Abstract

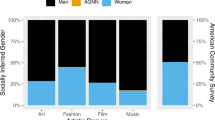

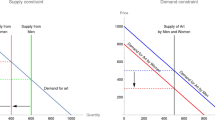

From the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, the Paris Salon was the leading visual arts exhibition venue in France—and arguably in all of Europe. For an artist, having a painting admitted to the Salon was a good signal; obtaining one of the competitive medals systematically awarded at the exhibition often marked the start of a successful career. Based on two unique datasets, this paper quantitatively analyzes which elements drove the likelihood of winning a medal. The juried Salon system has often been criticized for being prejudiced. Our paper shows the changes in the way the jury acted as rules and regulations varied over time, adding a dynamic dimension to our analysis. We find that nepotism, proxied here as having one’s master sit on the jury, helped win medals, but this was not systematically the case. The hierarchy of genres setting history paintings at the top was not always respected. By contrast, women were systematically discriminated against. Medals were more likely to be awarded to men, even for the minor genres, in which many women were forced to specialize.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The Académie des beaux-arts was founded in 1816 as the heir of the royal academies of the same name. It acted as the guardian of a particular artistic tradition and was an influential venue for artistic training. It also played a role in guiding contemporary artistic production.

The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture was an artistic institution that regulated and taught painting and sculpture under the Ancien Régime. It benefited from royal patronage and sought to emancipate itself from the rigidity of guilds and the status of associated artisans.

The Institut de France was created in 1795 to unite the scientific, literary, and artistic elite. Divided into classes, it more or less took over the organization and ambitions of the former royal academies, which were abolished during the Revolution.

This was also to compensate artists for the disappearance of their privileged clientele in the Revolution, namely the aristocracy, the Church, and the financiers of the Ancien Régime.

Medals to encourage young artists existed earlier but were not linked to the Salon; see Cahen (1993).

The value associated with each medal, specified in the regulations, represented the production value of the “medal” received by the laureates. The symbolic object, adorned with allegories or a portrait of Napoleon III, was produced by the Paris mint and involved significant expenditure on the part of the fine arts administration. Artists could also sell these medals for their material and use the proceeds of the sale to live and produce.

The index is publicly available online, https://github.com/dsg2123/Painting-by-Numbers/tree/main/Data/Whiteley%20Index.

At each exhibition, artists registered their works with the administration to compile the catalog, and each piece was given a unique number, the registration number, to identify it.

Unfortunately, we cannot control for artistic movements. Furthermore, since our databases do not contain any images, we would have had to focus only on the most famous artists, which would have reduced the sample substantially and introduced a bias. Nevertheless, it is impressive to see the number of artists in our sample who did not pass the test of time.

For 1260 works of art, the Whiteley Index provided no information. Their genre could thus not be determined.

An artist is declared hors-concours at a given Salon, i.e., they can no longer claim any additional medals except the medal of honor. This variable was created based on the Informations biographiques field in the catalog and through the successive rules establishing this status.

They could win a very rarely awarded Médaille d'Honneur, but there were only thirteen such medals awarded in the whole sample.

Her career was interrupted by her marriage in 1881 to Edouard André (1833–1894): she abandoned the artistic profession and devoted herself to building up her collection.

“M. Pierre Cabanel, the nephew of the member of the Institute, has just sent to the Salon a superb tile representing the Flight of Nero. This painting is very remarkable and will be one of the successes of the Salon.” (Anonymous 1873).

“The flight of Nero, by M. Pierre Cabanel, nephew of the famous member of the Institute, is indeed a historical painting. It is the work of a young man who reveals qualities of great painting; the composition is good as a style and character, and it is well ordered; the fearful Caesar, crawling near a pond and carrying a little fetid water to his lips, is of a well-felt expression; the freedman who is on the lookout is of a beautiful tone and a masterly aspect. The stormy background of the windy landscape adds the right note and gives expression to the subject; everyone is well in the drama, which lacks neither scope nor truth. We cannot encourage too much the young artists who dedicate themselves to the great historical art so abandoned nowadays; Pierre Cabanel has all that is necessary to succeed in this and the example of his uncle can only be a stimulus and an encouragement in this way.” (Rozier 1873).

