Abstract

Studies repeatedly find that women and men experience life in academia differently. Importantly, the typical female academic portfolio contains less research but more teaching and administrative duties. The typical male portfolio, on the other hand, contains more research but less teaching and administration. Since previous research has suggested that research is a more valued assignment than teaching in academia, we hypothesise that men will be ranked higher in the peer-evaluations that precede hirings to tenured positions in Swedish academia. We analyze 861 peer review assessments of applicants in 111 recruitment processes in Economics, Political Science, and Sociology at the six largest Swedish universities. Our findings confirm that the premises established in previous research are valid in Sweden too: Women have relatively stronger teaching merits and men relatively stronger research merits, and also that, on balance, research is rewarded more when applicants are ranked by reviewers. Accordingly, male applicants are ranked higher compared to female applicants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For the past 40 years, the share of female university students as well as doctoral students has increased dramatically in most parts of the world. However, the transformation towards gender equality in academia is not nearly as apparent when it comes to the share of women among tenured lecturers and full professors. The share of women drops about ten percentage points at each promotional stage after graduate studies, so that ultimately the share of women who are full professors is down to approximately one-third (McFarland et al., 2017; Renwick Monroe et al., 2014). Thus, it is unsurprising that the road towards greater gender equality in tenure rates has been described as ‘excruciatingly slow’ (Larrán George et al. 2016; see also Tessens et al., 2011; Marschke et al., 2007), and others maintain that the gender gap in tenure rates is actually not closing at all (e.g. Perna, 2005).

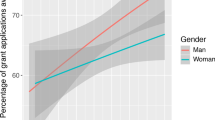

Arguably, this situation is intimately associated with the gendered division of labour in academia, which several studies have observed. This division of labour inevitably hampers women’s career opportunities since there is an undeniable and sharp difference in how men and women experience academia. These differences are well characterised in The Washington Post’s “Monkey Cage´s” symposium on the gender gap in academia (Voeten, 2013). To name but a few such differences that have been reported in the literature: women teach and perform lesser-ranked administrative services to a larger extent than men, while men conduct more research (see e.g. Kalm, 2019; Guardino & Borden, 2017; Coate & Kandiko Howson, 2016; Nature, 2016; European Commission, 2008). Furthermore, a gender gap in citations has been observedFootnote 1 (Dion et al. 2018); a gender bias is present in research grant peer review (Tamblyn et al., 2018); male academics are more likely than women to be accepted to peer-reviewedFootnote 2 conferences (Times Higher Education, 2019); and gender plays a significant role in influencing how students rate their instructors – to the disadvantage of women (MacNell et al., 2015). Furthermore, even when women are just as scientifically competent as men, there is still a significant gender gap in career advancement that is not explained by gender differences in productivity (Filandra & Pasqua, 2019; see also Wullum Nielsen, 2016, however compare Madison & Fahlman, 2020; Kulp, 2020), and women are more likely to be steered into part-time positions, making it less likely for them to transfer to full-time positions (Lundby & Warme, 1990).

In addition, studies have shown that male academics are more satisfied with their salary, their promotions, and experience greater job satisfaction compared to their female colleagues (Okbara et al., 2005). Finally, female academics experience higher overall levels of job-related stress (Doyle & Hind, 2002). Taken together, these gender differences make it reasonable to expect that they negatively affect the career opportunities of female scholars. For instance, even after controlling for productivity, women are less likely than men to be promoted to full professors (August & Waltman, 2004; Perna, 2001), and furthermore, salaries for women are generally lower compared to those of men with similar academic track-records (Barbezat & Hughes, 2005; Carr et al., 2015).

It is fair to say, then, that gender differences in academia regarding division of labour, availability of career opportunities and salaries are both real and significant. In this article, we set out to perform an explorative study on the effect of these differences in terms of who is recruited to tenured positions and based on what merits. The aim is to analyse whether the gender differences of division of labour, described above, are reproduced in universities’ hiring processes, amounting to what we dub a potential ‘double discrimination’ in academia.

This will be studied in a Swedish context. Some previous qualitative studies of the Swedish case indicate that there is indeed a gendered division of labour in Swedish academia – to the disadvantage of women (Angervall & Beach, 2017, 2018; Angervall et al., 2015). A review from the Swedish National Board of Higher Education, which was based on 22 different projects, concluded that the meritocratic ambitions of higher education institutions in Sweden is hampered ‘by norms and values that confirm men as superior and that different conditions are active regarding women’s and men’s meriting and carrier development.’ Such norms and values are fostered by informal power configurations and procedures, making it hard for those who do not have access to informal networks to compete on equal terms (UHR, 2020: 29f, our translation). We can also tell from large-n studies that variations along gender lines still exist to a rather high degree in Sweden, in terms of recruitment to higher education, recruitment to prestigious programs and new demarcations between men and women who make it to higher education (Berggren, 2008, 2011, on the latter point see also Haley, 2018).

