness, and risk-taking (Jantunen et al. 2005; Covin et al. 2006). Following Miller’s (1983) definition, entrepreneurially oriented firms are those engaged in product–market innovation by taking risks in their ventures and proactively utilizing product and market opportunities that are inherent in the business environment. This definition suggests that innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking are the core characteristics of entrepreneurial firms. Further studies extend the construct of EO to self-governance and competitive aggressiveness as dimensions of EO (Lumpkin and Dess 1996, 2001). The extension of the construct of EO illuminates that firms continually aim to outperform competitors and they do so to follow their vision and to be successful (Lumpkin and Dess 2001). The fundamental objective of EO is closely associated with business strategy (Zhao et al. 2016), organizational change (Wang 2008), and new venture creation. As such in competitive and unpredictable environments, managers who augment their strategies by including BMI and redesigning programs aimed at developing organizational capabilities and processes foster competitive advantage (Morris 2009).

Multiple studies support that EO improves performance (Wiklund and Shepherd 2005; Jantunen et al. 2005); however, a few studies emphasize that non-significant relationships exist between direct observations of EO and performance (Hart 1992; Smart and Conant 1994; Slater and Narver 2000). Empirical observations have viewed such non-significant results as a possible methodological lapse in the research design (Wiklund and Shepherd 2005). Other studies mention that the context specificity and characteristic complexity of the external environment and internal firm may affect the conceptualizations of the relationship between EO and performance outcomes (Covin and Slevin 1989, 1991; Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Wiklund and Shepherd 2005). Thus, the higher the EO, the higher the propensity for discovering and recognizing opportunity, differentiation, and competitive advantage (Wiklund and Shepherd 2005), leading to positive performance outcomes.

A firm’s performance can be either long or short term and international performance evaluations can be conducted on either an objective or subjective basis (Protcko and Dornberger 2014). Subjective methods include evaluating firms’ international performance relative to international expectations or the competitive environment, while objective measures involve international financial measurements, such as return on investment, return on equity, profit margins, sales, or other indicators from international business activities (Protcko and Dornberger 2014). International performance could also be measured using either financial (e.g., international sales growth, international market share growth, and international profitability) or non-financial measures and in a multi-dimensional context (Protcko and Dornberger (2014). Although various financial assessments can be adapted to examine performance, essentially, entrepreneurial activities are vital to performance and affect profitability and growth in the international market (Zahra and Garvis 2000; Jantunen et al. 2005).

Thus, this study supports that SMEs’ international performance is dependent on the capability to be innovative and creative and the ability to adapt to new developments, structures, and processes to have superior international performance in uncertain market environments (Zahra and George 2002; Jantunen et al. 2005; Bianchi et al. 2017) Therefore, in line with these views, we hypothesize that:

-

H3)

There is a positive relationship between the EO of internationalizing SMEs and their international performance.

The mediating effect of business model innovation on the entrepreneurial orientation–international performance relationship

The reason for introducing BMI as a mediating variable in the EO–international performance relationship arises from the allusion that as firms advance in operational processes, their BMs often undergo several modifications before they are put into practice. Therefore, changes made to the BM are based on entrepreneurial activities and decisions in response to dynamic business environments and international market requirement (Zahra and Garvis 2000; Cavalcante 2014; Cavalcante et al. 2011; Achtenhagen et al. 2013). Thus, the role and decisions of an entrepreneurial firm are central to the changes that occur in its BM (Achtenhagen et al. 2013). Empirical findings also highlight that the mediating effect between EO and performance can be based on factors that are internal or external to the firm (Lumpkin and Dess 1996), which may vary according to the environment and the firm’s access to resources. International performance in competitive and dynamic environments is also strengthened by effective decision-making, fostering innovation activities, creating new opportunities, and capturing new markets. (Covin and Slevin 1990, Covin et al. 2006; Hamel 2000; Amit and Zott 2012; Clauss 2017). These factors that strengthen international performance also form part of the firm’s value proposition and value capture mechanisms that define BMs (Amit and Zott 2012). Hence, a firm’s international performance is closely linked to entrepreneurial risk-taking, proactiveness, innovativeness, and organizational processes that constitute a change in a BM (Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Wiklund and Shepherd 2005; Cavalcante et al. 2011; Onetti et al. 2012). Internationalizing SMEs that prioritize both EO and BMI have a higher propensity for discovering and recognizing opportunity, differentiation, and sustainable competitive advantage (Wiklund and Shepherd 2005; Hennart 2014; Child et al. 2017).

