Abstract

We estimate gender earnings differentials among Hollywood stars. While this market should be particularly efficient in translating productivity into earnings, we demonstrate an unexplained female earnings gap of over two million dollars a film. Critically, we show that action films drive this gap. Our movie fixed effects estimate a much larger-million-dollar gap among action movies and a smaller statistically insignificant gap among other genres. Within the other genres, the one significant earnings gap is among stars older than 50. We argue that these patterns could reflect “consumer discrimination” but also raise other possibilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Vanity Fair (2016) reported that the three superstars of “American Hustle” each worked 45–46 days on the filming with Christian Bale and Bradley Cooper each earning $2.5 million and 9% of the profits while Amy Adams earned $1.25 million and 7% of the profits. At the 2015 Oscars, Patricia Arquette expressed growing discontent with large gender earnings differences and further comments followed from Meryl Streep, Charlize Theron, Jennifer Lawrence and Natalie Portman each urging Hollywood to live up to “equal pay for an equal job”. Yet, as we will make clear in the next section, the economic research on the issue remains modest and contradictory despite this popular narrative. Indeed, some past studies fail to confirm an unexplained gender earnings gap among film stars and additional study is warranted.

We demonstrate that the popular narrative partially reflects reality as taking all movies and stars together there exists a robust and routinely significant unexplained earnings disadvantage for women stars of over two million dollars per film. Yet, the popular narrative misses the critical role played by action movies. We show that an enormous disadvantage exists within these films that drives the overall result. The disadvantage in other genres is far smaller and often not statistically significant.

Such a result may reflect shared customer preferences about the gender of the lead they want in action movies. It could also be that producers and studios have a prejudice for male leads in action films that the public does not share or that producers and studios incorrectly believe the public prefers male leads in action films. Despite this ambiguity, our examination uniquely brings to the fore the critical role played by action films in creating the Hollywood gender wage difference. The overall gap comes largely from casting men as high paid leads in action films. Identifying this is a critical contribution of our work.

This contribution is important. If consumers share a preference for male action leads (and the resulting willingness to pay), it leaves in doubt whether the overall earnings difference reflects Arrow’s (1973) definition of discrimination as when “personal characteristics of the worker unrelated to productivity are valued in the marketplace”. Instead, it may be the case that in action movies gender itself brings enhanced utility to movie goers and so gender itself is related to productivity. Such cases are both legally and socially contentious (Cantor, 1999). On the other hand, if it reflects a lack of knowledge or prejudice by producers and studios, public policy and scrutiny should now be targeted on the gender and earnings of leads in action films.

In keeping with our emphasis on action films we also present dynamic estimates showing that neither experience nor age plays a large role in the pattern of the gender differential within action movies. Within other genres, the differential is nearly zero until age 50 at which age it becomes large and significant. Yet, those with more experience (other than the extremely old) have similar earnings by gender. This suggests that ageing itself (not a lack of investment in training and human capital) hurts female stars and it raises questions about gender, ageing and perceptions of beauty that we discuss.

In the next section we set the stage by defending Hollywood as an important case study, by examining the modest past research on stars and by placing our study in the context of broader inquiries into gender differentials. The third section presents our data and descriptive statistics. The fourth section presents the estimations showing robustness to a wide variety of methodological and specification variations. The fifth section presents the analysis of age and experience, and the final section concludes.

2 Motivation and context

The Hollywood movie industry generates 4% of the US GDP and employs more than 2 million workers (National Endowment for the Arts and the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2012). Yet, famous Hollywood stars comprise only the tiniest fraction of this work force and only a very small fraction of all movie actors (Adler, 1985). The research question of whether female movie stars earn less falls within the broad literature on gender wage differentials (see Blau & Kahn, 2017; Olivetti & Petrongolo, 2016 for recent surveys) and within the narrower but still enormous literature on gender wage differentials within highly paid professions.Footnote 1 Despite the size of these studies, Hollywood stars provide an important case study.

2.1 Hollywood stars as a case study

A series of features argue for examining the market for Hollywood stars. First, these stars represent the top echelons of a large and influential industry. As the world’s largest film centre, Hollywood represents a huge economic and cultural export (Oxford Economics, 2012). It reflects current cultural life and addresses relevant social challenges. It influences other aspects of society including tourism, politics and other forms of art and expression (Bolan & Williams, 2008). Moreover, Hollywood celebrities routinely influence public discourse and politics (Chong & Berger, 2010), suggesting they could be an important voice on the gender pay gap.

Second, as an illustration of “the economics of superstars” (Rosen, 1981), studying Hollywood sheds light on wage inequality and talent distribution (Adler, 1985). Like other superstar markets such as those in sports, music and high finance, film superstars earn massively higher earnings than their peers despite what some see as modest skill differences (Hofmann & Optiz, 2019; Terviö, 2009).Footnote 2 Unlike those other markets, Hollywood has a long history of substantial representation by women doing the same job.

Third, unlike most other labour markets, long-term contracts have vanished. Contracts are negotiated actor by actor and movie by movie. This allows stars to more nearly be paid according to their current individual performance, productivity and contribution to a specific film.Footnote 3 Indeed, our strong controls provide a reasonable proxy for that contribution. We know the revenue and production budget costs of each current film (the components of its profitability). We control for the revenues associated with each actor’s past movies, for their past awards and for measures of their popularity among many other earnings determinants. Thus, Hollywood stars provide a unique market setting with unusually strong measures of worker contribution.Footnote 4

Fourth, stars of different genders typically perform in the same movies. They largely do the same work, at the same time and in the same location. Thus, the extent of occupational segregation may be smaller than in other markets. Among leading lawyers, women tend to be well represented among the best law school faculties and judgeships but underrepresented among major corporate law firms (Noonan et al., 2005; Wood et al., 1993). The first set of jobs are perceived as more family friendly and the latter as both less family friendly and perhaps less welcoming to women. Thus, the portions of earnings differentials associated with occupational crowding or with “rational choices among work and family” are likely better controlled in our study where such segregation is less common. Indeed, Hollywood has a very long history of men and women having roughly equal work hours, job conditions and schedules (Bielby & Bielby, 1996).

