Abstract

The primary goal of this paper is to understand the information structure of right dislocation (RD). I report a variation in RD in Asian languages with regard to the information structural status of the right dislocated elements. The discussion focuses on Alasha, a Mongolic language spoken in Mongolia. Through a comparative perspective on right dislocation, I show that RD languages come in two types: one that allows focused elements to be right dislocated, and one that disallows focused elements to be right dislocated. I argue that Alasha belongs to the former type, and I propose a bi-clausal analysis of Alasha RD, where Focus movement may occur in the second clause. Drawing on these findings, I further argue that the variation in RD is due to the parametric difference on the licensing condition of Focus Projection in Asian languages. Ultimately, the findings of this paper strengthen a non-uniform approach to RD in natural languages in both syntactic structure and information structure, despite their surface similarities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Since the distinction between topics, old information, background materials, or defocused/de-emphisized elements has no bearing on the proposal, I use the term topics and defocused elements as a cover term for these elements.

This is consistent with the proposal in Cheung (2009), which suggests that the host clause, but not the right dislocated elements, receive focus interpretation.

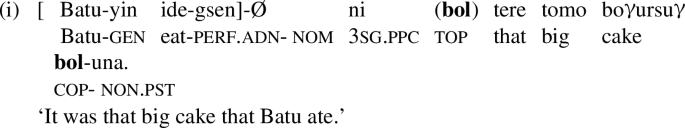

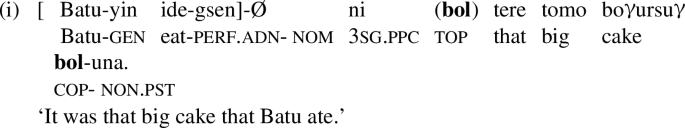

The dual status of bol can be further confirmed by their co-occurrence in a sentence. Bai (2023, p.110, adapted) reports the following (pseudo-)cleft sentence in Chakhar Mongolian, which contains both the topic marker bol, and the copula bol.

While the two sentences in ((11)) are reported to be truth-conditionally and information structurally identical, ((11b)b) may come with additional discourse effects, such as the creation of a sense of suspense. I leave this to future research.

The judgments for ((18b)b) reported by my five Cantonese consultants differ from the one reported in Lai (Lai (2019), p.250). My consultants point out that there is a contrast in acceptability between dislocation copying cases with and without focused elements.

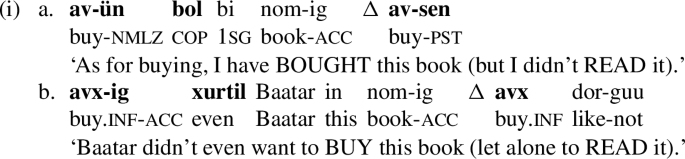

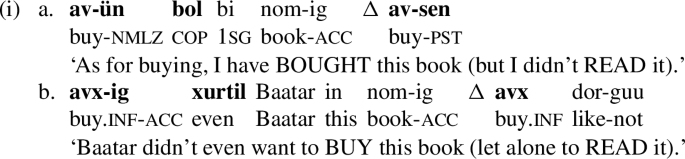

The first occurrence of the verb can alternatively appear in the sentence-initial position. For example,

While Abe (2019) specifically argues that Japanese RD involve focus movement, the focus nature of the right dislocated elements is not discussed in detail.

I assume the Topic projection may host old information, background materials, defocused elements.

Adjunct clause island violation appears to be less severe in RD cases compared to scrambling cases, but it is still degraded when compared to the baseline example.

Recall that, in footnote 8, I showed that the first occurrence of the verb in a verb doubling construction can appear sentence-initially, as long as it does not cross an island boundary.

