Abstract

Research-practice partnerships (RPPs) are emerging as a promising approach for educational change by closing the gap between educational research and practice. However, these partnerships face several challenges, such as addressing cultural differences as well as relationship-building in a historically unbalanced relationship between researchers and practitioners. Scholars have argued that these cultural differences, also called boundaries, have learning potential if approached constructively, but that we need to know more about what characterizes them in an educational context. The aim of this study is to contribute to our understanding of frameworks for RPPs. By analysing 45 hours of video recordings from meetings in an RPP between four researchers and 300 practitioners, the study offers a characterization of seven different boundaries organized into three different boundary themes: a) prerequisites for collaboration, b) collaborative practices, and c) collaborative content. Moreover, the different boundaries affect the positioning of different actors in the RPP. For example, depending on the boundary expressed, teachers are positioned as either flawed implementers or co-inquirers. We argue that the boundaries and different participant positions within the RPPs they reinforce may affect their learning potentials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research-practice partnerships (RPPs) are argued to be a promising way to approach reform and change efforts in education aimed at reducing the gap between educational research and practice (Coburn & Penuel, 2016; Datnow, 2020). RPPs can be defined briefly as “a long-term collaboration aimed at educational improvement or equitable transformation through engagement with research” (Farrell et al., 2021a, p. 5). Despite the promise of these kinds of partnerships, there are several challenges associated with creating and sustaining them. Challenges include, for example, scheduling and competing with other initiatives (Donovan et al., 2021) and actively engaging a variety of participants (Akkerman & Bruining, 2016). In particular, the challenges posed by cultural differences between researchers and practitioners play a key role in determining the success of a partnership (Cousins & Simon, 1996; Denner et al., 2019). These differences have also been called boundaries (Akkerman & Bakker, 2011; Kerosuo, 2001). Note that boundaries are not only challenges but also have the potential for learning, making them a critical element of RPP change efforts (Akkerman & Bakker, 2011; Davidson & Penuel, 2019). In other words, differences, depending on how they are negotiated, can either become an obstacle that delays or closes down RPP work or a boundary that can be navigated and negotiated, thus with learning potential (McWhorter et al., 2019). Thus, boundaries have been placed at the forefront in frameworks trying to characterize mechanisms of learning in educational RPPs (e.g., Farrell et al., 2022; Penuel et al., 2015; Wegemer & Renick, 2021; Yamashiro et al., 2023). However, more empirical studies that can refine and develop these frameworks are needed (Farrell et al., 2022).

Previous research has contributed important knowledge on boundaries in RPPs by, for example, examining the processes, people, and objects that operate at the boundaries (Millward & Timperley, 2010; Sjölund et al., 2022a, 2022b; VanGronigen et al., 2022) as well as the learning potential of boundaries (Akkerman & Bakker, 2011; Andreoli et al., 2020; Kerosuo, 2001). Some studies (e.g., Akkerman & Bakker, 2011; Wegemer & Renick, 2021) have offered general definitions of boundaries, but we do not know of any study that has characterized boundaries based on empirical data from actual RPPs. Thus, the aim of the present study is to contribute to recent frameworks for understanding RPPs (e.g., Farrell et al., 2022) by examining and characterizing the boundaries expressed in different meetings between researchers and practitioners during a large-scale educational RPP involving four researchers and 300 practitioners. In light of our findings, we discuss how different kinds of boundaries position actors in RPPs in different ways, which in turn can limit or facilitate the learning potential of RPPs. This is important, as it has been argued that researchers in RPPs entering into collaborations have a historically authoritative position in relation to teachers and that this imbalance in authority can produce discontinuities and undermine the mutuality of RPP work (Penuel et al., 2016).

Background

Research-practice partnerships

RPPs have been defined as long-term systematic efforts made by researchers and practitioners in collaboration to improve schools and school systems through research (Coburn et al., 2013; Farrell et al., 2021a). Specifically, there are five principles distinguishing RPPs from other kinds of collaborative research and improvement efforts (Farrell et al., 2021a). The first principle states that RPPs are long-term collaborations that transcend a single scope of work and allow the partnership to evolve through several stages. The second principle outlines that RPPs work toward educational improvement or equitable transformation. The third principle entails that RPPs engagement with research is a leading activity in the sense that it is a central activity bringing partners together. The fourth principle mandates that RPPs are intentionally organized to bring together a diversity of expertise for the sake of accomplishing the goals of the partnership. Lastly, the fifth principle is that RPPs employ strategies to shift power relations in research endeavours to ensure all participants have a say.

A review of research on the outcomes and dynamics of RPPs (Coburn & Penuel, 2016) showed that interventions created through RPPs are more useful (than non-RPP interventions) to practice organizations and improve students’ results, as well as that RPPs provide greater access to and use of research for practitioners. Further, engagement in RPPs has been found to improve both practitioners’ abilities to use research and researchers’ skills in conducting research of relevance to educational practice (Farrell et al., 2018). Compared to a national sample, district leaders engaged in RPPs were found to use research differently, as they tended to use research methodology more. Moreover, the national sample of leaders was more likely to use research to motivate already-made decisions. As such, there are several promising aspects of RPP work, which is why it is considered a good way to organize reform efforts (Datnow, 2020).

However, despite their potential, there are several challenges associated with creating and sustaining RPPs. For instance, participants in RPPs may experience difficulty in dealing with resources, quality rules, and audiences from different contexts, as well as conflicting positions when actors from different organizations collaborate (Akkerman et al., 2013). Specific challenges for researchers include a conflict between focusing on an academic career by publishing papers and creating actionable products for policy and practice, which might take time from writing and getting published (Gamoran, 2023). Similarly, practitioners engaged in RPPs face challenges, including leadership turnover and school board priorities, as well as trying to convince influential funders (Klein, 2023). Overall, the challenges identified in RPPs have been related to three areas: (1) turnover of individuals involved in RPPs, (2) differences in researchers’ and practitioners’ timelines and incentives, and (3) engaging those with authority to act on RPP findings in active positions in RPPs (Farrell et al., 2018). In particular, these challenges derive from cultural differences and/or power dynamics between the research and practice communities, factors widely regarded as pivotal to the effectiveness of RPPs (Cousins & Simon, 1996; Denner et al., 2019). For instance, Denner et al. (2019) employed a critical research approach to examine the challenges emanating from power dynamics and culture disparities within the development of RPP. One challenge their study identified is the divergent views of what constitutes an equitable partnership. and therefore, they stress the need for RPP participants to engage actively with the dynamics of racialized, classed, gendered, colonizing power dynamics, which can be done with explicit attention to researchers’ social location. Without such deliberate consideration, RPPs may fail to uncover these underlying power dynamics, potentially perpetuating their influence without being addressed.

To overcome the aforementioned challenges, and given the rapid growth of RPPs, scholars have advocated for developing theories that assist practitioners in understanding the design of high-quality RPPs and their operational dynamics (e.g., Farrell et al., 2022). In this regard, a promising approach has been proposed: the idea of viewing RPPs as joint work at the boundaries (Farrell et al., 2022; Penuel et al., 2015).

