Abstract

There is a need to address the disparities in service use for Latino youth with developmental disabilities and their families. The PUENTE program is a multi-agency service model that utilized an 11-session Promotora-delivered curriculum (Parents Taking Action, Magaña et al., 2017) to promote service utilization among underserved Latino families of youth with developmental disabilities. This study applied two implementation adaptation frameworks (FRAME; Stirman et al., 2019; FRAME-IS; Miller et al., 2021) to elicit feedback from community partners and characterize adaptations for scale up and sustainment. Mixed qualitative and quantitative methods were used to characterize adaptations used and recommended for future use. Promotoras reported adaptations made during the delivery of the intervention via end-of-service surveys for 20 families. Respondents, including Promotoras (n = 5), caregivers (n = 11), and staff (n = 2), were interviewed using semi-structured interviews. Rapid analysis of qualitative data was conducted and integrated with quantitative data to generate and categorize adaptations. Using FRAME and FRAME-IS, adaptations were noted at multiple levels of the program (e.g., content, context, and training). The most common Promotora-reported adaptations were Covering One Topic Across Multiple Sessions (M = 1.65, SD = 1.35) and Adding Content (M = 1.00, SD = 0.86). Additional adaptation themes from the qualitative data, such as the context-level adaptation recommendation of Individualizing for Engagement, converged with the quantitative data. This study builds on a multi-phase, community partnered approach to reducing disparities in access to services for Latino youth with developmental disabilities. These adaptations will be incorporated as part of a large-scale implementation effort to ensure that the program successfully addresses community needs.

Highlights

-

To meet the needs of Latino youth with developmental disabilities and their families, research programs need to center community input.

-

This project utilized a mixed-methods approach to identify community adaptation recommendations to an evidence-based parent intervention.

-

Community-partnered research is required to deliver culturally appropriate care.

-

Community-led adaptations can address the disparities in service use among Latino families of children with developmental disabilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Service Disparities

As the number of Latino* children in the United States continues to grow (Noe-Bustamante, Lopez, & Krogstad, 2020), health inequities among Latino children with developmental disabilities present an increasing concern. For Latino children with autism and/or intellectual disabilities (ID), these health inequities appear in many ways. One significant disparity in the field of health services research is the inequitable rate of health services use for Latino families of youth with developmental disabilities (Magaña et al., 2013; Walensky et al., 2021). Latino families of youth with developmental disabilities report higher unmet service needs (Smith et al., 2020) and lower rates of service utilization of publicly funded services (Magaña et al., 2013; Chlebowski et al. 2018). Identified potential reasons for disparities in service use for Latino youth with developmental disabilities and their families are the lack of information about developmental disabilities provided to Latino families, (Zuckerman et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2022), language barriers for Spanish-speaking families (Povenmire-Kirk et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2020), and lower quality of care (Parish et al., 2012; Shaw et al., 2022). The existing literature emphasizes the critical nature of the disparities present for Latino children with autism and ID and the need for high quality, accessible, culturally informed services to address this gap.

In California, these disparities have been highlighted within the developmental disabilities health services system. Recent analyses have identified significant state-wide disparities in “Purchase of Service” (POS) expenditures from California’s Department of Developmental Services (DDS). Analyses of DDS Purchase of Service administrative data reveal disparities in service use and expenditures for school-age youth (ages 7 to 16) and for people who are racial/ethnic minorities (Harrington & Kang, 2016; Leigh et al., 2016). Specifically, Latino people had the lowest annual service expenditures across diagnosis and age groups compared to other racial and ethnic groups (Leigh et al., 2016).

In response to these identified disparities, the San Diego Regional Center (SDRC), a community-based nonprofit that provides services for Californians with developmental disabilities, leveraged a community-academic partnership with local services and implementation science researchers and community resource centers. SDRC, the Exceptional Family Resource Center, and academic researchers collaborated to identify the unique disparities in the region. This community-academic partnership conducted a needs assessment and found the need for culturally informed service and implementation models for the Latino youth and their families that were being served by SDRC. This led to the creation of the San Diego PUENTE program.

The San Diego PUENTE Pilot Program

The San Diego PUENTE program was initiated by leadership at the San Diego Regional Center (SDRC), one of 21 regional centers in California with a catchment area that includes the urban county of San Diego (30% Latino) and a neighboring rural county, the Imperial Valley (85% Latino). Specifically, the PUENTE (Padres Unidos En Transformación y Empoderamiento, or “Parents United in Transformation and Empowerment”) program was piloted to address known disparities in service utilization among Latino children with autism and/or ID in these two counties. The PUENTE team used a multi-agency service model that utilized a 11-session Promotora-delivered curriculum (Parents Taking Action, Magaña et al., 2017) to promote service utilization among underserved Latino families of youth with developmental disabilities. The pilot PUENTE program occurred between 2017 and 2019 in San Diego and Imperial counties (Magaña et al., 2021). After its initial pilot implementation, the PUENTE team used community-led research to evaluate and refine the service and implementation models.

