Abstract

This paper explores how schoolteachers in Kazakhstan engaged with the Renewed Content of Education (RCE) that has been introduced by the Government, and how changes in their beliefs and understandings influenced classroom practice. The study draws on the ecological model of teacher agency and elaborates on factors that contribute to the formation of teacher agency. The study used a mixed methods research design and is based on data collected over two years in rural and urban schools across three regions of Kazakhstan. Altogether, 227 teachers having different levels of experience with the new curriculum were involved in focus group discussions. The findings demonstrate that the majority of teachers acknowledged the value of the RCE, its short- and long-term benefits for students, and the broader aim of boosting the economic competitiveness of the country. At the same time, the findings suggest that, while a surface change occurred in teachers’ beliefs, their pedagogical practices, and the learning context, there is limited evidence that the teachers moved fully to new ways of teaching and embedded the principles of the RCE in practice. Through our findings, we verified the centrality of socially dynamic relationships in educational change. Teachers shared agency in developing their own rules and routines for collaboration. This paper adds to research on educational change in an international context by showing that the scope for teacher agency in reform implementation increases when teachers are able to develop deep reform-oriented beliefs, discourses, and pedagogical understanding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is increasingly recognised that teachers are key agents in implementing change and innovation. How teachers see their role in relation to innovations determines which reforms are adopted and embedded in classroom routines. International research evidence shows that, too often, educational innovations have failed because the need to leave space for teacher learning was not recognised (Lieberman & Pointer Mace, 2008). Prior research has demonstrated that instructional change and innovation can be supported or constrained by various elements of teacher collaboration (e.g. Hargreaves 2007; Stoll et al., 2003). Hargreaves (2019) argues what matters is “the quantity and quality of professional collaboration within the job itself” (p. 603).

In the last decade or so, Kazakhstan has witnessed what Levin (1998) has described as an “epidemic of education policy”, and consequently a large number of new demands have been made on schools and teachers. While this does not make it unique, it is an illuminating case for studying the ways in which teachers manage to navigate a barrage of educational changes.

Educational reform in Kazakhstan, as in many other countries, has been informed by reference to international practice, and characterised by a top-down, or centre-to-periphery model of dissemination. Among the major initiatives is implementation of what is officially referred to as the Renewed Content of Education (RCE). It includes: a new curriculumFootnote 1 which is more skills-focused; a new classroom and school assessment system (i.e. criteria-based assessment); new textbooks; and a new programme of teachers’ professional training supporting ‘modern’ approaches to teaching and learning (i.e. collaborative learning and more project-based learning). The aims of these various initiatives are to move to a 12-year compulsory education system (also referred to as the ‘0 + 11 model’, see OECD, 2018, p. 4). Not least were the following initiatives: per-capita financing in urban schools to support private-public partnerships and relieve the problem of urbanisation and a shortage of infrastructure; and the trilingual education policy – the teaching of non-language curricular subjects through three different languages: Kazakh, Russian, and English. English is to be the medium of instruction for the four subjects of Biology, Chemistry, Physics, and Informatics in Grades 10–11.

These reforms were aimed at boosting the economic competitiveness of the country; this has been a central theme in educational policy documents in Kazakhstan (e.g. the State Program for Educational Development [SPED] 2011–2020, 2020–2025). It is recognised that the education system must be adapted to meet the demands of the international socio-economic environment. The set goal is “accession of Kazakhstan to the club of 50 most competitive countries in the world" (MoES, SPED 2011–2020). The SPED 2020–2025 emphasises: “improving the global competitiveness of Kazakhstani education and science; education and training of a person on the basis of universal values and increased contribution of science to the country’s economy”Footnote 2 (MoES, Ch 4, aims). The notion of competitiveness is closely linked to the development of all levels of the education system.

The educational system in Kazakhstan is highly centralised, with extensive central planning and a detailed system of norms (OECD, 2018, p. 4). Furthermore, the system is bureaucratic as a result of its administrative structures and accountability measures. This affects the way the reforms are interpreted and implemented, and the role which teachers play in this. The renewed curriculum comprises: a challenging selection of subjects; use of the spiral approach to curriculum development; adoption of a hierarchy of learning aims and objectives in line with Bloom’s taxonomy; and pedagogical and goal-setting at all levels of education and throughout the course of training, which allows intrasubject connections to be taken into account as much as possible. Another important curriculum feature is the presence of ‘cross-cutting themes’ between subjects. In other words, bringing various subjects together in teaching and learning – a form of interdisciplinarity or curriculum integration. A balance of cognitive and social development is seen as essential, and this is built into the development of the educational process in the form of long-term, medium-term, and short-term plans (MoES, 2016, p. 31).

A central feature of these educational innovations in Kazakhstan is that they emphasise a more learner-centred approach designed to encourage critical thinking, meaning-directed, application-directed, self-regulated, and collaborative student learning. These kinds of innovations are supposed to foster knowledge acquisition in the sense of better recall, understanding and application of knowledge, and to foster lifelong learning (Vermunt & Endedijk, 2011, p. 295). As Darling-Hammond et al., (2019) argue:

Clearly, the new demands posed by the rapid expansion of knowledge in today’s world and the growing demand for high-level reasoning, communication, and interpersonal skills cannot be met through passive, rote-oriented learning focused on basic skills and memorization of disconnected facts. Neither can they be met with provincial thinking or an inability to engage new ideas and diverse people. (Darling-Hammond et al., 2019, p. 6)

The impact of educational reform becomes observable in the changes in everyday practices of schools, and in the experiences and practices of teachers and pupils (Fullan, 2007). The RCE developed for schools in Kazakhstan promotes new norms of social interaction in the classroom, new patterns of teacher and student talk, and fundamental change in the teacher–student relationship. There is an expectation to move away from lessons dominated by teachers in the role of sole authority, to lessons in which the teacher recognises, values, and teaches to differences between students, encourages effective learning in each individual, and promotes discussion, inquiry, and curiosity. However, the curriculum is still centrally determined and leaves only minimal flexibility in its interpretation at classroom level: arguably, the structures of accreditation and accountability are in tension with teacher professionalism in Kazakhstan.

Research evidence suggests that centrally initiated educational change is unlikely to be successful unless it actively engages the “practitioners who are the foot-soldiers of every reform aimed at improving student outcomes” (Cuban, 1998, p. 459). In the case of Kazakhstan, policymakers anticipated the need to support teachers’ professional learning as a prerequisite for the development and implementation of the new curriculum, especially as it confronted teachers with new situations and a fundamentally changed role. At the time of this research, the educational reform had been in place for three years. The schools that participated in this project were among the earliest implementers of the RCE.

Framework and literature review

Educational reform and teachers’ learning

Extensive literature indicates that the propensity for adopting educational innovations depends on teacher attitudes towards them, or receptivity to them (Brown & McIntyre, 1982; Fullan, 2007) points out that change is a subjective process in which individual teachers construct personal meanings to make sense of their experience. Of course, the implementation of curriculum reform is not solely dependent on individual teachers, their capacities, competences, attitudes, and beliefs (Coburn, 2003; Konings et al., 2007; Binkhorst et al., 2015; Park & Sung, 2013), but is also conditioned by the wider context: the climate and culture of the school, the district, and the system as a whole (Fullan, 2007; Hoyle & Wallace, 2007). Relevant factors here include: organisational culture; school leadership (Hauge et al., 2014; Harris & Jones, 2015); teachers’ opportunities to engage in professional development (Livingston, 2016); the level of teacher involvement; collegial support and collaboration (Ramberg, 2014; Park & Sung, 2013; Spillane 1999); and their past experiences in the classroom (Coburn, 2003). External factors could include changes in national education policy legislation (Leithwood et al., 2002), social context, ideological and political beliefs (Popkewitz, 1997), and the availability of resources.

