Abstract

Recent developments in society, together with an increase in the number of far-right motivated crimes in Germany, suggest that far right-wing attitudes are becoming increasingly popular within public opinion. Since political attitudes are shaped within the family and peer setting during the adolescent stage, assessing the potential interplay of family and peer relationships with regard to such attitudes appears essential. The present study aims to explore (1) the relationship between perceived parental far right-wing attitudes, as reported by adolescents, and adolescents’ self-reported far right-wing attitudes, as well as (2) the unique and moderating effects of variables related to the contact hypothesis (ethnic minority friends and exposure to ethnic minority group members in the social environment). Using data from a representative school survey of seventh and ninth grade German adolescents, multilevel linear regression models indicated a statistically significant positive association between adolescent-reported parental far right-wing attitudes and adolescents’ far right-wing attitudes. Furthermore, the analyses demonstrated a small but statistically significant moderating effect of friendship with individuals of an ethnic minority: the relationship between parental and adolescent far right-wing attitudes was weaker for adolescents who had more ethnic minority friends. Thus, adolescents who were friends with individuals of an ethnic minority appeared to be less congruent with their parents’ far right-wing attitudes, compared to adolescents without any ethnic minority friends. In contrast, the overall level of exposure to ethnic minority group members in the social environment did not affect the strength of the relationship between perceived parental and adolescent far right-wing attitudes.

Highlights

-

Parent-adolescent similarity of far right-wing attitudes and effects of ethnic minority contact among German adolescents.

-

We found a significant positive association between adolescent-reported parental and adolescents’ far right-wing attitudes.

-

Results show a unique moderating effect of intergroup friendship on parent-adolescent similarity of far right-wing attitudes.

-

Recommendations include the development of further educational initiatives that target the facilitation of intergroup friendship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Many democratic societies are facing challenges due to the growing polarization and radicalization of right-wing milieus (Heller et al., 2020). Right-wing extremism can be defined as a “pattern of attitudes whose unifying characteristics are notions of inequality” (Kreis, 2007, p.12), which relate to various forms of nationalistic, xenophobic, and anti-Semitic ideologies (Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, 2019). Forms of right-wing extremism are dominated by the belief that an individual’s value as a human being is dependent upon their membership of a specific ethnicity, nation, or race (Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, 2019). Radical right-wing parties and movements have made their mark in numerous European countries in recent years. Such increases are not limited to the political level, as they have also been observed with regard to right-wing extremist terrorist attacks. The Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP, 2019) recorded a 320% increase in far-right terrorist attacks from 2014 to 2019 in Western Europe, North America, and Oceania. When comparing the extreme right in different (European) countries, a number of similarities emerge, but in many respects their sub-movements differ significantly (for similarities and differences of the extreme right in Europe, see Melzer & Serafin, 2013; Zick et al., 2011).

The present study focused on the situation in Germany, the country with the highest number of right-wing terrorist attacks between the years of 1990 and 2021 in Western Europe (Ravndal et al., 2022). Contemporary developments in Germany, including the detection of the right-wing terrorist group ‘NSU’ (i.e., National Socialist Underground) in 2011 (see Koehler, 2014), the establishment of the Islamophobic group ‘Pegida’ (i.e., Patriotic Europeans against the Islamization of the West) in 2014, and the rise of the new right-wing party “Alternative for Germany” (see Krieg & Kliem, 2019), suggest that extreme right-wing attitudes are once again gaining popularity within public opinion. The 2018 violent riots at a far-right demonstration in Chemnitz (ARD, 2019), as well as the right-wing motivated attacks in Halle and Hanau (see BBC, 2020), further highlight the current extent of right-wing extremism in Germany. Official statistics showed a steady increase in right-wing motivated offenses in Germany, with a record total of 23,604 such offenses in 2020 (Bundeskriminalamt, 2021). Based on the historical past of national socialism in Germany, it is arguable that the risk of diminishing democratic cohesion is especially pertinent to the liberal and pluralist society of Germany.

Far right-wing attitudes (FRWA) generally include the rejection of a democratic constitutional state, including its core rules and values, which thereby questions or negates the fundamental principle of human equality (Kailitz, 2004). Empirical evidence has demonstrated that anti-democratic, FRWA have long been established not only in political parties and movements, but also within the general German population (e.g., Decker et al., 2016). Alarmingly, this also applies to the age group of adolescents, where FRWA have been further associated with the perpetration of right-wing motivated violent and non-violent crimes (Krieg & Kliem, 2019). This relationship remained stable even after accounting for various theoretically driven risk factors of right-wing extremism such as deprivation, victimization, empathy, affinity for violence, or factors related to the disintegration, attachment, and self-control theories (Baier et al., 2016; Krieg & Kliem, 2019). It must be noted that the adoption of FRWA is not related to the perpetration of right-wing motivated crime in a deterministic manner; rather, FRWA can be defined as potentials for action and behavior (Stöss, 2010). When considering the connection between the adoption of FRWA and the perpetration of right-wing motivated crime, it is also important to point out the different degrees of politicization of the various offenders. Strongly ideologized individuals, for whom violence serves as a function of the ideology (Sitzer & Heitmeyer, 2007), must be distinguished from those who are, in the first instance, generally willing to commit violent acts and then justify these on the basis of right-wing ideologies (Heitmeyer, 1994). For the second type of offenders, it is a general willingness to use violence that legitimizes the commission of crimes through the adoption of far right-wing ideological attitudes (Heitmeyer, 1994; Krüger, 2008; Maresch & Bliesener, 2015).

Adolescence constitutes a formative phase in life where key democratic attitudes and beliefs about society are formed (Jaschke, 2012; Rekker et al., 2015) and individuals begin to engage with political themes (Eckstein, 2018). It is therefore essential to investigate the potential origins and correlates of FRWA during this stage of development. Basic political orientations are assumed to be significantly shaped by the family and peer group as key socializing agents (Degner & Dalege, 2013; Eckstein, 2018; Schmid, 2008), and were found to remain relatively stable for approximately two decades (Fend, 2009). A wealth of theoretical and empirical research has established the role of parental socialization in developing political attitudes and orientations in adolescents (Boonen, 2019; Meeusen & Boonen, 2020), although limited studies have focused on outcomes related to the extreme right (Avdeenko & Siedler, 2017). The theoretical framework underlying the attitudinal similarities established in such studies is historically rooted in the cultural transmission theory (see Tedin, 1974). Although genetic inheritance has been brought forward as a mechanism accounting for the parent-adolescent similarity in political attitudes and orientations (e.g., Hatemi et al., 2014), the current study examined the parent-adolescent similarities of FRWA from a purely behavioral perspective. To our knowledge, FRWA correlations between adolescents and their parents have not yet been empirically studied in adolescent samples. Besides the family, peers form another important influence on the formation of the adolescent political personality (see Ojeda & Hatemi, 2015). Previous literature has operationalized the term ‘peers’ in various ways, including references to adolescents’ best/closest friends (Kobus, 2003) and others perceived as equals in terms of characteristics such as age, educational level, and background (Reber & Reber, 2001). Any use of the term ‘peers’ within the present study thus refers to both the adolescent’s ethnic minority friends as well as their exposure to ethnic minority group members. In line with Allport’s (1954) contact hypothesis, friendship with a foreign national (Fuchs, 2003) and positive intergroup contact (Beelmann & Heinemann, 2014) have been associated with FRWA.

When considering parental and peer influences in conjunction with one another, it is possible that intergroup peer experiences lead adolescents to rely less on parental views and more on their own experiences, which may affect the association between parental and adolescent FRWA. We are unaware of any recent empirical study that has assessed both parent-adolescent similarities in FRWA and the potentially modifying role of (direct and indirect) contact with individuals belonging to an ethnic minority. To date, there is little knowledge about the interplay of parental political socialization and peer influences in shaping extremist political attitudes among adolescents. Analyzing the interconnectedness of parental and peer influences allows for a clearer picture of how several socializing forces may simultaneously affect the process of political attitude formation during adolescence.