“Here is a great painting, even less good; it is true than that of M. Barrias but of the same school. The Flight of Nero, by M. Pierre Cabanel, shows us, according to Suetonius, the master of the world, crouching, tired, livid, frightened, drawing water from a pond in his hand to quench his thirst. It is bold to tackle such a subject, and I would like to find something pleasant and encouraging to say to the young painter. I am a little embarrassed; I do not recognize the landscape described by Suetonius; the figures which populate the canvas lack proportion; they pose with an emphasis that borders on the ridiculous, and their arms, legs, and heads have those movements which only articulated mannequins can execute. There is no relationship between the planes of the painting; everywhere there is a violation, shocking to the eye, of the laws of perspective, and… but these are not praises, I will shut up and pass on." (Biart 1873a).

“But why encourage Mr. Pierre Cabanel? Is it because he has translated Suetonius badly! Great painting has the right to all respects, that's fine; however, good painting also has some rights not to be despised.” (Biart 1873b).

)“Decidedly, it is a bias to reward ancient and Roman subjects, classical attempts. Apart from this goodwill, I am looking in vain for what could have motivated the award in favor of the heavy and naive composition of Mr. Pierre Cabanel. (Guillemot 1873).

“M. Pierre Cabanel treated the Flight of Nero. […] We had seen this attempt at composition and we had kept quiet; we were probably wrong since the jury awarded him a third medal." (Lora 1873).

“M. Pierre Cabanel has for him the name of his uncle. His Flight of Nero, in which the hunted emperor seems to have descended from large wooden or cardboard horses, is a large academic painting without life, without an accent. […] [T]hey tell me if this painting really deserved such an honor." (Clarétie 1873).

“All these artists certainly deserved them more than the majority of the laureates, notably Messrs. Goupil and Pierre Cabanel, who should not even have been on the list of proposals. If under a political regime such as ours, where law and justice must be the supreme law, privileges must have such an obvious course; it is to despair of everything, of men as well as of institutions." (Latour 1873).

The awarding of the Medal of Honor in 1870 to Tony Robert-Fleury, son of Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleury, then president of the jury, did not elicit an equivalent reaction.

References

Altonji, J. G., & Blank, R. M. (1999). Race and gender in the labor market. Handbook of Labor Economics, 3, 3143–3259.

Anonymous. (1873). Gazette universelle. Le Petit moniteur universel, 3 April 1873.

Becker, G. S. (1971). The economics of discrimination. University of Chicago Press.

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review, 94(4), 991–1013.

Biart, L. (1873a). Salon de 1873. La France, 13 May 1873.

Biart, L. (1873b). Salon de 1873. La France, 17 June 1873.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2017). The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3), 789–865.

Bocart, F. Y. R. P., Gertsberg, M., & Pownall, R. A. J. (2022). An empirical analysis of price differences for male and female artists in the global art market. Journal of Cultural Economics, 46(3), 543–565.

Boime, A. (1971). The academy and French painting in the nineteenth century. Phaidon.

Brown, T. W. (2019). Why is work by female artists still valued less than work by male artists? Artsy. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-work-female-artists-valued-work-male-artists

Cahen, A. (1993). Les Prix de Quartier à l’Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture. Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art français, 61–84.

Cahn, I. (2016). Le Salon des refusés de 1863. ‘Un pavé tombé dans la mare aux grenouilles’. In Spectaculaire Second Empire. Musée d’Orsay et Skira.

Cameron, L., Goetzmann, W. N., & Nozari, M. (2019). Art and gender: Market bias or selection bias? Journal of Cultural Economics, 43(2), 279–307.

Chaudonneret, M.-C. (2007). Le Salon pendant la première moitié du XIXe siècle. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00176804/document

Clarétie, J. (1873). Salon de 1873. Le Soir, 21 June 1873.

Cowen, T. (1996). Why women succeed, and fail, in the arts. Journal of Cultural Economics, 20(2), 93–113.

Dupin de Beyssat, C. (2022a). Les peintres de Salon et le succès. Réputations, carrières et reconnaissance artistiques après 1848. [Unpublished PhD, Université de Tours].

