Abstract

In this study, the additional economic cost of disability for households is calculated using a standard of living approach (SoL) for Turkey. Firstly, the Standard of Living (SoL) index is determined using principal components analysis through the Household Budget Survey data for the year 2014. The cost of disability is estimated using ordered logit method by dividing the index into three income groups such as low, middle and high. As a result of the analysis, it is estimated that households with disabilities need additional financial support of at least 9.1% of household income in order to reach the same standard of living as those without disabled individuals. In addition, two different levels of disability, which are working life disability and daily life disability, are considered in estimating the cost of disability. While the cost caused by individuals’ disabilities in working life is 14.6% of their household's income, the ratio is 9.1% for the individuals’ disabilities in daily life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although disability is common in both developed and developing countries, those country groups differ in terms of disability rates. According to both World Bank and World Health Survey there are 785 million (15.6%) disabled individuals in the world. In developing countries the disability rate is low. For instance, the rate is 6.9% in Turkey (TurkStat 2011), 6.5% in China (Loyalka et al. 2014) and 2.1% in India (Raut et al. 2014). In such countries, due to limited health care, low nutrition, insecure living conditions, and insufficient prenatal care, children in particular tend to have serious diseases, resulting in higher rates of disability for children and youth. Although disability rates are higher in developing countries, most people do not survive to advanced older ages to encounter chronic types of disabilities because life expectancies are low in developing countries.

On the other hand, developed countries have higher disability rates because the life expectancies are much higher. For example, according to Eurostat, 27.8% of European Union (EU) citizens suffered from chronic illness or health problem in 2014, approximately 11% of Irish people of working age are disabled (Cullinan et al. 2013), and the distribution of disabled people in the United States is 12.6% (Lewis 2017). It is important to evaluate the cost of disability by considering the developmental level of countries. In the literature, there are many studies that examine the cost of disability in developed countries, however, very few studies are available for developing countries.

People with disabilities tend to encounter more economic and social barriers in their daily or working life activities, which accrue to additional economic costs of disability, both directly and indirectly. Policymakers have attempted to recover or at least to reduce the impact of these costs. The direct impact of the additional economic costs is derived from the private care and health expenditures of the disabled person. On the other hand, the indirect effect emanates from the fact that people with disabilities have lower financial and social well-being compared to people without disabilities (Tibble 2005).

Although a growing literature describes many approaches in identifying the individual’s disability situation on the additional cost of disability, there are relatively few examples of studies addressing this issue through a social model. Today, the social model, which was created by expanding the medical model to include the inconveniences of social shortcomings, has become more common in the literature (Cullinan et al. 2008).

In Turkey, when classifying legal disability status in accordance with Article 5 of Law No. 5378, international fundamental methods are taken as the basis of the ratings, classifications, and definitions determining the disability level of the individual and his/her special needs arising from the disability. In contrast, the medical model determines disability status or level based on the percentage of deficiencies in the medical functions of the body, and is generally used to identify the disability status used to determine the economic size of governmental aid or stimulation provided to disabled individuals. However, in this study disability status is evaluated based on the social model. One of the main reasons for this, is that the Household Budget Survey (HBS) used in this study defines disability status as physical and mental problems restricting an individual's daily life activities or working life. In the survey, an individual’s or his/her family’s declaration that he/she is physically or socially disabled is sufficient in determining the individual’s disability, regardless of any medical reports. Two levels of disability are used in the study. The first one is the level of difficulties a person has in satisfying his/her needs in daily life. The second one is the level of difficulties a person has in working life.

Due to a lack of available data, empirical studies determining the nexus between income and disability in developing countries has been relatively limited (Braithwaite and Mont 2009; Minh et al. 2015; Xiaolin et al. 2011). In developing countries, there are fewer studies measuring additional costs of disability (Loyalka et al. 2014; Palmer et al. 2018). The paper contributes to the literature in several ways. First, this study is the first to estimate the economic costs of disability in Turkey based on the condition of disability. In addition, this paper builds on previous studies among developing countries both by presenting more up-to-date and specific estimates of the costs and using more appropriate data to accurately identify households with disabled individuals.

This study is designed as follows: the next section presents the literature on the economic costs of disability using the SoL approach. The third section explains the standard of living approach used in the model for calculating the disability cost. The fourth section describes the empirical methodology and discusses the estimation results. Finally, the last section presents concluding remarks.

