Abstract

Which institutions encourage high-growth entrepreneurship to emerge and to be sustained? Building on institutional theory, this study exploits a sample of 239,911 observations for micro, small, and medium–sized firms from Bulgaria during the period 2001–2010 and finds three types of effects: first, informal institutional constraints such as corruption significantly reduce both the probability to become a high growth firm and the sustainability of growth. Second and unexpected from most of the literature, formal institutional constraints do not discourage firms from pursuing their growth ambitions and even enhance further growth. Third, constraints related to institutional governance, notably limited access to finance, have a negative effect before high-growth, but become less relevant after the high-growth spurt. Results imply that institutional reforms represent a policy tool for supporting high-growth entrepreneurship in an emerging economy context. They also suggest, however, that steadiness in reform efforts is necessary, as informal institutions, which matter most, are particularly slow to change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

High-growth firms are a popular target of public policy (Autio and Rannikko 2016; Grover et al. 2019; OECD 2013) following evidence that only a small number of fast growing firms creates the majority of job and output growth (Birch and Medoff 1994; Bravo-Biosca et al. 2016; Henrekson and Johansson 2010; Storey 1994). At the same time, high-growth is hard to predict (Coad and Srhoj 2019). Contradicting views widely held, high-growers are not predominantly small start-ups in high-tech industries (Daunfeldt et al. 2015) but can be larger and established firms (Henrekson and Sanandaji 2014; Weinblat 2017), originating from a variety of industries and operating across a range of locations (Coad et al. 2014; Henrekson and Johansson 2010).

Rather than trying to directly support future winners within this heterogeneous group of firms, it might therefore be more promising to improve the external environment necessary for high-growth entrepreneurship to unfold. This approach builds on institutional theory, which views institutions as rules of the game for interaction influencing transaction and production cost and hence the profitability of engaging in entrepreneurial activity (North 1991, 1994). It specifically follows the central proposition by Baumol (1996) that institutions incentivize the allocation of entrepreneurial efforts towards productive, growth-oriented activities — depicted as high-growth entrepreneurship in this study — rather than unproductive, rent-seeking purposes.

Extant empirical evidence indeed largely supports that institutions matter for start-ups and small businesses, especially in emerging countries with less-developed institutions (Aidis et al. 2008; Bjørnskov and Foss 2016; Bruton et al. 2010; Manolova et al. 2008; Tonoyan et al. 2010). Insights on young and small firms, however, are only useful to a limited extent in explaining the enabling environment for high-growth entrepreneurship. As argued above, not all high-growth firms start out small and young. Moreover, many new entrants have no intention to grow (Hurst and Pugsley 2011; Sanandaji and Leeson 2013; Shane 2009) representing ‘necessity-push’ firms created for lack of alternative ways of earning a living (Welter and Smallbone 2011) rather than growth-oriented, productive ventures.

To gain a deeper understanding of the link between institutions and high-growth entrepreneurship, I thus investigate two closely related research questions: (a) which institutions affect the prevalence of high-growth firms and (b) which institutions affect the persistence of high-growth firms? Building on the classification of institutions by Williamson (2000), I distinguish between informal institutions (measured by corruption, crime, and mal-functioning courts), formal institutions (measured by licensing and permits, customs and trade regulation, labour regulation, tax regulation, and tax rate), and institutional governance (measured by access to finance, skilled labour, land, transportation infrastructure, and electricity). I test the hypotheses derived from the theoretical framework based on a sample of 239,911 firm observations in the emerging economy of Bulgaria. The dataset is constructed from administrative sources collected in Amadeus as well as perceptions of institutional constraints from the Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Surveys (BEEPS). It covers the period 2001–2010 and offers rich information on firms from the smaller end of the size distribution. Measuring growth by the absolute number of jobs created, I employ probit and linear fixed effect models to estimate whether institutional constraints matter for the prevalence and persistence of high-growth entrepreneurship.

In doing so, this study contributes to both the literature on institutions and high-growth firms in several ways. Most importantly, this is the first test of whether the same institutional constraints affecting the likelihood of becoming a high-growth firm also influence the growth performance after the high-growth period. Both time perspectives, before and after high-growth, warrant closer inspection, because many high-growth firms are unable to continue to grow (Coad and Holzl 2009; Daunfeldt and Halvarsson 2015; Erhardt 2021; Moschella et al. 2018). Thus, by analysing whether and which institutions contribute to an environment where growth spurts do not remain an episode but the beginning of a sustained growth process, this study gains relevance for policymakers willing to support high firm growth. Moreover, firms change over the course of the high-growth period. They do become not only larger, but also more experienced and acquire a record of accomplishment. The effect of institutions on firm growth, in turn, could differ along with these changes. Regulatory burden, for example, may discourage smaller and younger firms from pursuing high-growth ambitions but might support further expansion after high growth by acting as entry barrier to new competitors. Policies that exclusively focus on institutions encouraging the emergence of high-growth firms and disregard further growth might consequently lead to unintended effects.

As a further contribution to the literature, this study operationalizes productive entrepreneurship by having actually experienced high-growth and accounts for the heterogeneity of high-growth firms. One approach in previous studies is to focus on whether institutions drive or hinder entrepreneurs’ growth aspirations (Autio and Acs 2010; Bowen and Clercq 2008; Estrin et al. 2013; Stenholm et al. 2013). However, growth aspirations are not necessarily reflected in actual growth (Wiklund and Shepherd 2003). This is well illustrated for Bulgaria, where high-growth aspirations are found to be among the lowest of all countries surveyed by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, whereas the share of actual high-growth-firms is among the highest in Europe based on administrative data (Eurostat 2018). Hence, the approach used in this study is to investigate the influence of institutions on actual high-growers defined as the top 1% of micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises in terms of absolute growth in employment over a 3-year period. Next to measuring actual high-growth and including firms of all sizes, this definition also requires a minimum increase of 19 employees for qualifying as high-growth firm compared to 0.73–4.4 employeesFootnote 1 in previous studies on actual high-growth (Cuaresma et al. 2014; Krasniqi and Desai 2016; Lee 2014). Given that the attention to high-growth firms by both academia and policymakers originates from their contribution to job creation (Coad et al. 2014), insights for the specific set of high-growth firms used in this study are considered a particularly important extension to the literature.

In what follows, the next section sets out the theoretical foundations for linking institutions to entrepreneurship and develops hypotheses for the influence of institutional constraints on the prevalence and persistence of high-growth. Then, I provide details on the data used and the research methodology before presenting the results of the analysis. I conclude with a discussion of findings, limitations of the analysis, and possible future research avenues.

2 Theory and Hypotheses

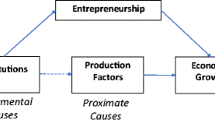

The analytical framework for investigating the relationship between institutions and the allocation of entrepreneurial efforts towards productive, high-growth activities builds on new institutional economics. North (1991) distinguishes between formal institutions (rules, laws, constitutions) and informal institutions (customs, traditions, norms, codes of conduct) that influence how formal institutions operate in practice. Although this classification is frequently used (Krasniqi and Desai 2016; Tonoyan et al. 2010), it has also been argued that additional framework conditions related to inputs and infrastructure shape the impact of institutions on entrepreneurial activity (Estrin et al. 2013; Hoskisson et al. 2013; Lee 2014; Stenholm et al. 2013; Veciana and Urbano 2008). I therefore turn to Williamson (1998; 2000) who extends North’s distinction between formal and informal institutions.

Williamson (2000) groups institutions into a four-level hierarchy with each level placing constraints on the ones below. He positions informal institutions as defined by North (1991) at the top of the hierarchy because they are the deepest-rooted and the slowest changing. He accordingly labels this first level ‘social embeddedness’, although I will continue to adhere to the more widely used term informal institutions. One example is corruption, which, when widespread, becomes an informal norm and socially embedded (Aidis et al. 2012). Perceptions of crime and mal-functioning courts will serve as further negative indicators of informal institutions.

