Abstract

Objectives

Evidence of the acceptability and potential efficacy of mindfulness strategies with at-risk youth is mounting. Yet only a few studies have assessed these strategies among youth experiencing homelessness (YEH).

Methods

We conducted a mixed methods feasibility study of an adapted mindfulness-based intervention (MBI) with sheltered YEH. The MBI consisted of five 1.5-h sessions delivered at a youth homeless shelter over 2.5 weeks. A one-group pre/post-test design was utilized to collect quantitative assessments of real-time cognitions followed by qualitative inquiry to assess participants’ experiences and perceptions of the intervention.

Results

Participants (N = 39) were between 18–21 years old with the majority identifying as male (56.4%), heterosexual (74.4%), Black (51.3%) and Hispanic (15.4%). Attendance was challenging for participants (2.2 sessions attended on average) who had varying work and school obligations. However, pre–post session survey data completeness was excellent (92% completion rate). Participants completed self-report surveys prior to and after each session that measured affect. Significant improvement in pre–post session outcomes were found for frustration, restlessness, stress, depression, boredom, and mindlessness. Participants reported high levels of acceptability of the curriculum content and delivery format. However, several substantial adaptations that youth identified may improve feasibility and acceptability among YEH. The results are limited by the small sample size and the use of a curriculum not developed with or for YEH.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the potential feasibility of using MBIs among YEH although adaptations to existing curricula are necessary to increase relevance, acceptability of, and access to MBIs among YEH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

On any given night in the U.S., 1.7–3.5 million youth under age 25 are homeless (Bassuk et al. 2011, 2014; Bassuk 2010; Morton et al. 2017). Youth experiencing homelessness (YEH), a hard-to-reach, underserved population, suffer a disparate burden of adverse health outcomes including death, suicide, drug overdose, substance abuse, pregnancy, HIV, and mental illness. The tumultuous experiences of daily life on the streets are difficult for young people who become homeless. While surviving the dangers of the streets and meeting one’s basic needs for food and shelter, youth face enormous difficulties in maintaining their health and well-being. YEH are transient and may live in emergency shelters or on the streets (e.g., parks and tent cities); squat in abandoned or vacant buildings or apartments; temporarily stay with friends, family, or acquaintances (often called “couch surfing”); or rent hotel/motel rooms. YEH go to great lengths to stay hidden from the dangers of victimization (Santa Maria et al. 2015). Most youth who are chronically homeless move frequently between these housing situations (Gaetz 2009). When youth become homeless, they bring to the streets a range of emotional and psychological challenges that negatively impact their well-being, decision making, emotion regulation, and coping skills. YEH often have lengthy histories of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) (Felitti et al. 1998) and multiple traumas stemming from difficult family situations, poverty, and physical, sexual, and/or emotional abuse that significantly contribute to their risk for experiencing homelessness as an adolescent or young adult (Bender et al. 2015). Studies have found high ACEs among YEH, with about 80% of young adults experiencing homelessness reporting two or more ACEs and other studies finding an average of 4.6 ACEs (Bender et al. 2015; Narendorf et al. 2018). Moreover, YEH often have parents with addiction or psychiatric disorders and also participate in criminal activities that compound the trauma and instability they may have experienced during childhood (Andres-Lemay et al. 2005; Stephen Gaetz 2004).

A growing body of evidence supports the central role that stress plays in engaging in behaviors including substance use and risky sexual activity. In a study among young adults (n = 362), experiencing betrayal trauma prior to age 18 was associated with problematic substance use subsequent to PTSD and difficulty discerning or heeding risk and self-destructiveness (β = 0.07, p < 0.001; β = 0.12, p < 0.001) (Delker and Freyd 2014). PTSD has also been associated with engaging in risky behavior while under the influence of substances (Kingston and Raghavan 2009). Stress at age 19 was found to predict the development of a substance use disorder by age 22 among a sample of young males (Cornelius et al. 2014). Studies have found that pregnancy rates and repeat pregnancies were higher among women with moderate to high levels of stress than in women with low levels (Hall et al. 2015). As well, females aged 18–20 years with moderate/severe stress had over twice the odds of contraception non-use and misuse as those without stress (Hall et al. 2013a). Stress also predicted inconsistent use of oral contraceptives, condoms, and withdrawal (Hall et al. 2013b). In Black men, stress from discrimination has been suggested as a pathway to increased sexual risk behaviors (Bowleg et al. 2014). Moderate to severe stress has been linked to increased weekly sexual intercourse frequency (Hall et al. 2014b). The pregnancy rate among depressed women reporting stress was 1.6 times higher than the rate among women not reporting stress (Hall et al. 2014a); the co-occurrence of stress and depression was the strongest predictor of pregnancy, and stress was the strongest predictor of repeat pregnancy. In Black adolescent females, higher interpersonal stress was associated with lower use, inconsistent use, and non-use of a condom during the most recent sexual encounter (Hulland et al. 2014). High stress has also been associated with reduced condom and contraceptive use and increased frequency of sex. Among young men who have sex with men, having increased stress on the day of sex predicted inconsistent condom use (Parsons et al. 2012; Wong et al. 2010). The most effective prevention interventions may be those that address stress and risk behaviors simultaneously (Carmona et al. 2014). Chronic stress related to homelessness impedes the adoption of sexual risk reduction behaviors (Aidala et al. 2005).

YEH, an underserved, highly vulnerable population, suffer a disparate burden of adverse health outcomes with worse physical and mental health than the general adolescent population (Kulik et al. 2011). YEH have higher rates of psychiatric disorders and are more likely to attempt suicide than their stably housed peers (Edidin et al. 2012; Merscham et al. 2009). Estimates of homeless youth who have a psychiatric diagnosis based upon diagnostic criteria range from 66 to 87% (Cauce et al. 2000). Additionally, 45% of YEH reported attempting suicide (Cauce et al. 2000). The mortality rate for YEH is 10 times higher than that among the general adolescent population, with suicide and drug overdose as the leading causes of death (Roy et al. 2004). Contributing factors to youth homelessness are psychiatric disorders (Edidin et al. 2012), criminality (Martijn and Sharpe 2006), parental and personal substance use (Mallett et al. 2005), domestic violence (Grant et al. 2007), physical or sexual abuse (Mayock et al. 2011), a history of foster care (Zlotnick 2009), and stressful and chaotic family environments (Mallett et al. 2005). Experiencing such adversity prior to age 16 can compromise stress responses and lead to behavioral impulsivity (Lovallo 2013), which is associated with higher sexual risk behaviors and substance use (Robbins and Bryan 2004).

