Abstract

The archaeological record of Northern Iroquoian peoples contributes to global questions about ethnogenesis, the emergence of settled village life, agricultural intensification, the development of complex organizational structures, and processes of cultural and colonial entanglement. In the last decade, the rapid accumulation of data and the application of contemporary theoretical perspectives have led to significant advances in Iroquoian archaeology, including new insights about how demographic, ecological, and cultural processes intersect at multiple temporal and spatial scales. Internal and external factors accelerated processes of cultural change, particularly during periods of conflict, coalescence, and encroachment. This review considers the historical development of Northern Iroquoian societies from the beginning of the Late Woodland through the colonial era. The dynamism of the settlement landscape is highlighted, together with the fluidity of sociopolitical identities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While the Lower Great Lakes region contains evidence for 13,000 years of human occupation, the archaeological record of Iroquoian peoples is notable for many reasons. During the first and second millennia AD, these societies underwent many of the major economic, social, and political transformations that underlay key questions of interest to archaeologists and anthropologists. These include the ethnogenesis of cultural groups, the adoption of domesticated plants and development of settled village life, intensification of agricultural production, endemic warfare, the coalescence of towns, and the development of increasingly complex social and political organizations. During the era of European contact and colonialism, Iroquoian people weathered epidemic diseases, entry into the global political economy, displacement from their ancestral lands, and the reorganization of their world. Today, contemporary Iroquoian nations and people are reclaiming this rich history by taking an active role in determining how their heritage will be managed and interpreted.

A number of major syntheses of Iroquoian archaeology have been published in the last 20 years (Bamann et al. 1992; Ellis and Ferris 1990; Ferris and Spence 1995; Snow 1994a, b; Warrick 2000), including demography (Warrick 2008), the study of a specific community (Birch and Williamson 2013a), and overviews of particular Iroquoian groups (e.g., Engelbrecht 2003; Garrad 2014; Tremblay 2006).

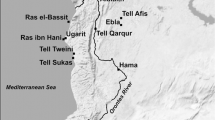

My focus is on recent developments in Iroquoian archaeology over the last decade, ca. 2003–2013. I present a brief discussion of the conceptual and methodological frameworks that have guided Iroquoian archaeology on both sides of the Canada-U.S. border before reviewing current data and thinking on the ethnogenesis and historical development of Northern Iroquoian societies from the end of the first millennium through the colonial period. I focus on the Iroquoian “heartland” surrounding Lakes Ontario and Erie and adjacent regions (Fig. 1), with the goal of integrating data from south-central Ontario and upstate New York. I give other areas inhabited by Iroquoian speakers, including southwestern Ontario, Pennsylvania, and Quebec, less thorough treatment. I consider the relationships between archaeology and contemporary Iroquoian peoples and future directions for research in concluding sections of the paper.

Northern Iroquoian societies

The term “Iroquoian” refers to both a linguistic and a cultural pattern. These languages were distinct from distantly related Southern Iroquoian dialects spoken by the Cherokees of the southern Appalachians. At the time of sustained European contact in the early 1600s, Northern Iroquoian speakers inhabited southern Ontario, southwest Quebec, the Finger Lakes region and Mohawk River valley of New York, and the Susquehanna Valley (Fig. 2). These groups shared a number of cultural traits, including settlements surrounded by palisades that enclosed bark-covered longhouses, subsistence based on maize horticulture supported by hunting, fishing, and gathering, a social structure organized around matrilineal descent and clan membership, and political organization based on village councils, nations of affiliated villages, and regional confederacies (e.g., Engelbrecht 2003; Snow 1994b; Trigger 1976; Williamson 2012). Archaeological remains that include these traits are thought to represent ancestral Iroquoian-speaking peoples (Warrick 2000, p. 417), though the relationship between material culture, language, and ethnicity and what constitutes early forms of longhouses, horticulture, and sociopolitical organization is far from clear (e.g., Hart 2011; Hart and Brumbach 2003; Pihl et al. 2008).

At the time of sustained European contact in the early 17th century, Northern Iroquoian peoples were organized into political confederacies of allied nations that inhabited discrete territories. The Wendat occupied the area between Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay. Prior to the 17th century, their ancestors inhabited the entire north shore of Lake Ontario and the Trent Valley. The Wendat confederacy comprised four or five nations. The Attignawantan (“of bear country”) dominated the affairs of the confederacy and were divided into northern and southern groups, each speaking a distinct dialect (Steckley 2007, pp. 36–37). The Attignawantan and Atingeennonniahak (“makers of cord”) were the earliest Iroquoian inhabitants of Wendake, the historic Wendat homeland. The Ataronchronon (“people of the swamp, mud, or clay”) lived in the lower Wye valley. They were not recognized in the political organization of the confederacy and may have been a division of the Attignawantan (Trigger 1976, p. 30). During the late 16th and early 17th centuries, two more nations joined the confederacy, the Arendarhonon (“people at the rock”) and Tahontaenrat (“two white ears” [Steckley 2007, p. 34] or “people of the one single white lodge” [Jones 1909, p. 181]). Although there is no consensus on the etymological roots of the word Wendat (Steckley 2008, p. 95), it is the name the current Huron-Wendat Nation prefers.

The Tionontaté (“people where there is a hill” [Steckley 2007, p. 28]) lived southwest of the Wendat near the Blue Mountains. Their confederacy included two separate groups: the Wolf and Deer (Garrad 2014; Thwaites 1896–1901, v. 33, p. 143; v. 20, p. 43). In the early 17th century, they were allied with the Wendat against their common enemies among the Haudenosaunee. The combined population of the Wendat-Tionontaté prior to the spread of European epidemics in the 1630s was approximately 30,000 (Warrick 2003, 2008, p. 204).

The Neutral (their endonym is unknown) lived on the peninsula separating Lakes Erie and Ontario. Prior to the 16th century, ancestral Neutral settlement formed a broad band of villages spanning the north shore of Lake Erie and west end of Lake Ontario. In the 1640s, they occupied four communities or site clusters near the Grand River valley and the northern Niagara Frontier of New York (White 1978a, p. 408). They interacted frequently with populations in the western basin of Lake Erie, Fort Ancient peoples in the Ohio Valley, and possibly groups as far south as Alabama (Fox 2009, p. 68). At the time of European contact, the Neutral had coalesced east of the Grand River on the Niagara Peninsula and around the far western end of Lake Ontario (Lennox and Fitzgerald 1990). The Wenro were a small Iroquoian group possibly related to and living east of the Neutral in the early 16th century (White 1978a).

Less is known about the contact-period Erie (“nation of the cat”) who lived south of Lake Erie than their Iroquoian neighbors, due in part to the paucity of contact with early Europeans (White 1978b). The material culture and mortuary assemblages of the Erie and Neutral are similar, and both groups may have originated among populations in southwestern Ontario (Fox 2009; Lennox and Fitzgerald 1990; MacNeish 1952). In the contact period, following dispersals by Haudenosaunee raiding parties, the Erie and their allies (then known as the Westo) were key players in the Native slave trade (e.g., Bowne 2005, 2009; Ethridge 2006, 2009; Fox 2009; Meyers 2009).

The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) lived in separate tribal groupings of across central New York. They included (from west to east) the Seneca (“great hill people”), Cayuga (“people at the landing” or “where the boats are taken out” [Fenton 1998, p. 51]), Onondaga (“people on the hill”), Oneida (“people of the standing stone”), and Mohawk (“people of the flint” [Fenton and Tooker 1978, p. 478]; see Engelbrecht (2003) for summaries of the specific histories of each nation). At the time of contact, the Five Nations were allied into a confederacy called the Haudenosaunee (Engelbrecht 2003, p. 129; Fenton 1978; Morgan 1962[1851]). The Haudenosaunee population was likely greater than that of the combined Wendat-Tionontaté in the early contact period (Trigger 1985, p. 236).

The Susquehannock are not identified as a culturally distinct people until ca. AD 1550 (Gollup 2011; Kent 1984). In prehistoric times, they inhabited scattered hamlets along the north branch of the Susquehanna River; they relocated into larger villages located farther downstream in the contact era (Kent 1984; Wall 2004). They shared many aspects of their subsistence, settlement, and material culture patterns with Iroquoians, and spoke an Iroquoian language. The Susquehannock remain poorly understood and in terms of their origins and relationships with Europeans and adjacent Native people.

