Abstract

The present article provides a case study of the forms corresponding to the meaning ‘small’ in Swedish, which exhibit a number-based suppletive alternation: descriptively, liten appears in the singular while små appears in the plural. We demonstrate that this alternation is best treated as contextual allomorphy, and provide six arguments that favor this account over a plausible alternative, according to which the forms realize two distinct roots with different lexical semantics. We situate a Distributed Morphology-based account of the alternation within the broader context of inflection in the language, and address challenges and complications to the allomorphy approach from outside of the root’s ‘typical’ adjectival contexts, including adverbs and compounding. This study supports the existence of root suppletion conditioned by inflectional features, and has implications for our understanding of locality conditions on root suppletion as well as contextual allomorphy more broadly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Recent work within the Distributed Morphology (DM) framework has pursued the idea that what is descriptively called ‘root suppletion’ is reducible to contextual allomorphy at or involving a root node (Bobaljik 2012, 2015b; Haugen and Siddiqi 2013; Harley 2014a, b, 2015; Arregi and Nevins 2014; Moskal 2015a, b; Toosarvandani 2016; Bobaljik and Harley 2017; Gribanova 2017; Thornton 2019; among others). Under this approach, suppletive alternations of roots are treated in the same way as formal alternations of functional morphemes: two (or more) exponents compete for realization postsyntactically, with the competition being resolved via the Elsewhere Condition or the Subset Principle (Halle 1997). This is schematized in (1), where a single root in the syntax (identified abstractly by some index) is realized as the b alternant in the context of a feature [\(\beta \)], and as the a alternant elsewhere. We refer to this as a ‘Same Root Analysis’ (SRA).

SRAs have become especially important in DM, as root suppletion has played a role in developing the theory of locality restrictions on contextual allomorphy, and of root individuation in syntax. However, it remains somewhat of a controversy whether root suppletion is best characterized as genuine allomorphy; according to a competing view, roots are individuated by their formal identity, and putative alternants are in fact different roots altogether, identified by their phonological profile (Borer 2014). This latter approach then interestingly diverges from an SRA if the root representations (2) map to differences inherent to their lexical semantics, with these differences accounting for the distributional split between the putative alternants.Footnote 1 We refer to this as a ‘Different Root Analysis’ (DRA).

The current study pits these two competing hypotheses against each other for a well-known case of (putative) suppletion in Swedish, the alternation between liten ‘small.sg’ and små ‘small.pl’, by using a set of diagnostics that assess root identity. (See Börjars and Vincent 2011 for an extensive discussion of the historical context of this suppletive pattern, and Corbett 2007 and references therein for discussion of the related pattern in Norwegian dialects, some of which employ a distinct form vesle ‘small’ in definite contexts.) According to an SRA, liten and små realize the same root, with the choice between allomorphs being conditioned by number features. According to a DRA, the two forms correspond to roots with related meanings that are distinguished by number semantics inherent to the root (e.g., liten is inherently specified to mean ‘small and atomic’).

Special attention is paid to situating the suppletive pattern within the system of inflectional exponence in the language. The study supports an SRA over a DRA, though the SRA is not altogether without challenges, an issue which is often set to the side in other work on suppletion, but which is addressed presently.

Empirically, the current work adduces novel evidence supporting an SRA of an alternation seen with an adjective (and its related derivatives) tracking an agreement feature, namely number. This type of suppletion has been claimed to be exceptional cross-linguistically, as it is sometimes taken to be the case that most instances of root suppletion track ‘inherent’ features (e.g., number on nouns); see, for example, Hippisley et al. (2004).

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides background on Swedish adjective inflection and the basic distributional characteristics of liten and små. Section 3 contrasts an SRA with a DRA, demonstrating that the SRA is favored. Section 4 examines potential challenges to an SRA, and demonstrates how an articulated view of structure, in combination with the SRA and some theoretical refinement, can capture seemingly complex patterns. Section 5 contextualizes the alternation within theories of allomorphy and locality. Section 6 offers concluding remarks.

2 Background

Adjectives in Swedish inflect for gender (common vs. neuter) and number (singular vs. plural) in both predicative and attributive positions (Holmes and Hinchliffe 2020,46). The formal alternation in (3) is the ‘strong’ pattern. (Exponence of the strong forms is subject to some minor points of morphophonological variation for other adjectives; see Holmes and Hinchliffe 2020,47–50.) As evident from (3), the gender contrast between common and neuter is neutralized in the plural. There is also the ‘weak’ pattern, which (roughly speaking) arises for modifiers in definite environments. For this pattern, the inflection on prenominal attributive adjectives neutralizes formal alternations for gender and number (4).Footnote 2Footnote 3

The basic inflectional pattern of adjectives is represented in Tables 1 and 2. Observe that the weak form is identical to the strong plural.

For concreteness, we take the agreement morpheme to be a node sprouted at PF (Kramer 2009; Norris 2014; Adamson 2019a; Choi and Harley 2019; among others), which we label aInfl, and which we take to be adjoined to a complex head a consisting (minimally) of the combination of a \(\sqrt{{\textsc {root}}}\) with an adjectivizing head (5) (which can be realized as \(\varnothing \)). This formulation is adopted from Adamson (2019a), whereby the adjunction of the inflectional head targets a complex head, specifically a ‘Morphological Word’ (MWd) in Embick and Noyer’s (2001) sense.

The identity across the weak and plural forms is often taken to indicate that the exponent −a is the elsewhere item (Sauerland 1996; Embick 2015). We adopt Sauerland’s (1996) analysis (which readily extends from Norwegian to Swedish), whereby gender features are impoverished in weak environments (6), and the inflectional endings correspond to the Vocabulary Items in (7). (See also Julien 2005, and Norris et al. 2014 for a related approach with underspecification).

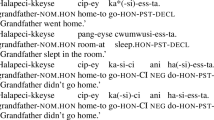

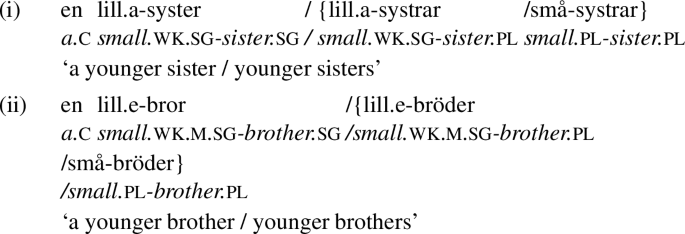

We now turn to liten and små. Observe from Table 3 that liten patterns in its singular strong forms with other adjectives that end in unstressed / n/ (see Holmes and Hinchliffe 2020,49), with corresponding morphophonological alternations of the base (i.e., deletion of the nasal for the neuter singular form). However, the expected plural or weak form litna does not exist; in weak singular environments, the correct realization is formed from the base lill.Footnote 4 For the plural, the form små appears in both strong and weak environments. The differences in form between strong (8)–(9) and weak (10)–(11) environments are shown below.

n/ (see Holmes and Hinchliffe 2020,49), with corresponding morphophonological alternations of the base (i.e., deletion of the nasal for the neuter singular form). However, the expected plural or weak form litna does not exist; in weak singular environments, the correct realization is formed from the base lill.Footnote 4 For the plural, the form små appears in both strong and weak environments. The differences in form between strong (8)–(9) and weak (10)–(11) environments are shown below.

This distribution can be captured with a Same Root Analysis along the lines of 12, where the number feature of aInfl conditions the exponence of the root. Analogous to the Vocabulary Items in 7, the singular form is more specific, with små being the elsewhere item.

We adopt the view that lill is derived via morphophonological change from the form liten (in the sense of Harley and Tubino-Blanco 2013; Embick and Shwayder 2018; among others), in the context of the feature [wk], though the alternation could instead be formulated as contextual allomorphy; nothing crucial will hinge on this. That these are related forms is in line with their shared historical origin: according to the Svenska Akademiens Ordbok, they are both descendants of (forms of) Old Swedish litl.

The distribution of liten and små is correctly derived from the Vocabulary Items in 12, and importantly, are consistent with the impoverishment rule in 6, which does not affect number features, and consequently has no impact on the choice between the Vocabulary Items in 12 in weak environments.Footnote 6 However, as the system currently stands, it is expected that the plural and weak forms should be småa, rather than små. There are in fact adjectives with a similar phonological profile, including blå ‘blue’ and grå ‘gray’, which for some speakers have inflected forms blå-a and grå-a, but optionally allow deletion of the final -a (see, e.g., Holmes and Hinchliffe 2020,47). We take the derivation of små to involve the same morphophonological deletion, though at least for the speakers we have consulted, the rule in this case is obligatory.

