Abstract

The present study examined how adolescents’ materialism relates to interpersonal materialism role models (i.e., mothers’, fathers’, siblings’, and peers’), media exposure, and family socio-economic status (SES). We obtained our data from the adolescent, his/her mother and father, and one each of his/her siblings and peers. The results showed that mother’s, father’s, sibling’s and peer’s’, materialism are approximately equally strong predictors of adolescents’ materialism. Further analyses, using structural equation modeling, revealed that interpersonal materialism role models and media exposure both positively predicted adolescents’ materialism; in contrast to past literature, family SES was also significantly positively related to adolescents’ materialism. Limitations and implications of the current project are discussed.

Highlights

-

Adolescents’ materialism is approximately equally strongly predicted by siblings’, peers’ and parents’ materialism.

-

Adolescents’ materialism is strongly positively related to interpersonal modeling (materialism of parents, siblings and peers), media exposure (TV and Internet) and, unexpectedly, family SES.

-

The role of family SES in adolescents’ materialism may depend on the cultural or national context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Adolescents’ materialism manifests itself in the desire to acquire and possess things, to have a lot of money in order to buy things, to have a well-paid job in the future that will earn enough money to buy whatever one wishes, and to be famous (Goldberg et al., 2003). Research conducted over the last few decades has shown that materialism has become a prominent ideology among adolescents, with wealth frequently topping lists of young people’s life aspirations (cf. Beutler, 2012; Cohen & Cohen, 1996; Schor, 2004; Twenge & Kasser, 2013). Unfortunately, however, numerous scientific publications also demonstrate that adolescents’ well-being is negatively correlated with the value that they place on materialistic aspirations (Cohen & Cohen, 1996; Kasser & Ryan, 1993; Kasser et al., 2014; Manolis & Roberts, 2012; Moldes & Ku, 2020). In addition, the more that adolescents prioritize materialistic aspirations, the lower their academic achievement (Ku et al. 2014), the more they envy other people (Goldberg et al. 2003), the more likely they are to engage in risky behaviors like smoking cigarettes and drinking alcohol (Williams et al. 2000), the more anti-socially they behave (Cohen & Cohen 1996; Kasser and Ryan 1993), and the less they engage in environmentally sustainable behaviors (Kasser 2005). Given this array of negative outcomes associated with a materialistic value orientation, it is important to understand how adolescents come to prioritize these aims in life.

The current article addresses two issues relevant to the development of materialism that have remained relatively unexplained in the literature. First, we investigate the relative strength of four distinct interpersonal models of materialism: the materialistic values of the adolescent’s mother, father, sibling, and close peer. To our knowledge, no investigators have obtained first-hand reports from all of these people in the adolescent’s life and examined their relative strength of association with the adolescent’s own materialism. Second, we analyze the relative power of not only these four interpersonal materialism role models, but also how adolescents’ materialism relates to their exposure to media and their family’s socio–economic status (SES). To our knowledge, no such comprehensive analysis of environmental variables of adolescents’ materialism has been undertaken so far. We examine these questions in a sample comprised of adolescents from Central Europe, a group underrepresented in the literature on adolescents’ materialism.

We organized our attempts to answer these questions around theories which suggest that materialism arises from two sources of experience (Inglehart, 1990; Kasser et al., 2004). The first source of materialism is the “formative social milieu” (see Ahuvia & Wong, 2002, pp. 392). The contemporary social milieu spreads materialistic standards (i.e., believing that money, possessions, image, and status assure a happy, meaningful, and secure life) by exposing adolescents to materialistic interpersonal role models (i.e., the values and lifestyles of family members and peers), as well as to materialistic messages transmitted by media and advertising (see Dittmar et al., 2008; Kasser et al., 2004; Zawadzka et al., 2021). The second source of materialism includes insecurity, threat (Chang & Arkin, 2002; Sheldon & Kasser, 2008; Ahuvia & Wong, 2002), and felt formative deprivation (Inglehart, 1990). Such experiences occur when an individual grows up in an economically, emotionally, or socially deprived environment that does a poor job of meeting his/her psychological and physical needs. In what follows, we provide a deeper review of what past research has shown about interpersonal role models and media, as well as family socioeconomic status.

Research into how families affect the development of adolescents’ value systems emphasizes the importance of parents as interpersonal role models whose hierarchy of values their adolescent children reproduce (Boehnke et al., 2002). Studies into value transmission in the family should also consider the sex of parents because mothers and fathers play different roles in shaping their child’s development. It is usually the mother with whom the child forms a primary bond—a matrix for future relationships (Bowlby, 1969)—that plays a very important role in life and also in the creation of a hierarchy of values (Kohn et al., 1986). Transmission of values in the mother–child dyad is thought to occur through bonding and identification with an emotionally important person (Parsons & Bales, 1956). Fathers pass on to the child values that are important to society through the formation of beliefs (Finley et al., 2008; Flouri, 2005). Research on how mothers’ and fathers’ values are associated with their children’s materialism paints a rather mixed picture. Some studies show the importance of mothers’ materialism (e.g., Flouri, 1999; Kasser et al., 1995), another suggests that both parents’ materialism matters (Goldberg et al., 2003), another finds that the paternal role model is more closely linked to adolescents’ materialism than is the maternal role model (Clark et al., 2001), and still others have found little to no influence of fathers’ materialism on adolescents’ materialism (Wojtowicz, 2013; Zawadzka & Dykalska-Bieck, 2013). Clearly more research is needed to help understand the respective roles of mothers and fathers.

Research on relationships among siblings’ materialistic values and attitudes is quite scarce. A single study conducted on adolescents and their teenage siblings demonstrated that they are similar in preferred values for extrinsic/materialistic goals (i.e., power, achievement, materialism), but only when they compete with each other (Kretschmer & Pike, 2010). Other relevant research shows that siblings influence their adolescent family members’ consumer choices, but that this influence is weaker than that of parents (Cotte & Wood, 2004).

During adolescence, the relationships of adolescents with their parents and peers change—the frequency and importance of contacts with peers increase, and thus the influence of peers tends to get stronger while parental influence tends to get weaker (Erikson, 1968). Indeed, peers become exceptionally important role models of adolescent attitudes and behavior (Brown, 2004). Research clearly show that adolescents imitate the behavior and attitudes of their friends and peers (Brechwald & Prinstein, 2011) and that peers are an important source of self-worth for adolescents (Klint & Weiss, 1986). Not surprisingly, then, adolescents learn materialism (i.e., emotional aspects of consumption) from their peers (Churchill & Moschis, 1979), and adolescent materialism is enhanced by both the normative influence of peers (Achenreiner, 1997; Chan & Prendergast, 2007, 2008) and social comparisons with peers (Chan & Prendergast, 2007, 2008). Several studies have shown that the more that adolescents are driven by the expectations and consumer choices of their peers, the more they believe that it is important to possess and acquire goods (Achenreiner, 1997; Chan & Prendergast, 2007, 2008; La Ferle & Chan, 2008; Roberts et al., 2008). Studies also show that materialism tends to be especially high among adolescents (Chaplin & John, 2010) and college students (Sheldon et al., 2000) whose peers also prioritize materialistic aspirations in life. Also, the experience of being rejected by peers strengthens materialistic beliefs of adolescents (Banerjee & Dittmar, 2008).

In brief summation, then, previous research indicates that adolescents’ materialism is linked to interpersonal role models of mothers’, fathers’, and peers’ materialism, but research into the relationship between adolescents’ materialism and their siblings’ materialism is scarce. Further, the past research is not clear as to which interpersonal role models are most strongly related to adolescents’ materialism.

