Abstract

Many parents cope with the prolonged financial dependence of their emerging adult children and problems arising from sharing a household, which may challenge parental satisfaction with money management (SMM) and life satisfaction (LS). We created and tested a conceptual model of potential pathways to parental SMM and LS. Data were collected in a sample of 482 student–parent pairs via an online survey that included adjusted questionnaires on financial functioning (Shim et al., Journal of Youth and Adolescence 39:1457–1470, 2010) and Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., Journal of Personality Assessment 49:71–75, 1985). Relying on the model of financial satisfaction from the student perspective (Sirsch et al., Emerging Adulthood 8:509–520, 2020), we proposed pathways of the family SES, financial parenting (explicit teaching and financial behavior; parent report; 22.8% fathers), and parent–child financial relationships (student report; Mage = 19.94; 45.2% males) to parental SMM and LS. We also anticipated intermediate relations of financial parenting with the students' self-reported financial learning outcomes (cognitive and behavioral/relational). The SES, proactive parental financial behavior, and favorable parent–child financial relationships predicted parental SMM and LS. Financial parenting was linked to the student's positive financial learning outcomes, but only financial knowledge further influenced the financial relationship with their parents. The findings suggest the benefits of successful parental financial socialization for both the offspring's finance-related outcomes and their parents' satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Young people in contemporary (post)modern societies become economically independent from their family of origin at considerably later ages than in the past. Over the last few decades, a postponement of leaving the parental home and reliance on various kinds of parental support (e.g., financial, emotional, instrumental) has been noticed (Descartes, 2006; Fingerman et al., 2012; Fry, 2013; Serido et al., 2015; see also Žukauskiene, ed., 2016). In Europe, this is particularly evident in countries with strong family support systems, characteristic of the Mediterranean region (e.g., Arnett, 2016; Douglass, 2007; Mendonça & Fontaine, 2013), including Slovenia (Kuhar & Reiter, 2014; Zupančič & Sirsch, 2018). Still, in conceptions of emerging adults (ages 18–29) and adults across different countries, achieving financial independence remains one of the most important criteria for adulthood (e.g., Arnett, 2014, 2016; Zupančič & Sirsch, 2018).

As the duration of establishing economic independence from parents has extended, research on emerging adults’ development toward financial self-sufficiency and well-being has accumulated (Sorgente & Lanz, 2017). Mainly within the framework of the family financial socialization theory (FFST, Gudmunson & Danes, 2011), abundant research has provided valuable evidence of the importance of parental financial socialization for emerging adults’ positive outcomes in the financial domain (most recently, e.g., LeBaron-Black et al., 2022a; Pak et al., 2023), as well as across other central domains of their life (e.g., LeBaron-Black et al., 2022b, 2023; Mahapatra et al., 2023). Nevertheless, the questions of how emerging adults' parents manage their family finances in the light of providing continual economic support to their children, and of parental financial satisfaction and subjective well-being have been set aside. To address this gap, we focused on parental satisfaction with money management (SMM) and life satisfaction by accounting for financial parenting and children's financial learning outcomes, including parent–child financial relationships. In this way, we embedded the extant knowledge of the role of the family financial context in emerging adults' financial development into the model predicting aspects of their parents' subjective well-being. The strength of our study was also the inclusion of data from both parents and their children. The prevailing research on family financial socialization, financial functioning, and well-being of emerging adults has thus far relied on their reports only.

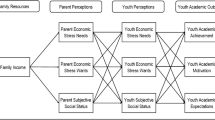

Specifically, we conceptualized a model of pathways that relates family financial conditions, financial parenting, and financial learning outcomes in emerging adults to parental SMM and satisfaction with life. In creating the model (Fig. 1) with two interrelated outcome measures, we first considered the links of the family SES and parents' self-rated financial behavior to their SMM and life satisfaction. Then, we introduced pathways of financial parenting to children's perceptions of their financial relationships with parents (based on the FFST and research), which we proposed to further shape parental SMM and life satisfaction. We tested the model on Slovenian first-year university students and their parents. In general, strong parental economic and social–emotional assistance to emerging adults is typical in Slovenia (Kuhar & Hlebec, 2019; Kuhar & Reiter, 2014), as well as late leaving of parental home (on average at the age of 27.7 years). Two-thirds of 19-to-24-olds permanently co-reside, and a quarter of the others semi-reside with parents; a vast majority of all also expect parental financial support in the future (Lahe et al., 2021). About half of this age population continues their education on a tertiary level, predominantly at one of Slovenia's tuition-free public institutions (SURS, 2022).

Satisfaction with Life and Financial Satisfaction in Parents of Emerging Adults

According to Diener (2000; Pavot & Diener, 1993), satisfaction with life is a constituent of subjective well-being (or happiness) and refers to an overall cognitive evaluation of one’s quality of life. It depends on many factors, such as personality dispositions, values (e.g., materialism; Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2002; Sirgy, 2012), and judgments of subjectively important domains of life—domain-specific satisfaction (e.g., Pavot & Diener, 2008; Schmidt et al., 2023; Tiefenbach & Kohlbacher, 2015). One of the domains pertains to financial satisfaction, which represents the subjective part of financial well-being (Shi et al., 2021; Shim et al., 2009; Xiao et al., 2009) and reflects individuals' evaluations of their financial situation experiences. It includes various aspects (Sorgente & Lanz, 2017), such as income satisfaction, satisfaction with financial status, satisfaction with living standard, and satisfaction with money management (SMM; Sorgente & Lanz, 2019). We referred to parental SMM in our study because parents are mainly responsible for the management of family finances and offer substantial economic support (residential and financial) to their emerging adult children, particularly to those in education (Sirsch et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2014).

The research underlines the importance of financial satisfaction (regardless of the specific aspect) in explaining satisfaction with life in emerging adults (Iannello et al., 2020; Shim et al., 2009; Xiao et al., 2009) and adults (Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2002; Nettemeyer et al., 2018; Seghieri et al., 2006). These findings may imply that financial satisfaction influences life satisfaction in a bottom-up fashion, but it has also been suggested the other way around (Pavot & Diener, 2008; Rojas, 2007). As we were interested in two different (though related) outcomes irrespective of the nature of their relationship (top-down or bottom-up), we simply contended (H1.1) a positive relationship between parents' SMM and their life satisfaction.

Positive relations of financial conditions (or SES) with both financial well-being (Di Domenico et al., 2022; Hsieh, 2003, 2004; Shim et al., 2010; Xiao et al., 2014) and life satisfaction (Diener, 2000; Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2002; Tay et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2009) have been well documented for emerging adults and adults, though not specifically for parents of (at least partly) economically dependent emerging adult children. Yet, these associations are not strong as they depend not only on the available financial resources but also on their appropriate use and subjective appraisals (Martin & Westerhof, 2003), individuals' goals and values, and culture (Diener & Oishi, 2000). The associations further hold up only to a certain amount of financial wealth (Diener, 2000; Seghieri et al., 2006) and vary in strength depending on the measures employed (e.g., personal income, household income, level of debt; Di Domenico et al., 2022; Hsieh, 2003). As parents in Slovenia—the country under study—are generally not comfortable with providing information on their income (Sirsch et al., 2020), and because of low economic disparity in Slovenia (OECD, 2023), we opted for a measure of SES that combines parental level of education, employment status, and subjective social comparison ratings of the family financial situation (Sirsch et al., 2020). We proposed (H1.2) that higher SES would predict both parents’ SMM and their satisfaction with life.

