Abstract

Each year a significant proportion of global food production is lost to pests and diseases, with concerted efforts by government and industry focussed on application of effective biosecurity policies which attempt to minimise their emergence and spread. In aquaculture the volume of seaweeds produced is second only to farmed fish and red algal carrageenophytes currently represent approximately 42% of global production of all seaweeds. Despite this importance, expansion of the seaweed sector is increasingly limited by the high prevalence of recalcitrant diseases and epiphytic pests with potential to emerge and with the demonstrated propensity to spread, particularly in the absence of effective national and international biosecurity policies. Developing biosecurity policy and legislation to manage biosecurity risk in seaweed aquaculture is urgently required to limit these impacts. To understand current international biosecurity frameworks and their efficacy, existing legislative frameworks were analysed quantitatively for the content of biosecurity measures, applicability to the seaweed industry, and inclusion of risks posed by diseases, pests and non-native species. Deficiencies in existing frameworks included the following: inconsistent terminology for inclusion of cultivated seaweeds, unclear designation of implementation responsibility, insufficient evidence-based information and limited alignment of biosecurity hazards and risks. Given the global importance of the cultivation of various seaweeds in alleviating poverty in low and middle income countries, it is crucial that the relatively low-unit value of the industry (i.e. as compared with other aquatic animal sectors) should not conflate with a perceived low risk of disease or pest transfer, nor the subsequent economic and environmental impact that disease transfer may impact on receiving nations (well beyond their seaweed operations). Developing a clear basis for development of robust international biosecurity policies related to the trade in seaweeds arising from the global aquaculture industry, by first addressing the gaps highlighted in this study, will be crucial in limiting impacts of pests and diseases on this valuable industry and on natural capital in locations where seaweeds are farmed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With a growing population, the world has been experiencing an era of rapid expansion in food production and, according to the World Resource Institute (WRI), must continue to increase this production to meet the demands (Hunter et al. 2017). Rapid expansion in any food production sector leads to a tipping point which can limit production. In crop production, this is often signified by outbreaks of infectious disease (Anderson et al. 2004) or pests (Oerke 2006). Each year, 20–40% of (terrestrial) global crop production is lost to disease and pests (Savary et al. 2012). As the human diet predominantly comprises terrestrial plants (80%) (FAO & IPPC 2017), the rise of disease and pest outbreaks in this sector is a significant concern regarding food security. The aquaculture sector is no exception, and many industries have become limited in their production by diseases and pests, which for aquatic animals equates to losses of at least 6 billion US$ per annum (Stentiford et al. 2017). For example, the cost of control measures for sea lice pests alone, in salmon production, can equate to farm revenue losses of 9% (Abolofia and Wilen 2017) and losses in shrimp production to diseases can exceed 40% of global capacity (Stentiford et al. 2017).

In comparison with the relatively high trading value of aquatic animals and their products, seaweeds are some of the lowest unit-value aquaculture commodities. Despite this, a variety of seaweeds have been cultivated intensively over the past 50 years and have risen to become the second largest aquaculture product in terms of volume, second only to total fish production (FAO 2018). Of all the seaweed species produced globally, those contributing the highest volume in 2016 were red algal species (FAO 2018). A combination of two red algal genera, i.e. Eucheuma sp. and Kappaphycus spp.—also known as eucheumatoids and carrageenophytes—make up approximately 42% of global seaweed production (FAO 2018). This group of algae is typically produced and processed for the high-value compound carrageenan, which is used in food, drink and pharmaceutical industries globally. Cultivation of these carrageenophytes originated in the Philippines, but global production requirements are now largely supplied by four countries: the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia and the United Republic of Tanzania. Together, these countries produced 44.5% of the worlds’ carrageenophytes (FAO 2018). As with most intensively cultivated systems, the annual growth rate of the global seaweed aquaculture sector is now slowing. A number of factors have contributed to this decline in growth (Cottier-Cook et al. 2016), including climate change (Kim et al. 2017), a reduction in genetic diversity of cultivated crops (Loureiro et al. 2015), and low and fluctuating market prices (Valderrama et al. 2015). It is often the case that the combined outcome of these factors is an increased susceptibility to crop infestation with pests and infections which cause disease, as observed in other major aquacultural industries (Bondad-Reantaso et al. 2005; Stentiford et al. 2017).

Coordinating the management of biosecurity in traded commodities is integral to limiting the challenges created by disease and pest outbreaks in globally traded crops. In the three top producing countries for red algae, i.e. Indonesia, the Philippines and the United Republic of Tanzania, the current major limitations to national production are the impacts of diseases and outbreaks of epiphytic algal pests (Vairappan et al. 2008). The scale of these biosecurity impacts, however, has not yet been quantified, and information currently relies on a small number of reports and preliminary studies (Critchley et al. 2004; Hurtado et al. 2006; Vairappan et al. 2008). In order to prevent and limit further spread of diseases and pests, biosecurity measures must be enacted by organisations at different scales within the production system (from farm to national government) (FAO 2007; Bondad-Reantaso et al. 2018). Since the rapid growth of production of various seaweeds, particularly in developing countries, has been facilitated by the globalization of trade, a greater need for effective biosecurity measures and exercise of the precautionary principle has been recommended for sustaining the global seaweed industry (Cottier-Cook et al. 2016).

The aim of this study is to present a comparative analysis of biosecurity policies relevant to the carrageenan industry at international, regional and national scales, for application in major carrageenan-producing countries. The scope of the policies has been limited to those that include the cultivation of carrageenophytes and those which cover all aspects of biosecurity management. Using a defined list of biosecurity components, systematic identification of similarities, differences and deficiencies in biosecurity policies for the carrageenophyte industry (compared with other aquaculture sectors), we highlight numerous points of failure within existing policy frameworks aimed to limit the impact of diseases and pest outbreaks. This is the first comprehensive analysis of international and regional management of biosecurity, as applied to the seaweed aquaculture industry, and provides the first step towards the design of improved international policies to support sustainable production.

