Abstract

The concept of parental burnout has been proposed to be helpful for describing and understanding the impact of parenting children with complex care needs (CCN). The objective of this scoping review was to investigate, among parents of children with CCN (i) how burnout is conceptualized, (ii) differences in burnout scores, (iii) the prevalence of burnout, and (iv) the associated factors related to burnout. A stakeholder consultation including parents of children with CCN, healthcare professionals, and researchers, was conducted to understand their perspectives on important insights and gaps from the literature. A total of 57 studies were eligible for inclusion. Conceptualization of parental burnout varied widely across studies, with few studies investigating the meaning of the concept for parents. Burnout scores were higher among parents of children with CCN and prevalence estimates varied between 20 and 77%, and exceeded burnout among parents of children without CCN. Few studies included associated factors in the context of parenting and caregiving. Stakeholders endorsed the importance of studies into the multifactorial determination of burnout in the context of parenting and caregiving children with CCN. The results highlight the extremes of stress and burden experienced by parents of children with CCN. An important gap remains understanding the complex interplay between personal and contextual factors pertaining to risk and resilience.

Highlights

-

Burnout among parents of children with CCN is not a rare phenomenon, therefore awareness and particularly acknowledgement and recognition among these parents in the clinical practice is necessary.

-

The double role of parenting and caregiving limits the relevance of the knowledge base on job-related burnout, requiring a contextualized research approach.

-

The broad variation in domains of burnout and operationalizations used limit the coherence of the body of research.

-

There is a need for an actionable theoretical model of the causes and consequences of burnout among parents of children with CCN.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Parenting is rewarding but challenging, especially among parents of children with complex care needs (CCN), defined as “…those who have or are at increased risk of chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional conditions and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children in general” (McPherson et al., 1998, p. 138). These parents face unique demands, including uncertainty about their child’s condition, complex caregiving tasks at home, and routines to meet the child’s needs (Power et al., 2019). Research has shown heightened parenting stress (Cousino & Hazen, 2013; Golfenshtein et al., 2015), anxiety, and depression among parents of children of CCN compared to parents of typically developing children (Barreto et al., 2020; van Oers et al., 2014). The concept of ‘parental burnout’ has been introduced to describe how prolonged exposure to parenting-related risks may have severe long-term psychosocial effects. However, the conceptualization and associated factors of burnout in parents of children with CCN may be different because of the unique demands of this situation. Therefore, parents of children with CCN have been advocating for research attention toward the risk of prolonged parenting-related strain, parental burnout, and potential risk factors (Bjornstad et al., 2019; McIntyre et al., 2010; Vereniging van mensen met een lichamelijke handicap, 2018).

Parental burnout has been conceptualized as a manifestation of exhaustion due to long-term emotional strain and insufficient resources for coping (Hubert & Aujoulat, 2018), although other definitions have been proposed as well. It has been characterized along the interrelated dimensions of (1) emotional exhaustion related to one’s parental role, (2) emotional distancing from one’s child, (3) contrast with one’s previous parental self, and (4) feelings of being fed up with one’s parental role (Roskam et al., 2018). Emotional exhaustion refers to the feeling of being immensely drained, and no longer being able to carry on in one’s parental role. Such feelings may result in detachment from the child, limiting interactions to functional aspects at the expense of emotional investment. Furthermore, parents may consider themselves less like parents and lose the enjoyment of being there for their child (Hubert & Aujoulat, 2018; Roskam et al., 2018).

In the general population, parental burnout has been described in relation to negative outcomes for parents themselves such as escape and suicidal ideation, somatic complaints, and domestic conflicts (see e.g., Mikolajczak et al., 2018; Sarrionandia-Pena, 2019) and for their children (Hubert & Aujoulat, 2018; Mikolajczak et al., 2018). A recent global study revealed that the prevalence of parental burnout in the general population ranged between 0 and 9% (Roskam et al., 2021). Parents of children with CCN, may be particularly vulnerable due to factors such as assisting with daily activities and/or medical tasks, adjusting lifestyles to accommodate children’s disability, and coping with uncertainty related to illness progression and health deterioration (see, e.g., Hodapp et al., 2019; Power et al., 2019; Woodgate et al., 2015). As a result, burnout in this population may also exhibit unique features and be influenced by different factors compared to parents in general.

The review by Sánchez-Rodríguez et al. (2019) reported a surge of studies on parental burnout, with about 60% concerning parents of children with CCN. This surge was also confirmed by a more recent systematic review by Mroskova et al. (2020) which focused on factors related to burnout among parents of children with CCN. However, their study included only quantitative studies published between 2004 and 2018, resulting in nine included papers. A comprehensive review that includes quantitative, qualitative, mixed-methods studies, and gray literature may help understand the complex interplay between personal and contextual factors in the lives of families with children with CCN and further guide future research.

A scoping review can guide the focus of questions and research design in fruitful directions, especially when the literature has not been comprehensively reviewed (Munn et al., 2018). Furthermore, as suggested by Levac et al. (2010), a stakeholder consultation can be included as part of a scoping review to enhance the social validity of the research and the relevance of the remaining research gaps. Stakeholders’ perspectives may help focus on issues that are expected to be most relevant for scientists and professionals working on the topic of burnout, preventing redundant research and focusing on key areas of importance.

The objective of this scoping review was to describe and understand what is known in the literature about burnout among parents of children with CCN and to identify remaining gaps. We viewed parents as those who have parental duties and rights based on cultural expectations, such as mothers, fathers, stepparents, adoptive parents and primary informal caregivers. The following research questions were investigated: (1) how is burnout in parents of children with CCN conceptualized? (2) what differences have been described compared to parents of children without CCN on burnout scores and/or on the dimensions of burnout? (3) what is known about prevalence of burnout related symptoms? (4) what associated factors have been studied that relate to burnout? The answers and conclusions to these research questions were discussed and formulated in conjunction with stakeholders by applying the following research question: (5) what do stakeholders consider as important insights and gaps based on the findings from research questions 1–4?