Internationalizing SMEs undergo several transitions and changes in BM lifecycles to tackle competition and catch up with market trends (Lindgardt et al. 2009; Cavalcante et al. 2011; Child et al. 2017). BMI is adopted by SMEs for reformulation or creation of new strategies for sustained competitive advantage in foreign markets (Wirtz et al. 2016). Hence, the BM a firm adopts, is a consequence of the firm’s strategy (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2010). Although, scholars maintain that in the face of uncertainty, firm growth and positive performance is a function of deliberate managerial choices and the ability to effectively adapt the BM to market dynamics (Wiklund and Shepherd 2005; Doz and Kosonen 2010; Cavalcante et al. 2011; Achtenhagen et al. 2013). There is lack of clarity concerning the concept and measurement of BM and BMI, which may lead to inconsistencies and mixed results in evaluating BMI and performance relationships (Zott and Amit 2008; Schneider and Spieth 2013; Patzelt et al. 2008). As such, studies aimed at exploring and clarifying the role of BM and BMI are valuable towards advancing business model research (Clauss 2017; Foss and Saebi 2017).

Overall, using the logic of mediation enabled us conclude that BM changes are closely linked to EO and organizational processes that may influence SME international performance (Hamel 2000; Wang 2008). Thus, the firm’s choice of BM determines its international performance (Hennart 2014; Child et al. 2017). We surmise that although EO does not fully provide sufficient conditions and explanation on rapid SME internationalization, adopting the “right” BM fosters international expansion and success (Hennart 2014). BMI encourages managers to navigate dynamic environments, identify underutilized resources and capabilities for future value, and gain sustainable performance advantage (Amit and Zott 2012; Hennart 2014). Thus, the following hypothesis on the mediation between EO and international performance is posited.

-

H4)

BMI mediates the relationship between EO and SMEs’ international performance.

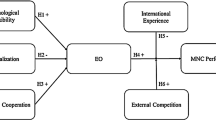

The conceptual model developed based on the literature review is represented in Fig. 1.

Methodology

Data collection and sample characteristics

The empirical data were collected via a structured online survey instrument from a cross-industrial sample of SMEs in Finland over a 6-month span. Specifically, we collected the data during May–September 2014 via a cross-sectional web-based survey instrument using Qualtrics online software. We compiled the initial list of firms to be contacted from the Amadeus online database and made sure to include a large variety of industry sectors to ensure that both manufacturing- and service-oriented companies were included in the sample. The industry sectors included in the initial draw were forest industry, chemical industry, metal industry, other manufacturing activities, mining and quarrying, energy supply, water supply, waste management, and construction industry. The resulting list had a total of 1130 firms, which we contacted via phone to solicit their participation in the survey. A total of 78 invalid firms (e.g., subsidiaries and other non-independent SME entities) were excluded from the final data collection. Ultimately, 311 firms declined to participate, with the most common reason being lack of time to do so. Furthermore, since 306 of the most relevant decision-makers in the contacted SMEs (most often the CEO) were not reached throughout the data collection process, they were excluded from the data collection process.

The survey scale items were developed and adapted from literature by a group of IE and entrepreneurship researchers who also translated the scale items from the Finnish to English. A professional English language editor service conducted back translation to ensure the accuracy of the translated items. We subsequently pre-tested the resulting survey with two SME managers from different fields to ensure its legibility to the target respondents. During the data collection process, we tracked the responses daily and sent two rounds of reminder emails to those who had not responded within 2 weeks of the initial contact. With the collection process concluded, we had a total of 148 responses at our disposal, for a 14% response rate (148/1052). Since such a response rate is acceptable in terms of rigor in entrepreneurship research (see Rutherford et al. 2017), we deemed the sample adequate for analysis. Of the final respondents, 64% (95) had international operations; thus, they constituted the final sample. The SMEs had, 58 employees on average, and an average age of 33 years, which had been operating internationally for an average of 20 years.

Measure development

Firms’ international performance may be either long or short term and international performance evaluations can be conducted on either an objective or subjective basis (Protcko and Dornberger 2014). Subjective methods include evaluating international performance relative to international expectations or the competitive environment, while objective measures involve international financial measurements, such as return on investment, return on equity, profit margins, sales, or other indicators from international business activities (Protcko and Dornberger 2014). Bianchi et al. (2017) suggest that the international performance of SMEs in international markets is heavily dependent on their ability to adapt to new developments, structures, and processes. This is in line with the findings of Protcko and Dornberger (2014) who suggest that international performance should be measured using either financial or non-financial measures and in a multi-dimensional context. Financial measures include international sales growth, international market share growth, and international profitability.