Materials and methods

Selection of biosecurity frameworks

The term ‘biosecurity’ can have variable interpretations; however, in this review, we refer to the interpretation of the FAO as described in the ‘Biosecurity Toolkit’ (2007), where biosecurity encompasses food safety, zoonosis, the introduction of diseases and pests, the introduction and release of Living Modified Organisms (LMO’s are a result of biotechnology), and the introduction and management of invasive alien species. Policy ‘frameworks’ were defined as any documented agreements, declarations, guidelines and policy plans, which related to international biosecurity measures. The selection of specific frameworks was dependant on their applicability to biosecurity management and/or guidance relative to seaweed production. For international agreements, selection was based upon having priority over policy at all scales, and regional frameworks were selected where they played a role in aquaculture production across multiple nations, and specifically included one, or more, of the top four carrageenan producing countries. All selected frameworks are published and publicly available documents or texts of agreements.

Analysis of biosecurity themes

Once frameworks were identified, comparative analysis was carried out using categorised themes adapted from those developed by Dahlstrom et al. (2011). Themes and their categories are described in Online Resource 1 and include the force of the framework, the level of seaweed specificity in the text, the biosecurity approach, the type of information used to produce or implement the framework and the use of precaution in its text.

Analysis of risks included in biosecurity frameworks

A list of risks (consequences of a hazardous disease or pest) was compiled by modifying those used in Dahlstrom et al. (2011), including specific risks in seaweed cultivation systems, and removing those that were not relevant to seaweed cultivation. These risks were then grouped into five main categories: ecological, environmental, economic, social and cultural, and risk posed to farm staff.

Results

Identification of international and regional biosecurity frameworks

Frameworks were identified that were relevant to the top four carrageenan-producing countries. These included the following: World Trade Organization (WTO) and its standard setting bodies, i.e. World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) for animal biosecurity, the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) for plant biosecurity and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Regional frameworks identified were the Network for Aquaculture Centres in Asia (NACA), the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the African Union’s Inter-African Bureaux for Animal Resources (AU-IBAR). The specific documents used in analysis are listed in Table 1.

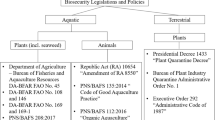

Given the international and regional scales of the ‘frameworks’ and the range of components that can be included under the term ‘biosecurity’, a complex relationship was found to exist between each of them (Fig. 1). International trade agreements set by the WTO were found to form the basis for implementing biosecurity measures on this scale—the specific framework for this is the Sanitary and Phytosanitary Agreement (SPS agreement) (WTO 2018). The WTO has two standard-setting bodies responsible for providing the outline for complying with these standards: the OIE, who set the animal health standard, which includes aquatic animals (OIE 2017); and the IPPC, who set standards for plant health, which includes ‘aquatic plants for planting’. In 2014 the IPPC formally included ‘aquatic plants’ (which includes seaweeds) in their International Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (ISPMs) (IPPC 2017a). In addition, the ISPMs include a pest risk analysis tool which is conceivably the most specific framework which can be applied to the seaweed trade on an international scale. The ISPMs are complemented by two other frameworks, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) protocols (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity 2000, 2011) and the Codex Alimentarius Commission for food safety (CAC) (WHO 2016). The CBD and CAC protocols have a different biosecurity focus, specifically aiming to manage the genetic sharing of resources and food safety, respectively. Together, the ISPMs, the CBD protocols and the CAC food safety standards complete the international biosecurity landscape for potential application to seaweed aquaculture.

Although international frameworks require ratified nations to implement their biosecurity measures under national legislation, regional frameworks can offer a key link between international frameworks and national implementation, by providing support in vertically integrating the measures with more accurate knowledge of the national context within the regional group. The regional organizations, which are assisting in such vertical integration, include the following: NACA, ASEAN and APEC for the south-east Asia region, and AU-IBAR in Africa; each of which provides policy strategies and guidelines for implementation of the international frameworks on a more specific regional scale (NACA 2000; APEC 2012a, b, 2014a, b; AUC & NEPAD 2014; AU-IBAR 2015, 2016; ASEAN 2015a, b).

Thematic analysis of biosecurity frameworks

The majority of international and regional biosecurity frameworks (57%) do not require compliance, and all others (43%) require compliance when ratified by a nation state (Fig. 2). In the case of the regional framework set out by NACA (Technical Guidelines for Health Management for the Responsible Movement of Live Aquatic Animals), there is no form of compliance required, although the text makes reference to complying with SPMs of the WTO which are ratified.

In terms of using seaweed specific terminology in the frameworks assessed, seaweeds can be referred to as ‘Aquatic plants’ or ‘Algae’ or ‘Macroalgae’ or ‘Marine plants’ or ‘Seaweeds’. Only the IPCC framework, however, specifically mentions ‘aquatic plants’. Following this, the most relevant inclusion of seaweeds was made under the general term ‘aquaculture’ in 29% of the frameworks assessed, with the majority of biosecurity measures being tailored to aquatic animal production and trade. Although the selected frameworks were chosen as they were relevant to seaweed aquaculture, many only included seaweed under the general umbrella term of ‘food security’, and predominantly focused on maintaining adequate food production for human consumption rather than being directed at disease and pest management per se.