Methods

Design

This scoping review followed the Johanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual (Peters et al., 2020) and included a stakeholder consultation consisting of interviews, questionnaires, and a focus group. Hence, this study adopted a participatory approach, which was inspired by the project group consisting of two parents of children with CCN who initiated the project, a professional working with parents of children with CCN, and four researchers. Additionally, two more parents of children with CCN provided input in the study’s early stages to shape the research question and design. This approach emphasized stakeholder involvement at every step of the research.

Ethical approval for the stakeholder consultation was granted by the Scientific and Ethical Review Board (VCWE #2020-147) of the Faculty of Behavioral and Movement Sciences, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. The objectives and methods of this scoping review were outlined in a protocol registered on Open Science Framework (OSF), accessible via https://osf.io/v3mg4?view_only=b8142a3d75e443dab64d10d150e9f943%20. The literature review data are available in OSF at https://osf.io/j59r8/?view_only=6728c7f44bd74ed690422824e44197b7 (data extraction form). However, due to privacy and ethical considerations, data from the stakeholder consultation cannot be publicly shared, but can be shared upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

Scoping Review

Identifying relevant studies

The literature search was performed in collaboration with a university librarian (MM). The following academic databases were searched: Medline (PubMed), Embase.com, Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO (Ebsco), CINAHL (Ebsco) and ERIC (Ebsco). Google Scholar and sources for gray literature (opengrey.eu, lens.org, oaister.worldcat.org, science.gov, base-search.net, and diva-portal.org) were also searched. The gray literature was searched to complement the peer-reviewed literature, rather than being exhaustive. The search strategies combined the key words “parents”, “informal caregivers”, “family caregivers” and “burnout”. No limitations were applied, except for comments, editorials and letters.

This review did not include studies on related concepts such as “stress” or “strain” if burnout was not also studied. Burnout is a possible but not inevitable outcome of long-term stress or strain (Hubert & Aujoulat, 2018; Liu et al., 2023; Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018), and has been associated with severe outcomes such as suicidal ideation, substance abuse among parents, domestic conflict, and violence and neglect toward the child (Mikolajczak et al., 2018). Therefore, this concept warrants a focused review (Mikolajczak et al., 2020; Roskam et al., 2017). Furthermore, an abundance of studies, including systematic reviews, have already been conducted regarding stress experienced by parents of children with CCN (e.g., see Cousino & Hazen, 2013).

The search strings for each academic database can be accessed on OSF via https://osf.io/j7btv/?view_only=40027d01d59a421393c0ca4f8501680a. To retrieve relevant records from gray sources the phrase “parental burnout” was used.

Selecting the Studies

All records retrieved from the academic databases were imported into EndnoteX9, and duplicates were removed (Bramer et al., 2016). The remaining records were uploaded in Rayyan QCRI (Ouzzani et al., 2016) for independent screening. For Google Scholar and the gray literature sources, articles were screened in the databases. To ensure that the eligibility criteria were sufficiently clear to both reviewers (NP and KM), first a random selection (10%) of the retrieved records was independently screened on titles and abstracts; discrepancies were discussed between NP, KM, and CS. Subsequently, all reports were screened against the eligibility criteria by NP and KM. CS was consulted in the event of any discrepancies. This resulted in an interrater reliability of 90% among the random selection (10%) of the retrieved reports, before consulting discrepancies with CS. Full-text screening was performed by NP, who consulted KM in case of doubt. Furthermore, the reference lists of all included studies were inspected by NP to identify additional eligible studies. If studies were deemed eligible but no access to full-text articles was available, the first author was contacted to request the full-text article.

Studies were eligible for inclusion when burnout among parents of children with CCN was the focus of the study and was measured or observed as a variable in the study. Articles focusing on parents of typically developing children and burnout in contexts other than parenting (i.e., occupational context) were excluded. Furthermore, primary studies employing a qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods approach were eligible for inclusion. We included peer reviewed publications (academic journals and book series) in addition to nonpeer-reviewed publications (such as book chapters). To be eligible, full-texts had to be available and published in English, Dutch, Swedish, Finnish, French, or German.

Charting, collating, and summarizing the data

The data were extracted using Google Forms. The extraction form was pilot-tested several times and adjusted accordingly. NP systematically extracted the data; for any uncertainties KM and CS were consulted. The extracted data were summarized in tables or thematically analyzed per research question by using an open coding strategy. This was done by NP and one project group member assigned per research question.

Stakeholder Consultation

After completing the scoping review, a stakeholder consultation was conducted to investigate what stakeholders considered important insights and gaps after reading the summaries of the extracted data from the literature review. Using the professional network of the project group, a convenience and purposive sample of stakeholders from the Netherlands and Flanders were recruited. Considered as stakeholders were parents of children with CCN, professionals working with families and parents of children with CCN, and researchers with expertise within the field. Stakeholders were included based on their expertise and interest in parents of children with CCN. Despite using the professional network of the project group, independence was guaranteed because the researchers conducting the stakeholder consultation were not familiar to the stakeholders. To promote heterogeneity, we included both parents who identified themselves as having experienced burnout and parents who had not experienced burnout. To prevent interference of participation with recovery from burnout and professional help, participants were excluded if they had (1) received any psychiatric treatment related to burnout in the past six months, (2) were awaiting psychiatric treatment related to burnout, or (3) were suicidal.