Fifth, the broader literature argues that women are less likely to engage in competitive interactions such as negotiations (Bertrand, 2011; Card et al., 2016; Croson & Gneezy, 2009). Women either avoid negotiations or negotiate poorly (Babcock & Laschever, 2003) causing increased gender earnings differences (Stuchlmacher & Walters, 2006). In contrast, Hollywood stars retain professional agents that negotiate on their behalf. Agents receive a share of the negotiated earnings (typically 10% for screen actors guild positions) and it is recognized by stars of both genders “that it is imperative to find an agent who is tenacious and aggressive” (Morgan, 2017). Moreover, the same agent or agency frequently represents stars of different genders. The presence of professional agents should reduce the importance of any gender-based behavioural differences in negotiations.

These important features argue that the market for Hollywood stars is a critical case study. Many of the suspected causes for gender earnings differences evident in other labour markets appear less important in this market.

2.2 Past evidence

Despite this strong argument, only a modest number of previous studies exist, because of data limitations. Lincoln and Allen (2004) provide a broad sweep of the historical pattern of hiring male and female actors. They examine 15 thousand film roles over 70 years. Males received more movie roles, and this difference grew with age. Fleck and Hanssen (2016) identify nearly a half-million roles over 90 years. While the roles are disproportionately male, they find a more nuanced age-related pattern. Women had most of the roles for younger actors while men have had most of the roles for older actors. This pattern has been relatively stable over time and is reflected in the average age of male Oscar winners being greater than that of female Oscar winners (Gilberg & Hines, 2000). Aguiar (2023) shows that female-dominated movies receive lower rating scores from crowd-based ratings such as rotten tomatoes suggesting a gender gap in the preferences of crowd raters. These examinations do not study earnings.

De Pater et al. (2014) show that this pattern of roles appears to be roughly reflected in earnings. They examine average annual earnings in a sample in which only the most recent year a star appeared in a movie is used. In this cross section of 265 stars, the earnings of male stars reach a maximum at age 51 while those for women stars reach a maximum at 34. The controls are parsimonious, limited to award nominations, number of previous roles, age and star presence. Nonetheless, the results broadly mimic the data on role availability. They confirm an interaction of gender and age. Female stars earn more than men at young ages and earn less at older ages. Critically, the authors simply do not find a significant average unexplained gender difference in their earnings measure once accounting for this interaction.

A related line of study assumes that star popularity drives box-office results and focuses on the role of gender in that association (Treme & Craig, 2013).Footnote 5 Treme et al. (2018) conclude that having a male star in a film generates a revenue premium larger than having a female star and argue this would be consistent with a gender compensation differential. They do not explicitly measure that gender compensation differential. Linder et al. (2015) show a similar premium in revenue but suggest a different cause. They show that it reflects smaller production budgets for movies that feature women and argue that this difference in “upstream” investments may itself be discriminatory.

The assumption of this literature that star popularity drives revenue and profitability has been questioned. First, the distribution of movie profitability is so extremely skewed (“winner take all”) that to pay a star his/her expected profit almost surely guarantees a loss (De Vany & Walls, 2004). Second, several studies suggest that star power does not drive revenue or profitability. Hennig-Thurau et al. (2006) show that sequels generate the greatest revenue and profitability. Stars are so expensive that studios try to find lesser-known actors and sign them to multiple film sequel deals. Nonetheless, they recognize that securing stars can be crucial in securing large scale production funding. Suarez-Vazquez (2011) approaches this differently showing experimentally that consumers do not regard a cast of stars as an indicator of quality.

Yet, evidence suggests that while big stars have little influence on profitability, they do influence revenue and how it is divided (see De Vany, 2004; Elberse, 2007; Nelson & Glotfelty, 2012). The implication is that the stars, not the studios, capture the rents associated with stardom. In their meta-analysis Hofmann et al. (2017) conclude that movies with a commercially successfully star earn 12.5 million dollars extra in revenue. This evidence implies that controlling for the past revenue of a star’s films is an important determinant of what a studio is willing to pay for a star’s next movie. We uniquely generate such a measure.

Research suggests that beauty comes with a wage premium (Biddle & Hamermesh, 1998; Hamermesh & Biddle, 1994). Moreover, this premium has been shown to be larger for women and to be associated with age. Indeed, one might anticipate an even more sharply increasing gender penalty for age in a highly visual media like film. Again, we uniquely examine the role played by action movies. Action movies may be less susceptible to female age penalties if the primary purpose is to deliver the rush of adventure and violence through male leads. Indeed, the options for older stars of either gender may be limited in action films. In this view, romances or other genres might be much more likely to generate the pattern of growing female age penalties. We examine the dynamics of the wage gap separately by action and other genres.

We contrast this with an examination of years of experience. The gender earnings gap grows with experience for academics (Johnson & Stafford, 1974), for lawyers (Noonan et al., 2005; Wood et al., 1993), for physicians (Esteves-Sorenson & Snyder, 2012) and for business executives (Bertrand et al., 2010). This pattern reflects women experiencing career interruptions and/or investing less in specific human capital. Moreover, any such decisions can be compounded by unequal advancement opportunities and promotions that generate a growing gender earnings gap over a career referred to as a “glass ceiling”. Using years since first movie, we uniquely examine if the earnings gap grows with experience as might be predicted.

2.3 Our value-added

The reviewed studies make clear that there exists ample room for an improved examination of the gender earnings differential. We use more movies than previous studies and are the first to have multiple movies per star. Our use of star by movie observations reflects the fact that stars negotiate movie by movie. It allows star earnings from a given film to reflect the success of the actor’s previous films which others have not included even though this would be a logical concern when negotiating current earnings. Critically, our star by movie structure does not conflate the extensive and intensive margin as do past measures of annual earnings, average earnings per film or average annual earnings per film.