Prior to European contact, the St. Lawrence Valley was populated by Iroquoian-speaking communities, collectively referred to as St. Lawrence Iroquoians (Jamieson 1990; Tremblay 2006). They inhabited villages near present-day Montreal and Quebec City, but by the time Champlain arrived in 1603, the villages along the St. Lawrence River had been abandoned. Although the “disappearance” of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians was at one time a subject of significant archaeological debate (Jamieson 1990; Pendergast 1993), the reconfiguration and relocation of this population can be explained in terms of the dynamic settlement landscape that characterized the Iroquoian world.

Similarities in the basic traits of Northern Iroquoian societies—language, settlement patterns, maize, sociopolitical organization, and belief systems—have at times been generalized into a broadly “Northern Iroquoian” cultural pattern. There is an essential tension between current theoretical perspectives on the boundedness of archaeological cultures and the terminology we use to discuss them (e.g., Biesaw 2010; Hart 1999; Perrelli 2009; Williamson and Watts 1999). Contemporary perspectives acknowledge that each community, nation, and confederacy was the product of unique and historically contingent processes of development in distinct geographic and social landscapes. These differences are reflected in their languages, material culture, clan organization, kinship terms, mortuary practices, and differential interactions with nearby and more distant groups. At the same time, insights from both sides of the border now attest to the fluidity of social boundaries and identities (Biesaw 2010; Birch and Williamson 2013a, pp. 128–145; Hart and Engelbrecht 2012; Knapp 2009). Iroquoian communities were connected to, and at times populated in part by, people that would be considered culturally and linguistically differentiated from Iroquoians, including the ancestors of the Ojibway, Nipissing, Odawa, Abenaki, and other northeastern peoples (e.g., Bradley 1987; Fox 2008; Fox and Garrad 2004; Ramsden 2006).

Ethnohistory and archaeology

The archaeology of Northern Iroquoians has been profoundly influenced by ethnographic and historical descriptions by Europeans who visited and colonized eastern North America in the 16th through 18th centuries. The three primary historical sources on the 17th-century Wendat are Champlain (Biggar 1929), Sagard (Wrong 1939), and the Jesuit Relations (Thwaites 1896–1901). All three sources have been synthesized by Tooker (1964), Heidenreich (1971), and Trigger (1969, 1976, 1985). Sagard also produced a comprehensive dictionary of the Wendat language, translated by Steckley (2009). Steckley’s ethnolinguistic analyses of Wendat language provide valuable insights into the worlds of the Wendat and Wyandot (2004, 2007, 2008). For the Haudenosaunee, the writings of van den Bogaert (Gehring and Starna 1988) and Lafitau (Fenton and Moore 1974), together with the Relations, are important early post-contact sources. Observations of later anthropologists, notably Morgan (1962[1851]), Hale (e.g., 1963[1883]), Goldenweiser (e.g., 1913, 1914), Parker (e.g., 1910, 1916), Beauchamp (e.g., 1922), Fenton (e.g., 1978, 1998), and Tooker (1964, 1970) have been profoundly influential.

The rich historical record and ethnographic constructs of precontact Iroquoian societies, however, may have hampered the ability of archaeologists to develop new interpretations of Iroquoian social and political organization (Jamieson 2011; Ramsden 1996). Yet with judicious employment of this detailed record and new conceptual frameworks for studying the past (Trigger 2006, p. 497), more productive syntheses are possible. Examples of this convergence include Robb’s (2008) analysis of Huron and Jesuit perspectives on prisoner sacrifice as symbolically constructed behavior and Watts’(2009) discussion of the phenomenology of Iroquoian longhouses, both of which fuse ethnohistoric descriptions with theories of embodied practices and semantic systems.

Research trajectories in Iroquoian archaeology

Iroquoian archaeology came into its own in the early 20th century when issues of taxonomy and classification dominated North American archaeology (Smith 1990; Trigger 2001, p. 5). In both Ontario and New York, culture-historical taxonomies were used to order sites into cultural sequences (Emerson 1954; MacNeish 1952; Parker 1922; Ritchie 1965; Wright 1966). While many Iroquoian archaeologists have been dissatisfied with these classification schemes (e.g., Ferris 1999; Ferris and Spence 1995; Hart and Brumbach 2003; Hart 1999, 2011; Lennox and Fitzgerald 1990; Williamson and Watts 1999; Williamson 1990), some elements have been retained as convenient shorthand.

Some researchers have made efforts to abandon culture-historical terms entirely (e.g., Birch 2012; Hart 1999; Hart and Brumbach 2003; Williamson 1999), or replace them with other schemes (Ferris and Spence 1995) that reflect their own research interests (Birch et al. in press; Hart and Engelbrecht 2012). Classification, however, will always be central to archaeological reasoning and “will occur implicitly if it is not done explicitly” (Trigger 1999, p. 304). The challenge for those who seek to abandon culture-historical constructs is the acknowledgment that while they hamper our ability to understand the past as a continuum, these taxa also reference real changes in some elements of past societies. Although we may not recognize “Owasco,” “Uren,” or “Chance” as distinct phases, they relate to periods of cultural development punctuated by episodes or events that transformed the social, political, and economic fabric in meaningful ways (Beck et al. 2007).

Iroquoian archaeology in the 21st century is characterized by a greater degree of “theoretical self-consciousness” (Rieth and Hart 2011, p. 1) than past approaches. Rather than explicitly engage in large-scale theoretical debates, researchers have more commonly aligned themselves with middle-range approaches (Trigger 2001). In Canada, Iroquoian studies were influenced profoundly by Bruce Trigger (Pearce et al. 2006). Trigger never explicitly aligned himself with any of the more easily identifiable theoretical positions in archaeology (1978, p. vii; Hodder 2006); instead he took a more systematic approach, recognizing that culture is meaningfully and historically constituted, that there is a dialectical relationship between data and theory, and that different pasts are constructed by social and political dispositions in the present (Trigger 1984, 2006). His legacy is a field of study that focuses on narratives of demographic, ecological, and cultural process that intersect at multiple temporal and spatial scales (e.g., Birch 2012; Birch and Williamson 2013a; Creese 2010; Fitzgerald 1990; MacDonald 2002; Pearce 1984; Smith 1997; Timmins 1997; Warrick 2008, 2012; Williamson 1985).

Although the variable backgrounds of practitioners led to somewhat less connected research trajectories in New York, the essential focus on settlement archaeology and the smooth blending of processual and postprocessual approaches has been the same. Snow and his students (e.g., Bamann 1993; Hart and Brumbach 2003, 2009; Jones 2006, 2010a, b; Schulenberg 2002) have provided a similar degree of stability and coherence to Iroquoian studies. The use of geographic information systems (GIS) was first introduced to Iroquoian studies in New York, where researchers have explored demographic patterns and settlement choice on the basis of ecological, social, and cultural factors (Allen 1996; Hasenstab 1996a, b; Hunt 1992; Jones 2006, 2010a, b, c; Jones and Wood 2012).

On both sides of the border, the most enduring effect of the centrality of settlement pattern studies has been the emphasis on communities and site sequences (Trigger 2001, p. 7). The co-residential community—as opposed to the nation or the confederacy—was the focus of Iroquoian group identity (Trigger 1978, pp. 306–307; Williamson and Robertson 1994; see also Boulware 2011 regarding the Cherokee). After ca. AD 1250–1300, village sites were relocated regularly. When villages were abandoned, the community usually relocated a few kilometers away, though longer migrations were possible, as was village fission and fusion. Because village sites were rarely reoccupied, each represents a record of the activities of a single generation. Numerous site relocation sequences have been constructed that represent hundreds of years of occupation by contiguous groups (e.g., Bamann 1993; Birch and Williamson 2013a, pp. 25–51; Finlayson 1998; Niemczycki 1984; Pearce 1984; Snow 1995a; Tuck 1971; Warrick and Molnar 1986; Williamson 1985).

In Ontario, the co-evolution of cultural resource management (CRM) policy and community-based settlement archaeology has significantly advanced Iroquoian studies. Ontario has a progressive legislative framework that requires the complete mitigation of archaeological resources in advance of land-disturbance activities conducted on both public and private lands (Ferris 2002; Williamson 2010). This has resulted in dozens of complete village excavations in the last 30 years (e.g., A. M. Archaeological Associates 1997; Archaeological Services Inc. (ASI) 2003, 2006a, b, 2008, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2014; Archaeologix 2006; D. R. Poulton and Associates 1994, 1996, 2003; Lennox 1995; Lennox et al. 1986; Timmins 2009). In Ontario, the study of site relocation sequences has moved beyond stringing sites together using ceramic attributes and other categories of material culture to the examination of occupational histories of sequential villages, including intrasite material culture patterns, modifications to the built environment, and changes in cultural practices within and between contiguous community sequences (Birch 2012; Birch and Williamson 2013a). In the United States, CRM is undertaken on a much narrower set of land-use projects, resulting in less site identification and data recovery (but see Biesaw 2010; Kuhn 1994; Knapp 2009; Perrelli 2009). Nevertheless, there is a need in both countries for meaningful synthesis of CRM-derived data within anthropologically driven research designs.