Drawing from the field of happiness research, Xiao et al. (2009) applied the argument that performing domain-specific behaviors predicts domain-specific satisfaction in the financial domain. These authors showed that college students' positive financial behavior (expense management, balance control, and saving) increased their satisfaction with their financial status, which contributed to their life satisfaction. Abundant studies have further demonstrated that behavioral expressions of financial capability—desirable preventive and proactive financial behaviors (e.g., spending within the budget and money saving, respectively)—in emerging adults and adults associate with financial satisfaction (Aboagye & Jung, 2018; Shim et al., 2009, 2012; Sirsch et al., 2020; Xiao & O’Neill, 2018; Xiao et al., 2014; Zupančič et al., 2023), while overspending and borrowing show negative associations (Aboagye & Jung, 2018; Chalise & Anong, 2017; Fan & Chatterjee, 2017). Moreover, responsible financial behaviors may have direct or mediated effect (through financial satisfaction) on satisfaction with life and subjective well-being (Li et al., 2020; Serido et al., 2010; Shim et al., 2009; Xiao et al., 2009). In the present study, we focused on proactive financial behavior that is highly valued and salient in Slovenian society (Lep et al., 2022). In line with extant findings, we assumed that (H1.3) proactive financial behavior performed by parents would predict both their SMM and life satisfaction.

Parent–Child Financial Relationships

Within the framework of the FFST (Gudmunson & Danes, 2011), financial learning primarily unfolds through parent–child interactions and relationships. Research offered substantial support to the influence of these interactions (e.g., general communication patterns, financial communication) and parent–child relationships (e.g., relationship quality, quality of attachment) on emerging adults' financial learning outcomes, such as financial knowledge, attitudes and behavior (e.g., Jorgensen et al., 2017; Kim & Torquati, 2020; Shim et al., 2015), and financial well-being (e.g., Lanz et al., 2020; Serido et al., 2010). Scarce studies also evidenced the other way around, i.e., healthy cognitive and attitudinal outcomes of financial socialization further predict favorable emerging adult students' perceptions of their financial relationship with parents (Shim et al., 2010) and good parent–child financial relationships promote the students' SMM (Sirsch et al., 2020). In general, the relational outcomes of parental financial socialization (financial relationships) and their role in aspects of subjective well-being have been understudied. Given that most emerging adults depend on parents financially and residentially, parent–child financial disagreements and conflicts (or agreements and concord) may strain (or ease) parental management of the family budget and likely affect parental SMM. Therefore, lower levels of stress and conflict related to money and spending within parent–child relationships may play a positive role in parental SMM.

Close social relationships are an important domain of life satisfaction (e.g., Argyle, 2001; Headey & Wearing, 1992; Rojas, 2007). Their quality contributes to subjective well-being across age groups (Chopik, 2017; Schmidt et al., 2023; Ward, 2008). Among various close relationships, parent–child relationships are central for both parents and children (Bengtson et al., 2002) and may be even more vital for parental than children's life satisfaction when the children reach emerging adulthood (Hong et al., 2021; Rossi & Rossi, 1990). While young people strive for a balance between autonomy and relatedness to parents, form their identities and take on the way toward economic independence (Arnett, 2014; Kins et al., 2012; Komidar et al., 2014), generativity concerns (Erikson, 1963), evaluations of parental investment (Ryff et al., 1996), and importance of close relationships (Carstensen et al., 1999) become more prominent in their middle-aged parents.

In emerging adulthood, parent–child relationships undergo a significant restructuring toward more symmetrical ones, i.e., the relationships between equal adults (Arnett, 2014; Komidar et al., 2014; Tanner, 2006). As many emerging adults rely on parental economic support, financial matters become more salient in renegotiating parent–child relationships, and tensions over financial issues between parents and children are more likely to arise. These challenges may influence the quality of parent–child relationships, which is crucial in parental life satisfaction (e.g., Hong et al., 2021; Ward, 2008). Precisely, frequent financial conflicts may undermine the relationships and deteriorate not only parental SMM but also parental life satisfaction. In contrast, more positive relationships due to financial matters may bolster parental SMM and spill over to their life satisfaction. We thus hypothesized (H1.4) that emerging adults' favorable perceptions of their financial relationship with parents predict both parental SMM and life satisfaction.

Financial Parenting and Emerging Adult Children’s Financial Learning Outcomes

In conceptualizing the pathways of financial parenting to parent–child financial relationships (Fig. 1), we specifically relied on the hierarchical model by Shim et al. (2010) and its adaptation to the European context (Sirsch et al., 2020). Both models draw on the consumer socialization theory (Moschis, 1987) and the FFST (Gudmunson & Danes, 2011), which contend that individuals learn consumer/financial skills through interactions with socialization agents, primarily with parents. Both hierarchical models were empirically substantiated in self-report studies of emerging adult students (Shim et al., 2010; Sirsch et al., 2020), suggesting that positive financial parenting predicts beneficial cognitive financial learning outcomes and that these further favorably influence behavioral and relational outcomes (i.e., parent–child relationships) in the financial domain. We adopted several of these pathways in the present study. To control for the same-informant bias, we linked parents' recollections of the extent to which they provided financial instructions to their children and parents' self-reports on their current financial behavior to the children's self-perceived cognitive financial learning outcomes, i.e., financial knowledge and adopting parental financial role modeling.

Adopting parental financial role modeling refers to children's enactment of the observed parental financial behavior, including internalization of what has been observed or explicitly taught (Lanz et al., 2020) and thoughtful readiness to perform the modeled/imparted behavior. Emerging adults' perceptions of responsible parental financial behavior and higher levels of delivered parental financial lessons were found to enhance the children’s tendency to adopt behaviors modeled and taught by parents (Shim et al., 2010; Sirsch et al., 2020). Likewise, parental engagement in financial teaching positively influenced emerging adults' financial knowledge, measured as either a combination of subjective and objective knowledge (Shim et al., 2010) or self-perceived financial understanding (i.e., subjective knowledge; Sirsch et al., 2020). We opted for the latter because it notably relates to objective financial knowledge and reflects one's financial self-efficacy and self-confidence (Shim et al., 2010). Subjective financial knowledge further shows stronger associations with attitudinal and behavioral financial outcomes and financial satisfaction than solely understanding objective financial facts (e.g., Shim et al., 2010; Xiao et al., 2014). We thus contended that (H2.1) parent-self-reported proactive financial behavior and prior engagement in financial teaching predict emerging adults' adopting parental financial role modeling and that (H2.2) parent-recollected financial teaching predicts emerging adults' subjective financial knowledge.

The hierarchical models of financial socialization (Shim et al., 2010; Sirsch et al., 2020) propose that adopting parental financial role modeling and financial knowledge further influence emerging adults' behavioral financial learning outcomes and financial relationships with parents. Adopting parental role modeling tends to prevent parent–child disputes over financial matters directly (Sirsch et al., 2020), promotes responsible financial behavior, and favorably shapes financial relationships with parents through better self-control, compliance with parental financial expectations in constructive ways, and maintenance of positive attitudes toward performance of desirable financial behaviors (Shim et al., 2010, 2015; Sirsch et al., 2020). Other studies have also suggested that greater levels of financial knowledge (objective or subjective) are related to healthier financial behaviors (Hilgert et al., 2003; Hira, 2012; Robb, 2014; Totenhagen et al., 2019; Xiao et al., 2011). Accordingly, we anticipated that adopting parental role modeling (H2.3) and emerging adults' subjective financial knowledge (H2.4) predict both their self-perceived proactive financial behavior and positive financial relationships with parents.