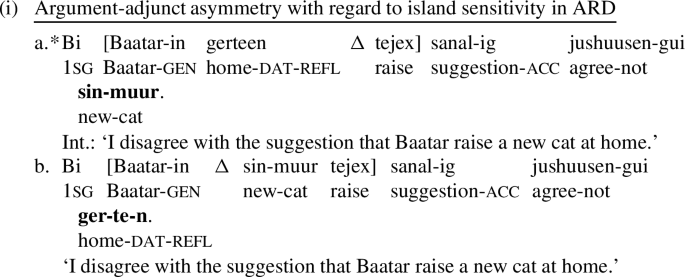

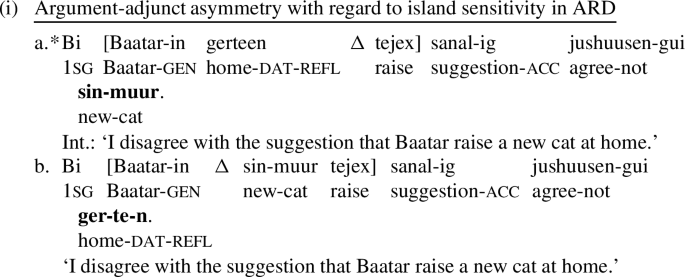

As opposed to RD of arguments and verbs, RD of adjunct is island-insensitive. The minimal pairs in (i) show that while RD of the object ‘(a) new cat’ in (ia) cannot escape the NP complement island, RD of the adjunct ‘at home’ is acceptable as shown in (ib).

The contrast implies that RD of adjuncts do not share the same derivation of RD of non-adjuncts (including arguments and verbs). In other words, while RD of non-adjuncts are derived via syntactic movement, RD of adjuncts are not. A similar split in RD cases has been reported in Korean RD (Ko 2015). It is possible that RD of adjuncts in Alasha is derived via Late Merge, in a way proposed for Korean RD (Ko 2022b). Since RD of adjuncts appear to be a more specific case in RD, I set aside this sub-type of RD and focus on RD of non-adjuncts for the rest of the paper.

The argument here builds on Takita (2011) in his discussion on Japanese RD.

Lai (2019, p.250) reports that the sentence in (i) is acceptable. While two out of five of my consultants accept the sentence in (i), the other three consistently judge the sentences in ((46)) to be unacceptable.

I am grateful for this suggestion by an anonymous reviewer.

In Abe (2019), the pro is taken to be a less specified empty category, and he suggests that the sentence receives an interpretation in (i).

He argues that RD under a bi-clausal analysis would fail to serve as an answer because “it asserts what the question presupposes, namely the first part of the interpretation just given." The validity of this explanation relies on the unspecified nature of the empty category. I stick to the more specific, pro analysis.

Similar observations are reported in Öztürk (2013) in Khalkha Mongolian.

I thank Yaqing Hu for pointing out this contrast to me.

In Lee (2017), the two preposing operations are sequential (i.e., the second one involves remnant movement), whereas in Lai (2019) they are simultaneous (creating parallel movement chains). Since the precise implementation of a double preposing approach has no bearing on the discussions here, I abstract away from their differences.

I do not discuss the single preposing approaches as proposed in Cheung (1997, 2009), and Wei and Li (2018), which rely heavily on a head-initial analysis of SFPs in Chinese languages. The head-initial analysis of SFPs is partly motivated by the so-called Final-Over-Final Constraint (Biberauer et al. 2008, and many subsequent works), which suggests a cross-linguistic absence of a head-final structure that dominates a head-initial structure. Since Alasha, as with other Mongolic varieties, is consistently head-final in the verbal domain, it lacks such a motivation for a head-initial analysis of SFPs, and it is most natural to assume a head-final analysis of SFPs in the extended verbal projection.

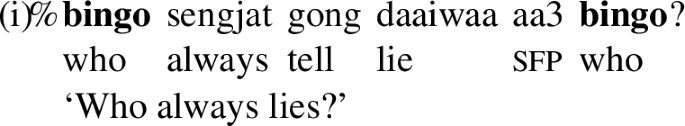

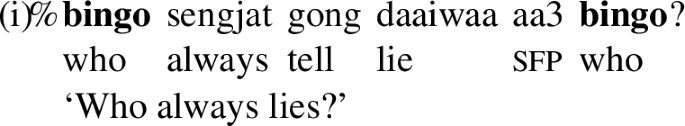

This represents a general challenge to a bi-clausal approach on RD constructions, which is mostly left ignored in existing literature (e.g., Abe 1999, 2019; Öztürk 2013). In some version of a bi-clausal analysis of RD (e.g., Tanaka 2001), the SFP is deleted altogether with the TP in the second clause. This might be possible if the SFP resides in a TP projection, but this is less likely to be the case for question particles, which typically take scope over the whole clause.