Literature Review

There are two main reasons for the additional costs of disability (Sen 2004). Firstly, it is argued that these costs are caused by the negative effects of difficulties in finding a job or low salaries among individuals with disabilities on the formation and development of human capital. This is referred to as the earning handicap. The second reason, referred to as the conversion handicap, is defined as the additional financial resources needed for households with disabled individuals in order to function as non-disabled individuals. The challenge is to generate a representative variable of real income level, taking into account the standard of living to function within a household's lifestyle, rather than the means for its development. The standard of living approach proposes to examine the cost of disability by comparing households with disabled and non-disabled members within the same level of welfare (e.g., standard of living).

Berthoud et al. (1993) was the first study to measure the cost of disabled individuals in the household using the standard of living (SoL) approach. The authors found that the additional cost of disability caused by the number of individuals with disabilities and the level of disability ranged from 4% (€14) to 31% (€112) of household income using United Kingdom data set for the year 1985. Kuklys (2005) investigated the cost of household disability for households through United Kingdom Household Panel data during the period 1996–1999 using an ordered probit estimation method, pooling the data with fixed effects and random effects panel estimation methods due to the panel characteristics of the dataset. According to the results, the cost of disability varied between 12% and 70% of household income based on demographic variables such as education level of the household head, marital status, and working status.

Zaidi and Burchardt (2005) investigated the additional cost of disability based on three different disability levels applying ordered logit estimation method using the SoL approach. They used different data sources from the UK for the years 1996–1997 and 1999–2000. They estimated that the cost of disability varied between 1.1% (€40) and 7.7% (€104) of income depending on the level of disability. In another study, Indecon (2004) measured the cost associated with disabled individuals in households for the years 1999 and 2000 in Ireland. They applied both ordered logit model and least squares estimation methods. The report stated that the additional cost of disability arising from the level of disability and the number of disabled persons in the household was associated with income level. The cost was estimated as 75.7% of income at the lowest income level and 13.4% (€628) at the highest income level.

In another study conducted in Ireland Cullinan et al. (2013) estimated the cost of individuals with disabilities at different disability levels over the age of 65. They used the ordered logit model and data for 2001. In the study, the cost of mid-level disability was estimated at 20.8% of income (€228), whereas the cost of higher levels of disability was estimated at 79.4% of income (€916). Cullinan and Livermore (2007) investigated the impoverishing effect of both the number of individuals with disabilities in households and socioeconomic factors of households in the United States. They applied a logit estimation method using panel data from 1996–1999. The authors estimated the impoverishing effect at 78% (€778) of household income.

Saunders (2007) determined the relationship between SoL and disability status using household socioeconomic variables. They applied an ordered logit estimation method using 1998–1999 Australian Household Budget Survey data. They concluded that the cost of the disabled individual to the household ranged from 40% to 49% depending on the level of disability. A study by Braithwaite and Mont (2009), which is based on a previous study by Zaidi and Burchardt (2005) conducted in developed countries, estimated the cost of living for households with a disabled individual in two developing countries. Using 2004 data from Vietnam and Bosnia and Herzegovina, the researchers found that the additional cost was 14% of household income in Vietnam, and 9% in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

There are some country case studies estimating the cost of disabled individuals in the household using the SoL approach, such as, 31 European countries (Anton et al. 2016), Spain (Brana and Anton 2011), China (Loyalka et al. (2014), Vietnam (Minh et al. 2015), Cambodia (Palmer et al. 2018), India (Raut et al. 2014), North China (Xiaolin et al. 2011). The common result of these studies is that there are significant additional costs to households with disabled individuals, and that the costs vary depending on the income level of households and the level of disability.

Mitra et al. (2018) also conducted a detailed literature review on studies using the SoL approach. The researchers noted that most studies in the literature were from high-income level countries, except for the studies previously cited, conducted in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Vietnam and China. To our knowledge, this study is the first to measure the additional economic costs of disabled individuals in the household using the SoL approach for Turkey. This is another contribution to the literature.

In developing countries such as Turkey, the level of difficulties faced by individuals is relatively high. Although they have low-levels of medical disability, their constrained social and working life creates higher additional costs. Therefore, in this study, disability status was defined according to the declaration of the disabled person or his/her relative instead of identifying using the medical model because of the problems caused by social pressure of the disabled person or his/her relative.

