Abstract

Individuals’ subjective well-being is influenced by their financial well-being, family relationship quality, spiritual well-being, gender, and age. However, our knowledge of potential associations between these factors is limited, especially in non-western developing countries. Further, human thinking’s complexity, interconnectedness, and asymmetry fit nicely with subjective well-being conceptualizations. Therefore, this research is one of the very first studies from a typical Asian country that conceptualizes subjective well-being asymmetrically. The primary objective of this study was to determine which combinations of these factors resulted in higher or lower subjective well-being. We used a self-administered questionnaire to survey 250 married working people in Bangladesh’s capital city. The factor combinations are identified with a fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). Despite not finding any necessary condition for high or low subjective well-being, the analysis identifies two equifinal combinations of high subjective well-being and four combinations of low subjective well-being. In Asian cultures, where family bonds and spiritual well-being are feared to be declining, the combination of identified configurations re-emphasizes the importance of family relationship quality and spiritual well-being. Using a configurational approach, the findings contribute to the literature on subjective well-being and family relationships by explaining how different combinations of factors determine an individual's well-being. Additionally, this has important implications for policymakers and society as a whole.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A happier society aspires to have healthier, more educated, more reliable, safe, and well-governed citizens (Lambert D’raven & Pasha-Zaidi, 2016). It has been shown that individuals with greater well-being earn more money, exhibit more compassion and cooperate, volunteer more often, and donate more money and time than those with lower levels of well-being (Lambert et al., 2019). In addition, happier citizens are more likely to wear seatbelts, are less likely to be involved in vehicular accidents, are more physically active, and are more productive, satisfied, and committed to their careers (Goudie et al., 2014; Huang & Humphreys, 2012; Lambert et al., 2019). So, throughout human history, philosophers and economists have incorporated the pursuit of happiness into their work, from Aristotle to Bentham to Mill and Smith. This effort has continued, especially in recent decades when scholarly research on happiness greatly increased (Gonza & Burger, 2017; Singh et al., 2023). As a result of the multiple cultural meanings attached to the concept of happiness, Singh et al. (2023) describe happiness as “a harmonious state of fulfilled physiological and psychological needs in the past, present and future, which results in a meaningful and content life (p. 29).”

However, happiness is affected by a variety of factors. As outlined in the widely accepted PERMA (pleasure, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment) model (Seligman, 2018). The PERMA model is composed of five essential elements: (i) Pleasure, highlighting the experience of joy and contentment; (ii) Engagement, which entails intense participation in stimulating and gratifying tasks; (iii) Relationships, underscoring the significance of robust and nurturing social bonds; (iv) Meaning, focused on leading a life with purpose and making contributions beyond oneself; and (v) Accomplishment, which is about setting and fulfilling personal objectives to achieve a sense of expertise and achievement. Together, these components of the model play a vital role in enhancing an individual's overall sense of well-being and happiness (Lambert D’raven & Pasha-Zaidi, 2016; Seligman, 2018). A dearth of empirical evidence exists in the literature about how the PERMA model is experienced by other cultures (Lambert D'raven & Pasha-Zaidi, 2016). Based on the PERMA model and the pertaining literature—financial well-being, family relationship quality and spiritual well-being are the constituents of subjective well-being (Grevenstein et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2023; Thomas et al., 2017). For example, Grevenstein et al. (2019) found that better family relationships are associated with higher well-being because they provide the social context for developing a healthy personality and foster social competence and adjustment. Singh et al. (2023) found that family relationships are positively correlated with happiness and that practicing religious and spiritual beliefs helps participants find meaning in the present and make peace with the past. Apart from culture, socio-demographics and economic variables play a key role in regulating happiness (Singh et al., 2023).

There persists some contending findings and significant gaps in the literature. The first is related to the findings of Muresan et al. (2020), who found that culture plays an essential role in the perception of happiness. In general, culture is believed to impact an individual's understanding of happiness, the methods by which they seek it, and the ways in which they express it. It molds personal values, influences social interactions, informs coping strategies, and guides life decisions. All these aspects are crucial to forming an individual's sense of well-being and contentment. However, most of the family and subjective well-being literature is grounded on data collected from industrialized developed and Western cultures (Dobrowolska et al., 2020; Shek, 2005; Singh et al., 2023). The concept of subjective well-being and the conditions that facilitate or restrict subjective well-being in other parts of the world are poorly understood. Although little empirical evidence is available in collectivist Asian countries, Asians place a high value on family and may perceive healthy family qualities differently, so it would be interesting to study whether family relationship quality is a contributing cause of subjective well-being in the Asian context (Shek, 2005). Additionally, recent research indicates that Western and Eastern cultures prioritize different sources of well-being differently (Singh et al., 2023).

Hence, this study is a response to literature (e.g., Ngamaba et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2017) advocating more research on diverse families especially from a rarely studied cultural context. Second, in different studies (D’Ambrosio et al., 2020; Iannello et al., 2021; Mathew et al., 2024; Ramos et al., 2022; Sharif Nia et al., 2021), financial well-being, spiritual well-being, and family relationship quality have been identified as determinants of subjective well-being. However, the presence of these three factors as determinants of subjective well-being in a single study is relatively limited, and the attempt to show subjective well-being as a result of their mutual interaction is a novelty of this study. Third, earlier research on subjective well-being has established a positive association among its various components, suggesting well-being is interconnected (Höltge et al., 2023). For the assessment of subjective well-being, most studies currently available used either qualitative (like grounded theory and case studies) or regression-based models. These models often include methods like structural equation modeling (SEM), ordinary least squares (OLS), or ordered probit regression (Lakshmanasamy, 2022). However, Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA), grounded in Boolean algebra and set theory, aligns with John Stuart Mill's causality principles (Mello, 2021; Mill, 1843). QCA, differing from linear regression analysis, addresses the complex, non-linear aspects of social phenomena through its emphasis on conjunctional causation (i.e., combinations of conditions), equifinality (i.e., multiple pathways), and causal asymmetry (i.e., outcomes and non-outcomes may need different explanations) (Mello, 2021; Pappas & Woodside, 2021; Ragin, 2014; Rihoux & Ragin, 2008; Woodside, 2014). This makes QCA a more effective tool for understanding the multifaceted nature of subjective well-being, as it better navigates social science research's diverse and non-linear characteristics (Fiss, 2011; Mill, 1843; Ragin, 2014). Fourth, gender and age differences in the research model demonstrate its additional originality which seldom used as a prime cause. Botha et al. (2019) critiqued the predominant focus of current research on objective indicators (like age, race, and socioeconomic status) for conceptualizing well-being, arguing for greater attention to subjective indicators such as individual emotions, attitudes, and perceptions. Additionally, they stressed the need to examine well-being within a socio-cultural context. This research took into consideration both subjective and objective measures of wellbeing. Further, the QCA method used in this research conceptualizes high and low occurrences of outcome variables, aligning with Mill's (John Stuart Mill) concept of higher and lower pleasures (Roig-Tierno et al., 2017).

To address the aforementioned gaps in the literature, this research adopts the configurational theory (Ragin, 2014; Rihoux & Ragin, 2008) and conceptualizes subjective well-being is an outcome five inter-related yet distinct causal conditions (financial wellbeing, relationship quality, spiritual wellbeing, age and gender). This research also intends to find out—(i) the necessary conditions related to high and low subjective well-being and (ii) the combinations of sufficient conditions (configurations) that may cause again high and low subjective wellbeing of Bangladeshis.

