Abstract

This article aims to provide insights into the intergenerational social mobility of Spanish workers, comparing the occupational prestige of sons and daughters to that of their fathers when the offspring were aged sixteen. We used a pooled-sample for the years 2007–2010, from a nationally representative data base, the Spanish Quality of Working Life Survey, to compute transition matrices, and to estimate the intergenerational elasticity of occupational prestige, considering differences by gender and age group. Our results confirmed that mobility in Spain is in the medium range, from an international perspective, and is slightly higher for daughters than for sons. By age, the younger generation presents an upward jump in prestige with respect to the older generation, along with lower values of intergenerational elasticity. This suggests that the father’s effect may be weakening across generations. It is notable that our conclusions held after passing a series of robustness checks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

SIOPS: The Standard International Occupation Prestige Scale (Treiman 1977). The main advantage of PRESCA2 over SIOPS is that the former provides a cardinal measure of occupational prestige, whereas the latter is merely ordinal. See “Data sources” section, for more details.

In Nordic countries and, to a lesser extent, in certain Continental countries, a re-emergence of mobility based on meritocracy seems to be observed (Esping-Andersen and Wagner 2012).

Although female participation has markedly increased during recent decades, notable differences still exist between men and women in participation: interruptions due to maternity and child rearing are almost exclusively borne by mothers, hence likely influencing participation and future prospects in career achievement.

Temporary, part-time, and unemployment rates are, respectively, 26.0%, 9.5% and 12.5%, for men and 27.7%, 27.6% and 15.8% for women (Labour Force Survey, 2019: II quarter). According to the 2014 wave of the Wage Structural Survey, average hourly wages were €16.68 and €13.12 for men and women, respectively. As for 2017, the Gini index for income inequality was 0.35 (0.31 for the Eurozone, World Bank), whereas the Duncan index for occupational segregation was 0.50, and over-education was above 25% (Garcia-Mainar et al. 2015).

Information for parents’ occupation was not present in previous waves.

In the section devoted to discussion, occupational prestige of mothers was also included in estimations as an additional sensitivity analysis.

The reasons for the absence of father’s occupation were unknown. It could be due to non-working fathers (unemployed, non-active, retired); non-response; or non-existence (absent, dead, etc.…). It supposed missing less than 10% of the initial sample.

The Appendix presents a comparison with data drawn from the Labour Force Survey for the same time period. The sample proportion of 41% women resembles the population percentage of working women.

Sample descriptive statistics for the whole set of variables used in the analysis are reported in the Appendix.

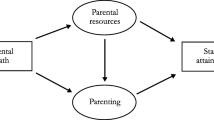

This is the standard approach to compute intergenerational elasticity. Studies attempting to investigate the mechanism through which parental background is reproduced in children’s outcomes add mediators to this simple specification. The most clear example is education (see, for instance, Raitano and Vona 2015a, b; or Palomino et al. 2019).

The ranking indices were (1) a simple summation of the elements of the leading diagonal; (2) the summation of the elements below the leading diagonal; (3) the summation of the elements above the leading diagonal; (4) the summation of the elements above and below the leading diagonal; (5) the Shorrocks index, computed, for a given (square) matrix A of dimension n, as (n − traceA)/(n − 1); (6) a weighted mobility index due to Bartholomew that, if aij is the proportion of daughters or sons in quantile j whose parents were in quantile i, is defined by (1/n)ΣiΣjaij |i − j| and (7) an adjusted version computed by (1/n)ΣiΣjaij (i − j)2. In all cases, except (1), the larger the index size, the higher the mobility. See Dearden et al. (1997), Hirvonen (2008) and De Pablos and Gil (2016) for description and discussion of the mobility indices.

An initial exercise was to estimate a pooled sample with a dummy for gender (1 = son, 0 = daughter), included on its own, and interacted with all the other regressors, to test whether differences by gender were statistically significant (this has been done in this and in all subsequent specifications). In nearly all cases, the hypothesis of gender equality in coefficients was rejected. In particular, the gender dummy was positive and statistically significant, which reveals a distinct intergenerational association across genders (estimated coefficient for model I was 0.028 and standard deviation 0.012). Results not shown but available upon request.

