Abstract

Given the large discrepancy between prevalence rates of mental disorders in adolescents and actual treatment rates, there is a need to understand what prevents this age group from seeking psychotherapy. We assessed the barriers to seeking psychotherapy in this age group, including their attitudes toward people with a mental disorder, using a convergent parallel mixed-methods design. Participants were 288 adolescents aged 12–21 years (M = 16.8 years, SD = 2.3; 37% identified as male, 63% as female, and 0% as nonbinary). Qualitative data were obtained with open-ended questions on barriers to initiating psychotherapy and attitudes toward people with a mental disorder. Barriers to seeking psychotherapy and information about psychotherapy were assessed with a questionnaire using a quantitative design. The qualitative assessment revealed as the main barriers fear of a negative interaction with a psychotherapist, fear of being confronted with their own emotions, self-stigma, and fear of public stigma. Further, lack of accessibility, lack of trust in the therapist, a desire for social distance from, and a negative attitude toward people with a mental disorder were associated with a decreased intention to initiate psychotherapy. Previous positive experience with a psychotherapist was a facilitator of seeking psychotherapy. We found gender differences, with higher desire for social distance and higher optimism bias scores as well as poorer mental health knowledge for participants identifying as male. Integrating results from both approaches results in further information for the improvement of prevention programs and interventions to lower barriers to seeking psychotherapy. Gender differences indicate a need for gender-role-specific interventions.

Highlights

-

Adolescents reported self-stigma and fear of interacting with a psychotherapist, fear of being confronted with their own emotions, and fear of public stigma as barriers to seeking psychotherapy.

-

Interventions that increase specific information about psychotherapy (especially transparency about the psychotherapy setting) to lower barriers to seeking psychotherapy are needed.

-

Self-disclosure of people having experience with psychotherapy is important to lower barriers to seeking psychotherapy for others.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Prevalence rates of mental disorders (e.g., depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, eating disorder) in adolescents, at approximately 17–50%, are high (Gore et al., 2011; Merikangas et al., 2010a). Yet only 10–36% of adolescents with mental disorders use mental health services and less than 40% of those receive stable long-term treatment (Hintzpeter et al., 2014; Lu, 2020). Mental disorders first manifest mostly in childhood and adolescence (Kessler et al., 2005; Merikangas et al., 2010a). Adolescents are therefore an important target group in which to evaluate barriers to professional help seeking, especially because the delay in treatment is longer for early-onset cases of mental disorders than for onset at a later age (Christiana et al., 2000) with an average of 7 to 11 years to the beginning of treatment (Kessler et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2004). Overcoming barriers to seek treatment for mental disorders is crucial as nontreatment leads to chronicity, exacerbation of symptoms, higher impairment of life quality, a lower probability of successfully treating the disorder later, and an increased risk of suicide and self-harm (Lambert et al., 2013; Marshall et al., 2005; Merikangas et al., 2010a).

Regarding the question of why adolescents and young adults do not seek help for mental health problems there is evidence for common barriers as stigma, family beliefs about mental health service and treatment, poor mental health literacy, and autonomy as main barriers (Aguirre-Velasco et al., 2020). In their review, Gulliver and colleagues (2010) distinguished public, perceived, and self-stigmatizing attitudes to mental disorders specific barriers as well as barriers associated with poor mental health literacy (difficulty identifying the symptoms of mental disorders, knowledge about mental health services). They also reported fear-related barriers, for example a lack of confidentiality and trust, concerns about the characteristics of the provider, fear or stress about the act of help seeking or the source of help itself, difficulty or an unwillingness to express emotion, unwillingness to burden someone else and worries about an effect on their career. Some adolescents also reported a lack of accessibility (e.g. time, transport, costs) and other prefer other sources of help than mental health care (e.g. family and friends).

There is evidence that older adults have concerns regarding an age gap between the therapist and the patient (Pepin et al., 2009), which might also be relevant for adolescents. In other studies with adult samples, participants also reported a lack of encouragement from their social network to seek help (van Beljouw et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2007) and shame or fear of being labeled (Clement et al., 2015; Schnyder et al., 2017; Schomerus et al., 2019). Having a stigmatizing attitude toward people with mental disorders often implies a desire for social distance, that is, a rejection of social interactions with people dealing with mental health problems (Jorm & Oh, 2009). Because seeking mental health care generally leads to (self)-labeling as a person with mental health issues in need of help, the desire for social distance is therefore negatively associated with help-seeking intentions (Schnyder et al., 2017). Personal contact with people with mental disorders (Clement et al., 2015; Mittal et al., 2016), on the other hand, is often associated with decreased desire for social distance and lower stigmatizing attitudes (Bellanca & Pote, 2013; Calear et al., 2011; Griffiths et al., 2008; Pearl et al., 2016) and can therefore be considered a facilitator of seeking mental health care. Other reasons that keep adults from seeking treatment for mental health problems are lack of knowledge about mental health services, for example, how to access such services, doubts about the efficacy of treatment, concerns about confidentiality, knowledge whether psychotherapy is financially covered by their health insurance (Andrade et al., 2014; Clement et al., 2015; Mohr et al., 2006; Pepin et al., 2009), transportation concerns, lack of time, and a preference for alternative ways of dealing with mental health problems (Mohr et al., 2006; Mojtabai et al., 2011).