Combining the theoretical underpinnings of the cultural transmission theory and the contact hypothesis, the present study aimed to (1) analyze the extent of association between adolescents and their parents in FRWA, and (2) assess whether factors related to the contact hypothesis (friendship with individuals belonging to an ethnic minority and overall school-level exposure to ethnic minorities) affected the strength of this relationship. More specifically, we explored whether adolescent FRWA could be moderated by personal experiences as these may have caused adolescents to question the political beliefs they had potentially adopted from their parents. To assess the potential moderating effect of ethnic minority contact, we tested whether adolescent-reported parental FRWA were differentially related to adolescents’ FRWA, depending on adolescents’ reporting of friendship with individuals belonging to an ethnic minority, as well as the adolescents’ overall exposure to ethnic minority group members in their social environment.

Theoretical and Empirical State of Research

Parent-Adolescent Similarity of Political Attitudes

Cultural transmission theory

As adolescents develop, they form their own political identity based on influences within their immediate environment. The literature on cultural transmission of norms, preferences, and beliefs (e.g., Bisin & Verdier, 2001) has suggested that parents – either intentionally or unintentionally – pass on their attitudes to their children, resulting in similarities of orientations and attitudes (e.g., Adriani & Sonderegger, 2009; Meeusen & Boonen, 2020, Tedin, 1974). The theoretical mechanism of cultural transmission strongly builds on social learning theory (see Bandura, 1969), according to which parents shape their children’s orientations through role modeling and that adoption of parental attitudes follows a process of observational learning. Later research has found that a higher frequency of clear, consistent, and stable cues displayed by parents increased the likelihood of successful attitude transmission (Boonen, 2019; Kinder & Kam, 2010). This model is based on the implicit assumption that parents largely drive their children’s learning processes, who are aware of and willing to adopt their parents’ attitudes (Marcia, 1980; Ojeda & Hatemi, 2015).

A second theoretical pathway refers to processes of status inheritance (e.g., Glass et al., 1986), whereby parents differentially exposed their children to social milieu factors, such as the ideological climate of the surrounding environment, which affected political orientations (Rico & Jennings, 2016). Most empirical studies conducted so far assumed a ‘direct transmission’ of parental attitudes and orientations to their offspring (e.g., Hooghe & Boonen, 2015; Rico & Jennings, 2016). The theoretical mechanism of cultural transmission has been consistently demonstrated in the form of a positive and statistically significant association between parental and offspring political orientations (Rico & Jennings, 2016), as well as far right-wing party preferences (Avdeenko & Siedler, 2017; Fend, 2009) and attitudes toward immigration (Degner & Dalege, 2013).

The perception-adoption approach

Some recent studies have challenged the general view that adolescents tend to uniformly internalize and replicate their parents’ political attitudes, and the assumption that such political orientations are reliably and directly transmitted from parents in a top-down fashion. Instead, these studies assumed a more qualified view on the microprocesses of socialization within the family while stressing child agency (Hatemi & Ojeda, 2021; Meeusen & Boonen, 2020). One central assumption within the perception-adoption approach is that this similarity of political attitudes is mediated through the child or adolescent’s perception of parental attitudes. For example, Hatemi & Ojeda (2021) found that the perception of parental values was the decisive factor within the adoption of political values, rather than the true political orientation parents held. In this process, individuals selectively and differentially processed parental information. In their research on the transmission of party identification using data from two family-based studies, Hatermi and Ojeda (2021) reported that children differentially learned and chose to adopt their parents’ preferences. Furthermore, Gabriel (2007) found that while parental political views tended to coincide with those of adolescents, the political topics discussed within adolescents’ social environments were often subject to appropriation and radicalization by adolescents. These findings highlight the deceptive simplicity of the transmission process since adolescents may interpret their parents’ borderline right-wing beliefs to be stronger than they truly are, thus referring to inaccurate parental beliefs as political guidance.

Finally, Gniewosz and Noack (2006) noted that projective processes (i.e., the projection of one’s own beliefs onto others) played an important role in the subjective interpretation of parental attitudes. The authors showed greater correlations between adolescents’ political attitudes and the perceptions of their parents’ political attitudes (projection), in comparison to the parents’ actual political attitudes (transmission), which may be explained by the tendency to assume consensus if the true belief or position of the person being assessed is unknown (Clement & Krueger, 2000). The present study followed the theoretical underpinnings of the cultural transmission theory, whilst recognizing the role of projective processes in the context of the perception-adoption approach.

Ethnic Minority Contact

Peer influences

Peer influences also play a central role in the political orientations of (early) adolescents. As Ojeda and Hatemi (2015) noted, the perception-adoption model can be extended to the wider social ecology, which includes peer groups. Here, peer influences may lead adolescents to be exposed to either similar or alternative cues relative to parental attitudes. While peer groups offer a form of group identity associated with the desire for acceptance and pressure to conform, selection processes are likely to be at work which make individuals “gravitate toward groups that hold beliefs similar to their own to minimize conflict and reinforce their own values” (Ojeda & Hatemi, 2015, p. 1153). Peer norms and orientations are likely to operate not only among self-chosen friends, but also among involuntarily created peer groups encountered in schools, neighborhoods, or extracurricular activity groups (Barth et al., 2004; Müller et al., 2016).

The contact hypothesis

The contact hypothesis (Allport, 1954) proposed that personal contact between in-group and out-group members could reduce ethnic prejudice. In line with this hypothesis, a range of empirical studies have demonstrated that contact with ethnic minority groups was associated with lower levels of prejudice (Hamberger & Hewstone, 1997; Stein et al., 2000) and that positive intergroup attitudes could reduce right-wing extremism (Beelmann & Heinemann, 2014; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). As evidenced by a meta-analysis of 515 studies, this prejudice-reduction effect also resulted from friendship between in-group and out-group members (Pettigrew et al., 2011). Intergroup friendship has also been utilized as a tool for prejudice reduction toward immigrants among right-wing groups (Cutts et al., 2015). Bowyer (2009) provided additional evidence in line with the contact hypothesis through research which identified lower levels of hostility directed at Black people in neighborhoods where White people lived among large Black populations, mainly due to increased neighborhood contact. Based on a multilevel path analysis, Green et al. (2016) found that positive, everyday interactions with immigrants reduced radical right-wing voting patterns via decreased threat perceptions. Inverse corroboration of this theory comes from research which demonstrated that low levels of contact with foreigners were associated with high levels of FRWA (Fuchs, 2003). Doosje et al. (2012) provided support for Fuchs’ (2003) findings by highlighting the association between negative perceptions of out-groups, caused by purposely avoiding contact with such groups, and radical right-wing attitudes. These studies lend support to the assumption that through intergroup contact with individuals of an ethnic minority, adolescents may be less reliant on parental views and place more emphasis on their own experiences when developing their political personality, thereby weakening the presumed association between parental and adolescent FRWA.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

The aims of the current study were twofold: First, to analyze the association between perceived parental FRWA and adolescent FRWA, and second, to assess the unique and moderating effects of variables related to the contact hypothesis. By focusing on perceived parental FRWA, as reported by the adolescents, we acknowledged the central tenet of the perception-adoption approach, according to which individual perceptions of parental political attitudes – which can be more or less accurate – largely determine how parental information and values are detected, interpreted, and adopted. Finally, by including two different measures for the contact hypothesis (individual-level intergroup friendship and perceived exposure to ethnic minority group members in the social environment aggregated on the school class level), two separate conclusions can be drawn regarding the role of intergroup contact. The below hypotheses were tested, whereby H4 and H5 refer to the presumed moderating effect of intergroup contact.

H1. The greater the adolescents’ perception of their parents’ level of FRWA, the greater their reported level of FRWA will be.

H2. Adolescents with more ethnic minority friends will hold less FRWA than adolescents without any friends from ethnic minority groups.

H3. The higher adolescents’ perceived exposure to ethnic minority group members in the immediate social environment, the lower their reported level of FRWA will be.

H4. The parent-adolescent association in FRWA will be weaker for adolescents with more ethnic minority friends.

H5. The parent-adolescent association in FRWA will be weaker for adolescents with a higher exposure to ethnic minority group members in their immediate social environment.