We uniquely demonstrate an enormous gender earnings gap in action movies that drives the overall gap. The extremely high earnings of male action leads could reflect societal preferences on gender roles. Miller et al. (2016) contend that the "rush" from watching action, violence and power remains largely associated with males by society and by movie goers. While one can argue that this societal view should not persist, it may nonetheless be translated into viewer preferences. Male stars may deliver the rush more effectively in the eyes of consumers of either gender (Addis & Holbrook, 2010). This does not deny that continuing to cast males in these roles may reinforce such social preferences. Nor can we rule out that producers share an incorrect view of societal preferences or that they have their own prejudice about the gender of such roles. Moreover, customer preferences and/or producer’s view of them may be changing more recently with films such as Salt, Captain Marvel and Wonder Woman that cast female leads in action movies. Nonetheless, we isolate the critical role that males in action films play in the observed gender earnings differences.

We present a more nuanced view of ageing than previous studies. First, the action genre has a huge gender differential but shows no age pattern. Second, outside the action genre, the gender gap is concentrated among older workers (above age 50) and there is no wage gap for younger stars. We uniquely find that the gender earnings gap does not change with experience in the early part of the career. Thus, we find no evidence of the differential investment in training and specific human capital that has been suggested elsewhere. It seems clear that old age per se hurts the earnings of female actors. Again, while we present a more nuanced view, we cannot determine whether the age penalty reflects customer preference, persistent ignorance by, or prejudice by, producers, studios and writers.

3 Data and descriptive statistics

The data on Hollywood stars over the period from 1980 to 2015 come from two main sources. The biography section of the internet movie database (IMDb) (www.imdb.com) provides star earnings for a given movie which we deflate by the annual consumer price index. These earnings are not crowdsourced. IMDb only lists earnings they can independently verify. Our sample consists of every star by movie observation for which earnings are available. Thus, we make no selection among the data and rely on IMDb to identify stars and their earnings. While we take every observation, IMDb clearly focuses on “Major” stars. Indeed, the three lowest earnings by film in the data are for well-known stars Ben Affleck, Madonna and Brad Pitt. Consequently, we share with previous studies the inability to guarantee a representative sample and, indeed, we are unsure of the ways in which the sample is selected. While the star needed to be major, IMDb made clear that even within these stars some contracts are not verifiable.

We have 1344 star by movie observations on a total of 267 different stars. Also available are the actor’s gender, birth year, ethnicity, nationality and Oscar awards and nominations. Including the latter two variables as determinants of earnings has been routine as they are considered measures of talent but has met with mixed results (see Deuchart et al., 2005; Gumbel et al., 1998; Nelson et al., 2011).

In addition to the fixed compensation received by the star there exists very imperfect information on variable compensation. We know that only 6.2% of contracts in the data list the presence of variable compensation. Yet, it is one thing to observe the contract clause but another to convert it into earnings (Caves, 2003; Epstein, 2012). Profitability often remains still outstanding after long periods and is often legally disputed. Moreover, merchandising and tie-in revenue is typically not observable to outsiders. Knowing film revenue, the only variable pay that can be estimated is the subset related to revenue. Thus, we focus on the fixed compensation.Footnote 6

The second major data source, Box Office Mojo (www.boxofficemojo.com), provides detailed information on release dates, the studio, box-office revenues, total number of theatres, genre classification, MPAA rating and distributor. It also provides labour market experience in its “People/Actors” section and production budget data in its “Movie” section. This second source covers more movies and actors, and its data are matched to those for whom earnings data are available from IMDb. It allows us to develop movie-specific measures of the extent to which female stars dominate a movie. Following Aguiar (2023) these include the share of the three leading actors that are female.

To further capture the preferences of audiences for stars, we develop two variables. First, we identify the rank order of credit listing. This is movie-specific and typically (but not always) identifies stars in order of perceived importance. It varies by movie and actor so fits the structure of our data and is available for all films. Yet, it is an imperfect measure both because sometimes rank order can simply reflect the order of appearance and because it also reflects the judgement of the studios and producers. This is problematic if their preferences are not the same as fans because of either ignorance or prejudice. In this sense, the rank order could reflect the discrimination that one hopes to measure.

Second, we use an available index of star popularity, STARmeter. This proprietary algorithm ranks thousands of actors based on the 200 million monthly users of IMDb. It reflects the overall “visits and hits” generated by users with a rank of 1 being the most popular star. STARmeter rankings are taken as of the release of a movie so it varies by both star and movie. This has the advantage over mentions in People or similar publications (see Treme 2010; Treme & Craig, 2013) in that it reflects individual fan volition rather than editorial choice. We note that neither measure captures the pre-movie “buzz” about the star which has been identified as contributing to box-office revenues (Karniouchina, 2011). Such buzz is hard to measure but is defined as “the amplification of initial marketing efforts by third parties through their passive or active influence” (Thomas, 2004). Forwarding messages on social media would, for example, contribute to a star’s pre-movie buzz.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and definitions. The observations are 36% female, 79% US citizens and 88% White.Footnote 7 The average STARmeter ranking is 160, and the average star in our sample of movies is ranked approximately 3rd in the credits.

Table 1 shows that the big six studios (Buena Vista, Twentieth Century Fox, Universal, Warner Brothers, Paramount and Sony-Columbia) account for 70% of the observations. These vertically integrated studios (both studio and distributor) are presumed to be more successful on average with high-risk products with high production costs and uncertain success (Grossman & Hart, 1986; Kranton & Minehart, 2000). This success may be translated into higher earnings. We further use this variable in conjunction with the production budget of the movie. We identify movies that are both in the bottom third of our distribution of budgets and which are not from one of the six major studios. We suggest these movies as more likely to be an “independent movie” and use this as an additional control. The most common genre is action, comprising 22% of the total. The increasing importance to the box office of car crashes, special effects, superheroes and action is driven by the domination of teenagers who now comprise fully 80% of all moviegoers.Footnote 8

Figure 1 presents male and female average real earnings per film from 1980 to 2015. While earnings have been increasing, a substantial earnings gap persists over time. The persistence of the Hollywood gender gap seems at odds with economy-wide measures which show it shrinking rapidly in the 1980s and then continuing to shrink but much more slowly. (Altonji and Blank, 1999; Blau & Kahn, 2006, 2017). The fact that our single profession doesn’t show a substantial decline may fits the view that much of the economy-wide narrowing reflects women moving into higher paying professions rather than from shrinking differentials within those professions. (An early expression of this is in Johnson & Solon, 1985 and more recently in Courey & Heywood, 2018.)