Responsible financial behaviors of young people (e.g., keeping track of monthly expenses, spending with the budget, and saving regularly) have consistently demonstrated associations with many positive outcomes, such as financial satisfaction (Sirsch et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2014; Zupančič et al., 2023), academic success (Xiao et al., 2009), and subjective well-being (Serido et al., 2010), as well as relational happiness and satisfaction in romantic relationships (Dew & Xiao, 2013; LeBaron-Black et al., 2023; Li et al., 2020). Given significant changes in parent–child relationships during emerging adulthood (Tanner, 2006), the way emerging adults manage their finances may have a vital influence on the restructuration of these relationships, especially when young people co-reside or semi-reside in the parental home and rely on parental financial support. By analogy with marital/committed relationships (Curran et al., 2018; Dew, 2011; Dew & Stewart, 2012), financial issues between parents and emerging adult children are likely to create interpersonal conflict and may represent social power and control issues, which worsens their relationship. In contrast, children's engagement in responsible money management may improve the parent–child relationships by meeting parental expectations regarding money matters, preventing family budget difficulties and hostile interactions due to financial concerns. We thus proposed that (H2.5) emerging adults’ self-perceived proactive financial behavior predicts better financial relationships with their parents.

The Current Study

This study aimed to fill the gap in the literature on family financial socialization in emerging adulthood by focusing on parental outcomes and avenues of financial parenting toward these outcomes. We considered parent–child financial relationships as an important relational outcome of parental financial socialization that has been (as such) understudied in the respective scholarship and proposed its significant role in the aspects of parental satisfaction. We further considered a limitation of predominant research in this realm that was based on same-informant data sources by combining parent and child reports in a single model. Specifically, we aimed to examine the model (Fig. 1) that connects family SES, parent-perceived financial parenting, and child-perceived financial relationships with parents to parental SMM and life satisfaction. We also considered transitional links of financial parenting to the child-perceived financial learning outcomes (cognitive first and behavioral/relational next) in the model. Finally, we aimed to simultaneously evaluate the power of the predictors on the two parental outcomes.

In sum, we set the following hypotheses:

H 1.1

Parental SMM and life satisfaction would be positively associated.

H 1.2

Higher family SES would predict both parental SMM and life satisfaction.

H 1.3

Engagement of parents in proactive financial behavior would predict their SMM and life satisfaction.

H 1.4

Children's favorable perceptions of parent–child financial relationships would predict both parental SMM and life satisfaction.

H 2.1

The engagement of parents in both proactive financial behavior and financial teaching would predict their children's adopting parental role modeling.

H 2.2

The engagement of parents in financial teaching would predict their children's subjective financial knowledge.

H 2.3

Adopting parental financial role modeling would predict both children's proactive financial behavior and positive financial relationships with parents.

H 2.4

Children's subjective financial knowledge would predict both their proactive financial behavior and positive financial relationships with their parents.

H 2.5

Children’s engagement in proactive financial behavior would predict their positive financial relationships with their parents.

Method

Participants

Our sample included 482 parent–child pairs residing in Slovenia. The participating parents (77.2% mothers and 22.8% fathers) had a mean age of 47.98 years (SD = 4.85). About two-thirds (65.1%) had a secondary education (high school, technical, or professional), 29.3% obtained postsecondary education (college or university), and 5.6% completed only eight years of obligatory schooling. Most parents (84.3%) were employed full-time, 5.2% were employed part-time, and 10.5% were unemployed or retired (pension beneficiaries). A vast majority (92.0%) of the participants lived with a partner (were married or cohabited), and 8.0% lived without a partner (were divorced, widowed, or never married/cohabited). Slightly more than half of the parents (55.6%) had two children, 22.4% had three children, 15.04% had one child, and 6.9% had more than three children.

The participating children were first-year university students (45.2% males and 54.8% females). Their mean age was 19.94 years (SD = 0.79) and was comparable to the age structure of first-year university students in Slovenia (SURS, 2022). The participants attended one of two (out of three) Slovenian public universities and were enrolled in one of the social sciences programs (62.0%), technical/nature sciences programs (27.1%), humanities (7.2%), or other programs (3.8%). About half of the students (53.9%) partly resided in parental home (during the weekends and semester holidays), 44.1% of them co-resided with parents, and the remaining ones (2.0%) lived with other relatives, in one's own, or partner’s home. Of the participating students, 96.8% responded positively to the question Do your parents provide the level of financial support you believe they should?

Procedure and Measures

We collected the data within an international research collaboration initiated by prof. Mihaela Friedlmeier (Grand Valley State University, Allendale, MI), who attained institutional board approval for the study on the role of parents, work, and personal values in the financial socialization of emerging adults. We contacted psychology first-year students and first-year students in educational study programs in their classrooms. We invited them to participate voluntarily and anonymously and to ask one of their parents, an additional first-year student of a different study program, and one of additional student’s parents to participate. We provided the students with links to an online application with separate forms for student and parent respondents. The application included instructions, an informed consent form, and a battery of questionnaires. The participants entered a unique code assigned to each student–parent pair, enabling us to link their responses. The students were offered course credit for their own and their parent's participation (completely filled-in questionnaires were required).

Along with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985), the survey contained self-report questions and scales based on Shim et al.'s measures referring to financial socialization and financial functioning (2010), which were slightly adjusted and validated for use in the Central European context (Sirsch et al., 2020). We tested each measure using confirmatory factor analysis to validate the measures in the present study (see Supplemental file 1 for the results). We then tested a measurement model with all the scales using MLR estimator. The model fit data well (χ2 = 297.81, df = 188, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.037, 90% CI [0.029, 0.045], SRMR = 0.040), and composite reliability scores ranged between ω = 0.69 and ω = 0.83. For detailed results, including full item wordings, see Supplemental file 1.

Both the participating parents and their emerging adult child independently offered self-reports on their current financial behavior. The two-item scale (rparents = 0.71, rstudents = 0.71) refers to one's engagement in proactive financial behaviors (saving each month, investing for long-term goals), and the participants indicated on a five-point rating scale how often they performed each of these behaviors (1—never; 5—very often).

The participating parents filled in three additional scales and responded to questions we used to create a combined measure of their family SES.

Direct parental financial teaching (four items, ɑ = 0.70) applies to the extent to which parents engaged in four teaching methods of financial management while raising the participating child (discussing financial family matters, speaking about the importance of saving, teaching about smart shopping, and responding to questions). The parents were asked to respond along a five-point scale (1—strongly disagree; 5—strongly agree).

Satisfaction with money management was assessed by three items (ɑ = 0.74) asking about the extent to which the parent is currently satisfied with paying bills, managing purchases, and worries about money (reverse coded). The participants indicated their agreement with each item on a five-point scale (1—strongly disagree; 5—strongly agree).

Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985) is a five-item scale (e.g., The conditions of my life are excellent) to assess global satisfaction with life (ɑ = 0.84). The parents responded to each item using a five-point rating scale (1—strongly disagree; 5—strongly agree).

The SES measure was determined by average standardized scores for the level of education and employment status (not employed, employed part-time/retired, employed full-time) of both parents and subjective financial status (i.e., Compared to others in this country, what economic status do you consider your family to have? Where would you put your family on this scale?) rated by the participating parent on a five-point scale – low, lower middle, middle, upper middle, or upper). First, we cross-tabbed the levels of education and employment status of both parents to obtain two 6-point vectors. For education level, the vector comprised the following levels: primary level for both parents, primary level for one and secondary for the other parent, primary for one and postsecondary for the other parent, secondary level for both parents, secondary level for one parent and postsecondary for the other, postsecondary level for both parents. For employment, the levels were as follows: both parents unemployed, one parent employed part-time/retired and the other unemployed, one parent employed full-time and the other unemployed, both parents employed part-time/retired, one parent employed part-time/retired and the other full-time, and both parents employed full-time. Then, these two vectors and the subjective financial status scores were standardized and averaged into a single indicator.

The students additionally rated their financial knowledge and filled in two finance-related scales (Shim et al., 2010; adjusted by Sirsch et al., 2020).

