Abstract

This article deepens the knowledge of middle leaders’ impact on school improvement and organisation development. More precisely, it focuses on how middle leaders from comprehensive schools and preschools translated improvement strategies and tools from a municipal course on leading school improvement into their own organisations. It is based on interviews with middle leaders, teachers, and principals at two schools and two preschools. Translation theory is used as a theoretical frame. The findings show that the middle leaders translated improvement strategies based on local needs, and for several reasons: for clarification and reduction of roles and improvement areas; structuring improvement work; engaging and involving colleagues in school improvement; and developing a professional culture. When taking the role of translators, the middle leaders became central to progressing the developmental elements of local school organisations. The study recommends investing to provide middle leaders with improvement strategies and an understanding of translation theory to enable translations that aid the development of school organisations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Teachers in middle leading positions in schools are of interest to school improvement researchers all over the world (Boyaci & Oz, 2017). The issue is treated in literature reviews (Burke, 2008; de Nobile, 2018; Harris et al., 2019; Wenner & Campbell, 2017), and has been studied in terms of change agents (Blossing, 2016; Burke, 2008) and teacher leaders (Muijs & Harris, 2003). The interest in teachers as middle leaders is motivated by their supposed power in driving change in educational practice. Compared to other leaders, such as principals and external consultants, they are closer to the classroom, they are mostly more skilled in teaching acitivities, and they are more aware of the teacher culture and how to strategically deal with it. On the other hand, this advantage can also be a disadvantage; they are too close to the classroom to see the problems, they are perhaps not skilled in teaching acitivites in relation to different subjects, and they are themselves part of the teacher culture that might require change. Most of the previous research referred to above has focused on the roles and tasks of successful middle leaders. Defining roles and distributing tasks can be one way of adapting strategies for developing school organisations. A less researched area is how middle leaders could use the general knowledge from this research and adapt it to the local situation. This could be quite a challenge and in this study we contribute by focusing on middle leaders’ understanding and use, in terms of translating, improvement ideas in order to best affect and support improvements at the local school level.

The focus here is on a Swedish case, where middle leaders, in cooperation with principals, have improved the developmental elements of local school organisations by translating models and tools obtained from a municipal course in leading school improvement. Organisations can analytically be separated into one operational and one developmental element, also called an entrepreneurial element (Uhl-Bien & Arena, 2017). The former follows routines and rules that push for order and control, efficiency, and productivity, and the latter pushes for opportunities, innovation, and change. Developmental elements are often said to be fragmented, and to lack the ability to improve; ideas are initiated but seldom implemented and institutionalised (Blossing et al., 2015). In an earlier study (Nehez et al., 2017) that focused on this particular Swedish case, schools and preschools were identified in a certain school district in a municipality in southern Sweden that had made strong efforts to overcome such problems. In this article we report about this district.

By analysing this case, our aim is to deepen the knowledge of how middle leaders make an impact on school organisations. The research questions are: (1) How can middle leaders translate ideas in the form of improvement strategies for use in their own organisations? and (2) What impact can middle leaders’ translation processes have on a local school organisation?

Translation theories can be used for analysing how ideas are transferred between contexts, packed in one context and unpacked in another (Czarniawska & Sevón, 1996; Lindberg & Erlingsdóttir, 2007; Røvik, 2016). The primary interest here is the change and transferring process of ideas. Compared to, for example, research on fidelity on implementation (Cantrell et al., 2013), we are less interested in the original and planned ideas. Moreover, in contrast to some other research on translation (Røvik et al., 2014), the focus is not on specific improvement ideas, but more concretely on improvement strategies in the form of models and tools. The school district of focus for this study had no ideas for how to implement improvement other than using middle leaders to do so, and to train them to use such models and tools.

This paper begins with a brief introduction of research about the use of middle leaders for school improvements before looking at organisational change, and translation as a theoretical frame to understand change. Methods for the study are described before the findings are presented and discussed.

Middle leaders for school improvement

Research about using middle leaders for school improvement has generated knowledge about middle leader roles, conditions for middle leaders, and what middle leaders focus on in order to affect several levels within school organisations. However, not much is known about the micro processes of translating ideas into activities in order to promote school improvement, or how to adapt general knowledge of improvement strategies to the local school organisation.

In his review on middle leaders, de Nobile (2018) found six different roles for such leaders: the student focused role; the administrative role; the organisational role; the supervisory role; the staff developmental role; and the strategic role. Blossing (2013) identified similar roles in a Swedish empirical study. Based on whether they worked with micro or macro processes, and whether they worked within the operational element or developmental element of the organisation, Blossing identified four roles. Two of these roles, the school leader assistant role and the project leader role, focused more on leading the everyday work in the operational element of the organisation, rather than leading school improvement. The third role, the supervisor role, focused on micro processes in change by, for example, leading dialogue among teachers in the developmental element of the organisation. The fourth role, the organisation developer, worked with macro processes in order to improve the organisation of the whole school. The latter was the intended role for the middle leaders in the investigated municipality, and it’s initiating course sought to prepare them for that role.

According to Day and Harris (2002), teachers in middle leading positions seem to have important roles as change agents. At the classroom level, they link principles for improvement to classroom practice. At the collegial level, they develop ownership of improvement work through involving collegues in teacher collaboration. At the school level, they take a mediating role in communication and resource mobilisation.

de Nobile (2018) found that middle leaders performed their roles by managing relationships, leading teams, communicating effectively, managing time, and managing self. Fairman and Mackenzie (2015), who studied how teacher leaders in seven schools in the United States influenced their colleagues, found that they focused on both students’ and teachers’ learning, and used strategies such as sharing, modelling, advocating, supervising, collaborating, and learning together. The researchers highlight the importance of both supportive aspects such as trust, time, and support from the school leader, and relational aspects for successful teacher leadership. Teacher leaders need to have a challenging and supportive approach in which honesty, openness, reflection, communication, and courage are central. Fairman and Mackenzie also found that teacher leaders do not often call themselves leaders, because they are more influential as informal leaders.

Tensions between teachers with and without middle leading positions are observed by Bennett et al. (2007). One type of tension arises between the new expectations on leading the whole school organisation, loyalty to one’s own team or staff, and the professional rhetoric of collegiality. This raises the following questions:

-

Does collegiality mean joint professional learning or trust in colleagues’ individual professional autonomy?

-

Traditionally teachers are regarded as equals, but what happens when some of them suddenly have leading tasks?

-

How do middle leader positions get legitimacy?

Focusing on a formal middle leader role active in translations, it is acknowledged that middle leadership is part of a broader phenomenon of distributed leadership, including formal and informal leaders, as well as followers, and making up a collective practice of capacity building intended for better work and improvement (Liljenberg, 2015).

Grootenboer et al. (2015) found that many teachers spontaneously took informal roles as teacher leaders due to the fact that they had developed new knowledge and self-confidence based on education. Middle leadership is generated both through education and through practising new knowledge and developed skills, as we hoped to demonstrate in our study.

