Abstract

The fatty acid profiles of the three lipid fractions, neutral lipids (NL), free fatty acids and polar lipids (PL), from the macroalgae Palmaria palmata (wild), Alaria esculenta (cultivated) and Saccharina latissima (cultivated) were studied in light of dietary important fatty acids. Blade and stipe from the macroalgae were collected at the end of the growth season (May/June) at Frøya (Trøndelag, Norway). A total of 51 fatty acids were identified in the algae, including several fatty acids novel to one or more of the algae. The NL and PL fractions of P. palmata were the most promising from a health perspective, due to a high content of eicosapentaenoic acid (10.1 ± 0.5% and 6.6 ± 0.1%, respectively) and no trans-fatty acids. In addition, these fractions had very low omega-6/omega-3 ratios (< 0.1) and can therefore be beneficial for balancing the omega-6/omega-3 ratio in the diet. The NL fraction of A. esculenta had the highest content of monounsaturated- and polyunsaturated fatty acids (20.9 ± 1.4 and 21.8 ± 1.9% of alga, respectively), as well as the highest content of the two essential fatty acids, linoleic acid (5.3 ± 0.4% of alga) and alpha-linolenic acid (2.4 ± 0.2% of alga). Indices related to risk factors for coronary heart disease were most favourable in the NL fraction of S. latissima and the NL and PL fractions of A. esculenta.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The red alga Palmaria palmata and the brown algae Alaria esculenta and Saccharina latissima are edible macroalgae suitable for human consumption. The species are native to the North Atlantic. Kelp species, particularly S. latissima, but also A. esculenta, are the focus of large-scale cultivation in Europe (Stévant et al. 2017). Saccharina latissima is marketed both as food and feed, while A. esculenta is used as a “sea vegetable” and considered to be a high value food ingredient (Stévant et al. 2017). Palmaria palmata is one of the most commonly eaten seaweeds native to the North Atlantic, with a taste that is suited to the western palate (Mouritsen et al. 2013). Both S. latissima and P. palmata are reported to be rich in the sought-after umami flavour (Mouritsen et al. 2012).

Macroalgal biomass is considered a sustainable resource; the biomass grows at a very fast rate and can be harvested from wild stock or cultivated without or with only minimal use of limited resources such as nutrients (Ghadiryanfar et al. 2016). The lipid fraction of macroalgae is rich in omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) beneficial for human health (FAO 2010). The fatty acid profiles of these algae have been reported previously, but mainly based on total lipid extracts (Mouritsen et al. 2013; Mæhre et al. 2014; Schmid and Stengel 2015; Biancarosa et al. 2018; Fernandes et al. 2018), or with focus on molecular species of individual lipids classes and their bioactivity, e.g. Lopes et al. (2019) and Banskota et al. (2014). Fatty acids naturally exist either in free form (free fatty acids), esterified to glycerol backbones (neutral lipids, mainly triacylglycerides) or esterified to a backbone with a polar headgroup (polar lipids). In macroalgae, the polar lipid class mainly consists of glyceroglycolipids and glycerophospholipids (Harwood 1998). The mechanisms behind the bioavailability of fatty acids are still disputed, but their lipid structure is believed to be of high importance (Cholewski et al. 2018). Polar lipid omega-3 PUFA are reported as more bioavailable than omega-3 PUFA esterified to triacylglycerols, which again are more bioavailable than free fatty acid omega-3 PUFA (Burri et al. 2012; Cholewski et al. 2018). Separation into lipid classes can thus give more information than total lipid extracts.

Analysis of lipid fractions has previously been reported for P. palmata from the French Brittany coast (March) by Fleurence et al. (1994), from Nova Scotia, Canada, (July–August) by Mishra et al. (1993) and from Ireland by Robertson et al. (2015) (March) and Schmid et al. (2017b) (May and October). Saccharina latissima harvested in March from the French Brittany coast was also analysed and fractionated by Fleurence et al. (1994). These studies reported relatively limited profiles (≤ 17 fatty acids). Few publications with analysis of the fatty acids profiles of A. esculenata are reported in the literature, and none with fractionation. Comprehensive fatty acid profiles with comparison of these lipid fractions both within and between these algae species are thus not found in the literature. While taxonomical differences can be expected, the comparison of algae harvested at the same time in the same area is of particular interest, as this limits variations due to environmental and ecological conditions.

As the health implications of fatty acids become more and more focused on the effects of individual fatty acids, lipid extracts with varying fatty acids profiles become more attractive. In addition, the bioavailability of the fatty acids can then be alluded. We chose to separate our lipid extracts into neutral lipids (NL), free fatty acids (FFA) and polar lipids (PL). Our hypothesis was that the different fractions would yield significantly different fatty acid profiles, with varying relative amounts of the individual fatty acids. Our objective was to compare the fatty acid profiles in these fractions, both within and between the three algae, with a focus on dietary important fatty acids. The fatty acid profiles of the different fractions were also assessed according to risk factors connected to coronary heart disease.

Material and methods

Sampling and sample pretreatment

Samples of Palmaria palmata (red alga), Alaria esculenta (brown alga) and Saccharina latissima (brown alga) harvested at the end of the growth season were bought from Seaweed Energy Solutions AS (Trondheim, Norway). Alaria esculenta and S. latissima were cultivated on ropes deployed in August 2017 and March 2018, respectively, at a seaweed farm at Taraskjæret at Frøya (Trøndelag County, Norway). They were harvested by hand 1 June 2018 and 27 May 2018, respectively. Wild P. palmata was harvest by hand in Hammarvika at Frøya (Trøndelag County, Norway) the 26 May 2018 (several plants, collected in a 1600 m2 area). For each species, 1 kg alga was collected. The sea temperature for the area was between 9 and 12 °C in the end of May/beginning of June, recorded at the official observation stations “Heidrun” and “Ormen Lange” (Norwegian Centre for Climate Services 2018).

The samples were frozen (− 20 °C) immediately at arrival on company site (after boat trip to land and 3 h drive), shipped frozen and kept at − 24 °C until pretreatment. The samples were thawed, and excess moisture removed by patting with paper. No epiphytes were present. The stipe and blade of each alga were analysed together, while the holdfast was discarded. The collected 1 kg of each alga species was treated as one sample. The thawed samples were cut into small pieces (< 1 cm3), frozen with liquid nitrogen (99.9990%, AGA, the Linde Group, Germany) and freeze-dried (Alpha 2-4 LD plus, Martin Christ Gefriertrocknungsanlagen GmbH, Germany). A powder (< 1 mm2) was made by milling the freeze-dried algae with a Retsch SM 2000 mill (Retsch GmbH, Germany). Three technical replicates were used for P. palmata and four each for both A. esculenta and S. latissima.