Abe (2019, p.3) states that “it would be a mistake to regard the relation of the two clauses in [a RD construction] as conjunction, since these two clauses basically repeat the same proposition. It is more appropriate to regard them as involving clause repetition." Abe makes reference to the earlier suggestion by (Kuno 1978, p.61-62) that “ Japanese RD construction involves a process that ‘adds afterthoughts to the end of a sentence". A similar suggestion is suggested in Öztürk (2013, p.192) in his discussions on RD in Khalkha Mongolian: “the post-verbal material is more like an afterthought, which is typically used to help identify a potentially ambiguous referent."

This is consistent with the suggested derivation in ((40)), where the two clauses in RD are not lexically/formally identical, but only identical in terms of propositional content.

This amounts to a semantic restriction on clausal repetition. Alternatively, this can be formulated as a syntactic restriction on what can be conjoined with the host clause. For example, there may be a size restriction on the right-branching specifier position of the SFP projection that hosts the right-dislocated elements. I leave the possibility open.

As for Korean RD, Ko (2015) suggests that \(\alpha \) can host focus elements (i.e., specificational focus), and she argues for a mono-clausal analysis in Korean RD. If so, Korean represents a counter-example to the correlation in ((61)). However, the mono-clausal vs. bi-clausal debates in Korean RD remain controversial; for an overview, see Ko (2022a). I do not count on the Korean case to argue against the validity of ((61)).

This is in line with Japanese RD, as discussed in Abe (2019).

The idea here owes an intellectual debt to Abe (2019), where he explores the activation condition of FocusP in Japanese.

As we will see shortly in the next subsection, languages such as Cantonese and Mandarin fail to derive sluicing-like constructions via movement, i.e., what looks “sluiced" is indeed base generated.

Tanaka (2001), among others, has also noted the connection between sluicing-like constructions and RD constructions in Japanese.

See Hiraiwa and Ishihara (2012) for two possible derivations.

The copula da is taken to be the Focus head, which can be overt, since the proposed parameter only regulates the covert/overt nature of the complement of FocusP.

The data here is given in Chakhar Mongolian, but it is presumably extendable to Alasha Mongolian.

Indeed, Ishihara (2001) suggests that the scrambled elements in Japanese must be interpreted as given, i.e., they cannot be included in the (narrow) focus set.

No such requirement applies to TopicP, as topics/defocused elements can be right dislocated; The sentence becomes acceptable, if FocusP moves together with the TP. This would result in the OSV-sfp word order, e.g., sentences in ((74)) discussed below; cf. Cheung (2009)).

Indeed, this amounts to an explanation of why sluicing-like constructions in Cantonese and Mandarin must adopt a base generation derivation, even though focus movement and TP deletion are independently available in these languages.

I have grayed the row of RD structure as it is not correlated with other observations, as discussed in Sect. 5.1.

References

Abe. 1999. On directionality of movement: A case of Japanese right dislocation. Ms: Nagoya University.

Abe, Jun. 2019. Focus licensing at the left periphery in Japanese right dislocation. Syntax 22 (1): 1–23.

Adams, Perng Wang, and Satoshi Tomioka. 2012. “Sluicing in Mandarin Chinese: An instance of pseudo-sluicing.” In Sluicing: Cross-linguistic perspectives, edited by Jason Merchant and Andrew Simpson, 219-247. Oxford University Press.

Aravind, Athulya. 2021. Successive cyclicity in DPs: Evidence from Mongolian nominalized clauses. Linguistic Inquiry 52 (2): 377–392.