In addition to interpersonal role models (like parents and peers), media exposure is another type of social modeling (Bandura, 1977). Both traditional media (like television) and newer media (like the Internet) are means of social communication that express and contribute to a culture of materialism. Research consistently reveals that the amount of time that adolescents spend watching television is significantly positively correlated with their preference for materialistic values (e.g., Benmoyal-Bouzaglo & Moschis, 2010; Bybee et al., 1985; Churchill and Moschis, 1979; Górnik-Durose, 2001; Moschis & Churchill, 1978). Although there is abundant research into the relation between television viewing and adolescents’ materialism, researchers have rarely focused on the relation between Internet use and adolescents’ materialism; if anything, the research looks into the use of social media (Kamal et al., 2013). Available studies also indicate that exposure to advertising in media is linked to preferences for materialistic values (Benmoyal-Bouzaglo & Moschis, 2010; Chan & Cai, 2009; Chia, 2010; Moschis & Moore, 1982); one study has, however, found nonsignificant relations (Chan, 2013). Importantly, longitudinal studies indicate that exposure to advertising strengthens preferences for materialistic values and that this effect is fully mediated by the desire to possess frequently advertised products (Opree et al., 2014). To our knowledge, however, investigators have yet to systematically investigate, in a single study, whether both interpersonal role models and media exposure are associated with adolescents’ materialism when the two forms of social modeling are jointly considered.

As noted above, in addition to modeling, feelings of threat or insecurity can also influence adolescents’ materialism. Low socio–economic status of the family is one way that children may feel insecure while growing up, especially in cultures that strongly value wealth (Kasser et al., 2004). This feeling of threat is thought to lead individuals to engage in a compensatory strategy by which they focus on valuing possessions and wealth as a means of demonstrating self-worth in a socially-validated manner (c.f. Ahuvia & Wong, 2002; Wang et al., 2020). Several studies show that adolescents’ materialistic aspirations are consistently negatively correlated with family income, wealth, and socio–economic status (Chaplin et al., 2014; Cohen & Cohen, 1996; Dittmar & Pepper, 1994; Kasser et al., 1995; Ku, 2015). An experimental manipulation that asked college students to imagine graduating in a time of economic downturn also caused increases in materialistic aspirations (Sheldon & Kasser, 2008). That said, more recent research shows that low socioeconomic status is linked to materialism only if lack of resources actually occurs (Roux et al., 2014). To our knowledge, however, the role of threat has rarely been examined in concert with all of the other social role models that might also be associated with adolescents’ materialism.

The Present Study

The present study fills three gaps in the literature on adolescents’ materialism. First, to our knowledge, few if any studies have compared the relative strength of relationships between adolescents’ materialism and the four interpersonal role models of mother, father, peer, and sibling; siblings in particular have been relatively ignored in past studies. We deferred predictions as to which interpersonal role model might be most strongly related to adolescents’ materialism, although (H1) we expected that peers’ and siblings’ materialism might explain adolescents’ materialism more strongly than would parents’ materialism, given the importance of same-age peers to the age group we studied.

Second, past studies that have examined how adolescents’ materialism relates to environmental variables have typically done so in a piecemeal fashion, examining only one or two of the known correlates of materialism. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to simultaneously examine the relative strength of interpersonal role models’ (i.e., the mother’s, father’s, sibling’s, and peer’s) materialism, media exposure, and an indicator of threat insecurity/threat (i.e., low SES). Given past studies, we hypothesized (H2) that adolescents’ materialism is positively correlated with interpersonal role models’ (i.e., the mother’s, father’s, sibling’s, and peer’s) materialism and media exposure (TV and the Internet) but that materialism would be higher in adolescents from low vs. high SES families. We again deferred predications as to which of these environmental variables would be most strongly associated with adolescents’ materialism.

The third important contribution of the current study is primarily methodological. Much of the available knowledge regarding adolescents’ materialism has been gathered by studies that used single measures of self-reported materialism and second-hand reports of other people’s levels of materialism. We improved on this methodology by using multiple measures of self-report materialism to create a more multidimensional, and hopefully valid, measure of materialism (cf. Kasser et al., 2014). In addition, we directly asked parents, siblings, and peers about their own levels of materialism, rather than relying on adolescents’ reports about the materialism levels of the important people in their lives.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The target sample consisted of 199 middle school students from an urban area of Northern Poland. They ranged from 13 to 16 years of age (M = 14.36, SD = 1.07); 53.3% were girls and 46.7% were boys. We also obtained data from 199 of the adolescents’ mothers (M maternal age = 41.73, SD = 4.06) and 199 of their fathers (M paternal age = 43.67, SD = 5.32). In the tested sample 57.8% (n = 115) of the parents were married to the target adolescent’s other parent, whereas 42.2% (n = 84) were divorced from the target adolescent’s other parent. Of this latter group, 86.90% of adolescents lived with their mother after the parents divorced. Current marital status of the surveyed divorced mothers was as follows: divorced/not in a relationship = 18.1%; remarried = 3.0%; in the midst of divorce = 2.5%; in partner relationship after divorce = 4.5%; missing data = 14.1%. Current marital status of the surveyed divorced fathers was as follows: divorced/not in a relationship = 16.1%; remarried = 1.5%; in the midst of divorce = 3.0%; in partner relationship after divorce = 8.5%; missing data = 13.1%. The households of 16.1% of the surveyed families had other adults apart from the parents living in them. The original intention of the authors of this manuscript was to include family structure as a correlate of materialism, and that is why the number of divorced families exceeds the representative sample of the population. However, due to the fact that divorced families included various subcategories whose numbers were insufficient for the requirements imposed in statistical analysis, family structure was excluded from the final analysis.

Data were also obtained from 199 of the target adolescents’ siblings in cases where siblings were between aged 11–19 years; we had two reasons for establishing this age criterion. First, we wanted to restrict potentially excessive age differences between siblings, as these could generate new, unintended variables that might affect the strength of the relationship between siblings’ materialism and the target adolescents’ materialism. Second, the materialism measures we used were developed specifically for adolescents. If an adolescent had more than one sibling within the specified age range, he/she was allowed to choose which sibling would take part in the project; 67.3% of the target adolescents had one sibling and 32.7% had two or more siblings. In the tested sample 52.8% of siblings were girls and 47.2% were boys; 2% were the same age as the target adolescent, 47.70% were younger than the target adolescent, and 50.30% were older than the target adolescent (M sibling age = 14.54, SD = 2.67). Data were also collected from 199 of the adolescents’ peers; each target adolescent had indicated which of their peers was their closest classmate; 57.3% of these were girls and 42.7% were boys (M peer age = 14.44, SD = 1.57).

Before the survey was conducted, we obtained approval from both the research ethics committee at the University of Gdańsk and the principals of the schools where students participated in the study. Each adolescent’s parents received an information letter describing the goals of the study and providing informed consent forms for the participation of their children and themselves. Target adolescents and their mothers, fathers, siblings, and peers filled out questionnaires in groups of 5–15 people. These questionnaires included questions about demographics and socio–economic status, as well as tools measuring materialism (see below); the order of scales was randomized.

