Abstract

Purpose

Racial differences in prevalence rates of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have shifted in the United States (US) since the 1990s. This review addresses the nature and context of this shift and discusses potential contributing factors and areas for future research.

Methods

Seventeen population-based epidemiological birth cohort studies on ASD prevalence in the US that included race as a variable are included in the review. Studies were identified via a keyword search on PubMed. To be included, studies were required to include race or ethnicity as a variable in the prevalence estimates, include at least 1000 cases with autism, and be published in English by June 3rd, 2023.

Results

Results suggest that in nearly all birth cohorts prior to 2010, ASD prevalence rates were highest among White children. ASD prevalence rates among Black, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander (API) children (22.3, 22.5, and 22.2 per 1000, respectively) surpassed prevalence rates among White children (21.2 per 1000) in the 2010 birth cohort and continued to increase in the 2012 birth cohorts.

Conclusions

There are persistent racial differences in ASD prevalence in the US, and these differences were inverted after 2010, when ASD prevalence among Black, Hispanic, & API children surpassed ASD prevalence among White children. Possible drivers of this racial repatterning of ASD prevalence include changes in ASD screening and diagnosis, changes to health insurance policy, changes to immigration policy, and increased education attainment by minority groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a group of childhood-onset neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by impairments in communication and social interaction and by restricted interests and repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). ASD prevalence has increased globally since the 1990s (Elsabbagh et al., 2012; Zeidan et al., 2022); in the United States (US), ASD prevalence increased from 1 in 150 children born in 1992 (Rice, 2007) to 1 in 36 children born in 2012 (Maenner et al., 2023). Increased screening for ASD, broadening of diagnostic criteria, increased access to diagnostic and treatment services, and increased public awareness have significantly contributed to the increase in prevalence (Hansen et al., 2015; Maenner et al., 2023; Wazana et al., 2007; Zeidan et al., 2022).

As the overall ASD prevalence has increased and the sociocultural landscape in the US has changed, racial differences in prevalence have also shifted: ASD was most prevalent among White children in the 1990s but is now most prevalent among Black, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander (API) children (Maenner et al., 2023; Nevison & Parker, 2020). While recent review papers focus mainly on understanding and addressing the structural and sociocultural inequities that drive racial disparities in diagnosis, treatment, and service utilization (Aylward et al., 2021; Brasher et al., 2022; Pham & Charles, 2023), no study has yet to systematically examine when, how, and why the shift in ASD prevalence by race group occurred.

Autism was initially described by Leo Kanner in 1943 (Kanner, 1943) and then first appeared in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition (DSM-III) as ‘autistic disorder,’ defined as lack of responsiveness to other people, gross language deficits, peculiar speech, and bizarre behaviors with an onset before 30 months (American Psychiatric Association, 1980). Initial prevalence estimates were reported to be approximately 4.5 in 10,000 (Lotter, 1966). Since that time, prevalence rates have steadily risen, and several factors are thought to contribute to this increase.

One important factor is changing diagnostic criteria. With the release of the DSM-III-R in 1987, the definition of autistic disorder broadened to encompass early childhood-onset symptoms characterized by impaired social interaction, communication, and imaginative activity, and by restricted interests and activities (American Psychiatric Association, 1987). Even this subtle shift in language resulted in a likely increased rate of autism diagnosis (Volkmar et al., 1988). In 1994, with the publication of the DSM-IV, autistic disorder became encompassed within a larger category called pervasive developmental disorders (PDD), which also included Asperger’s syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, PDD Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS), and Rett syndrome (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). PDD-NOS was a subthreshold diagnosis applied when autism-related features were present but full criteria for autistic disorder or Asperger’s syndrome were not met. Indeed, population-based epidemiological studies at the time showed that among the PDDs, PDD-NOS was the most prevalent (Chakrabarti & Fombonne, 2005). With the release of the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), all the PDDs except for Rett syndrome were combined under a new umbrella term, autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Other factors contributing to increasing prevalence rates are enhanced screening and younger age of diagnosis. The diagnosis of ASD can usually be established reliably by 24 months (Lord et al., 2006), and to receive an ASD diagnosis, children are evaluated by a multidisciplinary team that typically includes a child psychologist, developmental pediatrician, child psychiatrist, or another professional with expertise in diagnosing ASD (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2015). The gold standard for the evaluation of ASD includes a developmental history, a direct observational assessment of ASD symptoms, and application of DSM-5 criteria. Standardized assessments of adaptive functioning, language, and cognitive abilities are also typically performed (Sanchack & Thomas, 2016). Beginning in 2007, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended that pediatricians screen toddlers for ASD at age 18 months and 24 months using a validated and specific tool (Johnson et al., 2007). This recommendation led to increased early detection; children with ASD who screen positive on the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers with Follow-Up (M-CHAT/F) are diagnosed 7.45 months earlier on average than children who screen negative (Guthrie et al., 2019). Earlier age of diagnosis increases ASD prevalence rates in population-based birth cohort studies (Hertz-Picciotto & Delwiche, 2009).