All of this notwithstanding, Sweden is still consistently ranked among the most gender equal countries (e.g. Equal Measures, 2019; The Global Gender Gap Report 2018; cf. Madison & Fahlman, 2020). Against this backdrop we can draw the conclusion that Sweden is apparently not a gender equal utopia, but nevertheless a country that has taken important steps, and more steps compared to many other countries, towards gender equality. Despite the remaining challenges related to gender equality we therefore view Sweden as a ‘more likely’ case when it comes to finding gender equality for academics, at least compared to most other countries.

Much previous research on equality in academia has been carried out in somewhat less gender-equal, Anglo-Saxon contexts. A crucial question is, therefore, whether gendered differences can be observed when we turn our eyes to the Swedish setting, where gender equality – according to several international comparisons – is regarded to have progressed the most. Consequently, viewing Sweden as a relatively more likely setting to observe gender equality, we argue that if reproduction of gender differences is observed in Swedish academic hiring processes, it is plausible to conclude that similar differences persist, and are presumably magnified, in other settings.

Research Questions

We argue that our explorative study – which asks whether the gender differences of division of labour are reproduced in hiring processes – has the potential to further the knowledge on gender divisions in higher education in general, and within the field of recruitment to tenured positions in particular. In order to study these gender differences of division of labour, and whether these differences have the potential to be reproduced, we analyse hiring processes to tenured positions as senior lecturers that took place in Sweden between 2003 and 2013 within Economics, Political science and Sociology. Our data was collected from peer-review evaluation reports (sakkunnigutlåtanden, in Swedish) which include rankings of the applicants as well as reviewers’ arguments for their ranking decisions. We describe this unique data-set in more detail below, but it should be stressed that the data gives us opportunities to study the division between women and men in terms of a) how they are ranked by their peers in the evaluation reports, and b) the specific merits – e.g. teaching vs. research – ascribed to women and men respectively. To fulfil the paper’s aim, we ask the following research questions:

-

To what extent are women and men ascribed different types of merits in the evaluation process? Are these differences consistent across disciplines?

-

How often are different types of merits the determinant factor in the recruitment process? Are there differences between disciplines in this respect?

The paper proceeds as follows. First, we spell out the theoretical points of departure where we present our assumptions of why gender divisions in academic recruitment processes are to be expected. Second, we present our methodological considerations and discuss case selection and the specifics of the Swedish higher education system, before moving on to present the data and how it is analysed. Third, we proceed to present our results and interpret these, before ending the paper with a concluding discussion.

A Double Discriminatory Effect? Assumptions and Hypotheses

As concluded by the European Commission (2008), there still exists an often-held gender stereotype that views female academics, first and foremost, as ‘talented teachers’, exhibiting excellent soft skills such as communication and a sensitive approach to, and open ear for, students. On the other hand, men in academia tend to be viewed as analytical, objective, hard thinking researchers. As stated in the EC-report, these images are mirrored in a division of labour where female academics are typically stuck with teaching duties and administrative tasks with lower status, whilst men are doing research, echoing the stereotype ‘women teach, men think’.

As already indicated, the descriptions in the EC-report have been confirmed in previous as well as later studies. A number of studies have shown that women and men employed in academia experience and react to their work environments differently – largely in ways unfavorable to women. Research indicates that female academics are paid less than men (Carr et al., 2015; Toutkoushian & Conley, 2005). Moreover, it has been found that female academics do more housework at home than their male counterparts (Scheibinger & Gilmartin, 2010), and they find it much harder to achieve a work-life balance (O’Laughlin & Bischoff, 2005). Moreover, female academics spend more time on teaching and on public-engagement tasks, and less time on research, than their male counterparts, this according to a survey of UK university staff in science-based subjects (Nature, 2017; see also Sax et al., 2002). Partly as a consequence of this, somewhat older studies found that female faculty are less likely to be promoted to the rank of full professors – even after controlling for productivity and human capital (Perna, 2001; Toutkoushian, 1999, cf. Filandra & Pasqua, 2019), although it is unclear whether this imbalance has been redressed in recent years (Guarino & Borden, 2017). However, a ‘smoking gun’ that indicates that there still is some way to go even in such a gender-equal country as Sweden, is that women constitute only 28 per cent of the country’s full professors (Allbright, 2019). Against this backdrop, if previous findings from the general international literature on gender and academic careers are valid for the Swedish context too, four hypotheses are specified and will be tested in this article:

H1: Female applicants to tenured positions as senior lecturers have stronger teaching merits, than male applicants.

H2: Male applicants have stronger research merits, than female applicants.

H3: Candidates with stronger research merits are prioritized, before candidates with stronger teaching merits.

H4: It follows from H1-H3 that male applicants are ranked higher than female applicants in peer-review evaluations that precede the hiring of senior lecturers.