The practice of mindfulness taught through mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) fosters present-moment, non-judgmental attention, which enhances self-observation and self-regulation (Goyal et al. 2014; Sibinga et al. 2011). The increased attention developed through MBI results in greater awareness of cognitions and emotions and leads to emotional reappraisal, less reactivity, greater contemplation of behaviors, and improved interpersonal dynamics and relationships (Shapiro et al. 2006; Siegel et al. 2009). Growing evidence demonstrates the efficacy of mindfulness interventions across various populations including those with traumatic stress and substance use (Garland et al. 2016) to decrease the frequency of risk behaviors (e.g., condomless sex) (Dermen and Thomas 2011) and to improve affect and executive functioning (Davydov et al. 2005; Hoppmann and Klumb 2006; Sibinga et al. 2013; Sibinga et al. 2016; Teper et al. 2013; Webb et al. 2018). For example, a stress reduction intervention in HIV-positive adult men who have sex with men reported post-intervention decreases in unprotected anal sex that were sustained over time (Williams et al. 2013). Youth who received a mindfulness curriculum reported lower stress and had reduced salivary cortisol than controls (Kuyken et al. 2013; Sibinga et al. 2013). One intervention, .b (pronounced “dot-be” and stands for stop and be), which is being disseminated across the U.S. (https://mindfulnessinschools.org/map/dot-b-teachers/), found high levels of acceptability among a school-based sample of 522 youth aged 12–16 years who reported lower stress (p = 0.05), with the amount of practice being associated with less stress (p = 0.03) (Kuyken et al. 2013). Several studies have found that mindfulness reduces symptoms of stress (Fjorback et al. 2011) and improves self-regulated behaviors (Brown and Ryan 2003), executive function (Flook et al. 2010; Jha et al. 2010; Teper et al. 2013), and resilience toward stress (Zenner et al. 2014).

While the effects of mindfulness approaches on stress and psychological symptoms have been well documented across populations, fewer studies have been conducted in youth and even fewer in YEH (Goyal et al. 2014; Grossman et al. 2004; Kabat-Zinn 1982). Nevertheless, evidence of the effectiveness of mindfulness approaches in adolescents is mounting, showing increased mindful attention and awareness and decreased reactivity in school-aged youth (Kuyken et al. 2013); improved depression, anxiety, coping, stress, emotion arousal, and reduced post-trauma stress symptoms in urban middle school youth (Sibinga et al. 2013); and reduced stress and anxiety in adolescent psychiatric patients (Biegel et al. 2009). A systematic review of stress reduction interventions in adolescents revealed improved cognitive skills (Rew et al. 2014). Reviews of youth-based mindfulness interventions (Burke 2010) and meditation practices (Black et al. 2009) suggest that these interventions may lead to improvements in depression and anxiety (Zoogman et al. 2015).

Although few studies have examined the effects of mindfulness interventions with YEH, research has found improved observational skills and suggests the need for further adaptations to meet the unique needs of this population (Bender et al. 2015). Studies have suggested that MBIs have high levels of acceptability in urban, underserved youth (Mendelson et al. 2010) and high levels of acceptability and feasibility among YEH (Bender et al. 2015; Grabbe et al. 2012). High levels of acceptability were also found for .b among school-aged youth (Kuyken et al. 2013). A study in HIV-positive and at-risk youth showed that of youth who attended any sessions, 79% participated in most sessions (Sibinga et al. 2011). A randomized controlled trial of a mindfulness intervention delivered over 3 days to 97 YEH suggested high intervention engagement and uptake of the practices (Bender et al. 2015). While this intervention improved youths’ attention to internal and external stimuli, the findings suggest that modifications are needed to meet the unique needs of YEH. In a small quasi-experimental study of an MBI delivered weekly over 8 weeks, YEH reported improved emotional well-being from mindfulness practice, were more likely to use mindfulness practice at school and to deal with anger and other difficult emotions, and were more likely to recommend mindfulness to friends, although the differences were non-significant (Viafora et al. 2015).

While the need for prevention and health promotion interventions tailored to the special considerations of this high-risk, complex population is undeniable, they continue to be understudied and underserved. This may be due in part to the challenges faced when working with YEH (Slesnick et al. 2000). However, YEH are eager for health promotion programs, interested, and able to be recruited and retained in interventions and research studies (Gwadz and Rotheram-Borus 1992; Leonard et al. 2003), and demonstrate improved outcomes when programs are tailored and relevant (Bender et al. 2015). Despite the demonstrated need for tailored interventions for YEH and the evidence supporting the ability to recruit and retain this population, few interventions that target risk decision making, emotion regulation, and coping skills have been developed or tested.

In highly stressed populations such as YEH, interventions need to address stress as an antecedent of risk behavior. While community-based interventions have improved risk reduction knowledge among homeless and hard-to-reach youth (Nyamathi et al. 2013a, 2013b; Rew 2003; Rew et al. 2007; Rithpho et al. 2013), this knowledge does not frequently lead to decreases in risk behaviors (Nyamathi et al. 2013a, 2013b). This mindfulness program intervention aimed to give YEH the skills needed to manage stress and regulate their emotions in the moment and thereby make fewer decisions that lead to risk behaviors. By recognizing that YEH often endure trauma, mindfulness approaches align with trauma-informed care and can help youth reframe their life narratives (Bender et al. 2010). We hypothesized that the beneficial effects on stress and executive function would lead to fewer sexual risk behaviors (Brown et al. 2007; Chiesa et al. 2012; Teper and Inzlicht 2013).