Iroquoian ethnogenesis

The establishment of an “island” of Iroquoian populations in a “sea” of Algonquian people has been a subject of interest to anthropologists for well over a century (Boas 1910, pp. 531–532; Morgan 1962[1851]; Williamson 2012, p. 275). The earliest debates relied solely on ethnographic and archaeological evidence. Today insights from linguistics and molecular biology have been brought to bear on this question, together with new perspectives on how interaction, migration, and acculturation shape the material record.

Early explanations of Iroquoian origins focused on the migration of farmers from the south (Boas 1910, p. 532; Parker 1916). Later researchers argued for in situ development from extant hunter-gatherer populations (MacNeish 1952; Ritchie 1965; Wright 1966). Two decades ago, Snow gave new life to the migrationist hypothesis (1995b, 1996a), though it did not receive widespread acceptance (e.g., Ferris 1999; Hart 2001; Trigger 2001; see Ferris and Spence 1995; Warrick 2000; Martin 2008 for summaries of this debate). While the debate over Iroquoian origins has not been resolved, contemporary researchers reject overly generalized theories, acknowledging the complexity of processes of ethnogenesis and bringing together diverse theoretical perspectives and large quantities of data.

Current ideas about Iroquoian “origins” focus on ethnogenesis—intrinsically historical and complex processes by which a group of people comes into being as a socioculturally definable group (Engelbrecht 2003; Hu 2013; Moore 1994; Weigelt 2012). An ethnogenetic approach can accommodate biological and cultural data in the context of multiple intersecting and diverging historical processes that include the movement of biological populations, the role of language, acculturation, the diffusion of ideas, and the endurance and transformation of cultural traditions, which allows for a more realistic and complex view of Iroquoian cultural development (Engelbrecht 2003, pp. 112–114; Martin 2008).

Cultural traits

Demonstrably “Iroquoian” cultural traits were not fully developed until the turn of the 14th century (e.g., Engelbrecht 2003; Hart 2011; Hart and Brumbach 2003, 2009; Hart and Means 2002; Pihl et al. 2008; Spence 1999). In New York, the original definition of the early Iroquoian Owasco phase (Ritchie 1965) included the triad of maize-bean-squash agriculture, distinctive ceramic technologies, and the widespread adoption of longhouse villages. Reassessments of Owasco as a cultural taxon and the recognition that each of these cultural traits had differential histories of development led to claims of its “death” (Hart and Brumbach 2003; see also Hart 1999, 2011; Hart and Brumbach 2005, 2009). In Ontario, calls for the abandonment of the early Ontario Iroquoian Glen Meyer and Pickering phases (Wright 1966) were expressed early on, with the recognition that local site sequences were more or less continuous through what had been classified as distinct phases (Pearce 1984; Williamson 1985, 1990, p. 295). Furthermore, traits that were thought to correspond to an Iroquoian taxonomic unit are not unique to Iroquoian-speaking people and differ significantly within the Iroquoian culture area (e.g., Fox 1990; Hart and Brumbach 2009; Hart and Means 2002; Rankin 2000).

Genetic data

Genetic studies provide additional insights into the question of Iroquoian origins. Similarities in the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from individuals living in the central Illinois River valley, the western basin, and southwestern Ontario between 1500 BC and AD 800 indicate sufficient gene flow and sustained genetic continuity between Late Archaic and Woodland populations to result in regional continuity of haplotype frequencies as early as 3000 years ago (Shook and Smith 2008). Yet genetic studies can be problematic. In a study of haplotype frequencies in eastern North America, samples taken from a Mohawk community in upstate New York were said to exhibit continuity with both Algonquin and Siouan populations (Malhi et al. 2001, p. 38) and with Cherokee populations (Malhi et al. 2001, p. 42). As such, components of these data could be said to support either long-term continuity or more recent migration. Bolnick et al. (2006) argue that males and females in eastern North America show opposite patterns of genetic differentiation. Whereas low differentiation in mtDNA characterizes northeastern populations, Y chromosome data indicate high differentiation and a female migration rate and/or an effective population size more than twice that of males (Bolnick et al. 2006, p. 2168).

Pfeiffer et al. (2014) studied mtDNA from teeth recovered from ancestral Wendat and Neutral communities and found a great deal of diversity within individual mortuary populations. Derived mutations in two haplotype sequences from individuals at the 16th-century Mantle site were common to groups belonging to the Archaic Glacial Kame and Early Woodland Red Ocher traditions (Pfeiffer et al. 2014, pp. 339–340). Although these results are based on a small sample and are not statistically significant, the authors suggest a population-based approach to future genetic studies, recognizing that significant population movement and diversification took place in the Lower Great Lakes during the Middle and Late Woodland periods (Pfeiffer et al. 2014, p. 344).

Linguistic evidence

At the time of European contact, Northern Iroquoian speakers were surrounded on all sides by Algonquian speakers. The origins, linguistic divergence, and geographic movement of Iroquoian languages are a topic of considerable debate (e.g., Fiedel 1999; Foster 1996; Lounsbury 1978; Mithun 1984; Williamson 2012; Whyte 2007), and there is no consensus regarding the location of the Iroquoian linguistic “homeland.”

Based on glottochronology, the split between Southern and Northern Iroquoian languages is estimated to have occurred in the Late Archaic, ca. 1,500 to 2,000 BC (Foster 1996, p. 105; Lounsbury 1978). Another recent interpretation suggests an origin in the Midwest, possibly in or near the Ohio River valley, or in the southern or middle Appalachian mountain chain ca. 2,000 to 3,000 BC (Whyte 2007). Most scholars agree that the separation of dialects of Northern Iroquoian languages from the proto-Iroquoian language occurred more recently. A comparison of Tuscarora, Nottoway, and Meherrin, spoken on the mid-Atlantic coastal plain, with the other Northern Iroquoian languages indicates a separation time ca. 400 BC–AD 100. The split between the dialects spoken by the Five Nations likely occurred between AD 500 and 800 (Foster 1996, p. 106; Mithun 1979; Whyte 2007). According to Steckley (2007), the Northern Iroquoian languages of the lower Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Valley form three groups: Huron-Wendat (encompassing Wendat, Wyandot, St. Lawrence Iroquoian, Onondaga, and Susquehannock), Seneca-Cayuga, and Mohawk-Oneida. We might infer different origins for each group and closer historical connections between those with linguistic ties (see also Ramsden 2006).

Entry of maize

Over the last decade, there have been substantial advances in the investigation of how maize (Zea mays ssp. mays) came to play a dominant role in Iroquoian subsistence economies. Reliance on macrofossils has been augmented by stable isotope analysis of human bone and teeth (Harrison and Katzenberg 2003; Katzenberg 2009; Katzenberg et al. 1995; Schwarcz et al. 1985; van der Merwe et al. 2003; Watts et al. 2011) and cooking residues (Hart et al. 2007b, 2009, 2012), and phytolith analysis (Hart et al. 2003, 2007a; Hart and Matson 2009; Raviele 2011; Thompson et al. 2004). It is increasingly clear that the history of the transmission and adoption of cultigens were a gradual and differentiated process (Hart and Lovis 2013).

The initial introduction of maize into the Northeast supplemented rather than dramatically altered traditional subsistence patterns based on hunting, fishing, and gathering. Cooking residues, phytoliths, and macrobotanical remains indicate that a broad range of seed-bearing plants, including wild rice, sedge, and little barley, were exploited by ancestral Iroquoian populations in New York (Hart 2008; Hart et al. 2003, 2007b), although none exhibit the morphological changes associated with domestication (Asch Sidell 2008). There is phytolith evidence for maize in New York as early as 300 BC at the Middle Woodland Vinette site in the Finger Lakes region (Hart et al. 2007a; Thompson et al. 2004). Isotopic analysis of dentin and enamel of human teeth, together with significant dental caries in burials from the Kipp Island site in north-central New York, indicates that maize was as a significant component of the diet as early as the 7th century AD (Hart et al. 2011).