In our analysis, three academic disciplines are included (Economics, Political Science, and Sociology). This is done to facilitate an analysis of a high number of hiring processes within a limited scope of time. The three disciplines are related, all being close to the core of social sciences. However, each discipline can reasonably be expected to have developed their own separate norms and routines, which may affect how merits and hiring processes are viewed. This means that although the differences between academic disciplines are not at the center of our analyses, our design still provides us with the opportunity to explore potential variation between disciplines.

This endeavor is motivated by results from previous research on ‘academic tribalism’ (Becher, 1989, 1994; Neumann, 2001). According to this literature, we could expect Economics to be closer to the ideal type of what Biglan (1973) labelled ‘hard pure’ (the ideal of natural sciences) while Sociology comes closer to ‘soft pure’ (the ideal of social sciences), with Political Science somewhere in-between. In ‘hard pure’ disciplines we are, according to Becher, expected to find a culture that is described as ‘competitive, gregarious; politically well-organised; high publication rate; task-oriented’, while the ‘soft pure’ culture is described with characteristics such as ‘individualistic, pluralistic; loosely structured; low publication rate; person-oriented’ (Becher, 1994). From this follows, we argue, an expectation of a stronger focus within Economics on output that can be more easily measured (i.e. research publications), while Sociology and to some extent Political Science can be expected to have stronger focus on portfolios with a better balance between teaching and research. This also reveals a non-universal understanding of academic meritocracy where the understanding of meritocracy varies between contexts. One form of meritocracy can be expected to discriminate against women, while another form may not be expected to do so. Hence, if the ‘academic tribalism’ argument has any merit, the disadvantage of women is expected to be most pronounced in Economics and least so in Sociology.

These differences are supported by research on how we define research activities. As some have argued, even the conceptions of research differ between men and women, and a narrower conception work in the favor of men (Healey & Davis, 2019). A narrower understanding of research comes close to the ‘hard pure’ type above. What we have referred to as ‘soft pure’ can instead, tentatively, be expected to be stronger both within certain disciplines and among women. Although our aim here is straightforward and empirical, these observations still motivate us to reflect also on social relationships between and within different genders, disciplines and research environments.

In sum, based on the empirical studies discussed above, women are expected to be discriminated against twice. Since they, as a rule, are stereotyped as talented teachers and administrators, they are allocated relatively less time and other resources to do research. Then, when they apply for tenured positions, they are expected to be discriminated against again, since their talents in the pedagogical and administrative fields are valued less, compared with research merits. This is precisely the potential double discriminatory effect we aim to explore.

Data and Methods

Our dataset comprises 861 data points. One data point equals one applicant in one evaluation report (321 female applicants, 536 male applicants, and 4 missing cases). Most hiring processes involve two external reviewers who are urged to independently evaluate the applicants and then rank them.Footnote 3 This implies that, in most cases, each applicant forms two data points in our data set. The 861 data points concern a total of 111 hiring processes at the six largest Swedish universities: Gothenburg; Linköping; Lund; Stockholm; Umeå; and Uppsala.Footnote 4 The data we acquired from the universities did include more than these 111 hiring processes, but we choose to exclude some of these for varying reasons. For instance, we excluded hiring processes that did not include any competition because there was only one applicant. We also excluded those hiring processes which concerned disciplines outside the scope of this study, and those where the evaluation reports were incomplete. These are rare exceptions that do not affect the overall results of our study.Footnote 5

In each of the evaluation reports, for all applicants, we measured the space in the report devoted to teaching merits and research merits, respectively. If a reviewer devoted one page discussing teaching merits for a certain candidate, and four pages to discussing research merits, this was coded as 20 per cent teaching merits and 80 per cent research merits. We also coded the gender of the applicant, the gender of the reviewer, the academic discipline of the position the recruitment process concerns, and finally the ranking of the applicants for the specific position.

We use descriptive statistics to describe the merits of the applicants, and OLS regression analyses to study the effects of gender and of different kinds of merits on the ranking of applicants. We discuss the use of these methods in more detail when we present the results.

Before moving on to our analyses, a few additional comments are warranted. One important reservation concerns the difficulty reviewers encounter when measuring teaching/pedagogical merits. While research merits (or scientific merits, as they are typically referred to in the evaluation reports) are more easily quantified (e.g. number of publications, impact factor or ranking of the journals where articles are published, number of citations, etc.), teaching merits are, as a rule, perceived to be harder to quantify and also evaluate qualitatively. After having read an abundance of evaluation reports, we can conclude that due to perceived difficulties of evaluating teaching merits, such evaluations are typically summarised in a rather parsimonious way. The reviewer usually concludes by stating something along the lines that the applicant has been a teacher for so-and-so many years (or has taught for so-and-so many teaching hours), and can therefore be considered an experienced teacher.Footnote 6 In other words, the quantity of teaching is used as an extremely crude proxy for measuring quality in teaching. At least to us, this implies a very undifferentiated and shaky strategy.