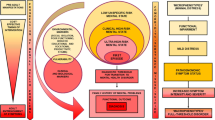

This study was guided by a theoretical framework (see Fig. 1) informed by the Risk Amplification Model (RAM) and the minority stress model (MSTM) (Meyer 2003; Whitbeck et al. 1999). This framework demonstrates that trauma and stress as are a result of abuse, minority status, other sociodemographic, environmental, and psychosocial factors intersect with stress related to homelessness to negatively affect the individual’s stress response and lead to risk behaviors. The model takes into consideration the environmental, sociodemographic, and psychosocial factors contributing to the level of vulnerability and stress experienced by YEH. RAM explains many of the negative outcomes, experiences, and relationships prevalent among YEH (Hendry et al. 2011; McMorris et al. 2002; Tyler et al. 2012, 2000; Tyler and Schmitz 2015; Whitbeck et al. 2000). In a longitudinal study among 347 African American young adults, the authors found a cascade effect from stress to risk behaviors. In our model, similar to RAM, stress leads to increases in negative emotions and risk behaviors; negative emotions have been shown to lead to affiliations with deviant companions (Brody et al. 2010). MSTM posits that stigma, prejudice, and discrimination create stressful environments and affect stress response and coping processes (Meyer 2003).

The purpose of this study was to build on the existing feasibility literature on MBIs among YEH and assess the feasibility and acceptability of a slightly modified version of an existing mindfulness curriculum, .b, with YEH currently residing at a youth homeless shelter in a large metropolitan area in the South. Adaptations made to the curriculum prior to conducting this pilot included consolidating the delivery timeframe to coincide with the average length of shelter stay, increasing the session time to decrease the number of sessions, and eliminating a stress-inducing activity to align with trauma-informed care principles. The session duration and delivery timeframe were modified in an effort to reduce barriers to participation. We hypothesized that .b would be feasible and acceptable to YEH.

Methods

Participants

A total of 39 YEH aged 18–21 were recruited from a youth-serving shelter in Houston, using convenience sampling. Participants in this study had to be 18–24 years of age, speak and understand English, be planning to participate for the duration of the intervention, and currently staying at the shelter, on the streets, or unsure of where they would be staying for the next 30 days on the day of enrollment. The shelter provides drop-in services, crisis housing (limited to about 30 days), transitional supportive housing (up to two years), and supportive community-based rent assistance. In crisis housing, YEH receive shelter, food, healthcare, and supportive services while working with a case manager to assess their needs and develop a plan to gain sustainable housing and a job. In the transitional housing program, YEH work toward independent living in a supportive environment that includes financial planning and life skills training in addition to shelter, food, healthcare, and supportive services. YEH in the transitional supportive housing program are encouraged to work or actively seek employment or attend school. They are assisted in saving part of their income toward costs associated with renting an apartment. All study participants were in the crisis housing program or transitional supportive housing program.

Procedure

Recruitment events were held one to two weeks prior to intervention initiation. Research staff presented a brief overview of the intervention to youth who were at the shelter. Presentations were conducted to align with normally scheduled shelter events, such as prior to or after dinner. This scheduling was done to maximize the number of potential participants who were informed about the study. This research study was approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Two cohorts of youth participated in the study. Prior to completing the consent process, we administered the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine-Short Form (REALMS-SF). Youth were not excluded from the study if they had low literacy; however, accommodations were made to provide assistance. For the participant with a REALMS-SF score lower than four (n = 1), research staff read the informed consent document to the participant and ascertained that the individual understood and agreed to participate.

A research assistant helped participants complete the self-administered 30-min Computer Assisted Self-Interview (CASI) survey at two time points: at baseline prior to the intervention (usually at the time of recruitment) and at 3 weeks post-baseline (post-intervention). The baseline survey inquired about demographics, perceived stress, and risk behaviors though was not powered to conduct analyses. The .b intervention consisted of five biweekly sessions (described below). At each of the five intervention sessions, participants completed a 5-min CASI pre- and post-session survey using Qualtrics delivered on iPads to assess real-time contextual factors and current affect. iPad-delivered Qualtrics surveys were also used for the baseline and immediate post-intervention follow-up surveys. Data from the surveys were downloaded from the iPads and into a centralized database daily. For the participant with a REALMS-SF score lower than four, a research staff member read the survey questions and response choices and entered the participant’s responses.

One month after completing the final session for the two cohorts, a group exit interview was conducted with each of the youth cohorts to discuss participants’ experiences during the intervention, including what youth felt worked and did not work during the intervention sessions, what they thought of the curriculum materials, how they thought sessions could be improved, and their general impressions of the course material. Youth received a $10 gift card to a local grocery store or pharmacy for completion of the baseline and follow-up surveys, participation in the group exit interview, and attendance at each of the five intervention sessions, for a maximum possible total incentive amount of $90.

Intervention description

.b is a MBI curriculum developed by the Mindfulness in Schools Project, from which the intervention was slightly adapted for use in a shelter setting with YEH. It is a 10-lesson curriculum that teaches mindfulness skills in engaging ways for youth. The curriculum comprises youth-friendly visuals, practical exercises, and demonstrations that are engaging and relevant to the lives of young people. While .b is usually delivered as 10 lessons in 10 45-min group sessions over a period of up to 10 weeks in a school setting, we adapted the delivery of the curriculum for the purposes of this feasibility study. To accommodate the typically short length of stay that many YEH experience in the shelter environment, we delivered two 45-min lessons per 90-min group session (a total of five sessions) over a 2.5-week period. Sessions were conducted at a youth homeless shelter by two certified .b facilitators, authors of this manuscript.

One of the authors delivered the content of .b with fidelity as described here. In session one, we introduced mindfulness and covered paying attention, focusing on the breath, sitting meditation, and anchoring the body. In session two, we covered recognizing worry, body scan meditation, mindful eating, and being in the present moment. In session three, we covered mindful movements, walking meditation, and recognizing and minding thought traffic. In session four, we covered stress management, responding versus reacting, and gratitude. In the final session, we summarized the curriculum, reinforced and practiced the mindfulness methods learned, and developed a plan for incorporating mindfulness into daily activities.