Lipid extraction and determination of total lipid content

Lipids were extracted by a modified Folch method (Folch et al. 1957) as reported previously (Foseid et al. 2017). Chloroform and methanol of HiPerSolv CHROMANORM quality were used (VWR part of Avantor, USA). A sample blank was “extracted” simultaneously with each alga, in addition to the technical replicates. In short, the lipids were extracted by adding 100 mL chloroform/methanol (2:1 by vol) and 5.0 g alga to a 250 mL borosilicate flask (VWR part of Avantor, USA). The mixture was shaken for 20 min at 220 rpm on an orbital shaker (PSU-10i, Biosan, Latvia), before being transferred to separatory funnels. Phase separation was induced by addition of 20.0 mL 0.9% (by vol) NaCl in deionized water. The flasks were gently shaken and left to settle for 20 min. The organic phases (66 mL) were transferred to vacuum evaporation tubes (Buchi Labortechnic AG, Switzerland). The polar phase of each replica was re-extracted twice with further 66 mL chloroform. The organic phases of each replica were combined before evaporation at 40 °C with a vacuum evaporator (Q-101, Buchi Labortechnic AG). The samples were evaporated to dryness, redissolved in 1.0 mL chloroform and transferred to microtubes (MCT-150-C, Axygen, Corning, USA) for centrifugation. The samples were centrifuged at 16112×g for 5 min. The supernatant was transferred to new microtubes and evaporated to dryness, allowing for gravimetrical determination of the total lipid content. Afterwards the samples were redissolved in 1.0 mL chloroform, transferred to GC-MS vials and stored cold (− 24 °C) prior to solid phase extraction.

Solid phase extraction

The extracted lipids were fractionated into three fractions: neutral lipids (NL), free fatty acids (FFA) and polar lipids (PL) with the help of a liquid handling robot (Gilson, GX-271, ASPEC, USA), as reported previously (Foseid et al. 2017). The solid phase extraction (SPE) method was based on work by Pinkart et al. (1998) and Ruiz et al. (2004) and adapted by Devle et al. (2014). In method adaptation, the cross-contamination between the three lipid classes was checked by tests with standards (Devle et al. 2014). Recovery was 90% or higher. The chloroform, methanol and n-heptane were of HiPerSolv CHROMANORM quality, diethyl ether and sodium chloride of AnalaR NORMAPUR quality, and the acetic acid and 2-propanol were of RECTAPUR quality, all from VWR (VWR part of Avantor, USA). In short, the aminopropyl-modified silica phase SPE columns (Chromabond, 500 mg, 3 mL, Machery-Nagel, Germany) were preconditioned with 7.5 mL n-heptane before 500.0 μL sample was applied. The three lipid fractions were sequentially eluted by addition of 5.0 mL chloroform, 5.0 mL diethyl ether:acetic acid (98:2 by vol) and 5.0 mL methanol, eluting NL, FFA and PL respectively. A flow of 1.0 mL min−1 was employed. Each fraction was then evaporated to dryness at 40 °C under N2 (g).

Formation of fatty acid methyl esters

The extracted lipids were esterified/transesterified to fatty acid methyl esters as reported previously (Foseid et al. 2017). In short, the NL and PL fractions were redissolved in 2 mL n-heptane (HiPerSolv CHROMANORM quality, VWR), while the FFA fractions were redissolved in 1 mL boron trifluoride-methanol solution (14%, Merck KGaA, Germany). Sodium methoxide, 3.3 mg mL−1, was made by dissolving metallic sodium (Merck) in methanol (HiPerSolv CHROMANORM quality, VWR). 1.5 mL of the sodium methoxide solution was added to the NL and PL fractions and the samples were shaken horizontally for 30 min at 350 rpm (Biosan Ltd., PSU-10i, Latvia), then left to settle for 10 min. The heptane phases were transferred to vials and stored at − 24 °C. The FFA fractions were heated in a water bath for 5 min at 70 °C, 1 mL n-heptane was then added and the samples mixed with a vortex mixer. The heptane phases were transferred to vials and stored at − 24 °C prior to GC-MS analysis.

Standards

A 37-component fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) mix was used (Food Industry FAME MIX, Restek Corporation, USA) for identification of the FAME. In addition, several individual standards were employed; heptadecanoic acid methyl ester and nonadecanoic acid methyl ester, both from Fluka (Germany), 13-methyl-tetradecanoic acid methyl ester, cis-7-hexadecenoic acid methyl ester, cis-11-octadecenoic acid methyl ester, all-cis-6,9,12,15-octadecatetraenoic acid methyl ester and all-cis-8,11,14,17-eicosatetraenoic acid methyl ester, all from Larodan AB (Solna, Sweden).

Identification and relative quantitation of FAME by GC-MS

The analysis method was as previously published (Devle et al. 2009; Foseid et al. 2017). The analysis was carried out on an Agilent 6890 Series gas chromatograph (GC; Agilent Technology, USA) with a CTC PAL autosampler (CTC Analytics, AG, Switzerland). A 60 m Restek column (Rtx-2330) with 0.24 mm ID and a 0.2 μm film thickness was used. The stationary phase was a fused silica with 90% biscyanopropyl and 10% phenylcyanopropyl polysiloxane (Restek Corporation). A transfer line temperature of 270 °C was used. A sample volume of 1.0 μL was injected with a split ratio of 1:10. Helium (HiQ 99.99990%, AGA, Germany) was used as carrier gas with a constant flow of 1.0 mL min−1. A 92-min temperature program was used starting with 65 °C for 3 min, which was then raised 40 °C min−1 to 150 °C, held for 13 min, then increased to 151 °C (2 °C min−1), held for 20 min, then increased to 230 °C (2 °C min−1) and held for 10 min, and lastly increased to 240 °C (50 °C min−1) and held for 3.7 min.

The GC was coupled with an Autospec Ultima mass spectrometer (MS; Micromass Ltd., England), a sector instrument with electrostatic-magnetic-electrostatic (EBE)-geometry. An EI ion source was used at 250 °C in positive mode, producing 70 eV electrons. The scan range was 40–600 m/z with 0.3 s scan time and 0.2 s interscan delay. The resolution of the mass spectrometer was set to 1000. MassLynx version 4.0 (Waters, USA) and NIST 2017 Mass Spectral Library v. 2.2 (Gaithersburg, USA) were used. A combination of library searches and comparison of retention time with external standards was employed for identification. Fatty acids identified by library search only are marked with a superscript letter in all tables and figures.

Data analysis and statistics

Fatty acid concentrations are expressed as percentage of total fatty acids (mean of the three technical replicates + standard deviation (SD)). In other words; the sum of the NL, FFA and PL fraction of each alga is 100%, as this allows for easy comparison of the fractions both within and between the algae. Additionally, the relative amounts of summarized saturated fatty acids (SFA), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), PUFA, NL, FFA and PL, as well as omega-6/omega-3 ratio, were calculated for each alga.

The atherogenic index (AI), thrombogenic index (TI) and hypocholesterolemic indix (HI) (or hypocholerosterolemic/Hypercholesterolemich ratio) were calculated to assess the fat composition in regard to risk factors for coronary heart disease. AI and TI were calculated according to Ulbricht and Southgate (1991):

HI was calculated according to Fernández et al. (2007):

where

and

A principal component analysis (PCA) was performed based on results for the ten most abundant fatty acids. These fatty acids contributed with more than 1.0% in at least one fraction, and in total, they constituted more than 90% of total fatty acids in the algae. The analysis was performed with RStudio (RStudio Team 2019) utilizing the tidyverse package (Wickham et al. 2019).