Adaptations to PUENTE: Framing Community Adaptations Using FRAME and FRAME-IS

Iteratively evaluating and refining culturally informed services is essential for meeting the evolving needs of Latino youth and their families and for gathering valuable insights for dissemination and implementation efforts (Glasgow et al., 2022; Zeng et al., 2022). Existing literature on health services for children has shown that, when delivering evidence-based practices in the community, providers are likely to make adaptations to the curriculum (Cooper et al., 2016; Lau et al., 2017; Stirman et al., 2013). Studies have characterized some of the types of therapist-reported adaptations to EBPs, including tailoring for the clients’ needs, lengthening the session or protocol, and adding or removing components (Stirman et al., 2013; Lau et al., 2017). The Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications-Expanded (FRAME) facilitates the characterization of adaptations made during the process of implementing public health and behavioral health EBPs (Stirman et al., 2019). The Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Evidence-based Implementation Strategies (FRAME-IS) includes additional information on how to document adaptations and modifications specifically related to implementation strategies during the process of implementation (Miller et al., 2021). Both frameworks provided the PUENTE team with a systematic way of tracking and characterizing the modifications made during the implementation process and the adaptation recommendations that would be elicited from the community. The documentation of effective modifications is crucial for identifying beneficial changes that increase engagement from families, serve the needs of the target population, and inform future expansion and sustainment of the PUENTE program.

Current Study

Following the initial pilot implementation of PUENTE, the community-academic partnership team began the evaluation and process improvement of the PUENTE program for sustainment and expansion. The aims of the current study were to apply FRAME and FRAME-IS (Stirman et al., 2019; Miller et al., 2021) to (1) characterize the Promotora-reported adaptations made to both the intervention curriculum and the implementation protocol, and (2) identify future adaptations to systematically incorporate into the PUENTE model. The current study describes the adaptation recommendations identified through community partner feedback that were collected through mixed methods approaches and contextualized within implementation science frameworks.

Methods

Study Context

Data for this mixed-methods analysis were collected in the context of a pilot implementation project of the initial PUENTE program. The pilot was conducted between 2017 and 2019 in San Diego and Imperial counties. A total of six Promotoras (community lay health workers) and caregivers of 34 youth clients participated in the pilot. Data from a subset of participants are included in the current study.

Service model

The PUENTE program team consisted of community partners from non-profit community organizations that provided services for families of children with developmental disabilities and researchers with expertise in children’s mental health services and implementation science. The multi-agency service model was comprised of multiple components including (1) identification and facilitated linkage to program, (2) assessment of service and family needs, (3) Promotora-delivered psychoeducational curriculum and support, (4) communication with Regional Center service coordinators, and (5) mixed qualitative and quantitative evaluations to iteratively adapt and scale the program.

Curriculum

Parents Taking Action (PTA) is a culturally informed, Promotora-delivered psychoeducational intervention that was originally created for Latino mothers of children (ages 2 to 8) with autism (Magaña et al., 2017). It was selected and adapted to focus on youth aged 11 to 16 years of age in collaboration with the primary developer. Adaptations primarily included extending the discussion of developmental stages to include content relevant to adolescence (e.g., adding definitions of “understanding perspective”, “puberty”, and “self-care and independence”) and ensuring examples were appropriate to teenagers (e.g., replacing references to play and toys with technology and conversation). PTA for PUENTE was composed of eleven weekly sessions that were each delivered in one hour, either in the home or remotely via the telephone or videoconferencing. Sessions included psychoeducation content on development (e.g., Understanding Child Development), school advocacy (e.g., How to Be an Effective Advocate), communication and other behaviors (e.g., Creating Everyday Opportunities to Encourage Communication) and mental health (e.g., Stress and Depression).

Delivery

Promotoras were hired from the local community and delivered the PUENTE program to families referred from San Diego Regional Center (Rieth et al., 2020). A “Promotora”, or community health worker, is a member of the community who builds and maintains relationships within their community to promote health education, literacy, and access (Olaniran et al., 2017). Within PUENTE, mothers of youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities who are clients of the Regional Center were recruited, trained, and received performance feedback as they delivered the PTA curriculum in English or Spanish. Promotoras self-reported adherence to the PTA curriculum following each session via a 16-item checklist of key session components. Items included content such as “I gave parent an opportunity to report on the homework assignment” and “I engaged parent in the activities from the manual,” with rating options of, ‘Completed,’ “Did Not Complete,’ or ‘N/A.’ Promotora adherence was uniformly high across sessions, with an average of 85% of items endorsed across sessions (SD = 12%). Additionally, the promotora supervisor completed an observation of adherence for each family for at least 2 of 11 sessions.

Implementation model

The implementation team gathered data on the implementation strategies, adaptations, and outcomes of the PUENTE pilot program. To evaluate the for scale up and sustainment, the PUENTE team gathered Promotora-reported information on adaptations to the existing program via online surveys completed at the end of each family’s participation in the program. To complement this quantitative data, qualitative data were gathered from community partners to inform how the PUENTE program should be adapted to meet the current needs of the community and to prepare for expanding the PUENTE program to other areas of the San Diego and Imperial counties.

Data Collection

Focus groups, interviews, and survey data were collected from individuals involved in delivering or receiving the PUENTE program, including family caregivers who completed the program during the pilot project, Promotoras who delivered the curriculum during the pilot implementation, and staff at the San Diego Regional Center (SDRC) who worked directly in the conceptualization and implementation of the PUENTE program in the community. The protocol for this study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, San Diego.

Promotoras

Promotoras were trained by the Parents Taking Action (PTA) developer and 2nd author. Promotoras were all caregivers or family members of an individual with an intellectual disability, autism, or other developmental disability. Promotoras were members of the local community who had experience navigating the San Diego Regional Center resources and services. Promotoras in this study were all Latina females (n = 5), fluent in Spanish, and had at least a limited working proficiency in English. Promotora data were included if the Promotora had competed the intervention with at least one family and consented to be a part of the focus groups and interviews. All of the Promotoras who served at least one family in the pilot participated except for one Promotora who could not be reached. Data from Promotoras consisted of both qualitative and quantitative methods that gauged project impacts and suggestions for modifications. Quantitative data consisted of the types and frequencies of adaptations that Promotoras reported via the End of Service survey (see Measures) completed at the culmination of the intervention for each family. Qualitative themes for recommended adaptations were gathered from interviews or focus groups.