In contrast, if individuals who remained in the sample had parents with higher occupational prestige than those individuals who dropped out of the sample because of the persistence being studied, then the estimated elasticity may not be so overestimated.

As in the case of children, occupational prestige may vary during the life-cycle of parents. Ideally, adding a polynomial of father’s age would help to control for this. However, there was no information in the survey on father’s age. Notwithstanding that, although the life-cycle bias for fathers may appear, it is expected to be smaller in our study than in the general case. Since fathers’ reported occupational prestige corresponded to that when the respondent was sixteen, variation in fathers’ age is not expected to be as large as it would be if individuals reported the occupational prestige of their fathers at the moment of the survey.

The age that maximizes prestige is attained from the expression α2 + 2α 3(Agei/100) = 0.

Although some more recent scales have been proposed, none is as disaggregated by occupations as PRESCA2. Carabaña and Gomez-Bueno (1996) show little or no influence of the gender of the raters, so that gender bias in prestige is at a minimum.

References

Arts, W., & Gelissen, J. (2002). Three worlds of welfare capitalism or more? A state-of-the-art report. Journal of European Social Policy, 12, 137–158.

Atkinson, A. (1981). On intergenerational income mobility in Britain. Journal of Post-Keynesian Economics, 3(2), 194–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/01603477.1980.11489214.

Atkinson, A. B., Maynard, A. K., & Trinder, C. G. (1983). Parents and children: Incomes in two generations. London: Heinemann Educational Books.

Becker, G. S., & Tomes, N. (1979). An equilibrium theory of the distribution of income and intergenerational mobility. Journal of Political Economy, 87(6), 1153–1189. https://doi.org/10.1086/260831.

Becker, G. S., & Tomes, N. (1986). Human capital and the rise and fall of families. Journal of Labor Economics, 4(3 Part II), S1–S39. https://doi.org/10.1086/298118.

Bergmann, B. R. (2011). Sex segregation in the blue-collar occupations: Women’s choices or unremedied discrimination? Comment on England. Gender and Society, 25(1), 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243210389813.

Bjorklund, A., & Jantti, M. (2009). Intergenerational income mobility and the role of family background. In W. Salverda, B. Nolan, & T. Smeeding (Eds.), Handbook of economic inequality (pp. 491–521). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199606061.013.0020

Black, S., & Devereux, P. (2011). Recent developments in intergenerational mobility. In D. Card, & O. Ashenfelter (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 4, part B, pp. 1487–1541). Amsterdam: North Holland. https://doi.org/10.3386/w15889.

Blanden, J. (2013). Cross-country rankings in intergenerational mobility: A comparison of approaches from Economics and Sociology. Journal of Economic Surveys, 27(1), 38–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.2011.00690.x.

Blanden, J. (2019). Intergenerational income persistence. IZA World of Labor, 176. https://doi.org/10.15185/izawol.176.v2.

Blau, P. M., & Duncan, O. D. (1967). The American occupational structure. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (2002). The inheritance of economic status: Education, class and genetics. In M. Feldman & P. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences: Genetics, behavior and society (Vol. 6, pp. 4132–4141). New York: Oxford University Press and Elsevier.

Bratsberg, B., Røed, K., Raaum, O., Naylor, R., Jäntti, M., Eriksson, T., et al. (2007). Nonlinearities in intergenerational earnings mobility: Consequences for cross-country comparisons. Economic Journal, 117(519), C72–C92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02036.x.

Caparrós, A. (2016). The impact of education on intergenerational occupational mobility in Spain. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.11.010.

Caparrós, A. (2018). Intergenerational occupational dynamics before and during the recent crisis in Spain. Empirica, 45(2), 367–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-016-9364-0.

Cappellari, L. (2016). Income inequality and social origins. IZA World of Labor, 261. https://doi.org/10.15185/izawol.261.

Carabaña, J. (1999). Dos estudios sobre movilidad intergeneracional. Madrid: Fundación Argentaria-Visor.

Carabaña, J. & Gómez-Bueno, C. (1996). Escalas de Prestigio Profesional. Madrid: Cuadernos Metodológicos CIS, n 19.

Carmichael, F. (2000). Intergenerational mobility and occupational status in Britain. Applied Economics Letters, 7, 391–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/135048500351339.

