Abstract

Adulthood has traditionally been defined by the attainment of socio-demographic milestones such as career, marriage, and parenthood, but these milestones are increasingly delayed or have become inaccessible for young people today. As a result, young people are likely to experience a discrepancy between their expectations for and their actual reality of adulthood, which can negatively affect their well-being and psychological development. To systematically study contemporary definitions of and attitudes towards adulthood, we assessed a sample of 722 UK adults with an age range from 18 to 77 years on: (a) subjective adult status, or the extent to which people feel like adults; (b) attitudes towards adulthood, or whether people think adulthood is a positive time of life; and (c) the characteristics that people use to define adulthood today. We found that most participants felt adult and had positive attitudes towards adulthood. Our participants defined adulthood predominantly through psychological characteristics, for example “Accepting responsibility for the consequences of my actions” (endorsed by 80% of the sample), rather than by socio-demographic milestones which were endorsed by only 22–40% of participants. Both subjective adult status and attitudes towards adulthood were significantly associated with older age and the attainment of the socio-demographic milestones of marriage and parenthood. Regression analyses revealed that having a positive attitude towards adulthood was the strongest psychological predictor of subjective adult status, accounting for 10% of the variance. This suggests that fostering positive attitudes towards adulthood may help improving the well-being of contemporary adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Perceptions of adulthood – whether people feel like adults, how they feel towards adulthood, and how they define adulthood – have changed substantially over the past 30 years (e.g., Arnett, 2000; Settersten, 2007; Sharon, 2016). Traditionally, adult status was defined by reaching the age of majority or legal age of adulthood, which is 18 years in most jurisdictions, or by the attainment of socio-demographic milestones such as having a career, getting married, and becoming a parent. These traditional milestones of adulthood were the core pillars of psychological models of lifespan development in the 1950 and 1960 s (e.g., Erikson, 1963; Havighurst, 1953), when paths to adulthood were relatively uniform, and people started long-term careers, marriage, and having children in quick succession during their early twenties (Blatterer, 2007a, b). In recent years, transitions to adulthood have taken place in a world that is increasingly characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity, where socio-demographic milestones are less likely to define adult status (e.g., Arnett, 2000, 2015; Blatterer, 2007b; Sharon, 2016). In WEIRD countries (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic; Henrich et al., 2010), people often settle into long-term careers later in adulthood, after prolonged periods of education and ‘job-hopping’. For example, in the US, Millennials born between 1980 and 1996 changed jobs twice as often as Generation X, who were born between 1965 and 1979, and three times more often than the Baby Boomers born between 1945 and 1964 (Lyons et al., 2015). Contemporary adults are also delaying or foregoing marriage and parenthood compared with previous generations. The average age of first marriage for women in the UK has risen from 25 to 35 years between 1970 and 2019 (ONS, 2012; Stripe, 2019), and marriage rates have fallen by 50% from 1991 to 2019 (Clark, 2023). For parenthood, the average age of first-time mothers in the UK has also increased, from 26 to 31 between 1970 and 2019 (Clark, 2023), and the number of children per woman has decreased from 2.9 to 1.6 between 1964 and 2020 (ONS, 2022).

These demographic trends in career, marriage, and parenthood result from individual choices, societal pressures, and normative cultural values (Blatterer, 2007b). Compared with previous generations, young adults today experience less social pressure to adhere to traditional models of adulthood, resulting in their pathways to adulthood becoming more varied (Blatterer, 2007b). Qualitative research suggests that young people embrace this uncertainty and flexibility of adulthood and are re-defining adulthood in a way that suits their lifestyles and the current sociohistorical climate (Blatterer, 2007b).

Defining Adulthood

Research shows that adults today define adulthood through psychological characteristics rather than by socio-demographic milestones (e.g., Arnett, 2001; Bao et al., 2023; Blatterer, 2007b; Kuang et al., 2023; Molgat, 2007; Obidoa et al., 2018; Settersten, 2007; Sharon, 2016; Sirsch et al., 2009). For example, in a recent survey, 55% of US respondents aged 18–25 endorsed being settled into a long-term career as defining adult status, 26% endorsed marriage, and 33% parenthood (N = 1,113; Sharon, 2016). In contrast, the items “Accept responsibility for the consequences of my actions”, “Make independent decisions”, and “Develop greater consideration for others” were endorsed by 96%, 95%, and 82% of the sample, respectively (Sharon, 2016). Thus, the most frequently endorsed characteristics of adulthood were psychological, not socio-demographic, emphasising the psychological development that occurs throughout adulthood beyond the traditional social roles of employee, spouse, and parent. However, it is unclear whether the low endorsement of socio-demographic milestones relative to that of psychological characteristics to define adult status is limited to emerging adults, who range in age from 18 to 29 years (Arnett, 2000, 2015), or if this phenomenon also holds true for older adults.

Previous research assessed the defining characteristics of adulthood using the Markers of Adulthood (MoA) scale (Arnett, 1994, 2001), which indexes the proportion of participants who endorse certain characteristics as important for adult status. The MoA scale was developed in the early 1990s (Arnett, 1994) and has been recently revised and updated (Norman et al., 2021). Although the revised MoA scale includes some psychological characteristics that describe adult status, such as accepting responsibility for one’s actions and deciding one’s beliefs and values independently (Arnett, 1994; Norman et al., 2021), other important qualities are not included, for example relying on and trusting in one’s abilities (Wright & von Stumm, 2023a, 2023b). To assess a broad range of psychological qualities of adulthood, we developed a scale based on the CARES taxonomy that identifies five qualities of adult development (Wright & von Stumm, 2023a, 2023b): (1) Cognitive maturity, pertaining to the confidence adults have in their own knowledge and abilities; (2) sense of Aging, which captures the realisation that one is aging and life is finite; (3) self-Reliance, defined as the ability to look after oneself; (4) Eudaimonia, entailing knowing and living in alignment with oneself; and (5) Social convoy, comprising of adults’ network of social relationships over their lives (Wright & von Stumm, 2023a, 2023b). These qualities are posited to be central pillars of adult development which impact adults’ mental health and well-being and are based on previous literature. Together, the CARES qualities map different aspects of psychological development: emotional (eudaimonia and social convoy), cognitive (cognitive maturity), motivational (self-reliance), and physical (sense of aging; Wright & von Stumm, 2023a, 2023b). Because the items of the MoA scale do not capture the five CARES qualities, we developed and administered a novel CARES scale in the current study, in addition to the MoA scale. We report here the proportion of participants who endorsed one or more of the five CARES qualities (cognitive maturity, sense of aging, self-reliance, eudaimonia, and social convoy), as well as those who endorsed items from the MoA scale, as defining characteristics of adulthood.