Regulatory factors also have a significant impact on ASD prevalence. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) defines eligibility criteria for receiving special education services in the US. Prior to 1990, autism did not necessarily entitle one to specialized education, whereas intellectual disability (ID) did. IDEA was revised in 1991 to include ASD as a serviceable diagnosis (Education of the Handicapped Act Amendments of, 1990), and subsequently diagnostic substitution led to increased rates of the ASD diagnosis with decreasing rates of ID. For example, one population-based birth cohort study in California found the prevalence of autistic disorder to increase from 5.8 to 14.9 per 10,000 between 1991 and 1994 while the prevalence of ID decreased correspondingly from 28.8 to 19.5 per 10,000 over the same time period (Croen, Grether, Hoogstrate et al., 2002).

In addition to increases in overall rates of ASD diagnosis, prevalence varies between socioeconomic and cultural groups. For example, studies have shown that ASD prevalence in the US varies by primary spoken language (Dickerson, 2018), insurance status (King & Bearman, 2011; Winter et al., 2020), parental educational attainment (Croen et al., 2002b; Dickerson et al., 2017; King & Bearman, 2011; Winter et al., 2020), and neighborhood wealth (Dickerson et al., 2017; Durkin et al., 2017; King & Bearman, 2011; Mazumdar et al., 2013; Nevison & Parker, 2020). ASD prevalence in the US also varies by Black, White, API, and American Indian/Native American (AI/NA) race and by Hispanic versus non-Hispanic ethnicity. It is thought that these variations are driven by racial disparities in access to ASD diagnostic and healthcare resources (Aylward et al., 2021; Pham & Charles, 2023).

ASD is primarily considered genetic in origin with heritability estimates ranging from 70 to 90% (Bailey et al., 1995; Steffenburg et al., 1989). The genetic landscape is comprised of both common variants and rare de novo and inherited variants, with potentially hundreds of loci contributing to the phenotype through a polygenic inheritance pattern (Ramaswami & Geschwind, 2018). Gene discovery efforts have failed to include substantial numbers of non-White individuals, so it is unclear whether genetic drivers of ASD prevalence vary by race or ethnicity (Hilton et al., 2009). However, worldwide ASD prevalence does not vary significantly based on geographic region or ethnicity, so genetic drivers of ASD prevalence are likely constant between racial and ethnic groups (Elsabbagh et al., 2012).

Racial health disparities occur when health outcomes and access to necessary healthcare services differ between racial and ethnic groups (National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, 2022). Racial health disparities are common in medicine (Bayne et al., 2023; Lewsey & Breathett, 2021; Owen et al., 2013; Richardson et al., 2003), including in the field of psychiatry (Akinhanmi et al., 2018; Garb, 2021; Garrett et al., 2023). For instance, Black and Hispanic Americans receive mental health care less often than White Americans, and disparities in access to mental health care between Black, Hispanic, and White Americans increased in the US between 2004 and 2012 (Cook et al., 2017). Moreover, Black patients are more than twice as likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia compared to White patients (Olbert et al., 2018) but are less likely to receive clozapine, the only FDA-approved drug for treatment-resistant schizophrenia (Ventura et al., 2022).