KM contacted potential stakeholders, explaining the aim and the process of the consultation and verifying their eligibility. Of the 13 stakeholders approached, 12 expressed interests in participating and were eligible. These stakeholders were sent an information letter and informed consent form. In total, 12 stakeholders participated in the consultation; five parents of children with CCN, two professionals who work with families and parents of children with CCN, one researcher with relevant expertise, two respondents who had dual roles as both parent and a healthcare professional, and two respondents with dual roles as both a researcher and a healthcare professional. The stakeholders with dual roles were asked to reflect on both roles.

Stakeholders were encouraged to participate in the whole stakeholder consultation, consisting of four rounds: one individual interview, two online surveys, and one focus group session. The first round started with reviewing the outcomes from the scoping review, and the following rounds also synthesized the perspectives from stakeholders retrieved in former rounds (see Supplement 1). This process ensured that all stakeholders had equal opportunities to express their thoughts and opinions, avoiding argumentum ad populum. As all stakeholders were from the Netherlands and Flanders, all the rounds were held in Dutch. During the stakeholder consultation, questions were posed regarding stakeholders’ perspectives on the summaries of the research questions from the literature review.

The data from the online surveys were collected through Survalyzer. A topic list was used to guide the interviews and the focus group. The survey and topic lists can be accessed on OSF via https://osf.io/8w6ku/?view_only=f7d39c59a9824ffc904a8b0b0cffff16. All the stakeholders answered the same questions, except for the interview questions that were adapted to the stakeholders’ roles. After each round, reactions of stakeholders were transcribed, summarized, and reviewed by NP and KM and discussed with the project team to guide the next step.

Analysis

The transcripts were analyzed inductively through open coding to identify themes from the stakeholders’ responses (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The synthesis was guided by the fifth research question: what do stakeholders consider important insights and gaps with regard to the outcomes of the data from the review? For this research question NP conducted the analyses and the project members critically examined the analysis. After the final step of the stakeholder consultation, a draft version of the stakeholder consultation was presented to all stakeholders for a member check. After processing their feedback, the text was translated into English and included in the Results section as answer to research question five.

Results

Main Study Characteristics

The literature search resulted in 3629 records. After deduplication, 1843 records remained for screening of titles and abstracts on eligibility. Screening of the records led to the selection of 187 reports for full-text screening. This resulted in 50 unique studies meeting the inclusion criteria. Furthermore, 24 reports were selected for full-text screening from additional databases and backward snowballing. These reports led to seven unique additional studies meeting the inclusion criteria. This resulted in the final inclusion of 57 studies (Fig. 1).

The characteristics of the included studies can be found in Supplementary file 2. Among the quantitative studies, most employed a cross-sectional design (n = 32), followed by an experimental design (n = 10), and a longitudinal design (n = 1). Studies were mostly conducted in Europe (n = 22), the Middle East (n = 19), and North America (n = 9). The rest of the studies were spread across the globe (Asia n = 3, South America n = 2, Africa n = 1, Australia n = 1). The included studies spanned various disciplines, including medical science (n = 17), psychology (n = 13), nursing and caring science or health science (n = 11), educational science or family care (n = 10), psychiatry (n = 4), and psychopharmacology (n = 2). The most common type of respondent were parents, irrespective of gender (n = 31), followed by mothers (n = 17) and primary caregivers (n = 4). Three studies concerned burnout among parents of children with CCN seen from the perspective of clinicians, of which one in combination with parents. In addition, one study investigated burnout among parents of children with CCN from the perspectives of both parents and teachers. Only one study focused on fathers alone. Regarding the children, 36 studies focused on one or two specific conditions of the child, while the rest investigated cross-syndromal CCN. Autism (n = 8) and diabetes (n = 7) were often studied. However, there was a large overlap between the conditions studied. Twenty-four studies focused on parents of children ≤18 years, while eight studies reported on parents of children also >18 years. However, among eight studies, the age range of the children was not specified, and 17 provided no age-related information.

Conceptualization of Burnout

Of the 57 studies, 46 used a predetermined definition of burnout (Supplementary file 2). The thematic analysis of the extracted data from the literature identified three themes related to how burnout was conceptualized. First, burnout was often defined according to symptoms, such as ‘exhaustion’ of an emotional, physical, and/or cognitive nature (n = 24). Second, some described burnout according to its onset factors, such as ‘chronic stress’ (n = 14). Third, at times burnout was described according to its pathogenesis, such as when demands exceeded coping and motivational resources (n = 8). The remaining 11 studies all had a qualitative design and explored the conceptualization of burnout or had a description or a definition of burnout in the Results or the Discussion section of the article. These studies also added to the description of unique caregiving tasks of parents of children with CCN and unique contextual factors, such as having to advocate for adaptations in care and education and dealing with healthcare providers, professionals, and responses from family and friends.

Studies addressed parental demands across domains (i.e., domain-general), such as work and career, partner relationships, and caregiving (i.e., as a consequence directly related to having a child with CCN). As such, many studies used burnout in a broad sense (n = 40), even within the context of parenting a child with CCN. When burnout was framed as pertaining to a specific context (i.e. domain-specific), terms such as, “parental burnout” or “parent burnout” (n = 15), “caregiver burnout” or “caretaker burnout” (n = 3), “diabetes burnout” (n = 1), “maternal burnout” (n = 1), “couple burnout” (n = 1), and “family burnout” (n = 1) were mentioned. In more recent studies, domain-specific terms were more frequently used. However, studies often used different terms for burnout interchangeably (domain-specific and domain-general), without justifying the choice of term(s). Furthermore, five studies used the term “mental burnout” or “emotional burnout” to describe burnout among parents of children with CCN, basing the label of burnout on the manifestation of the symptoms.