Caregivers

Caregivers were eligible to participate if they had a child (or children) enrolled in the PUENTE program and if they completed the program during the pilot implementation. Completion was defined as participating in all eleven sessions of the curriculum. Twenty caregivers, all Latinas and self-identified as female, completed the program and were therefore eligible to participate in the focus groups and interviews. Caregivers were invited to participate, and eleven of them consented and were enrolled in focus groups and interviews (n = 11). Caregiver feedback regarding adaptations and recommendations was solicited via individual interviews or focus groups, depending on caregiver availability.

San Diego Regional Center (SDRC) staff

SDRC staff were eligible to participate if they were involved in the development and implementation of the PUENTE program. The staff identified for these interviews were a cultural specialist and a program manager overseeing SDRC services (n = 2). Both staff members consented and agreed to be a part of the interviews. The role of the cultural specialist was to serve as a key consultant and advisor to the PUENTE program. The SDRC program manager was responsible for coordination and supervision of service coordinators at the SDRC Imperial Valley office. These two key SDRC staff completed semi-structured interviews.

Procedure

Promotoras completed an online End of Service Feedback questionnaire for each of the families who they worked with and who completed the intervention (n = 20). Promotoras, caregivers, and SDRC staff members participated in semi-structured interviews and focus groups conducted by the evaluation team staff. The semi-structured interview guides consisted of open-ended questions and probes in both English and Spanish. Both focus groups and individual interviews were utilized for this project. While SDRC staff were interviewed individually, caregivers and Promotoras were assessed in separate focus groups consisting of at least four people. For caregivers or Promotoras who could not attend the focus groups, individual interviews were offered. In total, there were three focus groups (2 for caregivers and 1 for Promotoras) and 5 individual interviews conducted.

Two bilingual, bicultural evaluation team staff attended the interviews and focus groups, with one leading the questions and the other research staff conducting rapid assessment procedures (RAP). The qualitative analyses were conducted via rapid assessment procedures, which reduces the data using templated summaries that align with the themes in the semi-structured interview guides (Scrimshaw & Hurtado, 1989; Miles & Huberman, 1994; Hamilton & Finley, 2019). The two coders (one of whom is the lead author) utilized the recommended team-based approach of open discussion and clarification to arrive at consensus themes (Hamilton & Finley, 2019).

Measures

The End of Service Feedback (EOSF) questionnaire was completed by each Promotora whenever a family with whom they were working completed the PUENTE program. The EOSF was adapted from the Adaptations to Evidence-Based Practices Scale (AES; Lau et al., 2017), a measure that has been used with a large sample of community-based therapists practicing in children’s mental health services (44.6% Latino, 49% Spanish-speaking). The AES was created in line with the Framework for Modification and Adaptations outlined by Stirman and colleagues in the literature (Stirman et al., 2013), the precursor to the FRAME (Stirman et al., 2019). Based on the AES, the EOSF had fourteen items gauging adaptations to treatment and ratings of the helpfulness of intervention components (items in Table 1). Promotoras rated each “helpfulness” item from 1 (not helpful) to 4 (very helpful). For “adaptations” items, Promotoras used a four-point Likert scale (0 = never, 3 = often) to identify how often they made any of these adaptations during the delivery of the PUENTE curriculum to their family.

The PUENTE team created the focus group and interview guides. We used FRAME and FRAME-IS to construct questions on modifications and adaptation recommendations to implement for the sustainment and expansion of the program. The questions on the semi-structured guides inquired about the following three areas of focus: (1) assessing program benefits, (2) understanding barriers and facilitators to program engagement, and (3) gathering strategies and adaptation recommendations for engaging future families. Some examples of adaptation recommendation questions that were in all of the partner guides include, “As we make changes to PUENTE, are there other ways you can think of that PUENTE can help families access services?” and “Is there anything you recommend changing?”.

Data Analytic Plan

FRAME (Stirman et al., 2019) and FRAME-IS (Miller et al., 2021) were used to characterize adaptations and adaptation recommendations gathered from both qualitative and quantitative methods. We applied FRAME (Stirman et al., 2019) to characterize Promotora-reported adaptations to curriculum and community partner adaptation recommendations from the interviews and focus group feedback. Using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 27), descriptive statistics (e.g., frequencies) were used to identify the most commonly reported adaptations. FRAME-IS (Miller et al., 2021) was utilized to characterize adaptation recommendations from the interview and focus group feedback to the service model. Rapid assessment procedure (RAP) has been used to evaluate and rapidly turnaround results to inform improvement and adaptation methods (Harris et al., 1997; Palinkas & Zatzick, 2019). To incorporate the feedback of the community partners in a timely manner, we elected to use RAP to identify themes in the qualitative data for adaptation recommendations. These data were integrated with quantitative data from descriptive statistics to generate additional and/or complementary themes of community-derived adaptations recommendations.

Results

Aim 1—Promotora-Reported Adaptations to the PTA Curriculum (Quantitative)

Using FRAME (Stirman et al., 2019), the adaptations reported by Promotoras after completion of the intervention with each family were characterized as “content” type adaptations (Table 2).

