Abstract

This study looks at whether Kazakh and Russian wheat exporters leverage their dominant share of the wheat markets in the South Caucasus to exercise market power. We apply a three-stage estimation for systems of simultaneous equations and Zellner’s seemingly unrelated regression to analyze residual demand elasticity. The results of both estimations provide empirical evidence of Russian market power in the wheat markets of the South Caucasus but no evidence of a Kazakh oligopoly. Russian exporters possess greater market power in Armenia than in Georgia. Market power depends on the presence of competitors in the destination market. The results show that Kazakh exporters restrict the market powers of Russian exporters in the Azerbaijani wheat market, while Russian exporters constrain the market power of Kazakh exporters in the Azerbaijani and Georgian wheat markets. Ukrainian wheat exporters are able to intervene in the market powers of Russian exporters in Azerbaijan and Georgia, while they restrict Kazakh oligopoly in the Georgian market. Some export restrictions imposed by wheat exporting countries significantly affected competition in wheat importing countries. Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine and the blockade of Ukrainian ports on the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea are restricting wheat trade, severely damaging Ukraine’s competitiveness and export potential, and reducing food security in the South Caucasus, the Middle East, and North Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

At the beginning of the 2000s, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine (KRU) became wheat exporters in the global market, significantly affecting the shares of the world’s major wheat exporters (Gafarova et al. 2015). Due to their geographic locations and historical trade relationships, the countries of the South Caucasus—Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia—are important trade partners of KRU. Indeed, KRU possess significant market shares in these countries. Kazakhstan and Russia are the main wheat exporting countries to the South Caucasus and are therefore able to affect the wheat export prices to this region. We argue that by using their higher market shares Kazakh and Russian wheat exporters are able to exercise market power in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. We expect this effect to be strongest in Armenia, as Russia holds a leading position in Armenia’s wheat market. Due to Georgia’s diversified wheat import policy, we expect Kazakh and Russian exporters to have less market power there. Similarly, Kazakh and Russian wheat exporters may have weaker (or no) market power in the Azerbaijani wheat market, as the country diversifies its wheat imports and is able to meet part of its own demand for wheat through local production.

Most of the previous econometric studies analyzing the market behavior of wheat exporters in international markets for have been carried out for traditional major wheat exporting countries such as Australia, Canada, or the USA (cf. Carter et al., 1999; Yang and Lee 2001; Cho et al. 2002). Only a few studies have examined market power and price discrimination in international wheat markets for a new global player such as Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine. The latter include the studies by Pall et al. (2014) and Uhl et al. (2019), which applied the residual demand elasticity (RDE) approach to Russian wheat exports, and by Pall et al. (2013) and Uhl et al. (2016), which analyzed the Russian pricing behavior in international wheat trade using a pricing-to-market (PTM) approach. Only Gafarova et al. (2015) applied a PTM approach for the analysis of Kazakh, Russian, and Ukrainian wheat exporters.

The objectives and contributions of this study are threefold. First, there are a number of empirical studies that measure the extent of exporters’ market powers in international markets in the context of the RDE approach (see Table 5 in the Appendix). However, there are currently no published studies that measure the magnitude of Kazakh wheat exporters’ market powers in any destination country. To fill this research gap, this study uses a residual demand elasticity (RDE) approach to explore a range of hypotheses on the competitive nature of the Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Georgian wheat import markets. Second, most empirical studies that rely on a residual demand elasticity approach use a single equation model; only a few publications consider a multi-equation model. This study uses a multi-equation model (system of simultaneous equation) to measure the extent of the market power that Kazakh and Russian wheat exporters exercise in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. Third, over the sample period from 2004 to 2021, the Kazakh, Russian, and Ukrainian governments enforced export bans, export taxes, export quotas, export licenses, and memoranda of understanding (see Table 6 in the Appendix). This study looks at the impact of six policy instruments on competition and the market behavior of wheat exporters in the South Caucasus. The results of this study are particularly relevant for understanding the impact of the export restrictions related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which imposed a blockade on Ukrainian ports in the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea and its civilian merchant marine, and halted Ukrainian exports of wheat and other agricultural commodities and food products, such as maize and sunflower oil, from 24 February to 1 August 2022. To date, the Ukrainian wheat exports have been completely blocked in the Sea of Azov, and restricted rather than free in the Black Sea, with significant implications for global food security and nutrition.

The rest of the study is organized as follows. The next section provides background information about the region. This is followed by an overview of the relevant theoretical literature and empirical studies on residual demand elasticity. The modelling is outlined in Sect. 4. Section 5 presents a description of the data and summary statistics. The regression results are discussed in Sect. 6. The final section of the study summarizes the main findings, addresses policy implications, and discusses the directions and issues for future research.

2 Background Information About the Region

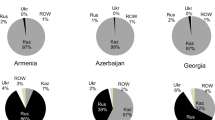

Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia are middle-income countries. Bread and bakery products are the main staple foods in the region, where they play an important role in meeting the population’s demand for protein and energy. In 2019, annual per capita consumption of wheat in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia was 131 kg, 244 kg, and 129 kg, respectively (ARMSTAT 2022a; AZSTAT 2022a; GEOSTAT 2022a). None of the South Caucasus countries is able to entirely meet its growing demand for wheat, and all three therefore have to import it, mainly from Russia and Kazakhstan. According to the statistics offices, the self-sufficiency rates for wheat in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia are 26%, 53%, and 15%, respectively (ARMSTAT 2022b; AZSTAT 2022a; GEOSTAT 2022a). Figures 1, 2, and 3 below depict the annual wheat export volumes of the main exporters to Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia and show how their market shares changed from 2004 to 2021. Both Kazakhstan and Russia have high market shares in Azerbaijan and Georgia, while Ukraine possesses only small shares there. In Armenia, only Russia is a leading wheat exporter.

In general, the export quantities coming from Kazakhstan and Russia are not stable, and the two countries’ market shares have been frequently disrupted by export restrictions. Kazakhstan imposed export restrictions on wheat from April 2008 to September 2008 (Kim 2010); Russia implemented a wheat export tax from 2007 to 2008 and completely banned wheat exports from 2010 to 2011; and Ukraine set export quotas in 2006–2008 and 2010–2011 (Djuric et al. 2015). A detailed list of export restrictions enforced by Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine is provided in Table 6 in the Appendix.