A preference for alternative or other sources of help and reliance on self, might also be associated with a lack of mental health literacy, when people underestimate the impact of their mental health problems and are biased about the probability of being affected by a mental disorder (Weinstein & Klein, 1996). They might present an optimism bias, that is, the tendency to believe that they are less at risk than others or that they are better equipped to cope with symptoms of mental disorders than others, which is associated with a lower probability of help-seeking behavior (Spendelow & Jose, 2010).

The investigation of adolescent-specific barriers is important, as adolescents differ from adults in many aspects. Increasing maturity and responsibility, associated with adult roles, can affect vulnerability to mental disorders and the way individuals understand and respond to their own mental health problems (Fleming & Offord, 1990). However, their pursuit of autonomy might also be a reason why adolescents desire to solve their problems on their own, are ashamed to ask for help (Wilson et al., 2002) or are in denial about their problems (Bilican, 2013). The estimated likelihood of seeking formal help for personal or emotional problems and suicidal thoughts is relatively low, and adolescents instead prefer informal help sources (Cakar & Savi, 2014; Sawyer et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2005). Formal help is defined as help from professionals who have a recognized role and appropriate training in providing help and advice, whereas informal help sources (e.g., friends or family) lack a professional background (Rickwood et al., 2007). Despite their children’s desire for autonomy, parents still play an important role in the help-seeking process. Youths’ willingness to seek help is higher when they think their parents support the use of mental health services (Chandra & Minkovitz, 2006; Wahlin & Deane, 2012) and lower when they think their parents would be ashamed of them because of their mental health problems (Moses, 2009).

The investigation of barriers toward formal help-seeking also requires to consider factors, which are associated with a lower probability of seeking help for mental health problems. Negative attitudes for example are influenced by gender, age, and personal experience with mental disorders and help seeking. In men compared to women, there is evidence of lower help-seeking intentions for mental health problems (Addis & Mahalik, 2003; Oliver et al., 2005; Petrowski et al., 2014) and less mental health knowledge (Farrer et al., 2008). Boys compared to girls have reported higher mental health stigma and less willingness to use mental health services (Chandra & Minkovitz, 2006; Gonzalez et al., 2005). Further, there is evidence that higher age is associated with higher mental health knowledge and a less stigmatizing attitude (Farrer et al., 2008; Swords et al., 2011).

To date, little is known about barriers specific to seeking psychotherapy in contrast to seeking mental health care in general (Divin et al., 2018), which includes a variety of treatments (e.g., treatments in inpatient psychiatric settings and psychopharmacotherapy). Psychotherapy is defined as any psychological service provided by a trained professional that primarily uses forms of communication and interaction (as opposed to psychopharmacological treatment) to assess, diagnose, and treat dysfunctional emotional reactions, ways of thinking, and behavior patterns (American Psychological Association, n.d.). Psychotherapy is also defined as clinically relevant empirically supported interventions of any type that are based on knowledge and expertise in the psychological sciences. This definition includes a large group of methods and approaches, developed to address the needs of patients and groups of patients with mental disorders or mental health problems, as well as their networks of support (Wittchen et al., 2015). Psychological treatments include a range of interventions (e.g., psychoeducation, cognitive interventions, behavioral exercises, mindfulness-based interventions) to achieve a priory defined aims (e.g., reduction of symptoms, improvement of coping strategies to deal with symptoms of a mental disorder, improvement of sleep-quality).

In German adult samples, researchers found rather positive attitudes toward psychotherapy (Petrowski et al., 2014) but also that participants would be ashamed if neighbors and friends knew about their use of psychotherapy (Albani et al., 2014). Findings of specific attitudes toward psychotherapy in a younger sample might help improve interventions designed to increase the utilization of psychotherapy in adolescents.

One reason for negative attitudes toward psychotherapy might be the often inaccurate and negative representation of psychotherapy on television and in movies for entertainment purposes, but this is beginning to change with videos on YouTube presenting a more accurate representation of counseling and psychotherapy (Furlonger et al., 2015). In movies, psychotherapy is often presented in a psychoanalytical setting, although this approach is rarely used, and especially not with adolescents (Gabbard, 2001; Wahl et al., 2018; Wedding & Niemiec, 2003). Therapists’ behavior toward their patients is often portrayed as questionable, unethical, and even criminal, for example, depicting therapists touching the patient other than shaking hands, violating professional confidentiality, or engaging with the patient socially outside of treatment. An incorrect representation of psychotherapy and psychotherapists is problematic as it is associated with self-stigma and often interferes with real-life perceptions (Maier et al., 2014).

To summarize, the assessment of barriers to psychotherapy in adolescents might deliver further findings that could be useful for the enhancement of interventions aiming to reduce those barriers. Quantitative dimensional measures for assessing barriers to mental health care for adolescents that report psychometric properties are scarce (Aguirre Velasco et al., 2020; Divin et al., 2018). A multimethod design that generates top-down information on barriers to formal help seeking for mental health problems as well as bottom-up information specifically about barriers to psychotherapy might be a promising approach. Mixed-methods designs can provide a more comprehensive account of barriers to psychotherapy and might enhance the integrity of findings, as well as enhancing further instrument development or revisions by integrating qualitative results (Bryman, 2006). Therefore, we used a Triangulation mixed-method design with a convergent parallel design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011), using a concurrent quantitative and qualitative data selection to assess barriers to seeking psychotherapy in adolescents. The two data sets are analyzed separately and merged for the overall interpretation to assess in what ways reported barriers converge or diverge.

