Abstract

We aimed to investigate the relationship between homophobic bullying, parental psychological control and sensation seeking among adolescents and young adults and to examine the mediating role of sensation seeking. The participants included 394 adolescents and young adults aged 15 to 20 years attending the 3rd, 4th and 5th years of two public high schools in Italian cities. Participants completed the Homophobic Bullying Scale, the Dependency—oriented and Achievement—oriented Parental Psychological Control, and the Sensation—Seeking Scale. The results showed that parental psychological control predicted bullying toward gay and lesbian people. However, the two dimensions of sensation seeking (thrill and adventure seeking, and disinhibition) represented two mediators in the relationship between parental psychological control, both achievement and dependency—oriented, and homophobic bullying.

Highlights

-

Psychological parental control may play a key role in the genesis of homophobic bullying during adolescence and young adulthood.

-

Sensation seeking may encourage homophobic bullying in adolescence and young adulthood.

-

Sensation seeking may play a key role in the relationship between parental control and homophobic bullying.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Homophobic bullying is a complex phenomenon in constant growth, especially in heterosexist cultures, and often finds in schools a fertile ground in which to take root. Homophobic bullying has its roots in homophobia and attacks those who do not adhere to the society—imposed canons of masculinity and femininity. The episodes of this form of bullying can be verbal and physical. Homophobic insults essentially concern sexuality and physicality to the point of affecting the victim’s sphere of attitudes and desires (D’Urso and Pace 2019; D’Urso et al. 2018; Rivers 2011). The literature has highlighted how antisocial behaviors and, in particular, bullying can be the consequences of highly dysfunctional primary relationships that induce adolescents not to adequately face the socialization process (D’Urso and Pace 2019). The homophobic victimization is connected with internalization, such as dissatisfaction and the development of signs of depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation (Winsper et al. 2012; You and Bellmore 2012). Moreover, the literature underlined that even victims of homophobic bullying report levels of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicide attempts (Pace et al. 2020). In Italy, people belonging to sexual minorities are often victimized (D’Urso and Pace 2019). Furthermore, social homophobia negatively affects attitudes and beliefs towards LGBT people, because of a heterosexist culture (Petruccelli et al. 2015). The theory of gender roles and feminist theories underline how sometime cultures, especially the Western one, is oriented towards showing models that reinforce gender inequalities (Butler 2011). A heterosexist society based on gender stereotypes can consolidate homophobic acts (River 2011).

Many studies have investigated however how family characteristics may encourage bullying attitudes. For example, the absence of satisfactory parental relationships and a dysfunctional parent—child relationship style can be strong risk factors related to bullying (Labella and Masten 2018; Wahl and Metzner 2012). In this sense, the absence of affective parental responses can lead individuals to develop a sense of frustration which could translate into aggression and bullying acts. Diversity thus becomes the scapegoat of one’s own frustration (Rivers 2011; Smith 2016). Additionally, studies have suggested that excessive parental psychological control may induce in adolescents a state of frustration and a need for autonomy and independence that leads them to respond aggressively.

Parental psychological control refers to the parents’ tendency to exert pressure on their children often inducing them to behave in certain ways (Guzzo et al. 2014; Pace et al. 2018a; Soenens et al. 2010). Soenens et al. (2010) suggest the existence of two forms of parental psychological control: dependency psychological control, and achievement psychological control. The first one may define as the use of psychological control in the domain of parent–adolescent intimacy, where control is used as a means to keep children within close physical and emotional confines. The second one may explain as the use of psychological control in the domain of achievement, where psychological control is used as a way to make adolescents comply with excessive parental standards for performance. In this climate of control, adolescents’ efforts to achieve goals and not disappoint expectations can make them vulnerable and fragile (Mabbe et al. 2016; Soenens et al. 2010). Studies in the literature generally agree that the two forms of parental control, achievement—oriented and dependency—oriented, represent risk factors in adolescents’ social development because—by affecting the socio-emotional sphere—they can lead to maladaptive responses such as addictive behavior and peer aggression in school contexts (Cui et al. 2014; Mabbe et al. 2016; Pace et al. 2018a; Pace et al. 2019; Soenens et al. 2008; Soenens and Vansteenkiste 2010).