Figures 1, 2, and 3 show that Kazakh and Russian wheat export volumes to all three South Caucasus countries changed significantly over the study period. Because of its locational disadvantage, political instability, and poor infrastructure, Armenia is only able to meet its demand for wheat by importing almost exclusively from Russia. Azerbaijan buys the most wheat in the South Caucasus, importing twice as much as Georgia and almost five times more than Armenia. This is because Azerbaijan’s population (10.1 million) is three times greater than Armenia’s (3.0 million) and two times greater than Georgia’s (3.7 million) (ARMSTAT 2022b; AZSTAT 2022b; GEOSTAT 2022b). Figure 1 shows that Russia began to take a leading position in the Armenian wheat market from 2006, with a market share of almost 80% or more. Since 2015, Russia’s share of the Armenian wheat market has fluctuated between 95 and 100%. The market shares of the two competing countries, Kazakhstan and Ukraine, are relatively small. Therefore, Kazakhstan and Ukraine may not be strong competitors for Russia in this market. According to FAOSTAT (2022) Food Balances Database calculations, the Import Dependency Ratio (IDR) for wheat (share of wheat imports in domestic consumption) ranges from 43.3 to 67.0% in Armenia. This high import dependency ratio (IDR) and Russia’s high market share indicate that Armenia is heavily dependent on wheat from Russia.

Figure 2 shows that the market shares of Kazakhstan and Russia are relatively high in Azerbaijan and changed significantly from 2004 to 2013. Since 2014, Russia’s market share has increased from about 50% to almost 100%, and in 2021, the last year of the study, Russia alone supplied 100% of the Azerbaijani wheat market (cf. Figure 2). The IDR for wheat in Azerbaijan is significantly lower than in Armenia and ranges from 38.2 to 54.4%. Because Azerbaijan can partly meet its own demand for wheat through local production and there are two supplier countries, Kazakhstan and Russia, the Azerbaijani wheat market might be competitive.

In terms of market structure, the Georgian wheat market differs significantly from the Armenian wheat market but is almost identical to the Azerbaijani wheat market. Figure 3 shows that Russia’s market shares have always been relatively high without significant variation. From 2004 to 2013, Russia had to share the Georgian wheat market with Kazakhstan (predominantly) and with Ukraine (partly). However, since 2014, Russia has increased its share of the Georgian wheat market from about 85% to almost 100%, and in the last 2 years of the study, 2020 and 2021, Russia alone supplied 100% of the Georgian wheat market (cf. Figure 3).

The IDR for wheat in Georgia is significantly higher than in Armenia and Azerbaijan and ranges from 75.8 to 98.8%. Compared to the other two South Caucasus countries, Georgia enjoys the locational advantage of being closer to Russia and Ukraine, and mainly imports wheat from Russia. However, due to its limited ability to produce wheat, Georgia can only meet 15% of its own demand for wheat through local production.

Kazakhstan and Russia are the two dominant wheat exporting countries in the South Caucasus. This dominant position gives rise to the hypothesis that they may exercise market power. RDE analysis can be used to empirically test the competition and market behavior of these two competing countries and the extent of oligopolistic market power in wheat markets in the South Caucasus. While there is an almost similar duopoly structure in the Azerbaijani and Georgian markets and both Kazakh and Russian wheat exporters may have oligopolistic market power, Russia alone dominates the wheat import market in Armenia.

3 Review of Empirical Studies

Originally, the RDE approach was introduced by Baker and Bresnahan (1988) and later developed by Goldberg and Knetter (1999). The RDE approach not only makes it possible to identify the extent of market power but also explains it by the combinations of demand conditions, market conduct, and market structure. This approach represents the effects of export quantity, cost shifters, and demand shifters on export price by taking into account the reactions of competing countries (Glauben and Loy 2003). Instead of dealing with a structural demand system involving all firms in an industry, the RDE approach focuses only on the estimation of a single equation (Poosiripinyo and Reed 2005). Despite its advantages, few studies have applied the RDE approach to agricultural products markets (see Table 5 in the Appendix). Rather, most studies have focused on the analysis of market power in certain markets, like in beer markets (Baker and Bresnahan 1988; Goldberg and Knetter 1999; Glauben and Loy 2003) and meat export markets (Reed and Saghaian 2004; Poosiripinyo and Reed 2005; Felt et al. 2011; Xie and Zhang 2014).

The literature pertaining to the analysis of market power in grain markets remains quite limited. Very few studies have focused on investigating wheat markets in different countries (Carter et al. 1999; Yang and Lee 2001; Cho et al. 2002; Pall et al. 2014). However, with the exception of Pall et al. (2014), the majority of these publications have concentrated on analyzing the market power of traditional wheat exporters (Argentina, Australia, Canada, the European Union, and the USA). For instance, Carter et al. (1999) for 1970–1991 and Yang and Lee (2001) for 1993–1999 looked at whether Australia, Canada, and the USA have market powers in the Japanese and South Korean wheat markets, respectively. The authors found that the USA has significant market power in both wheat markets, whereas Australia and Canada have market power only in the South Korean wheat market. Cho et al. (2002) also examined the market power of the USA in the Japanese wheat market, together with five other destinations over the period 1973–1994. The results showed that the USA could exercise significant market power in the Korean, Malaysian, Philippine, and Singapore wheat markets but not in the Indonesian and Japanese markets.

Pall et al. (2014) examined the market power exercised by Russian wheat exporters in selected destinations using the generalized method of moments and instrumental variable Poisson pseudo maximum-likelihood estimators. The authors used quarterly data from 2002 to 2009 and demonstrated that Russian exporters are able to exercise market power in five out of eight destinations, including Azerbaijan and Georgia. Using novel firm-level datasets with weekly information on Russian wheat exports, Uhl et al. (2018) applied the residual demand elasticity method to analyze Russia’s pricing behavior in its two most important export markets: Egypt and Turkey. The estimation results of their study revealed that Russia behaves competitively in Egypt, while it exerts market power in Turkey, with an estimated mark-up of 13.5%. To capture Kazakh and Russian export restrictions, the authors also examined the Russian wheat export tax as an instrumental variable for Egypt and Turkey and the Kazakh export ban as an exogenous dummy variable.

The RDE approach has also been used to analyze non-agricultural products markets. A study by Yang and Lee (2001) examined market power in the aluminum industry of the USA, while another study by Silveira and Resende (2020) looked at whether Brazilian niobium exporters had market powers in the USA and the European Union. Although some studies used multi-equation models (system of simultaneous equation) to analyze the RDE approach (Baker and Bresnahan 1988; Goldberg and Knetter 1997, 1999; Cho et al. 2002; Reed and Saghaian 2004; Song et al. 2009; Chang and Inoue 2013), the majority of the related literature preferred the single-equation model.

4 Theoretical Background and Empirical Model Specifications

To measure the degree of market power in international markets, Goldberg and Knetter (1999) introduce a reduced form of the following equation:

where \(m\) and \(t\) denote importing market and time, respectively, \(K\) is the number of competitors in a specific market, \({{\varvec{\upalpha}}}^{\mathbf{^{\prime}}}\) and \({{\varvec{\upbeta}}}^{\mathbf{^{\prime}}}\) are vectors of parameters, and \({{\widehat{Q}}}_{mt}^{ex}\) is the instrumented quantity exported. Furthermore, export prices,\({P}_{mt}^{ex}\), and vector of demand shifters of \(m\) number of destinations, \({\mathbf{Z}}_{\mathbf{m}\mathbf{t}}\), are expressed in the destination country’s currency.