Given the (perceived) difficulties of the reviewers to evaluate teaching merits, a rather short discussion on teaching merits, compared with a lengthier discussion on research merits, should not necessarily be understood as an indication that the reviewer values teaching merits less. However, there is no reason to expect that these negative conditions vary between universities, disciplines or gender. We can, therefore, expect the reviewers to have similar conditions for their work and that variations in the space devoted to different merits between different groups of applicants must say something substantial about how different merits are valued by evaluators. Such variation between universities, disciplines and gender can have different explanations, and it is outside the scope of this article to explain such variation. Our initial theoretical discussion does, however, provide us with potential explanations against which the results could be read. We return to these potential explanations in the concluding section. But let us now turn to our empirical results.

The Effects of Different Kinds of Merits on the Ranking of Applicants

Based on our review of previous research – admittedly, primarily carried out in Anglo-Saxon settings – there are strong reasons to expect that female applicants to academic positions will have stronger teaching merits, while male applicants will have stronger research merits. Since research historically and typically has had a higher status than teaching (see e.g. Fairweather, 2005), we also expect that candidates with stronger research merits will be prioritised before candidates with stronger teaching merits when reviewers ultimately rank candidates. For instance, this is what Parker (2008) found for evaluations preceding promotions to the ranks of reader and professor in the UK: research excellence is prioritised over teaching activities (cf. Fairweather, 2005). To test these hypotheses, we initially present a descriptive overview of the applicants and their merits.

In Table 1, we see that evaluation reports concerning female candidates are generally more occupied with teaching merits compared to evaluations of male candidates. As we can see in the bottom rows of the table, this pattern holds even if we only focus on the top ranked candidates. However, reports on applicants for senior lectureships in Sociology differ somewhat. Here, reports on female candidates devote slightly less space to teaching merits, compared with the reports on male candidates. However, this ‘sociology’-factor does not challenge the overall picture: as a rule, evaluation of teaching merits is more extensive in the case of female candidates. From these descriptive statistics, where ‘volume in evaluation reports’ is used as a proxy, we draw the tentative conclusion that female applicants have (relatively) stronger teaching merits and (relatively) weaker research merits. Nonetheless, a possible interpretation is that reviewers are primed to associate female candidates more with teaching.

Let us move on to study the effect of these differences on the ranking of the applicants. We do so through linear regression analyses where the effect of different variables on the ranking of the candidates is tested. We start out by studying the effects on ranking decisions of the reasons given by reviewers for rankings. In our coding of the evaluation reports we assessed whether the reviewers, when deciding upon the ranking of a particular applicant, based their ranking decision equally on the applicant’s research and teaching merits, primarily on their research merits, or primarily on their teaching merits. Sometimes the reviewers explicitly state their reasons for particular ranking decisions in the reports, but on other occasions a measure of interpretation of the evaluation reports was required in order to assess the ultimate reason behind the ranking decisions. This resulted in a categorisation of all our data points into three groups: applicants whose ranking was determined by research and teaching merits equally; applicants whose ranking was determined by research merits; and applicants whose ranking was determined by teaching merits.

Next, we estimate the effect of belonging to a certain group on the ranking one is afforded. The method for this is to represent group membership with dummy variables that take on values 0 and 1; membership in a particular group is coded one whereas non-membership in the group is coded zero. In order to avoid introducing multicollinearity, the general rule is to include one less dummy variable in the model than there are categories. Consequently, we constructed two dummy variables; one for the group of applicants whose ranking was determined by research merits, and one for the group whose ranking was determined by teaching merits. This means that the applicants whose ranking was determined by research and teaching merits to an equal extent will receive the value 0 on both dummy variables and will function as the reference group (Alkharusi, 2012).

When dummy coding is used in OLS regression analyses, the overall results indicate whether there is a relationship between the dummy variables and the dependent variable, which in our case is the ranking of an applicant (Alkharusi, 2012). The intercept obtained using OLS estimation will represent the mean of the group coded 0 on all the dummy variables which, in our case, is the group of applicants whose ranking was determined by research and teaching merits to an equal extent. The regression coefficients will represent the deviation from the mean of this reference group for the other two groups. By adding the value of the regression coefficients to the intercept we will obtain the mean ranking of the two groups of applicants whose rankings were determined by either research merits or teaching merits.

Table 2 shows the results of our OLS regression model using the two dummy variables. What we see is a comparison between the three different groups in terms of the average ranking afforded by the reviewers, where 1 signifies the ranking afforded to the strongest candidate. As can be seen in the table, applicants whose ranking was determined by research and teaching merits to an equal extent were on average afforded a rank of around 2.2. Hence, belonging to this group yields the best outcome, on average. Belonging to the group of applicants whose ranking was determined by research merits yields the second-best outcome, as the applicants in this group were afforded a rank of around 2.7, on average. Lastly, belonging to the group of applicants whose ranking was determined by teaching merits yields the worst outcome, as these applicants were on average given a rank of around 3.1. This confirms our third hypothesis, i.e. that candidates with stronger research merits are prioritised before candidates with stronger teaching merits.