A variety of biosecurity approaches were identified within the text of the frameworks including response and recovery planning, detection (including monitoring), prevention, incentives and penalties. A total of 15 different approaches were identified in the frameworks, with a number including more than one approach. Other frameworks, however, did not outline a specific approach, but instead included terms relating to the general management of biosecurity risks. For example, in the regional APEC declaration, both detection and response and recovery planning measures were mentioned. The most comprehensive frameworks were the ISPMs of IPPC, which included detection, prevention, response and recovery planning, and the aquatic animal health code of the OIE, which included detection and protection. All other frameworks were based on a single approach, which was predominantly (53%) based on prevention of the disease, pest or non-native. Those frameworks that did not include a categorised approach were the regional framework in Asia, the AIFS ‘SPA-FS’, and the regional framework in Africa, the AU-IBAR ‘PRFS’.

The main source of information for 37% of the frameworks assessed was through industry stakeholders. This information was typically gathered by holding workshops where the texts or agreements were written and agreed upon. Other major identifiable information sources were scientific literature and expert opinion, used in 32% and 21% of the frameworks, respectively. In the case of expert opinion, a smaller panel of experts was typically used to develop a framework. In IPPC frameworks, although all the ISPMs used scientific literature as the main source of information, the text also specified that if there was no scientific information available to determine the risk, then the pest risk analysis tool should be used. This is an internationally agreed process, designed by the IPPC as part of the phytosanitary measures, to be used to assess risk from a disease or pest against proportional control measures (IPPC 2016).

Finally, the use of precaution in biosecurity measures was only explicitly mentioned in 23% of the frameworks: the OIE, the Cartagena protocol and AU-IBAR PFRS. The frameworks which included precautionary measures, but did not use the term explicitly, were the WTO SPS agreement, the IPPC and the AU-IBAR 10-year aquaculture plan. In 54% of the frameworks the use of precaution was not mentioned.

Biosecurity risks

Each framework was assessed for its inclusion of biosecurity risks (consequences of a hazardous disease or pest) (detailed in Online Resource 2) and is presented in Fig. 3 where the proportion of their inclusion across the different frameworks is represented. The shaded area in Fig. 3 shows the disproportionate and low coverage of multiple risks in the frameworks (particularly in Fig. 3b). In terms of ecological risk in the biosecurity frameworks, the most commonly used were those that led to the most direct impact: pests and/or pathogens themselves, their vectors, decreases in native species abundance and the introduction of new hosts. These risks were all included in more than 60% of the frameworks. More limited in inclusion were the less direct ecological risks, which were included in approximately 20% of frameworks. These included the following: habitat loss or change, decrease in threatened or endangered species and toxicity herbivory or competition from introduced species, pests and/or diseases.

In the environmental risk category, only 20% of the frameworks included any mention of these risks, with only hydrological and food web changes, and the impact of control measures on the wider environment incorporated in the text. Those that were included in less than 20% of frameworks included the risks of nutrient regime changes, physical disturbance or the effects of climate change.

Of the 18 risks in the socio-economic category, production of crop, trade losses, control and management costs, trade losses and trade restrictions were all included in more than 40% of the frameworks. Impacts on infrastructure, adverse reactions from buyers, impacts on capture fisheries, costs of replanting, impacts on ecosystem services and impacts on food safety were only included in 20–40% of the frameworks. Finally, the socio-economic risks that were included in less than 20% of frameworks were impacts on tourism, shipping, other aquaculture sectors and the health care costs for impacted farm staff.

An assessment of the overall inclusion of all risks in each framework is presented in Fig. 4. This figure shows that the IPPC and OIE frameworks have the highest proportion of included risks, including approximately 80% and 60% of risks respectively in comparison with the remaining frameworks which include < 40% of risks. The second most comprehensive framework is the NACA technical guidelines for aquatic animal health, which included 36% of the risks. The WTO SPS agreement, the Nagoya protocol, the Cartagena protocol, the ASEAN GAqP, AU-IBAR PFRS and the AU-IBAR 10-year aquaculture plan all included less than 20% of the risks.

Discussion

The global trade in various seaweeds is being significantly hampered by disease and pest outbreaks. Further, there are no dedicated biosecurity frameworks which specifically consider the potential for trans-boundary movement of seaweed diseases and pests during the trading of seaweeds and their products. This analysis has revealed the similarities, gaps and deficiencies of international and regional biosecurity frameworks related to the top carrageenan-producing countries. Four main challenges to the current biosecurity system have been identified for the carrageenophyte industry: inconsistent terminology for the inclusion of cultivated seaweeds, limited guidance for designating responsibility for the implementation of framework measures, insufficient evidence to develop disease- and pest-specific policies, and limited alignment of biosecurity risks between policies.