This research has made several contributions. We are seeing a decline in happiness in recent years. This trend is particularly pronounced in developing nations, where individuals are burdened by factors like fierce competition, persistent hardships, and an excessive emphasis on acquiring material wealth (Clark & Senik-Leygonie, 2014; Helliwell et al., 2019). Additionally, this research attempted to understand subjective well-being, family relationships, and spirituality at a time when family ties are believed to be loosening (Poushter et al., 2019), and spirituality-related thinking is widely believed to be diminishing in general and even in traditional collectivist cultures (Lingier & Vandewiele, 2021). Further, this study is the first of its kind to use configurational theory to examine subjective well-being. As a result, happiness research and theory will be further developed by identifying necessary and sufficient conditions. The data of this research are derived from a cultural context that has not been extensively studied. As a result, cultures that share similarities and developing countries might find these results beneficial.

This paper is organized as follows. Next, it presents an overview of the conceptual model, including the reasoning behind the adoption of QCA approach. In section “Methodology”, the research methodology approach is presented. In the fourth section, it reports and discuss the findings from a survey exploring the necessary and sufficient conditions of subjective well-being. Finally, implications, limitations, and future research directions are provided.

Literature Review

Subjective Wellbeing

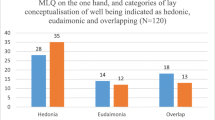

The terms subjective well-being, life satisfaction, psychological well-being, and happiness have become interchangeable in research, policy, and practice (Jones, 2023; Rizvi & Hossain, 2017). Diener (2006) defined subjective well-being as “an umbrella term for the different valuations people make regarding their lives, the events happening to them, their bodies and minds, and the circumstances in which they live’’ (p. 400). A multifaceted and holistic conceptualization of well-being includes subjective, social, and psychological well-beings (Botha et al., 2019). Following the ancient Greek and European philosophical orientations, hedonic and eudaimonic concepts are considered an integral part of understanding psychological well-being (Botha et al., 2019; Rahmani et al., 2023; Singh et al., 2023). The hedonistic approach emphasizes pleasure, and promotes happiness as subjective wellbeing, characterized by a desire for pleasure and enjoyment; the eudaimonic approach emphasizes living a purposeful life and optimal functioning of individuals and aligns itself with the research on subjective well-being (Botha et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2023). In utilitarian philosophy, happiness is defined as a discrete and subjective state of well-being. “Eudemonic” is a concept derived from Aristotle and his ideas on how one can lead a well-lived life. As Amartya Sen explains (Gonza & Burger, 2017), well-being is the ability to be and do as well as the ability to advance and fulfill personal goals. Researchers are now considering wellbeing as a multidimensional construct that includes both hedonic and eudemonic components (Botha et al., 2019; Gonza & Burger, 2017; Singh et al., 2023).

Keyes (2002) defines well-being as a combination of psychological, emotional, and social components. Positive affect, low negative affect, and life satisfaction are all indicators of emotional well-being. Psychological well-being involves having positive attitudes about oneself, being independent, believing that one is developing, interacting with others in a trustfully, and experiencing meaning in life. Social well-being is characterized by group potential and a sense of security (Botha et al., 2019). Research on subjective well-being suggests that meaning, emotions, enjoyment, and positive relationships as key indicators (Botha et al., 2019). Diener and Tov (2011) also emphasize the importance of social connections and personal significance in gauging well-being. From the perspective of hedonism, happiness is about maximizing satisfaction and minimizing pain. This view aligns with economic theories that consider happiness as a crucial measure of well-being, rooted in subjective evaluations. Lakshmanasamy (2022) argues that subjective well-being, reflecting individuals' internal utility, serves as a reliable and valid measure of quality of life.

A person's subjective well-being is inherently multidimensional, and it is influenced by their thoughts and feelings. Subjective well-being may be considered a higher-order concept, but determinants may not be equally predictive across dimensions. While there is less agreement regarding which factors should be considered when evaluating subjective wellbeing, we can generally categorize subjective wellbeing into three categories: life evaluations, affective measures, and eudaimonia (Gonza & Burger, 2017). Well-being traditionally encompasses both objective conditions and subjective processes, including affect and cognitive evaluations of life satisfaction (Gonza & Burger, 2017). Lakshmanasamy (2022) notes a distinction between psychology's focus on subjective assessments of happiness and economics' reliance on empirical data and objective indicators. Psychology associates happiness with hedonism, the pursuit of pleasure and avoidance of pain, while economics interprets it through utilitarianism, equating happiness with the utility derived from actions. There is a consensus among scholars that subjective well-being, based on personal happiness and life satisfaction judgments, is a valid measure of internal utility and broadly represents overall utility.

Financial Wellbeing

Over the past decade, researchers across various social science disciplines (e.g., economics, psychology, sociology, marketing, financial counseling, and consumer finance) have shown an increased interest in financial wellbeing (Bashir & Qureshi, 2023; Brüggen et al., 2017; Mahendru et al., 2022a, 2022b; Mahendru et al., 2022a, 2022b). Several terms in the literature convey related meaning of financial wellbeing, including economic wellbeing, perceived financial wellbeing, and financial wellness (Mahendru et al., 2022a, 2022b). Fan and Henager (2022) asserts that financial satisfaction and financial well-being are distinct by articulating financial satisfaction as a sub-dimension and a positive indicator of financial wellbeing. There are two traditions of conceptualizing financial wellbeing as subjective and objective orientations. Though, most scholars prefer a more subjective conceptualization and less objectivity in the concept. One plausible explanation for prioritizing subjective conceptualization is—‘people in similar financial situations, as defined by objective measures such as assets or income, could perceive their financial wellbeing differently” (Brüggen et al., 2017, p. 229).

In the contemporary literature, financial wellbeing is portrayed as a state of present and future financial security and is linked with promoting sustainable development (Bashir & Qureshi, 2023). Netemeyer et al. (2018) described it as a sense of security in the future with proper money management in the present. It is proposed to be the ultimate measure to evaluate one’s financial health (Barrafrem et al., 2020). Vlaev and Elliott (2014) conceptualize financial well-being as a feeling of financial adequacy and safety in the present and future, modeled through personal perspectives, the absence of which causes stress. Most of the pertaining research agrees that financial knowledge, psychosocial factors and financial behavior are the main contributing factors in the process of enhancing one's financial well-being (Mahendru et al., 2022a, 2022b). However, financial wellbeing is a contextual construct as well, depending significantly on the demographics and individual differences (Riyazahmed, 2021).

Financial wellbeing employs a subjective conceptualization (Barrafrem et al., 2020) and is a multidimensional concept (Bashir & Qureshi, 2023; Singh & Malik, 2022). Encompassing four-dimensions: (i) control of current finances, (ii) ability to absorb financial shocks, (iii) ability to meet financial goals and (iv) financial freedom to live and enjoy life (Singh & Malik, 2022). Though external factors beyond the person’s control may affect financial wellbeing, it indicates how individuals, given the current financial circumstances, can make the best out of the situation (Barrafrem et al., 2020). Psychological and attitudinal traits are important determinants in understanding personal financial behavior (Mahendru et al., 2022a, 2022b; Mathew et al., 2024); as individual psychological characteristics and attitudes toward money significantly influence how people manage their finances. Recognizing and comprehending these traits can substantially improve the effectiveness of personal financial planning and decision-making processes.

The literature on whether income buys happiness is vast and inconclusive, where many studies have confirmed that more wealth does not necessarily increase human happiness (Aydin, 2017; Muresan et al., 2020). However, others contend those views by stylizing facts that have been identified: income is associated with happiness, income changes correlate with happiness, and income moves with happiness (Gonza & Burger, 2017). Based on Clark and Senik-Leygonie (2014), income influences a person's subjective well-being, as does the income of their neighbors. An individual's economic well-being is determined by their economic outcome, financial status, and future choices. The ability to meet basic needs, maintain routine financial control, and maintain enough income throughout life is considered economic well-being (Jain et al., 2019).