Therefore, we developed our dependent and independent variables through multi-item scales adopted from previous studies (e.g., Naman and Slevin 1993; Jantunen et al. 2005; Wiklund and Shepherd 2005). The dependent variable international performance was measured subjectively by asking respondents what they thought about their business activities on international platforms and markets (Jantunen et al. 2005; Naude et al. 2014; Bianchi et al. 2017). Using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7), respondents were asked to subjectively rate their firm’s international activities on such measures as return on investment in international markets, effect of internationalization on firm competence and capability development, profitability of international activities, and firm image building through internationalization. According to Wiklund and Shepherd (2005), most studies use growth to proxy business performance, which could take the form of profitability, sales growth, number of employees, or market share. Furthermore, we developed a subjective measure that was based on Dawes’ (1999) proposition that a firm’s subjective performance measures relative to its competitors are highly correlated with its objective performance measures, such as net profit margin, return on assets, return on investment, and return on earnings.

Overall, to measure EO, proactiveness, risk-taking, and innovativeness were taken as a single EO variable. Hence, the three EO dimensions were assessed as a single EO construct, in line with the measurements adopted by Naldi et al. (2007), Knight (1997), and Covin and Slevin (1989). These measures were also in line with other studies (see Jantunen et al.’s (2005), Wiklund and Shepherd’s (2005), and Naman and Slevin’s (1993)) which explore EO. On the other hand, due to the novelty of the concept of BMI, no existing scales at the time of data collection were considered suitable; hence, the measures for BMI used in this study were drawn from conceptual measures (see McGrath 2010 and Spieth et al. 2014). Similarly, other items for measuring BMI were developed following Markides’ (2006) BMI perspective. The items explored firm and managerial issues concerning the ability to reorganize operating processes in line with opportunities, rapid changes, and value proposition. The items exploring reconfiguration of operations of the firm were considered in developing the BMI construct, which we validated with recent and widely accepted measures from Clauss (2017).

Descriptive statistics and measure reliability

The average age of the SMEs was 33 years (SD = 24.9, range = 2 to 144 years). The number of employees ranged from 6 to 240, with an average of 58 (SD = 52.4, range = 6 to 240). Cronbach’s alpha values for individual variables ranged from 0.79 to 0.85. BMI varied from scores of 2 to the maximum score of 7, with an average score of 4.6. Since the study used subjective measures of both the manifest variables and their constructs, we needed to assess the validity of these measures. The use of multiple-item scales requires the computation of Cronbach’s coefficient alpha (α) values to estimate scale reliability (Cronbach 1951). It turned out that the scales used were reliable, as shown by a standardized Cronbach’s coefficient alpha value of 0.907. We also conducted measure reliability checks for the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model to assess the model’s internal consistency. These reliability checks included indicator reliability and common method variance. Harman’s single-factor test showed a one-factor variance of 35 (7%).

Common method bias

We recognized that applying Likert-scale items from extant literature and relying on the single most informed respondent in the SMEs (in most cases, the CEO) to fill out the survey on behalf of the company necessitated taking steps to mitigate the potential threat of common method bias influencing the results. Consequently, we followed the recommendations of Podsakoff et al. (2003) and Chang et al. (2010) and placed the scales and items used in the analysis in different parts of the larger survey and included several negatively worded items to observe any potential halo effects in the responses. We also considered that since we had hypothesized a non-trivial conceptual model including mediation effects, it was unlikely that the respondents would have been aware of the model relationships at a cognitive level to the point of them having a significant influence on their responses (cf. Chang et al. 2010, 179). In addition to these measures, during the analysis, we conducted Harman’s single-factor tests (7% single-factor variance) to uncover any potential common method bias in the empirical data. The results indicated that there were no single factors underlying the data. For these reasons, common method bias was not expected to have a significant effect on the results of the analysis.

Results and analysis

As suggested, by Anderson and Gerbing (1988) in assessing the hypothesized model, we followed a two-step approach. The first step involved generating a measurement model through CFA and analyzing its fit to the data. Subsequently, we developed an ordinary least squares (OLS), multiple regression model. The CFA results suggest that all manifest variables loaded significantly on their respective latent factors with factor loadings ranging from 0.61 to 0.92 and individual variable measures of sampling adequacy (MSA) ranging from 0.74 to 0.94. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics, reliabilities, and correlation matrix, and Table 2 shows the regression results. As the correlation matrix reveals, on the one hand, an SME’s age is negatively correlated with EO and BMI, but positively correlated with international performance; also, firm size is positively correlated with international performance, BMI, and EO.