Subjective Adult Status

Subjective adult status describes the extent to which people identify as adults. It is usually assessed with a single-item question, such as “Do you feel that you have reached adulthood?” (e.g., Arnett, 1994; Axxe et al., 2022; Bao et al., 2023; Obidoa et al., 2018; Sirsch et al., 2009). Subjective adult status has been associated with chronological age, as older participants report feeling ‘adult’ to a greater extent than younger participants (Arnett, 2001; Sirsch et al., 2009). For example, in a sample of 515 US participants, 86% of those aged between 30 and 55 years reported feeling that they had reached adulthood, but only 46% of people aged 18 to 29 years, and 19% of adolescents aged between 13 and 17 years old classified themselves as adults (Arnett, 2001). While the effect of age on subjective adult status has been well documented, less is known about the influence of achieving socio-demographic milestones – career, marriage, and parenthood – on subjective adult status. We could only identify two previous studies in this area. The first reported that being married or having children significantly predicted subjective adult status in a sample of 119 female workers from China (Zhong & Arnett, 2014). Regardless of age, married women were 3.1 times more likely to view themselves as adults than were single women, and women with children were 3.4 times more likely to view themselves as adults than women without children (Zhong & Arnett, 2014). The second study found that being in a relationship predicted subjective adult status in a sample of 4,833 adolescents aged 11 to 17 years living in Mexico, Mozambique, and Nepal (Axxe et al., 2022). No study to date has assessed the predictors of subjective adult status in a sample with a wide age range that spans emerging, established, and late adulthood.

Attitudes Towards Adulthood

People’s attitudes towards adulthood as a life phase can be positive, for example when adulthood is viewed as a rich, dynamic, and empowering life period. Attitudes towards adulthood can also be negative, for example when adulthood is primarily thought of as a ‘career and care crunch’ during which adults must juggle the competing responsibilities of building their career and caring for young children and aging parents (Mehta et al., 2020). However, attitudes towards adulthood have not previously been studied. We expect that attitudes to adulthood will be in some ways analogous to attitudes towards aging, a concept which describes how people feel about the process of getting older (e.g., Ingrand et al., 2018; Wettstein & Wahl, 2021). Having a positive attitude towards aging and believing that people can gain competencies and capabilities as they age are associated with improved cognitive and physical functioning in later adulthood, as well as with greater health and well-being (Ingrand et al., 2018). Conversely, negative attitudes towards aging, defined by the belief that aging is accompanied by declines in all areas of life, are associated with worse physical functioning, health, and well-being in later adulthood (Wettstein & Wahl, 2021; Wurm et al., 2017). Many studies have shown that attitudes towards aging – whether people perceive aging as a positive or negative process – relate to well-being and mental health but associations between attitudes towards adulthood – whether people perceive adulthood as a positive or negative time of life – and well-being have not been tested before.

The Current Study

Our study had four aims. First, we sought to investigate how adulthood is defined by measuring the characteristics that today’s adults endorse to define adulthood. To do so, we assesed a large sample of UK adults with a wide age range on the revised MoA scale (Norman et al., 2021) and the CARES scale, which was developed for the current study (details in the measurement section). We expected that the psychological characteristics of the MoA scale would be endorsed as defining characteristics of adulthood more frequently than socio-demographic characteristics, such as marriage, parenthood, and career, consistent with previous research (e.g., Arnett, 1994, 2001; Sirsch et al., 2009). We made no specific hypotheses about the endorsement of the CARES scale, which was administered here for the first time.

Second, we aimed to measure attitudes towards adulthood, which to the best of our knowledge have not been previously investigated. We assessed attitudes towards adulthood using two novel measures, including whether participants thought adulthood was a positive or negative time of life, and whether they associated adulthood with positive or negative emotive words. Our analyses regarding attitudes towards adulthood were exploratory.

Third, we measured subjective adult status with a new assessment instrument. Our sample’s wide age range allows for the first time comparing levels of subjective adult status across age groups from emerging adulthood to old age. In line with previous research finding, we expected that participants, who were older and had entered into traditional ‘adult’ roles such as full-time work, marriage, and parenthood, reported higher subjective adult status (Arnett, 2001; Axxe et al., 2022; Zhong & Arnett, 2014).

Finally, we tested the relative strength of predictors of subjective adult status, including age, the attainment of socio-demographic milestones, and attitudes towards adulthood. These analyses were exploratory. All hypotheses and methods were preregistered on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/wzsbj) ahead of data collection.

Method

Participants

A total of 722 UK residents (53% female) were recruited via the online survey platform Prolific (https://www.prolific.com/). Age was normally distributed (Mage = 39.20, SD = 13.14, range 18 to 77 years). We differentiated four age groups based on previous literature: (1) emerging adulthood (aged 18–29 years; Arnett, 2000;, 2015) included 207 participants (29% of the sample); (2) established adulthood (aged 30–45 years; Mehta et al., 2020) included 300 participants (42%), (3) midlife (aged 46–59 years; Lachman, 2004) included 143 participants (20%), and (4) older adulthood (i.e., age 60 and above) included 72 participants (9%).

One third of our sample reported being married or in a civil partnership (n = 261; 36%), one third identified as being in a committed relationship (n = 223; 31%), and one third identified as single (n = 238; 33%). Our sample included 347 parents (48%) and 375 non-parents (52%).

To index their career status, participants reported if they had experienced full-time, part-time, or no employment. We chose employment status as a measure of career to accommodate younger participants who may not have started a ‘career’ but are in employment. Over two-thirds of our sample reported being in full-time employment (n = 511; 71%), with 18% in part-time employment (n = 129), and 11% stating not to be in employment (n = 82). Full characteristics of the sample are shown in Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials.

Sample Size Rationale

Our target sample size was 700 based on power analyses and suggested sample sizes in the literature. First, for correlations, a minimum of 250 participants is recommended for covariances to stabilise (Schönbrodt & Perugini, 2013). Second, for our preregistered ANCOVA analyses we performed a G*Power analysis (Faul et al., 2007), which suggested a minimum of 700 participants was necessary to detect a small-to-medium effect size in an ANOVA (Cohen’s f = 0.20; η² = 0.06). Third, our regression analyses, which were not pre-registered, required a minimum of 172 participants to detect a small effect size (0.15) with an alpha value of 0.05 according to G*power (Faul et al., 2007).