Results

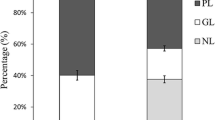

In total, 51 fatty acids were identified in the algae samples, consisting of between 7–24 carbon atoms, and 0–6 double bonds. Of these, 17 fatty acids were saturated, 19 monounsaturated and 15 polyunsaturated. The fatty acids all had cis configuration (with two exceptions, see section on “Minor fatty acids”) and 42 out of 51 had an even number of carbon atoms. The total fatty acid profiles are shown in Online Resource 1 (SFA), 2 (MUFA) and 3 (PUFA). The total lipid contents for P. palmata, A. esculenta and S. latissima were 2.8 ± 0.1%, 1.1 ± 0.1% and 2.4 ± 0.3% (percent of dry weight (DW), mean ± 1 SD), respectively. The NL, FFA and PL distributions varied significantly between the algae (Fig. 1a). The overall proportion of SFA, MUFA and PUFA for the three algae species is shown in Fig. 1b.

a The distribution (%) of the lipid fractions; neutral lipids (NL), free fatty acids (FFA) and polar lipids (PL), and b the proportion of saturated fatty acids (SFA), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), both for P. palmata (3 technical replicates for each fraction), A. esculenta (4 technical replicates for each fraction) and S. latissima (4 technical replicates for each fraction). Error bars represent ± 1 SD

The FFA and PL fractions of A. esculenta and the NL and PL fraction of S. latissima had significantly lower SFA content (< 11%) than the other fractions (> 19%) (Fig. 2a). The MUFA content was generally low (2.2–6.3%) and similar between the fractions, the exceptions were the NL fraction of A. esculenta (20.9 ± 1.4%), and the FFA fraction of S. latissima (12.4 ± 0.2%) (Fig. 2b). The PUFA distribution (Fig. 2c) was more varied but displayed some trends; the FFA fractions had the lowest PUFA content and the NL fractions the highest content for all three species. The FFA fractions of P. palmata and A. esculenta were particularly low in PUFA content (≤ 3.1%). The NL fraction of A. esculenta had the highest amount of PUFA (21.8 ± 1.9%). It also had the highest percentage of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids (Fig. 2d and e). For all the algae, the omega-3 content was highest in the NL fractions and lowest in the FFA fractions. The omega-6 content showed several between-fraction similarities, especially for P. palmata and S. latissima, while for A. esculenta, the variation between the fractions was significant ranging from 0.8 ± 0.1% in the FFA fraction to 10.0 ± 0.8% in the NL fraction. The omega-6/omega-3 ratio was low in all fractions (≤ 1.4), but particularly low (≤ 0.3) in the fractions of P. palmata (Fig. 2f).

The fraction distribution for a saturated fatty acids (SFA), b monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), c polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), d omega-3, e omega-6 and f omega-6/omega-3 ratio, for P. palmata (3 technical replicates for each fraction), A. esculenta (4 technical replicates for each fraction) and S. latissima (4 technical replicates for each fraction)

Major fatty acids

Ten of the fatty acids contributed with more than 90% of the total fatty acid content (Fig. 3). Nonetheless, there were significant variations in their relative content. Palmitic acid (C16:0), oleic acid (C18:1cis9) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; C20:5cis5,8,11,14,17) contributed significantly (1.0–21.1%) in each fraction, while the contribution from myristic acid (C14:0), stearic acid (C18:0), palmitoleic acid (C16:1cis9), linoleic acid (LNA, C18:2cis9,12), alpha linolenic acid (ALA, C18:3cis9,12,15), stearidonic acid (SDA, C18:4cis6,9,12,15) and arachidonic acid (ARA, C20:4cis5,8,11,14) varied from 0.1 to 9.3% depending on the fatty acid and the fraction.

The ten most abundant fatty acids (%), in the neutral lipid (NL), free fatty acid (FFA) and polar lipid (PL) fractions of P. palmata (3 technical replicates for each fraction), A. esculenta (4 technical replicates for each fraction) and S. latissima (4 technical replicates for each fraction). For easier comparison of profiles within and between the algae, the FA percentages were calculated so that the sum of the NL, FFA and PL fractions of each alga amounts to a hundred percent. LNA, linoleic acid; ALA, alpha-linolenic acid; SDA, stearidonic acid; ARA, arachidonic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; Σ(remaining fatty acids), summarized contribution from the remaining fatty acids

The highest content of myristic was found in the FFA and PL fractions of S. latissima (9.3 ± 0.3 and 6.1 ± 0.2%, respectively) and the NL fraction of A. esculenta (5.3 ± 0.4%). Palmitic acid predominated in 6 out of the 9 fractions. The exceptions were the NL and PL fractions of S. latissima where EPA and myristic acid were the most abundant, respectively, and the PL fraction of A. esculenta where EPA predominated. Palmaria palmata generally had a very high content (> 13.2%) of palmitic acid in all fractions. Alaria esculenta had a high palmitic acid content in the NL fraction (18.6%) and low in the FFA and PL fractions (< 3.5%). Saccharina latissima had the highest content in the FFA fraction (14.6%) and lower in the NL and PL fractions (< 4.0%). Stearic acid was generally low in all the fractions (≤ 3.1%), but especially in the PL fractions (≤ 0.5%).

The highest palmitoleic and oleic content was found in the NL fraction of A. esculenta. All fractions of the three algae contained the two essential fatty acids: LNA and ALA, the best source being the NL fraction of A. esculenta which had both the highest LNA (5.3 ± 0.4%) and ALA (2.4 ± 0.2%) content. The highest SDA and ARA content (≥ 2.2% and ≥ 2.3%, respectively) was found in the NL and PL fractions of both A. esculenta and S. latissima. The contribution of EPA varied considerably between and within the fractions, from 1.0 ± < 0.0% in the FFA fraction of P. palmata to 10.1 ± 0.5% in the NL fraction of P. palmata (Fig. 3). Overall, P. palmata had the highest abundance of EPA, followed by A. esculenta and then S. latissima.

To assess the similarities and differences between the fractions both within and between the algae, a PCA plot based on the ten predominating fatty acids was made (Fig. 4). The first and second dimensions of the PCA explain 66.5 and 19.7% of the variation respectively. The fractions of P. palmata were clearly clustered in their own region, but not very close together. Their placement away from the other fractions was mainly explained by higher EPA and palmitic acid content (PCA loading plot, data not shown). For A. esculenta and S. latissima, the picture was more complicated. The PL fraction of A. esculenta and the NL fraction of S. latissima were the two closest grouped fractions, regardless of algal species. The FFA fraction of A. esculenta and the PL fraction of S. latissima were also close to this grouping. Their NL and FFA fractions (A. esculenta and S. latissima, respectively), however, were further away, this was largely due to the higher content of oleic and palmitic acid in these fractions (PCA loading plot, data not shown).

PCA plot based on the ten most abundant fatty acids in each fraction of P. palmata (3 technical replicates for each fraction), A. esculenta (4 technical replicates for each fraction) and S. latissima (4 technical replicates for each fraction). NL, neutral lipid; FFA, free fatty acid; PL, polar lipid

The atherogenic index (AI), the thrombogenic index (TI) and the hypocholesterolemic index (HI) were calculated to better understand the effects of fat intake from the studied algae fractions on risk factors for coronary heart disease and can be found in Online Resource 3.

