Abstract

This study investigates the nexus between household head gender and poverty vulnerability in the context of China's eradication of absolute poverty. Using a sample of 5061 rural households from the 2018 CFPS database, poverty vulnerability is quantitatively measured through the VEP model and the 3FGLS method. Additionally, the Probit model is employed to elucidate the ties between household head gender and rural household poverty vulnerability. The study uncovers an absence of significant disparity in poverty vulnerability between female-headed and male-headed households overall. However, heterogeneity is observed within female-headed households: de jure female-headed households exhibit greater vulnerability, while De facto female-headed households display the opposite trend. Notably, health risks are accentuated as a decisive factor, with female-headed households, especially de jure ones, experiencing significantly higher health risks than their male-headed counterparts. Moreover, the education level, household income, and assets are positively correlated with reducing poverty vulnerability and facilitating households' escape from poverty. These findings provide important references for formulating poverty alleviation strategies and more effective mechanisms to prevent relapse, thereby alleviating vulnerability to relative poverty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

At the close of 2013, China introduced the concept of "targeted poverty alleviation," aiming to assist poverty-stricken areas and populations across the nation in escaping poverty through accurate identification of the poor, targeted measures implementation, and targeted poverty reduction strategies.Footnote 1 Subsequently, a series of comprehensive measures and actions, including the establishment of "five poverty-related platforms," the implementation of "six poverty alleviation initiatives," and the endorsement of "ten targeted poverty alleviation projects,"Footnote 2 were deployed nationwide.

After seven years of unwavering dedication, China achieved a significant milestone by the end of 2020, eliminating absolute poverty and regional overall poverty. Under the prevailing standards (2300 RMB per person per year, adjusted for constant 2010 prices), an astonishing 98.99 million rural individuals successfully lifted themselves out of poverty, and 832 impoverished counties shed their poverty-stricken status. However, poverty possesses complexity, systematicity, and dynamic variability (Yao & Xie, 2022). In fact, by the end of 2019, nearly 2 million individuals who had previously escaped poverty were at risk of reverting to poverty, and there were approximately 3 million individuals within the marginally vulnerable population teetering on the brink of destitution.Footnote 3 As noted by Sen (1999), the challenges of sustainable development should not only include the elimination of persistent and endemic deprivation, i.e., poverty, but also the removal of vulnerability to sudden and severe destitution. Therefore, this latter issue should also be a concern of high priority from a policy perspective, as success in poverty alleviation may not guarantee success in reducing vulnerability (Chakravarty, 2018). In this regard, identifying who constitutes the vulnerable population, understanding the characteristics of vulnerability, identifying its determinants, and finding appropriate measurement standards become critical elements in devising policies aimed at eliminating this issue (Klasen & Waibel, 2013). This represents a pivotal challenge in China's current poverty governance: adopting a scientific approach to precisely predict the poverty risks of rural householders, conducting causal analyses, and ensuring early identification, intervention, and timely assistance to populations prone to relapse into poverty, thereby ensuring the stable transition of previously impoverished populations out of poverty and preventing the recurrence of poverty among vulnerable populations on the fringes of destitution.

Poverty vulnerability represents a measurement of future risk, with a focus on the probability of experiencing poverty in the future. The concept of poverty vulnerability was formally introduced by the World Bank (2001) in its 2000/2001 World Development Report and is defined as "the likelihood that an individual or household will suffer a decrease in wealth or a decline in the quality of life below a socially recognized threshold due to exposure to certain risks". These risks encompass not only low-income levels but also shocks such as natural disasters and diseases (Ding et al., 2023). Vulnerability to poverty tries to assess the ex-ante poverty risk of households and people (Hohberg et al., 2018), "before the veil of uncertainty has been lifted" (Calvo & Dercon, 2007). In other words, in contrast to the research on poverty, which is regarded as a backward-looking study, due to its ex-post perspective, the work on vulnerability is considered a forward-looking analysis. The vulnerability approach thereby combines risks and shocks into poverty assessment and joins together both strands to make ex-ante evaluations of future poverty risks and explore their drivers.

Currently, despite a wealth of research on household poverty vulnerability, fewer studies have delved into this issue from a female perspective, examining the correlation between the gender characteristics of household heads and household poverty vulnerability. In the 1970s, American economist Pearce introduced the concept of the "feminization of poverty" (Peterson, 1987). Her research found that two-thirds of the impoverished population over the age of sixteen were women, and the welfare situation of female-headed households was deteriorating. According to Pearce's findings, the feminization of poverty encompasses two aspects: the increasing presence of women within the impoverished population and the rising prevalence of female-headed households in poverty. This concept gained global attention, with the Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995 incorporating the issue of impoverished women into the mainstream framework of global development (Pearce, 1978).

In the twenty-first century, the Global Gender Gap Report published by the World Economic Forum evaluated progress in gender equality in four areas: education, health and survival, economic opportunities and participation, and political empowerment. From a global perspective, as of 2021, although gender gaps in education, health, and survival have gradually narrowed, significant gender disparities still persist in economic participation and job opportunities. Among the population aged 15–64, women's labor force participation rate stands at 52.6%, far below the 80% for men. It is worth noting that women have long been engaged in a significant amount of unpaid domestic caregiving work, which has been consistently excluded from economic contribution statistics (Global Gender Gap Report, 2021). Poverty is not j solely a lack of material resources but also a result of "social exclusion" and "capability deprivation". Gender inequality exacerbates the deprivation of women's rights in education, health, economics, and politics, thereby worsening the issue of women's poverty, posing hindrances to the long-term sustainable development of regional and national economies. According to data from the 2020 Seventh National Population Census, China's rural female population has reached 245 million, constituting a major portion of the rural population. The poverty situation they face not only directly impacts individual and family development but also has a profound bearing on the fundamental resolution of long-term relative poverty issues in rural China. Therefore, gaining an in-depth understanding of the poverty issues faced by rural women in China is crucial for formulating more precise and effective poverty reduction strategies.

Therefore, this paper will explore from the perspective of female-headed households in rural areas in China, leveraging data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) to analyze the relationship between household head gender and poverty vulnerability. Additionally, it will explore the relationship between poverty vulnerability and heterogeneous female-headed households. It aims to verify whether female-headed households are more susceptible to poverty, investigating the potential feminization of poverty vulnerability. It should be noted that female household heads cannot be a "proxy" for all women. Although distinguishing between de jure female-headed households and De facto female-headed households is meaningful, it still cannot capture the full diversity and complexity of all women. Additionally, this study measures poverty vulnerability at the household level, assuming that household consumption is evenly distributed among household members, which overlooks gender inequalities in decision-making and resource allocation that may exist within households. Nevertheless, this research offers three primary contributions: Firstly, it delves into poverty vulnerability by specifically examining rural female-headed households, an aspect relatively understudied in China's research on poverty vulnerability. It offers a more detailed and comprehensive understanding of the correlation between gender and poverty vulnerability. Secondly, the study employs data from the CFPS, to scientifically assess poverty vulnerability. This data source is comprehensive and of high quality, providing robust nationwide data support for the research, thus enhancing the persuasiveness and credibility of the findings. Thirdly, this paper employs econometric modeling to analyze the characteristics of poverty vulnerability in rural Chinese female-headed households, deeply exploring the causes of female poverty vulnerability from the perspectives of risk shocks and resilience. This analytical approach facilitates an understanding of the role of gender disparities in poverty vulnerability, offering guidance for future policy formulation and intervention strategies.