The ordinary least squares (OLS) regression results show that the hypothesized relationship between BMI and international performance (H1) is positive and significant with a regression coefficient (β1) of 0.321 (t = 2.15, p = 0.035). A further assessment of the relationship between BMI and various aspects of international performance (as shown in Table 2—not hypothesized) shows that BMI is positively and significantly related to firm image building, competence, and capability development. A positive but non-significant relationship exists between BMI and profitability, as well as BMI and returns on investment. Hypothesis 2, on the relationship between EO and BMI, is supported by our model, with a regression coefficient (β2) of 0.561 (t = 6.82, p < 0.0001). The direct relationship between EO and international performance (H3) is not supported by our model as it is positive but non-significant (β3 = 0.213, t = 1.46, p < 0.149). Moreover, EO is positively related to the managers’ satisfaction with international performance (see Appendix, not hypothesized), but the relationship is non-significant. The results further support the hypothesis that BMI positively and significantly mediates the EO–international performance relationship. The mediation effect of BMI on the EO–international performance relationship (H4) was tested using the Sobel’s test, which shows a reduced value of the regression coefficient of the explanatory variable on the dependent variable upon adding the mediator variable. This then provides support for the hypothesis that BMI mediates the EO–international performance relationship.

Our control variables of firm age and size reveal positive but non-significant relationships via EO and BMI as well as via BMI and international performance.

Discussion and conclusion

The role of entrepreneurial firm characteristics, strategies, and activities as influencers and predictors of SME internationalization and international performance outcomes is increasingly taking center stage in business research (Knight and Cavusgil 2005; Child et al. 2017; Acosta et al. 2018). As previously noted, studies have adopted relevant strategic orientation variables, such as market orientation, learning orientation, and EO (Sinkula et al. 1997; Hakala 2011; Evers 2011; Martin and Javalgi 2016; Acosta et al. 2018) to explore performance. The aim of this study was to understand the role of BMI and EO in SMEs’ international performance. Our finding that EO positively but non-significantly predicts international performance contradicts the conclusions of other studies examining the EO–performance relationship. For example, Wang (2008) highlights that risk-taking behavior has a direct, positive, and significant impact on performance. We argue that even though EO is important for firms’ positive international performance, the positive effect could be mediated or moderated by some other mechanism, such as (in this case) SMEs’ capability to innovate their BMs, to be of significance.

Several studies have identified a positive relationship between EO and international performance and have noted that this relationship is enhanced by various factors, such as access to finance (Wiklund and Shepherd 2005), firm size, organizational culture (Rauch et al. 2009), and strategic organizational processes (Covin et al. 2006). The hypothesis that the relationship between BMI and international performance is positive and significant illuminates that internationalizing entrepreneurial firms with a high propensity to change their BM through BMI to address internal and external factors are more successful on international platforms. Thus, firms that are entrepreneurially oriented and have the capability to adjust their business activities and processes in response to dynamic business environments are likely to perform well internationally, as they are quick to respond to various changing business needs and requirements by incorporating them into their dominant logic. Our study is in line with Knight’s (2001) proposed causal chain, orientation–strategies–performance, and confirms that BMI is part of the strategic processes that are important for the EO–international performance relationship (Covin et al. 2006). BMI is also considered a continuous strategic orientation of a firm because (Siguaw et al. 2006); it becomes part of the firm’s corporate culture and capabilities (Tellis et al. 2009; Pohle and Chapman 2006). In the same vein, the more innovative a firm is in terms of its BM, the better (Tellis et al. 2009). This perspective is supported by our findings that positive and significant relationships exist between EO and BMI and between BMI and international performance.

Due to the dominance of SMEs in Europe and their drive for internationalization, strategic positioning and BMI capabilities are becoming increasingly critical (Salavou and Avlonitis 2008). Literature suggests that positive outcomes from seizing and utilizing opportunities can lead to an increase in firm performance (Jantunen et al. 2005). Lumpkin and Dess (2001) state that firms that are proactive in the early stages of the industrial lifecycle are high performers, while competitively aggressive and mature firms perform much better than their counterparts and competitors. Thus, analyzing how SMEs adapt to changing business landscapes is of paramount importance, as BMI capability is a rare, unique, and non-imitable source of competitive advantage, on which internationalizing entrepreneurial firms can leverage with positive international performance spillover effects (Lu et al. 2010). This study complements other studies (e.g., Jantunen et al. 2005; Bianchi et al. 2017) by empirically contributing to the IE and strategy research through illuminating the relationships between EO, BMI capabilities, and international performance.

Through this study, we established that EO positively and significantly affects BMI. Congruent with this finding, Hamel (2000) notes the important links between different EO dimensions and organizational strategic processes. Davis et al. (2010) highlighted that proactive, innovative, and risk-taking firms have the potential to thrive in uncertain and highly competitive market environments. We also identified that the positive effect of being proactive, innovative, and risk-taker on SME international performance is enhanced by the firm’s ability to innovate their BMs and aim to satisfy dynamic international market requirements. Thus, we surmise that positive proactiveness increases the firms’ ability to manage, identify, and efficiently utilize opportunities well ahead of competitors. Likewise, innovation fosters the development of new ideas, products, and services, and risk-taking allows for executing and implementing required changes to the BM and other firm processes, especially in uncertain and ever-changing business environments (Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Jantunen et al. 2005; Cavalcante 2014).