Materials and Methods

Data and Procedure

The data for our study stem from a representative, cross-sectional student survey on right-wing extremism among seventh and ninth grade adolescents in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein, conducted by the Criminological Research Institute of Lower Saxony in 2018 (see Krieg et al., 2019). We employed secondary data analysis within the present study, and the study analyses were not pre-registered. At the time of writing, Schleswig-Holstein had 2,910,875 inhabitants, of which 49.0% were male, 8.6% were of foreign origin, and 9.0% received benefits (Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein, 2021a; 2021b). The population density of 184 inhabitants/km² was about one fifth below the national average of 233 inhabitants/km² (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2020). The median gross monthly earnings were €2271 (Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein, 2020).

The study was approved by the Ministry of Education and Science of Schleswig-Holstein. All study procedures were conducted in compliance with agreed-upon ethical standards (i.e., informed consent, anonymity for data generation and processing, confidentiality of the research team at all stages), as well as the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Data collection was carried out between February and June 2018. To ensure representative sampling, a random sample of 395 school classes was drawn based on a class list provided by the Statistical Office for Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein, containing schools in four regions of Schleswig-Holstein: Itzehoe, Lübeck, Kiel, and Flensburg. The selected schools were invited to the study by means of a letter posted to the school principal. Once schools had expressed an interest in taking part, all adolescents in the participating school classes were given a study information leaflet and consent form to read and share with their parents/guardians. The adolescents’ parents/guardians hereby received a study information leaflet which included details of the study’s funding and the survey’s contents (e.g., political attitudes). Only those adolescents whose parents provided written informed consent on behalf of the adolescents, were able to partake in the survey. Participants were also informed that (a) study participation was voluntary, (b) the answers were processed anonymously, (c) the survey could be interrupted at any time, (d) individual questions could remain unanswered, and (e) non-participation would not result in any disadvantages. The survey was designed as an online computer-administered class exercise and was conducted in the presence of at least one teacher and a trained study leader in the school computer rooms. The duration of the survey was approximately 45 minutes.

The sample was stratified according to age group (seventh and ninth school year), the four regional court districts of Schleswig-Holstein, and the two predominant school types in Schleswig Holstein (grammar school and community school). These schools differ in relation to qualifications gained; grammar schools result in the equivalent of A Level qualifications and allow access to higher education, whilst qualifications from community schools permit access to further vocational education and apprenticeships (Fernandez-Kelly, 2012). Of the 395 eligible school classes who were invited to partake in the study, 43.5% participated, whilst the response rate at the individual student level in the participating classes was 69.2%. The main reasons given by the school principals for refusal to partake included scarce time resources, a shortage of teaching staff, and problems within the school. At the student level, the reasons for non-participation were mostly the illness of a pupil or the lack of parental consent (which includes students who forgot to return the signed consent form to their teachers). Overall, 2824 out of 9995 sampled students took part in the survey, which corresponds to a total response rate of 30.1%. Nevertheless, there is no empirical evidence that the realized sample is systematically biased. The composition of the sample with respect to the different types of schools and the regions is similar to the proportions in the population (Krieg et al., 2019).

Participants

The present dataset differed from the primary dataset as only cases involving German adolescents were included in the current study. This decision was based on the correspondence between the concepts related to right-wing extremism and German nationality, since many questions heavily related to being German (e.g., “Germans should have the courage to hold a strong national feeling”). Individuals were considered to have German nationality in cases where the individual: (1) was born in Germany and has German citizenship, (2) was born in Germany but has foreign citizenship, (3) born elsewhere but has German citizenship. Adolescents who were born in Germany and/or have German citizenship, who have at least one parent who was also born in Germany and/or has German citizenship, were included in the analysis. This decision was based on ensuring the inclusion of adolescents who are bound to Germany through birth and/or citizenship and whose parents provide little or no foreign influence. The German background of the adolescents is essential to the dimensions of the FRWA scale, in particular the concept of xenophobia. The original sample size of 2824 adolescents was thus reduced to N = 2693.

The adolescent’s gender divide within the sample was relatively even (50.2% male, 49.8% female). Almost two fifths (39.6%) of adolescents attended a grammar school, whilst over three fifths (60.4%) attended a community school. Only 6.2% of adolescents’ families were in receipt of benefits (i.e., public assistance, unemployment benefits, and/or social benefits). It can be assumed that the type of school attended and the receipt of benefits reflects differences in the socioeconomic status of adolescents and their families. The receipt of any type of benefit can usually be seen as an indicator of socioeconomic status as it reflects the financial situation of the family (e.g., Ensminger et al., 2000). A study by Baumert et al. (2006) showed that the mean socioeconomic status in Germany was lower within community school types, while it was higher within grammar school types. The average age of the sample was 14.70 years (SD = 1.19; range = 12–19). The 7-year age range may result from the participation of two different school class levels (years seven and nine), in addition to the fact that the German school system generally requires the repetition of a school year in cases where the necessary grades to pass were not achieved.

Measurement

Dependent variable

Adolescent FRWA scale

This scale was based on nine different self-reported items related to the following dimensions: xenophobia (one item: “There are too many foreigners living in Germany”), Islamophobia (one item: “Muslims should be prohibited from immigrating to Germany”), homophobia (one item: “It is disgusting when homosexuals kiss in public”), approval of a right-wing authoritarian dictatorship (three items e.g., “A dictatorship is the best form of government”), and chauvinism (three items e.g., “The ultimate goal of German politics should be to give Germany the power and prestige it deserves”). The three items relating to xenophobia, islamophobia, and homophobia stem from the established GMF scale (Gruppenbezogene Menschenfeindlichkeit - English: group-focused enmity, Heitmeyer, 2002). Details relating to the scale development of the GMF and its short-forms, including psychometric properties, have been reported by Kemper et al. (2013). Here, the internal consistency was rated as good across the initial data collection points between 2005–2011 (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.61– 0.83) and the test-retest reliability can also be considered as good, with correlations ranging between r = 0.66 and 0.71 (Kemper et al., 2013). The items relating to the approval of a right-wing authoritarian dictatorship (three items) and chauvinism (three items) stem from the established FR-LF scale (Fragebogen zu Rechtsextremen Einstellungen – Leipziger Form, Decker et al., 2006). The FR-LF scale has been validated for application among both adults (Decker et al., 2013) and adolescents (Krieg, 2022). Among an adult sample in Germany (Decker et al., 2013), the internal consistency of the overall FR-LF scale was rated as very good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94). Previous research among a similar adolescent sample in Germany (Krieg, 2021) established the overall FR-LF scale’s internal consistency as excellent (McDonald’s Ω = 0.94) and that of the sub-scales as ranging from acceptable to good (Ω = 0.76–0.86).

Within the present study, each item measured the adolescents’ attitudes based on the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the statement provided (1 - completely disagree, 2 - tend to disagree, 3 - tend to agree, or 4 - completely agree). Exploratory factor analyses revealed that each of the three items belonging to the concepts of ‘approval of a right-wing authoritarian dictatorship’ and ‘chauvinism’ loaded on one common factor, with factor loadings ranging between 0.73 and 0.85 for ‘approval of a right-wing authoritarian dictatorship’, and between 0.79 and 0.85 for ‘chauvinism’. To ensure that each of the five dimensions contributed equally to the overall scale, we created subscales for the constructs of ‘approval of a right-wing authoritarian dictatorship‘ and ‘chauvinism‘. We based these on the highest reported score on each of the three items. All five dimensions were then formed into a single sum scale variable measuring the extent of adolescent’s FRWA (the higher the value, the more extreme the FRWA). The overall scale ranged from 5 to 20 (M = 10.28; SD = 3.53) and showed an acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.70).