Measures

Assessment of target adolescents’ materialism

We used three established measures to assess each target adolescent’s materialism. The first was a version of the Aspiration Index adapted for adolescents (AI; Kasser et al., 2014, Study 4), which includes 36 goals from 12 aspiration domains (Affiliation, Community Feeling, Conformity, Financial Success, Hedonism, Physical Appearance, Health, Popularity, Safety, Self-acceptance, Spirituality, & Savings) and asks adolescents to rate “How important has each goal been to you in the past month” on a 9-point scale (1 = Not at all important and 9 = Extremely important). Following past research on materialism (e.g., Dittmar et al., 2014), our focus here was on the importance adolescents placed on the three primary extrinsic (materialistic) domains of financial success (e.g., “I will have many expensive possessions”), popularity (e.g., “I will be admired by many people”), and physical appearance (e.g., “My image will be one that others find appealing”) relative to the three primary intrinsic domains of self-acceptance (e.g., “I will choose what I do, instead of being pushed along by life”), affiliation (e.g., “People will show affection to me, and I will to them”), and community feeling (e.g., “I will assist people who need it, asking nothing in return”). Scores on the three intrinsic domains were summed and subtracted from the sum of scores on the three extrinsic domains, yielding a Relative Extrinsic–Intrinsic Value Orientation (REIVO) score (α = 0.78); this variable reflects the relative importance that individuals place on extrinsic/materialistic vs. intrinsic/nonmaterialistic aspirations (cf. Kasser et al., 2014). The second measure of materialism was the Youth Materialism Scale (YMS; Goldberg et al., 2003; see also Zawadzka et al., 2020), which assesses positive and negative attitudes towards possessing material goods and the subjective importance adolescents place on owning material goods. The YMS includes 10 statements (e.g., “I’d rather spend time buying things than doing almost anything else”) that are rated on a 4-point scale (1 = I disagree completely and 4 = I agree completely) (α = 0.78). We created a single variable from the YMS. The third measure was the Consumer Involvement Scale (CIS; Bottomley et al., 2010), which consists of nine items arranged into three subscales: Dissatisfaction (CIS_DS; e.g., “I feel like other kids have more stuff than I do”; α = 0.82), Consumer Orientation (CIS_CO; e.g., “I usually have something in mind that I want to buy or get”, α = 0.49), and Brand Awareness (CIS_BA; e.g., “Brand names matter to me”, α = 0.84). Respondents rated the items on a 5-point scale (1 = I strongly disagree and 5 = I strongly agree). The CIS thus yielded three distinct variables to assess materialism.

As we were interested in creating a single multidimensional assessment of materialism (cf. Kasser et al., 2014), we tested whether the five variables (i.e., REIVO, YMS, CIS_DS, CIS_CO, CIS_BA) each were indicators of materialism by conducting a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), specifying a 1-factor solution. The results of the CFA indicated a good model fit for the data (χ2 (4) = 8.87, p < 0.07; CFI = 0.987; GFI = 0.982; and RMSEA = 0.078; PCLOSE = 0.20). Further supporting the creation of this single measure of materialism, all five variables had statistically significant loadings on the single factor (ranging from 0.56 to 0.90). McDonald’s ω (see Deng & Chan, 2017) for the summed variables was ω = 0.83. We therefore standardized the scores on the five variables and averaged them to create a single measure of the target adolescents’ materialism.

Assessment of siblings’ and peers’ materialism

We used the same procedures as for the target adolescent to measure his/her siblings’ and peers’ materialism. That is, siblings and peers completed the AI for adolescents (Kasser et al., 2014) (REIVO siblings α = 0.81; REIVO peers α = 0.63), the YMS (Goldberg et al., 2003) (YMS siblings α = 0.80; YMS peers α = 0.83), and the CIS (Bottomley et al., 2010) (CIS_DS siblings α = 0.83, CIS_CO siblings α = 0.56, CIS_BA siblings α = 0.85; CIS_DS peers α = 0.82, CIS_CO peers α = 0.52, CIS_BA peers α = 0.87). The same rating and calculation procedures were used as in the assessment of the target adolescent. The results of CFA for one-factor solutions for siblings’ and peers’ materialism including all five variables (i.e., REIVO, YMS, CIS_DS, CIS_CO, CIS_BA) indicated an acceptable model fit for both the siblings (χ2 (4) = 4.44, p < 0.22; CFI = 0.996; GFI = 0.991; and RMSEA = 0.05; PCLOSE = 0.47) and for the peers (χ2 (3) = 7.49, p < 0.06; CFI = 0.980; GFI = 0.986; and RMSEA = 0.09; PCLOSE = 0.17). Also, all variables had statistically significant loadings on each single factor (for siblings, loadings ranged from 0.46 to 0.85; for peers, loadings ranged from 0.25–0.83). McDonald’s ω for summed variables was ω = 0.82 for siblings and ω = 0.78 for peers. As such, we once again standardized the five relevant scores for each individual and averaged them in order to obtain sibling and peer measures of materialism.

Assessment of mothers’ and fathers’ materialism

We used two questionnaires developed for adults to assess the materialism of the target adolescents’ mothers and fathers. The first was a slightly different version of the Aspiration Index (Kasser et al., 2014, Study 2; see also Zawadzka et al., 2015) than the target adolescent completed. The parents’ AI included 35 goals that assessed the same three extrinsic (materialistic) and the same three intrinsic (nonmaterialistic) aspirations as for the adolescents; five items also assessed health aspirations (e.g., “to be fit and healthy”) but were not used here. Respondents were asked to answer the question “How important is each goal to you?” by rating each item on a 7-point scale (1 = Not at all important and 7 = Very important). Following the same procedure as for the adolescents, we created a REIVO score, which reflects the relative importance that individuals place on extrinsic/materialistic vs. intrinsic/nonmaterialistic aspirations (cf. Kasser et al. 2014) (REIVO mothers α = 0.78; REIVO fathers α = 0.81). Mothers and fathers also completed the Short version of the Material Values Scale (MVS, Richins & Dawson, 1992; see also Górnik-Durose, 2016), which assesses attitudes towards possessing material goods and the subjective importance of goods. The scale includes 9 statements across three subscales: Centrality (e.g., “I enjoy spending money on things that aren’t practical”), Success (e.g., “I admire people who own expensive homes, cars and clothes”), and Happiness (e.g., “My life would be better if I owned certain things I don’t have”). Respondents rated the statements on a 5-point scale (1 = I completely disagree and 5 = I completely agree) (MVS_centrality mother α = 0.57, MVS_success mother α = 0.62, MVS_happiness mother α = 0.77; MVS_centrality father α = 0.60, MVS_success father α = 0.70, MVS_happiness father α = 0.74). We created three variables each for the mother and father, reflecting the three subscales. To test whether these four variables (i.e., REIVO, MVS_centrality, MVS_success, MVS_happiness) each reflected an underlying construct of materialism, we again conducted CFAs using AMOS 23, specifying a one-factor solution. Acceptable model fits for the data were obtained for mothers (χ2 (2) = 2.64, p < 0.27; CFI = 0.997; GFI = 0.993; and RMSEA = 0.04; PCLOSE = 0.43) and fathers (χ2 (2) = 4.66, p < 0.10; CFI = 0.988; GFI = 0.989; and RMSEA = 0.08; PCLOSE = 0.21). Also, all variables had statistically significant loadings on the single factors (ranging from 0.56 to 0.79 for mothers and from 0.64 to 0.85 for fathers). McDonald’s ω for summed variables was ω = 0.76 for mothers and was ω = 0.80 for fathers. We therefore standardized the relevant scores on the four variables and averaged them together to obtain separate measures of mothers’ materialism and of fathers’ materialism.