We hypothesized that poorer mental health knowledge and higher barriers to seeking psychotherapy would be associated with a decreased intention to seek formal help by initiating psychotherapy in the event of serious mental health problems. We also hypothesized that adolescents who had had a personal encounter with a psychotherapist or who knew a person with current or past experience with psychotherapy would report lower barriers and better mental health knowledge. We also controlled for social desirability bias as it has been associated with response behavior on questions regarding intended help-seeking behavior and stigma (Henderson et al., 2012). The influences of age and gender were also analyzed: We hypothesized better mental health knowledge would be associated with higher age, and poorer mental health knowledge would be found in those identifying as male compared to female.

Method

Procedure

The study received approval by the local Institutional review board (LEK_98_17) and was approved from the Rhineland Palatinate supervisory school authority. We contacted 10 local schools for recruitment; four agreed to participate and six declined, citing lack of time as a reason. The inclusion criterion to participate in the study was being 12–21 years old. Psychology students were excluded as we expected a rather positive attitude toward psychotherapy among them. Participants were recruited from April 2017 to July 2017. We included all school classes that received a teacher’s consent to participate and included all participants who agreed to participate in the study. We recruited the sample in Germany from local secondary schools (86%) with 56% attending a college-preparatory track (preparation for higher education), vocational education institutions (6%), and the local university (11%).

Parents and adolescents were informed about the content and aims of the study. Written consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki from parents of children under the age of 15 years and from adolescents was mandatory for participation. In Rhineland Palatinate (Germany), when children from age 15 have the capacity of discernment, parental consent for study participation is not necessary. After an introduction from the researcher, participants completed the paper-and-pencil questionnaire. We did not give a definition of psychotherapy in advance to avoid eliciting a response bias. We were interested in attitudes associated with the term “psychotherapy” to ensure the ecological validity of the attitudes. We paid attention to creating a calm working atmosphere and sufficient privacy. Participants did not receive compensation.

Participants

A total of 288 adolescents (37% identified themselves as male, 63% as female, and 0% as nonbinary), age 12 to 21 years (M = 16.78 years, SD = 2.32) participated in this study.

Measures

Qualitative assessment: attitudes toward people with mental disorders and barriers to seeking psychotherapy

Potential barriers to seeking psychological help were assessed with one question: “In the event of mental health problems, I wouldn’t initiate psychotherapy, because….” To assess attitudes toward people with a mental disorder, the adolescents were asked to complete the sentence: “What I think about people with a mental disorder is that….”.

Quantitative assessment: barriers to seeking psychotherapy

For the development of the quantitative assessment, we conducted a literature review on attitudes toward people with a mental disorder and psychotherapy as well as other perceived barriers to seeking mental health care. Eighteen statements were extracted for a questionnaire and two items were added asking about participants’ subjective knowledge of mental disorders and if they were currently affected by mental health problems. In a pilot study, adolescents (n = 9) rated the questionnaire items on comprehensibility and these were revised on the basis of their feedback. The participants were asked to rate the statements on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree; 6 = totally agree).

To further investigate the number of constructs and the structure of the questionnaire, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis. A three-factor solution was recommended: Negative attitudes toward people with a mental disorder and psychotherapy (Items 7–9, 14–16), desire for social distance (Items 10, 11 and 16), and the optimism bias (Items 12 and 13) revealed a good fit with χ2(187) = 63.59, p = 0.13; the root-mean-square residual was 0.04, the Bayesian information criterion was −227.92, the Tucker–Lewis index was 0.941, and the root-mean-square-error of approximation was 0.031. Factor loadings are reported in Table 1. Internal consistency was, however, questionable for the stigma scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.62) and the desire for social distance scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.61), and unacceptable (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.39) for the optimism bias scale.

Furthermore, we asked participants to rate their anticipated probability of initiating psychotherapy in the event of serious mental health problems (0–100%) and to indicate if they had ever had contact with a psychologist or psychotherapist, if they had current or past experience with psychotherapy themselves, and if they knew of a friend or family member who had current or past experience with psychotherapy. They also rated whether the experience (or reported experience) was positive or negative.

Psychotherapy knowledge

We assessed psychotherapy knowledge with 11 items concerning knowledge about mental disorders and the process of psychotherapy. The statements were rated for correctness by six licensed psychotherapists in two steps. First, we used Fleiss’s kappa to measure interrater reliability. We found κ = 1 (perfect agreement) for all items except Item 1 (κ = 0.5) and Item 5 (κ = 0.33). These two items were then revised and rated again, resulting in perfect interrater agreement of κ = 1 for all statements. The participants were asked to indicate if the statements were true or false or to indicate that they did not know the answer (“I don’t know”). The items are presented in Table 2.

Social desirability bias

We assessed social desirability bias with the short version of the Scale for Detecting Test Manipulation Through Faking Good and Social Desirability Bias (Satow 2012) which consists of two items rated on a Likert scale (1 = highly agree; 4 = highly disagree). A total score of 7 or 8 points is considered significant evidence of social desirability bias. Reliability for our sample (a questionable Cronbach’s alpha of 0.56) was comparable to that in Satow (2012; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.59).