Missing Data

We applied pairwise omission to missing data. Analysis samples are reported in the results section below.

Procedure

Data were collected in June and July of 2022. The authors received ethical approval from the Department of Education, University of York Ethics Committee in April 2022. Participants completed a 165-item survey on Prolific with an average completion time ~ 15 min. The survey included measures of demographic factors, self-perceived adult status, attitudes towards adulthood, and defining characteristics of adulthood. Participants provided informed consent, and all personal and identifying information was removed prior to extracting the data for analysis. Participants received £1.80 to their Prolific account as compensation for their participation.

A pilot (N = 5) was carried out to test (a) the time taken to complete the survey and (b) the effectiveness of the data quality control items. We utilised Geo-IP address blockers, so that only participants with IP addresses registered in the UK could access the survey. Five attention checks item were embedded throughout the survey, such as “If you are paying attention, select agree”. Participants who failed any attention check item or who did not complete the survey were excluded from the analyses. A total of 778 participants were recruited for this study. Fifty-six participants did not complete the study either because they failed the attention checks (N = 38), timed out (N = 11), or stopped the study before completion (N = 7). In total, 722 participants were included in analyses.

Measures

Demographic Characteristics

To assess demographic characteristics, we asked participants their (a) gender, with the responses: “Male”, “Female”, or “Prefer not to say”; (b) highest educational qualification, with responses: “GCSE”, “A-Level”, “Undergraduate degree”, “Master’s degree”, “Doctorate”, or “Other”; (c) relationship status, with responses “Single”, “In a committed relationship”, or “Married or in a civil partnership”; (d) income, which participants entered manually; and (e) employment, with the prompt “Have you ever been in salaried employment?”, participants responded with: “Yes, full-time”, “Yes, part-time”, or “No”. We chose to ask whether participants had ever been in salaried employment rather than their current employment status as we wanted to assess the impact of employment on perceptions of adulthood, and the experience of having been employment could still impact one’s perception of themselves as an adult even if they are currently not in employment. For example, participants may be out of employment due to childcare or retirement, but their previous experience of employment could still impact their self-perceived adult status.

Defining Characteristics of Adulthood

We measured the defining characteristics of adulthood using a combination of the Revised Markers of Adulthood scale (Revised MoA; Norman et al., 2021) and the CARES scale, which was developed for this study.

The Markers of Adulthood scale (MoA; Arnett, 1994) was revised by Norman and colleagues (2021) to reflect the modern transition to adulthood using literature reviews, focus groups, and empirical analysis. The resulting Revised MoA consisted of 22 items across four subscales: independence (e.g., “Being financially independent from parents”), legality markers (e.g., “Having reached age of legal adulthood”), role transitions (e.g., “Being married”), and relative maturity (e.g., “Accepting responsibility for the consequences of your actions”). Intra-subscale correlations range from 0.26 to 0.63 (Norman et al., 2021). The revised MoA has a coefficient alpha of 0.89 (Norman et al., 2021), suggesting high internal consistency. Descriptive statistics of all scales included in this study, including internal consistency values, are presented in Table 1.

The CARES scale was developed to reflect the CARES taxonomy (Wright & von Stumm, 2023a, 2023b), a descriptive model of psychological development in adulthood. The CARES taxonomy consists of five qualities of psychological development, which are described briefly here.

Cognitive maturity is the confidence that adults have in their own knowledge to solve problems and address challenges in life. Every individual builds up a diverse and unique body of knowledge across life through experiences in a variety of domains such as education, career, relationships, and interests (Ackerman, 2022). Cognitive maturity is not defined by the amount or content of one’s knowledge, but the confidence that one holds in their knowledge. Self-confidence has been associated with well-being beyond competence levels (e.g., Schneider et al., 2022), suggesting that having confidence in one’s knowledge has positive implications for adults’ mental health and well-being.

Sense of Aging is twofold. First, sense of aging involves an adult’s recognition of their own aging and the aging of others around them, for example through signs of physical decline such as grey hair, wrinkles, and a reduced resilience to injury and stress. Second, adults have a sense of time remaining in life, and the realisation that time is limited impacts individuals’ motivations and goals (i.e., socioemotional selectivity theory; Carstensen et al., 1999). Individuals who perceive time as limited are more likely to pursue goals that provide emotional meaning in the present moment, which has been shown to improve their subjective well-being (Sullivan-Singh et al., 2015).

Self-Reliance describes an adult’s sense of control in life, and their ability to rely on their own inner strength to overcome challenges. Adults who are self-reliant have an internal locus of control, meaning that they ascribe events in their lives to their own actions and behaviour (Churchill et al., 2020). An internal locus of control has been associated with positive economic, social, and psychological outcomes (Cobb-Clark et al., 2014).

Eudaimonia comes from the Greek words ‘eu’ meaning ‘good’ and ‘daimon’ meaning ‘spirit’ which relates to the ancient Greek adages “Know thyself” and “Become who you are”. The quality of eudaimonia is defined as knowing oneself and living in alignment with one’s true character. Knowing oneself has positive effects on mental health and well-being (Ryff & Singer, 2013), and pursuing activities that are in alignment with one’s character also has a positive impact on subjective well-being (Waterman et al., 2010).

Social convoy is the network of relationships in a person’s life including family, friends, romantic partners, children, colleagues, and acquaintances. This network changes across the lifespan (Wrzus et al., 2013). A ‘convoy’ is a group that travels together for mutual protection (Cambridge Dictionary, 2023), and an individual’s social convoy is protective for mental health and well-being in adulthood. Individuals receive support from, and give support to, their social convoy, both of which have positive effects on mental health and well-being (e.g., Sehmi et al., 2020).

The CARES scale consists of 25 questions relating to the five CARES qualities of adult development: Cognitive maturity (e.g., “Being able to solve problems in life”), sense of Aging (e.g., “knowing that life is finite”), self-Reliance (e.g., “Having control over my life”), Eudaimonia (e.g., “Living in alignment with who I am”), and Social convoy (e.g., “Having people in my life who understand and support me”). Items in the MoA and CARES scales and their respective subscales are shown in tables S3 and S4 in the supplementary materials.