Measures of Advertising Exposure Frequency and Social Media Usage

Target adolescents were asked to answer questions related to their frequency of viewing TV and using the Internet via a method inspired by Schor (2004) and implemented by Nairn et al. (2007). We measured these two (i.e., traditional and newer) types of media separately since they serve different purposes. While TV viewers have a limited choice within the mass content they are exposed to, Internet users’ choice is practically unlimited. What is more, TV is mainly a source of fun and entertainment whereas the Internet can also be a platform for educational tasks (cf. Leckenby, 2005; Nairn et al., 2007). Using a 5-point scale (1 = Never and 5 = Always), target adolescents first indicated how often they watch television and use the Internet on weekdays at five specific times of day (i.e., before school, after school, during dinner, after dinner, and in bed before sleep); next, using the same 5-point rating scale, they rated how often they engaged in these same two activities on the weekend at six specific times of day (i.e., in the morning, during lunch, in the afternoon, during dinner, after dinner, in bed before sleep). Next, we separately summed the weekday and weekend ratings of exposure to television and of use of the Internet to create two scores of media exposure: weekly exposure to TV and weekly exposure to the Internet.

Measures of Socio–economic Status

Three measures were used to assess family socio–economic status (SES). The first one was net monthly household income reported by parents (M = PL 6217.55 (SD = 2913.13)). The second and third were the education level of mother and father respectively. We asked mothers and fathers to report on their educational level, using the following scale: 1 = primary school, 2 = vocational school, 3 = high school, 4 = Bachelor’s degree, 5 = Master’s degree or above. 0% of the fathers and mothers had only a primary school education, 10.1% of the mothers and 19.6% of the fathers had a vocational education, 25.1% of the mothers and 24.1% of the fathers had a secondary education, 11.6% of the mothers and 6.5% of the fathers had a Bachelor’s degree, and 52.3% of the mothers and 48.7% of the fathers had a Master’s degree or above. Notably, because full information on income was lacking for 23 individuals from the database, we removed these individuals from the SEM analyses reported below.

Results

Attrition Analyses

Attrition analyses examined whether the 23 parents who had not reported family income level differed from those parents who had. The analyses showed that there were no significant differences in parents’ education levels between the two groups (father’s education t(197) = −0.68, p = 0.50, 95% CI [−0.58, 0.34], and mother’s education t(197) = −0.21, p = 0.83, 95% CI [−0.54, 0.49]). However, parents who did not report family income levels had lower materialism levels than did those who reported family income levels (father’s materialism t(197) = 2.73, p = 0.003. 95%CI [0.40, 3.16], and mother’s materialism t(197) = 3.04, p = 0.001, 95% CI [0.76, 3.22]). Further, the 23 mothers/fathers who did not report family income levels were mainly from intact families (87%) (χ2(1) = 9.07, p = 0.003). Summing up, the analyzed sample for SEM analyses, without the sets of data not including family income levels, was more materialistic and more varied in family structure than the sample including all sets of data.

Preliminary Analysis

Table 1 displays correlations among all studied variables. The target adolescents’ materialism was significantly positively statistically correlated with all four interpersonal role models’ (i.e., the mother’s, father’s, sibling’s, and peer’s) materialism as well as media exposure (TV and the Internet); it was unrelated to family SES (i.e., family income, mother’s education, father’s education), the adolescent’s sex, and the adolescent’s age.

Adolescents’ Materialism and Specific Interpersonal Role Models

We conducted a linear regression analysis (method: enter) to determine which of the four interpersonal materialism role models were the strongest predictors of the adolescents’ materialism. Doing so allowed us to test the tentative hypothesis that peers’ and siblings’ materialism are more closely associated with adolescents’ materialism than are either parents’ materialism. When all four variables were entered as predictors (along with the target adolescents’ sex and age as covariates), a significant amount of the variance in the target adolescents’ materialism was accounted for (R = 0.56, R2 = 0.32, Adjusted R2 = 0.30, F(6,190) = 14.80, p < 0.001). As Table 2 shows, neither target adolescents’ age nor sex was a significant predictor of the target adolescents’ materialism. The target adolescents’ materialism was, however, significantly positively statistically associated with fathers’, siblings’, peers’ materialism and marginally positively with mothers’ materialism. That said, when we used the more rigorous bootstrapping method with bias-corrected confidence estimates to test significance (cf. Davidson and Hinkley 1997; see Table 2), the results showed that siblings’, peers’, and fathers’ materialism remained statistically significant predictors of adolescents’ materialism, whereas mothers’ materialism did not. Also the results of VIF (VIF > 1) showed that tested interpersonal materialism role models were moderately correlated with each other (cf. Lavery et al. 2019).

In order to test hypothesis 1, that peers’ and siblings’ materialism might explain adolescents’ materialism more strongly than parents’ materialism, we carried out z test for the difference between two regression coefficients (cf. Paternoster et al., 1998). The results showed no significant differences between regression coefficients of mother’s /father’s materialism and sibling’s materialism (mother–sibling Z = 1.32, p = 0.19; father–sibling Z = 1.32, p = 0.19), and between regression coefficients of mother’s/father’s materialism and peer’s materialism (mother-peer Z = 0.42, p = 0.68; father-peer Z = 0.35, p = 0.72). Thus, all of the four interpersonal materialism role models are approximately equally strong predictors of the target adolescents’ materialism.

Adolescents’ Materialism, Interpersonal Role Models, Media exposure, and Threat

Next, we used structural equation modeling (SEM with Maximum Likelihood estimation) with AMOS (McFatter, 1979) to test our second hypothesis and examine how the three sets of environmental variables (i.e., the four interpersonal role models, media exposure (i.e., TV and the Internet), and family SES) relate to adolescents’ materialism. The model included three latent variables. The first latent variable, interpersonal materialism role models, was operationalized to reflect the materialistic modeling from all four interpersonal models (mother, father, sibling, and peer). Taking account of the obtained results presented above, the four materialism role models appear to be indicators of one underlying construct of interpersonal materialism role models. The second latent variable was operationalized to reflect media exposure from TV and the Internet; these are significantly positively statistically correlated (Table 1), thus suggesting that they reflect one underlying concept. The third latent variable was operationalized to reflect family SES from family income, mother’s education, and father’s education, which are highly correlated with each other (Table 1). As will be seen momentarily, these assumptions were supported in the conducted SEM model.

Because existing research shows that interpersonal materialism role models are sometimes related to media exposure (cf. Hawkins & Pingree, 1981; Steele & Brown, 1995), we allowed for correlations between interpersonal models and the other tested predictor variables in our SEM model. Further, because literature shows that living in an economically deprived environment (i.e., low family SES) can be associated with greater exposure of adolescents to media, and thereby materialistic messages (cf. Roberts & Foehr, 2008; Livingstone & Helsper, 2008), we also allowed for family SES and media exposure to be correlated in the SEM model.

The conducted SEM model obtained a good model fit: χ 2 (30) = 34.20, p = 0.27; RMSEA = 0.028 (LO90 = 0.00, HI90 = 0.066); PCLOSE = 0.80; GFI = 0.964; CFI = 0.990; TLI = 0.985; NFI = 0.927 (cf. Hu & Bentler, 1999), and Bollen-Stine Bootstrap p = 0.42 (cf. Bollen & Stine, 1992).

