Abstract

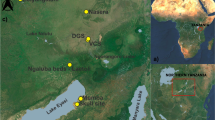

The combination of bifacial percussion and pressure flaking to make stone tools was repeatedly invented in prehistory. Bifacial percussion and pressure technology is well documented in North America, Europe, Africa, and Asia, but a separate and poorly understood center of innovation occurred in the Kimberley Region of Northwest Australia. Stone points first appeared there ca 4.5 kya and bifacial Kimberley Points emerged by ca 1.4 kya. Aboriginal flintknappers made Kimberley Points using traditional methods until the recent past. This study analyzes stone artifacts from 335 sites in the remote Northwest Kimberley and documents a sophisticated bifacial technology that involved seven “tactical sets”—four of them exclusive to manufacturing these points—applied in five strategic phases. It is proposed that bifacial thinning ultimately arose in response to social forces operating across Kimberley Aboriginal societies in response to demographic pressures from neighboring Aboriginal groups. The repeated invention of bifacial flaking in prehistory may be related to the messaging made possible by the manufacturing approach itself—both in virtuoso technical performance and the flexible way bifacial performances could be distributed across the natural and social landscape.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

“Bifacial” is used here in the conventional sense of flaking a stone on both sides from one edge (after Inizan et al. 1999:130), and “unifacial” refers to flaking on one side from one edge. This differs from some Australian studies, where “bifacial” is also used for points that have unifacial flaking to opposite sides on opposite edges (i.e., “reverse-edge trimmed”; Attenbrow et al. 1995:112; Flood 1970:43).

“Kimberley Point” is used in some studies to refer to points with invasive pressure flaking and serrated edges. This study will show that a key aspect of late prehistoric Kimberley Point technology is blank preparation by invasive bifacial percussion thinning; the typological label refers to these variants.

The term “technique” is variably defined by archaeologists to refer to individual flake removals (e.g., hard-hammer percussion technique) or multiple integrated sets of flake removals (e.g., Levallois technique). “Method” can also refer to sets of flake removals to achieve limited goals but is often used interchangeably with “technique”. In this study, technique refers to individual flake removals.

An analyst refers to their own technical knowledge to pattern-match stone artifacts and to infer the plan of action. A nonknapper/analyst’s technical knowledge is literal and derived from publications and perhaps videos, and a knapper/analyst’s technical knowledge also includes kinesthetic know-how gained through experience. An analyst’s technical knowledge is not equivalent to ancient technical knowledge because analysts do not work within past activity systems; conversely, the analytical process cannot recreate the technical knowledge of ancient craftspeople. Indeed, although analysts reconstruct some aspects of ancient technical knowledge, they do not recreate it in an “emic” sense nor is that usually considered a goal of lithic analysis (however, see Tostevin 2011).

Falkenberg (1962) refers to male preinitiation age-grade statuses universal among Aboriginal groups east of the Kimberley near Port Keats. Very young girls and boys were not socially differentiated, but boys were recognized as “a male being” at about age six when “he begins with boys’ games, practices spear-throwing, and tries to imitate adult men” (1962:179–180). In the Kimberley, very young boys were provided with toy spears made by a parent or mother’s brother (Kaberry 1939:66), perhaps reflecting a similar pattern there.

References

Aiston, G. (1928). Chipped stone tools of the Aboriginal tribes east and north-east of Lake Eyre, South Australia. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, 1928, 123–131.

Akerman, K. (1976). An analysis of stone implements from Quondong, Western Australia. Occasional Papers in Anthropology, 6, 108–116. University of Queensland.

Akerman, K. (1978). Notes on the Kimberley stone-tipped spear, focussing on the hafting mechanism. Mankind, 11(4), 486–489.

Akerman, K. (1979a). Heat and lithic technology in the Kimberleys, W.A. Archaeology and Physical Anthropology in Oceania, 14, 144–151.

Akerman, K. (1979b). Honey in the life of the Aboriginals of the Kimberleys. Oceania, 49(3), 169–178.

Akerman, K. (1979c). Flaking stone with wooden tools. Artefact, 4(3 and 4), 79–80.

Akerman, K. (1980). Material culture and trade in the Kimberleys today. In R. M. Berndt & C. H. Berndt (Eds.), Aborigines of the west, their past and their present (pp. 243–251). Perth: University of Western Australia Press.

Akerman, K. (1995). Tradition and change in aspects of contemporary Australian Aboriginal religious objects. In C. Anderson (Ed.), Politics of the secret (pp. 43-50). Oceania Monograph 45.