According to Schneider and Spieth (2013), BMI requires timely and effective identification and anticipation of dynamic changes in the environment. Extant studies also support that to be profitable and grow, internationalizing firms are confronted with the challenge of effectively managing various reconfiguration and innovation activities, and these activities would be better understood by exploring such firms and the initiative to innovate the existing BMs especially in competitive environments (Zahra and Garvis 2000; Jantunen et al. 2005; Aspara et al. 2010). Hence, the inclusion of BMI exemplifies that EO is a significant BMI enabler because it allows managers to strategically anticipate and handle volatile and competitive markets (Schneider and Spieth 2013). Our findings reinforce studies that suggest that managers who are more strategically oriented and agile are more capable of innovating their BMs (Davis et al. 2010; Doz and Kosonen 2010; Cavalcante et al. 2011; Schneider and Spieth 2013 Clauss 2017). Thus, SMEs that have the strategic perceptions and sensitivity to renew BMs are more likely to thrive in the international market than SMEs that do not consider BM modifications (Wiklund and Shepherd 2005; Davis et al. 2010; Doz and Kosonen 2010; Hennart 2014). Jantunen et al. (2010) illuminate that to continually satisfy the requirements of dynamic market environments and achieve sustainable competitive advantage, a firm should be able to reconfigure its processes and recognize the need for BM modifications as well as their consequences.

More so, in line with studies on SME internationalization (Edmondson et al. 2001; Jantunen et al. 2005), we agree that the requirements, criteria, and conditions for conducting business across various national frontiers, such as culture, export channels, and competitive and institutional conditions, may vary. Therefore, the BM adopted for (an) international market(s) may not be applicable to the domestic market (Landau et al. 2016; Child et al. 2017). Firms should thus modify their BMs to satisfy and specifically fit the international target market contexts and requirements (Onetti et al. 2012; Landau et al. 2016; Child et al. 2017). It is also important for SMEs to have the capabilities required to modify their core processes through BMI to be successful and influence positive outcomes (Aspara et al. 2010; Jantunen 2005; Cavalcante 2014; Wirtz et al. 2016; Child et al. 2017). An organization that is actively innovating and audacious in implementing and coordinating novel strategies have superior performance in both the domestic and foreign market (Lumpkin and Dess 2001; Jantunen et al. 2005; Jantunen 2005).

Although different variables have been explored in empirical research as determinants of international performance (Leonidou et al. 2002; Wiklund and Shepherd 2005; Jantunen et al. 2005; Acosta et al. 2018), having the capabilities to implement value reconfiguration activities—in this context, making modifications only to the BM—might not be enough to guarantee the international success of SMEs (Zahra and Garvis 2000; Jantunen et al. 2005; Foss and Saebi 2018). Rather, SMEs that possess formidable EO with strategic regeneration approach to BM changes and international organizational capabilities can thrive in foreign markets (Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Jantunen et al. 2005; Foss and Saebi 2018). In other words, strategic orientation can be further explored by integrating BM change on the nexus between EO and international performance. We also note that the actions and strategies of the entrepreneurial firm are critical and influential to changes that occur in its BM (Doz and Kosonen 2010; Cavalcante et al. 2011). Therefore, we surmise performance can be improved by encouraging entrepreneurial firms to develop their ability to explore, analyze, and interpret the business environment, and consequently, initiate processes and activities that foster BMI and propagate competitive advantage.

Contribution

Prior studies examining the direct link between EO and international performance have been critiqued as inadequate and short of theoretical insights for understanding the performance implications of EO (Hart 1992; Smart and Conant 1994; Wang 2008; Linton and Kask 2016). Proponents of entrepreneurship research encourage further exploration of EO and performance by including mediating elements (Lumpkin and Dess 2001; Wiklund and Shepherd 2005; Li et al. 2009). This study contributes by examining the link between EO and international performance through the mediating role of BMI. We explored whether the emphasis on BMI by entrepreneurially oriented internationalizing SMEs would have a positive effect on their international performance. Previous studies fell short of recognizing that the aspect of SME internationalization research and strategy could be further examined by including BM and BMI (Child et al. 2017; Foss and Saebi 2017, 2018). Thus, emerging literature on IE and BMs highlights the need to expand and integrate these research domains to provide a more holistic view of small firm activities in ever-changing international business environments (Catherine and Wang 2008; Teece 2010; Sainio et al. 2011; Zott et al. 2011; Onetti et al. 2012; Child et al. 2017).

