Abstract

The purpose of the current study was to examine the contributions of coparenting quality and child routines to children’s social–emotional competence during COVID-19. Further, we investigated the indirect effects of coparenting quality on children’s social–emotional competence via child routines. The participants were 403 mothers of children between 23 and 102 months old (M = 59.23, SD = 10.92). Mothers reported their children’s social–emotional competence, coparenting quality, and children’s routines as main variables and the COVID-19 pandemic effects (financial, resources, psychological, and within-family interaction effects). Results from the structural equation model showed that higher levels of coparenting quality and consistency in child routines were positively related to children’s social–emotional competence. In addition, there was an indirect effect of coparenting on children’s social–emotional competence through child routines. In detail, higher parental coparenting quality was associated with more consistent child routines, and, in turn, more consistent child routines were associated with higher levels of social–emotional competence. These findings suggest that coparenting and child routines may play a crucial role in children’s social–emotional competence. Results are discussed, considering their functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Highlights

-

Structural equation modeling tested the indirect effect of mother-perceived coparenting on children’s social–emotional competence via child routines.

-

Quality coparenting relationship is positively related to child routines, and in turn, child routines are positively associated with better social–emotional competence.

-

Coparenting and child routines play a crucial role in the social–emotional competence of children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

One of the crucial elements for quality child development is the acquisition of social–emotional competence in early childhood, given that this period lays a foundation for children’s remainder of their life (Shonkoff et al., 2000). Social–emotional competence is an umbrella term that incorporates how children regulate and express their emotions in contextually appropriate ways to initiate and sustain relationships and engage with their social and physical environments (Yates et al., 2008). Further, children require social–emotional competence to understand what social or emotional response is necessary within a particular social context. This understanding allows children to interpret the social cues in the environment and respond to these cues accordingly (Ladd, 2005; Yates et al., 2008). Therefore, promoting and supporting these skills in the early years is essential for children’s quality development and learning.

The development of social-emotional competence is not independent of the environmental context in which the child grows. In supportive environments (e.g., home, school, or peers), children have opportunities to develop greater social–emotional competence (Saral & Acar, 2021; Ladd, 2005). Given that children begin to develop in their immediate environments, such as the dynamics within the home context, it is evident that parenting significantly influences children’s social–emotional competence (Karreman et al., 2008). However, changes in children’s immediate environment due to disasters or pandemics could also affect all developmental domains, including children’s social–emotional competence (Masten & Osofsky, 2010; Pitchik et al., 2021; Wisner et al., 2018). The current study examines the roles of coparenting quality and child routines on children’s social–emotional competence within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study will not directly examine the changes in the context of the pandemic; however, we should acknowledge that the pandemic may have brought some changes to the family dynamics (e.g., parent–child relationships or parent–parent relationships) in which children grow (Wang et al., 2020). Considering these changes in within-family dynamics, we conceptualized the examination of coparenting, child routines, and children’s social–emotional competence by taking into account the changes related to the pandemic within-family dynamics, as this could be reflected by parents’ perceptions.

The COVID-19 outbreak has quickly brought specific changes to families’ daily routines, given that many countries have closed schools and workplaces, and individuals have been recommended to self-isolate and stay home (Cluver et al., 2020; McCoy et al., 2021). As a result of these substantial changes, many parents have had to work remotely while caring for their children. With the pandemic, parents’ ability to access social support outside the home has been disrupted. This social isolation and other challenges that the current outbreak has emerged have negatively affected the physical and psychological well-being of parents and their children (Babore et al., 2020; Brooks et al., 2020; Pitchik et al., 2021). Given the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic to the psychological well-being of parents and children, the present study aimed to investigate the roles of coparenting and child routines in relation to children’s social–emotional competence during the COVID-19 outbreak. This suggests that fostering cooperative coparenting relationships and promoting consistent routines among children may aid families in navigating the adversities of the pandemic.

Theoretical Background

The current study investigated the associations among parent–parent relationships, child routines, and children’s social–emotional competence from the perspective of the Family Systems theory (Minuchin, 1974). Coparenting is one of the important components of the family systems in which parents share the responsibility for child-related tasks (Teubert & Pinquart, 2010). Coparenting relationships might affect the children’s and the parent’s subsystem, which is linked to children’s adjustment (Qian et al., 2020). According to the Family Systems theory, coparenting processes contribute to child development over and above any other subsystem (Boričević Maršanić & Kušmić, 2013; Feinberg, 2003). Therefore, coparenting quality is essential in children’s development, including social–emotional competence. For example, cooperative coparenting provides a sense of predictability, security, and stability within the family, promoting the sense of emotional security among children (Minuchin, 1974; McHale et al., 2002). On the other hand, conflictual coparenting might induce negative arousal in children, and consequently, it may disrupt children’s ability to regulate their emotions and behaviors (Boričević Maršanić & Kušmić, 2013).

Coperating is not an isolated entity influencing children’s social–emotional competence, which may also influence how within-family dynamics function, including routines within a family context (Feinberg, 2003). On that ground, we conceptualized that coparenting may manifest how child-related routines could emerge and, in turn, affect children’s social–emotional competence. Family members who spend more time together during the COVID-19 process can find opportunities to establish positive relationships with each other (Chu et al., 2021). On the other hand, the COVID-19 outbreak can be a potential environmental stressor that emerges outside the family system and may undermine parents’ functioning (Adadms et al., 2020), including coparenting. External stressors can disrupt the balance within-family dynamics (Minuchin, 1985). The COVID-19 pandemic might be a possible stressor (Brown et al., 2020), hindering a family member’s functioning and creating disruptions in family relationships. This disruption in the family dynamics may impact the functioning of all family members, thereby affecting the child’s well-being (Cox & Paley, 1997). Correspondingly, the COVID-19 pandemic might disrupt the balance of the family system, and this situation might affect the functions of the family and, in turn, child adjustment. Family Systems theory suggests an approach to understanding children’s social functioning in the family context (Watson, 2012). Overall, we framed the current study based on the Family Systems theory as a guide for explaining the findings in the COVID-19 pandemic context.

Coparenting and Social–Emotional Competence

Coparenting refers to the ways that both parents agree or disagree with each other and share the responsibility for raising their child(ren) (Feinberg, 2003). Specifically, coparenting is a multidimensional construct comprising cooperation, conflict, and triangulation dimensions. Cooperation refers to parents’ joint decisions on child-related topics, such as discipline and safety, and their support for each other. Conflict refers to disagreements between parents about their principles in raising their child(ren) and undermining the other parent’s coparenting role. Finally, triangulation is defined as the inclusion of a child in interparental conflicts, leading children to take sides and join in a parent–child coalition (Pinquart & Teubert, 2015).

The results from a meta-analysis revealed that cooperation, agreement, and conflict as aspects of coparenting were associated with children’s social functioning (Teubert & Pinquart, 2010). Such that coparental cooperation and agreement were positively, and conflict was negatively related to child social functioning. Furthermore, findings from the research have shown that children exposed to cooperative coparenting had higher emotional regulation and prosocial behavior, including sharing, helping, and empathy reflecting social–emotional competence (Qian et al., 2020; Scrimgeour et al., 2013). Considering the importance of coparenting for children’s social–emotional competence, examining the association between these two constructs during COVID-19 could reveal compelling information.