Literature Review

Traditionally, it has been widely recognized that women, especially in developing countries, experience poverty due to inequality (Chant, 2006). The World Bank (2012) asserts that female-headed households in developing countries should receive particular attention as they face vulnerabilities in land tenure, labor markets, credit access, and insurance markets (Marcoux, 1998). The formation of these vulnerabilities can be categorized into internal and external factors. Internal factors refer to gender-based physiological differences, inherent biological traits leading to specific health needs for women, including but not limited to childbirth, nutrition, and susceptibility to illnesses, all of which significantly impact women's well-being. External factors encompass economic conditions, social policies, cultural norms, and more (Li et al., 2020). In these spheres, female-headed households experience unfair treatment, relegating them to the fringes of property and power structures.

Based on the theory of poverty capital determinants, individuals need a certain level of livelihood capital to achieve their livelihood goals. Broadly speaking, livelihood capital comprises a "pentagon" structure consisting of human capital, natural capital, physical capital, social capital, and financial capital (Moore, 1994). Existing literature suggests that, in comparison to male-headed households, female-headed households encounter greater challenges in acquiring livelihood capital and possess weaker abilities to cope with risks, rendering them more vulnerable.

From the perspective of human capital, women have unique health needs due to inherent physiological differences. Consequently, women, particularly those in rural areas, often grapple with poorer physical health conditions, unmet healthcare needs, leading them to a state of health poverty (Yuan et al., 2023). Psychologically, they are more prone to despair, a sentiment that might be transmitted across generations, potentially fostering a culture of poverty. Regarding education, disadvantaged educational beliefs and substandard living conditions in impoverished regions deprive women of their right to education. This hampers their capacity building and, subsequently, pushing them into multidimensional poverty (Dong et al., 2007; Pearce, 1978). Among the existing illiterate population, 70% are women, with rural women accounting for three-quarters (Yang, 2014). In the economic sphere, labor markets discriminate against women (Ramírez & Ruben, 2015) and technological advancements further exacerbate gender disparities in employment (Kim, 2016). Women are more likely to be disadvantaged in competition and even face exclusion, rendering them more susceptible to poverty (Burda et al., 2007).

From the perspective of natural capital, the fragility of the ecological environment, harsh natural living conditions, scarcity of water resources, and inadequate healthcare facilities all increase health threats and disease incidence among rural women, hindering improvements in their living conditions (Chen & Standing, 2007). Studies have found that the scarcity of energy resources in developing countries results in women inhaling pollution generated from household chores over extended periods, leading to damage to women's physical and mental health and deepening their poverty (Sovacool, 2012).

From the perspective of physical capital, many women in developing countries occupy subordinate positions within their households. Women raised in patriarchal cultures are more likely to experience injustices in terms of land and asset ownership (Yuan et al., 2023). They face difficulties in obtaining resources such as land and property and struggle to secure income-generating assets. In rural China, ownership of land and capital is typically heavily skewed toward male family members (Ye & Jia, 2010). Particularly when marriages end or families disintegrate, assets like houses, land, household property, and other assets are often lost, leaving women with nothing (Jin, 2011). Due to a lack of protection for women in social systems such as land policies, household registration systems, and marriage systems, women's status is marginalized, and they are pushed into poverty (Sovacool, 2012). Even within the basic consumption of essential resources within households, gender hierarchies exist, with women often in a disadvantaged position (Wang & Ci, 2004). Gender-based disparities in resource ownership exacerbate women's poverty, and poverty, in turn, further skews asset ownership in favor of men (Wang, 2009).

From the perspective of financial capital, gender discrimination in the financial sector is a major obstacle to women's pursuit of equal financial rights (Yang, 2018). Numerous factors stemming from social, cultural, traditional, and economic characteristics serve as the root causes of unequal financial rights for women (King & Lomborg, 2008). In comparison to men, women often lack formal channels to access insurance and credit. The possession of a personal bank account is a fundamental criterion for assessing financial rights. Globally, there exists a gender gap in the proportion of men and women with formal bank accounts, with the gap being more pronounced in South Asia and the Middle East and North Africa regions. Women have lower rates of participation in formal savings and loans compared to men (Yang, 2018). Even specialized interest-free microloans intended for female entrepreneurship often impose barriers for impoverished women due to complex application procedures and increased collateral requirements, ultimately resulting in the majority of impoverished women being unable to access financial assistance (Wu, 2016).

From the perspective of social capital, women are more impoverished in terms of social resources and social network support (Wu & Fan, 2007; Wu & Shi, 2005). Gender disparities not only diminish women's capacity to access social resources and their associated benefits but also affect women's ability to acquire occupational status and negotiate within their professions (Wang, 2018). The traditional marital model of living with the husband leads to the loss of women's social network resources (Li, 2010). Once divorced, the informal social support networks built on marital relationships collapse (Lin, 2005). The limited nature of social interaction networks prevents divorced women from accessing formal social support networks (such as government, social organizations, enterprises, and communities) and informal social support networks (such as social networks formed by blood relations, relatives, industry affiliations, geographical ties, and friends). All these factors contribute to women becoming vulnerable among the vulnerable, ultimately driven by gender-based social relationships (Moghadam, 1998).

Beyond livelihood capital, the ability to cope with risk also directly impacts poverty vulnerability. According to the theory of poverty risk shocks, various risks (including natural, health, economic, political, and environmental) are ever-present within an individual or family's environment, encompassing micro and macro environments such as the economy, society, and the natural world (Yuan et al., 2023). In comparison to other types of households, when various risk shocks impact individual or family welfare, women are more prone to falling into poverty, and their recovery capabilities are weaker. Typically, households respond to risk by selling assets, borrowing, engaging in additional occupations, temporary migration, government support, or reducing educational expenses. For female-headed households, with limited livelihood capital at their disposal, the most viable response often involves reducing expenditures on children's education or increasing the participation of underemployed labor. The immediate consequence is the intergenerational transmission of poverty (Klasen et al., 2015).

Poverty vulnerability refers to the likelihood of individuals experiencing increased impoverishment or an elevated risk of falling into poverty when confronted with disruptive risk factors. This definition broadens the scope of research beyond households living below the poverty line to include those currently above the poverty threshold but vulnerable to worsening economic well-being and potential poverty when exposed to risks (Bartfeld et al., 2015). The measurement of poverty vulnerability and the identification of target populations for anti-poverty policies are critical factors determining the success of public anti-poverty policies in developing countries. Currently, three classical measurement methodologies are prevalent in academia: Vulnerability as Low Expected Utility (VEU), Vulnerability as Expected Poverty (VEP), and Vulnerability as Uninsured Exposure to Risk (VER).

The Vulnerability as Low Expected Utility (VEU) measurement method, initially introduced by Ligon and Schechter (2003), posits that poverty vulnerability occurs when an individual or household encounters uncertain conditions resulting in lower utility compared to the standard welfare effect under poverty. Their research highlights that previous welfare measurements predominantly focused on income and consumption while overlooking factors associated with risk, such as health risks faced by family members, income reductions due to shocks, and unfavorable changes in social structures. In response, they initially selected a utility function incorporating risk preference factors as a measure of welfare. Subsequently, they calculated variables like expected utility at the poverty line level, utility of expected consumption, and expectation of consumption utility, allowing them to dissect poverty vulnerability into a combination of poverty and risk. This vulnerability measurement method incorporates the utility function that reflects individual preferences into the measurement of poverty vulnerability. The utility function employs consumption levels as the benchmark and maintains a constant risk aversion coefficient, with utility levels increasing as consumption levels rise but exhibiting diminishing marginal utility (Naude et al., 2009).