Akerman, K. (2006). High tech—low tech: Lithic technology in the Kimberley Region of Western Australia. In J. Apel and K. Knutsson (Eds.), Skilled production and social reproduction (pp. 323–346). Societas Archaeologica Upsaliensis Stone Studies 2, Uppsala, Sweden.

Akerman, K. (2007). To make a point: ethnographic reality and the ethnographic and experimental replication of Australian macroblades known as leilira. Australian Archaeology, 64, 23–34.

Akerman, K. (2008). ‘Missing the point’ or ‘what to believe—the theory or the data’: rationales for the production of Kimberley Points. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 2008(2), 70–79.

Akerman, K., & Bindon, P. (1983). Evidence of Aboriginal lithic experimentation on the Dampierland Peninsula. In M. Smith (Ed.), Archaeology at ANZAAS 1983 (pp. 75–80). Perth: Western Australian Museum.

Akerman, K., & Bindon, P. (1995). Dentate and related stone biface points from Northern Australia. The Beagle, Records of the Museums and Art Galleries of the Northern Territory, 12, 89–99.

Akerman, K., Fullagar, R., & van Gijn, A. (2002). Weapons and wunan: production, function and exchange of Kimberley Points. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 1, 14–42.

Allen, H. (1997). The distribution of large blades: Evidence for recent changes in aboriginal ceremonial exchange networks. In P. McConvell & N. Evans (Eds.), Archaeology and linguistics: Aboriginal Australia in global perspective (pp. 357–376). Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Allen, H, & Barton, G. (1989). Ngarradj warde djobkeng, white cockatoo dreaming and the prehistory of Kakadu. Oceania Monograph No. 37.

Andrefsky, W., Jr. (2005), Lithics: Macroscopic approaches to analysis, 2nd edition. Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Apel, J. (2008). Knowledge, know-how and raw material—the production of Late Neolithic flint daggers in Scandinavia. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 15, 91–111.

Attenbrow, V., David, B., & Flood, J. (1995). Mennge-ya and the origins of points: new insights into the appearance of points in the semi-arid zone of the Northern Territory. Archaeology in Oceania, 30, 105–120.

Aubert, M. (2012). A review of rock art dating in the Kimberley, Western Australia. Journal of Archaeological Science, 39, 573–577.

Aubry, T., Almeida, M., Neves, M. J., & Walter, B. (2003). Solutrean laurel leaf point production and raw material procurement during the last glacial maximum in southern Europe: Two examples from central France and Portugal. In M. Soressi & H. L. Dibble (Eds.), Multiple approaches to the study of bifacial technologies (pp. 165–181). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Balfour, H. R. (1903). On the method employed by the natives of N. W. Australia in the manufacture of glass spear-heads. Man, 35, 65.

Balfour, H. R. (1951). A native tool kit from the Kimberley District, Western Australia. Mankind, 4(7), 273–274.

Bamforth, D. B., & Finlay, N. (2008). Introduction: archaeological approaches to lithic production skill and craft learning. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 15, 1–27.

Barton, C. M., Clark, G. A., & Cohen, A. E. (1994). Art as information: explaining Upper Palaeolithic art in Western Europe. World Archaeology, 26(2), 185–287.

Binford, L. R., & O’Connell, J. F. (1984). An Alyawara day: the stone quarry. Journal of Anthropological Research, 40, 406–432. Reprinted in Debating Archaeology, by Lewis R. Binford, 1989, pp. 121-146. Academic Press, New York.

Bleed, P. (2001). Trees or chains, links or branches: conceptual alternatives for consideration of stone tool production and other sequential activities. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 8(1), 101–127.

Bleed, P. (2008). Skill matters. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 15, 154–166.

Blundell, V. (1974). The Wandjina cave paintings of Northwest Australia. Arctic Anthropology, 11(Supplement), 213–223.

Blundell, V. (1980). Hunter-gatherer territoriality: ideology and behavior in Northwest Australia. Ethnohistory, 27(2), 103–117.

Blundell, V., & Layton, R. (1978). Marriage, myth and models of exchange in the West Kimberleys. Mankind, 11, 231–245.

Blundell, V., & Woolagoodja, D. (2005). Keeping the Wandjinas fresh: Sam Woolagoodja and the enduring power of Lalai. Freemantle: Fremantle Press.

Bowdler, S., & O’Connor, S. (1991). The dating of the Australian Small Tool Tradition, with new evidence from the Kimberley, WA. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 1, 53–62.

Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. J. (1985). Culture and the evolutionary process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bracken, M. (2004). Understanding flintknapping fundamentals. Saegertown: DVD. Bracken Bows Inc.

Bradley, B. (1993). Paleo-Indian flaked stone technology in the North American High Plains. In O. Soffer & N. D. Praslov (Eds.), From Kostenki to Clovis: Upper Paleolithic—Paleo-Indian adaptations (pp. 251–262). New York: Plenum Press.

Bradley, B. A., & Sampson, C. G. (1986). Analysis by replication of two Acheulian artefact assemblages. In G. N. Bailey & P. Callow (Eds.), Stone Age prehistory: Studies in memory of Charles McBurney (pp. 29–45). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bradley, B., & Stanford, D. (1987). The Claypool study. In G. C. Frison & L. C. Todd (Eds.), The Horner Site: The type site of the Cody cultural complex (pp. 405–434). Orlando: Academic Press.

Bradley, B. A., Akinovich, M., & Giria, E. (1995). Early Upper Palaeolithic in the Russian Plain: Streletskayan flaked stone artefacts and technology. Antiquity, 69, 989–998.

Bradley, B.A., Collins, M.B., & Hemmings, A. (2010). Clovis technology. International monographs in prehistory, Archaeological Series 17.

Brooks, A. S., Yellen, J. E., Nevell, L., & Hartman, G. (2005). Projectile technologies of the African MSA: Implications for modern human origins. In E. Hovers & S. Kuhn (Eds.), Transitions before the transition: Evolution and stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age (pp. 233–255). New York: Kluwer.

Brumm, A., & Moore, M. W. (2005). Symbolic revolutions and the Australian archaeological record. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 15(2), 157–175.

Burke, H., & Smith, C. (2004). The archaeologists field handbook. Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin.

Callahan, E. (1979). The basics of biface knapping in the eastern fluted point tradition: a manual for flintknappers and lithic analysts. Archaeology of Eastern North America, 7, 1–180.

Carnegie, D. W. (1898). Spinifex and sand: A narrative of five years’ pioneering and exploration in Western Australia. London: C. Arthur Pearson Limited.

Churchill, S. E., & Rhodes, J. A. (2009). The evolution of the human capacity for ‘killing at a distance’: The human fossil evidence for the evolution of projectile weaponry. In J.-J. Hublin & M. P. Richards (Eds.), The evolution of hominin diets: Integrating approaches to the study of palaeolithic subsistence (pp. 201–210). New York: Springer Science and Business Media.

Clark, J.E. (2002). Failure as truth: An autopsy of Crabtree’s Folsom experiments. In J.E. Clark, M.B. Collins (Eds.), Folsom technology and lifeways (pp. 191–208). Lithic Technology Special Publication No. 4. Department of Anthropology, University of Tulsa, Tulsa.

Clark, J. E. (2003). Craftmanship and craft specialization. In K. G. Hirth (Ed.), Mesoamerican lithic technology: Experimentation and interpretation (pp. 220–233). Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Clendon, M. (1999). Worora gender metaphors and Australian prehistory. Anthropological Linguistics, 41(3), 308–355.

Crabtree, D.E. (1972). An introduction to flintworking. Occasional Papers of the Idaho State University Museum, No. 28. Pocatello, Idaho.

Crawford, I. M. (1968). The art of the Wandjina. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Darmark, K. (2012). Surface pressure flaking in Eurasia: Mapping the innovation, diffusion and evolution of a technological element in the production of projectile points. In P. M. Desrosiers (Ed.), The emergence of pressure blade making: From origin to modern experimentation (pp. 261–283). New York: Springer.

David, B., & Lourandos, H. (1998). Rock art and socio-demography in northeast Australian prehistory. World Archaeology, 30(2), 193–219.

Davidson, D. S. (1934). Australian spear-traits and their derivations. Journal of the Polynesian Society, 43, 41–162 [only the first part].

Davidson, D. S. (1935). Archaeological problems of Northern Australia. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 65, 145–183.

Davidson, D. S., & McCarthy, F. D. (1957). The distribution and chronology of some important types of stone implements in Western Australia. Anthropos, 52, 391–458.

Davidson, I., Cook, N., Fischer, M., Ridges, M., Ross, J., & Sutton, S. (2005). Archaeology in another country: exchange and symbols in north west central Queensland. In I. Macfarlane, M.-J. Mountain, R. Paton [Eds.], Many exchanges: archaeology, history, community and the work of Isabel McBryde [pp. 103–130]. Aboriginal History Monograph 11, Canberra.