Formal institutions (‘institutional environment’) are located at the second level of Williamson (2000) hierarchy. They represent codified frameworks and rules designed by the executive, legislative, judicial, and bureaucratic functions of government. Williamson (2000) emphasizes contract laws and property rights as important features of formal institutions. In this study, I focus on the regulatory framework for doing business such as licensing requirements, trade or labour regulations, and taxation.

While formal institutions define the ‘rules of the game’, Williamson (2000) argues that the ‘play of the game’ is located on an additional third level — the governance of institutions. He explains his focus on governance by giving the example of contracts. Even though contract laws are ex ante defined at the second level, the ex post stage of contract management, usually directly dealt with by the parties, reshapes incentives. In a similar vein, one can argue that access to finance or the availability of skilled labour is influenced by banking and labour regulation at the second level. The move from opportunity discovery to opportunity exploitation, however, ultimately necessitates well-developed private input markets or supply and distribution networks. I consequently operationalize Williamson’s concept of governance by a broad range of framework conditions related to inputs and infrastructure, which shape the play of the game for entrepreneurs.

The fourth level (‘resource allocation and employment’) eventually represents the outcome of a firm, which acts within the institutional context set by the other three levels. In this study, this outcome is high-growth entrepreneurship.

I next proceed with addressing each level of the institutional hierarchy by Williamson in detail and derive hypotheses on the effect of institutions on high growth for each of the two research questions separately.

2.1 Informal Institutions

The development of informal institutions is often captured by corruption (Chowdhury et al. 2019; Estrin et al. 2013; Krasniqi and Desai 2016). Defined as ‘the abuse of public power for private gain’ (Transparency-International 2020, p. 26), corruption increases transaction costs, limits revenues and, thus, determines whether those with entrepreneurial initiative have an incentive to pursue promising opportunities (Anokhin and Schulze 2009). In that sense, corruption acts like a tax discouraging economic activities (Estrin et al. 2013) including those which lead to high growth. In emerging economies of Eastern Europe, typically characterized by high levels of corruption (Transparency-International 2020), firms have accordingly been found to invest less (Johnson et al. 2002a) and stay small (Vorley and Williams 2015) due to the threat of corruption. Following Murphy et al. (1993), it can be argued that corruption is even more detrimental to firms which have experienced high growth. In contrast to subsistence entrepreneurship with little output subject to rent-seeking, high-growth entrepreneurship might attract the attention of corrupt officials. Thus, corruption acts not only like a tax, but also like a progressive tax falling more heavily on firms, which have grown larger and demonstrated superior performance.

I use perception of crime as further indicator for informal institutions, as it is said to capture private rent-seeking (Murphy et al. 1993), in contrast to public rent-seeking captured by corruption. Crime has been found to affect both small and large firms (Ayyagari et al. 2008). Firms having achieved high-growth, i.e. having acquired a stock of wealth such as output, capital, or land should be even more affected.

Similar to Krasniqi and Desai (2016), I consider a mal-functioning judiciary as an additional indicator for informal institutional constraints in an emerging country context as the reference to functioning implies that perceptions focus more on de facto aspects and less on de jure aspects of the court system. Even if the constitution and law formally provide for an independent judiciary, inefficiency and lack of accountability undermine trust in the ability of the state to enforce property rights and contracts in a reliable and impartial manner (Anokhin and Schulze 2009). As a consequence, mal-functioning courts, for example, discourage entrepreneurs from offering trade credit to new customers and trying out new suppliers (Johnson et al. 2002b). This should be particularly relevant for the prevalence of young and small high-growth firms which might be less able to substitute for the lack of well-functioning informal institutions by relying on ongoing relationships and dealing with customers and suppliers located nearby or managed by a friend or relative (Peng 2003). In addition, a widespread perception of mal-functioning courts should also affect the sustainability of high growth, which often requires more complex economic activities involving trade across distance and over time (McMillan and Woodruff 2002). In the light of this, I hypothesize that

-

Hypothesis 1a. Informal institutional constraints are negatively associated with the prevalence of high-growth entrepreneurship.

-

Hypothesis 1b. Informal institutional constraints are negatively associated with the persistence of high-growth entrepreneurship.

2.2 Formal Institutions

While the hypotheses developed for informal institutions propose the same direction of effects on both prevalence and persistence of high-growth entrepreneurship, I expect effects of formal institutional constraints to differ depending on the research question.

Building on Djankov et al. (2002), heavily regulated economies have lower rates of market entry, because cumbersome rules can raise the cost and time required for running a new business up to the point where potential entrepreneurs are discouraged from entering. As suggested by Ciccone and Papaioannou (2007), the time needed to comply with regulation is even more of a constraint for firms in industries with high-growth potential. Countries where it takes more time to register new businesses, thus, saw slower firm growth in industries that experienced expansionary global demand and technology shifts. This is also supported for high-growth aspirations which are negatively influenced by the size of government including taxation (Bowen and De Clercq 2008; Estrin et al. 2013.

Considering ensuing growth trajectories after high growth, however, it can be argued that the costs resulting from the time needed to understand legal requirements and to deal with necessary paperwork fall disproportionally on smaller and less-experienced firms. Costs from regulatory burden add relatively more to the operating costs of these firms, because they need to employ specialists such as tax advisers or consultants to assist with business regulation (Smallbone and Welter 2001). This can be particularly problematic when legislation is changing quickly or overly complex as is often the case in emerging contexts (Aidis et al. 2008). Stigler (1971) moreover proposes in his theory of regulatory capture that regulation can even be acquired by the industry and then designed and operated for its benefit. The same regulatory constraints, which negatively affect entry and high growth, would then raise profits of larger, more experienced firms after high growth by keeping competitors out of the market. Thus, I formulate:

-

Hypothesis 2a. Formal institutional constraints are negatively associated with the prevalence of high-growth entrepreneurship.

-

Hypothesis 2b. Formal institutional constraints are not associated with the persistence of high-growth entrepreneurship.

2.3 Governance of Institutions

Next to informal and formal institutions, high-growth firms require well-developed input markets and infrastructure that provide an opportune environment for innovation and firm expansion.

Among inputs, access to finance is crucial to set up and grow a firm’s operations. A vast theoretical literature points to the importance of financial sector development for economic growth through trading of risks, allocating capital, monitoring managers, or facilitating the trading of goods and services (Levine 1997). Regarding growth at the firm level, various empirical studies support the importance of financing obstacles (Beck et al. 2005; Bravo-Biosca et al. 2016; Brown and Earle 2017; Demirgüç-Kunt and Maksimovic 1998; Rajan and Zingales 1998). Compared to other constraints, limited access to finance is even found to have a particularly negative effect on firm growth (Ayyagari et al. 2008; Pissarides et al. 2003). An OECD survey further shows that ‘the success rate for requests of bank loans is consistently higher for average enterprises than for enterprises experiencing high-growth. Young high-growing enterprises are the least successful in obtaining bank loans due to their lack of credit history and higher perceived risk’ (OECD 2012, p. 108). This view is confirmed by both evidence on firms with high growth aspirations (Bowen and De Clercq 2008) and actual high-growers (Cuaresma et al. 2014; Krasniqi and Desai 2016; Lee 2014). After having managed a period of high growth, however, the impact of finance constraints is likely to become less severe. For example, after having acquired a track-record of high-growth and bankable collateral, access to finance should improve as banks’ assessment of credit risk related to these borrowers changes (Ayyagari et al. 2008; Beck et al. 2005, 2006; Klapper et al. 2006). Moreover, demand for external financing might decline, as firms are more able to fund growth via retained earnings compiled during the expansionary period (Dimelis et al. 2017).