We have established what the SRA would look like for the liten\(\sim \)små alternation. Before proceeding, we note that there are at least three motivations that point to an SRA (cf. Borer 2014,351). First, number is a formal feature that affects the realization of adjectival inflection more generally in the language, so the alternation liten\(\sim \)små can be treated as a special case of this formal distinction; this is often (though not always) considered a precondition for root suppletion. Second, at least within the domain of adjectives, the forms are in complementary distribution with each other, unlike little vs. small in English, which are frequently interchangeable. As noted by Harley (2014b), a DRA would treat complementarity as accidental (in terms of form), while it falls naturally out of an SRA, which treats the relation between alternants as systematically related via (allomorphic) competition. Lastly, native speakers have the intuition that the forms are linked to each other, again unlike English small vs. little. These motivations aside, we can demonstrate that an SRA fares better than a DRA empirically. We now turn to this comparison.

3 Evidence for suppletion

In this section, we contrast a Same Root Analysis of suppletion (SRA) with a Different Root Analysis (DRA) through a study of several phenomena for which the two make distinct predictions, namely for morphological idiosyncrasy, interpretive idiosyncrasy, equative degree constructions, nominal and predicate ellipsis, contradiction tests, and nominalization. While some of these tests are familiar from the literature (Harley 2014a, 2015; among others), not all are, as far as we are aware—particularly equatives, nominal ellipsis, contradiction, and nominalization. In all such cases, an SRA makes correct predictions while a DRA does not.

Recall that an SRA treats the alternants in terms of contextual allomorphy, as in 12. There are in principle a number of different SRAs that can capture the basic set of alternations, though the specific predictions of such analyses vary in part according to the set of assumptions that are made regarding what is ‘visible’ for contextual allomorphy. All theories of allomorphy within DM share the view that only local elements can condition the choice between allomorphs, though there is no strong consensus on what constitutes ‘local’. Crucially, though, across different theories, if there is no local element to condition the allomorphy, realization will be for the elsewhere item (the ‘default’).

For concreteness, the SRA we consider throughout is that of 12, which takes the elsewhere realization to be the ‘plural’ form små. This form is thus predicted by our SRA to appear when number features are not present, or when they are not local to the root.

While we do not take the primary objective of the current article to be to advance a specific view of locality, we make our assumptions explicit presently and discuss implications of the liten/små alternation for theories of locality in Sect. 5. We adopt the view that cyclic derivation from the root outwards constrains allomorph selection (Bobaljik 2000; Embick 2010; Moskal 2015b; among others), and that lexical heads (e.g., a, n, etc.) are cyclic. More specifically, we adopt the view that allomorph selection cannot ‘see’ a second cyclic head or above (Embick 2010).Footnote 7 We do not adopt, however, Embick’s linear condition on allomorphy, which has been challenged by multiple researchers (Smith et al. 2018; among others).

We follow Bobaljik (2012) in taking only elements internal to a complex head (or MWd) to be visible for contextual allomorphy (see also Thornton 2019; Choi and Harley 2019).Footnote 8 In terms of adjacency conditions, we follow Choi and Harley (2019) in taking structurally closer elements to take precedence over further elements in allomorph selection (see relatedly Toosarvandani 2016). For both domain and adjacency conditions, we follow the formulations spelled out by Choi and Harley (2019):

We stress that the current focus here is to distinguish between the fundamental predictions of an SRA and a DRA, both of which may have several variants, though the particular SRA we consider throughout is assumed to be subject to the locality conditions on allomorphy detailed here, which prevent number features from conditioning insertion at the node \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) if they are nonlocal. The precise role that cyclicity and the conditions in 13 play in the analysis will become apparent below.

In contrast to an SRA, a DRA takes the alternants to be realizations of altogether different roots, which differ from each other in terms of their lexical semantics. Under this view, each root directly encodes semantic number, or is otherwise only semantically compatible with either singular or plural number. (For comparison, consider that an adjective like ‘numerous’ is not semantically compatible with a singular noun.) Their complementary distribution would then not be encoded in terms of the morphology, but rather, would owe to their differences in meaning. A sample set of Vocabulary Items for this type of DRA is provided in 14.Footnote 9

Other incarnations of a DRA are conceivable; our diagnostics rule out these alternatives, as well.

We now discuss six types of evidence that support an SRA over a DRA: shared morphological idiosyncrasy 3.1, shared idiosyncratic interpretation 3.2, equative degree constructions 3.3, nP and predicate ellipsis 3.4, contradiction tests 3.5, and nominalization 3.6.

3.1 Shared morphological idiosyncrasy

Shared irregular allomorphy or morphophonology provides evidence of morpheme identity (e.g., Aronoff 1976; Creemers et al. 2020). For example, the identity of stand in both with-stand and under-stand is evidenced by the fact that they share an irregular alternation of the base in their past tense (stood, with-stood, under-stood), despite their opaque meaning relations to the verb stand. In DM, this co-patterning is expected, because the conditioning environments for contextual allomorphy are the same across incarnations of the root \(\sqrt{{\textsc {stand}}}\) (under certain perspectives on locality conditions).

This logic can be extended to root-suppletive exponents. If two exponents A and B realize the same root, then putting the root into a context that conditions an irregular allomorph C should do so in both environments that would otherwise condition A or B (provided that the conditioning element for C is local). This is implicit in Bobaljik’s (2012,118–119) treatment of the English adverb well, which, like good, has the comparative form bett-er (*well-er, *more good(ly)). Assuming the adverb is built off the comparative, the suppletive relationship can be represented with the Vocabulary Items in 15. Setting aside the non-trivial issue of composition of the adverbial head and the comparative, the suppletive analysis of good/well captures the formal convergence for the comparative.

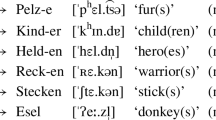

Turning now to Swedish, we find a comparable convergence of irregular allomorphy for liten and små. Synthetic comparatives in Swedish are formed with -(a)re, and superlatives with -(a)st. Thus the positive forms lätt ‘light’, snabb ‘fast’, vacker ‘beautiful’ become respectively lättare, snabbare, and vackrare in the comparative and lättast, snabbast, and vackrast in the superlative (compare also äldre/äldst ‘older, oldest’ and bättre/bäst ‘better, best’, which have the ‘abbreviated’ forms -re and -st). The Vocabulary Items for the comparative and superlative morphemes are given in 16. We follow Bobaljik (2012,34–35) in taking the superlative to contain the comparative, and follow his suggestion (for other languages) that the comparative head is realized as null in the context of the superlative.

Like the positive weak forms, the comparative and superlative do not alternate according to gender and number, though superlatives are inflected (i.e., with -a) across feature combinations in attributive positions (e.g., vackr-ast-a ‘beautiful-sprl-wk’). When inflectional affixes are present, they are further from the root than the comparative or superlative head. This is represented in the tree in 17. We assume the comparative and superlative heads adjoin to the head a (through, for example, postsyntactic merger) prior to the node-sprouting of aInfl (see Adamson 2019a). (In the case of the comparative, we assume the aInfl node is realized as \(\varnothing \) when adjacent to the cmpr node.)

An SRA predicts that irregular allomorphy of the root in the context of the comparative or the superlative should be shared across singular and plural environments. This should hold because the comparative or superlative morpheme is local to the root, and should therefore be eligible to condition its allomorphy. This contrasts with aInfl, which under certain assumptions, cannot condition allomorphy past the intervening cmpr or sprl heads. Presently, this is captured by the Local Allomorph Selection Theorem, which gives rise to the choice of the comparative/superlative alternant over the singular/plural alternants because the former is more local than the latter; other adjacency-based perspectives on allomorphy similarly derive this difference (Embick 2010; Bobaljik 2012; among others).

The SRA predictions are borne out. The comparative and superlative of \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) are respectively mindre and minst, regardless of number, as illustrated in 18–20.Footnote 10

Under an SRA, the Vocabulary Items for \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) are simply expanded, as in 21, subject to the condition that the more local element (the cmpr/sprl head) conditions the exponence while the element further away (aInfl) cannot.

In contrast to an SRA, a DRA does not make correct predictions. A DRA would posit a separate root \(\sqrt{{\textsc {min(d)}}}\), which would have inherently comparative semantics. Blocking the impossible litnare and småare would be non-trivial, but could be accomplished essentially by making the semantics of distinct roots \(\sqrt{{\textsc {liten}}}\) and \(\sqrt{{\textsc {sm}}\mathring{\textsc {a}}}\) incompatible with comparative semantics.