Subjective financial knowledge was measured using a single item (i.e., How would you rate your overall understanding of money management?), asking the students to respond on a five-point scale (1—very low; 5—very high).

Adopting parental role modeling captures three items (ɑ = 0.73) that ask about the extent to which individuals adopt the financial role of their parent at present (i.e., making financial decisions based on what the parent has done in similar situations, looking at the parent as a role model in managing money, and acknowledging the parent as the best financial advisor). The students expressed their agreement with each item on a five-point scale (1—strongly disagree; 5—strongly agree) by referring to the participating parent (mother or father).

The parent–child financial relationship contains three items (ɑ = 0.78) about the extent to which the students experience conflict and stress in their relationship with the participating parent due to financial matters (reverse coded). The items were rated on a five-point scale (1—strongly disagree; 5—strongly agree).

Data Analysis

After establishing the construct validity of the scales and testing the measurement model (see Procedure and Measures and Supplemental file 1, Table S1), we proceeded to test the proposed structural model. We first observed the covariation matrix of the latent variables, which suggested that the testing of a structural equation model was warranted. Moreover, since all the variables can be considered interval and because we assumed linear relationships, we proceeded with testing the proposed SEM model. The analyses were conducted in R, using the package lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) and robust maximum likelihood estimator to account for deviations in the distribution of some variables from normality.

The maximum number of missing values per variable was 4 (0.8%) for SES, but most variables (60.8%) had no missing data. Missing values were imputed using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method. We set the cut-off points for a good fit at RMSEA ≤ 0.06, SRMR ≤ 0.05, and CFI and TLI ≥ 0.95 (Hooper et al., 2008; Marsh et al., 2004). In the model, we tested the direct pathways presented in Fig. 1 and estimated all the indirect effects (see Table S6 in Supplemental file 1) using the package lavaan (MLR estimator, bootstrapped p values). The residuals between parents and students were not estimated (set to zero). No modifications were applied to the model.

Results

The model had good fit to the data (χ2 = 372.60, df = 238, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.036, 90% CI [0.029, 0.043], SRMR = 0.050) and no subsequent modifications were applied. We present standardized regression coefficients and shares of explained variance for the structural model in Fig. 2, and the full SEM model in Supplemental file 1.

Structural model of parental life satisfaction and satisfaction with money management and shares of explained variance for the endogenous variables. All coefficients are standardized. Variables presented in gray were reported by the parent and those in white by their emerging adult child. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Parental Outcomes

As predicted (H1.1), both parental outcomes were significantly correlated (r = 0.46, p < 0.001). While the model explained a notable share of variance in the SMM score (R2 = 0.36), the share was modest for parental life satisfaction (R2 = 0.17). In line with our expectations, higher family SES scores (H1.2), greater parental engagement in proactive financial behavior (H1.3), and more favorable parent–child financial relationships as assessed by the emerging adults (H1.4) all contributed positively to parental life satisfaction and SMM. Most notable in terms of the effect size were the contributions of proactive financial behavior to both SMM (β = 0.48, p < 0.001) and life satisfaction (β = 0.29, p < 0.001) and of the SES to the participating parents' SMM (β = 0.30, p < 0.001).

Children’s Outcomes

Consistent with our second hypothesis, parental proactive financial behavior and financial teaching were predictive of higher levels of adopting parental financial role modeling in emerging adults (H2.1), while higher levels of financial teaching were also predictive of the children's greater subjective financial knowledge (H2.2). Contrary to our expectations, levels of adoption of the participating parent as the financial role model did not influence the children's perceptions of their financial relationship with the parent (H2.3), but it was predictive of slightly more frequent children's self-reported engagement in proactive financial behavior (H2.3; β = 0.12, p = 0.04). When testing for indirect effects, we observed (marginally) significant—yet close to negligible—mediating effects of subjective financial knowledge between direct parental financial teaching and both proactive financial behaviors of students (β = 0.06, p = 0.019) and parent–child financial relationships (β = − 0.02, p = 0.048). All the other indirect effects were non-significant (see Table S6 in Supplemental file).

The Contribution of Children to Parental Outcomes

Considering how children's financial socialization outcomes contribute to parental life satisfaction and satisfaction with money management, we observed that better subjective financial knowledge (H2.4) was linked with significantly more proactive financial behaviors (β = 0.38, p < 0.001) and a somewhat more favorable parent–child financial relationship (β = 0.14, p = 0.01). Contrary to our expectations (H2.5), proactive financial behavior of children was not related to a better parent–child financial relationship.

To examine whether the predictors of life satisfaction and SMM had significantly different contribution to each of the outcome variables, we tested for their structural equivalence. For each predictor, we constrained the two regression paths (to life satisfaction and to SMM) to be equal and compared the change in model fit to the unconstrained model.

For SES and student-assessed parent–child financial relationship, the regression paths did not differ significantly (Δχ2 = 0.80, Δdf = 1, p = 0.373 and Δχ2 = 0.94, Δdf = 1, p = 0.334, respectively), while for parental proactive financial behavior, the regression coefficient was significantly higher for predicting SMM than for predicting life satisfaction (Δχ2 = 7.00, Δdf = 1, p = 0.008).

Discussion

The importance of family financial socialization for financial functioning and well-being of emerging adults has been well documented (e.g., Jorgensen et al., 2017; Lanz et al., 2020; LeBaron-Black et al., 2022a; Serido et al., 2010), but financial management and well-being of their parents have been overlooked. An insight into parental financial life and satisfaction could contribute to a better understanding of financial development within the family because parents still provide economic support to their emerging adult children. This support likely presents a prolonged financial pressure for parents (Zupančič et al., 2023), which affects the family system, as well as its individual members. The support may slow the renegotiation of parent–child relationships (Tanner, 2006), challenge the family's financial situation longer than expected, and interfere with parental financial goals and future life plans. Given that many (if not most) parents of emerging adults are employed, their financial overload and low levels of overall well-being can also harm their health and productivity at work, as noted by Nettemeyer et al. (2018).

This study began to address emerging adults' parents by shedding light on their evaluation of money management (i.e., SMM) and their lives as a whole. Using a two-generational sample of Slovenian first-year university students and one of their parents, we evidenced that a higher family SES, greater parental engagement in proactive financial behavior, and a better quality of parent–child financial relationships promote both parental life satisfaction and SMM.

The Role of the Family SES and Parental Financial Behavior

In line with consistent findings, our research adds support to the generalizability of the associations of SES with financial well-being (e.g., Di Domenico et al., 2022; Hsieh, 2003; Xiao et al., 2014) and life satisfaction (Diener, 2000; Tay et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2009), as well as of positive financial behavior with both outcomes (Aboagye & Jung, 2018; Xiao & O’Neill, 2018; Xiao et al., 2014). We maintained these associations (supporting H1.2 and H1.3, respectively)—and observed a positive correlation between the two final outcomes (supporting H1.1)—using a sample of parents of 1st-year university students in a country with one of the lowest income inequality ratings in the world (OECD, 2023) and applying a distinct measure of the SES (i.e., combined objective and subjective proxies of the family economic wealth, disregarding the household income). We also relied on a specific type of future-oriented financial behavior and predicted a specific (behavioral) component of financial satisfaction (Sorgente & Lanz, 2019). However, the predictive relations obtained (especially of parental behavior to SMM/life satisfaction) may have been somewhat overestimated due to the same-informant bias. An examination of a multi-group model with the bottom half vs. the top half of the family SES could contribute to the literature, as one of the reviewers suggested. Although we did not follow the proposal due to the low economic disparity in Slovenia, we recommend this initiative for research in countries with greater social-class differences.