Middle leaders as translators of ideas for organisational change have been sparserly researched. Radaelli and Sitton-Kent (2016) identify translation practices of middle managers from aquistion of ideas to stabilisation of ideas. One of their findings is that middle managers are appropriate for the translation role. They make sense of new ideas and their impact on organisation practices. They use their intermediate position to collect signals of the actors in the organisation where the translation is going to take place in order to be able to know how to proceed, and they build a translation identity by becoming involved with the new ideas. The advantages of an intermediate position when it comes to translation of ideas have also been stressed by Furu and Lund (2014) in a study of middle leaders in a Norwegian school reform.

Organisational change and school improvement

In our study, local schools are considered as organisations with operational and developmental elements. Upholding a difference between operational and developmental element of organisations provides a competitive advantage for all sorts of businesses (Pålshaugen, 2000). It is vital that both elements of the organisation need to involve all teachers, so that tasks developed in the innovative developmental element of the organisation are implemented into the operating element. Otherwise, older, already institutionalised routines, survive (Ellström, 1992). Louis and Miles (1990) emphasise that the two elements need to be planned differently; operational elements can be planned rationally, but developmental elements require developmental planning. Ellström (1992) points out that operational tasks need to be regulatory and efficient, whereas developmental tasks need to be process-focused and based on creativity and teamwork. Björn et al. (2002) analysed failures in doing this, and Lander (2009) found a successful case.

In Sweden, schools have developed more evidently as local organisations since 1980 (Lander et al., 2013). The school reforms in the 1980s were influenced by organisational development and ideas about participation, group work, and action research in order to facilitate change. The change agent was a key role player as the leader of groups or teams. The core leader task was to enable participative processes with the aim to plan for improvement actions.

Institutional regulations have clearly promoted such a development in Sweden, but norms of participation and the need of teacher individuals to collaborate and to take action are also important for change to happen in the organisation. However, for our study it is important to bear in mind that local organisations are not shaped soley by institutional regulations from the state, but to a high degree are also shaped by the local rules and norms of social behaviour in groups when teachers perform daily school work (Louis & Miles, 1990).

To generate knowledge about organisational change, or more specifically about middle leaders’ impact on their school organisations, we use translation theories. Such theories can help to understand how ideas are objectified in a school improvement course for middle leaders, and translated into local activities in their schools.

Translation theories as a theoretical frame

Translation theory has been used during the last three decades to understand organisational change. Wæraas and Agger Nielsen (2016) have identified three theoretical perspectives on translation: actor-network theory; knowledge-based theory; and Scandinavian institutionalism. The perspectives focus on different aspects of the translation process and use different terminology. Scandinavian institutionalism focuses on the process of an idea being prepared for being brought into practice, which fits with our research interest.

Scandinavian institutionalists (Czarniawska & Jorges, 1996; Czarniawska & Sevón, 1996; Røvik, 1998; Sahlin-Andersson, 1996) have elaborated translation theories to understand how improvement ideas are transferred between contexts. According to these theories, transferred ideas or objects change on their way between contexts; individuals and contexts influence, or translate, ideas and objects (Andersson, 2011; Lindberg & Erlingsdóttir, 2007). A translation is in itself seen as an act of several individuals (Lindberg & Erlingsdottír, 2007; Røvik, 2016). Improvement ideas are being circulated between actors such as teachers, principals, researchers, consultants, and local or national authorities. This means that multiple actors with different interests, perceptions, and interpretations shape translations. How the translations are shaped varies across settings.

The translation theorists within Scandinavian institutionalism focus on different aspects. Czarniawska and Jorges (1996) focus on travelling ideas; how ideas are objectified and spread by individuals with assignments to disseminate the ideas. In our study, these individuals are represented by the course leaders. The teachers in middle leading positions attending the course then translated the objectified ideas into local activities.

Sahlin-Andersson (1996) focuses on aspects such as social control, conformism, and traditionalism that affect the translation processes. Wittbom (2009) and Andersson (2011) have both applied the theory in empiricial studies and when doing so they have found that ideas can be refused, or translated as assimilation, uncoupled or transformed. Andersson emphasises that assimiliation does not lead to any decisive change in the receiving context, and that uncoupling means that goals are more or less disconnected from what is considered as the core business. However, transformation means that the translation results in changes in structures and attitudes.

Røvik (2016) expanded the translation approach in Scandinavian institutionalism. He presents translation work as mediation and communication between a source and the target. According to Røvik, ideas are conceptual, and have to be expressed through language, even if they arise from practices. He refers to the process of translation of an observed or narrated practice into an abstract representation as de-contextualisation. Contextualisation, on the other hand, is the process of translating the abstract representation into a concrete practice in the target context. The abstract representation that is transferred from source to target is named the transferred knowledge construct. Following Røvik, the critical point in de-contextualisation is to ensure that the translation includes all relevant information and practice functions in the source context. The translators need to understand the complexity of the idea or object, including social and cultural relations and technical conditions. High explicitness of a practice improves the chances of successful translation compared with low explicitness. The critical point in contextualisation is to ensure full understanding of the target context, for example formal structures, cultures, routines, and personal skills that can enable or constrain the translation outcome.

Røvik’s (2016) translation theory is used in this paper to understand how middle leaders used ideas from a municipal school improvement course in their own organisations. Røvik’s translation theory (2016) focuses on the translation made by the receivers of the ideas. The theory offers concepts and reasoning on how to describe improvement processes in education in general and, more specifically in our case, in local schools and preschools. Some translations have no impact on the context, or might even make conditions worse, while others lead to major improvements in the transferred knowledge. Røvik stresses that knowledge transfers between organisations are rule-based. Furthermore, he argues that the outcomes depend on translation performances and competences. Awareness of translation modes and rules are decisive elements of improvement. Modes refer to a style of translation performance, while rules are guidelines for what kind of translations are possible according to a mode. There are three different translation modes and four translation rules.

When translators aim to reproduce a practice from a source as precisely as possible, they use the reproducing mode. The translation rule then is copying. If translators wish to copy one idea, but realise that adjustments of the idea are needed, the translators instead use the modifying mode. The rules here are addition and omission. Compared to the reproducing mode, the modifying mode is more pragmatic. When it comes to the third mode, the radical mode, the ambition is to use others’ ideas to develop local solutions. The rule here is alteration, which refers to the creation of unique versions in the target context.

The translators’ understanding of the source context and the recipient context decides what modes and what rules are being used. The three modes and the connecting rules are central to the translators’ competence. The way they are used may explain why some schools succeed in reforms while others do not. It depends on the translators’ ability to use the right mode, or the right rule, in each situation. That is translation competence.

A limitation with Røvik’s translation theory is highlighted by himself; namely, that it has not been sufficiently empirically tested (Røvik, 2016). Spyridonidis et al. (2016, pp. 234–235) conclude that “Røvik (2016) offers a fruitful avenue for future research by encouraging the research community to explore the connection between knowledge transfer and translation”. In Norway, researchers have used the theory to analyse and conceptualise school reforms (Røvik et al., 2014). Questions emphasised are: who the translators are, where and how the translations take place, what rules guide translations, and what competences are used in translations. Furu and Lund (2014), for example, have used the theory to understand how a national reform concerning formative assessment was translated through network activities and learning into school practices by those attending the network meetings. Furthermore, Nygård and Røvik (2014) have used the theory to understand the transfer of lean processes (creating more value for customers with fewer resources) into school practices, and Rotvold et al. (2014) used it to understand how national ideas of classroom management have been translated into local school practices. However, empiricial studies of translation have mostly focused on how ideas change during transfer (Radaelli & Sitton-Kent, 2016). The latter researchers have conducted a rewiew of research about middle managers as translators; however, there are few studies about the actors who are translating ideas. Furthermore, they stress that these few studies focus mostly on executive managers.