The Vulnerability as Expected Poverty (VEP) measurement method, originally proposed by Pritchett et al. (2000), Hoddinott and Quisumbing (2003), Chaudhuri (), and substantially enhanced by Klasen and Waibel (2015), defines poverty vulnerability as the probability of an individual or household having a future welfare level below the poverty standard. The underlying logic involves regressing income on observable variables and shock factors to derive an expression for future income. It further assumes that the logarithm of income follows a normal distribution, allowing for the estimation of the probability of future income falling below a certain threshold (typically the poverty line). This probability signifies the likelihood of a household falling into poverty in the future (Jiang, 2017). The Vulnerability as Uninsured Exposure to Risk (VER) measurement method, introduced by Dercon and Krishnan (2000), defines poverty vulnerability as the sensitivity of an individual or household's welfare level to risk shocks. The fundamental logic revolves around how households optimize their consumption to maximize utility when confronted with risks. The measurement model based on VEP can be adapted to cross-sectional data, making it widely employed. The VEU method introduces micro-level risk preferences into the effect model to dissect the inequality and volatility of consumption, facilitating a more profound exploration of the determinants of poverty vulnerability. Meanwhile, the VER method can better reflect people's capacity to respond to risks.

Concerning the formation of household poverty vulnerability, factors such as employment and education (Ligon & Schechter, 2003), non-agricultural activities (Wang et al., 2020), social capital (Xie & Yao, 2021), income source diversification, family structure, and household characteristics have led to significant differentiation in individual poverty vulnerability (Xu et al., 2019). On the macro level, economic and fiscal policies (Arden & Murray, 2017), market accessibility (Christiaensen & Subbarao, 2005), social security (Bronfman & Floro, 2012), inclusive finance (Zhang & Yin, 2018), and public transfer payments (Fan & Xie, 2014) are among the factors that influence poverty vulnerability through the intermediary mechanism of "enabling and empowering" (Gao et al., 2020). These micro and macro factors intertwine, with the gender characteristics of household heads, in particular, serving as essential micro-level factors that closely link household poverty vulnerability with the feminization of poverty.

Since its inception, the concept of the feminization of poverty has sparked debates in both theoretical and empirical research. The relationship between gender and poverty is undeniably intricate (Moore, 1994). Qualitatively, it is evident that women and female-headed households are more susceptible to poverty. In China, most scholars have predominantly approached the study of female poverty qualitatively, with relatively fewer quantitative studies. The quantitative studies have primarily focused on the direct measurement of female poverty and the analysis of factors influencing female poverty. For instance, Chen and He (2014) estimated poverty changes from the perspective of female-headed households and found that the depth and severity of female poverty in China are greater than that of males, although a clear trend toward the feminization of poverty is not apparent. Employing a multidimensional relative poverty perspective, existing research has utilized the Alkire-Foster (A-F) method to analyze the impact of factors such as urban–rural divide, region, and age on the vulnerability of women to multidimensional relative poverty. It was discovered that reproductive behavior increases the likelihood of women falling into multidimensional relative poverty by 83.1%. Female laborers are more likely to experience multidimensional poverty, especially in dimensions such as health, education, income, and consumption, where the poverty incidence rate is significantly higher than that of men (Lan et al., 2023; Liu & Liu, 2018; Wei & Li, 2021; Yan & Zhang, 2023). Gao (2016) argued that female education, material capital, social relationships, and employment improvement significantly reduce the likelihood of female-headed households falling into poverty.

Quantitative analyses of the feminization of poverty in Western countries began relatively early. Brady and Kall (2008) compiled income data for post-tax family incomes, excluding transfer payments, from 1969 to 2000 in 18 Western countries. They used a relative poverty standard of below 50% of the median income to calculate the number of impoverished individuals and found that the ratio of female poverty incidence to male poverty incidence was 1.397, and the ratio of poverty intensity was 1.374, indicating that the degree of female poverty measured by relative income was higher than that of males. Medeiros and Costa (2008) measured poverty incidence, intensity, and depth for Latin American women and female-headed households relative to male-headed households using per capita income data. Mba et al. (2018) conducted a statistical analysis of household poverty vulnerability in Nigeria, revealing that female-headed households, rural residence, and larger family sizes have significant positive effects on poverty vulnerability. Mwakalila (2023) studied the impact of male and female household heads on poverty vulnerability in Tanzania, showing that female-headed households are less likely to face extreme poverty. Ichwara et al. (2023) pointed out that female-headed households in Kenya have higher poverty rates than male-headed households but have also experienced a faster decline in poverty rates. In the Ghanaian context, Addai et al. (2022) emphasized the greater susceptibility of female-headed households to food scarcity, highlighting systemic risks in food poverty. Koomson et al. (2020) explored the new impact of inclusive finance on household poverty vulnerability in Ghana, finding that by enhancing financial inclusivity, female-headed households are more likely than male-headed households to significantly reduce poverty and poverty vulnerability.

However, the current literature on the vulnerability of Chinese women to poverty predominantly focuses on theoretical explorations, lacking empirical investigations, particularly concerning the relationship between female household heads and the vulnerability of household poverty. These empirical studies have yet adequately elucidated the correlation of poverty vulnerability among the female population or female-headed households in China. In light of these circumstances, this study first conducts a comprehensive review of existing theoretical frameworks and research methods, attempting to employ a combined quantitative and qualitative analysis approach. We aim to provide a more comprehensive and in-depth quantitative analysis and research on household poverty vulnerability from the perspective of household head gender characteristics, aiming to gain a deeper understanding of the complex role played by household head gender in poverty vulnerability. The conclusions drawn from this study will not only contribute to theoretical advancements but also offer insights for guiding practical policies. Through empirical research into the various factors affecting the vulnerability of female-headed households in China, our study provides new perspectives for formulating policies on gender equality and poverty reduction. In summary, our research offers a fresh viewpoint and methodology for examining poverty vulnerability and its gender differences, providing valuable insights and inspiration for further exploring the relationship between poverty and gender.

Method

Procedure and Participants

This study utilizes data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), a large-scale, cross-disciplinary, nationwide social tracking survey project conducted by Peking University's China Social Science Survey Center (ISSS). By tracking and gathering data at three levels—individual, family, and community—it seeks to represent the changes in China's society, economy, population, education, and health. This serves as a foundational data source for academic research and public policy analysis. To guarantee that the samples are nationally representative, CFPS uses a multi-stage, implicit stratification approach along with a probability sampling method proportionate to population size in urban–rural integration. With the exception of Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, Xinjiang, Tibet, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, and Hainan, the samples encompass 25 administrative regions at the provincial level, accounting for 95% of the nation's total population. The target sample size is 16,000 households, including all family members, and extensively investigates household economic conditions such as income, consumption, employment, and assets, along with demographic characteristics like age, marital status, and level of education. This comprehensive database sufficiently meets the requirements of this study. This research chooses rural samples from provinces other than Beijing, Shanghai, and Chongqing in 2018, taking into account that China's impoverished population is primarily located in rural areas and that rural women in China face more hazards. Acknowledging the diverse reasons for women becoming household heads, this study distinguishes the heterogeneity within female-headed households. These households are further categorized into de jure female-headed households, including widowed, divorced, and single women, and de facto female-headed households, encompassing situations where male household heads are temporarily absent. This differentiation within female-headed households holds significant importance for policy formulation, precise poverty alleviation efforts, and future research endeavors (Buvinic & Gupta, 1997).