Acknowledgement of teachers’ role in the reform process highlights the importance of teacher learning and development, since this enables them to reflect on, and in many cases to alter, their previous beliefs and practices (Livingston, 2016, p. 327). Coburn (2003) describes “teachers’ beliefs as underlying assumptions about how students learn, the nature of subject matter, expectations for students, or what constitutes effective instruction” (p. 4). Research shows that belief change among teachers, particularly experienced teachers, is a “rare phenomenon” (Pajares, 1992, p. 325), and usually associated with a radical paradigmatic shift (Bonner et al., 2020, p. 366). Moreover, where reforms lead to attitude change, it is not always clear why some teachers change and others do not (Bonner et al., 2020).

The work of cognitive psychologists, neuroscientists, and educational researchers, as well as expert practitioners, has provided us with a set of understandings about how people learn that have practical implications for teaching and teacher knowledge-building (e.g. Putnam & Borko 1997; Shulman & Shulman, 2004; Bakkenes et al., 2010; Harris & Jones, 2017). There are also specific models of how teachers learn (e.g. Little2002; Beijaard et al., 2007), as well as several pedagogical approaches prescribing how to make their learning effective (Vermunt & Endedijk, 2011). Often this work draws on ideas about workplace learning (e.g. Eraut2004; Beijaard et al., 2007), including a focus on teachers’ collaborative activity (Opfer & Pedder, 2011; Little, 2006). Rather than something that is done to teachers, professional development has been reclaimed as something “for teachers, by teachers” (Johnson, 2006, p. 250). This recognises teachers’ ‘right’ to direct and ‘responsibility’ to sustain their professional development throughout their careers (ibid.), highlighting teacher agency. Teacher agency is important for the way that reforms are enacted within schools, where change occurs (Lockton & Fargason, 2019, p. 471).

Teacher agency in reconstructing pedagogical practices

In the research on school reform and teacher professional development, attention to the role of ‘teacher agency’ has been growing notably over the last decade. A few approaches to understanding agency can be distinguished in the literature. In much psychological research, agency is understood as “the capacity to exercise control over the nature and quality of one’s life” (Bandura, 2001, p. 1). Another approach involves an ecological understanding of agency, and has its roots in action-theoretical work, particularly that stemming from pragmatist philosophy (Dewey, Mead), where agency is concerned with how actors “critically shape their responses to problematic situations” (Biesta & Tedder, 2006, p. 11; Biesta et al., 2015). According to Biesta et al., (2015), agency is not something that people have as a property, capacity, or competence, but rather, it is something that people do. The exercise of teacher agency is thus a dynamic process inflected by teachers’ beliefs (Biesta et al., 2015), personal goals (Ketelaar et al., 2012), and knowledge of curriculum and pedagogy (Sloan, 2006). Using the ecological model of agency, it is possible to see that under reform, when faced with a new instructional model, creating a “problematic situation” (Emirbayer & Mische, 1998, p. 971), teachers actively respond to the choices that face them (Bonner et al., 2020, p. 367).

Teacher agency has been examined by focusing on teacher positioning (Kayi-Aydar, 2015), teachers’ roles (Campbell, 2019), teacher leadership (Frost, 2006), and teacher “self-authored ‘I’” (Sloan, 2006), indicating that teachers’ identity must be considered in terms of their agentic choices and actions. According to Eteläpelto et al., (2013, p. 61), “professional agency is practiced when teachers and/or communities in schools influence, make choices, and take stances in ways that affect their work and their professional identity”.

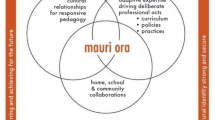

In trying to conceptualise agency, we have further been guided by the work of Imants & Van der Wal (2020), who follow the approach by which agency is understood as an activity, not as an individual characteristic. Building on pragmatism and extensive review of previous studies, they have proposed the model of teacher agency in professional development and school reform based on five characteristics: it (1) presents the teacher as an actor; (2) depicts dynamic relationships; (3) treats professional development and school reform as inherently contextualised, including multiple levels; (4) includes the professional development and school reform content as variable; and (5) considers outcomes as part of a continuing cycle (Imants & Van der Wal, 2020).

The dynamic relationship between individual teachers’ agentic practices, professional development initiatives, and the structural component of their work environments is central in the model (Fig. 1; Imants & Van der Wal 2020).

(Source: Imants & Van der Wal 2020, p. 7)

The model of teacher agency in school reform and professional development.

The present study

This paper draws on empirical data collected during a longitudinal project conducted by a multidisciplinary and international team of researchers from the University of Cambridge Faculty of Education, Nazarbayev University Graduate School of Education, and colleagues from Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools. Findings presented here are from two years (2017–2018) of a three-year period of data collection.

The authors of this paper are from the three participating organisations, represent different disciplines, and have between them personal experience of the Soviet system of teacher training and post-Soviet educational reforms, as well as of the evolution of what might be described as ‘international’ models of educational reform in the UK, the USA, and elsewhere. Two of the local authors have considerable experience of, and knowledge about, recent education reforms and changes in provision of teacher education in Kazakhstan. Therefore, between them, the authors share both insider knowledge and outsider perspective on the developments being investigated.

The study was conducted against the background of large-scale educational reforms in schools in Kazakhstan. The new curriculum and associated reforms were initially introduced at 30 ‘pilot’ schools acting as test sites one year ahead of the full roll-out of the reforms to all schools. The 30 pilot schools were geographically distributed around the 14 oblasts/regions and two major cities in Kazakhstan. The new content was piloted for Grade 1 from September 2015, moving on to Grade 2 in the following year. Following this, the renewed content of education was taken up in all mainstream schools for Grade 1 from September 2016. Likewise, Grade 3 was piloted in 2017, and Grade 4 from September 2018. In September 2017, the Renewed Content of Education (RCE) was introduced in Grades 5 and 7; and in 2018 in Grades 6 and 8 across all mainstream schools. Transition of all grades was completed by 2020.

The overall aim of the study was to examine the attitudes, experiences and perceptions of schoolteachers, school Principals and other stakeholders towards implementing the novel features of the renewed content of education. The following research questions are central to this paper:

-

1.

How do teachers engage with the renewed content of education?

-

2.

To what extent do teachers’ beliefs and understandings about education affect their decisions during the implementation of the educational reforms in classrooms?

-

3.

What factors contribute to the formation of teacher agency in their day-to-day working contexts?

Research design

Research settings

Three locations around Kazakhstan were studied in 2017 and 2018: South (A); West (B); and Central (C). Sites were identified by project researchers to represent the heterogeneity of ethnicities, employment types, regions, and rates of population growth. The purposive sample of schools included an equal representation of urban and rural schools in each region. All schools that were selected taught both primary and secondary grades.

For data-collection in 2018, six additional schools were added based on the recommendations of regional educational authorities. The aim for each of the three regions was to pair similar (but non-pilot) schools in Locations A, B and C with the original 2017 sample. This resulted in six repeat visits and six visits to new data collection sites, with the total of 12 schools in the three regions again equally split as urban or rural types (see Table 1). In addition, for 2018, a pilot and non-pilot school in an urban-only region (Location D) were added to gain further insight into regional factors. The reasons for the addition of this city region were twofold: first, to understand the breadth of the issues becoming apparent in 2017 regarding the contrast between urban and rural circumstances; and, second, to examine the ways in which closeness and connectedness to the centre of the reform process influenced its implementation.