Cost shifters of \(K\) competitors,\({\mathbf{W}}_{\mathbf{m}\mathbf{t}}^{\mathbf{K}},\) can be divided into two parts: one that does not vary by destination and is expressed in the competing country’s currency (e.g., producer price), and the other that is destination-specific (e.g., exchange rate). Cost shifters comprise a destination-specific exchange rate and the competitors’ average producer price for wheat; both are expressed in the competing country’s currency. \({\varepsilon }_{mt},\) an error term, is independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.).

The main coefficient in Eq. (1) is \(\eta\), which is an inverse of RDE. In case \(\eta =0\), a market is perfectly competitive and the exporting country faces a perfectly elastic demand curve. Export price is affected not by a change in the quantity exported but by the costs of competitors, which means that the exporting country does not have any market power and is a price taker. However, in case \(\eta <0\), a market is imperfectly competitive and the exporting country is a price maker. Exporting country has market power and it increases as the absolute value of \(\eta\) gets larger.

Coefficients of cost shifters \(,{ \beta }^{^{\prime}},\) define whether competing countries’ products are a perfect or imperfect substitute for an exporting country’s product. In case \({\beta }^{^{\prime}}>0\), a competing country’s product is a perfect substitute for an exporting country’s product. Exporting country can increase its export price if the competing country’s costs rise. In this way, these two countries compete in an importing country and intervene in each other’s market powers. On the contrary, in case\({\beta }^{^{\prime}}<0\), a competing country’s product is an imperfect substitute for an exporting country’s product.

The empirical model specification is undertaken for each of the two major exporters—Russia and Kazakhstan—in the wheat markets of the South Caucasus. The model specification for Russian and Kazakh exports and the choice of cost shifters are based on the descriptive analysis presented in Sect. 2 and the market share calculation summarized in 1 for the sample period from 2004 to 2021.

Considering the almost monopoly market structure in the Armenian wheat market and similar duopoly market structure in the Azerbaijani and Georgian markets, it can be assumed that Russian wheat exporters compete with Kazakh and Ukrainian wheat exporters in the three destination markets—Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgian (cf. Table 1 and Figs. 1, 2, and 3).

The estimation model of the inverse residual demand curve defined by Eq. (2) has the form of a linear system of three or two simultaneous equations representing three destination markets for Russian wheat exports and two destination markets for Kazakh wheat exports, respectively:

The superscript \(N\) indexed by \(RU\) indicates the RDE model for Russian wheat exports and the superscript \(N\) indexed by \(KZ\) indicates the RDE model for Kazakh wheat exports, respectively. The terms \({\gamma }_{m}^{N}\), \({\eta }_{m}^{N}\), \({\alpha }_{m}^{N}\), \({\sigma }_{m}^{N}\), \({\delta }_{m}^{N}\), \({\beta }_{m}^{K}\),\({\varphi }_{m}^{K}\), \({\tau }_{m,t}^{N}\), and \({\vartheta }_{m,r}^{K}\) are parameters to be estimated simultaneously. The subscript \(m\) represents the specific destination markets of wheat exporters in the South Caucasus indexed by subscripts \(AM, AZ,\) and \(GE\) standing for Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, respectively. \({P}_{mt}^{N}\) and \({Q}_{mt}^{N}\) are the Russian or Kazakh wheat export price approximated by export unit value expressed in the importing country’s currency and \({Q}_{mt}^{N}\) is the Russian or Kazakh wheat export quantity expressed in metric tons. The gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, the consumer price index for food items (CPI), and a linear time trend \(\left(T\right)\) are used to capture any shifts in demand in each of the three destination countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia) over time \(t\).

The set of cost shifters is represented by a vector of exchange rates \(\left({e}_{mt}^{K}\right)\) and a vector of wheat producer prices \(\left({PPW}_{mt}^{K}\right)\) of exporting countries competing with Russian or Kazakh wheat exporters in each of the three destination markets. The superscript \(K\) stands for Russia’s and Kazakh competitors in each destination market indexed by the superscripts \(KZ\) for Kazakhstan and \(UA\) for Ukraine, and \(RU\) for Russia, respectively.

Goldberg and Knetter (1999) point out that demand shifters must take into account trade restrictions imposed by the destination markets and the resulting effects on trade volumes and prices. Because export restrictions on wheat exports were introduced by the Kazakh, Russian, and Ukrainian governments, it can further be assumed that export restrictions on wheat exports might have extraordinary effects on exporters’ behavior in the destination markets. \({ERD}_{mt}^{K}\) is a vector of dummy variables capturing trade restrictions on wheat exports imposed by the governments of all three competing countries—Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine—in the sample period from 2004 to 2021. Table 6 in the Appendix provides an overview of a wide range of trade restrictions on wheat exports, including export licenses, export bans, export transport subsidies, export taxes, export duties, export quotas, and memoranda of understanding (MoU) regulating grain export volumes.\({QRTD}_{mt}\) is a vector of dummy variables for the second, third, and fourth quarters to capture seasonality in the quarterly data series.

5 Data Samples and Sources

Two quarterly time series datasets were used for the econometric analysis of the RDE model for Russian and Kazakh wheat exports, which is represented by a system of simultaneous equations in Eq. (2). Table 7 in the Appendix provides a description of the model variables, their descriptive statistics, and data sources for the dataset of Russian wheat exports to Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. Table 8 in the Appendix provides a description of the model variables, their descriptive statistics and data sources for the dataset of Kazakh wheat exports to Azerbaijan and Georgia. Quarterly time series data for wheat export quantity and wheat export value were collected from the Global Trade Information Services (GTIS) database for the period from the first quarter of 2004 to the fourth quarter of 2021. GTIS provides wheat export data by disaggregated 6-digit Harmonized System (HS) codes for the commodities: 100,190 (wheat except durum wheat, and meslin) for the period from 2004:Q1 to 2011:Q4 and 100,199 (wheat and meslin, not durum wheat, other than seed) for the period from 2012:Q1 to 2021:Q4. A detailed description of the model variables, their descriptive statistics, and data sources is available from the authors upon request.

The dataset of Russian wheat exports to Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia contains a total of 66 quarterly observations. Six observations are missing because Russia did not export wheat to any of the three countries in the South Caucasus in those quarters (cf. Table 7 in the Appendix). The dataset of Kazakh wheat exports to Azerbaijan and Georgia consists of 53 quarterly observations, meaning that 19 observations are missing (cf. Table 8 in the Appendix). Like Russia, Kazakhstan did not export wheat to the two destination countries in the South Caucasus in every quarter.