In the Grand River valley of southern Ontario, macrobotanical maize remains found in context with ceramics and stone tools used for processing have been AMS dated to ca. AD 400–600 (Crawford et al. 1997, 2009). A calibrated radiocarbon date of AD 650 taken on charcoal from a feature in which a maize kernel was found may indicate the concomitant introduction of maize in the Rice Lake region of southeastern Ontario (Jackson 1988). Although pathways for the transmission of various landraces of maize are not completely understood, Hart and Lovis (2013) argue for multiple demes of local maize that were spread and perpetuated through inter- and intraregional networks of seed dispersal and knowledge sharing in the context of local soil conditions, climates, and ecological landscapes.

Based on isotopic analyses of bone collagen and carbonate from multiple sites in southern Ontario, maize did not become a substantial part of the diet until 1000 years ago (Harrison and Katzenberg 2003, p. 241). The use of maize as a nutritional staple was not restricted to proto-Iroquoian populations. Stable isotope data from the semisedentary Western Basin mortuary community at the Krieger site in southwestern Ontario suggest that these populations, who never abandoned a mobile settlement pattern, were equally dependent on the crop by ca. AD 1000–1200 (Watts et al. 2011).

A long-standing problem in maize research is the interpretation that its introduction was a “transformative” experience (Hart 2008, p. 90; see also Lusteck 2009). For at least part of its long history of adoption, maize was cultivated by mobile populations and transmitted to others through those same pathways (Hart 1999; Hart and Lovis 2013; see Chilton 2008 for New England). Based on the available data, the incorporation of maize into indigenous economies and landscapes was a gradual and multilinear process that unfolded in different ways at different times in different places (e.g., Chapdelaine 1993; Hart and Brumbach 2003; Hart and Lovis 2013; Hart and Means 2002; Pihl et al. 2008; Williamson 1990).

Settling the village and becoming “Iroquoian”

In Ontario, village sites dating earlier than ca. AD 1000 are characterized as transitional between the Middle and Late Woodland (Crawford et al. 1997; Ferris and Spence 1995; Williamson 1990). They occur primarily in riverine floodplain environments and consist of clusters of hearths and pits associated with poorly defined ovoid or circular house structures. Some may have functioned as “base camps” for groups with a semisedentary subsistence pattern (Kapches 1987; Pihl et al. 2008; Stothers 1977). Large, deep storage pits, some of which contain maize, suggest a commitment to site locations.

The most complete record of village life ca. AD 1000–1300 is documented on the sand plains of southwestern Ontario (Fox 1986; Timmins 1997; Williamson 1985). On the north shore of Lake Ontario, most early Iroquoian sites were located on the easily cultivated, sandy soils of the glacial Lake Iroquois plain (Warrick 2000, p. 419). In New York, early Iroquoian site clusters are documented on the Niagara frontier, in the northern Finger Lakes region, Mohawk River valley, and in the Susquehanna River valley (e.g., Hart 2000; Rayner-Herter 2001; Ritchie and Funk 1973; Snow 1995a).

Typical early Iroquoian occupations consist of two or more contemporary structures averaging 10–20 m in length, often surrounded by fences or “palisades” consisting of one or two rows of posts (Dodd 1984; Pearce 2008–2009; Ritchie and Funk 1973; Timmins 1997; Warrick 1996) (Fig. 3). These insubstantial palisades most likely served symbolic or functional purposes rather than defensive ones (Engelbrecht 2009; Ramsden 1990a). In both Ontario and New York, small ovoid structures were expanded or reconstructed into longhouse-like forms (Fox 1986; Ritchie and Funk 1973, p. 197; Timmins 1997). Although the gradual shift to generalized matrilocal residence patterns and matrilineal reckoning of descent appears roughly contemporary with the development of horticulture, investment in village life, and expansion of Iroquoian settlement into a landscape inhabited by hunter-forager populations (e.g., Divale 1984; Hart 2001; Hart and Brumbach 2003, 2009), the precise mechanisms require further explanation.

Iroquoian community patterns, ca. AD 1000–1450. Note disorganized appearance of very early villages. After AD 1300 village plans are variable, but all contain one or more discrete clusters of longhouses. Complete or relatively complete village plans selected to demonstrate variability and change over time. A Miller (Kenyon 1968); B Elliott (Fox 1986); C Kelso (Ritchie and Funk 1973); D Myers Road (Ramsden et al. 1998); E Uren (Wright 1986); F Howlett Hill (Tuck 1971); G Robb (ASI 2010); H Alexandra (ASI 2008); I Hope (ASI 2011); K Baker (ASI 2006b); J Coleman (MacDonald 1986); L Over (D. R. Poulton and Associates 1996)

Watts’ (2008, pp. 17, 20) analysis of interactions between Iroquoians and Western Basin peoples, ca. 1000–1300, situates these trends within a theoretical framework of actor-network theory and Piercian semiotics. He suggests that more uniform dynamics of social life emerged over the course of one or two centuries (Watts 2008, p. 88). He also notes that the comparative heterogeneity of less “settled” sites, which are both earlier and largely contemporary with early Iroquoian settlements, indicates that the earliest proto-Iroquoian communities lived alongside and with Western Basin peoples. Residence and ethnicity were perhaps more fluid and compatible than taxonomic and culture-historical schemes have permitted (see also Fox and Garrad 2004; Ramsden 2006).

Village sites of the 13th and 14th centuries have a “disorganized appearance,” consisting of unaligned and superimposed structures from successive phases of semisedentary occupation and reoccupation, likely by the same group over a number of generations (Fox 1986; Timmins 1997; Williamson 1990) (Fig. 3). Thus, some village sites of the early Iroquoian period might be characterized as “persistent places” that are occupied or reoccupied over extended periods (Schlanger 1992). Over time, we see increasing organization of domestic space. Creese (2012) argues that, in Ontario, bilateral symmetry had emerged in living arrangements by the 12th century, where two families shared a hearth, occupying living quarters on opposite sides of a longhouse. The increasing organization of space at the household and village level coincides with increasing investment in village sites as loci for year-round habitation (Dodd et al. 1990). Significant processes of “place making” appear to have been in operation, which established and reinforced the stability of co-residential groups (Creese 2013, p. 207).

Early Iroquoian sites generally occur in discrete clusters of semipermanent villages together with smaller components thought to represent camps or resource extraction loci (Williamson 1990). These settlement clusters are interpreted as contemporary communities that shared a hunting territory and a common resource base (Timmins 1997, p. 228). Most early Iroquoian sites are in areas with relatively easy access to a wide array of environmental zones, including mast-producing forests, swamps, and lacustrine resources (Ritchie and Funk 1973; Timmins 1997; Williamson 1990). Adaptation to variable ecological niches and increasing investment in villages may have resulted in an increasing concern for the maintenance of physical and social boundaries between settlement clusters (Birch and Williamson 2013a, p. 15; Creese 2013). That ceramic design sequences differ between these local clusters and are more homogeneous within them is consistent with increasing boundary maintenance and the formation of local identities (Williamson 1985, pp. 289–290). Patterns of group interaction, including the search for mates, were focused on the local region (Williamson and Robertson 1994). Nevertheless, long-distance interaction was occurring. Fox (2008, pp. 3, 13) argues that small quantities of marine shell and V-shaped antler combs on 12th and 13th century sites in southern Ontario represents the waning of earlier Middle Woodland networks and the exchange of exotic raw materials and finished products. Materials that indicate connections to southeastern groups are conspicuously absent on later, 14th century sites. The reorientation of exchange and interaction to Algonquian trading partners in the Upper Great Lakes is suggested by an increase in native copper, usually in the form of rolled sheet beads (Fox 2008, p. 7).

The creation and maintenance of social boundaries played a significant role in the ongoing development of cultural and territorially bound identities. On the Niagara frontier of western New York, a cluster of three sites dating to the 13th century (Rayner-Herter 2001) exhibit ceramic traits and a well-developed horticultural settlement-subsistence system that appears to represent an “intrusive” Ontario Iroquoian population (Niemczycki 1988; Rayner-Herter 2001, p. 237). Ditches and earthworks at the Oakfield and Woeller sites were likely erected as defensive measures. Tension between the newcomers and extant proto-Seneca populations may have played key role in the development of the Seneca as a discrete sociopolitical entity in the centuries that followed (Niemczycki 1988).