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

The data set of the adolescents’ statements about attitudes toward people with a mental disorder and potential barriers to seeking psychotherapy in the event of mental health problems were imported into MAXQDA Analytics Pro for data analysis, and a coding system was developed to assign the statements to different categories. In a second step, the coding system was applied by six independent raters. Interrater reliabilities for the different categories were calculated by using Fleiss’s kappa (Fleiss et al., 2003). We then calculated the percentages of the reported categories for each question.

We calculated the total score for psychotherapy knowledge as the number of correct answers (correct answer = 1; wrong answer or “I don’t know” = 0). Means and standard deviations for the assessment of barriers to seeking psychotherapy were calculated, with positive items reversed (Items 1, 2, 11). Statistical analyses were conducted with R (version 1.3.1056). Multiple regression analyses were used to test if psychotherapy knowledge, desire for social distance, the optimism bias, barriers to seeking psychotherapy, and stigma scores significantly predicted the intention to initiate psychotherapy in the event of serious mental health problems. We calculated a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with the barriers, psychotherapy, stigma scores, desire for social distance, and the optimism bias as dependent variables and current or past experience of psychotherapy, contact with a psychologist or psychotherapist, and knowledge of a person with current or past experience with psychotherapy as between-subjects variables.

Results

Qualitative Analyses: Barriers to Seeking Psychological Help and Attitudes Toward People with a Mental Disorder

Fear of negative interaction with the psychotherapist, the impression of having enough informal resources to cope with mental health problems otherwise, and the fear of being confronted with their own emotions were the most reported barriers to seeking psychological help. The categories, frequencies, and interrater reliabilities (Fleiss’s κ) are reported in Table 3.

Quantitative Assessment: Barriers to Seeking Psychotherapy

Regarding attitudes toward people with a mental disorder and barriers to initiating psychotherapy in the event of mental health problems, we report means and standard deviations as well as their correlations with the intention to initiate psychotherapy in Table 4. The mean anticipated probability of initiating psychotherapy in the event of a mental health problem was 50.56% (SD = 20.62%, Min = 0%, Max = 100%).

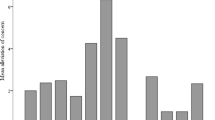

Psychotherapy Knowledge and Social Desirability Bias

The percentages of correct, incorrect, and “don’t know” psychotherapy knowledge questions are reported in Table 2, revealing deficits and a lack of knowledge for all categories. Social desirability scores were comparable to those of Satow (2012) with M = 3.00 (SD = 1.10) and under the cutoff (<7) of what is considered significant evidence of social desirability bias.

The Impact of Barriers on the Intention to Initiate Psychotherapy in the Event of Mental Health Problems

Multiple regression revealed a significant influence of psychotherapy knowledge, desire for social distance, and specific barriers to seeking psychotherapy as predictors of the anticipated intention to initiate psychotherapy in the event of mental health problems, R2 = 0.41, F(14, 220) = 10.92, p < 0.01. Lack of accessibility, in our case lack of contact addresses (β = −0.13, p = 0.02) and lack of time (β = −0.17, p < 0.01), lack of trust (β = 0.13, p = 0.03), desire for social distance (β = 0.13, p = 0.03), and negative attitudes toward people with a mental disorder (β = −0.36, p < 0.01) predicted a lower intention to initiate psychotherapy in the event of mental health problems. In contrast, poor psychotherapy knowledge (β = −0.03, p = 0.60), concerns about career (β = −0.09, p = 0.17), shame (β = 0.10, p = 0.09), fear of parental stigmatization (s = 0.01, p = 0.89), a preference for seeking help from friends and family members (β = 0.10, p = 0.08), concerns related to the age gap (β = −0.08, p = 0.24), the optimism bias (β = −0.08, p = 0.24), and social desirability bias (β = 0.10, p = 0.08) did not have an impact on help-seeking intentions.

The Impact of Personal Experience with a Psychotherapist, Age, and Gender

Thirty-four percent of the participants reported at least one personal encounter with a psychologist or psychotherapist, and 76% rated the contact as positive. Seventeen percent reported the experience of current or past psychotherapy with a positive evaluation of 65%. Sixty-six percent knew someone in their family who had initiated psychotherapy, and 77% of them reported the experience as positive.

A MANOVA with barriers, psychotherapy knowledge, stigma scores, desire for social distance, and the optimism bias indicted differences in adolescents with current or past experience of psychotherapy or contact with a psychologist or psychotherapist, F(12, 283) = 5.08, p < 0.01, compared to adolescents without this experience. Post hoc tests indicated better knowledge of contact addresses, F(12, 283) = 11.83, p < 0.01, better psychotherapy knowledge scores, F(13, 283) = 4.52, p = 0.03, lower social distance scores, F(12, 283) = 5.30, p = 0.02, and lower optimism bias, F(12, 283) = 32.98, p < 0.01, for adolescents with current or past experience with a psychologist or a psychotherapist and no differences for lack of time, F(12, 283) = 2.05, p = 0.15, preference for alternative treatment (e.g., family, friends), F(12, 283) = 3.75, p = 0.05, worries about effect on career, F(12, 283) = 0.49, p = 0.49, shame, F(12, 283) = 0.12, p = 0.74, concerns about the age gap, F(12, 283) = 1.09, p = 0.30, lack of trust, F(12, 283) = 0.05, p = 0.82, fear of parental stigmatization, F(12, 283) = 2.87, p = 0.09, and stigma scores, F(12, 283) = 0.39, p = 0.54.