6 Results and Discussion

The vast majority of empirical studies on RDE use single-equation models with a range of limited information estimation methods (cf. the columns “Model” and “Method” in Table 5 in the Appendix). In addition to the reasons for jointly estimating a linear system of simultaneous equations for RDE models for Kazakh and Russian wheat exports to the South Caucasus, it should be emphasized that the wheat markets of the South Caucasus are geographically and economically both highly interconnected with and dependent on only two major wheat suppliers. Furthermore, the South Caucasus wheat market is interdependent, and decisions on the export price to one country depend on decisions on the export price to the other countries. Therefore, this study uses a system of simultaneous equations and jointly estimates individual equations in order to increase efficiency and achieve more precise results. As the first, Zellner’s Seemingly Unrelated Regressions (SUR) method was applied. The advantage of this method is that it accounts for potential correlation in the error terms across the destination market equations (Goldberg and Knetter 1997, 1999). However, its disadvantage is that it does not correct for simultaneity bias. Second, three-stage least squares (3SLS) estimation for systems of simultaneous equations was used, which corrects for simultaneity bias.

Estimation of the system of simultaneous equations by 3SLS also raises some problems (Goldberg and Knetter 1999). First, the number of instruments might be too large, as the number of Russian and Kazakh competitors is different and varies by destination. Russia competes with Ukraine in the Armenian wheat market and with Kazakhstan in the Azerbaijani wheat market. In the Georgian wheat market, Russia competes with both Kazakhstan and Ukraine. The joint 3SLS estimation of the system of three simultaneous equations implies that cost shifters for the destination countries have to be included in the list of the instrumental variables for all simultaneous equations, even though Kazakh or Ukrainian cost shifters are relevant for the Armenian wheat market (Russia and Ukraine) or for the Azerbaijani wheat market (Russia and Kazakhstan).

To circumvent this problem, endogeneity tests of endogenous regressors of the RDE models were performed for three instrumented variables \(\mathrm{ln}{Q}_{AM}^{RU}\), \(\mathrm{ln}{Q}_{AZ}^{RU}\), and \(\mathrm{ln}{Q}_{GE}^{RU}\) for Russian wheat exports, and for two instrumented variables \(\mathrm{ln}{Q}_{AZ}^{KZ}\) and \(\mathrm{ln}{Q}_{GE}^{KZ}\) for Kazakh wheat exports (cf. Tables A.5 and A.6 in the Appendix). The test results show that the producer price of wheat in Russia \(\left({PPW}^{RU}\right)\) is a strong instrument in all three destination markets. In the case of Armenia and Azerbaijan, the Durbin-Wu-Hausman chi-square test rejects the null hypothesis that the quantity of Russian wheat exports is exogenous at the 5% significance level (cf. Table 9 in the Appendix). For the Georgian destination market, an additional instrumental variable, Russian total wheat export quantity \(\left(T{Q}_{WD}^{RU}\right)\), must be included in the analysis. Similar to Russian wheat exports, the producer price of wheat in Kazakhstan \(\left({PPW}^{KZ}\right)\) is a strong instrument in the Azerbaijani destination market. The Durbin-Wu-Hausman chi-square test rejects the null hypothesis that the quantity of Kazakh wheat exports is exogenous at the 1% significance level (cf. Table 10 in the Appendix). For the Georgian destination, an additional instrument, total Kazakh wheat export quantity \(\left(T{Q}_{WD}^{RU}\right)\), needs to be considered in the RDE analysis.

The results of the RDE model without and with export restrictions estimated by the 3SLS and SUR methods are shown below in Tables 2 and 3 for Russia and Kazakhstan, respectively. All exogenous variables are treated as instruments together with the producer price of wheat and the total export quantity of the exporting country. Because only two excluded instrumental variables were used to estimate the two RDE models, the problem of a large number of instruments discussed by Goldberg and Knetter (1999) was avoided.

6.1 Russian Wheat Exports

Table 2 presents the results for the RDE model of Russian wheat exports estimated by two alternative estimation methods, 3SLS and SUR. Both methods were used to estimate simultaneous Eqs. (2) for Russian wheat exports jointly for all three destinations in the South Caucasus region: Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia, without and with dummy variables to account for export restrictions. The 3SLS and SUR results show that the R-squared values are quite high and range between 0.6878 in 3SLS for Armenia and 0.93 for Azerbaijan. The Durbin–Watson (DW) statistics from the 3SLS estimation are 2.0048 for Armenia, 1.7181 for Azerbaijan, and 1.4026 for Georgia, indicating that serial correlation might not be a significant problem. The same conclusions could be drawn regarding the R-squared and DW statistics for the 3SLS and SUR estimates estimated without dummy variables for export restrictions.

Comparison of the 3SLS and SUR estimates with and without export restrictions provides insight into the presence of simultaneity bias due to a potential correlation of Russian wheat export quantities with the error term of the residual demand Eqs. (2). The endogeneity test of endogenous regressors of RDE for Russia reported in Table 9 in the Appendix performed using the Wu-Hausman F test and Durbin-Wu-Hausman chi-square test shows that the producer price of wheat in Russia \(\left({PPW}^{RU}\right)\) and the total wheat export quantity of Russia \(\left(T{Q}_{WD}^{RU}\right)\) are strong instruments in addition to the exogenous variables for all estimating equations. It is worth noting that these two instrumental variables are excluded from the simultaneous estimation of RDE; however, they must satisfy two requirements: (i) they must be correlated with the included endogenous variables (in this case, Russian export quantities) and (ii) they must be orthogonal to the error terms. The results of the Wu-Hausman F test and the Durbin-Wu-Hausman chi-square test indicate that the null hypotheses for Russian export quantities can be rejected as exogenous regressors at the 1% significance level. The test results of the Hansen-Sargan statistic reported in Table 2 are 70.432 for 3SLS and 196.144 for SUR. This suggests that the specified instruments are exogenous and are not correlated with the error term. The null hypotheses for both estimators cannot be rejected at the 1% significance level.

The primary interest of the estimation results is in the coefficients represented by the parameters \({\eta }_{m}^{RU}\) corresponding to RDE. The absolute value of RDE represents the mark-up over marginal cost; the larger its absolute value, the larger the mark-up over marginal cost, and the more market power an exporter has over export price. According to the results of the 3SLS and SUR estimates, the estimated parameter for RDE is significant for all three destination markets. However, the simultaneity bias of the estimated parameters for RDE appears to be quite large in all three destination markets. The estimated coefficient of RDE for Armenia is − 0.1783 with 3SLS and − 0.1303 with SUR; for Azerbaijan, it is − 0.0815 with 3SLS and − 0.0583 with SUR; and for Georgia, it is − 0.2561 with 3SLS and − 0.159 with SUR.

