Abstract

The practice of cremation is often interpreted as an alternative to inhumation, taking place shortly after an individual’s death. However, cremation could be a final stage in complex mortuary practices, with previous steps that are obscured due to the heating process. This project reports on experimental scoping research on a set of experimentally heated femoral fragments from modern and archaeological collections of the University of Coimbra. Sixteen recent femur samples from eight individuals, as well as five femur samples from an archaeological skeleton from the medieval-modern cemetery found at the Hospital de Santo António (Porto), were included in this research. Samples presented five different conditions: unburnt, and burnt at maximum temperatures of 300 °C, 500 °C, 700 °C and 900 °C. Each sample was prepared to allow observation using binocular transmitted light microscopes with ×10, ×25 and ×40 magnifications. Results indicated that, if burial led to bioerosion, this will remain visible despite burning, as could be in cases where cremation was used as a funerary practice following inhumation. From this, we conclude that the observation of bioerosion lesions in histological thin sections of cremated bone can be used to interpret potential pre-cremation treatment of the body, with application possibilities for both archaeological and forensic contexts. However, the effect on bioerosion of substances such as bacterial- or enzymatic-based products often used to accelerate decomposition should be investigated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A central question in funerary archaeology is how human remains were treated and manipulated shortly after death (e.g. Roksandic 2002; Duday 2006; Knüsel and Robb 2016; Booth 2016). The practice of cremation is often interpreted as an alternative to inhumation, taking place shortly after an individual’s death. However, cremation could be a final stage in complex mortuary practices of bodily treatment, with previous steps that are obscured due to the heating process. Also, burning may have occurred on dry remains as a result of non-funerary practices such as accidental fires or skeletal reduction to free some space in funerary settings (Duday and Guillon 2006, Duday et al. 2009). Distinguishing such disparate practices is troublesome because of equifinality. The impact of heat exposure in skeletal remains is often quite similar regardless of their being fresh or dry (Gonçalves et al. 2011).

Traditional methods for distinguishing bones burned dry from bones burned fresh are based on heat-induced colour pattern, fracture patterns and warping (Baby 1954; Binford 1963; Etxeberria 1994; Symes et al. 2008; Symes et al. 2014). However, colour pattern is not always useful since remains can be completely monochromatic, as is the case in completely calcined skeletons. Fracture patterns and warping are unreliable criteria since those features are non-specific, i.e. they can occur in remains that were burnt fresh (either fleshed or recently defleshed) or dry (Buikstra and Swegle 1989; Spennemann and Colley 1989; Whyte 2001; Gonçalves et al. 2011, 2015). Other factors, such as collagen content, temperature increment and even the force of gravity, appear to be influencing variables in the occurrence of such features (Vassalo et al. 2016, 2019). We are therefore in need of other, more reliable indicators for pre-burning funerary deposition and bodily state. One method applied to non-burnt bones is based on the observation of potential bioerosion via thin sections using transmitted microscopy, to identify taphonomically induced diagenetic alterations to the internal microstructure of archaeological bone (Hollund et al. 2012; Booth 2016; Jans 2005).

Bioerosion concerns the biological degradation of the organic and mineral phases of bone microstructure (Nielsen-Marsh et al. 2007; Smith et al. 2007; Grupe and Dreses-Werringloer 1993; Garland 1987, 1993). Microbial bioerosion is the most common and most rapidly occurring form of diagenesis found in archaeological bones from temperate environments, its amount and speed of manifestation influenced by factors such as soil pH and hydrology, oxygen conditions and temperature (Kendall et al. 2018; Collins et al. 1995; Hedges 2002; Turner-Walker et al. 2002, Jans et al. 2004; Jans 2005) with visibility from as early as 3 months’ postmortem (Bell et al. 1996). The aetiology of bioerosion could be sought in exogenous factors such as exposure to soil micro-organisms (Grine et al. 2015; Kendall et al. 2018; Kontopoulos et al. 2016; Turner-Walker 2012), but bone diagenesis is also thought to be caused by an individual’s putrefactive gut bacteria (Child 1995a, b; Gill-King 1997; White and Booth 2014; Booth 2016; Booth and Madgwick 2016). This endogenous origin would suggest that the presence and level of bacterial bone bioerosion observable in histological sections of archaeological bone should reflect the extent to which the skeleton was exposed to putrefaction (White and Booth 2014; Booth 2016; Jans 2008, 2013, Jans et al. 2014). According to this model, different types and amounts of bioerosion would correlate with specific forms of funerary and corpse treatment (Booth 2016), specifically distinguishing corpses buried soon after death from those undergoing different forms of mortuary treatment. Exposed animal and human remains, such as butchered bones and excarnated, unburied corpses, tend to show low levels of bacterial bioerosion since soft tissue is rapidly removed from the skeleton, minimally exposing bones to soft tissue decomposition instigated by gut bacteria (Rodriguez and Bass 1983; Bell et al. 1996; Simmons et al. 2010; White and Booth 2014; Brönnimann et al. 2018). In contrast, articulated skeletal remains often display high levels of bacterial bioerosion (Jans et al. 2004; Nielsen-Marsh et al. 2007). Hence, the examination of the type and extent of bioerosion in archaeological human remains could elucidate complexities in mortuary treatment (Bell et al. 1996; Jans et al. 2004; Pearson et al. 2005; Nielsen-Marsh et al. 2007; Smith et al. 2007; Turner-Walker and Jans 2008; Hollund et al. 2012).

The consequences of enteric bioerosion are interesting for interpreting early postmortem treatment of the body through histology, since this type of erosion is thought to commence during the initial stages of decomposition (Brönnimann et al. 2018, White and Booth 2014; Booth 2016; Jans 2008, 2013, Jans et al. 2014). Exogenous bacterial attack, in contrast, is likely to have a much longer timeline, taking months or even up to centuries to manifest (Bell et al. 1996; Hedges 2002; Hedges et al. 1995) and its presence therefore would reflect a longer period of burial and decomposition. Regardless of an exogenous or enteric aetiology, osteolytic bacterial activity is thought to be related to interment of remains and therefore its assessment is deemed useful for reconstructing postmortem treatment of human remains.

Although bioerosion as a criterion to detect postmortem burial has been successfully applied to inhumation burials (e.g. Booth et al. 2015; Booth and Madgwick 2016; Smith et al. 2016), cremations and other burials with burnt skeletal remains have so far only received limited attention (e.g. Grevin et al. 1990). This is probably partly due to an assumption that bodies are cremated soon after death, but in fact, cremation may be delayed for a variety of reasons (e.g. Wahl and Kokabi 1988; van den Bos and Maat 2002). If a corpse was subjected to some kind of treatment or manipulation prior to cremation, this could have resulted in putrefaction as well as exposure to soil bacteria, if enough time went by, and hence lead to the formation of bioerosive lesions.