We also found significant differences between adolescents who had a family member or friend in psychotherapy, F(12, 244) = 4.30, p < 0.01, and those who did not, with lower shame, F(12, 283) = 4.08, p = 0.04, lower fear of parental stigmatization, F(12, 283) = 4.38, p = 0.02, better psychotherapy knowledge, F(12, 283) = 15.39, p > 0.01, and lower optimism bias, F(12, 283) = 6.11, p = 0.01, for the former. The other barriers were not significant.

We also analyzed the influence of age as a covariate, F(5, 230) = 32.14, p < 0.01, and gender as a fixed factor and found a significant impact on our dependent variables, F(5, 230) = 5.45, p < 0.01. Higher age was associated with better psychotherapy knowledge, F(5, 230) = 58.07, p < 0.01. Male participants reported higher social distance, F(5, 230) = 7.78, p = 0.01, higher optimism bias, F(5, 230) = 18.63, p < 0.01, and poorer psychotherapy knowledge, F(5, 230) = 7.80, p = 0.01, compared to female participants.

Discussion

The mixed-methods study using a convergent parallel design allowed a more comprehensive account of barriers specifically to psychotherapy in an adolescent sample. The use of a qualitative design revealed fear of a negative interaction with a psychotherapist, the conviction of having enough resources to cope with mental health problems without professional help, and the fear of being confronted with their own emotions were the main cited barriers to seeking psychotherapy, which is consistent with other findings (Aguirre-Velasco et al., 2020; Gulliver et al., 2010). Those barriers should be further investigated, and they might be highly relevant in a quantitative assessment of barriers to psychotherapy.

In terms of the quantitative assessment, poor psychotherapy knowledge, concerns about their future career, shame, fear of parental stigmatization, a preference for seeking help from friends and family members, concerns related to the age gap, and the optimism bias did not predict a lower intention to initiate psychotherapy. We also found deficits in psychotherapy knowledge. Higher age and female gender were as expected associated with higher psychotherapy knowledge (Farrer et al., 2008). Current or past experience with a psychologist or psychotherapy, as well as knowing a friend or family member in psychotherapy, was associated with better psychotherapy knowledge and lower optimism bias, probably because psychotherapy is associated with an increase in self-efficacy in improving and maintaining one’s mental health (Wahl et al., 2012). The decreased optimism bias was also expected, as in most cases, adolescents with current or past experience of psychotherapy probably had experienced or were currently experiencing psychological symptoms serious enough to prompt the initiation of psychotherapy. Adolescents who knew a family member or friend in psychotherapy also reported reduced shame and fear of parental stigmatization, as well as better psychotherapy knowledge and lower optimism bias. Adolescents with past or current experience of psychotherapy did not differ in stigma scores from those without this experience. However, stigma rates were generally low in this sample, with a mean tendency to reject the statement of negative attitudes toward people with mental disorders even when controlling for social desirability bias. This result is comparable to other findings assessing negative attitudes toward people with a mental disorder in adolescent samples (Kuhl et al., 1997; Lauber et al., 2004) and might be why stigma rates in those who had had contact were not lower compared to those who had not, as they were low in general. Consistent with other findings, we found that a desire for social distance (Mackenzie et al., 2004) and the optimism bias (McNeish et al., 2020) were more pronounced in male than female adolescents. McNeish et al. (2020) concluded in their review of media coverage of the mental health of men and boys that the mental health issues unique to men and boys are not adequately represented, which might lead to a higher desire for social distance and the optimism bias. Another issue is that subjective masculine norms often encourage men and boys to suppress their emotions instead of seeking help (Smith et al., 2008), which might also account for the lower optimism bias scores compared to the female sample.

Limitations and Strengths

The questionnaire for the quantitative assessment should be revised and psychometric properties, such as validity, test–retest reliability, and acceptance of the questionnaire, should again be assessed to ensure the age appropriateness of the measure. As Cronbach’s alpha for the optimism bias scale was unacceptable and consisted of a two-item scale, the results presented must be interpreted with caution. A descriptive approach, however, might be suitable to address specific barriers in the help-seeking process or at the beginning of the treatment. A future study should also adopt the approach of modifying existing measures rather than creating new scales (Pepin et al., 2015).

The measure also assesses the intention to initiate psychotherapy and does not assess actual behavior. The help-seeking intentions were removed from the context of actual serious mental health problems with significant impairment, suffering, and reduction of life quality, which might change help-seeking attitudes compared to a situation with fewer symptoms. Given the sample size, gender, age, and education differences, the generalizability (external validity) of the results is also limited. The rationale for excluding psychology students is not evidence based and should be reconsidered in a future study. Furthermore, psychotherapy settings and conditions vary between cultures, which also limits generalizability. In Germany, psychotherapy is covered by health insurance, which might be a facilitator of seeking psychotherapy that is not the case in other countries.