Badan, Linda. 2007. High and low periphery: A comparison between Italian and Chinese. Ph.D. diss.: Università Degli Studi di Padova.

Bai, Xue. 2023. An exploration of multiple sluicing from a cross-linguistic perspective. Ph.D. diss.: Tohoku University.

Bhatt, Rajesh, and Veneeta Dayal. 2007. Rightward scrambling as rightward remnant movement. Linguistic Inquiry 38 (2): 287–301.

Bhattacharya, Tanmoy, and Andrew Simpson. 2012. “Sluicing in Indo-Aryan: Aninvestigation of Bangla and Hindi.” In Sluicing: Cross-linguistic perspectives, edited by Jason Merchant and Andrew Simp-son, 183–218. Oxford University Press.

Biberauer, Theresa, Anders Holmberg, and Ian G. Roberts. 2008. “Disharmonic word-order systems and the Final-over-Final Constraint (FOFC).” In Proceedings of XXXIII Incontro di Grammatica Generativa. Edited by A. Bisetto and F. Barbieri, 86–105.

Butt, Miriam, and Tracy Holloway King. 1996. “Structural topic and focus without movement.” In Proceedings of the first LFG conference. 1995. Standord, CA: CSLI Publications.

Cheng, Lisa Lai-Shen., and Luis Vicente. 2013. Verb doubling in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 22 (1): 1–37.

Cheung, Candice Chi-Hang. 2008. Wh-fronting in Chinese. PhD diss.: University of Southern California.

Cheung, Candice Chi-Hang. 2015. “On the fine structure of the left periphery.” In The cartography of Chinese syntax, edited by Wei-Tien Dylan Tsai, 75–130. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cheung, Lawrence Yam-Leung. 1997. A study of right dislocation in Cantonese. MA thesis, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Cheung, Lawrence Yam-Leung. 2009. Dislocation focus construction in Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 18 (3): 197–232.

Cheung, Lawrence Yam-Leung. 2015. Bi-clausal sluicing approach to dislocation copying in Cantonese. International Journal of Chinese Linguistics 2 (2): 227–272.

Chiang, Yu-Chuan Lucy. 2017. “A movement analysis of right dislocation: The case of Mandarin chinese.” In Proceedings of the 29th North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics, edited by Lan Zhang, 2:304–315. Memphis, TN.

Chiang, Yu-Chuan Lucy. 2022. Ellipsis analysis for Mandarin Chinese right dislocation? Manuscript: University of Michigan.

Dayal, Veneeta. 1996. Locality in Wh-Quanti-cation: Questions and relative clauses in Hindi. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Dayal, Veneeta. 2003. Bare nominals: Non-specific and contrastive readings under scrambling. In Word order and scrambling, edited by Simin Karimi, 67–90. Blackwell Publishing.

Fukaya, Teruhiko, and Hajime Hoji. 1999. Stripping and sluicing in Japanese and some implications. Proceedings of WCCFL-18:1–15.

Georgi, Doreen, and Mary Amaechi. 2022. Resumption in Igbo: Two types of resumptives, complex phi-mismatches, and dynamic deletion domains. Ms: University of Potsdam, University of Ilorin.

Gong, Zhiyu Mia. 2022. “Case in wholesale late merger: Evidence from Mongolian scrambling.” Linguistic Inquiry: 1–66.

Hein, Johannes. 2018. Verbal fronting: Typology and theory. PhD diss.: Universität Leipzig.

Hiraiwa, Ken, and Shinichiro Ishihara. 2002. "Missing links: Cleft, sluicing, and “Noda" construction in Japanese”. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 43:35–54.

Hiraiwa, Ken, and Shinichiro Ishihara. 2012. Syntactic metamorphosis: Clefts, sluicing, and in-situ focus in Japanese. Syntax 15 (2): 142–180.

Irani, Ava. 2014. Focusing in Hindi Syntax. Master Thesis, Georgetown University.

Ishihara, Shiniiichiro. 2001. “Stress, focus and scrambling in Japanese.pdf.” In MIT working papers in linguigstics 39, edited by Elena Guerzoni and Ora Matushansky, 151–185. Cambridge, MA: MITWPL.