Inconsistent terminology for the inclusion of cultivated seaweeds

Of all the identified international biosecurity frameworks, only the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) makes reference to ‘aquatic plants’, defining them as ‘Any plant that grows partly or wholly in water, and can be rooted in sediment or free floating on the water surface’ indicating that seaweeds are included under this term (IPPC 2012). Prior to 2012, it was unclear whether seaweeds would fall under the trading sanitary standards of the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), as the aquatic animal health standard holders, or the IPPC, the plant standard holders. The allocation of seaweeds (macroalgae) to either the plant or animal group is problematic given that algae can be allocated to different kingdoms: Plantae (red and green algae) and Chromista (brown algae), and this is reflected in the commercial naming of seaweed crops (Bolton 2019). As the phylogeny of algae continues to be shaped by advances in molecular biology (Pereira and Neto 2014), the allocation of ‘seaweeds’ to legislation by different standard setting bodies is also uncertain. The carrageenophytes are currently allocated to the kingdom Plantae (Moreira et al. 2000), but genetic interpretation is ongoing. The IPPC scoping study, however (IPPC 2017a), recommended that cultivated ‘aquatic plants’ should be included in their sanitary standards to ‘ensure that aquatic plants, as potential pests and pathways, become subject to, or included in, pest risk analysis whenever relevant, in particular in cases where aquatic plants are intentionally imported for intended uses as plants for planting, e.g. in aquaculture or other aquatic habitats.’ (IPPC 2017a). Current regulation of international biosecurity through the SPS agreement though is clearly divided between two systems related to plants (IPPC) or animals (OIE). The definition of ‘aquatic plants’ implies that the regulation of seaweeds is now under the International Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (ISPMs) of the IPPC, but definitive inclusion of all red, brown and green seaweeds (macroalgae) remains unclear. In addition, the risks and uses of important seaweed species are described in the most recent IPPC report on aquatic plants. This report includes species of economic importance, and although it includes 16 seaweed species, no carrageenophyte species are listed, despite equating to 45% of the global production of seaweed. We recommend here that the IPPC makes explicit reference to seaweeds, of specific taxonomy, in future iterations of their regulations. The inclusion of red, green and brown seaweeds into the terminology of IPPC regulations initiates the means by which the most highly traded taxa (e.g. Eucheuma sp. and Kappaphycus spp.) are included in biosecurity legislation focussed on trade of the most common commodities.

Another option to improve the inclusion and consistency of the terminology of seaweeds in policies would be through a concerted effort at international and regional scales to harmonise the current language of seaweed cultivation (e.g. ‘aquatic plants’ vs. ‘algae’ vs. ‘seaweeds’ vs. ‘macroalgae’), a problem which is also observed in the use of terminology for general biosecurity in the aquatic environment (Dahlstrom et al. 2011), invasive species in aquaculture (Hill 2008) and even in specific biosecurity measures of the shrimp industry (Alday-sanz et al. 2018). Another option is for the governing organisations of international biosecurity policies to either update or create new texts which include seaweed specific terminology and to set the standard for its inclusion in future regional and national frameworks. The misalignment of biosecurity language is also reflected in the separation between definitions in the animal and plant standards of OIE and IPPC, where the OIE defines ‘disease’ as all pests or pathogens, and the IPPC defines all ‘pests’ as any pathogenic agent. The ongoing issue of inter-changeable language within the subject of biosecurity (Dahlstrom et al. 2011) will be a challenge to the integration of both seaweed cultivation and biosecurity in international policy.

Limited guidance for designating responsibility for the implementation of framework measures

Without recognition by international organisations who influence the management of the aquaculture industry, the lack of designation of seaweeds to biosecurity frameworks remains unnoticed. Almost all frameworks included seaweed cultivation under the umbrella of general aquaculture, which is of course, a diverse industry. However, frameworks are often tailored to aquatic animal health biosecurity measures which are already internationally regulated through the OIE’s long-standing focus on aquatic animal production sectors (fish, molluscs, crustaceans, amphibians) (OIE 2017). The low level of recognition of the seaweed industry in international aquaculture policy is reflected in the level of global reporting by FAO. The latest ‘State of the World’s Fisheries and Aquaculture’ ‘SOFIA’ report (FAO 2018) provided a summary of the tonnage of aquaculture and capture fisheries production from 1950 to 2015, and yet the tonnage representing global aquaculture excluded any seaweeds or aquatic plants, even though the sector is second only to fin-fish in terms of volume. Although political interest in aquaculture is largely economically driven, as opposed to volumes, more should be done to acknowledge that poor biosecurity in the seaweed industry can impact the trading ability of a country. If the international policy profile of the seaweed industry remains low, then assigning responsibility of the sanitary and phytosanitary to the IPPC, their regional organisations, down to the national authority who should be implementing the measures could continue to appear as a low priority.

Only half of the frameworks identified were binding, mostly through ratification of the text by a member nation, and there was no framework which included any penalties in their approach to implementation. Most of the responsibility for implementation is passed down to national authorities. However, given the lack of clarity on the inclusion of seaweeds in almost all of the frameworks, it is unclear which national authority is responsible for the implementation of the biosecurity measures. As with other sectors in aquaculture, implementation of biosecurity measures is regulated by the national competent authorities which are often those government departments with responsibility for fisheries and/or aquaculture (e.g. Bureau of Fisheries and Aquaculture Resources—BFAR in the Philippines (Jonalyn P. Mateo (pers. comm.) 26/11/2019) and Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries—MMAF in Indonesia (Cicilia S. B. Kambey (pers. comm.) 26/11/2019). Such departments typically regulate the international movement of live aquatic animals using the import risk analysis (IRA) tool of the OIE. Given the widespread occurrence of pests and diseases observed internationally in seaweed aquaculture (Watkiss et al. 2012; Hurtado et al. 2017; Quiaoit et al. 2018), and that seaweed crops have been transplanted internationally to establish new cultivation sites (Loureiro et al. 2015; Hurtado et al. 2017) under the IPPC framework, Pest Risk Assessments (PRA) for the carrageenophyte industry should be initiated by the National Plant Protection Organisation (NPPO) in each producing country (IPPC 2017b), but to date have not been reported (IPPC 2019). Cultivation of seaweeds in most countries is regulated by aquaculture or fishery authorities, and the NPPO is often concerned solely with terrestrial agriculture. A conflict therefore arises, over which authority has the capacity to regulate and has the responsibility to implement the IPPC PRA measures under the framework. The challenge for many seaweed producing countries will be to connect these departments, to allow for active communication and sharing of expertise. Similarly, it will become increasingly important for those nations wishing to trade seaweed products with one another that such equivalent measures are taken. Even after strengthening these lines of communication, a national competent authority can implement SPS measures for ‘plants for planting’ using various approaches (Eschen et al. 2015), and could be designed to be suitable for application in the aquatic environment.