Children’s Routines and Social–Emotional Competence

Establishing organized routines in children’s daily lives might effectively promote their growth and well-being (Fiese & Everhart, 2008). Routines are repetitive activities that occur in each daily/weekly life of a child with predictable regularity and are overseen by at least one adult in the context (Sytsma et al., 2001). Typical child routines such as morning, mealtime, reading, play, and bedtime routines are structured to organize the daily life of families (Fiese & Everhart, 2008). Specifically, routines provide consistent environmental cues to children, allowing them to exhibit expected behavioral patterns throughout the day (Fiese et al., 2002; Sytsma et al., 2001). Consequently, with predictable routines, children can associate their own actions with consequences and manage their behavior accordingly, potentially leading to increased emotional and social competence (Jordan, 2003).

For example, establishing regular bedtime routines (e.g., having a bath, reading a story before sleep) or daily routines (e.g., watching TV, doing chores at home) may foster a sense of belonging to the family, children’s compliance with the instructions of their parents may contribute to the child’s social–emotional development. Empirical evidence also suggests a relationship between routines and behavior regulation, which is a key aspect of social–emotional competence (Fiese & Everhart, 2008; Bater & Jordan, 2017; Ren & Fan, 2019). In detail, engaging in daily routine activities requires children to follow a sequence of steps, understand consequences, and comply with the rules, thereby nurturing their ability to control and regulate their emotions and behaviors (Ren & Fan, 2019).

The COVID-19 pandemic might be a possible environmental stressor that may have disrupted children’s routines. In detail, children’s daily routines have considerably changed during the COVID-19 outbreak, as children lack social interactions, outdoor activities, and school participation due to home confinement (Lee, 2020; Wang et al., 2020). While some studies have indicated disruptions in children’s routines amidst the COVID-19 outbreak, little is known about the association between child routines and social–emotional competence in the COVID-19 pandemic context.

The Indirect Effect of Coparenting on Children’s Social–Emotional Competence Through Child Routines

The evidence is clear that positive parenting practices within the family context support children’s routines (Bater & Jordan, 2017; Jordan, 2003). Based on the previous research findings, it has been suggested that parents who engage in positive parenting practices may be more prone to establish predictable and consistent routines for their children (Sytsma et al., 2001; Wittig, 2005). On the other hand, parents with less adequate parenting practices may have difficulties establishing routines for their children (Zajicek-Farber et al., 2014).

Despite the research examining the role of coparenting or routines on social and emotional competence, limited studies have focused on the possible mechanism through which coparenting influences social and emotional skills. Ren et al. (2019) studied the mediating role of child routines on the association between parenting and the social–emotional skills of preschool children. They found the mediating role of routines on the relationship between authoritative parenting and social–emotional skills, such that authoritative parenting was positively associated with children with more consistent routines. They suggested that the main mechanism behind this relation might be that routines are the extension of positive parenting practices, and authoritative parents are more competent in establishing consistent routines for their children (Bater & Jordan, 2017; Ren et al., 2019). Another study investigating the link between coparenting and children’s social–emotional development found the mediating role of child routines (Ren & Xu, 2019). The researchers proposed that parents who are supportive of positive child-rearing practices may be more effective in setting daily routines. In turn, it may be related to social–emotional outcomes in children. However, more research is needed to understand the mechanism that identifies child routines as a mediator of the association between coparenting and children’s social and emotional competence. We acknowledge that testing the mediating effect in the absence of longitudinal data would be problematic (Agler & De Boeck, 2017). However, understanding the mechanisms of the indirect effect of child routine by which the association between coparenting and children’s social and emotional competence changes would provide substantial information regarding children’s social–emotional competence within the family context during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Present Study

Previous research studied the roles of the COVID-19 pandemic on parental support, daily routines, and children’s social–emotional outcomes (Barata & Acar, 2022; Brown et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2021; Uzun et al., 2021). However, no research has yet examined how coparenting would contribute to the children’s daily routines and social–emotional competence in the COVID-19 context. The current study aimed to examine the contributions of mothers’ perceptions of coparenting and child routines to children’s social–emotional competence. In addition, child routines might have also been affected by the current COVID-19 outbreak. We aimed to examine the indirect effect of coparenting on children’s social–emotional competence through child routines.

To address the purpose of the current study, first, we hypothesized that coparenting cooperation would be positively and, coparenting conflict and triangulation would be negatively associated with children’s social–emotional competence. Second, we hypothesized that coparenting cooperation would be positively, but coparenting conflict and triangulation would be negatively associated with child routines. Third, we hypothesized that consistent child routines would be positively associated with children’s social–emotional competence. Lastly, we hypothesized that mothers’ perceptions of quality coparenting relationships would be positively related to child routines, and in turn, child routines will be positively associated with better social–emotional competence.

Methods

Data Collection Procedures

The University Research Ethics Committee approved data collection procedures. Participants were reached through word of mouth via social media platforms or personal connections of researchers. The data were collected through the online data collection platform Qualtrics between December 2020 and January 2021. The time of data collection represented the second lockdown, including a curfew imposed on weekends except between 10:00 a.m. and 08:00 p.m. Only Turkish heterosexual mothers with children aged between 48 and 72 months old in Turkey were invited to the study. For the aim of the current study, one of the selection criteria was that participating children did not attend any special education institutions or show no developmental delays. We relied on mother reports of children’s developmental states. For the online data collection process, mothers were given an online link through Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) to complete the questionnaires. Mothers were informed about the study’s details and asked about their consent for participating in the research. As compensation, participants were enrolled in a drawing for a children’s book. At the end of the survey, mothers who wanted to participate in the drawing of 30 children’s books were asked to write their phone numbers. We used two methods for data quality assurance. First, we used the attention-check item and removed participants who failed to respond to the attention-check item correctly (n = 13) (Niessen et al., 2016). Second, we called back all participants who provided their phone numbers to ensure that they completed the survey and were aware of it.