Figure 2a presents the density functions of male and female real earnings per film. The resulting wage distributions indicate large differences in earnings between Hollywood superstars.Footnote 9 At the same time, the female wage density function lies to the left showing an obvious gender wage gap in the raw data. Moreover, tests show that the distribution of wages for women is less dispersed and has less skewness.

The pattern in Fig. 2a suggests a long right-hand side tail (especially for males) often used to justify the log-linear earnings specification. Figure 2b presents the density function of male and female real log earnings. Here a long left-hand side tale emerges (especially for females). The well-known Box–Cox test (Box & Cox, 1964) rejects both the log-linear and linear specifications at the 5% level for any of our preferred specifications. Examinations of residuals against the inverse normal suggest the linear specification does modestly better throughout the heart of the distribution and much better at lower earnings levels. Thus, our initial estimates will be with earnings, but we will demonstrate that our central findings remain in log-linear estimates.

Table 2 presents summary statistics by gender. The average movie earnings (in millions of 2015 dollars) is 11.50 for male and 6.45 for female stars, resulting in unadjusted average wage gap of 5.06 million and a female to male wage ratio of only 56%. Additional variable compensation is indicated in 7.8% of male star contracts but only 3.3% of female star contracts.

The male stars are 7 years older but have only 4 more years of experience suggesting that the female stars started their career at a younger age. The female observations are associated with movies having lower total revenues and lower production budgets although the standard errors are so huge that this is only suggestive. Similarly, women are less likely to be associated with a big 6 distributor or be in a sequel. They are significantly more likely to appear in an “independent movie”. Females rank slightly lower in credits and have a lower (further from 1) STARmeter ranking (although not significantly). Of importance for potential segregation within the occupation, male stars are twice as likely as female stars to be in an action film. This will be a focus in our estimations.

4 Empirical estimates

In this section, we estimate the determinants of star earnings. We start by estimating the following standard earnings equation by OLS:

where \({w}_{ijt}\) is the dependent variable representing star i’s earnings for film j in period t. The vector \({X}_{it}\) contains stars’ characteristics in time t such as age, nationality, ethnicity and acting experience. This vector also captures stars’ previous success including the number of Oscar awards, the accumulated revenues that all movies he/she has acted in up to t and our two measures of star popularity. The critical variable for our examination is gender coded 1 if female. \({Y}_{jt}\) is a vector of film characteristics including the genre, distributor, whether the movie is a sequel, the MPAA rating, box-office revenues, number of screens projected and the production budget. Finally, \({\varepsilon }_{ijt}\) is the error term. Standard errors are clustered at the star level.

Column 1 of Table 3 controls for basic individual star earnings determinants. The typical quadratic relationships for both age and experience emerge. The earnings for a given star movie increases with the age and experience of the star but at a decreasing rate. This fits most earnings regressions but given the controversy over gender differences in the role of age, we will return to this later. The estimates also suggest that Asians and other races earn less while there is no difference between black and white earnings. Critically, the gender wage gap drops to $3.47 million (from 5.06 million) by adding these simple controls. Column 2 adds both the indicators of Oscar awards and a long series of movie characteristics. Here, neither the Oscar awards nor the ratings significantly influence earnings, but the genre, distributor and sequel variables all emerge as important. Actors earn more from a movie when it is an action film, when it is sponsored by one of the big six studios and when it is a sequel. Including these variables causes a further decline in the unexplained gender differential but it remains $3.20 million.

Column 3 adds the accumulated box-office revenues of the stars’ previous films as well as the box-office revenues and the number of theatres of the current film. Both the number of theatres (highly correlated with the film’s box-office revenues) and the accumulated box-office revenues are important positive statistical determinants of actor earnings.Footnote 10 Their inclusion also weakly suggests the importance of a leading role Oscar and provides some support for PG 13 as a sweet spot in the rating system. The gender earnings differential declines to $2.22 million dollars.

Column 4 adds the production budget of the movie (which brings a reduction in sample size), whether the movie was an “independent movie”, the box-office revenues of the stars’ last movie (that just prior to the one being observed) and a dummy variable indicating female actors are in at least 2 of the 3 most prominent roles.Footnote 11 Neither the budget nor having two-thirds or more female leads play a significant role. The box-office receipts of the star’s previous movie takes a positive coefficient and those that act in an independent movie (low budget and not from a major studio) earn an enormous 5 million dollars less all else equal.Footnote 12 The gender gap remains a highly significant 2.40 million dollars.

Column 5 adds our measures of star popularity. This comes with a further reduction in sample size as the STARmeter measure was not available prior to 1998. A lower rank order predicts significantly lower earnings. A lower STARmeter rank (farther from 1) predicts lower earnings, but the coefficient is not statistically significant. Critically, while the variables behave as predicted, they have a modest influence on the gender gap which continues to remain 2.07 million dollars.

To examine whether earnings differ between genders conditional on the same movie, we allow for movie-specific fixed effects. This controls for sorting across movies by gender. Unmeasured characteristics such as filming schedules and location, or specific directors may result in female stars sorting or being sorted into a given film. If these unmeasured characteristics are constant across genders, their influence can be removed with fixed effects:

The estimated gender earnings gap in (2) comes from comparing male and female stars within the same movie. As a result, all controls measured at the film level drop out.

The fixed effect estimate based on the specification in column 4 is shown in column 6 of Table 3. The gender differential is modestly larger (3.11 million vs. 2.40 million).Footnote 13 In an analogous fixed effect estimate to column 3, the gender differential is again larger (2.68 million vs. 2.22 million). This suggests that sorting results in an underestimate. One interpretation is that women work to sort into inherently better paying movies and that when this sorting is eliminated, greater differentials are evident.