The study's indicators are all based on data from 2018. Due to the potential influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the latest 2020 data and its recent update, the data quality remains to be verified. Additionally, 2018, being close to the conclusion of China's poverty alleviation campaign in 2020, holds significant practical importance for studying rural household poverty vulnerability during that period. A total of 5061 samples is obtained after removing invalid samples (including invalid information and missing data). Table 1 displays the household head types, comprising 2856 male-headed households, accounting for 56.43% of the total sample. There were 2205 female-headed households, representing 43.57% of the total sample; within these, 312 de jure female-headed houses accounted for 6.16% of the sample and 14.15% of this group, whereas 1893 de facto female-headed families accounted for 37.4% of the sample as a whole and 85.85% of the female-headed households.

Model Specification and Variable Selection

Model Specification

The measurement model centered on Expected Poverty Vulnerability (VEP) is widely utilized due to its capacity to objectively and comparably quantify the risk of future poverty incidence. It can also adapt to cross-section data, which is useful since it can be difficult to gather multi-year data for micro surveys in rural regions. The VEP approach typically assesses the probability of future household poverty using the three-stage Feasible Generalized Least Squares method (FGLS).

This research employs VEP approach to delve into poverty vulnerability. Fundamentally, VEP aims to predict, leveraging historical data on current income or consumption, the likelihood of future impoverishment at a specific time under the distribution of a particular welfare level (either income or consumption). The following is the fundamental calculation equation:

where \(Vul_{i,t}\) is family i's vulnerability to poverty during the period t, \(Prob( )\) is the probability measurement equation for a future welfare level of an individual or family below the poverty standard, \(C_{i,t + 1}\) is the subject's welfare level during period t + 1, poor is the predetermined poverty line. Generally speaking, the following is a concrete form of the poverty vulnerability measuring equation, assuming that future welfare is distributed lognormally:

where \(\mu_i\) and \(\sigma_i\) stand for the future welfare's expected value and standard deviation, respectively. This is because the error term in welfare equations is often interpreted as representing the effect of risk on the level of welfare (Chaudhuri et al., 2003). Therefore, estimating predicted welfare and standard deviation is essential to determining poverty risk. Consequently, the welfare model (3) is created:

In this case, the explanatory variable influencing welfare is denoted by \(X_{i,t}\), while the residual is denoted by \(e_{i,t}\). The accuracy of measuring poverty vulnerability is directly impacted by future welfare estimation (Yang et al., 2012). Explanatory variables encompass both welfare-affecting variables and individual characteristic variables.

The squared residuals obtained from regression are utilized as the fluctuations in household consumption for further estimation. These fluctuations in consumption stem from various shocks and are contingent upon household characteristic variables. Equation (4) is established to facilitate estimation.

The VEP model states that poverty vulnerability is measured using 3FGLS, and the estimators of \(\beta\) and \(\gamma\) are obtained through the FGLS method. The fitted values from the previous phase of the FGLS estimation process are used to create the heteroscedasticity weights, and \(\widehat{{\beta_{FGLS} }}\) and \(\widehat{{\gamma_{FGLS} }}\) are obtained. The expected value of consumption logarithm \(\hat{E}\) and volatility variance \(\hat{V}\) can be expressed as follows.

Equation (2) is used to quantify poverty vulnerability once the expected value and fluctuation variance of the logarithm of consumption have been estimated. It is assumed that the per capita welfare of rural families follows the lognormal distribution. Setting the poverty line and poverty vulnerability line, as well as choosing the welfare level measurement index, are also essential steps in the process of measuring poverty vulnerability. This study uses consumption as a proxy for rural households' poverty vulnerability. The primary cause is that endogeneity issues could arise due to the income variable's difficulty of control in the model described by the income standard. In the meanwhile, the micro survey's consumption data may more accurately reflect the welfare state of households than the income data, which could contain errors owing to respondent misinterpretation among other factors.

For the poverty line, this study adopts two consumption standards proposed by the World Bank in 2015: US $1.9/day and US $3.1/day per capita consumption. Adjusted with the average exchange rate between US dollars and RMB in 2018, these translate to annual per capita consumptions of 4605 yuan and 7513 yuan as the poverty lines for 2018.

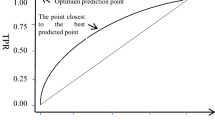

While some studies select 50% as the vulnerability line (i.e., considering probabilities greater than 50% as vulnerable), the measurement of poverty vulnerability based on 3FGLS suits cross-sectional data, and the vulnerability measure is closely associated with the time horizon. In recent years, academia has adopted probability values adjusted for the time horizon as the vulnerability line. A common practice is converting the 50% probability value into a 29% probability of a household falling into poverty within the next two years (Gunther and Harttgen, 2009). This paper also adopts 29% as the vulnerability line, yielding the Variable \(VEP_i\) which indicates whether a family is vulnerable to poverty. For each household, there exist two states: one where poverty vulnerability equals 1 and another where it equals 0.

Further, we proceed by constructing a Probit model to analyze the impact of different household head types and other variables on the probability of household poverty vulnerability. The model's formulation is as follows:

Among them, \(i\) represents different households, \(Pr(VEP_i = 1)\) represents the probability that the household poverty vulnerability is 1, \(VEP_i\) represents the household poverty vulnerability, \(FHH_i^{\prime}\) represents the type of female-headed household, and \(X_i^{\prime}\) represents control variables such as population characteristics, family characteristics and regional characteristics. We selected male-headed households as the reference group.

According to the risk impact theory on poverty, rural households may face various risks, including natural, health, economic, political, and environmental risks. Based on data availability, we choose the self-rated health status from the CFPS database as the health risk experienced by household heads, denoted as \(HEA_i\). Responses range from very healthy to unhealthy, with values assigned from 1 to 5. We define "fair" and "unhealthy" as \(HEA_i = 1\) and the rest as \(HEA_i = 0\). To investigate the impact of gender differences among household heads on the risks faced by households, we construct the following Probit model:

Among them, the explained variable is \(\Pr \left( {HEA_i = 1} \right)\), which represents the probability of the head of a household suffering from health risks.

We create the following regression equation by sampling households \(HEA_i = 1\) in the entire sample in order to further analyze the variations in medical consumption expenditures employed by male-headed and female-headed households to cope with risks after experiencing a health shock:

The dependent variable is the logarithm of the total medical expenditure (\(THE_i\)) for the household. The total medical expenditure refers to the overall healthcare expenses incurred by individuals over the past 12 months.

Variable Selection and Statistical Description

The Explained Variables

The explained variables used in calculating household poverty vulnerability are initially the logarithm of household consumption expenditures. These expenditures encompass nine aspects, including food, clothing, healthcare, transportation, communication, education and culture, entertainment and leisure, housing, and miscellaneous goods and services, constituting the annual expenditure of rural household families. In the model assessing the relationship between household poverty vulnerability and household head gender, the explained variables are \(VEP1_i\) and \(VEP2_i\). Notably, \(VEP2_i\) replaced \(VEP1_i\) as the dependent variable in a robustness check. These variables represent household poverty vulnerability calculated based on the US $1.9 and US $3.1 poverty lines, respectively. In further exploring the influence of gender differences among household heads on the risks faced and coping mechanisms of households, the dependent variables are self-rated health status and the logarithm of total household medical expenditures.

The Control Variables

When calculating poverty vulnerability, the first step involves estimating the consumption equation. Therefore, it's essential to select variables that influence per capita household consumption. The variable selection considers three factors: the correlation between control variables and the explained variable, potential collinearity among control variables, and data availability. Additionally, drawing from Yao's (2022) study, this research has chosen control variables across three dimensions. Firstly, household head characteristics encompass gender, marital status, age, age squared, education, occupation, and due to the significant role of medical expenses in consumption, social security is included as a control variable. Secondly, family dimension variables include family size, family structure, housing ownership, the logarithm of family assets, logarithm of per capita family income, and housing conditions. Lastly, regional dimension variables consist of the logarithm of per capita GDP and whether the region belongs to the eastern region. The setup and assignment of these control variables are outlined in Table 2.