Model and Data

The measurement issue of disability cost is an important topic in the literature. Determining the methods to be used to identify the disability situation is also problematic. There are three basic approaches in the calculation of the additional economic costs caused by the disabled. In the first approach, which is called direct subjective approach, the total extra economic cost of disability is determined by asking individuals directly. Although this approach is seen as a simple way to determine the cost of disability, it has an important constraint. It is difficult to obtain consistent results in the calculation of the additional cost of disability due to problems arising from the sampling (Martin and White 1988; Wilkinson-Meyers et al. 2010; Wood and Grant 2010).

The second approach is the comparative approach, which is based on a comparison of consumption expenditures of two different sample groups comprised of individuals at the same with a disability and without disability. In general, this approach might give consistent results when people with disabilities consume similar goods. However, the most important limitation of this approach is to consider the source of the difference between two groups, that is originating from the presence of the disabled individuals (Jones and O’Donnell 1995; Matthews and Truscott 1990; Mitra et al. 2009).

The last approach is the Standard of Living Approach (SoL). In this method, the income levels of households, those with disabled individuals and those with no disabled individuals in the household are compared at a given quality of life or welfare. Hence, this method allows for estimating the extra income needed for households living with a disabled individual in order to reach the same level of well-being as households without a disabled individual. The extra income calculated by this method is defined as the additional economic cost of disability. The claim that the results obtained by this method is more consistent has been supported by many studies (Berthoud et al. 1993; Braithwaite and Mont 2009; Cullinan et al. 2011; Indecon 2004; Loyalka et al. 2014; Morciano et al. 2015; Palmer et al. 2018; Tibble 2005; Saunders 2007; Zaidi and Burchardt 2005).

This approach assumes that additional resources determine the living standard of a household which means that any increase in additional resources required by the disabled individual leads to a decrease in the standard of living of households. This decline is the result of insufficient resources being directed to goods and services, which are related to the disability. Thus, the disability cost can be identified as extra income needed by a household with a disabled individual in order to have the same standard of living as a household without a disabled individual. The SoL approach has many advantages over direct initiatives to calculate the disability cost. It does not require estimations from the sources or levels of specific costs related to disability, which may need expertise and the judgment of respondents. Furthermore, it complies with estimates using large-scale micro-data sets for broader purposes, so it is unlikely to be open to strategic response behavior among respondents.

This study has been developed within the framework of the SoL approach proposed by Zaidi and Burchardt (2005) and Tibble (2005). This approach has also been widely adopted (such as Anton et al. 2016; Braithwaite and Mont 2009; Brana and Anton 2011; Minh et al. 2015). This method determines the impact of income and disability on welfare by calculating required income to compensate for the presence of disabled individuals in the household at a given level of welfare. The cost of disability is described as additional income for households with disabled individuals to reach the same standard of living as households living non-disabled individuals. The income difference between households with and without members with disability at given SoL levels is shown in Fig. 1.

A household with a disabled individual is estimated to have standard of living of \({\text{S}}_{0}^{\text{D}}\), at a certain level of income Y0. The standard of living used to compare households without a disabled individual is higher at \({\text{S}}_{0}^{\text{ND}}\). Graphically, the ‘line’ showing the correlation between income and standard living for households with a disabled individual reaches below and to the right of the line for households without a disabled individual. This shows that the households with a disabled individual need higher income to have the same standard of living as households with no disabled individuals.

In the model presented in Fig. 1, a household’s standard of living is explained by income and disability status. Zaidi and Burchardt (2005) assumed that SoL increases monotonically with income. For the linear case in Fig. 1, the standard of living difference between households with a disabled individual and households without a disabled individual is indicated by “AC distance”. On the other hand, the cost of disability, is shown with “AB distance”. In this context, the SoL function is expressed as shown in Eq. 1:

where the sub index i: indicates households, SoL: standard of living index, Y: annual disposable household income, D: disability status of household, XH is a vector of household-level characteristics (such as, household size, health insurance) while XHoH is a vector of characteristics associated with the head of the household such as age, gender, education, marital status, ε unobservable characteristics, α constant term and β, θ, γ represents the estimation coefficients. The extra cost of disability is calculated as shown in Eq. 2.