Participants

We recruited 413 mothers of children aged between 23 and 102 months old (M = 59.23, SD = 10.92). Initially, the data were screened for the 450 participants: 19 participants who identified themselves as fathers or other caregivers were removed from the data as the initial condition for participating in the study was being a mother. Then, 13 mothers who answered the attention question incorrectly were excluded from the data. Five participants who entered the survey twice were identified, and removed from the data. As part of data quality assurance, we contacted 85% of the mothers (n = 351) to confirm if they had completed the questionnaires accurately. Consequently, one participant who admitted to providing incorrect information was deleted from the dataset. Additionally, another participant with a child aged 243 months was removed from the study, as the measures were not applicable to this age group. After these screening steps, we had 411 participants for further analysis. Mothers’ age ranged from 22 to 50 years (M = 35.85, SD = 4.75), and fathers’ age ranged from 27 to 60 years (M = 39.06, SD = 5.59). A minority (2.2%) of mothers finished primary school, 2.7% finished secondary school, 22.6% finished high school, 56.8% had an undergraduate degree, 14.1% of mothers had a master’s degree, and 1.5% had a doctorate. A minority (1.2%) of fathers finished primary school, 3.5% finished secondary school, 22.8% finished high school, 57.8% had an undergraduate degree, 11.2% had a master’s degree, and 3.5% had a doctorate. A large percentage of mothers reported their marital status as married (95.3%), while 2.9% of the mothers reported as divorced, 0.7% of mothers reported as remarried, 0.5% of mothers reported as single, 0.2% of mothers reported as separated, and 0.2% of mothers reported as cohabiting. The employment status of mothers was that 46.6% reported them as employed, while 53.3% reported them as unemployed during the COVID-19 outbreak. For fathers, 96.0% of the fathers reported them as employed, and 3.9% of the fathers reported them as unemployed. 2.9% of mothers reported monthly family income of between 0TL and 1500TL (~US $ 0–192), 5.7% reported between 1501TL and 3000TL, 20.6% reported 3001TL–5000TL, 16.9% reported 5001TL–7000TL, and 53.8% reported as 7001TL and higher. We created the socioeconomic status (SES) variable by averaging the standardized scores (z-scores) of maternal education, paternal education, and family monthly income. This composite SES variable was used in further analyses.

Measures

Social and Emotional Competence

We used the Ages and Stages Questionnaires: Social–Emotional (ASQ: SE; Squires et al., 2002). The Turkish version of ASQ: SE was adapted to Turkish by Kapcı et al. (2015). As the ASQ was designed with children depending upon their developmental age stage, we used the two sets of forms as one for 48 months (33 items; 42–53 months of children) and 60 months (33 items; 54–72 months old children). Using the ASQ: SE, mothers rated their children’s social–emotional competence in areas of self-regulation, communication, compliance, adaptive behaviors, affect, autonomy, and interaction with people. Parents reported their children’s social and emotional functioning on a 3-point scale (0, 5, or 10 points: “rarely or never”, “sometimes”, and “most of the time”). Considering the purpose of the current study, we used the total score of social–emotional competence by summing all items. This approach has been used in previous research (e.g., Duguay et al., 2021; Eurenius et al., 2018; Pooch et al., 2019; Vaezghasemi et al., 2020) and Kapçı et al. (2015) reported internal consistency as the whole scale, indicating the use of total score to assess children’s global social-emotional competence. We relied on internal consistency (McDonald’s ω and Cronbach’s α; Deng & Chan, 2017; McDonald, 1999) and item-total correlations (Loewenthal, 2004) in creating the composite score. By removing five items (Does your child cling to your more than you expect? Does your child seem too friendly with strangers? Is your child interested in things around him, such as people, toys, and food? Does your child seem more active than other children his age? Does your child explore new places, such as a park or a friend’s home?), our internal consistency was better (>0.70), and all items had an item-total correlation of 0.15 or higher. We summed the remaining items to create the composite social–emotional competence subscale. The internal consistency was 0.796 (Cronbach’s α) and 0.798 (McDonald’s ω) in the current study.

Coparenting

The Coparenting Inventory for Parents with Preschoolers (CI-PP; Pinquart & Teubert, 2015) was used to assess mothers’ perceptions of the coparenting quality. The measure was adapted to Turkish by Acar et al. (2021). The CI-PP is a 12-item scale rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale from 0 (not at all true) to 4 (completely true). The CI-PP assesses three coparenting dimensions, including cooperation (consisting of four items, e.g., “My partner and I talk about child-rearing”), conflict (consisting of four items, e.g., “My partner and I disagree on the rules, goals, and demands of child-rearing”), and triangulation (consisting of four items, e.g., “Our child gets involved in conflicts between my partner and me”). The CI-PP has been validated for children older than the preschool age group (Teubert & Pinquart, 2011). For the current study, the Cronbach α internal reliability coefficients for cooperation were 0.846, for conflict was 0.775, and for triangulation was 0.720 for mother reports.

Child Routines

The Child Routines Questionnaire for preschool-aged children (CRQ-P; Wittig, 2005) was used to assess child routines in daily functioning. The original CRQ-P was a 35-item questionnaire consisting of three subscales: Daily Living, Activities, and Discipline. Parents rated on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (nearly always). As we used this scale for the first time with Turkish mothers, we translated the questionnaire into Turkish. Then, a back-translation was made, and inconsistencies were discussed until a consensus was reached. After all the translation and correction processes ended, the final version of the scale was piloted with several mothers for comprehension of the items. After all these processes were done, the last version of the questionnaire was used for the current study. In the translation process, we removed two items (e.g., “My child attends church with the family weekly” and “My child says prayers before meals and/or before bedtime”) that were not inclusionary of whole Turkish families. This approach was also used in the Chinese translation of the measure (Ren & Fan, 2019). We ran confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to test whether the predefined structure of the scale could be replicated with a Turkish sample using the JASP (JASP Team, 2021). We utilized the following steps to improve the model fit and conceptual comprehensiveness. First, we removed items with nonsignificant and low factor loadings (λ < 0.30; Brown, 2015; Kim & Muller, 1978). Second, items with low item-total correlations were removed (<0.15, Clark & Watson, 1995; Loewenthal, 2004). We utilized unweighted least squares (ULS) in the CFA models as it provides better model convergence with ordinal scales (Forero et al., 2009). The model fit for the final CFA model was acceptable, χ2(296) = 526.167 (p < 0.001), CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.043 (90% CI = 0.037~0.049), SRMR = 0.065. The Daily Living subscale contains 12 items relating to children’s daily living (e.g., “My child eats breakfast at about the same time each morning”). The Activities subscale contains eight items and captures children’s involvement in family and social activities (e.g., “My child engages in regular, planned activities with the family each week”). Lastly, the Discipline subscale contains six items relating to parents’ disciplinary strategies and guidance (e.g., “My child has to follow household rules, such as “No hitting” or “No yelling”). In the current study, we found internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) of 0.81 for daily living, 0.70 for activities, and 0.67 for discipline subscales.

The COVID-19 Pandemic Effects

We used the COVID Impacts Scale to evaluate participants’ experiences with COVID-19 (Conway et al., 2020) and the subscale of within-family interactions during the COVID-19 from Ergül & Yılmaz’s (2020) instrument. Mothers rated the COVID Impacts Scale on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (not true of me at all) to 7 (very true of me). In addition, mothers rated the COVID-19 within-family interactions questionnaire on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (I do not agree at all) to 5 (I totally agree). Given that we used Conway et al.’s (2020) measures for the first time with Turkish parents, we ran confirmatory factor analyses using the JASP (JASP Team, 2021). The model fit for the CFA final model was acceptable, χ2(24) = 97.783 (p < 0.001), CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.086 (90% CI = 0.069~0.104), SRMR = 0.056. Standardized loadings ranged from 0.31 to 97. We found internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) of 0.76 for financial effects, 0.66 for resources, and 0.70 for psychological effects. Internal consistency was 0.91 for the within-family interactions subscale in the current study. We used these variables as covariates in the structural equation model.