In the model investigating the relationship between household poverty vulnerability and household head gender, the variable regarding possession of medical insurance is excluded due to its non-significant correlation with household poverty vulnerability. However, other control variables are utilized in this context. Conversely, in exploring the relationship between total household medical expenditure and household head gender, both individual health status and possession of medical insurance are included as control variables. This consideration arises from the significant association between medical expenditure and individual health conditions. Furthermore, marital status, serving as the criterion for distinguishing between de jure female-headed households and de facto female-headed households, functions as a grouping criterion in the regression but does not appear as a variable within the regression model. Table 3 provides a statistical description of the explained variables and the control variables for overall households and different gender-headed households.

From Table 3, distinct differences between female-headed and male-headed households are evident. Initially, de facto female-headed households, in contrast to male-headed households, exhibit relatively lower levels of poverty vulnerability. Conversely, de jure female-headed households demonstrate higher vulnerability. Moreover, compared to the overall sample and male-headed households, female-headed households display elevated levels of health risks and total medical expenditures.

In terms of household characteristics, de jure female-headed households typically have smaller family sizes but relatively higher dependency ratios. Conversely, de jure female-headed households exhibit lower household income and assets compared to other household types. In terms of family income and assets, the de facto female-headed households perform better than the de facto female-headed households. Analyzing demographic variables, male-headed households tend to have younger average ages and often possess higher education levels. In contrast, de facto female heads of households often face disadvantages in terms of age and educational level. Finally, with regard to the regional characteristic variables, there are no differences among household types in terms of per capita GDP, but minor distinctions exist in geographical distribution.

Empirical Results

This article uses Stata 17.0 statistical software to perform regression analysis on three models. The regression results of the (7) model is shown in Table 4, the (8) model in Table 5, and the (9) model in Table 6.

Each model undergoes two rounds of regression analysis. The first regression distinguishes between male and female household heads, while the second regression further subdivides the heterogeneity of households headed by females, based on the initial distinction.

Household Head Gender Inequalities and Poverty Vulnerability

Based on Table 4, the following main conclusions can be drawn: The coefficient for female-headed households is negative and not significant, indicating that compared to male-headed households, female-headed households are not more vulnerable. This is inconsistent with expected results but aligns with the conclusions drawn by Fan and Xie (2014). They confirmed that the gender of the household head does not significantly impact poverty. However, male gender does have a significant positive impact on vulnerability. They analyzed that female heads of households might face more uncertainties in production and life than male heads, driven by a sense of "responsibility" to use various means to increase income and reduce vulnerability. Chant (2004) suggests that, due to altruistic tendencies in women and selfish tendencies in men, even though women earn less than men, this deficit can be compensated by women spending more of their income on improving family welfare, thereby reducing family poverty and vulnerability. The coefficient for de jure female-headed households is significantly positive, while for de facto female-headed households, it is significantly negative. This indicates that legal female-headed households are more vulnerable than actual female-headed households, suggesting that marriage is a factor affecting family poverty. Even though both are female-headed households, married female heads can obtain more livelihood capital to resist risks and shocks compared to de jure female heads. This is consistent with Sawhill's (1973) conclusion that unstable marriage is the primary cause of poverty among women.

There is a positive correlation between the age of the household head and poverty vulnerability, and a negative correlation with the square of the head's age, both significant at the 1% level. This suggests that vulnerability to poverty increases with the age of the household head. This aligns with expectations, as advancing age often associates with declining physical capabilities, requiring increased nutritional investment to maintain health. Simultaneously, sensitivity to illnesses heightens, leading to escalated healthcare expenses and an increased risk of falling into poverty. The education level of the household head significantly negatively affects poverty vulnerability. This could be due to China's implementation of compulsory education and other related policies, which have increased the general education level of rural household heads, enhancing their risk awareness and management capabilities, thus effectively reducing family poverty vulnerability. Bai and Li (2010) argue that "education affects vulnerability through its impact on income levels and, compared to other measures to reduce vulnerability, is more fundamental and sustainable."

Family size and dependency ratio are significantly positive at the 1% level, meaning the larger the family size and dependency ratio, the stronger the family's poverty vulnerability. This is especially true for single female-headed households, which lack a partner to support the family, not only missing the income from an adult male but also typically having a higher dependency ratio (Buvinic & Gupta, 1997). Housing ownership is significantly positively correlated with poverty vulnerability. This might be attributed to the predominance of housing ownership households within the sample selection. In rural China, owing to the collective ownership of land, households possess the right to use homesteads granted by the collective but do not hold individual property titles for these lands. Consequently, all rural households have access to and can construct dwellings on their allocated homesteads. However, compared to urban households with property rights certificates issued by housing authorities, rural households' possession of housing doesn't equate to owning substantial or readily monetizable fixed assets.

The assets and income of a family significantly negatively affect its poverty vulnerability, meaning the more assets a family has and the more income it earns (including agricultural and non-agricultural income), the less vulnerable the family is to poverty. The influence of regional economic development levels on household poverty vulnerability appears insignificant. This might stem from the fact that the per capita GDP of each province merely represents the average economic development within that region and fails to capture the wealth disparity within the area. Consequently, its impact on household poverty vulnerability might not be significant. On the other hand, regional distribution demonstrates a negative effect on household poverty vulnerability, significant at the 10% level. This outcome implies a substantial regional heterogeneity in household poverty vulnerability. Given the higher overall industrial development and urbanization levels in the eastern region, alongside elevated levels of social services and household incomes, rural households in the eastern region, compared to those in the central and western regions, seem to face a lower likelihood of falling into poverty vulnerability.

Gender Differences of Household Heads and Family Health Risks, Total Household Medical Expenditure

To further understand the relationship between gender disparities among household heads and family health risks and medical expenditure, we conducted regressions on Eqs. (8) and (9). Firstly, according to Table 5 female-headed households are significantly positive at the 1% level, meaning compared to male-headed households, female-headed households are more likely to face health risks, and female heads are more prone to illness. Additionally, de jure female heads have a higher probability of illness than de facto female heads, possibly due to more stress and anxiety in single and divorced female heads compared to married ones.

Secondly, according to Table 6, in households where the head is ill, the impact of female heads on family medical spending is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that female-headed households spend more on family medical consumption than male-headed households. The coefficients for medical expenditure in de jure female-headed households and de facto female-headed households are significantly positive and pass the 1% level significance test, significantly higher than in male-headed households. Compared to de facto female heads, de jure female heads have a greater impact coefficient on family medical spending. The primary reason lies in the heightened health risks experienced by de jure female household heads. Additionally, other factors might include the presence of male members within de facto female-headed households, leading to joint decision-making regarding significant family expenses and potentially weakening the impact of the household head's gender on household medical expenditure. Further elucidation on other variables is omitted. In essence, this elucidates the vulnerability of de jure female household heads. Their health risks significantly surpass those of male household heads and de facto female-headed households, necessitating increased medical expenditure to address health risks, thereby exacerbating the vulnerability to poverty.

Robustness Checks

To ensure the robustness of the previously examined impact of different household head genders on household poverty vulnerability, this study replaced the dependent variable \(VEP1_i\) used in the previous regression. It employed the second consumption standard proposed by the World Bank in 2015, namely US $3.1/person/day, adjusted by the average 2018 exchange rate to the Chinese Yuan, resulting in an annual per capita consumption of 7513 Yuan as the 2018 poverty line. This calculation generated the new household poverty vulnerability indicator, denoted as \(VEP2_i\). Regression was then conducted on Model (7), and the outcomes are presented in Table 7 below.

