Abstract

As described by others, an extracellular calcium-sensitive non-selective cation channel ([Ca2+]o-sensitive NSCC) of central neurons opens when extracellular calcium level decreases. An other non-selective current is activated by rising intracellular calcium ([Ca2+] i ). The [Ca2+]o-sensitive NSCC is not dependent on voltage and while it is permeable by monovalent cations, it is blocked by divalent cations. We tested the hypothesis that activation of this channel can promote seizures and spreading depression (SD). We used a computer model of a neuron surrounded by interstitial space and enveloped in a glia-endothelial “buffer” system. Na+, K+, Ca2+ and Cl− concentrations, ion fluxes and osmotically driven volume changes were computed. Conventional ion channels and the NSCC were incorporated in the neuron membrane. Activation of NSCC conductance caused the appearance of paroxysmal afterdischarges (ADs) at parameter settings that did not produce AD in the absence of NSCC. The duration of the AD depended on the amplitude of the NSCC. Similarly, NSCC also enabled the generation of SD. We conclude that NSCC can contribute to the generation of epileptiform events and to spreading depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A TTX resistant non-selective cation current (NSCC) that is activated by low [Ca2+]o was first described by Hablitz et al. (1986) in chick dorsal root ganglion cells. Hablitz et al. (1986) suggested that a similar current in central neurons could play a role in the generation of seizures and spreading depression (SD). MacDonald, Xiong, and collaborators (Chu et al. 2003; Xiong and MacDonald 1999; Xiong et al. 1997) detected in mammalian central neurons an NSCC that is activated by the lowering of [Ca2+]o. This channel is maximally open when extracellular calcium concentration is zero, and at the normal [Ca2+]o of 1.2–1.5 mM it permits the flow of a small current which, presumably, adds to the resting conductance of the cell. This channel is not voltage dependent and it is about equally permeable to Na+ and K+ but not to Ca2+ or other divalent and multivalent ions. It is, however, blocked not only by Ca2+ but also by other divalent cations (Xiong et al. 1997). With view of the depolarization caused by the activation of the [Ca2+]o-sensitive NSCC, Xiong et al. (1997) also suggested that it could contribute to the generation of epileptiform seizures.

Swandulla and Lux (1985) discovered a non-selective cation channel in snail neurons that is activated by elevated intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+] i ). A [Ca2+] i dependent NSCC (often denoted ICAN) has also been recorded in hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Caeser et al. 1993; Crepel et al. 1994) and substantia nigra inhibitory neurons (Lee and Tepper 2007). The TRPM4b channel, which is expressed in mammalian neurons, has been characterized as a [Ca2+] i -activated, Ca2+-impermeable, monovalent cation-permeable channel (Fleig and Penner 2004; Launay et al. 2002). Since uptake of Ca2+ into neurons results simultaneously in an increase in [Ca2+] i and a decrease in [Ca2+]o, if the two Ca2+ sensitive currents co-exist in the same cell, they are expected to reinforce one another and in fact could perhaps be generated by the same channel (see Section 3).

It has been known for a considerable time that low [Ca2+]o can induce seizure-like spontaneous discharges in intact brain (Sabbatani 1901) as well as in brain tissue slices (Jefferys and Haas 1982; Konnerth et al. 1986). Besides, at the onset of seizures, no matter how induced, [Ca2+]o drops precipitously (Heinemann et al. 1977, 1978; Pumain et al. 1983, 1985). Taken together, these two sets of observations suggest that the drop in [Ca2+]o, as also the increase in [K+]o, may be a link in one of the parallel feedback loops that can promote epileptic seizure discharges. The induction of spontaneous burst discharges by low [Ca2+]o has usually been attributed to reduced screening of neuron membrane surface charges leading to enhancement of voltage dependent inward Na+ current and hence reduced firing threshold (Hille 2001). Discovery of the [Ca2+]o-dependent NSCC adds another mechanism by which depletion of extracellular Ca2+ can promote neuron excitation even more powerfully.

In a study of the ion currents that are responsible for hypoxic spreading depression-like depolarization (HSD) in hippocampal tissue slices Müller and Somjen (2000) found that blockade of voltage gated Na+ as well as glutamate-controlled channels by a mixture of TTX, CPP and DNQX, while it postponed HSD, it did not usually prevent it. Adding Ni2+ to the blocking cocktail did, however, reliably suppress HSD (Müller and Somjen 1998). This lead to the conclusion that HSD is generated by the cooperation of several inward currents, one of which could be a non-specific cation current (NSCC) that is insensitive to TTX but is blocked by Ni2+ (Müller and Somjen 1998, 2000). This as yet unidentified current could be the [Ca2+]o sensitive current, which is indeed inhibited by divalent cations.