Data Analytical Approach

Data Screening

Missing values were detected in a total of three variables. The highest missing data were on social–emotional competence (22.6%); therefore, a Missing Values Analysis was conducted using Little’s (1988) test of Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) to understand the pattern of these missing values. The result of the MCAR test was not significant, χ2 = 15.159, p = 0.298, showing that missing values were completely at random. We used the full information maximum likelihood to handle the missingness in the analyses (Enders, 2010). The multivariate outliers were checked using Mahalanobis Distance (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Eight multivariate outliers were above the χ2 value of 29.59, p < 0.001, and they were deleted from the dataset, leaving 403 participants in total for further analyses. The reason for missing data on social–emotional competence was that 22.6% of children fell outside the age range covered by the ASQ measure. Employing pairwise deletion in the bivariate correlation analysis resulted in a reduced sample size for pairs compared to the original sample size of 403.

We tested normality assumptions by using the criteria of +3 and −3 for skewness and +10 and −10 for kurtosis (Kline, 2011). Our variables were within the acceptable range; therefore, no transformation was employed (see Table 1). The results from the multicollinearity test demonstrated that tolerance ranged from 0.493 to 0.905 and variance inflation factor (VIF) ranged from 1.105 to 2.029, indicating that there was no multicollinearity among variables in the current study (tolerance < 0.10, VIF > 10; Pallant, 2016).

Analytical Approach

Multivariate analyses were conducted in the Mplus8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012), using structural equation modeling (SEM) with maximum likelihood estimation. We followed the two-step model-building approach (Kline, 2011). First, we tested the measurement model, where we created latent factors of coparenting and child routines. Once the measurement model was found to be satisfactory, we tested the hypothesized structural model to examine whether there is an indirect effect of coparenting on children’s social–emotional competence via child routines. Direct paths were added from coparenting to social–emotional competence, from coparenting to child routines, and child routines to social–emotional competence to test the structural model. We utilized the top–down model building where we included all possible covariates, including age, child sex, SES, and the COVID-19-related effects in the model. We then removed the nonsignificant ones by considering the model fit improvement. We tested the significance of the indirect effects by using the bootstrapping technique (1000 resampling) with 95% confidence intervals (MacKinnon et al., 2007). We utilized a 95% bias-corrected bootstrap method, as it provides parsimonious results (MacKinnon et al., 2004). In line with Kline’s (2011) recommendations, comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) values >0.90, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) values of 0.08 or below, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) values of 0.08 or below are employed to indicate a good fit.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

The bivariate correlations (Pearson) were conducted among study variables. Results showed that cooperation was positively (r (312) = 0.272, p < 0.01), conflict (r (312) = −0.313, p < 0.01), and triangulation (r (312) = −0.311, p < 0.01), were negatively associated with children’s social–emotional competence. Children’s social–emotional competence was positively associated with daily living routines (r (312) = 0.473, p < 0.01), activity routines (r (312) = 0.388, p < 0.01), and discipline routines (r (312) = 0.199, p < 0.01) of children. See Table 1 for complete correlation results.

Multivariate Analyses Measurement Model

Grounded on the previous conceptualization of coparenting and child routines and their associations with social–emotional competence (Ren & Xu, 2019), we attempted to build latent factors of coparenting and child routines. We first tested the measurement model where coparenting, which consisted of cooperation, conflict, and triangulation subscales, and child routines which consisted of daily living, activities, and discipline subscales, were latent variables using the CFA in the Mplus8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). The results showed that the measurement model fit the data very well, χ2(8) = 9.01, p = 0.34, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.02, 90% CI [0.00–0.06], SRMR = 0.019. The standardized item loadings ranged from 0.65 to 0.76 for coparenting, and from 0.44 to 0.88 for child routines, meaning that all loadings were acceptable. The results from the measurement model indicated that we could move forward with the structural model (Kline, 2011).

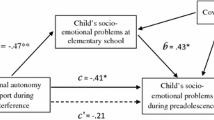

Structural Model

As we followed a top–down model-building approach, in the first model, we included all possible covariates, including age, child sex, SES, and the COVID-19-related effects (financial, resource, psychological, and within-family interactions) in the model. The results of SEM were as follows, χ2(40) = 86.35, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.86., RMSEA = 0.06, 90% CI [0.04, 0.07], SRMR = 0.04. As seen from the model fit indices, there was a room for model improvement. In the competing nested model, we removed the nonsignificant paths from the covariates in the model. We tested the model improvement via a chi-square difference test (Kline, 2011). The results of the chi-square difference test showed that the final model fit the data better than the previous full model, Δχ2(23) = 50.94, p < 0.001. Results from the final structural model showed a good fit to the data, χ2(17) = 33.58, p = 0.01, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.04, 90% CI [0.02, 0.07], SRMR = 0.03. Removing the nonsignificant paths from the covariates in the model did not change the significance of direct and indirect paths in the final model. In this model, coparenting was positively related to children’s social–emotional outcomes, (B = 2.687 (SE = 0.888), β = 0.238, p < 0.001) and child routines (B = 0.335 (SE = 0.073), β = 0.354, p < 0.001). Besides, child routines were positively related to children’s social–emotional outcomes (B = 5.085 (SE = 0.978), β = 0.427, p < 0.001). The final model is depicted in Fig. 1.

The indirect effect from coparenting to social–emotional competence was tested using 1000 bootstraps with 95% CIs. The indirect path specifically indicating that child routine significantly mediated the effects of coparenting on children’s social–emotional competence was found to be significant (β = 0.15 (SE = 0.034), [95% CI: 0.091, 0.228]).

Sensitivity Analysis

Given the wide age range of children included in our study, spanning from 23 to 102 months, we sought to assess whether our findings remained consistent specifically for preschool-aged children, aligning with the variables under investigation. Initially, we conducted a bivariate analysis by excluding children above the age of 72 months (n = 32). The results of this analysis indicated that there were no significant differences in the levels of associations within the new dataset. Furthermore, we conducted a structural multivariate model (in SEM) after excluding the same children as in the bivariate analysis. The significance of the results did not differ from those obtained with the original dataset including all children. Both sets of results offer support for the conclusion that the age range of the children did not pose a limitation in the models tested.

Finally, we tested the following child-driven model in addition to the parent-driven model initially tested. In the child-driven model, we tested the indirect effect of children’s social–emotional competence on coparenting quality via child routines. Results from the structural model showed that children with better social–emotional competence were more likely to display higher levels of routines at home, and better routines were also related to better coparenting. Considering the cross-sectional nature of the data, we believe that this child-driven model provided a compensating argument to our initially tested parent-driven model.

Discussion

The current study aimed to investigate the roles of mothers’ perception of coparenting and child routines on children’s social–emotional competence with a particular interest in testing the indirect effect of coparenting on children’s social–emotional competence via child routines. We found a significant indirect effect of coparenting quality on children’s social–emotional competence via child routines. Considering the purpose of the current study, the following sections discuss the findings.