Minuchin (1984) has suggested how the redundancy of specific interactions between family members creates interactive and exchange patterns that lay the foundations for the establishment of relationships. Family stimuli, paraphrasing Olson (2000), are capable of conveying and/or coping with developmental tasks or stressful situations, changing the levels of both cohesion and internal flexibility of the family system itself. Parental psychological control can therefore invalidate the family system (i.e., its balance levels, creating emotional tensions connoted by entanglement) and lead the adolescent towards negative developmental outcomes. The literature has also underlined how, often in adolescence, the motivation for deviant behavior (e.g., peer aggression) comes from a voluntary search for risk (Wilson and Scarpa 2011; Zuckerman and Aluja 2015). Indeed, research and risk manifestation can sometimes take on a positive value, as they represent the means by which to demonstrate one’s abilities, value, and status. In this sense, Zuckerman (1979) described sensation seeking as a manifestation of a personality trait characterized by the desire to experience new, strong, and exciting sensations, a trait that can regulate behavior. Furthermore, sensation seeking—in particular, the search for strong stimuli and sensations—can be one of the characteristics of aggressive adolescents and young adults (Zuckerman and Aluja 2015). In this sense, the continual search for strong feelings would guide behaviors in maladaptive terms so that it can be useful to satisfy a need. Furthermore, a recent study pointed out that adolescents reporting high levels of sensation seeking have been found to be more prone to commit acts of bullying (Antoniadou et al. 2016).

To explain how sensation seeking can derive from dysfunctional parenting experiences and lead to homophobic bullying, it is necessary to integrate models that include the importance of parenting relationships and the individual’s personal characteristics as being in relation to his or her environment. In this sense, first of all, the theory of Bandura (1978) may integrate the role of sensation seeking and the variables regarding the parent—child relationship to better explain homophobic bullying in adolescence (Swearer et al. 2014).

Stern’s (1985, 1989) theoretical model is useful in explaining how parental dysfunctions can induce in adolescents and young adults a state of internal frustration that pushes them to seek new stimuli and adopt aggressive behaviors. Stern describes the intimate development of the self as the result of the combination of interpersonal exchanges with parents. These highly emotional exchanges serve to regulate the individual’s expectations and subsequent behavior. Furthermore, parental relationships and, especially, the quality of these relationships would be linked to the emotional state and, as a consequence, modulate the social—cognitive structure of individual experiences. Therefore, if parental relationships are frustrating, they can produce maladaptive responses that lead the adolescent along trajectories of development that are not suited to developmental tasks. In this sense, parental bonds that foster autonomy and self—expression may play an adaptive and regulative function in the adolescent’s socio—emotional structure (Pace et al. 2016; Pace and Zappulla 2010).

Since parental psychological control and sensation seeking are not particularly well—studied constructs in relation to homophobic bullying, the general purpose of this study was to explore a model aimed at explaining homophobic bullying starting from parental psychological control and from the trait of sensation seeking. In line with the literature (Bandura 1978; Swearer et al. 2014), behavioral outcomes—in this case dysfunctional—may be the responses of contextual stimuli (parental control) and individual stimuli (sensation seeking) that influence each other. The current study aimed to explore within a sample of adolescents and young adults how parental control is related to the genesis of homophobic bullying and, subsequently, the role of sensation seeking in that relationship. Therefore, in line with the definitions of the constructs studied, we hypothesized that parental psychological control, which directly influences sensation seeking, can lead to a maladaptive response that results in homophobic behaviors (e.g., Soenens et al. 2010; Pace et al. 2018a).