In order for bioerosion to be investigated in cremated bone, it is necessary to establish that such lesions are not rendered invisible by the cremation process. Heating can alter bone microstructure through cracking and splitting, often emanating from the haversian canals (Brain 1993; Hanson and Cain 2007), warping and shrinkage, colour alteration according to burning degree, and at the highest degrees, fusing of hydroxyapatite crystals and obliteration of haversian structure (Forbes 1941; Gonçalves et al. 2011; Herrmann 1977; Bradtmiller and Buikstra 1984; Henderson et al. 1987; Hummel and Schutkowski 1993; Squires et al. 2011; Lemmers 2012) which can have a negative effect on microstructure analysis. Furthermore, carbon deposits can get incorporated in the bone microstructure, thereby blackening and decreasing visibility of histological features and enlarging the osteocyte lacunae (Grosskopf 2004). This makes it problematic to use the enlargement of osteocyte lacunae, which is interpreted to be a sign of bioerosion, as a reliable criterion for pre-burning deposition (Grevin et al. 1990). However, since organic components are often partly or completely lost, the remains from an individual who was completely cremated shortly after death are no longer of interest to microorganisms (Cattaneo et al. 1999; Fernández Castillo et al. 2013a, b; Herrmann 1977; Lemmers 2012; Mays 1998) and histological features can stay very well preserved (Fig. 1). Histological studies of cremated remains have generally not reported on the presence of bioerosion (Grosskopf 2004; Lemmers 2012; Squires et al. 2011). One study reports on fungal attack in cremated remains, but correlates this to the presence of animal meat as burial gift placed adjacent to cremated bone, making it attractive for fungi (van den Bos and Maat 2002). In the absence of such burial gifts, burned bone demonstrating bioerosion must have been exposed to erosive circumstances prior to the burning event, such as temporary inhumation.

Example of a histological section (femur) obtained from an Iron Age cremation burial (known as the Chieftain of Oss, cremated at ~ 800 °C, Lemmers et al. 2012), viewed under polarised light. Immaculate conservation of histological features (H = haversian canal) and no signs of bioerosion. Osteocyte lacunae (OL) are enlarged due to carbon inclusion. Bone sample provided by the National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden, The Netherlands. Section made by Lemmers and Koot, VU Amsterdam

No research has been carried out previously to determine if bioerosion lesions remain visible after human remains are burnt and if these can be used to reconstruct processes of bodily putrefaction and decay prior to heat exposure. In this paper, we aimed to assess whether bacterial bioerosion remains visible in recent and archaeological samples of experimentally burnt bones that have been previously buried. To that end, the presence of bacterial bioerosion was assessed in both unburnt and experimentally burnt samples from the same bone. Varied temperature thresholds were investigated to account for heat-induced alteration of the histological structure. If bioerosion lesions are demonstrated to remain visible after burning, then burnt bone histology can be used as a criterion for estimating the pre-burning condition of the remains, thus greatly contributing to archaeological and forensic studies on early postmortem treatment of subsequently burnt remains.

Material and Methods

We sampled bone from two osteological collections, both housed in the Department of Life Sciences at the University of Coimbra, Portugal (Table 1). The first consisted of eight recent skeletons (referred to as CC-NI) from the same cemetery as the 21st Century Identified Skeletal Collection (referred to as CEI/XXI) (Ferreira et al. 2014). The skeletons do not form part of the CEI/XXI as they are not from known individuals. These individuals were exhumed from the municipal cemetery of Capuchos, in Santarém (Portugal) and presumably were of Portuguese ancestry. The precise age at death and sex of these skeletons is unknown, but all were adults and osteological examination suggested the presence of two males (CC-NI 31, 32) and five females (CC-NI 33, 34, 42, 51, 53). The sex of individual CC-NI-41 was undetermined. These individuals were buried for at least 3 years, which is the minimum required period of inhumation time prior to exhumation according to Portuguese legislation (Decreto-Lei 411/98). The bone sampled from this collection will be referred to as ‘recent bone’. Given the possible small amount of inhumation time of these skeletons, archaeological remains were also used in this investigation. As a result, the other collection consists of archaeological skeletons of individuals from a historical cemetery found at the Hospital de Santo António in Porto (Portugal). This cemetery was used during the Modern period ranging from the seventeenth century AD to the beginning of the twentieth century AD. Therefore, the remains were buried for a minimum of 80 years. Samples from a single individual were taken from this collection. Bone sampled from this collection will henceforth be referred to as ‘archaeological bone’.

Although we currently do not have information available regarding the hydrology and soil type of the specific regions, the individuals from both collections were buried for a substantial period; hence, the presence of bioerosion was expected (Booth 2016; Booth and Madgwick 2016; Booth et al. 2015; Jans 2005). We focussed our sampling on femur cortical bone diaphysis since femoral fragments are often preserved in cremation assemblages due to the robusticity of the cortex and are easily identifiable due to the marked linea aspera. Furthermore, the femoral midshaft is often targeted for consistency among histological studies of bone diagenesis, since the large amount of cortical bone clearly displays the histological features (e.g. Hollund et al. 2015; White and Booth 2014). The femur is also thought to be close enough to the gut to display osteolytic bacterial activity; an interpretation borne out by previous work on bioerosion (Jans et al. 2004).

We selected in total 21 femoral samples: 16 from the recent collection and 5 from the archaeological collection (Table 1). Next, half of the samples in Set 1 were subjected to controlled burnings at maximum temperatures of 300 °C, 500 °C, 700 °C and 900 °C in an electric muffle (Barracha K3, three-phased). The burnings took approximately 20, 40, 90 and 160 min to reach those temperatures, respectively. This resulted in a range of both burnt and unburnt femoral samples (Table 1).

All femoral fragments, burnt and unburnt, were sectioned and polished according to the standard procedure of the Hard Tissues Laboratory of the Dentistry Department of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Coimbra (Oliveira-Santos et al. 2017). We embedded femoral fragments of roughly 3 cm in length in histological resin (Technovit 7200 VLC—Kulzer) and polymerised them for 7 h (Exakt® 520 Light Polymerization Unit) to allow sectioning them without damaging their integrity. Cross-sectioning was executed with a diamond blade low-speed precision saw (Exakt® Band System 300 CL/CP for Set 1, Isomet 1000 for Set 2). The rest of the sectioned block was kept as a back-up to allow any additional sectioning in future. We fixated sections and polished them (Micro Grinding System Exakt® 400 CS for Set 1, hand polished Set 2) to an approximate final thickness of 20–50 μm. We judged every sample individually and refined the thickness to obtain optimal visibility. Observations were performed using transmitted light binocular microscopes using ×10, ×25 and ×40 objectives. Micrographs were taken with a coupled camera. Micrograph stitches were produced with Adobe Photoshop CS3.