As the research on financial wellbeing is an early stage (Brüggen et al., 2017), an unanimously accepted theorization of financial-wellbeing is yet to develop (Mahendru et al., 2022a, 2022b). Because of various socio-economic reasons such as decreased saving rates, low base interest rates, rising student debt (mainly for Generation Y and millennials), and higher spending for retirements lead to the demand for studying financial well-being in industrialized and developed countries (Brüggen et al., 2017). However, the question remains whether it is essential to study financial well-being in the context of developing countries. Those developing countries are characterized by high economic inequality, a rising middle class, and high inflation; as such, it presumes that it is high time to explore the nature and dynamics of financial well-being in developing countries.

Family Relationship Quality

Family is a social system that shapes an individual's life experience through socialization and gene-environment interactions and influences personality development from early childhood onwards (Grevenstein et al., 2019). The ability to talk to family or peers, and the opportunity to confide in them, translate into happiness (Singh et al., 2023). There is a positive link between marriage and subjective well-being as family functions and care improve one's life satisfaction and well-being (Jain et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2017; Verbakel, 2012). Researchers have found that married individuals are the most well-adjusted across the lifespan (Verbakel, 2012) and families play an integral role in well-being throughout the lifespan, providing individuals with resources such as meaning and purpose, as well as social and tangible resources (Thomas et al., 2017).

Quality marital relationships are important because they define the context of an individual's life, affect their well-being throughout adulthood, and are comparable to unhealthy lifestyle choices like smoking. According to Thomas et al. (2017), marital relationships are explained by the marital resource and stress models. Based on the marital resource model, marriage can promote well-being by increasing economic, social, and health-promoting opportunities. The stress model, however, suggests that negative aspects of marriage, such as marital strain and marital dissolution, can lead to stress and derail well-being (Thomas et al., 2017).

Spiritual Wellbeing

Moral behavior is based on a foundation of spirituality, and there are many definitions of spirituality, and its meaning remains elusive despite the fact that the majority of definitions emphasize meaning, purpose, and connection (Koburtay et al., 2023; Sulphey, 2020). Having a sense of spiritual wellbeing can foster emotional relief, meaning-making, and resilience (Chakradhar et al., 2022). Chowdhury and Fernando (2013) define spirituality as feeling connected to oneself, others, and the universe. Spirituality in a person's life manifests as spiritual well-being, which is the outcome of experiencing spirituality (Chowdhury & Fernando, 2013). A low but consistent correlation exists between religiosity and happiness (Gonza & Burger, 2017), with faith in a transcendent order associated with subjective wellbeing. According to Gomez and Fisher (2003), spiritual well-being can be divided into four categories: personal well-being, communal well-being, transcendental well-being, and environmental well-being. It has been shown that prayer can improve mental and physical health when used to deal with stressful situations and negative life issues (Simão et al., 2016). Most people rely on religious beliefs to regulate their emotions and generate happiness in their daily lives (Rizvi & Hossain, 2017; Vishkin et al., 2014). Several studies have suggested that religion can also be substituted for higher income to achieve happiness (Rizvi & Hossain, 2017). Even though spirituality and religion are generally viewed as declining in society, the significance of spirituality and religion remains crucial (Rizvi & Hossain, 2017).

Literature debates how to differentiate between religiosity and spirituality. Previously, studies have demonstrated that spirituality and religion are quite different constructs (Koburtay et al., 2023). While spirituality refers to finding ‘meaning, purpose, and connectedness’ with oneself, others, and the ultimate reality, religion refers to beliefs and attitudes prescribed by culture and institutions (Chakradhar et al., 2022). Some researchers (Chowdhury, 2018) argue that despite their differences these two concepts are interrelated, and an individual can have both. A sense of intrinsic religiosity is closely related to a sense of spirituality, since it reflects the true spirit of religion, and enhances one's sense of meaning in life, connection with the community, and environmental sustainability (Chowdhury, 2018). So, a person could be both religious and spiritual, nonreligious and nonspiritual, or religious and non-spiritual (Chowdhury & Fernando, 2013). The purpose of this study is not to investigate the differences or connections between spirituality and religion; instead, spiritual well-being in this study is merely defined as a person's current state of spiritual health and quality of life, which is manifested in positive moods, behaviors, and thoughts about relationships with oneself, others, the divine, and the environment (Pong, 2022).

Gender and Age

Research indicates significant effects of age and gender on happiness or subjective well-being (Gonza & Burger, 2017; Thomas et al., 2017). Prior studies (e.g., Batz-Barbarich et al., 2018; Perry, 2020) have found that gender differences in this context. It has been suggested (Wood et al., 1989) that women report higher levels of happiness and life satisfaction than men and that women are more likely to find fulfillment and happiness in meaningful experiences, while men may be more satisfied with material gains and professional accomplishments (Brakus et al., 2022). Nevertheless, previous research has also found that overall happiness and life satisfaction levels are quite comparable between men and women (Inglehart, 2002). The impact of age on subjective well-being varies; typically, older individuals report higher well-being than younger ones (Stern et al., 2018), but this pattern differs across various cultures and countries (Diener & Ryan, 2009). Subjective well-being also shows a curvilinear trend with age, often decreasing during middle age (Sung, 2017). The interaction of gender and age is crucial to understanding this phenomenon, as emphasized in studies like Leontyeva et al. (2016). Based on an Iranian sample Mahmoodi et al. (2022), found that elderly women report lower well-being and a more negative self-view than their male counterparts. Additionally, age and gender are intertwined with other determinants like marital status, socio-economic background, and social relationships, which all significantly contribute to happiness levels (Amirzai & Sönmez, 2022; Arias-Monsalve et al., 2022). Recognizing the intricate connections between age, gender, and subjective well-being is essential for creating effective strategies and policies to promote well-being and happiness among various age groups and genders.

Interconnectedness of Causal Conditions and the Conceptual Model Development

This study aims to establish that subjective well-being is a function of financial well-being, family relationship quality, spiritual well-being, age, and gender. The complexities of conceptualizing subjective wellbeing are addressed by viewing these factors as conjunctional causalities. Conjunctional causalities refer to a concept in causality where multiple factors or conditions jointly contribute to a particular outcome or effect (Mill, 1843). This concept suggests that the effect occurs as a result of the combination of these factors, rather than due to a single cause (Ragin, 2014; Rihoux & Ragin, 2008). I will argue in the following paragraphs that the factors mentioned above are interconnected and contribute to subjective wellbeing:

Several studies (e.g., Aydin, 2017; Jain et al., 2019) have investigated the relationship between household income and subjective well-being though the findings are not conclusive. Previous research also suggests that financial wellness is associated with family relationship quality (Wilmarth et al., 2014), while Jain et al. (2019) found that marriage happiness increased with an increase in family income, but not over the long run. However, financial stress and diminished financial satisfaction can lead to a lower level of marital satisfaction, which can result in a decreased level of family relationships and more likely to predict divorce (Aydin, 2017; Kelley et al., 2023). Wilmarth et al. (2014) found that changed financial wellness can adversely affect marriage satisfaction, as can financial stressors and communication patterns. Ngamaba et al. (2020) found a moderate, significant, and positive association between financial satisfaction and subjective wellbeing. Pleeging et al. (2021) found that (economic) hope mediates the relation between income and subjective Well‑Being. Although income positively correlates with subjective well-being, many factors may influence this relationship (Diener et al., 2013; Pleeging et al., 2021) indicating that the relationship is complex and a configurational model is required.