Furthermore, recent studies note that theoretical contributions to the advancement of BM and BMI research should explore the role of BMI as a mediating variable in other useful research streams (Foss and Saebi 2017, 2018). Through this study, we have managed to explore and synthesize the roles of entrepreneurial firms’ BMs and BMI by examining the strategic activities of SME managers during internationalization activities and processes (Cavalcante et al. 2011; Clauss 2017; Foss and Saebi 2017). We surmise that BMI is based on a firm’s continuous innovation activities and continuous strategic orientation process (Aspara et al. 2010). Exploring BMI activities of SMEs provide more insights on the benefit of innovative changes that occur in the BM as well as the costs and risks to the firm in internationalization activities (Aspara et al. 2010; Child et al. 2017).

Studies illuminate that a gap exists and encourages more studies that explore international performance implications and combining BMI with various strategic orientations constructs (Acosta et al. 2018; Foss and Saebi 2017, 2018). This study contributes to the emerging research on BM changes as well as ongoing research on SME internationalization and strategic orientations. By combining BMI constructs and EO, the study produced novel insights on SME internationalization. Moreover, exploring BMI provides deeper insights and reasoning into a firm’s internal changes aimed at satisfying and addressing customer segments and needs, and the production, distribution, and delivery method of both existing and novel products and services (Markides 2006; Aspara et al. 2010). In the same vein, although researchers have called for further examination of the EO of internationalizing SMEs and their strategic influence on international performance, very few studies have specifically attempted to extend the focus by exploring the effect of BMI (Jantunen et al. 2005; Child et al. 2017; Foss and Saebi 2017, 2018). Our findings support that firms possessing unique strategies and EO foster profitability and revenue growth in international market frontiers (Zahra and Garvis 2000; Nummela et al. 2004; Jantunen et al. 2005).

Overall, the study contributes to the literature by clarifying the role of strategic orientations in the internationalization of SMEs in general. Through this study, we extend the relationship between the strategic orientation and international performance. Thereby, supporting studies which suggest that the relevance of mediating variables on the relationship between EO and international performance will concurrently move the BMI and EO research forward (Lumpkin and Dess 2001; Wiklund and Shepherd 2005; Li et al. 2009; Foss and Saebi 2018). Second, we examined BMI as a key success factor for SMEs’ internationalization activities (Sosna et al. 2010; Anwar and Ali Shah 2018) as well as the international performance implications of BMI (Aspara et al. 2010; Amit and Zott 2012). To our knowledge, neither of these notions was empirically confirmed previously; rather, they were only partly alluded to in earlier conceptual works. The theoretical contribution in advancing knowledge of BMs and BMI also derives from the finding that BMI can mediate relationships between orientations and performance outcomes in the international market context. Through this study, we sought to capture the role of BMs and BMI by exploring the strategic activities of SME managers (Cavalcante et al. 2011; Clauss 2017; Foss and Saebi 2017) and applying EO dimensions and BMI as mediators to evaluate their international performance. In the same vein, as Wiklund and Shepherd (2005) suggest, we also contribute to the evolving IE research by including BMI as a mediating variable to assess EO on SME performance. Lastly, we provide evidence of the linkages between the strategic orientations of EO and BMs in SME internationalization.

Finally, through this study, we identified that entrepreneurial firms that are strategically oriented and agile in dynamic business environments are more capable of innovating their BMs (Davis et al. 2010; Doz and Kosonen 2010; Cavalcante et al. 2011; Clauss 2017) and have positive performance outcomes. A firm’s EO is a valuable enabler and driver of BMI (Lumpkin and Dess 1996). As such, managers exhibiting EO and the necessary awareness to renew their BMs foster strategic perceptions and sensitivity to improving their BMs (Zahra and Garvis 2000; Wiklund and Shepherd 2005; Davis et al. 2010; Doz and Kosonen 2010). Amit and Zott (2012) highlight that firms usually find it costly to innovate their products and processes in the face of high upfront investment costs with uncertain future returns and high market competition. This is so especially for internationalizing SMEs due to the competitive, dynamic, and uncertain international market environment (Zahra and Garvis 2000). Moreover, due to high costs of firm activities (e.g., investment in product and process innovation, R&D, and acquisition of specialized resources and equipment) SMEs facing critical resource constraints may opt for BMI as an alternative and/or complement to product and process innovation. In other words, competitive pressures tend to make SMEs innovate their BMs and evidence from empirical studies shows that firms that prioritize BMI have the advantage to grow their operating margins rapidly (Amit and Zott 2012).