Research-practice partnerships as joint work at the boundaries

The work done in RPPs has increasingly been depicted as joint work at the boundaries (e.g., Akkerman & Bakker, 2011; Farrell et al., 2022; Penuel et al., 2015). More specifically, frameworks organizing our understanding of RPPs are based on the idea that partner organizations meet at the boundary and navigate collaboration through a boundary infrastructure. For example, in a recent effort to create a conceptual framework for understanding RPPs, Farrell et al. (2022) focused on the objects, people, and processes that operate at the boundary (i.e., boundary infrastructure) and that are required for the RPP to progress. As we will elaborate on below, research on boundaries is increasing, and we know more about their learning potential (e.g., Akkerman & Bakker, 2011; Akkerman & Bruining, 2016), the people, and the objects and practices at the boundaries (e.g., Millward & Timperley, 2010; Sjölund et al., 2022a), however, less about the boundaries themselves.

Boundaries and their learning potential

In education, as well as in health care, researchers interested in boundaries have put increasing effort into investigating their learning potential (e.g., Akkerman & Bakker, 2011; Akkerman & Bruining, 2016; Kerosuo, 2001). In a review of existing research on boundaries, four learning mechanisms were identified: (1) identification, which constitutes becoming aware of the diverse practices at play in the RPP; (2) coordination, which constitutes the coordination of exchanges between partners; (3) reflection, which constitutes expansion of perspectives; and (4) transformation, which constitutes the development of (new) collaborative practices (Akkerman & Bakker, 2011). These learning mechanisms have been found to work both between organizations (institutional level), between individuals in different organizations (intrapersonal level), and within a single person active in multiple organizations (interpersonal level; Akkerman & Bruining, 2016). The presence of learning varied at different levels, and while coordination was present at all levels, transformation seemed to occur only at the intrapersonal level, years after the coordination. The intrapersonal level is particularly concerned with the roles and positioning of actors within the RPP.

People, objects, and practices at the boundaries

Other studies have focused on the people, objects, and practices that take place at the boundary between research and practice. For example, the use of research as an object at the boundary has been recognized (Sjölund et al., 2022b), and organizing collaboration around such boundary objects has been found to support those working at the boundary (Penuel et al., 2016). Another object that spans the boundary between research and practice is the research agenda, which has the potential to gather researchers and practitioners by balancing their respective priorities and aims into something coherent, thus supporting an effective RPP (Meyer et al., 2023).

Moreover, paying explicit attention to and implementing specific practices that span the boundaries between organizations have been recognized. For example, such boundary practices have been found to increase the learning potential of whole organizations and improve learning outcomes for at-risk students (Millward & Timperley, 2010). However, to facilitate equitable meaning-making processes across boundaries, it has been argued that teachers, who are traditionally placed in positions with relatively low authority, need to engage in a meaning-making process of their own, the goal being to give them the confidence to participate fully (VanGronigen et al., 2022).

In addition, researchers have investigated boundary spanners, who are individuals working at and crossing the boundaries between research and practice (e.g., Farrell et al., 2019; Mull & Adams, 2017; Wentworth et al., 2021). This is critical because, to work effectively, researchers and practitioners must find new roles (Tseng et al., 2017) and ways of acting (Tseng et al., 2018) that relate to each other. These studies have highlighted the variety of roles that researchers and practitioners assume (see further Sjölund et al., 2022a) and emphasized the importance of active co-construction of knowledge and sense-making between researchers and practitioners in promoting the utilization of research in practice (Brown & Allen, 2021; Cousins & Simon, 1996; Farrell et al., 2021b). Additionally, to address the challenges encountered in RPPs and achieve more equitable partnership practices, promising adaptations that boundary-spanning researchers can implement exist (Denner et al., 2019; Ishimaru & Takahashi, 2017). Denner et al. (2019) suggest that boundary spanners should establish a shared understanding of equity in the partnership, align with the priorities of their practice partner, actively listen and respond to build relationships with practice partners across different levels of the organization, critically review the research focus and questions, and transition from a task-oriented approach to one that also includes a focus on norms, culture, and values.

Similarly, Ishimaru and Takahashi (2017) argue that when confronted with racial, cultural, and class differences, participants can engage in collaborative activities to expand identities and interactions. These activities may involve reframing expertise, examining and addressing contradictions, and attending to power and relational dynamics. By applying these strategies to navigate across boundaries, both researchers and practitioners can have the potential to instigate transformation within broader institutional systems and advance towards more equitable practices in research and improvement endavours. Nevertheless, to navigate boundaries effectively, a deeper understanding of the specific boundaries that arise in educational research-practice partnerships is essential.

Characterizing boundaries in research-practice partnerships

Although research on boundaries is increasing, and we know more about the people, objects, and practices at the boundaries (e.g., Millward & Timperley, 2010; Sjölund et al., 2022a), as well as their learning potential (e.g., Akkerman & Bakker, 2011; Akkerman & Bruining, 2016), less attention has been paid to characterizing the boundaries themselves. Boundaries are commonly described, with some differences, as the intersection of the perspectives or worlds of different cultures (e.g., Akkerman & Bakker, 2011; Farrell et al., 2022; Kerosuo, 2004). More specifically, the boundary concept can be used to understand how differences constitute a context in which meaning can be negotiated, as well as the continuities and discontinuities that are experienced in encountering these differences (Penuel et al., 2015). In a review of the objects and people at the boundaries in educational change efforts, Akkerman and Bakker (2011) suggested that boundaries are ambiguous in nature. Boundaries belong to both one world and another, and as such, both divide and connect different worlds. This ambiguity of boundaries is characterized by multivoicedness, in that participants are identified as belonging to both sides of the boundary, and by an unspecified quality, as participants are identified as not fully belonging to either side. For instance, a teacher working as a co-researcher in an RPP can be seen as both a researcher and an educational practitioner. As such, this teacher can be excluded from both the researcher and practitioner communities when interpreted as being neither a “true” researcher nor a “true” practitioner. Similarly, the teacher, carrying out the tasks of both communities, could be interpreted as included in both the researcher and practitioner communities. As a result of the ambiguous and multivoiced quality of boundaries, they are dialogical in the sense that a multitude of meanings are negotiated. Moreover, this negotiation of meanings might serve to create something new, and it is here we see the learning potential of boundaries.

The above definitions of boundaries are, however, broad and do not address the question of the specific boundaries met by actors in RPPs and that create discontinuities in practice. Some work addressing this question has been conducted in health care (e.g., Kerosuo, 2004) and economics (e.g., Hernes, 2004). However, to our knowledge, no previous studies in educational research have offered a characterization of different boundaries based on empirical data from actual RPPs. Such work could help us better understand the frameworks and conceptualizations of RPPs as joint work at the boundaries (e.g., Farrell et al., 2022), as well as inform those invested in collaborative efforts in practice. Hence, we investigate a large-scale RPP in education with the aim of contributing to our understanding of recent frameworks for RPPs by examining and characterizing boundaries that emerge in meetings between researchers and practitioners.

Method

In this section, we first describe the context of the study, specifically detailing the structure, processes, and participants of the programme. Following this, we describe the data collection and analysis process of the study, with a particular focus on how the boundaries in the data were identified using four markers. Last, we describe the limitations of the study to illuminate aspects that fall outside the scope of this study.