A similar line of reasoning applies to labour input. By definition, firms experiencing rapid employment growth need new employees with relevant professional skills. In fast-expanding industries, competition for talent is particularly fierce (Henrekson et al. 2010). After high growth, skilled workforce should become less of a constraint as former high-growers are more attractive for workers than start-ups or small firms by offering more secured career and employment perspectives. One bad recruitment is also proportionately less costly for larger than smaller firms (Davidsson and Henrekson 2002) and mismatches can more easily be resolved by re-assignment to other tasks.

Limited access to land and premises as third input should equally constrain the fast expansion of firms faced with the challenge to accommodate new staff (Lee 2014). In contrast, I assume that firms having achieved high growth successfully resolved this issue and expect land to be less of a constraint for further expansion.

Finally, good physical infrastructure is a further requirement for growth (Aschauer 1989; Morrison and Schwartz 2012). Transportation and electricity supply enhance interaction or the exchange of ideas, which fuels entrepreneurial ventures (Audretsch et al. 2015; Banerjee et al. 2012) and should matter for both prevalence and persistence of high growth. Overall, I accordingly postulate

-

Hypothesis 3a. Governance constraints are negatively associated with the prevalence of high-growth entrepreneurship.

-

Hypothesis 3b. Governance constraints are not associated with the persistence of high-growth entrepreneurship.

3 Data and Method

The total sample comprises 239,911 firm observations. Table 1 summarizes the data sources, definitions, and descriptive statistics of all variables employed in this study.

3.1 Data Sources

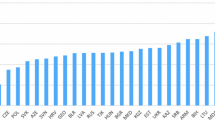

I test the hypotheses based on two data sources. First, I draw on administrative firm-level data collected in Amadeus for the dependent and control variables. Amadeus is a commercial database maintained by Bureau van Dijk and has been previously used to study determinants of high-growth entrepreneurship (Bianchini et al. 2017; Cuaresma et al. 2014). I have access to data for private firms in Bulgaria for the time period 2001–2010. One advantage of the data is that coverage of micro- and small–sized firms is high and increasing over time. As shown in Table A1 in the appendix, at the beginning of the observation period in 2001, the dataset covers about a third of Bulgarian firms and sample firms tend to be larger than the national average (e.g. 75.8% of sample firms are micro-sized compared to a national average of 91.8%). Coverage subsequently increases to about half of firms in 2004. In 2007 and 2010, effectively, all Bulgarian firms are included. In line with this, size differences to national statistics decline in 2004 and vanish from 2007 onwards. Another advantage of the data is that the number of employees, the indicator of growth in this study, originates from social security administration during the time studied,Footnote 2 which further contributes to a high degree of available information for smaller firms.Footnote 3 Given these advantages, I opted for a single-country approach despite its potential limitations to the external validity of findings.

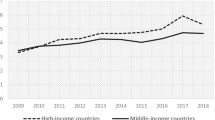

As a second data source, I use the Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey (BEEPS) to obtain information on the institutional environment, i.e. the explanatory variables. The BEEPS is a representative survey of firm owners and managers jointly conducted every 3 years by the Worldbank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.Footnote 4 Due to its 3-year sequencing, it is well suited for the study of high growth as it coincides with the most widely used standard time frame for defining high-growth firms (Coad et al. 2014; Eurostat-OECD 2007). Accordingly, I divide the observation period into three consecutive 3-year periods (2001–2004, 2004–2007, and 2007–2010) and make use of the three BEEPS rounds for Bulgaria in 2002, 2005, and 2008.Footnote 5 Figure 1 illustrates how each high-growth period based on Amadeus is matched with an according survey round on institutional constraints from BEEPS.

In contrast to other surveys on institutional development, BEEPS provides information about the industry at the four-digit ISIC code level in which firms of the responding owners and managers operate.Footnote 6 Given evidence that the influence of institutions on entrepreneurship differs according to industry affiliation (Audretsch et al. 2015; Gohmann et al. 2008), I transform and aggregate this information into NACE codes reported in Amadeus at the two-digit level. Aggregation is motivated by the fact that for the majority of four-digit industries, the BEEPS data is based on the interview of a single firm only, exposing the analysis to the risk of considerable misrepresentation and measurement errors. Before merging the datasets, I further clean the BEEPS data and drop observations of firms that change industry affiliations,Footnote 7 operate in industries not repeatedly surveyed, or operate in industries with less than three observations per survey round. The BEEPS data used in the analysis is then based on 561 observations (170 for the 2002 survey, 190 for 2005, and 201 for 2008) — down from 838 — from firms operating in 10 different two-digit industries. As I am unable to link institutional constraints to firms operating in industries, the BEEPS either does not provide information on or provides information based on too small a number of observations; the final sample includes 239,911 out of 385,466 firm observations covered in Amadeus.Footnote 8

3.2 Country Context

Bulgaria is a representative for the weak institutional environment characterizing emerging economies. The economic freedom index by the Heritage Foundation, a widely used indicator for the level of a country’s institutional development (Gohmann et al. 2008), ranks Bulgaria as ‘mostly unfree’ at the beginning of the observation period in 2001 and as ‘moderately free’ since 2005.Footnote 9 The rankings are below the regional average for Europe, but above the world average. Corruption in public administration, a weak judiciary, and organized crime as well as frequent regulatory and legislative changes are viewed as major constraints to business growth, while rankings for tax burden or trade policies are well above the overall score.

As far as entrepreneurial activity is concerned, self-perceptions about entrepreneurship such as intentions to start a business or actual early-stage entrepreneurship are extremely low compared to other countries (Bosma and Kelley 2019). The share of high-growth firms, on the other hand, is unusually large (Cuaresma et al. 2014; Eurostat 2018; OECD 2016).

Two main events shape the macro-economic context for the studied periods (Fig. 1). The first one is Bulgaria’s accession to the EU as of 2007, which raised great expectations in an improving institutional environment for doing business. As reported in BEEPS, however, ‘optimism after EU accession soon faded when realizing that the general economic and social situation will not change either dramatically or fast. A series of political scandals, mainly related to the spending of EU funds, added to increased pessimism’ (Worldbank 2013, p. 20). Positive shocks to firms such as funding from the EU initiative JEREMIE neither materialized before the end of the observation period in 2010. The second event shaping the context of the analysis is the Great Recession, which started showing its effects by the time of the BEEPS 2008 survey. After a decade of economic recovery following the introduction of a currency board in 1997 (Carlson and Valev 2001), the country was severely affected by the global financial crisis. In 2009, real gross domestic product (GDP) growth turned negative (− 3.6%) after 8 years of rising (from about 4 to 6.5% in the years 2001–2004) and high (in the range of 7% in the years 2005–2008) GDP growth. In 2010, recovery was underway but at a rather muted speed (1.3%) according to Worldbank 2019.

3.3 Dependent Variable

The dependent variable for investigating research question (a) is being a high-growth firm (HGF). In line with the literature (Coad et al. 2014; Daunfeldt et al. 2014), I use the number of employees as the indicator for growth. Amadeus provides information on the number of formal employees as reported to social security at year-end. This includes the owner of a firm, i.e. the minimum firm size in the sample is one and indicates self-employment. I cannot distinguish between full-time and part-time employment, but the latter is very rare in Bulgaria (1.5–3.0% for 2001–2010, OECD 2018).

Interest in high-growth firms primarily arises due to their ability to create employment (Brown et al. 2017; Coad et al.2014). Thus, I define high-growth firms as the 1% of firms with less than 250 employees recording the highest absolute change in employees over 3 years. This divides the sample into 2295 observations of high-growth firms and 237,616 observations of non-high-growth firms. The required minimum increase in employees for being a high-growth firm is 19. Applying the EU definition for the respective size categories, 26% of high-growth firms in the sample are initially micro-sized (< 10 employees), 36% are small-sized (10–49 employees), and 38% are medium-sized firms (50–249 employees). Mean firm size before high-growth amounts to 51 employees and median size is 32 employees.