Dibble, H. L., & Whittaker, J. C. (1981). New experimental evidence on the relation between percussion flaking and flake variation. Journal of Archaeological Science, 8, 283–296.

Dobres, M.-A. (2000). Technology and social agency: Outlining a practice framework for archaeology. Oxford: Blackwell.

Dobres, M.-A. (2010). Archaeologies of technology. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 34, 103–114.

Donaldson, M. (2012a). Kimberley rock art, volume 1: Mitchell Plateau area. Mount Lawley: Wildrocks Publications.

Donaldson, M. (2012b). Kimberley rock art, volume 2: North Kimberley. Mount Lawley: Wildrocks Publications.

Donaldson, M., & Elliot, I. (2010). Brockman’s north-west Kimberley expedition, 1901. In C. Clement, J. Gresham, & H. McGlashan (Eds.), Kimberley history: People, exploration and development (pp. 183–193). Perth: Kimberley Society.

Donaldson, M., & Kenneally, K. (Eds.). (2007). Rock art of the Kimberley. Perth: Kimberley Society.

Doring, J. (2000). Gwion Gwion: Secret and sacred pathways of the Ngarinyin Aboriginal people of Australia. Köln: Könemann.

Dortch, C. E. (1977). Early and late stone industrial phases in Western Australia. In R. V. S. Wright (Ed.), Stone tools as cultural markers: Change, evolution and complexity (pp. 104–132). Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Dougherty, J. W. D., & Keller, C. M. (1982). Taskonomy: a practical approach to knowledge structures. American Ethnologist, 5, 763–774.

Elkin, A. P. (1930). Rock-paintings of north-west Australia. Oceania, 1, 257–279.

Elkin, A. P. (1948). Pressure flaking in the northern Kimberley, Australia. Man, 130, 110–113.

Evans, N., & Jones, R. (1997). The cradle of the Pama-Nyungans: Archaeological and linguistic speculations. In P. McConvell & N. Evans (Eds.), Archaeology and linguistics: Aboriginal Australia in global perspective (pp. 385–417). Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Falkenberg, J. (1962). Kin and totem: Group relations of Australian Aborigines in the Port Keats District. New York: Humanities Press.

Flenniken, J. J., & White, J. P. (1985). Australian flaked stone tools: a technological perspective. Records of the Australian Museum, 36, 131–151.

Flood, J. (1970). A point assemblage from the Northern Territory. Archaeology and Physical Anthropology in Oceania, 5, 27–53.

Gillespie, J. D. (2007). Enculturing an unknown world: caches and Clovis landscape ideology. Journal of Canadian Archaeology, 31, 171–189.

Gould, R. A. (1980). Living archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hardman, E. T. (1888). Notes on a collection of native weapons and implements from tropical Western Australia (Kimberley District). Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Third Series, 1(1), 57–69.

Harrison, R. (2002). Archaeology and the colonial encounter: Kimberley spearpoints, cultural identity and masculinity in the north of Australia. Journal of Social Archaeology, 2(3), 352–377.

Harrison, R. (2004). Kimberley points and colonial preference: new insights into the chronology of pressure flaked point forms from the southeast Kimberley, Western Australia. Archaeology in Oceania, 39, 1–11.

Head, L., & Fullagar, R. (1997). Hunter-gatherer archaeology and pastoral contact: perspectives from the northwest Northern Territory, Australia. World Archaeology, 28(3), 418–428.

Henrich, J., & Broesch, J. (2011). On the nature of cultural transmission networks: evidence from Fijian villages for adaptive learning biases. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 366, 1139–1148.

Hirth, K. G., Titmus, G. L., Flenniken, J. J., & Tixier, J. (2003). Alternative techniques for producing Mesoamerican-style pressure flaking patterns on obsidian bifaces. In K. G. Hirth (Ed.), Mesoamerican lithic technology: Experimentation and interpretation (pp. 147–152). Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Hiscock, P. (1994). The end of points. In M. Sullivan, S. Brockwell, & A. Webb (Eds.), Archaeology in the North: Proceedings of the 1993 Australian Archaeological Association Conference (pp. 72–83). Darwin: North Australia Research Unit.

Hiscock, P. (2007). Australian point and core reduction viewed through refitting. In M. de Bie & U. Schurman (Eds.), Fitting rocks: Lithic refitting examined (BAR international series 1596, pp. 105–118). Oxford: Archaeopress.