Regional guidelines of the ASEAN region, where selected seaweeds are significantly important commodities, only make reference to the international guidelines of OIE for specific biosecurity measures (ASEAN 2015a, b), predominantly focussing on aquatic animal health or terrestrial crops (i.e. rice and maize). As a result, the recommendations do not align with cultivated seaweeds as ‘plants’ cultivated in an open aquatic environment, and this industry is therefore excluded from national and (as a consequence of a lacking point of reference) international frameworks. The ASEAN Asian Integrated Food Security (AIFS) framework is focused on regional food security, which is exclusive to subsistence crops: rice, maize, soybean, sugar and cassava; therefore, recognition of the seaweed industry and its value to the region is limited. Although ASEAN has published a strategic action plan for cooperation on fisheries (which includes ‘aquaculture’ products), it is unclear whether varieties of seaweeds will be included, if at all, given that any mention of biosecurity is directed to aquatic animal health under the OIE guidelines (ASEAN 2016).

The majority of international and regional scale biosecurity frameworks (79%) for invasive species in the marine environment have been identified as legally binding by Dahlstrom et al. (2011). A lower proportion of frameworks (42%) were found to be legally binding by ratification in this study. Top carrageenophyte-producing countries (which are also low-income or lower-middle income countries as listed by the Development Assistance Committee) can be limited by capacity, resources and economic incentives, therefore, finding it challenging to implement and enforce national policies. For other industries, successful implementation of national policies has required both alignment of policies with the specific biosecurity challenges of the industry and the economic incentive to invest resources in regulation (Chaminade and Padilla Pérez 2014). Science and technology policies in developing countries often imitate objectives or strategies of international frameworks, rather than addressing the specific national challenges (Chaminade and Padilla Pérez 2014). As there is only one international policy which includes seaweed cultivation under the term ‘aquatic plants’, this will then limit the ability for biosecurity measures to be implemented through national legislation. In addition, as incorporation of international frameworks into national legislation is often a complex and expensive process, requiring a certain level of national capacity (Dahlstrom et al. 2011), many seaweed-producing nations will need financial and expert assistance in developing appropriate policies. One seaweed specific framework, although not international policy is a certification initiative by the Aquaculture Stewardship and Marine Stewardship Council, includes elements of biosecurity management. However, certification schemes are often industry focussed, and there remains uncertainty over whether there is any great demand for certified seaweed products by the industry, which is generally considered more sustainable than other sectors of the aquaculture (Porse and Rudolph 2017).

Without an international framework, which specifically includes seaweed cultivation, then the uptake of biosecurity through the trading principle of ‘equivalence’, whereby the receiving nation of a particular seaweed crop for planting will not want to risk trading with a nation which could risk their own national biosecurity, means that, at present, biosecurity is not financially advantageous. This is reflected by the high inclusion rate of economic risks in biosecurity frameworks, as compared with the far fewer references made to ecosystem impacts. Of the top producing countries, carrageenophytes are the third largest exported commodity from Tanzania, behind coffee and cloves (Watkiss et al. 2012), and the largest aquaculture product in the Philippines by volume (Jonalyn P. Mateo (pers. comm.) 26/11/2019). However, when set in the international context, seaweeds comprise one of the lowest unit value sectors of global aquaculture (FAO 2018). Although immediate economic incentives on the global scale, compared with other industries, may be causing poor engagement in the development of policies with the seaweed industry, nations abiding by animal health regulations (e.g. those of the OIE) control for disease in traded animals to protect the wild stocks of those countries from potential incoming pests. In this context, the lack of biosecurity in low-value species being internationally traded to nations, which otherwise control aquatic animal diseases, may pose significant threat to native taxa. Yet, this concept does not appear to be applied to the carrageenophyte industry. Biosecurity approaches in the frameworks also tended to focus on improving response and recovery after the spread of pests, diseases and non-natives, and improving the economic recovery of the whole sector; therefore, management measures are typically directed at traders and buyers and not the farmers, who are losing their household income (Hayashi et al. 2010; Watkiss et al. 2012).

Insufficient evidence to develop specific policies for disease and pests

Only one-third of frameworks used scientific evidence to form the basis of their measures or guidance, which reflects the paucity of literature regarding biosecurity risks in the seaweed industry (Cottier-Cook et al. 2016). Most information for policy development (i.e. reporting disease outbreaks, documenting diseased crops or documenting losses due to diseases or pests) are gathered from stakeholder participation. However, there is a distinct lack of information available on which to assess the main biosecurity risks within the industry. As the information used to design biosecurity management measures in many cases is not specifically based on evidence from the seaweed industry, detection, monitoring and prevention measures are limited in their effectiveness. To develop an effective biosecurity approach on the international scale, there is a requirement for a certain amount and type of knowledge (Bondad-Reantaso et al. 2005). For aquatic animals, this knowledge base is centred on a list of pathogens that are known to cause significant diseases in farmed stocks, have the potential to be transferred by trade in animals and products and do not exist in at least some parts of the range of those traded hosts. The OIE Aquatic Manual and Code series, updated each year, include chapters on specific pathogens, the list of susceptible host species to those agents and ways in which they can be accurately diagnosed, reported and potentially controlled (OIE 2017). Using basic categories, this information would indicate what is the affected crop (better definitions of cultivated species or strains), what the exact disease or pests of this crop are, and where the crop is being grown or traded. In many cases the genetic identity of carrageenophyte crops remains unknown and diseases are yet to be categorised. Even when diseases are known and provided with a broad identity (e.g. ‘ice-ice’ disease), the actual causative agent often remains unknown. In addition, the spatial distribution of cultivated species may also remain unknown. One example of this is exemplified in a national survey of the seaweed industry in the Philippines, which revealed that there were multiple, inter-changeable local names for three species of carrageenophytes being grown across the same regions (Quiaoit et al. 2018). This is also reflected on an international scale in the FAO: ‘State of the World’s Fisheries and Aquaculture’ (SOFIA) report (FAO 2018), where production data in unspecified categories such as ‘Seaweeds nei’ and ‘Algae’ equated to approximately 1 million tonnes in 2016.