The nexus between standard of living and income might assume a non-linear form and this can be analyzed empirically. For instance, SoL could be a quadratic function of income, or the semi log functional form which is a log-linear or linear-log form. In this paper, income was added to the model in its logarithmic forms for two reasons. First, it helped to make it easier to compare and interpret the findings to earlier studies in the literature. Second, the model may best fit the data in many cases, considering Bayesian Information Criteria in the case of models tested by maximum-likelihood and R2 in linear regressions.Footnote 1 In this paper, it is assumed that SoL has a linear-log relationship with income.

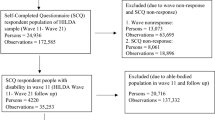

The 2014 Household Budget Survey(HBS) from TurkStat was used in the present study. The sample was representative of private households in Turkey. This survey provided knowledge about on consumption, assets, and wealth of surveyed households as well as demographic characteristics, health status, on all individuals residing within surveyed households. The sample of 10,122 households representing 21,400,000 individuals was used in the analysis.

In the study, firstly, the relationship between 33 assets owned by households and both income and disability was examined to estimate the household standard of living. As a result of analysis, 15 of these assets including floor heat, cable broadcast, satellite dish, dryer, carpet cleaning, bathroom, toilet, kitchen, central heating, natural gas, lift, internet, camera, microwave, and washing machine were determined as components of the SoL index at 1% statistically significant level. In addition, the principal components analysis, which is a frequently used method in establishing long-term economic status or living-standard representation variables, was also used in determining these variables (Filmer and Pritchett 2001; Palmer et al. 2018; Vyas and Kumaranayake 2006).

The SoL index of households was created by giving 1 point to each asset owned by households from the above mentioned assets. After that the SoL index was divided into three groups as \({\text{SoL}}_{\text{low}}\), if the SoL index was \({\text{SoL}}_{\text{low}} \le 5\), \({\text{SoL}}_{\text{medium}}\) if it was \(6 \le {\text{SoL}}_{\text{medium}} \le 10\) and \({\text{SoL}}_{\text{high}}\) if it was \({\text{SoL}}_{\text{high}} \ge 11\). The variables with more than 0.5 correlations between the principal components and values larger than 1 for eigenvectors were taken into consideration in categorical determination and sub-grouping of SoL.Footnote 2

TurkStat defined disabled status for individuals over six years old and classified it as a limitation on daily life (LDL) and as a limitation on working life (LWL) in HBS. LDL was a binary variable that took a value of 1 when the individual had a physical or mental problem that may interfere with daily life at least once in a six-month period, otherwise it took the value 0. LWL was also a binary variable that took the value of 1 if the individual had a mental or physical problem regardless of whether or not the individual was of working age, and a value of 0 otherwise.

Finally, variables of household size,Footnote 3 education level of household head, age and gender variables, and health insurance ownership were added to the model as independent variables representing observable heterogeneity. Table 1 provides summary statistics for the variables. There was at least one disabled person in 1683 households, 122 households with LDL, 491 households with LWL, 1070 households with both LDL and LWL out of the 10,122 households analyzed in the study. According to the 2014 HBS data, the total number of people with disabilities was 2176 and the rate of households with a disabled individual was 16%.

Methods and Empirical Results

The SoL index, a dependent variable in the model shown in Eq. 1, was a latent variable which means it cannot be directly observed. Since the SoL index variable was also a series of more than two with ordered properties, the ordered logit method is preferred as an estimation method for the equation as a parallel to previous studies. Thus, the logit model is as follows,

Here, \(\uptau_{\text{J}}\) indicates the breakpoints or threshold values in the \({\text{SoL}}^{*}\) distribution (Wooldridge 2002). This method utilizes the maximum likelihood functions and standardized logistic probability distribution. In the ordered logit estimation method, J − 1 number of models is defined and each estimated coefficients of models are assumed to be parallel. Parallelism assumption is an important assumption for ordered logit models. It can also be tested by Wolfe Gould, Brant, Wald, \(\upchi^{2}\) or likelihood ratio tests. In addition, the determination of goodness of fit of model in regression estimation methods by a value of R2 is not appropriate for all. Thus, the model goodness of fit should be investigated by more appropriate tests such as Mc Fadden, Mc Kevley and Zavonia, Cox-Snell.