The results show that after changing the poverty line, the impact of de jure female-headed households on poverty vulnerability remains significantly positive. The effects of other factors on poverty vulnerability are consistent in direction with the regression results using the first consumption standard poverty line proposed by the World Bank in 2015, and they have passed the significance test. Therefore, the conclusions drawn in the previous text are robust.

Conclusion and Discussion

China has successfully eradicated absolute and widespread regional poverty yet it is now confronted with the burgeoning specter of relative poverty. In this scenario, employing scientific methods to predict household poverty risks and identify those at risk of slipping back into poverty holds crucial significance for ongoing poverty alleviation efforts. Theoretical frameworks highlighting gender disparities in accessing capital and managing risks have yet to be fully corroborated through quantitative empirical evidence within the Chinese context, primarily focusing on qualitative analyses of women's poverty issues. This study adopts a combined qualitative and quantitative approach to comprehensively explore poverty vulnerability and its relation to the gender of the household head. Findings reveal that while there's no significant difference in the probability of poverty vulnerability between female-headed and male-headed households, significant disparities exist within female-headed households. de jure female-headed households are more prone to poverty vulnerability, contrasting with de facto female-headed households displaying lower vulnerability. Health risks impose a disparate burden on female-headed households, especially de jure ones, leading to significantly higher healthcare expenditures compared to male-headed households and the overall sample. These healthcare expenses partly explain the heightened vulnerability of de jure female-headed households to poverty.

Regarding the aforementioned outcomes, contrary to the anticipated theoretical implications, the impact of household head gender on household poverty vulnerability was insignificantly evident. Specifically, female-headed households did not demonstrate a pronounced inclination towards greater or lesser vulnerability to poverty in comparison to their male-headed counterparts. This finding aligns with Mwakalila’s research (2023), indicating a lack of significant disparity in household poverty vulnerability between male and female household heads in rural areas. This outcome may be elucidated by the evolving landscape of Chinese society. The diminishing social exclusion and empowerment of females have accompanied a gradual increase in female access to education and professional opportunities. China stands out globally with a high female labor force participation rate and a reduced gender wage gap. Notably, within rural areas of China, paternal support significantly alleviates time constraints on female labor participation, augmenting their labor supply and wage income, with no significant impact observed for males (Chen et al., 2021). Conversely, males' engagement in the agricultural and industrial sectors contrasts with females' declining involvement in these domains, with an increasing proportion of females contributing to industry and services (World Bank, 2001). During natural disasters and crises, male employment experiences more severe repercussions than female employment, leading to a disproportionate impact on men's wages compared to women's (Behrman & Tinakorn, 1999). Consequently, in rural Chinese households, the gender wage gap has gradually narrowed. This convergence has empowered rural women to better balance familial responsibilities and careers, erasing the historical disadvantage of female-headed households in terms of household income, assets, and property ownership compared to male-headed households.

Remarkably, within female-headed households, de jure female-headed households exhibit a higher susceptibility to poverty vulnerability, while de facto female-headed households notably mitigate the occurrence of household poverty vulnerability. This underlines marriage as a determinant factor influencing household poverty among rural women. Married female-headed households acquire more livelihood capital than de jure female-headed households to withstand risks and adversities, aligning with Sawhill’s assertion (1973) that unstable marriages constitute a primary cause of female impoverishment. This trend arises from rural women's relatively lower income levels and heightened financial reliance on husbands, compounded by increased single-parenting responsibilities following divorce, consequently limiting their work engagement and further impacting economic independence. This is evident in the descriptive statistics where de jure female-headed households display significantly higher dependency ratios but markedly lower household income and assets compared to other groups. Additionally, research (Koball et al., 2010) highlights the link between marriage and mental health outcomes, indicating a more pronounced increase in depressive symptoms among women post-divorce compared to men, and singles potentially exhibiting behaviors associated with adverse health outcomes. This could explain the higher health risks among de jure female heads of household observed in this study compared to de facto female heads of household. Consequently, to cope with these risks, de jure female-headed households incur higher total healthcare expenditures, further exacerbating their vulnerability to poverty.

The observed heterogeneity among female-headed households elucidates a counteracting effect between the probabilities of poverty vulnerability occurrence for de jure and de facto female-headed households. This dynamic, to a certain extent, contributes to the understanding of why the disparity in poverty vulnerability between the overall sample of female-headed households and the male-headed households sample lacks statistical significance.

This study holds significant theoretical implications in researching the vulnerability to poverty within Chinese rural households and the poverty experienced by women. Firstly, leveraging a higher-quality dataset from the CFPS, this research rigorously quantifies poverty vulnerability in Chinese rural households by constructing the Vulnerability to Poverty model and employing the three-stage feasible generalized least squares method. Subsequently, regression and robustness analyses utilizing the Probit model examine the relationship between the gender of rural household heads and household poverty vulnerability, thereby ensuring the persuasiveness and credibility of the research findings. Secondly, this study unveils the multidimensional relationship between the gender of household heads and the economic status of households in rural China. In contrast to previous theoretical perspectives highlighting female disadvantage, this research underscores instances where female-headed rural households do not exhibit inferiority in aspects such as household income and assets, diverging from prior expectations. This reevaluation of gender-based economic status contributes to understanding the role of rural Chinese women in household poverty vulnerability, providing novel theoretical insights into the association between gender and vulnerability to poverty. Thirdly, by delving into health risk shocks and increased healthcare expenditures as contributing factors, this study expands the potential determinants of poverty vulnerability among rural women. This expansion contributes valuable theoretical and empirical references for subsequent research endeavors on this topic.

The conclusions drawn from this study have significant implications for the development of more efficacious pro-poor policies. Firstly, the findings underscore the imperative consideration of gender discrepancies' impact on vulnerability to poverty when designing and executing poverty alleviation strategies. Enhancing the economic standing of women further emerges as a pivotal prerequisite for mitigating rural female poverty in China. Policies ought to be devised to bolster women's economic empowerment, facilitate vocational training, and entrepreneurial support, and foster labor market inclusion, thereby bolstering their economic status and curtailing poverty risk (Halim et al., 2023). Secondly, broadening women's asset accessibility through microcredit initiatives and tailored savings plans can fortify income streams while adopting insurance to curtail household risk exposure. Thirdly, given women's amplified health risks, ensuring their access to quality education and healthcare is paramount. Specific measures such as equalizing educational opportunities, advocating gender-based education, augmenting women's participation in medical insurance, and providing accessible healthcare services are instrumental in elevating women's living standards and fortifying their resilience against poverty. Fourthly, contextualizing Chinese societal norms, diligent attention must be directed toward the role of community and grassroots organizations in mitigating the risks associated with female poverty. This involves executing community projects, dispensing social support, and advocating legal education on rural women's property rights to bolster their stature within families and society. Concurrently, establishing a social security framework for children from single-mother households ensures their uninterrupted education and breaks the cycle of poverty transmission. Lastly, establishing a comprehensive scheme for major risk assistance and poverty alleviation subsidies, tailored to varying family structures and economic standings, ensures the effectiveness of the aid measures.