The Swedish context

Reforms of educational systems initiated at the arena of formulation are intended to reach the arena of realisation (Lindensjö & Lundgren, 2000). These will need translation and it is obvious that middle leaders in Swedish schools have already played an important part in this. Discussions in Lander et al. (2013) are here extended.

During the 1970-1980s, principals began to put together informal leadership teams, partly as a result of the national principal training programme from 1976, which was optional, but attended by about half of the country’s principals. The training programme implied a requirement for local schools to carry out development projects, and for this principals needed to cooperate with engaged staff members. The idea of school-based teams for improvement, with principals as the leading figures, was at the same time stimulated by state-sponsored courses for such teams. Early experiences were extended through nationwide in-set projects, where teams were trained to motivate school staff to support the vision for the compulsory school to be “a school for all", inclusive, and encompassing pupils with differing learning needs.

An early middle leader category, the teacher team leader, entered the scene during the 1980-1990s following an informal demand in the national curriculum of 1980 for team teaching. The original task for teams was the coordination of instruction for pupils in need of support, but assignements got broadened to include many kinds of teacher coordination, which motivated the introduction of team leaders. In preschools, the climate for cooperation was growing, while resistence in schools was common.

In 1991–92, state ownership of schools was abolished in favour of municipalities and private schools. A voucher system shaped an educational market. Schools and preschools felt a need for marketing a specific profile of the whole unit having a coherent staff.

Organising cooperation needed leadership. Increasing demands of leadership concurred with demands of professional recognition for teachers, which were met by distributed leadership of the kinds mentioned, including the recruitement of teachers and preschool teachers to middle leading positions, and finally a state-sponsored post of “first teacher” (only in schools) was introduced in 2013. All teachers’ roles were affected, as they had to adjust both to more intense cooperation, and to more middle leaders. Translation of improvement strategies is especially needed for adapting them to teachers who favour the ideal of the autonomous master of his or her classroom, and the ideal of equality among all teachers. Among preschool teachers, collegial cooperation was already a tradition, but not middle leadership. What is new in our case is that middle leaders were equipped with concrete models of how to build organisations, and asked to translate and use them in their own school organisations. Middle leaders in preschools were thus offered as support to supposedly already cooperating teams. Middle leaders in schools were offered as support for principals in need of help from engaged staff members.

Method

The Swedish case

In 2013, one year after the municipal course for middle leaders in leading school improvement in a municipal school district in southern Sweden, we let the staff at the 13 primary and lower secondary schools and 12 preschools in the district rate the efficiency of their middle leaders, called ‘process leaders’ (Olin et al., 2014). In a questionnaire, they rated items such as “Issues and points of views from the process leader are fruitful” and “The process leader organises improvement work efficiently”. If the school or preschool had more than one process leader, respondents were asked about the one they knew best. In a follow-up study of 2016, based on the same questionnaire used in 2013, staff once again rated the efficiency of their process leaders (Nehez et al., 2017). The reason for doing the follow-up study in 2016, i.e. three years after the first, and four years after the course for process leaders, was that we expected organisational change to be a time-consuming task.

In the follow-up, we looked for establishments where staff had increased or decreased their ratings since 2013. The motive was that process leaders had started to be questioned at some places, while we heard praise from others, which was easily seen in the data, and we wanted to explore that. We interviewed staff at two schools and two preschools. At all of them, process leaders were deemed equally important by the political and the administrative leadership. However, units where process leaders were still in postions had been reduced to four schools (31%) and eight preschools (67%). For schools this was heavily stimulated by the previously mentioned reform around first teachers, for which schools could receive a certain state grant (but not for municipal process leaders). In our sampling for interviews, we looked for one school and one preschool where staff ratings had increased, and one school and one preschool where they had decreased. Furthermore, we looked for variation in socio-economic background.

The interviews showed that the school and preschool organisations had changed since 2013 (Nehez et al., 2017). Despite decreased process leader ratings at two of them, organisation structure had changed positively at all four. Decreased ratings had been an issue related to expectations being too high from the beginning, and in one case the result of a time lag between questionnaire responses and interviews; improvements had been remarkable in the last months.

The interviews revealed that the course had been important for the change of the organisations. In this study, we re-analyse the interviews to understand how the process leaders translated ideas in the form of improvement strategies for use in their own organisations, and what impact the translation processes had. These theoretical aspects of improvement are well suited for generalising learning from single case studies (Flyvbjerg, 2011).

This case study comprises four separate educational establishments, which have been given pseudonyms: The Thor school; the Freya preschool; the Loki school; and the Vidar preschool. The Thor school is a mid-sized school for children aged 6 to 16, located in what has historically been a socio-economically homogenous area with middle and upper class families. The Freya preschool is located in three buildings, and with the same kind of social environment. The Loki school is a mid-sized school for children aged 6 to 12 located in a socio-economically heterogeneous arena. The Vidar preschool is located in four buildings, also within a heterogeneous area in the municipality.

When the two schools and two preschools initiated process leaders, all of them were involved in operational tasks, but few in developmental (Nehez et al., 2017). Operational issues dominated the content of both operational meetings and meetings intended to be developmental. The improvement areas were many, but it was unclear who was responsible for leading them and what the process leader role was. Few process leaders were expected to lead all improvement areas and take care of all developmental tasks. Futhermore, initiated improvements were not followed up.

We found new relations between the operational and developmental elements of the organisations, relations that enabled routine-breaking school improvement. The macro processes in developmental element of the organisation had increased, and focused improvement work on children and pupils. The developmental element of the organisation had received a more distinct role and become an integral part of the overall organisation. The improvement processes had become fewer, but more focused, and clearly adapted to local needs. Priorities for improvement had been formalised and process leaders’ assignments clarified. Expanded collaborative cultures were growing. More teachers were involved in developmental tasks. The schools and preschools had developed into what we call task and process driven organisations (Nehez et al., 2017).

By naming these schools and preschools task and process driven organisations, we mean that improvement elements were formulated as tasks or assignments and talked about as processes. The assignments freely engaged increasing numbers of teachers. In many cases, operational tasks were also formulated as specific tasks for specific people who were seen as resources to their colleagues in those areas. Leadership then was distributed to more teachers than process leaders. The developmental tasks consisted of well-structured actions based on evaluations, continually planned and followed up. Both operational and developmental processes were made more efficient.

The leading school improvement course

The course for the process leaders at the 13 schools and 12 preschools took place in 2012. One in seven of the staff at the schools and preschools attended the course, a total of 62 teachers. Their main function as middle leaders for change was to stimulate and guide school improvement in close cooperation with principals.