Studies often used inventories that could not be traced as distinctly measuring burnout in the context of parenting or caregiving (n = 39). Forty-seven studies used one questionnaire to measure burnout and one study applied two questionnaires to measure burnout. The most common questionnaire used was the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) or a derivative of it (n = 19), followed by the Shirom-Melamed Burnout Questionnaire (SMBQ) (n = 17) and 10 other questionnaires, which were applied ≤3 times. The MBI and SMBQ were not created to specifically operationalize burnout within a parenting context but rather within an occupational context (Maslach et al., 1997; Melamed et al., 1999). Common dimensions used to measure burnout were exhaustion or being fatigued, distancing, lack of accomplishment, and tension. Well-validated questionnaires to measure burnout specifically in the parenting context were used in only two studies (Gérain & Zech, 2018; Sorkkila & Aunola, 2019): the Parental Burnout Inventory (PBI; Roskam et al., 2017), which was derived from the MBI; and the Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA; Roskam et al., 2018), which was based on interviews with five parents suffering from exhaustion. With the focus on the parental context, the PBI and PBA measure dimensions such as exhaustion in the parental role, emotional distancing from the child, and contrast with the previous parental self.

Differences in Burnout Scores between Parents of Children with and without CCN

Nine quantitative studies investigated the differences in burnout scores among parents of children with CCN compared to parents without children with CCN (Table 1). Among these studies, two calculated an overall burnout score, six investigated the differences across dimensions of burnout, and one did both. All the studies showed that, on average, burnout scores among parents of children with CCN were greater than those among parents of children without CCN. This was the case for studies that investigated burnout symptoms in general (measured with the SMBQ or MBI) but also for the study by Gérain and Zech (2018), which was the only study measuring burnout symptoms in the parenting domain (PBI). Additionally, subscale scores were higher for parents of children with CCN, specifically for the dimensions of exhaustion and lack of personal accomplishment, and somewhat less for emotional distancing.

Prevalence

Ten articles investigated the sample prevalence of burnout (see Table 2), hereafter referred to as ‘prevalence’. Half of the studies were conducted in Sweden. To measure burnout, six studies used the SMBQ, three studies used the MBI or a derivative of it, and one study measured a broader concept ‘Carer’s Need Assessment for Schizophrenia’ (CNA-S). The CNA-S covers 18 problem areas, one of which concerns burnout. The prevalence ranged from 20–77% among parents of children with CCN and from 20–34% among parents of children without CCN. However, a clear cutoff point was not always specified. The three studies using a reference sample all used the SMBQ and applied the same cutoff score.

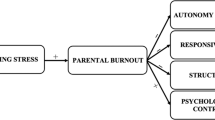

Associated Factors

Forty-five studies investigated factors associated with burnout (see Supplement 2). The majority of these studies employed a quantitative research design (n = 35), followed by a qualitative research design (n = 8), or a mixed method design (n = 2). To gain an overview of the associated factors, the factors were coded according to the Informal Caregiving Integrative Model (ICIM) by Gérain and Zech (2019). Most of the quantitative studies investigated demographic factors, such as age of parent (n = 10), gender of parent (n = 7), age of child (n = 7), level of education of parent (n = 9), or psychological factors, such as parent depression (n = 6) and anxiety (n = 4). Less emphasis was placed on more distal variables, such as social context of the parent indicated by professional support (n = 4) and coping, such as having religious beliefs (n = 2). The quality of the relationship with the child received the least attention (n = 2). The qualitative studies focused on the experiences of parenting children with CCN. Figure 2 shows an overview of the associated factors and the respective numbers of studies per factor according to the ICIM model by Gérain and Zech (2019).

Stakeholders’ Evaluation of Insights and Gaps

Evaluation by the stakeholders of the findings regarding the conceptualization of burnout focused on the theme of choosing a fitting terminology for the construct. No consensus was found on which term would be best. On the one hand, stakeholders emphasized that the parental role and its consequent life-long commitment set apart parental caregiving from caregiving in other roles (such as the role of professionals). Terms such as ‘caregiver burnout’ are not representative of this type of burnout. On the other hand, stakeholders also emphasized that CCN requires forms of caregiving that, both in nature and in extent, are outside of the domain of what is understood to be within the realm of parenting children without CCN, rendering terms such as ‘parenting burnout’ inadequate as well.

In the assessment of the differences in burnout scores between parents of children with CCN and parents of children without CCN, stakeholders emphasized that parents of children with CCN face more difficulties than parents without children with CCN. Three main themes were derived from the reflections of the stakeholders on these differences. The first theme encompassed extra caregiving tasks due to children’s conditions and being exhausted from having to perform physical caregiving tasks. The second theme regarded re-experiencing continued mourning with no foreseeable end (i.e., chronic sorrow; see, e.g., Lindgren et al., 1992). The third theme was the lack of understanding among family members, friends, healthcare professionals or other members of the social circle of parents about what it entailed to be a parent of a child with CCN.

Stakeholders considered the findings on prevalence as validation that parents who experience burnout are not a rare exception. A prominent theme in discussing the prevalence studies was ‘recognition’ and ‘acknowledgment’ of the importance of this topic. Stakeholders speculated about a potential gap between research and awareness by professionals of parents’ struggles. From the perspective of parents, their needs were insufficiently acknowledged and addressed by the outer world. Recognizing the feelings of parents, professionals noted that the fragmented organization of care hampers addressing these needs. Furthermore, the stakeholders emphasized that the prevalence numbers would receive more value if the context of the parents of children with CCN were described. This was reflected through the stakeholders’ interests in the antecedents and the consequences of burnout related to the prevalence of burnout. In addition, stakeholders emphasized the limited number of countries included, the heterogeneity of operationalization, and the uneven attention given to the different conditions that are associated with CCN in the literature.