While this study delves into the vulnerability of female-headed households to poverty, it contends with several limitations. Primarily, there are data and definitional constraints concerning the understanding of female-headed households and associated female poverty (Bradshaw et al., 2018). The female population is diverse, and female household heads cannot be a "proxy" for all women. Moreover, the method of measuring poverty vulnerability at the household level used in this study assumes that household income or consumption is evenly distributed among household members, overlooking gender disparities in power dynamics and resource allocation within households. In fact, many studies have shown that some households defined as non-poor based on per capita income or consumption measurement may still have certain members, particularly women and children, facing severe poverty issues (Folbre, 1994; Robeyns, 2008). Therefore, solely comparing the impact of household head gender on household poverty incidence overlooks gender inequalities within households. Secondly, despite the robust sampling methodology and high-quality samples from the CFPS database, this study included a limited sample size of de jure female heads of households since the distribution of different sample types within the total sample presents a big gap. Also, household vulnerability to poverty might fluctuate over time. Relying solely on 2018 data fails to capture long-term trends and dynamic changes, particularly those influenced by economic cycles or specific events like natural disasters or policy shifts. Consequently, the conclusions may inadequately represent enduring or prolonged trends. Lastly, the results derived from the Probit model regression in this study primarily showcase correlations between independent and dependent variables. Inadequate consideration of causal identification and endogeneity issues is also a drawback of this research.

Therefore, future research directions could be considered from three perspectives. Firstly, there's a need to redefine and comprehend female poverty in terms of data and methodologies. This involves incorporating the disparities in rights and resource allocation among women within households. An individual-based model for measuring poverty vulnerability should be constructed, with both male and female individuals in the analysis sample. Multi-dimensional indicators can be utilized, expanding beyond income and consumption methods to include social indicators such as mortality rates, health and nutrition, time distribution, and methods aimed at assessing personal capability factors like access to resources and educational levels. This approach could unveil the true causes and mechanisms behind the "feminization" of poverty, shedding light on the underlying factors influencing it. Secondly, poverty vulnerability entails predicting the risk of poverty in advance, which should encompass not only the risk itself but also the coping mechanisms. It should reflect the results of the "shock response" to risks (Yao & Xie, 2022). Risk encompasses various factors such as disasters, market fluctuations, education, employment, and caregiving. Present studies primarily focus on health risks. Future research could adopt a disaster sociology risk "shock-response" analytical framework to comprehensively interpret the essence and genesis of poverty vulnerability. This includes refining models to measure poverty vulnerability and exploring poverty vulnerability from long-term and dynamic perspectives, capturing evolving trends and patterns over time. Lastly, future considerations might involve the combined use of Propensity Score Matching (PSM) and Difference-in-Differences (DID) methods. This combined approach (PSM-DID) could better address potential self-selection biases within this study, yielding more instructive causal relationship conclusions regarding female poverty vulnerability.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed for this study can be found in the CFPS repository. Please see http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/ for more details, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Hu Chunhua: Accurately identify and implement precise measures to meticulously execute the poverty alleviation campaign. http://cpc.people.com.cn/n1/2016/0921/c64094-28730820.html?_k=a2n0k2.

Liu Yongfu: The State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development will implement a series of action plans to win the battle against poverty. https://nrra.gov.cn/art/2015/12/11/art_624_42586.html.

The National Rural Revitalization Administration (formerly known as the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development) of China will implement ten precise poverty alleviation projects. https://nrra.gov.cn/art/2014/12/25/art_624_13260.html

Xi Jinping: Speech at the symposium on securing a decisive victory in the fight against poverty. https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-03/06/content_5488175.html

References

Addai, K. N., Ngombe, J. N., & Temoso, O. (2022). Food poverty, vulnerability, and food consumption inequality among smallholder households in Ghana: A gender-based perspective. Social Indicators Research, 163, 661–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02913-w

Arden, F., & Murray, L. (2017). The dynamics of poverty in South Africa. Version 3. Cape Town: SALDRU, UCT. (SALDRU Working Paper Number 174/ NIDS Discussion Paper 2016/1). https://www.opensaldru.uct.ac.za/handle/11090/824

Bartfeld, J., Gundersen, C., Smeeding, T. M., Ziliak, J. P., & Cafer, A. (2015). SNAP Matters: How Food Stamps Affect Health and Well-Being. Stanford University Press. http://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=24621

Behrman, J. R., & Tinakorn, P. (2000). The surprisingly limited impact of the Thai crisis on labor, including on many allegedly "more vulnerable" workers.

Bradshaw, S., Chant, S., & Linneker, B. (2018). Challenges and changes in gendered poverty: the feminization, de-feminization, and re-feminization of poverty in Latin America. Feminist Economics. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2018.152941

Brady, D., & Kall, D. (2008). Nearly universal, but somewhat distinct: The feminization of poverty in affluent Western democracies, 1969–2000. Social Science Research, 37(3), 976–1007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.07.001

Burda, M., Hamermesh, D.S., & Weil, P. (2007). Total Work, Gender and Social Norms. Labor: Demographics & Economics of the Family. Working Paper 13000, National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/W13000

Buvinić, M., & Gupta, G. R. (1997). Female-headed households and female-maintained families: Are they worth targeting to reduce poverty in developing countries? Economic Development and Cultural Change, 45(2), 259–280.

Calvo, C., & Dercon, S. (2007). Vulnerability to poverty. Working Paper Series, CSAE WPS/2007-03. https://ora4-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:9922cd6f-3d11-44ee-832c-d48141a33cce/files/m12725f61ae12be984784aa3ae5d58e27

Chakravarty, S. R. (2018). Analyzing multidimensional well-being: A quantitative approach (1st ed.). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119257424

Chant, S. (2004). Dangerous equations? How female-headed households became the poorest of the poor: Causes, consequences and cautions. IDS Bulletin, 35, 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2004.tb00151.x

Chant, S. (2006). Re-thinking the “Feminization of Poverty” in Relation to Aggregate Gender Indices. Journal of Human Development, 7, 201–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649880600768538

Chaudhuri, S. (2003). Assessing vulnerability to poverty: concepts, empirical methods and illustrative examples. Department of Economics Columbia University. http://econdse.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/vulnerability-assessment.pdf

Chaudhuri, S., Jalan, J., & Suryahadi, A. (2002). Assessing household vulnerability to poverty from cross-sectional data: a methodology and estimates from Indonesia. Department of Economics Discussion Papers, 0102-52, Columbia University https://doi.org/10.7916/D85149GF

Chen, K., Zhang, Z., & Xu, Z. (2021). Intergenerational support, female labor supply and the convergence of gender wage gap in China: Based on the perspective of gender division of labor. Journal of Finance and Economics, 47(04), 124–138. https://doi.org/10.16538/j.cnki.jfe.20200918.401

Chen, L., & Standing, H. (2007). Gender equity in transitional China’s healthcare policy reforms. Feminist Economics, 13(3–4), 189–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545700701439473

Chen, Y., & He, Y. (2014). Research on poverty dynamics and influencing factors: Evidence from female household heads in China. Hubei Social Science, 4, 61–66. https://doi.org/10.13660/j.cnki.42-1112/c.012592

Christiaensen, L. J., & Subbarao, K. (2005). Towards an understanding of household vulnerability in rural Kenya. Journal of African Economies, 14(4), 520–558. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/eji008

Davids, T. & Driel, F. (2010). Globalization and the need for a 'Gender Lens': A discussion of dichotomies and orthodoxies with particular reference to the 'Feminization of Poverty'. Developmental Psychology.

Dercon, S., & Krishnan, P. (2000). Vulnerability, seasonality and poverty in Ethiopia. Journal of Development Studies, 36(6), 25–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380008422653

Ding, J., Zhang, B., & Kang, Z. (2023). Can Medical Insurance Alleviate the Poverty Vulnerability of Rural Residents?—From the Perspective of the Income and Expenditure Effect of the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme. Nankai Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.14116/j.nkes.2023.07.003

Dong, Q., Li, X., Yang, H., & Zhang, K. (2007). Gender inequality and poverty in the field of rural education. Social Science, 1, 140–146.