That a DRA is on the wrong track is indicated by (at least) two comparative environments in which liten and små do in fact appear: metalinguistic comparatives and analytic comparatives with conjoined adjectives.Footnote 11

Metalinguistic comparatives are known in English to prohibit synthetic forms, as in 22; an analytic comparative with more is used instead (DiSciullo and Williams 1987; Embick 2007; among others). The same holds in Swedish with mer 23.

As the examples in 24 show, the forms liten and små may appear (with mild degradation) in metalinguistic comparatives, which is inconsistent with the idea that these forms expone distinct roots whose interpretations are incompatible with comparative semantics. For an SRA, the choice of the forms liten and små over min(d) in analytic comparatives is consistent with Bobaljik’s (2012,3) Root Suppletion Generalization, according to which root suppletion is conditioned in the context of synthetic—but not analytic—comparatives. This is derived presently by an SRA coupled with the Complex Head Accessibility Domain condition 13, which restricts allomorphic conditioning to complex heads.

The other construction that points to the same conclusion involves coordinated adjectives. In Swedish, as in English, coordinated adjectives can appear in analytic comparatives even when the conditions for producing a synthetic form are met for one of the adjectives 25 (cf. sötare ‘cuter’). The choice of allomorphy is again constrained by the Complex Head Accessibility Domain, giving rise to realizations of the root not specified for comparative contexts 26–27.

The data from the shared irregular comparative and superlative therefore support an SRA for the liten\(\sim \)små alternation over a DRA.

3.2 Shared idiosyncrasy in interpretation

As is well-known, idiomatic or idiosyncratic interpretations are licensed within specific syntactic contexts (e.g., Harley 2014a). For example, in English, go bananas has an idiomatic interpretation meaning ‘become insane’ (Choi and Harley 2019). As Choi and Harley point out, while go takes an irregular past tense form went, its morphological irregularity has no impact on the idiomatic interpretation of the phrase in the past tense went bananas. This follows from an SRA-type account that takes the realizations of go and went (or perhaps wen-) to correspond to the same abstract syntactic element (e.g., \(\sqrt{{\textsc {go}}}\)), with the idiomatic interpretation licensed in the context of this element. Shared idiosyncratic meaning is not readily derived by a DRA-type account that takes go and went to correspond to different abstract syntactic objects. (See Choi and Harley 2019 for further discussion in the context of verbal suppletion in Korean and Harley 2015 for discussion of verbal suppletion in Hiaki.)

We may now ask whether liten and små covary in idiosyncratic interpretations as predicted by an SRA but not a DRA. There exist combinations of liten and a noun where liten bears an idiosyncratic interpretation, as in 28. That its interpretation is idiosyncratic and requires a particular syntactic context is supported by two facts: i) the noun can be further modified by stor ‘big’ without contradiction, and ii) the reverse order of stor and liten yields a distinct interpretation 29.

The expectation of an SRA is that an idiosyncratic expression with liten should retain the morphological alternation, both in weak and plural contexts. This is borne out 30-31.Footnote 12

It is standard to assume that idiosyncratic interpretations are lexically specific. Thus a DRA fails to capture that liten\(\sim \)små alternate in this type of environment, with the idiosyncratic interpretation preserved across contexts.

3.3 Equative Degree Constructions

Consider an equative degree construction like that of 32 (see Anderson and Morzycki 2015 for references and a recent analysis of such constructions in various languages):

Roughly, 32 expresses that there is some degree on a scale of oldness that both individuals picked out by du and min bror have. Crucially for present purposes, the property of interest is picked out by the adjective for both individuals.

This construction can distinguish between an SRA and a DRA when there is number mismatch between the subject and the equated nominal. An SRA predicts that equative constructions with number mismatch should be felicitous, because the same scale should be picked out regardless of whether the adjective is realized as liten or små. In contrast, a DRA predicts that, because the lexical semantics of the two forms are distinguished, equatives with number mismatch should be ill-formed, as the property should only hold felicitously of one nominal but not the other. The predictions of the SRA are borne out: mismatch is possible in both directions 33–34.

3.4 nP and Predicate Ellipsis

It is known that ellipsis imposes identity conditions between the antecedent and the ellipsis site. Minimally, these conditions are semantic (see Merchant 2001 and much subsequent work). As a consequence, ellipsis can distinguish between an SRA and a DRA (cf. Bobaljik 2015a; Harley 2015; Choi and Harley 2019): given a context of number mismatch between an antecedent and an ellipsis site, an SRA predicts ellipsis to be licensed in both directions when the suppletive root is contained within the ellipsis site, as semantic identity conditions can be satisfied irrespective of number. In contrast, a DRA predicts that ellipsis should fail to be licensed, as the elided root should be semantically incompatible in the mismatched number context.

As in many languages, Swedish allows nP ellipsis under numerals. nP ellipsis in number mismatch with (focused) numerals is well-formed, as in 35–36.

As predicted by an SRA, ellipsis is licit with number mismatch between the antecedent and the ellipsis site with liten and små in both directions 37–38.Footnote 13

Relatedly, disjunction of just the numerals meaning ‘one’ and ‘two’ is possible; the numeral disjunction is followed by a plural-marked noun (and plural-agreeing attributive modifiers). små is also grammatical here, despite the number mismatch between the disjunct numerals:

The evidence from nP ellipsis therefore favors an SRA, as a DRA instead predicts that liten should be semantically incompatible with an elided plural noun, and/or that små should be incompatible with an elided singular noun.

The same logic extends to cases of predicate ellipsis. Our consultants report that, while marked, number mismatch between subjects is possible 40)–41. Number mismatch with predicate ellipsis is licensed in both directions for liten and små 42–43, as expected under an SRA.

3.5 Contradiction

As is well-known, the conjunction of a proposition P with its negation \(\lnot \)P yields a contradiction. An SRA and a DRA give rise to different predictions with respect to a contradiction test: for an expression with two conjuncts, one with positive liten and one with negative små (and vice versa) holding of the same set of individuals, the expectation for the SRA is that this should always be contradictory, as this should always be a case of P and \(\lnot \)P. However, this should not necessarily be the case for the DRA, given that the adjectives should have different meanings, giving rise to a possibility of P and \(\lnot \)Q. Such mismatch can be constructed with the use of quantifiers that require singular or plural nouns. Evidence like 44–45 then speaks in favor of the SRA over the DRA, as contradiction is unavoidable.

There is an important caveat here having to do with two confounds, namely synonymy and polysemy. A point of comparison with English little and small illustrates the issues: given that the two are synonyms in English, a contradiction test that switches out one for the other would seem to suggest that the two are suppletive:

Being synonyms rather than suppletive alternants of the same root, small and little do not overlap entirely in meaning. For example, little has the possible interpretation of ‘young’, which for many speakers is not an interpretation of small. Thus it is possible to formulate a non-contradictory sentence such as I am little but I am not small. The SRA for liten\(\sim \)små then predicts that there are no non-contradictory sentences of this type, since the meanings of liten and små are identical. As far as we can tell, this is true, thereby supporting the SRA.Footnote 14

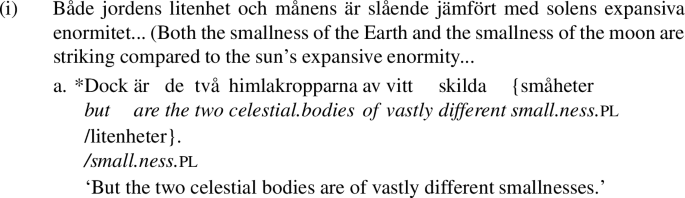

3.6 Nominalization

The nominalizing suffix -het applies to bases that appear adjectivally, such as djärv \(\sim \)djärvhet ‘bold\(\sim \)boldness, svag\(\sim \)svaghet ‘weak\(\sim \)weakness’, and klar\(\sim \)klarhet ‘clear \(\sim \)clarity’. In addition to forms with only one overt morpheme, -het can also suffix to elements with overt adjectivizing heads, such as arbets-lös-het ‘unemployment’, genomför-bar-het ‘feasibility’, and värd-ig-het ‘dignity’. We assume the form -het realizes a head n that combines either directly with property-denoting roots or with adjectival heads to produce abstract nouns.