Families play a crucial role in psychological health, psychological distress, and life satisfaction, like financial and human capital (i.e., wellbeing) (Grevenstein et al., 2019). Financial unwellness has been shown to negatively influence marital relationships and wellbeing (Kelley et al., 2023). Couples' relationship quality and relationship stability can be diminished when contextual vulnerabilities and individual vulnerabilities interact with external stressors such as COVID-19 (Kelley et al., 2023). Previous research found that couples' sexual outcomes are negatively affected by financial stress, and financial and sexual communication weakens financial stress effects (Curran et al., 2021).

Botha et al. (2019) report that subjective well-being is related to satisfaction with life and spiritual indicators, especially the opportunity to engage in spiritual practices. In his study of Chinese University students, Pong (2022) found a negative relationship between money attitude and spiritual well-being; he argued that well-being does not necessarily depend on money and that money is the opposite of religion and spirituality. According to Vaughan (1991), spirituality can enhance intimacy, improve communication patterns, and improve relationship quality. Accordingly, Dobrowolska et al. (2020) found that religious beliefs may affect marital satisfaction; however, there is conflicting evidence regarding whether religious affiliation can also affect marriage satisfaction. There is mixed evidence about whether marriage has a greater impact on men’s or women’s well-being depending on their gender (see Thomas et al., 2017 for a review). Recent research supports the idea that men are more satisfied with their marriages than women (Dobrowolska et al., 2020).

The factors used in this research are aligned with the PERMA model, highlighting financial wellbeing boosts pleasure, engagement, and accomplishment. Strong family relationship quality reinforces the ‘Relationships’ and ‘Meaning’ aspects of the model, while spiritual well-being, resonating with ‘Meaning’, augments overall pleasure. Age influences the prioritization of PERMA’s factors, with younger individuals often focusing on Accomplishment and Engagement, while older individuals may value Relationships and Meaning more significantly. Gender also plays a role, as societal norms can shape how men and women experience and prioritize these elements, although this varies across individuals and cultures. Together, these elements—encompassing financial, family, and spiritual aspects, along with age and gender—intricately enhance and shape the PERMA model's dimensions, mirroring the varied routes to fulfillment and subjective well-being. Based on the aforementioned discussion and empirical evidence from previous research it indicates that the conceptualization of subjective wellbeing needs a configuration theory turn (i.e., based on conjunctional causation, equifinality and causal asymmetry) (Pappas & Woodside, 2021; Woodside, 2014), as such this research envisioned the conceptual model below (Fig. 1).

Methodology

Data Profile

A survey and data collection firm was hired to collect responses using a self-administered survey questionnaire from Dhaka, Bangladesh. Bangladesh’s capital and most populous city is Dhaka, which is geographically in the middle of the country. The survey firm appointed a group of data collectors who went personally to the respondents’ offices in prominent commercial areas of the city, namely—Motijheel, Gulshan, Mohammadpur, Banani, and Uttara, and distributed the questionnaire and requested them to fill it out. Data collection took place between April and May 2023. An overall response rate of 37.82% was achieved by approaching 870 people and having 329 people complete the survey questions. Considering the importance of family relationships in the present study, this research only selected married respondents after deleting incomplete responses, resulting in a total of 250 data points. 88% of the respondents reported having a master's degree as their highest level of education. The survey did not inquire about religious affiliation, as it may be deemed sensitive. However, it is noted that over 90% of the country's population is Muslim by faith. Table 1 depicts the detailed respondent profiles:

Measurement Items

This research utilized a semantic differential scale with four items adapted from Lyubomirsky and Lepper (1999) to measure subjective well-being. This scale includes items like ‘in general, I consider myself not a very happy person (1) to a very happy person (7),’ and 'compared with most of my peers, I consider myself less happy (1) to more happy (7).' Financial well-being was assessed using six items from the CFPB's Financial Well-Being Scale (2017). These items are rated on a perceptual Likert scale ranging from 'completely' (1) to 'not at all' (5). Examples of these items are “I could handle a major unexpected expense” and “I am securing my financial future.” To measure the quality of relationships, particularly with spouses among married couples, this research used a ten-item scale from Kim and Waite (2014). This scale includes questions like “How would you describe your (marriage/relationship) with [current/recent partner]?” rated from 'Very unhappy' (1) to 'Very happy' (7), and “In general, how often do you think that things between you and your partner are going well?” rated from 'never' (1) to 'always' (7). Spiritual well-being was measured using an adapted 10-item scale from Malinakova et al. (2017), rated on a 7-point Likert scale. Example items include “I believe that Almighty is concerned about my problems” and “My relationship with Almighty contributes to my sense of well-being,” rated from 'Strongly disagree' (1) to 'Strongly agree' (7). Gender in this study was categorized as a binary variable, labeled male (1) or female (2). Age was treated as a categorical variable, segmented into groups ranging from 21 to 25 years to over 56 years. In the country, the typical age to complete graduation and begin working is 21, with retirement age set at 60. Consequently, eight age groups were established. The first group, labeled as '1', encompasses ages 21–25, and the last group, marked as '8', includes individuals aged 56 and older. In total, age was divided into eight categories for data collection purposes. For the QCA analysis, these groups were consolidated based on the median age bracket of 36–40 years. This led to the formation of three broader categories: the younger group (ages 21–35) labeled as '1', the middle-aged group (ages 36–40) also labeled as '1', and the older age group (ages 41–56) labeled as '3'. Table 2 provides a detailed list of the items that met rigorous structural equation modeling standards for reliability and validity.

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA)

A fundamental aim of QCA is to address the causal complexity associated with social phenomena, recognizing that causation doesn’t operate alone; rather, the outcome is the result of a complex combination of factors (Ide & Mello, 2022). QCA is based on three pillars—conjunctural causation, equifinality, and causal asymmetry. In conjunctural causation, conditions are combined in different configurations; equifinality means that outcomes can be reached through different pathways, and causal asymmetry means that outcomes and non-outcomes may require different explanations (Pappas & Woodside, 2021; Ragin, 2014; Rihoux & Ragin, 2008; Woodside, 2014). Pappas and Woodside (2021) categorize QCAs as crisp-set QCAs (csQCAs), multi-value QCAs (mvQCAs), or fuzzy-set QCAs (fsQCAs). Several limitations of csQCA and mvQCA have been overcome with fsQCA; it integrates Boolean algebra, fuzzy set theory, and fuzzy logic theory with QCA theory and analyzes combinations of conditions systematically (Ragin, 2014; Rihoux & Ragin, 2008). Various disciplines in social science have used fsQCA as a methodological choice (Pappas & Woodside, 2021). FsQCA 3.0 was used for this research. The analysis and results section discuss the step-by-step detailed work procedure of fsQCA.

Analysis and Results

Common Method Bias

Harman's one-factor test was used to detect the possibility of a common method (CMB). CMBs are presumed to exist when the total variance of one factor exceeds 50% (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The analysis is not threatened by CMB since a single factor explains 18.99% of the variance.

Reliability and Validity

SmartPLS software was used to conduct construct reliability and validity tests (Ringle et al., 2015) before pursuing the fuzzy-set analysis (Pappas & Woodside, 2021). After conducting a factor analysis, it found that two items on the subjective well-being scale, three items on the financial well-being scale, and seven items on the relationship quality and spiritual well-being scale were below the 0.60 threshold (Hair Jr et al., 2014); therefore, they were not considered further. I then conducted two steps of reliability and validity checks. The first assessment was of composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha. Both CR (rho_a and rho_c) and alpha values for all variables exceeded 0.70 (Hair Jr et al., 2014). A convergent validity test was also conducted by observing the average variance extracted (AVE) scores, which exceeded 0.50 in all cases except the spiritual well-being (Hair Jr et al., 2014). Despite a slightly lower AVE score, spiritual well-being also shows sufficient convergence validity since all other indicators are well above the threshold.