Hiscock, P. (2008). Archaeology of ancient Australia. London: Routledge.

Högberg, A., & Larsson, L. (2011). Lithic technology and behavioural modernity: new results from the Still Bay site, Hollow Rock Shelter, Western Cape Province, South Africa. Journal of Human Evolution, 61, 133–155.

Huntley, J., Aubert, M., Ross, J., Brand, H. E. A., & Morwood, M. J. (2013). One colour, (at least) two minerals: a study of mulberry art pigment and a mulberry pigment ‘quarry’ from the Kimberley, Northern Australia. Archaeometry. doi:10.1111/arcm.12073.

Idriess, I. (1937). Over the range: Sunshine and shadow in the Kimberleys. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

Ingold, T. (1993). The temporality of the landscape. World Archaeology, 25(2), 152–174.

Inizan, M.-L., Reduron-Ballinger, M., Roche, H., & Tixier, J. (1999), Technology and terminology of knapped stone, translated by Jehanne Féblot-Augustins. Préhistoire de la Pierre Taillée:5. Cercle de Recherches et d’Etudes Préhistoriques, Nanterre, France.

Jones, R., & Johnson, I. (1985), Deaf Adder Gorge: Lindner Site, Nauwalabila 1. In Archaeological research in Kakadu National Park (pp. 165-227). Special Publication 13. Canberra: Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service.

Jones, R., & White, N. (1988). Point blank: Stone tool manufacture at the Ngilipitji Quarry, Arnhem Land, 1981. In B. Meehan & R. Jones (Eds.), Archaeology with ethnography: An Australian perspective (pp. 51–93). Canberra: Department of Prehistory, Australian National University.

Justice, N. D. (1987). Stone Age spear and arrow points of the Midcontinental and Eastern United States: A modern survey and reference. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Justice, N. D. (2002). Stone Age spear and arrow points of California and the Great Basin. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Kaberry, P. (1939). Aboriginal woman: Sacred and profane. London: George Routledge and Sons Ltd.

Keller, C. M., & Keller, J. D. (1996). Cognition and tool use: The blacksmith at work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kelly, R. L. (1988). The three sides of a biface. American Antiquity, 53(4), 717–734.

King, P.P. (1827), Narrative of a survey of the coasts of Australia, 1818-1822. John Murray, London. Australiana Facsimile Editions No. 30 (1969), Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide.

Layton, R. (1985). The cultural context of hunter-gatherer rock art. Man, 20(3), 434–453.

Layton, R. (1992). Australian rock art: A new synthesis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lommel, A. (1997), The Unambal: a tribe in Northwest Australia. (Translation and reprint of Lommel, A. [1952] Die Unambal: Ein Stamm in Nordwest-Australien). Takarakka Nowan Kas Publications, Carnarvon Gorge.

Love, J. R. B. (1930). Rock paintings of the Worora and their mythological interpretation. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia, 16, 1–17.

Love, J. R. B. (1935). Mythology, totemism and religion of the Worora tribe of northwest Australia. Report of the Australian and New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science, 22, 222–231.

Love, J. R. B. (1951). Percussion flaking of adze blades in the Musgrave Ranges. Mankind, 4(7), 297–298.

Love, J.R.B. (2009), Kimberley people: Stone Age bushmen of today. (Reprint of Love, J.R.B. [1936] Stone-Age bushmen of to-Day: life and adventure among a tribe of savages in North-western Australia). Australian Aboriginal Culture Series 6, David M. Welch, Virginia, Northern Territory.

MacDonald, D. H. (2010). The evolution of Folsom fluting. Plains Anthropologist, 55(213), 39–54.

Mahony, D. J. (1924). Note on making spearheads in the Kimberley District, Western Australia. Australian Association for the Advancement of Science, 117, 474–475.

McBrearty, S., & Brooks, A. S. (2000). The revolution that wasn’t: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior. Journal of Human Evolution, 39, 453–563.

McDonald, J. (2005). Archaic faces to headdresses: The changing role of rock art across the arid zone. In P. Veth, M. Smith, & P. Hiscock (Eds.), Desert peoples: Archaeological perspectives (pp. 116–141). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

McGuigan, N. (2012). The role of transmission biases in the cultural diffusion of irrelevant actions. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 126(2), 150–160.

Mellars, P., Goric, K. C., Carre, M., Soaresg, P. A., & Richards, M. B. (2013). Genetic and archaeological perspectives on the initial modern human colonization of southern Asia. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(26), 10699–10704.