The primary goals for the course were to develop process leaders’ understanding of, and strengthen their capacity in, leading change. The course consisted of nine half-day seminars completed over one school year. Each seminar had a specific theme, e.g. what does school improvement and leading improvement mean, what kind of communication strategies can be used in improvement work, what kind of tools for observation, documentation, and reflection can be used to understand what happens in improvement work, how can groups be led, and how can attitudes to school improvement be changed? Furthermore, each seminar consisted of presentations of theories, presentations of teachers’ own leading practices, and dialogue. A smorgasbord of tools to support school improvement processes were presented to the participants. Participants tried out several of them, both at the seminars and in their own schools and preschools between the seminars.

To make the current understanding among teacher colleagues visible, the course participants learned to use challenging questions and structures in learning dialogue. Furthermore, they received models for peer observation. They also received a number of observation templates to enable analysis of, for example, patterns in group conversations and school cultures, as well as to what degree various school improvement processes had been initiated, implemented, and institutionalised.

The process leaders were given models for analysing the gap between current and desirable situations, as well as for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats in their own school improvement work. They analysed what they needed to do more of, less of, start to do, and stop doing (so called extended value analysis), in their own school improvement work. To be able to solve problems and find new ways to handle dilemmas, they tested structures for problem solving, such as dialogue and collegial mentoring. Finally, to support the movement from current to desired situations, the course leaders presented several models for formulating action plans and following up on actions. Models for effective goal setting were also introduced.

Interviews and analysis

In all four cases, principals, process leaders, and teachers were interviewed during May and August 2016. In total, 12 interviews were conducted (Table 1). Each interview lasted for 45 to 60 min. The principal interviews were individual, apart from one in which a deputy principal also attended. The process leader and teacher interviews were pair or group interviews, apart from one in which only one process leader attended. In total, 12 process leaders were interviewed and 15 teachers.

The interviews were semi-structured. We asked the participants to tell us about local improvement initiatives, the process leaders’ tasks and improvement strategies, the principals’ and teachers’ engagement in development tasks, as well as changes within these question areas. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed.

The analysis was conducted in three steps. The first step was identifying elements in all transcripts that explicitly or implicitly concerned tools and models from the course, how they were used in improvement practices, and why or what for. The second step was identifying what translation rules process leaders in different contexts used, and how their own context and knowledge of the context shaped their translations. The third step involved performing a thematic analysis inspired by Braun and Clarke (2006) with the aim of identifying common patterns in translations at all four establishments concerning the first step of the analysis. Data extracts were coded and the identified codes were collated into themes (see Table 2). Within the themes, we identified similarities and differences between the establishments.

Findings

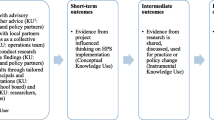

Overall, the process leaders translated ideas in the form of improvement strategies from the municipal course for four main purposes: (1) clarification and reduction of roles and improvement areas; (2) structuring improvement work; (3) engaging and involving colleagues in school improvement; and (4) developing a professional learning culture. Within each identified purpose, the process leaders translated several improvement strategies and used different translation rules, even when translating the same improvement strategy. The identified strategies are related to how they were translated and why the process leaders used particular rules connected to each identified purpose described.

Translation of ideas for clarification and reduction

Process leaders at both schools and at the Vidar preschool translated ideas about clear and defined work descriptions for process leaders together with principals. They continuously followed up these descriptions. Process leaders, teachers, and the principal at the Loki school point out that the framing has resulted in clarity:

Some of those who lead improvement processes have specific assignments, which are evaluated and revised twice a year (principal, Vidar preschool).

The idea of clear and defined work descriptions was highlighted in the course based on different research studies presented to the process leaders. Clear and well-communicated roles were recommended, and several examples of roles were presented.

The process leaders translated these ideas in order to raise awareness of the mandate given by the principal and gain legitimacy amongst their colleagues. One process leader described it in the following way:

In the small teacher team there was a pressure. I had a mandate and wanted to deliver. It was not easy to lead the teacher team I was part of. I felt a tension between management and colleagues in both directions. Difficult to handle that pressure (process leader, Thor school).

The principals supported the process leaders, since they wanted them to be a part of the management team and be able to lead school improvement:

[The process leaders] now have the legitimacy in the group, among the teachers. They did not really have that [before]. Here we noticed that the communication of their assignments was important for getting legitimacy (principal, Loki school).

Process leaders at different schools made different translations when clarifying different roles, for example teacher leadership, and communicating roles to nurture school improvement. In a way, they copied the idea of clear and defined work descriptions, but designed the roles based on the knowledge they had about their own school’s needs. Thereby, they used addition as a translation rule.

At the Thor school, the process leaders linked ideas of roles with ideas about focusing on fewer school improvement areas and stuck to them over time. Within the framework of a course assignment, the process leaders analysed their schools’ improvement history, and to what degree various school improvement strategies had been initiated, implemented, and institutionalised. In a template for analysing school improvement initiatives, each initiative was listed in a separate row and analysed with the help of questions in the template (see Table 3).

The process leaders at the Thor school used the observation template as an analytical tool along with research findings about how to interpret the outcomes of the analysis, especially findings on school improvement, highlighting the challenge of making improvement work sustainable over time. The process leaders considered the observation template easy to use and they therefore often chose to copy it without making any changes.

Through the analyses of the school improvement history, the process leaders and principals at Thor school became aware of what made the process leaders’ work difficult; namely, the numerous simultaneous improvement areas and the many ambiguities regarding who was responsible for what at the school.

The course contributed to an understanding that there were so many processes going on. It did not seem like the principal knew about it. [...] It was a good awakening. We spent a lot of time identifying the processes (process leader, Thor school).

They also became aware that few of the improvement initiatives had been sustainable. Because of the analysis of the school improvement history, the principal reduced the number of improvement areas at the Thor school. The principal established a management team consisting of the principal, the deputy principal, and the process leaders, who represented both the primary school and the secondary school. The process leaders’ roles moved from leading numerous improvement areas to focusing on a few processes, which reduced their workload:

There was no job description before [for process leaders]. It was written in connection to the course for process leaders. […] It turned out to be an extensive description. […] Today it feels more specified […] our colleagues know who to turn to in various matters (process leader, Thor school).

Copying of implications from research presented in the course resulted in job descriptions that later on were clarified as a result of addition. Overall, the organisational change at the Thor school can be described as a result of alteration, as the process leaders, together with the principals, translated ideas for clarification and reduction from theory to their own practice. Roles were developed based on the needs of the school, which included pupils’ language development, assessment for learning, and interdisciplinary work. The principal emphasised in the interview that they held on to identified focus areas.

At the Thor school, the clarification of roles was one of the first translations made by the process leaders and the principal. At the Vidar preschool, on the contrary, this framing was a more recent one. The process leaders’ role only started to become clear after almost three years. The translation was triggered by colleagues not understanding process leaders’ role and their own roles in improvement work. One teacher described the change:

I have experienced that [the process leaders] have changed their structure (…). Before they all worked with one thing, now they have divided the assignments between them. (…) I feel that it has become much clearer in the last six months. (…) I think they have been given clearer assignments (teacher, Vidar preschool).

The teachers underlined that the process leaders now really fronted the improvement work, compared to earlier when they were only assisting the principals even though their role was presented as leaders and owners of improvement processes.