For both the revised MoA and the CARES scales, participants were presented with the prompt “This defines adulthood for me” and asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.). Each participant had a unit-weighted average scores ranging from 1 to 5 for each of the 22 revised MoA items, and the 25 CARES items.

Subjective Adult Status

In previous research, subjective adult status has been assessed using a single-item measure: “Do you think that you have reached adulthood?”, with responses: “yes”, “no”, and “in some respects yes, in some respects no” (e.g., Arnett, 1994; Zhong & Arnett, 2014). Single item measures are more susceptible to measurement error and can have lower reliability in cross-sectional samples compared with multiple-item measures (Allen et al., 2022). We developed a five-item measure to assess subjective adult status in this study.

The subjective adult status scale includes the items: “I feel like an adult”, “I no longer feel like a child”, “Other people consider me an adult”, “Other people treat me like a child” (reverse-scored), and “I think of myself as a grown-up person”. Participants rated items on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = always.) An average score from 1 to 5 was calculated for each participant, with a higher number indicating a higher level of subjective adult status (i.e., a higher score indicates that the participant feels like an adult more frequently compared with a lower score).

Attitudes Towards Adulthood

Attitudes towards adulthood were measured using (a) the attitudes towards adulthood scale, and (b) the valenced attitudes towards adulthood scale, both developed for this study. The attitudes towards adulthood scale comprised of six items: “Adulthood is a desirable phase of life”, “I enjoy being an adult”, “Overall, adulthood is a positive time of life”, “Adulthood is not a desirable phase of life” (reverse scored), “I dislike being an adult” (reverse scored), and “Overall, adulthood is a negative time of life” (reverse scored). All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.) A composite score was calculated for each participant, representing their overall attitude towards adulthood from 1 to 5, where a higher number indicates a more positive attitude.

The valenced attitudes towards adulthood scale consisted of 30 emotive words (15 positive and 15 negative) selected from the English Word Database of Emotional Terms (EMOTE; Grühn, 2016). The word selection procedure and full word list are reported in the supplementary materials. To measure valenced attitudes towards adulthood, participants were asked whether they agreed with the following statement: “This word describes adults in general”, on a dichotomous scale consisting of “agree” or “disagree”, coded as 1 and 0, respectively. For each participant, we calculated a total numerical score between 0 and 15 for both positive and negative words. A higher score on the positive words scale indicated more positive attitudes towards adulthood, and a higher score on the negative words scale indicated more negative attitudes towards adulthood. Total scores for the endorsement of positive words and negative words correlated at r = −.41. In line with our preregistered analysis plan (https://osf.io/b7pjw), we treated the endorsement of positive and negative words as two separate domains in the following analyses since the two scales correlated at less than 0.60. For comparison, positive and negative valence scores correlated with the attitudes towards adulthood scale at 0.45 and −0.39, respectively.

Results

Data were analysed using R (R core team, 2022). Analysis scripts and data are available on the OSF; the analyses reported here were preregistered amongst other analyses of these data (https://osf.io/b7pjw).

Descriptive statistics for all study measures are in Table 1, and their correlations are shown in Table 2. All study scales had satisfactory Cronbach’s alpha values (α > 0.75), with the exception of the legality markers subscale of the MoA scale (α = 0.57). Across scales and measures, data were normally distributed.

Defining Characteristics of Adulthood

To assess the defining characteristics of adulthood, we first measured the frequency with which participants endorsed the items of the MoA scale (e.g., Arnett, 1994; Norman et al., 2021). Traditional milestones of adulthood were endorsed by less than half of participants. Full-time employment was endorsed by 28% of participants, marriage by 22%, and parenthood by 26%. The most frequently endorsed items from the MoA scale were “Accepting responsibility for the consequences of my actions” (endorsed by 80% of participants), “Being financially independent from my parents” (79%), and “Paying for my own living expenses” (79%). The least endorsed items were “Having had sexual intercourse” (endorsed by 15% of participants), “Being married” (22%), and “Having obtained a driver’s license” (23%). The subscales of independence and relative maturity were endorsed the most frequently in the MoA scale, by almost two thirds of our sample (57% of participants endorsed each). Role transitions and legality markers were only endorsed by a third of our sample (33% and 27% respectively). Figure 1 shows the percentage endorsement for the five most endorsed and five least endorsed items in the MoA and CARES scales.

We performed frequency analysis of items from the CARES scale in the same manner as we did for the MoA scale. The most frequently endorsed items from the CARES scale were all from the self-reliance subscale: “Being able to look after myself” (endorsed by 76% of participants), “Making my own choices without having to rely on others” (74%), and “Having control over my life” (70%). The self-reliance subscale was the most endorsed of all subscales in the MoA and CARES scales, with 68% of participants agreeing that self-reliance items define adulthood. The least frequently endorsed subscale of the CARES scale was social convoy (endorsed by 48%). The least endorsed items were “Being satisfied with my social network” (endorsed by 34% of participants) and “Having true connections with others” (37%). Figure 1 shows the percentage endorsement for the five most endorsed and five least endorsed items in the MoA and CARES scales. Endorsement % of individual items from the MoA and CARES scales is shown in table S6 of the supplementary materials.

Percentage of endorsement of defining characteristics of adulthood. Note: Fig. 1 shows the five most and least endorsed items from the Markers of Adulthood (MoA) and CARES scales. Item names have been shortened for clarity. Figure 1.1 shows the average endorsement of characteristic types: psychological, financial, socio-demographic, and legal. Graph colours also refer to characteristic types

Defining Characteristics of Adulthood by Age

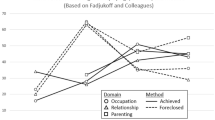

We assessed whether endorsement of traditional socio-demographic milestones as defining characteristics of adulthood varied by age group (Fig. 2). “Being settled into a long-term career” was endorsed on average by 40% of our participants. By age groups, career was endorsed by 48% of participants aged 18–29 years, 41% of participants aged 30–45 years, 30% of participants aged 46–59 years, and 31% of participants aged 60–77 years. Thus, being settled into a long-term career was more often considered a defining characteristic of adulthood at younger than at older ages. “Being married” and “Having had at least one child” were endorsed most often by the 30–45 year old group (26% and 33%, respectively), but less so by younger and older adults. Endorsement of all MoA and CARES items by age group can be found in tables S7 and S8 of the supplementary materials.