Racial health disparities permeate ASD screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Discrimination by healthcare providers, cultural stigma, income disparities, differences in citizenship status, and a shortage of multilingual clinicians present obstacles for racial and ethnic minority groups seeking ASD assessment and treatment (Brasher et al., 2022). Accordingly, Black and Hispanic children have historically been diagnosed with ASD at an older age than White children (Mandell et al., 2002; Valicenti-McDermott et al., 2012), although recent research suggests that this disparity is closing (Maenner et al., 2020). Similarly, among a cohort of 406 Medicaid-eligible children in Philadelphia, Black children with ASD were 2.6 times more likely to be misdiagnosed; they were 5.1 times more likely to be diagnosed with adjustment disorder and 2.4 times more likely to be diagnosed with conduct disorder prior to ASD diagnosis (Mandell et al., 2007). In another study using semi-structured interviews of female caregivers of Black children with ASD, “the majority of caregivers felt racism affected their experiences seeking primary healthcare services for their child with ASD” (Dababnah et al., 2018).

Cultural stigma and lack of awareness surrounding ASD may also impede diagnosis among Black and Hispanic children. At least three different qualitative studies have reported that Black and Hispanic/Latino parents of children with ASD face stigma and social isolation, which can dissuade them from accepting referrals for ASD symptoms (Cohen & Miguel, 2018; Dababnah et al., 2018; Ijalba, 2016). Other qualitative studies document that Hispanic/Latino parents have limited awareness of ASD and may assume that signs that indicate elevated risk for ASD are instead characteristic of typical development (Ijalba, 2016; Zuckerman et al., 2014).

The aim of this review is to summarize temporal trends in ASD prevalence by race group among children born in the US between 1987 and 2016 by evaluating population-based epidemiological studies, and to clarify the implications of this shift. These results will complement existing knowledge on racial disparities in ASD diagnosis and provide a foundation for future research on associated factors.

Methods

A systematic review of autism prevalence by race in the US was conducted according to the PRISMA criteria (Page et al., 2021). A keyword search was done on PubMed using the following search terms: ‘autism’ or ‘ASD’ and ‘prevalence’ and ‘race’ or ‘ethnicity’ in the title, abstract, and keywords sections. Additional studies were identified in the reference sections of review papers found in the keyword search. To be included in this review, studies were required to (1) be population-based epidemiological birth cohort studies conducted in the US, (2) include race or ethnicity as a variable in the prevalence estimates, (3) include at least 1000 cases with autism, (4) be published in English by June 3rd, 2023. Three reviewers independently screened each study for inclusion in the review, assessed each study for potential bias, and extracted study data. Risk of bias in each study was assessed using the ROBINS-I tool (Sterne et al., 2023). The review was not registered, and a protocol was not prepared.

Results

479 articles were identified using the keyword search criteria. Of these, twenty-two studies were identified that met our a priori criteria. Five of the twenty-two studies (Braun et al., 2015; Christensen et al., 2019; Dickerson et al., 2017; Jarquin et al., 2011; Pedersen et al., 2012) were excluded because of insufficient information to allow data synthesis. Seventeen studies remained and are included in this review (Fig. 1). Data on ASD prevalence by race group in a set year or series of years was retrieved from each study. Prevalence values were converted to cases per 1000 population when necessary. In one of the included studies (Rice, 2007), data stratified by state were combined during the review process to attain a sample size greater than 1000 cases with ASD. All studies included in the review were determined to have a moderate risk of bias due to confounding by insurance coverage, education level, and socioeconomic status. Study characteristics, results, and confidence intervals for each included study are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only. Adapted from Page et al., 2021