These estimates of the gender wage gap fall within the range of estimates reported by for other narrower and highly paid labour markets. Courey & Heywood (2018) find an unexplained gender wage differential of approximately 20% for software workers. Similarly, Reyes (2007) and Bashaw and Heywood (2001) find that women physicians earn around 20% less than their otherwise similar male counterparts. Bertrand and Hallock (2001) find that women business executives earn from 11 to 34% less than men, whereas Bell (2005) estimates differences in earnings that range between 8 and 25%. Wood et al. (1993) find a 13.2% advantage for young male lawyers over women lawyers with similar career and family situations. Kahn (1991) studies tennis players finding an 11% earnings premium for men in Wimbledon and 26% in the French Open.Footnote 14

We attempted to further explain the gender differential by the characteristics of the producer. We separately added whether there was a female producer and the share of female producers. In each case, we also added an interaction with the gender of the star. We could not identify a statistically significant difference for either interaction (see Online Appendix Table 1). Male and female producers do not appear to generate different earnings by gender for stars.

4.1 The role of movie genre

We now focus on the role of movie genre. In a typical Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition, we found that returns to movie genre provided the largest portion of the unexplained gap.Footnote 15 This convinced us to estimate earnings differentials within genre groups.

While some definitions of genre groups focus on the shared characteristics of the customers and others combine similar “styles” (Redfern, 2012), we simply divide out genres associated with action, violence, power and adventure. These remain stereotypically thought of as more male attributes when portraying movie heroes (see Miller et al., 2016). Thus, we combine action, adventure and thriller movies in a broad group that we simply label action movies. The remaining half-dozen genres we identify as other movies. The group of action movies comprise about 3/8th of our sample.

Within each broad group of movies (action and other), we repeat our specifications from Columns 3 and 4 of Table 3. Recall that those estimates suggested an unexplained gender gap of 2.2 and 2.4 million dollars per film. The first two columns of Table 4 show the results dividing the sample by genre groups. The gap within the action films indicates a gap of 3.4 and 3.7 million dollars. The gap in other films falls to only 1.6 million in the shorter specification and insignificantly different from zero in the longer specification.

The second two columns of Table 4 reproduce by genre group the movie fixed effect estimates associated with the same two specifications. In the original full-sample results, the fixed effect estimates emerged as modestly larger than those without fixed effects. Here we see that was driven by offsetting influences. The fixed effect estimates of the gap are dramatically larger among action movies, now indicating 5.5 and 7.5 million dollars. The fixed effect estimates of the gap remain small among other movies and are never statistically different from zero. We emphasize that column 4 shows a gap among action movies of 7.5 million, almost six times larger than that among other movies of 1.3 million (although insignificantly different from zero). In action films, a huge differential emerges that appears to drive the overall differential in the industry.Footnote 16

Note that including the STARmeter measure and rank order does not change this conclusion. For example, in the fixed effect in the last column of Online Appendix Table 4, the differential in action films remains a highly significant 7.6 million and that in other genres is only 573 thousand dollars and not statically significant. We also note that the difference between genres remains in log earnings estimates in Table 6 in the Online Appendix. Even as the visual tests suggest that earnings may fit better than log earnings (especially for the other genres), the Box–Cox test rejects both specifications. In the OLS estimates, none of the gender gaps in other genre films is statistically different from zero even as large percentage gaps appear routinely in action films.

It might be argued that our emphasis on genre is misplaced. Male stars may be more productive and disproportionately select into action films. They could be disproportionately “adrenaline addicts” and we would miss an important source of endogeneity. As a test for this, we changed the nature of our fixed effect estimate. Nearly half our stars appear in both an action and non-action genre. We leverage this to replace film fixed effects with actor fixed effects. Thus, we watch as a given actor moves between genres holding the time invariant actor characteristics constant. We summarize the results in Table 5 noting that all actor-specific characteristics necessary drop out of the estimations. In the first column the action films pay over a million and a half dollars more on average. Yet, this hides exactly the pattern shown by our earlier results as revealed in the second column. Action genre films pay men significantly more, but the interaction of female and action films is very large and negative. Thus, men earn more in action films while women do not.

5 Dynamics of the gender earnings gap for stars

We now conduct dynamic analyses of the gender wage gap to determine the growth of the gender wage gap first with stars’ age and then with their years of experience. Following Bertrand et al. (2010), we estimate the following regression using age as an example:

where \(({F}_{i}\times A)\) represents the interaction between the dummy variable Female and a series of age dummies corresponding to age ranges for star i when acting in film j in period t. Apart from these interactions replacing the single female dummy, the specifications will be identical to those in Table 3.

Several caveats are in order. First, stars of either gender with poor skills will likely be removed from the market, and so, we observe a selected sample of older male and female stars who remain highly skilled and in demand. Second, we simply will not observe many of the stars throughout their full career. Thus, the results we present must be taken with the usual strong caution about cohort differences often confounding true age differences. The pattern in today’s older workers need not be replicated when today’s younger workers become old. No feasible expansion of our data allows us to avoid this problem and the resulting caution. Nonetheless, our longer time window of data and multiple observations for most stars provides the best data for this inquiry to date.

Table 6 shows the relevant results from Eq. (3). The top panel focuses on age and the bottom panel focuses on experience. In each panel, the first three columns show the action genre, and the next three columns show all other genres. The first column shows the results including only a constant, a series of annual year dummies and the interactions. The next two columns are our preferred specifications (3) and (4) that we have been focusing on and that add the controls. The first columns suggest an inverse u-shaped pattern in which the gender differential is largest in the early and later ages. This attenuates as the controls are added.