Mesoudi, A., & O’Brien, M. J. (2008a). The learning and transmission of hierarchical cultural recipes. Biological Theory, 3(1), 63–72.

Mesoudi, A., & O’Brien, M. J. (2008b). The cultural transmission of Great Basin projectile point technology I: an experimental simulation. American Antiquity, 73(1), 3–28.

Micha, F. J. (1970). Trade and change in Australian Aboriginal cultures: Australian Aboriginal trade as an expression of close culture contact and as a mediator of culture change. In A. R. Pilling & R. A. Waterman (Eds.), Diprotodon to detribalization: Studies of change among Australian Aborigines (pp. 285–313). East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

Moore, M. W. (2003). Australian Aboriginal blade production methods on the Georgina River, Camooweal, Queensland. Lithic Technology, 28, 35–63.

Moore, M. W. (2004). The tula adze: manufacture and purpose. Antiquity, 78(299), 61–73.

Moore, M. W. (2010). ‘Grammars of action’ and stone flaking design space. In A. Nowell & I. Davidson (Eds.), Stone tools and the evolution of human cognition (pp. 13–43). Boulder: University Press of Colorado.

Moore, M. W. (2013). Simple stone flaking in Australasia: patterns and implications. Quaternary International, 285, 140–149.

Morwood, M. J. (2012). Archaeology of the Kimberley, Northwest Australia. In C. Clement, J. Gresham, & H. McGlashan (Eds.), Kimberley history: People, exploration and development (pp. 24–39). Perth: Kimberley Society.

Morwood, M. J., Watchman, A. L., & Walsh, G. L. (2010). AMS radiocarbon ages for beeswax and charcoal pigments in North Kimberley rock art. Rock Art Research, 27(1), 3–8.

Mulvaney, D. J. (1969). The prehistory of Australia. New York: Frederick A. Praeger.

Newcomer, M. H. (1975). “Punch technique” and Upper Paleolithic blades. In E. H. Swanson (Ed.), Lithic technology: Making and using stone tools (pp. 97–101). The Hague: Mouton.

Newman, K., & Moore, M. W. (2013). Ballistically anomalous stone projectile points in Australia. Journal of Archaeological Science, 40, 2614–2620.

O’Brien, M. J., & Shennan, S. J. (2010). Issues in anthropological studies of innovation. In M. J. O’Brien & S. J. Shennan (Eds.), Innovations in cultural systems: Contributions from evolutionary anthropology (pp. 3–17). Cambridge: MIT Press.

O’Connell, J. F., & Allen, J. (2004). Dating the colonization of Sahul (Pleistocene Australia-New Guinea): a review of recent research. Journal of Archaeological Science, 31, 835–853.

O’Connor, S. (1999). 30,000 years of Aboriginal occupation: Kimberley, North West Australia. Terra Australis: Department of Archaeology and Natural History, The Australian National University. 14.

Ohnuma, K., & Bergman, C. (1982). Experimental studies in the determination of flaking mode. University of London Institute of Archaeology Bulletin, 19, 161–170.

Olausson, D. J. (2008). Does practice make perfect? Craft expertise as a factor in aggrandizer strategies. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 15, 28–50.

Paton, R. (1994). Speaking through stones: a study from Northern Australia. World Archaeology, 26(2), 172–184.

Patten, R. J. (1999). Old tools—new eyes, a primal primer of flintknapping. Denver: Stone Dagger Publications.

Pelcin, A. W. (1997). The formation of flakes: the role of platform thickness and exterior platform angle in the production of flake initiations and terminations. Journal of Archaeological Science, 24, 1107–1113.

Pelegrin, J. (1990). Prehistoric lithic technology—some aspects of research. Archaeological Review from Cambridge, 9(1), 116–125.

Pelegrin, J. (1993). A framework for analysing prehistoric stone tool manufacture and a tentative application to some early stone industries. In A. Berthelet & J. Chavaillon (Eds.), The use of tools by human and non-human primates (pp. 302–314). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Pelegrin, J. (2005). Remarks about archaeological techniques and methods of knapping: Elements of a cognitive approach to stone knapping. In V. Roux & B. Bril (Eds.), Stone knapping: The necessary conditions for a uniquely hominin behaviour (pp. 23–33). Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Pelegrin, J. (2006). Long blade technology in the old world: an experimental approach and some archaeological results. In J. Apel, K. Knutsson (Eds.), Skilled production and social reproduction (pp. 37–68). Societas Archaeologica Upsaliensis Stone Studies 2, Uppsala, Sweden.