Content

There were 20 EOSF questionnaires completed by 4 Promotoras. Descriptive statistics showed the most common adaptations reported. The most commonly reported adaptations by Promotoras were “Covering One Topic Across Multiple Sessions” (M = 1.65, SD = 1.35) and “Adding Content” (M = 1.00, SD = 0.86) (see Table 1). Within the EOSF questionnaire, Promotoras were also asked to rate the helpfulness of the elements of the PTA curriculum for working with their individual family cases. Promotoras rated the following as the most helpful components: sessions by phone/video (M = 3.85, SD = 0.49), discussing PTA content (M = 3.50, SD = 0.76), and sharing personal experiences (M = 3.45, SD = 0.83). For the least helpful components, Promotoras rated the following: PTA at-home practice (M = 2.65, SD = 0.81), PTA telenovelas/ radionovelas (M = 2.25, SD = 0.72), and PTA printed content (M = 2.70, SD = 0.57) (see Table 1), suggesting the need to reduce these components of the intervention.

Aim 2—Recommendations for Further Adaptations (Qualitative)

Using the FRAME and FRAME-IS, the qualitative adaptation recommendations were characterized by three key types: (1) content, (2) context, and (3) training. Additionally, we included geographic-specific adaptations that were more specific to the different regions of the catchment area of SDRC.

Content

Themes for suggested modifications at the Content level (Table 2) included (1) Further tailoring to meet older developmental level of clients, (2) Further tailoring to fit population needs, and (3) Increased flexibility in modalities of content delivery.

Tailoring curriculum to fit developmental needs of clients

Caregivers, Promotoras, and Staff suggested that the PTA manual and curriculum should be further adapted to reflect the developmental needs of the youth that were being targeted through PUENTE (i.e., ages 11–16). Caregivers, in particular, noted the importance of tailoring the program to be geared more towards adolescents and emerging adults. Promotoras also stated that they believed the PTA curriculum did not focus enough on issues relevant to older children and adolescents (e.g., mental health, treatments for self-injurious behaviors, applying for Social Security Disability Insurance for their children when they become adults). The recommendations from Promotoras and caregivers were to reduce and/or revise content in the curriculum that was still tailored towards families of younger children (e.g., the “Understanding Child Development” session, where families are asked to discuss early developmental phases).

Promotoras and caregivers also requested topics related to transition age youth, such as ways of encouraging self-advocacy and independence. Caregivers requested more curriculum content on how to navigate their child’s self-injurious behaviors and/or injurious behaviors towards others (i.e., kicking, hitting). Caregivers asked for this type of content given that, with puberty in adolescence, many of these behaviors change and there is little support provided for families as they navigate how to keep their child and themselves safe. Another recommendation that arose was the need for a resource that helped Latino parents navigate mental health terminology for their child. The caregivers specifically requested an abbreviation key and glossary for common acronyms used in mental health (i.e., CBT, ABC’s of behavior) that were also relevant to navigating their child’s educational plans (i.e., individualized education plan, or “IEP”).

Need for adaptations to modalities of content delivery

Promotoras and caregivers suggested the need to adapt certain modalities of delivery within the curriculum. There was a broad theme that emerged from both the caregivers and Promotoras about the need for flexibility in delivering the content material. For example, Promotoras noted that they often did not have the families read the material, but instead weaved it in via conversations. Caregivers mentioned this in their recommendations as well, suggesting the benefits of more audio, visual, and video-recorded material to supplement and/or complement the text material.

Promotoras and caregivers both suggested the removal of the radionovelas. These radionovelas were included as supplementary materials with the original PTA manual as part of the didactic teaching of each session to facilitate discussion about specific cultural topics, such as navigating children with developmental disabilities during social gatherings (i.e., during quinceañeras; Magaña et al., 2017). These materials include psychoeducation via audio stories that are modeled after Mexican soap operas. One of these radionovelas includes a segment where a family member “punches someone” and is arrested and deported. Promotoras and caregivers had specific concerns about this segment. Importantly, this conversation occurred after changes in immigration policies and politics at the federal level, changes that contributed to continued experiences of microaggressions, anti-immigrant sentiments, and institutional discrimination (Ayón, 2018). In light of this, Promotoras and caregivers found the inclusion of this event in the story to be unnecessary and offensive and requested for all of the radionovelas to be removed altogether.

A final recommendation within this theme was the modification of the at-home practice, or “homework” assignments after each session in the PTA intervention. Promotoras noted that many families did not complete the homework and that homework could pose a barrier to engagement. Promotoras noted that they often completed the homework assignments with the families while in session instead of in-between sessions (as originally intended). Promotoras and caregivers recommended that the homework be more applied and hands-on (i.e., creating a template for a phone call with the school principle, getting documents ready to apply for SSI) rather than abstract (i.e., answering a reflective question such as “what could you do this week to support yourself and your child?”). Caregivers recommended that homework be offered as either optional between sessions or as part of the material to be completed in session.

Context: Format Level

At the Context: Format level, the recommendation themes were (1) Individualizing for Engagement and (2) Addressing Parental Needs.

Individualizing for engagement in PUENTE

Promotoras and caregivers recommended that the PUENTE process involve options for individualizing for engagement. They suggested the need to offer opportunities for additional family members (e.g., fathers, grandparents) to participate in the PUENTE program. This differs from the current delivery of the program in that PUENTE is delivered to the primary caregiver of the child client of SDRC. Promotoras also suggested that the PUENTE program incorporate ways to clearly establish the expectations and the benefits of engaging in PUENTE as part of the introduction to the intervention. Promotoras and caregivers noted the need for a flexible and more expansive menu of additional information on PUENTE topics, such as additional information on transitioning to adulthood, relevant laws and policies, and content on connecting with other health care services. These additional topics would only be delivered to certain families who mention relevant needs in an attempt not to overwhelm all families with additional information.