Translation of ideas for structured improvement processes

Particularly at both schools, and at the Vidar preschool, process leaders translated tools that could help them to structure improvement processes. Process leaders, teachers, and the principal at the Vidar preschool described how the process leaders used tools introduced and used during the course. A template for analysing strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, so called SWOT-analyses, were used for identifying strengths and weaknesses in improvement areas. A template for action plans was used for formulating plans for improvement areas. A template for documenting observations and reflections was used for following up, documenting, and evaluating improvement actions together with the teachers. The template, called DLW (Done, Learned, Wise to do) was used after every assignment during the course (see Table 4).

During the course, the attending teachers noted individually what they had done within their process leader practice and reflected on what they had learned. Together with other participants, they reflected on what would be wise to do next.

The process leaders at the Vidar preschool emphasised that the tools had contributed to them identifying areas for development and being able to stay focused during long-term processes. Action plans and DLW were also used at both schools. DLW was copied by all cases, but for different purposes. Process leaders at both schools used it in connection with peer reflection on teaching practice observations. The action plan template, on the other hand, was translated using addition. The presented template contained examples of areas to involve in a plan but opened up for individualised suggestions. Thereby, the process leaders sometimes added aspects in practice that seemed urgent to highlight, and that were added to the template. This led to an expansion of the original template by adding questions. Furthermore, when DLW was used for evaluation at the Vidar preschool, the process leaders developed the template by adding more questions to be able to reach deeper reflections when following up their improvement work.

At the Vidar preschool, process leaders, teachers, and principals had a need for a common approach to leading improvement. They all highlighted tools for structuring improvement work. The preschool had four middle leaders from the start, with assignments to provide structures and tools for their colleagues’ improvement work. The preschool is located in four buildings with each building consisting of two or more departments. Parents are satisfied with the preschool and recommend it to other parents. Nevertheless, staff members have differing views on, for example, teaching methods and children’s learning, and the departments have been working in a somewhat isolated manner from each other over a long period of time. The preschool has had the same principal for many years. The principal wanted the process leaders to find one way of organising improvement for all departments. The process leaders saw the need for clearer structures and processes, and chose to use SWOT, learning dialogue, and an action plan as tools.

The first step for the process leaders at the Vidar preschool was to use copying when translating the SWOT assessment tool before initiating new improvement areas, to analyse what enabled and constrained the practices. The SWOT tool does not imply new ways of carrying out previous practices; instead, it helps assess practices as they are. The process leaders considered this to be an easy tool to transfer an idea from the course into the preschool practice. It also yielded an immediate result that could be taken into consideration by the leaders, who were, according to the process leaders, in need of new impulses to overcome old obstacles to improvement.

The action plan was a translated structure that over time became highly appreciated at the Vidar preschool. The process leaders considered the action plan to have a potential to lift their joint work to a higher level as it helped them hold on to processes over time. Initially, the focus was on copying the action plan. However, they assumed that as their colleagues’ understanding of the action plan increased, there would be more focus on the content than on the structure. Their assumption was correct:

Now, after the effort of language development, I feel that the approach has started to come together. The next time we have better conditions when entering into an action, there will not be as much focus on how to use the action plan. Instead, there will be more focus on its content (teacher, Vidar preschool).

In the beginning of the second year of using action plans, there were additional changes in how the plans were used. As a consequence, all staff were more satisfied with the joint development work at the preschool. The ownership of the action plan as a tool for school improvement has been passed along to the teachers. The situation opened up for both the teachers and the process leaders to become translators.

The interviews revealed how some process leaders translated the very idea of creating structure. At the Thor School, the process leaders developed their own templates to create structure linked to different areas for improvement, such as language development work. A process leader created a framework for collegial meetings with fixed questions that recur at each meeting to facilitate teachers’ preparation.

Translation of ideas for engagement and involvement

Process leaders from both schools and preschools translated ideas about engaging and involving all teachers in improvement work. For example, process leaders, teachers, and the principal at the Freya preschool all emphasised the importance of everyone who works at the preschool being involved. The process leader stressed that they all act as leaders:

[…] I try to make my colleagues involved so that we create together. I am not the leader of them, but still try to look at how we can work with the processes in the beginning, but then it is our joint work. We really work as a team and I think that is the most important thing. I think we got many tips on how to strengthen the teacher team at the process leader course (process leader, Freya preschool).

The interviewed process leader at the Freya preschool pointed out that she brought many models and tools from the from the course to her own organisation, but that she has mainly focused on how to engage colleagues. She had legitimacy at her preschool department and could therefore engage them. She used structures from the course to ensure that all her colleagues were involved in dialogue. The process leader described how such structures have become a natural part of her everyday work. The teachers and the principal at the Freya preschool confirmed this and supported the idea of participation: “The idea is that all teachers at the preschool should be involved in the learning conversation in order for it to yield results,” the principal said.

In the course, the process leaders were presented with structures for dialogue. A specific kind of dialogue was introduced and practiced during the course; namely, learning dialogue for getting all teachers to engage in school improvement. Learning dialogue aims to enable all participants to share experiences and knowledge in well-defined subjects. The method is very strict and provides detailed instructions for when everyone is supposed to speak and what they are supposed to speak about. The method involves so-called rounds, i.e. taking turns when speaking. In descriptions of the model, it is recommended that an observer is used initially to pay attention to how the model is being used, and to give feedback to the person leading the dialogue and the colleagues participating in it.

All four cases translated ideas about learning dialogue for engaging and involving all teachers, although they used different translation rules. Process leaders at both schools and at the Freya preschool at first copied the idea. They expressed that they even used the recommended observers to get feedback on how they managed to listen to each other and create knowledge together. At both schools, there was a readiness for trying new structures for dialogue since the teachers felt a need for change in order to meet the new situation experienced at their schools. The principals emphasised that, for many years, the pupils had been highly motivated. In recent years, however, at the Thor school, the area had expanded from a residential area to also include apartment complexes, which made it more socially heterogeneous. The teachers needed competence to support children with differing needs and diverse experiences of succeeding in their studies. The Loki school had received new group of pupils, young immigrant newcomers, and had to expand their teaching to support children with special needs. This put pressure on both individual teachers and the entire teaching staff. The teachers expressed a need for improvement work to expand their knowledge and find new ways to develop their professional competence and teaching practices. They considered learning dialogue as a way to develop communication to aid learning. After a while, the process leaders and teachers at both schools and the Freya preschool modified the learning dialogue; they did not use the observer role, for example, and thereby changed their translation rule from copying to omission.

However, at the Vidar preschool, having tested the model once, the process leaders modified the learning dialogue. Some of the staff found the rounds in learning dialogue to be very stressful and the process leaders then eliminated this procedure from the method, which means that an omission was made in the translation:

These are not strict learning conversations, because [the colleagues] think it feels a little strange, but we have dialogue with the conversation leader and secretary. We use rounds, but not as strict, and we are careful not to interrupt each other. It feels good. There were many colleagues who got a little stressed [when everybody was supposed to talk]: ‘Now I have to talk and then I have nothing to say’. So this feels a little easier (process leader, Vidar preschool).