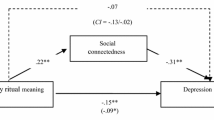

The path coefficiencies are shown in Fig. 1 and in Table 3. All path coefficients in the SEM model were statistically significant. The bootstrapping method with bias-corrected confidence estimates also showed significance for all tested path coefficients. For the social materialism role models, the results are largely in line with the hypotheses. Specifically, as predicted, both interpersonal materialism role models and media exposure were positively associated with the target adolescents’ materialism levels. However, in contrast to past studies and to the nonsignificant correlation reported in Table 1, family SES was significantly positively (rather than negatively) statistically associated with adolescents’ materialism. This result suggests the possibility of a suppressor effect, as will be discussed below.

Results of SEM testing three environmental correlates of adolescents’ materialism. Note. Ellipses represent latent variables. IRM, interpersonal role models, Family SES family socioeconomic status, ME media exposure, e errors. The values above rectangles show the squared multiple correlations. The numbers above the arrows in the figure are standarized coefficients. The Path coefficients are significant on the level p < 0.001 (except for the path ME -> Teen materialism, where p = 0.006). The correlations between latent variables are significant: Me <−> Family SES p < 0.001, IRM <-> Family SES p = 0.01; IRM <-> ME p = 0.01

Discussion

This paper had two primary aims. First, we examined the relative strength of relations between adolescents’ materialism and four interpersonal materialism role models: mothers, fathers, siblings, and peers. Second, we tested how adolescents’ materialism is simultaneously linked to three sets of environmental variables: interpersonal role models’ (i.e., the mother’s, father’s, sibling’s, and peer’s) materialism, exposure to media, and family SES (a type of threat/insecurity). Importantly, we obtained a reasonably large sample of adolescents who reported via multiple means on their own materialism, and we directly asked the adolescents’ mothers, fathers, siblings, and peers about their own levels of materialism (rather than relying on the adolescents’ second-hand reports).

The study yielded clear results regarding social influences on adolescents’ materialism. Specifically, both interpersonal materialism role models and media exposure were statistically significantly and positively associated with adolescents’ materialism levels. These findings confirm previous results indicating positive relationships between adolescents’ materialism and their fathers’ materialism (e.g., Chaplin & John, 2010; Goldberg et al., 2003; Wojtowicz, 2013) and peers’ materialism (e.g., Chaplin & John, 2010). Previous studies (e.g., Chaplin & John, 2010; Flouri, 1999; Goldberg et al., 2003; Kasser et al., 1995) showed significant positive correlations between mothers’ materialism and adolescents’ materialism. The current results suggest that the link between adolescents’ materialism and mothers’ materialism is not significant after controlling for other interpersonal models.

Past research findings regarding the relationship between fathers’ and adolescents’ materialism have been inconclusive (see Chaplin & John, 2010; Goldberg et al., 2003; Wojtowicz, 2013; Zawadzka & Dykalska-Bieck, 2013). The current results show that fathers’ materialism is statistically significantly related to adolescents’ materialism, even after controlling for other models. The fact that adolescents’ materialism is significantly related to fathers’ materialism might be explained by the specificity of parental influence in adolescence. Research on the relative importance of parents in child development shows that the father’s role increases during adolescence (Dekovic & Meeus, 1997; Trowell, 2002). The fathering role is often related to the performance of instrumental functions that include the material aspect of the family’s functioning, i.e., providing income and protection (Finley et al., 2008). What is more, the father’s acceptance of the teen during adolescence is an important predictor of the adolescent’s adaptation to the external environment (Barber et al., 2005; Forehand & Nousiainen, 1993). In this way, the father may become a significant model of the adolescent’s materialistic beliefs and values (cf. Clark et al., 2001).

The results of the study do not confirm the perspective that parents’ materialism may be somewhat less responsible for adolescents’ materialism than siblings’ and peers’ materialism; the interpersonal materialism role models were linked to adolescents’ materialism at approximately the same strength. Thus, these results are relevant to the ongoing discussion about the relative strength of the influence of parents vs. peers on adolescents, and support the perspective that while peers are of particular importance as role models in adolescence, parents continue to have a strong influence, perhaps because they are the first role models that shape goals and values of their children (cf. Boehnke et al., 2002). The obtained results confirm the conclusions from our previous experimental studies (Zawadzka et al., 2021) that the increase in materialistic aspirations of adolescents is significantly linked to the priming of materialistic goals itself regardless of the source of priming (parents, peers or media).

The current results also support past research showing that frequent exposure to media is positively associated with adolescents’ materialism (Kasser et al., 2004; Opree et al., 2014; Zawadzka et al., 2021). Importantly, the current results were obtained with data on two pieces of technology frequently used to deliver commercial messages (i.e., television and the Internet) and after controlling for other potential sources of materialism. The obtained results suggest that exposure to both new and traditional media may play an important role in the development of adolescents’ materialism.

Although results were clear and in line with hypotheses and past research for the interpersonal models and for media exposure, the findings were substantially less clear for the threat/insecurity variable of family SES. At the zero-order level, the socio–economic situation of the family was unrelated to adolescents’ materialism (Table 1), but when accounting for the social modeling variables, the direction of the relation between SES and adolescents’ materialism was, surprisingly, opposite that reported in past studies (Fig. 1). Specifically, we found a positive association between family socio–economic status and adolescents’ materialism. This finding may be interpreted in several ways. One possibility is that the observed positive association may be due to the economic and financial changes that took place in Central Europe in the 1990s, which contributed to an increase in the material well-being of these societies (cf. Górnik-Durose & Dziedzic, 2013; Zawadzka et al., 2018). Material prosperity, previously unattainable to many, may have become a symbol of success and social advancement. Hence, living in a family with a high SES might strengthen adolescents’ belief in the importance of possessing things and money in life (Dittmar et al., 2008). Another possible explanation for the positive relationship between Family SES and adolescent materialism is that the current sample was fairly highly educated, whereas the samples in previous studies that indicated a negative relation between family SES and adolescents’ materialism (cf. Cohen & Cohen, 1996; Kasser et al., 1995) intentionally oversampled adolescents from very difficult family circumstances, including poverty. Thus, family SES may be negatively linked to materialism only when adolescents come from families with very difficult SES conditions, as opposed to merely low SES. Such an interpretation is supported by research indicating that low family SES is positively linked to materialism only when a lack of resources is experienced (cf. Roux et al., 2014).

Yet another possible explanation for the unexpected significant positive relationship between SES and materialism is that it reflects a suppression effect (McFatter, 1979). No significant zero-order correlation was found between family SES (i.e., income, mother’s education, and father’s education) and adolescents’ materialism (Table 2), but the relationship became significant and positive when other variables were included in SEM analyses (Fig. 1 and Table 3). The fact that family SES was negatively correlated with siblings’ materialism and media exposure, both of which were positively associated with target adolescent’s materialism, could account for this suppression effect. Clearly, it is difficult to unequivocally interpret the nature of the associations between adolescents’ materialism and SES, and further research is required.

In sum, it seems clear from this study and from other studies that the relations between social materialism role models (i.e., interpersonal role models and media) and adolescents’ materialism are robust, but that the link between threat (i.e., family SES) and adolescents’ materialism is more complex and may depend on cultural and other familial factors.

Study Limitations

The current study has its limitations. The design of the study was correlational and cross-sectional. As such, while the findings provide reasonable grounds for concluding that adolescents’ materialism is positively linked to social materialism role models (i.e., materialistic parents, siblings, peers, and media), future research is needed to establish causality and to test whether the statistical relations change as the adolescents age. In the future, longitudinal studies could examine how associations between adolescents’ materialism and the variables studied here unfold over time.