The mark-up on the marginal cost of Russian wheat exports in the Armenian market estimated by 3SLS is almost 18%. This can be explained by several facts. First, in terms of wheat transportation, Armenia is not as favorably located as Azerbaijan and Georgia. Second, due to the current political tensions, Armenia has closed its borders to Azerbaijan and Turkey. Therefore, as a landlocked country, Armenia can only import wheat from Russia through the Black Sea via Georgia. Third, in terms of wheat transportation, Armenia still has weak infrastructure and predominantly uses Russia’s rail wagons, which gives Russia an advantage (Gafarova 2018, 95). Fourth, according to calculations based on wheat export data provided by APK Inform (2015), on average only 19 Russian companies exported wheat to Armenia from 2006 to 2014, while 40 and 39 Russian companies exported wheat to Azerbaijan and Georgia, respectively, during the same period. Furthermore, the concentration ratio of the top 5 (top 10) Russian wheat companies exporting wheat to Armenia was 77% (91%) from 2006 to 2014. The concentration ratios of the top 5 (top 10) Russian companies exporting wheat to Azerbaijan and Georgia were 65% (81%) and 65% (79%), respectively. The Herfindahl–Hirschman Indexes (HHIs) are 0.211, 0.154, and 0.146, respectively, for Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia from 2006 to 2014. The HHI indicate a moderate concentration of Russian companies in the Armenian wheat market. This might lead to a non-competitive environment in the Armenian wheat market compared to in Georgia and Azerbaijan.

The results of the 3SLS and SUR methods demonstrate that Russian wheat exporters do not have significant market power in the Azerbaijani wheat market, since the RDE coefficient is significant but rather small, with an absolute value of 0.0815 for 3SLS and 0.583 for SUR (cf. Table 2).

This might be explained by several facts. First, self-sufficiency rates for wheat are higher in Azerbaijan (53%) than in Armenia (26%) and Georgia (15%) (ARMSTAT 2022a; AZSTAT 2022a; GEOSTAT 2022a). Second, since 2007, wheat producers in Azerbaijan receive AZN 80 (around EUR 45) of direct subsidies per planted hectare, and the government covers 50% of their seed costs and 70% of their fertilizer costs (Gafarova 2018, 97). This encourages local wheat producers to expand their wheat production. Third, according to calculations based on wheat export data provided by APK Inform (2015), the average number of Russian companies exporting wheat to Azerbaijan from 2006 to 2014 was around 40, which is twice as many as the number of companies exporting wheat to Armenia. Moreover, the concentration ratio of the top 5 (top 10) Russian wheat companies exporting wheat to Azerbaijan from 2006 to 2014 was 65% (81%) compared to 77% (91%) in Armenia. The HHI demonstrate that Russian firms are less concentrated in the Azerbaijani wheat market (HHI = 0.154) than in the Armenian market (HHI = 0.211). This might confirm a more competitive environment in the Azerbaijani wheat market than in the Armenian or Georgian wheat markets. This could mean that the market structure of the Azerbaijani wheat market has significantly better structural conditions for perfect competition than the market structures of the Armenian or Georgian wheat markets.

The 3SLS results suggest that Russian exporters are able to obtain a slightly more than 25% mark-up over marginal costs (15% obtained from SUR) in the Georgian wheat market. The absolute value of the estimated RDE parameters \({\eta }_{GE}^{RU}\) is 0.2561 for 3SLS and 0.159 for SUR (cf. Table 2). This result might be explained by the following: first, Russia has the highest market share in the Georgian wheat market (cf. Figure 3 above). Second, Russia shares a land border with Georgia and enjoys locational advantages compared to Kazakhstan; this makes the export process faster and less costly. Third, even though Russia has on several occasions implemented export restrictions on wheat, Georgia still continues to import wheat from Russia because of their longstanding trade relationship. Fourth, the average number of Russian companies exporting wheat to Georgia (39 companies) was twice as high as the number of Russian companies exporting wheat to Armenia (19 companies) in 2006–2014. Moreover, the concentration ratio of the top 5 (top 10) Russian wheat companies exporting wheat to Georgia was 65% (79%) compared to Armenia, where it was 77% (91%). The HHI show that Russian firms are less concentrated in the Georgian wheat market (HHI = 0.146) than in the Armenian market (HHI = 0.211) but more concentrated than in the Azerbaijani wheat market (HHI = 0.154). This might weaken the competitive environment in the Georgian wheat market compared to the Armenian wheat market but not compared to the Azerbaijani wheat market. It should be noted that these calculations of the market concentration of Russian wheat exports only cover the period 2006–2014. Since then, market concentration may have changed significantly.

The set of demand shifters consists of GDP per capita represented by the parameters \({\alpha }_{m}^{RU}\) of the importing countries, the CPI for food in the importing countries \({\sigma }_{m}^{RU}\), and the time trend by the parameters \({\delta }_{m}^{RU}\). The results show that, with the exception of Azerbaijan, an increase in the GDP of the importing countries stimulates demand for Russian wheat and consequently causes an upsurge in Russian wheat export prices to those countries. The highest increase is observed in Russian wheat export prices to Georgia, while the estimated parameter \({\alpha }_{m}^{RU}\) is not statistically significant. The estimation results for the parameter \({\sigma }_{m}^{RU}\) appear to be plausible for Armenia and Azerbaijan but not for Georgia. Time trend, the other demand shifter, is statistically negative in Armenia and Georgia according to the SUR model results, and statistically negative only in Georgia according to the 3SLS model results. This suggests that, as time passes, Armenian and Georgian demand for Russian wheat decreases slightly, which shifts Russian wheat export prices down. Although the time trend is also negative for Azerbaijan, it is not significant.

The coefficients of the cost shifters determine the factors that constrain the exporting country’s market power in the destination market. On the one hand, the positive and statistically significant parameters of the cost shifters indicate an increase in a competitor’s export costs in the destination market, allowing wheat exporters to charge higher export prices in the destination market. Table 2 shows that the estimated parameters for the exchange rate of the Ukrainian hryvnia \(\left({\beta }_{AMD}^{UAH}\right)\) and the Ukrainian producer price of wheat \(\left({\varphi }_{AM}^{UA}\right)\) is statistically significant in the Armenian market. This means that the pricing behavior of Russian exporters is restricted in the Armenian wheat market by their Ukrainian competitors. The exchange rate between the Kazakh tenge and the Azerbaijani manat \(\left({\beta }_{AZN}^{KZT}\right)\) and the Kazakhs producer price of wheat \(\left({\varphi }_{AZ}^{KZ}\right)\) are positive and statistically significant, indicating that Russian exporters’ market power is constrained by Kazakh wheat exporters in the Azerbaijani market. The interesting conclusion is that the magnitude of the estimated parameters of the cost shifters between Ukrainian and Kazakh wheat exporters competing with Russian exporters is almost the same. Similarly, the destination-specific exchange rate and producer price of Ukrainian wheat are statistically significant in the Georgian wheat market, meaning that the pricing behavior of Russian exporters is restricted by Ukrainian competitors in the Georgian market. On the other hand, the sign of the coefficients of the cost shifters defines whether the competing countries’ products are perfect or imperfect substitutes for the exporting country’s product. Therefore, it can be concluded that Kazakh wheat in the Armenian and Azerbaijani markets, and Ukrainian wheat in the Azerbaijani and Georgian markets are perfect substitutes for Russian wheat. However, this result should be considered with caution, since the quality of Russian wheat is considered lower than that of Kazakh wheat, but higher than that of Ukrainian wheat (Gafarova et al. 2015).