Addressing parental needs

The necessity of addressing parents’ needs during the program emerged as a theme. Both caregivers and Promotoras identified that parents had unmet mental health needs that would surface during engagement with PUENTE. In the current model, the approach for connecting parents with mental health supports involved solely providing a list of mental health resources that were available in the geographic area. The respondents suggested systematically identifying mental health concerns during the family’s PUENTE intake assessments to intentionally link the family members with an SDRC service coordinator who would then provide hands-on support for parents. Another recommendation that arose was to create a community for PUENTE caregivers to find support and share resources. While all the respondents (Promotoras, caregivers, and SDRC staff) acknowledged the benefits of receiving information from the Promotoras and SDRC service coordinators, they also acknowledged that many families use services when they hear that other families have benefitted from them. Promotoras, caregivers, and SDRC staff all agreed that building a network of families that could support each other was crucial. Some suggested social media avenues arose, such as WhatsApp text groups, Facebook groups, and/or email groups.

Context: Personnel Level

At the Context level of the Personnel, (i.e., Promotora) themes included (1) Setting Expectations and (2) Recommendations to Increase Engagement.

Setting expectations

Promotoras and caregivers mentioned concerns regarding the term, “Promotora” during the focus groups and interviews. Promotoras themselves noted that they were often referred to as “teachers,” or “guides” instead of “Promotoras”. Caregivers indicate that the word “Promotora” sounded like a marketing term (e.g., promoter), instead of a term that they connected with a service navigator/guide. Caregivers suggested the use of “counselor,” “guide”, or “teacher” instead of “Promotora”.

Recommendations to increase engagement

Promotoras and caregivers had recommendations to facilitate engagement through modifications in the delivery of the PUENTE program to families. One such recommendation was to increase flexibility in the length of the PUENTE sessions. Promotoras and caregivers recommended adapting the length of individual sessions to cover the topics necessary. Sessions could then be covered in up to two-hour periods, versus the original one-hour sessions that were allotted. The longer sessions would then allow the Promotora to connect more fully with the parents on the topic and improve rapport. Another recommendation related to Promotora assignments to families. Both Promotoras and caregivers suggested that, if a family was not engaging in the PUENTE intervention with their current Promotora, the PUENTE Promotora manager should switch the family to another Promotora to allow for a potentially improved personal fit between the parent and Promotora.

Training

At the level of Training (Table 3), the themes included (1) Setting Expectations, (2) Staff Training & Turnover, and (3) Facilitating Service Engagement.

Service expectations

SDRC staff emphasized the importance of ensuring a clear understanding of the PUENTE program’s place within the service landscape at SDRC. Respondents, therefore, recommended setting clear expectations in the training of PUENTE personnel (e.g., implementation team, service coordinators) to clarify the scope, aims, and methods of the program. They also recommended Promotora training include clear definitions of roles within the service model. This would help clearly explain the service landscape and better define differences between service coordinators and Promotoras. While the service coordinators facilitate engagement with SDRC services, the Promotoras deliver the psychoeducation curriculum and encourage their family to utilize the service coordinators for navigation of needed services.

Training & turnover

SDRC staff recommended modifying the training model to improve resource navigation and turnover. One suggestion was for the continuous training of Promotoras regarding the array of services that SDRC offers, including up-to-date information on availability and changes. This was critically important in Imperial Valley, a rural region outside of San Diego, where there is less availability in services and supports compared to San Diego County.

Facilitating service engagement

One recommendation was related to providing parental support. Promotoras recommended providing early feedback to the service coordinator about identified family and parent needs, such as mental health support. Another important and relevant modification included adding technology training support and/or classes for Promotoras to help families specifically in navigating digital spaces. Both Promotoras and caregivers noted that caregivers had a high need for assistance in accessing service information that can be found online or coordinated electronically (e.g., creating an email address, setting up appointments via Zoom, signing online Qualtrics forms).

Geographic-specific adaptations

The adaptation recommendations for this theme were specific to the neighboring rural area, Imperial County (Table 3). Related specifically to training and service engagement in the Imperial Valley region of the SDRC catchment area, all community partners recommended further developing the Promotora team capacity. A main suggestion included incorporating San Diego Promotoras for remote service delivery in the Imperial Valley. These Promotoras would be trained in resources and services available in both the San Diego and Imperial Counties so that they can fully support families from either region.

Discussion

The PUENTE program was initially developed in response to the documented disparities that affect Latino families of youth with developmental disabilities and used a systematic approach to identify disparity reduction targets (age, diagnosis) and to incorporate a Promotora-delivered curriculum into a coordinated service model. In the current evaluation of a pilot implementation, mixed methods were used to characterize adaptations to further refinement PUENTE curriculum and service model for sustainment and expansion. The focus groups and interviews complemented and expanded the quantitative data by explaining why the adaptations were made and which modifications could incorporate into the program to better fit the needs of the population we seek to serve. The data yielded adaptation recommendation themes that applied both to the curriculum, where we used FRAME, and to the service model, where we used FRAME-IS, to capture implementation strategies recommendations.

Implications and Next Steps

We used an iterative, mixed methods approach to characterize adaptations to a community service model developed and implemented through a community-academic partnership. Findings were in line with other adaptations identified in community mental health services. Promotoras, like community mental health therapists, reported lengthening sessions, adding, and removing components to tailor the curriculum for their clients’ needs (Stirman et al., 2013; 2019; Lau et al., 2017). Community partners, including Promotoras, caregivers, and staff, recommended adaptations that would more closely align to the needs of the community. In summary, our findings underscore the vital significance of adaptability in community service models, as it enables us to effectively address the ever-changing needs and nuances of the populations we serve.