Minor fatty acids

In addition to the major fatty acids, between 14 and 27 other fatty acids were identified in each fraction, see Online Resource 1, 2 and 3. These fatty acids each contributed less than 1% of the total fatty acid profile for each species. Amongst these were several fatty acids with odd-numbered carbon chains (e.g. C15:0 and C17:0) and mono- or poly-unsaturated fatty acids with less common double bond positions. Two trans-fatty acids, C16:2trans7,10 and C16:2trans9,12, were also identified in all fractions of A. esculenta and S. latissima, as well as in the FFA fraction of P. palmata. In addition, 3,7,11,15tetramethyl-C16:1cis/trans2 was found in the FFA fraction of P. palmata. The geometric isomerism of this fatty acid was undetermined. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; C22:6cis4,7,10,13,16,19) was identified in all fractions of A. esculenta and S. latissima, but not found at all in P. palmata. The highest DHA content was found in A. esculenta (0.2 ± < 0.0% in all fractions).

The minor fatty acids also include novel fatty acids that have not, to our knowledge, been reported in P. palmata, A. esculenta or S. latissima previously, namely C7:0, C13:0 and C16:2trans9,12. Additionally, C9:0, C11:0, C14:0 iso-methyl, 3,7,11,15-tetramethyl-C16:1cis/trans2, C24:1cis15 and C16:4cis6,9,12,15 in P. palmata, C9:0, C14:0 iso-methyl, C20:0, C21:0, C22:0, C16:1cis7, C16:1cis11, C22:1cis11, C22:1cis13 and C16:2trans7,10 in A. esculenta, and C7:1cis4, C14:1cis11, C16:1cis7, C16:1cis11, C17cyclic, C16:2trans7,10, C18:2cis8,11 and C22:2cis13,15 in S. latissima are novel.

Discussion

This study compared the fatty acid profiles of the fractionated lipid extracts from three macroalgae sampled by hand in the end of May/beginning of June at Frøya, Norway. Algae collected from one location at a single time point with pooled biomass samples were chosen. Industrially speaking pooled samples are very relevant; however, we acknowledge that the separate analysis of several individual specimens would have allowed for statistical testing of significance. Additionally, several sampling times would have allowed for appreciation of the seasonal variation. However, the results presented here show the average of several specimens (1 kg of biomass was collected for each alga) and thus gives an indication of the expected profile for algae from this location. Comparison of the fatty acid profiles of the alga species was especially relevant as they have been exposed to very similar growth conditions. In addition, the algae were collected at what is reported as peak biomass growth (late spring) and before the onset of epiphytes and biomass loss in summer (Handå et al. 2013). Somewhat contrastingly the highest total lipid content and highest proportions of PUFA have been reported for P. palmata during the winter/early spring months (Schmid et al. 2017a), potentially making the choice in harvesting time a trade-off between optimal fatty acid composition and biomass amount.

Alaria esculenta and S. latissima are both of the phylum Ochrophyta, class Phaeophyceae (brown algae) and order Laminariales. It was therefore expected that their fatty acid distributions were more similar compared with that of the red alga P. palmata (phylum Rhodophyta, order Palmariales). Galloway et al. (2012) conducted statistical analysis on the link between macrophyte phylogeny (phylum, order, family etc.) and fatty acid profiles. Their results showed that brown and red algae had similar content of ARA and EPA and differed in abundance of palmitic acid and stearic acid, mainly through a lack of these FAs in brown algae. Galloway et al. (2012) also report that brown algae had relatively high (~ 5–15%) LNA, ALA and SDA abundance, while red algae had low percentages (~ 1%) for the same FAs. Our data were not consistently in agreement with these observations. The EPA distribution in our algae was as expected according to Galloway et al.’s (2012) results, while the 16–22 times higher ARA content in the brown algae compared with the red alga was not. In addition, while P. palmata had the overall highest content of palmitic acid (50.26 ± 2.47%), the total contents in A. esculenta and S. latissima at above 20% cannot be described as a “low or lacking”. The palmitic acid content in our study is however in agreement with reports for other brown algae species (Pereira et al. 2012). As for the stearic acid content, the distribution between the algae was varied with no clear trend between the brown or red algae (Fig. 3). Palmaria palmata had an overall low abundance of LNA, ALA and SDA (< 0.7%), and A. esculenta and S. latissima had overall significantly higher abundances (3.0–7.8%). This is thus in agreement with Galloway et al. (2012). The results presented here also showed that the two brown algae had similar proportions of SFA, MUFA and PUFA (Fig. 1b), and higher omega-6 content than P. palmata (Fig. 2e).

It is important to note that variability of the fatty acid profiles of algae is dependent not only on taxonomy but also on environmental and ecological factors such as seasons, sampling site location, nutrient availability, epiphyte abundance, irradiance and salinity (Floreto et al. 1993; Xu et al. 1998; Denis et al. 2010; Stengel et al. 2011; Venkatesalu et al. 2012; Khairy and El-Shafay 2013; Schmid et al. 2014, 2017a, b; Gosch et al. 2015; Marinho et al. 2015; Serviere-Zaragoza et al. 2015; Shaltout and El-Din 2015; Vilg et al. 2015; Balboa et al. 2016; Fariman et al. 2016; Koch et al. 2016; Barbosa et al. 2017; Mohy El-Din 2018; Praiboon et al. 2018; da Costa et al. 2019; Monteiro et al. 2020).

Another recent study looked at lipidomic signatures as a way of identifying geographic origin in S. latissima, by comparing samples from France, the United Kingdom (UK) and Norway (Monteiro et al. 2020). The Norwegian samples from this study, along with the S. latissima samples in Rey et al. (2019), and also our study, were all harvested at Frøya (Norway). They were harvested in April 2017, May 2016 and May 2018, respectively. Monteiro et al. (2020) found significant differences between the content of several fatty acids in the Norwegian, UK and French samples. However, when comparing the Norwegian samples in all three studies, one can find several examples of variation in individual fatty acid content which clearly supersedes the variation found when comparing the same fatty acids in the three geographical locations Norway, France and UK. This of course does not invalidate the use of lipidomic signatures for identification of geographic origin, as those signatures are based on more than the content of individual fatty acids. Yet, it provides a powerful example of how the fatty acid distributions in samples of the same species of alga collected in the same location (by the same company), in the same time of year can still differ significantly, and how the knowledge of such variation is important.

The predominating ten fatty acids (combined they contributed with more than 90% in all alga) was largely in agreement with the published data for P. palmata, A. esculenta and S. latissima (e.g. Mæhre et al. 2014; Schmid and Stengel 2015; Schmid et al. 2016; Biancarosa et al. 2018; Neto et al. 2018). The largest deviations from the literature were found in P. palmata, where the samples from our study had roughly twice the total palmitic acid content (50.3 ± 2.5%) and half the total EPA content (17.7 ± 0.6%) of what is largely reported elsewhere (Graeve et al. 2002; van Ginneken et al. 2011; Mæhre et al. 2014; Robertson et al. 2015; Schmid et al. 2016; Biancarosa et al. 2018; Lopes et al. 2019). However, Mouritsen et al. (2013) showed that the variation between harvesting location could mean drastically different fatty acid profiles with EPA varying from 1.76% (Maine, USA) to 59.69% (Denmark).