It is important to point out that some pilot schools were receiving about 20% additional funding from the local budget, but this was not possible in all cases, so that schools differed in terms of internal resources such as stationery, printing facilities and access to the Internet, as well as teaching and learning materials.

Data collection approaches

A convergent parallel mixed methods research design (Creswell & Pablo-Clark, 2011) was adopted for the study, including semi-structured interviews, focus groups discussion, and surveys of teachers. The current paper is based on data collected over two field trips: focus group discussions with a total of 227 (78 + 149) teachers, and individual interviews with 52 (9 + 43) School Principals and/or Vice-Principals; and on open-ended responses provided by teachers to a survey (Table 1). Teaching experience ranged from one year to over 30 years, and experience with the RCE of between one and three years.

In 2017, a small research team of two researchers from the University of Cambridge and two researchers from Nazarbayev University visited six pilot schools in three locations, with a rural and urban school in each of south, west, and central Kazakhstan. The visits took place in September, so teachers were at the start of a new school year. The research focus was mainly on primary grades, and teachers of G1–4 were invited for focus group discussion. Those teaching Grade 3 were starting their third year of delivering the RCE, having already delivered the new content for Grades 1 and 2. Those teaching Grade 2 were generally starting their second year with RCE, whereas those teaching Grade 1 were new to RCE, albeit well supported by colleagues who already had experience of the new content. Teachers starting Grade 4 were still delivering the old curriculum (i.e. based on a teacher-centred approach) and applying traditional methods of assessment. Interviews were conducted with nine school Principals and Vice-Principals, and focus group discussions were conducted with 78 teachers of Grades 1 to 4. A survey was also distributed during visits to the same six schools as those teaching Grades 1 to 4. This generated qualitative and quantitative data through a mix of open and closed questions (Table 1).

In April 2018, field trips and data collection were conducted by a large research team of 19 people: four researchers from Cambridge University Faculty of Education, 12 from Nazarbayev University GSE, and three colleagues from Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools. The team looked at the third year of implementation, and aimed to provide continuing insight, conclusions, and recommendations on next steps in the ongoing adoption of the RCE, prior to its full implementation in the fourth year of its roll-out – due in September 2019 for the school year 2019/20. In 2018, the school-based sample included participants with no, one, two, and three years’ experience of working with the RCE (see Table 2). School Principals and Vice-Principals were also interviewed in each school.

Interview and focus group protocols were developed in 2017, and were revised for the 2018 data collection because of the inclusion of non-pilot schools. The 2018 protocol for interviews with school Principals, Vice-Principals, and for focus group discussion with teachers consisted of the following themes: the chronology of change; aims, goals, and objectives of the new curriculum; new approaches to teaching and learning, assessment, and evaluation, training, and support provided; and the effects of wider changes, including the coherence of the whole reform process. In addition, some background questions on the participants’ education, working history, and responsibilities were included. All interviews and focus groups took place in person, and a typical interview and/or focus group discussion lasted from 45 min to1 hour.

There were three administrations of a survey to create one dataset comprising a total of 729 open and closed responses from 12 pilot schools and mainstream secondary school teachers around Kazakhstan. The survey was distributed in two formats: paper-based and online. Both versions were identical in content (see Winter et al., 2020). The surveys were written in English and translated into Kazakh and Russian, and in this process went through ‘transadaptation’ – i.e. with an aim to ensure that the meaning of the terms used were as similar as possible in both languages after translation. Teachers had free choice to select either language version (Russian or Kazakh) irrespective of the normal medium of instruction of the school. Importantly, surveys were anonymous, with only the region (A, B, C, D) and location (rural or urban) of the school being recorded. Teachers were asked to indicate the grade(s) they were teaching and their subject(s).

The combination of multiple qualitative methods in this paper aimed at gaining a more fully developed understanding of the complexity and meaning of the situation being studied than would have been possible with a single-method research design (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). The individual interviews were conducted with school Principals and Vice-Principals to collect in-depth data about participants’ personal experiences, understandings, and knowledge of practices related to the implementation of the RCE in their schools. Teachers of different grades (see Table 2) were invited by the research team to attend a focus group discussion on a voluntary basis. The invitation was sent to a school manager who arranged their participation. There was a clear indication in some pilot schools that teachers were working in teams, and were comfortable expressing views in public, supporting one another, and sharing achievements as well as challenges. In other schools there were signs of some self-censorship and avoidance of difficult issues. The majority of participants from pilot schools shared a sense of their role as ‘champions or pioneers’ in trialling new pedagogy, assessment, and textbooks.

There are some caveats about using focus groups and qualitative responses to a survey. The focus group data are the product of context-dependent group interactions (Hollander, 2004), and present ‘group thinking’ (Rubin & Rubin, 2012) by allowing participants to comment on each other’s thoughts, experiences, and responses to specific questions. The researchers emphasised that they respected different perspectives and that all the opinions in the discussion were confidential. It was also important to give teachers enough time, after hearing the questions, for them to engage in some thinking ahead of the discussion. These strategies were designed to reduce the danger of ‘group think’.

In responding to the surveys, teachers had time to read and think about the questions, and to answer without any fear of criticism by either peers and/or school administration. However, our data indicate that personal, sensitive disclosures were more likely to occur in focus groups than in open responses to the survey or in the individual interviews with school Principals and Vice-Principals. However, overall, these methods were complementary, enhancing data completeness and confirmation.

The research team adopted the British Educational Research Association (BERA) ethical principles, especially in relation to informed consent, and sought to satisfy the ethical requirements laid down by participating organisations. Importantly, all interviews and focus group discussions included ‘live’ translation between the three languages – Kazakh, Russian, and English – so that all people present were able to contribute fully and be aware of what was being discussed. Informed consent was obtained either through the written consent form included as part of the ‘participant information sheet’, or at the time through recorded verbal assent following reading of the informed consent form. To protect the anonymity of participants and the confidentiality of the data, a coding scheme was developed in reporting results: schools were named A–D and participants by their job title, e.g. a ‘Teacher’; and the grade that they were teaching – e.g. Grade 1 is ‘G1’.

Data analysis

Voice files were transcribed and translated from their original language to English with quality control procedures ensuring confidentiality, and they were then transcribed and coded in NVivo 11/12. A thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) was used to identify themes emerging from the data. Two phases of coding were made through each dataset (2017 and 2018), and the themes were further explored and developed. As each set of data was added to the analysis, the coding categories were refined and expanded. After coding, transcripts, thematic summaries, categorical matrices, and analytical memos were used to develop analytic themes specifically relating to teachers’ classroom practices and experiences.

Open-ended responses to survey questions were analysed separately, and then subsequently combined with the analysis of the other data to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the alignment between various elements of the reform process and practitioners’ experience of this. Participants’ responses were grouped thematically with an indication of their experience with the new curriculum (e.g. no experience, one year, or two/three years of experience), then subsequently coded and used for content analysis based on themes from qualitative data around the topics of: key changes in teachers’ practices needed to deliver the new curriculum; what, if any, are the new approaches to teaching that teachers are using; and why they are using these; has the teaching changed during the academic year; changes in students’ learning; the purpose of the new assessment; and so on.