Conclusions and Implications

Integrating results from both approaches delivers further information for the enhancement of prevention programs and interventions designed to lower barriers to seeking psychotherapy. First, interventions might focus on a reduction of fear of the psychotherapy setting by increasing psychotherapy knowledge and transparency about the psychotherapy setting, including handling the fear of being overwhelmed by aversive emotions or the fear of losing control. Psychoeducation interventions might emphasize that patients play an active part in the process of psychotherapy, maintain self-determination and control of their decisions and actions, and are treated with respect. Further research should investigate whether the conviction of being able to cope with mental health problems without professional help refers to self-efficacy or rather to an optimism bias. Those findings strengthen the need for interventions that focus on the increase of mental health literacy, enabling people to recognize psychopathology and the need for professional help. Further, the data suggest that interventions are needed that provide information about psychotherapy (e.g., contact addresses, information about the setting, legal aspects) and mental disorders to increase psychotherapy knowledge and to reduce fear and stigmatizing attitudes toward initiating psychotherapy. The results also strengthen the need for interventions initiating contact (Evans-Lacko et al., 2013) with people who have experienced psychotherapy and the encouragement of self-disclosure within the family and a person’s social network when engaging in psychotherapy. The results of this study also suggest the necessity of content that may be tailored to different genders (Calear et al., 2017), but how such interventions might lower barriers to seeking psychotherapy is under-researched (Smith et al., 2018) and should be further investigated. Finally, research is needed to study moderators and mediators of the barriers to seeking psychotherapy in the event of mental health problems.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Addis, M. E., & Mahalik, J. R. (2003). Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychologist, 58(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.5.

Aguirre Velasco, A., Cruz, I. S. S., Billings, J., Jimenez, M., & Rowe, S. (2020). What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02659-0

Albani, C., Blaser, G. B, & Brähler, E. (2014). Psychotherapie: Mit der Erfahrung kommt die Akzeptanz. https://www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/159671/Psychotherapie-Mit-der-Erfahrung-kommt-die-Akzeptanz

American Psychological Association (n.d.) APA Dictionary of Psychology. Retrieved February 12, 2022, from: https://dictionary.apa.org/psychotherapy.

Andrade, L. H., Alonso, J., Mneimneh, Z., Wells, J. E., Al-Hamzawi, A., Borges, G., Bromet, E., Bruffaerts, R., de Girolamo, G., de Graaf, R., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Hinkov, H. R., Hu, C., Huang, Y., Hwang, I., Jin, R., Karam, E. G., Kovess-Masfety, V., & Kessler, R. C. (2014). Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychological Medicine, 44(6), 1303–1317. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713001943.

Bellanca, F., & Pote, H. (2013). Children’s attitudes towards ADHD, depression and learning disabilities. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2012.01263.x

Bilican, F. I. (2013). Help-seeking attitudes and behaviors regarding mental health among turkish college students. International Journal of Mental Health, 42(2–3), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.2753/IMH0020-7411420203.

Bryman, A. (2006). Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: how is it done? Qualitative Research, 6(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794106058877.

Cakar, F. S., & Savi, S. (2014). An exploratory study of adolescent’s help-seeking sources. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 159, 610–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.434.

Calear, A. L., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2011). Personal and perceived depression stigma in Australian adolescents: magnitude and predictors. Journal of Affective Disorders, 129(1–3), 104–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.019.

Calear, A. L., Banfield, M., Batterham, P. J., Morse, A. R., Forbes, O., Carron-Arthur, B., & Fisk, M. (2017). Silence is deadly: A cluster-randomised controlled trial of a mental health help-seeking intervention for young men. BMC Public Health, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4845-z

Chandra, A., & Minkovitz, C. S. (2006). Stigma starts early: gender differences in teen willingness to use mental health services. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 38(6), 754.e1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.011.

Christiana, J. M., Gilman, S. E., Guardino, M., Mickelson, K., Morselli, P. L., Olfson, M., & Kessler, R. C. (2000). Duration between onset and time of obtaining initial treatment among people with anxiety and mood disorders: an international survey of members of mental health patient advocate groups. Psychological Medicine, 30(3), 693–703. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291799002093.

Clement, S., Schauman, O., Graham, T., Maggioni, F., Evans-Lacko, S., Bezborodovs, N., Morgan, C., Rüsch, N., Brown, J. S. L., & Thornicroft, G. (2015). What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine, 45(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714000129.

Creswell, J., & Plano Clark, V. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE publications. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2007.00096.x

Divin, N., Harper, P., Curran, E., Corry, D., & Leavey, G. (2018). Help-seeking measures and their use in adolescents: a systematic review. Adolescent Research Review, 3(1), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-017-0078-8.

Evans-Lacko, S., Malcolm, E., West, K., Rose, D., London, J., Japhet, S., Little, K., Henderson, C., & Thornicroft, G. (2013). 3016 – How can we use social contact interventions to reduce stigma and discrimination against people with mental health problems? European Psychiatry, 28, 1 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(13)77522-9.

Farrer, L., Leach, L., Griffiths, K. M., Christensen, H., & Jorm, A. F. (2008). Age differences in mental health literacy. BMC Public Health, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-125

Fleiss, J., Levin, B., & Paik, C. M. (2003). The Measurement of Interrater Agreement. In Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions (pp. 598–626). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471445428.ch18

Fleming, J. E., & Offord, D. R. (1990). Epidemiology of childhood depressive disorders: a critical review. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(4), 571–580. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199007000-00010.