The variable D in Eq. 1 was estimated by two different models using the variables of existing disability of individuals, disabled with daily life limitation, disabled with working life limitation. I assumed that any disabled person could have only daily life disability or working disability. For this reason, two different models were created in order to estimate additional cost more consistently according to the level of disability. The interpretation of the estimated parameters with the ordered logit model is different from the interpretation of the coefficients in ordinary estimation methods. Due to the increasingly widespread use of logistic regression in social sciences, the odds ratio has been frequently used in presenting results of survey and case studies.

The odds ratio can be used to interpret the coefficient obtained in logit models. If the odds ratio is smaller than 1, it is interpreted as the independent variable decreasing the probability of a dependent variable, and if greater than 1, the independent variable increasing the likelihood of a dependent variable. Moreover, if it is equal to 1, then it is interpreted as the independent variable not affecting the likelihood of a dependent variable. The \(- \frac{\uptheta }{\upbeta }\) value shown in Eq. 2 indicating the cost of disability is calculated by using means of coefficients obtained from ordered logit model. Therefore, both coefficients and odds ratios are given in Table 2. The robust standard errors are produced for the two estimated models to deal with the heteroscedasticity problem.

According to the results in Table 2, income was the most important variable in determining the standard of living and income level tended to increase SoL. In addition, households with female household heads, having health insurance, and having higher education levels led to an increase in having higher household standard of living. On the other hand, the household size decreased the probability of households (adult individuals, more than children) having a higher standard of living.

Considering the disability status, as expected, the effect on increasing the SoL was lower in households with working life disabilities (moderate) than in households with daily life disabilities. In other words, the cost of working life disability (severity) was 14.6%, whereas the cost of daily life of disabled individuals was 9.1%. This result indicates that the income barrier causes higher additional household cost than the transformation obstacle argument (Sen 2004). Although the odds ratio refers to the effect of the independent variable on the probability of a dependent variable while all other variables are constant, it does not include the information about the probability of the dependent variable. A marginal effect, or partial effect, calculates the effect on a dependent variable of a change in one of the regressors on the conditional mean. In the linear regression model, the marginal effect is equal to the relevant slope coefficient (Cameron and Trivedi 2010). For this reason, it would be incorrect to make a coefficient comparison according to the size of the odds values of logit models. Instead, the marginal effects of each independent variable, presented in Table 3, were obtained from the sample means of the independent variables.

Hence a logit model slope parameter of 0.1, for instance, implied that a one unit increase in the variable multiplied the initial odds ratio by exp (0.1) ≈ 1.105. This is a proportionate increase of 0.105 times the initial odds ratio; hence the relative probability of survival increased by 10.5%. This interpretation of the logit model is commonly used in biostatistics applications. It can be interpreted by economists as indicating that the marginal effect is semi-elastic. Then, considering a calculus approach, it can be interpreted as a logit model slope parameter of 0.1 indicating that a one-unit increase in the variable increased the odds ratio by a multiple 0.1.

According to Table 3, while a one-unit increase in income level tended to decrease the likelihood of households in \({\text{SoL}}_{\text{low}}\) by as much as 50%, it increased the likelihood of households in \({\text{SoL}}_{\text{middle }}\) by 48%. The coefficients of the marginal effects of disability indicated that while the probability of having a low standard of living for households with daily life disabilities was 6%, it was 8% for households with working life disabilities.

The two estimated models satisfy the parallelism assumption. Among the models, model 1 had the lowest information criterion and had the highest model goodness of fit. The estimated coefficients for Cut1 and Cut2 should be statistically different from each other. If these coefficients are statistically equal, the category of \({\text{SoL}}_{\text{middle }}\) should be eliminated. In Table 2, hypothesis that coefficients of Cut1 and Cut2 were equal was statistically tested by t test and rejected at 1% statistically significant level. Consequently, it was determined that there were no restrictions on the use of three living standards groups in analysis.

In this study, the cost of disability was estimated as lower than in previous studies in developed countries (such as Berthoud et al. 1993; Brana and Anton 2011; Cullinan et al. 2011, 2013; Indecon 2004; Kuklys 2005; She and Livermore 2007; Saunders 2007). However, it was estimated higher than developing country level studies (such as Braithwaite and Mont 2009). This indicates that more studies estimating the cost of living with a disabled person in the household using the SoL approach focusing on developing countries will contribute to the development of relevant literature and allow testing the consistency of the approach.