This study adds to the growing research on PTA adaptations. Other groups have adapted Parents Taking Action (PTA) curriculum for Chinese, Colombian, and Black families (Dababnah et al., 2022; Magaña et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2022). Comparison among these adaptations has highlighted the shared process of engaging key community partners at all stages to inform needs, shape the content and form of the intervention, and iteratively adapt materials. Similarly, all adaptations have retained the key features of the use of peer leaders, content on reducing stress among caregivers, utilizing plain language and clear explanations of topics, incorporation of visuals, and interactive discussions between parents and Promotoras each session (Magaña et al., 2021). Research on these cultural adaptations also suggested the need to adapt the PTA program further for cultural and population-specific needs, such as adjusting content per individual family and involving additional parent peer support (Dababnah et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2022).

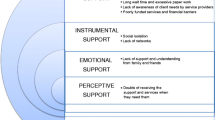

Community-partnered research necessitates a dynamic and collaborative approach. Our PUENTE team recently incorporated the adaptations reported in this manuscript and presented them to partners for accessibility, feasibility, and acceptability through a series of “working groups” (see Fig. 1). This effort consisted of virtual meetings where SDRC staff, Promotoras, caregivers, and evaluation staff discussed various issues that arose from the implementation of the adaptations. An example of an important issue that was addressed through these working groups arose when the implementation team suggested the use of a video from an Autistic self-advocate who, while discussing self-advocacy, also mentioned that they identified as part of the LGBTQ+ community. Caregivers in our working groups did not agree with the addition of this video because it addressed sexual and gender minority topics that did not align with their cultural values. Our research team considered keeping the video since existing literature has documented the harmful effects of stigma and lack of familial support on Latino individuals who are a part of sexual and gender minority groups, effects ranging from health complications to psychological stress (Velez et al. (2015); Li et al., 2019). In line with our community-partnered approach, which emphasized the importance of centering community values and voices, our research team ultimately decided to remove the video from the proposed adaptations. Given that recent research has found that autistic individuals who identify as LGBTQ+ report higher level of unmet healthcare needs (Hall et al., 2020), future studies should seek to focus specifically on this important intersectional topic of conversation and providing education around sexuality and sexual orientation to parents of sexual and gender minority Latino youth with developmental disabilities.

The working groups also served to navigate a concern regarding the word “Promotora”. Promotoras have been largely studied in the literature and shown to have the potential to impact the health of many communities (Waitzkin, et al., 2011; Stacciarini et al., 2012; Lohr et al., 2018), including Latinos (Lujan et al., 2007; Magaña et al., 2020; Cáceres et al., 2022). However, some Promotoras and caregivers had noted that the word caused confusion within the community since it was more closely related to marketing (i.e., promoter who promotes a product or service) than to service navigation and peer support. Other Promotoras, caregiver partners, and the research team believed that the term connects the PUENTE program to the larger public health approach involving community lay-health workers that support health and service initiatives. Additionally, during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the designation of the Promotora or community lay-health worker was able to be utilized by our Promotoras to attain early access to vaccines. Therefore, the PUENTE team decided to keep the term while also adding more psychoeducation on the definition and roles of the “Promotora” for both the Promotoras themselves and the caregivers. The research team’s decision to retain and redefine the term “Promotora” not only addresses immediate concerns but also underscores the broader implications of harnessing the power of community lay-health workers as a valuable resource in advancing public health initiatives, particularly in times of crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, with the potential to positively impact communities on a larger scale.

The description and characterization of community-derived adaptations to the targeted service program using FRAME and FRAME-IS will allow us to systematically sustain and expand this culturally tailored intervention. The expanded delivery of a tailored PUENTE program aims to empower and equip Latino families to increase their service utilization, thus ultimately decreasing the disparities between Latino and non-Latino White populations.

The description and characterization of community-derived adaptations to the targeted service program using FRAME and FRAME-IS not only enables the systematic sustainment and expansion of this culturally tailored intervention but also holds the potential for broader implications in the realm of healthcare equity. By scaling up the delivery of the tailored PUENTE program and disseminating information on how to conduct community-led, iterative adaptations, we aspire to not only empower Latino families of children with autism and/or intellectual disabilities to increase their service utilization but also to contribute to a larger goal of reducing healthcare inequities that have impacted Latino communities.

Limitations

There were important limitations within this program evaluation and expansion approach. One such limitation was that the quantitative data were only collected from the Promotoras after they had a family complete the PUENTE program. It is important to categorize adaptations made to the intervention even when a family does not complete services, as this might help us further determine the effects of Promotora-led adaptations on retention and engagement in services. This questionnaire, the EOSF, was only completed once at the end of treatment, limiting the amount of information that we gathered on more frequent adaptations. Additionally, the EOSF was adapted from the AES (Lau et al., 2017), but has not been tested and validated for use with Promotoras.

Future research should consider incorporating more methods of gauging Promotora-led adaptations at a frequency that does not burden providers but gathers information about instances of adaptations throughout the intervention. The small sample sizes were a limitation of this study. While the small sample did deliver saturation of recommendations and themes, a larger sample would be ideal in ensuring additional generalizability of adaptation recommendations. This is especially true of the SDRC key staff members. For the pilot program, only a few members of SDRC were extensively involved in the implementation protocol. In the next iteration of the PUENTE program, it may be beneficial to gather perspectives from additional staff members involved in any capacity. Service Coordinators (SCs), who manage family cases in SDRC, were not initially included as key staff members. Because SCs refer families to the PUENTE program and are also the connection between family and SDRC services, this group is necessary to include in future community collaborator feedback.