Concerning the measurement of high growth, there is no consensus in the literature. The absolute growth definition preferred here puts larger firms at an advantage as it is easier for them to add, for example, 10 employees than it is for a small firm. By contrast, a definition based on relative growth favours small firms as they can double their size more easily than large firms.Footnote 10 Methods aiming at balancing relative and absolute approaches by introducing a threshold for initial firm size, such as the one pursued by Eurostat-OECD (2007) by definition exclude all firms below the chosen threshold. For the case of this study, an application of the Eurostat-OECD definition precludes all micro-sized firms from qualifying as high-growth firms, even though they account for 39% of employment growth in this study’s sample. Moreover, the Eurostat-OECD definition implies that the share of firms able to achieve the required relative growth rate, namely at least 20% per annum, varies across the business cycle. Given its use in official statistics, however, I run a robustness check applying the Eurostat-OECD definition of high growth.

With regard to research question (b), I measure persistence as growth over the 3-year period following a high-growth period. I again use the absolute change in the number of employees but take the natural logarithm to account for a non-normal distribution (log F.g).Footnote 11 The sample comprises 816 high-growth firms (2001–2004 or 2004–2007) surviving the subsequent period (2004–2007 or 2007–2010, respectively). Their average size after the high-growth period is 117 employees (85% are medium- and 15% are large-sized). Average subsequent growth (in levels) amounts to − 5.428 employees. It is positive for the period 2004–2007 when macro-economic conditions are favourable (M = 45.446, N = 341) and negative for the recessionary period 2007–2010 (M = − 37.249, N = 475).

3.4 Explanatory Variables

The BEEPS dataset provides information about the assessment of 13 individual constraints across the three survey rounds covered. Based on the theoretical framework, I link each of them to informal institutions, formal institutions, or institutional governance. Accordingly, I subsume corruption, crime, and courts under the heading informal institutional constraints; business licensing and permits, customs and trade regulation, labour regulation, tax administration, and tax rate under formal institutional constraints, and access to finance, skilled and educated workforce, land, transportation, and electricity under institutional governance constraints.Footnote 12

On average (Table 1) firms perceive informal institutional constraints as most binding (2.311), followed by formal institutional constraints (2.053) and institutional governance constraints (1.855). The future high-growth firms perceive constraints to their business activities for all but one institutional variable (tax rate) significantly different than firms which do not make it to the 1% fastest growing firms in the three periods (Table 1, last column). High-growth firms see informal constraints as a more severe constraint to business activities than their peers. This result is driven by corruption and courts, while crime is perceived as somewhat less binding by future high-growers compared to their non-high-growth peers. By contrast, formal institutions are consistently perceived as significantly less constraining by high growth compared to non-high growth firms. Also, governance constraints are perceived as less binding with the notable exception of access to finance.

A more detailed analysisFootnote 13 further reveals that over time, most categories show a pattern where constraints decline from the first to the second period but rise again from the second to the third period. The only exception to this rule is trade regulation, which is perceived as least severe in the third period. Focusing on the development of individual constraints by industry, there is substantial heterogeneity in the overall dynamics of constraint perceptions. For example, firms operating in the two-digit industry manufacturing of machinery see the corruption constraint as becoming continuously less important over time. Firms of all manufacturing industries signal that the access to finance constraint becomes most severe in the third period, while firms in service industries perceive this constraint as most severe in the first period.

3.5 Control Variables

Institutional development is not the only factor driving growth processes of firms. Following the literature (Estrin et al. 2013; Lee 2014), I control for size in terms of the number of employees scaled by 100 at the beginning of a 3-year period (t − 3). As I define high-growth firms by referring to growth in the absolute number of employees, I expect that firm size is positively associated with the likelihood of being a high-growth firm. By contrast, building on theories of industry evolution (Ericson and Pakes 1995; Jovanovic 1982), larger size is expected to be inversely related to further growth.

Age is controlled for indirectly. The dataset does not contain information on the date of incorporation. Following Kandilov 2009, I assign an age of 1 to firms when they newly appear in the database. This results in an observed range of 1–7 years and mean age of 2.446 years with high-growth firms being younger than non-high-growth firms. I acknowledge that this is a highly imperfect measure of age. Yet, I believe that the chosen approach is preferable to alternative choices such as simply using size as proxy for age.

Female controls for the gender of firm owners. The dummy variable takes the value of 1 for female owners and 0 for the remaining firms.Footnote 14Previous research suggests that women-led start-ups in emerging economies record a lower propensity to grow (Manolova et al. 2007). Thus, I expect negative signs in both estimation set-ups.

Legal includes five categories (sole proprietorship, partnership, limited-liability company, joint-stock company, and other). Prior research suggests that high-growth firms are more often registered as limited liability and joint stock companies, where all owners are protected from financial liability (Harhoff et al. 1998).

District controls for the 28 districts of Bulgaria, as entrepreneurial behaviour and outcomes are likely subject to local influences (Lang et al. 2014), such as GDP per capita and entrepreneurial culture. This also holds for Bulgaria where the north and southeast regions are less developed than the southwest region with the capital Sofia. In line with this, firms operating in Sofia are over-represented among high-growth firms (35%) compared to non-high-growth firms (24%).

Finally, I include industry and time controls. Industry affiliation is widely regarded as influencing (high)-growth (Boudreaux 2019; Daunfeldt et al. 2015; Delmar et al. 2003). Descriptive statistics support this view, as high-growth firms originate more often from manufacturing industries and construction and less often from other industries, with the exception of wholesale trade. Time effects further account for the influence of changing macroeconomic conditions, financial turmoil, and political events on the growth process of firms.

3.6 Method

The data consists of firm-level information for the dependent and control variables, industry-level information for the explanatory variables and repeated observations for three time periods.

Research question (a), i.e. the influence of institutional constraints on the prevalence of high growth entrepreneurship and the related hypotheses 1a, 2a, and 3a are tested by estimating a standard probit model. Formally, the model is given by:

where the dependent variable HGFit takes on the value 1 if firm i at time t is a high-growth firm and 0 otherwise. High-growth firms are defined as the 1% of firms with the highest absolute increase in employees over a 3-year period from t − 3 to t among firms with less than 250 employees. By using a time-invariant definition, the share of high-growth firms remains constant over time.

Institutionsj(i)t-3 is the explanatory variable including information on institutional constraints in industry j to which firm i belongs at time t − 3 and the vector xijt-3 comprises both time-varying and time-constant control variables. All variables are measured before high growth at t − 3. Φ (·) denotes the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution. β are the corresponding parameters of the explanatory and control variables estimated via maximum likelihood. Higher values of \(\beta\) mean it is more likely to be a high-growth firm. Since the explanatory variables are grouped by industry, I correct standard errors to account for clustering.

Potential multicollinearity between explanatory variables is generally counterbalanced by the very large sample size. Following Estrin et al. 2013, I, nevertheless, apply a cut-off point of r > 0.7 to bivariate correlations reported in Table 2 for determining alternative specifications.

I additionally estimate specifications of Eq. (1) where institutional constraints are either interacted with each other or with size. In the linear model described below for testing research question (b), the interpretation of interaction terms is straightforward. For the non-linear model used to test research question (a), this is not as trivial. As pointed out by Ai and Norton (2003), the partial effect of an interaction variable cannot be evaluated simply by looking at the sign, magnitude, or statistical significance of its coefficient. Like the partial effect of a single variable, its magnitude depends on all covariates in the model. Against this background, I follow Greene (2010) and employ a graphical analysis of partial effects for interactions. Concretely, I show interaction effects as the change in partial effects (average marginal effects) of one variable with respect to different levels of another variable.