The wheat export ban and export license imposed by the Kazakh government, the wheat export tax and export duty imposed by the Russian government, and the wheat export quota and wheat license imposed by the Ukrainian government are used as exogenous dummy variables in this analysis. The estimation results for the wheat export restrictions appear plausible and provide further explanations as demand shifters. According to both estimators, the 3SLS and SUR, the estimated parameters \({\vartheta }_{m}^{KZ, BN}\) representing the wheat export ban imposed by the Kazakh government are positive and statistically significant for the Armenian and Azerbaijani wheat markets. However, the estimated parameters \({\vartheta }_{AZ}^{KZ,EL}\), which represent the wheat export license imposed by the Kazakh government, are negative and statistically significant only for Azerbaijan. It thus has a negative effect on Russia’s market power in the Azerbaijani wheat market. At the same time, the estimated parameters \({\vartheta }_{AZ}^{RU,ET}\), which represent the wheat export tax imposed by the Russian government, are positive and statistically significant only for Azerbaijan. None of the wheat export restrictions imposed by the Ukrainian government is statistically significant. They therefore have no impact on the market behavior of Russian wheat exporters in the South Caucasus.

6.2 Kazakh Wheat Exports

Table 3 shows the 3SLS and SUR results for Kazakh wheat exports that are jointly estimated for two destinations in the South Caucasus region: Azerbaijan and Georgia. The statistical inference of both estimators indicates a good fit of the RDE model, with R-squared values ranging from 0.4668 to 0.9151 for the 3SLS and from 0.7137 to 0.9146 for the SUR. The value of the DW statistics for the 3SLS estimation ranges from 1.3093 for Azerbaijan to 1.9467 for Georgia, and for the SUR estimation from 1.3194 for Azerbaijan to 1.8929 for Georgia, indicating that there is no autocorrelation problem in the RDE model estimated by Eq. (2). Almost the same statistical goodness of fit was obtained from the 3SLS and SUR estimates of the RDE model for Kazakh wheat exports without considering the dummy variables for wheat export restrictions.

Table 10 in the Appendix presents the results of the endogeneity test for the endogenous regressors of the RDE model for Kazakhstan and shows that the producer price of wheat in Kazakhstan \(\left({PPW}^{KZ}\right)\) and the total wheat export quantity of Kazakhstan \(\left(T{Q}_{WD}^{KZ}\right)\) are good instruments in addition to the exogenous variables for the two simultaneous estimated equations. The results obtained from the Wu-Hausman F test and the Durbin-Wu-Hausman chi-square test showing the null hypotheses for Kazakh export quantities as exogenous regressors can be rejected at the 1% significance level. The test results of the Hansen-Sargan statistics reported in Table 3 are 32.279 for the 3SLS and 103.317 for the SUR, indicating that the null hypotheses for both estimators cannot be rejected at the 1% significance level.

The estimation results of both models and estimators (3SLS and SUR) demonstrate that Kazakh wheat exporters do not have any market power in the Azerbaijani wheat market and they are price takers (cf. Table 3). The estimated parameters \({\eta }_{AZ}^{KZ}\) corresponding to the RDE are statistically significant for Azerbaijan, but the absolute values of 0.0423 for the 3SLS and 0.0309 for the SUR are close to zero. This could be due to several facts that have already been discussed in Sect. 6.1: first, the relatively higher self-sufficiency rates for wheat in Azerbaijan (53%) compared to Armenia (26%) and Georgia (15%) play an important role in building a competitive environment in the Azerbaijani wheat market (ARMSTAT 2022a; AZSTAT 2022a; GEOSTAT 2022a). Second, since 2007, Azerbaijani wheat producers have received government support in the form of a direct subsidy (Gafarova 2018, 99). This increases the number of local wheat producers and contributes to local wheat production in Azerbaijan.

Contrary to the results for Azerbaijan, the 3SLS results for Georgia do not match the SUR results. Rather, the 3SLS results suggest that Kazakh wheat exporters are not able to exercise market power in the Georgian market. The parameter \({\eta }_{GE}^{KZ}\) estimated for the Georgian wheat market is − 0.10 but not statistically significant for the 3SLS. A notable feature of this parameter \({\eta }_{GE}^{KZ}\) obtained from the SUR is that the coefficient is positive and statistically significant at the 1% significance level, but the absolute value of 0.0619 is close to zero.

Again, this result could be due to reasons that have already been discussed in the previous sub-section: first, Kazakh exporters have a weaker market share of the Georgian wheat market than Russian wheat exporters; therefore, Kazakh exporters are not able to exercise market power in Georgia (cf. Figure 3 above). Second, Kazakhstan does not share a border with Georgia, and Kazakh wheat is usually exported to Georgia through Azerbaijan. The transaction costs make the export process slower and more expensive.

The estimation results for the set of demand shifters represented by the parameters \({\alpha }_{m}^{KZ}\) for GPD per capita, \({\sigma }_{m}^{KZ}\) for CPI, and \({\delta }_{m}^{KZ}\) for the time trend are not statistically significant. It is worth noting that the time trend did not significantly affect the estimation results for both models and estimators for Kazakh wheat exports. However, the partial seasonal quarterly dummies represented by the parameters \({\tau }_{m,Q2}^{KZ}\), \({\tau }_{m,Q3}^{KZ}\), and \({\tau }_{m,Q4}^{KZ}\) are statistically significant for the Azerbaijani wheat market but not for the Georgian market.

The estimated parameters for the set of cost shifters containing the exchange rate of the Russian ruble to the Azerbaijani manat \(\left({\varphi }_{AZ}^{RU}\right)\) and the producer price of wheat in Russia \(\left({\varphi }_{AZ}^{RU}\right)\) are positively significant in the Azerbaijani market, according to the results of both estimators and models (see Table 3). However, the exchange rate of the Ukrainian hryvnia to the Azerbaijani manat \(\left({\varphi }_{AZ}^{UA}\right)\) and the Ukrainian producer price of wheat \(\left({\varphi }_{AZ}^{UA}\right)\) are not statistically significant in the Azerbaijani market, according to the results of both estimators and models. On the one hand, this probably reflects the fact that Kazakhstan’s potential market power in the Azerbaijani wheat market is constrained by Russian exporters but not by Ukrainian exporters. On the other hand, the estimation results suggest that Russian wheat is considered a much better substitute for Kazakh wheat than Ukrainian wheat.

None of the estimated parameters for the destination-specific exchange rate of Russia \({\beta }_{GEL}^{RUB}\) is statistically significant in the Georgian wheat market. However, the destination-specific exchange rate of Ukraine is positively significant in the Georgian market for the 3SLS of both models. This means the 3SLS results argue that Kazakhstan’s market power in the Georgian market is constrained by Ukrainian exporters but not by Russian exporters. Additionally, Kazakhstan’s market power is restricted more effectively by Ukrainian exporters in the Georgian wheat market than it is by Russian exporters in the Azerbaijani market. Again, this finding might be explained by the geographic proximity of the exporting countries to the importing countries. As the sign of the cost shifters could provide an indication of the product type and whether it is a perfect or imperfect substitute for the competing countries’ products, it can be concluded that Russian wheat is a perfect substitute for Kazakh wheat in the Azerbaijani market. On the other hand, in the Georgian market, Russian wheat is an imperfect substitute (only 3SLS results), while Ukrainian wheat is a perfect substitute for Kazakh wheat. However, this result again should be considered with caution, since Kazakh wheat is considered to be of much higher quality than both Russian and Ukrainian wheat.