Percentage endorsement of traditional socio-demographic milestones as defining characteristics of adulthood. Note: The respective items were “Having had at least one child”, “Being married”, and “Being settled into a long-term career”. Grey bars refer to the overall proportion of participants who endorsed each item (i.e., across all age groups). A total of 26% of participants endorsed parenthood, 22% marriage, and 40% career

Subjective Adult Status

On average, participants felt like adults, as shown by a mean score of 3.87 on the subjective adult status scale (SD = 0.79). Older participants felt more adult than younger participants, shown by the positive correlation between subjective adult status and age (r = .38, p < .001; Table 2).

Predictors of Subjective Adult Status

We ran multiple regression models to explain differences in subjective adult status. Model 1 included as predictors the demographic factors gender, education, and income, model 2 also included age in years as a continuous predictor, and in model 3, we added employment, relationship, and parenthood. Model 4 included attitudes towards adulthood, specifically scores on the attitudes towards adulthood scale, and positive and negative valence towards adulthood.

Model 1 was significant (F(710) = 18.96, p < .001, R2 = 0.07), with educational attainment and income explaining 7% of the variance in subjective adult status. Gender was not significant (Table 3, see also Supplementary Materials for full regression outputs). In model 2, age significantly predicted subjective adult status, accounting for 11% of the variance (F(712) = 40.22, p < .001, R2 = 0.18). Employment, relationship, and parent status accounted for an extra 4% of the variance (model 3: F(706) = 22.86, p < .001, R2 = 0.22). Model 4, including all predictors, explained a total of 32% of the variance in scores on the subjective adult status scale (F(703) = 28.43, p < .001), with attitudes towards adulthood accounting independently for 10% of the variance (Table 3). The results of model 4 suggest that participants reported feeling significantly more adult if they were older, had children, were in a relationship, had a higher income, or had a positive attitude towards adulthood.

Attitudes Towards Adulthood

Participants had a positive attitude towards adulthood overall, indicated by a mean score of 3.52 on the attitudes towards adulthood scale (SD = 0.88), ranging from 0 (strongly disagree that adulthood is positive) to 5 (strongly agree that adulthood is positive). This equates to positive items being on average rated between agree and strongly agree, and negative items between disagree and strongly disagree.

On the valenced attitudes towards adulthood scale, participants had a mean score of 10.33 (SD = 3.60) for endorsement of the 15 positive words, and a mean of 7.16 (SD = 3.77) for the 15 negative words, showing that participants had more positive attitudes towards adulthood overall. The most frequently endorsed words to describe adults were “versatile” (positive; endorsed by 91% of participants), “interesting” (positive; endorsed by 88%), and “frustrated” (negative; endorsed by 86%). The least endorsed words were “useless” (negative; endorsed by 2% of participants), “unskilled” (negative; endorsed by 4%), and “unkind” (negative; endorsed by 28%). Endorsement of individual items in the valenced attitudes towards adulthood scale are shown in Table S5.

The Impact of Age and Socio-Demographic Roles on Perceptions of Adulthood

We fitted one-way ANCOVAs to assess differences in the perceptions of adulthood by (a) age groups (i.e., 18–29, 30–45, 46–59, or 60+), (b) employment group (i.e., full-time, part-time, or no employment), and (c) relationship group (i.e., married, in a relationship, or single). The influence of parent status (i.e., parent or non-parent) on perceptions of adulthood was determined by t-tests. All ANCOVAs were adjusted for gender, educational attainment, and income. Post-hoc Tukey tests were used to investigate group differences. Results are summarised in Fig. 3.

Perceptions of adulthood by age, employment, relationship, and parent groups. Note: Dotted lines indicate mean scores (3.87 on subjective adult status scale, 3.52 on attitudes towards adulthood scale, 3.76 for positive word endorsement, and 2.91 for negative word endorsement). Stars indicate statistical significance: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. All ANCOVAs were adjusted for gender, educational attainment, and income

First, age group had a significant effect on subjective adult status (F(3) = 38.86, p < .001, η² = 0.14). A post-hoc Tukey test revealed that emerging adults (age 18–29) scored significantly lower on subjective adult status than the other age groups (p < .001), and established adults (age 30–45) scored significantly lower than participants aged 60 and above (p = .002). Age group was also significantly associated with scores on the attitudes towards adulthood scale (F(3) = 20.21, p < .001, η² = 0.08) and the valenced attitudes towards adulthood scale (F(3) = 6.53, p < .001, η² = 0.03). Emerging adults had significantly more negative attitudes towards adulthood compared with all other age groups (p < .001), and participants aged 60 and above had significantly more positive attitudes towards adulthood compared with established adults (p < .001) and midlife adults (p = .01). Emerging adults endorsed positive words significantly less often than established adults (p = .001), midlife adults (p = .003), and those aged 60 and above (p = .007). Furthermore, participants aged 60 and above were significantly less likely to endorse negative words compared with all other age groups (18–29 p < .001, 30–45 p < .001, and 46–59 p = .03).

Second, employment status had a significant effect on subjective adult status (F(2) = 11.09, p < .001, η² = 0.03). A post-hoc Tukey test indicated that participants in part-time employment scored significantly lower on the subjective adult status compared with those in full-time employment (p < .001) and with those not in employment (p = .01). Participants in full-time employment also had significantly more positive attitudes towards adulthood compared with those in part-time employment (F(2) = 8.61, p < .001, η² = 0.02). On the valenced attitudes towards adulthood scale, ANCOVA analysis showed differences in the endorsement of positive words by employment group (F(2) = 6.32, p = .002, η² = 0.02). Participants who had experienced full-time employment were significantly more likely to endorse positive words compared with those in part-time employment (p = .01) or no employment (p = .04). Employment group was not associated with the endorsement of negative words.

Third, relationship status had a significant effect on subjective adult status (F(2) = 26.90, p < .001, η² = 0.07), as married participants scored significantly higher on subjective adult status compared with those in a relationship (p < .001) and single participants (p < .001). Relationship group was also associated with attitudes towards adulthood (F(2) = 11.08, p < .001, η² = 0.03), as married participants had more positive attitudes towards adulthood compared with those in a relationship (p = .002) and single participants (p < .001). Married participants also endorsed more positive words compared with single participants (F(2) = 5.91, p = .003, η² = 0.02). Relationship group was not associated with the endorsement of negative words.

Finally, parents scored significantly higher on the subjective adult status scale (t(705.15) = 8.31, p < .001, d = 0.62), and had significantly more positive attitudes towards adulthood (t(710.40) = -3.88, p < .001, d = 0.29) compared with non-parents. Parents also endorsed more positive words on the valenced attitudes towards adulthood scale compared with non-parents (t(719.11) = -3.87, p < .001, d = 0.29), and non-parents endorsed more negative words than parents (t(698.85) = 4.05, p < .001, d = 0.30).

