Abstract

This article explores the organization of cultural markets through the case of French contemporary poetry, distinguishing the market for recognition and the wider market for renown. The market of poetry is made of large-scale and reputed publishers and a wide range of smaller firms, which serve as testing grounds for new authors and innovation. How can the movement of an a priori narrow-appeal literary genre from small publishing houses to large-scale firms be explained? It is argued that if the status of firms is remarkably stable, artists may move from small publishers to large-scale ones. Statistical evidence is used to illustrate this passage, shedding a new light on the structure of cultural markets and the role of reputation in organizing commercial circuits. Future directions for research are offered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to the Syndicat national de l’Edition, poetry and plays account for less than 0.5% of total book sales. These figures combine both contemporary and classic texts, an important consideration that I return to below. Poetry has very often been described as a confidential genre, and poets’ inaccessibility as a protest against such a situation (Gitlin 1981). This article demonstrates that this confidentiality, while true, must be put into perspective.

The term is unsavory, simplistic, and is used here for want of better, as interactionists to whom we owe the “theory of labeling” would say (see Becker 1985, pp. 201–234).

Pierre-Michel Menger bases his analysis of the disparities of reputation on four propositions: there are differences of aptitude among individuals; such differences are not fully observable by comparing individuals to each other; one infers an individual’s qualities from the attention given to that individual by others; the differences among individuals are enhanced further by the social processes of reputation-building (Menger 2009, pp. 359–463).

Apollinaire, the best-selling poet in paperback in France (more than 1.3 million copies in Gallimard’s paperback collection editions alone), sold just 213 copies of his famous book, Alcools, when it appeared in 1913, despite being hailed in avant-garde circles.

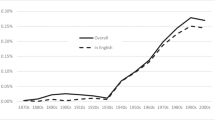

Elsewhere I have used two indexes of reputation to show how recognition and renown are built (Dubois 2008). The first index, an index of recognition, was based on a survey of thirteen anthologies of contemporary poetry, weighted according to visibility (publisher, large format or paperback edition). The second, an index of renown, takes into account the reputation of the poet’s publisher, number of books in paperback editions, number of theses written or being written about the author, the most prestigious prize for poetry (Grand Prix National de Poésie), and presence in two monograph collections on contemporary poetry. Indices and weights are discussed in author (2008). First rank in the index of renown held 780 points, second 705, twentieth 305 and fortieth 155 points (m = 143.05; σ = 143.319).

That group receives support from the CNL the most often, and they have been in existence an average of more than 20 years.

These numbers come from a consensus of actors, and match up with additional data assembled by the author. See Jean-Marc Baillieu, «L’argent de la poésie», Magazine Littéraire, no. 396, March 2001, pp. 56–57. Cheyne for instance never sells more than one thousand copies of a title a year.

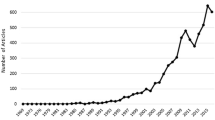

Recorded on the bookselling distribution professional database, Electre. The number of titles produced per year increases much, up to 1,800, according to the Bibliographie Nationale, which records every publication. The proliferation of very small publishers, who are not all professionalized, explains this gap.

Actes Sud has met with great success in the past thirty years, including winning the Goncourt prize. Yet its turnover represents approximately 25 million Euros, while Gallimard’s reaches 260 million Euros.

At Gallimard, the backlist represents more than 60% of its turnover.

Only two contemporary authors from our dataset have published poetry at Albin Michel. One of the authors is the literary editor at Albin Michel, showing to what extent the market is rooted in personal relations.

The Centre National du Livre counted 200 publishers of poetry in the early 80 s, and 400 today. The increase is largely—but not exclusively—the result of increased public funding. On this increase in publishers see Bouvaist and Boin (1989).

No one could have predicted that out of the catalog of Saint-Germain des Prés Editions, a publisher often criticized for practices that verge on publishing at the author’s expense, poets like Michel Deguy or Guy Goffette would surface, poets who can boast today of several volumes in Le Seuil and Gallimard’s prestigious collections.

Gaston Gallimard used to say he was financing poetry with detective novels (Assouline 2006).

Le Seuil and Flammarion have recently been bought.

As an example, the aforementioned publisher Cheyne distributes its own books among approximately eighty bookstores, that number representing the few bookstores who, according to Cheyne’s editor, are prepared to display the books well and properly represent them to readers.

Bourdieu asserted—without much empirical support—that the pole of restricted distribution is a market of “producers for producers” (1998, p. 235).

The large publishers often bundle their titles, in an agreement known in French as “l’office”, whereby sellers accept the titles and numbers of copies determined by the publisher in exchange for discounts and the ability to return unsold stock. The “office” arrangement makes it difficult for the small publishers to compete with the large publishers.