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were 394 adolescents and young adults, (164 boys—41.6%—and 230 girls—58.4 %) aged from 15 to 20 years (M = 16.55; SD = 0.85), attending the third, fourth, and fifth classes of two public high schools situated in two big Italian cities. Only four participants were 18—20 years old because they were repeating the school year after failing. All the participants were Caucasian and, based on demographic information, were mostly of middle class backgrounds. The majority (90%) of the participants’ parents had completed high school or had a college degree. Most of the participants (84%) came from intact two—parent families (Table 1). We obtained written informed consent for all participants by sending letters to their parents to inform them of the study. No parents objected to their child’s involvement. We also obtained assent from all the adolescents and young adults involved in the study. Adolescents and young adults were asked in advance if they were aware of the phenomenon. Any doubts about the phenomenon were clarified before administration. Therefore, everyone was aware of what homophobic bullying represented.

Procedure

We collected data between 2017 and 2018. Participants completed self—report measures on homophobic bullying, parental psychological control, and sensation seeking during class hours, with the supervision of the researchers. The research was approved by the ethics committee of Kore University of Enna. Therefore, all procedures which involved human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Measures

Homophobic bullying

We administered the Homophobic Bullying Scale (Prati 2012) to assess homophobic bullying behaviors by pupils, through three perspectives: witness (e.g., “Think about a student who is perceived to be lesbian. Because of this, during the past 30 days, how often did you hear insulting remarks about her”), bully (e.g., “Think about a student who is perceived to be lesbian. Because of this, during the past 30 days, how often did you isolate or marginalize her”) and victim (in this section we requested participants to consider a series of events, such as being marginalized or teased, and then we asked them “During the past 30 days, how often did this happen because you are perceived to be gay or lesbian?”). Participants were also asked to report if they observed or were involved in different homophobic behaviors (isolation/exclusion, a spread of lies, homophobic skirmishes, theft or damage of property, physical assault, sexual/electronic harassment) in their schools, in the last 30 days. Response choices were on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (more than once a week). In the present study, we used the bully perspective scale: the person’s account of how often they engaged in homophobic bullying toward gay (α = 0.81) and lesbian students (α = 0.87).

Parental psychological control

We administered the Italian version (Guzzo et al. 2014) of the Dependency—oriented and Achievement—oriented Parental Psychological Control Scale (DAPCS, Soenens et al. 2010) to assess participants perceived parental psychological control. The scale consisted of 16 items regarding dependency—oriented psychological control (e.g. “My parents is only friendly with me if I rely on him instead of on my friends”; α = 0.84), and achievement—oriented psychological control (e.g. “My parents make me feel guilty if my performance is inferior”; α = 0.79), which participants were asked to answer on a five—point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Sensation seeking

We administered the Italian version (Manna et al. 2013) of the Sensation Seeking Scale (SSS, Zuckerman et al. 1964) to evaluate personality characteristics related to sensation seeking, that is the search for different, new, intense and complex situations and experiences that predispose individuals to adopt behaviors that lead them to take risks for their own health and to commit antisocial actions. Specifically, the scale gives information on two dimensions: Thrill and Adventure Seeking, referring to the desire for outdoor activities involving unusual sensations and risks (e.g., “I would often like to be a mountain climber”; α = 0.78), and Disinhibition, referring to the preference of out of control actions (e.g., “I like to have new and exciting experiences and feelings even if they are dangerous, unconventional or illegal”; α = 0.82). The scale consists of 12 pairs of items among which the participants were asked to choose the one that best described their preferences or sensations.

Analysis Plan

First, we conducted the Anova (Univariate Analysis of Variance) to check for any gender difference. Therefore, we conducted the analysis in two phases with MPlus 8. First, we used structural equation modeling (SEM; Hopwood 2007) to assess the relationship between the two forms of psychological parental control (dependency—oriented and achievement—oriented parental psychological control) and homophobic bullying toward lesbian and gay people. Subsequently, we conducted a second SEM to assess the role of the two dimensions of sensation seeking (thrill and adventure seeking, and disinhibition) in the relationship between the two forms of psychological parental control and homophobic bullying toward gay and lesbian people.