Context of the study

The case investigated in the present study is a large-scale, collaborative research and preschool improvement programme on sustainable development carried out in Sweden. The purpose of the programme is to develop long-term and research-based ways of working with education on sustainable development in preschools, the intention being to strengthen children’s learning about the subject. This is achieved through collaboration and co-construction of knowledge between preschool practitioners and researchers. Three types of organizational entities are involved in the programme: academia (i.e., researchers), educational practice (e.g., preschool teachers, principals, and district office employees), and a non-profit independent research and improvement institute that works to stimulate practice-oriented research in the field of education. The programme is spread across nine municipalities and private school authorities in Sweden and includes 300 educational practitioners, one institute representative with responsibility for programme coordination, and four researchers of which one is the first author of this article.

The first author was, after asking for permission, invited by the other three researchers to participate as an observer in the programme, primarily due to the first author’s interest in RPPs. The first author acted as external observer of the programme based on an interest in investigating RPPs and did not participate with the other three researchers in program activities such as programme planning and school improvement work. However, to build and maintain trust with the programme participants, the judgement was made that interacting with participants to some degree was necessary, for example by introducing himself and his research interest, and answering questions when specifically asked for his views on matters under discussion. This balance was maintained to reduce biases, effect on the programme, and presence in meaningful coding segments. In the process of coding the data material for this study it became apparent that none of the (few) utterances of the first author during the meetings touched upon the subject of boundaries, which is the focus of this study. Additionally, the second author was not involved in the project at all and, as such, could provide a critical perspective on the work of the first author.

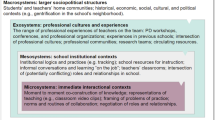

The programme itself is organized in a cyclic pattern of three types of meetings (as illustrated in Fig. 1): board meetings, process manager meetings, and improvement seminars. In the board meetings, district office preschool leaders and researchers discuss decision-making regarding the direction of the programme. In the process manager meetings, preschool improvement leaders and researchers discuss questions concerning how to help the local improvement groups to spread results, knowledge, and experiences in their context. The improvement seminars, involving all programme participants, consist of lectures, group discussions, and work on relevant topics, the goal being to facilitate improvement in sustainable development education. Data collection from board meetings, process-manager meetings, and improvement seminars was conducted by the first author of this study.Footnote 1

The programme, in a theoretical sense, conforms to the five principles of an RPP, as delineated by Farrell et al. (2021). Firstly, consistent with RPPs are long-term collaborations, despite operating within a time-bound grant framework, program partners acknowledged the importance of post-program engagement in the sense that, even though funding ends, they aim to pursue research and improvement activities to keep learning and improving sustainable development education in preschools. Secondly, the program corresponds to RPPs work toward educational improvement or equitable transformation through the program’s overarching goal of enhancing sustainable development education in preschools. Thirdly, the program explicitly places research at the forefront, which conforms to RPP principle of ensuring an engagement with research as a leading activity. The first phase of their research involved scoping results through surveys and observations. The subsequent phase was characterized by iterative research and improvement. Municipal and private school entities were empowered to select focal areas for improvement based on survey and observation results, with some centralized guidance. Improvement seminars facilitated collaborative learning among preschool educators, catalyzing knowledge exchange based on research efforts for enriched learning. Fourthly, these research and improvement processes also indicates a deliberate effort to harness diverse expertise and as such adhere to RPPs are intentionally organized to bring together a diversity of expertise. Lastly, consistent with the last principle that RPPs employ strategies to shift power relations in research endeavours to ensure all participants have a say, the program made efforts to strategically shift power dynamics. For instance, an educational leader assumes the role of board chair to exert ultimate funding control. Furthermore, an institute representative may act as a neutral facilitator, persistently prompting discussions on researcher-practitioner roles.

To foster mutual comprehension, agenda items set by the institute representative for board and process manager meetings routinely outline role expectations, subsequently subject to negotiation for shared alignment. However, it is worth noting that, while the programme is characterized as an RPP in theory, this does not necessarily mean that the principles are fulfilled in practice, a question we will return to when discussing the study’s results.

Data collection and analyses

The data for the present study consist of video-recorded observations and transcripts of the three types of meetings within the programme. The data were collected from autumn 2022 to spring 2023. In total, we collected about 45 hours of video-recorded meetings: 15 hours of board meetings, 18 hours of process manager meetings, and 13 hours of improvement seminars. Most of the data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic and, as such, constituted digital meetings and seminars conducted via Zoom. The video recordings present an opportunity to gain in-depth insights into the interactions between researchers and practitioners, which is rare in research on collaborative programmes in education (Coburn & Penuel, 2016). To anonymize extracts from the data, we use non-specific terms, such as researcher and process manager. When names are presented in quotes, they are fictive.

In the data analysis, we set out to identify the boundaries that were expressed in the programme meetings. Our analysis of boundaries is influenced by two primary sources. First, we draw on Akkerman and Bakker’s (2011) definition of a boundary. They define boundaries as a “[…] difference leading to discontinuity in action or interaction” (p. 133). However, the definitions and frameworks presented by Akkerman and Bakker (2011) provide little support regarding how to identify boundaries in the data. Therefore, we also borrowed concepts from studies in health care. More specifically, we were inspired by Kerosuo (2004) in utilizing markers to identify boundaries. Kerosuo (2004) explicitly described how boundaries can be traced through four different kinds of verbal markers that serve as fragile signals in social interaction. Below, we describe these markers together with examples of how the different markers were identified in the data.

The first marker is “use of the word boundary or synonym”. This marker was not found in the data.

The second marker is “metaphors of boundaries (such as fences, walls, limits)”. For example, the quote below describes how preschool teachers felt they were the research subjects rather than being seen as co-inquirers; they described the boundary using the metaphor of two parallel tracks that do not connect. The metaphor itself is written in italics.

Because for me when I think about, ehm…”me being a research subject” … The input where you feel you’re being researched on, then I think that it’s probably more based on this feeling that you’re running on two parallel tracks…

The third marker is “actors’ attributes and definitions of social relations (we vs. they)”. This marker is also exemplified in the same discussion as above, as a separation of different perspectives between actors was present as well. The key parts of the markers in the quote are written in italics.

I also think about this “being researched on” part, I recognize it a bit. Yes, not everything in the presentation, but most of it is in line with my picture of those days as well. But specifically that part, I think it is what we navigate around all the time here. That from my preschool teachers, I got that it doesn’t really connect for them. They don’t think that this task has… is something that has sprung from the needs of practice, and this is something we need to improve or that it has been clear that this is something that researchers would like to look at to get a foundation to reflect on.

The fourth marker is “references to different locations”. In the data, this maker is generally seen in the form of the municipality, preschool, or practice in contrast to the research context. For example, in the quotes below, this is exemplified by referring to different expertise and/or practices in schools and universities.

And that becomes a question of planning, that the programme board will discuss if you have two days and finally meet live, how do we use that time, and we have many, both ourselves and colleagues, research colleagues that we can suggest how they can lecture on their area of expertise at the seminars, but that there are examples from practice, I think that’s great as well, but when that is, will come up in the planning of the seminar itself.

