Abstract

Practitioners’ characteristics and actions influence the implementation of evidence-based programs, but little is known about the practitioner’s role in the implementation of parent-based programs. The present qualitative study is the first to explore the perceptions of parents and professionals regarding the practitioners’ characteristics and actions which influence the implementation of a parent program directed at children’s behavior problems. Using thematic analysis, data were examined from eight focus groups comprising 24 parents and 19 practitioners who have participated in the Incredible Years parent group program (IYPP). The analysis identified three groups of practitioners’ characteristics perceived to impact the implementation of the IYPP: inferred interpersonal characteristics (genuine interest; empathy and warmth; positive regard; humbleness); inferred intrapersonal characteristics (objectivity; flexibility; well-being; reflexiveness) and objective characteristics (similar age; being a parent; clinical professional background; professional experience with children and the IYPP). These personal characteristics are perceived as serving to underpin practitioners’ actions, and an integrated framework model is proposed where specific practitioners’ actions are understood in relation to personal characteristics. Inferred characteristics are perceived as determinants in the intervention process while objective characteristics are seen as facilitators of parent engagement in the earliest stages of intervention. Finally, most of the characteristics and actions perceived as relevant in this study are contemplated in the IYPP model; however, the practitioners’ intrapersonal well-being, self-reflexiveness and genuineness emerged as characteristics which may merit further consideration. The results from this study suggest that in the IYPP the person of the practitioner may indeed be worthy of more critical examination.

Highlights

-

This is the first study exploring the perceived impact of practitioners’ characteristics and actions in a parenting program.

-

An integrated qualitative thematic analysis is made of both parents and practitioners’ perspectives.

-

Practitioners’ personal characteristics are emphasized in the implementation of the Incredible Years parent program.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Conduct disorders are one of the most common mental and behavioral problems in children and young people (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence NICE (2013), last updated in 2021; Polanczyk et al., 2015). Group-based parenting programs, underpinned by behavioral and social learning principles, are well-established treatments (Kaminski and Claussen (2017)) that are recommended as a first-choice intervention when addressing child conduct problems (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence NICE (2013), last updated in 2021). There is considerable evidence from all over the world pointing to the effectiveness of group-based parenting programs in reducing clinically disruptive child behavior (Buchanan-Pascall et al., 2018; Furlong et al., 2012; Hua & Leijten (2021); Mingebach et al., 2018). Some reviews have also demonstrated that these programs are successful in improving parenting practices (Furlong et al., 2012; Weber et al., 2018) and in enhancing parental psychosocial well-being in the short term (Barlow et al., 2014; Trivedi, 2017).

One of the most widely researched and well-established group programs targeting children’s behavioral problems is the Incredible Years Parent Program (IYPP; Webster-Stratton, 2001). Robust evidence has demonstrated that the IYPP is effective in improving child behavior and positive parenting practices in families of different ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, in both prevention and treatment contexts, and across several countries (Gardner et al., 2017; Leijten et al., 2018; Menting et al., 2013). The programs contents focus on training parents in positive play and the reinforcement of skills aimed at increasing positive behaviors, as along with providing them with a set of nonviolent discipline techniques aimed at reducing negative behaviors (Webster-Stratton & Hancock, 1998). Group discussions are facilitated by trained practitioners (referred to as group leaders) and rely on experiential techniques such as videotape modeling, behavioral rehearsal, and live modeling as key therapeutic methods (Webster-Stratton, 2006). Although the IYPP is largely similar to many other established parenting programs based on the Hanf Model (Kaehler et al., 2016) with respect to content and methods, it specifically emphasizes a collaborative model for working with parents of conduct-disordered children (Webster-Stratton & Herbert, 1993). The underlying collaborative helping process of the program relies on a non-blaming, supportive, reciprocal relationship based on using the therapist’s knowledge and the parents’ unique strengths and perspectives in equal measure (Webster-Stratton & Herbert, 1993), as well as “fitting” treatment to the individual families’ characteristics and needs (Webster-Stratton, 2006). This collaborative model of program implementation requires a degree of clinical skill that may be higher or more stringent than in other models (Webster-Stratton, 2012), and the role of the practitioners who implement the program is particularly emphasized as an important determinant of positive parent outcomes (Webster-Stratton, 2020).

In fact, research has taught us that the implementation of intervention programs is affected by a variety of factors that interact dynamically, including the characteristics of the program, and the inner and outer contexts which frame the program being implemented, in addition to the characteristics of the practitioners implementing the program (Damshroeder et al., 2009; Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Turner et al., 2011). Practitioners indeed play a paramount role in the implementation process as they are the ones who activate all the necessary components of an intervention and mediate the impact of external implementation factors on the participants (Fixsen et al., 2005). Practitioners’ characteristics, such as their skills, perceptions, beliefs and personal qualities, influence the quality of the implementation and are included in important implementation models (Damshroeder et al., 2009; Durlak & DuPre, 2008). In particular, practitioners seem to influence the participants’ engagement and the intervention’s outcomes through three dimensions of implementation: the adherence to the program, the quality of delivery, and the adaptation of the program to the needs of the context (Berkel et al., 2011). These dimensions are also included in the American Psychological Association (APA)’s definition of evidence-based practice in psychology: “the integration of the research knowledge with clinical expertise in the context of particular patient characteristics” (APA, Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice, 2005, p. 5). Therefore, the APA has recommended that research be carried out on the characteristics and actions of the therapist and the therapeutic relationship contributing to the positive outcomes of evidence-based programs (APA, Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice, 2005).

Although parent-based interventions are one of the most widely researched effective interventions for the prevention and treatment of child and youth behavior problems (Carr, 2019; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence NICE (2013)), the study of the practitioner’s role on the outcomes of these type of interventions is not a common research goal (Leitão et al., 2020; Scott et al., 2008), especially if compared with existing research on the role of the intervention characteristics, such as program contents and delivery methods (Garland et al., 2008; Kaminski et al., 2008). In an attempt to address this research gap, a systematic review focused on practitioner related factors in parent interventions directed at children’s behavior problems (Leitão et al., 2020). In addition to demonstrating the impact of therapeutic alliance and fidelity in these parent interventions, the results evidenced that specific practitioners’ actions, assumed or taken during the sessions, were related to parents’ engagement and satisfaction with the intervention, as well as to changes in parenting practices. Some qualitative studies on parents’ perceptions and general experiences of parenting programs have also evidenced that parents view the skills of practitioners who deliver parenting programs as being crucial to their success (Butler et al., 2020). Important practitioner skills valued by parents were: being able to build and facilitate good relationships among parents, being non-judgmental and collaborative as opposed to authoritarian, and conveying warmth, friendliness, empathy, caring and flexibility/adaptability (Butler et al., 2020; Koerting et al., 2014). A specific qualitative review of studies with parenting programs for child behavior problems has also highlighted the importance of the therapist being “down to earth/on one level” with parents (Koerting et al., 2014, p. 665), belonging to a similar cultural or ethnic background to that of the parents, and having the personal experience of parenting a disruptive child (Koerting et al., 2014).

In the case of the IYPP, although this evidence-based parent program has been particularly prominent in underscoring the importance of the clinician’s specific knowledge, relationship characteristics, and collaborative skills to influence positive parent outcomes (Webster-Stratton, 2020), research on the specific practitioners’ characteristics and actions that impact on this program’s outcomes has been sparse, and there is little research testing the specific importance of the practitioner in the implementation of this program. A few quantitative studies with the IYPP have sought to specifically understand the impact of the practitioner’s characteristics and behaviors on the intervention outcomes (Eames et al., 2009, 2010; Scott et al., 2008). They have evidenced that observed practitioners’ behaviors predicted changes in both observed and parent-reported parenting practices (Eames et al., 2009, 2010), as well as improvements in parent-reported child’s behaviors (Scott et al., 2008). Specifically, praise and reflection have been suggested as key practitioner behaviors that influence change in parenting practices, and ongoing research has been recommended as a way to more closely examine individual practitioner’s behaviors, instead of composite skills reported in most published papers (Eames et al., 2010). Certain practitioners’ characteristics (mental health training) have also been associated with their proficiency, while others (gender and age) have not (Scott et al., 2008). Within the realm of qualitative research, the existing studies with the IYPP have focused on studying parents’ general experiences with the program, its overall impact, or perceived barriers and facilitators of implementation, without concentrating on the specific practitioner’s role (Furlong & McGilloway, 2014; Levac et al., 2008; McKay et al., 2020; Patterson et al., 2005; Stern et al., 2008; Webster-Stratton & Spitzer, 1996). To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies to date that have focused on understanding parents or professionals’ perceptions about the practitioner’s specific role in the implementation of this multicomponent program, and evaluating their consistency with the IYPP model’s assumptions.

The Present Study

The APA (2005) has recommended that research should be pursued on those characteristics and actions of the practitioner that contribute to the positive outcomes of evidence-based programs. Wampold et al. (2017) proposed that urgent questions still to be answered are: “What are the characteristics and actions of the more effective therapists? Who are they? What do they do?” (p. 37). The present study thus aims to answer these challenges, addressing a research gap with respect to the practitioner’s role in the implementation of evidence-based parenting programs. In particular, the study intends to more deeply explore those specific characteristics and actions of the practitioners that are perceived as having the greatest impact on the implementation of the IYPP. Following the definitions established in Wampold et al. (2017), using them as guides for the present research, we defined characteristics as the practitioner’s personal qualities, skills or states that are internal to the practitioner and that may extend to other life contexts beyond the intervention setting (relating to the therapist’s being), and actions as the practitioner’s behaviors that can be directly observed during the interactions with parents, occurring either during or between the intervention sessions (relating to the therapist’s doing).

It is within the qualitative research field that the practitioner variables have generally been receiving more coverage. Qualitative analysis provides a detailed description of experiences, perspectives, and meanings (Braun & Clarke, 2013) and it is, therefore, the selected approach to this study. The authors’ standpoint as qualitative researchers relies on a contextualist, constructivist-interpretive paradigm (Braun & Clarke, 2013; Levitt et al., 2017), as researchers assume to be co-constructors of meaning, aiming to understand different interpretations of reality from different participants, while also aiming to inform the construction of an organized and explanatory model on the characteristics and actions that might be relevant in the implementation of a parenting program. Given that both parents and practitioners are central to the delivery of this intervention program, the authors propose an integrated qualitative analysis of both parents and practitioners’ perspectives, in order to inform a more accurate and broad perspective on the IYPP implementation. Focus Groups (FG) are the selected collection method as they replicate the format of the parent groups’ experience, exploring individual experiences and beliefs while at the same time drawing on group dynamics and processes, which usually leads to the emergence of in-depth and rich data. Focus groups have been previously used to explore parents and professionals’ experiences with parenting programs (Berlyn et al., 2008; Law et al., 2009), and specifically in the context of children behavior problems (Garcia et al., 2018).

Method

Participants

Participating were 24 parents who had previously enrolled in an IYPP, and 19 practitioners trained and experienced in delivering the IYPP. Some but not all of the practitioners delivered groups in which some parents included in the present study participated. Detailed participant demographics were assessed through demographic questionnaires and are reported as supplemental material in Tables S1 and S2. All the participant parents were biological parents, except for one grandmother who had participated in the IYPP as a main caregiver, and there were only four fathers. Parents’ mean age was 43 years (SD = 8), most were married/living as married (75%) and had two children (58.3%). They came from diverse educational and socioeconomic backgrounds, from the two geographical areas of Portugal where the implementation of the IYPP in care services is more widely established – Coimbra and Porto. There were parents coming from both community and clinical contexts, with all of them expressing some concerns about their children’s behavior problems. The researchers had no prior relationship with any of the parents participating in the FGs, except for one mother (Jane), a psychologist also trained in the IYPP with whom they had already had professional contacts, having collaborated in previous research projects. Jane’s experience had enriched this study, as she reflected on her separate role as a mother and as a professional who has some theoretical knowledge about the program. Regarding the practitioners, they were mostly cisgender women (one cisgender man) coming from a middle-class socioeconomic background. They had all been trained in the intervention model and they have all delivered at least two IYPP groups, but they were diverse in terms of age, parenthood status, professional background and professional experience with families and with the IYPP, with this diversity being representative of the community of Portuguese IYPP practitioners (Table S2). There were some practitioners with whom the research team had previous relationships in academic, research or professional contexts.

The research team comprised four members, all white women psychologists coming from a middle-class socioeconomic background: one clinical child psychologist and graduate student completing a PhD program in Family Psychology and Family Intervention, and three academic professors with experience in supervising graduate and undergraduate students from the fields of clinical psychology or educational psychology, and expertise in research on child and family psychosocial interventions. Three of the researchers had vast experience in researching and delivering the IYPP in academic and community contexts, with two of them (third and fourth authors) also being certified mentors of this program, with extensive experience in both training and supervising IYPP professionals and in leading research on various facets of the program. The second author is an expert in qualitative research.

Procedures

Recruitment and participant selection

The present research was approved on a preliminary basis by the Ethics Commission of the academic institution where the first researcher is conducting their PhD studies and by the ethics committee of the practitioners’ institutions, when required (one institution). The researchers used a convenience and purposeful sample, selecting the participants that they considered able to provide information-rich data (Braun & Clarke, 2013). Based on the researchers’ professional experience, the criteria for inclusion in the study were defined prior to the recruitment process: parents had to have enrolled in an IYPP group in the last three years previous to the study; practitioners were required to have training in the IYPP and to have delivered at least two IYPP parent groups at the date of the study. The recruitment process began with the practitioners, as they would also be useful for reaching and accessing parents. To recruit practitioners, the research team developed an initial list of contact names of IYPP professionals from the two above mentioned regions, together with three professionals external to the team who had extensive knowledge and access to the network of national IYPP facilitators. Fifty six practitioners were contacted by telephone or email and provided with a description of the study’s main purpose and inclusion criteria. From the total number of practitioners contacted, 19 did not reply to calls or emails, 10 did not meet the inclusion criterion of the minimum number of previously run groups, and eight were unavailable at the proposed schedules for the FGs.

Parents were first identified by practitioners from a contact list provided by IYPP professionals, who were given instructions about criteria for parents’ inclusion in the study. Next, practitioners made initial contact with parents who had once participated in their IYPP groups to briefly explain the goals of the study and to obtain permission from them to be put on a list for contact by the research team with an invitation to participate in the study. Simultaneously, advertisements about the parents’ FGs were also shared in social networks (Facebook®), and interested parents were asked to register their name and contact information in an online survey (n = 9). Via both forms of contact, that is, through practitioners or social networks, parents were informed that if they agreed to participate, their children would be involved in a group activity on the topic of science exploration while the FG was taking place. A total of 51 parents were contacted by the research team, with the following exclusions: 10 did not reply, four did not meet the inclusion criteria, one mother was excluded because the facilitator of the FG had also been a practitioner in her parent intervention group, and 12 parents were unavailable at the dates/times proposed for the FG.

The 19 practitioners and 24 parents who agreed to attend were e-mailed a copy of the informed consent, which provided more information about the study, and were asked to complete an online demographic questionnaire. Participants were distributed and assigned to four FGs of practitioners and four FGs of parents, with groups made with respect to participants’ constraints or convenience of time/place. When possible, the principle of maximum variance was also considered when constituting each group, in terms of the practitioners’ professional background (discipline and level of experience) and the parents’ gender and specific IYPP group attended. The final groups were composed of participants from different backgrounds. Nevertheless, some of the individuals involved knew each other from a previous IYPP context or from other outside contexts.

Data collection

From January to October 2019, eight FGs were conducted (four FGs with practitioners and four FGs with parents), with three to eight participants per group. The settings of the FGs were, in the case of practitioners, a university (two FG) and a hospital (two FG), and in the case of parents, meeting rooms inside two science museums in the city centers. Upon arrival at the FG, participants signed the informed consent and, if they had not done so previously, completed the demographic questionnaires. The FG facilitators verbally described the confidentiality expectations, explicitly assuring parents about confidentiality concerning their IYPP practitioners. FG sessions lasted from 85 to 130 min, with an average time of 114 min.

The semi-structured FG guides followed the principles of Morgan and Krueger’s Toolkit (1998). Guides were preliminarily tested with one parent and two IYPP practitioners who were not included in the FG, and some adaptations were subsequently made in order to clarify the questions for participants. For both parents and practitioners, the guides were made up of reflexive open-ended questions meant to explore: a) what participants perceive to be an effective IYPP practitioner; and b) the specific practitioners’ personal characteristics and behaviors perceived to impact (positively or negatively) the intervention’s processes and results (see Table S3, for detailed interview guides). Although the FG guides defined the central axis of the inquiry, they allowed for the exploration of themes that were specific to each discussion group, and for the refinement of questions between groups, as the researchers were continuously reflecting on the data’s redundancy and newness, and thus adapting the data collection strategy. The first author facilitated the groups and the third and fourth authors were, at-times, co-facilitators and note-takers. Checking for clarification was often done during the FGs, in which the participants were asked to verify whether the facilitators had correctly understood what they intended to say, and at the end of each FG, facilitators had a short debriefing session to discuss relevant content and processual aspects, and the main facilitator registered their subjective impressions in a self-reflective journal. FGs were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by the main researcher and one undergraduate research assistant.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using thematic analysis, from a contextualist position (Braun & Clarke, 2006; 2013). Thematic analysis is a qualitative analytic method providing a systematic approach for identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns of meaning (themes) across a qualitative dataset, which is not tied to a particular theory or epistemological approach and, therefore, can be applied with considerable flexibility (Braun & Clarke, 2006; 2013). The choice of thematic analysis as the method adopted in the present study was made given its ability to provide a rich, detailed and yet complex account of data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Thematic analysis began after the first FG was completed and continued until data saturation had been reached. Data transcripts were imported to and coded in N-Vivo 12 software. The N-Vivo software was used to help the researcher to code data into nodes and themes, to visually explore connections and relationships between codes, and to more efficiently organize data. The two broad themes of Characteristics and Actions were defined a priori, inspired by the classification of Wampold et al. (2017), and this classification guided the researchers during the whole process of data collection, analysis and report. Throughout the process of analysis, it was also found useful to follow the classification made by Beutler et al. (2004), in which a distinction is made between objective and inferred characteristics.

The coding process followed the six recursive phases of thematic analysis, with movement back and forth through steps occurring as needed: 1. Familiarization with the data; 2. Generating initial codes; 3. Searching for themes; 4. Reviewing themes; 5. Definition and naming themes; 6. Producing the report (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The entire data set was scanned and each segment of the interview transcriptions referring to important practitioners’ characteristics or actions was coded. This coding process was first completed with the parents’ data and then repeated with practitioners’ data, collating new codes into the subthemes and adding the necessary subthemes (which happened particularly within the Characteristics theme). This way, parent and practitioner reports were placed side by side so that triangulation between different informants could be analyzed more easily. Discrepant data were always included and analyzed within each subtheme/theme. The coding process continued until the end of transcriptions, and data saturation was reached by the fourth group of each participant category, when relevant information was no longer being added to each theme. Finally, codes, subthemes and themes of the entire data set were reviewed and analyzed in their conceptual relations, until reaching a hierarchical ranking of themes, and valid definitions and names for each theme. Data analysis was led by the first author, supervised by the second author, and reviewed in the final process of thematic coding by the fourth author.

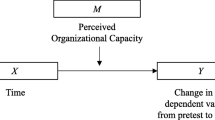

Results

The analysis identified that participants very often referred to the practitioners’ actions as if they were outward manifestations of their inner personal characteristics or traits. In this attribution of meaning, the therapist’s doing is perceived to be intimately connected with the therapist’s being. As actions are understood to be operational derivations from personal characteristics, an integrated framework is proposed, where specific practitioners’ actions are described in relation to specific personal characteristics. Therefore, instead of being independently described, the practitioners’ actions are presented in connection with the description of each inferred characteristic. Table 1 illustrates this thematic organization of the relationship between characteristics and actions. Detailed results are reported below, in the following order: inferred interpersonal characteristics; inferred intrapersonal characteristics; and objective characteristics. Quotes from participants are used to illustrate the identified categories, and fictitious names are used in this manuscript to ensure the anonymity of the participants.

Practitioners’ Inferred Interpersonal Characteristics

Inferred characteristics are the practitioner’s skills that can only be inferred from the therapist’s self-reports or from the therapist’s observed actions occurring during the interaction with parents. Inferred interpersonal characteristics are the specific qualities that facilitate communication and relationships with others, which include four practitioners’ skills: genuine interest; empathy, acceptance and warmth; positive regard, energy and enthusiasm; and humbleness.

Genuine interest, being available and affording full attention to parents

Both parents and practitioners consistently talked about the importance of practitioners having or expressing a genuine interest in the parents, “interested in helping, in being on their side” (Daisy, practitioner). Genuine interest is perceived in the practitioner’s availability to be present for the parents, to hear them out and to respond to their requests: “that presence that shows [you] that I’m here, you can count on me” (Tricia, mother). This sense of availability can be translated into different specific actions, such as facilitating contacts, dedicating time to parents outside the sessions (for example, making weekly phone calls or scheduling make-up sessions with parents who had missed previous sessions), sitting close (in physical close proximity) to parents during the sessions, allowing parents to ask questions and answering them, or simply asking parents about particular situations in their daily lives. The practitioners’ ability to dedicate full attention both to the parents themselves and to what they are saying is considered another important way to express genuine interest in them. Practitioners “know how to listen and show that they want to listen” (Anne, mother) by establishing eye contact, nodding, providing short acknowledgments, paraphrasing, reframing, and asking parents to confirm information. Referring to examples from specific daily routines that parents had previously brought up in group discussions and using children and parents’ names are considered other important actions that reflect practitioner’s higher level of attentiveness and genuine care: “Calling me by my name is something that gives us an identity … it’s like they care” (Sarah, mother).

Empathy, acceptance and warmth

There was a great richness in parents’ descriptions on the topic of empathy, which referred mainly to the ability to understand parents in a deep, private and intimate way, and of knowing how to interpret them beyond the spoken words. Some parents referred to it as the ability to use their own sensitivity to read the parents, as if they were inside their minds: “it seems like they were opening a lock and they could see inside us, they were taking a whole picture of us” (Gina, mother). Practitioners provided more straightforward meanings of empathy, describing it as a stable personal characteristic, an ability to understand parents as if walking in their shoes. Empathy, also described as a sensitivity to the parents’ needs, is presented as a precondition to responsiveness. Only because practitioners know how to read parents, they can respond by adapting their behaviors in accordance with parents’ needs or personal traits, for example, having “the sensitivity to appreciate when the group needs to stop for a break” (Jane, mother). Empathy can also be expressed via the acknowledgement and labelling of parents’ feelings, which can make the individual feel valued and supported, especially in difficult situations. It can also be shown by facial expressions of understanding and acceptance because, as practitioner Claire explained, “it conveys the message (…) that we are in the same boat, (…) that we empathize and that we understand what has been given to us, that we take it for better or for worse”. Both parents and practitioners emphasized that empathic practitioners neither make judgements, nor criticize nor point out failures, although parents underscored this point with greater emotion: “Most of all, understanding. There are no fingers pointed at us, saying you are not doing it right… (…) There’s no judgement there… there’s only the attempt to help, there’s listening, which is really important” (Sunny, mother). Instead of criticizing, empathic practitioners provide ample time and opportunities for parents to share their difficulties, normalize their experiences by stating that they are not alone, and take that moment to engage the rest of the group. In a group of practitioners, an important idea emerged, stating that the distinctive role of the practitioner implementing a parenting program relies precisely on their ability to deal with these critical moments of expressed difficulties by the parents: “Dealing with these challenges, this is where I believe that our role can make a difference” (Sandra, practitioner).

Participants also appreciated that practitioners are gentle, docile, sweet and kind people: “a gentle person” (Louise, grandmother), expressing warmth and affection. This theme was more expressively commented on by parents, while practitioners referred more directly to the actions derived from this characteristic, especially the action of smiling. Smiling was a frequently mentioned action by both parents and practitioners, and it seems to be associated with warmth, presence and care. Many parents also described the importance of physical touch in demonstrating affection, especially in situations of expressed fragility. Another action mentioned was treating all the parents equally. Both parents and practitioners referred to the importance of “working with people with some equity…treating everyone in the same way” (Christina, mother), which implies that practitioners do not “establish a preferential relationship” (Jane, mother) with one parent, do not have preconceptions about them, and afford equal opportunities to all the participants: “it’s not fair to them that we expect nothing or a lot from them, right? They all have to be more or less in the same circumstances” (Vanessa, practitioner).

Positive regard, energy and enthusiasm

Participants frequently referred to the practitioner’s positivity, which was described as a positive regard about the parents and their future, but also as an enthusiastic, energetic and dynamic state underlying the facilitation of the sessions and the interaction with parents: “The facilitator should be dynamic. I mean, cheerful, a positive person (Carolyn, practitioner)”. Effective practitioners are perceived as truly positive and optimistic people who strongly believe in change. They have the ability to focus on the parents’ efforts, strengths and achievements, even the smallest ones, “to see the glass half full when the parent was seeing it half empty” (Tracey, practitioner). This positivity allows the practitioner to appreciate and reinforce parents at all times, either during the sessions, or through the weekly contact calls or the written registries, through verbal praise, positive commenting and material rewards, “Recognizing worth, recognizing our worth” (Lauren, mother). Along with their appreciation and reinforcement of the parents, the IYPP practitioners facilitate the sessions with their energy, vivaciousness, dynamism, good moods and joyfulness: “They were always cheerful. They always had this energy, this good mood” (Sarah, mother), which parents felt as contagious. This dynamic and energetic posture is expressed through smiles, through a lively tone of voice that motivates and grabs your attention, through participating in play games and roleplays which promote cheerful interactions in the group, and also through the use of humor. Positive and energizing actions can only be successfully performed if practitioners truly believe in the IYPP, and if they genuinely feel pleasure and enthusiasm when implementing it; [the practitioner should be] “someone enthusiastic about the program, someone who really likes it and who can convey that enthusiasm to us” (Ellie, mother).

Humbleness and the collaborative role

Parents and practitioners consistently emphasized the importance of the practitioner being/feeling identical to the parents, on the same level, as part of the same community, which in our analysis we refer to as humbleness: “this sense that we are all humans and we all have our weaknesses and strengths… that we know we are dealing with someone like us… I think that is absolutely fundamental” (Sunny, mother). The practitioner’s humbleness is inferred when practitioners offer some form of self-disclosure, share personal experiences and vulnerabilities, assuming doubts, errors, or limitations, just as any human being would do: “When we identify with their difficulties, ‘this is hard for all of us, it is also very hard for me’ (…) I think it places us on the same level” (Jo Ann, practitioner). Participants especially noted the value of sharing difficult parenting experiences: “The fact that they are mothers and that they are not perfect helps us too. And they [themselves] don’t have perfect kids” (Tricia, mother). The participants also explained how humbleness can be expressed by sitting in the middle of the group or by joining the parents on the floor when some type of practice or demonstration is needed, that is, being physically on the same level as the parents.

The practitioner’s humbleness was perceived as a necessary condition to be able to authentically implement the collaborative model underpinning the Incredible Years programs: “If we are not humble, maybe we won’t be genuine or we won’t be able to implement this collaborative and democratic system with such efficiency” (Claire, practitioner). In fact, this humble role implies that the practitioner does not place themself as the expert, someone with superior knowledge, qualifications and information, but rather, affords the parents the main role in how the intervention will play out. This collaborative and humble posture was considered to be conveyed by different actions, such as asking for parents’ ideas and soliciting solutions, in “a very participatory task of problem-solving, like ‘what is this?’, ‘why is this happening?’, ‘how can we solve this?’” (Christina, mother). The answers are then proposed by the parents, who feel responsible for the solution. Instead of imposing, prescribing, dictating information or persuading parents, practitioners suggest, invite and inform about practical strategies, in a relaxed atmosphere: “I think it’s helpful that they feel that we are not there to teach them, we are there to reach a conclusion with them, we are not on a pedestal, we are closer to them…” (Catrin, practitioner). Practitioners are attributed the role to guide parents towards new practices, launching reflexive questions, but giving them freedom to decide, to choose, to experiment. As one mother, Lauren, stated, “They don’t give [us] the fish but they teach [us] how to fish”.

Practitioners’ Inferred Intrapersonal Characteristics

Inferred intrapersonal characteristics are the practitioners’ internal resources for coping with themself and the world around them, ones which can also have implications in the social relationship domain but are more transversal to the practitioner’s cognitive and emotional functioning. They include four groups of perceived practitioner’s qualities: objectivity and organization; psychological flexibility; self-confidence and emotional well-being; and reflexiveness and self-awareness.

Objectivity and organization

Practitioners explicitly referred to the importance of having particular skills of objectivity and organization so they can effectively facilitate the intervention sessions: “The practitioner, or the facilitator, has to be an organized and methodical person in the way they present and organize the program itself, the time, the logistics (Jo Ann, practitioner)”. The practitioner is seen as an organizer of the sessions: “The [practitioner’s] role is (…) to be an organizer (…). To sustain, to move forward, and to organize the session and the ideas with a specific focus” (Carolyn, practitioner).

Objectivity and organization are inferred from many different practitioner’s actions. Parents valued that practitioners speak to them in a straight, clear and simple way “I like people to be objective, to clearly explain what needs to be done and that kind of thing” (Rita, mother). It may imply speaking with expressive gestures or giving clear instructions so that parents can effectively and confidently perform tasks in the group, thus offering parents very specific, concrete and practice-oriented suggestions. Making sequential and guiding questions was also valued both by parents and practitioners as it organizes the discussion and helps to focus on the agenda: “[the practitioner used to say] ‘slow down, let’s go in stages, what’s missing?” (Lauren, grandmother). Finally, actions imposing more explicit limits to the group discussion, such as interrupting, redirecting, “putting an idea in the fridge”, remembering the group’s rules, “bringing the conversation to a close”, “giving someone else the chance to speak”, were also considered important. As practitioner Jo Ann explained, these are good leadership skills: “a good leader has to have this ability to cut off the conversation and say ‘at the end or during the break we can talk a little more about that if you want’, or having the ability to redirect to the focus of the day when the whole group is getting sidetracked.” Being direct and imposing limits were seen as necessary actions both by parents and practitioners, but the way the practitioner performs these actions determines the perceived impact on parents. Some parents felt that when practitioners were more worried about the program’s agenda than the parents’ own needs, showing themselves to be “more focused on the plan than on the people” (Steve, father), the parents felt pressured, rushed, and they missed having more time for free sharing with other parents. They would also feel the program was like a “prison”, and that practitioners were dumping the program “like teachers who have a curriculum to deliver” (Sarah, mother). It was therefore considered extremely important that practitioners impose limits on the discussions in a smooth, subtle way, caring for the relationship with parents and integrating the parents’ goals and needs, in a bidirectional process.

Psychological flexibility

In all the practitioners’ groups, psychological flexibility was identified as a fundamental characteristic of the IYPP facilitators. To effectively moderate an intervention session, flexibility, also referred to as mental agility, is required. Given how the practitioner must attend to several things at the same time, whether the various aspects of the session’s dynamics, the parent’s group, or the practitioners themselves: “this implies a certain mental agility that the facilitator has to have because he or she has to manage different solutions and many things at the same time” (Scott, practitioner). Psychological flexibility was specifically pointed out as useful not only to manage all the aspects of the intervention setting, but also to responding to parents’ needs. Giving parents more time to share experiences in the group and making the necessary adjustments to the sessions were the actions most referred to with respect to psychological flexibility: “[She or he] would have to have great management skills… or even flexibility… to let parents talk and adapt what the program is demanding…” (Violet, practitioner). In fact, tailoring the program to the parents requires that adjustments sometimes be made to the structure and dynamics of the intervention sessions to respond to the parents’ needs. Examples of these are shortening some components in order to dedicate more time to others, choosing the program’s dynamics and video scenes that are more appropriate to each parent group, personalizing exercises to address the specificities of each parent, or even adding extra time/sessions to address parents’ specific issues. For Victoria, a mother who belonged to a group of parents of children with cerebral palsy, having an extra session added in the middle of the program was extremely important, as it represented an opportunity to freely disclose parents’ feelings about parenting a child with special needs. Additionally, both parents and practitioners consider that practitioners have to frequently reformulate and reframe parents’ comments in the sessions in order to tailor the comments to the program’s goals or to the theoretical knowledge, and to make it constructive and useful for the entire group, which requires creativity: “I think there’s a need to be creative in order to generate principles from ideas (Judy, practitioner)”.

Emotional well-being, confidence and belief in the program

Participants described good practitioners as being confident, serene and relaxed. They must be comfortable, relaxed, at ease, in a good mood, or, in short, they must have “a good level of emotional well-being”, as practitioner Violet described. A practitioner’s inner confidence and emotional well-being can be inferred from their calm gestures and physical posture, from the way they smoothly handle the manual and all the program’s materials, and also from predominantly using a smooth, calm but still enthusiastic voice: “to be able to convey enthusiasm but with that [type of] peacefulness (…), with a tone of voice always very calm but not monotone” (Mary, mother). Moreover, practitioners discussed the importance of “being mentally healthy” (Claire, practitioner) and also about having an internal state of “mental availability” (Claire, practitioner) that enables them to deeply engage and commit with parents and with the intervention process, in contrast to conveying stress, tiredness and worries. A mindful state of mind may help practitioners to completely focus on parents and the sessions’ dynamics: “To be really present in that moment. It is about mindfulness… not wandering off to other thoughts and having this ability to focus…” (Isa, practitioner).

In fact, facilitating group sessions with the IYPP is considered to be a demanding task by the practitioners: “It’s not easy at all”, “It’s challenging” (Judy, practitioner). For this reason, practitioners also feel that it is only when firmly committed to the program that they can effectively engage with its implementation: “It is fundamental that practitioners identify with the program, because the enthusiasm comes from there, and only then can we convey the message to others” (Tracey, practitioner). The IYPP thus needs to be “a suit tailored-made to the [practitioners’] individual characteristics” (Vanessa, practitioner). Parents also shared that they perceive and recognize the value that practitioners identify and take ownership of the program: “It makes more sense to us, as mothers, to have practitioners who believe in the program, that they are the program and they breathe the program (Tricia, mother); “If the person also believes and trusts what he/she’s saying, then she/he will also transmit that trust to us” (Sunny, mother).

Reflexiveness and self-awareness

For the most part, it was the practitioners, but also certain parents, who talked about the importance of practitioners being reflexive about the program, the parents, and their children, but also about themselves. Reflexiveness is practiced not only during the session, but also between sessions. The practitioners are permanently engaged in the intervention process because between the intervention sessions they reflect on parents’ comments and experiences in order to deeply appreciate and understand them: “I’m continuously thinking “this father said this, this mother said that”… I think it makes a big difference, so that I don’t leave loose ends from one session to another, and so that I can understand beyond the obvious” (Violet, practitioner). Preparing the program sessions in advance, studying the program, preparing the materials, but also thinking about the specificities of each parent group, are ways to enact reflexiveness, which practitioners consider fundamental in order to be effective: “The better you prepare a session… the better it goes usually. Preparing a session is (…) looking at the parents, looking at the children, at the homework…” (Daisy, practitioner). Reflexiveness can also be practiced in conjunction with the co-facilitator, through peer discussions and debriefings: “the final five minutes when you make an appraisal of what has happened (…), when you reflect on what went wrong, what went well, what we can adjust for the next time…” (Vanessa, practitioner).

Reflecting on oneself, on personal thoughts, feelings or behaviors, is also considered a fundamental task in order to be effective as an IYPP practitioner. For example, stress or anxiety is “something that the practitioner must reflect on and control” (Carolyn, practitioner). In one group of parents, the practitioner’s responsiveness was described as a practitioner’s ability to adequate their own behaviors according to the parents’ needs: “Today is not an easy day for me to be in a good mood (…) because I can see that this parent seems less well than usual, maybe something had happened, let’s take it slowly (Rita, mother)”. In fact, self-reflexiveness or self-awareness has been presented as a lever for the practitioner’s personal change, as practitioner Carolyn explained: “You realize that to perform that role there are aspects of your personality and characteristics that you’ll have to develop and improve”.

Practitioner’s Objective Characteristics

Objective characteristics are the practitioner’s personal qualities that may be checked, observed and objectively known by participants (Beutler et al., 2004), such as gender, age, parenthood status, professional background or experience. Having children, being the same age as parents, coming from a clinical professional background with specific knowledge about children’s behavior, and having considerable experience in working with children and with the IYPP are considered the practitioners’ greatest facilitators of parents’ engagement, particularly at earlier stages of the intervention.

Parents often referred to the importance of personally identifying with their practitioners and sharing some demographic characteristics with them. Although these were not considered necessary conditions to be a good parent support professional, some parents assumed that they would prefer practitioners of approximately the same age and those who also had children:

It’s not a mandatory characteristic, but as I was part of a group with two facilitators who had children, and one of them even had three children like myself, of the same ages… it turned out to be comforting because there’s closeness, like… ‘you know what I’m going through, so it’s easier for you to appreciate my situation’. (Tricia, mother).

Both parents and practitioners also emphasized that practitioners should come from a professional field with specific technical knowledge about child behavior and (parental) relationships because “it makes it easier to understand the scope of the program goals and contents” (Carolyn, practitioner). Coming from a clinical field was particularly valued, and Psychology or other disciplines with knowledge about mental health issues were frequently identified as the most adequate to understand children’s problem behaviors, as compared with more generalist health fields. Moreover, having a considerable amount of experience with group interventions, being “comfortable with families (…), being used to managing groups” (Scott, practitioner), and also being more experienced in facilitating the IYPP were recognized as advantages for effectively implementing this intervention.

However, it was also widely reported by the participants that these objective characteristics are more important in the early stages of the intervention process, with this significance becoming “reversed” as the program progressed: “I feel that as the group goes forward it is no longer important” (Catrin, practitioner). Parents and professionals agreed that more important than objective characteristics and the knowledge of the program are the practitioners’ interpersonal skills, their “professionalism” (Louise, mother) and their personal profile: “More than possessing theoretical knowledge of the program, it is necessary to have a very specific profile to lead the IYPP groups” (Allie, practitioner). The idea of a “personal profile”, one that is more associated with the above-mentioned practitioner’s inferred characteristics, was cited by many participants as being more determinant in the effectiveness of the intervention:

I think it’s simplistic to indicate any of those characteristics as being determinant. I mean, they can be man or woman, of any age… I think it has much more to do with the personality… the care, the posture… how they connect with people. (Steve, father).

Discussion

The present study explored the nature of practitioners’ characteristics and actions that are perceived to influence the implementation of the Incredible Years program administered to parents of children with behavior problems. This was done via an integrated qualitative analysis of parents and practitioners’ perceptions collected during the course of eight focus groups. Previous studies have already researched the role of practitioner or therapist factors in parenting interventions, among other factors (Butler et al., 2020; Koerting et al., 2014; Leitão et al., 2020; Mytton et al., 2014). However, to date, the authors know of no other study exclusively dedicated to investigating the perceptions of those who are centrally engaged in the implementation of a parenting program (i.e., parents and practitioners) with respect to the specific practitioner characteristics and actions that impact the intervention process.

The thematic analysis identified three groups of personal characteristics perceived by parents and practitioners to impact the effective implementation of the Incredible Years parent program with parents of children with behavior problems. These were: inferred interpersonal characteristics (Genuine Interest; Empathy & Warmth; Positive Regard; and Humbleness); inferred intrapersonal characteristics (Objectivity; Flexibility; Well-being; and Reflexiveness) and objective characteristics (Similar age; Being a parent; Clinical professional background; and Professional experience with children and the IYPP). Most of the identified characteristics of effective practitioners in the present study had already been emphasized in previous studies with parenting interventions, such as the ability to create empathy, hope and trust, and being flexible, warm or nonjudgmental, while at the same time having some relevant personal experience and adequate training (Butler et al., 2020; Koerting et al., 2014; Leitão et al., 2020; Mytton et al., 2014). They were also found in the specific literature about the Incredible Years, where the role of the therapist has been widely acknowledged, and where the clinician’s specific knowledge, relationship characteristics and collaborative skills are assumed to be an important determinant of positive parent outcomes (Webster-Stratton, 2020). In fact, most of the actions that were perceived as relevant in this study are contemplated in the Incredible Years model and had correspondence in the IYPP assessment tools, such as the Parent Collaborative Process Checklist (Incredible Years, 2022). This means that many of the practitioner’s characteristics and actions recognized by the study’s participants as having a positive and relevant impact in the intervention are also underscored as important and emphasized in the IYPP, which reinforces the model’s assumptions.

The present study also reveals that certain intrapersonal variables on the part of the practitioner are perceived as relevant in the implementation process although less explicitly referred to by the Incredible Years model, as it is the case of the practitioners’ well-being, self-reflexiveness and genuineness. In this study, both the practitioner’s emotional well-being and confidence expressed in the program sessions were perceived to impact parents’ sense of tranquility and security, and also to enable practitioners to fully commit to the intervention process. Also, self-reflexiveness, or the practitioner’s ability to reflect on oneself, has been identified in this study as a relevant intrapersonal characteristic enhancing the practitioner’s ability to sensitively respond to the parents’ needs and to be open to personal change. The Incredible Years implementation model fosters practitioners’ self-reflexiveness and self-confidence through a variety of supportive procedures, such as ongoing coaching, consultation (Webster-Stratton et al., 2014) and an array of specific protocol checklists which are easily accessible online (Incredible Years, 2022). The program’s author advocates for the importance of practitioners having a formal support network within which they have the opportunity to analyze difficult situations and plan effective strategies (Webster-Stratton, 2012), in order to assure that the program is implemented as intended, i.e., with good levels of fidelity. The study’s results confirm the importance that participants will attribute to the practitioners’ behaviors with respect to program fidelity and to the adherence to the IYPP’s core components. Additionally, they emphasize that the capacity for self-reflection on the part of the IYPP practitioners in terms of revealing their personal skills, beliefs, emotional states or personality may also contribute in an invaluable way to the enhancement of their effectiveness.

Another important theme underlying participant reports was the practitioner’s genuineness. The analysis identified that participants may perceive practitioner’s characteristics and actions as being intimately related, i.e., the practitioners’ personal characteristics are perceived to be conveyed to parents through their specific actions. It was interesting to find that many actions usually attributed to the program model were understood as practitioners’ personal characteristics. This is the reason an integrated framework is proposed where specific practitioners’ actions are understood in relation to specific personal characteristics, instead of being independently analyzed. This recognized relationship between practitioners’ characteristics and actions echoes an important part of Rogerian theory, where a therapist’s technique or particular action serves as “a channel by which the therapist communicates” essential therapeutic conditions, such as empathy or positive regard (Rogers, 1957, p. 102). In fact, Carl Rogers emphasized the link between therapist’s internal states or characteristics and their observable actions, explaining that the therapist should experience a close match between “what is being experienced at the gut level, what is present in awareness, and what is expressed to the client” (Rogers, 1980, p. 116). Rogers called the match or congruence between internal states or characteristics and observable actions genuineness.

The importance of these practitioners’ genuineness or authenticity was also frequently and specifically referred to by participants with respect to the practitioner’s personal match with the IYPP. Participants from this study (both parents and practitioners) valued IYPP practitioners’ identification with the IYPP philosophy and appreciated that they truly upheld the program’s principles and took ownership of the program – “they are and they breathe the program”. Although this characteristic is not quite explicitly considered within the IYPP model, previous study that examines practitioners’ adherence to the IYPP has already pointed out that IYPP group leaders value the notion of fit and belief in the importance of the IYPP (Stern et al., 2008). Wampold (2001) have generally explained that when therapists believe in a treatment, they will practice it with higher levels of tenacity, enthusiasm, hopefulness, and skill. Simon (2006) went even further, hypothesizing that the congruence between the therapist’s personal worldview and the model or program’s worldview may transform the model into an instrument for deeper and more authentic self-expression on the part of the therapist, which will maximize its effectiveness (Simon, 2006).

Finally, both parents and practitioners expressed the notion that the program’s implementation is more influenced by the therapists’ characteristics inferred by their actions than by their objective characteristics. While practitioner’s inferred characteristics and actions seem to be perceived as determinants in the intervention process, objective characteristics, such as age, parenthood status, or professional discipline are perceived to only facilitate parents’ engagement in the intervention, especially during the earliest stages of the process. These results add to the literature in the sense that they may help to better understand the inconsistencies found in previous quantitative studies analyzing the impact of therapists’ personal objective characteristics on the outcomes (Beutler et al., 2004; Blow et al., 2007; Leijten et al., 2018; Leitão et al., 2020; Michelson et al., 2013), suggesting that their impact is dependent on the existence of other important personal variables of the therapists. It also bears noting that the practitioners’ objective characteristics considered to be the most unequivocal and greatest facilitators of parental engagement in the intervention (i.e., having children, coming from a clinical background, and having relevant professional experience) are all characteristics of the practitioners’ personal and professional experience. They all report to the lived and applied experience of the practitioner along their life path, as a person.

To sum up, the concept of the practitioner’s personhood is central to the present study. Parents and professionals participating in our study place a special emphasis on the person of the practitioner, noticing that a practitioner’s personal characteristics will play an influential role in the successful implementation of the IYPP with parents of children with behavior problems. Practitioners’ personal characteristics have not been sufficiently studied in the field of parenting programs although some evidence exists as to the importance of practitioners’ interpersonal qualities (Butler et al., 2020; Koerting et al., 2014; Mytton et al., 2014), professional or training background experiences (Bloomquist et al., 2009; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez et al., 2016; Scott et al., 2008), personal experiences (Koerting et al., 2014), and personality traits (Bloomquist et al., 2009; Lochman et al., 2009). In fact, in the context of delivery of parenting programs, valuing and considering the practitioners’ personal self makes sense, when taking into account that the practitioners’ modelling is one of the professed mechanisms of change for these social learning theory-based programs. Given the fact that parents of children with behavior problems frequently experience negative emotions and resist the intervention (Patterson & Chamberlain, 1994; Hawes & Dadds, 2021), the personal characteristics exhibited by the practitioners may assume an increased value when working with this specific population.

Implications

The IYPP places a stronger emphasis on clinician skill when compared to other parenting programs, encouraging practitioners to work on their collaborative skills through a continued process of training, ongoing consultation and supervision (Webster-Stratton, 2006). The fact that many actions described as relevant by the participants of this study are already presented as essential components of the IYPP’s model serves to reinforce the idea that investing in the practitioners’ ongoing training and support may be crucial in the implementation of the IYPP with parents of children with behavioral problems. Additionally, the present study calls attention to the need to extend the focus beyond practitioners’ professional skills and technical knowledge to examine practitioners’ personal characteristics more closely, such as interpersonal abilities, intrapersonal qualities (like objectivity, psychological flexibility, self-confidence, emotional well-being, genuineness or belief in the program’s model), and even the practitioners’ personal and professional experiences. The present study opens the possibility that encouraging practitioners to self-reflect on their personal characteristics and experiences during the implementation of the IYPP, and working specifically on the interpersonal and intrapersonal qualities that are more amenable to change, may bring additional benefits when working with parents of children with behavior problems.

Moreover, given the existing evidence that practitioners’ personal characteristics impact the use of other parenting programs directed at children’s behavior problems (Bloomquist et al., 2009; Koerting et al., 2014; Lochman et al., 2009), the broader field of parenting programs would probably benefit from including these personal characteristics in their research and implementation practices. Practitioners implementing different parenting programs may derive benefits from reflecting more on how their interpersonal abilities and intrapersonal characteristics are influencing the implementation of the program, and as a result they may want to invest more in their self-care, genuineness, and both their personal and professional development. Also, based on this research, new instruments can be developed in order to promote and assess practitioners’ self-reflexiveness and self-awareness about personal characteristics, experiences, beliefs and emotional states impacting the implementation of parenting programs. These new instruments would advance the knowledge of the field a bit further, and, as they would be focused on practitioners’ characteristics, they would have the advantage of being useful across different parenting programs, and in addition to fidelity, program-focused checklists.

Limitations and Future Directions

The present findings should be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. Only parents who had voluntarily completed the IYPP and who agreed to discuss their experiences in a focus group were included, most of them having been previously contacted by their practitioners to inform them about the study. For these reasons, it is to be expected that these parents would have more positive views about the program, the practitioners and the overall intervention process than those parents who had either been ordered to participate in the program, had dropped out, or had been reached independently of their practitioners and who could add different perspectives on meaningful practitioners’ skills. Also, fathers represented only 17% of the interviewed parents, and the results may, therefore, reflect a predominantly feminine perspective of the theme. The practitioners who volunteered to participate in this study might well have had a greater affinity to the IYPP, and it remains to be seen whether other practitioners, coming from more diverse backgrounds, would have shared similar perspectives. Future research should reach different population participants (e.g., mandated parents, parents who dropped out from the program, fathers, practitioners from different settings, etc.) in order to widen the knowledge about the perspectives coming from different stakeholders in terms of the practitioners’ characteristics and actions that impact the IYPP intervention process.

It is also important to consider that three of the present researchers have been deeply committed to both the research and implementation of the IYPP. This engagement has certainly framed the analysis process towards a perspective that may be more in line with the principles of the Incredible Years model, and it may also have had some impact in facilitating the focus groups, which is an inherent characteristic of the contextualist approach adopted in this qualitative study. There were some practitioners with whom the research team had previous academic, research-based or professional relationships, who may have felt more willing to share experiences compatible with the IYPP model’s assumptions. The research team has tried to reach a broad variety of participants’ perceptions and meanings by involving a fourth researcher in the analysis process who had no experience in implementing and researching the Incredible Years programs, and also by formulating questions in order to engage the participants in a more experiential and personal sharing during the focus groups (e.g., “How did it feel for you?”; “We’re interested in your real experience”; “We welcome your suggestions and criticisms, be free to share your personal experience”). Moreover, because FGs involved discussions of study questions among participants and because it did not fall within the scope of this study to analyze the differences in perceptions between parents and professionals, nor between parents/professionals with different backgrounds, the current analysis reflects more shared than individualized experiences and elaborates on similarities rather than differences. Future studies may, however, focus on comparing the perceptions of parents and practitioners regarding the role of the IYPP practitioner. Finally, the authors are aware that the results do not represent the whole relational dimension as they focus solely on the practitioner’s contribution to the process. The bidirectional effects and the impact of the intervention process on the practitioner were excluded from the analysis, although the authors do here acknowledge their importance.

The present qualitative study allowed for a deeper and more valid understanding of the perceived role of the practitioner in the implementation of the IYPP, under a contextualist epistemological paradigm, where results were trustworthy to the participants’ meanings and to the researchers’ method of analysis. This integrative analysis enabled the creation of a proposed unified framework to better understand the perceived relationships between characteristics and actions. The authors do not intend this conceptual framework to be tight and determinative, but instead flexible and illustrative. Practitioners’ actions were clustered in different characteristics for organizational purposes, attending to the meanings more expressively referred to by the participants, but considerable overlap may exist, with some actions relating to more than one characteristic. Being an exploratory study, this research opens new possibilities for future research and for the development of scientific knowledge. More qualitative research should be pursued in future studies, in order to deepen the analysis of perceptions about the role of the practitioner in the implementation of parenting programs, and to achieve a richer understanding of the complex dynamics of the relational processes presented in parenting intervention programs. Moreover, the practitioners’ characteristics and actions identified in the present study can inspire the development of new specific assessment measures, and can be used as potential variables in future studies. Based on the present research, quantitative studies can test, for example, whether there is a statistically significant relationship between practitioners’ characteristics/actions and different intervention outcomes, or whether they can assess the conceptual relationship proposed in this study between each characteristic and the correspondent actions.

Conclusions

The present qualitative study was the first to more deeply explore the perceptions of parents and professionals on the extent to which a practitioners’ specific characteristics and actions might influence the implementation of the IYPP with parents of children with behavioral problems. The results from this study seem to place a special emphasis on the importance of the person within the IYPP professional. The practitioners’ personal characteristics, such as their interpersonal skills, intrapersonal resources and certain objective qualities, are perceived by the participants as able to underpin the practitioner’s actions and to play an important role in the delivery of the IYPP. And while most of the characteristics and actions that were perceived as relevant in this study are contemplated in the Incredible Years model, the practitioners’ intrapersonal well-being, self-reflexiveness and genuineness in relation to themselves and to the IYPP emerged as characteristics which may merit further attention and research.

References

American Psychological Association [APA], Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice. (2005). Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Psychologist, 61(4), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271.

Barlow, J., Smailagic, N., Huband, N., Roloff, V., & Bennett, C. (2014). Group-based parent training programmes for improving parental psychosocial health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 17(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002020.pub4.

Berkel, C., Mauricio, A. M., Schoenfelder, E., & Sandler, I. N. (2011). Putting the pieces together: An integrated model of program implementation. Prevention Science, 12(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-010-0186-1.

Berlyn C., Wise S., & Soriano G. (2008). Engaging fathers in child and family services (Occasional Paper No.22). Australian Government, Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, Canberra, Australia. https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/op22.pdf.

Beutler, L. E., Malik, M. L., Alimohamed, S., Harwood, T. M., Talebi, H., Noble, S., & Wong. E. (2004). Therapist variables. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (pp. 227–306).

Bloomquist, M. L., Horowitz, J. L., August, G. J., Lee, C.-Y. S., Realmuto, G. M., & Klimes-Dougan, B. (2009). Understanding parent participation in a going-to-scale implementation trial of the early risers conduct problems prevention program. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18, 710–718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9277-7.

Blow, A. J., Sprenkle, D. H., & Davis, S. D. (2007). Is who delivers the treatment more important than the treatment itself? The role of the therapist in common factors. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 33(3), 298–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00029.x.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

Buchanan-Pascall, S., Gray, K. M., Gordon, M., & Melvin, G. A. (2018). Systematic review and meta-analysis of parent group interventions for primary school children aged 4-12 years with externalizing and/or internalizing problems. Child Psychiatry Human Development, 49(2), 244–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-017-0745-9.

Butler, J., Gregg, L., Calam, R., & Wittkowski, A. (2020). Parents’ perceptions and experiences of parenting programmes: A systematic review and metasynthesis of the qualitative literature. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(2), 176–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-019-00307-y.

Carr, A. (2019). Family therapy and systemic interventions for child-focused problems: The current evidence base. Journal of Family Therapy, 41(2), 153–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12226.

Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4, 50 https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0.

Eames, C., Daley, D., Hutchings, J., Whitaker, C. J., Jones, K., Hughes, J. C., & Bywater, T. (2009). Treatment fidelity as a predictor of behavior change in parents attending group-based parent training. Child: Care, Health and Development, 35(5), 603–612. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00975.x.

Eames, C., Daley, D., Hutchings, J., Whitaker, C. J., Bywater, T., Jones, K., & Hughes, J. C. (2010). The impact of group leaders’ behaviour on parents acquisition of key parenting skills during parent training. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48, 1221–1226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.07.011.

Fixsen, D., Naoom, S., Blase, K., Friedman, R., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network. https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/resources/implementation-research-synthesis-literature.

Furlong, M., & McGilloway, S. (2014). Barriers and facilitators to implementing evidence-based parenting programs in disadvantaged settings: A qualitative study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(6), 1809–1818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9984-6.

Furlong, M., McGilloway, S., Bywater, T., Hutchings, J., Smith, S. M., & Donnelly, M. (2012). Behavioural and cognitive-behavioural group-based parenting programmes for early-onset conduct problems in children aged 3 to 12 years. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 8(1), 1–239. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008225.pub2.

Garcia, A. R., DeNard, C., Ohene, S., Morones, S. M., & Connaughton, C. (2018). “I am more than my past”: Parents’ attitudes and perceptions of the Positive Parenting Program in Child Welfare. Children and Youth Services Review, 88, 286–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.03.023.

Gardner, F., Leijten, P., Mann, J., Landau, S., Harris, V., Beecham, J., Bonin, E. M., Hutchings, J., & Scott, S. (2017). Could scale-up of parenting programmes improve child disruptive behaviour and reduce social inequalities? Using individual participant data meta-analysis to establish for whom programmes are effective and cost-effective. NIHR Journals Library. https://doi.org/10.3310/phr05100.

Garland, A. F., Hawley, K. M., Brookman-Frazee, L., & Hurlburt, M. S. (2008). Identifying common elements of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children’s disruptive behavior problems. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(5), 505–514. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816765c2.

Hawes, D. J., & Dadds, M. R. (2021). Practitioner review: Parenting interventions for child conduct problems: Reconceptualising resistance to change. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13378.