Lipid fractions and health perspectives

The potential health effects of fatty acids are dependent on their bioavailability, which amongst other things can be related to their lipid structure (Cholewski et al. 2018). Glyceroglycolipids are the most abundant lipids in macroalgae (Harwood 1998; Hölzl and Dörmann 2007). In this context, the overall low PL content of the algae was surprising (Fig. 1a). For P. palmata, this is not in agreement with previous literature (Mishra et al. 1993; Fleurence et al. 1994; Robertson et al. 2015; Schmid et al. 2017b). Fleurence et al. (1994) reported 64.7% of fatty acids in the NL fraction of S. latissima; however, this fraction may also include the free fatty acids, regardless the PL fraction content (35.3%) is similar to what is reported in our study. For A. esculenta, there are no published studies with lipid fractionation to compare with. The PCA plot indicated that some aspects of the fatty acid distributions in A. esculenta and S. latissima were more similar to each other than to that of P. palmata (Fig. 4). However, as the variation between the fractions can be larger than the variation between the algae, this is not conclusive. For A. esculenta, the FFA and PL fractions were quite close together, while for S. latissima, it was the NL and PL fractions that were clustered; thus, there was no clear pattern in which fractions had the most similar fatty acid profiles. P. palmata was the alga with the closest clustering of the fractions, thus indicating the smallest variation between them.

Considering overall SFA, MUFA and PUFA content, A. esculenta had the most favourable composition with the lowest relative amount of SFA and the highest relative amount of PUFA (Fig. 1b). Replacing SFA in the diet with MUFA, or more preferably PUFA, is reported to be good for cardiovascular health (FAO 2010). Saccharina latissima was similar to A. esculenta in terms of PUFA content but had a higher SFA content. Palmaria palmata had the highest SFA content and lowest PUFA content and was thus in this regard the least favourable. For A. esculenta and S. latissima, the overall distribution between SFA, MUFA and PUFA is in accordance with previously published data for brown algae in general (Pereira et al. 2012) and Laminariales in particular (Dawczynski et al. 2007). For red alga, the distribution has been shown to be more species dependent (Pereira et al. 2012), and P. palmata had higher SFA and lower PUFA content that what is generally reported, as discussed above with regard to palmitic acid and EPA content. Nonetheless, an overall higher SFA content in red algae than brown has been reported (Dawczynski et al. 2007). When considering the fractions, it was the FFA and PL fractions of A. esculenta and the NL and PL fractions of S. latissima that had the most desirable SFA composition (≤ 11%) from a dietary point of view (Fig. 2a). The highest PUFA contents were found in the NL fractions making them the most desirable from a dietary perspective (Fig. 2c).

The macroalgae all contained the essential fatty acids, LNA and ALA, whose absence from the diet will lead to deficiency syndromes (FAO 2010). The highest content was found in the NL fraction of A. esculenta, while P. palmata had particularly low contents (≤ 0.4%) in all fractions (Fig. 3). ALA is a precursor for EPA and DHA synthesis in the body. However, this synthesis is limited, especially with regard to conversion to DHA. In addition, the conversion efficiency is impacted by the omega-6/omega-3 ratio, as omega-6 fatty acids compete for the same elongation and desaturation enzymes (Robertson et al. 2013). SDA is an intermediate in the synthesis pathway from ALA to EPA. Supplementation of SDA can thus increase the EPA concentration in the body as conversion from SDA is more efficient than that from ALA (Walker et al. 2013). SDA was identified in all the fractions of all three species, and the highest contents were found in the NL and PL fractions of A. esculenta and S. latissima.

EPA and DHA are of special dietary interest due to their importance for visual and cognitive development and function, as well as their positive effects on inflammatory-related diseases (Zárate et al. 2017). The appreciation of these three macroalgae as good sources of EPA agrees with previously published literature (e.g. Mæhre et al. 2014; Schmid and Stengel 2015; Schmid et al. 2016; Biancarosa et al. 2018). It is interesting to note that the highest percentages of EPA for each alga were found in the NL fractions, followed by the PL and then the FFA fractions (Fig. 3). Our results therefore indicated that EPA was bound to acylglycerides in a higher degree than to polar lipids. However, this is not in agreement with previously published data for P. palmata, where the EPA amounts were higher in the PL than in the NL fraction (Mishra et al. 1993; Fleurence et al. 1994; Schmid et al. 2017b). For S. latissima, Fleurence et al. (1994) reported that EPA was almost equally distributed in the NL and PL fractions (~ 3%).

Omega-3 fatty acids are reported to have anti-inflammatory properties. Their intake can thus be beneficial for both prevention and treatment of inflammatory diseases such as allergies, asthma, arthritis, neurodegenerative disorders and autoimmune diseases, but also diseases with inflammatory symptoms such as, diabetes, obesity and cancers (Robertson et al. 2013; Zárate et al. 2017). As sources of omega-3 PUFA, P. palmata and A. esculenta had the highest overall contents (19.0 ± 0.7 and 21.3 ± 2.0%, respectively), with the NL fractions being the largest contributors with 10.4 ± 0.5 and 11.6 ± 1.0% respectively (Fig. 2d). Alaria esculenta and S. latissima had the highest total omega-6 contents (14.8 ± 1.3 and 17.6 ± 0.9%, respectively), while the total omega-6 content in P. palmata was significantly lower (1.3 ± 0.1%) (Fig. 2e). The FAO does not have specific recommendations for omega-6/omega-3 ratio, other than set recommendations for intake of LNA (2.5% of calories) and omega-3 PUFA (ALA, EPA and DHA; 0.5–2% of calories) (FAO 2010). However, it is known that the western diet is generally too high in omega-6 intake (mainly through vegetable oils high in LNA content) and too low in omega-3 intake (ALA, EPA and DHA from marine sources) (Simopoulos 2002). The algae all had low omega-6/omega-3 ratios (Fig. 2f); the particularly low ratios in P. palmata were mainly due to low amounts of the omega-6 fatty acids LNA and ARA compared with the brown algae.

Several minor fatty acids were identified. While these contributed with ≤ 1%, they could still be important for the comprehensive understanding of the lipid metabolism in macroalgae. Several of these fatty acids are also understudied with regard to biological function and health implications. Their presence in these macroalgae could be of future interest. For example the biological functions of the odd chain fatty acids C15:0 and C17:0 is not yet fully understood, but amongst other things, they have been linked to reduced risk of coronary heart disease and type II diabetes, and are also believed to increase membrane fluidity in a similar way as PUFA, which can be relevant for diseases such as Alzheimer and multiple sclerosis (Jenkins et al. 2015; Pfeuffer and Jaudszus 2016). Another health concern is that dietary intake of trans-fat should stay below the recommended limit of 1% of calories (FAO 2010). The trans-fatty acids identified in A. esculenta, S. latissima and P. palmata were only found in low total amounts (≤ 0.2%, Online Resource 3). Intake of trans-fatty acids either from a single fraction, the whole alga or lipid extracts, will therefore be ≤ 0.2%. The vital fatty acid DHA was identified in both A. esculenta and S. latissima in low relative amounts (≤ 0.2 ± < 0.0% of each fraction, Online Resource 3). The highest total DHA content was found in A. esculenta (0.5 ± 0.1%).