Whereas the availability of financial resources (indexed by the family SES) among the participating parents notably contributed to their evaluations of money management and life in general, their (self-reported) performance of behavior aimed at attaining future financial goals seems to play a stronger role in predicting SMM. These findings add to the notion that domain-specific behavior affects satisfaction in the same domain, first documented in the financial domain by Xiao et al. (2009) and later corroborated by others (e.g., Aboagye & Jung, 2018; Serido et al., 2010; Shim et al., 2012; Sirsch et al., 2020). Xiao et al. (2009) also showed that positive financial behavior had spillover effects on other domain satisfactions and overall life satisfaction among college students. Our results in a sample of parents are generally (finance-related predictors in the model explain 36% of the total variance in SMM vs. 17% in life satisfaction) and specifically consistent with this argument. That is, the proactive financial endeavors of parents affected their SMM to a considerably greater extent than their overall life satisfaction (see Supplemental file 1 for formal test of structural equivalence of the paths). Given that life satisfaction integrates numerous subjective evaluations of one's important life domains (e.g., work, marriage, friendships, health; Nettemeyer et al., 2018; Pavot & Diener, 2008; Schmidt et al., 2023) and one’s management of resources in a specific area (e.g., financial) associates with their satisfaction in the respective domain, our results are not surprising. Yet, some vital abilities, skills, and motivational and behavioral tendencies to manage finances may transfer to other life domains (e.g., realistic goal setting, planning, time management, and resisting temptations).

This part of our findings suggests that enhancing parental proactive financial behavior would benefit both their SMM and life satisfaction. Although saving and financial investment depend on financial ability (e.g., availability of resources) and motivation (Otto, 2013), a study among Slovenian parents of emerging adults (Lep et al., 2022) revealed no association between saving and their level of education, or employment status (both related to the level of income), nor with their child's living arrangement (fully or partly with parents). Half of the non-savers (about a third of the sample) reported a lack of sufficient income to save, but the others claimed to have no financial goals or specific motives to do so. Likewise, goal setting contributed significantly to saving in low-income households (Fry et al., 2008) and general populations (Fisher & Anong, 2012). This goes to show that—at least in Slovenia and countries with similar socio-economic and cultural environments—the encouragement of parents to increase proactive financial behavior through goal setting or development of specific motives to save or invest and of behavioral strategies to compensate for a lack of surplus may present an avenue to improve their SMM and life satisfaction, even for those with low incomes. Martin and Westerhof (2003) also established that available financial resources affect life satisfaction mainly through their positive appraisal, and positive appraisal of the household financial resources (but not parental income-related indicators) was indeed associated with parental saving behavior (Lep et al., 2022). Individuals' appraisal of saving/investing aimed toward their goals appears more important for their SMM and life satisfaction than an objective amount of savings in money and assets.

The Role of Parent–Child Financial Relationships

We further contributed new evidence to the factors that influence SMM and life satisfaction of emerging adult students' parents by offering an insight into the importance of parent–child financial relationships, not only for the students' SMM (Serido et al., 2010; Sirsch et al., 2020) and their subjective well-being (Serido et al., 2010; Shim et al., 2009), but also for those who economically (and otherwise) support the students. Consistent with the proposed model (Fig. 1; H1.4), a more favorable child-perceived financial relationship with the participating parent contributed positively to both parental outcomes. The relative significance of the financial relationship may have even been underestimated in our study compared to the family SES and parental proactive financial behavior (both assessed by the parents), which may have contained shared method variance. Although emerging adults' and parents' ratings of their financial relationships share at least a moderate amount of variance (Damian et al., 2020; Zupančič et al., 2023), the students and their parents perceive their financial relationships from different perspectives and roles (e.g., a recipient and a supporter), which puts additional weight to our finding.

As financial issues become more salient between parents and their children entering emerging adulthood—a period of many transitions (e.g., to tertiary education, moving at least partly/temporarily out of home) and new strivings (e.g., for self-sufficiency, renegotiation of relationships with parents; see also Arnett, 2014; Žukauskienė, 2016)—, they are likely to influence the emotional nature of the parent–child relationships, as well as the family budget. In Slovenia, for example, many parents begin to pay for children's out-of-home residential arrangement during their education, cover extra costs for their education-related activities, etc. The new financial challenges tend to have relational (e.g., parent–child conflicts about money) and financial consequences for the family and its members (e.g., financial strain). Parental rearrangement of the available financial resources and adjustment of behavioral strategies to manage the family budget can be hampered by quarreling about money with the child, disapproval of their spending, and other parent–child discords on effective financial management. This likely results in parental psychological (perhaps also financial) distress and decreases SMM.

In contrast, greater levels of parent–child agreements regarding shared financial values and mutual finance-related compromises may sustain or augment parental SMM. As established with romantic partners, having fewer arguments about money presents a vital relational reward associated with relationship satisfaction (Mao et al., 2017; Totenhagen et al., 2019). Similar reinforcement may be suggested for the relationship between the quality of parent–child financial relationship and children’s (Sirsch et al., 2020) and parental SMM in our study. Our data further imply that conflicts/concords over money matters may enter the quality of parent–child relationships through associations with conflicts/concords about non-financial issues and, thus, exhibit spillover effects on parental overall satisfaction with life.

In other words, parental attempts to improve the financial relationship with their emerging adult child would tend to increase parental SMM and life satisfaction. However, this does not preclude an effect in the opposite direction. Children may perceive their financial relationships with parents more (un)favorably when parents are more (dis)satisfied with their own money management and with life in general. However, it does not appear plausible to target satisfaction as such, but more rewarding financial relationships can be established by, for example, open communication about money, mutual exchange of financial expectations, engagement of children in joint financial decision-making, initiating reasonable financial discussions, and encouraging children as initiators (LeBaron et al., 2020).

The Pathways of Financial Parenting to the Children’s Financial Learning Outcomes

Generally, we reaffirmed that positive financial learning outcomes of emerging adult children were rooted in parent-reported healthy financial parenting, but the shares of variance explained were small. Precisely (supporting H2.1 and H2.2), parental current proactive financial behavior and past financial teaching fostered the child's adopting parental financial role modeling and financial knowledge (i.e., cognitive financial learning outcomes), which, in turn, promoted the child's proactive financial behavior (partly proposed by H2.3 and H2.4, respectively). However, only the students' greater subjective financial knowledge contributed to more favorable perceptions of their financial relationship with the participating parent (partly supporting H2.4). In contrast, those who asserted higher levels of accepting the parent as their financial role model and of engagement in proactive financial behavior did not report a significantly better parent–child financial relationship (partly refuting H2.3 and H2.5, respectively). As we based these pathways to the financial relationship on predominantly mediated effects of both predictors through the students' attitudinal outcomes (Shim et al., 2010, 2015; Sirsch et al., 2020), the lack of significant direct associations does not underscore the importance of both adopting parental role modeling and performing proactive financial behavior for student-perceived positive financial relationships with parents.

Compared to the studies of emerging adults (Serido et al., 2015; Shim et al., 2015; Xiao et al., 2009) which employed a measure of both preventive (precluding future problems) and proactive financial behavior (achieving future goals), we relied solely on the latter due to validity issues of the joined measure in Central European contexts (Sirsch et al., 2020), especially in a sample of Slovenian parents (Zupančič et al., 2023). Although saving is highly valued in Slovenia and annual saving rates are high (Eurostat, 2023; see also Lep et al., 2022), the students' efforts to accumulate money and invest in long-term goals did not significantly affect the quality of their perception of relationships with parents due to money matters, as did these efforts encourage their SMM (Zupančič et al., 2023) and subjective well-being (Serido et al., 2010). The students in our study may have focused on perceptions of parental appreciation (or depreciation) of their behavioral precautions undertaken (or not taken) to manage the available finances when considering their relationships with parents rather than parental content about their saving-oriented behaviors. Perhaps, the parents also reacted more rewardingly to the children’s preventive than proactive behavior in the Slovenian context of normatively expected parental financial support over the children's years of tuition-free education. To test these possibilities, an instrument that captures one’s enactment of effective management of regular expenses (other than budgeting or keeping track of monthly outflows) in a given socio-cultural context is needed. Likewise, employing such a measure with parents would offer an insight into the relative contribution of preventive and proactive financial practices to parental SMM and life satisfaction.