Perez, E. (1977). Kalumburu: The Benedictine mission and the Aborigines 1908-1975. Kalumburu: Kulumburu Benedictine Mission.

Petri, H. (2011). The dying world in Northwest Australia. (Translation and reprint of Petri, H. [1954] Sterbende welt in Nordwest Australien). Victoria Park: Hesperian Press.

Pigeot, N. (1990). Technical and social actors: flintknapping specialists and apprentices at Magdalenian etiolles. Archaeological Review from Cambridge, 9(1), 126–141.

Porteus, S. D. (1931). The psychology of a primitive people: A study of the Australian Aborigine. London: Edward Arnold and Co.

Ratzat, C. (1994). Caught knapping: The fundamentals of flintknapping. Quapaw: DVD. Neolithics.

Redfearn, J. (2006). Making a Clovis point. Branson: DVD. Mound Builder Books.

Roth, W.E. (1904). Domestic implements, arts, and manufactures. North Queensland Ethnography Bulletin No. 7. The Home Secretary’s Department, Department of Public Lands, Brisbane.

Sackett, J. R. (1977). The meaning of style in archaeology: a general model. American Antiquity, 42(3), 369–380.

Sackett, J. R. (1982). Approaches to style in lithic archaeology. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 1, 59–112.

Sackett, J. R. (1986). Isochrestism and style: a clarification. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 5, 266–277.

Sackett, J. R. (1990). Style and ethnicity in archaeology: The case for isochrestism. In M. Conkey & C. Hastorf (Eds.), The uses of style in archaeology (pp. 32–43). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schlanger, N. (1996). Understanding Levallois: lithic technology and cognitive archaeology. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 6(2), 231–254.

Shea, J. J. (2006). The origins of lithic projectile technology: evidence from Africa, the Levant, and Europe. Journal of Archaeological Science, 33, 823–846.

Shott, M. J. (2002). Chaîne opératoire and reduction sequence. Lithic Technology, 28(2), 95–105.

Sinclair, A. (1995). The technique as symbol in late glacial Europe. World Archaeology, 27(1), 50–62.

Smith, C. (1992). Colonising with style: reviewing the nexus between rock art, territoriality and the colonisation and occupation of Sahul. Australian Archaeology, 34, 34–42.

Smith, M. A., & Ross, J. (2008). What happened at 1500-1000 cal. BP in Central Australia? Timing, impact and archaeological signatures. The Holocene, 18(3), 379–388.

Spencer, B. (1928). Wanderings in wild Australia. London: Macmillan.

Speth, J. D., Newlander, K., White, A. A., Lemke, A. K., & Anderson, L. E. (2013). Early Paleoindian big game hunting in North America: provisioning or politics. Quaternary International, 285, 111–139.

Thomson, D.F. (1935). Making of stone spear heads and stone (circumcision) knives, Ngillipidji, Upper Walker River, Blue Mud Bay, October, 1935. Unpublished manuscript.

Thomson, D. F. (1983). Donald Thomson in Arnhem Land. Melbourne: Currey O’Neil.

Tindale, N. B. (1965). Stone implement making among the Nakako, Ngadadjara, and Pitjandjara of the Great Western Desert. Records of the South Australian Museum, 15, 131–164.

Tindale, N. B. (1985). Australian Aboriginal techniques of pressure-flaking stone implements: Some personal observations. In M. G. Plew, J. C. Woods, & M. G. Pavesic (Eds.), Stone tool analysis: Essays in honor of Don E. Crabtree (pp. 1–33). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Tostevin, G. B. (2007). Social intimacy, artefact visibility and acculturation models of Neanderthal—modern human interaction. In P. Mellars, K. Boyle, O. Bar-Yosef, & C. Stringer (Eds.), Rethinking the human revolution: New behavioural and biological perspectives on the origin and dispersal of modern humans (pp. 341–357). Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monographs.

Tostevin, G. B. (2011). Levels of theory and social practice in the reduction sequence and chaîne opératoire methods of lithic analysis. PaleoAnthropology, 2011, 351–375.

Veitch, B. (1996). Evidence for Mid-Holocene change in the Mitchell Plateau, Northwest Kimberley, Western Australia. In P. Veth, P. Hiscock (Eds.), Archaeology of Northern Australia (pp. 66–89). Tempus 4, Anthropology Museum, University of Queensland.