Results

Since no significant gender differences emerged from ANOVA, we conducted the structural equation models on all participants. The first structural equation model demonstrated that the association among the two dimensions of parental psychological control and homophobic bullying toward gay and lesbian had a good fit to the data (CFI = 1.00; RMSEA < 0.0001; χ2(14) = 217.36; p < 0.0001). Specifically, achievement psychological parental control was positively associated with homophobic bullying toward lesbian people (β = 0.10; p < 0.05) and toward gay (β = 0.21; p < 0.001), as well as dependency psychological parental control was positively associated with homophobic bullying towards lesbian people (β = 0.48; p < 0.0001) and toward gay (β = 0.31; p < 0.001). This model is shown in Fig. 1.

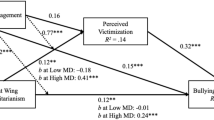

The second structural equation model demonstrated how the two dimensions of sensation seeking (thrill and adventure seeking, and disinhibition) mediated the relationship between achievement and dependency psychological parental control on homophobic bullying toward gay and lesbian people (CFI = 1.00; RMSEA < 0.0001; χ2(14) = 417.816; p < 0.0001). Specifically, thrill and adventure seeking was associated with homophobic bullying towards lesbian (β = 0.15; p < 0.001) and towards gay people (β = 0.09; p < 0.05), as well as disinhibition was related to homophobic bullying towards lesbian (β = 0.22; p < 0.0001) and towards gay people (β = 0.11; p < 0.001). Achievement parental psychological control was associated with thrill and adventure seeking (β = 0.22; p < 0.0001) and to disinhibition (β = 0.19; p < 0.001), as well as dependency parental psychological control was associated with thrill and adventure seeking (β = 0.40; p < 0.0001) and disinhibition (β = 0.31; p < 0.0001). The association between achievement parental psychological control and homophobic bullying towards gay people, through the intervention of the two dimensions of sensation seeking, remained significant but decreased (β = 0.20; p < 0.0001), suggesting a partial mediation. Conversely, instead, the association between achievement parental psychological control and homophobic bullying towards lesbian, through the intervention of the two dimensions of sensation seeking, was not significant, suggesting a total mediation. The relationship between dependency psychological parental control and homophobic bullying towards gays, through the intervention of the two dimensions of sensation seeking, remained significant but decreased (β = 0.19; p < 0.001), suggesting a partial mediation. Finally, the association between dependency psychological parental control and homophobic bullying towards lesbian people, through the intervention of the two dimensions of sensation seeking, continued to be significant, even if decreased (β = 0.39; p < 0.0001), suggesting a partial mediation. The whole model is shown in Fig. 2.

Discussion

The present study intended to examine the mediating role of sensation seeking in the relationship between homophobic bullying and parental psychological control in adolescence. The analysis underlined how dependency—and achievement—oriented parenting styles were linked to homophobic manifestations toward gays and lesbians. In line with our theoretical framework (Stern 1989; Swearer et al. 2014) and with the literature (Mabbe et al. 2016), the frustration of the need for autonomy, as well as the development of one’s independence, may be considered risk factors involved in behaving with homophobic acts. In other words, the parental effort toward dependence and toward achievement does not seem functional because it can often create strong feelings of frustration, as well as may lead to maladaptive socio—emotional development, which can then result in bullying people who the social fabric labels as different. Gay and lesbian persons then become the scapegoat on which to “vent” and project the internal frustrations derived from denying a need that is connected to the task of development, such as to develop an integral, autonomous, and independent self. Additionally, these findings highlight how dysfunctional relationships can implement unclear boundaries between family members, which entangle their children in poorly adapted parenting relationships (Olson 2000). Consequently, this frustrating family plots could be considered a risk factor towards homophobic bullying behavior.