The next step was to check the discriminant validity of the constructs using the Fornell–Larcker criterion (i.e., the square root of AVE for each latent variable was greater than the correlation value between any other construct). As Table 3 shows, the constructs used in this study have acceptable discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Henseler et al., 2016).

In addition, I calculated Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) for the latent constructs, which were all less than the threshold of 5 recommended by Hair Jr et al. (2014) and Henseler et al. (2016). After ensuring the reliability and validity of all latent variables, the fsQCA analysis was moved as discussed below.

FsQCA Analysis

The data analysis flow in the fsQCA software is depicted in the Fig. 2 below.

Calibration

In fsQCA analysis, calibration is the first step; it involves assigning a fuzzy membership score to the data (Pappas & Woodside, 2021). The research variables were measured with multiple items, so I combined them in SPSS and calibrated them into a fuzzy-set scale, as shown in Table 4. In order to calibrate the data, three points were considered—full non-membership (5%), crossover point (50%), and full membership (95%).

Necessary Condition Analysis

Analyzing the necessary conditions is the next step. The fsQCA approach assesses causal necessity and sufficiency using two key measures: consistency and coverage. Consistency indicates the extent to which elements of a subset also belong to a larger superset, while coverage evaluates the empirical significance of a given configuration (Fiss, 2011; Ragin, 2014; Rihoux & Ragin, 2008). Generally, configurations with low consistency lack empirical support, whereas coverage measures how many instances the configuration holds in (Ragin, 2014; Rihoux & Ragin, 2008). For a condition to be necessary, its consistency value must be at least 0.90 (Ragin, 2014; Rihoux & Ragin, 2008). Researchers using fsQCA frequently present and analyze coverage values, typically without adhering to a rigid threshold. The specific context of the study largely influences the interpretation of these values, and the importance of the results is generally evaluated through a qualitative lens rather than a strictly quantitative one (Fiss, 2011; Mello, 2021). Table 5 shows the necessary conditions for two possible outcomes: high subjective well-being and low/medium subjective well-being for the given sample; where no conditions meet the consistency threshold for being necessary conditions, it implies that these conditions are neither indispensable nor singularly responsible for high or low subjective well-being.

Sufficient Conditions Analysis

A sufficiency analysis is the last step (Ragin, 2014; Rihoux & Ragin, 2008). In order to assign each observation to a specific configuration (Ragin, 2014), it constructs a truth table (Analyze > Truth Table Algorithm) first (Pappas & Woodside, 2021). The truth tables are shown in Appendix 1 and 2. Afterward, the truth table frequency and consistency are sorted (Ragin, 2014). Both high subjective well-being and low/medium subjective well-being were measured using a consistency cutoff of 0.91 and 0.90, respectively. Following the definition of causal patterns using logic statements, the next step is to reduce them (Ragin, 2014; Rihoux & Ragin, 2008). This research identified two configurations of sufficient conditions for causing high subjective well-being and four configurations for causing low/medium subjective well-being in Table 6:

Discussion and Conclusion

The purpose of this research is to identify necessary and sufficient conditions (i.e., the combination of causal conditions) that lead to subjective well-being in a rarely studied population from a developing country Bangladesh. As a result, I considered five causal conditions: financial well-being, relationship quality, spiritual well-being, gender, and age; and analyzed them using fsQCA. According to the necessary conditions’ analysis (Table 5), no condition is necessary to have high subjective well-being or a low/medium subjective well-being. It is in line with the philosophical disposition of the concept of happiness or subjective well-being that "there is no simple or conflict-free way to happiness" (Staw, 1986, p. 52). Happiness is rather the result of a combination of various interrelated factors. This justifies the sufficiency analysis in QCA.

This research found two configurations for high subjective well-being, as below:

Proposition 1A:

Men of older age with a low perception of their financial well-being, yet possessing high-quality family relationships, are likely to experience high levels of subjective well-being.

The explanation for this finding is quite straightforward. The most important conditions for achieving subjective well-being for an older man (usually over 40) is marital satisfaction and family relationships. Income has not been included as a factor of subjective well-being since previous research has found that the relationship between income and happiness varies considerably between studies and samples (Muresan et al., 2020). Instead of using income, this research used a perceptual measure of financial well-being. Though the researched sample is rather fortunate in consideration of a developing country (median monthly family income of 1,100 + USD); they represent a typical urban middle class living in the capital (Ahamed, 2022). This is higher monthly income comparing to the whole country, however not that high if it compares to the highly educated working middle class living in the Dhaka city. Ngoo et al. (2015) argued that age and gender are not significant determinates of happiness in Asia, this research’s finding differs, it argues that age and gender should be considered in combination with other causal conditions to determine the subjective wellbeing. In conclusion, a perception of low financial well-being combined with high-quality family relationships leads to higher subjective well-being in older males.

Proposition 1B:

Younger women, despite having a low perception of their financial well-being, can also achieve high levels of subjective well-being if they have high-quality family relationships and a strong sense of spiritual well-being.

Despite low financial well-being perceptions, young women with high relationship quality and spiritual well-being have high subjective well-being. Brelsford (2013) found a significant association between spirituality and family relationship quality perceptions. Spiritual well-being is positively affected by family agreement on religious beliefs, according to Smith et al. (2013). Relationship quality is also believed to be influenced by family consonance on religion or spirituality. It has been well established in the literature that spiritual well-being and relationship quality are interconnected. Females are generally more religious or spiritual than men (Li et al., 2020). In addition, Pong (2022) indicates a negative association between money attitudes and spiritual well-being. The results of this study differ from those of La Barbera and Gürhan (1997) in that the combination of young age and other conditions leads to subjective well-being. In conclusion, young females with high relationship quality, high spiritual well-being, and low financial well-being have greater subjective well-being.

This research found four configurations for low/medium subjective well-being:

Proposition 2A:

Individuals with a high perception of financial well-being but low quality in family relationships and spiritual well-being are likely to experience low subjective well-being.

This finding is in line with many researchers that found money does not lead to happiness (Diener & Seligman, 2004). This configuration expresses that despite perceptions of higher financial well-being, especially in the context of a developing country, a low relationship quality and a low spiritual well-being leads to low subjective well-being. Ngoo et al. (2015), found that in Asian people’s life satisfaction the marital status is a significant contributor. This research reassures this finding by combining family relationship quality with spiritual well-being.

Proposition 2B:

Older individuals of any gender, facing low quality in family relationships and low spiritual well-being, tend to have low subjective well-being.

Previous research underscores the roles of spiritual well-being and family relationship quality in the subjective well-being of older adults. Lawler-Row and Elliott (2009) identified spiritual well-being as a crucial factor for subjective well-being, noting that its lack can lead to decreased levels. Pilger et al. (2017) observed that a richer spiritual life correlates with higher life satisfaction in older adults. Trapsinsaree et al. (2022) found that family or friends' support is vital for older individuals' spiritual well-being, and poor family relationships can detrimentally affect both spiritual and subjective well-being. Based on these studies, this proposition highlights the close interconnection between spiritual health, family relationship quality, and subjective well-being in older adults, emphasizing that deficiencies in either spiritual well-being or family relationships can substantially lower subjective well-being.

Proposition 2C:

Females with low quality in family relationships and low spiritual well-being are prone to experiencing low subjective well-being.

The third configuration suggests that for females, low quality in family relationships and low spiritual well-being are associated with reduced subjective well-being. Supporting research (Lawler-Row & Elliott, 2009; Pilger et al., 2017; Trapsinsaree et al., 2022) indicates that both family relationship quality and spiritual health significantly impact overall subjective well-being. Poor family ties can lead to emotional distress and stress, while a lack of spiritual fulfillment can diminish life's meaning and purpose. These factors jointly influence mental and emotional health, often resulting in lower subjective well-being.