Developments in the 14th and early 15th centuries

Profound changes in social and economic conditions accompanied the transition to settled village life. The turn of the 14th century, ca. 1275–1325, was a period of significant innovation or “culture making” (Pauketat 2005, pp. 205–208) that included the fusion of well-established Eastern Woodland traditions with rapid and innovative forms of agency. Blitz (2010, p. 16), writing about the Mississippian Southeast, noted that such innovation “punctuates and alters incremental practice,” facilitating rapid transformations of landscapes and social memories. Later, communities consolidated new forms of sociopolitical organization, created social and economic networks that linked communities within the wider region, and developed cultural practices that facilitated both regional interaction and the integration of local groups.

Until recently, the 14th century was considered a period of widespread cultural homogeneity in Ontario Iroquoian life (Dodd et al. 1990; Wright 1966). New data from numerous excavations of complete villages make it clear that life in Iroquoian communities during the 14th and early 15th centuries was, in fact, quite variable. In New York, this period marks the beginnings of territorial consolidation and the expression of subcultural identity among the emergent nations of the Haudenosaunee (Niemczycki 1984, p. 33). In Ontario, where settlement was more evenly distributed, social differentiation occurred slightly later, during the early-to-mid 15th century. At the same time, there is no evidence that Iroquoian village communities in either Ontario or New York formed discrete political entities until the late 15th to 16th centuries.

Based on isotopic data from human skeletal material, maize reliance among Ontario Iroquoian populations increased significantly, to approximately 50–60% of the diet in the late 13th to early 14th centuries (Harrison and Katzenberg 2003; Katzenberg et al. 1995; Schwarcz et al. 1985). The amount of maize in the diet of any community at any point in time, however, could have varied due to climatic, environmental, or social factors. Analyses of the mortuary population at the late 13th-century ancestral Wendat Moatfield site (Williamson and Pfeiffer 2003) suggested that maize was 70% of the diet for a single generation, among individuals between 20 and 30 years old (van der Merwe et al. 2003). This was seemingly a short-term pattern related to the initial coalescence of the village (Pfeiffer and Williamson 2003, p. 342). For later generations, the amount of maize in the diet decreased to a more nutritionally sustainable level of 55–60%, a figure in keeping with estimates for other late precontact Wendat populations.

The increasing reliance on horticulture by populations in the Lower Great Lakes coincides with the onset of the Little Ice Age, ca. 1300–1800. While the medieval warm period, ca. 900–1250, marks the widespread adoption of maize in the northeast, the intensification of cultigen production after ca. 1250 coincides with climatic cooling, sedentism, and aggregation into larger villages (Birch and Williamson 2013a, pp. 99–101; Bradley 2007, p. 18; Milner 1999). Further research is required to clarify the link between climatic variability and increased focus on a cultigen that had, for the previous eight centuries, played a peripheral role in proto-Iroquoian subsistence.

Population growth

Warrick (2008) has documented a late 14th century population increase consistent with the Neolithic Demographic Transition, when increased fertility and decreased juvenile mortality led to population growth following the transition to farming. This global trend in early village development was first recognized by Bocquet-Appel (2002) and has been confirmed by North American mortuary data and Iroquoian demographic data (Bandy 2008; Bocquet-Appel and Naji 2006).

According to Warrick (2008), the Wendat-Tionontaté population of south-central Ontario grew from 3,000 to 9,500 between ca. AD 1000 and 1300. Between 1330 and 1420, south-central Ontario experienced a “population explosion” to approximately 24,000, equivalent to the doubling of population every third generation (Warrick 2008, pp. 141–142, 150 [see fig. 5.12]). Late 14th century growth resulted in a marked increase in the number of village sites, the formation of larger villages, and the continued migration of groups into adjacent areas, including the Trent Valley and historic Huronia. After 1450, the population stabilized at 30,000 and remained there into the contact era. Warrick’s modeling was conducted with data available in 1990. Although his figures are still the most cited source of Wendat-Tionontaté demography, there are now more known village sites that any future population estimates will have to consider, together with the differential “packing” of settlements (Figs. 2 and 3).

There are fewer demographic data available for New York prior to AD 1500. An increase in the number of early Seneca and Cayuga sites, however, may reflect population growth in the western part of the state. The number and size of settlements remained relatively stable among 14th century proto-Onondaga and Mohawk populations (Bamann 1993; Bradley 1987; Tuck 1971), suggesting that population growth varied by subregion.

Demographic growth was a major factor influencing the northward and westward movement of ancestral Wendat populations. After 1300, multiple farming communities migrated north into the Simcoe Uplands (MacDonald 2002; Sutton 1999) and east into Trent Valley (Ramsden 1990b; Sutton 1990). The movement of Iroquoian populations brought them into more regular contact with mobile Algonquian speakers whose range included these newly colonized areas. Negotiations, possible tensions, and increased opportunities to trade may have characterized these interactions and formed the basis for the relationships between the Wendat and their neighbors to the north. At contact, these interactions included trade in maize and furs, the blending of cultural traditions, and the formation of multi-ethnic settlements (Fox and Garrad 2004; Garrad 2014; Labelle 2013; Rankin 2000).

Community organization

In both Ontario and New York, there is continuity between the location of earlier semisedentary populations and the more permanent nucleated village sites that characterized the late 13th and 14th centuries. In Ontario, village size doubled to 1.0–1.5 ha (Dodd et al. 1990). Settlements on the north shore of Lake Ontario in the early 14th century were somewhat larger than immediately earlier or later village communities (Birch 2012). Settlement aggregation may have been a temporary response to the transition to farming, settled village life, and the crystallization of social and territorial communities.

Beginning in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, sites were generally single component, with little overlapping of features and structures. Villages were occupied for approximately 20–30 years (Warrick 1988) before being relocated. In the greater Toronto area, relocations took place in a northeasterly direction, along the major waterways draining into Lake Ontario (Birch and Williamson 2013b; MacDonald 2002). In the context of an increasing commitment to horticulture, settlement moved off the easily tilled, sandy soils of the Lake Ontario plain and onto the more labor-intensive but drought-resistant clay loams immediately to the north (Dodd et al. 1990). These drainage-based territories also were catchment areas and, over the next 200–300 years, were the focus of site relocation sequences representing the development of autonomous community networks (MacDonald 2002; Williamson et al. 1998; Williamson and Robertson 1994).

The average length of longhouses increased during the 14th century, to over 100 m at the Coleman site in southwestern Ontario (MacDonald 1986) and at the Schoff and Howlett Hill sites in central New York (Tuck 1971). The general increase in longhouse size provides evidence for the expansion of co-residential, matrilineal household groups and may reflect communal functions or the development of prominent lineages that played important roles in guiding community affairs (Hayden 1976; Trigger 1990, p. 126). While there is no evidence for economic inequality in the precontact period, that does not preclude asymmetrical power relations between individuals, lineages, or clans (Birch and Williamson 2013a, pp. 161–162; Jamieson 1999, 2011).

The formation of larger co-residential populations and regional population increases coincided with the development of more formal social institutions within and between village communities. In south-central Ontario, the Uren site (Wright 1986) has long been held as the model for early 14th century “Middle” Iroquoian sites (i.e., Birch 2008; Warrick 2000). Its two clusters of aligned longhouses and double palisade are cited as evidence for the crystallization of formal matrilineages and the beginning of institutions such as subclans and village councils. We now have a much more extensive record of 14th and 15th-century settlement patterns, and while there is some regularity in settlement layouts, no one village is “typical” (Fig. 3).

Aligned groups of longhouses appeared on village sites in the late 13th and early 14th centuries (Fig. 3). They have traditionally been interpreted as households belonging to the same kin group or clan segment (Finlayson 1985, p. 172; Trigger 1985, p. 92; Warrick 1984, p. 35) or, in site relocation sequences, as previously distinct communities that merged into one settlement (Tuck 1971; Warrick 2008, pp. 136–137). They could very well be both (Birch 2008). If aligned clusters of longhouses do belong to clan segments, we might infer the increasing importance of clan-based sociopolitical organization and decision-making processes in village councils (Trigger 1985, p. 93; Warrick 2000, pp. 439–441). Clan exogamy and intermarriage between communities would have served to create ties of reciprocity and obligation between groups and may have been linked to cooperative subsistence activities, ceremonial functions, and mutual defense. There is no reason to believe, however, that political organization was uniform from one community to the next. Although the village community has been viewed as a maximal sociopolitical unit (Williamson and Robertson 1994), the recognition of the political autonomy of lineages and clan segments helps explain the dynamic settlement patterns of that time.