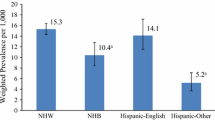

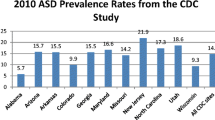

Thirteen of the seventeen studies are affiliated with the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network (Baio, 2012, 2014; Baio et al., 2018; Christensen et al., 2016; Durkin et al., 2017; Maenner et al., 2020, 2021, 2023; Mandell et al., 2009; Rice, 2007, 2009; Shaw et al., 2020, 2023). ADDM has reported ASD prevalence in sites located across the US every other year since 2000. Each site monitors ASD prevalence among 8-year-olds in a specific geographic area of its state. Some ADDM sites have also monitored ASD prevalence among 4-year-olds starting in surveillance year 2014 (Christensen et al., 2019; Shaw et al., 2020). Sites ascertain ASD prevalence using medical and/or public school records. Any child with a documented diagnosis of ASD (or PDD prior to 2013), enrollment in special education services with a classification of ASD, or an International Classification of Diseases code consistent with ASD (e.g., F84 or 299) is considered a potential ASD case. In surveillance years 2000–2016, ADDM Network clinicians conducted deidentified chart review on all potential ASD cases to confirm that each case met the DSM criteria for ASD before adding it to the ASD prevalence counts. Since 2018, all potential ASD cases have been included in the ASD prevalence counts. Data on race and ethnicity of cases are derived from medical records, school records, birth certificate linkages, or administrative and billing information. Population denominators are obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics race estimates or from the most recent US census and include categories for AI/AN, API, Black, White, and two or more races, and Hispanic ethnicity. Any case with Hispanic ethnicity is excluded from all other racial groups. Results from the thirteen included ADDM studies are collectively represented in a graph of ASD prevalence by race group over time (Fig. 2).

ADDM Data on Time Trends in ASD Prevalence by Race Group 1992–2012. *Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All data and CIs were originally reported in the ADDM reports except for the 1992 birth cohort, in which prevalence was calculated as a proportion using data from Rice (2007), with CIs derived from the binomial calculation

Across race groups, ASD prevalence is higher in males (43.0 per 1000) than in females (11.4 per 1000) (Maenner et al., 2023). According to data collected by the ADDM Network, ASD prevalence has increased from 6.2 per 1000 among children born in 1994 (Durkin et al., 2017) to 27.6 per 1000 among children born in 2012 (Maenner et al., 2023). The ten biannual ADDM reports included in the review show that ASD prevalence was originally highest among White children, but this pattern inverted for children born in 2008 or later. Reports on birth cohorts before 2008 indicate that ASD prevalence among White children was higher than ASD prevalence among children from any other racial group, while prevalence among Hispanic children was lower than ASD prevalence among children from any other group (Baio, 2012, 2014; Baio et al., 2018; Christensen et al., 2016; Durkin et al., 2017; Maenner et al., 2020; Mandell et al., 2009; Rice, 2007, 2009). For instance, in the 1994 birth cohort, ASD prevalence was 6.7 (95% confidence interval (CI) 6.4-7.0) per 1000 among White children, while it was 5.9 (CI 5.4–6.5) and 3.9 (CI 3.4–4.5) per 1000 among Black and Hispanic children, respectively (Durkin et al., 2017). Therefore, in the 1994 birth cohort, the Black to White odds ratio (OR) was 0.79 (CI 0.64–0.96), while the Hispanic to White OR was 0.76 (CI 0.56–0.99) (Mandell et al., 2009). In the 2010 birth cohort, ASD prevalence among White children was 21.2 (CI 20.3–22.0) per 1000. This was roughly equal to ASD prevalences among Black, Hispanic, and API children, which were 22.3 (CI 21.0-23.7), 22.5 (CI 21.2–23.9), and 22.2 (CI 19.8–24.8) per 1000, respectively, resulting in a White to Black prevalence ratio (PR) of 0.9 (CI 0.9-1.0), a White to Hispanic PR of 0.9 (CI 0.9-1.0), and a White to API PR of 1.0 (CI 0.8–1.1) (Maenner et al., 2021). The most recent ADDM report from the 2012 birth cohort reveals that the racial patterning of ASD prevalence in the US has fundamentally shifted; ASD prevalence among White children is now 24.3 (CI 23.4–25.2) per 1000, lower than ASD prevalences among Black, Hispanic, and API children, which are 29.3 (CI 27.9–30.9), 31.6 (CI 30.0–33.3), and 33.4 (CI 30.5–36.4) per 1000, respectively. Accordingly, the Black to White PR is now 1.2 (CI 1.1–1.3), while the Hispanic to White PR is 1.3 (CI 1.2–1.4) and the API to White PR is 1.4 (CI 1.2–1.5) (Maenner et al., 2023) (Table 1; Fig. 2).

Two of the eighteen studies included in the review are analyses of medical records from the California Department of Developmental Services (DDS) (Croen et al., 2002b; Winter et al., 2020). Individuals with ASD in California can enroll in the DDS to receive support services, and most Californians with ASD are enrolled. ASD diagnoses are confirmed by healthcare professionals at DDS centers in California. Before the release of the DSM-5, the DDS included individuals with autistic disorder but not Asperger’s syndrome or PDD-NOS in its autism case counts. In 2014, the DDS began to include all individuals who met the DSM-5 definition of ASD in its case counts.