Conclusion

In this study, the additional cost of disabled individuals to households in Turkey is estimated using the standard of living approach. According to estimation results, households living with disabled individuals need a minimum of 14.6% of additional household income in order to reach the same standard of living as households living without disabled individuals. In the study, it is also found that while the cost of working life disability is 14.6% of income, the cost of daily life disability is 9.1%. This finding notes that the income disability barrier is higher than the transformation barrier, but the cost of the transformation obstacle on the household is still important.

In Turkey, the Administration of Disabled People was established in 1997, the First National Disabled People’s Council was held in 1999, and the Disability Equality Act was introduced in 2005. Since 6 February 2014, when a new legislative package on working conditions and rights of people with disabilities in Turkey was approved by the Turkish Parliament, many regulations were implemented. For instance, tax reductions for companies served as an incentive for the employment of disabled people. Although employment is mandatory, it is crucial to ensure that roles are both fulfilling and valuable. Also, all disability laws should be monitored and supervised by those who have broad knowledge about not only policy but also education, employment, health, etc.

On the other hand, in Turkey, in accordance with Law No. 2022 granting of disability pension to Turkish citizens who are 65 years of age; indigent, powerless and orphaned individuals can not benefit from any aid from social security institutions. Apparently, this law does not consider the obstacle of transformation caused by the disabled person. It is recommended that the necessary legal regulations should be made for individuals with daily life disability to benefit from the law.

Although this study provides a guide for policymakers by determining the cost of disability in Turkey, this study has some limitations. Therefore, in further studies it is recommended that researchers firstly expand the analysis period and, if possible, consider the effect of unobservable heterogeneity between households using panel data sets. In addition, it should be noted that the costs caused by disability can be calculated more consistently, if the disability status and level can be obtained in more detail. With these refinements, it will be possible to compare and test for consistency of the results obtained from studies on the additional cost of disabilities.

There are also limitations in the empirical analysis of the study. The main limitation is that the model and associated empirical analysis, is based on cross-sectional data which means that it does not consider the dynamic effects of income, wealth, and disability status. For this reason, a panel data set, or repeated cross-sectional data might be very helpful to provide more consistent estimates of these relationships based on a dynamic framework.

Moreover, there is no information about the disability severity in HBS. Of particular note, the disability registration does not infer that the severity is homogenous among the households. For this reason, alternative health and disability variables can be used to overcome this problem. These measures may give more information on the level of the disability severity and its effect on both standard of living and disability costs. Finally, the lack of panel data does not allow for investigating the disability shocks or the shift from healthy to disabled people and the effects on the standard of living.

Notes

The results of the analyzes will be provided by the authors upon request. In linear-log case, the estimated cost of disability as measured by the difference between Y0 and Y1 will be given as a percentage of household disposable income.

The results of the analyzes will be provided by the authors upon request.

The OECD equivalence scale is used, and the household size is calculated by multiplying 0.5 for all individuals aged 1, 14, and 0.3 for all individuals under the age of 14 for the reference person in the household.

References

Anton, J. I., Brana, F. J., & Rafael, M. B. (2016). An analysis of the cost of disability across Europe using the standard of living approach. SERİES,7(3), 281–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-016-0146-5.

Berthoud, R., Jane, L., & Stephen, M. (1993). Economic problems of disabled people. London: Policy Studies Institute.

Braithwaite, J., & Mont, D. (2009). Disability and poverty: A survey of World Bank poverty assessments and implications. ALTER-European Journal of Disability Research,3(3), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alter.2008.10.002.

Brana, F. J., & Anton, J. I. (2011). Pobreza, discapacidad y dependencia en España. Retrieved from http://janton.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/JIA__FJB_PEE.pdf.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2010). Microeconometrics using stata (Vol. 2). College Station, TX: Stata press.

Cullinan, J., Brenda, G., & Eamon, O. (2013). The welfare implications of disability for older people in Ireland. European Journal of Health Economics,14(2), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-011-0357-4.

Cullinan, J., Brenda, G., & Sean, L. (2008). New estimates of the cost of disability in Ireland using the standard of living approach. (Working Paper No. 0134), Department of Economics, National University of Ireland, Galway. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10379/942.

Cullinan, J., Brenda, G., & Sean, L. (2011). Estimating the extra cost of living for people with disabilities. Health Economics,20(5), 582–599. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1619.