Overall, multiple perspectives from participants in schools and various sources of information permitted triangulation of the data. Comparing between teachers coming from different schools with different experience with the new curriculum was insightful.

It is important to acknowledge some methodological limitations of this paper. The research teams did not conduct lesson observations to gather evidence of changes in classroom teaching practice. This was because the main focus was on the perceptions and experience of the various actors involved in the reform. The data collected through focus group discussions and open-ended responses to the survey are highly reliable indicators of teachers’ beliefs and understanding, and of the ways they are grappling with changes in their practice. The interview data reveal how education managers understand the changes to curriculum and pedagogy, the roles of teachers and students, and the importance of communication and collaboration.

Findings

The findings are set out in line with the three research questions posed. Furthermore, participants’ responses emerged from analysis and synthesis of the two datasets. The results of this study offer a snapshot of teachers’ perceptions from different schools and contexts, and working at different stages of the implementation of RCE.

1. Initial enactment and common investment in continuous learning

Recalling the time of initial enactment, teachers reported anxiety and worries about the new curriculum. There was a mixed picture overall depending on who was asked about their opinion of the new curriculum. Teachers entering their third year of teaching gave far more positive reactions to the new curriculum that teachers just starting out with it. Hence, it seems that it takes time for teachers to become accommodated, and once they have changed their practices and seen year-on-year changes in their students, they are endorsing the new curriculum:

In the beginning, all the teachers were afraid. How will we teach it? How to conduct a lesson differently? We received trainings, but it was difficult to use it in practice in the beginning. But now we have got used to it gradually. Of course, it requires a lot of work […] the results can be seen during the lessons. (Teacher-School-C-1u-fg-G-2, 2017 data)

For teachers with very little experience, and those with a single year of delivering the new curriculum, the initial reactions were somewhat negative. Naturally, people were afraid because “all the innovations are always scary” (Teacher-School-B-1u-fg-G1-G2, 2017 data). During focus groups, teachers with years of teaching experience admitted:

I have been working [in a school] for about 24 years. New curriculum has been implemented 2 years ago. We studied in Orleu. Certainly, we had difficulties in the very beginning of the new programme, there was misunderstanding. Textbooks were of a new format. The programme was totally different. It caused some troubles. It was difficult to write plans in short time, but we tried to manage. We had problems with the resources. (Teacher-School-C-u2-fg-G1-2, 2018 data)

Participants mentioned courses and training events organised for teachers to gain full understanding of the aims of the Renewed Content of Education. Different providers were also mentioned by participants, such as the National Centre for Professional Development – Orleu, training provided by the Centre of Excellence Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools (NIS), and other local and regional providers and events, as well as in-house professional development seminars, workshops and open-lessons. Participants commented:

We took a lot of CPD courses … we know the theory of the new curriculum very well, but there are problems with putting it into practice. (Principal-School-B-1r, 2017 data)

Another teacher noted:

… It was [a] three-week course. We were trying to apply what we had learned. We had difficulties when we used [the curriculum] the first time and didn’t know how to do all of it; we learned through collaboration, and also relied on the Internet. (Teacher-School-A-r2-fg-G1-2, 2018 data)

Retrospectively, teachers and school administrators perceived that a certain level of preparation had been in place prior to piloting the RCE. For example, teachers commented on ‘multi-levelled in-service teacher training programmes’ they attended at the Centres of Excellence NIS branches across the country. The key benefits of levelled courses for participants were the opportunity to understand the RCE better and the chance to update their teaching practices.

However, not all teachers who participated in focus group discussions and responded to a survey received training on the RCE. The need for more professional development was repeatedly mentioned by both teachers and Principals:

There are the teachers who have not taken the course. It is like teachers were thrown in the open sea. (Teacher-School-A-u1-fg-G2, 2018 data)

One teacher, who expressed strong support for the RCE during the focus group, talked about the new expectations placed on teachers in terms of their continuous professional growth and an opportunity to become more autonomous in terms of lesson planning:

The new programme requires us to work and learn continuously. It is searching for information continuously. This is the pressure on the teacher. On the other hand, the teacher should study continuously now. We just get used for the ready materials before [i.e. with the old curriculum]. It looked like a beast if we need to find or design something which is not in the textbook. It looked like as impossible if the students do not have textbook. I think it is the new curriculum’s achievement that we could overcome all these challenges. It leads toward our professional development. We could not escape. This is the good side. We cannot say that there is no difficulty. Teachers struggle every time when the curriculum changes. We conduct it in the practice. First, teacher and then students struggle when the new curriculum changes are implemented. Therefore, it is hard for the teachers. (Teacher-School-B-r1-fg-G1-3, 2018 data)

Moreover, some teachers in open survey responses (2018 data) point out that to succeed with the new curriculum, a teacher should view themselves as a facilitator or guide to the students, be open-minded, and have a desire and the motivation for continuous learning. This appears to be partially connected to the perception of the new curriculum as being in line with the demands of the modern world, which requires a certain level of discontinuity with previously held views and beliefs.

Most of the participants displayed strong agency in their continued investment in learning so as to be more confident and prepared for teaching the new curriculum. The data from open responses (2018) show the needs of additional professional training. Unsurprisingly, over 70% of teachers who stressed this need for training have one year or less experience with teaching the new curriculum. What and how each teacher chose to learn was highly varied, and was determined by teacher prior experience and resources. The educational needs could be divided into the demand for more information about the new curriculum, the need to learn new technology and upgrade language skills, and finally the desire for workplace-based learning and experience-sharing workshops and training courses from more experienced colleagues.

In open responses to a survey (2018), the most significant number (141 out of 374 comments, or 38%) refer to the need for methodological support, including additional training. The central theme was the desire for more professional development courses and training workshops, as they:

… allow you to review the role of the teacher and the role of the student in the educational process, as well as get acquainted with the structure, content, consistency, goals and objectives of the new educational programme on the subject. (participant 153, survey 2018 data)

Some teachers mention an interest in consulting the Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools or following the news, but the majority of comments state the need for relevant training. One of them noted:

One needs to complete the professional development courses, to know and comprehend the teaching methodology, to be competent. (participant 163, survey 2018 data)

This idea of professional competency is what lies behind many of the education-related comments, as teachers seem to struggle with implementing the changes unless they feel competent to do so. A good knowledge of the theory was necessary. However, at the same time, it was not enough without good practical experience and the commitment to become a reflective and self-motivated learner. Teachers stated that observing a lesson run by a colleague gave them a better sense of what was needed to develop and improve their own teaching practice. Regarding the value of internal in-house seminars (many reported having these on Saturdays or during holidays) for providing peer support and sharing ideas, one teacher commented:

We should learn from each other, it is impossible otherwise, it is difficult for a single teacher to transfer to the revised content of education, because a lot of teachers still do not understand it well; there are newly employed teachers. (Teacher-School-C-2u-fg-G1-3, 2017 data)

Teachers noted that none of the training would have been of much value if they had not also engaged in self-education to support their professional learning. Thus, some teachers displayed strong agency in contributing to their own professional development and growth in ways that suited them in a specific context.