Independent variables

Parental FRWA scale (Adolescent-reported)

Since the original study did not survey the adolescents’ parents, the parental FRWA scale was based upon adolescents’ perceptions of parental views rather than parent-reported attitudes. The parental FRWA scale was based on the same concepts and variables as the adolescent scale. Each variable measured parental attitudes based on the extent to which adolescents believed their parents would agree or disagree with the statement provided (1 - completely disagree, 2 - tend to disagree, 3 - tend to agree, or 4 - completely agree). Exploratory factor analyses revealed that each of the three items belonging to the concepts of ‘approval of a right-wing authoritarian dictatorship’ and ‘chauvinism’ loaded on one common factor, with factor loadings ranging between 0.74 and 0.87 for ‘approval of a right-wing authoritarian dictatorship’, and between 0.80 and 0.87 for ‘chauvinism’. We followed the same procedure as described above for the formation of a single sum scale variable measuring the extent of perceived parental FRWA (the higher the value, the more extreme the perceived FRWA). The overall scale ranged from 5 to 20 (M = 10.29; SD = 3.53) and showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.75).

Ethnic minority friends

A scale created for the current study based on asking adolescents about the country of origin for their three closest friends (initial answer options: “Germany”, “Turkey”, “Russia”, “Poland”, and “other”). These initial answer options were then recoded into “German” or “other ethnic background” as an indicator for the ethnic background of each friend. The adolescents’ responses were then combined to form a sum scale of the number of ethnic minority friends. Following this, the variable ranged from 0 - no ethnic minority friends to 3 - three ethnic minority friends. Approximately two-thirds (67.9%) of adolescents reported zero ethnic minority friends. Whilst 19.2% of adolescents had one ethnic minority friend, reports of two or three ethnic minority friends were lower at 10.0 and 3.0%, respectively.

Exposure to Ethnic Minority Group Members

A scale created for the current study based on the combination of four ordinal variables asking the adolescents to estimate the percentage of ethnic minority individuals within four different social environments (neighborhood, school class, peer group, and extracurricular activities club). The original answer options of 0% - none, 25% - quite little, 50% - half, 75% - quite a lot, and 100% - everyone were recoded into numbers ranging from 0 (no contact) to 4 (100% contact). All four variables were then combined to form a single sum scale ranging from 0 (no contact in any environment) to 16 (100% contact in all environments). Despite exposure to some of the same environments, adolescents with FRWA may report seeing more ethnic minority individuals than people who do not hold these attitudes. In order to attain a more objective measure, we aggregated the scale on the school class level by computing the mean value of exposure to ethnic minority group members for each school class.

Control variables

The control variables included adolescent’s gender (0 - female, 1 - male), school type (0 - grammar school, 1 - community school), grade level (0 - seven, 1 - nine), as well as whether the adolescent’s family were in receipt of benefits (initial answer options were: yes, no, and I don’t know). Following the recoding of the I don’t know option into a missing value in preparation for analysis, this variable had two answer options (0 - no, 1 - yes).

Table 1 provides an overview of the means, standard deviations, and correlations between our main variables. We provided Spearman correlation coefficients as the variables were not normally distributed.

Analytical Strategy

Due to the hierarchical data structure with students nested within school classes, we applied multilevel models. Such models account for dependencies in the data and allow the simultaneous investigation of effects at different hierarchy levels (Snijders & Bosker, 2012). In order to test our hypotheses, we conducted a series of random intercept models, after running a baseline model to calculate the level of variance in the dependent variable of adolescent FRWA. In the first step, we included the level-1 control variables of adolescent gender, grade level, school type, and receipt of benefits, before adding the central independent variable of parental FRWA in a second step. Third, the two variables related to the contact hypothesis (ethnic minority friends and exposure to ethnic minority group members aggregated on the school class level) were added to the model, whereby the latter was entered as a level-2 variable. Due to the moderately high correlation between these two variables (r = 0.33, p < 0.001), we introduced them separately. In a fourth and fifth step, the two interaction terms “parental FRWA × ethnic minority friends” and “parental FRWA × exposure to ethnic minority group members” were again separately entered into the model. We also calculated standardized values (M = 0, SD = 1) to allow comparison of effects across regression models. The multivariate statistical analyses were based on SPSS, version 25. Since our dependent variable (adolescent FRWA) was continuous, we chose linear regression as an appropriate analysis method (Fahrmeir et al., 2013). Although a Shapiro-Wilk-Test revealed a non-normal distribution of the data (p < 0.001), our large sample size allowed for the use of linear regression since sufficiently large samples yield valid results for any distribution (see Ghasemi & Zahediasl, 2012; Lumley et al., 2002).

Results

Table 1 shows the zero-order Spearman’s correlations among the study variables. The highly significant positive correlation between parental and adolescent FRWA indicates a strong similarity between adolescent-reported parental attitudes and adolescent attitudes. Although neither of the two variables related to the contact hypothesis were associated with adolescent FRWA, the adolescents’ number of ethnic minority friends was positively and significantly correlated with parental FRWA, albeit on a very low level. Table 2 presents the results of the multilevel linear regression models. In the baseline model, an intraclass correlation (ICC) of 15.3% revealed that almost one sixth of the total variance in adolescent FRWA was due to differences between school classes, warranting a multilevel approach. Model 0 produced an estimated grand mean of 10.3, indicating that adolescents reported relatively high levels of FRWA when averaged across all school classes.

The results of Model 1 showed that male gender and a lower grade level were both positively and significantly associated with adolescent FRWA, while attending a grammar school was related to significantly lower levels of FRWA when compared to attending a community school. In comparison to the baseline model, this set of individual-level variables explained 0.4% more of the within-classroom variance. A likelihood-ratio test showed that the goodness of fit increased significantly when adding the control variables to the null model (χ2 (4) = 87.7, p < 0.001).

Model 2, which additionally included adolescents’ perceived level of parental FRWA, revealed a strong positive and significant association between parental and adolescent FRWA. The explained level-1 variance in Model 2 showed a considerable increase in comparison to the baseline model, indicating the great explanatory power of perceived parental FRWA. Again, a likelihood-ratio test showed that the goodness of fit increased significantly from Model 1 to Model 2 (χ2 (1) = 1618.3, p < 0.001). The standardized ß-coefficient of parental FRWA (0.73) can be interpreted as quite large, pointing to the importance of perceived parental attitudes for adolescents’ own FRWA.

Model 3 showed that adolescents with more ethnic minority friends reported lower levels of FRWA. This was also evident for adolescents with a higher exposure to ethnic minority group members in the social environment, as shown in Model 4. In additional analyses where we entered the two contact hypothesis variables together, both coefficients slightly decreased but remained statistically significant, though to a lesser extent. After inclusion of these variables, the relationship between perceived parental and adolescent FRWA remained positive and highly significant in both Model 3 and Model 4. Again, likelihood-ratio tests showed that the goodness of fit increased significantly in both models, compared to Model 2 (Model 3: χ2 (1) = 9.07, p < 0.001; Model 4: χ2 (1) = 8.03, p < 0.001), whereby the inclusion of the ethnic minority friends variable led to a greater increase in explanatory power than the exposure to ethnic minority group members variable.

Finally, Models 5 and 6 tested whether the two variables related to the contact hypothesis moderated the association between perceived parental and adolescent FRWA. The results reported in Model 5 indicated a small, but significant negative moderation effect for the ethnic minority friends variable, meaning that the strength of the association between perceived parental and adolescent FRWA decreased with a higher number of ethnic minority friends. According to Cohen’s (1988) guidelines, the corresponding standardized ß-coefficient of −0.14 can be interpreted as small. The set of variables in Model 5, including the interaction term, explained the highest proportion of individual-level variance in FRWA across all models. Adding the interaction term significantly improved the model fit, compared to Model 3 (χ2 (1) = 9.9, p < 0.001).

The interaction term between perceived parental FRWA and classroom-aggregated perceptions of exposure to ethnic minority group members displayed in Model 6 represented a cross-level interaction. Including a random slope for the lower-level variable involved in the cross-level interaction (as suggested by Heisig & Schaeffer, 2019) did, however, not yield substantially different results. Model 6 did not show an improved fit compared to Model 4 (χ2 (1) = 2.1, p = 0.15).