Earlier we have simulated seizure-like and SD-like processes (Kager et al. 2000, 2002, 2007; Somjen et al. 2008) in a neuron model based on the NEURON simulation environment of Hines, Moore and Carnevale (Hines and Carnevale 1997). It appeared that SD and HSD could be simulated in the presence of either a persistent Na+ current (INa,P) or one that resembled NMDA-controlled current (INMDA). When both were activated, SD occurred sooner and lasted longer than with either alone (Kager et al. 2002). Importantly, both simulated AD and SD required a substantial increase in [K+]o, illustrating pathological positive feedback where shifts in ion concentration influence the very channels through which the ions flowed in the first place (review in Somjen 2004).

We now report computer simulations that demonstrate that, similarly to altered [K+]o/[K+] i ratio, low [Ca2+]o can also promote seizure-like firing and SD-like depolarization due to activation of [Ca2+]o -sensitive NSCC. Some of the data appeared in abstract form (Somjen et al. 2004). A companion paper (Somjen et al. 2008) examines neuron-glia interaction mediated by ion flux.

1 Experimental procedures

The morphology of the computer model used here is similar to the one described in Kager et al. (2000, 2002, 2007) as the “simplified” cell, and it is illustrated in Kager et al. (2007).

The model was created in the simulation environment “Neuron” of Hines and Carnevale (1997). A neuron and a glia-endothelial buffer space were aligned in parallel and communicated with each other through a limited interstitial space (IS). The neuron consisted of a soma with unbranched basal and apical dendrites attached to the opposite ends. The electrical currents were carried by the appropriate ions according to the Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz current equations (Hille 2001) and the ions accumulated in the relevant compartments. Diffusion between compartments was also implemented and charge was conserved and electroneutrality maintained in all compartments. The ions taken into account were Na+, K+, Ca2+, Cl− and A−, the latter representing non-permeating anions in the neuron and in the glia cytosol. Ionic pumps were implemented that exchanged 3 Na+ for 2 K+, that exchanged 3 Na+ for 1 Ca2+ and ones that extruded Ca2+, all under the assumption of unlimited energy. (See Kager et al. 2000, 2002, 2007 and Somjen et al. 2008 for details).

The neuron contained regions that consisted of a heterogeneous mix of active conductances: the soma, the active dendrite segments and the passive dendrite segments. There is considerable experimental evidence for unequal distribution of ion channels between neuron soma and dendrites and also along dendritic shafts and their branches (e.g. Karst et al. 1993; Magee et al. 1998; Schiller et al. 1997; Williams and Stuart 2003). The simplified morphology used in this study does not reproduce that of a real neuron, but its functioning approximates that of hippocampal pyramidal neurons (e.g. Herreras 1990; Turner 1984; Wadman et al. 1992). The basal dendrite and segments 0, 4 and 5 of the apical dendrite were implemented as passive dendrite segments; the active dendrite segments were apical 1, 2 and 3 (counting from nearest to farthest from the soma; see Fig. 1 in Kager et al. 2007). The soma membrane contained the classical fast sodium channel (generating the transient Na+ current, INa,T) necessary for action potential firing. It also contained channels for the A-type potassium current (IK,A). Both soma and the active dendrites contained the delayed rectifier potassium current (IK,DR), transient low-voltage activated (LVA) calcium currents (ICa,T) and non-inactivating high voltage-activated (HVA) calcium currents(ICa,L). Persistent sodium current (INa,P) was incorporated in both the soma and active dendrite segments, while NMDA-receptor mediated current (INMDA) only in the active dendrite segments. Activation of the INMDA is a joint function of [K+]o and membrane potential. High [K+]o causes an increase in extrasynaptic glutamate concentration which activates NMDA receptors (Crowder et al. 1987). The voltage dependence of NMDA receptors is mediated by modulation of the Mg2+ block of the channel (Hille 2001). The properties of the simulated INMDA were earlier described in detail (Kager et al. 2000). Intracellular calcium [Ca2+] i was buffered by a first order instantaneous calcium buffer assuming uniform [Ca2+] i within each sub-segment. [Ca2+] i controlled the calcium dependent inactivation of ICa,L, and the activation of a calcium-dependent potassium current IK,SK. All equations that govern these currents have been given in detail in Kager et al. (2000, 2002, 2007).

Characteristics of the simulated calcium sensitive non-specific cation current. (a): Calcium dependence of the conductance. Solid line: Hill coefficient of 3.4; dashed line: Hill coefficient of 1.4. Half-maximum activation (EC50) for both settings was 0.39 mM. (b): Time course of the current in response to a sudden decrease of extracellular calcium concentration. Note slower onset than turn-off of the current. The ordinate scale in (b) is arbitrary because the time course does not change with the magnitude of the current

Linear leak currents of Na+, and K+ plus a small NSCC (see below) and the pump currents controlled the resting potential of around −70 mV. Resting calcium concentration was set by adjusting the calcium extrusion mechanisms to reach a stable resting value around 55 nM at −70 mV.