Fan, L., & Xie, E. (2014). Does public transfer payment reduce poverty vulnerability? Economic Research Journal, 8, 67–78.

Floro, M. S. & Bronfman, J. (2012). How well have social protection schemes in Chile reduced household vulnerability? (Working Papers 2012-03). American University, Department of Economics. https://doi.org/10.17606/58rs-g641

Folbre, N. (1994). Who Pays for the Kids?: Gender and the Structures of Constraint (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203168295

Gao, S., Shi, C., & Tang, J. (2020). Study on the alleviation of rural household poverty vulnerability based on the perspective of empowerment: A case study of severely impoverished areas in the Taihang Mountains. China Rural Observation, 1, 61–75.

Gao, L. (2016). Analysis of the factors leading to poverty in female-headed households and countermeasures Master's thesis, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=AnuRcxOpZiFWCzpAFClWk3qIqti86xioO-L3nhNnInpcdu8ETc3aa1JonQZA-ScMeAqOyhFGEKRpCgdTmweGkuQ7rY9HsAMKpdXMEF3NoleZ6cF7-K60qG5KGqzBpOxqKTbbOp__bBc=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS

Global Gender Gap Report. (2021). Available on: https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2021

Günther, I., & Harttgen, K. (2009). Estimating households vulnerability to idiosyncratic and covariate shocks: A novel method applied in Madagascar. World Development, 37(7), 1222–1234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.006

Halim, D., O’ Sullivan, M., & Sahay, A. (2023). Increasing Female Labor Force Participation. World Bank Group Gender Thematic Policy Notes Series; Evidence and Practice Note. World Bank, Washington, DC. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/39435

Hoddinott, J. F. & Quisumbing, A. R. (2003). Data sources for micro econometric risk and vulnerability assessments (Social Protection discussion paper series No. SP 0323). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. http://www-wds.worldbank.org/servlet/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2004/06/02/000011823_20040602123921/Rendered/PDF/29137.pdf

Hohberg, M., Landau, K., Kneib, T., Klasen, S., & Zucchini, W. (2018). Vulnerability to poverty revisited: Flexible modeling and better predictive performance. The Journal of Economic Inequality., 16, 439–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-017-9374-6

Ichwara, J. M., Kiriti-Nganga, T. W., & Wambugu, A. (2023). Changes in gender differences in household poverty in Kenya. Cogent Economics & Finance. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2191455

Jiang, L. (2017). New progress in poverty vulnerability theory and policy research. Economic Dynamics, 6(13), 96–108.

Jin, Y. (2011). The fluid patriarchy: Changes in the families of migrant farmers. Social Sciences in China, 01, 26–43.

Kim, Y. (2016). Mobile phone for empowerment? Global nannies in Paris. Media, Culture & Society, 38(4), 525–539. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443715613638

King, E. & Lomborg, B. (2008). Women and development. Project Syndicate.

Klasen, S., Lechtenfeld, T., & Povel, F. (2015). A feminization of vulnerability? Female headship, poverty, and vulnerability in Thailand and Vietnam. World Development, 71, 36–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.11.003

Klasen, S., & Waibel, H. (2013). Introduction and key messages. In S. Klasen & H. Waibel (Eds.), Vulnerability to poverty: Theory, measurement and determinants (pp. 1–14). Palgrave-Macmillan.

Klasen, S., & Waibel, H. (2015). Vulnerability to poverty in south-East Asia: Drivers, measurement, responses, and policy issues. World Development, 71, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.007

Koball, H. L., Moiduddin, E., Henderson, J., Goesling, B., & Besculides, M. (2010). What do we know about the link between marriage and health? Journal of Family Issues, 31(8), 1019–1040. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x10365834

Koomson, I., Villano, R. A., & Hadley, D. (2020). Effect of financial inclusion on poverty and vulnerability to poverty: Evidence using a multidimensional measure of financial inclusion. Social Indicators Research, 149(3), 613–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02263-0

Kurosaki, T. (2010). Targeting the vulnerable and the choice of vulnerability measures: Review and application to Pakistan. The Pakistan Development Review, 49(2), 87–103.

Lan, F., Ma, J., & Huang, X. (2023). The cost of childbirth for women from the perspective of multidimensional relative poverty: Empirical evidence from CFPS data. Population and Development, 29(05), 12–26.

Ligon, E., & Schechter, L. (2003). Measuring vulnerability. The Economic Journal, 113(486), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00117

Li, L., & Bai, X. (2010). Measurement and decomposition of household poverty vulnerability in urban and rural areas in China—An empirical study based on CHNS micro data. Quantitative Economics Technical Economics Research, 27(08), 61–73. https://doi.org/10.13653/j.cnki.jqte.2010.08.002

Li, Q. (2010). Capability approach: Poverty and anti-poverty of rural women – An empirical study based on C Township of Guangshui City. Contemporary Economic Management, 32(01), 63–66. https://doi.org/10.13253/j.cnki.ddjjgl.2010.01.001

Li, Z., Yuan, Y., Liang, L., & Niu, T. (2020). Progress and enlightenment of foreign research on female poverty: Based on studies in the field of geography. Human Geography, 35(01), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.13959/j.issn.1003-2398.2020.01.003

Lin, Z. (2005). Chinese women and the retrospect and prospect of anti-poverty. Collection of Women’s Studies, 04, 37–41.

Liu, J., & Liu, M. (2018). Analysis of the current situation of female poverty in poor areas: A gender comparison from the perspective of multidimensional poverty. Soft Science, 32(09), 43–46. https://doi.org/10.13956/j.ss.1001-8409.2018.09.10

Marcoux, A. (1998). The feminization of poverty: claims, facts, and data needs. Population and Development Review, 24(1), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.2307/2808125

Mba, P. N., Nwosu, E. O., & Orji, A. (2018). An empirical analysis of vulnerability to poverty in Nigeria: Do household and regional characteristics matter? International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 8(4), 271–276.

Medeiros, M., & Costa, J. (2008). Is there a feminization of poverty in Latin America? World Development, 36(1), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.02.011

Moghadam, V. (1998). The feminization of poverty in international perspective. The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 5(2), 225–249.

Moore, H. (1994). Is There a Crisis in the Family? UNRISD Occasional Paper: World Summit for Social Development, No. 3, United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD), Geneva. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/148807/1/862975204.pdf

Mwakalila, E. (2023). Vulnerability of poverty between male and female headed household in Tanzania. Journal of Family Issues, 44(10), 2730–2745. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X221106740

Naudé, W., Santos-Paulino, A. U., & McGillivray, M. (2009). Measuring vulnerability: An overview and introduction. Oxford Development Studies, 37(3), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600810903085792

Pearce, D. (1978). The Feminization of Poverty: Women, Work, and Welfare. Urban and Social Change Review, 11, 28–36.

Peterson, J. (1987). The Feminization of Poverty. Journal of Economic Issues, 21(1), 329–337.

Ramírez, E., & Ruben, R. (2015). Gender systems and women’s labor force participation in the salmon industry in Chiloé, Chile. World Development, 73, 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.11.003

Robeyns, I. (2008). Sen’s capability approach and feminist concerns. In F. Comim, M. Qizilbash, & S. Alkire (Eds.), The capability approach: concepts, measures and applications (pp. 82–104). Cambridge University Press.

Sawhill, I. V. (1973). The economics of discrimination against women: Some new findings. The Journal of Human Resources, 8(3), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/144710