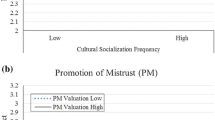

In order to visualize the significant interaction effect between perceived parental FRWA and number of ethnic minority friends, we performed a simple slope analysis based on the unstandardized coefficients (see Fig. 1). The results show that the association between perceived parental and adolescent FRWA is strongest for adolescents who report having zero ethnic minority friends (b = 0.70, p < 0.001), while the association weakens with a higher reported number of ethnic minority friends (one friend: b = 0.64, p < 0.001, two friends: b = 0.58, p < 0.001, three friends: b = 0.53, p < 0.001). Thus, the relationship between perceived parental FRWA and adolescent-reported FRWA is comparably strong among adolescents with a lower compared to higher numbers of ethnic minority friends.

Discussion

To our knowledge, previous research has not explored the interplay of parental and ethnic minority peer contact factors in relation to adolescent FRWA. By including both the role of adolescent-reported parental attitudes and ethnic minority peer contact as correlates of FRWA during the adolescent stage, the present study provides a unique and contemporary picture of the interplay between parental and peer socialization factors in relation to political attitude formation during adolescence. More specifically, the findings highlight the relationship between perceived parental FRWA, the role of intergroup friendship and exposure to ethnic minority group members, and adolescent FRWA. The study findings help to fill the existing knowledge gap regarding the interplay of parental political socialization and ethnic minority peer influences (i.e., contact hypothesis factors) in shaping extremist political attitudes among adolescents. Moreover, the evidence for a moderating effect of friendship with individuals of an ethnic minority further highlights unique opportunities for further research, especially in relation to the prevention of FRWA among German adolescents.

Our results demonstrated a strong positive and statistically significant association between perceived parental FRWA and adolescent FRWA, corroborating H1. The results also showed that friendship with individuals of an ethnic minority, as well as higher levels of exposure to ethnic minority group members (aggregated on the school class level), were statistically significantly correlated with the adolescents’ reported FRWA (H2 and H3). In addition, we found evidence for a statistically significant interaction between perceived parental FRWA and friendship with ethnic minority individuals (H4), meaning that a greater number of ethnic minority friends significantly weakened the link between perceived parental and adolescent FRWA. Our central finding of a parent-adolescent similarity in far right-wing political attitudes supports findings from other recent studies on the transmission of political attitudes (e.g., Avdeenko & Siedler, 2017; Boonen, 2019; Meeusen & Boonen, 2020). Consistent with research evidence by Sturzbecher & Landua (2001) regarding gender differences in FRWA among German adolescents, we found greater FRWA among males than females. Our results also corroborate previously discussed research findings regarding a greater extent of FRWA among community school students (Maresch & Bliesener, 2015; Sturzbecher & Landua, 2001). Previous evidence on the prevalence of far right-wing popularity among those experiencing economic hardship (Rooduijn & Burgoon, 2018) coincides with the results from Model 1, which showed greater FRWA among adolescents whose families were in receipt of benefits.

Interestingly, neither of the two contact hypothesis variables were significantly related to adolescent FRWA (dependent variable) on a bivariate level. Instead, these variables were significantly, albeit weakly, associated with perceived parental FRWA. In additional multilevel regression models that excluded perceived parental FRWA, we found that the coefficients were largely reduced and that the ethnic minority contact variables were no longer significantly related to the dependent variable. Hereby, statistical significance was only achieved following the inclusion of parental FRWA. This observation lends support to the idea that there may be some confounding at work. This means that the (originally) non-significant contact hypothesis variables were significantly associated with the (omitted) variable of parental FRWA, reflecting the effect of this variable in addition to its own. After adding parental FRWA, the variables no longer captured the partial effect of the prior omitted variable but reflected its ‘true’ effect.

Possible theoretical explanations for the strong parent-adolescent similarity in FRWA included the parental role in political socialization (Jennings et al., 2009), identification with and internalization of parental political attitudes (Davies, 1965; Kinder & Kam, 2010), as well as the (cultural) transmission theory (Fend, 2009; Jennings et al., 2009; Klabutscher, 2009; Meeusen & Dhont, 2015; Rico & Jennings, 2016). Since we studied perceived parental FRWA, we followed the arguments of the perception-adoption approach (Hatemi & Ojeda, 2021), laying a focus on adolescent agency in regard to the adoption of parental political orientations. The examination of adolescents’ ethnic minority contact in relation to FRWA was motivated by previous research that demonstrated an association between xenophobic attitudes and far right-wing political orientations (Frindte et al., 1996; Maresch & Bliesener, 2015). Our results also provide support for a link between friendship with out-group members and positive evaluations of the entire out-group (Pettigrew et al., 2011), as well as associations between positive intergroup attitudes and lower levels of right-wing extremism (Beelmann & Heinemann, 2014).

Our results generally lend support to the idea that close peer relationships, as well as the wider peer ecology and social environment, shaped adolescents’ FRWA to a similar degree. Further analyses showed that when including both correlates simultaneously in one regression model, both coefficients slightly decreased but remained statistically significant. This points to unique contributions of both types of ethnic minority contact to FRWA levels, highlighting the dual importance of close peer relationships and the wider social environment for shaping extremist political orientations. In other words, the structural component of direct or indirect exposure to ethnic minority group members appeared to be decisive for adolescents’ FRWA beyond close, direct relationships with ethnic minority group members. The hypothesis of ‘vicarious contact’, which is based on concepts of social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) and involves observing in-group members successfully interact with out-group members (Mazziotta et al., 2011), may constitute an explanatory mechanism for these results. According to this concept, observing other in-group members interacting with individuals belonging to an ethnic minority can lead to the acquisition of behavioral scripts about how to behave in similar cross-group situations, and may also shape intergroup attitudes and one’s willingness to engage in direct intergroup contact.

Furthermore, while both types of ethnic minority contact appear to be significant due to similarly strong correlates of lower FRWA among adolescents, only close and direct relationships in the form of friendships appear to have the potential to offset the parent-adolescent similarity of FRWA. Considering the significance of the peer group in adolescent identity development (Kliem et al., 2018a), one possible explanation for the differential strength of intergroup friendship in the relationship between perceived parental and adolescent FRWA may be that close friendships provide adolescents with direct experiences to inform their own opinions. In contrast, the absence of such direct experiences may result in a greater reliance on parental attitudes. Existing research has shown that individuals who maintained friendships with ethnic minority peers exhibited less FRWA due to more positive evaluations of out-group members (Beelmann & Heinemann, 2014). Direct friendships with individuals of an ethnic minority may thus result in more positive out-group evaluations, which may be more influential than the evaluations provided by right-wing oriented parents.

Given the significant influence of the peer group on adolescents’ political beliefs (Harvey, 1972), it is also possible that adolescents with more ethnic minority friends reported lower FRWA and were less influenced by perceived parental attitudes because of fewer right-wing political beliefs held within the peer group. Considering the association between xenophobia and right-wing extremism (Frindte et al., 1996; Maresch & Bliesener, 2015), it is therefore possible that adolescents’ ethnic minority friends are generally less likely to believe in far right-wing ideologies (e.g., due to personal experiences of xenophobia). Alternatively, or in a supplementary fashion, selection processes may lead like-minded individuals to group together. However, this idea warrants further study, ideally by means of longitudinal data on the extent of FRWA held by adolescents’ friends.

To conclude, our finding that friendship with individuals of an ethnic minority qualified the parent-adolescent similarity link in FRWA is likely to be indicative of adolescent agency and the active role that adolescents take in forming their own political attitudes (see Hatemi & Ojeda, 2021; Meeusen & Boonen, 2020). Rather than uniformly internalizing and replicating their parents’ political attitudes, adolescents appeared to critically consider whether they wished to adopt their parents’ perceived preferences. It may even be the case that some adolescents whose parents held strong FRWA sought out foreign friends mainly because they did not share their parents’ orientations.