Dupin de Beyssat, C. (2022b). Les peintres médaillés au Salon (1848–1880). https://haissa.huma-num.fr/s/Salons1848-1880/

Dupin de Beyssat, C. (2022c). Le choix d’un maître. Filiations réelles et prétendues des peintres au Salon (1852–1880). Autour de la notion de filiation artistique. Dialogue avec Elizabeth Prettejohn [Unpublished].

Etro, F., Silvia, M., & Elena, S. (2020). Liberalizing art. Evidence on the impressionists at the end of the Paris Salon. European Journal of Political Economy, 62, 101857.

Filloneau, E. (1869). Salon de 1869. Moniteur des arts, 7 May 1869 (804): 2.

Fried, M. (1996). Manet’s modernism, or the face of painting in the 1860s. University of Chicago Press.

Galenson, D. W. (2009). The greatest women artists of the twentieth century. In Conceptual revolutions in twentieth-century art, 93–111. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804205.007

Gallini, B. (1989). Concours et Prix d’encouragement. In La Révolution française et l’Europe : 1789–1799. Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, III: 830–851.

Ginsburgh, V. (2003). Awards, success and aesthetic quality in the arts. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(2), 99–111.

Ginsburgh, V. A., & van Ours, J. C. (2003). Expert opinion and compensation: Evidence from a musical competition. American Economic Review, 93(1), 289–296.

Goldin, C. (1990). Understanding the gender gap: An economic history of American women. Oxford University Press.

Goldin, C., & Rouse, C. (2000). Orchestrating impartiality: The impact of “blind” auditions on female musicians. American Economic Review, 90(4), 715–741.

Greenwald, D. S. (2019). Modernization and rural imagery at the Paris Salon: An interdisciplinary approach to the economic history of art. The Economic History Review, 72(2), 531–567.

Greenwald, D. S. (2021). Painting by numbers. Princeton University Press.

Greenwald, D. S., & Oosterlinck, K. (2022). The changing faces of the Paris salon: Using a new dataset to analyze portraiture, 1740–1881. Poetics, 92, 101649.

Grunchec, P. (1986). Les concours des prix de Rome, 1797–1863. École Des Beaux-Arts.

Guillemot, J. (1873). Salon de 1873. Le Soleil, 11 June 1873.

Haskell, F., (Ed.). (1981). Saloni, gallerie, musei e loro influenza sullo sviluppo dell’arte dei secoli XIX e XX. CLUEB.

Hauptman, W. (1985). Juries, protests, and counter-exhibitions before 1850. The Art Bulletin, 67(1), 95–109.

Jean-Paul. (1869). Le Salon. La Gazette de France, 27 May 1869: 2.

Jensen, R. (1988). The avant-garde and the trade in art. Art Journal, 47(4), 360–367.

Jensen, R. (1994). Marketing modernism in Fin-de-Siècle Europe. Princeton University Press.

Kearns, J., & Mill, A. (Eds.). (2015). The Paris fine art Salon: le Salo 1791–1881. Peter Lang.

Kearns, J., & Vaisse, P. (Eds.). (2010). Ce Salon à quoi tout se ramène": le Salon de peinture et de sculpture, 1791–1890. Peter Lang.

Lacas, M. (2021). Les genres ont-ils un sexe ? In Peintres femmes. Naissance d'un combat 1780–1830. Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 125–151.

Lafenestre, G. (1869). Le Salon de 1869. Le Moniteur Universel, 3(154), 3.

Latour, G. (1873). Le Salon de 1873. Le Messager de Paris, 19 June 1873.

LeBlanc, A., & Stephen S. (2021). Women artists: Gender, ethnicity, origin, and contemporary prices. Journal of Cultural Economics, 1–43.

Lechleiter, F. (2008). Les envois de Rome des pensionnaires peintres de l’Académie de France à Rome, de 1863 à 1914 [Unpublished PhD, Université Paris IV Sorbonne].

Lechleiter, F, (Ed.). (2019). Les Envois de Rome en peinture et sculpture, 1804–1914—AGORHA. Institut national d’histoire de l’art. https://agorha.inha.fr/inhaprod/ark:/54721/00180

Lemaire, G.-G. (2004). Histoire du Salon de peinture. Klincksieck.