Our measurement strategy also had its limitations. While we used multiple surveys (rather than a single one) to assess most of our constructs, we still relied on self-report questionnaires; other means of assessing materialism could be used in the future (e.g., collage methodology; Chaplin & John, 2007). Also, while we did obtain reports of mothers’, fathers’, siblings’ and peers’ materialism directly from the respondents (as opposed to from the target adolescent), we measured media exposure via the target adolescents’ own retrospective self-report. Though this approach has been commonly used in previous research (cf. Benmoyal-Bouzaglo & Moschis, 2010; Bybee et al., 1985; Churchill & Moschis, 1979; Górnik-Durose, 2001; Moschis & Churchill, 1978; Nairn et al., 2007) it measures declarations about past behavior rather than actual behavior, and thus may be an inaccurate assessment. In the future, it would be useful to refine this measurement by using in vivo diary measures over the course of a couple of weeks and/or the parents’ report of the adolescent’s media usage.

Additionally, our assessment of peers’ materialism depended upon the target adolescents indicating their favorite other peers from their same class; this may have artificially inflated the size of the correlation, as favorite others may, by definition, have particularly similar attitudes and values to target adolescents. Further research should check how adolescents’ materialism is related to a broader range of peers.

Similarly, if the surveyed adolescents had more than one sibling, they indicated the siblings to be assessed (67.3% of the target adolescents had one sibling and 32.7% of the target adolescents had two or more siblings). This could affect the obtained results as the target adolescents may have chosen their favorite siblings, with whom they may have shared the same attitudes and values. Moreover, previous research shows that materialistic aspirations of siblings are especially similar when siblings compete with each other (cf. Kretschmer & Pike, 2010). Therefore, further research is needed to check whether relations between siblings (e.g., favored relationship, competition) can moderate the relationship between adolescents’ materialism and their siblings’ materialism.

Previous studies on the influence of siblings on adolescents (albeit with variables other than materialism) showed that siblings’ gender and relative age are important moderating factors (Wang et al., 2019). Therefore, it would be advantageous for future studies to consider the siblings’ age difference (older vs. younger) and sex relative to the target adolescent and how these variables might affect relations between the target adolescents’ and siblings’ materialism. Notably, we explored this question utilizing the PROCESS macros for SPSS developed by Hayes (2013) to check moderation effects by the birth order of siblings on the relation between siblings’ materialism and the target adolescents’ materialism, and it was statistically nonsignificant (ΔR2 = 0.003, ΔF(1,187) = 0.61, p = n.s.).

Another limitation of our study concerns the age of our sample. Peers’ significance grows and their influence becomes stronger (cf. Schaffer, 1996) as adolescents age. Thus, further research should look into whether similar results occur in other age-groups, e.g., 10–13-year-olds and 16–18-year-olds.

A final limitation worthy of note is that the study was conducted in a single nation and specific culture. Poland is a more collectivistic country and somewhat poorer country (cf. Lowry et al., 2018) compared to Western European countries and the US, where most past research on materialism has been conducted. Also, Polish people cherish the family and strongly hold on to conservative values (tradition and religion; CBOS, 2010). Because the proposed model looked (in part) for correlates of adolescents’ materialism in the family (parents’ and siblings’ values) and in family SES, the culture that the analyzed sample comes from may play a role in the observed relation. Therefore, future research is needed to determine whether similar results would be obtained in other cultural contexts, such as highly collectivistic or highly individualistic countries and/or in countries with high vs. low household income (cf. Zawadzka et al., 2020).

Implications

Given that adolescents’ materialism is associated with lower personal well-being, academic achievement, prosocial behavior, and pro-environmental behavior, it is important to understand potential environmental influences so that appropriate interventions can be developed to decrease the likelihood that adolescents adopt a materialistic outlook on life (e.g., Kasser et al., 2014, Study 4; Zawadzka et al., 2017). The results of the current study suggest that such interventions need to address the ways in which both parents and same-age interpersonal models may be influencing adolescents’ materialism levels. At the same time that interventions focus on interpersonal role models, the current results suggest that media exposure will also need to be addressed, given that this variable is also independently associated with adolescent materialism.

Finally, while such interventions may be useful, the current findings also support calls for the development of policies to limit marketers’ access to children and adolescents through media. Such policies could include removing marketing from schools, developing taxes on marketing that support children’s education, and outright bans on marketing to children, as has occurred in some Nordic nations, the Canadian province of Quebec, and Brazil (Kasser & Linn, 2016).

Conclusion

Despite its limitations, the current study provides insights into the environmental correlates associated with the development of materialism in adolescents. The study clearly indicates that social materialism role models (parents, siblings, peers, and media) are associated with adolescents’ materialism. It also suggests that the relation between adolescents’ materialism and that of other adolescents (both siblings and peers) is not stronger than the relationship between adolescents’ materialism and that of their parents. The findings are less clear-cut regarding how socioeconomic conditions relate to adolescents’ materialism.

References

Achenreiner, G. (1997). Materialistic values and susceptibility to influence in children. Advances in Consumer Research, 24, 82–88.

Ahuvia, A. C., & Wong, N. Y. (2002). Personality and values based materialism: their relationship and origins. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 12, 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1207/15327660260382414.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Banerjee, R. A., & Dittmar, H. E. (2008). Individual differences in children’s materialism: The role of peer relations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 17–31.

Barber, B. K., Stolz, H. E., Olsen, J. A., Collins, W. A., & Burchinal, M. (2005). Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 70, 1–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.2005.00365.x.

Benmoyal-Bouzaglo, S., & Moschis, G. P. (2010). Effect of family structure and socialization on materialism: a life-course study in France. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 18, 53–69. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679180104.

Beutler, J. (2012). Connections to economic prosperity. Money aspirations from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 23, 17–32.

Boehnke, K., Ittel, A., & Baier, D. (2002). Value transmission and” zeitgeist”: An underresearched relationship. Sociale Wetenschappen, 45, 28–43.

Bollen, K., & Stine, R. (1992). Bootstrapping goodness-of-fit measures in structural equation models. Sociological Methods and Research, 21, 205–229.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Bottomley, P. A., Nairn, A., Kasser, T., Ferguson, Y. L., & Ormond, J. (2010). Measuring childhood materialism: refining and validating Schor’s consumer involvement scale. Psychology & Marketing, 27(7), 717–740. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20353.

Brechwald, W. A., & Prinstein, M. J. (2011). Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721X.

Brown, B. B. (2004). Adolescents’ relationships with peers. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (p. 363–394). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Bybee, C., Robinson, J. D., & Turow, J. (1985). The effects of television on children: What the experts believe. Communication Research Reports, 2, 149–155.

Chan, K. (2013). Development of materialistic values among children and adolescents. Young Consumers, 14, 244–257. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-01-2013-00339.

Chan, K., & Cai, X. (2009). Influence of television advertising on adolescents in China: an urban rural comparison. Young Consumers, 10, 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1108/17473610910964714.

Chan, K., & Prendergast, G. (2008). Social comparison, imitation of celebrity models and materialism among Chinese youth. International Journal of Advertising, 27, 799–826. https://doi.org/10.2501/S026504870808030X.

Chan, K., & Prendergast, G. (2007). Materialism and social comparison among adolescents. Social Behavior and Personality, 35, 213–228. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2007.35.2.213.

Chang, L., & Arkin, R. M. (2002). Materialism as an attempt to cope with uncertainty. Psychology and Marketing, 19, 389–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.10016.