Based on these findings, the negative link between intergroup friendship and adolescent FRWA could both be the result of self-selection and/or reverse causation, but it may also prevent the adoption of parental FRWA and thereby act as a protective factor. Further research should examine the extent to which, and under which conditions, such friendships can prevent the adoption of parental FRWA among adolescents. Future studies should also take a closer look at the microprocesses of socialization within the family, such as the frequency of political discussion in the home or the quality of parent-adolescent relationships, in order to gain a clearer insight into the likelihood of attitude transmission. For example, past research has indicated that while political discussions in the home improved perceptions of parental attitudes, they did not foster motivations to adopt parental values (Hatemi & Ojeda, 2021). On the other hand, parent-child closeness led to a better adoption of perceived parental orientations (Hatemi & Ojeda, 2021). To further study the process of political socialization among adolescents, future research should involve further factors that may hinder or promote the process of attitude adaptation.

Implications and Recommendations

Since extreme right-wing attitudes are once again gaining popularity within contemporary Germany, our research proves relevant to the current political climate. The family and the education system arguably hold the primary responsibility for preventing the development of far right-wing extremism among adolescents (Jaschke, 2012). In light of our findings, which indicate a positive association between perceived parental and adolescents’ FRWA, the education system may offer valuable opportunities for the provision of political education in cases where parents hold far right-wing beliefs. It is thus necessary to ensure that German secondary schools provide effective political education on the dangers of right-wing extremism in order to combat the adoption of parental FRWA among students.

It is unclear to what extent current educational programs, such as the national program “Demokratie Leben!” (i.e., to live democracy; see Bundesministerium für Familie et al., 2021) that aims to prevent extremism and facilitate democracy in Germany, incorporate educative and preventative measures relating to the cultural transmission of FRWA into their sub-programs. We therefore recommend the conduction of a nationally representative study that examines the dimensions, as well as the effectiveness, of political education targeting right-wing extremism within German secondary schools. Particular attention should be paid to the role of the family, especially of the parents, in that students should be actively encouraged to think critically about the FRWA that they may be exposed to at home. The capability of teachers to provide adequate safeguarding in relation to this issue should also be investigated. A recent study in Germany (see Frindte, 2021) showed that democratic practices constituted an important condition for reducing negative effects of FRWA. Moreover, democratic and egalitarian structures, processes, and relationships within school classes hold the potential to enhance the development of democratic attitudes among adolescents (Frindte, 2021). Teacher training courses should also ensure that teachers can identify the early signs of FRWA, which may develop as a result of cultural transmission. Educational discussions regarding the political attitudes held among adolescents’ social networks (i.e., family, peers) may be beneficial here. Nevertheless, more research into educational methods of identifying such transmission-based FRWA must be conducted.

Current programs to tackle racism and discrimination in German schools (e.g., Schule ohne Rassismus – Schule mit Courage) employ a variety of strategies, including self-commitment to actively oppose any form of future discrimination, to intervene in the event of conflicts, and to hold regular project days on the topic (Schule ohne Rassismus, 2020; for an overview of the programs implemented in Germany, see Möller, 2014). However, there is still a need to examine current aspects of program dissemination and effectiveness according to scientific standards (Kliem et al. 2018b). Within the individual projects, there is no obligation to evaluate and overall, there is only little investment in systematic program evaluation.

Research has shown that intervention programs based on experiences of direct contact and social cognitive training (e.g., to increase empathy) produced the strongest effects within the reduction of prejudice and the facilitation of positive intergroup attitudes among adolescents (see Beelmann & Heinemann, 2014). Such methods should be used to develop further national initiatives that specifically target the facilitation of intergroup friendship. It is essential to ensure that German schools provide effective initiatives to facilitate friendships between German and ethnic minority students to reduce FRWA among adolescents. A meta-analysis on the effectiveness of direct and indirect contact-based interventions showed that these can positively influence ethnic attitudes even in the long term (Lemmer & Wagner, 2015).

Study Limitations and Future Research

It is firstly important to note that the present study was unable to infer causality because the data used was observational rather than experimental, meaning that the current findings were limited to associations (Weisberg, 2005). Nevertheless, these associations provided meaningful research insights. Considering past research which indicated that parent-adolescent political attitude similarity was greater when adolescents reported perceptions of parental views (i.e., projection process) in comparison to when parents reported their own views (i.e., transmission process), questions regarding the accuracy of adolescents’ perceptions can be raised (Gniewosz & Noack, 2006). In other words, it is not clear whether the positive association between parental and adolescent attitudes is a result of projection or transmission processes. On a more methodological basis, the correlation may also stem from adolescents’ assumptions of parental attitude consensus, which has been identified in past studies (Clement & Krueger, 2000; Gniewosz & Noack, 2006). In order to address this limitation, future research should involve the surveying of parents and their actual FRWA so that the accuracy of adolescents’ perceptions regarding parental views can be established. Irrespective of the accuracy of adolescents’ perceptions of parental FRWA, however, more recent empirical research stressed the pivotal importance of individual perception in the political attitude formation process (Hatemi & Ojeda, 2021), with the transmission of parental political values occurring less than half of the time. Within the perception-adoption context, it may also be possible that political orientations of adolescents create discussion in the family, which, in turn, may be associated with increased parental awareness and a change in their political attitudes (i.e., reverse causation). Longitudinal and multi-informant data is needed to assess such bi-directionalities in the political socialization process of adolescents.

Another limitation concerns the measure of exposure to ethnic minority group members, since it lacked any assumption regarding the nature of such contact. This variable was relatively ambiguous in nature since the survey did not include questions on the form, intensity, and evaluation of contact with out-group members. Such contact may be short-lived, impersonal, and thereby mostly meaningless, as well as positive, negative, or neutral in nature. Without information regarding the nature of such contact, it was difficult to gain a full understanding of the relationship between the extent of adolescents’ exposure to ethnic minority group members and the level of adolescents’ FRWA. Considering this limitation, future research should incorporate further questions on individual appraisals of such contact experiences (e.g., nature of contact and the ascribed significance).

As in all survey studies, the participants’ responses may have been influenced by social desirability or deliberate deception, although such processes should have been kept to a minimum by providing the participants with detailed information about the underlying data protection mechanisms (e.g., anonymous survey, no feedback to parents, school, or teachers). The response rate of 30.1% can be classified as moderately satisfactory when comparing with other methodological approaches (e.g., telephone surveys) which typically receive even lower response rates (see Heim et al., 2016; Keeter et al., 2017). A greater frequency of student-directed reminders regarding the parental consent form may have improved this response rate. The results may also be subject to the issue of under-reporting considering that study participation was dependent on parental consent. It cannot be ruled out that parents who held FRWA may have been less likely to provide parental consent given that the information leaflet informed parents that the survey was about political attitudes. Furthermore, although it is possible that the adolescents provided inaccurate self-reports regarding the receipt of benefits due to a lack of awareness, previous research found that older adolescents (over the age of 14) generally provided more accurate reports of their socioeconomic status (Ensminger et al., 2000). Since this age coincides with the average age of the current sample, it is assumable that adolescents provided accurate responses. Adolescents were also provided with an I don’t know option to minimize the frequency of incorrect answers, which was ultimately categorized as a missing value during analysis.

Finally, as this study estimated and reported parent-adolescent associations rather than causal effects, the disentanglement of heredity and environmental influence remains challenging and could not be solved in the framework of this study. There may also be the problem of self-selection of adolescents into certain peer groups, such as those based on personality traits or attitudes promoting intergroup contact. Having an ethnic minority friend may be associated with less FRWA, or the other way around. Again, longitudinal data is needed to test such relationships. Despite these shortcomings, our study provides evidence for the important role of both the family and peer environment for shaping political orientations in early and mid-adolescence, as well as the interaction between these forces.

Data availability

The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions. Anonymized data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the Criminological Research Institute of Lower Saxony.

References

Adriani, F., & Sonderegger, S. (2009). Why do parents socialize their children to behave pro-socially? An information-based theory. Journal of Public Economics, 93(11–12), 1119–1124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.08.001.

Allport, G. W. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

ARD. (2019, August 26). Rechtsextreme Wollten Migranten Jagen [Right-wing extremists wanted to hunt migrants]. https://www.tagesschau.de/investigativ/ndr-wdr/chemnitz-rechtsextreme-ausschreitungen-101.html.

Avdeenko, A., & Siedler, T. (2017). Intergenerational correlations of extreme right‐wing party preferences and attitudes toward immigration. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 119(3), 768–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12190.