Lobstein, D. (2006). Les Salons au XIXè siècle. Paris, capitale des arts. La Martinière.

Lora, L. (1873). Salon de 1873. Le Moniteur des arts, 13 June 1873.

Mainardi, P. (1989). The double exhibition in nineteenth-century France. Art Journal, 48(1), 23–28.

Mainardi, P. (1994). The end of the Salon: Art and the state in the early third Republic. Cambridge University Press.

Maingon, C. (2009). Le Salon et ses artistes: Une histoire des expositions du Roi-Soleil aux Artistes français. Hermann.

Méry, A. (1873). Chronique. Le Siècle, 8 June 1873.

Mill, A. (2015). Artists at the Salon during the July Monarchy. In J. Kearns & A. Mill (Eds.), The Paris fine art Salon/Le Salon, 1791–1881 (pp. 137–180). Peter Lang.

Niederle, M., & Vesterlund, L. (2007). Do women shy away from competition? Do men compete too much? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 1067–1101.

Noël, D. (2004). Les femmes peintres dans la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle. Clio. Femmes, Genre, Histoire 19.

Picon, G. (1974). 1863, Naissance de la peinture moderne. Skira.

Quéquet, S. (2014). Entre beaux-arts et industrie: l’engagement des peintres de Salon dans les manufactures françaises de céramique [Unpublished PhD, Université de Picardie Jules-Verne].

Rewald, J. (1973). The history of impressionism. Museum of Modern Art.

Rozier, J. (1873). Beaux-arts. Exposition de 1873. La Fantaisie Parisienne, 15, 7.

Salons et expositions de groupes 1673–1914 database (2006-). Musée d’Orsay and INHA.

Sanchez, P. X. S. (2001–2006). Les catalogues des Salons 1848–1880. (Vol. V-XII). L’Échelle de Jacob.

Sauer, M. (1991). L’entrée des femmes à l’École des beaux-arts, 1880–1923. École des beaux-arts.

Sfeir-Semler, A. (1992). Die Maler am Pariser Salon, 1791–1880. Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme.

Simon, C. J., & Warner, J. T. (1992). Matchmaker, matchmaker: The effect of old boy networks on job match quality, earnings, and tenure. Journal of Labor Economics, 10(3), 306–330.

Sofio, S. (2016). Artistes femmes: la parenthèse enchantée, XVIIIe-XIXe siècles. CNRS Éditions.

Szafarz, A. (2008). An alternative to statistical discrimination theory. Economics Bulletin, 10(5), 1–6.

Vaisse, P. (2010). Réflexions sur la fin du Salon official. In Kearns, J. & Vaisse, P. (Eds.), Ce Salon à quoi tout se ramène: le Salon de peinture et de sculpture, 1791–1890 (pp. 117–138). Peter Lang.

Verger, A. (2019). Rome vaut bien un prix. Une élite artistique au service de l’État: les pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome de 1666 à 1968. Artl@s Bulletin, 8(2), 18.

Verger, A. G. V. (2011). Dictionnaire biographique des pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome, 1666–1968. L’Échelle de Jacob.

Vottero, M. (2008). Autour de Léon Cogniet et Charles Chaplin, la formation des femmes peintres sous le Second Empire. Histoire De L’art, 63, 57–66.

Wilson-Bareau, J. (2007). The Salon des Refusés of 1863: A new view. The Burlington Magazine, 149(1250), 303–319.

White, C. A., & White, H. C. (1965). Canvases and careers: Institutional change in the French painting world. Wiley.

Whiteley, J. (1993). Subject index to paintings exhibited at the Paris Salon, 1673–1881). Unpublished Ph.D., Oxford University, deposited at Sackler Library, Oxford.

Yves, S., & Barrey, P. (1873). Actualités. Le Charivari, 31, 3.

Funding

The project received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

de Beyssat, C.D., Greenwald, D.S. & Oosterlinck, K. Measuring nepotism and sexism in artistic recognition: the awarding of medals at the Paris Salon, 1850–1880. J Cult Econ 47, 407–436 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-023-09472-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-023-09472-z