Discussion

In the current study, we investigated the defining characteristics of adulthood in a UK sample with a wide age range from 18 to 77 years. We also measured and predicted people’s attitudes towards adulthood – whether they perceive adulthood as a positive or negative time of life – and their subjective adult status – the extent to which people consider themselves adults. We discuss our findings with regard to these three outcomes – defining adulthood, attitudes towards adulthood, and subjective adult status – in turn below.

Defining Characteristics of Adulthood

Our participants defined adulthood more often by psychological characteristics and financial markers than by socio-demographic milestones, in line with previous research (e.g., Arnett, 2001; Bao et al., 2023; Blatterer, 2007b; Kuang et al., 2023; Molgat, 2007; Obidoa et al., 2018; Settersten, 2007; Sharon, 2016; Sirsch et al., 2009). The items that were most frequently endorsed were: “Accepting responsibility for the consequences of my actions”, “Being financially independent from my parents”, “Paying for my own living expenses”, “Being able to look after myself”, and “Making my own choices without having to rely on others” (Fig. 1). In contrast, the socio-demographic milestones of career, marriage, and parenthood were among the least endorsed items. These findings imply that the endorsement of psychological characteristics to define adulthood holds true across ages and is not restricted to emerging adults.

Endorsement of defining characteristics of adulthood varied by socio-demographic milestones and age. Career was endorsed more frequently than marriage and parenthood, particularly by participants aged 18 to 29 years (emerging adults) and 30 to 45 years (established adults). Those aged 30 to 45 years endorsed being married and a parent more often as defining characteristics of adulthood than participants of other ages. Due to the cross-sectional nature of our data, we cannot determine whether these differences represent age effects or cohort effects. However, we speculate that cohort effects are likely: Our participants’ birth years spanned from 1945 to 2004, and they entered adulthood between the 1960s and the 2020s, a time period during which significant changes occurred in education and work in the UK. For example, more people attend university today than ever before: in 1970, 8% of school leavers attended university (Bolton, 2012), compared with 47% in 2020 (Department for Education, 2023). Higher rates of university enrolment suggest increased time investments in education and career development during young adulthood, with adults placing greater emphasis on their careers. Another example is women’s rise in workplace participation, which increased from 42 to 57% between 1970 and 2020 (Watson, 2023) and coincides with declining rates of marriage and parenthood in the UK (e.g., Clark, 2023; ONS, 2012; Stripe, 2019). Together these societal trends are likely to bring about cohort effects, such that people born in earlier years endorse having a career less often as defining characteristic of adulthood than people born in later years.

Attitudes Towards Adulthood

Our sample’s attitudes towards adulthood were overall positive, with most participants agreeing that adulthood is an enjoyable time of life and selecting positive words to describe adults. That said, attitudes towards adulthood varied by age. Older participants had more positive attitudes towards adulthood and endorsed a higher frequency of positive words to describe adults than younger participants. The greater positivity of older adults feeling may reflect self-protective biases of adults to view their contemporaneous lifetime in ways that promote well-being and encourage successful aging (e.g., Ingrand et al., 2018; Jenull et al., 2023). Attitudes towards adulthood also differed according to the attainment of socio-demographic milestones. Participants who were employed full-time, married, and had children reported more positive attitudes towards adulthood and endorsed more positive words to describe adults compared with participants who were employed part-time, single, or childfree.

The simultaneous attainment of socio-demographic milestones of marriage, career, and parenthood and the resulting responsibilities have been referred to as the ‘career-and-care-crunch’ (Mehta et al., 2020). It occurs as people juggle the challenge of progressing in their careers and their caring responsibilities for young children and/ or aging parents (Mehta et al., 2020). One may expect that attitudes towards adulthood become more negative as people enter the life phase of the career-and-care crunch. However, we found that established adults and those who had attained socio-demographic milestones had more positive attitudes towards adulthood than emerging adults, suggesting that the career-and-care crunch does necessarily bring about negativity towards adulthood. The attainment of socio-demographic milestones could promote positive attitudes towards aging through social comparisons, when people who are employed, married, or have children, compare themselves favourably to those who have not (yet) achieved these milestones. Alternatively, the association between socio-demographic milestones and positive attitudes towards adulthood may reflect personal goal attainment: Securing a job, marrying, or having children, which may be frequent goals for adults, are likely to increase personal satisfaction and by extension, positive attitudes towards adulthood.

Attitudes towards adulthood are likely to be influenced by individual differences in other domains such as well-being, mental health, and purpose in life, which also predict the attainment of socio-demographic milestones (e.g., Morse & Steger, 2019; Stone, 2022; Whisman et al., 2007). Our results suggest that positive attitudes towards adulthood and the attainment of socio-demographic milestones are associated, but we cannot infer a direction of causality. Future research should consider confounding from variables such as mental health, well-being, and broader views of the self, and how these impact attitudes towards adulthood.

Subjective Adult Status

Subjective adult status varied by age, socio-demographic milestones, and attitudes towards adulthood. First, older participants felt more adult compared with younger participants, and age significantly predicted subjective adult status, in line with previous findings (Arnett, 2001; Mary, 2014). Our study was the first to quantify the relationship between age and self-perceived adult status, showing that age independently accounted for 11% of the variance in self-perceived adult status.

Second, participants who were employed full-time, married, and had children scored higher on the subjective adult status scale compared with those who were employed part-time or unemployed, in a relationship or single, and childfree. Parent status and relationship status significantly predicted higher subjective adult status, confirming a previous study (Zhong & Arnett, 2014).