Baier, D., Manzoni, P., & Bergmann, M. C. (2016). Einflussfaktoren des politischen Extremismus im Jugendalter—Rechtsextremismus, Linksextremismus und islamischer Extremismus im Vergleich [Influencing factors of political extremism in adolescence— comparison of right-wing extremism, left-wing extremism and Islamic extremism]. Monatsschrift für Kriminologie und Strafrechtsreform, 99(3), 171–198. https://doi.org/10.1515/mkr-2016-0302.

Bandura, A. (1969). Social–Learning Theory of Identificatory Processes. In D. A. Goslin (Ed.), Handbook of Socialization Theory Research (pp. 213–262). Rand McNally.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs.

Barth, J. M., Dunlap, S. T., Dane, H., Lochman, J. E., & Wells, K. C. (2004). Classroom environment influences on aggression, peer relations, and academic focus. Journal of School Psychology, 42(2), 115–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2003.11.004.

Baumert, J, Stanat, P, Watermann, R, Baumert, J, Stanat, P. & Watermann, R. (2006). Schulstruktur und die Entstehung differenzieller Lern- und Entwicklungsmilieus. Herkunftsbedingte Disparitäten im Bildungswesen: Differenzielle Bildungsprozesse und Probleme der Verteilungsgerechtigkeit [Origin-based disparities in education: Differential educational processes and problems of distributive justice] (pp. 95–188). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

BBC. (2020). Hanau shooting: Has Germany done enough to tackle far-right terror threat?. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-51571177.

Beelmann, A., & Heinemann, K. S. (2014). Preventing prejudice and improving intergroup attitudes: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent training programs. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35(1), 10–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2013.11.002.

Bisin, A., & Verdier, T. (2001). The Economics of Cultural Transmission and the Dynamics of Preferences. Journal of Economic Theory, 97(2), 298–319. https://doi.org/10.1006/jeth.2000.2678.

Boonen, J. (2019). Learning who not to vote for: The role of parental socialization in the development of negative partisanship. Electoral Studies, 59, 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.001.

Bowyer, B. T. (2009). The Contextual Determinants of Whites’ Racial Attitudes in England. British Journal of Political Science, 39(3), 559–586. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007123409000611.

Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz. (2019, January). What is right-wing extremism? https://www.verfassungsschutz.de/en/fields-of-work/right-wing-extremism/what-is-right-wing-extremism.

Bundeskriminalamt. (2021, May 4). Politisch motivierte Kriminalität 2020 - Vorstellung der Fallzahlen in gemeinsamer Pressekonferenz [Politically motivated crime in 2020 - Presentation of the case numbers in a joint press conference]. https://www.bka.de/SharedDocs/Kurzmeldungen/DE/Kurzmeldungen/210504_PMK2020.html.

Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend. (2021). Demokratie Leben! [Live Democracy!]. https://www.demokratie-leben.de/.

Clement, R. W., & Krueger, J. (2000). The primacy of self-referent information in perceptions of social consensus. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39(2), 279–299. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466600164471.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge Academic.

Cutts, D., Goodwin, M., Hewstone, M., & Lolliot, S. (2015). Intergroup Friendship, the Far Right and Attitudes toward Immigration and Islam. Research Gate, 1–41.

Davies, J. C. (1965). The Family’s Role in Political Socialization. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 361(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271626536100102.

Decker, O., Brähler, E., & Geißler, N. (2006). Vom Rand zur Mitte. Rechtsextreme Einstellungen und ihre Einflussfaktoren in Deutschland [From the edge to the middle. Right-wing extremist attitudes and their influencing factors in Germany]. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. https://rb.gy/k3rptx.

Decker, O., Hinz, A., Geißler, N., & Brähler, E. (2013). Rechtsextremismus der Mitte. Eine sozialpsychologische Gegenwartsdiagnose [Right-wing extremism of the middle. A social-psychological diagnosis of the present] (pp. 197–212). Psycho-sozial Verlag. https://home.uni-leipzig.de/decker/e406.pdf.

Decker, O., Kiess, J., & Brähler, E. (2016). Die enthemmte Mitte: Autoritäre und rechtsextreme Einstellungen in Deutschland [The uninhibited middle: Authoritarian and extreme right-wing attitudes in Germany]. University of Leipzig.

Degner, J., & Dalege, J. (2013). The apple does not fall far from the tree, or does it? A meta-analysis of parent-child similarity in intergroup attitudes. Psychological Bulletin, 139(6), 1270–1304. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031436.

Doosje, B., Van den Bos, K., Loseman, A., Feddes, A. R., & Mann, L. (2012). “My in‐group is superior!”: Susceptibility for radical right‐wing attitudes and behaviors in Dutch youth. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 5(3), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-4716.2012.00099.x.

Eckstein, K. (2018). Politische Entwicklung im Jugend- und jungen Erwachsenenalter. In B. Kracke & P. Noack (Eds.), Handbuch Entwicklungs- und Erziehungspsychologie [Handbook of Development and Educational Psychology] (pp. 405–423). Springer.

Ensminger, M. E., Forrest, C. B., Riley, A. W., Kang, M., Green, B. F., Starfield, B., & Ryan, S. A. (2000). The validity of measures of socioeconomic status of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 15(3), 392–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558400153005.

Fahrmeir, L., Kneib, T., Lang, S., & Marx, B. (2013). Regression Models. Springer.

Fend, H. (2009). Was die Eltern ihren Kindern mitgeben – Generationen aus Sicht der Erziehungswissenschaft. In H. Künemund & M. Szydlik (Eds.), Generationen Multidisziplinäre Perspektiven [Generations of multidisciplinary perspectives] (pp. 81–104). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Fernandez-Kelly, P. (2012). The unequal structure of the German education system: Structural reasons for educational failures of Turkish youth in Germany. Spaces & Flows: an International Journal of Urban and Extraurban Studies, 2(2), 93–112. https://doi.org/10.18848/2154-8676/cgp/v02i02/53849.

Frindte, W. (2021). Mehr Demokratie wagen: Rechtsextreme Einstellungen von deutschen Jugendlichen und das Potenzial von demokratischer Praxis in Elternhaus und Schule [“Daring More Democracy“: Right-wing Extremist Attitudes of German Youth and the Potential of Democratic Practice at Home and School]. ZRex – Zeitschrift für Rechtsextremismusforschung, 1, 108–130. https://doi.org/10.3224/zrex.v1i1.07.

Frindte, W., Funke, F., & Waldzus, S. (1996). Xenophobia and right-wing-extremism in German youth groups—Some evidence against unidimensional misinterpretations. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 20(3–4), 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(96)00029-6.

Fuchs, M. (2003). Rechtsextremismus von Jugendlichen: Zur Erklärungskraft verschiedener theoretischer Konzepte [Right-wing extremism among adolescents: The explanatory power of various theoretical concepts]. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 55(4), 654–678.

Gabriel, T. (2007). Wo junge Erwachsene und Jugendliche rassistische Deutungs- und Handlungsmuster lernen: Familienerziehung und Rechtsextremismus. In U. Mäder (Ed.), Jugendliche und Rechtsextremismus: Opfer, Täter, Aussteiger [Adolescents and right-wing extremism: victims, perpetrators, dropouts] (pp. 5–26). Fachstelle für Rassismusbekämpfung FRB.

Ghasemi, A., & Zahediasl, S. (2012). Normality tests for statistical analysis: a guide for non-statisticians. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 10(2), 486–489. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijem.3505.

Glass, J., Bengtson, V. L., & Dunham, C. C. (1986). Attitude similarity in three-generation families: Socialization, status inheritance, or reciprocal influence?. American Sociological Review, 685–698. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095493.

Gniewosz, B., & Noack, P. (2006). Intergenerationale Transmissions- und Projektionsprozesse intoleranter Einstellungen zu Ausländern in der Familie [Intergenerational transmission and projection processes of intolerant attitudes towards foreigners within the family]. Zeitschrift Für Entwicklungspsychologie Und Pädagogische Psychologie, 38(1), 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1026/0049-8637.38.1.33.