Following Ritter (1991), Kramer (2016) and others, we assume Num is a head above nP, which we take to Lower onto n (in the sense of Embick and Noyer 2001). Swedish realizes plural number on nouns with various suffixes, such as -or, -ar, -er, -n, -s, and -\(\varnothing \) (Holmes and Hinchliffe 2020, 33–38), which we take to be overt realizations of Num. The relevance of Num is that, given that the conditions for insertion of liten and små are dependent on number features, we make predictions about the alternation in nominal environments. A -het nominalization for \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) is indeed possible, producing a quality nominal liten-het (see Arche et al. 2021 and references therein on the classification of ‘deadjectival’ nominalizations). We take one possible structure to be as in 47 (after Num has been Lowered to n).

Given our current assumptions about locality for contextual allomorphy, the realization of the root in 47 is predicted by an SRA to be liten rather than små, as the nominal feature on Num is singular and local to the root. This is borne out; as an abstract quality noun, the form of the noun is litenhet:Footnote 15

It is the number features combining with the quality noun that matter for realization. Thus a nominal argument of litenhet has no effect on the realization of the root; it is liten, even when the argument is plural.

The data in 48–49 may be unexpected under a DRA, because the semantic difference between singular and plural predication should manifest itself here, contrary to fact.

Because we are assuming -het either combines with property roots or with adjectival heads, a question arises concerning the status of 50.

In principle, nothing rules out the structure in 50, though if the interpretation is the same as in 47, this structure may be dispreferred on the basis of economy considerations. If the structure is generable, then the prediction of an SRA is that the form should be realized as småhet, the reason being that the singular feature on Num is not local to the root, being separated by two cyclic nodes a and n. The root should therefore be insensitive to the number features on Num for allomorphic purposes.

Corpus data from Språkbanken (Borin et al. 2012, accessed 2020) indicate that småhet is indeed attested, albeit in far fewer numbers than litenhet. This is what is expected if both 47 and 50 are generable, with the structurally simpler option being preferred. A search for litenhet and småhet, and their corresponding definite forms yielded the following number of hits in the singular (Table 4).

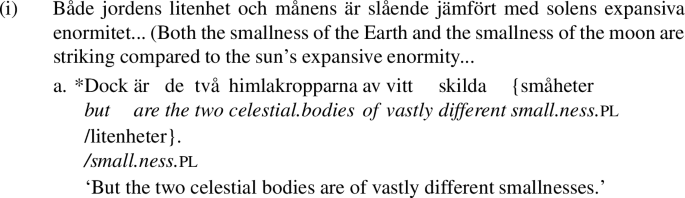

What are the expectations for plural nominalizations? Before getting into greater detail about interpretation, there is a ‘straightforward’ prediction: both structures in 47 and 50 with plural features on Num lead to the prediction under an SRA that the realization of the root should be små rather than liten: in the former case, the local feature on Num is [-sg], and in the latter case, the feature on Num is nonlocal; thus in both cases, the default form små should surface. There are few attestations of plural forms from the corpus search (performed at the same time), but the data are by and large in line with what is predicted (Table 5).

A likely cause of the low attestation of the plural is that, because litenhet is an abstract quality noun, it does not readily pluralize (see Arche et al. 2021 and references therein). This also makes it difficult to ask consultants whether the plural should be realized as litenheter or småheter.Footnote 16

However, it is possible for some speakers to interpret a -het nominalization as referring to entities that possess the quality of smallness (see relatedly Arche and Marín 2015, 264–265 and Fábregas 2016, 218), which can pluralize (cf. the relationship between beauty and beauties in English, where the latter only bears the entity reading).

The predictions of an SRA are dependent on the details of how such cases are analyzed. For present purposes, we follow the intuition that the entity interpretation is structurally derived from the corresponding quality nominal (see, e.g., Fábregas 2016, 219), and is therefore more complex. We take the relevant structure to involve denominal nominalization of the type in 51.

Under the cyclic constraint on locality, the root in 51 could not be conditioned by features on Num across two cyclic n nodes. Thus if 51 is on the right track, the prediction of an SRA is that the realization of \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) will be that of the default små. This prediction is consistent with the attested use where the noun essentially means ‘small thing(s)’; a plural is provided from an online example in https://norrlandsoperan.se/ 52; one consultant accepts this example and reports that the corresponding singular småhet is also felicitous under the relevant interpretation. (The other consultants disallow this use of litenhet/småhet altogether.)

To summarize, the ‘basic’ data support an SRA over a DRA. Furthermore, with motivated assumptions concerning nominal structure and locality conditions on contextual allomorphy, the more complex conditions are consistent with a default realization of små. Having established the superiority of the SRA over the DRA, we now proceed to address potential challenges to the account.

4 Potential challenges to the SRA

We have seen that the evidence favors an analysis of the liten\(\sim \)små alternation as contextual allomorphy. Before addressing potential challenges to the account, some clarification is in order regarding the SRA’s predictions.

In DM, exponents can be underspecified for the context of their insertion, with the least specified exponent often being referred to as the elsewhere item (or the ‘default’). The Vocabulary Items given above in 12 are repeated in 53.

53 treats liten as a special realization that surfaces only in the context of the singular, while små is inserted elsewhere. As mentioned in Sect. 2, this ordering between items reflects how specification is claimed to work in the inflection system more broadly, where the singular form is more specific 54, repeated from 7.

However, an alternative competition is also conceivable, given certain assumptions about feature representation. It could instead be hypothesized that små is a special case inserted only in plural environments, with liten being the default:

As discussed in Sect. 2, the choice of SRA makes differing predictions for which exponent (an elsewhere item) is inserted in the absence of local number features.

It is not always appreciated that contextual allomorphy accounts of root suppletion also make predictions for the realization of neighboring morphemes (see discussion in Adamson 2019b). If the formal alternations of (strong) inflection are conditioned in part by number, and the liten/små alternation is conditioned by number, we expect certain pairings of \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) and inflectional exponents but not others.

With this in mind, the choice of 53 over 55 is favored presently for at least two reasons. First, this relation would parallel the inflectional exponents, which are analyzed in 7 to have the singular forms be the more specific ones. Second, while there are heterogenous distributions for both liten and små (to be described later in this section), the current account captures the asymmetry in ‘clashing’ forms: as we investigate below, the form små-tt is attested in some environments–-with the plural form of the root and the singular form of the inflection—while litna—the singular form of the root and the plural (or weak) form of the inflection—is not. The analysis in 53 captures this asymmetry if små-tt appears when the relation between the root and the inflectional marker is nonlocal (if, for example, cyclic structure intervenes), triggering the elsewhere insertion of små. This possibility for the reverse state of affairs in 55 could incorrectly derive the form litna, which never appears.

We now proceed to address several issues for the SRA. We argue that an SRA can be maintained if the structures in question are analyzed appropriately. We tackle each issue in turn, starting with adverbial predicates 4.1, followed by the Q-adjective lite 4.2, semantic agreement 4.3, and compounding 4.4.

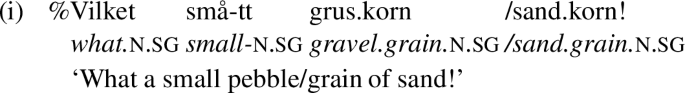

4.1 Adverbial smått

Börjars and Vincent (2011) point to a striking pattern in which an apparently neuter singular form smått surfaces, with the ‘plural’ form of the adjective (små) seemingly being used with singular neuter inflection (-t). The example that Börjars and Vincent (2011) give is in Norwegian, but the same holds for Swedish 56.

Börjars and Vincent, (2011, 256) suggest that this usage involves a resultative adjective. However, as they point out, this would be inconsistent with the agreement facts for genuine resultative adjectives, which agree with an argument in gender and number 57.Footnote 17

56 is in fact not a resultative adjective. Rather, it is best characterized as a pseudo-resultative predicate or (the related category of) resultative adverb, in the sense of Levinson (2010, 2014). While true resultative adjectives are predicated of a syntactically present nominal argument, pseudo-resultatives are instead predicated of a created entity denoted by the verb. This contrast becomes apparent when looking at the entailments for the English case in 58.

Levinson (2010, 147) demonstrates for Norwegian that resultative predicates exhibit agreement with a nominal while pseudo-resultatives do not. The same contrast is also present in Swedish, as in 59–60.

Even identifying smått as something other than a resultative adjective, it is still not immediately clear why it should appear with små rather than liten, given that the inflectional ending resembles the neuter singular. We take this use of smått to be an adverb, and offer one possibility for its derivation.Footnote 18

Adverbs in Swedish are often identical in form to the neuter singular form of adjectives, though this is not universally the case. For example, some adjectives bearing the adjectivizing suffix -lig can take -en to form a corresponding adverb, as in verklig ‘actual’\(\sim \)verkligen ‘actually’ (see Holmes and Hinchliffe 2020,127–128). Taking this relation to be one of allomorphy at a head Adv, we assume adverbs are built directly from roots or from adjectives, as in 61.