The glial membrane contained leak conductances and pump currents (corresponding to the “passive” glia as defined in Somjen et al. (2008) but no Ca2+ conductance. Calcium was not represented in the glial cytosol. The leak potassium conductance was much more dominating than the one of the neuron membrane, yielding a resting membrane potential in the glial cell of −88 mV (for details see Kager et al. 2007, Somjen et al. 2008).

The invariant Cl− conductance in both neuron and glial compartments allowed maintenance of ion balance during unequal redistribution of cations and of osmotic pressure with associated volume changes. To avoid excessive complication of the model we did not include a Cl− pump. This is justified because GABA induced or voltage dependent Cl− currents were not represented. The resting Cl− concentration gradient was in equilibrium at resting membrane potential. Impermeant anion (A−) concentrations were chosen to balance the intracellular electrical charges. Changes in ionic strengths were translated into “virtual” osmotic pressure and resulted in volume changes of the relevant compartments with resulting concentration changes, according to the set of equations described in detail in Kager et al. (2002).

The main expansion of our model compared to its previous versions was the implementation of the Ca-sensitive nonselective cation conductance, gNSCC, (based on data given in Chu et al. 2003; Xiong et al. 1997 and Xiong, personal communication). The nonspecific cation channel senses the extracellular calcium concentration (Fig. 1(a)) and changes its conductance gNSCC for the monovalent cations K+ and Na+.

The dependence of the conductance of the NSCC on [Ca2+]o was computed by:

where g max is the maximum conductance attainable in the absence of Ca2+ and the Hill factor h determines the steepness of the relation. Figure 1(a) gives two examples of this relation that were implemented and investigated. In both cases EC50 is equal to 0.39 mM (Xiong et al. 1997). In the steeper version of the curve the Hill factor is 3.4, which gives the current at a resting [Ca2+]o (1.5 mM) and resting Vm a realistic value of around 1% of its maximum. With a Hill factor of 1.4, the resting value was 13.2%. In cultured cells Xiong et al. (1997) found the Hill factor to be near 1. Most of the illustrations presented in this paper were performed with the Hill factor of 3.4, in order to keep resting conductance realistically low but, as shown in Fig. 4, qualitatively equivalent responses have been obtained with the less steep version of the current-concentration relation (see also the Section 3).

We assumed gNSCC to be independent of voltage (Xiong et al. 1997) and gave it equal permeability for Na+ and K+. We implemented the Ca2+ gating as a fourth order gating process which yielded an empirical opening time constant of around 166 ms and a closing time constant of 25 ms (Fig. 1(b)). These time constants were independent of current magnitude. The NSCC contributed to the resting conductance of the neuron. Whenever the conductance of the NSCC was altered, the leak conductances had to be slightly adjusted to maintain the balance of the total (net) membrane current and hence keep Vm steady at rest. The code for a representative selection of simulations presented in this paper will be added to the NEURON data base.

2 Results

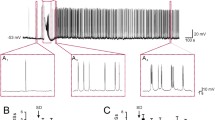

Figure 2 shows two simulations, differing only in the presence or absence of the [Ca2+]o-sensitive non-specific cation current (NSCC). For Fig. 2(a) the maximal conductance of the NSCC was set at zero. The cell was stimulated by depolarizing current of 0.8 s injected into the soma. The cell fired action potentials only as long as the stimulation continued. For Fig. 2(b) the maximal conductance of the NSCC was set at 0.0065 S/cm2, and the same stimulus now triggered a self-sustaining afterdischarge (AD; note that the maximal conductance of the NSCC is never attained, because it is reached only at zero [Ca2+]o; see Fig. 1). Smaller NSCC settings resulted in shorter AD duration (Fig. 4). At very low settings the NSCC enhanced firing frequency without inducing AD.

The [Ca2+]o-dependent non-specific cation current (NSCC) facilitates paroxysmal afterdischarge (AD). (a): in the absence of NSCC, stimulation by a depolarizing current injected into the neuron soma evoked regular firing. (b): with the NSCC channel enabled, the same stimulus caused higher frequency firing and it triggered prolonged afterdischarge (AD). Note the different time scales for A and B

Details of the NSCC-assisted AD are illustrated in Fig. 3. Figure 3(a–c) show action potentials on expanded timescales from selected segments of the simulation of Fig. 2(b). Figure 3(a) represents the start of stimulation and the onset of firing; Fig. 3(b) the end of stimulation and the beginning of the AD, while in Fig. 3(c) the AD is seen to subside. In Fig. 3 (a and b) each spike is followed by a brief hyperpolarizing afterpotential (AHP) and then by gradual depolarization resembling a pacemaker potential. At the end of the AD, however, the last pacemaker potential fails to trigger an action potential and the AD is terminated (Fig. 3(c)). Interstitial Ca2+ levels are shown in Fig. 3(d–f). [Ca2+]o decreased to its lowest level at the end of stimulation and the beginning of the AD (Fig. 3(e)).