In relation to risk factors for coronary heart disease, the AI, TI and HI indices were calculated. AI gives an indication of how the fat composition influences the formation of arterial fatty deposits, TI indicates how the fat composition impacts blood coagulation (as a predisposition for thrombosis, i.e. blood clots) and lastly, HI indicates the impact of the fat composition on blood cholesterol levels. Note that for AI and TI, low numbers (< 1) indicate protective effects, and higher numbers (> 1) promotive effects, while for HI, it is opposite. The calculated indices (Online resource 3) indicated that the NL fraction of S. latissima and the NL and PL fractions of A. esculenta were the most favourable when considering overall risk factors for coronary heart disease. The FFA fractions of P. palmata and S. latissima showed the opposite trend with higher values for AI and TI, and lower for HI, indicating overall promotive effects. An overall higher HI for the brown algae compared with the red alga agrees with previously published literature (Patarra et al. 2013).

When considering macroalgae as sources of dietary important fatty acids, several factors need to be taken into account, such as total lipid content, fatty acid profiles, bioavailability, biomass availability and likely dietary intake. Palmaria palmata had both the highest content of lipids (2.8 ± 01% of DW) and the highest content of EPA (the main omega-3 PUFA), and was thus the best potential source of this PUFA. However, Mæhre et al. (2014) calculated that the consumption of P. palmata had to be in the range of 130–160 g day−1 in order to meet the recommended daily intake of 250 mg EPAFootnote 1 (FAO 2010). As direct diet additions, macroalgae can contribute towards the intake of EPA, but not be the only source of this dietary important fatty acid. Lipid extracts are the most promising way of utilizing macroalgae as sources of PUFA. The co-utilization of the lipid fraction and e.g. the phycocolloid fraction (alginate) of macroalgae should also be of commercial interest. In a similar vein, Schiener et al. (2016) demonstrated that by-products from biofuel production from S. latissima, A. esculenta and Ulva lactuca had increased lipid content after saccharification and could be successfully used as feed for juvenile bivalve and sea urchins. Microalgae are also known to produce EPA as well as DHA, and a lipid content above 50% of DW has been reported, e.g. Fistulifera solaris cultivated for EPA production (Tanaka et al. 2017). The cultivation of microalgae is a promising field, but challenges due to cultivation cost and use of limited and/or expensive resources need to be solved (Lopes da Silva et al. 2019). When cultivating macroalgae, the seedlings grown in the lab are also in need of some resources, while if wild macroalgae is used, other concerns, such as sustainable harvesting strategies, impact on associated life forms and natural variability, are more relevant.

Conclusions

Our research shows that separating the lipid extracts into fractions will give access to very different fatty acid profiles. Utilizing one or more fractions of an alga can be helpful towards reaching a particular fatty acid content or a desired mix. Additionally, the fractions can give information about the fatty acid’s bioavailability, e.g. if EPA esterified to polar lipids for transport across the blood-brain barrier is wanted, then the PL fraction of P. palmata can be utilized. While our study showed that these macroalgae cannot be the only source of omega-3 PUFA in the diet, they can contribute to a higher intake of these fatty acids. The nutritional indices showed that fatty acid distribution in A. esculenta can have protective effects towards risk factors for coronary heart disease, especially the NL and PL fractions. The fatty acid profile of A. esculenta has received very little interest in the scientific community, especially compared with algae such as P. palmata. Our results indicate that A. esculenta could be a valuable diet addition. The omega-6/omega-3 ratios were low (≤ 1.05) in all the fractions of the three species, implying that introduction of these algal species in the diet can have a positive effect on lowering the omega-6/omega-3 ratio. For all three algae, the highest content of EPA and the other omega-3 fatty acids was found in the NL fractions, followed by the PL and then the FFA fractions, giving indications of their bioavailability. Unsurprisingly, based on previous literature, the best source of EPA was P. palmata. The NL and PL fractions of P. palmata seem overall promising from a health perspective due to high EPA content (10.1 ± 0.5 and 6.6 ± 0.1%, respectively) and very low omega-6/omega-3 ratios (< 0.1). However, the same two fractions also had high SFA content (19.8 ± 2.0 and 24.0 ± 0.9%, respectively) and low (≤ 0.2%) LNA and ALA content. Comparison with published data illustrated that within-species variation, even with the same sampling location and season, can be larger than between-taxon differences. In order to elucidate the causes of such differences, and allow for easier comparison of results, algae characterizations should ideally be accompanied by larger datasets describing the environmental conditions during algae growth and at time of harvesting.

Notes

The recommended intake is 250 mg EPA + DHA; however, red algae are only sources of EPA.

References

Balboa EM, Gallego-Fábrega C, Moure A, Domínguez H (2016) Study of the seasonal variation on proximate composition of oven-dried Sargassum muticum biomass collected in Vigo Ria, Spain. J Appl Phycol 28:1943–1953

Banskota AH, Stefanova R, Sperker S, Lall SP, Craigie JS, Hafting JT, Critchley AT (2014) Polar lipids from the marine macroalga Palmaria palmata inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide production in RAW264.7 macrophage cells. Phytochem 101:101–108

Barbosa M, Fernandes F, Pereira DM, Azevedo IC, Sousa-Pinto I, Andrade PB, Valentão P (2017) Fatty acid patterns of the kelps Saccharina latissima, Saccorhiza polyschides and Laminaria ochroleuca: Influence of changing environmental conditions. Arab J Chem 13:45–85

Biancarosa I, Belghit I, Bruckner CG, Liland NS, Waagbø R, Amlund H, Heesch S, Lock E-J (2018) Chemical characterization of 21 species of marine macroalgae common in Norwegian waters: benefits of and limitations to their potential use in food and feed. J Sci Food Agric 98:2035–2042

Burri L, Hoem N, Banni S, Berge K (2012) Marine omega-3 phospholipids: metabolism and biological activities. Int J Mol Sci 13:15401–15419

Cholewski M, Tomczykowa M, Tomczyk M (2018) A comprehensive review of chemistry, sources and bioavailability of omega-3 fatty acids. Nutrients 10:1662

da Costa E, Domingues P, Melo T, Coelho E, Pereira R, Calado R, Abreu MH, Domingues MR (2019) Lipidomic signatures reveal seasonal shifts on the relative abundance of high-valued lipids from the brown algae Fucus vesiculosus. Mar Dugs 17:335

Dawczynski C, Schubert R, Jahreis G (2007) Amino acids, fatty acids, and dietary fibre in edible seaweed products. Food Chem 103:891–899