We scored the microstructure of each unburnt sample according to the standard Oxford Histological Index (OHI, Hedges et al. 1995; Millard 2001) on a scale of 0 (no original features identifiable, except haversian canals) to 5 (very well preserved, similar to recent bone). This ordinal measure of bioerosion relates to the percentage of unaltered bone microstructure (Hedges et al. 1995; Millard 2001). The OHI correlates with absolute measures of diagenesis such as protein/collagen yield, suggesting that it is a useful measure of biodeterioration (Hedges et al. 1995, Haynes et al. 2002, Nielsen-Marsh et al. 2007, Smith et al. 2007, Ottoni et al. 2009, Sosa et al. 2013). The unburnt sections, serving as an indicator of the amount of bioerosion observable in each individual, were used as a base to establish the degree of bioerosion which might be observable in the experimentally burnt bone. For the burnt sections, we described the visibility of structures as either good, medium or poor (Table 2). Only samples of categories good or medium were included in the assessment of bioerosion presence.

We based the identification of bioerosion in the unburnt and experimentally burnt samples on previous work describing the character and location of the lesions in cortical bone (Booth 2016; Booth and Madgwick 2016; Booth et al. 2015; Jans 2005) and the authors received additional training by Dr. T. Booth. Bioerosion in bone consists of different types of micro-foci of destruction (MFD) caused by fungal and bacterial erosion as budded MFD, linear longitudinal MFD, lamellate MFD, Wedl tunnelling, enlarged canaliculi (Wedl type 2) and cyanobacteria tunnelling (Fig. 2). MFD with a bacterial origin generally manifests according to the microanatomy of bone and does not follow an outside inward pattern, but affects the bone throughout (e.g. Jans 2005, 2013; Booth 2016; Brönnimann et al. 2018). Wedl tunnelling is thought to have a fungal origin, although cyanobacteria may also be responsible (Kendall et al. 2018; Fernández-Jalvo et al. 2010). Wedl-tunnels appear as linear-longitudinal tunnel-shaped lesions not following the histological structure and having diameters up to 8 μm (Hackett 1981; Piepenbrink 1984; Schultz 1986; Wedl 1864). In archaeological contexts, Wedl tunnelling is more often associated with butchered rather than articulated skeletons (Booth 2016; Jans et al. 2004, Nielsen-Marsh et al. 2007). The forms of MFD with a bacterial origin are extremely common in archaeological human bone from terrestrial contexts (Balzer et al. 1997; Jackes et al. 2001; Turner-Walker and Syversen 2002; Booth 2016). Since our research deals with bone from closed contexts (buried, articulated human remains), we mainly expected to see bacterial MFD in our sample. The occurrence of bioerosion was recorded on a presence/absence basis (Booth 2016).

Micrograph of transverse adult femoral thin section (Capuchos, Portugal). Haversian canals (H) and osteocyte lacunae (arrows). Schematic representation of bioerosive lesions: budded mfd (1); linear longitudinal mfd (2); lamellate mfd (3); Wedl tunnelling (4); enlarged canaliculi/Wedl type 2 (5); cyanobacteria tunnelling (6) (after Brönnimann et al. 2018, Jans 2005)

Results

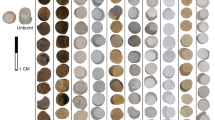

All recent unburnt samples had well-preserved microstructures with minor amounts of destructive foci, resulting in an OHI score of 4–5 for each section (Table 3, Fig. 3a–c). The archaeological unburnt sample showed higher levels of bioerosion, resulting in OHI scores of 3 (Table 3 & Fig. 4a–c). The majority of burnt samples had good or medium histological visibility, except for the 500 °C archaeological sample, which subsequently was excluded from further analysis (Table 4).

Experimentally burnt femoral fragments from recent collection with limited/absence of bioerosion. a Overview section (unburnt); b, c unburnt sections for reference with minimal destruction to internal microstructure, d 300 °C, e 500 °C, f 700 °C, g 900 °C. Indicated are haversian canals (H), canaliculi (CL), areas of carbon inclusion (ci) and splitting of haversian systems (spl) due to the increased temperature exposure

Experimentally burnt femoral fragments from the Hospital de Santo António archaeological collection. a Overview section (unburnt). b, c Unburnt sections with clear bioerosion observable, d 300 °C, e 500 °C, f 700 °C, g 900 °C. Indicated are haversian canals (H) and regions of substantial carbon inclusion (ci). Bioerosion indicated with arrows, scattered throughout the bone microstructure, around haversian systems and a subperiosteal band

No bioerosion could be identified with certainty within the burnt recent samples (0 out of 8). All archaeological samples with either good or medium visibility showed clearly recognisable MFD (3 out of 3, Fig. 4d–g). The observable bioerosion in all samples could be attributed to non-Wedl (bacterial) erosion, not following an outward-inward pattern and following the histological features. Additionally, a zone of bacterial erosion was observable in the region below the periosteum (Fig. 4a), which remained visible in all burning degrees, (Fig. 4g, left arrow).

Discussion

The results from this study indicate that bioerosion is observable in burnt bone. The bioerosion present in the archaeological samples remained clearly visible after experimental burning at all temperature thresholds with good or medium visibility. This therefore means that the presence and visibility of bioerosion are not obscured by burning. Bone alterations caused by burning are very different from lesions caused by bioerosion. The most prominent alteration to the microstructure with regard to the burning process, apart from warping and shrinkage, is the incorporation of carbon into the microstructure, thereby blackening and decreasing visibility of histological features (Grosskopf 2004). This is particularly evident in Fig. 3e (500 °C), where darkened areas are visible around the haversian canals. These well-defined and smooth-edged regions of carbon inclusion are, however, clearly visually distinguishable from bacterial erosion which follows osteological structures and therefore cannot be easily mistaken for one another. However, a feature commonly found in cremated remains is the enlargement of the canaliculi due to carbon inclusion (Grosskopf 2004). Enlarged osteocytes are also a feature described in the context of bioerosion (Wedl type 2, Bell et al. 1996; Brönnimann et al. 2018, White and Booth 2014; Booth et al. 2015; Tjelldén et al. 2018). With traditional light microscopy, it is challenging to differentiate whether osteocytes are enlarged due to bioerosion or due to the cremation process, and it is advisable to not use such features in the final determination of the pre-burning condition of bone.