The process leaders altered the learning dialogue in order to meet colleagues’ needs. Instead, other routines for making sure that everybody had a chance to voice their opinions and ideas were added, such as sharing written reflections. This is an example of how changing one aspect of the method by omission and addition does not change the purpose of, in this case, collegial learning. The method is still recognisable and therefore defined as the same method.

At the Vidar preschool, before the course for process leaders, the principal started dialogue with the teachers about professional values and learning environment. The principal tried to enhance collaboration through dialogue aimed to develop the professional practice. There was dialogue focusing both on the way staff interacted with the children and with each other. There were vast differences in how staff members perceived and experienced dialogue; some found it emotionally challenging. The staff also tried to agree on what an integrated and stimulating learning environment for the children might look like. In some departments, there had been ongoing improvements of the learning environment. In others, professional improvement initiatives had been scarce. The introduction of process leaders for school improvement became a way for the principal to continue developing dialogue. The process leaders became facilitators of professional learning groups at the preschool, and thereby learning dialogue became a tool for structuring the dialogue they were supposed to lead. The principal emphasised the importance of having process leaders taking this role:

I think they help increase the staff approval of our processes, and that our processes become more solid when we have them. Our dialogue becomes clearer. More teachers speak their mind and add their perspectives. We could not have done this well without process leaders (principal, Vidar preschool).

The process leaders have moved from having an unclear role to having a clear role in the preschool’s improvement work, leading their colleagues in processes in both large and small elements of their daily work. The principal’s trust in the capacity of the process leaders led to the development of distributed leadership. This enabled sustainable development that included all staff.

Translation of ideas for professional learning

Process leaders from both schools and both preschools translated ideas about developing school cultures that promoted professional learning and joint improvement of teaching. In the interviews, several process leaders stressed that they gained knowledge of these theories and tools during the course. For example, both schools organised professional learning groups and at both schools and preschools teachers, in different ways, engaged in each other’s teaching practices:

Five years ago, I had no idea what was going on in primary school (…). Now we are inside [each other’s classrooms] and reflect upon each other’s lessons (…). It is a huge difference. Before we talked about it, then (…) nothing happened (process leader, Thor school).

In the course, all process leaders analysed their own school cultures and had, as an assignment, to analyse the culture along with colleagues at their own school. Many of them realised that they worked in cultures characterised by teams separated from each other, without common visions or goals. The course leaders presented strategies such as peer observation for getting teachers to engage in each other’s practices and develop practices together. Furthermore, the course leaders emphasised that peer observation could be done in several ways. They highlighted the importance of having local agreements for such observations based on the teachers’ confidence in exposing their teaching to each other, as well as documenting the observations, and giving and taking feedback from each other.

At the Thor school, the ideas of engaging in each other’s practices were translated into teachers observing each other’s teaching with DLW as an observation template, and having learning dialogue based on the observations every two weeks. A process leader described that intially the teachers themselves chose what to be observed on. However, as the trust within the collegium grew, thoughts on having a common focus in observations was raised, to further challenge teachers’ understanding of their practices. An example of a common focus was how teachers in their teaching practices communicated what to learn. This can be considered as copying ideas of peer observations and documenting observed activities. At the Loki school, the ideas were translated into observations and filming of each other’s teaching in mathematics. Filming is an addition. The process leader linked filming to learning studies and lesson studies, and offered to film the teachers’ practices. One of the teachers explained how the process leader structured the situation:

She [the process leader] explained that it is called learning studies and lesson studies and what [these different methods] means but emphasised that the important thing is not to delve so much into differences. She explained what to do and set a clear deadline. We worked in groups and then mixed groups. It was a long but well-structured process. (…) During the observations, we had subsequent conversations and then we focused on how we made progress (teacher, Loki school).

To sum up, the process leader used addition as well as copying by partly combining different methods from the course, and partly applying some methods in their original form.

The principals at both schools supported collegial learning to improve teaching practices to be able to help all children to reach the learning goals. Filming in peer observations at the Loki school was first voluntary but later became mandatory, based on the principal’s decision. At both schools, teachers were in need of each other’s competence to support children and it became clear that the principal’s support was an important condition for the translation of ideas of peer observation. At both schools, process leaders, principals, and teachers described how teachers first resisted peer observations and filming each other, but later wanted to prioritise such learning opportunities. A teacher at the Loki school expressed that “observations with filming were something we were obliged to do, but it turned out to be positive”. The process leaders at the Thor school were about to take another step in their translation of the idea of peer observation; namely, observing teaching at another school and inviting peers from this school as observers. They expressed that they needed new input about teaching heteogenous groups of pupils.

At the preschools, the ideas of peer observation were not copied by the process leaders. Instead they translated the ideas into practices where teachers from different departments visited each other’s departments for staff meetings, and presented how they worked to develop children’s different skills. Then, at both preschools, the ideas of peer observation were translated by omission, and emerged as showing examples on teaching practices. The translations were made based on the conditions at the preschools, conditions that differed from those at the two schools. The preschool teachers were not used to interacting within each other’s teaching practices. Not all of them were confident with being observed by colleagues. Instead, they were encouraged by the process leaders and principals to present to each other how they worked with the children to reach the goals within the improvement areas:

Ideas from the other preschool departments are usually presented at the staff meetings. We are shown how the others have worked and we can bring in parts [in our own teaching]. A few months ago, there was focus on learning from each other, not only within the teacher team but also between the preschool departments (teacher, Freya preschool).

The principal at the Freya preschool described how she stressed the importance of openness among the teachers as well as sharing between preschool departments and joint improvement; she emphasised that a new school culture characterised by these basics was being established. The process leader and the principal continuously add new elements to the idea of presenting how they worked to develop children’s different skills to cultivate a professional culture.

Discussion and conclusion

The starting point for this study was a former study (Nehez et al., 2017) in which we identified that process leaders had affected their school organisations. They changed them from organisations with unclear improvement areas and strategies, where many teachers lacked engagement in joint school improvement, to organisations with clear improvement areas, efficient improvement strategies, and collaborative cultures. In relation to our aim to deepen the knowledge of how middle leaders make an impact on school organisations, we have, in this study, identified that the process leaders contributed to this change by (1) using translations for clarification and reduction of roles and improvement areas, (2) structuring improvement work, (3) engaging and involving colleagues in school improvement, and (4) developing a professional learning culture.

Our research questions focused on how middle leaders translated ideas in the form of improvement strategies for use in their own organisations, and what impact middle leaders’ translation processes had on a local school organisation. Concerning the first question, our study showed that the middle leaders chose improvement strategies and translated them into variants in their own school organisation by identifying the needs of their local organisation and considering these needs. By considering these needs, they made constant adjustments in the translations.

These results confirm the findings of Radaelli and Sitton-Kent (2016) that middle leaders, based on their intermediate position, are appropriate for the translation role, which enables organisastions to develop. They clearly constantly engage themselves in collecting signals of how to best translate improvement strategies and when to adjust the translations. By doing this, the middle leaders in our study managed to perform what Røvik (2016) refers to as a successful contextualisation; translations that are adapted to their organisations and contribute to organisation development.