Chaplin, L. N., & John, D. R. (2007). Growing up in a material world: Age differences in materialism in children and adolescents. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 480–493. https://doi.org/10.2501/S026504870808030X.

Chaplin, L. N., & John, D. R. (2010). Interpersonal influences on adolescent materialism: A new look at the role of parents and peers. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20, 176–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2010.02.002.

Chaplin, L. M., Hill, R. P., & John, R. D. (2014). Poverty and materialism: A look at impoverished versus affluent children. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 33, 78–92. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.13.050.

CBOS (2010). The Public Opinion Research Centre, July, 1–4.

Chia, S. C. (2010). How social influence mediates media effects on adolescents’ materialism. Communication Research, 37, 400–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650210362463.

Churchill, G. A., & Moschis, G. P. (1979). Television and interpersonal influences on adolescent consumer learning. Journal of Consumer Research, 6, 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1086/208745.

Clark, P. W., Martin, C., & Bush, A. J. (2001). The effects of role models influence on adolescents’ materialism and marketplace knowledge. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 9, 27–36.

Cohen, P., & Cohen, J. (1996). Life values and adolescent mental health. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cotte, J., & Wood, S. L. (2004). Families and innovative consumer behavior: A triadic analysis of sibling and parental influence. Journal of Consumer Research, 31, 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1086/383425.

Davidson, A. C., & Hinkley, D. V. (1997). Bootstrap methods and their applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Deng, L., & Chan, W. (2017). Testing the difference between reliability coefficients alpha and omega. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 77(2), 185–203.

Dekovic, M., & Meeus, W. (1997). Peer relations in adolescence: Effects of parenting and adolescents’ self-concept. Journal of Adolescence, 20, 163–176. 10.1006.jado.1996.0074.

Dittmar, H., Bond, R., Hurst, M., & Kasser, T. (2014). The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: a meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107, 879–924. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037409.

Dittmar, H., Halliwell, E., Banerjee, R., Gardarsdóttir, R., & Janković, J. (2008). Consumer culture, identity and well–being. The search for the ‘good life’ and the ‘body perfect’. Hove and New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Dittmar, H., & Pepper, L. (1994). To have is to be: Materialism and person perception in working-class and middle-class British adolescents. Journal of Economic Psychology, 15, 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4870(94)90002-7.

Erikson, E. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Finley, G. E., Mira, S. D., & Schwartz, S. J. (2008). Perceived paternal and maternal involvement: Factor structures, mean differences, and parental roles. Fathering, 6, 62–82. https://doi.org/10.3149/fth.0601.62.

Flouri, E. (2005). Fathering and child outcomes. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Flouri, E. (1999). An integrated model of consumer materialism: Can economic socialization and maternal values predict materialistic attitudes in adolescents? The Journal of Socio Economics, 28, 707–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-5357(99)00053-0.

Forehand, R., & Nousiainen, S. (1993). Maternal and paternal parenting: Critical dimensions in adolescent functioning. Journal of Family Psychology, 7, 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.7.2.213.

Goldberg, M. E., Gorn, G. J., Peracchio, L. A., & Bamossy, G. (2003). Understanding materialism among youth. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13, 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327663JCP1303_09.

Górnik-Durose, M. (2001). Mass-mediated influences on patterns of consumption in Polish youth. In W. Wosińska, R. B. Cialdini, D. W. Barrett & J. Reykowski (Eds.), The practice of social influence in multiple cultures (pp. 223–234). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Górnik-Durose, M. (2016). Polska adaptacja Skali Wartości Materialnych (MVS) – właściwości psychometryczne wersji pełnej i skróconej skali. [A Polish adaptation of the Material Values Scale – measurement and properties of the full and short forms]. Psychologia ekonomiczna, 9, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.15678/PJOEP.2016.09.01.

Górnik-Durose, M., & Dziedzic, K. (2013). Środowisko rodzinne a orientacja na cele materialistyczne osób o różnych doświadczeniach generacyjnych. [Specificity of the family versus materialistic value orientation in people with various generational experiences]. Psychologia Wychowawcza, 3, 22–37. https://doi.org/10.5604/00332860.1094501.

Hawkins, R. P., & Pingree, S. (1981). Uniform messages and habitual viewing: unnecessary assumptions in social reality effects. Human Communication Research, 7, 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1981.tb00576.x.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, Conditional Process Analysis. A regression based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Publication, Inc.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Inglehart, R. (1990). Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kamal, S., Chu, S., & Pedram, M. (2013). Materialism, attitudes, and social media usage and their impact on purchase intention for luxury fashion goods among American and Arab generations. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 13, 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/1522019.2013.768052.

Kasser, T. (2005). Frugality, generosity, and materialism in children and adolescents. In K. Moore & L. H. Lippman (Eds.), What do children need to flourish? Conceptualizing and measuring indicators of positive development (pp. 357–373). New York, NY: Springer Sci. Bus. Media.

Kasser, T., & Linn, S. (2016). Growing up under corporate capitalism: The problem of marketing to children, with suggestions for possible solutions. Social Issues and Policy Review, 10, 122–150.

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1993). A dark side of the American dream: correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 410–422.

Kasser, T., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Sheldon, K. M. (2004). Materialistic values: Their causes and consequences. In T. Kasser & A. D. Kanner (Eds.), Psychology and consumer culture: The struggle for a good life in a materialistic world (pp. 11–28). Washington: APA.

Kasser, T., Ryan, R. M., Zax, M., & Sameroff, A. J. (1995). The relations of maternal and social environments to late adolescents’ materialistic and prosocial values. Developmental Psychology, 31, 907–914. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.31.6.907.

Kasser, T., Rosenblum, K., Sameroff, A. J., Deci, E. L., Niemiec, C. P., Ryan, R. M., Arnadottir, O., Bond, R., Dittmar, H., Dungan, N., & Hawks, S. (2014). Changes in materialism, changes in psychological well-being: Evidence from three longitudinal studies and an intervention experiment. Motivation and Emotion, 38, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-013-9371-4.

Klint, K. A., & Weiss, M. R. (1986). Dropping in and dropping out: Participation motives of current and former youth gymnasts. Canadian Journal of Applied Sport Sciences, 11, 106–114.

Kohn, M. L., Slomczynski, K. M., & Schoenbach, C. (1986). Social stratification and the transmission of values in the family: A cross-national assessment. Sociological Forum, 1, 73–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01115074.

Kretschmer, T., & Pike, A. (2010). Associations between adolescent siblings’ relationship quality and similarity and differences in values. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 411–418. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020060.

Ku, L., Dittmar, H., & Banerjee, R. (2014). To have or to learn? The effects of materialism on British and Chinese children’s learning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106, 803–821. 10/1037/a0036038.

Ku, L. (2015). Development of materialism in adolescence: the longitudinal role of satisfaction among Chinese Youth. Social Indicators Research, 124, 231–247. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1996.0074.

La Ferle, C., & Chan, C. (2008). Determinants for materialism among adolescents in Singapore. Young Consumers, 9, 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1108/17473610810901633.

Lavery, M. R., Acharya, P., Sivo, S. A., & Xu, L. (2019). Number of predictors and multicollinearity: What are their effects on error and bias in regression? Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation, 48, 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610918.2017.137150.

Leckenby, J. D. (2005). The interaction of traditional and new media. In M. R. Stanfford & R. J. Faber (Eds.), Advertising, promotion, and new Media (pp. 3–29). New York, NY and London: M.E. Sharpe.

Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. J. (2008). Parental mediation and children’s Internet use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 52, 581–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838/50802437396.