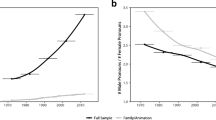

The top panel shows a large difference in the role of age between action and other genres. Most importantly, there are so few action stars in the older age groups that a differential can simply not be measured in the more complete specifications. Second, the familiar pattern emerges in which the differential within the action genre is far larger than that in the other genres for the age groups in which both can be measured. These points are shown visually in the top two diagrams of Fig. 3 which presents the differentials for the most complete specification. Another major point evident in Fig. 3 is that within the age groups in which the action genre differential can be estimated there is not a pattern of growth or decline. Yet, for the other genres a clearer pattern is evident. The gender differential in earnings grows substantially in the oldest categories. Indeed, it is essentially insignificantly different from zero until age 50. In the two age categories above age 50 it is very large and significantly different from zero. Thus, a substantial gender earnings differential exists in virtually all action movies but only among older actors in other movies.

Presentation of the gender earnings difference in millions of dollars from dynamic analyses of age and experience. Note: These plot the four estimates of the gender earnings differential from specification (4) as presented in Table 5

The lower panel of Table 6 carries out a very similar analysis using years of experience (years since first movie appearance). We return to (4) and replace age bands with ten experience dummies capturing each year of experience one to 9 and then 10 or more. These are interacted with the female dummy. Again, we show the simple specification and the two most complete specifications all divided by movie genre.

The action movies again show a large differential. As is clear from Fig. 3, there is also no clear pattern to it as experience increases. It is perhaps smaller with very few years of experience but quickly seems to settle into estimates that are typically three million dollars or more. Interestingly, there is also no clear pattern among the other genres. If anything, the gender differential is nearly absent later in the experience categories, as shown in Fig. 3. None of the gender differentials in the last five experience categories approaches statistical significance, and several of the associated point estimates are very close to zero.

The larger gaps that emerge later in careers for women workers in other highly paid professions have been said to reflect unobserved gender differences in specialization, labour force attachment and effort. As we have argued, such gender differences are far less relevant among movie stars, and this may explain the different pattern we present. More importantly, our finding on experience strongly undercuts the argument that these specialization or attachment issues drive our age finding. Increased experience helps close the gap for the women of Hollywood but with old age, the gap expands regardless of experience.Footnote 17

6 Conclusions

This paper compiles an original dataset on 267 Hollywood stars and 1344 movies from 1980 to 2015 to study gender earnings differences. We argue that Hollywood provides a window on a market of superstars in which women have long had substantial representation and do remarkably similar work. We focus on the gender earnings gap not on the marginal box-office contribution of individual movie stars (Elberse, 2007) although this remains an area for future research.

We show that female stars have an unexplained earning gap of more than 2 million dollars per movie on average. The many determinants of earnings can explain about half of this difference in either an OLS or a movie fixed effects methodology. We control for measures of actor success (past box-office receipts) and popularity (STARmeter and rank order). The unexplained gender differential per movie is large and retains statistical significance in a very wide variety of robustness exercises. We identify that this gender differential is disproportionately driven by extremely large differentials in action movies. The differential is far less evident and often absent for other genres. Within those other genres it is particularly evident among older stars (50 and over) and otherwise absent or small.

We remain circumspect about the cause of the gender earnings gap but emphasize that the two areas where it exists could reflect social and public preferences. The movie going public may associate action, strength, violence and anger disproportionately with males. Beauty is associated with earnings, a finding especially true for women. This could be especially true in the visual medium of film and drive the gender differential among older workers in other genres. Yet, we clearly have not confirmed any causal link between consumer preference and the gender gap among stars. We have not, for example, ruled out that the huge differential in action films reflects the ignorance or prejudice of producers, studios and writers. Consequently, we argue that scrutiny and potential policy should be directed towards action films.

We end with the suggestion that economists seem poorly equipped to make strong welfare judgements about consumer discrimination. On the one hand, if the utility that consumers receive is enhanced by the gender of an actor, this suggests that gender, itself, is a source of productivity that should be rewarded. On the other hand, a shared conception of fairness could easily argue that the material welfare of actors of different genders should not vary based on this utility.

Data availability

The dataset generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Change history

26 July 2024

This article has been updated for the change in family name as “Izquierdo Sanchez” for the author “Sofia Izquierdo Sanchez”.

Notes

The latter includes estimated differentials for top tennis players (Kahn, 1991), physicians (Reyes, 2007; Baker, 1996; Esteves-Sorenson & Snyder, 2012; Bashaw & Heywood, 2001), academics (Blackaby et al., 2002; Gordon et al., 1974; Johnson & Stafford, 1974), lawyers (Noonan et al., 2005; Wood et al., 1993), business executives (Bell, 2005; Bertrand & Hallock,2001; Bertrand et al., 2010), accountants and auditors (Schaefer & Zimmer, 1995) and software developers (Courey & Heywood, 2018).

See McKenzie, (2023) for a recent review of the economics of movies.

This assumed importance of fan popularity has been confirmed in men’s professional soccer where popularity rather than productivity on the field explains superstar wage effects (See Scarfe et al., 2021).

The available data do make clear that female stars are less likely to receive variable compensation.

We note that 38% of the stars are female even as they represent 36% of the movie by star observations.

Teenage audiences are the easiest to engage through TV advertising, merchandising and tie-ins with fast food restaurants and toy companies. Teenagers also avidly consume soft drinks, snack foods and popcorn, the main sources of profits for movie theatres.

The best paid star in our sample, Tom Cruise, received 88 million dollars in nominal terms in 2015 for Mission Impossible III.

Indeed Moretti (2011) makes clear that those movies predicted to be successful films will be shown in a higher number of screens.

Following Aguiar, we also experimented with a cut off of 1/3 of the top three were women and if the lead was a woman. The results were roughly comparable.

We note that women may be “crowded” into independent movies or may disproportionately choose such movies.

Rho (ρ) measures the fraction of error term variance attributable to the fixed effects. Thus, after controlling for the independent variables, there remain observed differences in earnings and about three-fifths of this difference occurs between films and 2/5ths within movies.

Schaefer & Zimmer, (1995) however find that unexplained differences for accountants and auditors are not statistically significant.

The pattern of these results are robust to omitting superhero films. Removing the 57 superhero films continues to show a large gender differential in the remaining action films. The gender coefficient is large within the superhero only group but is not significant, likely due to small sample size.