The finding that parenthood and marriage predict subjective adult status but were not considered defining characteristics of adulthood highlights a contradiction between the perception of adulthood and the factors that influence people’s subjective adult status. Perceptions are often informed by common beliefs or stereotypes (Pirolli & Card, 2005), in our case that adults are married parents with careers. Thus, our participants may have defined adulthood using social norms or identities that are removed from their own experience. Prior studies have shown that being a member of a social group, regardless if membership is real or imagined, affects one’s self-perception (e.g., Gales & Hubner, 2020). Thus, people may perceive themselves as adult because they know themselves to be members of ‘adult’ socio-demographic groups, including married, parent, and long-term career, even though they do not consider such group memberships per se as defining characteristics of adulthood. This is supported by qualitative research, which showed that becoming a parent (i.e., achieving a markers of adulthood) enhanced individuals’ subjective adult status (Blatterer, 2007b). Of course, individuals can be adults before or without attaining traditional adult milestones, like parenthood, but the attainment of such milestones enhances subjective adulthood.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has strengths, including assessing perceptions of adulthood in a large sample with a wide age range, and the development and use of comprehensive and reliable measures of the perceptions of adulthood. Nonetheless, it is not without limitations. First, our data were cross-sectional, which prohibits testing whether participants perceive adulthood differently as they age (i.e., as people get older, they feel more adult and have more positive attitudes towards adulthood), or whether older samples perceive adulthood differently compared with younger samples (i.e., cohort effects). Future research must address whether people feel more adult and their attitudes towards adulthood become more positive as they age, or whether older generations have higher subjective adult status and more positive attitudes towards adulthood.

Second, while we found that psychological characteristics were most often endorsed to define adulthood, we did not measure the attainment of these psychological characteristics. Future research should investigate if the extent to which participants have attained psychological characteristics of adulthood predicts their subjective adult status.

Third, our findings pertain to a UK sample and thus may not be generalisable to other populations. Future research is needed to evaluate cultural differences in perceptions of adulthood. For example, young people in WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic) countries tend to spend extended periods of time in education and experiencing the identity exploration of emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2000, 2015). By comparison to WEIRD samples, young people in more developing countries, such as the Global South, tend to perceive of themselves as adults earlier and endorse the traditional socio-demographic milestones of career, marriage, and parenthood more often as defining characteristics of adulthood (e.g., Obidoa et al., 2018; Zhong & Arnett, 2014).

Conclusion

Traditionally, adulthood has been inferred from the age of majority and the attainment of socio-demographic milestones, such as long-term career, marriage, and parenthood. However, these milestones are increasingly delayed or forgone altogether for young adults today. Our findings showed that adults from the age of 18 to 77 years define adulthood using psychological characteristics such as “Accepting responsibility for the consequences of my actions” and “Being able to look after myself”. That said, subjective adult status – the extent to which people feel like adults – was predicted by marriage and parenthood, even when they were not endorsed as defining characteristics of adulthood. We conclude that there is a chasm between people’s explicit understanding of adulthood and their implicit, subjective experience of feeling adult: the factors which influence subjective adult status are not the ones considered to define adulthood. We also found that positive attitudes towards adulthood predicted subjective adult status to the same extent as chronological age. Fostering positive attitudes towards adulthood in young people is likely to improve subjective adult status, resulting in a greater sense of belonging in adulthood and increased subjective well-being.

References

Ackerman, P. L. (2022). Intelligence … moving beyond the lowest common denominator. American Psychologist, 78(3), 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001057.

Allen, M. S., Iliescu, D., & Greiff, S. (2022). Single item measures in psychological science: A call to action [Editorial]. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 38(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000699.

Arnett, J. J. (1994). Are college students adults? Their conceptions of the transition to adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 1(4), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02277582.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469.

Arnett, J. J. (2001). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood: Perspectives from adolescence through midlife. Journal of Adult Development, 8(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026450103225.

Arnett, J. J. (2015). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Axxe, E., Hayford, S. R., & Eggum, N. D. (2022). Youth’s family and non-family roles as predictors of subjective adulthood in three low-income agricultural settings. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 32(4), 1546–1565. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12731.

Bao, G., Gao, F., Xie, H., Zhang, R., & Hong, J. (2023). Links between parental autonomy support and psychological control and Chinese emerging adults’ conceptions of adulthood. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 33(3), 828–840. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12840.

Blatterer, H. (2007a). Adulthood: The contemporary redefinition of a social category. Sociological Research Online, 12(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.1563.

Blatterer, H. (2007b). Coming of age in Times of uncertainty. Berghahn Books.

Bolton, P. (2012). Education: Historical statistics. House of Commons Libraryhttps://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN04252/SN04252.pdf.

Cambridge Dictionary (2023). Convoy. In Cambridge Dictionary, Cambridge University Press, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/convoy.

Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54(3), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.165.

Churchill, S., Munyanyi, M. E., Prakash, K., & Smyth, R. (2020). Locus of control and the gender gap in mental health. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 178, 740–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2020.08.013.

Clark, D. (2023). Average age of mothers in the UK 1938–2021. Statistahttps://www.statista.com/statistics/294590/average-age-of-mothers-uk/#:~:text=Average%20age%20of%20mothers%20in%20the%20UK%201938%2D2021&text=Between%201991%20and%202021%20there,1991%20to%2030.9%20by%202021.

Cobb-Clark, D. A., Kassenboehmer, S. C., & Schurer, S. (2014). Healthy habits: The connection between diet, exercise, and locus of control. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 98, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2013.10.011.

R Core Team (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL: https://www.R-project.org/.

Department for Education (2023). Participation measures in higher education. UK Government. https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/participation-measures-in-higher-education.

Erikson, E. H. (1963). Childhood and society (2nd Ed.). Norton.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lange, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146.

Gales, A., & Hubner, S. V. (2020). Perceptions of the self versus one’s own social group: (Mis)conceptions of older women’s interest in and competence with technology. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 848. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00848.

Grühn, D. (2016). An English word database of EMOtional TErms (EMOTE). Psychological Reports, 119(1), 290–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294116658474.

Havighurst, R. J. (1953). Human development and education. Longmans.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X.

Ingrand, I., Paccalin, M., Liuu, E., Gil, R., & Ingrand, P. (2018). Positive perception of aging is a key predictor of quality-of-life in aging people. Plos One, 13(10), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204044.

Jenull, B., Mayer, C., Awenius, L., Bostjancic, G., Kollitsch, K., & Knobel, P. (2023). Accepting the aging body: Protective factors of body acceptance in persons of advanced age. Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine, 9, 23337214221150067. https://doi.org/10.1177/23337214221150067.

Kuang, J., Zhong, J., Arnett, J. J., Hall, D. L., Chen, E., Markwart, M., Yeung, A., & Zou, L. (2023). Conceptions of adulthood among Chinese emerging adults. Journal of Adult Development. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-023-09449-4.

Lachman, M. E. (2004). Development in midlife. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 305–331. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141521.

Lyons, S. T., Schweitzer, L., & Ng, E. S. W. (2015). How have careers changed? An investigation of changing career patterns across four generations. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30(1), 8–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-07-2014-0210.