The Effects of Gender on the Ranking of Applicants

So far, we have established that 1) female applicants are generally deemed to have stronger teaching merits and weaker research merits relative to men (except for in Sociology where this pattern was reversed), and 2) that applicants with stronger teaching merits and weaker research merits are ranked lower than applicants with stronger research merits and weaker teaching merits, and lower still than applicants with equally strong research and teaching merits. This would lead us to expect that it is also the case that 3) female applicants are generally ranked lower than male applicants. We use linear regression analyses to study whether this is the case.

We construct a basic bivariate regression model (A) with the gender of the applicant as independent variable, and the ranking afforded by the reviewers as dependent variable.Footnote 7 The results are reported in Table 3, first for all the disciplines taken together and then broken down for each discipline. The constants in the table indicate the average ranking of a male candidate (remember that 1 is the highest rank). The regression coefficients on the ‘Gender of applicant’-row indicate how female candidates are ranked compared to male candidates; a positive number means that female candidates are ranked lower than male candidates, and a negative number that they are ranked higher. The values of the coefficients tell us how many steps above (if negative) or below (if positive) female candidates are ranked compared to male candidates.

Since we are studying a total population, we are not going to attach much importance to statistical significance. On the other hand, we will be quite cautious in our interpretations and focus mainly on the direction of the effects on rankings, i.e. whether women are ranked higher or lower than men, and not pay much attention to differences in ranking steps.Footnote 8 Another reason for being cautious is that we have to make the somewhat controversial assumption that there is equidistance between different scale steps in the rankings, i.e. that the distance between rankings 1 and 2 is the same as between rankings 2 and 3, and so on.Footnote 9

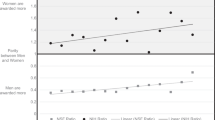

When we analyse our data, we do indeed identify a tendency that female candidates are, on average, ranked lower than male candidates. In the first column of Table 3 we can see that female candidates are ranked slightly lower than male candidates when we study all three academic disciplines together. When the results are broken down by disciplines a more complicated and interesting, pattern emerges. We can see that the general pattern of female candidates being ranked lower than male candidates holds for both Political Science and Economics, and this tendency seems to be strongest within Economics. For Sociology however, the pattern is the reverse: female candidates are on average ranked higher than male candidates.

Once again, we wish to stress that these results need to be interpreted with caution. If we look at the effects on scale steps, we see that for Political science and Sociology, there seems to be only a rather modest effect in that being a female candidate will put you about a fifth of a scale step below (for Political Science) or above (for Sociology) male candidates. For Economics, the difference is almost half a scale step. From this we can at least tentatively conclude that there are tendencies in our data that confirms H4, i.e. that male applicants are ranked higher than female applicants in peer-review evaluations that precede the hiring of senior lecturers. As we have seen, however, this is not true for Sociology.

How can we understand the fact that Sociology seems to deviate from the general pattern? Although it falls outside the aim of our study to explain the differences between disciplines, the literature on tribalism and different conceptions of research still gives us the opportunity to reflect on the differences. What we have discussed above as a narrower conception of research, more often favored by men, and the ‘hard pure’ type of academic discipline, could be expected to be closer related to Economics, while a wider conception of research, more often favored by women, and the ‘soft pure’ type of discipline could be expected to be closer to Sociology, with Political Science somewhere in-between. At least tentatively, our results lend credibility to this argument, where the ‘softer’ discipline of Sociology provides women with greater career opportunities, while a ‘harder’ discipline such as Economics provides women with fewer opportunities.

In sum, our findings support the premise that has found solid support in previous research, i.e. the stereotype ‘women teach, men think’. Women tend to have (relatively) stronger teaching merits and men (relatively) stronger research merits. Moreover, we have also identified a tendency that female candidates are, on average, ranked lower than male candidates. We have emphasized that these results should be interpreted with caution, but the differences are still there, which makes it possible for us to at least say that the men and women we have studied here had different opportunities, to a varying degree between different disciplines.

Conclusion

Based on previous research, which has univocally found a gendered division of labour in academia, we set out to study who is awarded tenured positions as senior lectures in recruitment processes, and on what merits such awarding is based.

Our premise was that there is a gendered division of labour within academia where – as the European Commission (2008) phrased the stereotype – ‘women teach, men think’; i.e. men conduct relatively more research. This assumption was verified in our empirical findings. The typical ‘male academic portfolio’ contains stronger research merits compared with those of women, while the typical ‘female academic portfolio’ contained relatively stronger teaching merits. However, we observed interesting differences between disciplines: Sociology displayed the reverse pattern compared with the hypothesized one. This answered our first research question: To what extent are women and men ascribed different types of merits in the evaluation process, and are differences consistent across disciplines?