This renown index includes the number of paperback editions, the number of books at first-class publishers, the best-known poetry prize, the presence in the two poetry monographic collections, the presidency of the poetry commission of the CNL. See Dubois (2009) for further details about its development.

Information from the CNL was particularly helpful, including the number of books it subsidized for the various publishing houses between 1996 and 2002.

Bourdieu (1999) uses sixteen criteria—economic and social ones, like turnover and sales levels, number of salaried employees, shareholders and legal status; literary and symbolic criteria, looking at the Jurt Index, which reviews 28 literature textbooks, the number of publications of work by French literary prize winners and French and foreign Nobel Prize winners. “First Class” includes Gallimard, Le Seuil, Flammarion, Grasset, Laffont, Albin Michel, and Minuit. Among publishers whose catalogs were consulted for this study, the largest show an average turnover of €54,386,000 and length of service of 101 years. Each of these publishers owns its own means of distribution. The smaller-reputation firms average a turnover of €357,278 and length of service of 24 years; all of them are private limited companies, and either handle their distribution themselves or outsource it, in many cases to the larger publishing houses.

Magazine Littéraire offers a column of poetry works as well as special issues on an author. Both were recorded in the database, as well as its special issue on contemporary poetry.

Radio has played and continues to play a key role in the diffusion of poetry, as public readings and oral performances having opened new diffusion channels for poets (Dubois and Craig 2010).

As an illustration, poets represent 32.5% of the Nobel Prize laureates.

La Pléiade is probably the best-known collection on the French book market. In a prestigious and elegant format it offers the complete works of consecrated writers, with commentaries, biographical description, footnotes and references. It represents around 15% of Gallimard’s turnover.

Jaccottet’s first publication at Gallimard goes back as far as 1948, and Bonnefoy’s to 1951. Both (born respectively in 1923 and 1925) were the first contemporaries to enter Gallimard’s pocket collection in 1970 and 1971.

Tests for heteroscedasticity and variable inflations factors (vif) have been performed. Results confirm the validity of the model.

Examples of this abound. One of the most recent and successful is Gallimard’s 2006 publication, L’élégance du hérisson, by Muriel Barbery, which very unexpectedly sold more than a million copies and sat atop the bestseller list for 30 weeks in a row, owing primarily to the active support of booksellers and word-of-mouth.

Cited in Patrick Kéchichian and Émilie Grangeray, "Ces singuliers de l’édition", Le Monde, March 12, 1999. It should be noted that his expression “as many people as possible” equals roughly one new author per year.

The best-known textbook of French literature, Lagarde et Michard, stops in 1960. Viart and Vercier (2005) have offered a general introduction to contemporary literature that aims at filling this gap, presenting the most famous contemporary poets. They insist on three names, which appear at the top of my own renown index and have the most books in paperback editions.

For instance, the two academics to have supervised the most PhDs about contemporary poets are poets themselves, have directed journals and both directed the Centre d’études pour la poésie at the most famous French academic institution, l’Ecole Normale Supérieure.

References

Anand, N., & Watson, M. R. (2004). Tournament rituals in the evolution of fields: The case of the Grammy awards. Academy of Management Journal, 47(1), 59–80.

Assouline, P. (2006). Gaston Gallimard, un demi-siècle d’édition française. Paris: Gallimard.

Baker, A. J. (1991). A model of competition and monopoly in the record industry. Journal of Cultural Economics, 15(1), 29–54.

Banerjee, A. (1992). A simple model of herd behavior. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(3), 797–817.

Basuroy, S., Chatterjee, S., & Ravid, S. A. (2003). How critical are critical reviews? The box office effects of film critics, star power, and budgets. Journal of Marketing, 67(4), 103–117.

Becker, H. (1985). Outsiders. Paris: Métailié.

Becker, H. (2006). Les mondes de l’art. Paris: Flammarion.

Boschetti, A. (2001). Apollinaire, homme-époque. Paris: Le Seuil.

Boudon, R. (1981). L’intellectuel et ses publics. In J. D. Reynaud & Y. Grafmeyer (Eds.), Français qui êtes-vous?. Paris: Documentation française.

Bourdieu, P. (1998). Les règles de l’art. Paris: Le Seuil.

Bourdieu, P. (1999). Une révolution conservatrice dans l’édition. Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales, 126–127, 3–29.

Bouvaist, J. M., & Boin, J. G. (1989). Du printemps des éditeurs à l’âge de raison. Paris: Documentation française.

Bowness, A. (1989). The conditions of success. How the modern artist rises to fame. London: Thames & Hudson.

Burt, R. (1994). Structural holes and good ideas. American Journal of Sociology, 110(2), 349–399.

Carroll, G. R. (1984). Organizational ecology. Annual Review of Sociology, 10, 71–93.

Castaner, X., & Campos, L. (2002). The determinants of artistic innovation: Bringing in the role of organizations. Journal of Cultural Economics, 26, 29–52.