Cervini-Plá, M. (2013). Exploring the sources of earnings transmission in Spain. Hacienda Pública Española, 204(1), 45–66.

Cervini-Plá, M. (2015). Intergenerational earnings and income mobility in Spain. Review of Income and Wealth, 61, 812–828. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12130.

Chadwick, L., & Solon, G. (2002). Intergenerational income mobility among daughters. American Economic Review, 92(1), 335–344. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282802760015766.

Charles, M. (2011). A world of difference: international trends in women’s economic status. Annual Review of Sociology, 37(1), 355–371. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102548.

Collado, M. D., Ortuño-Ortín, I., & Romeu, A. (2008). Surnames and social status in Spain. Investigaciones Económicas, 33, 259–287. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=173/17332301.

Corak, M. (2013). Inequality from generation to generation: The United States in comparison. In R. S. Rycorft (Ed.), The economics of inequality, poverty, and discrimination in the 21st century (pp. 107–123). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Corak, M., & Piraino, P. (2011). The intergenerational transmission of employers. Journal of Labor Economics, 29(1), 37–68. https://doi.org/10.1086/656371.

Couch, K., & Dunn, T. (1997). Intergenerational correlations in labor market status: A comparison of the United States and Germany. Journal of Human Resources, 32(1), 210–232.

Crawley, D. (2014). Gender and perceptions of occupational prestige: Changes over 20 years. SAGE Open, 4(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013518923.

Crawley, S. L. (2011). Visible bodies, vicarious masculinity, and “The gender revolution”: Comment on England. Gender and Society, 25(1), 108–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243210389814.

Davia, M. A., & Legazpe, N. (2017). Understanding intergenerational transmission of deprivation in Spain: Education and marital sorting. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 52, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2017.08.002.

De Pablos, L., & Gil, M. (2016). Intergenerational educational and occupational mobility in Spain: Does gender matter? British Journal of Sociology of Education, 37(6), 721–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2014.969397.

Dearden, L. S., Machin, S., & Reed, H. (1997). Intergenerational mobility in Britain. Economic Journal, 107(440), 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00141.

DiDonato, L., & Strough, J. (2013). Do college students’ gender-typed attitudes about occupations predict their real-world decisions? Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 68(9–10), 536–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0275-2.

Di Pietro, G., & Urwin, P. (2003). Intergenerational mobility and occupational status in Italy. Applied Economics Letters, 10(12), 793–797. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350485032000081965.

England, P. (1992). Comparable worth theories and evidence. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

England, P. (2010). The gender revolution: Uneven and stalled. Gender and Society, 24, 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243210361475.

England, P. (2011). Reassessing the uneven gender revolution and its slowdown. Gender and Society, 25(1), 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243210391461.

England, P., Allison, P., & Wu, X. (2007). Does bad pay cause occupations to feminize, does feminization reduce pay, and how can we tell with longitudinal data? Social Science Research, 36, 1237–1256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.08.003.

Erikson, R., & Goldthorpe, J. (1992). The constant flux: A study of class mobility in industrial societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/230509.

Erikson, R., & Goldthorpe, J. (2002). Intergenerational inequality: A sociological perspective. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(3), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533002760278695.

Ermisch, J., Francesconi, M., & Siedler, T. (2006). Intergenerational mobility and marital sorting. The Economic Journal, 116(513), 659–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01105.x.

Esping-Andersen, G., & Wagner, S. (2012). Asymmetries in the opportunity structure. Intergenerational mobility trends in Europe. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 30(4), 473–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2012.06.001.

Francesconi, M., & Nicoletti, C. (2006). Intergenerational mobility and sample selection in short panels. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 21(8), 1265–1293. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.910.

Franzini, M., & Raitano, M. (2013). Inequality in Europe: What can be done? What should be done? Intereconomics, 48(6), 328–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-013-0477-4.

Garcia-Mainar, I., Garcia-Martín, G., & Montuenga, V. (2015). Over-education and gender occupational differences in Spain. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0811-7.

Garcia-Mainar, I., Garcia-Martín, G., & Montuenga, V. (2018). Occupational prestige and gender-occupational segregation. Work, Employment and Society, 32(2), 348–367.

Goldberger, A. S. (1989). Economic and mechanical models of intergenerational transmission. American Economic Review, 79(3), 504–513.