Coparenting Quality and Children’s Social–Emotional Competence

The first hypothesis of the study examined the role of mothers’ perception of coparenting quality on children’s social–emotional competence as rated by their mothers. Our result from the current study confirmed our hypothesis by revealing a statistically significant direct effect of coparenting on children’s social–emotional competence. More specifically, in bivariate analyses, we found that children’s social–emotional competence was negatively associated with coparental conflict and triangulation and positively associated with cooperation. The previous meta-analysis found (Teubert & Pinquart, 2010) significant associations between coparental cooperation and conflict with social functioning but did not find significant associations of coparental triangulation with social functioning. Coparenting triangulation, which includes the involvement of the child in parental conflicts and creating a coalition between one parent and a child, is considered to result from conflict between coparents (Feinberg, 2003). As seen from the operational definition, coparental triangulation, which represents the negative aspect of coparenting and undermines quality coparenting relationships, is known to have a negative effect on children (Gurmen, 2019). Our result indicated a significant association between coparental triangulation and the social–emotional competence of children. The reason why we observed a negative correlation between coparental triangulation and children’s social–emotional might be because parents who triangulate their children might model inefficient and negative strategies for their children. As a consequence, children may internalize their parents’ behavior and may have difficulty in their social-emotional functioning. Another explanation might be that coparental triangulation might threaten children’s sense of security, and therefore children might engage in less socially and emotionally competent behavior. This result may support the idea that during early childhood, preventing children from being involved in interparental conflict and avoiding forcing them to choose sides during conflicts to maintain the balance of family systems may be especially important for children’s social–emotional development (Feinberg, 2003).

Child Routines and Children’s Social–Emotional Competence

The finding regarding the significant direct association between child routines and social–emotional competence suggests that child routines during COVID-19 are associated with children’s social–emotional competence. This result was supported by the previous work that outlined the crucial role of child routines for child social-emotional adjustment (Bater & Jordan, 2017; Ferretti & Bub, 2014). In particular, both bivariate and multivariate analyses showed significant relationships between child routines and social–emotional competence, which supported our hypothesis, stating that there would be a positive relationship between child routines and children’s social–emotional competence. In other words, implementing consistent routines could support greater social–emotional competence. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that providing consistent routines is associated with better social–emotional competence in Turkish children. Previous findings have established the importance of implementing consistent routines on children’s social and emotional outcomes, consistent with our findings (Muñiz et al., 2014; Ren & Xu, 2019). For instance, Muñiz et al. (2014), studying the role of children’s participation in family routines on preschoolers’ social–emotional health, found a positive correlation between routines and children’s ability to understand and express emotions, building positive relationships with others, and displaying high self-regulatory skills. Additionally, our results showed that child routines were more strongly associated with children’s social–emotional competence (β = 0.427) compared to coparenting quality (β = 0.238), suggesting that having more consistent routines may have a greater influence on social–emotional competence. Providing anticipatory guidance on children’s activities and encouraging them to participate in predictable and consistent routines may ensure a sense of predictability and security in the environment (Fiese et al., 2002). Therefore, children with more consistent routines may be better able to control their behavior in predictable and secure environments and manage appropriate social and emotional behaviors.

Indirect Effect of Coparenting on Children’s Social–Emotional Competence Through Child Routines

The result showed a direct association between coparenting and child routines. As mentioned earlier, establishing consistent routines is considered as an extension of positive parenting practices (Bater & Jordan, 2017). Besides, quality coparenting necessitates couples to coordinate with each other, manage the division of duties, uphold the other’s positive parenting practices, and share the responsibility for raising their child (Feinberg, 2003). Establishing structured and consistent routines are also related to the aforementioned components of coparenting, and this may be because we found an association between quality coparenting and consistent child routines.

Finally, and most importantly, our findings showed an indirect effect of coparenting on children’s social–emotional competence via child routines. We acknowledge that testing mediating effect in the absence of longitudinal data would be problematic (Agler & De Boeck, 2017). From this point of view, our significant result from this model could be interpreted as an indirect effect rather than a pure mediation. Overall, there was a tendency for children whose parents exhibited higher quality coparenting relationships to also have more consistent routines. Furthermore, higher levels of consistency in child routines were associated with increased social–emotional competence. Aligned with our expectations, findings from the current study are consistent with previous research conducted with Chinese children showing that consistent child routines mediated the effects of coparenting on the association between coparenting and social–emotional development (initiative, self-control, and behavioral concerns) (Ren & Xu, 2019). Based on the results, we can suggest that a quality coparenting relationship, which is considered to have an essential role in positive child outcomes according to Family System theory (Minuchin, 1974), may promote a sense of security and predictability in the home environment. In addition, when parents coordinate with each other in their roles as parents and support their decisions in child-rearing practices, children may receive more consistent environmental cues and feel more certain about their parent’s expectations, and in turn, children may be better able to show higher social–emotional competence (Karreman et al., 2008). Consequently, children may be more likely to perform consistent routines. When we consider the indirect effect of coparenting on children’s social–emotional competence through child routines, we can say that children who have parents with quality coparenting relationships may be provided with more consistent routines, and consistent child routines also promote predictability and security in the environment, in turn, children engage in more socially and emotionally competent behaviors.

Making Sense of the Results in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The current period of the COVID-19 pandemic has led to significant changes in the daily life of families (Barata & Acar, 2022; Adadms et al., 2020; Toran et al., 2021). It is likely that the COVID-19 lockdown may be particularly challenging for parents who are dealing with financial difficulties, problems with their spouses, and the increased burden of raising a child (Fontanesi et al., 2020). Therefore, it is important to examine the role of the current pandemic on parents and children to mitigate the impact of COVID-19. This study examined the impacts of COVID-19 on financial, resource, psychological, and within-family interaction domains. It is important to highlight that the current study’s sample scored higher on COVID-19 within-family interactions and relatively lower on the resource and financial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Even though we expected to find an adverse impact of COVID-19 on families in areas such as family relations, economy, psychology, and resources, our sample did not seem to be adversely affected by this situation as much as we expected. The current study’s sample consisted of parents with medium and high socioeconomic status, and this may be because they were affected less by the COVID-19-related impacts. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the results considering the characteristics of the current study’s sample.