Estimates for Eq. (1) are complemented by a robustness check, which exploits the fact that BEEPS collects a variety of additional information apart from perceptions of institutional constraints. In particular, surveyed firms are asked to indicate the number of employees at the time of the survey (t − 3 according to Fig. 1) and 3 years before (t-6). It is therefore possible to re-estimate Eq. (1) by using survey data from BEEPS not only for the explanatory, but also for the dependent and control variables. All variables are then measured at firm-level. I proceed as follows: the definition of high-growth firms is modified to the fastest growing 10% of firms in order to obtain a sufficient number of high-growth observations for regression analysis. Everything else, i.e. growth indicator (number of employees), growth formula (absolute change), and (3 years) remain unchanged. I also use the same set of control variables as far as possible. Female ownership cannot be used due to a lack of information in BEEPS 2008 and it is necessary to control for five different size categories of cities instead of districts. Further important to note, explanatory and control variables are now measured after high growth has been achieved and information on firm characteristics such as size is self-reported. In total, the resulting sample includes 76 observations for high-growth firms and 633 observations for non-high-growth firms. The small number of high-growth observations implies that it is not possible to run the same robustness check for growth persistence.

As an alternative estimation method,Footnote 15 I further employ conditional (fixed effect) logistic regression in a robustness check. While the model enables to control for unobserved firm-heterogeneity, it is not used for main results because it does not allow to estimate partial effects (Kwak et al. 2021) necessary to investigate the interaction of variables. It neither measures effects of time-invariant variables such as female which is employed to correct for sample selection with respect to research question (b). As a further drawback, a conditional logit model, focusing on within-subject variability, ignores firms where the outcome never changes (i.e. \({HGF}_{it}=1\) or \({HGF}_{it}=0\) in each period). This excludes not only all non-high growth firms, but also more than half of high-growth firms either because they repeat high growth (6%) or because they are only observed for one period. The included firms are thus of larger size at the beginning of the high-growth period (M = 72.347, N = 1041).

To answer research question (b), i.e. the influence of institutional constraints on the persistence of high-growth entrepreneurship, and the related hypotheses 1b, 2b, and 3b, I estimate a linear fixed effects model. The model is specified as follows:

where the dependent variable logF.git is the natural logarithm of absolute growth in the number of employees from time t (end of high-growth period) to t + 3 (end of subsequent period) for high-growth firm i at time t. The explanatory variables are the same as used in Eq. (1). Vector xit-3 now only includes the time-varying control variables (size and age). Time-constant firm characteristics, both observed (e.g. female) and unobserved, are collected in the fixed effects denoted by ai. The inclusion of a firm fixed effect implies that identification works through within-firm changes of institutional constraints over time and limits the sources of bias to factors changing over time and affecting logF.git. Thus, uit represents the time-varying error. In contrast to Eq. (1), the inclusion of a firm fixed effect does not come at the price of reducing the firm sample used to investigate research question (b), because all firms are observed for two periods and none repeats high growth. Parameters β denote the slope coefficients. The coefficient of primary interest remains β1, capturing the effect of institutional constraints on the persistence of high growth.

Multicollinearity among explanatory variables is again investigated based on r > 0.7. Since the sample used for estimating Eq. (2) is restricted to 816 observations, I additionally estimate separate specifications for single constraints related to informal and formal institutions on one hand and governance constraints on the other hand.

The analysis of research question (b) may be subject to potential sample selection bias, because firms which did not grow highly are not part of the sample (incidental truncation). Estimates of the dependent variable yit+3 therefore depend upon HGFit = 1. If being a high-growth firm is systematically correlated with unobserved determinants of yit+3, using only high-growth firms might produce biased estimates of parameters in Eq. (2). The usual approach based on Heckman (1976) is to add an explicit selection equation for the non-truncated sample, which includes at least one so-called identifying variable that affects selection but does not have a partial effect on the dependent variable. The selection equation can then be used for calculating a correction term, which is included in the regression equation for the truncated sample. In a robustness check, I employ female ownership as identifying variable.This choice is motivated by the fact that main results show a significant effect of owner gender on the prevalence of high growth (i.e. selection), but no influence on further growth after the high-growth period (i.e. the dependent variable).Footnote 16 Exogeneity of an identifying variable is not directly testable. From a theoretical point of view, however, it seems plausible that female owners who actually achieved high firm growth are no longer at a disadvantage compared to male owners in sustaining growth afterwards.Footnote 17

4 Empirical Results

Table 3 shows results for the relationship between institutions and the prevalence of high growth entrepreneurship (research question a). Table 4 displays results for institutions and persistence of high-growth entrepreneurship (research question b). I treat each in turn.

4.1 Prevalence of High-Growth Entrepreneurship

I run several specifications of Eq. (1) in order to test which institutional constraints matter for the prevalence of high-growth entrepreneurship (Table (3). Specification 1 reports main results for the three levels of institutional constraints based on Williamson (2000), specification 2 shows main results for each individual institutional constraint, and specification 3 excludes labour regulation and tax administration from the set of explanatory variables given multi-collinearity concerns discussed above. To check for robustness, specification 4 re-estimates results for a sample including exiting non-high-growth firms, specification 5 uses a sample of high-growth firms defined according to Eurostat-OECD (2007), specification 6 employs survey data from BEEPS for all variables, and specification 7 estimates main results by a conditional logit model.Footnote 18 The empirical analysis concludes with the graphical investigation of interaction effects (Figures A1, A2, A3 and A4 in the appendix).

I find that informal institutional constraints are negatively associated with the prevalence of high-growth entrepreneurship (− 0.006, p < 0.05, specification 1) lending support to hypothesis 1a. The magnitude of the effect is also large given that the probability of being a high-growth firm in the main sample amounts to 0.01. Accounting for the three individual informal constraints separately, I find that corruption has a very strong negative influence on the likelihood of high growth (− 0.011, p < 0.05, specification 2) which equally holds for all other specifications. Only in the case of using BEEPS data for all variables, the negative effect of corruption is not confirmed (specification 6). Crime shows a significantly negative effect in specification 3 only (− 0.005, p < 0.10) and effects for courts are consistently insignificant.

Different from expected, I am unable to find evidence supporting hypothesis 2a as the prevalence of high-growth entrepreneurship does not seem to be influenced by constraints on formal institutions, neither as a group nor individually. Only when using the Eurostat-OECD definition, trade regulation constraints show a negative effect, while constraints related to permits have a positive sign (specification 5).

Results are mixed with regard to hypothesis 3a. While governance constraints as a group do not influence the probability of being a high-growth firm, constraints on access to finance have a negative effect (− 0.004, p < 0.10, specifications 2) which holds throughout all specifications. When including exiting firms (specification 4), using BEEPS as single source for all variables (specification 6), or employing a conditional logit model (specification 7) transportation emerges as further binding constraint. Other individual governance constraints, such as the lack of a skilled workforce, have no impact on the prevalence of high growth.

Results for control variables are largely in line with expectations. Firm size effects (in 100 employees) are significant and positive (0.006, p < 0.01) in most specifications indicating that larger firms are more likely to be high-growth firms. In contrast, when using the Eurostat-OECD definition (specification 5) or a conditional logit model (specification 7), the effect of firm size is negative. As for both specifications, the sample is reduced to larger high-growth firms; this points to a non-linear relationship between size and the probability of high-growth.Footnote 19 Age is positively associated with high-growth, but the coefficient is close to zero and not consistently significant across specifications. Female ownership is negatively associated with the prevalence of high growth (− 0.003, p < 0.01). As further reported in Table A2, sole proprietors are less likely to be high-growth entrepreneurs than firms with other legal forms. Location also plays a role, as firms from districts in the less-developed north and south east region are less likely to gain high-growth status than firms operating in the capital Sofia, the reference category. Finally, the affiliation to a two-digit industry other than ‘manufacturing of food and beverages’, an industry recording rapid growth over the last decades and showing positive net exports, is negatively associated with the probability of high growth.