Proposition 2D:

Older men with a high perception of financial well-being but low quality in family relationships are likely to have low subjective well-being.

The fourth configuration found that for older males, having low family relationship quality despite having high financial well-being leads to low subjective well-being. This proposition indicates a complex and multifaceted nature of subjective wellbeing. Previous studies indicate that while older men typically enjoy better financial well-being than older women (Foong et al., 2021), the quality of their family relationships is key to their subjective well-being. Older men, who are particularly aware of their need for nurturing and connection, are greatly affected by the state of their family relationships (Ryff, 1989). Their overall well-being is often compromised by prevalent issues such as loneliness and cognitive impairment, as well as the challenges associated with adjusting to life changes and reducing social networks (Lu et al., 2017; Naveed et al., 2022). Therefore, for older men, high financial well-being does not necessarily translate to high subjective well-being, especially if family relationships are poor, underscoring the importance of a balance between financial stability, family connections, social support, and mental health.

Implications, Limitations and Future Research Directions

A major contribution of this research is the identification of two configurations (sufficient conditions) for high subjective well-being and four configurations for low/medium subjective well-being. These findings have implications for understanding subjective well-being in general and for similar countries in Asia, Latin America, and Africa in particular where the middle class is expanding, characterized by higher education, increased earnings, and a tendency to reside in larger cities (Wietzke & Sumner, 2018). Furthermore, although this research has not identified any necessary conditions for causing high or low subjective well-being, the findings clearly indicate the importance of quality family relationships and spiritual well-being. However, there has been a general sense that family values are slipping in recent days in Asian countries, which are known for nurturing and maintaining high family relationships (Raymo et al., 2015). Despite this, the findings demonstrate that family relationship quality still plays a critical role in subjective well-being perceptions. In Bangladesh, especially in Dhaka city, the number of divorces is increasing. The situation is not much different in other Asia–Pacific countries (OECD, 2022). A number of factors contribute to the high divorce rate, including deteriorating marital relations. In line with prior studies (Chiang & Lee, 2018; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; North et al., 2008) that indicate the significance of strong family relationships in fostering elevated subjective well-being, this research also found that the quality of family relationships, when intertwined with factors such as spiritual well-being, gender, and age, can be influential in contributing to subjective well-being. While sociologists, policymakers, and society at large are preoccupied with finding the causes and remedies for this high divorce rate, these findings will instill hope in their hearts as many people in the region still consider good family relationships to be an important aspect of subjective well-being. These findings can be used by family relationship theory researchers to develop new theories. Further, it is quite comforting to find that people in the subcontinent, especially the highly educated, urban busybodies, still value spirituality.

In advancing the utilitarian perspective, which asserts that actions are morally right if they promote happiness or pleasure and wrong if they produce suffering or pain (de Lazari-Radek & Singer, 2017), this research discovered a bundle of causal conditions that lead to high or low subjective well-being. Subjective wellbeing is inherently multidimensional, reflecting a complex interplay of various contributing factors that influence well-being in non-linear ways (Mack, 2007). This understanding acknowledges that the elements impacting subjective wellbeing are diverse and interconnected, operating beyond simple linear patterns. In addressing the multidimensionality of social concepts like subjective wellbeing, QCA more suitable. This study determined that the combination of causal conditions is more important than the direct correlation of exogenous and endogenous variables in determining subjective well-being. The QCA doesn’t aim to test a theory rather it put forward the theory construction (Ragin, 2014; Rihoux & Ragin, 2008). The findings of this research, will prompt theory development in the subjective well-being research especially amid non-western developing countries.

This research has some important implications for theory, policymakers, and society at large, but there are some limitations that need to be addressed in future research. Firstly, the sample was skewed toward more educated and higher-income city dwellers. A representative sample should be used in future research. Second, subjective well-being encompasses a wide range of conditions or factors; future research should consider other domain-related factors as well as more demography-based variables. Furthermore, I advocate for testing the propositions (configurations) of this research in other cultures and comparing how these findings differ between western and non-western countries or between developing and developed countries.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (AFM Jalal Ahamed) upon reasonable request.

References

Ahamed, A. J. (2022). COVID-19-induced financial anxiety and state of the subjective well-being among the Bangladeshi middle class: The effects of demographic conditions. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 7(2), 142–158. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHD.2022.124893

Amirzai, F. R., & Sönmez, A. (2022). Socio-economic determinants of happiness: The case of Afghanistan. Sosyoekonomi, 30(52), 183–198. https://doi.org/10.17233/sosyoekonomi.2022.02.10

Arias-Monsalve, A. M., Arias-Valencia, S., Rubio-León, D. C., Aguirre-Acevedo, D.-C., Rengifo Rengifo, L., Estrada Cortes, J. A., & Paredes Arturo, Y. V. (2022). Factors associated with happiness in rural older adults: An exploratory study. International Journal of Psychological Research, 15(1), 70–83. https://doi.org/10.21500/20112084.5910

Aydin, N. (2017). Psycho-economic aspiration and subjective well-being: Evidence from a representative Turkish sample. International Journal of Social Economics, 44(6), 698–714. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-11-2015-0312

Barrafrem, K., Västfjäll, D., & Tinghög, G. (2020). Financial well-being, COVID-19, and the financial better-than-average-effect. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 28, 100410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100410

Bashir, I., & Qureshi, I. H. (2023). A systematic literature review on personal financial well-being: The link to key Sustainable Development Goals 2030. FIIB Business Review, 12(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/23197145221106862

Batz-Barbarich, C., Tay, L., Kuykendall, L., & Cheung, H. K. (2018). A meta-analysis of gender differences in subjective well-being: Estimating effect sizes and associations with gender inequality. Psychological Science, 29(9), 1491–1503. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618774796

Botha, B., Mostert, K., & Jacobs, M. (2019). Exploring indicators of subjective well-being for first-year university students. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 29(5), 480–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2019.1665885

Brakus, J. J., Chen, W., Schmitt, B., & Zarantonello, L. (2022). Experiences and happiness: The role of gender. Psychology & Marketing, 39(8), 1646–1659.

Brelsford, G. M. (2013). Sanctification and spiritual disclosure in parent-child relationships: Implications for family relationship quality. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(4), 639–649. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033424

Brüggen, E. C., Hogreve, J., Holmlund, M., Kabadayi, S., & Löfgren, M. (2017). Financial well-being: A conceptualization and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 79, 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.013

CFPB. (2017). Measuring financial well-being: A guide to using the CFPB financial well-being scale. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/financial-well-being-scale/

Chakradhar, K., Arumugham, P., & Venkataraman, M. (2022). The relationship between spirituality, resilience, and perceived stress among social work students: Implications for educators. Social Work Education, 42(8), 1163–1180. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2022.2072482

Chiang, H. H., & Lee, T. S. H. (2018). Family relations, sense of coherence, happiness and perceived health in retired Taiwanese: Analysis of a conceptual model. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 18(1), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13141

Chowdhury, R. M. (2018). Religiosity and voluntary simplicity: The mediating role of spiritual well-being. Journal of Business Ethics, 152, 149–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3305-5

Chowdhury, R. M., & Fernando, M. (2013). The role of spiritual well-being and materialism in determining consumers’ ethical beliefs: An empirical study with Australian consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 113, 61–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1282-x

Clark, A. E., & Senik-Leygonie, C. (2014). The great happiness moderation: Well-being inequality during episodes of income growth. In A. E. Clark & C. Senik (Eds.), Happiness and economic growth: Lessons from developing countries, studies of policy reform. Oxford Academic.