When bioerosion is minimal (OHI of 4–5), the MFD will likely not stand out after heat exposure since minor signs of bioerosion are difficult to distinguish from enlargement and blackening of osteocyte lacunae caused by the heating process. This was demonstrated by our lack of MFD recognition in the experimentally burnt recent samples. Using bioerosion as a criterion for reconstructing patterns of pre-burning funerary deposition and treatment should therefore be done with a degree of caution, since the absence of bioerosion in cremations, for example, cannot be held as a strict guarantee that the corpse has been cremated directly after death, as a primary funerary practice. On the other hand, when the presence of bioerosion can be confirmed in burned bone, it serves as an indication that burning occurred as subsequent to an act such as burial or deposition. Caution should also be taken when dealing with lower burning degrees, partial or light cremations leading to the incomplete pyrolysis of the soft tissue, which could theoretically enable post-burning activity by microorganisms. Fully calcined bone, however, would not have any organic component left and the presence of bioerosion in such material should be considered as a clear sign of pre-burning funerary deposition. The burning degree did not affect the visibility of bioerosion, except for bone burnt at 500 °C. In particular, the archaeological sample burnt at 500 °C was scored as poor and its microstructure could not be observed properly due to the high level of carbon incorporation, which is again lost with increasing temperatures. However, the recent samples burnt at 500 °C had medium visibility. It is therefore likely possible to include bone burnt at 500 °C but multiple samples should be taken to ensure visibility. One way of bypassing this obstacle could be by subjecting charred samples to an additional burning up to temperatures leading to calcination. This would potentially enhance the visibility of histological features.

Since all samples for this project came from buried individuals, we expected bioerosion in all sections (e.g. Booth and Madgwick 2016; White and Booth 2014; Jans 2005). However, we found remarkably well-preserved microstructure with only minor bioerosion in the recent samples. Variation in bioerosion between the recent and archaeological individuals is likely not due to the age difference of the human remains, since time is generally considered as the least important contributory factor to the process of postmortem change (Bell et al. 1996; Piepenbrink 1986, Piepenbrink and Schutkowski 1987); Postmortem bone alteration begins during putrefaction through the gut bacteria, and, once begun, progresses at particular rates related to other circumstances as direct postmortem conditions and environment.

The human remains used in this study were from different locations within Portugal that, at the larger scale, present quite distinct soil properties and climates (Ramos et al. 2017). The differences in local soil circumstances may therefore have contributed to the different manifestation of bioerosion. An extensive study on bone histotaphonomy (Brönnimann et al. 2018) found no correlations between the intensity of bacterial attack and sediment types or sedimentation processes respectively; however, differences related to anoxic or waterlogged conditions between the two collections, if present, could have influenced the difference in amount of bioerosion observed (Turner-Walker and Jans 2008; Hollund et al. 2012; Booth 2016). Seasonality might affect the nature of bodily decomposition (Rodriguez and Bass 1983; Mann et al. 1990; Manhein 1997; Campobasso et al. 2001; Wilson et al. 2007; Zhou and Bayard 2011; Meyer et al. 2013), and with that, the amount of bioerosion. It is difficult to determine whether seasonality was the determining factor causing the differences in bioerosion between the two Portuguese collections, since we do not have this information available for each individual analysed for this study. However, external variables such as seasonality affect the rate of bodily decomposition, but not the overall level of putrefaction experienced by the hard tissue (Rodriguez and Bass 1983, Janaway 1996; Rodriguez 1997; Campobasso et al. 2001; Vass 2011; Zhou and Bayard 2011; Ferreira and Cunha 2013). Only processes that sufficiently reduce the level of putrefaction experienced by the hard tissue, such as rapid extraneous soft tissue loss, will affect bacterial bone bioerosion (Jans et al. 2004; Nielsen-Marsh et al. 2007).

A more plausible explanation for the differences in bioerosion between the two collections might be sought in the specific cemetery circumstances and corpse treatment. Although we do not have detailed information on variables such as depth of burial, use of coffins, and if embalming or postmortem was conducted, it came to our notice that burials from the cemetery of Capuchos, from where the recent skeletal remains were unearthed, has been subjected to additional treatment (pers comm Ana Paula Elias). A compound made of bacteria and enzymes is routinely employed to accelerate body decomposition. Currently, Tanzyme is used but other types of accelerator may have been employed when the remains included in this study were buried. Possibly, the mixture was efficient enough in its acceleration of soft tissue decomposition to impede the gut bacteria activity on the individuals’ hard tissue. This could explain the limited levels of bioerosion present in the bone samples, regardless of the fact the material had been buried. Previous research on archaeological and experimentally buried remains indicated that when soft tissue is absent or removed, bioerosion is limited (Jans et al. 2004; Nielsen-Marsh et al. 2007; White and Booth 2014; Booth et al. 2015). A similar scenario might have affected the level of bioerosion in the skeletal remains from Capuchos cemetery.

To our knowledge, no scientific research has been carried out on the effect of decomposition accelerators on soft tissue decomposition of buried human remains. However, a small-scale exploratory research project with surface-exposed pig corpses decomposing under aerobic conditions found no clear acceleration of soft tissue decomposition (Morgado 2018). Possibly, in such cases, introduced microorganisms outcompete those who are intrinsic, with the overall rate of bioerosion not changing significantly. More research is therefore needed to enlighten the effect of such accelerators on the manifestation of bioerosion. Our results emphasise the importance of having detailed knowledge on the background of osteological collections of human remains used for experimental studies, since factors such as these might have severe effect on the condition and preservation of human remains and therefore can significantly affect research results. This also holds for premodern collections, since, for example, quicklime is known to have been used to cover burials in the past and has demonstrated to affect putrefaction time (Schotsmans et al. 2012, 2014; Van Strydonck et al. 2015). The effect of such practices on bioerosion should therefore carefully be considered as well investigated.

The level of bioerosion might also be influenced by the type and region of bone we chose. The femur was deemed to be close enough to the gut in the previous work to record bioerosion (Jans et al. 2004), as also indicated by the samples from the archaeological human remains in this study. However, bones with substantial amounts of trabecular bone are in general known to be more susceptible to bacterial bioerosion than those composed predominantly of cortical bone (Hanson and Buikstra 1987, Jans et al. 2004, White and Booth 2014; Booth and Madgwick 2016). Anatomical proximity to the gut as the potential source of osteolytic bacteria has also been suggested as an influential factor affecting intraskeletal diagenesis (Jans et al. 2004). It is possible that when bioerosion activity is limited due to other (burial/environmental) circumstances, the femora are not as highly affected as other areas of the body, namely those closer to the gut. To confirm this, tests should be performed sampling different areas of the same skeleton. For example, rib and cranial fragments are also easily retrieved and recognisable in cremation assemblages (Lemmers 2012). Lower rib fragments are closely situated near the gut and might therefore be preferable, but the amount of cortical bone is limited. Alternatively, when sampling femoral fragments, it might be useful to sample these in the future from the upper region of the femur near the lesser trochanter, as opposed to midshaft fragments.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates that bioerosion remains visible in burnt remains and is not routinely obliterated by exposure to high temperatures. Its presence can therefore be used as an indicator of the likely pre-burning putrefaction of human remains. Bioerosion thus helps to answer the question of whether pre-cremation burial has taken place, which no other established criterion so far is entirely able to do (Gonçalves et al. 2015; Gonçalves and Pires 2017). Furthermore, our results suggest that bioerosion is more clearly visible in bones that were buried under regular decomposition conditions than those from corpses that were treated to accelerate decomposition of soft tissue. Hence, the level of bioerosion manifested in bone seems to be tightly correlated with the amount of soft tissue present during burial and decomposition (Jans et al. 2004; Nielsen-Marsh et al. 2007; White and Booth 2014; Booth et al. 2015). Additional factors such as local soil and climatic circumstances, seasonality and specific skeletal element and region may have contributed to the manifestation of bioerosion, but additional studies are necessary to confirm the level of contribution of each factor.