Lowry, T., Chaplin, L., Nairn, A., Gentina, E., Bakir, A., Cauberghe, V., Hudders, L., Hua, L., Spotswood, F., & Zawadzka, A. M. (2018). Conducting international consumer research with children: Challenges and potential solutions. In M. Solomon & T. Lowry (Eds.), Conducting International Consumer Research with Children (pp. 346–360). New York, NY: Routledge.

Manolis, C., & Roberts, J. A. (2012). Subjective well-being among adolescent consumers: The effects of materialism, compulsive buying and time affluence. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 7, 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-011-9155-5.

McFatter, R. M. (1979). The use of Structural Equation Models in interpreting regression equations including suppressor and enhancer variables. Applied Psychological Measurement, 3, 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167900300113.

Moldes, O., & Ku, L. (2020). Materialistic cues make us miserable: A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence for the effects of materialism on individual and societal well-being. Psychology and Marketing, 37, 1396–1419. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21387.

Moschis, G. P., & Churchill, G. A. (1978). Consumer socialization: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 15, 599–609. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150629.

Moschis, G. P., & Moore, R. L. (1982). A longitudinal study of television advertising effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1086/208923.

Nairn, A., Ormrod, J., & Bottomley, P. (2007). Watching, wanting and wellbeing: Exploring the links. London: National Consumer Council.

Opree, S. J., Buijzen, M., Van Reijmersdal, E. A., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2014). Children’s advertising exposure, advertised product desire, and materialism: A longitudinal study. Communication Research, 41, 717–735. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650213479129.

Parsons, T., & Bales, R. F. (1956). Family Socialization and interaction process. New York, NY: Free University Press.

Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Mazerolle, P., & Piqvero, A. (1998). Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology, 36, 859–866.

Roberts, D. F., & Foehr, U. G. (2008). Trends in Media use. The Future of Children, 18, 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.0.0000.

Roberts, J. A., Manolis, C., & Tanner, J. (2008). Interpersonal influence and adolescent materialism and compulsive buying. Social Influence, 3, 114–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510802185687.

Roux, C., Goldsmith, K., Blair, S., & Kim, J. K. (2014). When does who have the last spend the most: understanding the relationship between resource scarcity, socioeconomic status and materialism. In J. Cotte & S. Wood (eds.), Advances in Consumer Research, 42 (pp. 215–219). Duhuth, MN: Association for Consumer Research.

Schaffer, H. R. (1996). Social development. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Schor, J. (2004). Born to buy: The commercialized child and the new consumer culture. New York, NY: Scribner.

Sheldon, K. M., & Kasser, T. (2008). Psychological threat and extrinsic goal striving. Motivation & Emotion, 32, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9081-5.

Sheldon, K. M., Sheldon, M. S., & Osbaldiston, R. (2000). Prosocial values and group assortation. Human Nature, 11, 387–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-000-1009-z.

Steele, J. R., & Brown, J. D. (1995). Adolescent room culture: Studying media in the context of everyday life. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24, 551–576.

Trowell, J. (2002). Setting the scene. In J. Trowell & A. Etchegoyen (Eds.), The importance of fathers: A psychoanalytic re-evaluation (pp. 3–19). East Sussex, UK: Brunner-Routledge.

Twenge, J. M., & Kasser, T. (2013). Generational changes in materialism and work centrality, 1976–2007: associations with temporal changes in societal insecurity and materialistic role-modeling. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 883–897. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213484586.

Wang, R., Liu, H., & Jiang, J. (2020). Does socioeconomic status matter? Materialism and self-esteem: longitudinal evidence from China. Current Psychology, First on line 14 March, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144_020-00695-3.

Wang, M. T., Degol, J. L., & Ammemiya, J. L. (2019). Older siblings as a academic socialization agents for younger siblings: development of pathways across adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 1218–1233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01005-2.

Williams, G. C., Cox, E. M., Hedberg, V., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Extrinsic life goals and health risk behaviors in adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 1756–1771.

Wojtowicz, E. (2013). Cele życiowe ojców i ich dzieci: perspektywa teorii autodeterminacji. [Father’s and their children’s life goals in the context of Self-Determination Theory]. Forum Oświatowe, 25, 73–85.

Zawadzka, A. M., & Dykalska-Bieck, D. (2013). Wartości rodziców i tendencje materialistyczne dzieci. [Parent’s values and children’s materialistic tendencies]. Chowanna, 40, 235–254.

Zawadzka, A. M., Duda, J., Rymkiewicz, R., & Kondratowicz-Nowak, B. (2015). Polska adaptacja siedmiowymiarowego modelu aspiracji życiowych Kassera i Ryana. [Seven-dimensional model of life aspirations by Kasser and Ryan: Analysis of validity and reliability of the instrument]. Psychologia społeczna, 10, 101–112. https://doi.org/10.7366/1896180020153207.

Zawadzka, A. M., Niesiobędzka, M., & Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M. (2018). Does our subjective well-being decrease when we value high materialistic aspirations or when we attain them? Social Psychology Bulletin, 13, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.5964/spb.v13i1.25504.

Zawadzka, A. M., Kasser, T. Borchet, J., Iwanowska M., & Lewandowska-Walter, A. (2021). The effect of materialistic social models on teenagers’ materialistic aspirations: Results from priming experiments. Current Psychology, 40, 5958–5971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00531-3.

Zawadzka, A. M., Nairn, A., Lowrey, T., Hudders, L., Rogers, A., Bakir, A., Cauberghe, V., Gentina, E., Li, H., & Spotswood, F. (2020). Can the Youth Materialism Scale be used across different countries and cultures? International Journal of Market Research, 63, 317–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/147078533209566794.

Zawadzka, A. M., Skwira, M., & Solecka, S. (2017). Równowaga w świecie materializmu i reklamy? Edukacja konsumencka i edukacja społeczna dzieci i młodzieży. [How to keep balance in the world of materialism and advertising? Consumer and social education of children and teenagers]. In A. M. Zawadzka & M. Niesiobędzka (Eds), Tajemnice reklamy. O tym jak reklama wpływa na dzieci i młodzież (pp. 117–127). Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Liberi libri.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Judyta Borchet, a PhD student, for her assistance and active involvement in organizing materials for the study, getting in touch with schools and help in doing surveys for the study. We would also like to thank Iwona van Burren and the following students: Natalia Grzywińska, Karolina Karpińska, Maria Kornacka, Adam Lewandowski, Dorota Maniszewska, Agnieszka Płotkowska, Joanna Szczepanik for their help in doing surveys for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.Z. conceived the study, participated in its design, coordinated data collection, performed statistical analysis, interpreted the results, and drafted the manuscript. T.K. conceived the study, participated in its design, was involved in the interpretation of the results, and drafted the manuscript critically. M.N. participated in study design and assisted in writing the introduction. A.L.W. assisted in the study design, assisted in writing the introduction and was involved in the interpretation of the results. M.G.D. assisted in writing the introduction and was involved in the interpretation of the results.All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant awarded to Anna Maria Zawadzka from National Science Centre, Poland, grant number: 2015/17/B/HS6/04187.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in the studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its further amendments or comparable ethical standards. We obtained approval from the research ethics committee at the Gdańsk University, application no 6/2014.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zawadzka, A.M., Kasser, T., Niesiobędzka, M. et al. Environmental Correlates of Adolescent’ Materialism: Interpersonal Role Models, Media Exposure, and Family Socio-economic Status. J Child Fam Stud 31, 1427–1440 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02180-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02180-2