To become a certified instructor of .b, individuals must have maintained a personal regular mindfulness practice for at least eight months and must participate in a four-day training course to learn how to deliver the .b intervention with fidelity. Training consists of learning curriculum activities, including review and in-depth discussion of the pedagogy of each lesson, practice delivering lessons, and consideration of how the curriculum can best be taught to youth in different settings, of different ages, and in various cultural, social, and other contexts. The interventionist debriefed with the co-investigator to assure the intervention was delivered with fidelity and to discuss session barriers and facilitators.

Measures

We assessed the feasibility of conducting brief self-administered pre- and post-session surveys delivered by assessing survey completion and acceptability and understandability of the content and the length and timing of administration. These were administered prior to each intervention session and at the conclusion of each session. While these data were collected for feasibility, we also conducted an initial examination of the affective state questions to determine if there was sufficient variability to further assess in future studies.

The baseline survey assessed demographic measures, including race (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, Caucasian or White, multi-racial, other), ethnicity (Hispanic, not Hispanic), gender (male, female, transgender woman, transgender man, gender queer, intersex/non-binary gender, something else), age, sexual orientation (lesbian or gay, straight, bisexual, not sure, other), educational attainment, employment status, homelessness, foster care history, and juvenile justice history, as well as risk behaviors.

To assess current pre- and post-session affect, we used measures based loosely on the Positive and Negative Affect Scale that were modified by the investigative team and the Youth Advisory Committee to reflect positive and negative affects that were most relevant, understandable by YEH, and perceived as most variable (Thompson 2007; Watson et al. 1988) to assess current affect: frustration, stress, hostility, depression, peace, and boredom. To assess frustration, emotional awareness, impulsivity, mindlessness, ability to focus, and mindfulness, youth used a 5-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree with the following respective statements: “Right now, I feel frustrated”; “I am aware of my emotions and feelings right now”; “I feel like I may do something without thinking it through”; “I find myself doing things without paying attention”; “I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present and not get distracted”; and “I find myself preoccupied with the future or the past.”

Feasibility measures included the number of potential participants who consented to participate, the number of intervention sessions attended (range = 0–5), and the percentage of survey data completion. Acceptability of the intervention session content, session length, delivery of skill building and discussion activities, and study logistics was assessed during the post-session surveys and the group exit interviews. We assessed youth satisfaction with the intervention, perceived effects of the intervention, and intentions to continue use of mindfulness practices. The post-session surveys asked participants what they thought of the topics covered in each of the sessions. Answer choices ranged from “I liked it lot” to “I disliked it a lot” using a 5-point Likert scale. For session length and practice time, we asked what youth thought of the time spent on each session and the time spent practicing skills during each session. Answer choices were “too high,” “about right,” and “not enough.” We assessed how participants felt about the amount of time spent on group discussions during the sessions, with answer choices being “It was great,” “It was neither good nor bad,” and “It was bad.” Finally, we asked youth if they would enroll in another study like this one in the future. Using a 4-point Likert scale, answer choices were “I would love to,” “I may consider it,” “Probably not,” and “No way.”

Data Analysis

Quantitative data analysis

Repeated measures analyses with linear mixed models were used to test for changes in the survey measures between pre- and post-session surveys while accounting for differences across sessions. The effects included in the models were time, which tested for overall change between the pre- and post-measures, and session, which tested for overall differences across sessions. Survey measures were assessed for a normal distribution prior to analysis. Statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0.

Qualitative data analysis

Exit interview audio files were reviewed by the investigators to assess emerging themes. First, the audio data were coded using an iterative codebook developed by the authors. Second, quotes were coded and grouped together according to emerging themes. Finally, the investigators summarized the themes that emerged and chose participant quotes that exemplified each theme. To reduce the bias introduced with having the interventionists also analyze the qualitative data, the non-biased authors reviewed the thematic interpretations and exemplar quotes to reach consensus.

Results

Demographics

We had 39 participants enroll in the study. At the time of recruitment, the shelter housed YEH between the ages of 18 and 21. In the total sample, 41% of youth were 18 years old, 33% were 19 years old, and 25.6% were 20 years old (Table 1). All participants spoke English. Participants were primarily male (54%), youth of color (Black = 51.3%, Hispanic = 15.4%), and heterosexual (74.4%). The average length of stay in the shelter was 52 days (range, 1–360 days).

Attendance

We held two cohorts of .b intervention sessions with 22 participants enrolled in the first cohort held in fall 2015 and 17 enrolled in the second cohort held in winter 2016. Some (n = 6, 15%) of the 39 participants who consented to be in the study were discharged from the shelter before attending any sessions. We did not track whether the discharge from the shelter was voluntary or involuntary. All youth completed the baseline survey and are therefore included in the findings presented in this manuscript. On average, participants attended 2.2 of the five sessions, with 17 (44%) attending more than 50% of the sessions. The average number of participants who attended each of the sessions was 8.6 (range = 4–13). Session attendance dropped during the five-session course with 21 participants attending session one, 19 attending session 2, 16 attending both session 3 and session 4, and 14 attending the final session. No differences were found between the two cohorts in attendance or number of youth participating per session.

Data Completeness

Baseline surveys were completed by 39 youth. Matched pre- and post-session survey completeness for all sessions was 92% (range, 87–94%). Exit surveys were completed by 12 (31%) participants, and 10 (26%) youth completed a group exit interview.

Qualitative Findings

“It was inspirational.” In general, youth in the group exit interview found the sessions to be useful and engaging. Regarding acceptability, youth described how the content helped them with their emotions. One female participant said, “It helped me get through a lot of stuff. It was inspirational. I love it. I would do it again and again. It helped me face some challenges I had.” Others agreed that the course was an improvement from mandatory anger management classes. “It was way better than anger management class. I actually feel calm after this class and not more angry,” said one female. Participants described the exercises they learned in the sessions and the effects they had. A male participant shared, “I like the deep breathing exercise. It was very calming.” Another participant suggested that the content and activities helped her restructure how she related to her feelings. She said, “It made me think of my feelings and day in a different way.” Another participant commented that she liked the togetherness and cohesion formed during the group activities. She reflected, “We all did it together as a team and I liked that.” In the same light, one female participant reported that the pre-session surveys set the tone for self-reflection. She shared, “I like the [pre-session] survey in the beginning because you are going through your day…how you feel.” Another female participant described the effect of the post-session survey, “It made me think about how I want my next week to be.” One female participant described the effect she saw the sessions have on other participants. She said, “For people who came in super jittery, when they started to do the deep breathing, they got all calm. It relaxed them.”