The current study provided evidence addressing the indirect effect of coparenting on children’s social–emotional competence through child routines during the COVID-19 outbreak. Results showed that the psychological impact of COVID-19 was negatively, and higher quality of family interactions during COVID-19 was positively correlated with children’s social–emotional competence. Previous studies have shown the importance of positive family interaction on the social–emotional development of children in the early years of life (Landy, 2009). Supportive family environments which contain positive family interactions may likely serve as protective factors against the negative consequences of COVID-19. Besides, family interactions during COVID-19 were found to be positively related to coparenting quality and consistent child routines. Families with positive family interactions may also support each other in their role as a parent, which may also be promotive in the context of COVID-19. Having positive family interactions during the COVID-19 pandemic might be linked to more positive family dynamics, which then might influence the functioning of the family system that impacts children’s adjustment (Cox & Paley, 1997; Feinberg, 2003). Considering the interrelated nature of subsystems contributing to child development, families having positive interactions during COVID-19 might protect the balance of the family system, and this might positively affect the functions of the family subsystems and child outcomes. Previous research found that mothers who received support from their spouses during COVID-19 were better able to engage in adaptive parenting behaviors (Uzun et al., 2021). Besides, establishing consistent routines may be essential for families during COVID-19, an absolutely stressful and unpredictable event. We asked parents to rate their children given for each routine considering the last month. The result showed the direct contribution of child routines on children’s social–emotional competence during COVID-19. Providing consistent routines during COVID-19 may serve as an effective way that enables parents to provide children with a predictable home environment. Therefore, providing consistent routines can help structure the day and create a secure environment for the children. This sense of security might help children feel safer during COVID-19, which may consequently improve the social–emotional competence of children (Fiese et al., 2002). This study provides an important perspective on how the secure and predictable environment provided by families during the pandemic can be related to the social-emotional development of children. By emphasizing the significance of routines among the factors associated with children’s social-emotional development, this study can assist families in shaping their parenting strategies for the post-pandemic period.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy to highlight that our analysis revealed no significant associations between the age of children and their social–emotional competence, child routines, or coparenting. Despite the wide age range encompassed by our sample, ranging from ~2 to 8 years old, age was not significantly related to study variables. This finding suggests that the relationships observed between routines, social–emotional competence, and coparenting dynamics were consistent across different developmental stages within our sample. While age-related differences in routines and social–emotional development are expected, our results indicate that these factors may operate independently of age within the context of our study. Nevertheless, from a developmental perspective, parents should consider a child’s developmental level when establishing routines and coparenting dynamics in home context.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

While previous studies have explored the impact of daily routines on adolescents’ well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic (Ren et al., 2021), little attention has been paid to understanding child routines in early childhood, especially in the Turkish context. This gap in the literature underscores the importance of our study, which, to our knowledge, is the first to empirically examine the role of child routines as a mediator in the relationship between coparenting and social–emotional competence amid the COVID-19 outbreak. By focusing on coparenting dynamics and child routines in the context of the pandemic, our study strengthened the existing literature by providing novel insights into the mechanisms underlying children’s social–emotional competence within the Turkish cultural context. This research fills a significant gap in the literature and contributes to a deeper understanding of the factors that contribute to the children’s well-being during challenging times.

It is important to consider the limitations of the study while interpreting the findings. First, our sample was primarily comprised of medium–high SES families, which limits the generalizability of our results. Children with low SES backgrounds may have different experiences with COVID-19. The reason why our sample scored relatively lower on the COVID Impacts Scale might be because of our sample’s high socioeconomic status. We conducted our study using an online survey on the Qualtrics platform, restricting our sample to participants with internet access.

Second, we used a cross-sectional online survey, which prevented us from making causal inferences. Even though the ordering of our construct in the model was based on the previous research (Ren & Xu, 2019), alternative ordering may exist since there may be a bidirectional relationship between coparenting and child routines. We did not have longitudinal data to understand the pure mediating mechanism. Further longitudinal research is needed to understand the mechanism and causal relationship between coparenting, child routines, and social–emotional competence during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Furthermore, the coparenting relationship involves mothers’ and fathers’ collaboration in child-rearing. Mothers and father may perceive their coparenting behavior differently (Acar et al., 2021). Therefore, it would be beneficial to address both fathers about their partners’ coparenting. It would be beneficial to include both parents’ perceptions of their coparenting behavior and their relation to children’s social–emotional competence for further research. Nevertheless, there were two reasons behind recruiting mothers for the current study. First, mothers, as the main care provider for children, has experienced extensive burden with lockdowns and providing care and education for their children. Second, access to mothers during the pandemic than to fathers was rather easier to obtain reports about the family and children.

In addition, the social–emotional development of children can be measured more accurately by experts in the field through observation. Mothers may occasionally miss certain aspects of the social–emotional progress their children exhibit. Therefore, a more reliable measurement method would involve relying on the parents’ reports and incorporating observations from both parents. In addition, using self-report of mothers only could potentially create common-method bias in the current study. Having different information, such as fathers or teachers, and different data collection methods, such as observation, can help reduce common-method bias in future studies.

Moreover, the questions under the COVID-19 pandemic effects focused solely on the views of mothers on the economic, resource, and psychological effects they experienced during the pandemic. Specifically only the questions under family interaction directly addressed interactions between family members during COVID-19. However, further research may address more comprehensive questions directly to children to understand potential changes in behavior and emotional well-being of children, as well as differences in their daily routines during COVID-19.

Implications of the Current Study

Given the importance of supporting social–emotional competence in the early years of life (Shonkoff et al., 2000; Denham, 2006), the current findings might provide implications for researchers, parents, and teachers. Primarily, findings from the current study can provide an understanding of children’s social–emotional competence from family systems theory, wherein the interrelated nature of subsystems contributes to child development. Previous findings showed the roles of coparenting on child development, leading to the implementation of intervention studies regarding enhancing the coparenting quality. For example, Family Foundations, a preventive intervention program, aimed to improve the coparenting relationship to have a long-term positive impact on child well-being (Feinberg et al., 2009). Results showed that parents who participated in intervention programs before the child’s birth reported enhancement in child adjustment, including child self-regulation, when their child was 1 and 3 years of age (Feinberg et al., 2009). Therefore, coparenting interventions should be developed for parents to improve their relationship as a couple and contribute to their children’s well-being.

Considering the results of the current study, which suggest the importance of consistent child routines on children’s social and emotional development, intervention programs should also focus on implementing consistent child routines. Practitioners may help parents establish consistent routines in different dimensions, such as discipline, activities, and daily living. Practitioners may also collaborate with schools and teachers to find required strategies for implementing and maintaining routines in the classroom environment, as schools and teachers play a crucial role in the development of children’s social–emotional skills, and the majority of children ages between 4 and 6 spend their time at school (Denham et al., 2012; Wildenger et al., 2008). Another implication of the current study is that interventions designed to promote both coparenting quality and child routines may improve children’s social–emotional competence. For example, when designing an intervention program that targets increasing coparenting quality, couples can be given information on the importance of establishing consistent routines for their children and how they should cooperate to establish daily routines. In this way, the program may obtain better outcomes in enhancing children’s social–emotional competence than programs that only support families in coparenting or child routines.