For the identity between the neuter singular and the Adv head, we suggest that the synchronic grammar treats this relation as accidental homophony; the realization -t is only one among several for adverbial heads, as mentioned above.Footnote 19 Adverbs in Swedish do not agree; thus no number features are nearby to condition the allomorphy of \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\), and consequently, the default små surfaces.Footnote 20 (Observe that an SRA with liten as the default would derive the wrong result.)

The account predicts that the form smått should appear in other adverbial environments. Indeed, adverbial smått can modify adjectives, as in 62.

Note, however, that the Q-adjective lite ‘a little’ can also be used in various adverbial environments; we turn now to the issue of lite.

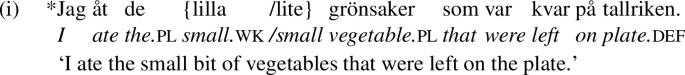

4.2 lite

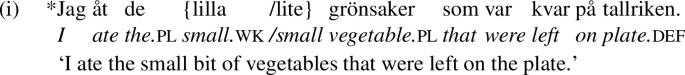

There is a form lite (with a high-register equivalent litet) used to mean ‘a small amount/number’. It does not vary according to gender or number of the head noun, as evident from 63.Footnote 21

Lite is also used adverbially to modify other adjectives (e.g., lite kallt ‘a little cold’), as well as with comparatives (e.g., lite äldre ‘a little older’). This supports its status as what is sometimes called an adjective of quantity or Q-adjective (see e.g., Solt 2015 and references therein). That lite is lexically related to liten is supported by the fact that, like liten, it is realized as lilla in weak environments 64–65.Footnote 22

We take lite to modify an unpronounced noun meaning ‘amount’ (see Kayne 2005 on the null AMOUNT analysis in English with Q-Adjectives). The null noun AMOUNT is singular and of neuter gender, which captures the fact that even plural nouns occur with the singular form lite—as with grönsaker in 63. It also accounts for the formal variant of the form being litet, with the common-gender form liten not occurring with the relevant intepretation.Footnote 23

Lastly, the AMOUNT analysis correctly captures that the null noun, like other nouns, can take a prepositional complement in a partitive construction 66. When definite, the determiner in the partitive appears in the neuter singular form, agreeing with the null AMOUNT 67.

Before proceeding, we would like to clarify one potential issue with this analysis, which we believe ceases to be an issue when properly understood. Observe that the gender agreement on the determiners in 64–65 is with the overt noun rather than with the neuter gender of AMOUNT. For comparison, consider the pseudopartitive expression in 68, where the first noun provides a unit of measurement while the second noun provides the measured substance. In such constructions, agreement (e.g., with the determiner) tracks the first noun and not the second (on Danish pseudopartitives, which follow a comparable pattern, see Hankamer and Mikkelsen 2008).

Is it expected that null AMOUNT should pattern together with kopp and other nouns found in pseudopartitive constructions for the purposes of agreement? If so, the divergence in behavior between 64–65 on the one hand and 68 on the other is surprising.

We contend, however, that we do not expect this, because the structures for the two types of expressions are distinct. On the basis of various types of evidence from definiteness marking and other properties, Hankamer and Mikkelsen (2008) argue for an analysis of Danish ‘direct’ pseudopartitives in which the unit noun is a functional n that takes a nominal phrase complement; see 69 below. (The properties they describe for Danish pseudopartitives also appear to extend to Swedish.)

This structure crucially differs from the one for Q-Adjectives, which have been taken to occur within specifiers, e.g., within a QP internal to the DP (Solt 2015). This has consequences for agreement: Norris (2014, 2017a, 2017b) points out that specifiers in the nominal domain (e.g., possessors) are routinely ignored for purposes of nominal agreement, and establishes this as a crucial prediction of his system of nominal concord, which does not percolate nominal features from specifiers (see Norris 2014,135–136). Thus agreement (e.g., on the determiner) will reflect agreement with the features of the head noun rather than with AMOUNT. In contrast, the pseudopartitive involves complementation, and is thus expected to behave differently, with agreement targeting the topmost projection with the relevant features (the higher n with the gender features associated with kopp). This difference is shown in the (simplified) structures in 69 vs. 70, which reflect how gender features are percolated within the nominal domain.

It is thus suggested here that the null AMOUNT analysis is not inconsistent with the gender agreement data, as the Q-adjective phrase is expected to be ignored for the purposes of nominal agreement. A full analysis of Q-adjectives and nominal agreement would go beyond the scope of the current article; the crucial point here is that an SRA can succeed at capturing the use of lite when situated within an articulated theory of nominal structure.

4.3 Semantic Agreement and Inflectional ‘Clash’

In some languages, it is possible to get ‘semantic’ number agreement, where the formal features of a subject are distinguished from the semantic features used for agreement, as in the British English example in 71, where demonstrative agreement with a collective noun is singular, but verbal agreement is plural (e.g., Smith 2015, 2017, 2021; among others).

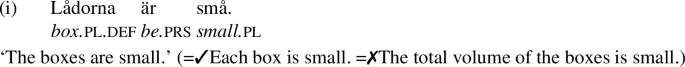

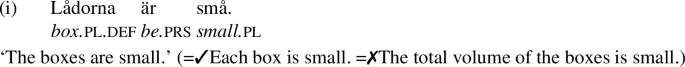

It is not possible to get this type of semantic agreement on adjectival predicates in Swedish when the subject is a singular collective noun 72: inflection on the adjective obligatorily matches the singular feature of the subject, and cannot be plural. Relatedly, it is impossible to get semantic singular agreement with subjects that are pluralia tantum 73. This indicates that predicative agreement is formal and not semantic with both collective and pluralia tantum nouns.

Under an SRA, it is in principle possible for either formal or semantic number to condition suppletion, assuming both types of number features can be present at the point of Vocabulary Insertion. As an example of the latter, Harley (2015,7–8) points out that Hiaki suppletive verbs, which are argued to be derived via contextual allomorphy on independent grounds, alternate for both collective and pluralia tantum nouns according to semantic rather than formal number.

What does an SRA predict if formal number conditions the alternation? The inflectional features of the adjective must be matched with formal and not semantic features 72)–73, and the same features condition the alternation of the root. Thus singular collective subjects should take singular liten while pluralia tantum subjects should take plural små, in line with what we observe:Footnote 24

Under this formal SRA, the inflectional marking on the adjective should covary predictably with the choice of the root. In particular, we should not expect to find plural inflection with liten (litna) or singular inflection with små (e.g., små-tt).

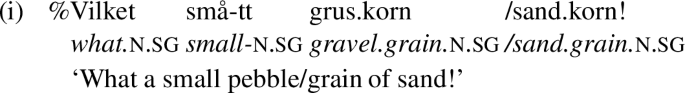

However, there is evidence that could challenge the strictly formal SRA. In particular, Börjars and Vincent (2011, 256) report that små appears in the neuter singular in contemporary Swedish, albeit less productively than earlier stages of the language. They offer the example in 76, which they describe as ‘distributive’ in meaning. Our consultants confirm that this is possible, and in fact report that litet sounds semantically strange in this context.Footnote 25 (Our consultants all remark that they would never use smått in these adjectival contexts, and that it sounds marginal at best.) The same holds for a predicative context 77.

One possibility raised by 76–77 is that smått can surface with mass nouns that have individuable subparts, where each subpart is small.Footnote 26 While our consultants reject smått with ‘object mass nouns’ (or ‘fake mass nouns’) like bagage ‘baggage’, they do however accept it with what are sometimes called ‘granular’ mass nouns, e.g., the noun tegel ‘brick’ 78. (See Sutton and Filip 2021 and references therein for extensive discussion of the semantics of object and granular mass nouns.)

In order for an SRA to rule in data like 78, it should countenance the realization of formal (neuter) singular features alongside the realization små. One option would be to allow both semantic and formal agreement with granular nouns like grus, which could be copied to adjectives through agreement (on semantic agreement, see Smith 2015, 2017, 2021; Wurmbrand 2016, 2017; Adamson and Anagnostopoulou, to appear among others). In this type of account, the formal feature [+sg] would be referenced for the exponence of the inflection, while the semantic feature [-sg] would be referenced for the exponence of the root (leading to the default exponence små in the absence of the singular feature).