Managerial implications

The results of this study yield potential implications for management and policy in practice. First, they can help managers of internationalization-seeking enterprises by pointing out the necessity of being willing to modify the firm’s BM to internationalize successfully. We consider this implication a comforting one from the managerial point of view because it suggests that a company’s BM need not be perfectly globally scalable from the beginning; instead, it can—and should—be revised according to the identified international market opportunities. BMI can entail reconsidering the value proposition of the enterprise to its customers, being quick to reorganize operational processes as necessary and being willing to consider changes in pricing. The results of this study suggest that an enterprise that is willing to engage in these activities can reap benefits through more extensive and satisfying international expansion. Adopting BMI offers companies suitable and alternative avenues to thrive and overcome competition in international market environments (Lindgardt et al. 2009; Child et al. 2017).

Second, the results emphasize the necessity of entrepreneurially oriented (i.e., risk-taking, proactive, and innovative) behavior for not only entrepreneurial internationalization specifically but also for BM development in general. Hence, it seems that by fostering an entrepreneurial culture within an SME, managers can reap benefits both in being able to expand their enterprise more extensively to foreign markets and for helping the organization become more agile and responsive to customer needs in general. Since successful value creation and capture is highly interlinked with BM development, this further highlights the role of EO in successful entrepreneurship both at home and abroad. Finally, for policymakers, the results highlight the importance of supporting, primarily, growth enterprises—that is, those SMEs that are willing to take the financial and strategic risks that international expansion entails. The study also portrays that entrepreneurially oriented companies not only being able to reach markets abroad but also, just as importantly, of being the kind of agile enterprises that the twenty-first century economy with its dynamic nature increasingly requires.

In sum, as firms identify and exploit opportunities outside their country borders, acquiring and organizing resources becomes essential for catering to upfront investment (e.g., R&D, purchasing new equipment, producing new goods and services) as well as for enhancing international performance. Thus, managers can tackle resource or capability constraints during their internationalization process by engaging in BMI to satisfy international market requirements and cope with uncertain and competitive international markets. The result shows that firms across various industrial sectors tend to carry out BMI to cope with competition and market uncertainty and remain profitable in the international market. The study supports previous propositions that BMI could act as a complement or alternative to product and process innovation, with positive international performance effects. Therefore, in the absence of sufficient resources, internationalizing entrepreneurial SMEs should consider developing both their entrepreneurial mindset and BMI to enhance their competitiveness, growth, and profitability in international markets.

Limitations and further research

Our study has some limitations, which also present potential areas for future research. In this study, we conceptualized EO as a single construct with three dimensions of innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking because it allowed us to examine attributes, characteristics of the firm, and concurrently the influence of BMI on international performance. However, by no means would we claim the mediating role of BMI should be restricted to EO only. In fact, exploring whether a similar effect for other variables such as market orientation or learning orientation could further determine the generalizability of the results across the spectrum of strategic orientations in general (Hakala 2011; Acosta et al. 2018; Guo et al. 2017). Further research could consider exploring the role of BM changes with other entrepreneurial attributes and strategic perspectives and orientations such as learning orientation and market orientation to explore SME international activities. Studies exploring different characteristics of BM modifications and their implications on internationalization are valuable to the field of IE research. More studies could consider exploring how other factors, activities, and actors influence foreign market expansion (Hennart 2014; Child et al. 2017).

Literature suggests that variations exist in entrepreneurial orientation dimensions, with some studies (Miller 1983) suggesting three dimensions, while other studies suggest five (Lumpkin and Dess 1996). These inconsistencies might limit our research findings as we focused on three dimensions as suggested by Miller (1983). Additionally, we measured international performance subjectively, but in doing so, we sought to take preventive measures against any potential common method bias, as suggested by Podsakoff et al. (2003) and Chang et al. (2010), and by exploring aspects of international performance as individual variables. Moreover, because we used cross-sectional data and in a single-country context, thus we do not delve into causal interpretation among the key constructs explored. We suggest that future research consider analyzing industry-specific firms in single or multiple country contexts to provide further evidence for the generalizability of the results across different contexts. Finally, since the present study explored SMEs international performance implications from the point of view of EO and BMI, future research could extend to larger firms to get deeper insights into the research context and to further ascertain the generalizability of the results across firms of different sizes. Furthermore, we posit that in-depth qualitative inquiry on other drivers of business model changes as such as opportunity recognition, dynamic capabilities, decision-making logic, and the mechanisms through which they affect international performance (see Zott and Amit 2010; Foss and Saebi 2017; Guo et al. 2017) would yield richer data through which the BMI dynamics in international entrepreneurship could be studied. We confirmed that BMI is driven by an entrepreneurial orientation, managerial decisions, and the ability to implement change to capitalize on opportunities to gain competitive advantage (cf. Doz and Kosonen 2010; Michea 2016). Further research could also explore managerial activities, organizational activities, and other drivers that can influence BM changes in the internationalization of SMEs.