“That was helpful.” When we asked youth how they felt about the logistics of the sessions, including timing, spacing, length, location, facilitators, and barriers to attendance, we gleaned important data to suggest what to preserve and what to change in future applications of this curriculum. One female participant who struggled to make all the sessions said, “For some people, work….after work, I’d be so tired.” Others described the length of the sessions, “It [the length] was perfect.” And a female youth said, “Whoever came up with…twice a week…was perfect.” Another female participant described the importance of refresher sessions for those who skipped a session so they could quickly catch up on missing content, “If we missed that day, you’d go over some of the stuff that we missed. That was helpful.” Participants liked the use of media to concretize the concepts reviewed. A female youth said, “I’m a visual learner. So, it [PowerPoint slides and videos] helped a lot.” Several participants did not like the walking meditation exercise, including one female who said, “The walking one was strange. I didn’t like that one.” Other exercises were strongly endorsed by the participants.

Potential Adaptations. When we asked youth what they would do to make the course better, they mentioned the several ways we could improve the class. One recommended “more video clips, more activities, more hands-on things, squeezy stress balls, and meditation bells.” A male participant suggested the use of an app to increase access to guided meditations between sessions and after the course ended, “An app on the phone or computer for those who don’t have a phone.” Others agreed that this would be a helpful feature. Another female participant also suggested an activity or reminder to serve as a cue to action to use the new skills in the heat of the moment when they are needed most but often forgotten, “Having something to remind you, to remember to do them. Especially when I am angry.” When asked about adaptations that we should consider making, a female participant suggested, “There wasn’t really anything to dislike.”

Post-Intervention Survey Data

The post-session surveys indicated that the majority of participants (74.1%) liked the topics covered in the sessions (Table 2). However, this proportion ranged from 53.8 to 95.2% and satisfaction seemed to decline from session one to session five. Both time spent in the session and time practicing skills were scored at “about right” by the majority of youth (82.9 and 80.0%, respectively). Group discussion time scored lower, with only 69.1% of youth indicating it was “great” across all sessions. While across all sessions, only 57.8% of youth indicated they would “love to enroll” in a similar study in the future, there was a small upward trend from 52.4% at session one to 76.9% at session five.

Pre- and Post-Session Outcomes

While the main focus of this study was to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the delivery of the intervention among sheltered YEH, we did pilot the measures and surveys to assess their sensitivity to change from pre- to post-session. Table 3 describes the changes in pre- and post-session measures. Several significant findings are highlighted, including improvements in levels of frustration, restlessness, stress, depression, boredom, and mindlessness. Finally, no intervention-related adverse incidents or outcomes were reported.

Discussion

We examined the feasibility and acceptability of an adapted mindfulness intervention among sheltered YEH using mixed methods. The intervention appeared to show initial feasibility, though the data suggest that modifications are needed to increase the relevance and accessibility of multi-session mindfulness interventions among YEH. Significant improvements in post-session frustration, restlessness, stress, depression, boredom, and mindlessness indicate the potential efficacy of this intervention, which needs to be further explored in a randomized trial. Youth also reported in the exit interview improvements in emotion regulation and calmness. Additionally, there was an upward trend in youth’s eagerness to enroll in future studies. This could be due to having been exposed to more of the session content or having spent more time in the shelter. The findings of this study build on the growing evidence that MBIs are feasible and acceptable among YEH (Viafora et al. 2015; Bender et al. 2015).

Our findings suggest that several additional significant adaptations are needed prior to rigorously testing the feasibility of this intervention. Specifically, data from this pilot suggest that sessions need to be held more proximal to recruitment and enrollment events to reduce participant loss to follow-up, a common concern among YEH (Viafora et al. 2015; Bender et al. 2015). Youth suggest that it is essential to host more than one opportunity to attend each session (i.e., make-up sessions) and to allow cohorts to influence the day and time of session delivery due to substantial differences in work, school, and appointment scheduling. The intervention needs to be brief with a consolidated delivery timeframe from traditional eight-week mindfulness courses to better align with the average time spent in shelters as a means of reducing study attrition. As well, it is important to offer light snacks and beverages to assure participants’ basic needs are met first to promote the learning environment. While adaptations are needed, we found that delivering the intervention over 2–3 weeks approximated the mean time YEH spent in a shelter. Post-session survey data also found that the total time spent in the sessions and the amount of time spent practicing skills scored high among participants.

These data suggest that, moving forward, several adaptations need to be made to the curriculum content. First, modifications to the scenarios, images used, concretization of concepts and practices, and adaptations to the body scan skill-building exercise should be done using a trauma-informed framework to increase relevance. The post-session surveys suggested a decline in the likeability of the session topics, indicating a need to revisit the topics covered in low-scoring sessions. Group discussion time also scored lower, indicating that not enough time was spent in discussion activities. Finally, there was a slight upward trend in youth indicating they would love to enroll in a similar study in the future. This trend suggests that the logistics associated with the study implementation were well tolerated by youth.

Several logistical considerations can be made from these data to further research the use of and effects of MBIs among YEH. Session delivery timing (e.g., day of the week, time of day) should be determined using a group-based decision model so as to align with cohort availability based on variations in morning, afternoon, or evening work schedules and obligations. Measuring pre- and post-session outcomes had high rates of data completeness. However, for longer term follow-up, a staff person dedicated to retention and participant tracking is needed to complete participant follow-up given the mobility of YEH. While not tested here, it may be advantageous to provide study phones to increase participant tracking and follow-up, while also increasing participant access to free mindfulness apps and resources to enhance guided practice. Another option may be to make guided practices available to youth for download on their personal phone or accessible at local libraries and drop-in center and shelter computers. It is important to adapt this intervention using a participatory action approach (Baum et al. 2006) with YEH as partners to assure the intervention is relevant and easily accessible to YEH given their unique challenges.