What the findings specifically added to previous research is knowledge about the micro processes of translation. The results describe translation activities made by the middle leaders in order to promote school improvement. In terms of translation, they use different translation rules to translate different kinds of improvement strategies. Common for the improvement strategies brought into practice by copying was that they were all simple structures and not contextually dependent. Strategies translated by addition either lacked content of their own (i.e. templates) or contained several possible combinations or interpretations (i.e. ideas of roles). The feature that distinguished strategies that were translated using omission was that the underlying purpose (i.e. learning through dialogue) did not depend on transformation of one specific aspect; the strategy still facilitated what was aimed for (i.e. professional learning). The strategies that were translated by alteration were characterised by complexity of underlying ideas.

Concerning our second research question, i.e. what impact middle leaders’ translation processes had on a local school organisation, the study indicated that the middle leaders’ translation of improvement strategies affected the emergence of task and process driven organisation at the two schools and two preschools. This is demonstrated by: how translations formed clear assignments for middle leaders (and in some cases also teachers); well-defined, focused and fewer improvement areas; well-structured improvement work; increased participation in school improvement; and growing collaborative cultures. In these task and process driven organisations, the leadership was distributed not only to the middle leaders, but to many teachers, being resources for their colleagues within specific areas. These findings are in line with previous research, for example Blossing’s (2016) results of middle leaders improving whole school organisations, as well as Day and Harris’ (2002) results of change agents working at several levels in order to improve classroom practice and making changes at the school organisation level. Our study expands the knowledge by showing that this this type of development also applies to preschools that have middle leaders.

Translation seems to be a matter of understanding needs signalled within an organisation, of constant adjustment, and of joint activity. Instead of rational planning, implementation seems to be a matter of contexualisation, which is in line with both Ellström’s (1992) and Louis and Miles’ (1990) research. At the Thor school, for example, the process leaders combined several improvement strategies to meet the school’s preconditions and needs. They used the teachers’ experiences of an unclear organisation for improvement and of not having sufficient competence to teach heterogeneous groups. They used copying and adding to identify challenges such as the extensive amount of school improvement initiatives and the lack of collaboration and collegial learning. The process leaders found some of the challenges to be more significant than others and therefore decided that changes needed to be made immediately. Furthermore, they used alteration to develop common concepts and to support understanding of clarified improvement areas and roles among the teachers. With such constant adjustments, the process leaders contributed to the change of their organisations.

To sum up, our conclusion is that middle leaders, when assuming the role of translators, become central to the development of school organisations. Teachers, as middle leaders, are important actors when it comes to translating improvement strategies for school improvement.

One limitation in our study is that it is only based on interviews. We have not observed the translation practices, and therefore have to rely on what the participants tells us about the translations made. On the other hand, the process leaders, teachers, and principals in each specific case confirm each others’ opinions. Nevertheless, observations could have given a deeper understanding of how middle leaders translate ideas in the form of improvement strategies for use in their own organisations and what impact middle leaders’ translations have on local school organisations.

Another limitation is that we don’t known to what extent different types of translations contribute to different types of development. Previous research (Fairman & Mackenzie, 2015) shows that middle leaders need both a supporting and challenging approach to succeed in their mission. But to what extent do they challenge, and how does that affect the result of translations? What might have happened if, for example, the process leaders at the Vidar preschool had challenged the teachers and stood up for the original form of learning dialogue, instead of replacing the translation rule of copying with omission? This could be a relevant focus in further research, for example, in relation to aspects of control, conformism, and traditionalism (Sahlin-Andersson, 1996).

In our study, the middle leaders’ translation of ideas should not be seen as the single factor driving organisational change at the four establishments. However, the middle leaders were in many ways important as translators who could bring out the relevant ideas from tools and models, combine them with practical experience from their own school, and use ideas and experiences for a successful translation into their own practice. Being equipped with relevant models and tools is highly likely to have increased their legitimacy in middle leadership; this is an important factor, as such legitimaty is often contested (Bennett et al., 2007). Ways of gaining legitimacy are also important questions for further research.

A practical implication from our study is that it can be a worthwhile investment to provide middle leaders with several improvement strategies and let them practice these in a variety of settings over a period of time. When middle leaders are able to continually practice different strategies they seem to come to a deeper understanding of the strategies and how they can be contextualised. It helps them in what Røvik (2016) refers to as de-contexualisation, which seems to be important in translating ideas. Furthermore, middle leaders should be informed about theories of translation, to be aware of the importance of identifying the complexity of ideas and structures, as well as the needs in the local context. Our recommendation is to address these aspects in order to enable translations that aid development of school organisations (contextualisation). We hope that the results of this study will be a good starting point for other organisations in the process of improving their work based on middle leaders as translators, and that it might contribute to further research and knowledge in this area.

References

Andersson, R. (2011). Mainstreaming av integration: Om översättning av policy och nätverksstyrning med förhinder inom den regionala utvecklingspolitiken, 1998–2007 [Mainstreaming integration: About translation of policy and network steering prevented within the regional development policy, 1998–2007]. Dissertation, University of Linköping

Bennett, N., Woods, P., Wise, C., & Newton, W. (2007). Understandings of middle leadership in secondary schools: A review of empirical research. School Leadership and Management, 27(5), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/1363243070160613710.1080/13632430701606137

Björn, C., Ekman Philips, M., & Svensson, L. (Eds.). (2002). Organisera för utveckling och lärande: Om skolprojekt i nätverksform [Organising for development and learning: About school projects in the form of networks]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Blossing, U. (2008). Kompetens för samspelande skolor: Om skolorganisationer och skolförbättring [Competence for collaborative schools: About school organisations and school improvement]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Blossing, U. (2013). Förändringsagenter för skolutveckling: Roller och implementeringsprocess [Change agents for school improvement: Roles and process of implementation]. Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige, 18(3–4), 153–174.

Blossing, U. (2016). Practice among novice change agents in schools. Improving Schools, 19(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480215610953.

Blossing, U., Nyen, T., Söderström, Å., & Hagen Tønder, A. (2015). Local drivers for improvement capacity: Six types of school organisations. Dordrecht: Springer.

Boyaci, A., & Oz, Y. (2017). Evolution of teacher leadership as a challenging paradigm in rethinking and restructuring educational settings. In I. M. Amzat & N. P. Valdez (Eds.), Teacher empowerment toward professional development and practices (pp. 3–19). Perspectives across borders. Singapore: Springer.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Burke, W. W. (2008). A contemporary view of organization development. In T. G. Cummings (Ed.), Handbook of organization development (pp. 13–38). Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore: SAGE Publications.

Cantrell, S. C., Almasi, J. F., Carter, J. C., & Rintamaa, M. (2013). Reading intervention in middle and high schools: Implementation fidelity, teacher efficacy, and student achievement. Reading Psychology, 34(1), 26–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2011.577695

Czarniawska, B., & Jorges, B. (1996). Travels of ideas. In B. Czarniawska & G. Sevón (Eds.), Translating organizational change (pp. 13–48). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Czarniawska, B., & Sevón, G. (1996). Translating organizational change. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Day, C., & Harris, A. (2002). Teacher leadership, reflective practice and school improvement. In K. Leithwood & P. Hallinger (Eds.), International handbook of education administration (p. 975). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

de Nobile, J. (2018). Towards a theoretical model of middle leadership in schools. School Leadership & Management, 38(4), 395–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2017.1411902

Ellström, P.-E. (1992). Kompetens, utbildning och lärande i arbetslivet: Problem, begrepp och teoretiska perspektiv [Competence, education and learning in working life: Problems, concepts and theoretical perspectives]. Stockholm: Publica.