Subsequently, the data suggested that the two forms of parental psychological control may also be risk factors related to the two dimensions of sensation seeking. In this sense, the frustration of needs may translate into adolescence with a search for strong feelings, as well as with the adoption of uninhibited and high—risk behavior (Pace et al. 2018b; Soenens et al. 2010). Therefore, excessive parental psychological control can produce responses to dysfunctional behaviors. In response to excessive parental pressures, the adolescent can find the satisfaction of his or her need for autonomy and independence in the risk and adoption of uninhibited behavior.

The mediation model, however, suggested that the two components of sensation seeking mediated the relationship between parental psychological control and bullying toward gay and lesbian people. Therefore, in line with the theoretical model (Bandura 1978) and in line with the literature (Zuckerman and Aluja 2015), an aggressive response to diversity can come from parental psychological control and sensation seeking (individual trait). In particular, in the case of the relationship between achievement—oriented parental psychological control and bullying toward lesbians, sensation seeking acted as a total mediator. So, in this sense, the frustration resulting from achievement—oriented parental control may lead the adolescent to pursue strong feelings and take on uninhibited behaviors that find the maximum maladaptive expression (bullying) when he or she comes into contact with diversity. These results also suggested that sensation seeking not only implements aggressive actions (Antoniadou et al. 2016), but is also connected to homophobic bullying. In other words, the predestined victim could be scapegoat on which to address the frustrations resulting from maladaptive needs for the search for autonomy and independence. Furthermore, in line with gender and feminist studies (Butler 2011), homophobic attitudes can be a negative response because adolescents have incorporated negative socio-cultural patterns that are based on inequalities. Thus, targeting a homosexual or presumed homosexual person can reinforce one’s distorted belief. In this sense, the act of bullying in adolescents normalizes because they will feel supported by the dominant society which is fundamentally heterosexist.

The adolescent’s search for risky situations and adoption of uninhibited behaviors, which are framed as negative responses to parental psychological control, often constitute the way in which adolescents and young adults seek and evaluate themselves and the ways in which they evaluate their skills and limits. In some cases, high—risk actions are undertaken only to escape boredom and frustration; consequently, these behaviors are detrimental to development, which can lead to aggressive outcomes. Zuckerman’s theory suggests that adolescents with high levels of sensation seeking need various, new and complex impressions, combined with the willingness to expose themselves, precisely for the sake of this research, physical and social risks. However, this construct could be understood as the result of frustrated needs and negated needs derived from dysfunctional parental relationships, i.e., dotted with high levels of parental psychological control. This dysfunctional mix can also implement the need to experience this search for sensations in bullying behaviors towards those who are considered different. In this sense, the homophobic attitude is not a “natural” expression of maladaptive responses to psychological parental control and of sensation seeking in adolescence, but it may represent one of the possible dysfunctional responses derived from a frustrated need and the need to turn this need into negative action (Rivers 2011).

Limitations and Future Research

The present work, although it may help to extend the literature for its analysis of little—studied constructs in relation to homophobic bullying, has some limitations. Generally speaking, the study design does not enable us to capture the complexity of these phenomena. More specifically, the present study is cross—sectional, so future studies should investigate the variables presented in the model in a longitudinal perspective. The use of a convenience sample, characterized by a homogeneity, is another limitation because it may distort results’ generalizability. Additionally, the use of a self—report questionnaires can lead the adolescent to respond in a socially desirable way. Future studies could investigate the same variables using implicative tools or alternative techniques (e.g., observation and interviews). Another limitation of the current study is not to consider all the points of view of the phenomenon (author, victim, and witness). Future studies could test this model on all the actors of homophobic bullying. The last limitation also concerns not considering the traditional form of bullying. Indeed, future studies could be of a comparative nature. In the light of our finding, future studies could investigate whether other forms of bonding and/or parental dysfunction can be connected, also in a longitudinal perspective, to homophobic bullying.