Our second research question was: How often are different types of merits the determining factor in recruitment processes, and are there differences between disciplines in this respect? We demonstrated that reviewers devote more space in their reports to evaluate research merits. However, our findings showed that the effect on the ranking of candidates is strongest when reviewers make an assessment of research and teaching merits as being of equal strength. Still, the positive effect on the ranking of research merits is stronger compared with the positive effect of teaching merits.

In order to reach the aim – to analyze whether the gender differences of division of labour are reproduced in universities’ hiring processes – we have also studied the effect the differences discussed here have on the ranking of applicants. Here we have concluded that male applicants are ranked higher than female applicants in peer-review evaluations that precede the hiring of senior lecturers. This is at least the case in Economics and, to a lesser degree, in Political Science. As we have seen, however, this is not true for Sociology, where the reverse pattern is observed.

Let us return to our hypotheses. H1 and H2 are verified: Female applicants do have stronger teaching merits compared with their male competitors and male applicants do have stronger research merits compared with their female competitors. We can to some extent also verify H3: candidates with stronger research merits are, relatively speaking, rewarded more than candidates with stronger teaching merits. But it is important to note that the determining factor with the strongest effect on rankings is the combination of strong merits in both teaching and research. H4, that male applicants are ranked higher in peer-review evaluations that precede the hiring of senior lecturers can also be – somewhat cautiously – verified, at least for Political Science and Economics, but not for Sociology.

We should also remember that it is not unreasonable to expect that women who invest time and energy, in addition to risking one's prestige, in applying for senior lectureships self-select from a pool of the most motivated women. They may not, therefore, be representative of female academics in general. Potential female applicants, with typical ‘female academic portfolios’ – a heavy teaching load, more low-valued administrative work – may anticipate that the kind of experiences and qualities they possess will be discriminated against, and hence, they abstain from applying. Therefore, while our study on this self-selected pool of motivated applicants already confirm that there is discrimination against typical ‘female academic portfolios’ – i.e. strong track-records in teaching and administrative work, we can expect this effect to be even stronger in the full population of female university teachers.

Lastly, a brief afterthought on the implications of our findings. We have seen how the most competitive women tend to have typical ‘male academic portfolios’, i.e. they have strong research as well as teaching merits; and that teaching – for all intents and purposes – is downgraded in hiring processes. This result mirrors what Parker (2008) found studying promotion processes in the UK. In the wake of the ‘massification’ of higher education, this is as depressing as it is truly puzzling. In Sweden, as well as in the UK and several other countries, there has been – at a rhetorical level, at least – a strong movement towards strengthening rewards for teaching excellence. Governments have urged universities to improve the status of teaching and it has become de facto mandatory for academics to complete teacher training programmes to get promoted or hired. However, given our results – and as Parker (2008) concluded more than a decade ago – despite widespread public endorsements, the value of teaching is not reflected in reward-structures in higher education; and much points to the fact that, for the majority of female academics, this fact ultimately puts them at a disadvantage when it comes to hiring, promotions and salary development.

Data Availability

Data available through the corresponding author.

Notes

This can, at least to some extent, be ascribed to the tendency of men to self-cite to a considerably larger degree than women do (King et al., 2017). From the 1990s and onwards, men self-cited 70 percent more than women.

Note that this particular result applies to conferences within the field of Economics.

The evaluation and the ranking are reported to the faculty office at the relevant university in the form of a public evaluation report.

The number of recruitment cases for each university in our data was: Lund: 24; Uppsala: 21; Gothenburg: 18; Linköping: 13; Umeå: 9; and Stockholm 16.

We requested all evaluation reports concerning the review of applicants for all open positions as senior lecturers in Economics, Political science and Sociology during 2003–2013. We cannot guarantee that we received all reports, but our random checks indicate that we have received all or at least almost all of the reports.

This rather parsimonious treatment of teaching merits in many of the evaluation reports is interesting in itself and says something about the weight ascribed to the teaching experience of the applicants, despite teaching being the main task for many senior lecturers.

We have also constructed multivariate models with a number of control variables, such as the gender of the reviewer and which university is appointing the position, but none of the controls change the results reported here in any substantial way.

From looking at the R-squared values in table 3 we can also see that the explanatory powers of the models are quite low; they explain below or slightly above one percent of the variance in the ranking variable. This is not surprising given that we study very few variables.