Limited alignment of biosecurity risks between policies

Through the analysis of themes in the frameworks, a range of different biosecurity approaches was identified and was interpreted differently, depending on the overall goals of the organisation implementing the framework. For example, the OIE tends to focus on the listing of specific diseases with associated management measures, whereas the IPPC mostly focuses on plants’ pests through the Pest Risk Analysis tool but has no counterpart disease risk analysis tool. This was further reflected in the analysis of included biosecurity risks, where in the case of the CBD protocols, diseases and pests were not specifically included, but the focus was on maintaining biodiversity and reducing the impacts of non-native species through cultivation of native species. Another example was the different meanings of recovery in the case of the response recovery and planning approach. In the IPPC this is aimed at recovery from the physical impact of pests on the environment or crop loss, and for APEC, this was economic recovery after crop loss. This makes vertical integration of approaches difficult to interpret, as all organisations may agree to response and recovery planning in their biosecurity framework but may interpret and implement this differently. Alternatively, an organisation may have more than one framework for biosecurity management, where approaches do not align. For example, the AU-IBAR 10-year aquaculture plan includes pest/pathogen impacts, but the policy reform strategy for fisheries and aquaculture does not specify this impact. Therefore, even in the case where organisations have the specific goal of reducing the impact of pests or pathogens in policy frameworks, the implementation strategy may not be aligned with this goal.

Future policy recommendations

Since identifying the major challenges to biosecurity policy in the carrageenophyte industry, short-term recommendations are given to help improve the use of current biosecurity frameworks, and longer-term recommendations for key organisations are provided in order to improve the integration of cultivated seaweeds into the international policy landscape (Fig. 5).

Conclusions

International biosecurity measures are limited by the lack of clear inclusion of cultivated seaweeds—including carrageenophytes—which makes it difficult to identify the roles and responsibilities of international organisations and their frameworks. The development of effective frameworks is also dependant on the availability of evidence-based research, which for seaweed cultivation and biosecurity risks is limited. As a result, current measures in international frameworks are not specifically addressing the biosecurity challenges faced by the industry. As the seaweed industry is unique in its focal host taxonomy (neither plant nor animal), and its presence in water, it has been difficult to align to well-established aquatic animal health and terrestrial crop biosecurity frameworks. The recent inclusion of algal species in IPPC recommendations is an important initial step in including seaweed in global aquaculture and biosecurity discussions. These measures now need to be further developed to all cultivated seaweed species and be fully inclusive of the biosecurity challenges specific to the seaweed industry. In the future, a strong scientific evidence base of biosecurity risks and their management, together with international policy frameworks designed for or to include the global seaweed industry, will be a key step to limiting the impact of diseases and pests on an international scale. Importantly, it is crucial that the low unit value (though high overall volume) of seaweed aquaculture should not be conflated with a perceived low risk of pathogen transfer, and low impact of subsequent economic and ecological impact in receiving nations.

References

Abolofia J, Wilen JE (2017) The cost of lice: quantifying the impacts of parasitic sea lice on farmed salmon. Mar Resour Econ 32:329–349

Alday-Sanz V, Brock J, Flegel TW, McIntoch R, Bondad-Reantaso MG, Salazar M, Subasinghe R (2018) Facts, truths and myths about SPF shrimp in aquaculture. Rev Aquac. https://doi.org/10.1111/raq.12305

Anderson PK, Cunningham AA, Patel NG, Morales FJ, Eptein PR, Dasak P (2004) Emerging infectious diseases of plants: pathogen pollution, climate change and agrotechnology drivers. Trends Ecol Evol 19:535–544

APEC (2010) Niigata declaration. 2010 Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation Ministerial Meeting on Food Security. Niigata, Japan. 16th October 2010. Available at: https://www.apec.org/Meeting-Papers/Sectoral-Ministerial-Meetings/Food-Security/2010_food. Accessed on 26 Nov 2019

APEC (2012a) Food security policies in Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation. APEC Policy Support Unit, September 2012. APEC#212-SE-01.11 123pp

APEC (2012b) Kazan declaration. 2012 Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation Ministerial Meeting on Food Security. Kazan, Russia. 30th May 2012. Available at: https://www.apec.org/Meeting-Papers/Sectoral-Ministerial-Meetings/Food-Security/2012_food. Accessed on 26 Nov 2019

APEC (2014a) Xiamen declaration - fourth Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation ocean-related ministerial meeting- AOMM4 towards new partnership through ocean cooperation in the Asia Pacific region. pp 1–7 Available at: http://mddb.apec.org/Documents/2014/MM/AOMM/14_aomm_jms.pdf. Accessed on 26 Nov 2019

APEC (2014b) Beijing declaration on Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation food security. Third APEC ministerial meeting on food security. Beijing, China. 19th September 2014. Accessed at: https://www.apec.org/-/media/Files/Groups/HLPDAB/2015/Beijing-Declaration-APEC-3rd-Miniserial-Meeting-on-Food-Security.pdf?la=en&hash=8F0B659EADB3DFCB59EFD016C57AF3050B7DDEF9 on 26 Nov 2019