Details of the response seen in Fig. 2(b). (a–c): Action potentials fired by the neuron during three phases of the response shown on an expanded time scale. (d–f): [Ca2+]o levels near the soma and the second dendritic segment during the times corresponding to (a–c). (g–i): the currents of the neuron soma generating the responses of (a–c). I K,DR: delayed rectifier K+ current; I K,SK: Calcium-dependent SK-type K+ current; I Na,T: transient (Hodgkin-Huxley type) Na+ current; I Ca,T: transient, low threshold Ca2+ current; I NSCC: The [Ca2+]o-sensitive non-specific cation current

The role of the currents generating the voltage response of Fig. 2(b) are plotted in Fig 3 (g–i). As [Ca2+]o decreased in the interstitial space around the soma (Fig. 3(d,e)), the NSCC was turned on (Fig. 3(g,h)). During each action potential the NSCC showed brief positive spikes. Since the non-specific current is generated by the opposing simultaneous fluxes of Na+ and K+, the reversal potential of the NSCC is slightly negative relative to zero, (similalrly to EPSCs), and therefore during the positive overshoot of the action potentials the NSCC briefly reversed from inward to outward. In between spikes, the NSCC provided a sustained inward current. While the amplitude of the NSCC was small compared to the large surges of the transient Na+ current, INa,T, the NSCC provided just enough depolarization between action potentials to enable re-activation of the INa,T and hence the continuation of the AD (Fig. 3(h)). The cooperative action of the INSCC and the INa,T generated the pacemaker potentials that kept the firing going. It should be noted that stronger stimuli could trigger AD even in the absence of the NSCC, assisted in that case by INa,P (see Kager et al. 2007), but the presence of the NSCC lowered the threshold for AD considerably. The AD was self-limiting (Fig. 3(i)) because as EK subsided (Fig. 2(b)), the neuron began to repolarize, while at the same time [Ca2+]o rose toward its rest level (Fig. 3(i)) de-activating the NSCC, and these two shifts prevented re-activation of INa,T. EK began to recover as the ratio [K+]o/[K+] i was being restored by the combined actions of the neuron 3Na/2K pump and the glial buffer (see also Somjen et al. 2008).

The simulations presented so far were performed with the Hill coefficient set to 3.4, making the Ca2+ dependence of the NSCC rather steep (see Section 1, Fig. 1 and Section 3). We also used the less steep setting, with the coefficient at 1.4. In this case a relatively intense NSCC current was flowing in the un-stimulated neuron, necessitating adjustment of resting leak conductances and the ion pump in order to keep resting potential and ion concentrations in a steady state (see Section 1). Apart from these adjustments, the qualitative behavior of the model was similar to that seen with the steeper Ca2+ dependence. For the two examples of Fig. 4 the Hill coefficient was 1.4 and the maximal conductances were 0.000125 S/cm2 for a and 0.001 for b. This illustrates the dependence of AD duration on NSCC intensity. We also explored higher values of the maximal g NSCC with the Hill coefficient 1.4. Raising the conductance of the NSCC induced spontaneous firing, and at even higher gNSCC the model generated spontaneous spreading depression (not illustrated).

Afterdischarge generated with the Hill coefficient of the NSCC lowered to 1.4, at two different stimulus intensities. (see Fig. 1). (a): maximum conductance of g NSCC = 0.000125; (b): gNSCC = 0.001. All other parameters equal in (a) and (b)

The [Ca2+]o-sensitive NSCC can also become the main current responsible for SD-like depolarization (Fig. 5). Voltages and currents recorded in the second dendritic segment are shown in Fig. 5(a and b). The dendrite responses were chosen for Fig. 5 because in hippocampal pyramidal neurons the apical dendrites are the primary generators of the currents involved in SD (see Section 3 and Herreras and Somjen 1993). For the simulation of Fig. 5 the stimulus was 0.9 nA for 750 ms, and the maximal conductance of the NSCC channel was set at 0.005 S/cm2. As shown in Fig. 5(b), by far the largest dendritic inward current was carried by the NSCC, but the INMDA, even though it was smaller, was activated slightly earlier and it contributed to the ignition of SD. The inward flux of Ca2+ was at first mainly mediated by INMDA, but then INMDA faded as V m and [K+]o, which jointly controlled INMDA, began to recover. Meanwhile the 3Na/Ca exchanger (NaCaX) reversed to the “Ca-entry mode” due to the depolarization of V m and the decline of E Na, and it insured the continuing influx of Ca2+ into the neuron (Fig. 5(b); see also Blaustein and Lederer 1999 and Section 1 in Kager et al. 2007). Importantly, when the NSCC was turned off but other conductances were not changed, the same stimulus did not trigger SD but the cell generated prolonged AD instead (not illustrated). SD was ignited when the net (aggregate) dendritic current (I mem) turned inward (Fig. 5(b)). In our earlier simulations, in the absence of INSCC, the activation of INMDA and INa,P could cause the dendritic current to turn inward and ignite SD (Kager et al. 2002).