Green, E. G., Sarrasin, O., Baur, R., & Fasel, N. (2016). From stigmatized immigrants to radical right voting: A multilevel study on the role of threat and contact. Political Psychology, 37(4), 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12290.

Hamberger, J., & Hewstone, M. (1997). Interethnic contact as a predictor of blatant and subtle prejudice: Tests of a Model in four West European nations. British Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1997.tb01126.x.

Harvey, T. (1972). Computer simulation of peer group influence on adolescent political behavior: An exploratory study. American Journal of Political Science, 570–602.

Hatemi, P. K., Medland, S. E., Klemmensen, R., Oskarsson, S., Littvay, L., Dawes, C. T., & Martin, N. G. (2014). Genetic influences on political ideologies: Twin analyses of 19 measures of political ideologies from five democracies and genome-wide findings from three populations. Behavior Genetics, 44(3), 282–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-014-9648-8.

Hatemi, P. K., & Ojeda, C. (2021). The Role of Child Perception and Motivation in Political Socialization. British Journal of Political Science, 51(3), 1097–1118. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000516.

Heim, R., Konowalczyk, S., Grgic, M., Seyda, M., Burrmann, U., & Rauschenbach, T. (2016). Geht’s auch mit der Maus?–Eine Methodenstudie zu Online-Befragungen in der Jugendforschung [Is it also possible with the mouse?–A method study on online surveys in youth research]. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 4(19), 783–805.

Heisig, J. P., & Schaeffer, M. (2019). Why You Should Always Include a Random Slope for the Lower-Level Variable Involved in a Cross-Level Interaction. European Sociological Review, 35(2), 258–279. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcy053.

Heitmeyer, W. (1994). Das Gewalt-Dilemma: gesellschaftliche Reaktionen auf fremdenfeindliche Gewalt und Rechtsextremismus [The Violence Dilemma: social reactions to xenophobic violence and right-wing extremism]. Suhrkamp.

Heitmeyer, W. (2002). Gruppenbezogene Menschenfeindlichkeit. Die theoretische Konzeption und erste empirische Ergebnisse. In W. Heitmeyer (Ed.), Deutsche Zustände. Folge 1 [German Conditions, Edition 1] (pp. 15–34). Suhrkamp.

Heller, A., Decker, O., & Brähler, E. (2020). Prekärer Zusammenhalt. Die Bedrohung des demokratischen Miteinanders in Deutschland. [Precarious cohesion. The threat to democratic coexistence in Germany]. Psychosozial.

Hooghe, M., & Boonen, J. (2015). The Intergenerational Transmission of Voting Intentions in a Multiparty Setting. Youth & Society, 47(1), 125–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X13496826.

Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP). (2019). Global Terrorism Index 2019: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism. Institute for Economics & Peace. http://visionofhumanity.org/reports.

Jaschke, H. G. (2012). Zur Rolle der Schule bei der Bekämpfung von Rechtsextremismus [The role of the school in fighting right-wing extremism]. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 62(18/19), 33–39.

Jennings, M. K., Stoker, L., & Bowers, J. (2009). Politics across Generations: Family Transmission Re-examined. The Journal of Politics, 71(3), 782–799. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381609090719.

Kailitz, S. (2004). Politischer Extremismus in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Eine Einführung [Political Extremism in the Federal Republic of Germany: Introduction]. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Keeter, S., Hatley, N., Kennedy, C., & Lau, A. (2017). What low response rates mean for telephone surveys. Pew Research Center, 15(1), 1–39.

Kemper, C. J., Brähler, E., & Zenger, M. (2013). Psychologische und sozialwissenschaftliche Kurzskalen. Standardisierte Erhebungsinstrumente für Wissenschaft und Praxis [Psychological and social science short scales. Standardized survey instruments for science and practice] (pp. 115–125). Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft.

Kinder, D. R., & Kam, C. D. (2010). American Ethnocentrism Today. In Us against them. Ethnocentric foundations of American opinion (pp. 42–70). The University of Chicago Press.

Klabutscher, A. (2009). Determinanten der politischen Sozialisation und deren Auswirkung auf das politische Verhalten Jugendlicher [Determinants of political socialization and its impact on youth political behavior]. University of Vienna.

Kliem, S., Baier, D., & Bergmann, M. C. (2018a). Prävalenz grenzüberschreitender Verhaltensweisen in romantischen Beziehungen unter Jugendlichen (Prevalence of Teen-Dating-Violence). Kindheit und Entwicklung, 27(2), 110–125. https://doi.org/10.1026/0942-5403/a000251.

Kliem, S., Krieg, Y., Kudlacek, D., Baier, D., & Bergmann, M. C. (2018b). Zur Prävalenz rechtsextremer Einstellungen bei Jugendlichen. Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Befragung aus Niedersachsen. In O. Decker & E. Brähler (Eds.), Flucht ins Autoritäre. Rechtsextreme Dynamiken in der Mitte der Gesellschaft [Flight into Authoritarianism. Right-wing Extremist Dynamics in the Middle of Society] (pp. 241–255). Psychosozial-Verlag.

Kobus, K. (2003). Peers and adolescent smoking. Addiction, 98, 37–55.

Koehler, D. (2014). German right-wing terrorism in historical perspective. A first quantitative overview of the ‘Database on Terrorism in Germany (Right-Wing Extremism)’–DTGrwx’Project. Perspectives on Terrorism, 8(5), 48–58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26297261.

Kreis, J. (2007). Zur Messung von rechtsextremer Einstellung: Probleme und Kontroversen am Beispiel zweier Studien [Measuring right-wing extremist attitudes: Problems and controversies using the example of two studies]. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/199430061.pdf.

Krieg, Y., & Kliem, S. (2019). Rechtsextremismus unter Jugendlichen in Niedersachsen [Right-wing extremism among adolescents in Lower Saxony]. Monatsschrift für Kriminologie und Strafrechtsreform, 102(2), 135–153. https://doi.org/10.1515/mks-2019-2017.

Krieg, Y., Beckmann, L., & Kliem, S. (2019). Regionalanalyse Rechtseztremisums in Schleswig-Holstein 2018 [Regional Analysisof Right-Wing Extremism in Schleswig-Holstein 2018], research report no. 149. https://kfn.de/wpcontent/uploads/Forschungsberichte/FB_149.pdf.

Krieg, Y. (2022). The role of the social environment in the relationship between group-focused enmity towards social minorities and politically motivated crime. KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 74(1), 65–94.

Krieg, Y. (2021). Rechtsextremismus im sozialen Kontext: Mehrebenenanalysen zur Bedeutung von Kontexteffekten in Bezug auf rechtsextreme Einstellungen Jugendlicher [Right-wing extremism in social context: Multilevel analyzes of the significance of context effects in relation to right-wing extremist attitudes among young people]. Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 62(3).

Krüger, C. (2008). Zusammenhänge und Wechselwirkungen zwischen allgemeiner Gewaltbereitschaft und rechtsextremen Einstellungen [Connections and interactions between general willingness to use violence and right-wing extremist attitudes]. BoD–Books on Demand.

Lemmer, G., & Wagner, U. (2015). Can we really reduce ethnic prejudice outside the lab? A meta-analysis of direct and indirect contact interventions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45(2), 152–168. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2079.

Lumley, T., Diehr, P., Emerson, S., & Chen, L. (2002). The importance of the normality assumption in large public health data sets. Annual Review of Public Health, 23(1), 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140546.

Marcia, J. E. (1980). Identity in Adolescence. In J. Adelson (Ed.), Handbook of Adolescent Psychology (pp. 109–137). Wiley & Sons.

Maresch, P., & Bliesener, T. (2015). Regionalanalysen zu Rechtsextremismus in Schleswig-Holstein [Regional analyses of right-wing extremism in Schleswig-Holstein]. Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel. https://kfn.de/wp-content/uploads/downloads/Abschlussbericht_21102015.pdf.

Mazziotta, A., Mummendey, A., & Wright, S. C. (2011). Vicarious intergroup contact effects: Applying social-cognitive theory to intergroup contact research. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 14(2), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430210390533.