Denis C, Morançais M, Li M, Deniaud E, Gaudin P, Wielgosz-Collin G, Barnathan G, Jaouen P, Fleurence J (2010) Study of the chemical composition of edible red macroalgae Grateloupia turuturu from Brittany (France). Food Chem 119:913–917

Devle H, Rukke E-O, Naess-Andresen CF, Ekeberg D (2009) A GC-magnetic sector MS method for identification and quantification of fatty acids in ewe milk by different acquisition modes. J Sep Sci 32:3738–3745

Devle H, Ulleberg EK, Naess-Andresen CF, Rukke E-O, Vegarud G, Ekeberg D (2014) Reciprocal interacting effects of proteins and lipids during ex vivo digestion of bovine milk. Int Dairy J 36:6–13

FAO (2010) Food and Nutrition Paper 91: Fats and fatty acids in human nutrition - report of an expert consultation

Fariman GA, Shastan SJ, Zahedi MM (2016) Seasonal variation of total lipid, fatty acids, fucoxanthin content, and antioxidant properties of two tropical brown algae (Nizamuddinia zanardinii and Cystoseira indica) from Iran. J Appl Phycol 28:1323–1331

Fernandes F, Barbosa M, Pereira DM, Sousa-Pinto I, Valentão P, Azevedo IC, Andrade PB (2018) Chemical profiling of edible seaweed (Ochrophyta) extracts and assessment of their in vitro effects on cell-free enzyme systems and on the viability of glutamate-injured SH-SY5Y cells. Food Chem Toxicol 116:196–206

Fernández M, Ordóñez JA, Cambero I, Santos C, Pin C, de la Hoz L (2007) Fatty acid compositions of selected varieties of Spanish dry ham related to their nutritional implications. Food Chem 101:107–112

Fleurence J, Gutbier G, Mabeau S, Leray C (1994) Fatty acids from 11 marine macroalgae of the French Brittany coast. J Appl Phycol 6:527–532

Floreto EAT, Hirata H, Ando S, Yamasaki S (1993) Fatty acid composition of Ulva pertusa Kjellman (Chlorophyta) and Gracilaria incurvata Okamura (Rhodophyta) in Japanese coastal waters. Bot Mar 36:217–222

Folch J, Lees M, Stanley GHS (1957) A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 226:497–509

Foseid L, Devle H, Stenstrøm Y, Naess-Andresen CF, Ekeberg D (2017) Fatty acid profiles of stipe and blade from the Norwegian brown macroalgae Laminaria hyperborea with special reference to acyl glycerides, polar lipids, and free fatty acids. J Lipids 2017:1–9

Galloway AWE, Britton-Simmons KH, Duggins DO, Gabrielson PW, Brett MT (2012) Fatty acid signatures differentiate marine macrophytes at ordinal and family ranks. J Phycol 48:956–965

Ghadiryanfar M, Rosentrater KA, Keyhani A, Omid M (2016) A review of macroalgae production, with potential applications in biofuels and bioenergy. Renew Sust Energ Rev 54:473–481

Gosch BJ, Paul NA, de Nys R, Magnusson M (2015) Spatial, seasonal, and within-plant variation in total fatty acid content and composition in the brown seaweeds Dictyota bartayresii and Dictyopteris australis (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae). J Appl Phycol 27:1607–1622

Graeve M, Kattner G, Wiencke C, Karsten U (2002) Fatty acid composition of Arctic and Antarctic macroalgae: indicator of phylogenetic and trophic relationships. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 231:67–74

Handå A, Forbord S, Wang X, Broch OJ, Dahle SW, Størseth TR, Reitan KI, Olsen Y, Skjermo J (2013) Seasonal- and depth-dependent growth of cultivated kelp (Saccharina latissima) in close proximity to salmon (Salmo salar) aquaculture in Norway. Aquaculture 414–415:191–201

Harwood JL (1998) Membrane lipids in algae. In: Siegenthaler P-A, Murata N (eds) Lipids in photosynthesis structure, Function and Genetics. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 53–64

Hölzl G, Dörmann P (2007) Structure and function of glycoglycerolipids in plants and bacteria. Prog Lipid Res 46:225–243

Jenkins B, West J, Koulman A (2015) A Review of odd-chain fatty acid metabolism and the role of pentadecanoic acid (C15:0) and heptadecanoic acid (C17:0) in health and disease. Molecules 20:2425–2444

Khairy HM, El-Shafay SM (2013) Seasonal variations in the biochemical composition of some common seaweed species from the coast of Abu Qir Bay, Alexandria, Egypt. Oceanologia 55:435–452

Koch K, Thiel M, Hagen W, Graeve M, Gómez I, Jofre D, Hofmann LC, Tala F, Bischof K (2016) Short- and long-term acclimation patterns of the giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae) along a depth gradient. J Phycol 52:260–273

Lopes da Silva T, Moniz P, Silva C, Reis A (2019) The dark side of microalgae biotechnology: a heterotrophic biorefinery platform directed to ω-3 rich lipid production. Microorganisms 7:670

Lopes D, Melo T, Meneses J, Abreu MH, Pereira R, Domingues P, Lillebø AI, Calado R, Domingues MR (2019) A new look for the red macroalga Palmaria palmata: a seafood with polar lipids rich in EPA and with antioxidant properties. Mar Drugs 17:533

Mæhre HK, Malde MK, Eilertsen K-E, Elvevoll EO (2014) Characterization of protein, lipid and mineral contents in common Norwegian seaweeds and evaluation of their potential as food and feed. J Sci Food Agric 94:3281–3290

Marinho G, Holdt S, Jacobsen C, Angelidaki I (2015) Lipids and composition of fatty acids of Saccharina latissima cultivated year-round in integrated multi-trophic aquaculture. Mar Drugs 13:4357–4374

Mishra VK, Temelli F, Ooraikul B, Shacklock PF, Craigie JS (1993) Lipids of the red alga, Palmaria palmata. Bot Mar 36:169–174

Mohy El-Din SM (2018) Temporal variation in chemical composition of Ulva lactuca and Corallina mediterranea. Int J Environ Sci Technol 16:5783–5796

Monteiro JP, Rey F, Melo T, Moreira ASP, Arbona J-F, Skjermo J, Forbord S, Funderud J, Raposo D, Kerrison PD, Perrineau M-M, Gachon C, Domingues P, Calado R, Domingues MR (2020) The unique lipidomic signatures of Saccharina latissima can be used to pinpoint their geographic origin. Biomolecules 10:107

Mouritsen OG, Williams L, Bjerregaard R, Duelund L (2012) Seaweeds for umami flavour in the New Nordic cuisine. Flavour 1:4

Mouritsen OG, Dawczynski C, Duelund L, Jahreis G, Vetter W, Schröder M (2013) On the human consumption of the red seaweed dulse (Palmaria palmata (L. ) Weber & Mohr). J Appl Phycol 25:1777–1791

Neto RT, Marçal C, Queirós AS, Abreu H, Silva AMS, Cardoso SM (2018) Screening of Ulva rigida, Gracilaria sp., Fucus vesiculosus and Saccharina latissima as functional ingredients. Int J Mol Sci 19:2987