Limitations and Implications

The findings and drawbacks of this study suggest several avenues for future inquiry. Given our sample of first-year university students and their parents, the results cannot generalize to all parents of emerging adults, particularly those whose children are not engaged in education, moved out of the family home, or became financially independent from parents (e.g., earn on their own are supported by their intimate partner). Nonetheless, because students constitute half of the Slovenian 19-to-24-years-olds (SURS, 2022), because we sampled the first-year students from the two largest public universities (out of three in the country), and because our sample of student–parent pairs was relatively large considering the entire two million Slovenian population, we believe the findings might be relatively robust. Albeit the strength of the pathways explaining SMM and life satisfaction of the first-year students' parents is likely to change over the following years (e.g., due to their children's engagement in student work), our findings may apply to parents of emerging adults who remain economically reliant on their family of origin into adulthood (older students, unemployed youth, and young adults). Yet, this proposition awaits an examination in a follow-up study of demographically different samples of emerging adults and their parents.

In the study, we relied on the reports of just one parent. Thus, we disregarded the role of the other parent in financial parenting and in satisfaction of the participating parent, which opens an important subject of investigation. Mothers also overrepresented the participating parents, but according to the population statistics (SURS, 2023a, 2023b, 2023c), the sample was well representative of the same-aged Slovenian adults by the level of education, marital status, number of children, and emerging adult children residing or semi-residing in the family home. Due to the correlational and cross-sectional nature of the study, it remains uncertain how the current parental SMM and life satisfaction may, for example, influence subsequent parental financial behavior and parent–child financial relationships. In this respect, a panel cross-lagged study would offer some valuable insights.

Another limitation was that among the prominent methods of financial parenting (financial teaching and modeling), we did not consider the parental provision of opportunities for their children to learn from their own financial experiences (Le Baron et al., 2019; LeBaron-Black, 2022a). We also assessed only the proactive component of financial behavior as the items pertaining to its preventive component lack sufficient validity in Slovenian samples of parents (Zupančič et al., 2023) and suggest poorer validity in Central European (Sirsch et al., 2020) than the U.S. students (Shim et al., 2010). Additionally, our knowledge in this specific area would benefit from qualitative research on financial parenting in association with parent–child financial relationships and parental SMM. For example, what financial information conveyed from parents to children (LeBaron et al., 2018) is most beneficial, which of the observed financial behaviors do the children most likely decide to model (Rosa et al., 2018), and what kind of opportunities the parents provide for the children to manage the finances on their own (LeBaron et al., 2019) are more effective than others. Considering this knowledge, more efficient interventions could be created based on a further understanding of the outcomes of financial parenting for both children and parents themselves.

Our findings have implications for parents, educators, employers, and family counselors. Although these suggestions are somewhat culturally nuanced, they can be adjusted and applied elsewhere through different institutions and professionals (e.g., financial educators and counselors, family life educators). Parents should get a deeper insight into the importance of their financial instruction to children and enactment of responsible financial behaviors in promoting not only their children's money management and financial well-being but also the quality of their parent–child relationship and, subsequently, their own SMM and satisfaction with life. Research has emphasized a vital role of parental financial socialization for emerging adults' positive life outcomes (e.g., LeBaron-Black et al., 2022b, 2023; Mahapatra et al., 2023), including financial management, independence, and financial well-being (Lanz et al., 2020; LeBaron-Black et al., 2022a; Pak et al., 2023; Serido et al., 2015; Sirsch et al., 2020). Almost negligible attention, however, has been devoted to parental money management and well-being, although many young people co-reside and are otherwise economically reliant on parents (for exceptions, see, e.g., Lep et al., 2022; Zupančič et al., 2023). Communication of our findings (factors influencing parental SMM and life satisfaction) to parents may foster their engagement in financial goal setting and motivation to remedy or enhance their financial relationships with children through adjustment of socialization methods, including open financial communication (LeBaron et al., 2018, 2020). Educators at secondary schools could, for example, assist parents and students by offering family finance workshops. Counselors may find our outcomes helpful at work with families experiencing relationship problems and financial issues, and so may professionals at the university career centers who can help students buffer potential deficiencies in parental financial socialization and poor financial relationships with parents, which tend to affect family financial life, and overall well-being of both parents and children. Employers could likewise contribute to their employees' SMM and life satisfaction by providing professional support services for financially stressed parents (or at risk for financial distress) to manage their family finances.

Conclusion

By focusing on parental outcomes (satisfaction with money management and life satisfaction) and avenues of financial parenting toward these outcomes, this study filled an existing gap in the literature on family financial socialization and subjective well-being of its members. Our data supported the proposed model linking financial parenting to children financial learning outcomes, which, in turn, contributed to parent–child financial relationships. Most importantly, the absence or lower levels of relational strain between parents and their emerging adult children due to financial issues (together with higher family SES and parental proactive financial behavior) contributed significantly to greater satisfaction with money management and overall satisfaction with life in parents. From a theoretical perspective, the findings underline the benefits of successful parental financial socialization for both the offspring's finance-related outcomes and parental satisfaction, which has several practical implications for parents, educators, employers, and family counselors working with families experiencing financial problems or deficits in financial literacy—a prevalent financial issue worldwide.

Data availability

Data, materials, and code are available upon request from the corresponding author. The study was not preregistered.

References

Aboagye, J., & Jung, J. Y. (2018). Debt holding, financial behavior, and financial satisfaction. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 29(2), 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1891/1052-3073.29.2.208

Argyle, M. (2001). Psychology of happiness. Routledge.

Arnett, J. J. (2014). Adolescence and emerging adulthood. Pearson. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199929382.003.0013

Arnett, J. J. (2016). Emerging adults in Europe: Common themes, diverse paths, and future directions. In R. Žukauskiene (Ed.), Emerging adulthood in a European context (pp. 205–216). Routledge.

Bengtson, V., Biblarz, T., & Roberts, R. (2002). How families still matter: A longitudinal study of youth in two generations. Cambridge University Press.

Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowicz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54, 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.165

Chalise, L., & Anong, S. (2017). Spending behavior change and financial distress during the Great Recession. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 28(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1891/1052-3073.28.1.49

Chopik, W. J. (2017). Associations among relational values, support, health, and well-being across the adult lifespan. Personal Relationships, 24, 408–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12187

Curran, M. A., Parrott, E., Ahn, S. Y., Serido, J., & Shim, S. (2018). Young adults’ life outcomes and well-being: Perceived financial socialization from parents, the romantic partner, and young adults’ own financial behaviors. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 39, 445–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-018-9572-9

Damian, L. E., Negru-Subtirica, O., Domocus, I. M., & Friedlmeier, M. (2020). Healthy financial behaviors and financial satisfaction in emerging adulthood: A parental socialization perspective. Emerging Adulthood, 8(6), 548–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696819841952

Descartes, L. (2006). »Put your money where your love is«: Parental aid to adult children. Journal of Adult Development, 13, 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-007-9023-6

Dew, J. (2011). Financial issues and relationship outcomes in cohabiting individuals. Family Relations, 60, 178–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00641.x

Dew, J., & Stewart, R. (2012). A financial issue, a relationship issue, or both? Examining the predictors of marital financial conflict. Journal of Financial Therapy, 3(1), 43–61. https://doi.org/10.4148/jft.v3i1.1605

Dew, J. P., & Xiao, J. J. (2013). Financial declines, financial behaviors, and relationship satisfaction during recession. Journal of Financial Therapy, 4(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.4148/jft.v4i1.1723

Di Domenico, S., Ryan, R. M., Bradshaw, E. L., & Duineveld, J. J. (2022). Motivations for personal financial management: A self-determination theory perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 977818. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.977818

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being. The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34

Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2002). Will money increase subjective well-being? Social Indicators Research, 57(2), 119–169. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014411319119

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/t01069-000

Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2000). Money and happiness: Income and subjective well-being across nations. In E. Diener & E. M. Suh (Eds.), Culture and subjective well-being (pp. 185–218). The MIT Press.