Examining only workers with 10 or more years of experience emphasizes this point. There are insufficient observations to estimate our specification (4) in the action genre for those 50 and above. Yet, throughout the remaining age range the differential is typically large and significant. In other genres, the gender differential for those below 50 often remains statistically insignificant and small but for those 50 or above the differential remains large and statistically significant. These estimates are in Online Appendix Table 5.

References

Addis, M., & Hobrook, M. B. (2010). Consumers’ identification and beyond: Attraction, reverence and escapism in the evaluation of Films. Psychology and Marketing, 27, 821–845.

Adler, M. (1985). Stardom and talent. American Economic Review, 75, 208–212.

Aguiar, L. (2023, May 31). Critics, Crowds, and the gender gap in product ratings: Evidence from movies, working paper, Department of Business Administration. University of Zurich.

Altonji, J. G. & Rebecca, M. B. (1999). Race and gender in the labor market. In Ashtenfelter, O. & Card, D. (eds.), Handbook of labor economics, Vol 3A.

Arrow, K. J. (1973). The theory of discrimination, discrimination in labour markets. Princeton University Press.

Babcock, L., & Laschever, S. (2003). Women don’t ask. Princeton University Press.

Baker, L. C. (1996). Differences in earnings between male and female physicians. New England Journal of Medicine, 331, 960–964.

Bashaw, D. J., & Heywood, J. S. (2001). The gender earnings gap for US physicians: Has equality been achieved? Labour, 15(3), 371–391.

Bell, L. A. (2005). Women-Led firms and the gender gap in top executive jobs. Institute for the study of labor, Discussion paper 1689.

Bertrand, M. (2011). New perspectives on gender. In O. Ashenfelter & D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 4B, pp. 1545–1592). Elsevier.

Bertrand, M., Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2010). Dynamics of the gender gap for young professionals in the financial and corporate sectors. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2, 228–255.

Bertrand, M., & Hallock, K. F. (2001). The gender gap in top corporate jobs. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 55(1), 3–21.

Biddle, J. E., & Hamermesh, D. S. (1998). Beauty, productivity, and discrimination: Lawyers’ looks and lucre. Journal of Labor Economics, 16(1), 172–201.

Bielby, D. D., & BIelby, W. T. (1996). Women and men in the film: Gender inequality among writers in a culture industry. Gender and Society, 10(3), 248.

Blackaby, D., Booth, A. L., & Frank, J. (2002). Outside Offers and the Gender Pay Gap: Empirical Evidence from the UK, Working Paper

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2006). The U.S. gender pay gap in the 1990s: Slowing convergence. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 60(1), 45–66.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2017). The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3), 789–865.

Bolan, P., & Williams, L. (2008). The role of image in service promotion: Focusing on the influence of film on consumer choice within tourism. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 32(4), 382–390.

Box, G. E. P., & Cox, D. R. (1964). An analysis of transformations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 26, 211–243.

Cantor, R. L. (1999) Consumer preferences for sex and title VII: Employing market definition analysis for evaluating BFOQ defences. University of Chicago Legal Forum, Issue 1, Article 12.

Card, D., Raute Cardoso, A., & Klein, P. (2016). Bargaining, sorting, and the gender wage gap: Quantifying the impact of firms on the relative pay of women. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(2), 633–686.

Caves, R. E. (2003). Contracts between art and commerce. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(2), 73–84.

Chong, C., & Berger, R. (2010). Ethics of celebrities and their increasing influence in 21st century society. Journal of Business Ethics, 91(3), 313–318.

Courey, G., & Heywood, J. S. (2018). Gender wage gap trends among information science workers. Social Science Quarterly, 99, 1805–1820.

Croson, R., & Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 47, 1–27.

De Pater, I. E., Judge, T. A., & Scott, B. A. (2014). Age gender and compensation: A study of Hollywood movie stars. Journal of Management Inquiry, 23, 407–420.

Deuchart, E., Adjamah, K., & Pauly, F. (2005). For Oscar glory or Oscar money? Journal of Cultural Economics, 29, 159–176.

De Vany, A. (2004). Hollywood economics: How extreme uncertainty shapes the film industry. Routledge.

Elberse, A. (2007). The power of stars: Do star actors drive the success of movies? Journal of Marketing, 71, 102–120.

Epstein, E. J. (2012). The Hollywood economist 2.0: The hidden financial reality behind the movies. Melville House.

Esteves-Sorenson, C., & Snyder, J. (2012). The gender earnings gap for physicians and its increase over time. Economics Letters, 116(1), 37–41.

Fleck, R. K., & Hanssen, A. (2016). Persistence and change in age specific gender gaps: Hollywood actors from the silent era onward. International Review of Law and Economics, 48, 36–49.

Franck, E., & Nüesch, S. (2012). Talent and/or popularity: What does it to take to be a superstar? Economic Inquiry, 50, 202–216.

Gilberg, M., & Hines, T. (2000). Male entertainment award winners and older than female winners. Psychological Reports, 86(1), 175.

Ginsburgh, V., & Van Ours, J. C. (2007). On organizing a sequential auction: Results from a natural experiment by Christie’s. Oxford Economic Papers, Oxford University Press, 59(1), 1–15.

Gordon, N. M., Morton, T. E., & Braden, I. C. (1974). Is there discrimination by sex, race, and discipline? American Economic Review, 64(3), 419–427.

Grossman, S. J., & Hart, O. (1986). The costs and benefits of ownership: A theory of vertical and lateral integration. Journal of Political Economy, 94(2), 691–719.

Gumbel, P., Lippman, J., Bannou, L., & Orwall, B. (1998). What’s an Oscar Worth? Wall Street Journal. 1.

Hamermesh, D. S., & Biddle, J. E. (1994). Beauty and the labour market. American Economic Review, 8(5), 1174–1194.

Hamlen, J. R., & William, A. (1994). Variety and superstardom in popular music. Economic Inquiry, 32(3), 395–406.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Houston, M. B., & Sridhar, S. (2006). Can good marketing carry a bad product? evidence from the motion picture industry. Marketing Letters, 17, 205–219.