Norwegian Centre for Climate Services (2018) Norwegian Centre for Climate Services. https://klimaservicesenter.no/observations/days/sea_surface_temperature/custom_period/SN76925,SN76928,SN76933/nb/2018-05-25T00:00:00+02:00;2018-06-02T00:00:00+02:00 Accessed 30 Apr 2020

Patarra RF, Leite J, Pereira R, Baptista J, Neto AI (2013) Fatty acid composition of selected macrophytes. Nat Prod Res 27:665–669

Pereira H, Barreira L, Figueiredo F, Custódio L, Vizetto-Duarte C, Polo C, Rešek E, Engelen A, Varela J (2012) Polyunsaturated fatty acids of marine macroalgae: potential for nutritional and pharmaceutical applications. Mar Drugs 10:1920–1935

Pfeuffer M, Jaudszus A (2016) Pentadecanoic and heptadecanoic acids: multifaceted odd-chain fatty acids. Adv Nutr 7:730–734

Pinkart HC, Devereux R, Chapman PJ (1998) Rapid separation of microbial lipids using solid phase extraction columns. J Microbiol Meth 34:9–15

Praiboon J, Palakas S, Noiraksa T, Miyashita K (2018) Seasonal variation in nutritional composition and anti-proliferative activity of brown seaweed, Sargassum oligocystum. J Appl Phycol 30:101–111

Rey F, Lopes D, Maciel E, Monteiro J, Skjermo J, Funderud J, Raposo D, Domingues P, Calado R, Domingues MR (2019) Polar lipid profile of Saccharina latissima, a functional food from the sea. Algal Res 39:101473

Robertson R, Guihéneuf F, Schmid M, Stengel D, Fitzgerald G, Ross P, Stanton C (2013) Algal-derived polyunsaturated fatty acids: implications for human health. In: Catalá A (ed) Polyunsaturated fatty acids: sources, antioxidant properties and health benefits. Nova Science Publishers, New York, p 45–99

Robertson RC, Guihéneuf F, Bahar B, Schmid M, Stengel DB, Fitzgerald GF, Ross RP, Stanton C (2015) The anti-inflammatory effect of algae-derived lipid extracts on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated human THP-1 macrophages. Mar Drugs 13:5402–5424

RStudio Team (2019) RStudio: integrated development for R. RStudio, Inc, Boston. http://www.rstudio.com/

Ruiz J, Antequera T, Andres AI, Petron MJ, Muriel E (2004) Improvement of a solid phase extraction method for analysis of lipid fractions in muscle foods. Anal Chim Acta 520:201–205

Schiener P, Atack T, Wareing RA, Kelly MS, Hughes AD (2016) The by-products from marine biofuels as a feed source for the aquaculture industry: a novel example of the biorefinery approach. Biomass Convers Biorefin 6:281–287

Schmid M, Stengel DB (2015) Intra-thallus differentiation of fatty acid and pigment profiles in some temperate Fucales and Laminariales. J Phycol 51:25–36

Schmid M, Guihéneuf F, Stengel DB (2014) Fatty acid contents and profiles of 16 macroalgae collected from the Irish Coast at two seasons. J Appl Phycol 26:451–463

Schmid M, Guihéneuf F, Stengel DB (2016) Evaluation of food grade solvents for lipid extraction and impact of storage temperature on fatty acid composition of edible seaweeds Laminaria digitata (Phaeophyceae) and Palmaria palmata (Rhodophyta). Food Chem 208:161–168

Schmid M, Guihéneuf F, Stengel DB (2017a) Ecological and commercial implications of temporal and spatial variability in the composition of pigments and fatty acids in five Irish macroalgae. Mar Biol 164:1–18

Schmid M, Guihéneuf F, Stengel DB (2017b) Plasticity and remodelling of lipids support acclimation potential in two species of low-intertidal macroalgae, Fucus serratus (Phaeophyceae) and Palmaria palmata (Rhodophyta). Algal Res 26:104–114

Serviere-Zaragoza E, Hurtado MA, Manzano-Sarabia M, Mazariegos-Villarreal A, Reza M, Arjona O, Palacios E (2015) Seasonal and interannual variation of fatty acids in macrophytes from the Pacific coast of Baja California Peninsula (Mexico). J Appl Phycol 27:1297–1306

Shaltout NAN, El-Din NGS (2015) Investigation of the fatty acid profile in some macroalgae in relation to the environmental conditions for biodiesel production. Am J Environ Sci 11:402–419

Simopoulos AP (2002) The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed Pharmacother 56:365–379

Stengel DB, Connan S, Popper ZA (2011) Algal chemodiversity and bioactivity: Sources of natural variability and implications for commercial application. Biotechnol Adv 29:483–501

Stévant P, Rebours C, Chapman A (2017) Seaweed aquaculture in Norway: recent industrial developments and future perspectives. Aquacult Int 25:1373–1390

Tanaka T, Yabuuchi T, Maeda Y, Nojima D, Matsumoto M, Yoshino T (2017) Production of eicosapentaenoic acid by high cell density cultivation of the marine oleaginous diatom Fistulifera solaris. Bioresour Technol 245:567–572

Ulbricht TLV, Southgate DAT (1991) Coronary heart disease: seven dietary factors. The Lancet 338:985–992

van Ginneken VJT, Helsper JPFG, de Visser W, van Keulen H, Brandenburg WA (2011) Polyunsaturated fatty acids in various macroalgal species from North Atlantic and tropical seas. Lipids Health Dis 10:104

Venkatesalu V, Sundaramoorthy P, Anantharaj M, Chandrasekaran M, Senthilkumar AN (2012) Seasonal variation on fatty acid composition of some marine macro algae from Gulf of Mannar Marine Biosphere Reserve, Southeast cost of India. Indian J Geo-Mar Sci 41:442–450

Vilg JV, Nylund GM, Werner T, Qvirist L, Mayers JJ, Pavia H, Undeland I, Albers E (2015) Seasonal and spatial variation in biochemical composition of Saccharina latissima during a potential harvesting season for Western Sweden. Bot Mar 58:435–447

Walker CG, Jebb SA, Calder PC (2013) Stearidonic acid as a supplemental source of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids to enhance status for improved human health. Nutr 29:363–369

Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, Chang W, McGowan LD, François R, Grolemund G, Hayes A, Henry L, Hester J, Kuhn M, Pedersen TL, Miller E, Bache SM, Müller K, Ooms J, Robinson D, Seidel DP, Spinu V, Takahashi K, Vaughan D, Wilke C, Woo K, Yutani H (2019) Welcome to the tidyverse. J Open Source Softw 4:1686

Xu X-Q, Tran VH, Kraft G, Beardall J (1998) Fatty acids of six Codium species from southeast Australia. Phytochem 48:1335–1339

Zárate R, el Jaber-Vazdekis N, Tejera N, Pérez JA, Rodríguez C (2017) Significance of long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in human health. Clin Transl Med 6:25

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

Funding

This work was funded by the Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Foseid, L., Natvik, I., Devle, H. et al. Identification of fatty acids in fractionated lipid extracts from Palmaria palmata, Alaria esculenta and Saccharina latissima by off-line SPE GC-MS. J Appl Phycol 32, 4251–4262 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-020-02193-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-020-02193-2