Douglass, C. B. (2007). From duty to desire: Emerging adulthood in Europe and its consequences. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 101–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00023.x

Erikson, E. H. (1963). Childhood and society (2nd edition). Norton.

Eurostat (2023). Household saving rate (tec00131) [Data Set]. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/-/tec00131

Fan, L., & Chatterjee, S. (2017). Borrowing decision of households: An examination of the information search process. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 28(1), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1891/1052-3073.28.1.95

Fingerman, K. L., Cheng, Y.-P., Wesselmann, E. D., Zarit, S. H., Furstenberg, F. F., Jr., & Birditt, K. S. (2012). Helicopter parents and landing pad kids: Intense parental support of grown children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(4), 880–896. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00987.x

Fisher, P. J., & Anong, S. T. S. (2012). Relationship of saving motives to saving habits. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 23(1), 63–79.

Fry, R. (2013). Living with parents since the recession. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/08/01/living-with-parents-since-the-recession

Fry, T. R. L., Mihajilo, S., Russell, R., & Brooks, R. (2008). The factors influencing saving in a matched savings program: Goals, knowledge of payment instruments, and other behavior. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 29(2), 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-008-9106-y

Gudmunson, C. G., & Danes, S. M. (2011). Family financial socialization: Theory and critical review. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32, 644–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9275-y

Headey, B., & Wearing, A. (1992). Understanding happiness: A theory of subjective well-being. Longman Cheshire.

Hilgert, M. A., Hogarth, J. M., & Beverly, S. G. (2003). Household financial management: The connection between knowledge and behavior. Federal Reserve Bulletin, 89, 309–322.

Hira, T. K. (2012). Promoting sustainable financial behavior: Implications for education and research. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 36(5), 502–507. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2012.01115.x

Hong, P., Cui, M., Ledermann, T., & Love, H. (2021). Parent-child relationship satisfaction and psychological distress in parents and emerging adult children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30, 921–931. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-01916-4

Hsieh, C.-M. (2003). Income, age and financial satisfaction. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 56(2), 89–112. https://doi.org/10.2190/KFYF-PMEH-KLQF-EL6K

Hsieh, C.-M. (2004). Income and financial satisfaction among older adults in the United States. Social Indicators Research, 66, 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SOCI.0000003585.94742.aa

Iannello, P., Sorgente, A., Lanz, M., & Antonietti, A. (2020). Financial well-being and its relationship with subjective and psychological well-being among emerging adults: Testing the moderating effect of individual differences. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22, 1385–1411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00277-x

Jorgensen, B. L., Rappleyea, D. L., Schweichler, J. T., Fang, X., & Moran, M. E. (2017). The financial behavior of emerging adults: A family financial socialization approach. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 38(1), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-015-9481-0

Kim, J. H., & Torquati, J. (2020). Are you close with your parents? The mediation effects of parent–child closeness on young adults’ financial socialization through young adults’ self-reported responsibility. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 42, 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09725-5

Kins, E., Beyers, W., & Soenens, B. (2012). When the separation-individuation process goes awry: Distinguishing between dysfunctional dependence and dysfunctional independence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 37(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025412454027

Komidar, L., Zupančič, M., Sočan, G., & Puklek Levpušček, M. (2014). Development and construct validation of the Individuation Test for Emerging Adults (ITEA). Journal of Personality Assessment, 96(5), 503–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.850703

Kuhar, M., & Hlebec, V. (2019). Družina in prijatelji [Family and friends]. In A. Naterer, M. Lavrič, R. Klanjšek, S. Flere, T. Rutar, D. Lahe, M. Kuhar, V. Hlebec, T. Cupar, & Ž Kobše (Eds.), Slovenska mladina 2018/2019 [Slovenian youth 2018/2019] (pp. 29–36). Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

Kuhar, M., & Reiter, H. (2014). Leaving home in Slovenia: A quantitative exploration of residential independence among young adults. Journal of Adolescence, 37, 1409–1419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.05.011

Lahe, D., Cupar, T., Deželan, T., & Vombergar, N. (2021). Demografija, omrežja socialnih opor in medgeneracijsko sodelovanje [Demographics, networks of social support, and intergenerational cooperation]. In M. Lavrič & T. Deželan (Eds.), Mladina 2020: Položaj mladih v Sloveniji [Youth 2020: The situation of young people in Slovenia] (pp. 55–90). Univerza v Mariboru, Univerzitetna založba; Založba Univerze v Ljubljani.

Lanz, M., Sorgente, A., & Danes, S. M. (2020). Implicit family financial socialization and emerging adults’ financial well-being: A multi-informant approach. Emerging Adulthood, 8(6), 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696819876752

LeBaron, A. B., Hill, E. J., Rosa, C. M., Spencer, T. J., Marks, L. D., & Powell, J. T. (2018). I wish: Multigenerational regrets and reflections on teaching children about money. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 39(2), 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-017-9556-1

LeBaron, A. B., Marks, L. D., Rosa, C. M., & Hill, E. J. (2020). Can we talk about money? Financial socialization through parent–child financial discussion. Emerging Adulthood, 8(6), 453–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696820902673

LeBaron, A. B., Runyan, S. D., Jorgensen, B. L., Marks, L. D., Li, X., & Hill, E. J. (2019). Practice makes perfect: Experiential learning as a method for financial socialization. Journal of Family Issues, 40(4), 435–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X18812917

LeBaron-Black, A. B., Curran, M. A., Hill, E. J., Toomey, R. B., Speirs, K. E., & Freeh, M. E. (2022a). Talk is cheap: Parent financial socialization and emerging adult financial well-being. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12751

LeBaron-Black, A. B., Li, X., Okamoto, R. M., Saxey, M. T., & Driggs, T. M. (2022b). Finances and fate: Parent financial socialization, locus of control, and mental health in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 10(6), 1484–1496. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968221110541

LeBaron-Black, A. B., Saxey, M. T., Driggs, T. M., & Curran, M. A. (2023). From piggy banks to significant others: Associations between financial socialization and romantic relationship flourishing in emerging adulthood. Journal of Family Issues, 44(5), 1301–1320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X211057536

Lep, Ž, Zupančič, M., & Poredoš, M. (2022). Saving of freshmen and their parents in Slovenia: Saving motives and links to parental financial socialization. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 43(4), 756–773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-021-09789-x

Li, X., Curran, M. A., LeBaron, A. B., Serido, J., & Shim, S. (2020). Romantic attachment orientations, financial behaviors, and life outcomes among young adults: A mediating analysis of a college cohort. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 41, 658–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09664-1

Mahapatra, M. S., Xiao, J. J., Mishra, R. K., & Meng, K. (2023). Parental financial socialization and life satisfaction of college students: Mediation and moderation analyses. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-10-2022-1626

Mao, D. M., Danes, S. M., Serido, J., & Shim, S. (2017). Financial influences impacting young adults’ relationship satisfaction: Personal management quality, perceived partner behavior, and perceived financial mutuality. Journal of Financial Therapy, 8(2), 24–41. https://doi.org/10.4148/1944-9771.1151

Martin, M., & Westerhof, G. J. (2003). Do you need to have them or should you believe you have them? Resources, their appraisal, and well-being in adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 10, 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022439915499

Mendonça, M., & Fontaine, A. M. (2013). Late nest leaving in Portugal: Its effects on individuation and parent-child relationships. Emerging Adulthood, 1(3), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696813481773

Moschis, G. P. (1987). Consumer socialization: A life-cycle perspective. Lexington Books.