An alternative way to analyse our data, which would not rely on this assumption, is to perform a logistic regression analysis which models the probability of a particular outcome, such as the probability of a candidate with certain characteristics of becoming ranked number 1. When we perform such an analysis we see that for female candidates in our dataset the odds ratio of becoming ranked number 1 is 0.89 compared to male candidates. If we look at the three disciplines separately, we see that for female economists the odds ratio of becoming ranked number 1 is 0.61 compared to male economists, for female political scientists the odds ratio is 0.62 compared to male political scientists, and for female sociologists the odds ratio of becoming ranked number 1 is 1.49 compared to male sociologists. This confirms the general patterns we saw in the OLS regressions.

References

Alkharusi, H. (2012). Categorical Variables in Regression Analysis: A Comparison of Dummy and Effect Coding. International Journal of Education, 4(2) 202–210.

Allbright. (2019). Vetenskapsmannen inte kvinna. Stockholm: Allbright foundation.

Angervall, P., & Beach, D. (2017). Dividing Academic Work: Gender and Academic Career at Swedish Universities. Gender and Education, 32(3), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2017.1401047

Angervall, P., & Beach, D. (2018). The Exploitation of Academic Work: Women in Teaching at Swedish Universities. Higher Education Policy, 31(1), 1–17.

Angervall, P., Beach, D., & Gustafsson, J. (2015). The Unacknowledged Value of Female Academic Labour Power for Male Research Careers. Higher Education Research and Development, 34(5), 815–827.

August, L., & Waltman, J. (2004). Culture, Climate, and Contribution: Career Satisfaction Among Female Faculty. Research in Higher Education, 45, 177–192.

Barbezat, D. A., & Hughes, J. W. (2005). Salary Structure Effects and the Gender Pay Gap in Academia. Research in Higher Education, 46, 621–640.

Becher, T. (1989). Academic Tribes and Territories. Open University Press.

Becher, T. (1994). The Significance of Disciplinary Differences. Studies in Higher Education, 19(2), 151–161.

Berggren, C. (2008). Horizontal and Vertical Differentiation within Higher Education – Gender and Class Perspectives. Higher Education Quarterly, 62, 20–39.

Berggren, C. (2011). Gender equality policies and higher education careers. Journal of Education and Work, 24(1–2), 141–161.

Biglan, A. (1973). The Characteristics of Subject Matter in Different Scientific Areas. Journal of Applied Psychology, 57, 195–203.

Carr, P. L., Gunn, C. M., Kaplan, S. A., Raj, A., & Freund, K. M. (2015). Inadequate Progress for Women in Academic Medicine: Findings From the National Faculty Study. Journal of Women’s Health, 24(3), 190–199.

Coate, K., & Kandiko Howson, C. (2016). Indicators of Esteem: Gender and Prestige in Academic Work. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 37(4), 567–585.

Dion, M., Lawrence Sumner, J., & McLaughlin Mithcell, S. (2018). Gendered Citation Patterns across Political Science and Social Science Methodology Fields. Political Analysis, 26(3), 312–327.

Doyle, C., & Hind, P. (2002). Occupational Stress, Burnout and Job Status in Female Academics. Gender Work and Organization, 5(2), 67–82.

Equal Measures (2019). Harnessing the Power of Data for Gender Equality. Surrey: Equal Measures.

European Commission. (2008). Mapping the Maze: Getting more women to the top in research. European Commission.

Fairweather, J. S. (2005). Beyond the Rhetoric: Trends in the Relative Value of Teaching and Research in Faculty Salaries. The Journal of Higher Education, 76(4), 401–422.

Filandra, M., Pasqua, S. (2019). ‘Being Good isn’t Good Enough’: Gender Discrimination in Italian academia. Studies in Higher Education, early view online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03075079.2019.1693990

Global Gender Gap Report. (2018). “The Global Gender Report 2018.” Cologne/Geneva: World Economic Forum.

Guardino, C., & Borden, V. (2017). Faculty Service Loads and Gender: Are Women Taking Care of the Academic Family? Research in Higher Education, 58(6), 672–694.

Haley, A. (2018). Returning to rural origins after higher education: gendered social space. Journal of Education and Work, 31(4), 418–432.

Healey, R., & Davies, C. (2019). Conceptions of ‘research’ and their gendered impact on research activity: a UK case study. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(7), 1386–1400.

Kalm, S. (2019). Om akademiskt hushållsarbete och dess fördelning. Sociologisk Forskning, 56(1), 5–26.

Kulp, A. M. (2020). Parenting on the Path to the Professoriate: A Focus on Graduate Student Mothers. Research in Higher Education, 61, 408–429.

King, M. M., Bergstrom, C. T., Correll, S. J. Jacquet, J., West, J. D. (2017). Men Set Their Own Cites High: Gender and Self-citation Across Fields and Over Time. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 3: 1–22.

Larrán George, M., Javier Andrades, F., & Gomez Cana, M. C. (2016). Gender Differences Between Faculty Members in Higher Education. Educational Research Review, 18, 58–69.