Mary, A. (2014). Re-evaluating the concept of adulthood and the framework of transition. Journal of Youth Studies, 17(3), 415–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.853872.

Mehta, C. M., Arnett, J. J., Palmer, C. G., & Nelson, L. J. (2020). Established adulthood: A new conception of ages 30 to 45. American Psychologist, 75(4), 431–444. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000600.

Molgat, M. (2007). Do transitions and social structures matter? How ‘emerging adults’ define themselves as adults. Journal of Youth Studies, 10(5), 495–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260701580769.

Morse, J. L., & Steger, M. F. (2019). Giving birth to meaning: Understanding parenthood through the psychology of meaning in life. In O. Taubman-Ben-Ari (Ed.), Pathways and barriers to parenthood (pp. 1–17). Springer.

Norman, K. B., Grahe, J. E., & Lee, S. (2021). Reconstructing adulthood: Revising the markers of adulthood scale for increased ecological validity. Psychological Reports, 126(2), 1042–1061. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941211061700.

Obidoa, C. A., Dodor, B. A., Tackie-ofosu, V., Obidoa, M. A., Kalisch, H. R., & Nelson, L. J. (2018). Perspectives on markers of adulthood among emerging adults in Ghana and Nigeria. Emerging Adulthood, 7, 270–278.

ONS (2022). Births in England and Wales: 2021. Office for National Statisticshttps://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/bulletins/birthsummarytablesenglandandwales/2021#live-births-and-fertility-rates.

ONS (2012). Marriages in England and Wales: 2010. Office for National Statisticshttps://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/marriagecohabitationandcivilpartnerships/bulletins/marriagesinenglandandwalesprovisional/2012-02-29#:~:text=For%20grooms%2 C%20the%20mean%20age,the%20increasing%20number%20of%20remarriages.

Pirolli, P., & Card S. (2005). The sensemaking process and leverage points for analyst technology as identified through cognitive task analysis. Proceedings of International Conference on Intelligence Analysis U.S.A. 5 2–4.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (2013). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. In A.D. Fave (Ed.), The Exploration of Happiness: Present and Future Perspectives (pp. 97–116). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5702-8_6.

Schneider, S., Losch, T., Schneider, D., & Schutz, A. (2022). How self-concept, competence, and their fit or misfit predict educational achievement, well-being, and social relationships in the school context. Collabra: Psychology, 8(1), 37154. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.37154.

Schönbrodt, F. D., & Perugini, M. (2013). At what sample size do correlations stabilize? Journal of Research in Personality, 47(5), 609–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.05.009.

Sehmi, R., Maughan, B., Matthews, T., & Arseneault, L. (2020). No man is an island: Social resources, stress and mental health at mid-life. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 217(5), 638–644. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.25.

Settersten, R. A. (2007). Passages to adulthood: Linking demographic change and human development. European Journal of Population, 23, 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-007-9132-8.

Sharon, T. (2016). Constructing adulthood: Markers of adulthood and well-being among emerging adults. Emerging Adulthood, 4(3), 161–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696815579826.

Sirsch, U., Dreher, E., Mayr, E., & Willinger, U. (2009). What does it take to be an adult in Austria? Views of adulthood in Austrian adolescents, emerging adults, and adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 24(3), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558408331184.

Stone, L. (2022). Does getting married really make you happier? Institute for Family Studies. https://ifstudies.org/blog/does-getting-married-really-make-you-happier#:~:text=Indeed%2 C%20married%20people%20are%20happier,and%2015%25%20for%20people%20who.

Stripe, N. (2019). Married by 30? You’re now in the minority. Office for National Statisticshttps://blog.ons.gov.uk/2019/04/01/married-by-30-youre-now-in-the-minority/.

Sullivan-Singh, S. J., Stanton, A. L., & Low, C. A. (2015). Living with limited time: Socioemotional selectivity theory in the context of health adversity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(6), 900–916. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039047.

Waterman, A. S., Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Ravert, R. D., Williams, M. K., Agocha, V. B., Kim, S. Y., & Donnellan, M. B. (2010). The questionnaire for eudaimonic well-being: Psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(1), 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903435208.

Watson, B. (2023). Employment, unemployment and economic activity for people aged 16 and over and aged from 16 to 64. Office for National Statisticshttps://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/datasets/employmentunemploymentandeconomicinactivityforpeopleaged16andoverandagedfrom16to64seasonallyadjusteda02sa.

Wettstein, M., & Wahl, H. W. (2021). Trajectories of attitude toward own aging and subjective age from 2008 to 2020 among middle-aged and older adults: Partial evidence of a COVID-19 effect. Psychology and Aging, 36(7), 790–805. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000645.

Whisman, M. A., Tolejko, N., & Chatav, Y. (2007). Social consequences of personality disorders: Probability and timing of marriage and probability of marital disruption. Journal of Personality Disorders, 21(6), 690–695. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2007.21.6.690.

Wright, M., & von Stumm, S. (2023a). The CARES taxonomy: Five psychological qualities of adulthood. [Under Review].

Wright, M., & von Stumm, S. (2023b, May 28). The CARES taxonomy: Five psychological qualities of adulthood [Conference presentation]. APS 2023 Convention, Washington, D.C., United States.

Wrzus, C., Hänel, M., Wagner, J., & Neyer, F. J. (2013). Social network changes and life events across the life span: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 53–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028601.

Wurm, S., Diehl, M., Kornadt, A. E., Westerhof, G. J., & Wahl, H. W. (2017). How do views on aging affect health outcomes in adulthood and late life? Explanations for an established connection. Developmental Review, 46, 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2017.08.002.

Zhong, J., & Arnett, J. J. (2014). Conceptions of adulthood among migrant women workers in China. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38(3), 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025413515133.

Acknowledgements

We thank Anna Brown, Alexandra Starr, Kirsty Wilding, and Florence Oxley for their invaluable comments on earlier drafts of this work.

Funding

MW is recipient of a PhD stipend from Hogan Assessments. SvS was supported by a CRISP Fellowship from the Jacobs Foundation (2022–2027), a British Academy Mid-career Fellowship (2022–2023), and Fellowship from the Institute d’etudes advancees de Paris (2023–2024) during the writing of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wright, M., von Stumm, S. Perceptions of Adulthood: What Does it Mean to be Grown-Up?. J Adult Dev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-024-09477-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-024-09477-8