Limitations

This small pilot study used a slightly modified delivery modality of an existing mindfulness curriculum that was not designed for or tested among shelter-dwelling YEH. Because of the small sample size and specialized population, the results should be interpreted with caution. We targeted youth at a shelter versus other homeless service provider locations such as drop-in day centers or clinics. We did this under the assumption that it may be more feasible to reach youth at a location that they would frequent consistently. Therefore, the data only suggest potential feasibility of mindfulness curricula among similarly situated shelter-dwelling YEH. While this study offers some additional data on the feasibility of mindfulness interventions among YEH, it also suggests major adaptations needed prior to rigorous feasibility testing. Only 44% of participants attended more than half of the sessions, suggesting the need for modifications to increase accessibility as outlined above. Further, while no adverse outcomes or incidents were noted, we did not have an independent data safety and monitoring board for a non-biased review. Additionally, this study was not designed to assess pre- and post-intervention effects or waning of intervention effects over time. Future studies should consider rigorous, randomized, longitudinal study designs with adequate sample sizes to assess multiple outcomes and waning intervention effects. Despite the limitations noted, this study builds on the literature and provides additional evidence of the potential feasibility of providing mindfulness interventions to YEH and suggests specific adaptations needed to further assess feasibility.

References

Aidala, A., Cross, J. E., Stall, R., Harre, D., & Sumartojo, E. (2005). Housing status and HIV risk behaviors: implications for prevention and policy. AIDS and Behavior, 9(3), 251–265.

Andres-Lemay, V. J., Jamieson, E., & MacMillan, H. L. (2005). Child abuse, psychiatric disorder, and running away in a community sample of women. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 50(11), 684–689.

Bassuk, E., Murphy, C., Coupe, N., Kenney, R., & Beach, C. (2011). America’s youngest outcasts 2010. Needham, MA: The National Center on Family Homelessness.

Bassuk, E., Murphy, C., Coupe, N., Kenney, R., & Beach, C. (2014). America’s youngest outcasts 2014: State report card on child homelessness. Needham, MA: The National Center on Family Homelessness.

Bassuk, E. L. (2010). Ending child homelessness in America. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(4), 496–504.

Baum, F., MacDougall, C., & Smith, D. (2006). Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 60(10), 854–857.

Bender, K., Begun, S., DePrince, A., Haffejee, B., Brown, S., Hathaway, J., & Schau, N. (2015). Mindfulness intervention with homeless youth. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 6(4), 491–513.

Bender, K., Brown, S. M., Thompson, S. J., Ferguson, K. M., & Langenderfer, L. (2015). Multiple victimizations before and after leaving home associated with PTSD, depression, and substance use disorder among homeless youth. Child Maltreatment, 20(2), 115–124.

Bender, K., Ferguson, K., Thompson, S., Komlo, C., & Pollio, D. (2010). Factors associated with trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder among homeless youth in three US cities: the importance of transience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(1), 161–168.

Biegel, G. M., Brown, K. W., Shapiro, S. L., & Schubert, C. M. (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for the treatment of adolescent psychiatric outpatients: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(5), 855–866.

Black, D. S., Milam, J., & Sussman, S. (2009). Sitting-meditation interventions among youth: a review of treatment efficacy. Pediatrics, 124(3), e532–e541.

Bowleg, L., Fitz, C. C., Burkholder, G. J., Massie, J. S., Wahome, R., Teti, M., Malebranch, D. J., & Tschann, J. M. (2014). Racial discrimination and posttraumatic stress symptoms as pathways to sexual HIV risk behaviors among urban Black heterosexual men. AIDS Care, 26(8), 1050–1057.

Brody, G. H., Chen, Y.-F., & Kogan, S. M. (2010). A cascade model connecting life stress to risk behavior among rural African American emerging adults. Development and Psychopathology, 22(03), 667–678.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848.

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 211–237.

Burke, C. A. (2010). Mindfulness-based approaches with children and adolescents: a preliminary review of current research in an emergent field. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 133–144.

Carmona, J., Slesnick, N., Guo, X., & Letcher, A. (2014). Reducing high risk behaviors among street living youth: outcomes of an integrated prevention intervention. Children and Youth Services Review, 43, 118–123.

Cauce, A. M., Paradise, M., Ginzler, J. A., Embry, L., Morgan, C. J., Lohr, Y., & Theofelis, J. (2000). The characteristics and mental health of homeless adolescents: age and gender differences. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 8(4), 230–239.

Chiesa, A., Serretti, A., & Jakobsen, J. C. (2012). Mindfulness: top-down or bottom-up emotion regulation strategy? Clinical Psychology Review, 33(1), 82–96.

Cornelius, J., Kirisci, L., Reynolds, M., & Tarter, R. (2014). Does stress mediate the development of substance use disorders among youth transitioning to young adulthood? The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 40(3), 225–229.

Davydov, D. M., Shapiro, D., Goldstein, I. B., & Chicz-DeMet, A. (2005). Moods in everyday situations: effects of menstrual cycle, work, and stress hormones. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58(4), 343–349.

Delker, B. C., & Freyd, J. J. (2014). From betrayal to the bottle: investigating possible pathways from trauma to problematic substance use. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(5), 576–584.

Dermen, K. H., & Thomas, S. N. (2011). Randomized controlled trial of brief interventions to reduce college students’ drinking and risky sex. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(4), 583–594.

Edidin, J. P., Ganim, Z., Hunter, S. J., & Karnik, N. S. (2012). The mental and physical health of homeless youth: a literature review. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 43(3), 354–375.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258.

Fjorback, L., Arendt, M., Ørnbøl, E., Fink, P., & Walach, H. (2011). Mindfulness‐Based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness‐Based Cognitive Therapy—a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124(2), 102–119.

Flook, L., Smalley, S. L., Kitil, M. J., Galla, B. M., Kaiser-Greenland, S., Locke, J., Ishijima, E., & Kasari, C. (2010). Effects of mindful awareness practices on executive functions in elementary school children. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 26(1), 70–95.