Filmer, D., & Pritchett, L. (2001). Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data—or tears: An application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography,38(1), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2001.0003.

Indecon. (2004). Cost of disability research project, Dublin, National Disability Authority. Retrieved from http://nda.ie/File-upload/Indecon-Report-on-the-Cost-of-Disability.pdf.

Jones, A., & O’Donnell, O. (1995). Equivalence scales and the costs of disability. Journal of Public Economics,56(2), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2727(93)01416-8.

Kuklys, W. (2005). Amartya Sen’s capability approach: Theoretical insights and empirical applications. Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-28083-9.

Lewis, K. (2017). 2016 Disability statistics annual report. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire.

Loyalka, P., Lan, L., Gong, C., & Xiaoying, Z. (2014). The cost of disability in China. Demography,51(1), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0272-7.

Martin, J., & White, A. (1988). The financial circumstances of disabled adults living in private households. London: HM Stationery Office, Her Majesty’s Stationary Office.

Matthews, A., & Truscott, P. (1990). Disability, household income & expenditure: A follow up survey of disabled adults in the family expenditure survey. London: Stationery Office Books.

Minh, H. V., Kim, B. G., Nguyen, T. L., Palmer, M., Nguyen, P. T., & Le Bach, D. (2015). Estimating the extra cost of living with disability in Vietnam. Global Public Health,10(1), 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2014.971332.

Mitra, S., Palmer, M., Kim, H., Mont, D., & Groce, N. (2018). Extra costs of living with a disability: A review and agenda for research. Disability and Health Journal,10(4), 475–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.04.007.

Mitra, S., Patricia, A. F., & Usha, S. (2009). Health care expenditures of living with a disability: Total expenditures, out-of-pocket expenses, and burden, 1996 to 2004. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation,90(9), 1532–1540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2009.02.020.

Morciano, M., Hancock, R., & Pudney, S. (2015). Disability costs and equivalence scales in the older population in Great Britain. Review of Income and Wealth,61(3), 494–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12108.

Palmer, M., Williams, J., & McPake, B. (2018). Standard of living and disability in Cambodia. The Journal of Development Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1528349.

Raut, L. K., Pal, M., & Bharati, P. (2014). The economic burden of disability in India: Estimates from the NSS data. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2432546.

Saunders, P. (2007). The costs of disability and the incidence of poverty. Australian Journal of Social Issues,42(4), 461–480. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1839-4655.2007.tb00072.x.

Sen, A. (2004). Disability and justice. Address to the Disability and Inclusive Development: Sharing, Learning and Building Alliances Conference, Washington, DC.

She, P., & Livermore, G. A. (2007). Material hardship, poverty, and disability among working-age adults. Social Science Quarterly,88(4), 970–989. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2007.00513.x.

Tibble, M. (2005). Review of existing research on the extra costs of disability. Working Paper No. 21, Department for Work and Pensions, Leeds, UK: Corporate Document Services.

TurkStat (2011). 2011 Population and housing census. (Publication No. 4029). Ankara, Turkey. Retrieved from https://www.ailevecalisma.gov.tr/media/2618/nufus-ve-konut-arastirmasi-engellilik-arastirma-sonuclari.pdf.

Vyas, S., & Kumaranayake, L. (2006). Constructing socio-economic status indices: How to use principal components analysis. Health Policy and Planning,21(6), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czl029.

Wilkinson-Meyers, L., Brown, P., McNeill, R., Patston, P., Dylan, S., & Baker, R. (2010). Estimating the additional cost of disability: Beyond budget standards. Social Science and Medicine,71(10), 1882–1889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.019.

Wood, C., & Grant, E. (2010). Counting the cost. London: Demos.

Wooldridge, J. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Xiaolin, W., Liping, X., Xiaoyuan, S., & Ping, G. (2011). Extra costs for urban older people with disabilities in Northern China. Social Policy and Society,10(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746410000412.

Zaidi, A., & Burchardt, T. (2005). Comparing incomes when needs differ: Equivalization for the extra costs of disability in the U.K. Review of Income and Wealth,51(1), 89–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.2005.00146.x.

Funding

This study was not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Egemen İpek has no other conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

İpek, E. The Costs of Disability in Turkey. J Fam Econ Iss 41, 229–237 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-019-09642-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-019-09642-2