Bioerosion analyses of burnt skeletal remains have significant potential for archaeological mortuary analysis. Besides allowing the reconstruction of the chaîne opératoire producing funerary assemblages involving burnt remains, this kind of analysis may also potentially provide insights about the combined use of fire and skeletal remains for other purposes; for example, the use of bones as hearth fuel (Théry-Parisot 2002; Cain 2005) and the fabrication of personal ornaments with burnt bones and teeth (Sanchez et al. 2014). The pre-burning condition of the raw material used in those tasks can give us new information about the ways in which past populations interacted with the dead.

The potential of bioerosion analysis of burnt remains is significant for interpreting mortuary rituals in archaeological contexts. The increasing recognition of complex and extended practices of bodily engagement in the archaeological record (e.g. Appleby 2013; Booth et al. 2015) emphasises the need to refine the methods used to identify such practices. Furthermore, the applicability of bioerosion analysis of burnt remains also extends to forensic science. Human remains can be exposed to fires in many situations, such as accidents and homicides (Fairgrieve 2007), and can even become burnt despite being buried due to surface fires (Stiner et al. 1995; Bennett 1999). Apart from exposure to heat being the cause of death, fire is a common method for attempting to conceal evidence of criminal activity inflicted on human victims. In such scenarios, human remains might be subject to a process of decay preceding heat exposure.

Bioerosion can be used as a criterion for detecting pre-burning funerary deposition of forensic human remains as well as the kind of environment in which such remains have been held prior to heat exposure. For that purpose, the process of bioerosion itself needs to be explored further with bone from different environmental contexts in order to better understand the factors affecting its presence and rate. In relation to this, our results highlight the caution that is required when using osteological collections for experimental research, since local cemetery conditions and corpse treatment can have significant effects on hard tissue preservation.

References

Appleby, J. (2013). Temporality and the transition to cremation in the late third millennium to mid second millennium BC in Britain. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 23(1), 83–97.

Baby, R. S. (1954). Hopewell cremation practices (no. 1). Columbus: Ohio Historical Society.

Balzer, A., Gleixner, G., Grupe, G., Schmidt, H. L., Schramm, S., & Turban-Just, S. (1997). In vitro decomposition of bone collagen by soil bacteria: the implications for stable isotope analysis in archaeometry. Archaeometry, 39(2), 415–429.

Bell, L. S., Skinner, M. F., & Jones, S. J. (1996). The speed of post mortem change to the human skeleton and its taphonomic significance. Forensic Science International, 82(2), 129–140.

Bennett, J. L. (1999). Thermal alteration of buried bone. Journal of Archaeological Science, 26(1), 1–8.

Binford, L. R. (1963). An analysis of cremations from three Michigan sites. Wisconsin Archaeologist, 44(2), 98–110.

Booth, T. J. (2016). An investigation into the relationship between funerary treatment and bacterial bioerosion in European archaeological human bone. Archaeometry, 58(3), 484–499.

Booth, T. J., & Madgwick, R. (2016). New evidence for diverse secondary burial practices in Iron Age Britain: a histological case study. Journal of Archaeological Science, 67, 14–24.

Booth, T. J., Chamberlain, A. T., & Pearson, M. P. (2015). Mummification in Bronze Age Britain. Antiquity, 89(347), 1155–1173.

Bradtmiller, B., & Buikstra, J. E. (1984). Effects of burning on human bone microstructure: a preliminary study. Journal of Forensic Science, 29(2), 535–540.

Brain, C. K. (1993). The occurrence of burnt bones at Swartkrans and their implications for the control of fire by early hominids. In C. K. Brain (Ed.), Swartkrans: A cave’s chronicle of early man (pp. 229–242). Praetoria: Transvaal Museum.

Brönnimann, D., Portmann, C., Pichler, S. L., Booth, T. J., Röder, B., Vach, W., Schibler, J., & Rentzel, P. (2018). Contextualising the dead–combining geoarchaeology and osteo–anthropology in a new multi-focus approach in bone histotaphonomy. Journal of Archaeological Science, 98, 45–58.

Buikstra, J., & Swegle, M. (1989). Bone modification due to burning: experimental evidence. In R. Bonnichsen & M. H. Sorg (Eds.), Bone modification (pp. 247–258). Orono: Center for the Study of the first Americans.

Cain, C. R. (2005). Using burned animal bone to look at Middle Stone Age occupation and behavior. Journal of Archaeological Science, 32(6), 873–884.

Campobasso, C. P., Di Vella, G., & Introna, F. (2001). Factors affecting decomposition and Diptera colonization. Forensic Science International, 120(1–2), 18–27.

Cattaneo, C., DiMartino, S., Scali, S., Craig, O. E., Grandi, M., & Sokol, R. J. (1999). Determining the human origin of fragments of burnt bone: a comparative study of histological, immunological and DNA techniques. Forensic Science International, 102(2–3), 181–191.

Child, A. M. (1995a). Microbial taphonomy of archaeological bone. Studies in Conservation, 40(1), 19–30.

Child, A. M. (1995b). Towards an understanding of the microbial decomposition of archaeological bone in the burial environment. Journal of Archaeological Science, 22, 165–174.

Collins, M. J., Riley, M. S., Child, A. M., & Turner-Walker, G. (1995). A basic mathematical simulation of the chemical degradation of ancient collagen. Journal of Archaeological Science, 22, 175–183.

Duday, H. (2006). L’archéothanatologie ou l’archéologie de la mort (Archaeothanatology or the archaeology of death). In R. Gowland & C. Knüsel (Eds.), The social archaeology of funerary remains (pp. 30–56). Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Duday, H., & Guillon, M. (2006). Understanding the circumstances of decomposition when the body is skeletonized. In A. Schmitt, E. Cunha, & J. Pinheiro (Eds.), Forensic Anthropology and Medicine (pp. 117–157). Humana Press Incorporated. Totowa, NJ.

Duday, H., Cipriani, A. M., & Pearce, J. (2009). The archaeology of the dead: lectures in archaeothanatology (Vol. 3). Oxford: Oxbow.

Etxeberria, F. (1994). Aspectos macroscópicos del hueso sometido al fuego. Revisión de las cremaciones descritas en el País Vasco desde la Arqueología. Munibe Antropologia-Arkeologia, 46, 111–116.

Fairgrieve, S. I. (2007). Forensic cremation recovery and analysis. Boca Raton: CRC press.

Fernández Castillo, R., Ubelaker, D. H., Acosta, J. A. L., & de La Fuente, G. A. C. (2013a). Effects of temperature on bone tissue. Histological study of the changes in the bone matrix. Forensic Science International., 226(1–3), 33–37.