The size of mid-14th to early 15th century villages in south-central Ontario is highly variable, ranging between 0.4 and 3 ha (Birch 2012). Most villages are composed of two or more clusters of houses with different durations of occupation—for example, the Hope (ASI 2011) and Alexandra (ASI 2008) sites (Fig. 3H, I) each contain clusters of longhouses that were only partly contemporary. One subcommunity group clearly arrived at the village after a period of initial occupation by another group. Based on the small size of many late 14th and early 15th century site components (e.g., ASI 2003, 2006a, b), larger communities fissioned after a period of initial aggregation, opting for a more dispersed settlement strategy while perhaps retaining ties of affiliation (Birch and Williamson 2013a, p. 19).

Late 14th and early 15th century villages in south-central Ontario were generally not palisaded, although some contain fences or strategically placed longhouses that functioned to visually separate social units within communities (ASI 2008, 2011; Birch and Williamson 2013a, p. 20). Other evidence for conflict–butchered or modified human bone, skeletal trauma, defensive siting of settlements–also is absent. We might interpret this as a relatively peaceful period in Iroquoian history, contra ethnohistoric descriptions of Iroquoian people as inherently warlike (e.g., Fenton and Moore 1974, pp. 98–103; Thwaites 1896–1901, 43, p. 263). These groups likely had developed successful methods for ameliorating the tensions that contributed to the initial formation of larger, co-residential communities. These adaptive strategies included a high degree of settlement mobility and formalized mechanisms for regional interaction and local integration.

Interaction and integration

Between the late 13th and early 15th centuries, cultural practices emerge in southern Ontario that emphasize integration within communities and across the wider region, including communal ossuary burials, semisubterranean sweat lodges and, at the macroregional level, the proliferation of an elaborate smoking pipe complex. The writings of Gabriel Sagard (Wrong 1939) provide a 17th century account of an ossuary burial and the accompanying ceremony, called the Feast of the Dead. According to ethnohistoric accounts, the ceremony was the final act associated with village abandonment. It took place over several days and involved ritual feasting and the exchange of gifts. In this way, mortuary ceremonialism served to socially integrate both the living and the dead (Trigger 1969, pp. 102–112). Similar ceremonies were practiced by the Algonquian allies of the Wendat (Labelle 2013, pp. 71–72).

The earliest known ossuaries are at the Miller site, east of Toronto. They may have begun as family-oriented rites (Kenyon 1968, pp. 21–23; Spence 1994), but by the early 14th century, ossuaries became larger, community-wide features. Their creation sometimes also involved members of multiple allied villages in a joint burial ceremony (Williamson and Steiss 2003). The participating villages appear to belong to the same networks that shared drainage-based local territories and, in the next century, aggregated into large co-residential village communities (Birch 2012).

The 14th century Hutchinson site is a special purpose site consisting of two longhouses and separate mortuary areas that contain intact burials and the remains of at least 12 individuals (Robertson 2004). It is located across a small creek from the Staines Road ossuary, which contained the remains of 302 individuals from two or more nearby communities (Williamson and Steiss 2003, p. 102). The two sites are roughly contemporary, so it is possible that deceased relations of one or more communities were prepared at Hutchinson for the Feast of the Dead (Robertson 2004). This site is a caution to those who would interpret longhouses as strictly domestic structures, particularly in cases where total settlement plans and associated activity areas have not been revealed.

Although ossuary burial was the primary mortuary practice of ancestral and contact-period Wendat, isolated cemeteries also have been identified in association with late 15th and 16th century village sites, including Mantle (ASI 2014; Birch and Williamson 2013a, p. 153) and MacKenzie-Woodbridge (Saunders 1986). Such cemeteries may have been places for burying outsiders or peripheral individuals and others excluded from the ossuary due to death by violence, drowning, or freezing (Thwaites 1896–1901, v.39, p. 31). Primary interments and some multiple secondary burials were more common among the pre- and post-contact Haudenosaunee, Neutral, and St. Lawrence Iroquoians (Williamson and Steiss 2003), although a small number of possible ossuaries also have been identified at early Seneca sites (Niemczycki 1984, p. 122). The presence of multiple, discrete cemeteries at 16th and 17th-century Seneca sites suggests that supra-household groups within each community were buried in separate mortuary contexts (Sempowski and Saunders 2001; Wray et al. 1987, 1991). A wide-ranging analysis of Iroquoian mortuary practices might provide interesting insights into community-based identities and the multi-ethnic nature of Iroquoian communities.

Semisubterranean sweat lodges are common cultural features in Wendat and Neutral villages in the 14th and 15th centuries (ASI 2008; MacDonald 2002; MacDonald and Williamson 2001; Robertson and Williamson 2003). They are shallow, keyhole-shaped pits with a superstructure supported by posts within or attached to longhouses. Some contain ritually significant cultural materials and faunal specimens (MacDonald and Williamson 2001, p. 72; Ramsden et al. 1998, p. 73; Robertson et al. 1995, pp. 49–50; Thomas et al. 1998, pp. 94–95). Similar features of the same period identified at Late Woodland villages in western New York and the upper Susquehanna River valley may not have served identical functions (Hatch 1980; MacDonald 2008; Michaud-Stutzman 2009; Perrelli 2009). Ontario Iroquoian sweat lodges most served as venues for hosting kinsmen from within the village or wider social networks (MacDonald 1988; Robertson and Williamson 2003). Large numbers of sweat lodges are found on 15th century sites in Simcoe County, where they may have been important for hosting Algonquian hunting and trading partners (MacDonald and Williamson 2001, p. 71; Robertson and Williamson 2003, p. 50). Semisubterranean sweat lodges are rare on sites in Ontario after ca. 1450, largely replaced by aboveground sweat baths situated inside longhouses. Radiocarbon dates from Pennsylvania indicate that they remained in use into the 17th century (MacDonald 2008). In the middle Atlantic region, the function of these features is less certain, as they also have been interpreted as storage features or winter lodges (Bursey 2001; Hart 1995; MacDonald 2008).

The proliferation of an elaborate smoking pipe complex throughout Iroquoia during the late 14th century signals an increase in diplomatic relations and alliance formation (Finlayson 1998, pp. 409–411; Kuhn and Sempowski 2001; Wonderley 2005, p. 216). As easily transportable objects carried by individuals, potentially over long distances, pipes are a useful interaction marker among precontact eastern North American peoples (Drooker 2004; Kuhn and Sempowski 2001). Men were the primary users, and perhaps manufacturers, of smoking pipes (Braun 2012; Kuhn 2004, p. 153; Wonderley 2005, p. 213). While smoking was often a solitary pastime, pipes also were an important element of trade negotiations and council meetings. The Jesuits note that Wendat “never spoke of business nor came to any conclusion without having a pipe in their mouths,” believing that tobacco smoke imparted clarity of thought (Tooker 1964, p. 50; citing Thwaites 1896–1901, v.10, p. 219; v.15, p. 27). Some smoking pipes feature anthropomorphic and zoomorphic effigies or complex iconographic motifs (Noble 1979; Wonderley 2005). Pipes have been linked to curing societies and other ritual or spiritual practices (Noble 1979; Wright 2004, p. 1378) including shamanic transformation (Sempowski 2004) and, in the eastern Haudenosaunee area, to themes of emergence (Wonderley 2005) that echo the religious complexes of other eastern North American peoples. Pipes and the smoking of tobacco have considerable antiquity in the Eastern Woodlands. Given other material evidence for interregional interaction in 14th century Iroquoia, however, it seems likely that the florescence of the smoking pipe complex accompanied increased interaction among hunters, kinsmen, and trading partners in the context of population growth, expansion, and diplomatic relations.

In a characterization study of pipes and ceramic vessels from the 14th century Antrex site, Braun (2012) found that pots were made from a narrow and predictable range of raw materials, whereas pipes exhibited a much wider variety of manufacturing techniques, clay admixtures, and tempers—including organic materials and a high percentage of granite, which may have had symbolic meaning (pp. 4, 9). He interprets this as production by a wide range of individuals for personal use in ritual and social practices. As such, the seemingly individual activity of smoking tobacco can be interpreted as both self-directed and part of larger collective or integrative practices (see also Watts 2011). Ceramics and smoking pipes associated with Iroquoian populations in New York, however, did not appear at sites in Ontario and vice versa with any regularity until the 15th century (Birch et al. in press; Kuhn 2004). During the 14th century, interaction primarily took place between local populations on each side of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie, and perhaps across the Niagara Frontier. The cultural mechanisms that buffered tensions between Iroquoian communities in different subregions in the 14th and 15th centuries were insufficient to forestall the widespread eruption of violent conflict that characterized the mid-to-late 15th century throughout the Lower Great Lakes region.