References

Achtenhagen L, Melin L, Naldi L (2013) Dynamics of business models–strategizing, critical capabilities and activities for sustained value creation. Long Range Plan 46(6):427–442

Acosta AS, Crespo ÁH, Agudo JC (2018) Effect of market orientation, network capability and entrepreneurial orientation on international performance of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Int Bus Rev 27:1128–1140

Amit R, Zott C (2012) Creating value through business model innovation. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 53(3):41–49

Anderson JC, Gerbing DW (1988) Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull 103:411–423

Anwar M, Ali Shah SZ (2018) Managerial Networking and Business Model Innovation: Empirical Study of New Ventures in an Emerging Economy. J Small Bus Entrepr pp 1-22.

Aspara J, Hietanen J, Tikkanen H (2010) Business model innovation vs replication: financial performance implications of strategic emphases. J Strateg Mark 18(1):39–56

Barker VL, Duhaime IM (1997) Strategic change in the turnaround process: theory and empirical evidence. Strateg Manag J 18(1):13–38

Bhuian SN, Menguc B, Bell SJ (2005) Just entrepreneurial enough: the moderating effect of entrepreneurship on the relationship between market orientation and performance. J Bus Res 58(1):9–17

Bianchi C, Charmaine G, Mathews S (2017) SME international performance in Latin America: the role of entrepreneurial and technological capabilities. J Small Bus Enterp Dev 24(1):176–195

Bruton G, Ahlstrom D (2003) An institutional view of China’s venture capital industry: explaining the differences between China and the West. J Bus Vent 18(2):233–259

Bucherer E, Eisert U, Gassman O (2012) Towards systematic business model innovation: lessons from product innovation management. Creat Innov Manag 21(2):183–198

Casadesus-Masanell R, Ricart JE (2010) From strategy to business models and onto tactics. Long Range Plan 43(2):195–215

Cavalcante SA (2014) Designing business model change. Int J Innov Manag 18(02):1–22

Cavalcante S, Kesting P, Ulhøi J (2011) Business model dynamics and innovation: (re)establishing the missing linkages. Manag Decis 49(8):1327–1342

Chang SJ, Van-Witteloostuijn A, Eden L (2010) From the editors: common method variance in international business research. J Int Bus Stud 41(2):178–184

Chesbrough H (2007) Business model innovation: it’s not just about technology anymore. Strateg Leadersh 35(6):12–17

Chesbrough H (2010) Business model innovation: opportunities and barriers. Long Range Plan 43:354–363

Child J, Hsieh L, Elbanna S, Karmowska J, Marinova S, Puthusserry P, Tsai T, Narooz R, Zhang Y (2017) SME international business models: the role of context and experience. J World Bus 52(5):664–679

Clauss T (2017) Measuring business model innovation: conceptualization, scale development, and proof of performance. R&D Manag 47(3):385–403

Coviello N (2015) Re-thinking research on born globals. J Int Bus Stud 46 (1):17–26

Covin JG, Slevin DP (1989) Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strateg Manag J 10(1):75–87

Covin JG, Slevin DP (1990) New venture strategic posture, structure, and performance: an industry life cycle analysis. J Bus Vent 5(2):123–135

Covin JG, Slevin DP (1991) A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behavior. Entrep Theory Pract 16(1):7–26

Covin JG, Green KM, Slevin D (2006) Strategic process effects on the entrepreneurial orientation-sales growth rate relationship. Entrep Theory Pract 30(1):57–81

Covin JG, Lumpkin GT (2011) Entrepreneurial Orientation Theory and Research: Reflections on a Needed Construct. Entrepr Theory Pract 35 (5):855–872

Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16:297–334

Davis JL, Bell RG, Payne T, Kreiser PM (2010) Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of Managerial Power. Amer J Bus 25 (2):41–54

Dawes J (1999) The relationship between subjective and objective company performance measures in market orientation research: further empirical evidence. Mark Bull–Dep of Mark Massey University 10:65–75

Dean TJ, Brown RL, Bamford CE (1998) Differences in large and small firm responses to environmental context: strategic implications from a comparative analysis of business formations. Strateg Manag J 19(8):709–728

Demil B, Lecocq X (2010) Business model evolution: in search of dynamic consistency. Long Range Plan 43(2–3):227–246

Doz YL, Kosonen M (2010) Embedding strategic agility: a leadership agenda for accelerating business model renewal. Long Range Plan 43(2–3):370–382

Edmondson AC, Bohmer RM, Pisano GP (2001) Disrupted routines: team learning and new technology implementation in hospitals. Admin Sci Quart 46(4):685–716