2. New pedagogical experience and changes of beliefs

The majority of teachers who have been working with the curriculum for one year described some changes in their practice. The most substantial proportion of reported changes in teaching were methodological in nature. Teachers with no prior experience of teaching the RCE, who started in September 2017, reported employing a new lesson structure, new active teaching methods, more creative activities and group work, and additional resources. These methods were used to raise ‘the intellectual level of students’, so the students could freely express their opinions. Several teachers with one year of experience of working with the RCE (18%, data 2017) explained that they used active and interactive methods, and differentiated learning, so that the students could reveal their personal potential and exercise critical thinking. About 20% of teachers (data 2017) with two years’ experience of implementing the RCE reported more application of new active teaching methods, such as independent work, pair work and problem-based learning, so that more students participated in the lessons and were interested in them. At the same time, those methods were seen as useful in achieving teaching goals:

In general, it is impossible to implement the reform without prioritising pedagogical methods and pedagogical skills. Therefore, first of all, we start from ourselves – from applying these in our practice. For instance, as for my own practice, we use a ladder in mathematics lessons. We gave exercises in the form of a game: we studied four numbers using games such as dominoes. Children achieve objectives through games. We also provide children with an opportunity to reflect on their mistakes. (Teacher-School-A-1r-fg-G1, 2017 data)

In the 2018 survey, out of 66 (9%) teachers who did not have previous experience of working with the RCE, the vast majority tried to use new methodological approaches in their teaching practice because of the requirements of the RCE and the need to meet learning objectives. Out of 593 (81%) teachers who had some experience with the RCE (1–2 years), 57 professionals (10%) did not use any new methods in their teaching practice (data 2018). Out of all respondents who used new teaching methodology, most people used it either for the direct benefit of the students (51%) or for teaching purposes (27%). Besides this, there was a group of comments attributing the use of new approaches to the requirements of the curriculum or learning objectives (12%).

Many teachers reported adopting a dialogic approach to teaching – so after mastering some knowledge, students were able to set a topic for the class:

In applying these new approaches, I was guided by ‘the importance of dialogue’ and ‘how to read’. The link between the student and the teacher in the teaching and learning is sure to be through dialogue. (participant 39, survey 2018).

That is to say, those who emphasised interactive approaches seem to believe in the power of communication when it comes to introducing the RCE to their students. Interestingly, during focus groups, younger and less experienced professionals were more likely to emphasise interactive approaches than expert teachers.

The data clearly show that some teachers were highly self-aware that their practice had to change, but that this depended on changing beliefs:

That’s how teachers changed their beliefs. How they are ready for the new thing is also very important. But even if you know the theory, and even the practice, if you have the same beliefs, then the situation will not change. Here you need to penetrate. The most important is the conviction of the teacher ... (Teacher-School-A-u-fg-Teachers-3F-2M, 2018 data)

As teachers’ self-confidence grew through trying new practices, experimenting and, at the same time, “struggling to move from old practices”, and worrying about “miss[ing] something” (e.g. in terms of grammar, handwriting), and reflecting on practice, teachers began to exercise emergent agency by trying to move on in their understanding and acceptance of new practices.

An interesting issue raised by teachers was the change of teaching style and the atmosphere in the classroom. In other words, some teachers used new methods to improve the learning process by “departing from the authoritarian style” (participant 219, data 2018) and creating an environment of cooperation. Participants noticed the change in the teacher’s role to that of a coordinator, acting as a guide for students, a shift towards child-centred learning:

In my opinion, this programme [the RCE] deals with the creativity of a child mostly, and this requires a lot of work and research from the teachers. We stand in the first place in the old curriculum, but now this is changed, and children take this place. That’s why it was 90% harder for us, because we studied for one month, and it was difficult to work without practice. (Teacher-School-C-u2-fg-G1-2, 2018 data)

As mentioned earlier, teachers talked about self-learning activities such as reflecting on their own practice, their realisation that the usual teaching approach did not work any longer, and that there were new practices to try. Of the teachers with less than two years of experience with the RCE, and less than ten years of overall teaching experience, 80% perceived psychological adaptation as playing an essential role in successful implementation of the new curriculum (data 2018). This could be due to younger professionals adapting to the RCE faster, and more competent teachers relying strongly on past experience and on their day-to-day classroom practice. The critical comments relating to psychological change refer to a teacher’s self-perceived creativity and open-mindedness, and a shift in attitude towards the students (and their new role). One teacher described the experience of a transformation of the traditional teaching role as follows:

In my pedagogical work, I have been expelled from the traditional classroom. (participant 173, 2018 survey data)

This corresponds with the comments about a less teacher-centred classroom, listening to students’ opinions and providing guidance, as opposed to a traditional lecture-centric attitude. As a result, teachers said that they engaged in more self-reflection and pursued self-education opportunities. At the same time, some challenges were reported:

I have been psychologically anxious for three months. Unless the teacher changed his/her mind in the new vision, I found out that the new programme was hard, and I had to change myself psychologically. (Teacher-School-A-u2-fg-G1-3, 2018 data)

However, participants commented that they were struggling not to go back to old practices, or that they were trying to justify (with some feelings of guilt and resistance) why ‘old teaching practices’ were necessary. The following comment provides an example of struggling between ‘new’ and ‘old’ ways:

There are still teachers who have difficulty in understanding and do not want to change, they are used to the old ways. It will not be achieved in a year, not two, it takes about five to ten years. Then we’ll see the results. (Principal and Vice-Principal-School-A-r1, 2018 data)

Some teachers with many years of teaching experience stated that they understood what the RCE wants them to do, and what they needed to put into practice, but at the same time they worried that they “could miss something”. In such a situation, teachers implemented their own strategies:

We’re all talking and talking, and it’s the practice, but children need to write. We have green notebooks [notebooks are not prescribed by the RCE], maybe it’s wrong, but we’ve got them. This is my initiative … Children write in green notebooks … (Teacher-School-B-1u-fg-G3, 2017 data)

This example suggests that teachers had a strong sense of professional responsibility towards their students. Thus, teachers had to rely on their personal agency to make decisions about the children’s current experience, their own pedagogical beliefs, and the day-to-day classroom practice – these being informed by both past experience and what is required by the new curriculum for maximising students’ potential.

3. Factors affecting teacher agency

The data reveal the presence of cultural, structural, and material conditions that can foster or hinder teacher agency and impact on the implementation of RCE. Some structures are internal and some external, and have been in place historically. Teachers were vocal about various issues that they saw as impacting negatively on their ability to do their jobs. As one teacher commented “the programme is new, but conditions are old” (Teacher-A-u1-fg-G1-3-10f, 2018 data). Even though the pilot schools were in an ‘experimental status’, they faced constant pressure to perform, with a low level of trust from the authorities and regular checks by different organisations:

Throughout the year, we notice frequent and endless checking on us. Each organisation checks their own agenda. One comes to check; other comes to check. The authority also worries. Therefore, everything is disrupted, and bothers and impacts on the emotional state of the teachers. (Teacher-A-u1-gf-G1-3-8f-1m, 2018 data)

A recurring theme across the data was an increase in workload and a lack of time for addressing all the demands of the RCE:

It is a big issue, and workload for the teachers has increased. For example, we have got the same salary for the paper and register. Now we use the Internet resources. It also requires additional payment for preparation. However, for resource we are not allocated. We do double the work. (Teacher-A-u1-fg-G1-3-8g1m, 2018 data)

A similar issue of time seems to have been the reason why many respondents also noted the need for increased hourly wages. To illustrate the point, one of the participants explained:

Teachers find it difficult to move away from traditional methods and forms of teaching. In the pursuit of hours, to earn more or less decent money, the quality of training and conducting lessons is lost, and, as a result, the learning outcomes are poor (participant 8, 2018 survey data)

The salary system for teachers in Kazakhstan is related to the stavka (or ‘teaching load’), which is widely used in some countries of the former Soviet Union, and which links pay to statutory teaching hours and nothing else (Steiner-Khamsi et al., 2009; Yakavets et al., 2017). This operates as a disincentive to engagement in wider professional activities such as “reflection on own practices, professional development, mentoring of novice teachers and communication with parents” (OECD & The World Bank, 2015, p.10).