Simulated spreading depression (SD) mediated by the calcium sensitive non specific cation current. (a): Voltages in the second dendritic segment. V m: membrane potential; E Na: equilibrium potential of Na+; E K: equilibrium potential of K+; E Ca: equilibrium potential of Ca2+; E Cl: equilibrium potential of Cl−; Stim.: timing of the depolarizing stimulating current. (b): The main membrane ion currents in the 2nd dendritic segment. INaCaX: the calcium current carried by the 3Na/Ca exchanger; IK,DR: delayed rectifier K+ current; IK,SK: SK-type calcium dependent K+ current; ICa,T: T-type Ca2+ current; INMDA: the net current (I Na + I K) controlled by the NMDA receptor; INSCC: the net current (I Na + I K) carried by the Ca-sensitive non specific cation conductance; Im: the net (aggregate) membrane current. Note that, except during the early part of the SD response, Ca2+ flows inward through the NaCaX exchanger

We also simulated cerebral hypoxia. In order to explore whether INSCC by itself is capable of supporting hypoxic SD-like depolarization (HSD) we imitated the actions of TTX and glutamate antagonists (cf. experiments by Müller and Somjen 1998, 2000) by setting the conductances of I Na,T, I Na,P and I NMDA to zero. To simulate severe hypoxia, the 3Na+/2K+ pump of the neuron and the glial cell as well as the Ca pump of the neuron were turned off; similarly to our earlier study of HSD (Kager et al. 2002). In this condition SD-like depolarization was generated without applying a depolarizing current stimulus, provided that g NSCC was present (not illustrated). In a subsequent simulation, I NSCC was also eliminated, imitating a condition in which all major Na+ currents were blocked, and now turning off the pump simulating the “hypoxic” condition did not induce SD. Instead, the cell depolarized slowly due to the gradual increase of the [K+]o/[K+] i ratio while the dendritic membrane current (I mem) remained weakly outward, carried mainly by I K,DR and I K,SK. (not illustrated). This behavior is similar to that seen in hippocampal tissue slices after oxygen deprivation in the presence of TTX, glutamate receptor antagonists plus Ni2+ (Müller and Somjen 1998).

3 Discussion

The simulations presented here demonstrate that a [Ca2+]o-sensitive NSCC can facilitate the generation of seizures as well as spreading depression (SD) and, together with those in previous reports (Kager et al. 2000, 2002, 2007; Somjen et al. 2008), they confirm that either high [K+]o or low [Ca2+]o can support either paroxysmal discharge or SD, depending on the state of the various membrane ion channels. In the epileptic brain seizures are probably initiated by un-inhibited synaptic excitation but, once triggered, both high [K+]o and low [Ca2+]o appear to cooperate in maintaining the seizure (Fig. 6 and review by Somjen 2004). We found conditions where just turning on the NSCC was sufficient to generate seizure-like AD. Similarly, simulated SD-like depolarization was ignited with the help of the inward current carried in large part by the NSCC, with parameter settings under which turning off the NSCC prevented SD or, sometimes, converted it into AD. Seizures and SD are different conditions but, in common, both are self-limiting all-or-none events that require positive feedback. The dominant sustained inward current responsible for the generation of paroxysmal AD flows near the site of action potential generation and, in the case of pyramidal neurons, this is mainly in the cell soma (Somjen et al. 1985; Wadman et al. 1992 and review in Somjen 2004). By contrast, experimental data has shown that during SD dendritic currents lead ahead of somatic currents, at least in neocortical and hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Herreras and Somjen 1993; Ochs 1962; Wadman et al. 1992,) The simulations presented in this report and earlier ones confirm this finding (Kager et al. 2000, 2002, and Somjen et al. 2008).