Güell, M., Rodríguez-Mora, J. V., & Telmer, C. (2015). The informational content of surnames, the evolution of intergenerational mobility, and assortative mating. Review of Economic Studies, 82(2), 693–735. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdu041.

Hakim, C. (2003). A new approach to explaining fertility patterns: Preference theory. Population and Development Review, 29(3), 349–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2003.00349.x.

Hauser, R., & Warren, J. (1997). Socioeconomic indexes for occupations: A review update and critique. Sociological Methodology, 27, 177–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9531.271028.

Hellerstein, J., & Morrill, H. (2011). Dads and daughters. The changing impact of fathers on women’s occupational choices. The Journal of Human Resources, 46(2), 333–372. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.46.2.333.

Hirvonen, L. H. (2008). Intergenerational earnings mobility among daughters and sons: Evidence from Sweden and a comparison with the United States. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 67(5), 777–826. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1536-7150.2008.00598.x.

Ichino, A., Karabarbounis, L., & Moretti, E. (2011). The political economy of intergenerational income mobility. Economic Inquiry, 49, 47–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.2010.00320.x.

Jäntti, M., & Jenkins, S. P. (2015). Income mobility. In A. B. Atkinson & F. Bourguignon (Eds.), Handbook of income distribution (Vol. 2, pp. 807–935). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Jerrim, J. (2017). The link between family background and later lifetime income: How does the UK compare to other countries? Fiscal Studies, 38(1), 49–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-5890.12081.

Johnsson, J. O., Grusky, D., Di Carlo, M., Pollack, R., & Brinton M. C. (2009). Microclass mobility: Social reproduction in four countries. American Journal of Sociology, 114(4), 977–1036. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/596566?journalCode=ajs.

Levanon, A., England, P., & Allison, P. (2009). Occupational feminization and pay: Assessing causal dynamics using 1950–2000 US census data. Social Forces, 88(2), 865–891. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.0.0264.

Long, J., & Ferrie, J. (2013). Intergenerational occupational mobility in Great Britain and the United States since 1850. American Economic Review, 103(4), 1109–1137. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.4.1109.

Loury, L. (2006). Some contacts are more equal than others: Informal networks, job tenure and wages. Journal of Labor Economics, 24(2), 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1086/499974.

Lungu, E., Zamfir, A., & Mucanu, C. (2013). A network analysis of the Romanian higher education graduates’ intra-generational mobility. International Review of Social Research, 3(3), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1515/irsr-2013-0020.

Magnusson, C. (2009). Gender occupational prestige and wages: A test of devaluation theory. European Sociological Review, 25, 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcn035.

Marqués-Perales, I., & Herrera-Usagre, M. (2010). ¿Somos más móviles? Nuevas evidencias sobre la movilidad intergeneracional de clase en España en la segunda mitad del siglo XX. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Reis), 131, 43–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/25746567.

McCall, L. (2011). Women and men as class and race actors: Comment on England. Gender and Society, 25(1), 94–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243210389812.

Nguyen, A., Hailen, G., & Taylor, J. (2005). Ethnic and gender differences in intergenerational mobility: A study of 26-year-olds in the USA. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 52(4), 544–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9485.2005.00355.x.

Nickell, S. (1982). The determinants of the occupational success in Britain. Review of Economic Studies, 49, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297139.

Österberg, T. (2000). Intergenerational income mobility in Sweden: What do tax-data show? Review of Income and Wealth, 46(4), 421–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.2000.tb00409.x.

Palomino, J. C., Marrero, G. A., & Rodríguez, J. G. (2019). Channels of inequality of opportunity: The role of education and occupation in Europe. Social Indicators Research, 143, 1045–1074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2008-y.

Pascual, M. (2009). Intergenerational income mobility: The transmission of socio-economic status in Spain. Journal of Policy Modeling, 31(6), 835–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2009.07.004.

Pellizzari, M. (2010). Do friends and relatives really help in getting a good job? Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 63(3), 494–510. https://doi.org/10.2307/40649714.

Peng, Y. (2001). Intergenerational mobility of class and occupation in modern England: Analysis of a four-way mobility table. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 18, 277–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0276-5624(01)80029-9.