The teachers reported working long hours, including work taken home because of the complexity of lesson planning, as the following comment shows:

In order to produce interesting and fruitful lessons, it is necessary to work on preparation until 2–3 a.m. (Teacher-School-A-r2-fg-G-1-3, 2018 data)

Some teachers pointed out the demands of classroom supervision, which prevent them from fully implementing the new curriculum in their respective subjects. One of the structural factors that was often mentioned by teachers is that the large number of children per class limits opportunities for group work, with interactive forms of teaching requiring attention to every child:

There are so many children to be divided in groups, even the resources to give, the cards, collect them … One person cannot observe six groups. I’m just physically unable to hear what they say, who is working, helping and who isn’t. There’s a lot of complexity. (Teacher-School-A-1u-fg-G1-3, 2017 data)

Another teacher explained it similarly:

… when there are so many children in the classroom, it is difficult to follow the spelling, for example, the classes are large. Questioning all children is hard. Anyway, according to the new curriculum, classes should be smaller, I mean, the accumulation of classes. Even working in a group with 36 children, how? (Teacher-School-B-u2-fg-G1-2, 2018 data)

Among material factors influencing teaching practices were better provision of teaching manuals and instructional materials. Updated technology and methodological literature were also among the greatest needs. Most of the negative comments referred to resource constraints (e.g. the limited availability of audio or video aids), rather than poor quality. Many of the teachers said that they either did not receive the updated resources, or that the resources were not sufficient. Together with the financial issues mentioned above, this demonstrates that the participants see the connection between the provision of tangible resources, decent salary and the success of the RCE:

Teachers need a motivation. Teachers had started working with the new curriculum. The salary has not increased yet, and if the teacher is not motivated, there will be no quality in work. This side is not solved. We will see the progress when these problems are solved. So, now I cannot say that the work is of a good quality. Teachers left the old method but could not reach the new one, as if they are standing in the middle. They are standing in one place temporarily. This is a temporary chaos. (Teacher-A-u3-fg-3F-2M, 2018 data)

The data also highlighted some factors which act as enablers for the formation of teacher agency. As already indicated, professional development and retraining were important factors, but there were also comments about alignment of the training with classroom practices and follow-up support. For schoolteachers, especially in rural areas, any type of professional support was welcomed, as a participant from a rural school described:

Retraining is important, it’s always necessary, to gather some seminars, courses … because everybody is stewing in their own juice. (Principal-School-B-1u, 2017 data)

Teachers also mentioned an increase in cooperation with their colleagues through the exchange of experiences, learning collaboratively in teacher inquiry teams, getting ideas from others (e.g. courses on the renewed curriculum, seminars/workshops, trainers, peers, lesson observations, learning and teaching resources), teachers sharing experience, everyone contributing in some capacity, teachers gathering, speaking out about what is important to them and collaborating in a mutually supportive way:

We share, everyone adds, we gather, we speak, spell out what is most important to us to show each other. If one teacher is alone, it’s impossible. Only in a team. (Teacher-School-A-1u-fg-G3, 2017 data)

Another teacher explained:

We communicate with each other; we collaborate and share … if there are four classes, then four teachers give ideas on what should be done for reaching the objectives. (Teacher-School-B-1r-fg-G1-3, 2017 data)

It has been an effective practice in some schools when teachers plan together, and discuss difficulties and which exercises they can replace and/or modify without deviation from the objectives. These comments appeared to demonstrate teacher agency as activity when knowledge is constructed collectively. Moreover, teachers engaged in activities that allowed them to learn new approaches and skills – various types of self-learning, self-development, self-perceived creativity, and the ability to ‘reorient’ quickly – and teachers noted that we have “to start from ourselves” and “we have learnt in a collaborative way”. In other words, the comments refer to the necessity for teachers to change their beliefs about pedagogical practices and develop better understanding of reforms, often resulting in a more innovative attitude. The responses relating to psychological adaptation stated the need to give up old stereotypes and to adopt a creative attitude:

… if the teachers themselves won’t go on to the renewed content of education, they can’t get it across to the children (Teacher-School-C-r1-fg-G5-7, 2018 data)

This reflective comment also shows a growing awareness of what is important, and a manifestation of changes in teachers’ beliefs.

The value of the new curriculum for children was seen in many ways. Among pedagogical outcomes, a shift in students’ attitudes, higher oral language proficiency, and better results were reported as factors that influence teachers’ attitude and practice. Concerning student behaviour, the recurring keywords emphasised the higher degree of independence, greater involvement in lessons, and more creativity and self-expression. One of the teachers indicated the use of games to motivate independent learning by saying that they used various elements of play:

increase the interest of students, so that students learn to work independently and improve their knowledge. (participant 73, 2018 survey)

This quotation relates to teachers’ views about students becoming more responsible for their own learning. Moreover, there was some indication of a positive change in the attitude of less accomplished students, since the lack of “skills of the underperforming students have been revealed” (participant 118, survey 2018), allowing teachers to target their improvement. These results are interesting on a number of levels. First, teachers spoke about a shift from knowledge to skills as the result of the RCE. Second, teachers saw that less able students could perform well too. Still, in some pilot schools, teachers noted that “maybe we should make it easier for the programme to be accessible to the average pupil” (Teacher-School-B1r-fg1-G3, 2017 data).

This discourse links to the above discussion of tensions in teachers’ beliefs and understanding of their changed role (as facilitators of learning), as well as teachers’ belief about students’ abilities and learning styles.

The data collected over two years show that support from school administrations was central to teachers’ motivation and their willingness to learn, and to developing their teaching practices, and that the shared agency of teachers led to school-wide spread of new practices:

As for the professional point, the administration helps us to develop our skills. We also do research, and we help each other among the members of our professional association. (Teacher-School-A-r2-fg-G5-G7, 2018 data)

The role of pilot schools and the teachers within them have altered to become ‘centres and agents of change’ through constantly conducting workshops and masterclasses based on the renewed content of education and sharing experience with teachers from other local schools. So the accumulated agency of teachers led to the translation and spread of the RCE to other local schools. Teachers were keen to stay in touch via various social media platforms and emails, through which they were able to ask questions and share good practice. Thus, teachers shared agency in developing their own ways and norms for collaboration.

Overall, the participants saw the connection between the internal supportive structures and the provision of tangible resources, together with in-school cooperation among teachers and inter-school collaboration, as important factors for scaling up the RCE.

Discussion

In this paper, we have examined how teachers engaged with the Renewed Content of Education (RCE), and how changes in teachers’ beliefs and understandings may have influenced classroom practice. We have sought to understand teachers’ experience and their work environment in order to explore what factors contribute to the formation of teacher agency. In this final section, we will review the main findings of the paper and present some implications for policy and practice, as well as make suggestions for further studies.

With regard to our first question, the majority of teachers acknowledged the value of the RCE, its short- and long-term benefits for students, and the broader aim of boosting the competitiveness of the country. At the same time, there was evidence of varied attitudes on the part of teachers with different amounts of experience of the new curriculum, even within the same school. Further, this study highlighted questions about how the reform was implemented, and how it was communicated to practitioners. Despite initial piloting, the reform was scaled up to mainstream schools due to time pressure, even though in many cases there was a lack of financial and human resources. Consequently, not all teachers were well-prepared. As a respondent from one pilot school claimed: “the reform is not bad … it just needs to gradually enter. Not so sharp” (Principal-School-B-1r, 2018 data).