Conclusion

The study suggests that clinical practice with adolescents should start from a careful reflection on parenting relationships as protective factors for the development of adaptive outcomes. The ability to clearly define the boundaries of parental roles is a prerequisite for well—being, autonomy, and the ability to manage emotions. Finally, this contribution can be of considerable help in structuring prevention strategies for homophobic bullying because it highlights what characteristics and therefore which psychosocial aspects of a deficit can be considered risk factors. In this sense, prevention strategies should address not only adolescents and young adults but also parents who act as privileged actors in the development and fulfillment of their child’s developmental tasks. This means that if the parent–child relationship is functional, there is little to no risk of maladaptive outcomes. Indeed, parents who believe they are acting in the good of their child by pushing him or her to be the best or to be dependent on the parents are unaware of the fact that they are neglecting the needs and expectations of the child, who then must channel and experience these elsewhere.

References

Antoniadou, N., Kokkinos, C. M., & Markos, A. (2016). Possible common correlates between bullying and cyber—bullying among adolescents. Psicología Educativa, 22, 27–38.

Bandura, A. (1978). The self-system in reciprocal determinism. American Psychologist, 33, 344–358.

Butler, J. (2011). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cui, L., Morris, A. S., Criss, M. M., Houltberg, B. J., & Silk, J. S. (2014). Parental psychological control and adolescent adjustment: the role of adolescent emotion regulation. Parenting, 14, 47–67.

D’Urso, G., & Pace, U. (2019). Homophobic bullying among adolescents: the role of insecure-dismissing attachment style and peer support. Journal of LGBT Youth, 16, 173–191.

D’Urso, G., Petruccelli, I., & Pace, U. (2018). The interplay between trust among peers and interpersonal characteristics in homophobic bullying among Italian adolescents. Sexuality & Culture, 22, 1310–1320.

Guzzo, G., Lo Cascio, V., Pace, U., & Zappulla, C. (2014). Psychometric properties and convergent validity of the Dependency-oriented and Achievement-oriented Psychological Control Scale (DAPCS) with Italian adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23, 1258–1267.

Hopwood, C. J. (2007). Moderation and mediation in structural equation modeling: applications for early intervention research. Journal of Early Intervention, 29, 262–272.

Labella, M. H., & Masten, A. S. (2018). Family influences on the development of aggression and violence. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, 11–16.

Mabbe, E., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Van Leeuwen, K. (2016). Do personality traits moderate relations between psychologically controlling parenting and problem behavior in adolescents? Journal of Personality, 84, 381–392.

Manna, G., Faraci, P., & Como, M. (2013). Factorial structure and psychometric properties of the Sensation Seeking Scale-Form V (SSS-V) in a sample of Italian adolescents. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 9, 276–288.

Minuchin, S. (1984). Family kaleidoscope. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Olson, D. H. (2000). Circumplex model of marital and family systems. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(2), 144–167.

Pace, U., D’Urso, G., & Zappulla, C. (2018a). Adolescent effortful control as moderator of father’s psychological control in externalizing problems: a longitudinal study. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 152, 162–175.

Pace, U., D’Urso, G., & Zappulla, C. (2018b). Negative eating attitudes and behaviors among adolescents: the role of parental control and perceived peer support. Appetite, 121, 77–82.

Pace, U., & Zappulla, C. (2010). Relations between suicidal ideation, depression, and emotional autonomy from parents in adolescence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 747–756.

Pace, U., D’Urso, G., & Zappulla, C. (2019). Internalizing problems as a mediator in the relationship between lack of control and internet abuse in adolescence: a three-wave longitudinal study. Computer in Human Behavior, 92, 47–54.