Netemeyer, R. G., Warmath, D., Fernandes, D., & Lynch, J. G., Jr. (2018). How am I doing? Perceived financial well-being, its potential antecedents, and its relation to overall well-being. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(1), 68–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx109

OECD (2023). Income inequality (indicator). https://doi.org/10.1787/459aa7f1-en

Otto, A. (2013). Saving in childhood and adolescence: Insights from developmental psychology. Economics of Education Review, 33, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2012.09.005

Pak, T.-Y., Fan, L., & Chatterjee, S. (2023). Financial socialization and financial well-being in early adulthood: The mediating role of financial capability. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12959

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. Psychological Assessment, 5(2), 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.164

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701756946

Robb, C. A. (2014). The personal financial knowledge conundrum. Journal of Financial Service Professionals, 68(4), 69–72.

Rojas, M. (2007). Life satisfaction and satisfaction in domains of life: Is it a simple relationship? Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 7(4), 467–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9009-2

Rosa, C. M., Marks, L. D., LeBaron, A. B., & Hill, E. J. (2018). Multigenerational modeling of money management. Journal of Financial Therapy, 9(2), 54–74. https://doi.org/10.4148/1944-9771.1164

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rossi, A. S., & Rossi, P. H. (1990). Of human bonding: Parent-child relations across the life course. Aldine de Gruyter.

Ryff, C. D., Schmutte, P. S., & Lee, Y. H. (1996). How children turn out: Implications for parental self-evaluation. In C. D. Ryff & M. M. Seltzer (Eds.), The parental experience at midlife (pp. 383–422). University of Chicago Press.

Schmidt, M. E., Pellicciotti, H., & Lang, R. M. (2023). An exploration of friendship and well-being in established adulthood and midlife. Journal of Adult Development, 30, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-022-09421-8

Seghieri, C., Desantis, G., & Tanturri, M. L. (2006). The richer, the happier? An empirical investigation in selected European countries. Social Indicators Research, 79, 455–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-5394-x

Serido, J., Curran, M. J., Wilmarth, M., Ahn, S. Y., Shim, S., & Ballard, J. (2015). The unique role of parents and romantic partners on college students’ financial attitudes and behaviors. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 64(5), 696–710. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12164

Serido, J., Shim, S., Mishra, A., & Tang, C. (2010). Financial parenting, financial coping behaviors, and well-being of emerging adults. Family Relations, 59(4), 453–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00615.x

Shi, J., Ullah, S., Zhu, X., Dou, S., & Siddiqui, F. (2021). Pathways to financial success: An empirical examination of perceived financial well-being based on financial coping behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 762772. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.762772

Shim, S., Barber, B. L., Card, N. A., Xiao, J. J., & Serido, J. (2010). Financial socialization of first-year college students: The roles of parents, work, and education. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(12), 1457–1470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9432-x

Shim, S., Serido, J., & Tang, C. (2012). The ant and the grasshopper revisited: The present psychological benefits of saving and future oriented financial behaviors. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(1), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.08.005

Shim, S., Serido, J., Tang, C., & Card, N. (2015). Socialization processes and pathways to healthy financial development for emerging young adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 38, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2015.01.002

Shim, S., Xiao, J. J., Barber, B. L., & Lyons, A. C. (2009). Pathways to life success: A conceptual model of financial well-being for young adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30, 708–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2009.02.003

Sirgy, M. J. (2012). The psychology of quality of life: Hedonic well-being, life satisfaction, and eudaimonia (2nd ed.). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4405-9

Sirsch, U., Zupančič, M., Poredoš, M., Levec, K., & Friedlmeier, M. (2020). Does parental financial socialization for emerging adults matter? The case of Austrian and Slovene first-year university students. Emerging Adulthood, 8(6), 509–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696819882178

Sorgente, A., & Lanz, M. (2017). Emerging adults’ financial well-being: A scoping review. Adolescent Research Review, 2(4), 255–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-016-0052-x

Sorgente, A., & Lanz, M. (2019). The multidimensional subjective financial well-being scale for emerging adults: Development and validation studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 43(5), 466–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419851859

SURS (2022). Share of population in formal education by type of program and age (%), Slovenia, annually . Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/en/Data/Data/0951315S.px/

SURS (2023a). Population aged 15 years or more by education, age and sex, Slovenia, annually (05G2002S) . https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/en/Data/Data/05G2002S.px/

SURS (2023b). Population aged 15 years or more by activity status, sex and age, Slovenia, annually (05G3002S) . https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/en/Data/Data/05G3002S.px/

SURS (2023c). Population by household status, 5-year age groups and sex, cohesion regions, Slovenia, multiannually (05E3002S) . https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/en/Data/Data/05E3002S.px/

Tanner, J. L. (2006). Recentering during emerging adulthood: A critical turning point in life span human development. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in 21st century (pp. 21–55). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11381-002

Tay, L., Batz, C., Parrigon, S., & Kuykendall, L. (2017). Debt and subjective well-being: The other side of the income-happiness coin. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(3), 903–937. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9758-5

Tiefenbach, T., & Kohlbacher, F. (2015). Individual differences in the relationship between domain satisfaction and happiness: The moderating role of domain importance. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.040

Totenhagen, C. J., Wilmarth, M. J., Serido, J., Curran, M. A., & Shim, S. (2019). Pathways from financial knowledge to relatioship satisfaction: The roles of financial behaviors, perceived shared financial values with the romantic partner, and debt. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40, 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-019-09611-9

Ward, R. A. (2008). Multiple parent-adult child relations and well-being in middle and later life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 63B(4), S239–S247. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/63.4.S239

Xiao, J. J., Chen, C., & Chen, F. (2014). Consumer financial capability and financial satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 118, 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0414-8

Xiao, J. J., & O’Neill, B. (2018). Propensity to plan, financial capability, and financial satisfaction. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 42, 501–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12461

Xiao, J. J., Tang, C., Serido, J., & Shim, S. (2011). Antecedents and consequences of risky credit behavior among college students: Application and extension of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 30(2), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.30.2.239

Xiao, J. J., Tang, C., & Shim, S. (2009). Acting for happiness: Financial behavior and life satisfaction of college students. Social Indicators Research, 92, 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9288-6

Žukauskienė, R. (2016). Emerging adulthood in a European context. Routledge.

Zupančič, M., & Sirsch, U. (2018). Različni vidiki prehoda v odraslost [Different perspectives of becoming an adult]. In M. Zupančič & M. Puklek Levpušček (Eds.), Prehod v odraslost: sodobni trendi in raziskave [Emerging adulthood: Current trends and research] (pp. 11–50). Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani. https://doi.org/10.4312/9789610605041

Zupančič, M., Poredoš, M., & Lep, Ž. (2023). Intergenerational model of financial satisfaction and parent-child financial relationship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 40(8), 2568–2591. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075231153352

Funding

This work was financially supported by Javna agencija za raziskovalno in inovacijsko dejavnost Republike Slovenije (Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency) within the research program Applied Developmental Psychology (research core funding No. P5-0062).

Author information