This study has illustrated the importance of professional development and school reform being a continuing cycle (Imants & Van der Wal, 2020). Many teachers who took part in the current research study attended professional courses individually in learning environments that were different from their own contexts. Teachers seemed to learn the more theoretical elements, but reported a need for more practical skills, especially regarding lesson planning and the management of resources. The evidence suggests that the chance of readily transferring the knowledge and skills gained from professional courses into changing classroom practice, teachers’ beliefs, and behaviour was minimal. When staff development is fragmented in nature, and rushed and top-down in its implementation, it often engages only superficially with teachers (Fullan & Hargreaves, 1991, p. 17), and therefore lacks clear and direct links with classroom practice (Cuban, 2013). Even though teachers were trying to stay in touch with their course trainers and other participants via social media (i.e. WhatsApp groups and virtual platforms), exercising shared agency in developing their own ways for collaboration, it was acknowledged that teachers were struggling to change or transform their classroom practices.

At the time of data collection, some teachers from pilot schools told the research team that, as part of the piloting scheme and the translation strategies of the reform, they had to give a seminar for other teachers in the region who had not yet had any experience of the RCE, and the response was not always positive:

You can shoot us; we won’t work like this. This is because it requires a lot of preparation for one lesson … Not all teachers are ready for that. (Teacher-FG-C-r1-G5-G7, 2018 data)

This study suggests that only when educational reform is built into teachers’ professional development can they make agentic choices and take actions in a way that sustains their dedication to new ways of working (Day et al., 2005; Sannino, 2010).

It is clear from the data that additional investment in continuous professional support was required at a very early stage of implementation of the RCE. This study illuminates that the outcomes of professional development and reforms are events in a continuing cycle, not the final result of a linear step-by-step plan (Imants & Van der Wal, 2020). Thus, evidence from the study contributes to the view that professional development must be “long-term and embedded within a school’s daily routine, experiential, inquiry-based, reflective, collaborative, and geared to storing knowledge and networking outside of the school” in order to “innovate either on current practices or by adopting and altering new practices” (Hill & Desimone, 2018, p.104; Harris & Jones 2019; Timperley et al., 2007).

The data presented in this paper also suggest that teachers’ piloting the RCE, and their interpretations of the context of reform and professional development, had an impact on the course of a change process. Therefore, a discrepancy can arise between teachers’ judgements about worthwhile outcomes and the original project specifications that guide evaluation studies by researchers, developers, and policymakers (Imants & Van der Wal, 2020).

Our second research question focused on changes in teachers’ beliefs and understandings, and their classroom practices as required by the RCE. The findings suggest that while a surface change occurred in teachers’ beliefs, pedagogical practices, and the learning context, there is limited evidence that the teachers moved to new ways of teaching and fully embedded the principles of the RCE in practice. Furthermore, there was a certain amount of anxiety amongst the teachers, who reported that they were “working on autopilot”, “stewing in their own juice”, and “not crying if they don’t have the resources”.

It is clear from our data that the RCE moved teachers out of their comfort zones, forcing them to work in new and often unfamiliar ways, especially with regard to changing from a teacher-led to a student-centred approach and establishing a collaborative environment in the classroom. One of the respondents called it a “perestroika of consciousness (or re-building of consciousness)” (participant 83, survey 2018). Many had mixed feelings, recognising both positive and negative sides of the reform: on the one hand, they recognised advantages of the new curriculum (e.g. the development of oral communicative skills, and of critical thinking), and its impact on students’ confidence; on the other hand, they had worries about the impact on students’ literacy skills (i.e. grammar, writing), and on their motivation for learning. Previous research suggests that “teachers often assess the merit of the innovation in terms of experienced gains in efficiency of work and direct improvements in student learning activities and results” (Imants & Van der Wal, 2020, p. 6).

The data presented in this paper highlight the fact that teacher agency opens up a range of different forms of actions available to teachers. They can come to their own conclusions about the aims, tasks, importance, and feasibility of the RCE. Some teachers applied the new active teaching methods, and showed an understanding that different teaching approaches will lead to different outcomes and reflected on their own practice. However, some experienced teachers, while experimenting with the new active teaching, persisted with ‘traditional’ forms of classroom interaction (e.g. dictations, homework, and testing). Thus, teachers’ beliefs can evolve under reform conditions as they experience “transformation of context-for-action over time” (Biesta et al., 2015, p. 627). The results from this research appear to be consistent with a study by Lai et al., (2016) in China, where teachers expressed agency by critically considering and adapting new Western pedagogies in ways that allowed integration rather than abandonment of their previous practices and belief systems. In a case study, Biesta et al., (2015) found that many teachers were quick to adapt the discourse of a reform, but struggled with implementation. The evidence from our study supports previous research (Bonner et al., 2020) that agency also helps the in-depth understanding develop that is needed for teachers to enact fundamental change in their practice. In other words, the possibilities for teacher agency in reform implementation increase when teachers are able to develop deep reform-oriented beliefs, discourses and pedagogical understanding.

Our third question explored factors contributing to the formation of teacher agency. The data highlight both promoting and hindering factors which affect the formation of teacher agency and how the RCE is implemented. Barriers include cultural forms and material constraints. New ways of working were against the old structural and cultural traditions. Limited resources, large class sizes, increased workload, and limited preparation time put pressure on teachers, their wellbeing, and overall motivation to change. The old stavka system (salary based on teaching load) did not acknowledge the additional time that teachers needed to spend on lesson planning, teamwork, and work with parents. In some large urban schools, teachers were working in two shifts and often had to cover colleagues’ classes. It was difficult to find time for collaboration to discuss new practices in depth. Even though they were on low salaries, practitioners, especially in pilot schools, were under constant pressure to perform. Thus, change agency was constrained by accountability mechanisms and other forms of output regulation of teachers’ work, such as reporting on progress of the implementation of the RCE and students’ learning outcomes.

At the same time, this study highlights the centrality of socially dynamic relationships in educational change. Support provided by school administrations, increased collaboration and sharing between teachers, collaborative planning, subject teams, school networks and,

collaborative learning activities were reported by teachers in our study. Teachers were “getting ideas from others”, “reflecting on practice”, and “challenging their own assumptions”. Teachers shared agency in developing their own rules and routines for collaboration. Prior research suggests that the job-embedded learning approach (i.e. collaborative planning, peer observations, study groups, lesson study, etc.) is believed to have a positive impact on teachers’ agency (Day et al., 2007; Bangs & Frost, 2012). However, many of the schools in our research did not have strong cultures of collaboration, or, importantly, the capacity for providing the necessary professional development events on a regular basis. Simply sharing practice (Horn et al., 2017; Littel, 1990) and ‘showcasing’ open lessons are not deep forms of collaboration. Nevertheless, the research shows that these types of collaboration were significant for the way in which teachers with more experience of the RCE pushed for innovative practices while developing school- and district-level professional learning communities.