Furlonger, B., Papadopoulos, A., Chow, A. P., & Zhu, Y. (2015). The portrayal of counselling on television and YouTube: implications for professional counsellors. Journal of Behavioural Sciences, 25(2), 1–24.

Gabbard, G. O. (2001). Psychotherapy in Hollywood cinema. Australasian Psychiatry, 9(4), 365–369. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1665.2001.00365.x.

Gonzalez, J. M., Alegria, M., & Prihoda, T. J. (2005). How do attitudes toward mental health treatment vary by age, gender, and ethnicity/race in young adults? Journal of Community Psychology, 33(5), 611–629. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20071.

Gore, F. M., Bloem, P. J., Patton, G. C., Ferguson, J., Joseph, V., Coffey, C., Sawyer, S. M., & Mathers, C. D. (2011). Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: a systematic analysis. The Lancet, 377(9783), 2093–2102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60512-6.

Griffiths, K. M., Christensen, H., & Jorm, A. F. (2008). Predictors of depression stigma. BMC Psychiatry, 8(1), 25 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-8-25.

Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2010). Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-113

Henderson, C., Evans-Lacko, S., Flach, C., & Thornicroft, G. (2012). Responses to mental health stigma questions: The importance of social desirability and data collection method. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57(3), 152–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371205700304.

Hintzpeter, B., Metzner, F., Pawils, S., Bichmann, H., Kamtsiuris, P., Ravens-Sieberer, U., & Klasen, F., group, T. B. study. (2014). Inanspruchnahme von ärztlichen und psychotherapeutischen Leistungen durch Kinder und Jugendliche mit psychischen Auffälligkeiten: Ergebnisse der BELLA-Studie. Kindheit und Entwicklung, 23(4), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1026/0942-5403/a000148.

Jorm, A. F., & Oh, E. (2009). Desire for social distance from people with mental disorders. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43(3), 183–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670802653349.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593.

Kuhl, J., Jarkon-Horlick, L., & Morrissey, R. F. (1997). Measuring barriers to help-seeking behavior in adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 26(6), 637–650. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022367807715.

Lambert, M., Bock, T., Naber, D., Löwe, B., Schulte-Markwort, M., Schäfer, I., Gumz, A., Degkwitz, P., Schulte, B., König, H., Konnopka, A., Bauer, M., Bechdolf, A., Correll, C., Juckel, G., Klosterkötter, J., Leopold, K., Pfennig, A., & Karow, A. (2013). Die psychische Gesundheit von Kindern, Jugendlichen und jungen Erwachsenen – Teil 1: Häufigkeit, Störungspersistenz, Belastungsfaktoren, Service-Inanspruchnahme und Behandlungsverzögerung mit Konsequenzen. Fortschritte der Neurologie · Psychiatrie, 81(11), 614–627. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1355843.

Lauber, C., Nordt, C., Falcato, L., & Rössler, W. (2004). Factors influencing social distance toward people with mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 40(3), 265–274. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:COMH.0000026999.87728.2d.

Lu, W. (2020). Treatment for adolescent depression: National patterns, temporal trends, and factors related to service use across settings. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(3), 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.019.

Mackenzie, C. S., Knox, V. J., Gekoski, W. L., & Macaulay, H. L. (2004). An adaptation and extension of the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help scale. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(11), 2410–2433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb01984.x.

Maier, J. A., Gentile, D. A., Vogel, D. L., & Kaplan, S. A. (2014). Media influences on self-stigma of seeking psychological services: the importance of media portrayals and person perception. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 3(4), 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034504.

Marshall, M., Lewis, S., Lockwood, A., Drake, R., Jones, P., & Croudace, T. (2005). Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(9), 975 https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.975.

McNeish, R., Rigg, K.K., Delva, J., Schadrac, D., Walsh, S., Turvey, C., & Borde, C. (2020). Media coverage of the mental health of men and boys. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19, 1274–1283.

Merikangas, K. R., He, J., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., Benjet, C., Georgiades, K., & Swendsen, J. (2010a). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. Adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017.

Mittal, D., Ounpraseuth, S. T., Reaves, C., Chekuri, L., Han, X., Corrigan, P., & Sullivan, G. (2016). Providers’ personal and professional contact with persons with mental illness: Relationship to clinical expectations. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 67(1), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400455.

Mohr, D. C., Hart, S. L., Howard, I., Julian, L., Vella, L., Catledge, C., & Feldman, M. D. (2006). Barriers to psychotherapy among depressed and nondepressed primary care patients. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 32(3), 254–258. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm3203_12.

Mojtabai, R., Olfson, M., Sampson, N. A., Jin, R., Druss, B., Wang, P. S., Wells, K. B., Pincus, H. A., & Kessler, R. C. (2011). Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine, 41(8), 1751–1761. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710002291.

Moses, T. (2009). Stigma and self-concept among adolescents receiving mental health treatment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(2), 261–274. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015696.

Oliver, M. I., Pearson, N., Coe, N., & Gunnell, D. (2005). Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: cross-sectional study. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 186, 297–301. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.4.297.