Fernández Castillo, R., Ubelaker, D. H., Acosta, J. A. L., La Rosa, R. J. E., & de Garcia, I. G. (2013b). Effect of temperature on bone tissue: histological changes. Journal of Forensic Science, 58(3), 578–582.

Fernández-Jalvo, Y., Andrews, P., Pesquero, D., Smith, C., Marín-Monfort, D., Sánchez, B., Geigl, E.-M., & Alonso, A. (2010). Early bone diagenesis in temperate environments: Part I: Surface features and histology. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 288(1–4), 62–81.

Ferreira, M. T., & Cunha, E. (2013). Can we infer post mortem interval on the basis of decomposition rate? A case from a Portuguese cemetery. Forensic Science International, 226(1), 298.e1–298.e6.

Ferreira, M. T., Vicente, R., Navega, D., Gonçalves, D., Curate, F., & Cunha, E. (2014). A new forensic collection housed at the University of Coimbra, Portugal: the 21st century identified skeletal collection. Forensic Science International, 245, 202–2e1.

Forbes, G. (1941). The effects of heat on the histological structure of bone. Police Journal, 14(1), 50–60.

Garland, A. N. (1987). A histological study of archaeological bone decomposition. In A. Boddington, A. N. Garland, & R. C. Janaway (Eds.), Death, decay and reconstruction. Approaches to archaeology and forensic science (pp. 109–126). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Garland, A. N. (1993). An introduction to the histology of exhumed mineralized tissue. In G. Grupe & A. N. Garland (Eds.), Histology of ancient human bone: methods and diagnosis (pp. 1–16). New York: Springer.

Gill-King, H. (1997). Chemical and ultrastructural aspects of decomposition. In W. D. Haglund & M. H. Sorg (Eds.), Forensic taphonomy: the postmortem fate of human remains (pp. 93–108). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Gonçalves, D., & Pires, A. E. (2017). Cremation under fire: a review of bioarchaeological approaches from 1995 to 2015. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 9(8), 1677–1688.

Gonçalves, D., Thompson, T. J. U., & Cunha, E. (2011). Implications of heat-induced changes in bone on the interpretation of funerary behaviour and practice. Journal of Archaeological Science, 38(6), 1308–1313.

Gonçalves, D., Cunha, E., & Thompson, T. J. U. (2015). Estimation of the pre-burning condition of human remains in forensic contexts. International Journal of Legal Medicine, 129(5), 1137–1143.

Grévin, G. (1990). La fouille en laboratoire des sépultures à incinération : son apport à l'archéologie. Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris, 2(3–4), 67–74.

Grine, F. E., Bromage, T. G., Daegling, D. J., Burr, D. B., & Brain, C. K. (2015). Microbial osteolysis in an early Pleistocene hominin (Paranthropus robustus) from Swartkrans, South Africa. Journal of Human Evolution, 85, 126–135.

Grosskopf, B. (2004). Leichenbrand - Biologisches und kulturhistorisches Quellenmaterial zur Rekonstruktion vor-und frühgeschichtlicher Populationen und ihrer Funeralpraktiken. Unpublished PhD dissertation: University of Leipzig.

Grupe, G., & Dreses-Werringloer, U. (1993). Decomposition phenomena in thin sections of excavated human bones. In G. Grupe & A. D. Garland (Eds.), Histology of ancient human bone: methods and diagnosis (pp. 27–36). Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg.

Hackett, C. J. (1981). Microscopical focal destruction (tunnels) in exhumed human bones. Medicine, Science and the Law, 21, 243–265.

Hanson, D. B., & Buikstra, J. E. (1987). Histomorphological alteration in buried human bone from the lower Illinois Valley: implications for palaeodietary research. Journal of Archaeological Science, 14(5), 549–563.

Hanson, M., & Cain, C. R. (2007). Examining histology to identify burned bone. Journal of Archaeological Science, 34(11), 1902–1913.

Haynes, S., Searle, J. B., Bretman, A., & Dobney, K. M. (2002). Bone preservation and ancient DNA: the application of screening methods for predicting DNA survival. Journal of Archaeological Science, 29(6), 585–592.

Hedges, R. E. (2002). Bone diagenesis: an overview of processes. Archaeometry, 44(3), 319–328.

Hedges, R. E., Millard, A. R., & Pike, A. W. G. (1995). Measurements and relationships of diagenetic alteration of bone from three archaeological sites. Journal of Archaeological Science, 22(2), 201–209.

Henderson, J., Janaway, R. C., & Richards, J. R. (1987). Cremation slag: a substance found in funerary urns. In A. Boddington, A. N. Garland, & R. C. Janaway (Eds.), Death, decay and reconstruction: approaches to archaeology and forensic science (pp. 81–100). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Herrmann, B. (1977). On histological investigations of cremated human remains. Journal of Human Evolution, 6(2), 101–103.

Hollund, H. I., Arts, N., Jans, M. M. E., & Kars, H. (2015). Are teeth better? Histological characterization of diagenesis in archaeological bone–tooth pairs and a discussion of the consequences for archaeometric sample selection and analyses. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 25(6), 901-–911.

Hollund, H. I., Jans, M. M. E., Collins, M. J., Kars, H., Joosten, I., & Kars, S. M. (2012). What happened here? Bone histology as a tool in decoding the postmortem histories of archaeological bone from Castricum, The Netherlands. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 22(5), 537–548.

Hummel, S., & Schutkowski, H. (1993). Approaches to the histological age determination of cremated human remains. In G. Grupe & A. N. Garland (Eds.), Histology of ancient human bone. Methods and diagnosis (pp. 111–123). Berlin: Springer.

Jackes, M., Sherburne, R., Lubell, D., Barker, C., & Wayman, M. (2001). Destruction of microstructure in archaeological bone: a case study from Portugal. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 11, 415–432.

Janaway, R. C. (1996). The decay of buried human remains and their associated materials. Studies in crime: an introduction to forensic archaeology, 58, 85.

Jans, M. M. E. (2005). Histological characterisation of diagenetic alteration of archaeological bone. Amsterdam: Institute for Geo and Bioarchaeology.

Jans, M.M.E. (2014). Microscopic Destruction of Bone. In J. T. Pokines & S. A. Symes (Eds.), Manual of Forensic Taphonomy (pp. 19–36). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Jans, M. M. (2008). Microbial bioerosion of bone – a review. In M. Wisshak & L. Tapanila (Eds.), Current developments in bioerosion (pp. 397–413). Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg.

Jans, M. M. (2013). Microscopic destruction of bone. In J. Pokines & S. A. Symes (Eds.), Manual of forensic taphonomy (pp. 19–36). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Jans, M. M. E., Nielsen-Marsh, C. M., Smith, C. I., Collins, M. J., & Kars, H. (2004). Characterisation of microbial attack on archaeological bone. Journal of Archaeological Science, 31(1), 87–95.