With respect to export restriction policies, none of the estimated parameters for the wheat export license imposed by the Kazakh government, the wheat export tax and the export duty imposed by the Russian government, and the wheat export quota imposed by the Ukrainian government is statistically significant in either the Azerbaijani or the Georgian wheat markets (see Table 3).

Table 4 below summarizes the results achieved from the 3SLS estimation for the RDE model of Russian and Kazakh wheat exports and compares their market share in the South Caucasus countries.

The general conclusion is that there is an inverse relationship between the RDE coefficient and the market shares of the competing countries over the period 2004–2021. When competitor countries can only achieve a smaller market share, an exporting country maintains its higher market power. Russian exporters have a higher market share than their competitors (Kazakhstan and Ukraine) in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia. Therefore, they can achieve greater market power in those importing countries. Russian exporters have a relatively higher market share in the Azerbaijani and Georgian wheat markets than Kazakh exporters, but have less market power in the Azerbaijani wheat market than in the Armenian and Georgian ones.

The results obtained in this study are partially consistent with a previous study by Pall et al. (2014), who used an RDE model consisting of a single-equation estimation. The authors found that the market powers of Russian wheat exporters is much stronger in the Azerbaijani market (− 0.17**) than in the Georgian market (− 0.06***). Our results for Kazakh wheat exporters support the findings of Glauben et al. (2014), as they argue that Kazakh, Russian, and Ukrainian wheat exporters are not able to exercise market power, and face perfect competition in the South Caucasus region.

7 Conclusions and Policy Implications

The estimation results of both models, with and without the inclusion of dummy variables for export restrictions, and of both estimators, the 3SLS and the SUR, show that Kazakh exporters are not able to exercise market power in the Azerbaijani and Georgian wheat markets. However, the estimation results for both models point to empirical evidence that Russian wheat exporters are able to exercise market power in all three target markets in the South Caucasus region—Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. The estimation results for the RDE coefficients show that the SUR results significantly underestimate the residual demand elasticity of Russian exports to all three South Caucasus countries and of Kazakh exports, except to Georgia. Similar results using the 3SLS and SUR methods were also obtained by Goldberg and Knetter (1999).

The results of the cost shifters obtained using both models and methods show that both exporting countries significantly affect each other’s market powers in the Azerbaijani wheat market. Similarly, Ukrainian wheat exporters constrain Kazakh and Russian market powers in the Georgian markets. Russian exporters more effectively constrain Kazakh market powers in the Georgian market than in the Azerbaijani market. Similarly, Kazakh exporters more effectively constrain Russian market powers in the Armenian market than in the Azerbaijani market, and Ukrainian exporters more effectively constrain Russian market powers in the Azerbaijani market than in the Georgian market.

Wheat export restrictions applied by the exporting countries have a positive and statistically significant impact on increasing Russian market power in the South Caucasus. The wheat export license imposed by the Kazakh government significantly contributed to the exercise of market power by Russian exporters in the Armenian wheat market but not in the Azerbaijani wheat market. It should be noted that the estimated RDE of Russian exporters is higher in the Armenian wheat market than in the Azerbaijani wheat market. However, the wheat export tax imposed by the Russian government had a positive and statistically significant effect on the growing market power of Russian exporters in the Azerbaijani wheat market. It is very interesting that wheat export restrictions imposed by the Kazakh government had a negative impact on Russian market power in the Azerbaijani market (export license) and in the Georgian market (export ban). However, none of the wheat export restrictions (quotas and licenses) imposed by the Ukrainian government was statistically significant, nor did they affect the RDE results, given the market powers of the Russian and Kazakh exporters.

This study shows that imperfect competition exists in the Armenian and Georgian wheat markets but not in the Azerbaijani wheat market. These results are plausible and consistent with the market structures of the importing countries (number of firms, market concentration, market shares, government intervention and regulation). Therefore, considering the findings of this study, the following three policy implications could contribute to reducing the market power of Russian exporters in the wheat importing countries of the South Caucasus: First, trade negotiations between the countries of the South Caucasus and non-KRU wheat exporting countries could encourage diversification and limit Russian market power. Second, to improve the competitiveness of the domestic market, domestic wheat production should be promoted in all three South Caucasus countries, especially in Armenia, as wheat self-sufficiency is very important for food security. Third, wheat importing countries should establish a government food procurement agency similar to the General Authority for Supply Commodities (GASC) in Egypt. GASC manages nearly half of Egypt’s wheat imports and promotes competition among trading companies participating in tenders (Heigermoser et al. 2021). GASC tenders create market and price transparency by having wheat exporting companies submit price bids.

Further empirical research is needed to extend the analysis of the increasing food security problems related to wheat production and competition in international and domestic wheat markets in light of the following. First, a large number of wheat importing countries on the one hand and a small number of wheat exporting countries on the other may lead to increasing market concentration in the world wheat market. High market concentration can lead to rising world prices and the exercise of market power by wheat exporting countries in the wheat markets of importing countries that are highly dependent on wheat imports. Second, many countries are highly dependent on wheat from the Black Sea region. Wheat exporting countries such as Kazakhstan and Russia have a strong position not only in the South Caucasus but also in Central Asia and the Middle East and North Africa. Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine, its occupation of the main wheat growing area in southeastern Ukraine and its blockade of most of the Ukrainian Black Sea and Sea of Azov ports, is seriously affecting global food security. Ukraine is also Russia’s major competitor in the world wheat market, and the destruction of infrastructure, reduction of production capacity, and lack of investment could cause Ukraine to lose its position in the world wheat market. Third, climate change and warming temperatures could negatively impact wheat production not only in Ukraine and Kazakhstan but also in other countries around the world. This could further lead to a reduction in the supply of wheat and competition on the world market, thus threatening food security in many countries.

Data Availability

Data sets supporting the results of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author, Oleksandr Perekhozhuk.