Hofmann, J., Clement, M., Vockner, F., & Henning-Thurau, T. (2017). Empirical generalization on the impact of stars on the economic success of movies. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 34, 442–661.

Hofmann, K. H., & Optiz, C. (2019). Talent and publicity as determinants of superstar incomes: Empirical evidence from the motion picture industry. Applied Economics, 51, 1393–1395.

Johnson, G. E., & Solon, G. (1985). Estimates of the direct effects of comparable worth policy. American Economic Review, 76, 1117–1265.

Johnson, G. E., & Stafford, F. P. (1974). The earnings and promotion of women faculty. American Economic Review, 64(6), 888–903.

Karniouchina, E. V. (2011). Impact of star and movie buzz on motion picture distribution and box office revenue. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 28, 62–74.

Kahn, L. M. (1991). Discrimination in professional sports: A survey of the literature. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 44(3), 395–418.

Kranton, R. E., & Minehart, D. F. (2000). Networks versus vertical integration. The RAND Journal of Economics, 1(3), 570–601.

Krueger, A. B. (2005). The economics of real superstars: The market for rock concerts in the material world. Journal of Labour Economics, 23(1), 1–30.

Lincoln, A. E., & Allen, M. P. (2004). Double jeopardy in Hollywood: Age and gender in the careers of film actors, 1926–1999. Sociological Forum, 19, 611–631.

Linder, A. M., Lindquist, M., & Arnold, J. (2015). Million dollar maybe? The effect of female presence in movies on box office returns. Sociological Inquiry, 85(3), 407–428.

Lucifora, C., & Simmons, R. (2003). Superstar effects in sport: Evidence from Italian soccer. Journal of Sport Economics, 4(1), 35–55.

McKenzie, J. (2023). The economics of movies (revisited): A survey of recent literature. Journal of Economic Surveys, 37, 480–525.

Miller, M., Rauch, J., & Kaplan, T. (2016, November). Gender differences in movie superheroes Roles, appearances, and violence. Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology (10). https://doi.org/10.7264/N3HX19ZK

Morgan, R. (2017, September 26). How talent agents get paid. BizFluent: https://bizfluent.com/info-7743202-talent-agents-paid.html

Moretti, E. (2011). Social learning and peer effects in consumption: Evidence from movie sales. Review of Economic Studies, 78, 356–393.

National Endowment for the Arts and the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (2012). Data access via US Bureau Data of Economic Analysis portal: https://www.bea.gov/index.php/data

Nelson, R. A., & Glotfelty, R. (2012). Movie stars and box office revenues: An empirical analysis. Journal of Cultural Economics, 36, 141–161.

Nelson, R. A., Michael, R. D., Waldman, D. M., & Calbraith, W. (2011). What’s an Oscar worth? Economic Inquiry, 39(1), 1–16.

Noonan, M. C., Corcoran, M. E., & Courant, P. N. (2005). Pay differences among the highly trained: Cohort differences in the sex gap in lawyer’s earnings. Social Forces, 84(2), 853–872.

Olivetti, C. & Petrongolo, B. (2016). The evolution of gender gaps in industrialized countries. Working paper: https://www.nber.org/papers/w21887

Oxford Economics. (September, 2012). The economic impact of the UK film industry. Report supported by the BFI, Pinewood Shepperton plc, British film commission and creative England.

Redfern, N. (2012). Correspondence analysis of genre preferences in the UK film audiences. Journal of Audience and Reception Studies, 9, 45–55.

Reyes, J. W. (2007). Reaching Equilibrium in the market for obstetricians and gynecologists. American Economic Review, 97(2), 407–411.

Rosen, S. (1981). The economics of superstars. American Economic Review, 71, 845–858.

Scarfe, R., Singleton, C., & Telemo, P. (2021). Extreme wages, performance, and superstars in a market for footballers. Industrial Relations. https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12270

Schaefer, J., & Zimmer, M. (1995). Gender and earnings of certain accountants and auditors: A comparative study of industries and regions. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 14, 265–291.

Stuchlmacher, A., & Walters, A. (2006). Gender differences in negotiation outcome: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 52, 653–677.

Suarez Vazquez, A. (2011). Critic power or star power? The influence of hallmarks of quality of motion pictures: An experimental approach. Journal of Cultural Economics, 35(2), 119–135.

Terviö, M. (2009). Superstars and mediocrities: Market failure in the discovery of talent. Review of Economic Studies, 76, 829–850.

Thomas, G. M. (2004). Building the buzz in the hive mind. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 4, 64–72.

Treme, J. (2010). Effects of celebrity media exposure on box-office performance. Journal of Media Economics, 23, 5–16.

Treme, J., & Craig, L. A. (2013). Celebrity star power: Do age and gender effects influence box office performance. Applied Economics Letters, 20, 440–445.

Treme, J., Craig, L. A., & Copland, A. (2018). Gender and box office performance. Applied Economics Letters. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2018.1495818

Vanity Fair (2016). Oscar-winning actress says she was offered 1/20 of Male co-star’s pay. URL: https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2016/10/oscar-winner-gender-wage-gap

Wood, R. G., Corcoran, M. E., & Courant, P. N. (1993). Pay differences among the highly paid: The male-female earnings gap in lawyers’ salaries. Journal of Labor Economics, 11(3), 417–441.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Rhys Wheeler, Colin Green, Jean-Francois Maystadt, Blaise Melly, Robert Rothschild, Ian Walker, James Banks, Rachel Griffith and seminar participants at the University of Padova, Lancaster University, the University of Huddersfield and the WPEG conference for helpful comments.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception, design, data collection, analysis and writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been updated for the change in family name as “Izquierdo Sanchez” for the author “Sofia Izquierdo sanchez”.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heywood, J.S., Izquierdo Sanchez, S. & Paniagua, M.N. The Hollywood gender gap: the role of action films. J Cult Econ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-024-09514-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-024-09514-0