An alternative proposal is instead inspired by Arregi and Nevins’s (2014,323–324) analysis of badder, a comparative form of bad in English that appears instead of the suppletive form worse when bad has a distinct interpretation. As Arregi and Nevins discuss, bad and corresponding comparative and superlative badd-er and badd-est can be used in an evaluative, complimentary sense. They propose that bad can appear in the comparative structure in 79, yielding the suppletive form worse, but can also appear in in the comparative structure in 80 with an eval head, corresponding to the evaluative sense (structures from Arregi and Nevins 2014,322–323). (They connect eval to what is observed in Romance languages with diminutivizing suffixes applying to adjectives.) In this case, the environment blocks the suppletive conditioning, such that the realization is badd-er rather than worse.

We suggest that the realization of smått in the above examples constitutes a parallel pattern of blocking between the root \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) and the inflectional affix, leading to the default realization of små. In this case, the intervening morpheme is a distributive head distr\(_{GR}\) (GR for ‘granular’), which is required for interpreting the meaning of ‘small’ with respect to the individual subparts of the aggregate for granular mass nouns. (We note that under our current assumptions, we are forced to say that distr\(_{GR}\) is cyclic, so that aInfl is not visible for the purposes of allomorphy at the node \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\).)

This analysis derives the facts, though a proper evaluation would necessitate a greater understanding of the semantics and morphosyntax of granular mass nouns, a topic well beyond the scope of the current work. Before proceeding, we note that this grammatical option appears to be extremely restricted: only the strong neuter singular form smått is felicitous. Strikingly, the weak environment in 82 renders all variants of små ungrammatical; aggregate nouns of common gender cannot occur with (variants of) små, either 83. The analysis does not readily capture this defectivity, and we leave this issue to future research.Footnote 27

To conclude this subsection, we have observed that an SRA is compatible with basic facts of agreement with collective and pluralia tantum nouns, but must be supplemented with auxiliary assumptions to account for marginally acceptable examples of smått. While the peripheral use of adjectival smått raises a host of theoretically pertinent questions, we contend that it does not undermine the general account of the liten\(\sim \)små alternation offered by an SRA. Instead, it reflects how a peripheral option of the grammar can manifest as a marginal option for a speaker.

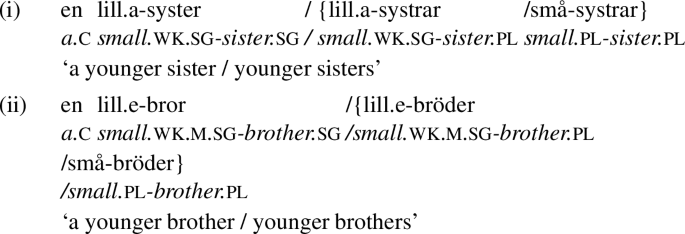

4.4 Compounding

We now turn to the issue of compounds with \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\), where the alternation is more complex, this time between the forms lill and små. The modest goal is to demonstrate how an SRA is consistent with the data from compounds, given reasonable auxiliary assumptions about compound formation.

We first situate our predictions within the context of compound structure. Following Harðarson 2017; Embick and Shwayder 2018 and other work, we take primary compounds to be derived via head adjunction. Thus an adjective-adjective compound with \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) in the ‘modifier’ position would be formed as in 84, following node-sprouting of the inflectional morpheme, as described in Sect. 2.

Under our current assumptions, because categorizing heads are cyclic, they prevent a root’s allomorphy from being sensitive to the context at or above a second categorizing head. This means that number features on aInfl should not be visible to the root \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) in 84, and consequently, \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) should always be realized with the elsewhere form små. (See however Harðarson 2021 for extensive discussion of compounding and allomorphy in DM; this work comes to distinct conclusions about cyclicity in compounds.)

This is borne out for adjective-adjective compounds, which are fairly productive, e.g., små-ro.lig ‘small-funny’—meaning ‘a little funny’ (*lillrolig) and små-snygg ‘small-good.looking’—meaning ‘a little good-looking’. A corpus search using Språkbanken (Borin et al. 2012) in 2021 lends support to this claim:Footnote 28 of the approximately 2200 (type) hits for adjective compounds with the initial part being either lill or små, fewer than 50 use lill, and closer inspection reveals many of these to be mistagged (such as lille, an inflected form of the adjective; or lill-syster, which is a variant of a noun meaning ‘younger sister’ discussed below). (An important exception, which is more frequent—with more than 100 tokens in the corpus—we postpone discussion of, as it fits in with the analysis below.)

The expectation that små is the correct form in compounds also carries over to adjective-verb combinations, which indeed allow the first member of the compound to be små fairly productively, e.g., små-regna ‘rain a little’, and små-le ‘smile a little’, and små-röka ‘smoke a little’. A corpus search again confirms that lill is virtually unattested in such compounds, with fewer than 25 type hits for lill of the over 1600 verb types that begin either with lill or små.

All else being equal, the predictions for adjective-noun compounds would be the same with respect to the form of \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\). However, nominal compounds turn out to exhibit some variation with respect to \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\)’s realization, as discussed by Börjars and Vincent (2011) and Bondarenko (2019). Broadly, three main options are attested: i) små for both singular and plural 85; ii) lill for both singular and plural 86; and iii) a form of lill in the singular and either lill or små in the plural (often with one being preferred) 87.Footnote 29 Despite this variation, there appear to be no cases where lill is only used in the plural or små is only used in the singular.Footnote 30

Recent corpus-based work by Alice Bondarenko (2019) has shed light on the distribution of lill and små within compounds. While Bondarenko frames her analysis within a lexical-semantic approach to the alternation, along the lines we have been arguing against, we contend that the SRA can be maintained, and offer a structural approach instead. To capture the relevant generalizations, we propose three distinct structural options, which derive the observed patterns and have some principled motivations. There may be alternatives to consider; the present objective is simply to establish that an SRA is capable of handling the compounding data.

In what we take to be the ‘default’ case, compounds formed with \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\), such as (85), involve the combination of \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) first with an adjectivizing head a, as in (88). Like the adjective-adjective and adjective-verb compounds, the number features on Num are not accessible to the root because of the two cyclic heads that separate the two. The realization of \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) uses the elsewhere item små, regardless of whether the compound is singular or plural.

That små is a default option is consistent with the generalization that lill seems only to be licensed under special circumstances, which can be characterized as ‘diminutive’. For example, Bondarenko reports that when lill or små appears in a compound that refers to a child, there is often an affectionate sense with lill but a neutral or pejorative sense with små, as in lill.tjej ‘little girl’ vs. små.tjej ‘little girl’. The form lill is also reportedly used for pets and small body parts belonging to children, such as lill.katten ‘the little cat’ and lill.handen ‘the little hand’. Perhaps most strikingly, Bondarenko (2019,19–20) points to a contrast where a compound with små refers to an object, e.g., små-kaka ‘small cake’, while the corresponding lill form can be used endearingly to refer to a child: lill-kaka ‘small cake’ (a contrast confirmed by consultants). These generalizations support a diminutive analysis of the use of lill.

Even with this generalization about the diminutive, the SRA does not straightforwardly generate the correct form, and thus requires refinement. For concreteness, we propose that \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) can exceptionally combine with a head a [dim].Footnote 31 This use of a [dim] is largely confined to compounding, as in 89.

Realization as lill in the structure in 89 comes from a revision to the Vocabulary Items from 12. The exponent liten is inserted in the context of [dim] as well, a feature which also obligatorily triggers the morphophonological change to lill (triggered also by [wk]).

Realization is expected to be insensitive to number in these compounds: i) the [dim] feature on a is more local than number features that combine with the nominal compound; and ii) two cyclic heads a and n separate \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) from Num.

There is in fact independent support for a [dim] with \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\). As shown in 11, an adjectival modifier in weak plural environments takes the form små; however, it is also marginally acceptable to use lilla, but only if the meaning is affectionate 91. This indicates that a [dim] can also be found outside of non-compounding contexts.

Another point of support comes from a different kind of compound. Under the current account, it should be possible to have [\(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) a [dim]] in other combinations apart from an adjective-noun compound, with a realization of lill instead of små. In fact, as alluded to above, while adjective-adjective compounds virtually always use små, an important exception is lill-gammal ‘small-old’, which translates roughly to ‘precocious’. That this is a description used for children is in line with the a [dim] account. (The plural is correctly expected to be lillgamla, not smågamla.)Footnote 32

We leave the condition on insertion of liten in 90 as disjunctive: it is inserted in the context of either [+sg] or [dim]. It is worth noting, however, that diminutive morphemes are known cross-linguistically to have an individuating function (Jurafsky 1996). Thus a relation between diminutivization and number features may in fact underlie what looks like two distinct contexts, though we do not attempt a full unification presently.