Castellin, P. (2002). Histoire, formes et sens des poésies expérimentales. Romainville: Al Dante.

Cattani, G., & Ferriani, S. (2008). A core/periphery perspective on individual creative performance: Social networks and cinematic achievements in the Hollywood film industry. Organization Science, 19(6), 824–844.

De Vany, A. (2004). Hollywood economics. How uncertainty shapes the film industry. London: Routledge.

DeNora, T. (1991). Musical patronage and social change in Beethoven’s Vienna. The American Journal of Sociology, 97(2), 310–346.

DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Dowd, T. J. (2004). Production perspectives in the sociology of music. Poetics, 32, 235–246.

Dowd, T. J., Johnson, C., & Ridgeway, C. L. (2006). Legitimacy as social process. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 53–78.

Dubois, J. (2005). L’institution littéraire. Bruxelles: Labor.

Dubois, Sébastien. (2006). The French poetry economy. International Journal of Arts Management, 9(1), 23–34.

Dubois, S. (2008). Mesurer la réputation. Reconnaissance et renommée des poètes contemporains. Histoire & Mesure, 23(2), 103–143.

Dubois, S. (2009). Entrer au panthéon littéraire. Consécration des poètes contemporains. Revue française de sociologie, 50(1), 3–29.

Dubois, S., & Craig, A. (2010). Between art and money: The role of readings in contemporary poetry, a new economy for literature? Poetics, 38(5), 441–460.

Escarpit, R. (2006). Sociologie de la littérature. Paris: PUF.

Eymard-Duvernet, F. (1989). Conventions de qualité et formes de coordination. Revue économique, 40(2), 329–360.

Faulkner, R. R., & Anderson, A. B. (1987). Short-term projects and emergent careers: Evidence from Hollywood. American Journal of Sociology, 92(4), 879–909.

Fombrun, C., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33(2), 233–258.

François, P. (2006). Le monde de la musique ancienne. Paris: Economica.

Gemser, G., Leenders, M. A. A. M., & Wijnberg, N. M. (2008). Why some awards are more effective signals of quality than others: A study of movie awards. Journal of Management, 34(1), 25–54.

Gemser, G., & Winjberg, N. (2000). Adding value to innovation: Impressionism and the transformation of the selection system in visual arts. Organization Science, 11(3), 323–329.

Ginsburgh, V., & Weyers, S. (2006). Persistence and fashion in art Italian Renaissance. From Vasari to Berenson and beyond. Poetics, 34, 24–44.

Gitlin, T. (1981). Inaccessibility as protest: Pound, eliot and the situation of American poetry. Theory and Society, 10(1), 63–80.

Gould, R. V. (2002). The origins of status hierarchies: A formal theory and empirical test. American Journal of Sociology, 107(5), 1143–1178.

Greco, A. M. (2000). Market concentration in the US Consumer Book Industry: 1995–1996. Journal of Cultural Economics, 24, 321–336.

Guillaume, D. (2002). Poétiques & poésies contemporaines. Cognac: Le temps qu’il fait.

Hannan, M., & Freeman, J. (1977). The population ecology of organizations. American Journal of Sociology, 82(5), 929–964.

Hannan, M., & Freeman, J. (1986). Where do organizational forms come from? Social Forces, 1(1), 50–72.

Heinich, N. (2005). L’élite artiste. Paris: Gallimard.

Hirsch, P. (1972). Processing fads and fashions: An organization-set analysis of cultural industry systems. American Journal of Sociology, 77(4), 639–659.

Holbrook, M. B., & Addis, M. (2008). Art versus commerce. A two-path model of motion picture success. Journal of Cultural Economics, 32, 87–107.

Jensen, M., & Roy, A. (2008). Staging exchange partner choices: When do status and reputation matter? Academy of Management Journal, 51(3), 495–516.

Jones, C. (1996). Careers in projet networks: The case of the film industry. In M. B. Arthur & D. M. Rousseau (Eds.), The boundaryless career: A new employment principle for a new organizational era (pp. 58–75). New York: Oxford University Press.

Jones, C. (2002). Signaling expertise: How signals shape careers in creative industries. In M. A. Peiperl, M. B. Arthur, & N. Anand (Eds.), Career creativity: Exploration in the remaking of work (pp. 209–228). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kapsis, R. E. (1989). Reputation building in the film-art world: the case of Alfred Hitchcock. Sociological Quarterly, 30(1), 15–35.

Lang, G. E., & Lang, K. (1988). Recognition and renown: The survival of artistic reputation. American Journal of Sociology, 94(1), 79–109.

Legendre, B., & Abensour, C. (2007). Les petits éditeurs. Situations et perspectives. Paris: Documentation française.