Pace, U., D’Urso, G., Passanisi, A., Mangialavori, S., Cacioppo, M., & Zappulla, C. (2020). Muscle dysmorphia in adolescence: The role of parental psychological control on a potential behavioral addiction. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 455–461.

Pace, U., Zappulla, C., & Di Maggio, R. (2016). The mediating role of perceived peer support in the relation between quality of attachment and internalizing problems in adolescence: a longitudinal perspective. Attachment & Human Development, 18, 508–524.

Petruccelli, I., Baiocco, R., Ioverno, S., Pistella, J., & D’Urso, G. (2015). Famiglie possibili: uno studio sugli atteggiamenti verso la genitorialità di persone gay e lesbiche. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia, 42(4), 805–828.

Prati, G. (2012). Development and psychometric properties of the homophobic bullying scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 72, 649–664.

Rivers, I. (2011). Homophobic bullying: Research and theoretical perspectives. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Smith, P. K. (2016). Research on bullying in schools in European countries. In P. K. Smith, K. Kwak & Y. Toda (Eds), School bullying in different cultures: Eastern and Western perspectives (pp. 1–27). UK: Cambridge University Press.

Soenens, B., Luyckx, K., Vansteenkiste, M., Luyten, P., Duriez, B., & Goossens, L. (2008). Maladaptive perfectionism as an intervening variable between psychological control and adolescent depressive symptoms: a three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 465–474.

Soenens, B., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2010). A theoretical upgrade of the concept of parental psychological control: Proposing new insights on the basis of self-determination theory. Developmental Review, 30, 74–99.

Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Luyten, P. (2010). Toward a domain-specific approach to the study of parental psychological control: distinguishing between dependency-oriented and achievement-oriented psychological control. Journal of Personality, 78, 217–256.

Stern, D. N. (1985). The interpersonal world of the infant. New York, NY: Basic.

Stern, D. N. (1989). The representations of relational patterns: Developmental considerations. In A. J. Sameroff & R. N. Emde (Eds), Relationship disturbances in early childhood: A developmental approach (pp. 52–69). New York, NY: Basic.

Swearer, S. M., Wang, C., Berry, B., & Myers, Z. R. (2014). Reducing bullying: application of social cognitive theory. Theory into Practice, 53, 271–277.

Wahl, K., & Metzner, C. (2012). Parental influences on the prevalence and development of child aggressiveness. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21, 344–355.

Wilson, L. C., & Scarpa, A. (2011). The link between sensation seeking and aggression: a meta‐analytic review. Aggressive Behavior, 37, 81–90.

Winsper, C., Zanarini, M., & Wolke, D. (2012). Prospective study of family adversity and maladaptive parenting in childhood and borderline personality disorder symptoms in a non-clinical population at 11 years. Psychological Medicine, 42, 2405–2420.

Zuckerman, M. (1979). Attribution of success and failure revisited, or: the motivational bias is alive and well in attribution theory. Journal of Personality, 47, 245–287.

Zuckerman, M., & Aluja, A. (2015). Measures of sensation seeking. In G. J. Boyle, D. H. Saklofske, & G. Matthews (Eds), Measures of personality and social psychological constructs (p. 352–380). Elsevier Academic Press.

You, J., & Bellmore, A. (2012). Relational peer victimization and psychosocial adjustment: The mediating role of best friendship qualities. Personal Relationships, 19, 340–353.

Zuckerman, M., Kolin, E. A., Price, L., & Zoob, I. (1964). Development of a sensation-seeking scale. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 28, 477–482.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Palermo within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

U.P., G.D.U. and C.Z. designed and executed the study, assisted with the data analyses, wrote the paper, and edited the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The research was approved by the ethics committee of Kore University of Enna.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pace, U., D’Urso, G. & Zappulla, C. Psychological Predictors of Homophobic Bullying Among Adolescents and Young Adults: The Role of Parental Psychological Control and Sensation Seeking. J Child Fam Stud 30, 603–610 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01874-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01874-3