Simplified conceptual representation of the parallel positive feedback loops that promote seizure discharges and SD. Depolarization of the neuronal membrane causes the firing of action potentials, which elevate extracellular potassium concentration and lower extracellular calcium concentration. High [K+]o reinforces depolarization; it also enhances persistent Na+ current (I Na,P), which also adds to the depolarization. At the same time calcium channels are activated which lower [Ca2+]o and raise [Ca2+] i (not shown here), activating non-specific cation current(s) (INSCC). Low [Ca2+]o thus reinforces neuron firing which in turn augments the lowering of [Ca2+]o. The mechanisms that prevent a runaway vicious circle and keep healthy brain tissue normally functioning could not be fitted in the diagram

The feedback loops operating in these pathological conditions are schematically shown in Fig. 6. With view of the inherent potential for runaway excitation one can ask, as Jung and Tönnies (1950) have, how it is that all of us do not convulse every time we get out of bed. The processes that normally preserve the well controlled operation of cerebral tissue and those that upset its stability in diseased brains fall outside the present study.

The screening of negative surface charges by Ca2+ (see Hille 2001) was not represented in the model. When [Ca2+]o decreases, removal of the screen has the same effect as a decrease in the membrane potential and hence it augments the excitability of neurons and adds to the epileptogenic effect. Incorporating surface screening in a computer model requires an other, major investigation. Other variables remaining equal, decrease in [Ca2+]o would also diminish all inward Ca2+ currents. When, as in our simulations, the decrease in [Ca2+]o is the consequence of influx of Ca2+ into neurons, the accompanying increase in [Ca2+] i is expected to influence a number of calcium dependent processes. For our discussion the most important is the seemingly distinct NSCC that appears to be activated in hippocampal neurons, not by low [Ca2+]o, but by high [Ca2+] i (Swandulla and Lux 1985; Caeser et al. 1993; Crepel et al. 1994; Lee and Tepper 2007). Removing Ca2+ from the bathing fluid depresses the [Ca2+] i -sensitive NSCC, presumably because less Ca2+ is available to flow into cells and raise [Ca2+] i , whereas low [Ca2+]o enhances the [Ca2+]o-sensitive current. In intact brain, however, during high frequency firing or SD, whenever Ca2+ flows into cells [Ca2+] i increases at the same time as [Ca2+]o decreases and, apparently, both signals activate a current carried by monovalent cations. It is an open question whether they flow through two different channels or through the same one. Our simulations of the NSCC did not take into account the effect of the changes in [Ca2+] i .Had we incorporated the added effect of [Ca2+] i , it would presumably have changed only the scaling of gNSCC.

Besides AD, the NSCC also facilitated the ignition of simulated SD and hypoxic SD-like depolarization. HSD was induced even when the transient and persistent Na+ currents (I Na,T and I Na,P) as well as the NMDA-controlled current were turned off. Eliminating these major inward currents imitated the administration of TTX, CPP and DNQX to brain tissue slices. In this condition withdrawing O2 from hippocampal slices induced HSD of greatly delayed onset indicating the operation of an unidentified TTX insensitive and glutamate-independent current. Adding Ni2+ to the “blocking cocktail” did prevent HSD (Müller and Somjen 1998, 2000). The simulations supports the idea that the Ni2+-sensitive “missing” current could be the Ca2+ sensitive NSCC.

According to Xiong et al. (1997) the Ca2+ dependence of the NSCC can be described by a function with Hill coefficient close to unity. This value was derived from data recorded in neurons cultured from the brains of newborn rats. When we tested the model using 1.4 for this parameter, we found that at the resting potential of −70 mV a rather large NSCC was flowing. Since there is no published evidence for a large NSCC in normal adult cerebral neurons at rest, we used a larger value, 3.4, for the Hill coefficient for most of the simulations (Fig. 1). With this setting the NSCC in the un-stimulated neuron was small. Since, however, this choice was arbitrary, we also performed a number of simulations with a Hill coefficient of 1.4. The results were qualitatively similar with both settings of the Hill coefficient, but the less steep calcium-dependence resulted in greater readiness for AD generation (Fig. 4). Incidentally, the Hill coefficient of the [Ca2+] i -activated NSCC generated by TRPM4b channels was either 4 or 6 depending on the treatment of the preparation (Launay et al. 2002).

The model was, of course, simplified not just morphologically but also functionally. Some known ion currents were missing, as were the effects of pH change and of metabolic and other biochemical processes. We ignored these factors, because the questions asked were limited to a possible role of the [Ca2+]o sensing NSCC. Also absent were voltage controlled currents in the glial membrane. We did explore the effect of glial voltage gated K+ currents in a companion paper (Somjen et al. 2008). Lian and Stringer (2004) found some experimental support for extracellular calcium being regulated by astrocytes, and this also deserves further exploration.

Epileptic conditions can have many different causes, and by no means all have been discovered. It is possible that a shift in the [Ca2+] dependence, or increased conductance, or changing steepness of the activation function of either the [Ca2+]o- or the [Ca2+] i -sensitive NSCC, due either to genetic or to acquired anomaly, is one of them.