Taking stock, the structure in 88 yields uniform realization as små in the singular and the plural, and the structure in 89 yields uniform realization as lill in the singular and the plural. How then would the third option be derived, where lill appears in the singular and either form is acceptable in the plural?

We propose to derive this pattern (in part) from a third structure, where there is no adjectivizing head at all in the ‘compound’, with \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) adjoining directly to n—this treats \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) more like a lexical prefix rather than a compounding element. In this environment, Num is sufficiently local to \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\), as only one cyclic head intervenes. Thus \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\)’s realization is dependent on the value of number, being realized as lill in the singular and as små in the plural.

What happens to the interpretation of \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) in this environment? We adopt the view from Gouskova and Bobaljik (2022) that the interpretation of a root without a categorizing head should be relatively ‘bleached’, as categorizing heads play a role in determining root interpretation in Distributed Morphology (Marantz 2013; Arad 2003). Gouskova and Bobaljik show how this distinction manifests for diminutive onok in Russian, which they argue has a contentful ‘baby animal’ interpretation with a categorizing head, but an expressive/evaluative interpretation without one, giving rise to differences in how these two environments for onok interact for purposes of suppletion, gender, and declension class.

We suggest that \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) in 92 is similarly ‘bleached’, allowing only a diminutive interpretation which we tentatively associate with age, and not with size or other properties. This reflects the generalization that nouns with singular lill that allow små in the plural tend to be kinship nouns (see Bondarenko 2019), where \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) provides information about relative age.Footnote 33 This makes the prefix use similar in function to \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) when combined with a [dim], except that we would suggest that the latter specifically has a more contentful diminutive interpretation associated with children (and correspondingly with diminutive size).

The structure in 92 accounts for the realization of lill in the singular and små in the plural, though it does not output lill in the plural. Our suggestion is that, with some kinship roots, speakers may have a choice between the structures in 89 and 92 (with interpretive effects). As discussed above, 89 yields lill in the plural. This speaks more generally to variation with head nouns in compounds: given the structures in 88, 89, and 92, we expect that some head nouns will be compatible with multiple structures, yielding distinct possibilities for realization of \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) with the same noun. We believe this to be a positive aspect of our account, since multiple forms of \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) are indeed attested with the same head noun (Bondarenko 2019). The account is nevertheless restrictive in pointing to specific interpretive consequences for each structure.

To conclude this subsection, compounding with \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) yields different forms, which exhibit a complex distributional pattern that is nevertheless constrained. Maintaining an SRA, several structural options for compounding were shown to result in different realizations, with the main components of the account being: i) små as the default realization of \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\); ii) a diminutive a that conditions the insertion of lill; and iii) three options for compound formation with nominal heads.

5 Suppletion and Locality

We have argued that the alternation liten\(\sim \)små is best treated as contextual allomorphy conditioned by number features. In this section, we reflect on how this suppletive pattern fits into the theory of both root suppletion and contextual allomorphy. We first address domain and adjacency issues, and then proceed to make other related points.

5.1 Suppletion and complex heads

First and arguably foremost, the SRA presented here has the form of the root covary with number features internal to the same complex head (or MWd). However, an alternative ‘configurational’ analysis is conceivable, according to which suppletion is not sensitive to number as an agreement feature, but rather, is sensitive to the features on the subject of predication. For example, assuming the subject is generated internal to an adjectival phrase (in line with the Predicate-Internal Subject Hypothesis), an allomorphic relation could obtain where the root is sensitive to the features of the subject in a structure like 93:

The two types of accounts can be distinguished from each other in Swedish in that they make different predictions for deadjectival environments. Though adjectival agreement morphology is absent in nominalizations, it is often assumed that subjects of adjectival predication are base-generated internal to adjectival projections in deadjectival nominals (e.g., Alexiadou and Iordǎchioaia 2014; Iordăchioaia 2014). For deadjectival nominalizations, we therefore have a situation in which the two accounts are distinguished: a configurational analysis predicts covariation in form by number of a still-present argument, while the agreement morphology analysis predicts formal invariance with respect to the number of the argument. The prediction of the latter theory is borne out 94, repeating 48–49.

Why is this relevant for the theory of allomorphic locality? The current account conforms with the expectations under the Complex Head Accessibility Domain condition; the ‘configurational’ account is in fact incompatible with it. The reason is that agreement produces a ‘word’-internal set of \(\phi \) features to which a root cannot otherwise be sensitive. This gives rise to a more general prediction for root suppletion across languages—one which we cannot verify here:

If correct, this means that agreement is a necessary condition for \(\phi \) suppletion on adjectives and verbs. This generalization has been challenged by Bobaljik and Harley (2017) on the basis of verbal suppletion in Hiaki. They argue that Hiaki verbal suppletion can be conditioned by the features of a DP complement, rather than being mediated through, e.g., an agreement relation between a verb and its object. However, Thornton (2019) criticizes this view, offering an alternative account that appeals to ‘verbal number’ agreement, a property that manifests itself as reduplication in Hiaki and other languages. As Thornton (2019) suggests, under her analysis, the Hiaki data conform to a prediction like 95; it may be that other alleged counterexamples can similarly be reinterpreted. See also Toosarvandani (2016) for an account of number-based suppletion in Northern Paiute, whose alternations do not conform to the complement-only expectation, as well as Oseki (2016) on Ainu.

5.1.1 Relativized Adjacency

As discussed in Sect. 3.1, mindre and minst are used respectively for the comparative and superlative forms of \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\), rather than a form related to liten or små 96. Because the conditioning number features are harbored on aInfl, which appears exterior to the cmpr/sprl node 97, the pattern supports the idea that a more local conditioning factor is favored over a less local factor, along similar lines to what is reified by Choi and Harley (2019) as their ‘Local Allomorph Selection Theorem’.

5.1.2 Other aspects of locality

We now briefly address various other points, whose interpretation are contingent on the correctness of our proposed structural analyses.

The first point concerns the nominalization litenhet, discussed in Sect. 3.6. This alternation as it is presently analyzed requires number features on Num to condition the realization of the root past an overt, intervening head n (-het). If this is on the right track, then linear adjacency cannot be a strict condition on contextual allomorphy, pace Embick (2010), but in line with Smith et al. (2018). Relatedly, given that -het also seems to be irrelevant to the conditioning of the alternation, the analysis also speaks against the Span Adjacency Hypothesis from Merchant (2015).

Second, the cyclic status of the lexical heads a and n are supported, in light of the relationship between derived structures and default realization of \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\).

Third, a portmanteau-based theory of suppletion is not readily supported (considering, e.g., Siddiqi’s 2009 account of fusional exponence in DM, or much of the work in Nanosyntax). Given the decomposition in the singular (for liten-\(\varnothing \) and lite-t), the portmanteau analysis would treat små as being \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) combined with a plural node. Several aspects of the analysis could be correspondingly altered; however, this type of account is not readily compatible with the adverbial use of smått (discussed in Sect. 4.1), and it would require additional stipulations for the nominalizations for litenhet and småheter described in Sect. 3.6.

Lastly, the Swedish pattern is notable in allowing a feature to condition the alternation independently of category (as with the nominalization facts). This is distinct from English plural examples like goose/geese and foot/feet, where the corresponding verbs fail to alternate in the plural, for example, in They foot/*feet the bill every time (a similar observation is made by Preminger 2020). It remains a puzzle what should govern the category-(in)dependence of suppletion (and/or irregular morphophonology), though one speculation would be to attribute it to the choice between agreeing features (e.g., those on aInfl) versus base-generated features (e.g., those on Num). Perhaps learners allow implication only in one direction, such that conditioning by an agreement feature implies conditioning by the base-generated counterpart, though not the other way around. This would correctly rule out the English case while ruling in the Swedish one.

6 Conclusion

This work provided arguments in favor of treating the liten\(\sim \)små alternation in Swedish as reducible to contextual allomorphy and not to lexical-semantic differences between distinct roots, with evidence from irregular morphology, interpretive idiosyncrasies, equative constructions, ellipsis, contradiction, and nominalization. The analysis did not embrace the common characterization of the alternation, according to which liten (along with its variant lill) is the singular form while små is the plural. We proposed instead that liten appears in singular contexts (when number features are local), while små is an elsewhere or ‘default’ form, and we suggested this fits the general pattern of adjectival inflection in the language.