References

APK Inform (2015) Agribusiness Information Consulting Company APK Inform, Dnipro. www.apk-inform.com. Accessed 05 July 2022

ARMSTAT (2022a) Statistical bulletin. Food Security and Poverty, January-December 2014. www.armstat.am. Accessed 05 July 2022

ARMSTAT (2022b) The demographic handbook of Armenia. http://www.armstat.am/en/?nid=82&id=1729. Accessed 05 July 2022

AZSTAT (2022a) Statistical bulletin. Plant products balances. The State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Baku. www.stat.gov.az. Accessed 05 July 2022

AZSTAT (2022b) Political division, population size and structure. The State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Baku. www.stat.gov.az. Accessed 05 July 2022

Baker JB, Bresnahan TF (1988) Estimating the residual demand curve facing a single firm. Int J Ind Organ 6(3):283–300

Carter CA, MacLaren D, Yilmaz A (1999) How competitive is the world wheat market? Working paper, No.99–002. Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of California, Davis

Chang T, Inoue M (2013) Market power in the log and lumber import market in Japan. J Appl Econ Res7(2):131–146

Cho G, Jin HJ, Koo WW (2002) The competitive structure of U.S. grain exports in Asian countries. In: Paper presented at Annual Conference of the American Agricultural Economics Association (AAEA), Long Beach, California

Djuric I, Götz L, Glauben T (2015) Are export restrictions an effective instrument to insulate domestic prices against skyrocketing world market prices? The wheat export ban in Serbia. Agribusiness 31(2):215–228

FAOSTAT (2022) Statistics Division of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. www.fao.org/faostat/en/. Accessed 05 July 2022

Felt M-H, Gervais J-P, Larue B (2011) Market power and import bans: the case of Japanese pork imports. Agribusiness 27(1):47–61

Gafarova G, Perekhozhuk O, Glauben T (2015) Price discrimination and pricing-to-market behaviour of Black Sea region wheat exporters. J Agric Appl Econ 47(3):287–316

Gafarova G (2018) Price discrimination and market power in the international wheat market: the case of Kazakhstan, Russia and Ukraine. Doctoral thesis. Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, Germany. https://doi.org/10.25673/13525

GEOSTAT (2022a) Food security information: food balance sheets. National Statistics Office of Georgia, Tbilisi. www.geostat.ge. Accessed 05 July 2022

GEOSTAT (2022b) Population. National Statistics Office of Georgia, Tbilisi. www.geostat.ge. Accessed 05 July 2022

Glauben T, Imamverdiyev N, Perekhozhuk O, Prehn S (2014) Competitive structure of Kazakhstan, Russia and Ukraine in world wheat market: gravity model approach. In: Paper presented at the XIV Congress of the European Association of Agricultural Economists, Ljubljana

Glauben T, Loy J-P (2003) Pricing-to-market versus residual demand elasticity analysis of imperfect competition in food exports: evidence from Germany. J Agric Food Ind Organ 1(1):1–21

Goldberg PK, Knetter MM (1997) Goods prices and exchange rates: what have we learned? J Econ Lit 35(3):1243–1272

Goldberg PK, Knetter MM (1999) Measuring the intensity of competition in export markets. J Int Econ 47(1):27–60

GTA (2022) Global Trade Alert. www.globaltradealert.org. Accessed 05 July 2022

GTIS (2022) Global Trade Information Services. Online trade data system known as the Global Trade Atlas. www.gtis.com/gta. Accessed 05 July 2022

Heigermoser ML, Götz L, Svanidze M (2021) Price formation within Egypt’s wheat tender market: implications for Black Sea exporters. Agric Econ 52(3):819–831

IMF-IFS (2022) International Monetary Fund (IMF), International Financial Statistics (IFS) https://data.imf.org. Accessed 05 July 2022

KAZSTAT (2022) Agency of the Republic of Kazakhstan on Statistics, Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan. www.stat.gov.kz. Accessed 05 July 2022

Kim J (2010) Recent trends in export restrictions. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 101, OECD Publishing

Pall Z, Perekhozhuk O, Teuber R, Glauben T (2013) Are Russian wheat exporters able to price discriminate? Empirical evidence from the last decade. J Agric Econ 64(1):177-196. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-9552.12006

Pall Z, Perekhozhuk O, Glauben T, Prehn S, Teuber R (2014) Residual demand measures of market power of Russian wheat exporters. Agric Econ 45(3):381–391

Poosiripinyo R, Reed M (2005) Measuring market power in the Japanese chicken meat market. Journal of International Agricultural Trade and Development 1(2):135–148

Reed R, Saghaian SH (2004) Measuring the intensity of competition in the Japanese beef market. J Agric Appl Econ 36(1):113–121

ROSSTAT (2022) Russian Federal State Statistics Service. Moscow. https://rosstat.gov.ru. Accessed 05 July 2022

Silveira JW, Resende M (2020) Competition in the international niobium market: a residual demand approach. Resour Policy 65:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2019.101564

Song B, Marchant MA, Reed MR, Xu S (2009) Competitive analysis and market power of China’s soybean import market. Int Food Agribusiness Manag Rev 12(1):21–42

Uhl KM, Perekhozhuk O, Glauben T (2016) Price discrimination in Russian wheat exports: evidence from firmlevel data. J Agric Econ 67(3):722–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-9552.12118

Uhl KM, Perekhozhuk O, Glauben T (2018) Russian market power in international wheat exports: evidence from a residual demand elasticity analysis. J Agric Food Ind Organ 1(2):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1515/jafio-2016-0026

Uhl KM, Perekhozhuk O, Glauben T (2019) Russian market power in international wheat exports: evidence from a residual demand elasticity analysis. J Agric Food Ind Organ 17(2):1-13. https://doi.org/10.1515/jafio-2016-0026

UKRSTAT (2022) State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Kyiv, Ukraine. https://ukrstat.gov.ua/. Accessed 05 July 2022

WB-WDI (2022) World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI) Database. www.worldbank.org. Accessed 05 July 2022

Xie J, Zhang D (2014) Imperfect competition and structural changes in the US salmon import market. Mar Resour Econ 29(4):375–389

Yang S-R, Lee W-J (2001) Exporters’ market power in agricultural import markets in Korea. In: Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the American Agricultural Economics Association (AAEA), Chicago

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the JICT Editor and anonymous referees for their very helpful comments, suggestions and supports. We acknowledge the support of the Volkswagen Foundation, Germany, through the MATRACC Project “The Global Food Crisis – Impact on Wheat Markets and Trade in the Caucasus and Central Asia and the Role of Kazakhstan, Russia and Ukraine” (Award Number: 86066). The authors are responsible for any errors.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study has been developed in the MATRACC Project “The Global Food Crisis – Impact on Wheat Markets and Trade in the Caucasus and Central Asia and the Role of Kazakhstan, Russia and Ukraine” (Award Number: 86066) and is partly funded by the Volkswagen Foundation, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have been personally and actively involved in substantial work leading to the paper, and will take public responsibility for its content. The authors are responsible for any errors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The authors never required any ethics approval for the study.

Informed Consent

None; the research never involved humans or animals.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gafarova, G., Perekhozhuk, O. & Glauben, T. The Oligopolistic Behavior of Kazakh and Russian Wheat Exporters in the South Caucasus: Evidence from a Residual Demand Elasticity Analysis. J Ind Compet Trade 23, 1–32 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-023-00396-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-023-00396-0

Keywords

- Black sea wheat trade

- Imperfect competition

- Market power

- Residual demand elasticity

- Wheat export restrictions

- South Caucasus

- Russia

- Kazakhstan

- Ukraine