Maulpoix, J. M. (2001). Frictions. In F. Smith & C. Fauchon (Eds.), Zigzag Poésie (pp. 79–86). Paris: Autrement.

McLaughlin, N. (2001). Optimal marginality: Innovation and orthodoxy in Fromm’s revision of psychoanalysis. Sociological Quaterly, 42(2), 271–288.

Menger, P. M. (1999). Artistic labor markets and careers. Annual Review of Sociology, 25, 541–574.

Menger, P. M. (2001). Le paradoxe du musicien. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Menger, P. M. (2009). Le travail créateur. Paris: Gallimard/Le Seuil.

Merton, R. K. (1968). The Matthew effect in science. Science, 159, 56–63.

Merton, R. K. (1988). The Matthew effect in science II. Cumulative advantage and the symbolism of intellectual property. Isis, 79, 606–623.

Milo, D. (1986). Le phénix culturel: de la résurrection dans l’histoire de l’art. Revue Française de Sociologie, 27(3), 481–503.

Mollier, J. Y. (1988). L’argent et les lettres. Paris: Fayard.

Mollier, J. Y. (2008). Edition, presse et pouvoir en France au XXe siècle. Paris: Fayard.

Moulin, R. (2009). L’art, l’institution et le marché. Paris: Flammarion.

Mulkay, M., & Chaplin, E. (1982). Aesthetics and the artistic career: A study of anomie in fine-art painting. Sociological Quarterly, 23, 117–138.

Nalebuff, B. J., & Brandenburger, A. M. (1996). Co-opetition. New York: Currency Doubleday.

Ordanini, A. (2006). Selection models in the music industry: How a prior independent experience may affect chart success. Journal of Cultural Economics, 30, 183–200.

Otchakovsky-Laurens, P. (1993). Etats Généraux de la Poésie. Marseille: Musées de Marseille/cipM.

Perry-Smith, J. E., & Shalley, C. E. (2003). The social side of creativity: A static and dynamic approach. Academy of Management Journal, 28(1), 89–106.

Podolny, J. (1993). A status-based model of market competition. American Journal of Sociology, 98(4), 829–872.

Rao, H. (1994). The social construction of reputation: Certification contests, legitimation, and the survival of organizations in the American automobile industry: 1895–1912. Strategic Management Journal, 15, 29–44.

Reynaud-Cressent, B. (1982). La dynamique d’un oligopole à franges. Le cas de l’édition de livres en France. Revue d’économie industrielle, 22, 61–71.

Rindova, V. P., Williamson, I. O., Petkova, A. P., & Sever, J. M. (2005). Being good or being known: An empirical examination of the dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of organizational reputation. Academy of Management Journal, 48(6), 1033–1049.

Roberts, P. W., & Dowling, G. R. (2002). Corporate reputation and sustained superior financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 23(12), 1077–1093.

Rosen, S. (1981). The economics of Superstars. American Economic Review, 71(5), 845–858.

Rosengren, E. (1985). Time and literary fame. Poetics, 14, 157–172.

Rouet, F. (2008). Le livre, mutation d’une industrie culturelle. Paris: Documentation française.

Schiffrin, A. (1999). L’édition sans éditeurs. Paris: La Fabrique.

Schiffrin, A. (2005). Le contrôle de la parole. Paris: La Fabrique.

Simonin, A. (1998). L’édition littéraire. In P. Fouché (Ed.), L’édition française depuis 1945 (pp. 30–87). Paris: Cercle de la librairie.

Spence, M. (1974). Market signaling. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Storper, M., & Christopherson, S. (1989). The effects of flexible specialization on industrial politics and the labor market: The motion picture industry. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 42(3), 331–347.

Van Rees, C. (1987). How reviewers reach consensus on the value of literary works. Poetics, 16, 275–294.

Van Rees, C., & Vermunt, J. (1996). Event history analysis of author’s reputation: Effects of critics’ attention on debutant careers. Poetics, 23, 317–333.

Verboord, M. (2003). Classification of authors by literary prestige. Poetics, 31(3–4), 259–281.

Viart, D., & Vercier, B. (2005). La littérature française au présent. Paris: Bordas.

Vourc’h, C. (2003). Loisirs et pratiques culturels des étudiants. Observatoire de la vie étudiante, 7, 1–15.

White, H., & White, C. (1991). La carrière des peintres au XIX e siècle. Paris: Flammarion.

Wijnberg, N. M., & Gemser, G. (2000). Adding value to innovation: Impressionism and the transformation of the selection system in visual arts. Organization Science, 11(3), 323–329.

Zuckerman, E. W. (1999). The categorical imperative: Securities analysts and the illegitimacy discount. American Journal of Sociology, 104(5), 1398–1438.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dubois, S. Recognition and renown, the structure of cultural markets: evidence from French poetry. J Cult Econ 36, 27–48 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-011-9153-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-011-9153-3