Kendall, C., Eriksen, A. M. H., Kontopoulos, I., Collins, M. J., & Turner-Walker, G. (2018). Diagenesis of archaeological bone and tooth. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 491, 21–37.

Knüsel, C. J., & Robb, J. (2016). Funerary taphonomy: an overview of goals and methods. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 10, 655–673.

Kontopoulos, I., Nystrom, P., & White, L. (2016). Experimental taphonomy: post-mortem microstructural modifications in Sus scrofa domesticus bone. Forensic Science International, 266, 320–328.

Lemmers, S. A. M. (2012). Burned culture: osteological research into Urnfield cremation technology and ritual in the south of the Netherlands, LUNULA. Archaeologia Protohistorica, 20, 81–88.

Lemmers, S. A. M., Janssen, M., Waters-Rist, A., Grosskopf, B., Hoogland, H., Amkreutz, L.. (2012). The chieftain of Oss: new perspectives on an Iron-Age individual with DISH. Poster presentation at the 19th PPA, Lille.

Manhein, M. H. (1997). Decomposition rates of deliberate burials: a case study of preservation. In W. D. Haglund & M. H. Sorg (Eds.), Forensic taphonomy: the postmortem fate of human remains (pp. 469–482). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Mann, R. W., Bass, W. M., & Meadows, L. (1990). Time since death and decomposition of the human body: variables and observations in case and experimental field studies. Journal of Forensic Science, 35(1), 103–111.

Mays, S. (1998). The archaeology of human bones. London: Routledge.

Meyer, J., Anderson, B., & Carter, D. O. (2013). Seasonal variation of carcass decomposition and gravesoil chemistry in a cold (Dfa) climate. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 58(5), 1175–1182.

Millard, A. (2001). The deterioration of bone. In D. R. Brothwell & A. M. Pollard (Eds.), Handbook of archaeological sciences (pp. 637–647). London: Wiley.

Morgado, R. A. G. (2018). Inumação em modelos de comsumpção aeróbica: estudo tafonómico das consequências da utilização de caixão e acelerador enzimático na decomposição. Coimbra: University of Coimbra.

Nielsen-Marsh, C. M., Smith, C. I., Jans, M. M. E., Nord, A., Kars, H., & Collins, M. J. (2007). Bone diagenesis in the European Holocene II: Taphonomic and environmental considerations. Journal of Archaeological Science, 34(9), 1523–1531.

Oliveira-Santos, I., Gouveia, M., Cunha, E., & Gonçalves, D. (2017). The circles of life: age at death estimation in burnt teeth through tooth cementum annulations. International Journal of Legal Medicine, 131(2), 527–536.

Ottoni, C., Koon, H. E., Collins, M. J., Penkman, K. E., Rickards, O., & Craig, O. E. (2009). Preservation of ancient DNA in thermally damaged archaeological bone. Naturwissenschaften, 96(2), 267–278.

Pearson, M. P., Chamberlain, A., Craig, O., Marshall, P., Mulville, J., Smith, H., Chenery, C., Collins, M., Cook, G., Craig, G., Evans, J., Hiller, J., Montgomery, J., Schwenninger, J.-L., Taylor, G., & Wess, T. (2005). Evidence for mummification in Bronze Age Britain. Antiquity, 79(305), 529–546.

Piepenbrink, H. (1984). Examples of signs of biogenic decomposition in bones long buried. Anthropologischer Anzeiger; Bericht uber die biologisch-anthropologische Literatur, 42(4), 241–251.

Piepenbrink, H. (1986). Two examples of biogenous dead bone decomposition and their consequences for taphonomic interpretation. Journal of Archaeological Science, 13(5), 417–430.

Piepenbrink, H., & Schutkowski, H. (1987). Decomposition of skeletal remains in desert dry soil a roentgenological study. Human Evolution, 2(6), 481–491.

Ramos, T. B., Horta, A., Gonçalves, M. C., Pires, F. P., Duffy, D., & Martins, J. C. (2017). The INFOSOLO database as a first step towards the development of a soil information system in Portugal. Catena, 158, 390–412.

Rodriguez, W. C. (1997). Decomposition of buried and submerged bodies. In W. D. Haglund & M. H. Sorg (Eds.), Forensic taphonomy: the postmortem fate of human remains (pp. 459–468). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Rodriguez, W. C., & Bass, W. M. (1983). Insect activity and its relationship to decay rates of human cadavers in East Tennessee. Journal of Forensic Science, 28(2), 423–432.

Roksandic, M. (2002). Position of skeletal remains as a key to understanding mortuary behavior. In W. D. Haglund & M. H. Sorg (Eds.), Advances in forensic taphonomy: method, theory, and archaeological perspectives (pp. 99–117). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Sanchez, G., Holliday, V. T., Gaines, E. P., Arroyo-Cabrales, J., Martínez-Tagüeña, N., Kowler, A., & Sanchez-Morales, I. (2014). Human (Clovis)-gomphothere (Cuvieronius sp.) association∼ 13,390 calibrated yBP in Sonora, Mexico. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(30), 10972–10977.

Schotsmans, E. M., Denton, J., Dekeirsschieter, J., Ivaneanu, T., Leentjes, S., Janaway, R. C., & Wilson, A. S. (2012). Effects of hydrated lime and quicklime on the decay of buried human remains using pig cadavers as human body analogues. Forensic Science International, 217(1–3), 50–59.

Schotsmans, E. M., Fletcher, J. N., Denton, J., Janaway, R. C., & Wilson, A. S. (2014). Long-term effects of hydrated lime and quicklime on the decay of human remains using pig cadavers as human body analogues: field experiments. Forensic Science International, 238, 141–1e1.

Schultz, M. (1986). Die mikroskopische Untersuchung prähistorischer Skeletfunde: Anwendung und Aussagemöglichkeiten der differentialdiagnostischen Untersuchung in der Paläopathologie. Liestal: Amt für Museen und Archäologie BL.

Simmons, T., Cross, P. A., Adlam, R. E., & Moffatt, C. (2010). The influence of insects on decomposition rate in buried and surface remains. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 55(4), 889–892.

Smith, C. I., Nielsen-Marsh, C. M., Jans, M. M. E., & Collins, M. J. (2007). Bone diagenesis in the European Holocene I: patterns and mechanisms. Journal of Archaeological Science, 34(9), 1485–1493.

Smith, M. J., Allen, M. J., Delbarre, G., Booth, T., Cheetham, P., Bailey, L., O’Malley, F., Parker Pearson, M., & Green, M. (2016). Holding on to the past: Southern British evidence for mummification and retention of the dead in the chalcolithic and bronze age. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 10, 744–756.

Sosa, C., Vispe, E., Núñez, C., Baeta, M., Casalod, Y., Bolea, M., Hedges, R. E. M., & Martinez-Jarreta, B. (2013). Association between ancient bone preservation and DNA yield: a multidisciplinary approach. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 151(1), 102–109.