Conclusions

The goal of this project was to utilize an iterative, mixed-methods approach to identify community-led adaptation recommendations to a Promotora-delivered parent psychoeducation intervention for Latino parents of youth with developmental disabilities. This project is an example of the value of evaluating community implementation of new programs to advance research on adaptations.

References

Ayón, C. (2018). Unpacking immigrant health: Policy, stress, and demographics. Race and Social Problems, 10(3), 171–173. https://doi-org.libproxy.sdsu.edu/10.1007/s12552-018-9243-3.

Cáceres, N. A., Shirazipour, C. H., Herrera, E., Figueiredo, J. C., & Salvy, S. J. (2022). Exploring Latino Promotores/a de Salud (Community Health Workers) knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of COVID-19 vaccines. SSM-Qualitative Research in Health, 2, 100033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2021.100033.

Chlebowski, C., Magaña, S., Wright, B., & Brookman-Frazee, L. (2018). Implementing an intervention to address challenging behaviors for autism spectrum disorder in publicly-funded mental health services: Therapist and parent perceptions of delivery with Latinx families. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 24(4), 552–563. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000215.

Cooper, B. R., Shrestha, G., Hyman, L., & Hill, L. (2016). Adaptations in a Community-Based Family Intervention: Replication of Two Coding Schemes. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 37(1), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-015-0413-4.

Dababnah, S., Kim, I., Magaña, S., & Zhu, Y. (2022). Parents taking action adapted to parents of Black autistic children: Pilot results. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12423.

Glasgow, R. E., Battaglia, C., McCreight, M., Ayele, R., Maw, A. M., Fort, M. P., & Rabin, B. A. (2022). Use of the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance (RE-AIM) framework to guide iterative adaptations: applications, lessons learned, and future directions. Frontiers in Health Services, 2, 959565. https://doi.org/10.3389/frhs.2022.959565.

Hall, J. P., Batza, K., Streed, C. G., Boyd, B. A., & Kurth, N. K. (2020). Health disparities among sexual and gender minorities with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50, 3071–3077. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04399-2.

Hamilton, A. B., & Finley, E. P. (2019). Qualitative methods in implementation research: An introduction. Psychiatry Research, 280, 112516.

Harrington, C., & Kang, T. (2016). Disparities in service use and expenditures for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities in California in 2005 and 2013. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 54(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-54.1.1.

Harris, K., Jerome, N., & Fawcett, S. B. (1997). Rapid assessment procedures: a review and critique. Human Organization, 56, 375–378. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.56.3.w525025611458003.

Lau, A., Barnett, M., Stadnick, N., Saifan, D., Regan, J., Wiltsey Stirman, S., Roesch, S., & Brookman-Frazee, L. (2017). Therapist report of adaptations to delivery of evidence-based practices within a system-driven reform of publicly funded childrens mental health services. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(7), 664–675. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000215.

Leigh, J., Grosse, S. D., Cassady, D., Melnikow, J., & Hertz-Picciotto, I. (2016). Spending by California’s Department of developmental services for persons with autism across demographic and expenditure categories. PLoS One, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0151970.

Li, M. J., DiStefano, A. S., Thing, J. P., Black, D. S., Simpson, K., Unger, J. B., Milam, J., Contreras, R., & Bluthenthal, R. N. (2019). Seeking refuge in the present moment: A qualitatively refined model of dispositional mindfulness, minority stress, and psychosocial health among Latino/a sexual minorities and their families. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(4), 408–419. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000338.

Lohr, A. M., Ingram, M., Nuñez, A. V., Reinschmidt, K. M., & Carvajal, S. C. (2018). Community–clinical linkages with community health workers in the United States: a scoping review. Health Promotion Practice, 19(3), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839918754868.

Lujan, J., Ostwald, S. K., & Ortiz, M. (2007). Promotora diabetes intervention for Mexican Americans. The Diabetes Educator, 33(4), 660–670. https://doi.org/10.1177/01457217073040.

Magaña, S., Dababnah, S., Xu, Y., Torres, M. G., Rieth, S. R., Corsello, C., ... & Vanegas, S. B. (2021). Cultural adaptations of a parent training program for families of children with ASD/IDD: Parents taking action. In International Review of Research in Developmental Disabilities (Vol. 61, pp. 263–300). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.irrdd.2021.07.005.

Magaña, S., Heydarian, N., & Vanegas, S. (2022). Disparities in healthcare access and outcomes among racial and ethnic minoritized people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.013.288.

Magaña, S., Lopez, K., Aguinaga, A., & Morton, H. (2013). Access to diagnosis and treatment services among latino children with autism spectrum disorders. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51(3), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-51.3.141.

Magaña, S., Lopez, K., & Machalicek, W. (2017). Parents Taking Action: A psycho-educational intervention for latino parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Family Process, 56(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12169.

Magaña, S., Lopez, K., Salkas, K., Iland, E., Morales, M. A., Garcia Torres, M., Zeng, W., & Machalicek, W. (2020). A randomized waitlist-control group study of a culturally tailored parent education intervention for latino parents of children with asd. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(1), 250–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04252-1. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-50.4.287.

Magaña, S., Tejero Hughes, M., Salkas, K., Gonzales, W., Núñez, G., Morales, M., Garcia Torres, M., & Moreno-Angarita, M. (2021). Implementing a Parent Education Intervention in Colombia: Assessing Parent Outcomes and Perceptions Across Delivery Modes. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 36(3), 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357620986947.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage.

Miller, C. J., Barnett, M. L., Baumann, A. A., Gutner, C. A., & Wiltsey-Stirman, S. (2021). The FRAME-IS: a framework for documenting modifications to implementation strategies in healthcare. Implementation Science, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-021-01105-3.