How do we get back from… and we miss a lot of the things we bring up, and we have also raised that you need to have a dialogue so that we know what happens in the municipalities. Because we don’t have a clue about that really.

Concerning the coding process, the first author began by conducting an initial coding of eight hours of the material, identifying boundaries using the above four markers. Transcripts of the identified boundaries were then sent to the second author. These transcripts were discussed together and categorized into different types of boundaries, inspired by the process of content analysis (Weber, 1990). Each boundary was categorized according to its content. For example, the following quote was coded as “Principals want more from researchers.”

What we have heard some voices about is that people are probably a bit keen to get more from research, that based on the send-outs that the researchers have distributed. But I think that the time is limited and that there will be more. But it was something like that. They wanted more meat on the bones regarding research, but that will probably come.

The process of identifying instances of boundaries and jointly coding them according to their content was iterated on the entire dataset. The coding was then grouped together according to their content, resulting in a total of seven different kinds of boundaries organized across three themes.

Limitations

The present findings must be interpreted considering the limitations of the study. First, most of the data that constitute the empirical material for analysis were collected during a global pandemic, which probably affected how the research and improvement programme was conducted. For example, most data were collected from an online meeting platform rather than physical meetings. This may have influenced the way in which relationships took shape and the way in which discussions were conducted.

Second, during the improvement seminars, preschool teachers were sent out to discuss in small groups with each other. We were not able to record these discussions, potentially missing out on valuable data. For example, during the other parts of the improvement seminars, preschool teachers did not speak much, meaning that the data mainly consisted of utterances from the other actors participating in the programme. However, the other actors (mainly principals) continuously referred to what their preschool teachers had said about the programme in forums other than the formal meetings. This means, however, that preschool teachers’ perspectives were interpreted using second-hand information. Future research following an RPP could collect more data on teachers’ first-hand perspectives.

Results

Our characterization of boundaries delineates seven different boundaries organized into three main themes based on boundary content (see Table 1): collaboration prerequisites, collaboration practices, and collaboration content.

Additionally, we also identified if it was a preschool leader, preschool teacher, or researcher who mentioned the respective boundaries and how often these occurred in data. For instance, preschool teachers were only found to be the actors in two cases of boundary identification. For the interested reader, a complementary table to Table 1 with frequencies for actors and boundaries is presented in Appendix 1. The sections below provide descriptions of the three themes of boundaries, detailing their characteristics and describing the specific boundaries included in each theme.

Boundary on collaboration prerequisites

The first theme concerns boundaries that are expected to emerge owing to insufficient collaboration prerequisites. One boundary was identified in relation to this theme.

Boundary 1–Insufficient skills and understanding of key concepts

The boundary identified in this theme is represented by quotes on how certain actors in the RPP lack sufficient skills and knowledge, which makes it more difficult to achieve the programme's goals. Specific to this boundary is that the people described as having insufficient skills and understanding are largely the participating preschool teachers. Moreover, those identifying this as a boundary are most often not the teachers themselves but other actors within the RPP. In particular, preschool teachers’ a) understanding of the key concept of sustainability, b) linguistic skills, and c) scientific skills are brought forth as boundaries.

First, concerning the understanding of the key concept of sustainability (the main content of the RPP), one researcher, after having analysed survey data from preschool teachers in the programme, reported that most participating preschool teachers lacked the global perspective on sustainability held by researchers.

And what we do not see, or what we see little of, is that there are very few examples of the global aspects. And that if you remember my first slide… or this with the (state) curriculum, then there is both this long-term and global perspective, but we see very little of the global, and that is a challenge… (Researcher)

As indicated in the quote above and from the researchers’ perspective, researchers and preschool teachers view the key concept of sustainability differently. Moreover, the researchers’ view of the concept is brought forth as the correct one.

A second aspect of the boundary concerns preschool teachers’ insufficient linguistic skills, such as skills to read and understand complex (sometimes scientific) texts. For example, the use of an observation protocol as a tool for preschool teachers instigated a discussion on preschool teachers’ linguistic skills. Both researchers and preschool leaders described a lack of teachers’ linguistic skills needed to assimilate the scale and use the protocol properly.

But we also raised this… that I think that Inger mentioned. The difference in linguistic skills and ability, and to assimilate the scale among all participants and that the principals need to take a responsibility and grasp this, that all co-workers can actually assimilate the scale in a good way. (Process manager)

As in the quote on sustainability, the preschool teachers are again described as actors with insufficient knowledge or skills. In the same discussion, one process manager described an e-mail from a preschool teacher that stressed the lack of linguistic skills among preschool teachers at the preschool to understand the observation protocol;

There was one where I got an e-mail from a preschool teacher who wondered, what I am supposed to do… The staff at my preschool, they don’t understand the observation protocol, they’re not linguistically skilled enough. (Process manager)

The description of preschool teachers as not “skilled enough” indicates a boundary relating to insufficient skills. This time, however, preschool teachers’ lack of linguistic skills is described by preschool teachers,Footnote 2 as well as by researchers and preschool leaders.

The third aspect of the boundary relates to preschool teachers’ scientific skills. This was particularly apparent when the observation protocol was given to preschool teachers and they had trouble using it properly. Several process managers and board members mentioned that preschool teachers were having a hard time using the protocol and were unsure regarding how to rate different aspects of sustainability in their department. Preschool teachers, process managers, and board members all expressed a worry that preschool teachers would either over-rate or under-rate their practice.

And then when it comes to the rating (observation protocol), we experience a bit of a problem with the fact that it might not be honest. This… kind of room for interpretation that leads to you perhaps wanting to give yourself high ratings so that if we think like this, then we do this. (Process manager)

The process managers, in the discussion following this quote, expressed a concern that this discontinuity would limit the growth of the programme and that preschool teachers would not learn from the experience.

Boundaries on collaboration practices

The second theme concerns boundaries on both perspectives on collaboration practices and how actual collaboration practices may play out. The theme includes three boundaries: lack of support in understanding key concepts and skills, different role expectations, and lack of information exchange.

Boundary 2–Lack of support to develop key skills and understanding of key concepts

In contrast to the previous boundary on insufficient understanding and skills, this boundary was less commonly expressed and focuses more on the lack of support that the programme offers preschool teachers related to developing their understanding and skills, instead of just stating that teachers lack the necessary understanding and skills. This lack of support is mainly expressed by preschool leaders (i.e., board members and process managers). For instance, one process manager expressed the need for his preschool teachers to also become researchers in their own practice when he talked about how preschool teachers needed to be given support concerning scientific inquiry. This perspective implies a perceived deficiency in the existing support system:

We have to accept that now it is about them playing around a while, but then there will be more… kind of... regarding education, the concepts of knowledge, learning, how can you investigate concepts scientifically, because it is this scientific approach that I feel like… here my preschool teachers need a bit more knowledge and, this “how”… kind of…, how do you formulate a limited area? How do you follow up? How… how do you analyse? How do you see the effect of this? Tools are required for this, or else it just becomes, well, I’m afraid that it will become well… I discovered that the economic dimension got the lowest value… (Process manager)

Moreover, similar to the researcher describing preschool teachers’ lack of a global perspective in the previous boundary, this process manager also depicted the preschool teacher as having the wrong or insufficient understanding of this key concept, as evident from the paraphrasing previous to the quote, although now more focus is on supporting a change in understanding a key concept.