Most importantly, the current study has an important place in examining the coparenting relationship, child routines, and children’s social–emotional competence in the COVID-19 outbreak. This study highlights the importance of child routines and family dynamics during the pandemic, offering concrete insights into how families can support their children during this challenging period. As the COVID-19 pandemic, which has put some responsibilities on parents, may hinder their ability to support children’s social–emotional competence compared to the past, it is warranted to pay further attention to support children (Wang et al., 2020). Therefore, policymakers should adopt preventive interventions to protect families from the negative impact of COVID-19 and increase the well-being of families and children, which may seem especially essential during COVID-19. Providing free psychoeducation to parents and helping them recognize pathways to children’s and families’ well-being during COVID-19 may be an effective intervention to strengthen children’s social–emotional competence. Based on the current study’s findings showing the importance of supporting coparenting relationships in helping children establish consistent routines, families may be supported online to develop coparenting skills and implement daily routines during the pandemic, which could potentially contributes to children’s social–emotional competence. Effective interventions and further research are needed to mitigate the current and long-term impact of COVID-19 on families and their children.

References

Acar, I. H., Ece, C., Saral, B., & Gürmen, S. (2021). Evaluating psychometric properties of the coparenting inventory with Turkish mothers and fathers of preschool children. Current Psychology, 41, 7777–7787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01213-1.

Adadms, E. L., Smith, D., Caccavale, L. J., & Bean, M. K. (2020). Parents are stressed! Patterns of parent stress across COVID-19. Research Square, rs.3, rs-66730. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-66730/v2.

Agler, R., & De Boeck, P. (2017). On the interpretation and use of mediation: Multiple perspectives on mediation analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1984. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01984.

Babore, A., Lombardi, L., Viceconti, M. L., Pignataro, S., Marino, V., Crudele, M., Candelori, C., Bramanti, S. M., & Trumello, C. (2020). Psychological effects of the COVID-2019 pandemic: Perceived stress and coping strategies among healthcare professionals. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113366.

Barata, Ö., & Acar, I. H. (2022). Turkish children’s bedtime routines during the COVID-19 pandemic: Preliminary evaluation of the bedtime routines questionnaire. Children’s Health Care. https://doi.org/10.1080/02739615.2022.2134133.

Bater, L. R., & Jordan, S. S. (2017). Child routines and self-regulation serially mediate parenting practices and externalizing problems in preschool children. Child & Youth Care Forum, 46(2), 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-016-9377-7.

Boričević Maršanić, V., & Kušmić, E. (2013). Coparenting within the family system: Review of literature. Collegium Antropologicum, 37(4), 1379–1384.

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8.

Brown, S. M., Doom, J. R., Lechuga-Peña, S., Watamura, S. E., & Koppelds, T. (2020). Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110, 104699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699.

Brown, T. A. (2015). Methodology in the social sciences. In Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Chu, K. A., Schwartz, C., Towner, E., Kasparian, N. A., & Callaghan, B. (2021). Parenting under pressure: A mixed-methods investigation of the impact of COVID-19 on family life. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 5, 100161.

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1995). Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment, 7(3), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/14805-012.

Cluver, L., Lachman, J. M., Sherr, L., Wessels, I., Krug, E., Rakotomalala, S., Blight, S., Hillis, S., Bachman, G., Green, O., Butchart, A., Tomlinson, M., Ward, C. L., Doubt, J., & McDonald, K. (2020). Parenting in a time of COVID-19. The Lancet, 395(10231). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30736-4.

Conway III, L. G., Woodard, S. R., & Zubrod, A. (2020). Social psychological measurements of COVID-19: Coronavirus perceived threat, government response, impacts, and experiences questionnaires. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/z2x9a.

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 48(1), 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243.

Deng, L., & Chan, W. (2017). Testing the difference between reliability coefficients alpha and omega. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 77(2), 185–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164416658325.

Denham, S. A. (2006). Social-emotional competence as support for school readiness: What is it and how do we assess it? Early Education and Development, 17(1), 57–89. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15566935eed1701_4.

Denham, S. A., Bassett, H. H., & Zinsser, K. (2012). Early childhood teachers as socializers of young children’s emotional competence. Early Childhood Education Journal, 40(3), 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-012-0504-2.

Duguay, G., Lemieux, R., Martel, E., Losielle, M., Garon-Bissinnette, J., Drouin-Maziafe, C., Dubois-Comtois, K., & Berthelot, N. (2021). Maternal prenatal and postnatal distress during the COVID-19 pandemic and infants’ early socioemotional development [paper presentation]. Society for Research in Child Development Biennial Conference, Virtual.

Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Press.

Ergül, B., & Yılmaz, V. (2020). Covid-19 salgını süresince aile içi ilişkilerin doğrulayıcı faktör analizi ile incelenmesi. IBAD Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, (Özel Sayı), 38–51. https://doi.org/10.21733/ibad.733909.

Eurenius, E., Richter Sundberg, L., Vaezghasemi, M., Silfverdal, S.-A., Ivarsson, A., & Lindkvist, M. (2018). Social-emotional problems among three-year-olds differ based on the child’s gender and custody arrangement. Acta Paediatrica. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.14668.

Feinberg, M. E. (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice, 3(2), 95–131. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01.

Feinberg, M. E., Kan, M. L., & Goslin, M. C. (2009). Enhancing coparenting, parenting, and child self-regulation: Effects of family foundations 1 year after birth. Prevention Science, 10(3), 276–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-009-0130-4.

Ferretti, L. K., & Bub, K. L. (2014). The influence of family routines on the resilience of low-income preschoolers. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35, 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.03.003.

Fiese, B. H., & Everhart, R. S. (2008). Routines. Encyclopedia of infant and early childhood development (pp. 34–41). Boston, MA: Elsevier Academic.

Fiese, B. H., Tomcho, T. J., Douglas, M., Josephs, K., Poltrock, S., & Baker, T. (2002). A review of 50 years of research on naturally occurring family routines and rituals: Cause for celebration? Journal of Family Psychology, 16(4), 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.16.4.381.

Fontanesi, L., Marchetti, D., Mazza, C., Di Giandomenico, S., Roma, P., & Verrocchio, M. C. (2020). The effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on parents: A call to adopt urgent measures. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(1), 79–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000672.

Forero, C. G., Maydeu-Olivares, A., & Gallardo-Pujol, D. (2009). Factor analysis with ordinal indicators: A Monte Carlo Study comparing DWLS and ULS estimation. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 16(4), 625–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510903203573.

Gurmen, M. S. (2019). Çocukla gelen ve hiç bitmeyen ilişki: Ortak ebeveynlik. Türk Psikoloji Yazıları, 22(44), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.31828/tpy1301996120181126m000010.

JASP Team (2021). JASP (Version 0.14.1) [Computer software].

Jordan, S. S. (2003). Further validation of the Child Routines Inventory (CRI): Relationship to parenting practices, maternal distress, and child externalizing behavior. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Kapçı, E. G., Küçüker, S., & Uslu, R. I. (2015). Erken Gelişim Evreleri Envanteri El Kitabı. Ankara: Eğiten Kitapevi.

Karreman, A., Van Tuijl, C., Van Aken, M. A., & Deković, M. (2008). Parenting, coparenting, and effortful control in preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.30.

Kim, J. O., & Mueller, C. W. (1978). Factor analysis: Statistical methods and practical issues. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press.

Ladd, G. W. (2005). Children’s peer relations and social competence: A century of progress. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

Landy, S. (2009). Pathways to competence: Encouraging healthy social and emotional development in young children. Paul H Brookes Publishing.