Gaetz, S. (2004). Safe streets for whom? Homeless youth, social exclusion, and criminal victimization. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 46(4), 423–456.

Gaetz, S. (2009). Backgrounder: who are street youth. Toronto: York University.

Garland, E. L., Roberts-Lewis, A., Tronnier, C. D., Graves, R., & Kelley, K. (2016). Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement versus CBT for co-occurring substance dependence, traumatic stress, and psychiatric disorders: proximal outcomes from a pragmatic randomized trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 7–16.

Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E. M., Gould, N. F., Rowland-Seymour, A., Sharma, R., Berger, Z., Sleicher, D., Maron, D. D., Shihab, H. M., & Ranasinghe, P. D. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 357–368.

Grabbe, L., Nguy, S. T., & Higgins, M. K. (2012). Spirituality development for homeless youth: a mindfulness meditation feasibility pilot. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(6), 925–937.

Grant, R., Shapiro, A., Joseph, S., Goldsmith, S., Rigual-Lynch, L., & Redlener, I. (2007). The health of homeless children revisited. Advances in Pediatrics, 54(1), 173–187.

Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: a meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(1), 35–43.

Gwadz, M., & Rotheram-Borus, M. J. (1992). Tracking high-risk adolescents longitudinally. AIDS Education and Prevention, Suppl, 69–82.

Hall, K. S., Kusunoki, Y., Gatny, H., & Barber, J. (2014a). The risk of unintended pregnancy among young women with mental health symptoms. Social Science & Medicine, 100, 62–71.

Hall, K. S., Kusunoki, Y., Gatny, H., & Barber, J. (2014b). Stress symptoms and frequency of sexual intercourse among young women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11(8), 1982–1990.

Hall, K. S., Kusunoki, Y., Gatny, H., & Barber, J. (2015). Social discrimination, stress, and risk of unintended pregnancy among young women. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(3), 330–337.

Hall, K. S., Moreau, C., Trussell, J., & Barber, J. (2013a). Role of young women’s depression and stress symptoms in their weekly use and nonuse of contraceptive methods. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(2), 241–248.

Hall, K. S., Moreau, C., Trussell, J., & Barber, J. (2013b). Young women’s consistency of contraceptive use–does depression or stress matter? Contraception, 88(5), 641–649.

Hendry, D. G., Woelfer, J. P., Harper, R., Bauer, T., Fitzer, B., & Champagne, M. (2011). How to integrate digital media into a drop-in for homeless young people for deepening relationships between youth and adults. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(5), 774–782.

Hoppmann, C. A., & Klumb, P. L. (2006). Daily goal pursuits predict cortisol secretion and mood states in employed parents with preschool children. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68(6), 887–894.

Hulland, E. N., Brown, J. L., Swartzendruber, A. L., Sales, J. M., Rose, E. S., & DiClemente, R. J. (2014). The association between stress, coping, and sexual risk behaviors over 24 months among African-American female adolescents. Psychology, Health & Medicine (ahead-of-print), 20, 1–14.

Jha, A. P., Stanley, E. A., Kiyonaga, A., Wong, L., & Gelfand, L. (2010). Examining the protective effects of mindfulness training on working memory capacity and affective experience. Emotion, 10(1), 54–64.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4(1), 33–47.

Kingston, S., & Raghavan, C. (2009). The relationship of sexual abuse, early initiation of substance use, and adolescent trauma to PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(1), 65–68.

Kulik, D. M., Gaetz, S., Crowe, C., & Ford-Jones, E. L. (2011). Homeless youth’s overwhelming health burden: a review of the literature. Paediatrics & Child Health, 16(6), e43.

Kuyken, W., Weare, K., Ukoumunne, O. C., Vicary, R., Motton, N., Burnett, R., Cullen, C., Hennelly, S., & Huppert, F. (2013). Effectiveness of the Mindfulness in Schools Programme: non-randomised controlled feasibility study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 203(2), 126–131.

Leonard, N. R., Lester, P., Rotheram-Borus, M. J., Mattes, K., Gwadz, M., & Ferns, B. (2003). Successful recruitment and retention of participants in longitudinal behavioral research. AIDS Education and Prevention, 15(3), 269–281.

Lovallo, W. R. (2013). Early life adversity reduces stress reactivity and enhances impulsive behavior: implications for health behaviors. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 90(1), 8–16.

Mallett, S., Rosenthal, D., & Keys, D. (2005). Young people, drug use and family conflict: pathways into homelessness. Journal of Adolescence, 28(2), 185–199.

Martijn, C., & Sharpe, L. (2006). Pathways to youth homelessness. Social Science & Medicine, 62(1), 1–12.

Mayock, P., Corr, M. L., & O’Sullivan, E. (2011). Homeless young people, families and change: family support as a facilitator to exiting homelessness. Child & Family Social Work, 16(4), 391–401.

McMorris, B. J., Tyler, K., Whitbeck, L. B., & Hoyt, D. R. (2002). Familial and “on-the-street” risk factors associated with alcohol use among homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63(1), 34–43.

Mendelson, T., Greenberg, M. T., Dariotis, J. K., Gould, L. F., Rhoades, B. L., & Leaf, P. J. (2010). Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a school-based mindfulness intervention for urban youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(7), 985–994.

Merscham, C., Van Leeuwen, J. M., & McGuire, M. (2009). Mental health and substance abuse indicators among homeless youth in Denver, Colorado. Child Welfare, 88(2), 93–110.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697.

Morton, M. H., Dworsky, A., & Samuels, G. M. (2017). Missed opportunities: youth homelessness in America. National estimates. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

Narendorf, S. C., Bowen, E., Santa Maria, D., & Thibaudeau, E. (2018). Risk and resilience among young adults experiencing homelessness: a typology for service planning. Children and Youth Services Review, 86, 157–165.

Nyamathi, A., Kennedy, B., Branson, C., Salem, B., Khalilifard, F., Marfisee, M., Getzoff, D., & Leake, B. (2013a). Impact of nursing intervention on improving HIV, hepatitis knowledge and mental health among homeless young adults. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(2), 178–184.