Boundary 3–Different role expectations

Another boundary on collaboration practices concerns participants’ different role expectations. For instance, preschool leaders expressed a wish to be challenged more by researchers, wanting researchers to contribute their knowledge and expertise in group discussions. This is a boundary in the sense that researchers had a different view of their roles, in that they had not prioritized getting involved in group discussions in the way that preschool leaders expressed a need for. One process manager described this in a discussion on the researcher role in the programme.

We can pitch in there, and, precisely that we in our groups get researchers in to widen our perspectives, kind of, based on… well… theories, ways of working, methods, to invigorate us, challenge us also a little bit because I think that, as a process leader, you have a role in knowing about these things when you get back home and work locally. We were very much in the “how” and not so much in the “what” perhaps, but the “how” and that we invigorated each other, but that we also do that based on the theories that exist. That we can tie things to the research more clearly and widen perspectives… (Process manager)

In the quote above, it is apparent that there is a boundary in how the researcher's role is perceived differently by researchers and preschool leaders. The process manager describes a need to move towards a relationship between researchers and practitioners with more dialogue, allowing them to learn from each other, something that is not happening at the moment. In other words, preschool leaders reported wanting to see a shift in the role structure to make researchers and preschool leaders act more as partners.

Similarly, there are different expectations regarding the researcher's role in the relationship between researchers and preschool teachers. This was expressed by a board member in a discussion that emerged when preschool teachers indicated in a survey that they felt “researched on”, rather than being part of the research effort.

I also think about this feeling of “being researched on”, I recognize it a bit. Yes, not everything in the presentation, but most of it is in line with my picture of those days as well. But specifically that part, I think that is what we are navigating around all the time here. That from mine (preschool teachers) I got that it doesn’t really connect for them. They don’t think that this task has… is something that has sprung from the needs of practice, and this is something we need to improve or that it has been clear that this is something that researchers would like to look at to get a foundation to reflect on. Instead, in a way, they (preschool teachers) experience that all the lectures and all this is kind of one part and then the research kind of ends up on the side in some way. So I think that we perhaps need to tie this together, isn’t that what this whole day partly is about, if I understand it correctly. (Board member)

The board member mentioned that preschool teachers felt they were the research subjects rather than being an active part of the research endeavour. The board member further reported that, because of this, preschool teachers experienced the research effort as something on the side, not really a part of the programme. Based on this, the board member also argued that research and practice need to be tied together more clearly.

Boundary 4–Lack of information exchange

Finally, the theme of collaboration practices also includes a boundary concerning the lack of information exchange. In particular, there was an expressed lack of exchange between researchers and preschool leaders. For instance, discussions were held in both board and process manager meetings regarding the fact that the current practices do not allow preschool leaders to receive enough information prior to improvement seminars.

Then I think that it’s important that we can reflect and think aloud together, be able to reason, bring different perspectives into the discussions. Then we also got into being able to be one step ahead and getting to be a process leader, to get a bit more practical input before the seminars so that you can go home to your organization and prepare them a little bit on… This will happen when we meet next time. Because now we are at the stage, everyone at the same time. (Process manager)

In this quote, one process leader expressed a desire to receive more information at an earlier stage, to be one step ahead of the programme, which is one aspect of the lack of information exchange. A second aspect of this boundary is that preschool leaders also felt the current practices did not allow them to provide enough input on the tasks given to preschool teachers and principals at improvement seminars. In the following quote, this is illustrated in the context of a task that was introduced that had not passed the board members.

Then it was the part about the confusion that was at the end. I don’t know… you did not bring it up IFOUS1, but it kind of hung there as a big part that was neither brought up in the programme board nor the process manager group and this I think we should avoid because it doesn’t turn out well. Among other things, it was about this vision that was supposed to be created and … that didn’t land very well. It became a weird ending where everyone got really confused… (Board member)

The last aspect of the boundary, lack of information exchange, reflects the fact that both researchers and practitioners reported a lack of information exchange regarding knowledge of how other organizations work and structure their day-to-day work. For example, researchers expressed their lack of knowledge about local practice organization:

When, well, I think that one of the problems… But Ron will give an account of our discussion, but this that we were discussing, that you don’t really know what is the programme and what is research and what.. kind of… how… How do we get back from.. and we miss a lot of the things we bring up, and we have also raised that you need to have a dialogue so that we know what happens in the municipalities. Because we don’t have a clue about that really. (Researcher)

In the discussion, it was concluded that lack of knowledge was caused by an insufficient information exchange between practitioners and researchers. For instance, the researcher stated that they had no knowledge of what happens in the municipalities and that this kind of dialogue had been missing.

Boundaries on collaboration content

The boundaries in the third and final theme address discontinuities regarding the content of the collaboration. We identified three boundaries in this theme: “Different understandings of key concepts and skills”, “Different views on appropriate content level”, and “Different views on what the central content is”.

Boundary 5–Different understandings of key concepts and skills

In the boundary “different understandings of key concepts and skills”, there are inherently different views on or knowledge about skills and what the programme’s key concepts entail. In contrast to the boundaries “insufficient understanding of key concept and skills” and “lack of support to develop key concept and skills”, this boundary is not described as preschool teachers having incorrect understandings and being in need of support. Instead, it is put forth that different actors have different understandings without necessarily (or definitely) pointing to a “correct” understanding.Footnote 3 In particular, there were different understandings concerning three aspects: the key concept of sustainability, teaching and student learning, and key linguistic skills.

First, regarding the key concept of sustainability, both researchers and process managers described how preschool teacher participants tended to separate the different dimensions of sustainable development. Both researchers and process leaders also mentioned that they would rather employ a holistic view of sustainability, as described in the quote below from a researcher.

Yes, and that is the point, to tie them (the dimensions of sustainability) all together and to see it holistically, and not as separate parts as they (other participants) very much do now. (Researcher)

After this, another process manager agreed that it is easy to slip into considering the dimensions of sustainability as separate parts, and even though the process managers might be able to view things as a whole, they are worried that the principals and preschool teachers might not. In addition, one researcher indicated that preschool teachers view sustainable development as mostly pertaining to environmental issues, which is also radically different from the holistic view of sustainable development held by process managers and researchers.