Conflict

Rapid and profound changes occurred throughout Iroquoia during the late 15th and 16th centuries, including widespread conflict, the coalescence of small village communities into densely populated settlements of unprecedented size, population movement and geopolitical realignment, and the formation of organizationally complex sociopolitical entities. Although these patterns have long been recognized, data from individual site relocation sequences indicate that coalescence and conflict did not occur at precisely the same time or in precisely the same way in each community.

Conflict was integrated into Iroquoian culture through the ideological importance of blood revenge in maintaining spiritual balance (Richter 1992). Socially, warfare was an avenue for achieving manhood and accruing prestige (Snow 2007), while politically it provided a mechanism for social ranking (Birch 2010). While there is some evidence for violence in the 13th and 14th centuries (Engelbrecht 2003, pp. 39–41; Jenkins 2011; Rayner-Herter 2001; Wright 1986), conflict increased dramatically throughout Iroquoia during the mid-15th through early 16th century. Indirect evidence includes the creation of larger villages, presumably with greater numbers of warriors and the increased ability to defend villages and absorb losses (Keeley 1996, p. 129), the construction of formidable, multiple-row defensive palisades (Engelbrecht 2009) and earthworks (e.g., Anderson 2009; Squier 1851; Pendergast 1972; Wintemberg 1936), and the defensive situation of sites on hilltops or above steep slopes on the banks of creeks with access to key resources (Jones 2006, 2010b). Direct evidence comes from the significant quantities of butchered and modified human bone located in middens (Bradley 1987; Jenkins 2011; Williamson 2007; Wray et al. 1987, 1991) and pit features (Dupras and Pratte 1998; Helmuth 1993; Molto et al. 1986; Wray et al. 1987). Significant proportions of human bone recovered from midden contexts are cranial elements and provide evidence for the taking of trophy heads. At the Alhart site in western New York, 15 human skulls (all but one male) were recovered from a burned storage pit; the village may have been destroyed by a Seneca raid (Engelbrecht 2003, p. 132; Wray et al. 1987, pp. 247–248). At the coalescent sites of Draper and Keffer (Toronto area) and the Kirche site (Trent Valley), 52–71% of all human remains recovered from middens were cranial elements (Williamson 2007, p. 200). The translation of the Huron name for the house of the war-chief and where councils of war were held is “the house of cut-off heads” (Steckley 2007; Williamson 2007), which provides an additional link between the escalation of conflict, trophy taking, and the development of new forms of leadership. The performative qualities of artifacts made of human bone—gorgets, decorative hair pins and daggers, and rattles made of parietal bone—indicate that war-related performances and ornamentation served an integrative function in newly aggregated communities, connecting groups of unrelated males and directing hostilities outward against mutual enemies (Birch 2010).

Cross-culturally, rapid increases in population correlate, in a lagged fashion, with an increase in violent conflict (LeBlanc 2008; Turchin and Korotayev 2006). Mesquida and Wiener (1999) argue that a high ratio of men aged 15–29 to older men is an accurate predictor of war. In Iroquoia, population pressure and conflict over hunting territories (as opposed to arable land) may have been a factor that led to increased violence (Gramly 1977; Fitzgerald 2001; Hasenstab 1996b; Warrick 2008, pp. 141–142). Modeling of white-tailed deer populations and hide needs (Birch and Williamson 2013a, pp. 111–118) indicates that hide requirements may have outstripped local availability on the north shore of Lake Ontario by the early 15th century. Continued climatic cooling and instability of the Little Ice Age coupled with population growth also may have exacerbated social and political tensions (LeBlanc 2008), although this hypothesis requires supporting microregional climatic data (e.g., Cobb and Butler 2002, p. 637). The causes of conflict in late precontact Iroquoia also may have been related to social or cultural factors more complex than demographic or environmental ones (Keron 2008–2009, p. 133). It has traditionally been assumed that communities and war parties came under attack from distant enemies. Osteological and other data, however, indicate that some conflict may have been between nearer neighbors (Birch and Williamson 2013a, pp. 160–161; Engelbrecht 2003, p. 115; Robertson and Williamson 1998). Evidence for violence and settlement aggregation is so widespread that it is not immediately clear who was in conflict with whom. This remains a significant area for future research.

In south-central Ontario, conflict declined in the first decade of the 16th century (Birch and Williamson 2013a). Among the Onondaga, mid-16th century sites have less palisading, settlement locations shifted from exposed promontories to secondary elevations on plateaus and low ridges (Bradley 1987, p. 35), and intervisibility between sites is suggestive of alliance formation (Jones 2006).

This decrease in conflict may be associated with the “Great Peace” of Haudenosaunee oral history (Fenton 1998) and may be extended to a Pax Iroquoia given the lack of conflict in ancestral Wendat territory in the mid-16th century. Thus, the continued relocation of ancestral Wendat settlement off the north shore of Lake Ontario and the abandonment of the lower St. Lawrence Valley may have been caused by factors other than hostile relations between these groups and the Haudenosaunee, or they may have been affected by tensions that are not visible in the material record. It is clear that the endemic conflict of early 17th century Iroquoia was three generations removed from the conflict that led to 15th century coalescence. The eruption of warfare between the Wendat and Haudenosaunee in the mid-17th century was the result of a different set of historical circumstances, rather than a long-standing enmity between “traditional enemies” as has often been assumed. As such, future studies might productively investigate the different causes and forms of violence in the precontact and contact eras.

Coalescence

After AD 1450, there were fewer but larger village sites widely spaced on the landscape. Coalescence of, and the opening up of buffer zones between, communities is inexorably linked to the conflict described above. Connections engendered by the proximity of early 15th century communities—common resource extraction areas, trails, kinship, intermarriage, trade, and communal defense—influenced village amalgamation and relocation. Heterogeneous ceramic assemblages suggest that aggregated villages also included populations from farther afield (Birch et al. in press; Ramsden 1978, 1990b, c; Williamson et al. 1998; Wright 2004, p. 1390).

Coalescent communities share many characteristics, including a more structured built environment (Fig. 4), a concern for mutual defense, and a diverse range of nonlocal raw materials and ceramic types. Coalescent Iroquoian communities range in size from approximately 1.5–4 ha. Formative village aggregates include evidence of palisade expansion as new clusters of longhouses were added to existing settlement within the 20–40 year lifespan of 15th century village communities (Warrick 1988). Later, these aggregated communities relocated as whole, consolidated aggregates.

Iroquoian community patterns, ca. AD 1450–1650. Sites dating to ca. 1450–1500 that exhibit palisade expansion and the addition of new longhouses are formative aggregates. Later sites without palisade expansions represent consolidation. Depopulation is evident in the latest site plan in the series. Complete or relatively complete village plans selected to demonstrate variability and change over time: M Draper (Finlayson 1985); N Damiani (ASI 2012); O Keffer (Finlayson et al. 1987); P Kirche (Ramsden 1989); Q Garoga (Snow 1995a); R Mantle (ASI 2014; Birch and Williamson 2013a); S Ball (Knight 1987); T Hood (Lennox and Fitzgerald 1990)

On the northwestern shore of Lake Ontario, formative village aggregates include Parsons and Damiani on the Humber River (ASI 2012; Williamson et al. 1998), Keffer on the Don River (Finlayson et al. 1987), and Draper on West Duffins Creek (Finlayson 1985; see also Birch and Williamson 2013a). After ca. 1510, only two large consolidated communities remained, one on the Upper Humber River and one on West Duffins Creek that later relocated to the Holland River drainage.

In the Trent Valley, Coulter (Damkjar 1990) and Kirche (Ramsden 1989) exhibit palisade expansion and the incorporation of new house groups. Ceramic assemblages from these sites include significant quantities of ceramic types that originated in the Toronto area and the St. Lawrence Valley, indicating incorporation of people from the east and west (Ramsden 1989, 1990b). In the Upper St. Lawrence Valley, Roebuck (Wintemberg 1936), Maynard-McKeown (Pendergast 1988), and McIvor (Chapdelaine 1989) have expanded palisades and densely packed settlement patterns (see also Wright 1979). There is no evidence to date that precontact communities in historic Wendake, south of Georgian Bay, reached such large sizes, suggesting that the factors that drove coalescence were not felt as strongly to the north.