Janhunen, Juha A. 2012. Mongolian. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Kidwai, Ayesha. 2022. “Unlabeled structures and scrambling asymmetries: Hindi-Urdu style.” In Proceedings of (F)ASAL-11, edited by Samir Alam, Yash Sinha, and Sadhwi Srinivas.

Ko, Heejeong. 2015. Two ways to the right: A hybrid approach to right-dislocation in Korean. Language Research 51 (1): 3–40.

Ko, Heejeong. 2022. Right-dislocation in Korean: An overview. In Cambridge handbook of Korean linguistics, ed. Sungdai Cho and John Whitman, 339–375. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ko, Heejeong. 2022b. Two types of Late Merge : Evidence from adjunct stranding and extraposition. Paper presented on WAFL-16, Rochester University, 30 Sept–2 Oct 2022.

Kuno, Susumu. 1978. Danwa No Bunpo [Grammar of Discourse]. Tokyo: Taishukan Shoten.

Lai, Jackie Yan-ki. 2019. Parallel copying in dislocation copying: Evidence from Cantonese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 3: 243–277.

Landau, Idan. 2006. Chain resolution in Hebrew V(P)-fronting. Syntax 9 (1): 32–66.

Lee, Tommy Tsz-Ming. 2017. Defocalization in Cantonese right dislocation. Gengo Kenkyu 152: 59–87.

Lee, Tommy Tsz-Ming. 2020. Defending the notion of defocus in Cantonese. Current Research in Chinese Linguistics 99 (1): 137–152.

Lee, Tommy Tsz-Ming. 2021. Asymmetries in doubling and cyclic linearization. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 30 (2): 109–139.

Lee, Tommy Tsz-Ming. 2022. Towards the unity of movement: Implications from verb movement in Cantonese. PhD diss.: University of Southern California.

Li, Yen-Hui Audrey, and Ting-chi Wei. 2014. “Ellipsis.” In The Handbook of Chinese Linguistics, edited by C.-T. James Huang, Yen-hui Audrey Li, and Andrew Simpson, 275–310. John Wiley/Sons.

Li, Yen-Hui Audrey., and Ting-chi Wei. 2017. Sluicing, sprouting and missing objects. Studies in Chinese Linguistics 38 (2): 63–92.

Mahajan, Anoop. 1990. “The A/A-bar distinction and movement theory.” Ph.D. diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Manetta, Emily. 2012. Reconsidering Rightward Scrambling: Postverbal Constituents in Hindi-Urdu. Syntax 43 (1): 43–74.

Murayama, Kazuto. 1999. An argument for right dislocation Japanese. Kanda University of International Studies 5: 45–62.

Nakagawa, Natsuko, Yoshihiko Asao, and Naonori Nagaya. 2008. Information structure and intonation of right-dislocation sentences in Japanese. Kyoto University Research Information Repository 27: 1–22.

Nunes, Jairo. 2004. Linearization of chains and sideward movement. Linguistic inquiry monographs. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ott, Dennis, and Mark de Vries. 2016. Right-dislocation as deletion. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 34 (2): 641–690.

Öztürk, Balkiz. 2013. Rightward movement, EPP and speciers: Evidence from Uyghur and Khalkha. In Rightward movement in a comparative perspective, ed. Gert Webelhuth, Manfred Sailer, and Heike Walker, 175–210. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Pan, Victor Junnan. 2019. Architecture of the periphery in Chinese. New York: Routledge.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. “The fine structure of the left periphery.” In Elements of grammar, edited by Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Rochemont, Michael. 1986. Focus in generative grammar. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Sakamoto, Yuta. 2014. “Absence of case-matching effects in Mongolian sluicing.” In Proceedings of WAFL-9, 1–6.

Scott, Tessa. 2021. Two types of resumptive pronouns in Swahili. Linguistic Inquiry 52 (4): 812–833.