Fairman, J. C., & Mackenzie, S. V. (2015). How teacher leaders influence others and understand their leadership. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 18(1), 61–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2014.904002

Flyvbjerg, B. (2011). Case study. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 301–316). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Furu, E. M., & Lund, T. (2014). Development teams as translators of school reform ideas. In K. Rönnerman & P. Salo (Eds.), Lost in practice: Transforming Nordic educational action research (pp. 153–170). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Grootenboer, P., Edwards-Groves, C., & Rönnerman, K. (2015). Leading practice development: Voices from the middle. Professional Development in Education, 41(3), 508–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2014.924985

Harris, A., Jones, M., Ismail, N., & Nguyen, D. (2019). Middle leaders and middle leadership in schools: Exploring the knowledge base (2003–2017). School Leadership & Management, 39(3–4), 255–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1578738

Lander, R. (2009). Mobilisering av teknologi och organisation för skolans mål och tid [Mobilisation of technology and organisation in the service of school goals and time]. In R. Foss Lindblad & R. Lander (Eds.), Att säkra det osäkra: Reflektion och makt i skolans utvärdering [To secure the uncertain: Reflection and power in school evaluation] (pp. 15–32). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Lander, R., Blossing, U., Jarl, M., Milsta, M., Olin, A., & Rönnerman, K. (2013). Skolutveckling och differentiering för skolpersonalen [School development and differentiation for school staff]. In I. Wernersson & I. Gerrbo (Eds.), Differentieringens janusansikte [The Janus face of differentiation] (pp. 115–148). Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis.

Liljenberg, M. (2015). Distributed leadership in local school organisations. Working for school improvement? Dissertation, University of Gothenburg

Lindberg, K., & Erlingsdóttir, G. (2007). Förändring i skandinaviskt perspektiv: Nyinstitutionell teori och översättningssociologi Change in Scandinavian perspective: Neo-institutional theory and translation sociology. In D. Kärreman & A. Rehn (Eds.), Organisation: Teorier om ordning och oordning Organisation: Theories of order and disorder (pp. 31–44). Liber: Malmö.

Lindensjö, B., & Lundgren, U. P. (2000). Utbildningsreformer och politisk styrning [Educational reform and political governing]. Stockholm: Stockholms universitets förlag.

Louis, K. S., & Miles, M. B. (1990). Improving the urban high school: What works and why. New York: Teachers College Press.

Muijs, D., & Harris, A. (2003). Teacher leadership: Improvement through empowerment?. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nehez, J., Gyllander Torkildsen, L., Lander, R., Olin, A., & Blossing, U. (2017). På väg mot uppdrags- och processdrivna organisationer: Uppföljning av införandet av processledare i förskolor och skolor i Helsingborg [Towards task and process driven school organisations: A follow-up study of the introduction of process leaders in preschools and schools in Helsingborg]. Göteborg: University of Gothenburg. Available on http://hdl.handle.net/2077/52289

Nygård, S. R., & Røvik, K. A. (2014). Hit, men ikke lenger. Når Lean skal løftes inn i klasserommet Here, but no longer. When Lean should be lifted into the classroom. In K. A. Røvik, T. V. Eilertsen, & E. M. Furu (Eds.), Reformideer i norsk skole: Spredning, oversettelser og implementering Reform ideas in Norwegian school: Dispersion, translations and implementation (pp. 307–333). Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Olin, A., Lander, R., Blossing, U., Nehez, J., & Gyllander, L. (2014). Processledare för skolutveckling: Uppföljning av införandet av processledare i ett verksamhetsområde i Helsingborg. [Process leaders for school development: A follow-up study of introducing process leaders in parts of the municipality of Helsingborg]. Göteborg: University of Gothenburg. Available on http://hdl.handle.net/2077/35663.

Pålshaugen, Ø. (2000). The competitive advantage of development organizations. Concepts and Transformation, 5(2), 237–255. https://doi.org/10.1075/cat.5.2.05pal

Radaelli, G., & Sitton-Kent, L. (2016). Middle managers and the translation of new ideas in organizations: A review of micro-practices and contingencies. International Journal of Management Reviews, 18(3), 311–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12094

Rotvold, L. A., Rørnes, K., & Stjernstrøm, E. (2014). Klasseledelse: Fra nasjonal idé til lokal skoleutvikling [Classroom management: From national ideas to local school development]. In K. A. Røvik, T. V. Eilertsen, & E. M. Furu (Eds.), Reformideer i norsk skole: Spredning, oversettelser og implementering Reform ideas in Norwegian schools: Dispersion, translations and implementation (pp. 355–372). Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Røvik, K.-A. (1998). Moderne organisasjoner: Trender i organisasjonstenkingen ved tusenårsskiftet [Modern organisations: Trends in organisational thinking at the turn of the century]. Oslo/Bergen: Fagboksforlaget.

Røvik, K. A. (2016). Knowledge transfer as translation: Review and elements of an instrumental theory. International Journal of Management Reviews, 18(3), 290–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12097

Røvik, K. A., Eilertsen, T. V., & Furu, E. M. (Eds.). (2014). Reformideer i norsk skole: Spredning, oversettelser og implementering [Reform ideas in Norwegian schools: Dispersion, translations and implementation]. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Sahlin-Andersson, K. (1996). Innovation genom imitation: Om organisatoriska idéers spridning [Innovation through imitation: About dispersion of organisational ideas]. In P. af Segerstedt (Ed.), Idéer som styr: En antologi om bärande idéer i vetenskap och samhällsdebatt [Governing ideas: An anthology of core ideas in science and social debate] (pp. 77-93). Uppsala: Institutet för Personal- och företagsutveckling.

Spyridonidis, D., Currie, G., Heusinkveld, S., Strauss, K., & Sturdy, A. (2016). The translation of management knowledge: Challenges, contributions and new directions. International Journal of Management Reviews, 18(3), 231–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12110

Tiller, T. (1999). Aktionslärande: Forskande partnerskap i praktiken [Action learning: Research partnership in practice]. Stockholm: Runa förlag.

Uhl-Bien, M., & Arena, M. (2017). Complexity leadership: Enabling people and organizations for adaptability. Organizational Dynamics, 46(1), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2016.12.001

Wenner, J. A., & Campbell, T. (2017). The theoretical and empirical basis of teacher leadership: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 87(1), 134–171. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316653478

Wittbom, E. (2009). Att spränga normer: Om målstyrningsprocesser för jämställdhetsintegrering [Breaking norms: On management by objectives for gender mainstreaming]. Dissertation, University of Stockholm

Wæraas, A., & Agger Nielsen, J. (2016). Translation theory ‘translated’: Three perspectives on translation in organizational research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 18(3), 236–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12092

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the middle leaders, the teachers, and the principals who participated in the study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Halmstad University. Funded by a Swedish municipality.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest