Abstract

Despite intensive treatment, adolescents discharged from residential treatment (RT) often do not maintain treatment gains in the community. Providing support and education to caregivers through parent training may ameliorate the loss of treatment gains. Successful parent training programs have been delivered to this population; however, these interventions were delivered in-person, posing significant barriers affecting reach, access, and engagement. A convergent mixed methods design was used to assess the acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of a web-based parent training in a sample of parents (N = 20) with adolescents admitted to RT. Parents completed two interviews and an end-of-program survey. Parents completed at least 80% of the assigned modules and felt that PW was easy to use and that the features facilitated learning. Parents reported practicing the skills in their daily lives and found it beneficial to have a partner to practice with. Consistent with previous studies, parents perceived the delivery method as a strength because the web-based delivery circumvented multiple known barriers to in-person interventions. A large subset of parents related to the scenarios, while a small subset of parents felt the modules were challenging to relate to because of the severity of their adolescent’s mental health challenges. Overall, findings indicate that web-based parent training programs may be an acceptable, appropriate, and feasible adjuvant evidence-based support. However, tailoring the intervention content is necessary to create a more relatable intervention that captures the breadth and severity of mental health challenges adolescents in RT face.

Highlights

-

Web-based delivery increases access, reach, and engagement.

-

Parents reported practicing logical consequences, effective communication, and active listening with their adolescent.

-

Parent training while the adolescent was in RT allowed parents the time and space to engage with the material.

-

Parent training needs to be tailored to address the breadth and severity of mental health challenges in the RT setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Residential treatment (RT) represents one of the most restrictive and intensive settings for emotional and behavioral healthcare for children and adolescents presenting with disruptive behaviors, such as aggression, delinquency, and hyperactivity (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2018; Sternberg et al., 2013). This paper focuses on adolescents aged 11 to 17, who account for nearly 75% of RT admissions in the United States (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2015). RT facilities are community or campus-based mental health facilities for 1) adolescents who have not responded to outpatient treatment, 2) adolescents whose educational needs have not been met in their local schools, or 3) adolescents who need continued and intensive treatment after an inpatient psychiatric admission (AACAP 2016). Despite intensive therapy and milieu management, a pervasive challenge in this population is maintaining treatment gains in the community (Ringle et al., 2012; Yampolskaya et al., 2014). The loss of treatment gains can be characterized by factors such as the re-emergence of disruptive behaviors, poor academic performance, or association with negative peers (Ringle et al., 2012; Yampolskaya et al., 2014). The consequences of treatment gain loss are severe and include readmissions to psychiatric settings (RT, hospital), justice system involvement, and child welfare involvement (Frensch & Cameron 2002; Ringle et al., 2012; Yampolskaya et al., 2014).

Parent Training and Treatment Gain Maintenance

A home environment fraught with family disorganization, conflict, and disruption can impair treatment gain maintenance (Sunseri 2005; Sunseri 2019). In the home, caregivers (e.g., biological, adoptive, foster, kin; hereafter referred to as parents) may have inadequate support and limited access to strategies to manage this high-stress caregiving scenario (Sheidow et al., 2014). A second factor is that treatment plans may focus on the presenting disruptive behaviors with limited attention on preparing the family and adolescent for discharge (Herbell & Breitenstein, 2020). Thus, families may feel unprepared for discharge, and adolescents may enter the same unchanged home environment (Ringle et al., 2015). Effective treatment plans should fully address the underlying trauma driving disruptive behaviors (Bryson et al., 2017). Disruptive behaviors are one of the most prevalent challenges in providing care to adolescents with trauma histories (Briggs et al., 2012). Bryson & colleagues (2017) conducted a systematic review to determine the most effective strategies for implementing trauma-informed care (TIC) in RT settings. They found that there are five essential factors for TIC implementation, including 1) prioritizing TIC among senior leaders, 2) training staff on the effects of trauma and alternatives to restraint, 3) addressing families’ priorities and needs, 4) engaging in continuous quality improvement, and 5) aligning TIC with policy (Bryson et al., 2017).

One method of addressing families’ priorities and needs is teaching parents relational, psychoeducational, and behavior management strategies through behavioral parent training (hereafter referred to as parent training). Parent training programs are evidence-based approaches for ameliorating disruptive behaviors (Michelson et al., 2013; Solomon et al., 2017; Uretsky & Hoffman, 2017). Parent training programs effectively reduce behavioral problems, including oppositional and conduct problems in community-dwelling (Michelson et al., 2013) and foster children (Akin et al. 2017; Solomon et al., 2017). Parent training programs teach effective behavior management strategies and promote positive parent-child interactions, effective communication, and consistent discipline (Kaminski et al., 2008). Additional positive outcomes associated with parent training include reductions in parental stress (Carr et al., 2017) and improvements in parenting competence and positive parenting practices (Daley et al. 2014).

Prior Parent Training Programs in RT

Although parent training programs have been regarded as a promising strengths-based approach to engaging families in RT (Maltais et al., 2019), few have tested parent training programs with parents in the RT setting. Those that have described delivering in-person parent training to RT staff rather than parents (Parris et al., 2015; Parry et al., 2021; Silva et al., 2016). One notable intervention with a parent training component in the RT setting is On the Way Home (Trout et al., 2012). This year-long aftercare program consists of Check & Connect (Christenson et al., 1999), Common Sense Parenting (Burke et al., 2006), and homework support (Trout et al., 2012). Findings indicated that 91% of children in the On the Way Home condition remained in the community post-discharge compared to 65% of children in the control condition (Trout et al., 2012). The authors mention that limitations included contamination between conditions and a high attrition rate (32% post-intervention), which may have introduced bias in estimating treatment effectiveness (Trout et al., 2019). Further, 99% of the sample came from one RT facility (i.e., Boystown) that implements a distinct care model (i.e., Teaching Family Home), which may limit the generalizability of findings to other RT facilities (Trout et al., 2019). In addition, On the Way Home was delivered in-person to parents within 60 miles of the RT facility. While the intervention was effective, the in-person delivery model may pose barriers to access and engagement (Baker et al., 2011; Duppong-Hurley et al., 2016; Garvey et al., 2006).

A second parenting intervention that has been used with the RT population, Ringle & colleagues (2015) blended intervention, consists of RT combined with aftercare services for children at risk of entering the juvenile justice system. A key component of this model is an in-home family consultant working with families beginning at RT admission through three months post-discharge (Ringle et al., 2015). The parenting component of the intervention includes promoting supervision and monitoring, consistency with discipline, healthy relationships with family and peers, academic success, and developing a support network (Ringle et al., 2015). Results of the study indicate that compared to children in the control condition (i.e., treatment as usual), children that received the blended intervention improved in inattention, internalizing, and externalizing symptoms, and parents engaged in more effective parenting practices (Ringle et al., 2015).

Web-Based Approaches may Increase Reach, Engagement, and Accessibility

Previous studies provide promising evidence that parent training may promote the maintenance of treatment gains in the community. However, both interventions were delivered in-person (Ringle et al., 2015; Trout et al., 2012), which may pose significant barriers (e.g., time, scheduling, transportation) to parent participation, including low engagement, high cost, and geographic constraints. Participation and attendance are essential to the success of parent training, yet, there is often a high level of attrition with in-person parent training, some of which is attributed to the inconvenience of scheduling weekly appointments when the parent does not have access to the necessary resources such as transportation, time, or childcare to attend in-person parent training (Baker et al., 2011; Chacko et al., 2016; Duppong-Hurley et al., 2016; Garvey et al., 2006). Specific to RT, some parents reside significant distances from facilities (sometimes counties or even states away), reducing their ability to be involved in their adolescents’ care (Huefner et al., 2015). These barriers have been amplified with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, underscoring the potential usefulness of web-based delivery (Racine et al., 2020).

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that web-based parent training programs have moderate effects on adolescent behavior problems (Baumel et al., 2016, 2017). Included in the review was Parenting Wisely (PW), originally developed for parents with court-involved adolescents aged 11–17 with moderate externalizing behaviors (Gordon & Stanar, 2003). PW is guided by a social-learning perspective in which parents are viewed as change agents and parenting behaviors mediate adolescent behavior problems (Patterson 1982; Patterson & Reid, 1970). A component of the social-learning perspective is the Coercion Model, which posits that adolescent behavior problems are enmeshed in the family unit and are shaped by inconsistent and harsh discipline (Capaldi et al., 1997; Patterson et al., 1998). When adolescents exhibit behavior problems, a coercive relationship (i.e., aversive behavior to control the adolescent) can develop between parents and adolescents, reinforcing the problem behavior (Capaldi et al., 1997; Patterson et al., 1998). The objective of PW is to attenuate adolescent behavior problems by replacing coercive parenting practices with effective parenting practices such as warmth, praise, effective modeling of behavior, supervision, and consistent boundaries. PW targets parenting practices by employing the social learning theory principles, modeling, and mastery experience. PW uses modeling in videos depicting different parenting practices and corresponding consequences. Mastery is reinforced as parents are encouraged to practice skills daily.

PW has been tested in racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse samples using multiple study designs, including open trials (Cefai et al., 2010; Mello et al., 2019; O’Neill & Woodward, 2002) and three RCTs (Becker et al., 2021a; Kacir & Gordon, 2000; Segal et al., 2003). PW targets parenting practices to reduce adolescent externalizing behaviors with small to medium effects (Cohen’s d = 0.20–0.46; Feil et al., 2011; Kacir & Gordon, 2000; Segal et al., 2003). PW was one of three interventions implemented in North Carolina to reduce adolescent violence (Smokowski et al., 2018). Compared to no treatment, parents who received PW (n = 347) reported increases in parenting confidence (β = 0.30, p = 0.004) and parental self-efficacy (β = 0.30, p = 0.01) and decreases in parent-adolescent conflict (β = −0.30, p = 0.001), adolescent aggression (β = −0.27, p = 0.001), and violent behaviors (β = −0.22, p = 0.008) between baseline and six months follow-up (Smokowski et al. 2018).

While there are numerous efficacious parent training programs (Zarakoviti et al., 2021), PW was selected for evaluation primarily because its web-based components may facilitate the engagement of a hard-to-reach and difficult-to-engage population. Second, our selection of parent training programs was limited to programs designed for adolescents because adolescents aged 11 to 17 comprise over 75% of the RT population (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2015). PW was designed for a population of court-involved adolescents with similarities (e.g., delinquency, aggression) to the RT population (Gordon, 2000). Third, previous studies suggest that parents prioritize engaging and accessible (i.e., web-based, non-clinical, strengths-based) programming that provides support during the adolescents’ transition to the community (Herbell et al., 2020). Parent training programs are not intended to take the place of high-intensity programming and instead should be viewed as adjuvant support to standard programming.

The Current Study

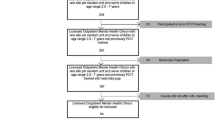

The goal of the current study was to assess the acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of a PW in a pilot sample (N = 20) of parents with adolescents currently residing in a US-based RT facility or who recently transitioned to the community from RT. Acceptability refers to the perception that PW is agreeable or satisfactory to parents (Proctor et al., 2011). Appropriateness refers to parents’ perceptions that PW is relevant or compatible with the population (Proctor et al., 2011). Feasibility refers to the utility of PW and the likeliness of transporting PW to the RT setting (Proctor et al., 2011). The primary hypothesis was that PW would be acceptable, appropriate, and feasible to parents, as indicated by qualitative and quantitative feedback. Acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility were the focus of this study because these outcomes serve as indicators of implementation success, proximal indicators of the implementation process, and intermediate outcomes of treatment effectiveness (Proctor et al., 2011). Further, focusing on implementation outcomes at this pre-intervention adoption stage is critical for successfully transporting parent training programs in the RT setting (Proctor et al., 2011).

Methods

Research Design Overview

A convergent mixed methods design was used to assess PW’s acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility in a sample of parents (N = 20) with adolescents admitted to RT. The hallmark of a convergent design is an equal emphasis on qualitative and quantitative data in which the qualitative and quantitative datasets are analyzed independently, merged, and interpreted together (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). This approach allows an in-depth understanding of how parents’ perceptions of PW converged and diverged. Study procedures were conducted virtually, including recruitment, screening, informed consent, intervention delivery, and data collection.

Researcher Description

The study was designed and conducted by a team of Caucasian female researchers from the United States. Qualifications of team members included expertise in parent training, RT, psychiatry, and child welfare, with previous experience conducting quantitative and qualitative research with parents with adolescents in RT. Relationships between the study team and the community (i.e., Facebook groups) were established in previous studies.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in full conformity with the principles outlined in The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research of the US National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research and codified in 45 CFR Part 46 and the ICH E6; 62 Federal Regulations 25691 (1997). The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board (IRB) served as the IRB for this study. The IRB reviewed and approved the study protocol, protocol amendments, informed consent documents, recruitment and data collection materials, and protections for participants. Potential risks in the study were coercion and the actual or perceived loss of confidentiality. Upon contacting the study team, potential participants were provided with detailed verbal and written (i.e., emailed) descriptions of the study, including procedures, risks, benefits, and compensation. Potential participants were encouraged to consider their participation in the study before proceeding with informed consent. Consent forms stated that participation was voluntary and that participation in the study would not impact the parents’ or adolescents’ ability to access services or receive care. We did not partner with RT facilities for this study or collect information on which facilities adolescents were admitted. Participants were informed verbally and in the informed consent form that they may withdraw from the study at any point. All study records were coded with identification numbers to protect confidentiality, and the key linking names with numbers were kept in a separate location under the PI’s control. Names, places, or any other identifying information were redacted from transcripts.

Procedures

Parents were asked to participate in four activities for this study. First, parents attended an enrollment phone meeting where parents provided verbal consent, completed a demographic questionnaire, and received instructions on PW. Parents received verbal instructions during the enrollment meeting and written instructions via email after the enrollment meeting. Parents were provided a schedule for completing the PW modules over the five-week intervention period. Parents received weekly email or text message reminders to complete the PW modules and attend their scheduled interviews. Consistent with the convergent mixed methods approach, qualitative and quantitative data were collected in parallel; however, the analysis of one data set did not inform the other (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Parents completed mid-session and final individual interviews at weeks three and five post-enrollment (i.e., post-test). Parents who completed the interviews were invited to complete an end-of-program survey.

Participant Recruitment

From March 2020 to July 2020, the study team recruited parents from Facebook. Facebook was selected as the recruitment method because previous research suggests that parents with adolescents in RT are often disconnected from other parents (Herbell et al., 2020). Because of this isolation, parents use social media to connect with and support other parents in similar circumstances (Herbell et al., 2020). To facilitate Facebook recruitment, the study team created a Facebook page containing relevant information about the research study’s purpose, eligibility, and contact information to recruit via Facebook. The research team utilized paid advertising on Facebook to recruit participants. The research team also privately messaged Facebook group moderators asking permission to post information about the study in private groups that served the target population. Private groups were identified based on partnerships from previous studies and using the search function within Facebook to find groups focused on parents of adolescents with mental health challenges.

Once permission was obtained from the group moderator, the study team posted the recruitment flyer in the group. The same sampling method, snowball sampling, was used for the study’s quantitative and qualitative components. Group moderators and participants were encouraged to “tag” on Facebook or invite other parents to participate in the study. Interested parents were directed on the study flyer to contact the study team to determine eligibility and learn more about the study. Eligibility criteria were the same for the quantitative and qualitative portions of the study. To participate, potential participants identified as a parent or guardian to an adolescent between the ages of 11 to 18 who, at the time of the study, resided in a US-based RT facility or were discharged from an RT facility in the past year. To participate, parents needed to be an adult (aged > 18), reside in the United States, speak English, and have access to a smartphone, tablet, laptop, or desktop computer with internet access. Parents who completed the interviews were invited to complete the end-of-program survey. Parents were compensated with a $10 gift card for the mid-session interview, a $25 gift card for the final interview, and a $10 gift card for the end-of-program survey.

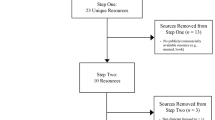

Participants and Sample Description

Data in this study were only collected from parent participants. Thirty parents contacted the study team and were screened, of which 28 were eligible (93% of screened). One parent was ineligible because of their child’s age (9-year-old), and the other was ineligible because their child was not currently admitted to RT, nor did they have a history of RT. Twenty-four parents provided informed consent and enrolled in the study (80% of screened, 86% of eligible); however, four parents (17%) were lost to follow-up. The study team verified that the four parents never logged into PW. Twenty parents confirmed participation and completed all study procedures. Please see Table 1 for a complete description of the sample.

Intervention

Parents were assigned two modules in PW per week for five weeks. PW consists of ten modules that portray common scenarios families go through (e.g., curfew, sibling conflict, finding drugs) (Gordon 2005). The skills in PW include praise, I-messages, contracting and points systems, supervision and monitoring, active listening, and clear communication of behavioral expectations (Gordon 2005). Parents view video scenarios of common problems families experience to reinforce effective parenting behaviors. After viewing the vignette, parents select one of three responses based on how they would respond to the scenario. The three responses vary in behavior management effectiveness. The selected response is portrayed in a second video scenario. Along with the videos are questions and answers with critiques. The final PW module culminates in a composite skills practice that summarizes each video scenario and applicable skills.

Measures

Demographic Survey

Parents completed an investigator-developed demographic questionnaire at enrollment that assessed parent and adolescent demographics. The demographic questionnaire was administered through REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; Harris et al., 2009). Parent demographics included age, race, and education, and adolescent demographics included age, gender, current residence (e.g., RT, home), and expected discharge destination.

Interviews

Parents completed two individual interviews in this study (i.e., mid-session and final). The mid-session interview (~ 30 min; 3-weeks post-enrollment) assessed acceptability by asking parents about their initial impressions of PW, including their satisfaction with the content, timing, and delivery model. The final interview (~60 min; 5-weeks post-enrollment) assessed appropriateness and feasibility by asking parents about the relatability and representativeness of PW’s content. Study investigators developed semi-structured open-ended interview guides to ensure the adequacy and quality of data. To create the interview guides, the study investigators discussed the conceptualization of the implementation outcomes and developed questions that tapped into acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility. The interview questions corresponded to the following topical areas: a) skills learned, b) strengths and weaknesses of PW, c) satisfaction with timing and mode of delivery; d) material appeal and session content, e) applicability to families in RT, and f) barriers to participation. Interviews were conducted by the PI, who is experienced in qualitative interviewing and has received formal training in qualitative methods. After welcoming parents to the interview, the interviewer explained the purpose of the interview. The interviews were collaborative in which parents were encouraged to speak freely about their perceptions. Open-ended questions followed by probes were used to encourage elaboration with limited influence by the interviewer. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

End-of-Program Survey

Modeled after an end-of-program survey that researchers designed to evaluate the feasibility of a web-based adaptation of the Chicago Parent Program (Breitenstein & Gross, 2013), this study’s end-of-program survey assessed acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility. Specifically, parents were asked to report the percentage of weekly content of the PW session they completed and the estimated time per week parents spent using PW (Breitenstein & Gross, 2013). The survey also contained items that assessed how easy PW was to use (very easy, a little bit easy, not at all easy) and how clear the content was (very clear, a little bit clear, not at all clear). Third, the end-of-program survey assessed appropriateness by asking parents to rate the videos and reflection questions (very helpful, a little bit helpful, not at all helpful) (Breitenstein & Gross, 2013).

Data analysis

Quantitative Data

Quantitative data in this study were derived from the self-report demographic questionnaire and the end-of-program survey. The end-of-program survey assessed usage metrics (e.g., time to complete modules) and whether parents perceived PW as helpful, clear, and easy to use. These data were analyzed in SPSS and checked for completeness. Descriptive statistics (e.g., frequencies, percentages) were used to describe the study sample (see Table 1) and quantitatively describe parents’ perceptions of PW.

Qualitative Data

Interviews allowed the research team to understand more detailed insights into specific aspects of PW that were perceived as acceptable, appropriate, and feasible. Qualitative data sources in this study included the mid-session and final individual interviews. We selected conventional content analysis as the qualitative data analysis strategy due to the inductive nature of the study (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Content analysis aims to provide a thick, rich description of the phenomena of interest using the parent’s own words (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Three study team members assisted in analyzing the qualitative data in NVIVO. First, names, places, and other identifying characteristics were redacted from the transcripts to maintain confidentiality. Second, transcripts were read individually by members of the study team. Next, two members individually coded line-by-line one transcript and met to share their findings. They discussed codes and linkages which provided the basis of the coding scheme. This individual line-by-line coding and meeting process was repeated three times when there was uniformity in the coding. Members of the study team engaged in memoing, an analytic strategy in which biases, thoughts, and insights into the data were recorded and shared with other team members to encourage transparency. While memoing is often used in a grounded theory, memoing enhances the rigor of all qualitative approaches (Birks et al., 2008). Memoing is a reflexive strategy that allows researchers to understand how their own perceptions and experiences shape the interpretation of data (Glaser 1978). In this study, we used memoing to track and comment on the inter-relationships of codes. Once the transcripts were coded, team members met to share their insights via memos and collapsed codes into conceptual categories. The coding, discussing, and collapsing process continued until all transcripts were reviewed and data saturation was achieved.

Integration of the Data

Quantitative and qualitative datasets were analyzed independently; however, to interpret the data, the datasets were merged and interpreted together (Creswell & Creswell 2018). Following the guidance by Creswell and Creswell (2018), we identified content areas in both data sets and proceeded to compare and synthesize the content areas. To interpret the merged results, the study team summarized the separate results and discussed how the datasets were related to produce a complete understanding of the acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of PW in the RT setting.

Results

Quantitative Findings Overview

First, parents were asked to rate PW’s ease of use and clarity of the content to evaluate the acceptability. Seventy five percent of parents (n = 15) felt that PW was “very easy to use”, 20% (n = 4) found PW “a little easy to use”, and 5% (n = 1) found PW “not easy to use”. For clarity of content 85% (n = 17) felt the content was “very clear” and 15% (n = 3) felt the content was “a little bit clear”. Second, parents were asked to rate how helpful the components (e.g., videos, reflection questions) of PW were to evaluate appropriateness. Sixty percent of parents (n = 12) felt the videos were “very helpful,” and 40% of parents (n = 8) felt the videos were “a little bit helpful.” Seventy percent of parents (n = 14) felt the reflection questions were “very helpful,” 25% (n = 5) felt they were “a little bit helpful,” and 5% (n = 1) felt they were “not helpful.” To evaluate feasibility, the study team tracked rates of study withdrawal, and participants completed survey questions on time spent completing modules and module completion. Twenty-four parents enrolled in the study; however, four were lost to follow-up. The study team verified that the four parents lost to follow-up never logged into PW. According to the end-of-program survey, 90% of parents (n = 18) spent 30 min or less per week completing modules. Ten percent (n = 2) reported spending 30–60 min per week on modules. All treatment completers (N = 20) reported completing at least 80% of the assigned modules.

Qualitative Findings Overview

Conventional content analysis of mid-session and final interviews resulted in seven categories and three themes: (1) Learning the Skills, (2) Delivery Mode and Timing of PW, and (3) Satisfaction with Content and Scenarios. Table 2 outlines the themes and corresponding categories, codes, and exemplar quotes from the data analysis.

Learning the Skills

Parent #7 felt that there were “takeaways” in each module. She shared that when her son acted out, his phone was taken away, but she realized through PW that taking a phone away is not a logical consequence and does not result in lasting behavior change. She said:

If my son acts up, everyone’s quick just to say take away the cell phone, but not having an actual consequence. Like this is your warning. If you’re going to do this, you’re going to lose that. I even took some notes on that one because I feel like that one I probably learned the most from.

Parent #8 also had a revelation when reviewing the PW modules with her partner about clear expectations regarding curfew: “[curfew] is one that we’re coming into. I’m like, “Well, what time is his curfew?” “Well, I didn’t give him one.” Well, how’s he supposed to know what time to come home?” According to parent #18, the way the content was presented was helpful:

[The skills are] becoming ingrained. I’ve already had this awareness, and I’ve already started trying to do some of the techniques, but I had kind of read them in books before and nothing was as clear-cut as these modules. I think since I’ve been doing the modules, I’ve used the I messages a ton, the praise with the touch and get close, all those things. I’ve just been doing them regularly.

Practicing Communication

While it was not a requirement for parents to practice the PW skills in their daily lives, several parents reported naturally implementing the strategies. Parents reported that effective communication was the most commonly practiced PW skill. For example, parent #15 was frustrated that her adolescent struggled to keep up with online school and was\ dishonest about completing homework. Parent #15 reviewed the PW module on homework where effective communication was used and shared an insight that she had: “maybe I should go back and try and not yell at her as the first thing. The way that [PW] approached connecting with the child and trying to work to a mutual acceptance was helpful.” Similarly, parent #8 reported using PW modules intermittently as situations arose that required effective communication with her daughter in RT. She said:

Something would come up and I would be like, ‘I need to go hit a module, and just reset. And, to think about this again.’ And then, I would come back, and I would point out [to my daughter], ‘I am keeping my voice very calm with you right now.’

Parent #18 shared that phone calls with her daughter in RT were historically reactive. She reports that she successfully utilized active listening during a phone call with her daughter:

I started trying to just listen more, just be more of an active listener and try to validate some of the things that she has been saying. And yesterday…I just validated what she was saying to me and then I also told her that I also take responsibility for her fearful actions because of the way I was acting. And then she said, “Mom, I could tell that you’re really trying hard and you seem to have really changed since I’ve left the house.”

Parent Alignment

While we only enrolled one parent per household, several parents shared with us that they invited their partner to complete modules with them or talk about the PW strategies and ways to implement the strategies in their households. For example, parent #17 shared PW with her husband and practiced communication skills in a family meeting:

We had a family meeting to talk about some rules. And if we hadn’t been watching the modules, I think one of us could’ve taken something personally…because I remember, at one point, we were all talking and my husband actually pulled back and said, “Hang on. Let’s just have one person talk at a time.”…We even said, “Remember what the module said about this?” If I had done it by myself, I would’ve spent so much time trying to explain it to him and then felt isolated trying to run a family meeting or something. It was just so much better.

Similarly, parent #19 shared that she and her partner completed several modules together. Parent #19 shared that even though certain challenges did not apply to her adolescent (e.g., getting out of bed), the content was still helpful to her and her partner. Parent #19 and her partner adopted a conversational approach to completing the modules:

Before we would listen to the answers to the questions, we would talk about them, apply them to what was going on in our lives. And then we did the quizzes together, which some of them we even got wrong because I appreciate the answers are a little bit tricky on some of them.

Parent #16 believed her husband was likely the parent who “needs [PW] the most.” However, she shared that he is reluctant to engage in parenting-focused programming. She said:

My husband and I have very different parenting styles and that is addressed throughout the modules. Although my husband would probably learn from it, I can’t picture him sitting down and doing it. And so I don’t know that the parent that truly needs it is going to be the one that’s actually out doing it.

Parent #20 also struggled with getting her husband on board with treatment and parenting strategies:

Everyone talks about the family support or the family changing is so important. But the problem that I specifically run into in my family is that I agree with that and I’m on board, but my husband is not. I tried my best to convince him otherwise, but that’s where he is. And right or wrong, I can’t do anything about how he’s going to choose to do things. But I often feel like, “okay, now what am I supposed to do?” because everything is directed at the parents being a team.

Delivery Mode and Timing of PW

The Role of Prevention

Multiple parents shared that PW would be useful in the school-aged years. Parent #18 shared: “I wish every parent was required to take this course. I wish I had had it when my child was maybe eight or ten to try to implement these techniques that I had really no idea about.” Parents felt that if certain risk factors were presenting early on, that early intervention was critical. Parent #2 said:

This program needs to be used in the beginning when they are identified as having markers that show that they are at risk for mental and behavioral health issues when they are assessed to be at risk for substance use and juvenile justice issues; this should be implemented immediately.

Parents shared that their adolescent had been in therapy for many years by the time they reached RT and the ideal time for skill development was before adolescence. Parent #4 said:

Between five and twelve is when we could have gotten skills when we were asking for help when we were seeking resources when you’re trying to do stuff before he got so far gone that I don’t think there was any coming back from it. I wish [PW] started at a lower level of care.

Timing of Delivery

The study sample consisted of parents with adolescents currently in RT at the time of the study (n = 10) and parents with adolescents living outside of RT (n = 10). We asked parents about the best time to complete PW (e.g., at admission, during discharge). All parents reported that completing PW was far more feasible while the adolescent was physically residing in RT. Parents described that when their adolescent was home, they were in ‘crisis mode,’ so engaging in programs was challenging. Parent #2 described her home environment while her son was home:

Imagine a household in crisis where the parents are fighting and the kids are a mess and they’re trying to just get dinner on the table. And I couldn’t even get a shower while my kid was home. I wasn’t sleeping more than two hours a night. I had one foot on the floor, just waiting for his doorbell to go off or his window alarms.

Parent #4 provided similar feedback regarding the appropriate time to begin programming while an adolescent is in RT:

I think for us, like a month after he left we maybe could have addressed that. Right away, no way, because, and you know that all of the stuff that you’ve neglected while you’re caring for this child with such intensity tends to come out as illness or extreme stress in you as the parent. But we could have done it once we actually believed that he was safe and once we started to build a new routine, that would have been okay. I think right before they’re starting to come home is too late because you don’t have time to digest it.

The majority of parents would have preferred to complete PW closer to discharge to build new habits and prepare for their adolescent’s reintegration into the home. For example, parent #8 said: “I think, when she went in, it should be introduced then.” Similarly, parent #12 said she would be able to relate to the content better closer to when her daughter was coming home: “Just because [PW] is about the home situation, which is not where she is right now. Or even leading up to her coming home would probably be good timing.” Parent #17 provided additional insight into how parents’ needs and capacity to complete programming change throughout treatment:

I think it depends on where [parents] are. The people who are new to treatment, you can tell they’re a little bit in rough shape. And what they share is very different. They’re looking for an answer versus people like myself, who we’ve been doing this for a long time, and are a little bit farther along in our own personal growth. It’s a different kind of sharing, and there isn’t that sense of urgency.

Satisfaction with Web-based Delivery

We asked parents about the strengths and weaknesses regarding PW’s web-based approach. Overall, parents preferred a web-based approach compared to in-person for various reasons, including convenience and not needing to arrange for childcare or transportation. For example, parent #4 said:

It’s so hard, just as a parent anyway, to find the time. And so, having the ability to do it late at night when the kids were asleep is way more effective than having to go to a class or find a sitter so you can go on a weekend.

Parent #7 also said that web-based was preferred because of the ability to “move at your own pace” through the content. Parent #20 shared that the only time she has to herself is at night which is also when she could complete modules. Parent #11 liked that there were scenarios with different parent responses to adolescent behaviors: “[I liked] to see it play out in front of your eyes with the wrong reaction. I liked the thoroughness of the explanations. Like, “What did mom do well in this scenario? Or how did mom role model well?”. Parent #4 describes how PW supports her and her husband, who have different learning styles:

So I was the only one who even got to access the online stuff. He could read about it but he’s not that kind of learner. Whereas if he had watched videos or something, it would have been far more useful for him. For me, I like the practice test because that’s the way that I learn is reinforcing that knowledge for me. I am not an auditory learner so videos are actually hard. But I read the subtitles and then take the tests then I feel really confident, whereas he would watch the videos and be fine. I like that it has both so that it addresses that because people learn differently.

Satisfaction with Content and Scenarios

Representativeness

Some parents felt that one of the strengths of PW was that the videos included diverse families (e.g., single parent, step-parent, grandparent). Multiple parents felt that the step-parenting module was representative of “how things are.” Parent #16 shared that she appreciated that the modules were “culturally inclusive” and noticed “a nice variety of family structures…It’s not all white middle-class families. I can tell that there’s been some effort made there.” Parent #12 shared that although she may not have identified with what the families were going through, she appreciated how “real” the scenarios were. She said:

So the first [module] was a two-parent family with multiple kids. But I’m a single lesbian mom with an only child. So after the first one, I was pretty disheartened, but then I went to the second one and I think that one was the divorced family. And I was like, “Okay, there’s some useful information here.” I guess that’s what was useful is the role of a step-parent was, I thought, helpful. That’s what I like about Parenting Wisely is they are real-life examples, even if they’re not my life.

Relatability

Parents were asked to provide their input into how satisfied they were with the content and how relatable the content and scenarios were. A subgroup of parents (n = 3) felt that some of the scenarios in PW were difficult to relate to because they perceived their adolescent’s behaviors as more challenging than what was depicted in the modules. For example, parent #16 said, “[my] kids’ responses are much more extreme than what’s in the video…even if the conflict is familiar, the reaction of the kids was way less.” Similarly, parent #4 shares that some of the modules were relatable but “the topics that were covered aren’t necessarily what [parents] deal with, because mental illness makes everything about parenting so different.” Parent #10 said that while parents are dealing with curfew, the level of behaviors is elevated in adolescents who had been to RT:

We need a curfew, but we’re dealing with kids who’ve been… Literally, run away for a week, and there’ve been like searching for them. Police have been searching for them. Not to say that any of this stuff is unimportant. It’s just a piece. The finding drugs… We’re dealing with parents who are trying to decide if… Do I negotiate down to just pot because it’s legal in our state? Because I’d rather them at least be doing pot versus something worse.

Another subgroup of parents (n = 7) felt the scenarios were relatable, but the content was a “refresher” of what they had already learned. For example, parent #4 said, “A lot of this is stuff we’ve already heard and things we’ve used before. I think anything is always good to be reinforced because we get into habit. So all of it is a good refresher.” Parent #8 said that while the content was basic at times, it was still helpful to be reminded of helpful strategies. She said, “I think these are skills that every parent should be shown and taught. It may be basic stuff, but when you’re in the heat of the moment, it’s good to have that reminder. Just stop, take a breath, and think.” Parent #6 shares that while the skills are not necessarily new information, the rationale for how harsh parenting impacts relationships was new information. She said, “PW gives good reasoning for why some of the harsh parenting that most parents are being told they need to do to get their kids to shape up, how that impacts the relationship with the child.” Parent #2 mentioned that while the content may be a reminder to some parents, it’s essential because families were in crisis before RT: “Even if 1 out of 10 [parents] that had the skills prior to the crisis has either lost or gained inappropriate parenting. So, we have to reestablish and get back to who we were prior to the crisis”.

A third subgroup of parents (n = 9) reported that the PW modules were highly relatable and the skills were useful. Parent #11 said, “The areas of conflict in our home were well-represented. This has played out in our home exactly.” Parent #19 recognized early on that the content built on each other and felt the scenarios depicted the skills in a digestible manner: “I felt the content…did a really good job introducing a concept, like the prompts or role modeling, and then building upon it, more and more with each module. I thought it was really good, and they really reinforced the concepts.” Parent #16 felt that the scenarios were relatable and commented that when she watched how parents responded to the adolescent behaviors in the videos, she recognized some of her own behaviors:

I felt like giving different ways of responding to something that happened is really good, like this is really not something you should do. And what’s good about that is not in the moment as a parent, you’re looking at it going, “wow that really looks terrible.” When you’re seeing someone else do it.

Congruent with the notion that PW may be useful as a preventive tool, parent #15 felt the scenarios were “on target for me with [her] younger kids who have not had any problems.” Parent #7 felt particularly drawn to the module on step-parenting because the scenario represented some of the conflicts she deals with daily. She said:

In our family, there’s technically a step-parent, even though my husband adopted my son, but still, there’s still always a discord there. So one of them that I did with the step-parents…and the mom being stuck in the middle of the two, I feel that on a daily basis.

Mixed Methods Results

The qualitative interviews uncovered factors separate from the end-of-program survey that contributed to parents’ perceptions of PW. The interviews allowed parents to elaborate on critical factors for future studies and transporting PW to the RT setting. Regarding acceptability, most parents reported that PW was user-friendly and the content was relatively clear, indicating that they were satisfied with the content and delivery method. However, in the qualitative interviews, parents elaborated that parent training programs such as PW should be provided earlier in the adolescent’s treatment trajectory. Parents also shared that the web-based delivery method made it so they could complete modules at their convenience, which was perceived as helpful for parents since they were balancing competing demands.

The end-of-program survey findings were mixed regarding the helpfulness of the videos and reflection questions in PW (i.e., appropriateness). Parents reported valuing that diverse families were portrayed in the modules. However, one subgroup of parents identified that the challenges they were experiencing with their adolescents were not represented in the videos. Because parents could not identify with the scenarios, they had difficulty understanding how to apply the skills in their lives. The second subgroup of parents perceived the videos as examples of skills application not meant to represent their family. This subgroup perceived the modules as a “refresher” in which the content served as a reminder. The third subgroup of parents felt the content in PW was very representative of their families and could identify multiple methods of how they might use the PW skills in their life.

Feasibility in this study referred to the utility of PW and the likeliness of transporting PW to the RT setting. Parents reported spending approximately 30 min per week on modules that they reported as feasible in the qualitative interviews. Further, there was a high rate of module completion (80% on average), suggesting that completing modules was not overly burdensome. The qualitative feedback highlighted that parents learned skills from the modules and even practiced some skills, particularly communication skills. The qualitative interviews also provided an unexpected finding related to parent alignment that we did not ask about in the end-of-program survey. Parents emphasized in the interviews the importance of having a support person complete modules with them to enhance consistency.

Discussion

Previous research has shown that providing parents with education and support may prolong treatment gain maintenance for adolescents discharged from RT (Maltais et al., 2019; Nickerson et al., 2004). Parent training is one evidence-based method of supporting parents through teaching parents strategies to mitigate disruptive behaviors. Previously, parent training in the RT setting has been delivered to staff rather than parents (Parris et al., 2015; Parry et al., 2021; Silva et al., 2016). Most of the parent training programs delivered to parents have been delivered in-person, posing several barriers to participation (Baker et al., 2011; Duppong-Hurley et al., 2016; Garvey et al., 2006). This study contributes to the literature regarding the acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of a web-based parent training delivered in the RT setting. First, the study focuses on parents who are end-users of parent training programs. Engaging parents in evaluating PW allows for an understanding of potential modifications and tailoring that need to occur to increase uptake. Second, this is among the first studies to evaluate parent training in this population whose web-based components could lead to greater reach, engagement, and access. Finally, the mixed methods design allowed for a complete understanding of barriers and facilitators to using PW, including considerations for future research and transporting PW to clinical practice.

Acceptability

Parents reported that one of the greatest strengths of PW was the web-based delivery. Parents mentioned that the flexibility of completing modules at any time contributed to their high module completion rate (average of 80%). This study began at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic when web-based delivery was the most viable option for conducting research with this population, especially with RT facilities limiting visitors. Our study is among the first to test a web-based approach in this population, and similar to other evaluations, findings suggest the web-based approach increased access because barriers such as scheduling, travel, and time constraints were removed (Baker et al., 2011; Chacko et al., 2016; Duppong-Hurley et al., 2016; Garvey et al., 2006). While there is meta-analytic evidence that web-based parent training interventions have moderate effects on disruptive behaviors (Baumel et al., 2016, 2017), this study did not evaluate the efficacy of PW. Further testing is warranted to determine if PW is efficacious in the RT population. Furthermore, given the high acceptability of web-based approaches coupled with the ongoing pandemic, researchers and clinicians may consider delivering other supports remotely. Previous research suggests that parents may be isolated, stigmatized and desire connection with other parents (Herbell et al., 2020; Nickerson et al., 2004). Web-based support groups could be one method of engaging and supporting families, especially for families that live significant distances from RT.

Appropriateness

A subset of parents found PW difficult to relate to because parents perceived their adolescents’ behaviors as more severe than those featured in PW. One potential reason for this perception is that PW was designed for court-involved adolescents who have similarities to the RT population but do not exactly mirror the characteristics and needs of families in RT. One possible way these populations differ is regarding trauma exposure which may underpin the differences in behavioral presentation (Briggs et al., 2012). For example, compared to community-dwelling children with trauma histories, children in RT experienced more traumatic events, which correlated with greater behavioral and attachment challenges and more high-risk behaviors such as running away, substance use, self-injurious behavior, and criminal activity (Briggs et al., 2012). Our team did not collect data on the characteristics, frequency, or intensity of adolescents’ behaviors or trauma histories which may have contributed to the perception that PW was unrelatable for a subset of parents. An important consideration for future research is collecting adolescent diagnoses and admitting circumstances to understand whom interventions like PW work for. Further, parents with adolescents in RT and especially those whose adolescents have trauma histories may require specialized behavior management strategies that are trauma-informed (Paterson-Young 2021). While PW has elements of trauma-informed care (e.g., connection, self-regulation), PW may need to be augmented with supplemental material that more fully addresses the impact of trauma on disruptive behaviors and the parent-child relationship.

Another consideration when interpreting findings is that parent training programs are not intended to address every challenge parents and adolescents experience. Instead, parent training programs in this population should be viewed as adjuvant to other evidence-based approaches (e.g., intensive home and community-based services). Consistent with other studies, PW is not a “one-size-fits-all” program and likely needs to be tailored to meet the RT populations’ needs (Breitenstein et al., 2015; Butler & Titus, 2015; Chacko et al., 2017; Rajwan et al., 2014). For example, Becker and colleagues (2021a, 2021b) augmented PW with individual telehealth coaching sessions for parents (N = 60) with teens in substance use treatment. The augmentation was feasible, acceptable (Becker et al., 2021a), and effective in increasing positive parenting skills (Becker et al., 2021b) and decreasing adolescent externalizing behaviors (Becker et al., 2021a). The PW skills are evidence-based parenting skills, and perhaps the best way to tailor the skills to the unique situations that parents in RT experience are through coaching or group sessions (Becker et al., 2021a). Group or coaching sessions may allow parents to discuss the challenges they are experiencing in real time and promote discussion on how to apply parenting skills (Chacko et al., 2009; Rotheram-Borus et al., 2018).

Feasibility

The study team tracked rates of study withdrawal, and participants completed survey questions on module completion and time spent completing modules. Four parents were lost to follow up and never logged in to PW. This attrition rate was slightly less than what is reported as the average attrition (20%) in a systematic review of parent training programs (Chacko et al., 2016). Most parents reported spending less than 30 min per week on modules which they reported in the interviews as feasible. Of the parents who completed the study (N = 20), more than 80% of modules were completed by parents, which is higher than the average rate of 72% in Chacko and colleagues (2016) systematic review. This is an encouraging finding because the benefits of parent training programs rely on parent engagement (e.g., attendance, adherence, and cognitions) (Becker et al., 2015).

Parents shared that the PW skills were easy to understand and learn because the video scenarios were succinct and simple. For some parents, the simplistic scenarios allowed them to learn the skill application quickly. Parents frequently reported using logical consequences, effective communication, and active listening with adolescents. There was low uptake of behavior contracts which was surprising considering behavior contracts are used in multiple settings, including RT (Edgemon et al., 2021; Stanger et al., 2015). Developing a home behavior contract tailored to the adolescent’s strengths and needs may be beneficial as it provides some continuity of care. While behavior contracts are effective for mild disruptive behaviors (e.g., off-task, inappropriate social interaction; Bowman-Perrott et al., 2015; Edgemon et al., 2021), behavior contracts are complex and involve multiple components. The low rate of behavior contract uptake may be because parents require individual support through methods such as coaching to implement this more complex skill.

While we did not include multiple parents from the same family in our study, some parents were naturally inclined to share the PW content with their partners. Parents reported that completing PW with a partner was helpful and motivational and promoted accountability and consistency in parenting practices. Conversely, parents with partners who were not receptive to completing PW found implementing the skills challenging. The majority of enrolled parents’ partners were male fathers or father figures. The notion that some fathers or father figures were uninterested in parent training is consistent with the existing literature that describes the low uptake and under-representation of father figures in preventative interventions (Fabiano 2007). Future parent training research in the RT population should include other caregivers in the adolescent’s life and encourage multiple caregivers to participate because there are positive benefits when multiple caregivers are aligned in their parenting practices (Rienks et al., 2011). While we suggest enrolling all interested caregivers in future studies, future research should also examine parents’ perceptions of parent training because cognitions and intentions are related to engagement with parent training (Gonzalez et al., 2021). Moreover, when study investigators or clinicians introduce the study to parents, it may be beneficial to present the study in a way that emphasizes parent training contains useful, evidence-based skills that often lead to positive outcomes for parents and adolescents (Salari & Filus, 2016; Thornton & Calam, 2011). Presenting parent training in a positive light may alter parents’ cognitions which are related to intention and engagement in parent training programs (Gonzalez et al., 2021).

Limitations and Future Directions

The findings presented should be viewed in light of several limitations. While the adolescents were representative of the RT population regarding age (average 15 years old nationally) and gender (60% male nationally) (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2018), parents were primarily white, educated, moderate to high-income females who do not represent the full demographic variability of parents. Therefore, there is potential selection bias because the recruitment method (i.e., Facebook) required participants to self-select into the study. Participants may have shared characteristics such as sex, race/ethnicity, income, or motivation different from those who did not participate. Further, this study began at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited the study team’s ability to recruit parents from RT facilities which could have yielded a more diverse sample. The lack of diversity in our study sample highlights a future recommendation to recruit a larger and more diverse sample that captures the known diversity in the RT population. Second, we used a post-test design with self-report usage metrics for this pilot study. In the future, we plan to use a more robust approach such as a pre-test post-test design and will obtain objective metrics of usage and time spent in modules. Future studies should consider standardized quantitative measures of feasibility (e.g., Feasibility of Intervention Measure) and acceptability (e.g., Acceptability of Intervention Measure) (Weiner et al., 2017). Future studies should also collect adolescent diagnoses to capture the variability in diagnoses of the sample to determine better whom interventions like PW work for. Third, four parents dropped out of the study shortly after enrollment. Attrition is a prevalent factor in parent training studies and will need to be closely monitored to understand the feasibility of parent training programs in this population. Finally, we did not examine the influence of PW on outcomes such as the parent-child relationship, parenting behaviors, or adolescent disruptive behaviors. This represents an essential next step in testing and tailoring PW for the RT population. Despite these limitations, this pilot feasibility study provides helpful information for future research in supporting families transitioning from RT to the community.

Conclusion

Transitioning from RT to the community is a highly stressful and critical point in an adolescent and family’s treatment trajectory. For the transition to be successful, families need support. Parent training, in addition to other evidence-based approaches, may be a feasible and effective method for adolescents to maintain treatment gains. Some parents naturally practiced the skills in their daily lives and found it beneficial to have a partner to practice the skills with. While PW was perceived as helpful, many felt it would have been ideal to complete PW early on in their adolescent’s mental health journey. However, they also reported that PW would be most valuable while their adolescent resided in RT because this space allowed parents to engage with the material. Parents appreciated the inclusion of diverse families in the modules; however, relatability varied. A large subset of parents related to the scenarios, while a small subset of parents felt the modules were challenging to relate to because of the severity of their adolescent’s mental health challenges. Overall, these findings highlight several areas for future research, including devising recruitment methods that target a more diverse and representative sample of the RT population. Findings also indicate that parent training may be a feasible adjuvant evidence-based approach and other supports in the post-RT period. However, tailoring strategies is necessary because of the severity and breadth of adolescents’ mental health challenges.

References

Akin, B. A., Yan, Y., McDonald, T., & Moon, J. (2017). Changes in parenting practices during Parent Management Training Oregon model with parents of children in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 76, 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.03.010.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP). (2016). Residential Treatment Programs. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://www.aacap.org/aacap/families_and_youth/facts_for_families/fff-guide/Residential-Treatment-Programs-097.aspx.

Baker, C. N., Arnold, D. H., & Meagher, S. (2011). Enrollment and attendance in a parent training prevention program for conduct problems. Prevention Science, 12(2), 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-010-0187-0.

Baumel, A., Pawar, A., Kane, J. M., & Correll, C. U. (2016). Digital parent training for children with disruptive behaviors: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 26(8), 740–749. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2016.0048.

Baumel, A., Pawar, A., Mathur, N., Kane, J. M., & Correll, C. U. (2017). Technology-assisted parent training programs for children and adolescents with disruptive behaviors: A systematic review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(8), e957–e969. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.16r11063.

Becker, K. D., Lee, B. R., Daleiden, E. L., Lindsey, M., Brandt, N. E., & Chorpita, B. F. (2015). The common elements of engagement in children’s mental health services: Which elements for which outcomes? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 44(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.814543.

Becker, S. J., Helseth, S. A., Janssen, T., Kelly, L. M., Escobar, K., & Spirito, A. (2021b). Parent Smart: Effects of a technology-assisted intervention for parents of adolescents in residential substance use treatment on parental monitoring and communication. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 6(4), 459–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2021.1961644.

Becker, S. J., Helseth, S. A., Janssen, T., Kelly, L. M., Escobar, K. I., Souza, T., Wright, T., & Spirito, A. (2021a). Parent SMART (Substance Misuse in Adolescents in Residential Treatment): Pilot randomized trial of a technology-assisted parenting intervention. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 127, 108457 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108457.

Birks, M., Chapman, Y., & Francis, K. (2008). Memoing in qualitative research: Probing data and processes. Journal of Research in Nursing, 13(1), 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987107081254.

Bowman-Perrott, L., Burke, M. D., de Marin, S., Zhang, N., & Davis, H. (2015). A meta-analysis of single-case research on behavior contracts: Effects on behavioral and academic outcomes among children and youth. Behavior Modification, 39(2), 247–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445514551383.

Breitenstein, S. M., & Gross, D. (2013). Web-based delivery of a preventive parent training intervention: A feasibility study. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 26(2), 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12031.

Breitenstein, S. M., Shane, J., Julion, W., & Gross, D. (2015). Developing the eCPP: Adapting an evidence-based parent training program for digital delivery in primary care settings. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 12(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12074.

Briggs, E. C., Greeson, J. K. P., Layne, C. M., Fairbank, J. A., Knoverek, A. M., & Pynoos, R. S. (2012). Trauma exposure, psychosocial functioning, and treatment needs of youth in residential care: Preliminary findings from the NCTSN Core Data Set. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 5(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361521.2012.646413.

Bryson, S. A., Gauvin, E., Jamieson, A., Rathgeber, M., Faulkner-Gibson, L., Bell, S., Davidson, J., Russel, J., & Burke, S. (2017). What are effective strategies for implementing trauma-informed care in youth inpatient psychiatric and residential treatment settings? A realist systematic review. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 11, 36 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-017-0137-3.

Burke, R., Herron, R., & Barnes, B. A. (2006). Common sense parenting: Using your head as well as your heart to raise school-aged children (3rd ed.). Boys Town Press.

Butler, A., & Titus, C. (2015). Systematic review of engagement in culturally adapted parent training for disruptive behavior. Journal of Early Intervention, 37(4), 300–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815115620210.

Capaldi, D. M., Chamberlain, P., & Patterson, G. R. (1997). Ineffective discipline and conduct problems in males: Association, late adolescent outcomes, and prevention. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 2(4), 343–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-1789(97)00020-7.