Shyu, Shuing. 1995. “The syntax of focus and topic in mandarin Chinese.” PhD diss., University of Southern California.

Simon, Mutsuko Endo. 1989. “An analysis of the postposing construction in Japanese”. PhD diss., The University of Michigan.

Simpson, Andrew, and Arunima Choudhury. 2015. The non uniform syntax of Postverbal elements # in SOV Languages: Hindi, Bangla, and the rightward scrambling debate. Linguistic Inquiry 46 (3): 533–551.

Simpson, Andrew, and Zoe Wu. 2002. “Understanding cyclic spell-out.” In Proceedings of North East Linguistic Society 32, edited by Masako Hirotani, 2:499–518.

Svantesson, Jan-Olof. 2003. Khalkha. In Mongolian, ed. Juha A. Janhunen, 154–176. London: Routledge.

Sybesma, Rint. 1999. The Mandarin VP. Amsterdam: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Syed, Saurov. 2015. “Focus-movement within the Bangla DP.” In Proceedings of WCCFL-32, pp. 332–341.

Takami, Ken-ichi. 1995. Kinootekikoobunron niyoru nichieigohikaku: ukemibun koochibun no bunseki [A Comparison of Japanese and English in Functional Theories: an Analysis of Passive and Postposing Constructions]. Tokyo: Kuroshio.

Takano, Yuji. 2014. Japanese Syntax in Comparative Persp. In Japanese Syntax in Comparative Perspective, ed. Mamoru Saito, 139–180. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Takita, Kensuke. 2011. “Argument ellipsis in Japanese right dislocation.” In Japanese/Korean Linguistics 18, edited by William McClure and Marcel den Dikken, 380–391. CSLI Publications.

Tanaka, Hidekazu. 2001. Right-dislocation as scrambling. Journal of Linguistics 37 (3): 551–579.

Trinh, Tue. 2009. A constraint on copy deletion. Theoretical Linguistics 35 (2–3): 183–227.

van Urk, Coppe. 2018. Pronoun copying in Dinka Bor and the copy theory of movement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 36 (3): 937–990.

Vicente, Luis. 2007. “The syntax of heads and phrases: A study of verb (Phrase) Fronting”. PhD diss., Universiteit Leiden.

Wei, Ting-Chi. 2004. “Predication and sluicing in Mandarin Chinese”. PhD diss., National Kaohsiung Normal University.

Wei, Ting-Chi. 2011. Island repair effects of the left branch condition in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 20 (3): 255–289.

Wei, Wei Haley, and Yen-Hui Audrey. Li. 2018. Adverbial clauses in Mandarin Chinese. Linguistic Analysis 1–2: 163–330.

Yamashita, Hideaki. 2011. “An(other) argument for the “repetition” analysis of Japanese right dislocation: evidence from the distribution of thematic topic-wa.” In Japanese/Korean Linguistics 18, edited by William McClure and Marcel den Dikken, 410–422. CSLI Publications.

Yip, Ka-Fai. 2020. Syntax-prosody Mapping of right-dislocation in Cantonese and Mandarin. In Phonological externalization, vol. 5, ed. Hisao Tokizaki, 73–90. Sapporo: Sapporo University.

Yip, Ka-Fai, and Comfort Ahenkorah. 2023. “Non-agreeing resumptive pronouns and partial Copy Deletion.” University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 29(1).

Yip, Ka-Fai, and Xuetong Yuan. 2023. “Defocus leads to syntax-prosody mismatches in right-dislocated structures.” In Proceedings of CLS 59.

Acknowledgements

My sincere thanks go to my consultant, Brian Tsagaadai, for judgments and discussions, without whom this project would not have be possible. For comments and suggestions, I thank Xue Bai, Travis Major, Andrew Simpson, and Ka-Fai Yip, and the participants in the USC Field Method class (2022, Spring). I am also grateful to the audience at WAFL 16 (Rochester University).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, T.TM. Last but not least: a comparative perspective on right dislocation in Alasha Mongolian. J East Asian Linguist 32, 459–495 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-023-09266-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-023-09266-6