Most of the extracted factors associated with burnout were recognized by the stakeholders and there was no single overarching factor causing burnout. Rather, they argued for working from the assumption that burnout is caused by combinations and interactions of factors, including the subjective importance assigned by parents to contextual factors. In fact, the inability to prioritize factors was considered a possible risk. Stakeholders also highlighted the importance of both instrumental and emotional support provided through formal and informal social networks. Two important themes were considered conspicuously lacking in the literature. The first theme concerned ‘incidental factors’ and can be seen as ‘the straw that broke the camel’s back’. Parents of children with CCN are in a fragile position, where an additional incident may trigger burnout. The incidental factor does not have to concern the child with CCN, and its impact is highly dependent on individual and situational factors. The second theme concerned the relationship between the parent and the child, which was impacted by several factors, such as the long-term dependence of caregiving tasks on the child, behavioral problems of the child (such as aggression), and the potential lack of reciprocity in the relationship.

Discussion

Considerable variation exists in how studies have conceptualized burnout among parents of children with CCN, with a majority of studies taking a domain-general approach while more recent work is focusing more on domain-specific formulations. Studies converged on parents of children with CCN reporting on average more burnout symptoms compared to parents of children without CCN, with prevalence among parents of children with CCN varying more (20–77%) than among parents of children without CCN (20–34%). While multiple studies in this review used nonspecific inventories for burnout, the recent availability of dedicated inventories tailored to the parenting or caregiver role allows for a more precise measurement approach. As recognized in the stakeholder consultation, the pattern of study findings points toward multifactorial explanatory models of burnout that include subjective meanings, stress accumulation, and interactions between factors instead of a single overarching factor.

Parental burnout in the context of children with CCN appears different from burnout among parents of children without CCN. According to stakeholders, parents of children with CCN often undertake caregiving tasks that surpass traditional notions of parental duties. They emphasized that burnout was not solely attributed to caregiving, but rather to combining parenting and caregiving. As described by Woodgate et al. (2015), parents of children with CCN take on the role of “intense parenting”, acting as a nurse, detective, teacher, and advocate for their child. Hence, the interaction between the demands of parenting and caregiving may disproportionately burden parents of children with CCN. Burnout conceptualizations highlighting this dual role held most relevance and face validity for stakeholders. While parental burnout measures have been validated among parents of children without CCN (Roskam et al., 2017; Roskam et al., 2018), our findings suggest that the conceptualization of parental burnout may be different for parents of children with CCN. Research into the conceptualization of parental caregiving burnout therefore requires inclusion of parental experiences and challenges in the double role of parenting and caregiving.

Although stakeholders perceived the specific context of ’parental caregiving burnout’ as different from parental burnout, symptoms resemble occupational and parental burnout (Mikolajczak et al., 2018). Burnout may spread from one life domain to another (Maslach & Jackson, 1981) and curbing burnout across domains may also benefit parents of children with CCN. Therefore, in addition to research on domain-specific conceptualizations, the broader literature on burnout may also provide relevant insights for parents of children with CCN and clinical practice.

The studies included in this review span various disciplines, with a focus on medical science, psychology, nursing/health science, and educational science/family care. Fewer studies were found within psychiatry and psychopharmacology. A potential explanation is the absence of recognition for burnout as a disorder or medical condition within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), which is widely used as a diagnostic classification system internationally (Nadon et al., 2022). The recent recognition of burnout by the World Health Organization’s 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) offers some acknowledgment, but explicitly emphasizes that burnout should only be applied to an occupational context and not used to describe experiences outside of work-related domains (World Health Organization, 2019). In psychiatry the term “caregiver burden” has been widely utilized to describe the stress faced by caregivers who are responsible for a family member with psychiatric illness (Fadden et al., 1987). Notably, the work by Fadden et al. (1987) has garnered citations across various fields, but within the realm of psychiatry, the articles citing Fadden et al. (1987) predominantly pertain to caregivers experiencing psychiatric conditions, such as depression, a well-established and recognized condition within the DSM-5 (see e.g., El-Tantawy et al., 2010). Greater attention to parental burnout in studies allied to the social disciplines could also be explained by their holistic perspective on health including the well-being of family members in the care for their children. However, additional research on the term “burnout” across disciplines would be needed to explore these possible explanations.

Our study also highlighted the need for further research on associated factors, and the combination and interaction of factors from both the parenting and caregiving context. In alignment with Mroskova et al. (2020), no single factor was identified as the sole cause of burnout in the literature. Stakeholders emphasized that rather than objective factors, the focus should be on subjective factors that determine the burden and parents’ appraisal of having the resources to cope. This is in accordance with the dynamic interplay among risk and resilience factors outlined in the ICIM by Gérain and Zech (2019). However, this model lacks factors that are specific for parenting a child with CCN. As such, future studies should focus on gaining more understanding of the dynamic interplay between subjective experiences and objective risk factors within the context of burnout in parents of children with CCN. This may help raise awareness and attention for the topic and inform tailored interventions to parents’ needs.