In New York, Tuck documented aggregation at the Burke site in Onondaga County around ca. 1480. Burke was surrounded by two intersecting palisades and contains superimposed longhouse features consistent with at least two phases of expansion (Tuck 1971, pp. 124–126, 139). Among the Onondaga, oral histories speak of the consolidation of small, dispersed villages into larger ones. These same histories indicate that 17th century Onondaga claimed the landscape inhabited by their ancestors as their exclusive hunting territories (Engelbrecht 2003, p. 121; Fenton 1998, p. 60; Tuck 1971, p. 216).

Settlement aggregation did not occur in the Mohawk Valley until the early 16th century (Funk and Kuhn 2003; Lenig 1998; Snow 1995a). Site location shifted from open, level lands to highly defensible positions protected by steep, elevated terrain, and water (Kuhn 2004, p. 159). After ca. 1500–1525, settlement splits into two (Snow 1995a) or three (Lenig 1998) communities in the western and eastern portions of the valley. The 16th century Garoga, Klock, and Smith-Pagerie sites were composed of 9–12 very long longhouses (Funk and Kuhn 2003) (Fig. 4Q).

Settlement aggregation among the Seneca and Cayuga occurred as much as a century later than community coalescence in southern Ontario and eastern New York (Niemczycki 1984; Wray and Schoff 1953). Sites are present between Seneca and Cayuga territory between 1450 and 1500 but not after. Among the ancestral Seneca, the consolidation of multiple village communities into the paired villages of Belcher and Richmond Mills, ca. 1525–1550, and later, Adams and Cuthbertson, ca. 1560–1575, has been interpreted as the crystallization of the Seneca as a unified political entity (Niemczycki 1984, pp. 92–93). Historically, the Seneca continued to occupy two major villages with one or more satellite villages into the 18th century. While proto-Cayuga sites were present east of Cayuga Lake as early as 1350, the first distinct Cayuga settlements appeared without antecedents on the southwest side of the lake ca. 1450 (Engelbrecht 2003, p. 119).

The Neutral sites of Lawson and MacPherson also were coalescent communities. Lawson, dating to the mid-to-late 15th century, had at least one palisade expansion, including the rebuilding of the earthwork surrounding the west side of the village (Anderson 2009; Wintemberg 1939). MacPherson, dating to the mid-16th century, consists of a core village surrounded by a palisade that was expanded twice to accommodate eight or more new longhouses (Fitzgerald 2001, p. 39; Lennox and Fitzgerald 1990). Although the factors influencing settlement aggregation played out differently for each Iroquoian group, the macroregional nature of the factors influencing coalescence is clear (e.g., Kowalewski 2006).

Organizational complexity in coalescent communities

The formation of large, densely populated communities created complex sociopolitical and economic settings. In southern Ontario, population estimates for late 15th and early 16th century sites vary from 600 to 1800 persons (Birch and Williamson 2013a, pp. 77–78, 177), compared to villages of 200–500 people in the 14th and early 15th centuries (Warrick 2008). Some 16th and 17th century sites in New York may have been even larger (Jones 2010a, c), though empirical data from settlement patterns are necessary to support these assertions. Given the physical size, population, and centrality of coalescent communities within the settlement landscape, Iroquoian “villages” might more accurately be called towns.

The social work involved in the formation and maintenance of such large co-residential communities would have been significant and complex (Kowalewski 2013). Community segments and their representatives entered into negotiations over the configuration of village infrastructure and access to space in densely packed palisaded enclosures, access to hunting territories, trade routes and the acquisition of nonlocal materials, land tenure, participation in and control of ceremonial and ritual activities, internal ranking and selection of spokespersons, and a host of other issues that required complex decision-making processes. In-depth analyses of the West Duffins Creek site sequence have provided insights into the social, political, and economic changes that occurred within a single community during the process of coalescence. There, eight small villages aggregated at the Draper site ca. 1450 and later relocated as a whole to Spang (ca. 1475), then Mantle (ca. 1500), and again to at least four subsequent sites (Birch 2012). At Mantle, community planning, central public spaces, specialized production, waste management, and long-distance interaction are evident in the material culture and built environment of the site which reveals a degree of social complexity that has been hidden from view in previous conceptualizations of precontact village organization (Birch and Williamson 2013b) and egalitarian constructs of Wendat society (see also Jamieson 2011).

While the material culture of formative aggregates is relatively cosmopolitan (Ramsden 1978; Williamson 2012), the diversity of material on 16th century consolidated aggregates is even more so. A comparison of frequencies of nonlocal ceramic types from early 16th century communities in Ontario and New York suggests that each community participated in unique networks of interaction and exchange (Birch and Williamson 2013a, pp. 139–140; Hart and Engelbrecht 2012; Wright 2004, p. 1390).

Complex decision making in large village communities would have included external affairs as well as more immediate management issues subject to considerable discussion and coordinated implementation. Paramount among these were assessments and maintenance of community infrastructure, agricultural field systems, and hunting and fishing strategies. Large village communities placed considerable strain on locally available resources. In addition to constant requirements for fuel and firewood, thousands of felled saplings and sheets of elm and cedar bark were required for constructing and covering houses and palisade maintenance. Construction and maintenance projects may have been coordinated with the clearing of new agricultural fields (Birch and Williamson 2013a, pp. 90–91).

Modeling the agricultural field systems of communities in the West Duffins Creek drainage, Birch and Williamson (2013a, pp. 95–103) suggest that the field systems of coalescent communities extended for 2 km in every direction by the time they were abandoned. These extensive agricultural field systems and associated resource extraction areas would have significantly taxed local environments. Jones and Wood (2012, p. 2599) suggest that population, as inferred from site size, was the single most important factor limiting village duration among the Haudenosaunee.

As noted above, competition over hunting territories may have been one factor driving the escalation of conflict in the 15th century. The procurement of deer, and to a lesser degree other animals, for hides to produce clothing—as opposed to meat—was a significant activity (Birch and Williamson 2013a, pp. 113–120; Gramly 1977). While it is possible that competition over hunting territories stimulated conflict in the 15th century, the inability to meet hide needs locally may have stimulated trade with adjacent Algonquian populations, as reflected in the long-standing trade relationships documented historically (Thwaites 1896–1901, v. 16, p. 227). Further evidence for subsistence change during the coalescent and post-coalescent periods in southern Ontario is the sharp decrease in the mean nitrogen isotopic values of people in the Mantle community, together with decreased fish remains on coalescent village sites compared to earlier communities (Birch and Williamson 2013a, pp. 110–112; Needs-Howarth and Williamson 2010; Pfeiffer et al. 2014). There is a need, however, for more research on how patterns of coalescence and conflict, as well as later cultural transformations, affected subsistence practices.

Complex processes regarding decision making, political economy, and organizational structure in large village aggregates necessitated the emergence of leaders and councils to guide community affairs (see Birch and Williamson 2013b). Among northeastern North American societies, leaders emerged not only through consensual processes, sometimes due to organizational necessity but also through agent-driven motivations and processes (e.g., ideological, ritual, economic) that centered dispersed social relations in places or persons (Pauketat 2010). This includes the potential for the development of asymmetrical social structures, dominated by individuals or groups in positions of influence who exercised authority in the civil and external domains (Hayden 1976; Jamieson 2011). Labelle (2013, pp. 17–25) describes the role of influential headmen and/or clan mothers who dominated civil affairs in Wendat society, positions that may have developed by the 15th century, or even earlier. Yet given the variability in the size, historical development, and interaction networks of each community, the actual nature of social relations and authority, together with relations of production and consumption in each community, nation, and confederacy, may have differed considerably as each responded to its own historically contingent challenges and opportunities during a period of widespread geopolitical and cultural change.

Geopolitical realignments and Iroquoian ethnicity

Despite recognition that individual communities underwent differentiated processes of development, the general skeleton of Iroquoian “tribalization” has undergone little change in the last 30-plus years: increased warfare led to larger communities, alliances between those communities, and the extension of those alliances into nations and confederacies (Engelbrecht 1995; Niemczycki 1988; Trigger 1976, pp. 162–163). New analyses and syntheses have demonstrated that while social and political relationships within and between Iroquoian communities were becoming more formalized and complex, both communities and so-called ‘tribal’ entities may have been more heterogeneous than was previously thought.