Curran, M. A., LeBaron-Black, A. B., Li, X., & Totenhagen, C. J. (2021). Introduction to the special issue on couples, families, and finance. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 42(2), 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-021-09771-7

D’Ambrosio, C., Jäntti, M., & Lepinteur, A. (2020). Money and happiness: Income, wealth and subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 148, 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02186-w

De Lazari-Radek, K., & Singer, P. (2017). Utilitarianism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Diener, E. (2006). Guidelines for national indicators of subjective well-being and ill-being. Applied Research Quality Life, 1, 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-006-9007-x

Diener, E., & Ryan, K. (2009). Subjective well-being: A general overview. South African Journal of Psychology, 39(4), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124630903900402

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00501001.x

Diener, E., Tay, L., & Oishi, S. (2013). Rising income and the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(2), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030487

Diener, E., & Tov, W. (2011). National accounts of well-being. In K. Land, A. Michalos, & M. Sirgy (Eds.), Handbook of social indicators and quality of life research. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2421-1_7

Dobrowolska, M., Groyecka-Bernard, A., Sorokowski, P., Randall, A. K., Hilpert, P., Ahmadi, K., Alghraibeh, A. M., Aryeetey, R., Bertoni, A., & Bettache, K. (2020). Global perspective on marital satisfaction. Sustainability, 12(21), 8817. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218817

Fan, L., & Henager, R. (2022). A structural determinants framework for financial well-being. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 43(2), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-021-09798-w

Fiss, P. C. (2011). Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Academy of Management Journal, 54(2), 393–420. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.60263120

Foong, H. F., Haron, S. A., Koris, R., Hamid, T. A., & Ibrahim, R. (2021). Relationship between financial well-being, life satisfaction, and cognitive function among low-income community-dwelling older adults: The moderating role of sex. Psychogeriatrics, 21(4), 586–595. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12709

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Sage Publications.

Gomez, R., & Fisher, J. W. (2003). Domains of spiritual well-being and development and validation of the Spiritual Well-Being Questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(8), 1975–1991. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00045-X

Gonza, G., & Burger, A. (2017). Subjective well-being during the 2008 economic crisis: Identification of mediating and moderating factors. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18, 1763–1797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9797-y

Goudie, R. J., Mukherjee, S. N., De Neve, J. E., Oswald, A. J., & Wu, S. (2014). Happiness as a driver of risk-avoiding behavior: Theory and an empirical study of seatbelt wearing and automobile accidents. Economica, 81(324), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12094

Grevenstein, D., Bluemke, M., Schweitzer, J., & Aguilar-Raab, C. (2019). Better family relationships––Higher well-being: The connection between relationship quality and health related resources. Mental Health & Prevention, 14, 200160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mph.2019.200160

Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2019). Changing world happiness. In World Happiness Report 2019 (pp. 11–46). New York: Sustainable Developemnt Solutions Network.

Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

Höltge, J., Cowden, R., Lee, M. T., Bechara, A., Joynt, S., Kamble, S., Khalanskyi, V., Shtanko, L., Kurniati, N., & Tymchenko, S. (2023). A systems perspective on human flourishing: Exploring cross-country similarities and differences of a multisystemic flourishing network. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 18(5), 695–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2022.2093784

Huang, H., & Humphreys, B. R. (2012). Sports participation and happiness: Evidence from US microdata. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(4), 776–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2012.02.007

Iannello, P., Sorgente, A., Lanz, M., & Antonietti, A. (2021). Financial well-being and its relationship with subjective and psychological well-being among emerging adults: Testing the moderating effect of individual differences. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(3), 1385–1411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00277-x

Ide, T., & Mello, P. A. (2022). QCA in international relations: A review of strengths, pitfalls, and empirical applications. International Studies Review, 24(1), viac008. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viac008

Inglehart, R. (2002). Gender, aging, and subjective well-being. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 43(3–5), 391–408.

Jain, M., Sharma, G. D., & Mahendru, M. (2019). Can I sustain my happiness? A review, critique and research agenda for economics of happiness. Sustainability, 11(22), 6375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226375

Jones, P. (2023). Mindfulness and nondual well-being—What is the evidence that we can stay happy? Review of General Psychology, 27(2), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/10892680221093013

Kelley, H. H., Lee, Y., LeBaron-Black, A., Dollahite, D. C., James, S., Marks, L. D., & Hall, T. (2023). Change in financial stress and relational wellbeing during COVID-19: Exacerbating and alleviating influences. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 44(1), 34–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09822-7

Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

Kim, J., & Waite, L. J. (2014). Relationship quality and shared activity in marital and cohabiting dyads in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project, Wave 2. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(Suppl_2), S64–S74. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbu038

Koburtay, T., Jamali, D., & Aljafari, A. (2023). Religion, spirituality, and well-being: A systematic literature review and futuristic agenda. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 32(1), 341–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12478

La Barbera, P. A., & Gürhan, Z. (1997). The role of materialism, religiosity, and demographics in subjective well-being. Psychology & Marketing, 14(1), 71–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199701)14:1%3C71::AID-MAR5%3E3.0.CO;2-L

Lakshmanasamy, T. (2022). Money and happiness in India: Is relative comparison cardinal or ordinal and same for all? Journal of Quantitative Economics, 20(4), 931–957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40953-022-00326-7

Lambert D’raven, L., & Pasha-Zaidi, N. (2016). Using the PERMA model in the United Arab Emirates. Social Indicators Research, 125, 905–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0866-0

Lambert, L., Passmore, H.-A., & Joshanloo, M. (2019). A positive psychology intervention program in a culturally-diverse university: Boosting happiness and reducing fear. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20, 1141–1162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9993-z

Lawler-Row, K. A., & Elliott, J. (2009). The role of religious activity and spirituality in the health and well-being of older adults. Journal of Health Psychology, 14(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105308097944

Leontyeva, E. G., Kalashnikova, T. V., Danilova, N., & Krakovetckaya, I. (2016). Subjective well-being as a result of the realization of projects of the elderly’s involvement into the social life. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences (EpSBS). Vol. 7: Lifelong Wellbeing in the World (WELLSO 2015). Nicosia, 2016., 72015, (pp. 1–6). https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.02.1

Li, Y., Woodberry, R., Liu, H., & Guo, G. (2020). Why are women more religious than men? Do risk preferences and genetic risk predispositions explain the gender gap? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 59(2), 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12657

Lingier, A., & Vandewiele, W. (2021). The decline of religious life in the twentieth century. Religions, 12(6), 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12060388

Lu, N., Lou, V. W., Zuo, D., & Chi, I. (2017). Intergenerational relationships and self-rated health trajectories among older adults in rural China: Does gender matter? Research on Aging, 39(2), 322–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027515611183

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803–855. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803

Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46, 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006824100041

Mack, E. (2007). Scanlon as natural rights theorist. Politics, Philosophy & Economics, 6(1), 45–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470594X07073004

Mahendru, M., Sharma, G. D., & Hawkins, M. (2022a). Toward a new conceptualization of financial well-being. Journal of Public Affairs, 22(2), e2505. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2505

Mahendru, M., Sharma, G. D., Pereira, V., Gupta, M., & Mundi, H. S. (2022b). Is it all about money honey? Analyzing and mapping financial well-being research and identifying future research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 150, 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.06.034

Mahmoodi, Z., Yazdkhasti, M., Rostami, M., & Ghavidel, N. (2022). Factors affecting mental health and happiness in the elderly: A structural equation model by gender differences. Brain and Behavior, 12(5), e2549.