Pearl, R., Forgeard, M., Rifkin, L., Beard, C., & Björgvinsson, T. (2016). Internalized stigma of mental illness: changes and associations with treatment outcomes. Stigma and Health, 2. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000036

Pepin, R., Segal, D. L., & Coolidge, F. L. (2009). Intrinsic and extrinsic barriers to mental health care among community-dwelling younger and older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 13(5), 769–777. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860902918231.

Pepin, R., Segal, D. L., Klebe, K. J., Coolidge, F. L., Krakowiak, K. M., & Bartels, S. J. (2015). The barriers to mental health services scale revised: psychometric analysis among older adults. Mental Health & Prevention, 3(4), 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2015.09.001.

Petrowski, K., Hessel, A., Körner, A., Weidner, K., Brähler, E., & Hinz, A. (2014). Attitudes toward psychotherapy in the general population. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie, 64(2), 82–85. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1361155.

Rickwood, D. J., Deane, F. P., & Wilson, C. J. (2007). When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? Medical Journal of Australia, 187(S7). https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01334.x.

Satow, L. (2012). Skala zur Erfassung von Testverfälschung durch positive Selbstdarstellung und sozialerwünschte Antworttendenzen (SEA). www.psychomeda.de

Sawyer, M. G., Borojevic, N., Ettridge, K. A., Spence, S. H., Sheffield, J., & Lynch, J. (2012). Do help-seeking intentions during early adolescence vary for adolescents experiencing different levels of depressive symptoms? Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(3), 236–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.06.009.

Schnyder, N., Panczak, R., Groth, N., & Schultze-Lutter, F. (2017). Association between mental health-related stigma and active help-seeking: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(4), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.189464.

Schomerus, G., Stolzenburg, S., Freitag, S., Speerforck, S., Janowitz, D., Evans-Lacko, S., Muehlan, H., & Schmidt, S. (2019). Stigma as a barrier to recognizing personal mental illness and seeking help: a prospective study among untreated persons with mental illness. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 269(4), 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-018-0896-0.

Smith, J. P., Tran, G. Q., & Thompson, R. D. (2008). Can the theory of planned behavior help explain men’s psychological help-seeking? Evidence for a mediation effect and clinical implications. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 9(3), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012158.

Spendelow, J. S., & Jose, P. E. (2010). Does the optimism bias affect help-seeking intentions for depressive symptoms in young people. The Journal of General Psychology, 137(2), 190–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221301003645277.

Swords, L., Heary, C., & Hennessy, E. (2011). Factors associated with acceptance of peers with mental health problems in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(9), 933–941. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02351.x.

van Beljouw, I., Verhaak, P., Prins, M., Cuijpers, P., Penninx, B., & Bensing, J. (2010). Reasons and determinants for not receiving treatment for common mental disorders. 61(3), 8.

Wahl, O., Reiss, M., & Thompson, C. A. (2018). Film psychotherapy in the 21st century. Health Communication, 33(3), 238–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1255842.

Wahl, O., Susin, J., Lax, A., Kaplan, L., & Zatina, D. (2012). Knowledge and attitudes about mental illness: a survey of middle school students. Psychiatric Services, 63(7), 649–654. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100358.

Wahlin, T., & Deane, F. (2012). Discrepancies between parent- and adolescent-perceived problem severity and influences on help seeking from mental health services. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 46(6), 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412441929.

Wang, J., Fick, G., Adair, C., & Lai, D. (2007). Gender specific correlates of stigma toward depression in a Canadian general population sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 103(1–3), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.010.

Wang, P. S., Berglund, P. A., Olfson, M., & Kessler, R. C. (2004). Delays in initial treatment contact after first onset of a mental disorder. Health Services Research, 39(2), 393–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00234.x.

Wedding, D., & Niemiec, R. M. (2003). The clinical use of films in psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59(2), 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10142.

Weinstein, N. D., & Klein, W. M. (1996). Unrealistic optimism: present and future. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 15(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1996.15.1.1.

Wilson, C. J., Deane, F. P., Ciarrochi, J., & Rickwood, D. (2005). Measuring help-seeking intentions: properties of the general help-seeking questionnaire. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 39(1), 15–28.

Wilson, C., Rickwood, D., Ciarrochi, J., & Deane, F. (2002). Adolescent barriers to seeking professional psychololgical help for personal-emotional and suicidal problems. Undefined. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Adolescent-barriers-to-seeking-professional-help-Wilson-Rickwood/7783ec361864c5ae65481a7c153e1f3da46405c6.

Wittchen, H. U., Härtling, S., & Hoyer, J. (2015). Psychotherapy and mental health as a psychological science. Verhaltenstherapie, 25, 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1159/000430772.

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Schuster and L. Küttner for their support in the recruitment of participants.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Simone Pfeiffer and supervised by Tina In-Albon. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Simone Pfeiffer and both authors commented on all versions of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The study received approval by the local Institutional review board (LEK_98_17) and was approved from the Rhineland Palatinate supervisory school authority.

Informed Consent

Written consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki from parents of children under the age of 15 years and from adolescents was mandatory for participation. In Rhineland Palatinate (Germany), when children from age 15 have the capacity of discernment, parental consent for study participation is not necessary.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pfeiffer, S., In-Albon, T. Barriers to Seeking Psychotherapy for Mental Health Problems in Adolescents: a mixed method study. J Child Fam Stud 31, 2571–2581 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02364-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02364-4