Polavieja, J. (2008). The effect of occupational sex-composition on earnings: Job-specialization, sex role attitudes and the division of domestic labour in Spain. European Sociological Review, 24, 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcm043.

Polavieja, J., & Platt, L. (2014). Nurse or mechanic? The role of parental socialization and children’s personality in the formation of sex-typed occupational aspirations. Social Forces, 93(1), 31–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sou051.

Raitano, M. (2015). Intergenerational transmission of inequalities in Southern European countries in comparative perspective: Evidence from EU-SILC 2011. European Journal of Social Security, 2, 292–314.

Raitano, M., & Vona, F. (2015a). Measuring the link between intergenerational occupational mobility and earnings: Evidence from eight European countries. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 13(1), 83–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-014-9286-7.

Raitano, M., & Vona, F. (2015b). Direct and indirect influences of parental background on children’s earnings: A comparison across countries and genders. The Manchester School, 83(4), 423–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/manc.12064.

Reskin, B., & Maroto, M. (2011). What trends? Whose choices? Comment on England. Gender and Society, 25(1), 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243210390935.

Rudman, L., & Phelan, J. (2010). The effect of priming gender roles on women’s implicit gender beliefs and career aspirations. Social Psychology, 41(3), 192–202. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000027.

Salido, O. (2001). La movilidad ocupacional de las mujeres en España. Por una sociología de la movilidad femenina [Women occupational mobility in Spain. A sociology of female mobility]. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, CIS-Siglo XXI.

Sanchez-Hugalde, A. (2004). Movilidad intergeneracional de ingresos y educativa en España (1980–90). DT 2004/1. Barcelona: IEB.

Schwenkenberg, J. (2014). Occupations and the evolution of gender differences in intergenerational socioeconomic mobility. Economics Letters, 124, 348–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2014.06.017.

Solon, G. (1999). Intergenerational mobility in the labor market. In O. Ashenfalter & D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 3A, pp. 1761–1800). Amsterdam: North Holland.

Solon, G. (2002). Cross-country differences in intergenerational earnings mobility. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(3), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533002760278712.

Torche, F. (2015). Analyses of intergenerational mobility: An interdisciplinary review. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 657, 37–62.

Treiman, D. J. (1977). Occupational prestige in comparative perspective. New York: Academic Publishers.

Trifiletti, R. (1999). Southern European welfare regimes and the worsening position of women. Journal of European Social Policy, 9, 49–64.

Warren, J. R., Sheridan, J. T., & Hauser, R. M. (1998). Choosing a measure of occupational standing: How useful are composite measures in analyses of gender equality in occupational attainment? Sociological Methods and Research, 27(1), 3–76.

Weeden, K. A., & Grusky, D. B. (2005). The case for a new class map. American Journal of Sociology, 111(4), 141–212. https://doi.org/10.1086/428815.

Wegener, B. (1988). Kritik des Prestiges. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Acknowledgements

We thank Bryan Brooks for providing language help and proof reading the article. The authors would like to thank participants at the Journal of Youth Studies Conference in Copenhagen, 2015; and II International Conference of Sociology of Public and Social Policies in Zaragoza, 2015.

Funding

This work was supported by the Autonomous Government of Aragon (Research Group S32-17R), co-financed by ERDF 2014–2020, and University of Zaragoza (Grant UZ2018-SOC-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human and Animal Participants

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Table 9 compares sample data with those of the Spanish Labor Force Survey averaged for the same period as in our analysis. Since ECVT is a sample of workers only, employment rates could not be computed. The first columns of Table 9 show that the female employment rate was near 55%, 15 percentage points below that of males. The proportion of male/female in the sample resembled that of the active population, even though the age distribution differed to a certain extent between both samples (the younger were somewhat under-represented and the older over-represented).

Descriptive statistics in Table 10 show that sons’ average prestige was essentially the same as for daughters, both being higher than fathers’ average prestige and much higher than mothers’ average prestige. Average differences between son-father were larger than between daughter–father. A working mother was more frequently observed in the case of daughters than in the sons. Daughters were, on average, a bit younger and, clearly, better educated.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

García-Mainar, I., Montuenga, V.M. Occupational Prestige and Fathers’ Influence on Sons and Daughters. J Fam Econ Iss 41, 706–728 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09677-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09677-w