The strength of this study lies in its participatory approach. A recent review on the engagement of patient partners in synthesis reviews showed that meaningful involvement enhances the relevance and quality of reviews (Boden et al., 2021). This engagement was further extended by a stakeholder consultation, which enhanced the meaning of the insights taken from the data. However, not all stakeholders were able to partake in the process, and at times, most of them were parents. Furthermore, as the stakeholders were from the Netherlands and Flanders, the cultural context, social expectations of parenting, and attitudes toward children with CCN were limited to the perceptions of those stakeholders who participated in this study. However, the literature reviewed consisted of studies done outside the Netherlands. Another limitation stems from the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced the stakeholder consultation to be conducted online. This may have led to disproportionally including stakeholders with better access to technology. However, online data collection also has logistical benefits, which may limit attrition (Sy et al., 2020). Furthermore, as our search strategy was limited to titles and abstracts, potentially relevant studies may have been missed. However, as we searched for key terms relating to ‘parents’ and ‘burnout’, a broad selection was made of the literature pertaining to burnout among parents of children with CCN. Given that there is no agreed upon definition of burnout among parents of children with CCN, researchers interested in reviewing the literature on parental burnout could look beyond burnout, such as exhaustion and low efficacy. In particular, exhaustion and low efficacy are considered core dimensions of parental burnout (Roskam et al., 2017) and are thus not synonymous with burnout. Furthermore, terminology differed across disciplines. Also, several studies used inventories which have not been specifically designed to measure burnout in parenting or caregiving. Additionally, it remains unclear whether the term “burnout” among parents of children with CCN translates similarly across languages and cultures. None of the studies included in our review compared parents from different cultures. A recent study comparing prevalence of burnout among parents of children without CCN globally suggested that the phenomenon of burnout exists world-wide (Roskam et al., 2021). The majority of the studies in our review were conducted in Europe, the Middle East, and North America, with limited representation from South America, Australia, Africa, and Asia. Caregiving experiences differ among racial and ethnic groups, indicating that cultural relevance and sensitivity of instruments need to be taken into account (Dilworth-Anderson & Gibson, 2002). In a work-related context, discrepancies were found in the interpretation of items of the MBI across countries, even among countries sharing a common linguistic background (Squires et al., 2014). Exploring the cross-cultural and cross-linguistic translation of the term “burnout” within the context of parenting would present an intriguing avenue for future research. Finally, the stakeholder consultation and analysis of the qualitative data could only be performed after study identification, increasing the time gap between the literature search and publication.

Although the exact prevalence of burnout among parents of children with CCN is unknown, parents who experience burnout within this group are far from alone. Societal awareness, especially in general and clinical practice, may be a first step toward alleviating some of the strain that parents experience (Abdoli et al., 2020). Increased societal awareness may also change demands and expectations from professionals or employers. Awareness should also extend to parents themselves. Being aware of risk factors for burnout may not only help parents to recognize signs of burnout and seek assistance but may also prompt professionals to prioritize parental well-being and exhibit heightened vigilance in identifying potential burnout. Awareness may also encourage parents to openly discuss their experiences, which could mitigate potential feelings of being misunderstood or isolated. For both parents and healthcare professionals it would be useful to have an actionable theoretical model explaining risk and resilience factors and consequences of burnout. A model based on data and lived experience can provide insight into the situation of parents and points of reference for support. Such a model may help specify the benefits that may be expected from prevention and early identification, and to investigate how such benefits might be achieved. Building such a model is also urgently needed to formulate the potential benefits of clinical formulation and intervention with respect to parental burnout.

Data availability

The data from the stakeholder consultation are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions but can be shared for verification upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors. The extracted data of the literature can be accessed on Open Science Framework (OSF) through the following link: https://osf.io/j59r8/?view_only=d031984589cd4e6e81f18582d227b79f.

References

Abdoli, S., Vora, A., Smither, B., Roach, A. D., & Vora, A. C. (2020). I don’t have the choice to burnout; experiences of parents of children with type 1 diabetes. Applied Nursing Research, 54, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2020.151317.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

Barreto, T. M., Bento, M. N., Barreto, T. M., Jagersbacher, J. G., Jones, N. S., Lucena, R., & Bandeira, I. D. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and substance-related disorders in parents of children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 62(2), 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14321.

Başaran, A., Karadavut, K. I., Uneri, Ş. O., Balbaloglu, O., & Atasoy, N. (2014). Adherence to home exercise program among caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Turkish Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 60(2), 85–91. https://doi.org/10.5152/tftrd.2014.60973.

Bjornstad, G., Wilkinson, K., Cuffe-Fuller, B., Fitzpatrick, K., Borek, A., Ukoumunne, O. C., Hawton, A., Tarrant, M., Berry, V., Lloyd, J., McDonald, A., Fredlund, M., Rhodes, S., Logan, S., & Morris, C. (2019). Healthy parent carers peer-led group-based health promotion intervention for parent carers of disabled children: Protocol for a feasibility study using a parallel group randomised controlled trial design. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 5, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-019-0517-3.

Boden, C., Edmonds, A. M., Porter, T., Bath, B., Dunn, K., Gerrard, A., Goodridge, D., & Stobart, C. (2021). Patient partners’ perspectives of meaningful engagement in synthesis reviews: A patient-oriented rapid review. Health Expectations, 24(4), 1056–1071. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13279.

Bramer, W. M., Giustini, D., de Jonge, G. B., Holland, L., & Bekhuis, T. (2016). De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 104(3), 240–243. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Cantwell-Bartl, A. M., & Tibballs, J. (2017). Parenting a child at home with hypoplastic left heart syndrome: Experiences of commitment, of stress, and of love. Cardiology in The Young, 27(7), 1341–1348. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951117000270.

Cousino, M. K., & Hazen, R. A. (2013). Parenting stress among caregivers of children with chronic illness: A systematic review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38(8), 809–828. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jst049.

Dilworth-Anderson, P., & Gibson, B. E. (2002). The cultural influence of values, norms, meanings, and perceptions in understanding dementia in ethnic minorities. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 16, S56–S63. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002093-200200002-00005.

Dürüst, Ç. (2018). The comparison of the fatigue of families with children who have normal and different developments (with the help of teachers). Journal for Educators, Teachers and Trainers, 9(2), 24–46.