Carr, A., Hartnett, D., Brosnan, E., & Sharry, J. (2017). Parents plus systemic, solution-focused parent training programs: Description, review of the evidence base, and meta-analysis. Family Process, 56(3), 652–668. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12225.

Cefai, J., Smith, D., & Pushak, R. E. (2010). Parenting Wisely: Parent training via CD-ROM with an Australian sample. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 32(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317100903539709.

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2018). Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables, SAMHSA, CBHSQ. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHDetailedTabs2017/NSDUHDetailedTabs2017.htm#lotsect11pe.

Chacko, A., Wymbs, B., Rajwan, E., Wymbs, F., & Feirsen, N. (2017). Characteristics of parents of children with ADHD who never attend, drop out, and complete behavioral parent training. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 26(3), 950–960. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0618-z.

Chacko, A., Jensen, S. A., Lowry, L. S., Cornwell, M., Chimklis, A., Chan, E., Lee, D., & Pulgarin, B. (2016). Engagement in behavioral parent training: Review of the literature and implications for practice. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19(3), 204–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-016-0205-2.

Chacko, A., Wymbs, B. T., Wymbs, F. A., Pelham, W. E., Swanger-Gagne, M. S., Girio, E., Pirvics, L., Herbst, L., Guzzo, J., Phillips, C., & O’Connor, B. (2009). Enhancing traditional behavioral parent training for single mothers of children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 38(2), 206–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802698388.

Christenson, S. L., Sinclair, M. F., Thurlow, M. L., & Evelo, D. (1999). Promoting student engagement with school using the Check & Connect Model. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 9(S1), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1037291100003083.

Creswell, J., & Creswell, J. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 5th ed. SAGE Publications, Inc.

Daley, D., van der Oord, S., Ferrin, M., Danckaerts, M., Doepfner, M., Cortese, S., & Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S., European ADHD Guidelines Group. (2014). Behavioral interventions in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials across multiple outcome domains. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(8), 835–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.05.013. 847.e1-5.

Duppong-Hurley, K., Hoffman, S., Barnes, B., & Oats, R. (2016). Perspectives on engagement barriers and alternative delivery formats from non-completers of a community-run parenting program. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(2), 545–552. psyh. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0253-0.

Edgemon, A., Rapp, J., Coon, J., Cruz-Khalili, A., Brogan, K., & Richling, S. (2021). Using behavior contracts to improve behavior of children and adolescents in multiple settings. Behavioral Interventions, 36, 271–288. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1757.

Fabiano, G. A. (2007). Father participation in behavioral parent training for ADHD: Review and recommendations for increasing inclusion and engagement. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 683–693. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.683.

Feil, E. G., Gordon, D., Waldron, H., Jones, L. B., & Widdop, C. (2011). Development and pilot testing of an internet-based version of Parenting Wisely. The Family Psychologist, 27(2), 22–26.

Frensch, K. M., & Cameron, G. (2002). Treatment of choice or a last resort? A review of residential mental health placements for children and youth. Child and Youth Care Forum, 31(5), 307–339. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016826627406.

Garvey, C., Julion, W., Fogg, L., Kratovil, A., & Gross, D. (2006). Measuring participation in a prevention trial with parents of young children. Research in Nursing & Health, 29(3), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20127.

Glaser, B. (1978). Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Sociology Press.

Gonzalez, C., Morawska, A., & Haslam, D. M. (2021). A model of intention to participate in parenting interventions: The role of parent cognitions and behaviors. Behavior Therapy, 52(3), 761–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2020.09.006.

Gordon, D. (2000). Parent training via CD-ROM: Using technology to disseminate effective prevention practices. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 21(2), 227–251. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007035320118.

Gordon, D., & Stanar, C. (2003). Lessons learned from the dissemination of parenting wisely, a parent training CD-ROM. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 10(4), 312–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1077-7229(03)80049-4.

Gordon, D. (2005). Parenting wisely program workbook. Family Works Inc.

Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

Herbell, K., Banks, A. J., Bloom, T., Li, Y., & Bullock, L. F. C. (2020). Priorities for support in mothers of adolescents in residential treatment. Children and Youth Services Review, 110, 104805 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104805.

Herbell, K. S., & Breitenstein, S. M. (2020). Parenting a child in residential treatment: Mother’s perceptions of programming needs. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 0(0), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2020.1836536.

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Huefner, J. C., Pick, R. M., Smith, G. L., Stevens, A. L., & Mason, W. A. (2015). Parental involvement in residential care: Distance, frequency of contact, and youth outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(5), 1481–1489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9953-0.

Kacir, C. D., & Gordon, D. (2000). Parenting Adolescents Wisely: The effectiveness of an interactive videodisk parent training program in Appalachia. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 21(4), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1300/J019v21n04_01.

Kaminski, J. W., Valle, L. A., Filene, J. H., & Boyle, C. L. (2008). A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(4), 567–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9.

Maltais, C., Cyr, C., Parent, G., & Pascuzzo, K. (2019). Identifying effective interventions for promoting parent engagement and family reunification for children in out-of-home care: A series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Negl, 88, 362–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.12.009.

Mello, M. J., Bromberg, J. R., Baird, J., Wills, H., Gaines, B. A., Lapidus, G., Ranney, M. L., Parnagian, C., & Spirito, A. (2019). Feasibility and acceptability of an electronic parenting skills intervention for parents of alcohol-using adolescent trauma patients. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health: The Official Journal of the American Telemedicine Association, 25(9), 833–839. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2018.0201.

Michelson, D., Davenport, C., Dretzke, J., Barlow, J., & Day, C. (2013). Do evidence-based interventions work when tested in the “real world?” A systematic review and meta-analysis of parent management training for the treatment of child disruptive behavior. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-013-0128-0.

Nickerson, A. B., Salamone, F. J., Brooks, J. L., & Colby, S. A. (2004). Promising approaches to engaging families and building strengths in residential treatment. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 22(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1300/J007v22n01_01.

O’Neill, H., & Woodward, R. (2002). Evaluation of the Parenting Wisely CD-ROM parenting training programme: An Irish replication. Irish Journal of Psychology, 1–2, 62–72.

Parris, S. R., Dozier, M., Purvis, K. B., Whitney, C., Grisham, A., & Cross, D. R. (2015). Implementing Trust-Based Relational Intervention® in a charter school at a residential facility for at-risk youth. Contemporary School Psychology, 19(3), 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-014-0033-7.

Parry, S. L., Williams, T., & Burbidge, C. (2021). Restorative parenting: Delivering trauma-informed residential care for children in care. Child & Youth Care Forum, 50(6), 991–1012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09610-8.

Paterson-Young, C. (2021). Exploring how children subjected to violence in the home cope with experiences in Secure Training Centres. Child Abuse & Neglect, 117, 105076 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105076.

Patterson, G. R., Forgatch, M. S., Yoerger, K. L., & Stoolmiller, M. (1998). Variables that initiate and maintain an early-onset trajectory for juvenile offending. Development and Psychopathology, 10(3), 531–547. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579498001734.

Patterson, G. (1982). Coercive family process. Castalia.

Patterson, G. R., & Reid, J. (1970). Reciprocity and coercion: Two facets of social systems. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7.

Racine, N., Hartwick, C., Collin-Vézina, D., & Madigan, S. (2020). Telemental health for child trauma treatment during and post-COVID-19: Limitations and considerations. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110, N.PAG–N.PAG. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104698.