ASEAN (2015a) ASEAN integrated food security (AIFS) framework and strategic plan of action on food security in the ASEAN region (SPA-FS) 2015-2020. Association of Southeast Asian Nations. pp 1-32. Available at: https://www.asean-agrifood.org/?wpfb_dl=58. Accessed on 26 Nov 2019

ASEAN (2015b) Guidelines on ASEAN good aquaculture practice (ASEAN GAqP) for food fish Jakarta. Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Pp 1-36. Available at: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/ASEAN-GAqP.pdf. Accessed on 26 Nov 2019

ASEAN (2016) Strategic plan of action on ASEAN cooperation on fisheries. Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Pp 1-32 available at: https://asean.org/storage/2016/10/Strategic-Plan-of-Action-on-ASEAN-Cooperation-in-Fisheries-2016-2020.pdf. Accessed on 26 Nov 2019

AUC & NEPAD (2014) The policy framework and reform strategy for fisheries and aquaculture in Africa. African Union Commission and NEPAD Planning and Coordinating Agency. pp 1–62. Available at: https://au.int/web/sites/default/files/documents/30266-doc-au-ibar_-_fisheries_policy_framework_and_reform_strategy.pdf. Accessed on 26 Nov 2019

AU-IBAR (2015) A guide for the implementation of the policy framework and reform strategy for fisheries and aquaculture in Africa. African Union- Inter African Bureau for Animal Resources pp 1–58

AU-IBAR (2016) The Continental Aquaculture Development Action Plan 2016 – 2025. Stakeholders’ perspectives for implementing the Policy Framework and Reform Strategy for Fisheries and Aquaculture in Africa. African Union- Inter African Bureau for Animal Resources. pp 1–33 Available at: http://www.au-ibar.org/component/jdownloads/finish/77-sd/3084-the-african-union-ten-years-aquaculture-action-plan-for-africa-2016-2025. Accessed on 26 Nov 2019

Barbier M, Charrier B, Araujo R, Holdt SL, Jacquemin B, Rebours C (2019) In: Barbier M, Charrier B (eds) PEGASUS - PHYCOMORPH European guidelines for a sustainable aquaculture of seaweeds, COST action FA1406, Roscoff. https://doi.org/10.21411/2c3w-yc73

Bolton JJ (2019) The problem of naming commercial seaweeds. J Appl Phycol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-019-01928-0

Bondad-Reantaso MG, Subasinghe RP, Arthur JR, Ogwa K, Chinabut S, Adlard R, Tan Z, Shariff M (2005) Disease and health management in Asian aquaculture. Vet Parasitol 132:249–272

Bondad-Reantaso MG, Sumption K, Subasinghe R, Lawrence M, Berthe F (2018) Progressive management pathway to improve aquaculture biosecurity (PMP/AB)1. FAO Aquac Newslett 58:9–11

Chaminade C, Padilla Pérez R (2014) The challenge of alignment and barriers for the design and implementation of science, technology and innovation policies for innovation systems in developing countries. In: Research Handbook on Innovation Governance for Emerging Economies. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK pp 181–204

Cottier-Cook EJ, Nagabhatla N, Badis Y, Campbell M, Chopin T, Dai W, Fang J, He P, Hewitt CL, Kim GH, Huo Y, Jiang Z, Kema G, Li X, Lui F, Liu H, Liu Y, Lu Q, Luo Q, Mao Y, Msuya FE, Rebours C, Shen H, Stentiford GD, Yarish C, Wu H, Yang X, Zhang J, Zhou Y, Gachon CMM (2016) Safeguarding the future of the global seaweed aquaculture industry. United Nations University (INWEH) and Scottish Association for Marine Science Policy Brief. pp 1–12

Critchley AT, Largo D, Wee W, Bleicher-Lhonneur G, Hurtado AQ, Schubert J (2004) A preliminary summary on Kappaphycus farming and the impact of epiphytes. Jap J Phycol 52:231–232

Dahlstrom A, Hewitt CL, Campbell ML (2011) A review of international, regional and national biosecurity risk assessment frameworks. Mar Policy 35:208–217

Eschen R, Britton K, Brockerhoff E, Burgess T, Dalley V, Epanchin-Niell RS, Gupta K, Hardy G, Huang Y, Kenis M, Kimani E, Li HM, Olsen S, Ormrod R, Otieno W, Sadof C, Tadeau E, Theyse M (2015) International variation in phytosanitary legislation and regulations governing importation of plants for planting. Environ Sci Pol 51:228–237

FAO (2007) Biosecurity toolkit. Food and Agriculture Organisation of United Nations. Rome, FAO 128 pp. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0703993104

FAO (2018) The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2018 - meeting the sustainable development goals. Food and Agriculture Organisation of United Nations, Rome

FAO & IPPC (2017) Plant health and food security. In: International Plant Protection Convention. Food and Agriculture Organisation of United Nations. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i7829e.pdf. Accessed on 26 Nov 2019

Hayashi L, Hurtado AQ, Msuya FE, Bleicher-Lhonneur G, Cricthley AT (2010) A review of Kappaphycus farming: prospects and constraints. In: Seckbach J, Einav R, Israel A (eds) Seaweeds and their role in globally changing environments. Cellular origin, life in extreme habitats and astrobiology, Springer, Dordrecht pp 251-283

Hill JE (2008) Non-native species in aquaculture: terminology potential impacts and the invasion process. South Regional Aquaculture Center. SRAC Publication No 4303. pp 1–8

Hunter MC, Smith RG, Schipanski ME, Atwood LW, Mortensen DA (2017) Agriculture in 2050: recalibrating targets for sustainable intensification. Bioscience 67:386–391