The California DDS studies support the ADDM Network’s findings. Croen et al. (2002) examine ASD prevalence among 0-10-year-olds from a 1989–1994 birth cohort and find that Hispanic children were less likely to be diagnosed with autistic disorder than White and Asian children, with an OR of 0.6 (CI 0.5–0.6), while Black children were more likely to be diagnosed, with an OR of 1.2 (CI 1.1–1.3). While this finding among Black children is not consistent with the early ADDM studies, the results among Hispanic children are consistent. Winter and colleagues (2020) find that autism prevalence among 3-6-year-olds was lower in children of Hispanic mothers than in children of White mothers born from 1992 to 2008 but has been lowest in children of White mothers born after 2011 due to increased prevalence among children of Hispanic, Black, and Asian mothers. For instance, in the 1992 birth cohort, ASD prevalence was 4.5 (CI 4.2–4.8) per 1000 among children of White mothers, while it was 2.2 (CI 2.0-2.4) per 1000 among children of Hispanic mothers. In the 2012 birth cohort, ASD prevalence was 13.0 (CI 12.4–13.6) per 1000 among children of White mothers, while it was 14.5 (CI 14.0–15.0) per 1000 among children of Hispanic mothers (Winter et al., 2020). This finding may be confounded by the broadening of the California DDS diagnostic criteria from autistic disorder to ASD in 2014, and Winter et al.’s (2020) study differs from other studies covered by this review in that it categorizes children by maternal race, resulting in potential differences in the categorization of biracial children. The studies nevertheless support the ADDM Network findings that ASD prevalence in the Hispanic and API race groups surpassed ASD prevalence in the White race group around 2010 (Table 2).

Shifts in ASD/PDD prevalence by race around 2010 are also reflected in nationwide non-ADDM analyses of school and medical records. Analysis of IDEA school records for 6-21-year-olds born in 1987–2002 indicates that prevalence of enrollment in special education services for ASD was highest in API children, then White children, then Black children, then AI/AN children, and lowest among Hispanic children (Sullivan, 2013). Analysis of medical records from Cosmos, a dataset defined by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, indicates that ASD prevalence among 8-year-olds was highest among White children born in 2009 but highest among Black children born in 2013, with a gradual shift in rates between 2009 and 2013 (Pham et al., 2022) (Table 2).

Discussion

This review suggests that there are persistent racial differences in ASD prevalence in the US, and that these differences appear to have inverted in children born after 2010, when ASD prevalence among Black, Hispanic, & API children surpassed ASD prevalence among White children. Studies from the United Kingdom (UK), Israel, and Western Australia also identify differences in ASD prevalence between race groups in their respective countries, but they are difficult to compare to US-based studies because each country defines its race groups differently. Furthermore, none of these studies allow for comparison of time trends in ASD prevalence by race. A UK-based case-control prevalence cohort study suggests that ASD prevalence is lowest among Roma children, then Asian children, then Chinese children, then White children, and highest among Black children (Roman-Urrestarazu et al., 2021). A total population retrospective study (Raz et al., 2015) and total population nested case-control study (Segev et al., 2019) from Israel argue that ASD prevalence is lower among Arabs than the general population. A retrospective cohort study from Western Australia finds that ASD prevalence is lower among aboriginal children than Caucasian children (Fairthorne et al., 2017).

The shift in comparative rates of ASD prevalence by race group in the US may be due to improvements in ASD diagnosis in racial minorities. Data suggests that the gap in age at time of ASD diagnosis between Black, Hispanic, and White children in the US is closing. In a 1993–1999 birth cohort of 406 Medicaid-eligible children with ASD in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Black children were diagnosed 1.6 years later than White children on average (Mandell et al., 2002). In a 2003–2010 birth cohort of 399 children with ASD in The Bronx, New York, Black children were diagnosed seven months later than White children on average, while Hispanic children were diagnosed five months later than White children (Valicenti-McDermott et al., 2012). In the 2008 ADDM birth cohort, Black children were diagnosed just two months later than White children on average, while Hispanic children were diagnosed at the same age as White children (Maenner et al., 2020). These improvements may be driven by policy changes that made ASD diagnosis more accessible, such as the expansion of IDEA in 1991 and the AAP’s ASD screening guidelines in 2007. However, healthcare providers may also be over-diagnosing Black and Hispanic children with ASD. In a survey of 400 behavioral pediatricians with clinical interest in ASD, 58% of providers stated that their colleagues at least sometimes over-diagnose ASD (Azim et al., 2020). More research is needed to explore whether ASD over-diagnosis in racial minorities has contributed to the racial repatterning of ASD prevalence.