Reference

Blaustein, M. P., & Lederer, W. J. (1999). Sodium/calcium exchange: Its physiological implications. Physiological Reviews, 79, 763–854 Medline.

Caeser, M., Brown, D. A., Gähwiler, B. H., & Knöpfel, T. (1993). Characterization of a calcium-dependent current generating slow afterdepolarization of CA3 pyramidal cells in rat hiipocampal slice cultures. European Journal of Neuroscience, 5, 560–569. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00521.x.

Chu, X.-P., Zhu, X.-M., Wei, W.-L., Li, G.-H., Simon, R. P., MacDonald, J. F., et al. (2003). Acidosis decreases low Ca2+ -induced neuronal excitation by inhibiting the activity of calcium-sensing cation channels in cultured mouse hippocampal neurons. Journal of Physiology, 550, 385–399. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2003.043091.

Crepel, V., Aniksztejn, L., Ben-Ari, Y., & Hammond, C. (1994). Glutamate metabotropic receptors increase a Ca2+-activated nonspecific cationic current in CA1 hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology, 72, 1561–1569.

Crowder, J. M., Croucher, M. J., Bradford, H. F., & Collins, J. F. (1987). Excitatory amino acid receptors and depolarization-induced Ca2+ influx into hippocampal slices. Journal of Neurochemistry, 48, 1917–1924. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb05756.x.

Fleig, A., & Penner, R. (2004). The TRPM ion channel subfamily: Modelcular, biophysical and functional features. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 25, 633–639. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2004.10.004

Hablitz, J. J., Heinemann, U., & Lux, H.-D. (1986). Step reductions in extracellular Ca2+ activate a transient inward current in chick dorsal root ganglion cells. Biophysical Journal, 50, 753–757.

Heinemann, U., Lux, H. D., & Gutnick, M. J. (1977). Extracellular free calcium and potassium during paroxysmal activity in the cerebral cortex of the cat. Experimental Brain Research, 27, 237–243. doi:10.1007/BF00235500.

Heinemann, U., Lux, H. D., & Gutnick, M. J. (1978). Changes in extracellular free calcium and potassium activity in the somatosensory cortex of cats. In N. Chalazonitis, & M. Boisson (Eds.), Abnormal neuronal discharges (pp. 329–345). New York: Raven Press.

Herreras, O. (1990). Propagating dendritic action potential mediates synaptic transmission in CA1 pyramidal cells in situ. Journal of Neurophysiology, 64, 1429–1441.

Herreras, O., & Somjen, G. G. (1993). Analysis of potential shifts associated with recurrent spreading depression and prolonged unstable SD induced by microdialysis of elevated K+ in hippocampus of anesthetized rats. Brain Research, 610, 283–294. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(93)91412-L.

Hille, B. (2001). Ionic channels of excitable membranes. Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, Massachusetts.

Hines, M., & Carnevale, N. T. (1997). The NEURON simulation environment. Neural Computation, 9, 1179–1209. doi:10.1162/neco.1997.9.6.1179.

Jefferys, J. G. R., & Haas, H. L. (1982). Synchronized bursting of CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells in the absence of synaptic transmission. Nature, 300, 448–450. doi:10.1038/300448a0.

Jung, R., & Tönnies, J. F. (1950). Hirnelekrische Untersuchungen über Entstehung und Erhaltung von Krampfenladungen: die Vorgänge am Reizort und die Brensfähigkeit des Gehirns. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Zeitschrift für Neurologie, 185, 701–735. doi:10.1007/BF00935520.

Kager, H., Wadman, W. J., & Somjen, G. G. (2000). Simulated seizures and spreading depression in a neuron model incorporating interstitial space and ion concentrations. Journal of Neurophysiology, 84, 495–512.

Kager, H., Wadman, W. J., & Somjen, G. G. (2002). Conditions for the triggering of spreading depression studied with computer simulation. Journal of Neurophysiology, 88, 2700–2712. doi:10.1152/jn.00237.2002.

Kager, H., Wadman, W. J., & Somjen, G. G. (2007). Seizure-like afterdischarges simulated in a neuron model. Journal of Computational Neuroscience, 22, 105–128. doi:10.1007/s10827-006-0001-y.

Karst, H., Joëls, M., & Wadman, W. J. (1993). Low-threshold calcium current in dendrites of the adult rat hippocampus. Neuroscience Letters, 164, 154–158. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(93)90880-T.

Konnerth, A., Heinemann, U., & Yaari, Y. (1986). Nonsynaptic epileptogenesis in the mammalian hippocampus in vitro. I. Development of seizurelike activity in low extracellular calcium. Journal of Neurophysiology, 56, 409–423.