Nyamathi, A., Salem, B., Reback, C. J., Shoptaw, S., Branson, C. M., Idemundia, F. E., Kennedy, B., Khalilifard, F., Marfisee, M., & Liu, Y. (2013b). Correlates of hepatitis B virus and HIV knowledge among gay and bisexual homeless young adults in Hollywood. American Journal of Men’s Health, 7(1), 18–26.

Parsons, J. T., Lelutiu-Weinberger, C., Botsko, M., & Golub, S. A. (2012). Predictors of day-level sexual risk for young gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior, 17, 1–13.

Rew, L. (2003). A theory of taking care of oneself grounded in experiences of homeless youth. Nursing Research, 52(4), 234–241.

Rew, L., Fouladi, R. T., Land, L., & Wong, Y. J. (2007). Outcomes of a brief sexual health intervention for homeless youth. Journal of Health Psychology, 12(5), 818–832.

Rew, L., Johnson, K., & Young, C. (2014). A systematic review of interventions to reduce stress in adolescence. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35(11), 851–863.

Rithpho, P., Grimes, D. E., Grimes, R. M., Nantachaipan, P., & Senaratana, W. (2013). A nursing intervention to enhance the self-care capacity of nondisclosed persons living with HIV in Thailand. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 24(6), 512–520.

Robbins, R. N., & Bryan, A. (2004). Relationships between future orientation, impulsive sensation seeking, and risk behavior among adjudicated adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19(4), 428–445.

Roy, É., Haley, N., Leclerc, P., Sochanski, B., Boudreau, J.-F., & Boivin, J.-F. (2004). Mortality in a cohort of street youth in Montreal. Journal of the American Medical Association, 292(5), 569–574.

Santa Maria, D. M., Narendorf, S. C., Bezette-Flores, N., & Ha, Y. (2015). “Then You Fall Off”: youth experiences and responses to transitioning to homelessness. Journal of Family Strengths, 15(1), 5.

Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L. E., Astin, J. A., & Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 373–386.

Sibinga, E. M., Kerrigan, D., Stewart, M., Johnson, K., Magyari, T., & Ellen, J. M. (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for urban youth. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 17(3), 213–218.

Sibinga, E. M., Perry-Parrish, C., Chung, S.-e, Johnson, S. B., Smith, M., & Ellen, J. M. (2013). School-based mindfulness instruction for urban male youth: a small randomized controlled trial. Preventive Medicine, 57(6), 799–801.

Sibinga, E. M., Webb, L., Ghazarian, S. R., & Ellen, J. M. (2016). School-based mindfulness instruction: an RCT. Pediatrics, 137(1), e20152532.

Siegel, R. D., Germer, C. K., & Olendzki, A. (2009). Mindfulness: What is it? Where did it come from? In F. Didonna (Ed.), Clinical handbook of mindfulness (17–35). New York, NY: Springer.

Slesnick, N., Meyers, R. J., Meade, M., & Segelken, D. H. (2000). Bleak and hopeless no more: engagement of reluctant substance-abusing runaway youth and their families. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 19(3), 215–222.

Teper, R., & Inzlicht, M. (2013). Meditation, mindfulness and executive control: the importance of emotional acceptance and brain-based performance monitoring. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(1), 85–92.

Teper, R., Segal, Z. V., & Inzlicht, M. (2013). Inside the mindful mind: how mindfulness enhances emotion regulation through improvements in executive control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(6), 449–454.

Thompson, E. R. (2007). Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38(2), 227–242.

Tyler, K. A., Gervais, S. J., & Davidson, M. M. (2012). The relationship between victimization and substance use among homeless and runaway female adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(3), 474–493.

Tyler, K. A., Hoyt, D. R., & Whitbeck, L. B. (2000). The effects of early sexual abuse on later sexual victimization among female homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15(3), 235–250.

Tyler, K. A., & Schmitz, R. M. (2015). Effects of abusive parenting, caretaker arrests, and deviant behavior on dating violence among homeless young adults. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 24(10), 1134–1150.

Viafora, D. P., Mathiesen, S. G., & Unsworth, S. J. (2015). Teaching mindfulness to middle school students and homeless youth in school classrooms. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(5), 1179–1191.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070.

Webb, L., Perry-Parrish, C., Ellen, J., & Sibinga, E. (2018). Mindfulness instruction for HIV-infected youth: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Care, 30(6), 688–695.

Whitbeck, L. B., Hoyt, D. R., & Bao, W. N. (2000). Depressive symptoms and co-occurring depressive symptoms, substance abuse, and conduct problems among runaway and homeless adolescents. Child Development, 71(3), 721–732.

Whitbeck, L. B., Hoyt, D. R., & Yoder, K. A. (1999). A risk-amplification model of victimization and depressive symptoms among runaway and homeless adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27(2), 273–296.

Williams, J. K., Glover, D. A., Wyatt, G. E., Kisler, K., Liu, H., & Zhang, M. (2013). A sexual risk and stress reduction intervention designed for HIV-positive bisexual African American men with childhood sexual abuse histories. American Journal of Public Health, 103(8), 1476–1484.

Wong, C. F., Kipke, M. D., Weiss, G., & McDavitt, B. (2010). The impact of recent stressful experiences on HIV-risk related behaviors. Journal of Adolescence, 33(3), 463–475.

Zenner, C., Herrnleben-Kurz, S., & Walach, H. (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions in schools—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 603.

Zlotnick, C. (2009). What research tells us about the intersecting streams of homelessness and foster care. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(3), 319–325.

Zoogman, S., Goldberg, S. B., Hoyt, W. T., & Miller, L. (2015). Mindfulness interventions with youth: a meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 6(2), 290–302.

Author Contributions

DSM and PC: designed and executed the study, assisted with the data analyses, and wrote the paper. MF, ES, and KB: collaborated with the writing and editing of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Santa Maria, D., Cuccaro, P., Bender, K. et al. Feasibility of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention with Sheltered Youth Experiencing Homelessness. J Child Fam Stud 29, 261–272 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01583-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01583-6