Because this isn’t a new instrument, but has been used a few times, so we know that if you use the scale, you suddenly realize that sustainable development is a bit broader. If you, from the start, as several others have mentioned, perhaps relate to the environmental dimension, you see that sustainable development has more areas. In every dimension there are several areas and, for instance, we have the area ‘Health’, and that has been there since 2014. (Researcher)

Second, there are also different perspectives on teaching and learning, creating a discontinuity. This was primarily apparent in a discussion on pedagogy between process managers and researchers. One process manager asked whether there would be any consideration of or focus on different theories of pedagogy for teaching preschool children about sustainable development, as the process manager had seen tendencies among the preschool teachers to end up in a “transfer pedagogy”. The researchers replied that if we end up in a transfer pedagogy, we have failed. The process manager emphasized that it is important to not be that crass, suggesting that if there are background factors limiting preschool teachers in their pedagogy and resulting in them using a transfer pedagogy, the programme must deal with that. While the researchers agreed with this, consensus was never reached. The process manager wanted a concrete answer to the question of whether the programme was going to work with pedagogical theories in this way, as it was perceived as a great boundary to being able to work well with sustainable development in preschool, and no answer was really given. As such, there are two layers of boundaries here. First, there is the pedagogy of preschool teachers, which might not be suitable for teaching sustainable development. Second, there is the discontinuity in the discussion itself, regarding the importance of working on this in the programme.

Lastly, the linguistic skills aspect previously discussed as lacking among preschool teachers is also present in the form of different understandings between researchers and preschool leaders. This was evident when the use of an observation protocol instigated a discussion between preschool leaders and researchers, where a discontinuity appeared, as they viewed the “linguistic issue” as either an obstacle to learning about sustainability or the programme as an opportunity to learn the language. First, a process manager said:

There was one where I got an e-mail from a preschool teacher who wondered, how I am supposed to do… The staff at my preschool, they don’t understand the observation protocol, they are not linguistically skilled enough. (Process manager)

This entails the view that preschool teachers’ linguistic skills are an obstacle to learning about a sustainable future. Then, in contrast, a researcher said:

My opinion is that you learn a language by putting it in a context and when you are challenged and, kind of what the principle says: Now you have the chance… that here is a practical task where we work with important concepts for preschools. So by participating in this programme, you will acquire better language. That you view it as the process… that you kind of, don’t have to take a linguistics course if you are in this programme, because this programme will challenge you to become better at Swedish, and that you kind of work in that way, because it is a big problem, and we know that this is a big problem that leads to weak equity in the preschools (Researchers)

This describes the view that the sustainable development programme provides an opportunity to deepen preschool teachers’ understanding of the language. As can be discerned, this entails competing takes on the linguistic skills issue, as it is related to the programme whose meaning is being negotiated.

Boundary 6–different views on appropriate content level

A boundary in the form of different views on appropriate content level became apparent in a discussion that took place at a board meeting after the institute representative presented the survey results from the latest improvement seminar. A board member described what he had learned from the preschool teachers in the municipality.

That’s how we’ve reasoned and talked about it in Springvale. I recognize, among other things, that some (preschool teachers) experienced the researchers input in the first part, which was about presenting results… And that there were those who expressed the expectation that this would also be more clearly connected to an analysis of the results in the researchers’ presentation there and also that the other presentations perhaps felt a bit basic, if I can put it like that. (Board member)

This sentiment was shared by several board members, as they mentioned that their preschool teachers experienced the input from researchers as too basic. The researchers themselves, however, felt the level was appropriate, considering that they intended to lay a common foundation for the programme.

Boundary 7–different views on what the central content is

The last boundary concerns different views about what the central content of the programme is or should be. This became a topic of discussion after a board member had received information from co-workers that most discussions had gotten “stuck” on prerequisites. The board member described this:

But what I got hung up on and what we both said (co-workers) was that there might be too much talk about conditions, structure and organization. And the… I think like this… This we really need to help these groups with, because some groups, when we were in the last programme kind of had this approach to the whole programme. They never came out of this and this doesn’t work well, since we want them to have this practice-based pedagogical dialogue with each other, so I don’t know if you can direct this in some way, that kind of, this question is about organization, and then you have kind of, ticked that off, and can move on to this now, the pedagogical aspects or something. Well, I just wanted to put this out there, because it probable looks very different, but now this was at two different levels and they both had this reflection. (Board member)

Evident is that the preschool teachers chose to talk about prerequisites or differences in conditions during the improvement seminars and avoided other topics that one board member saw as more critical to the programme. Another board member agreed that this was important to monitor as well as to ensure that they would move on from discussing prerequisites to other topics, for instance, theoretical backgrounds or different stances on teaching.

Discussion

In the present study, we set out to contribute to recent frameworks for RPPs in education (e.g., Farrell et al., 2022) by examining and characterizing boundaries expressed in different meetings during a large-scale research—and improvement programme. More specifically, we constructed a typology of seven different boundaries divided across three overarching themes: collaboration prerequisites, collaboration practices, or collaboration content. Based on our results, we argue that the different boundaries create momentary positions for actors in RPPs in different ways, which in turn can limit or facilitate their learning potential. This is important to discuss considering the arguments that the historically authoritative role of researchers in collaboration projects may undermine the mutuality of RPP work (Penuel et al., 2016), and that there is a need to further investigate what roles researchers and practitioners could assume in order to avoid confusion and ambiguity regarding each partner’s contribution (Farrell et al., 2019). More specifically, we argue that the different characteristics of the boundaries detected in this study implicitly position the programme participants in different ways. We discuss this in relation to the three themes of boundaries found in the present study and argue that the boundaries within the themes position the actors while also negotiating more continuous roles in different ways.

First, in the theme collaboration prerequisites, preschool teachers were treated as the objects, with researchers and preschool leaders being the subjects. More specifically, preschool teachers were depicted by researchers and preschool leaders as having insufficient skills or understanding of key concepts, implicitly positioning them as flawed implementers and the researchers as experts. In contrast, scholars have cautioned those invested in educational change about positioning teachers in this kind of traditional role with limited authority, particularly because RPPs such as this are built on emancipating teachers so that they can play a greater role in change efforts (Datnow, 2020). Other scholars (Farrell et al., 2019; Penuel et al., 2016) have also emphasized the importance of considering historical power relations and authority structures when engaging in multitiered RPPs such as the one studied here. For instance, preschool leaders may unknowingly invoke their authority, which may limit the effectiveness with which an RPP manages to emancipate teachers’ voices. Moreover, researchers’ historically authoritative position in change efforts may also undermine teachers’ voices and limit the mutualism of RPPs. Based on the way in which the characteristic aspects of the theme collaboration prerequisites are constituted through a perspective focused on teachers’ flaws, and while we consider it necessary to address potentially limited perspectives among teachers, we argue that this could serve to undermine the teacher's voice and limit the mutuality as well as learning potential of RPPs. We suggest this specifically because it was mainly others who positioned preschool teachers as flawed implementers, while preschool teachers themselves seemed to want higher-level presentations at improvement seminars.

Second, boundaries in the theme collaboration practices mostly positioned researchers as the objects, with preschool leaders and preschool teachers as the subjects. For example, teachers were still seen as flawed implementers, but at the same time, a wish was expressed for researchers to support teachers in establishing a more equal partnership. For instance, in the boundary “different role expectations”, researchers were positioned as experts, but at the same time there was a wish to move them towards a critical partner and co-inquirers role. Specifically, preschool leaders expressed the need for a closer relationship between researchers and practitioners as well as the need to transform the relative roles between researchers and preschool leaders from the more traditional researcher expert—preschool leader improvement leader to researcher and preschool leader as critical partners. Similarly, concerning the relative roles between researchers and preschool teachers, there was a wish to go from the research expert—preschool teacher implementer to the roles of researchers and preschool teachers as co-inquirers. The movement for researchers and preschool leaders to be more in line with partner roles can also be seen, though implicitly, in the boundary “lack of information exchange”, as both researchers and preschool leaders reported wanting more dialogue to learn more about the respective organizations. There is support in previous research for the notion that lack of information exchange is a critical boundary of RPPs (Penuel et al., 2016), but also that it is not enough to just inform, for instance, researchers about local municipality practices. Instead, in order to adapt to the changing environment in which participants operate locally, a continuous dialogue between researchers and practitioners is needed to be informed about the different contexts. This further enhances the image of researchers and practitioners as (critical) partners in continuous dialogue.