Malinakova, K., Kopcakova, J., Kolarcik, P., Geckova, A. M., Solcova, I. P., Husek, V., Kracmarova, L. K., Dubovska, E., Kalman, M., & Puzova, Z. (2017). The spiritual well-being scale: Psychometric evaluation of the shortened version in Czech adolescents. Journal of Religion and Health, 56, 697–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0318-4

Mathew, V., Santhosh Kumar, P. K., & Sanjeev, M. (2024). Financial well-being and its psychological determinants—An emerging country perspective. FIIB Business Review, 13(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/23197145221121080

Mello, P. A. (2021). Qualitative comparative analysis: An introduction to research design and application. Georgetown University Press.

Mill, J. S. (1843). A system of logic, ratiocinative and inductive. Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer.

Muresan, G. M., Ciumas, C., & Achim, M. V. (2020). Can money buy happiness? Evidence for European countries. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15, 953–970. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09714-3

Naveed, M., Riaz, A., & Malik, N. (2022). Loneliness, cognitive functioning and quality of life in older adults. Forman Journal of Social Sciences, 1(2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.32368/FJSS.20220110

Netemeyer, R. G., Warmath, D., Fernandes, D., & Lynch, J. G., Jr. (2018). How am I doing? Perceived financial well-being, its potential antecedents, and its relation to overall well-being. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(1), 68–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx109

Ngamaba, K. H., Armitage, C., Panagioti, M., & Hodkinson, A. (2020). How closely related are financial satisfaction and subjective well-being? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 85, 101522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2020.101522

Ngoo, Y. T., Tey, N. P., & Tan, E. C. (2015). Determinants of life satisfaction in Asia. Social Indicators Research, 124, 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0772-x

North, R. J., Holahan, C. J., Moos, R. H., & Cronkite, R. C. (2008). Family support, family income, and happiness: A 10-year perspective. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(3), 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.475

OECD. (2022). Society at a glance: Asia/Pacific 2022. Paris: OECD.

Pappas, I. O., & Woodside, A. G. (2021). Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA): Guidelines for research practice in Information Systems and marketing. International Journal of Information Management, 58, 102310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102310

Perry, N. L. (2020). Gender differences in subjective well-being. In B. J. Carducci & C. S. Nave (Eds.), The Wiley encyclopedia of personality and individual differences: Personality processes and individual differences (pp. 191–194). Wiley.

Pilger, C., Santos, R. O. P. D., Lentsck, M. H., Marques, S., & Kusumota, L. (2017). Spiritual well-being and quality of life of older adults in hemodialysis. Revista Brasileira De Enfermagem, 70, 689–696. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2017-0006

Pleeging, E., Burger, M., & van Exel, J. (2021). Hope mediates the relation between income and subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(5), 2075–2102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00309-6

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Pong, H.-K. (2022). Money attitude and spiritual well-being. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(10), 483. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15100483

Poushter, J., Fetterolf, J., & Tamir, C. (2019). A changing world: Global views on diversity, gender equality, family life and the importance of religion. Pew Research Center, 44. https://www.observatorioreligion.es/upload/44/08/Global-Views-of-Cultural-Change.pdf

Ragin, C. C. (2014). The comparative method: Moving beyond qualitative and quantitative strategies. Univ of California Press.

Rahmani, Z., Mackenzie, S. H., & Carr, A. (2023). How virtual wellness retreat experiences may influence psychological well-being. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2023.03.007

Ramos, M. C., Cheng, C.-H.E., Preston, K. S., Gottfried, A. W., Guerin, D. W., Gottfried, A. E., Riggio, R. E., & Oliver, P. H. (2022). Positive family relationships across 30 years: Predicting adult health and happiness. Journal of Family Psychology, 36(7), 1216–1228. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000983

Raymo, J. M., Park, H., Xie, Y., & Yeung, W.-J.J. (2015). Marriage and family in East Asia: Continuity and change. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 471–492. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112428

Rihoux, B., & Ragin, C. C. (2008). Configurational comparative methods: Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and related techniques. Sage Publications.

Ringle, C., Da Silva, D., & Bido, D. (2015). Structural equation modeling with the SmartPLS structural equation modeling with the Smartpls. Brazilian Journal of Marketing, 13(2), 56–73.

Riyazahmed, D. K. (2021). Does financial behavior influence financial well-being? Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business, 8(2), 273–280. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no2.0273

Rizvi, M. A. K., & Hossain, M. Z. (2017). Relationship between religious belief and happiness: A systematic literature review. Journal of Religion and Health, 56, 1561–1582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0332-6

Roig-Tierno, N., Gonzalez-Cruz, T. F., & Llopis-Martinez, J. (2017). An overview of qualitative comparative analysis: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 2(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2016.12.002

Ryff, C. D. (1989). In the eye of the beholder: Views of psychological well-being among middle-aged and older adults. Psychology and Aging, 4(2), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.4.2.195

Seligman, M. (2018). PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(4), 333–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1437466

Sharif Nia, H., Gorgulu, O., Naghavi, N., Robles-Bello, M. A., Sánchez-Teruel, D., Khoshnavay Fomani, F., She, L., Rahmatpour, P., Allen, K.-A., & Arslan, G. (2021). Spiritual well-being, social support, and financial distress in determining depression: The mediating role of impact of event during COVID-19 pandemic in Iran. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 754831. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.754831

Shek, D. T. (2005). A longitudinal study of perceived family functioning and adolescent adjustment in Chinese adolescents with economic disadvantage. Journal of Family Issues, 26(4), 518–543. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X04272618

Simão, T. P., Caldeira, S., & De Carvalho, E. C. (2016). The effect of prayer on patients’ health: Systematic literature review. Religions, 7(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7010011

Singh, D., & Malik, G. (2022). A systematic and bibliometric review of the financial well-being: Advancements in the current status and future research agenda. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 40(7), 1575–1609. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-06-2021-0238

Singh, K., Saxena, G., & Mahendru, M. (2023). Revisiting the determinants of happiness from a grounded theory approach. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 39(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOES-12-2021-0236

Smith, L., Webber, R., & DeFrain, J. (2013). Spiritual well-being and its relationship to resilience in young people: A mixed methods case study. SAGE Open, 3(2), 2158244013485582. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013485582

Staw, B. M. (1986). Organizational psychology and the pursuit of the happy/productive worker. California Management Review, 28(4), 40–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165214

Stern, B. Z., Strober, L., DeLuca, J., & Goverover, Y. (2018). Subjective well-being differs with age in multiple sclerosis: A brief report. Rehabilitation Psychology, 63(3), 474–478. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000220

Sulphey, M. (2020). Can spirituality and long-term orientation relate to workplace identity? An examination using SEM. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 41(9/10), 1038–1057. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-06-2020-0211

Sung, Y. A. (2017). Age differences in the effects of frugality and materialism on subjective well-being in Korea. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 46(2), 144–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcsr.12246

Thomas, P. A., Liu, H., & Umberson, D. (2017). Family relationships and well-being. Innovation in Aging, 1(3), igx025. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igx025

Trapsinsaree, D., Pothiban, L., Chintanawat, R., & Wonghongkul, T. (2022). Factors predicting spiritual well-being among dependent older people. Trends in Sciences, 19(1), 1718–1718. https://doi.org/10.48048/tis.2022.1718

Vaughan, F. (1991). Spiritual issues in psychotherapy. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 23(2), 105–119.

Verbakel, E. (2012). Subjective well-being by partnership status and its dependence on the normative climate. European Journal of Population, 28(2), 205–232.

Vishkin, A., Bigman, Y., & Tamir, M. (2014). Religion, emotion regulation, and well-being. Religion and Spirituality across Cultures. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8950-9_13

Vlaev, I., & Elliott, A. (2014). Financial well-being components. Social Indicators Research, 118, 1103–1123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0462-0

Wietzke, F.-B., & Sumner, A. (2018). The developing world’s “new middle classes”: Implications for political research. Perspectives on Politics, 16(1), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592717003358