Veitch, B. (1999). What happened in the Mid-Holocene? Archaeological evidence for change from the Mitchell Plateau, Northwest Kimberley, Western Australia. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Western Australia.

Veth, P., Stern, N., McDonald, J., Balme, J., & Davidson, I. (2011). The role of information exchange in the colonization of Sahul. In R. Whallon, W. A. Lovis, & R. K. Hitchcock (Eds.), Information and its role in hunter-gatherer bands (pp. 203–220). Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press.

Villa, P., Soressi, M., Henshilwood, C. S., & Mourre, V. (2009). The Still Bay points of Blombos Cave (South Africa). Journal of Archaeological Science, 36, 441–460.

Waldorf, D. C. (1993). The art of flint knapping (4th ed.). Branson: Mound Builder Books.

Waldorf, D. C. (2008). The secrets of notching: Thebes points and their variants. Branson: DVD. Mound Builder Books.

Wallis, L., & O’Connor, S. (1998). Residues on a sample of stone points from the west Kimberley. In R. Fullagar (Ed.), A closer look: Recent Australian studies of stone tools (pp. 150–178). Sydney University Archaeological Methods Series 6.

Walsh, G. L. (2000). Bradshaw art of the Kimberley. Toowong: Takarakka Nowan Kas Publications.

Walsh, G. L., & Morwood, M. J. (1999). Spear and spearthrower evolution in the Kimberley Region, N. W. Australia: evidence from rock art. Archaeology in Oceania, 34(2), 45–59.

Welch, D. M. (1996). Material culture in Kimberley rock art, Australia. Rock Art Research, 13(2), 104–123.

Wenban-Smith, F. F. (1989). The use of canonical variates for determination of biface manufacturing technology at Boxgrove Lower Palaeolithic Site and the behavioural implications of this technology. Journal of Archaeological Science, 16, 17–26.

White, M., & Ashton, N. (2003). Lower Palaeolithic core technology and the origins of the Levallois method in northwestern Europe. Current Anthropology, 44(4), 598–609.

Whittaker, J. C. (1994). Flintknapping: Making and understanding stone tools. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Whittaker, J. C. (2004). American flintknappers: Stone Age art in the age of computers. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Wiessner, P. (1983). Style and social information in Kalahari San projectile points. American Antiquity, 48(2), 253–276.

Wiessner, P. (1990). Is there a unity to style? In M. Conkey & C. Hastorf (Eds.), The uses of style in archaeology (pp. 105–112). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wilson, I. (2006). Lost world of the Kimberley: Extraordinary glimpses of Australia’s Ice Age ancestors. Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin.

Wobst, H.M. (1977). Stylistic behavior and information exchange. In C.E. Cleland (Ed.), For the director: Research essays in honor of James B. Griffin (pp. 317–342). Anthropology Papers, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, No. 61. Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Young, D. E., & Bonnichsen, R. (1984). Understanding stone tools: A cognitive approach (People of the Americas Process Series, Vol. 1). Orono: Center for the Study of Early Man, University of Maine.

Acknowledgments

The Northwest Kimberley project was a collaboration between the Wunambal Gaambera Aboriginal Corporation, Kandiwal Aboriginal Corporation, Kimberley Land Council, Uunguu Rangers, University of New England, Macquarie University, and the University of Wollongong. Fieldwork was supported directly by the Australian Research Council (ARC; LP0991845) and the Kimberley Foundation Australia, and in-kind support was provided by Heliwork and the Western Australia Department of Environment and Conservation. The analysis reported here was funded by the ARC (DP1096558). Field logistics and survey assistance were provided by June Ross, Mike Morwood, John Hayward, Kim Newman, Isabelle Balzer, Yinika Perston, and Robin Maher. Aboriginal participants included Albert Bundamurra Jr, Greg Goonack, John Goonack, Gavin Goonack, Myron Goonack, Cathy Goonack, Joseph Karadada, and Terrence Marnga. Moya Smith facilitated the inspection of ethnographic flintknapping tools and Kimberley Points held in the Western Australian Museum. Kim Newman and Yinika Perston helped prepare the figures. I thank Kim Akerman for his generosity and encouragement over many years; this study was greatly improved by comments by Kim, John Whittaker, and an anonymous reviewer. The author and field crew acknowledge the inspiration and support of the late Professor Mike Morwood.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moore, M.W. Bifacial Flintknapping in the Northwest Kimberley, Western Australia. J Archaeol Method Theory 22, 913–951 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-014-9212-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-014-9212-0