Hurtado AQ, Critchley AT, Trespoey A, Lhonneur GB (2006) Occurrence of Polysiphonia epiphytes in Kappaphycus farms at Calaguas Is., Camarines Norte, Phillippines. J Appl Phycol 18:301–306

Hurtado AQ, Critchley AT, Neish IC (eds) (2017) Tropical seaweed farming trends, problems and opportunities: focus on Kappaphycus and Eucheuma of commerce. Springer, Cham

IPPC (2012) Aquatic plants and their uses and risks- a review of the global status of aquatic plants. International Plant Protection Convention. pp 1-94. Available at: https://www.ippc.int/largefiles/2012/IPPC-IRSS_Aquatic_Plants_Study_2012-Final.pdf. Accessed on 26 Nov 2019

IPPC (2016) International Standard for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPM) 2- framework for pest risk analysis. International Plant Protection Convention. pp 2-16. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-k0125e.pdf. Accessed on 26 Nov 2019

IPPC (2017a) Recommendation on: IPPC coverage of aquatic plants. Adopted in 2014. International Plant Protection Convention. R04-2017. pp 1-2. Available at: https://www.ippc.int/static/media/files/publication/en/2017/04/R_04_En_2017-04-26_Combined_Ga7t6lx.pdf. Accessed on 26 Nov 2019

IPPC (2017b) International Standard for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPM) 11- pest risk analysis for quarantine pests. International Plant Protection Convention. pp 11-37. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-j1302e.pdf. Accessed on 26 Nov 2019

IPPC (2019) Official pest report (Art. VIII.1a) (1-794 of 794). International Plant Protection Convention. Available at: https://www.ippc.int/en/countries/all/pestreport/.

Kim JK, Yarish C, Hwang EK, Park M, Kim Y (2017) Seaweed aquaculture: cultivation technologies, challenges and its ecosystem services. Algae 32:1–13

Loureiro R, Gachon CMM, Rebours C (2015) Seaweed cultivation: potential and challenges of crop domestication at an unprecedented pace. New Phytol 206:489–492

Moreira D, Le Guyader H, Philippe H (2000) The origin of red algae and the evolution of chloroplasts. Nature 405:69–72

NACA (2000) Asia regional technical guidelines on health management for the responsible movement of live aquatic animals and the Beijing consensus and implementation strategy. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper. Food and Agricultural Organisation, Rome. pp 1–53

Oerke EC (2006) Crop losses to pests. J Agric Sci 144:31–43

OIE (2017) Aquatic Animal Health Code. World Organisation for Animal Health. Twentieth Edition, 2017. pp 1–289

Pereira L, Neto JM (2014) Marine algae: biodiversity, taxonomy, environmental assessment, and biotechnology. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Porse H, Rudolph B (2017) The seaweed hydrocolloid industry: 2016 updates, requirements, and outlook. J Appl Phycol 29:2187–2200

Quiaoit HAR, Uy WH, Bacaltos DGG, Chio PBR (2018) Seaweed area GIS-based mapping. Production support system for sustainable seaweeds farming in the Philippines 2016 report. Xavier University Press, Manila, pp 1–139

Savary S, Ficke A, Aubertot JN, Hollier C (2012) Crop losses due to diseases and their implications for global food production losses and food security. Food Secur 4:519–537

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (2000) Cartagena protocol on biosafety to the convention on biological diversity: texts and annexes. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, pp 1–30 Available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/legal/cartagena-protocol-en.pdf

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (2011) Nagoya protocol on access to genetic resources and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from their utilization. Conv Biol Divers United Nations. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.48.091801.112645

Stentiford GD, Sritunyalucksana K, Flegel TW, Williams BAP, Withyachumnarnkul B, Itsathitphaisarn O, Bass D (2017) New paradigms to help solve the global aquaculture disease crisis. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006160

Vairappan CS, Chung CS, Hurtado AQ, Msuya FE, Lhonneur GB, Critchley A (2008) Distribution and symptoms of epiphyte infection in major carrageenophyte- producing farms. J Appl Phycol 20:477–483

Valderrama D, Cai J, Hishamunda N, Ridler N, Neish IC, Hurtado AQ, Msuya FE, Krishnan M, Narayanakumar R, Kronen M, Robledo D, Gasca-Leyva E, Fraga J (2015) The economics of Kappaphycus seaweed cultivation in developing countries: a comparative analysis of farming systems. Aquac Econ Manag 19:251–277

Watkiss P, Pye S, Hendriksen G, Maclean A, Bonjean M, Jiddawi N, Shaghude Y, Sheikh MA, Khamis Z (2012) The economics of climate change in Zanzibar. In: Vulnerability, Impacts and Adaptation, Technical Report no. 4. Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar (RGZ). Final Summary Report. July 2012. pp 1–36. Available at: http://www.economics-of-cc-in-zanzibar.org/images/Final_Summary_vs_3.pdf. Accessed on 26 Nov 2019

WHO (2016) Codex Alimentarius- understanding codex, Fifth edn. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations and World Health Organisation, Rome, pp 1–50

WTO (2018) Sanitary and phytosanitary measures: text of the agreement. The WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement). World Trade Organisation. Available at: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/sps_e/spsagr_e.htm. Accessed on 26 Nov 2019

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Global Seaweed STAR team for their time and comments in the development of this work.

Funding

This work was supported by the Global Challenge Research Fund (GCRF) (Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council; Grant 2007 No. BB/P027806/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 32 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Campbell, I., Kambey, C.S.B., Mateo, J.P. et al. Biosecurity policy and legislation for the global seaweed aquaculture industry. J Appl Phycol 32, 2133–2146 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-019-02010-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-019-02010-5