El-Tantawy, A. M., Raya, Y. M., & Zaki, A. M. K. (2010). Depressive disorders among caregivers od schizophrenic patients in relation to burden of care and perceived stigma. Current Psychiatry, 17(3), 15–25.

Fadden, G., Bebbington, P., & Kuipers, L. (1987). The burden of care: The impact of functional psychiatric illness on patient’s family. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150(3), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.3.285.

Gérain, P., & Zech, E. (2018). Does informal caregiving lead to parental burnout? Comparing parents having (or not) children with mental and physical issues. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00884.

Gérain, P., & Zech, E. (2019). Informal caregiver burnout? Development of a theoretical framework to understand the impact of caregiving. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01748.

Golfenshtein, N., Srulovici, E., & Medoff-Cooper, B. (2015). Investigating parenting stress across pediatric health conditions - A systematic review. Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Nursing, 39(1), 41–79. https://doi.org/10.3109/01460862.2015.1078423.

Hodapp, R. M., Casale, E. G., & Sanderson, K. A. (2019). Parenting children with intellectual diasbilities. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Children and parenting (3ed., Vol 1, pp. 565–596). Routledge.

Hubert, S., & Aujoulat, I. (2018). Parental burnout: When exhausted mothers open up. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01021.

Jaramillo, S., Moreno, S., & Rodríguez, V. (2016). Emotional burden in parents of children with trisomy 21: Descriptive study in a Colombian population. Psychologica, 15(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy15-1.ebpc.

Kurtoğlu, H. H., & Özçirpici, B. (2019). A comparison of family attention and burnout in families of children with disabilities and families of children without disabilities. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Medical Sciences, 39(4), 362–74. https://doi.org/10.5336/medsci.2018-62949.

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(69), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

Lindahl Norberg, A. (2007). Burnout in mothers and fathers of children surviving brain tumour. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 14(2), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-007-9063-x.

Lindahl Norberg, A., Mellgren, K., Winiarski, J., & Forinder, U. (2014). Relationship between problems related to child late effects and parent burnout after pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pediatric Transplantation, 18(3), 302–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/petr.12228.

Lindgren, C. L., Burke, M. L., Hainsworth, M. A., & Eakes, G. G. (1992). Chronic sorrow: A lifespan concept. Scholary Inquiry for Nursing Practice: An International Journal, 6(1), 27–42.

Lindström, C., Åman, J., & Norberg, A. L. (2010). Increased prevalence of burnout symptoms in parents of chronically ill children. Acta Paediatrica, 99(3), 427–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01586.x.

Lindström, C., Aman, J., & Norberg, A. L. (2011). Parental burnout in relation to sociodemographic, psychosocial and personality factors as well as disease duration and glycaemic control in children with Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Acta Paediatrica, 100(7), 1011–1017. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02198.x.

Liu, S., Zhang, L., Yi, J., Liu, S., Li, D., Wu, D., & Yin, H. (2023). The relationship between parenting stress and parental burnout among chinese parents of children with ASD: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05854-y.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behaviour, 2(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1997). The Maslach burnout inventory manual. In C. P. Zalaquett & R. J. Wood (Eds.), Evaluating stress: A book of resources (pp. 191–218). The Scarecrow Press.

McIntyre, S., Novak, I., & Cusick, A. (2010). Consensus research priorities for cerebral palsy: A Delphi survey of consumers, researchers, and clinicians. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 52(3), 270–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03358.x.

McPherson, M., Arango, P., Fox, H., Lauver, C., McManus, M., Newacheck, P. W., Perrin, J. M., Shonkoff, J. P., & Strickland, B. (1998). A new definition of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics, 102(1 Pt 1), 137–140. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.102.1.137.

Melamed, S., Ugarten, U., Shirom, A., Kahana, L., Lerman, Y., & Froom, P. (1999). Chronic burnout, somatic, arousal and elevated salivary cortisol levels. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 46(6), 591–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00007-0.

Mikolajczak, M., & Roskam, I. (2018). A Theoretical and clinical framework for parental burnout: The balance between risks and resources (BR2). Frontiers in psychology, 9, 886 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00886.

Mikolajczak, M., Brianda, M. E., Avalosse, H., & Roskam, I. (2018). Consequences of parental burnout: Its specific effect on child neglect and violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.025.

Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J., Stinglhamber, F., Lindahl Norberg, A., & Roskam, I. (2020). Is parental burnout distinct from job burnout and depressive symptoms? Clinical Psychological Science, 8(4), 673–689. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702620917447.

Mroskova, S., Reľovská, M., & Schlosserová, A. (2020). Burnout in parents of sick children and its risk factors: A literature review. Central European Journal of Nursing and Midwifery, 11(4), 196–206. https://doi.org/10.15452/CEJNM.2020.11.0015.

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(143), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

Nadon, L., De Beer, L. T., & Morin, A. J. S. (2022). Should burnout be conceptualized as a mental disorder? Behavioral Sciences, 12(3), 82 https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12030082.

Nasir, A. M. (2019). Determination of parents burnout for child with type 1 diabetes mellitus in endocrine and diabetes center at Al-Nasiriyah city. Journal of Global Pharma Technology, 11(03), 565–569.

Norberg, A. L., & Forinder, U. (2016). Different aspects of psychological ill health in a national sample of Swedish parents after successful paediatric stem cell transplantation. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 63(6), 1065–1069. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25908.

van Oers, H. A., Haverman, L., Limperg, P. F., van Dijk-Lokkart, E. M., Maurice-Stam, H., & Grootenhuis, M. A. (2014). Anxiety and depression in mothers and fathers of a chronically ill child. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(8), 1993–2002. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1445-8.