Spennemann, D. H., & Colley, S. M. (1989). Fire in a pit: the effects of burning on faunal remains. Archaeozoologia, 3(1–2), 51–64.

Squires, K. E., Thompson, T. J., Islam, M., & Chamberlain, A. (2011). The application of histomorphometry and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy to the analysis of early Anglo-Saxon burned bone. Journal of Archaeological Science, 38(9), 2399–2409.

Stiner, M. C., Kuhn, S. L., Weiner, S., & Bar-Yosef, O. (1995). Differential burning, recrystallization, and fragmentation of archaeological bone. Journal of Archaeological Science, 22(2), 223–237.

Symes, S. A., Rainwater, C. W., Chapman, E. N., Gipson, D. R., & Piper, A. L. (2008). Patterned thermal destruction of human remains in a forensic setting. In C. W. Schmidt & S. A. Symes (Eds.), The analysis of burned human remains (pp. 15–vi). London: Academic Press.

Symes, S. A., L’abbé, E. N., Pokines, J. T., Yuzwa, T., Messer, D., Stromquist, A., & Keough, N. (2014). Thermal alteration to bone. Manual of forensic taphonomy (pp. 367–402). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Théry-Parisot, I. (2002). Fuel management (bone and wood) during the Lower Aurignacian in the Pataud rock shelter (Lower Palaeolithic, Les Eyzies de Tayac, Dordogne, France). Contribution of experimentation. Journal of Archaeological Science, 29(12), 1415–1421.

Tjelldén, A. K., Kristiansen, S. M., Birkedal, H., & Jans, M. M. (2018). The pattern of human bone dissolution - a histological study of Iron Age warriors from a Danish wetland site. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 28(4), 407–418.

Turner-Walker, G. (2012). Early bioerosion in skeletal tissues: persistence through deep time. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie – Abhandungen, 265(2), 165–183.

Turner-Walker, G., & Jans, M. (2008). Reconstructing taphonomic histories using histological analysis. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 266(3–4), 227–235.

Turner-Walker, G., & Syversen, U. (2002). Quantifying histological changes in archaeological bones using BSE–SEM image analysis. Archaeometry, 44(3), 461–468.

Turner-Walker, G., Nielsen-Marsh, C. M., Syversen, U., Kars, H., & Collins, M. J. (2002). Sub-micron spongiform porosity is the major ultra-structural alteration occurring in archaeological bone. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 12(6), 407–414.

van den Bos, R. P. M., & Maat, G. J. (2002). Cremated remains from a roman burial site in Tiel-Passewaaij (Gelderland). Barge's Anthropologica, Leiden University Medical Center. Leiden: Barge’s Anthropologica.

Van Strydonck, M., Decq, L., den Brande, T. V., Boudin, M., Ramis, D., Borms, H., & De Mulder, G. (2015). The protohistoric ‘quicklime burials’ from the Balearic Islands: cremation or inhumation. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 25(4), 392–400.

Vass, A. A. (2011). The elusive universal post-mortem interval formula. Forensic science international, 204(1–3), 34–40.

Vassalo, A. R., Cunha, E., Batista de Carvalho, L. A. E., & Gonçalves, D. (2016). Rather yield than break: assessing the influence of human bone collagen content on heat-induced warping through vibrational spectroscopy. International Journal of Legal Medicine, 130(6), 1647–1656.

Vassalo, A., Mamede, A., Ferreira, M. T., Cunha, E., & Gonçalves, D. (2019). The G-force awakens: the influence of gravity in bone heat-induced warping and its implications for the estimation of the pre-burning condition of human remains. Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences, 51(2), 201–208.

Wahl, J., & Kokabi, M. (1988). Das Römische Graberfeld von Stettfeld I. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag.

Wedl, C. (1864). Über einen im Zahnbein und Knochen keimenden Pilz. Sitzungsber. Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien, 50, 171–192.

White, L., & Booth, T. J. (2014). The origin of bacteria responsible for bioerosion to the internal bone microstructure: results from experimentally-deposited pig carcasses. Forensic Science International, 239, 92–102.

Whyte, T. (2001). Distinguishing remains of human cremations from burned animal bones. Journal of Field Archaeology, 28(3/4), 437–448.

Wilson, A. S., Taylor, T., Ceruti, M. C., Chavez, J. A., Reinhard, J., Grimes, V., Meier-Augenstein, W., Cartmell, L., Stern, B., Richards, M. P., Worobey, M., Barnes, I., & Gilbert, M. T. P. (2007). Stable isotope and DNA evidence for ritual sequences in Inca child sacrifice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 16456e16461.

Zhou, C., & Bayard, R. W. (2011). Factors and processes causing accelerated decomposition in human cadavers - an overview. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 18(1), 6–9.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the Hard Tissues Laboratory of the University of Coimbra and especially Claudia Brites for helping us in making the first set of thin sections, and the Skeletal Biology Research Centre at the University of Kent, led by Patrick Mahoney, for allowing us to use their facilities for preparing the second set of samples. We are grateful to Tom Booth for providing training in the identification and characterisation of bioerosion and for kindly reading and commenting on a draft of this paper. We thank Professor Ana Maria Silva for providing us with samples from the Hospital de Santo António and Dr. Inês Oliveira-Santos for valuable advices regarding the histological analysis. We thank Dr. Sven Geissler and Dr. Janosch Schoon of the Julius Wolff Institute for Biomechanics and Musculoskeletal Regeneration, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, for providing feedback and access to microscopy facilities.

Funding

We acknowledge Leicester University for providing us with financial support enabling the training in bioerosion recognition, as well as for the initial research visit to Coimbra. The authors additionally acknowledge the following financial support by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology and COMPETE 2020 program (SFRH/BPD/84268/2012; PTDC/IVC-ANT/1201/2014 & POCI-01-0145-FEDER-016766; PEst-OE/SADG/UI0283/2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was initially conceived and designed by Jo Appleby and subsequently refined through discussions between all of the authors. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Simone Lemmers, David Gonçalves and Ana Vassalo; analysis was carried out by Simone Lemmers. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Simone Lemmers and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Statement

Full ethical approval for the research was obtained from the University of Leicester. Portuguese ordinance no. 411/98 of December 30 permits non-judiciary exhumations 3 years after the inhumation provided that the body is fully skeletonised. If unclaimed, skeletons stay under the tutelage of the cemetery. The Cemetery of Capuchos donated the skeletons to the University of Coimbra and samples used in this research were taken from those unclaimed skeletons.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(PDF 14375 kb).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lemmers, S.A.M., Gonçalves, D., Cunha, E. et al. Burned Fleshed or Dry? The Potential of Bioerosion to Determine the Pre-Burning Condition of Human Remains. J Archaeol Method Theory 27, 972–991 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-020-09446-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-020-09446-x