Turning to interaction effects, the graphical analysis reveals that most are not significant. Figure A1 shows that confidence intervals of average marginal effects of formal constraints on the likelihood of being a high-growth firm cross zero at every level of informal constraints, which indicates insignificance. By contrast, the interaction effect of informal institutional constraints with firm size (Fig. A2) is significant up to about 75 employees at p < 0.05 (up to about 100 employees at p < 0.1). In other words, the negative effect of informal institutions on the prevalence of high-growth entrepreneurship seems to be driven by smaller firms. This offers an explanation for the opposite sign of firm size effects in samples with smaller firms (positive) and larger firms (negative). Confidence intervals of interaction effects linking firm size with formal institutional and governance constraints again cross the zero line (Figs. A3 and A4, respectively) suggesting that the link between these constraints and the prevalence of high-growth entrepreneurship is not moderated by size.

4.2 Persistence of High-Growth Entrepreneurship

I also run several specifications of Eq. (2) to test the influence of institutional constraints on the persistence of high-growth entrepreneurship (Table 3). Specification 1 reports main results for the three levels of institutional constraints, specification 2 shows results for individual informal and formal institutional constraints, specification 3 excludes labour regulation and tax administration to check for multi-collinearity among explanatory variables, and specification 4 reports results for individual institutional governance constraints. Specifications 5–7 add robustness checks: specification 5 enlarges the sample by exiting high-growth firms, specification 6 employs the definition for high growth by Eurostat-OECD, and specification 7 applies Heckman maximum likelihood estimation using female as identifying variable for sample selection correction. The empirical analysis again concludes with an investigation of interaction effects (specifications 8 and 9).

I find that informal institutional constraints are also negatively associated with the persistence of high-growth entrepreneurship (− 0.296 or 26%, p < 0.10, specification 1). This lends support to hypothesis 1b and implies that former high-growth firms, which rate informal institutional constraints one point higher on the four-point scale, grow by 26% less over the 3-year period following high growth than their peers. This effect seems to be largely driven by corruption (− 0.389 or − 32%, p < 0.10, specification 2) and negative perceptions on the functioning of courts (− 0.115 or − 14%, p < 0.05, specification 2). Crime is only significant for further growth in the robustness check for Eurostat-OECD high-growth firms (specification 6).

In contrast to the expectation formulated in hypothesis 2b, formal institutional constraints have a significantly positive effect on the persistence of high-growth entrepreneurship (0.451 or 57%, p < 0.05). This mainly holds for business licensing and permits, customs and trade regulations, and tax rates. When included, tax administration constitutes an exception to this rule, as it is negatively associated with growth after the high-growth period. This result might reflect that constraints related to tax administration show a high positive correlation with informal institutional constraints, which were found to negatively impact the expansion of employment after high growth.

Finally, results for institutional governance constraints are again mixed. Main results (specification 1) show that they are not associated with subsequent growth of high-growth firms in line with expectations formulated in hypothesis 3b. When correcting for potential bias from sample selection (specification 6), however, their joint effect is significantly negative. Findings for individual constraints subsumed under institutional governance equally diverge. While coefficients for most constraints, including access to finance, are not significant, limited access to land as well as transportation infrastructure does have a negative impact on the sustainability of growth in specifications 4 and 6.

Turning to interaction effects, there is again no evidence for a joint effect of informal and formal institutional constraints (specification 8). Linking institutional constraints to firm size shows that the — somewhat surprising — positive effect of formal institutional constraints on growth after the high-growth period depends on size (specification 9), i.e. the positive effect becomes larger with increasing firm size. By contrast, interaction terms between size and informal institutional constraints as well as governance constraints are not significant.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

Direct support of high-growth firms is difficult due to their heterogeneous origin from different industries, size classes, or age brackets. This study, hence, investigated whether a viable alternative for policymakers might be found in improving the institutional environment constraining high growth and considered two time perspectives: before and after high growth.

Exploiting data of 239,911 observations for micro, small, and medium–sized firms in Bulgaria over the period 2001–2010 shows that not all type of institutions matter to the same extent. Moreover, for some institutional constraints, their influence on growth is different for the probability of becoming a high-growth firm and for sustaining growth afterwards.

With regard to informal institutions, results support hypotheses 1a and 1b. In almost all specifications, I find that the more severely firms perceive informal institutions as constraining their activities, the less likely these firms are to achieve high growth. Interaction effects with firm size further support that smaller high-growth firms are more negatively affected than larger firms in line with the view that start-ups and young firms are less able to substitute for the lack of well-functioning informal institutions by relying on personal relationships than incumbent and larger firms (Anokhin and Schulze 2009; Peng 2003). Informal institutions also constrain the persistence of high-growth entrepreneurship suggesting both that superior performance increases vulnerability to public rent-seeking (Murphy et al. 1993) and that the inability of the state to facilitate trade across distance constrains further growth (Anokhin and Schulze 2009). Thus, the results of this study are in line with those of other, mainly cross-country, empirical research demonstrating that informal institutions have a negative impact on entrepreneurship (Bowen and De Clercq 2008; Estrin et al. 2013; Urbano et al. 2019; Vorley and Williams 2015).

Concerning formal institutions, I am unable to find evidence supporting hypotheses 2a and 2b: formal institutional constraints do not significantly explain the prevalence of high-growth entrepreneurship and are even positively associated with its persistence. Thus, results of this study reject the line of thinking leading to hypothesis 2a: entrepreneurs with growth ambitions are not discouraged by administrative complexities. This again echoes results of previous cross-country studies failing to establish clear-cut effects of formal institutions on entrepreneurship and growth (Bowen and Clercq 2008; Chowdhury et al. 2019; Stenholm et al. 2013). Some studies even find counterintuitive positive impact of formal constraints. For example, Bjørnskov and Foss 2013 report that an increasingly active involvement of the government and a higher tax burden might positively influence the impact of entrepreneurship on total factor productivity; Krasniqi and Desai 2016 show that perceptions of formal constraints are positively linked to high-growth entrepreneurship in slow-reforming transition countries, among them Bulgaria. I find the same impact on firm growth after the high-growth period. While this rejects hypothesis 2b, the result is consistent with the reasoning that led to expect a less negative impact of formal institutional constraints on sustaining growth compared to the prevalence of high-growth entrepreneurship: when firms have become larger and financially stronger after the high-growth period, they are in a better position to deal successfully with formal institutional constraints than before the high-growth period (Smallbone and Welter 2001) and might even be able to acquire and design regulation for their own benefit (Stigler 1971). The same regulatory constraints, which negatively affect firm entry, can therefore increase growth prospects of larger and more established firms by keeping competitors out of the market. The evidence on interaction effects supports this line of thought as the positive effect becomes more pronounced, the larger the respective firms.

Finally, the support of hypotheses 3a and 3b depends on whether the joint effect of institutional governance constraints is considered or individual effects of constraints subsumed under this heading. In line with expectations, limited access to finance stands out among individual constraints by having a consistent negative impact on the likelihood of becoming a high-growth firm, while growth after the high-growth period is not affected. This confirms previous evidence showing that limited access to finance represents an obstacle to firm growth (Bravo-Biosca et al. 2016; Brown and Earle 2017; Demirgüç-Kunt and Maksimovic 1998; Rajan and Zingales 1998; Cuaresma et al. 2014; Krasniqi and Desai 2016; Lee 2014), which becomes less pressing after firms overcome the liability of smallness, become more experienced, and acquire internal resources for further investments (Ayyagari et al. 2008; Beck et al. 2005, 2006; Klapper et al. 2006). In contrast, changes in size and reputation inherent in the process of experiencing high growth do not relax constraints related to transportation infrastructure or access to land, which continue to impede expansion after the high-growth period.