Lee, J. (2020). Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(6), 421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7.

Little, R. J. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.2307/2290157.

Loewenthal, K. M. (2004). An introduction to psychological tests and scales (2nd ed.) Hove: Psychology Press..

MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J., & Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593–614. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4.

Masten, A. S., & Osofsky, J. D. (2010). Disasters and their impact on child development: Introduction to the special section. Child Development, 81(4), 1029–1039.

McCoy, D. C., Cuartas, J., Behrman, J., Cappa, C., Heymann, J., López Bóo, F., Lu, C., Raikes, A., Richter, L., Stein, A., & Fink, G. (2021). Global estimates of the implications of COVID‐19‐related preprimary school closures for children’s instructional access, development, learning, and economic wellbeing. Child Development, 92(5), e883–e899.

McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

McHale, J. P., Lauretti, A., Talbot, J., & Pouquette, C. (2002). Retrospect and prospect in the psychological study of coparenting and family group process. In J. P. McHale, & W. S. Grolnick (Eds.), Retrospect and prospect in the psychological study of families (pp. 127–165). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Minuchin, S. (1974). Families & family therapy. Harvard U. Press.

Minuchin, P. (1985). Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development, 56(2), 289–302.

Muñiz, E. I., Silver, E. J., & Stein, R. E. K. (2014). Family routines and social-emotional school readiness among preschool-age children. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 35(2), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000021.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus Version 7 user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Niessen, A. S. M., Meijer, R. R., & Tendeiro, J. N. (2016). Detecting careless respondents in web-based questionnaires: Which method to use? Journal of Research in Personality, 63, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.04.010.

Pallant, J. (2016). SPSS Survival Manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS program (6th ed.) London, UK: McGraw-Hill Education..

Pinquart, M., & Teubert, D. (2015). Links among coparenting behaviors, parenting stress, and children’s behaviors using the new German coparenting inventory. Family Science, 6(1), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/19424620.2015.1065284.

Pitchik, H. O., Tofail, F., Akter, F., Sultana, J., Shoab, A. K. M., Huda, T. M., Forsyth, J. E., Kaushal, N., Jahir, T., Yeasmin, F., Khan, R., Das, J. B., Hossain, Md. K., Hasan, Md. R., Rahman, M., Winch, P. J., Luby, S. P., & Fernald, L. C. (2021). Effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic on caregiver mental health and the child caregiving environment in a low‐resource, rural context. Child Development, 92(5), e764–e780.

Pooch, A., Natale, R., & Hidalgo, T. (2019). Ages and stages questionnaire: Social–emotional as a teacher-report measure. Journal of Early Intervention, 41(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815118795843.

Qian, Y., Chen, F., & Yuan, C. (2020). The effect of co-parenting on children’s emotion regulation under fathers’ perception: A moderated mediation model of family functioning and marital satisfaction. Children and Youth Services Review, 119, 105501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105501.

Ren, H., He, X., Bian, X., Shang, X., & Liu, J. (2021). The protective roles of exercise and maintenance of daily living routines for Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 quarantine period. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.026.

Ren, L., & Fan, J. (2019). Chinese preschoolers’ daily routine and its associations with parent-child relationships and child self-regulation. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 43(2), 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025418811126.

Ren, L., Hu, B. Y., & Song, Z. (2019). Child routines mediate the relationship between parenting and social-emotional development in Chinese children. Children and Youth Services Review, 98, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.12.016.

Ren, L., & Xu, W. (2019). Coparenting and Chinese preschoolers’ social-emotional development: Child routines as a mediator. Children and Youth Services Review, 107, 104549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104549.

Saral, B., & Acar, I. H. (2021). Preschool children’s social competence: The roles of parent–child, parent–parent, and teacher–child relationships. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2021.1985557

Scrimgeour, M. B., Blandon, A. Y., Stifter, C. A., & Buss, K. A. (2013). Cooperative coparenting moderates the association between parenting practices and children’s prosocial behavior. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(3), 506–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032893.

Shonkoff, J., Phillips, D. A., & Council, N. R. (Eds.) (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Squires, J., Bricker, D., Heo, K., & Twombly, E. (2002). Ages & Stages Questionnaires: Social-Emotional: A parent-completed, child-monitoring system for social-emotional behaviors. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Sytsma, S. E., Kelley, M. L., & Wymer, J. H. (2001). Development and initial validation of the child routines inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23(4), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012727419873.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education.

Teubert, D., & Pinquart, M. (2010). The association between coparenting and child adjustment: A meta-analysis. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10(4), 286–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2010.492040.

Teubert, D., & Pinquart, M. (2011). The coparenting inventory for parents and adolescents (CI-PA): Reliability and validity. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 27(3), 206–215. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000068.

Toran, M., Sak, R., Xu, Y., Şahin-Sak, İ. T., & Yu, Y. (2021). Parents and children during the COVID-19 quarantine process: Experiences from Turkey and China. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X20977583

Uzun, H., Karaca, N. H., & Metin, Ş. (2021). Assesment of parent-child relationship in Covid-19 pandemic. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105748.

Vaezghasemi, M., Eurenius, E., Ivarsson, A., Richter Sundberg, L., Silfverdal, S. A., & Lindkvist, M. (2020). Social-emotional problems among Swedish three-year-olds: An Item Response Theory analysis of the Ages and Stages Questionnaires: Social-Emotional. BMC Pediatrics, 20, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-2000-y.

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 corona virus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729.

Watson, W. H. (2012). Family systems. In V. Ramachandran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (2nd ed., pp. 184–193). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-375000-6.00169-5.

Wildenger, L. K., McIntyre, L. L., Fiese, B. H., & Eckert, T. L. (2008). Children’s daily routines during kindergarten transition. Early Childhood Education Journal, 36(1), 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-008-0255-2.

Wisner, B., Paton, D., Alisic, E., Eastwood, O., Shreve, C., & Fordham, M. (2018). Communication with children and families about disaster: Reviewing multi-disciplinary literature 2015–2017. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(9). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-018-0942-7

Wittig, M. M. (2005). Development and validation of child routines questionnaire: Preschool. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Louisiana State University.

Yates, T., Ostrosky, M. M., Cheatham, G. A., Fettig, A., Shaffer, L., & Santos, R. M. (2008). Research synthesis on screening and assessing social-emotional competence. http://csefel.vanderbilt.edu/documents/rs_screening_assessment.pdf

Zajicek-Farber, M. L., Mayer, L. M., Daughtery, L. G., & Rodkey, E. (2014). The buffering effect of childhood routines: Longitudinal connections between early parenting and prekindergarten learning readiness of children in low-income families. Journal of Social Service Research, 40(5), 699–720.

Acknowledgements

This paper is an extended version of the first author’s master’s thesis.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sezer, Ş.N., Acar, İ.H. The Roles of Mother-Perceived Coparenting and Child Routines on Children’s Social–Emotional Competence During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Child Fam Stud (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-024-02870-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-024-02870-7