Lundby, K. L. P., & Warme, B. D. (1990). Gender and career trajectory: The case of part-time faculty. Studies in Higher Education, 15(2), 207–222.

MacNell, L., Driscoll, A., & Hunt, A. N. (2015). What’s in a Name: Exposing Gender Bias in Student Ratings of Teaching. Innovation in Higher Education, 40, 291–303.

Madison, G., Fahlman, P. (2020). Sex differences in the number of scientific publications and citations when attaining the rank of professor in Sweden. Studies in Higher Education, published online 06 Feb 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1723533

McFarland, J., Hussar, B., de Brey, C., Snyder, T., Wang, X. Wilkinson-Flicker, S., Gebrekristos. S. (2017). The Condition of Education 2017. NCES 2017–144. National Center for Education Statistics.

Marschke, R., Laursen, S., Nielsen, J. M., & Rankin, P. (2007). Demographic Inertia Revisited: An Immodest Proposal to Achieve Equitable Gender Representation Among Faculty in Higher Education. Journal of Higher Education, 78, 1–26.

Nature. (2016). “Men Cite Themselves More Than Women Do.” July 16. https://www.nature.com/news/men-cite-themselves-more-than-women-do-1.20176

Nature. (2017). “Teaching Load Could put Female Scientists at Career Disadvantage.” April 13. https://www.nature.com/news/teaching-load-could-put-female-scientists-at-career-disadvantage-1.21839

Neumann, R. (2001). Disciplinary Differences and University Teaching. Studies in Higher Education, 26(2), 135–146.

Okbara, J. O., Squillace, M., & Erondu, E. A. (2005). Gender Differences and Job Satisfaction: a Study of University Teachers in the United States. Women in Management Review, 20(3), 177–190.

O’Laughlin, E. M., & Bischoff, L. G. (2005). Balancing Parenthood and Academia Work/Family Stress as Influenced by Gender and Tenure Status. Journal of Family Issues, 26, 79–106.

Parker, J. (2008). Comparing Research and Teaching in University Promotion Criteria. Higher Education Quarterly, 62(3), 237–251.

Perna, L. W. (2001). Sex and Race Differences in Faculty Tenure and Promotion. Research in Higher Education, 42(5), 541–567.

Perna, L. W. (2005). Sex Differences in Faculty Tenure and Promotion: The Contribution of Family Ties. Research in Higher Education, 46, 277–307.

Renwick Monroe, K., Choi, J., Howell, E. Lampros-Monroe, C. Trejo, C., Perez, V. (2014). Gender Equality in the Ivory Tower, and How Best to Achieve It. PS: Political Science & Politics, 47(2), 419.

Sax, J. J., Hagedorn, L. S., Arredondo, M., & Dicrisi, F. A. (2002). Faculty Research Productivity: Exploring the Role of Gender and Family-Related Factors. Research in Higher Education, 43, 423–446.

Schiebinger, L., & Gilmartin, S. K. (2010). Housework is an Academic Issue. Academe, 96, 39–44.

Tamblyn, R., Girard, N., Qian, C. J., & Hanley, J. (2018). Assessment of Potential Bias in Research Grant Peer Review in Canada. CMAJ, 190(16), 489–499.

Tessens, L., White, K., & Web, C. (2011). Senior Women in Higher Education Institutions: Perceived Development Needs and Support. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 33, 653–665.

Times Higher Education. (2019). Male Economists More Likely to Accept Papers by Other Men: Gap in Acceptance Rates for Major European Conferences Entirely Down to Behaviour of Male Referees. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/male-economists-more-likely-accept-papers-other-men

Toutkoushian, R. K. (1999). The Status of Academic Women in the 1990s No Longer Outsiders, But Not Yet Equals. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 39(5), 679–698.

Toutkoushian, R. K., & Conley, V. M. (2005). Progress for Women in Academe, Yet Inequities Persist. Research in Higher Education, 46(1), 1–28.

UHR. (2020). Jämställdhet i högskolan – ska den nu ordnas en gång för alla? https://www.uhr.se/globalassets/_uhr.se/lika-mojligheter/jamstalldhetsdelegationen/uhr-jamstalldhet-i-hogskolan.pdf (access February 18, 2021).

Voeten, E. (2013). Introducing the Monkey Cage Gender Gap Symposium. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2013/09/30/introducing-the-monkey-cage-gender-gap-symposium/

Wullum Nielsen, M. (2016). Gender inequality and research performance: moving beyond individual-meritocratic explanations of academic advancement. Studies in Higher Education, 41(11).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Linnaeus University. This study was funded by the Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy, Uppsala, Sweden.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brommesson, D., Erlingsson, G.Ó., Ödalen, J. et al. “Teach more, but do not expect any applause”: Are Women Doubly Discriminated Against in Universities’ Recruitment Processes?. J Acad Ethics 20, 437–450 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-021-09421-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-021-09421-5