To sum up, this study identified three types of effects related to institutional constraints and high growth in Bulgaria: first, informal institutions, in particular corruption, are both negative for emerging high-growth firms as well as their future growth. Second, formal institutional constraints linked to regulation do not affect the prevalence of high-growth firms and even enhance sustaining the growth trajectory. Third, limited access to finance associated with institutional governance constraints significantly reduces the probability to become a high growth firm but is less important for further expansion once firms have successfully grown. The results of this study support the view that institutional reform represents a policy tool for supporting high-growth entrepreneurship in an emerging economy in line with Baumol (1996). This holds in particular for informal institutions, notably the fight against corruption, and the development of financial markets. At the same time, the results also suggest that the short-run effects of such policies are limited as informal institutions are the most deeply embedded and slowest to change (Williamson 2000). Thus, while policies of institutional reform might represent a better tool for fostering high-growth entrepreneurship than targeted interventions in markets and firms allegedly representing high-growth characteristics, institutional reforms are unlikely to have direct and immediate effects for high-growth entrepreneurship. This implies that institutional reform policies have to take a long-term view and to show steadiness in their efforts.

The limitations of this study and possible future research arenas are closely intertwined. Most importantly, the dataset is limited to a single country context and three growth periods. Cross-country data for a longer observation period would have enabled the exploration of the following additionally interesting aspects: The comparison of effects for several more and less advanced emerging economies, for example, could lend further support to the negative association between a mal-functioning judiciary and persistence of high-growth entrepreneurship. This effect might not only be related to increased firm size after high growth, but, as argued by Peng (2003), could also be due to the fact that courts become more important for growth once countries transition from relationship-based to rule-based regimes. In the light of centrifugal forces in the European Union such as Brexit, it could moreover prove very worthwhile to compare effects of institutions on high growth (or firm growth in general) before and after EU accession. To this end, it would be necessary to dispose of a considerably longer time series, which comprises several growth periods before and after accession. Most promising, indeed, seems a focus on members such as the ten countries joining the European Union in the year 2004 where accession did not coincide with the Great Recession as in case of Bulgaria.

Data Availability

The raw data used for the dependent and control variables was retrieved from the commercial firm database Amadeus. It is not publicly available due to restrictions by the database provider Bureau van Dijk. Researchers affiliated to institutions subscribing to Amadeus and thus able to download the raw data, can be made available all program (do) files and output files from the author upon request.

Notes

Lee (2014) defines high growth as 20% annualized growth over 2 years and initial size of at least 10 employees (this is met by growing from 10 to 14.4 employees). Krasniqi and Desai (2016) use 10% annualized growth over 3 years and initial size of at least 6 employees (this is met by growing from 6 to 8 employees). Cuaresma et al. (2014) require 20% annualized growth over 3 years (this is met by growing from 1.00 to 1.73 employees).

For later years, Amadeus draws on the company register BULSTAT which was founded after EU accession and where all companies have to register since 2011. An attempt to enlarge the dataset by additional years resulted in missing values on the number of employees for 54% of firms in 2007 (31% of firms in 2010) used in this study with available information.

In case of missing information, employment data is imputed for up to two missing values between existing data points based on moving averages following Delmar et al. (2003). One value is missing for 16% of firms; two values are missing for further 6% of firms. Serial correlation between existing data points is above 0.8.

The BEEPS is part of the World Bank Enterprise Surveys conducted for Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Survey items used in this study are identical with items in Enterprise Surveys for other regions.

Fieldwork was conducted from June to July 2002, March to April 2005, and September to December 2008. Small modifications to the survey methodology were introduced in 2008. See http://ebrd-beeps.com/methodology/ (accessed 6 Dec 2020).

For example, indicators from the Economic Freedom Index by the Heritage Foundation or the Global Competitiveness Index by the World Economic Forum are only available on a national level.

This step was only possible for the panel firms included in the survey.

Further note that I cleaned the sample for firms with an increase or decrease by more than 500 employees over 3-years (about top and bottom 0.1% of the size distribution) as these might reflect non-organic growth or measurement error. Moreover, I excluded firms entering or exiting the dataset throughout a 3-year period for main results. Firm exit is assumed if no information on employees or sales is available for a given year and any subsequent years. Resulting exit rates correspond closely to those reported by Eurostat (2009).

The scale is ‘free’, ‘mostly free’, ‘moderately free’, ‘mostly unfree’, and ‘repressed’.

For example, if I had applied the relative definition used in Cuaresma et al. (2014), this would have resulted in a significantly more imbalanced distribution of high-growth firms (96% micro-, 4% small-, and no medium-sized firm).

Prior to the log transformation, I add a constant value so that min (F.g + a) = 1. For main results a = 450.

To validate this operationalization on statistical grounds, I further ran a principal component analysis reproducing the data structure of the 13 individual constraints with a few principle components or ‘factors’. Using Varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization, the analysis generated a four-factor solution (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy = 0.729, Bartlett’s test p < 0.000, amount of variance explained = 0.785; Communality > 0.7 for all variables. Variables are assigned to factors based on highest ‘loading’ indicating the correlation between a factor and a variable). Overall, the statistical grouping shows a fairly high degree of similarity with the theory-based groups. Concretely, factor 1 is close to informal institutional constraints, as it comprises corruption and courts. For crime, the loading for factor 1 is marginally smaller than for factor 2, which is otherwise very similar to formal institutional constraints. Tax rates move to factor 3 together with access to finance, while skilled workforce moves to factor 2. Land, transportation, and electricity make up factor 4. Jointly, factors 3 and 4 are thus very close to governance constraints.

Descriptive statistics for explanatory variables per period and industry are available from the author upon request.

The variable female is inferred from the name of the ultimate owner based on the gender-agreeing suffix for patronymic and last name (e.g. –ov/ova, -ev/eva). Owners are defined as holding at least 25% of a company. In all but 44 cases (where the first indicated owner was used), the information comprised only one person as owner.

I did not choose a linear probability model because the probability of being a high growth firm is 1% and thus close to zero.

Based on linear regression without firm fixed effects.

In principle, Eq. (2) could also be re-estimated by a Heckman selection model without an identifying variable. In this case, the coefficient of the inverse Mill’s ratio amounts to − 15.989 (p < 0.01) and effects are very similar to main results with slightly smaller standard errors. However, correction of the sample selection bias then solely depends on distributional assumptions (Wooldridge 2010).

Note for the interpretation of coefficients: in specifications (5) and (6), the probability of being a high-growth firm amounts to 9.2% and 10.0%, respectively, compared to 1% for main results. Specification (7) reports logit coefficients, i.e. the rate of change in the ‘log odds’ of the dependent variable as the independent variable changes by one unit. The level of significance and sign is comparable to coefficients in other specifications.

It tested a quadratic specification for the variable size. The coefficient of the quadratic term was significant and negative suggesting a concave relationship between size and the probability of being a high-growth firm.