We showed that, with an appropriate understanding of locality conditions on allomorphy and with articulated structural accounts of relevant phenomena, this analysis can derive more challenging facts about the distribution of the alternants, including in cases that appear to be difficult for an allomorphy approach. This was shown in the finer-grained discussion of nominalization, as well as for adverbs, ‘Q-adjectives’, modification of granular mass nouns, and various types of compounding. Future work exploring putative instances of suppletion may find utility both in this study’s battery of diagnostics distinguishing between allomorphy vs. semantic differentiation, as well as in the arguments made for how a suppletive pattern can extend to more complex settings.

The findings are consistent with an approach to locality that restricts the conditioning of allomorphy within a complex head, privileges more local features over less local features, and is cyclic. That being said, locality conditions on allomorphy continue to be a matter of debate, as do the structural particulars for several kinds of expressions, including nominalizations and compounds. We contend that the arguments that favor the contextual allomorphy approach over the lexical-semantic one are also applicable under alternative theories. The analyses of the more challenging data, however, while well-motivated (we believe), arguably have more fragile components to them, and changes to our understanding either of locality conditions or of these structures may have implications for the account of the suppletive alternation. What is presented here is hopefully an account whose explicitness lends itself to necessary critique and evaluation in this respect.

An amendment was made to the allomorphy analysis in Sect. 4, which suggested that a variant of liten also appears in diminutive contexts. This captured otherwise unexpected patterns in nominal compounds (and related cases), though it did so at the cost of adding a disjunctive condition to the Vocabulary Item for liten, with both [+sg] and [dim] yielding the insertion of liten rather than små. Disjunctive conditions for Vocabulary Items are not often sanctioned in DM, though it was suggested in Sect. 4 that these two separate contexts may in fact be conflated into a single one if more properly understood, given that diminutives often have individuating or singulativizing functions cross-linguistically. The details of this conflation, however, remain to be worked out for the Swedish alternation.

This study is somewhat unique in that it focuses on root suppletion conditioned by an agreement feature of an adjective. This contrasts with recent DM work on root suppletion, which has tended either to examine verbs, nouns, or pronouns (e.g., Moskal 2015b; Smith et al. 2018; Thornton 2019) or to examine adjective alternations conditioned in non-agreement-related environments, namely in comparatives and superlatives (Bobaljik 2012). It has been suggested that adjectival root suppletion conditioned by number in fact belongs to a less common, exceptional type of suppletion involving ‘contextual’ rather than ‘inherent’ categories (Hippisley et al. 2004,395–398). This roughly corresponds to what syntacticians may consider, respectively, ‘valued by agreement or long-distance dependency’ vs. ‘part of the same extended projection’. By looking at number features on adjectives, this work offers a detailed case study of one such exceptional ‘contextual’ pattern. Examining lesser-studied patterns of this sort is, and continues to be, important in our pursuit to understand how root suppletion manifests itself in natural language.

Notes

In addition to standard abbreviations from the Leipzig Glossing Rules, the following abbreviations are used: c = ‘common gender’; str = ‘strong’; wk = ‘weak’.

There is also a ‘masculine’ singular -e ending in the written variety (and in some spoken varieties) that appears in weak environments, as in den lill-e mann.en ‘the.c.sg small.sg.weak-m.sg man.def’—see Holmes and Hinchliffe 2020,53,59. We set masculine forms to the side for present purposes.

That the suffix is distinct from the base is evidenced by the ‘masculine’ −e ending in the written variety (and in some spoken varieties), as in den lill-e mann.en ‘the.c.sg small.sg.weak-m.sg man.def’ (on which, see Holmes and Hinchliffe 2020,53). It is also evident from the appearance of lill without the suffix, as in some compounds, e.g., lill.finger ‘little finger’. See Sect. 4.4 for more on compounds.

All of our consultants report that the weak form lilla is at least marginally acceptable in the definite plural context of (11), but only if it has a diminutive (or affectionate) interpretation. All consultants reject lilla in the predicative and strong environments of (8) and 9. See discussion of diminutive interpretations of \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) in compounding and in 11 in Sect. 4.

Note that other analyses of the inflectional exponence may actually run into issues from the liten\(\sim \)små alternation. For example, if the impoverishment rule in 6 were to be replaced with a rule that instead deleted number features, then the correct inflectional forms would still surface given the vocabulary in 7, but (given certain assumptions about the timing of impoverishment) this would wrongly predict små to come out across all weak contexts.

It is somewhat unclear what it would mean for små to have an inherently plural lexical semantics. Observe that, like small in English, små is a distributive predicate over individuals—it is in fact a ‘stubbornly’ distributive predicate in Schwarzschild’s (2011) sense, meaning it does not allow cumulative interpretation of plurals, as evident from i. This suggests that små semantically characterizes singular individuals rather than pluralities. This may cast further doubt on the hypothesis that liten and små are semantically distinguished along the lines sketched in 14.

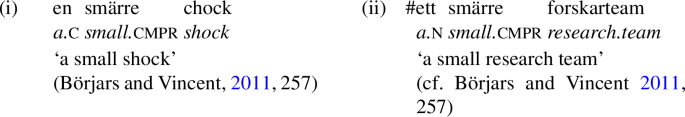

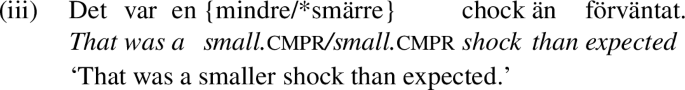

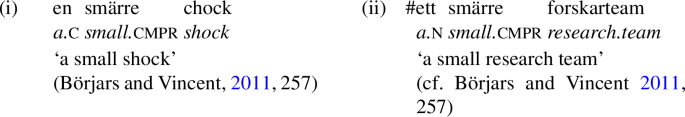

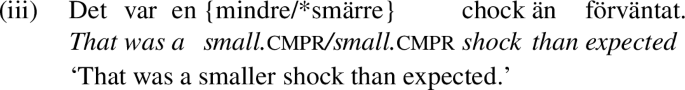

Börjars and Vincent, (2011,257) observe that a comparative form smärre still exists in Swedish. Our consultants corroborate the data from this work in i, though they note that the ‘size’ interpretation is not available for them ii.

According to Börjars and Vincent , smärre is not a genuine comparative, but is instead a synonym of liten. We agree, and further support this view with the data in iii, which indicate that it is ungrammatical to have smärre appear with a comparative complement. Interestingly, however, smärre cannot be put into a comparative, either: speakers accept neither a synthetic form smärrare nor a periphrastic expression mer smärre.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out the relevance of the latter type of evidence.

A similarly idiosyncratic context involves technical names for musical intervals. In English, a minor third corresponds to three half-steps while a major third corresponds to four. In Swedish, en liten ters literally means ‘a small third’ and refers to a minor third, while en stor ters literally means ‘a big third’ and refers to a major third. Other musical intervals can also be formed in combination with either liten or stor. Strong and weak forms with liten/lilla/små are all attested with various intervals (e.g., thirds, sevenths, etc.) at https://www.musikipedia.se/ackord, accessed 2022. As expected, the weak and plural forms of \(\sqrt{{\textsc {small}}}\) retain these meanings.

Setting aside ellipsis, the alternation between liten\(\sim \)sma is unexpected under a DRA if Ionin and Matushansky (2018) are correct that numerals always combine with semantically singular nouns, with plural marking being due to agreement. This would reinforce the formal (as opposed to semantic) status of the number conditioning (though see Sect. 4.3).

Note, however, that non-contradiction can arise in principle with a root that has multiple meanings. It is possible in English to say I am little, but I am not little to mean ‘I am young but not small in stature’. Such examples are fairly forced, requiring special prosody to clarify what is intended.

One speaker allows småhet as well, but likes neither nominalization. See further discussion of småhet below.

A plural ‘measure’ reading corresponding to the quality nominalization, which has been observed to be possible for some nominals in other languages (cf. Fábregas 2016,218), is not accepted for litenhet i, though we note that the preference seems to be for a form that includes små, as expected by the current account.

Note that the adverbial reading with mjukt in 57 has a grammatical but absurd interpretation in which the cooking of the potato is carried out in a soft manner.

Levinson (2010) distinguishes between pseudo-resultatives and resultative adverbs (on which, see Geuder 2000), pointing to the adjectival status of the former in various languages. Given the availability of adverbs for pseudo-resultative-like interpretations in English (as in tightly braided), we find the adverbial analysis of the Swedish examples plausible, and do not dwell on the distinction here.

The morphophonological variation for adverbs is parallel to what is observed for neuter singular adjectives. This is in some sense comparable to the morphophonological changes of the English -s for verbs, possessives, and plurals, which are typically not considered to realize the same morpheme.