Third, concerning the boundaries in the theme collaboration content, the focus is on different views and understanding of participants, not only expressing a wish for but actually positioning researcher and practitioner knowledge as more equal and as being negotiated for meaning, with practitioners as well as researchers as negotiators. Hence, there are no clear subjects and objects. Both the “critical” and “negotiating” positioning of researchers and practitioners can be seen as aspects enhancing the partner role, forming roles for researchers and preschool leaders as critical and negotiating partners. Importantly, we argue that when the participants get to a point where different meanings are articulated without expressing a lack of or insufficient understanding of something, then the true dialogical nature of boundaries can emerge. This can be exemplified by the three boundaries concerning key concepts and skills (one for each theme). In the first theme, preschool teachers’ insufficient meaning-making in terms of understanding and skills was emphasised. In the second theme, the focus was instead on the lack of support for preschool teachers’ meaning making. While not explicitly positioning preschool teachers as insufficient anymore, they are still seen as the ones who need to be trained. This is not that surprising, or probably not that uncommon, given that research suggests that when researchers and teachers are involved, despite the best intentions of the participants in the RPP, they are likely to face difficulties in democratizing the processes and emancipate teacher voices (Penuel et al., 2016). However, in the third theme, neither teachers nor researchers are depicted as insufficient or in need of training. Rather, the focus is on understanding the different meaning making processes of different participants. This is a setting that, according to Akkerman and Bakker (2011), has the potential to leverage the learning mechanisms that exist in boundaries.

Furthermore, the varied positioning of researchers and practitioners within the three boundary themes underscores the need for programmes that are aiming at being true RPPs to explicity address macro-level and micro-level power dynamics (see also Denner et al., 2019; Ishimaru & Takahashi, 2017). Neglecting this aspect risks reverting to conventional modes of operation, thereby undermining the defining principles of RPPs. For example, in the case of the programme under investigation, it was theoretically classified as an RPP due to its deliberate emphasis on harnessing diverse expertise (Principle 4). However, based on the study results, it could be argued that, in practice, the commitment to shifting power dynamics was inconsistent. This inconsistency was particularly evident in how the characterization of “insufficient skills and understanding of key concepts” positioned preschool educators as flawed implementers. A more proactive role by key stakeholders (e.g., the board chairperson, institute representative, researchers) in engaging in boundary-spanning practices such as rectifying power and equity imbalances may have facilitated boundary navigation.

In sum, the different boundaries momentarily position the actors within the RPP on a continuum from implementers/experts to co-inquirers, and in line with other scholars (Akkerman & Bakker, 2011; Akkerman & Bruining, 2016), we argue that the latter positioning can provide a foundation for roles that have greater potential for learning. Moreover, based on our results as well as arguments from leading scholars in the field (Penuel et al., 2016), we believe that researchers, given their historically authoritative position, have an important role to play in amplifying and emancipating teachers’ voices in order to create a more equitable meaning-making process between researchers, preschool leaders and teachers. In our results, it is evident that the researchers have an authoritative position from which to work on amplifying preschool teachers’ voices. Particularly in the boundaries of collaboration practices, it is evident that researchers are in an authoritative position when, for instance, preschool leaders argue that they would both like more opportunities to give input to researchers’ work and like to receive more information from researchers. As such, it seems that researchers, due to their authoritative position, are particularly important in emancipating teachers’ voices and creating more equitable RPP practices. This could, for example, be achieved in the study described by VanGronigen et al. (2022), who utilized design thinking processes in workshops with educators to surface the meaning-making of current assumptions and beliefs about change. Their results indicate that this process helped redistribute authority more evenly. Hence, when educators had conducted an initial meaning-making negotiation amongst themselves, they were ready to play a more active role in the programme as a whole. A similar process can be found in the process manager and board meetings in our study, where a topic was generally discussed in practitioner groups before engaging in a whole group discussion between practitioners and researchers. However, preschool leaders in the programme were critical to this structure, arguing that researchers should engage in the group discussions to challenge them in their thinking. In large-scale programmes such as this, practical barriers to such structures have been identified, as there were 300 practitioners and four researchers involved, making it difficult to organize and time-consuming for researchers to engage in small group discussions with all practitioners.

Conclusions and future directions

Through an in-depth characterization of seven boundaries expressed during a large-scale RPP, the results of the present study have contributed to our understanding of recent RPP frameworks that view the work of RPPs as work at the boundaries (Farrell et al., 2022; Yamashiro et al., 2023). Moreover, we identify and describe how different boundary characteristics may affect the positioning of actors within the RPP as well as their learning potentials. We urge other scholars to pursue empirical investigations of RPPs in other contexts as joint work at the boundaries and to characterize the boundaries themselves in order to refine the present framework of boundaries further and thereby advance our understanding of the design and mechanisms of learning in RPPs. Specifically, other boundaries may be identified in other RPP contexts. Moreover, the present results highlight how the historically authoritative roles of researchers might limit the mutuality and learning potential of RPP work. Further exploration is needed concerning the implications of the historically authoritative role of researchers for the mutuality of RPP work. In such studies, the identified typology of boundaries in this study serves a double purpose: firstly, it may serve as preliminary indicators of the power relations within the RPP, and secondly, it may support key stakeholders in their boundary-spanning endeavours. To conclude, we hope that the detailed descriptions of the boundaries identified in a practical RPP context can help those engaged in RPPs in navigating the differences and discontinuities that will appear so that the boundaries do not become obstacles to but rather opportunities for learning.

Notes

In the later stages of the program the first author was invited to present preliminary findings at a board meeting and a process manager meeting.

When we describe the preschool teachers’ perspective, this is based on second-hand information, as we have limited data on preschool teachers’ actual statements (see also the Methods section). Thus, when we state that preschool teachers have said something, it is mostly a matter of preschool leaders, research institute members or researchers conveying the words of preschool teachers.

In several quotes, it may seem as though the speaker indicates a “correct” understanding. However, this is done vaguely and implicitly, and as such we can, based on the data, interpret the quotes as either (1) definitely expressing a “correct” understanding or (2) discussing different understandings. For instance, if a definite “correct understanding” is expressed, it is placed in Boundary 1 or 2 (depending on whether the focus is on preschool teachers’ understanding or support for preschool teachers’ understanding). If the quote instead tends to discuss different understandings, it is placed in Boundary 3.