References

Ai C, Norton EC (2003) Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Econ Lett 80(1):123–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1765(03)00032-6

Aidis R, Estrin S, Mickiewicz T (2008) Institutions and entrepreneurship development in Russia: a comparative perspective. J Bus Ventur 23(6):656–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.01.005

Aidis R, Estrin S, Mickiewicz TM (2012) Size matters: entrepreneurial entry and government. Small Bus Econ 39(1):119–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9299-y

Anokhin S, Schulze WS (2009) Entrepreneurship, innovation, and corruption. J Bus Ventur 24(5):465–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.06.001

Aschauer DA (1989) Is public expenditure productive? J Monet Econ 23(2):177–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(89)90047-0

Audretsch DB, Heger D, Veith T (2015) Infrastructure and entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 44(2):219–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9600-6

Autio E, Acs Z (2010) Intellectual property protection and the formation of entrepreneurial growth aspirations. Strateg Entrep J 4(3):234–251. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.93

Autio E, Rannikko H (2016) Retaining winners: can policy boost high-growth entrepreneurship? Res Policy 45(1):42–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.06.002

Ayyagari M, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Maksimovic V (2008) How important are financing constraints? The role of finance in the business environment. World Bank Econ Rev 22(3):483–516. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhn018

Banerjee A, Duflo E, Qian N (2012) On the road: access to transportation infrastructure and economic growth in China. NBER Working Paper, No. 17897. https://doi.org/10.3386/w17897

Baumol WJ (1996) Entrepreneurship: productive, unproductive, and destructive. J Bus Ventur 11(1):3–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(94)00014-X

Beck T, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Maksimovic V (2005) Financial and legal constraints to growth: does firm size matter? J Financ 60(1):137–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00727.x

Beck T, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Laeven L, Maksimovic V (2006) The determinants of financing obstacles. J Int Money Financ 25(6):932–952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2006.07.005

Bianchini S, Bottazzi G, Tamagni F (2017) What does (not) characterize persistent corporate high-growth? Small Bus Econ 48(3):633–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9790-1

Birch D Medoff J (1994) Gazelles. In L. C. Solmon & A. R. Levenson (Eds.), Labor markets, employment policy and job creation (pp. 159–167). Boulder, CO: Westview

Bjørnskov C, Foss N (2013) How strategic entrepreneurship and the institutional context drive economic growth. Strateg Entrep J 7(1):50–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1148

Bjørnskov C, Foss NJ (2016) Institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth: what do we know and what do we still need to know? Acad Manag Perspect 30(3):292–315. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2015.0135

Bosma N, Kelley DJ (2019) Global entrepreneurship monitor: 2018/2019 global report. GEM. Retrieved from https://www.gemconsortium.org/report. Accessed 25 Feb 2019

Boudreaux CJ (2019) The importance of industry to strategic entrepreneurship: evidence from the Kauffman firm survey. J Ind Compet Trade :1-22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-019-00310-7

Bowen HP, De Clercq D (2008) Institutional context and the allocation of entrepreneurial effort. J Int Bus Stud 39(4):747–767. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400343

Bravo-Biosca A, Criscuolo C, Menon C (2016) What drives the dynamics of business growth? Econ Pol 31(88):703–742. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eiw013

Brown JD, Earle JS (2017) Finance and growth at the firm Level: Evidence from SBA loans. J Fin 72:1039–1080. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12492

Brown R, Mawson S, Mason C (2017) Myth-busting and entrepreneurship policy: the case of high growth firms. Entrep Reg Dev 29(5–6):414–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1291762

Bruton GD, Ahlstrom D, Li HL (2010) Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrep Theory Pract 34(3):421–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00390.x

Carlson JA, Valev NT (2001) Credibility of a new monetary regime: the currency board in Bulgaria. J Monet Econ 47(3):581–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3932(01)00057-5

Chowdhury F, Audretsch DB, Belitski M (2019) Institutions and entrepreneurship quality. Entrep Theory Pract 43(1):51–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718780431

Ciccone A, Papaioannou E (2007) Red tape and delayed entry. J Eur Econ Assoc 5(2–3):444–458. https://doi.org/10.1162/jeea.2007.5.2-3.444

Coad A, Hölzl W (2009) On the autocorrelation of growth rates. J Ind Compet Trade 9(2):139–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-009-0048-3

Coad A, Daunfeldt S-O, Hölzl W, Johansson D, Nightingale P (2014) High-growth firms: introduction to the special section. Ind Corp Chang 23(1):91–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtt052

Coad A, Srhoj S (2019) Catching gazelles with a lasso: big data techniques for the prediction of high-growth firms. Small Bus Econ :1-25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00203-3

Cuaresma JC, Oberhofer H, Vincelette GA (2014) Institutional barriers and job creation in Central and Eastern Europe. IZA J Eur Lab Stud 3(3). https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-9012-3-3

Daunfeldt S-O, Halvarsson D (2015) Are high-growth firms one-hit wonders? Evid from Sweden Small Bus Econ 44(2):361–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9599-8

Daunfeldt S-O, Elert N, Johansson D (2014) The economic contribution of high-growth firms: do policy implications depend on the choice of growth indicator? J Ind Compet Trade 14(3):337–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-013-0168-7

Daunfeldt S-O, Elert N, Johansson D (2015) Are high-growth firms overrepresented in high-tech industries? Ind Corp Chang 25(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtv035

Davidsson P, Henrekson M (2002) Determinants of the prevalance of start-ups and high-growth firms. Small Bus Econ 19(2):81–104. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016264116508

Delmar F, Davidsson P, Gartner WB (2003) Arriving at the high-growth firm. J Bus Ventur 18(2):189–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00080-0

Demirgüç-Kunt A, Maksimovic V (1998) Law, finance, and firm growth. J Fin 53(6):2107–2137. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00084

Dimelis S, Giotopoulos I, Louri H (2017) Can firms grow without credit? A quantile panel analysis in the euro area. J Ind Compet Trade 17(2):153–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-016-0216-110.1007/s10842-016-0216-1

Djankov S, La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A (2002) The regulation of entry. Quart J Econ 117(1):1–37. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355302753399436

Erhardt EC (2021) Measuring the persistence of high firm growth: choices and consequences. Small Bus Econ 56:451–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00229-7

Ericson R, Pakes A (1995) Markov-perfect industry dynamics: a framework for empirical work. Rev Econ Stud 62(1):53–82. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297841

Estrin S, Korosteleva J, Mickiewicz T (2013) Which institutions encourage entrepreneurial growth aspirations? J Bus Ventur 28(4):564–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.05.001

Eurostat (2009) Business demography: employment and survival. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/structural-business-statistics/publications/sif. Accessed 27 Feb 2021

Eurostat (2018) Business demography statistics. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/structural-business-statistics/entrepreneurship/business-demography. Accessed 20 Feb 2021

Eurostat-OECD (2007) Eurostat-OECD manual on business demography statistics. Luxembourg: European Communities / OECD. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/std/39974460.pdf. Accessed 19 Oct 2019

Gohmann SF, Hobbs BK, McCrickard M (2008) Economic freedom and service industry growth in the United States. Entrep Theory Pract 32(5):855–874. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00259.x

Greene W (2010) Testing hypotheses about interaction terms in nonlinear models. Econ Lett 107(2):291–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2010.02.014

Grover A, Medvedev D, Olafsen E (2019) High-growth firms: facts, fiction, and policy options for emerging economies. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Harhoff D, Stahl K, Woywode M (1998) Legal form, growth and exit of West German firms—empirical results for manufacturing, construction, trade and service industries. J Ind Econ 46(4):453–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6451.00083|

Heckman JJ (1976) The Common Structure of Statistical Models of Truncation, Sample Selection and Limited Dependent Variables and a Simple Estimator for Such Models. Ann Econ Soc Meas 5:475–492

Henrekson M, Johansson D (2010) Gazelles as job creators: a survey and interpretation of the evidence. Small Bus Econ 35(2):227–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9172-z

Henrekson M, Sanandaji T (2014) Small business activity does not measure entrepreneurship. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111(5):1760–1765. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1307204111

Henrekson M, Johansson D, Stenkula M (2010) Taxation, labor market policy and high-impact entrepreneurship. J Ind Compet Trade 10(3–4):275–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-010-0081-2

Hoskisson RE, Wright M, Filatotchev I, Peng MW (2013) Emerging multinationals from mid-range economies: the influence of institutions and factor markets. J Manage Stud 50(7):1295–1321. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467_6486.2012.01085.x

Hurst E, Pugsley BW (2011) What do small businesses do? Brook Pap Econ Act 2011(2):73–118. https://doi.org/10.1353/eca.2011.0017

Johnson S, McMillan J, Woodruff C (2002) Property rights and finance. Am Econ Rev 92(5):1335–1356. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282802762024539

Johnson S, McMillan J, Woodruff C (2002) Courts and relational contracts. J Law Econ Organ 18(1):221–277. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/18.1.221