The data presented in this paper highlight two cultural factors in particular that had an impact on the formation of teacher agency. Teachers reported internal challenges, the need for psychological adaptation (change), rethinking a new role, and struggling not to go back to old practices. These were associated with a teacher-centred approach to teaching and learning which had been in operation for a long time. The evidence suggests that change was more difficult for teachers who had over 30 years of teaching experience and were trained in the Pedagogical Institute according to a Soviet-style curriculum. Popkewitz (1997, p. 149) points out that culturally influenced classroom practice is “historically constructed over time, and through a weaving of multiple historical trajectories”. Cohen (1990) explains that:

as [teachers] reach out to embrace or invent new forms of instruction, they reach with their old professional selves, including all the ideas and practices comprised therein. The past is their path to the future. Some sort of mixed practice, and many confusions, therefore, seem inevitable. (Cohen, 1990, p. 323)

At the same time, this research shows that some teachers were able to bring to bear their extensive past experience in tailoring rich and meaningful educational experience for their students as required by the RCE. The question is why some teachers are ready, willing and quick to change, while others require more time and professional support.

Another cultural barrier is a societal culture which can be characterised as having “high power distance”, “collectivist”, and “uncertainty avoidance” characteristics (Yakavets, 2016) based on existing norms and structure in the society. Educational policies and practice in Kazakhstan are deeply embedded in societal culture and traditions. People want and expect more guidance in societies with more power distance (see Hofstede 1980). Therefore, there is a tension between educational reform, the renewed content of education, and new teaching approaches which encourage creative, critical thinking skills and problem solving on the one hand, and societal values which encourage obedience to authority on the other. For this reason, too, some practitioners find it very difficult to switch from a teacher-centred approach which emphasises hierarchy to learner-centredness (Curd-Christiansen & Silver, 2012). It is clear from our data that existing norms and structure often conflicted with reform mandates. This made it difficult for teachers, as well as other individuals (students, school leaders, parents), to become active participants in school reform, to become, as Imants & Van der Wal (2020, p.12) claim, “actors, not factors”.

Implications and recommendations

This research extends existing work on teachers’ experiences and perceptions of education reform implementation by illuminating the role of agency in professional development. Our study was framed in terms of the importance of teachers’ beliefs as indicated by the concept of “deep change” (Coburn, 2003), teachers’ learning, and the ecological model of teacher agency developed by Imants & Van der Wal (2020). The main contribution of this paper is to extend the practical relevance of the ecological model of teacher agency for teacher learning settings and the implementation of the new curriculum and as a tool to identify (potential) complexities in professional development and reform processes. From a practical and policy perspective, the ecological model of teacher agency suggests that change is dependent on contextual conditions, rather than depending upon the characteristics of the individual (Priestley et al., 2012). Our study suggests that agency is achieved in particular situations (it is necessarily transactional) and can play a key role to support ‘deep’ change, in other words to alter “teachers’ beliefs, norms of social interaction and underlying pedagogical principles” (Coburn, 2003, p.5).

Our work has important implications for teacher education programmes and the ongoing professional support of teachers. In this study, novice teachers often reported that they had difficulties in using the new teaching and assessment approaches in their classrooms, since their studies had focused on the old programmes at initial teacher education institutions. Overall, the evidence from the research over the years in Kazakhstan (see Yakavets et al., 2017) suggests that it would have been advisable to change the curricular content of the initial teacher education institutions (ITE) before the RCE was introduced. Then, ITE would have better attended to the demands of the RCE and equipped novice teachers with the knowledge and skills to deliver it effectively. Many studies indicate that teachers are most likely to act as reform agents when their beliefs are in congruence with reform principles (Bonner et al., 2019, p. 367). Congruence of prior experience and goals (the iterational and project dimensions of ecological agency) with reform pedagogy supports depth of reform implementation (Donnell & Gettinger, 2015).

Our research suggests that, regardless of teacher experience with the RCE, collaboration with colleagues and support from more experienced peers, as well as from school administrations, were of prime importance. Further, this study highlights that a teacher working alone is not as successful as teachers working in teams, and groups sharing and learning new pedagogical principles and norms from the reform, which enables them “to develop the deep knowledge and authority necessary for reform ownership” (Coburn, 1990, p.7). Hargreaves (2019, p. 618) claims, “we are in a period of educational change when collaboration seems to have become the answer to almost everything”. The findings reveal a cultural shift among teachers towards working and learning collaboratively, but there is a need for structural change in the schools in order to allow time for teachers’ learning and knowledge sharing, enabling them to move from professional collaboration to “collaborative professionalism” (Hargreaves & O’Connor, 2018).

This paper suggests that it might be helpful for collaborative structures (e.g. teachers’ learning groups/teams) that start from the model of teacher agency to have a place in the school system and, as Imants & Van der Wal (2020, p. 13) suggest “to be an integral part of systemic professional and school development programs at the school level”. This also has an implication for the need to revise the teachers’ workload planning schemes, including the time allocated to collaborative practices and providing a remuneration package.

Methodologically, this paper adds an important contribution. Data for this paper were drawn from two years of a longitudinal research project that provided the opportunity to gauge change over time. It was a unique opportunity to analyse the hardly understood process of scaling up and sustaining changes in the longer term. Moreover, because of the rich data, we were able to capture teachers’ perceptions and reflections on how their beliefs changed over the years of working with the RCE. Further research is required to explain why some teachers with prior experience and a strong record of traditional teaching practice were able to move to using the new active teaching and learning approaches, while others struggled to move away from the ‘old’ routine. Importantly, analysis of teacher agency should include insights into both past professional experiences and teachers’ projective aspirations for their teaching, as well as the constraints and opportunities in the situations they face.

This study was conducted in schools in the early years of reform, but how do teachers’ practices change as the reform matures? What is the role of teacher agency in supporting the development of depth, sustainability, spread and ownership of reforms? How will the requirements of the educational reform change teacher collaboration and teacher professional practice? Research involving classroom observations could elucidate how changes in teachers’ beliefs are visible in their pedagogical practices.

Notes

In Kazakhstan, school education is based on the State Compulsory Educational Standard for Primary Education and the State Compulsory Education Standard for Secondary Education (https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/V1800017669). In this paper, we use the term ‘national curriculum’ for educational standards. While we refer to ‘curriculum’ (singular), we understand that in most schools around the world, multiple curricula are designed in different disciplines for different stages of study.

References

Bakkenes, I., Vermunt, J. D., & Wubbels, T. (2010). Teacher learning in the context of educational innovation: Learning activities and learning outcomes of experienced teachers. Learning and Instruction, 20, 533–548

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26

Bangs, J., & Frost, D. (2012). Teacher self-efficacy, voice and leadership: Towards a policy framework for Education International. Education International

Beijaard, D., Korthagen, F., & Verloop, N. (2007). Understanding how teachers learn as a prerequisite for promoting teacher learning. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 13, 105–108

Biesta, G., Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(6), 624–640

Biesta, G. J. J., & Tedder, M. (2006). How is agency possible? Towards an ecological understanding of agency-as-achievement (Working Paper 5). Exeter: The Learning Lives Project

Binkhorst, F., Handelzalts, A., Poortman, C. L., & van Joolingen, W. (2015). Understanding teacher design teams – A mixed methods approach to develop a descriptive framework. Teaching and Teacher Education, 51, 213–224

Bonner, S. M., Diehl, K., & Trachtman, R. (2020). Teacher belief and agency development in bringing change to scale. Journal of Educational Change, 21, 363–383

Brawn, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101

Brown, S., & McIntyre, D. (1982). Influences upon teachers’ attitudes to different types of innovation: A study of Scottish integrated science. Curriculum Inquiry, 12(1), 35–51