References

Akkerman, S., & Bakker, A. (2011). Boundary crossing and boundary objects. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 132–169. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311404435

Akkerman, S., Bronkhorst, L., & Zitter, I. (2013). The complexity of educational design research. Quality & Quantity, 47(1), 421–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9527-9

Akkerman, S., & Bruining, T. (2016). Multilevel boundary crossing in a professional development school partnership. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 25(2), 240–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2016.1147448

Andreoli, P. M., Klar, H. W., Huggins, K. S., & Buskey, F. C. (2020). Learning to lead school improvement: An analysis of rural school leadership development. Journal of Educational Change, 21(4), 517–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-019-09357-z

Brown, S., & Allen, A. (2021). The interpersonal side of research-practice partnerships. Phi Delta Kappan, 102(7), 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/00317217211007333

Coburn, C., Penuel, W., & Geil, K. (2013). Research-practice partnerships: a strategy for leveraging research for educational improvement in school districts (0277–4232). W. T. G. Foundation.

Coburn, C., & Penuel, W. (2016). Research-practice partnerships in education: Outcomes, dynamics, and open questions. Educational Researcher, 45(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X16631750

Cousins, J. B., & Simon, M. (1996). The nature and impact of policy-induced partnerships between research and practice communities. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 18(3), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737018003199

Datnow, A. (2020). The role of teachers in educational reform: A 20-year perspective. Journal of Educational Change, 21(3), 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-020-09372-5

Davidson, K. L., & Penuel, W. R. (2019). The role of brokers in sustaining partnership work in education. In J. Malin & C. Brown (Eds.), The role of knowledge brokers in education (pp. 154–167). Routledge.

Denner, J., Bean, S., Campe, S., Martinez, J., & Torres, D. (2019). Negotiating trust, power, and culture in a research-practice partnership. AERA Open, 5(2), 2332858419858635. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419858635

Donovan, M. S., Snow, C. E., & Huyghe, A. (2021). Differentiating research-practice partnerships: Affordances, Constraints, criteria, and strategies for achieving success. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 71, 101083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101083

Farrell, C. C., Davidson, K. L., Repko-Erwin, M. E., Penuel, W. R., Quantz, M., H., W., Riedy, R., & Brink, Z. (2018). A descriptive study of the ies researcher–practitioner partnerships in education research program (technical report, 3). NCRPP.

Farrell, C., Penuel, W., Coburn, C., Daniel, J., & Steup, L. (2021a). Research-practice partnerships in education: The state of the field. William T. Grant Foundation.

Farrell, C. C., Harrison, C., & Coburn, C. E. (2019). What the hell is this, and who the hell are you? Role and identity negotiation in research-practice partnerships. AERA Open, 5(2), 13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419849595

Farrell, C., Penuel, W., Allen, A., Anderson, E., Bohannon, A., Coburn, C., & Brown, S. (2022). Learning at the boundaries of research and practice: A framework for understanding research-practice partnerships. Educational Researcher. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X211069073

Farrell, C. C., Wentworth, L., & Nayfack, M. (2021b). What are the conditions under which research-practice partnerships succeed? Phi Delta Kappan, 102(7), 38–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/00317217211007337

Ishimaru, A. M., & Takahashi, S. (2017). Disrupting racialized institutional scripts: Toward parent–teacher transformative agency for educational justice. Peabody Journal of Education, 92(3), 343–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2017.1324660

Kerosuo, H. (2001). ‘Boundary encounters’ as a place for learning and development at work. Outlines. Critical Practice Studies, 3(1), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.7146/ocps.v3i1.5128

Kerosuo, H. (2004). Examining boundaries in health care-outline of a method for studying organizational boundaries in interaction. Outlines. Critical Practice Studies, 6(1), 35–60. https://doi.org/10.7146/ocps.v6i1.2149

Klein, K. (2023). It’s complicated: Examining political realities and challenges in the context of research-practice partnerships from the school district leader’s perspective. Educational Policy, 37(1), 56–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/08959048221130352

McWhorter, D., van Roosmalen, E., Kotsopoulos, D., Gadanidis, G., Kane, R., Ng-A-Fook, N., Campbell, C., Pollock, K., & Sarfaraz, D. (2019). Fostering improved connections between research, policy, and practice: The knowledge network for applied education research. In J. Malin & C. Brown (Eds.), The role of knowledge brokers in education (pp. 52–64). Routledge.

Meyer, J. L., Waterman, C., Coleman, G. A., & Strambler, M. J. (2023). Whose agenda is it? Navigating the politics of setting the research agenda in education research-practice partnerships. Educational Policy, 37(1), 122–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/08959048221131567

Millward, P., & Timperley, H. (2010). Organizational learning facilitated by instructional leadership, tight coupling and boundary spanning practices. Journal of Educational Change, 11(2), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-009-9120-3

Mull, C., & Adams, K. (2017). The identification, influence, and impact of boundary spanners within research-practice partnerships. In M. Reardon & J. Leonard (Eds.), Exploring the community impact of research-practice partnerships in education (pp. 271–291). Information Age Publishing Inc.

Penuel, W. R., Allen, A.-R., Coburn, C. E., & Farrell, C. (2015). Conceptualizing research-practice partnerships as joint work at boundaries. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 20(1–2), 182–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2014.988334

Penuel, W. R., Bell, P., Bevan, B., Buffington, P., & Falk, J. (2016). Enhancing use of learning sciences research in planning for and supporting educational change: Leveraging and building social networks. Journal of Educational Change, 17(2), 251–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-015-9266-0

Sjölund, S., Lindvall, J., Larsson, M., & Ryve, A. (2022a). Mapping roles in research-practice partnerships–a systematic literature review. Educational Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.2023103

Sjölund, S., Lindvall, J., Larsson, M., & Ryve, A. (2022b). Using research to inform practice through research-practice partnerships–a systematic literature review. Review of Education, 10(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3337

Tseng, V., Easton, J. Q., & Supplee, L. H. (2017). Research-practice partnerships: building two-way streets of engagement. Social Policy Report, 30(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2379-3988.2017.tb00089.x

Tseng, V., Fleischman, S., & Quintero, E. (2018). Democratizing evidence in education. In B. Bevan & W. Penuel (Eds.), Connecting research and practice for educational improvement: Ethical and equitable approaches (pp. 3–16). Routledge.

VanGronigen, B. A., Bailes, L. P., & Saylor, M. L. (2022). “Stuck in this wheel”: The use of design thinking for change in educational organizations. Journal of Educational Change. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-022-09462-6

Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis. Sage.

Wegemer, C., & Renick, J. (2021). Boundary spanning roles and power in educational partnerships. AERA Open, 7, 23328584211016868. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584211016868

Wentworth, L., Conaway, C., Shewchuk, S., & Arce-Trigatti, P. (2021). RPP brokers handbook: A guide to brokering in education research practice partnerships. National Network of Education Research Practice Partnerships.

Yamashiro, K., Wentworth, L., & Kim, M. (2023). Politics at the boundary: Exploring politics in education research-practice partnerships. Educational Policy, 37(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/08959048221134916

Funding

Open access funding provided by Mälardalen University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

See Table

2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sjölund, S., Lindvall, J. Examining boundaries in a large-scale educational research-practice partnership. J Educ Change 25, 417–443 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-023-09498-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-023-09498-2