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(210), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C., & Khalil, H. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, JBI. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12.

Power, T. G., Dahlquist, L. M., & Pinder, W. (2019). Parenting children with a chronic health condition. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Children and parenting. 3rd ed. (Vol. 1, pp. 597–624). Routledge.

Riva, R., Forinder, U., Arvidson, J., Mellgren, K., Toporski, J., Winiarski, J., & Norberg, A. L. (2014). Patterns of psychological responses in parents of children that underwent stem cell transplantation. Psycho-oncology, 23(11), 1307–1313. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3567.

Roskam, I., Raes, M. E., & Mikolajczak, M. (2017). Exhausted parents: Development and preliminary validation of the parental burnout inventory. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00163.

Roskam, I., Brianda, M. E., & Mikolajczak, M. (2018). A step forward in the conceptualization and measurement of parental burnout: The parental burnout assessment (PBA). Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00758.

Roskam, I., Aguiar, J., Akgun, E., Arikan, G., Artavia, M., Avalosse, H., Aunola, K., Bader, M., Bahati, C., Barham, E. J., Besson, E., Beyers, W., Boujut, E., Brianda, M. E., Brytek-Matera, A., Carbonneau, N., César, F., Chen, B.-B., Dorard, G., & Mikolajczak, M. (2021). Parental burnout around the globe: A 42-country study. Affective Science, 2(1), 58–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-020-00028-4.

Sánchez-Rodríguez, R., Perier, S., Callahan, S., & Séjourné, N. (2019). Revue de la littérature relative au burnout parental [Review of the change in the literature on parental burnout]. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 60(2), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000168.

Sarrionandia-Pena, A. (2019). Effect size of parental burnout on somatic symptoms and sleep disorders. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 88, 111–112. https://doi.org/10.1159/000502467.

Senses Dinc, G., Cop, E., Tos, T., Sari, E., & Senel, S. (2019). Mothers of 0-3-year-old children with Down syndrome: Effects on quality of life. Pediatrics International, 61(9), 865–871. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.13936.

Sorkkila, M., & Aunola, K. (2019). Risk factors for parental burnout among Finnish parents: The role of socially prescribed perfectionism. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 648–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01607-1.

Squires, A., Finlayson, C., Gerchow, L., Cimiotti, J. P., Matthews, A., Schwendimann, R., Griffiths, P., Busse, R., Heinen, M., Brzostek, T., Moreno-Casbas, M. T., Aiken, L. H., & Sermeus, W. (2014). Methodological considerations when translating “burnout. Burnout research, 1(2), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2014.07.001.

Sy, M., O’Leary, N., Nagraj, S., El-Awaisi, A., O’Carroll, V., & Xyrichis, A. (2020). Doing interprofessional research in the COVID-19 era: A discussion paper. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(5), 600–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1791808.

Vereniging van mensen met een lichamelijke handicap. (2018). Onderzoeksagenda kinderrevalidatie Retrieved 21 July 2021 from https://cpnederland.nl/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2020/01/BOSK_Onderzoeksagenda_Kinderrevalidatie_2018_17_Juli_WEB_A4-1.pdf.

Wancata, J., Freidl, M., Krautgartner, M., Friedrich, F., Matschnig, T., Unger, A., Gössler, R., & Frühwald, S. (2008). Gender aspects of parents’ needs of schizophrenia patients. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(12), 968–974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0391-4.

Weiss, M. J. (2002). Hardiness and social support as predictors of stress in mothers of typical children, children with autism, and children with mental retardation. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 6(1), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361302006001009.

Woodgate, R. L., Edwards, M., Ripat, J. D., Borton, B., & Rempel, G. (2015). Intense parenting: A qualitative study detailing the experiences of parenting children with complex care needs. BMC pediatrics, 15, 197 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-015-0514-5.

World Health Organization. (2019). Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Esther van Dinteren for contributing to formulating the research questions. We also thank Simeï Doeleman and Nicole Luitwieler- van den Dries for providing critical feedback throughout the study and Simeï Doeleman for participating in the data collection.

Author Contributions

Nathalie J.S. Pattya contributed to the design and implementation of the research, gathered, interpreted and analyzed the data, drafted and revised the article for critical input. Karen M. van Meeterena,b contributed to the design and implementation of the research, gathered, interpreted and analyzed the data, and revised the article for critical input. Agnes M. Willemena contributed to the design and implementation of the research, gathered, analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted and revised the article for critical input. Marijke A. E. Molc gathered the data and revised the article for critical input. Minke Verdonkb contributed to the design and implementation of the research, analyzed and interpreted the data, and revised the article for critical input. Marjolijn Ketelaard contributed to the design and implementation of the research, analyzed and interpreted the data, and revised the article for critical input.Carlo Schuengela contributed to the design and implementation of the research, gathered, analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted and revised the article for critical input. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. aFaculty of Behavioral and Movement Sciences, Section Clinical and Family Studies, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and Amsterdam Institute of Public Health, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. bStichting OuderInzicht, Zaandam, the Netherlands. cMedical Library, Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. dCenter of Excellence for Rehabilitation Medicine, UMC Utrecht Brain Center, University Medical Center Utrecht, and De Hoogstraat Rehabilitation, Utrecht, the Netherlands

Funding

This study was funded by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (grant number 641001103).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Scientific and Ethical Review Board (VCWE #2020-147) of the Faculty or Behavioral and Movement Sciences, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Patty, N.J.S., van Meeteren, K.M., Willemen, A.M. et al. Understanding Burnout among Parents of Children with Complex Care Needs: A Scoping Review Followed by a Stakeholder Consultation. J Child Fam Stud 33, 1378–1392 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-024-02825-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-024-02825-y