Launay, P., Fleig, A., Perraud, A.-L., Scharenberg, A. M., Penner, R., & Kinet, J.-P. (2002). TRPM4 is a Ca2+-activated nonselective cation channel mediating cell membrane depolarization. Cell, 109, 397–407. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00719-5.

Lee, C. R., & Tepper, J. M. (2007). A calcium-activated nonselective cation conductance underlies the plateau potential in rat substantia nigra. Journal of Neuroscience, 27, 6531–6541. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1678-07.2007.

Lian, X.-Y., & Stringer, J. L. (2004). Astrocytes contribute to regulation of extracellular calcium and potassium in the rat cerebral cortex during spreading depression. Brain Research, 1012, 177–184. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2004.04.011.

Magee, J. C., Hoffman, D. A., Colbert, C. M., & Johnston, D. (1998). Electrical and calcium signaling in dendrites of hippocampal neurons. Annual Review of Physiology, 60, 327–346. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.327.

Müller, M., & Somjen, G. G. (1998). Inhibition of major cationic inward currents prevents spreading depression-like hypoxic depolarization in rat hippocampal tissue slices. Brain Research, 812, 1–13. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00812-9.

Müller, M., & Somjen, G. G. (2000). Na+ dependence and the role of glutamate receptors and Na+ channels in ion fluxes during hypoxia of rat hippocampal slices. Journal of Neurophysiology, 84, 1869–1880.

Ochs, S. (1962). The nature of spreading depression in neural networks. International Review of Neurobiology, 4, 1–70. doi:10.1016/S0074-7742(08)60019-7.

Pumain, R., Kurcewicz, I., & Louvel, J. (1983). Fast extracellular calcium transients: Involvement in epileptic processes. Science, 222, 167–188. doi:10.1126/science.6623068.

Pumain, R., Menini, C., Heinemann, U., Louvel, J., & Silva-Barrat, C. (1985). Chemical transmission is not necessary for epileptic seziures to persist in the baboon Papio papio. Experimental Neurology, 89, 250–258. doi:10.1016/0014-4886(85)90280-8.

Sabbatani, L. (1901). Importanza del calcio che trovasi nella corteccia cerebrale. Rivista Sperimentale di Freniatria, 27, 946–956.

Schiller, J., Schiller, Y., Stuart, G., & Sakmann, B. (1997). Calcium action potentials restricted to distal apical dendrites of rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. Journal of Physiology, 505, 605–616. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.605ba.x.

Somjen, G. G. (2004). Ions in the brain. Normal function, seizures and stroke. Oxford University Press: New York.

Somjen, G. G., Aitken, P. G., Giacchino, J. L., & McNamara, J. O. (1985). Sustained potential shifts and paroxysmal discharges in hippocampal formation. Journal of Neurophysiology, 53, 1079–1097.

Somjen, G. G., Kager, H., & Wadman, W. J. (2004). Calcium sensitive non-selective cation current promotes seizures and spreading depression. Experimental Biology 2004, Abstract # 1320.

Somjen, G. G., Kager, H., & Wadman, W. J. (2008). Computer simulations of neuron-glia interactions mediated by ion flux. Journal of Computational Neuroscience. In press, doi:10.1007/s10827-008-0083-9.

Swandulla, D., & Lux, H.-D. (1985). Activation of a nonspecific cation conductance by intracellular Ca2+ elevation in bursting pacemaker neurons of Helix pomatia. Journal of Neurophysiology, 54, 1430–1443.

Turner, D. A. (1984). Segmental cable evaluation of somatic transients in hippocampal neurons (CA1, CA3 and dentate). Biophysical Journal, 46, 73–84.

Wadman, W. J., Juta, A. J. A., Kamphuis, W., & Somjen, G. G. (1992). Current source density of sustained potential shifts associated with electrographic seizures and with spreading depression in rat hippocampus. Brain Research, 570, 85–91. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(92)90567-S.

Williams, S. R., & Stuart, G. J. (2003). Role of denritiuc synapse location in the control of action potential output. Trends in Neurosciences, 26, 147–154. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00035-3.

Xiong, Z.-G., Lu, W.-Y., & MacDonald, J. F. (1997). Extracellular calcium sensed by a novel cation channel in hippocampal neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 94, 7012–7017. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.13.7012.

Xiong, Z. G., & MacDonald, J. F. (1999). Sensing of extracellular calcium by neurones. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, 77, 715–721. doi:10.1139/cjpp-77-9-715.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Action Editor: Alain Destexhe

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Somjen, G.G., Kager, H. & Wadman, W.J. Calcium sensitive non-selective cation current promotes seizure-like discharges and spreading depression in a model neuron. J Comput Neurosci 26, 139–147 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10827-008-0103-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10827-008-0103-9