Noe-Bustamante, L., Lopez, M. H., & Krogstad, J. M. (2020). US Hispanic population surpassed 60 million in 2019, but growth has slowed. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/813317/us/1686853/.

Olaniran, A., Smith, H., Unkels, R., Bar-Zeev, S., & van den Broek, N. (2017). Who is a community health worker? - a systematic review of definitions. Global Health Action, 10(1), 1272223 https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2017.1272223.

Palinkas, L. A., & Zatzick, D. (2019). Rapid assessment procedure informed clinical ethnography (rapice) in pragmatic clinical trials of mental health services implementation: methods and applied case study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 46(2), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-018-0909-3.

Parish, S., Magana, S., Rose, R., Timberlake, M., & Swaine, J. G. (2012). Health care of latino children with autism and other developmental disabilities: Quality of provider interaction mediates utilization. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117(4), 304–315. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-117.4.304.

Povenmire-Kirk, T. C., Lindstrom, L., & Bullis, M. (2010). De escuela a la vida adulta/from school to adult life: Transition needs for Latino youth with disabilities and their families. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 33(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885728809359004.

Rieth, S., Dickson, K., Zaragoza, R., Storman, D., Plotkin, R., Orahovats, C., & Brookman-Frazee, L. (2020, June). Development and Evaluation of the “PUENTE” Promotora Model to Reduce Ethnic Disparities in Developmental Disability Service Utilization. Paper accepted to the International Society for Autism Research Annual Meeting, Online Conference.

Scrimshaw, S. C. M., & Hurtado, E. (1989). Rapid assessment procedures for nutrition and primary health care: Anthropological approaches to improving programme effectiveness. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center.

Shaw, K. A., McArthur, D., Hughes, M. M., Bakian, A. V., Lee, L. C., Pettygrove, S., & Maenner, M. J. (2022). Progress and disparities in early identification of autism spectrum disorder: Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 2002-2016. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(7), 905–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.11.019.

Smith, K. A., Gehricke, J. G., Iadarola, S., Wolfe, A., & Kuhlthau, K. A. (2020). Disparities in service use among children with autism: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 145(Supplement_1), S35–S46. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-1895G.

Stacciarini, J. M. R., Rosa, A., Ortiz, M., Munari, D. B., Uicab, G., & Balam, M. (2012). “Promotoras” in Mental Health: A Review of English, Spanish, and Portuguese Literature. Family and Community Health, 92–102. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/44953448.pdf.

Stirman, S. W., Miller, C. J., Toder, K., & Calloway, A. (2013). Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implementation Science, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-65.

Stirman, S. W., Baumann, A. A., & Miller, C. J. (2019). The FRAME: An expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implementation Science, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0898-y.

Velez, B. L., Moradi, B., & Deblaere, C. (2015). Multiple oppressions and the mental health of sexual minority Latina/o Individuals. The Counseling Psychologist, 43(1), 7–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000014542836.

Waitzkin, H., Getrich, C., Heying, S., Rodríguez, L., Parmar, A., Willging, C., & Santos, R. (2011). Promotoras as mental health practitioners in primary care: a multi-method study of an intervention to address contextual sources of depression. Journal of Community Health, 36, 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-010-9313-y.

Walensky, R. P., Bunnell, R., Layden, J., Kent, C. K., Gottardy, A. J., Leahy, M. A., Martinroe, J. C., Spriggs, S. R., Yang, T., Doan, Q. M., King, P. H., Starr, T. M., Yang, M., Jones, T. F., Timothy Jones, C. F., Matthew Boulton, C. L., Carolyn Brooks, M., Jay Butler, M. C., Caine, V. A., … Yang, W. (2021). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years-Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018 Surveillance Summaries Centers for Disease Control and Prevention MMWR Editorial and Production Staff (Serials) MMWR Editorial Board. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/ss/ss7011a1.htm.

Xu, Y., Chen, F., Mirza, M., & Magaña, S. (2022). Culturally adapting a parent psychoeducational intervention for Chinese immigrant families of young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12432.

Zeng, W., Magaña, S., Lopez, K., Xu, Y., & Marroquín, J. M. (2022). Revisiting an RCT study of a parent education program for Latinx parents in the United States: Are treatment effects maintained over time. Autism, 26(2), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211033108.

Zuckerman, K. E., Lindly, O. J., Reyes, N. M., Chavez, A. E., Macias, K., Smith, K. N., & Reynolds, A. (2017). Disparities in diagnosis and treatment of autism in Latino and non-Latino White families. Pediatrics, 139(5). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Elizabeth Rangel is the primary author and participated in the conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, manuscript writing of the original draft and revision. Sarah Rieth participated in the conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, and writing review and editing. Yesenia Mejia participated in the conceptualization, writing review and editing. Laura Cervantes participated in the conceptualization, management and coordination responsibility for the research activity planning and execution, writing review and editing. Brenda Bello Vazquez participated in the conceptualization, funding acquisition, management and coordination responsibility for the research activity planning and execution, writing review and editing. Lauren Brookman-Frazee is the senior author and led the conceptualization, investigation, methodology, writing review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

*We used the term Latino to encompass the racial/ethnic population within this study. Our community partners preferred the use of this term versus other terms that have been utilized in the literature (Latinx/e).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rangel, E., Rieth, S., Mejia, Y. et al. Community-Led Adaptations of a Promotora-Delivered Intervention for Latino Families of Youth with Developmental Disabilities. J Child Fam Stud 33, 1238–1250 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-024-02816-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-024-02816-z