The passing of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 led to changes in health insurance coverage in the US that may also have played a role in the racial repatterning of ASD prevalence. Rates of insurance coverage among all race groups substantially increased after implementation of the ACA, while racial disparities in insurance coverage decreased. Between 2010 and 2021, the uninsured shares of the nonelderly Black, Hispanic, API, & AI/AN populations fell by 9%, 14%, 11%, and 11%, respectively, while the uninsured share of the nonelderly White population fell by only 6% (Artiga et al., 2022). Changes in insurance coverage have correlated with changes in healthcare utilization and reported ASD prevalence. Durkin and Wolfe (2020) reported that the ASD prevalence rate temporarily plateaued during the 2008 recession, when many children lost their insurance coverage as parents lost their jobs. Conversely, as rates of insurance coverage increased among individuals with severe psychological distress between 2011 and 2016, fewer individuals reported delaying necessary care, forgoing care, and being unable to afford mental health care (Novak et al., 2018). As rates of insurance coverage increased in the general population between 2006 and 2014, a greater percent of Americans reported visiting a physician in the past year, although the percent of Americans who reported visiting a mental health provider in the past year stayed constant (Manuel, 2018).

Various other policies included in or related to the ACA may have increased the rate of ASD diagnosis, especially among marginalized populations. First, the ACA prevented insurers from denying coverage to patients with preexisting conditions, including ASD. Similarly, autism mandates have been enacted across all 50 US states between 2001 and 2020, requiring private insurers to expand coverage for ASD on a state-by-state basis (Choi et al., 2020). Policy changes also resulted in increased access to ASD-specific health services. Some states expanded access to home care services for children with ASD in the 2000s and 2010s using federal 1915(c) waivers (Velott et al., 2016). Then, the ACA mandated that private insurers cover the AAP-recommended ASD screenings at 18 months and 24 months of age without charging copays (US Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.). Furthermore, the ACA enabled many states to undergo Medicaid expansion, resulting in a significant increase in healthcare providers qualified to treat ASD in these states (McBain et al., 2022). Finally, the ACA helped address inequities in coverage for mental health services by strengthening the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (MHPAEA), which has been associated with improvements in access to ASD-specific services covered by insurance (Stuart et al., 2017).

Changes to immigration policy in the US likely also played a role in the racial repatterning of ASD prevalence. Fountain & Bearman (2011) argue that rates of ASD diagnosis among Hispanic children in California increased most rapidly when national policy was favorable to immigrants and rates of deportation of noncitizens from the US stayed constant. ASD diagnosis rates among Hispanics in California plateaued when policy changes like Proposition 187 drove increased deportations of noncitizens. Rates of apprehension, removal, return, and/or expulsion of noncitizens in the US steadily decreased between 2000 and 2015 but have been increasing since 2015 (US Department of Homeland Security, 2022). It is possible that the increased nationwide ASD prevalence among Hispanic children is related to decreasing rates of deportation of noncitizens in the 2000s and the scientific community has yet to detect the impact of increasing deportations since 2015 on ASD diagnosis rates and racial patterning.

Increased parental education has also been associated with a higher likelihood of ASD diagnosis (Croen et al., 2002b; Dickerson et al., 2017; King & Bearman, 2011). A few qualitative studies suggest that cultural factors such as stigma and lack of awareness may contribute to racial differences in ASD diagnosis (Cohen & Miguel, 2018; Dababnah et al., 2018; Ijalba, 2016; Zuckerman et al., 2014), but no US-based epidemiological studies have collected data on how cultural factors vary between race groups and how this has changed over time. As knowledge of racial differences in ASD prevalence has become widespread, various initiatives have cropped up to combat stigma and increase cultural awareness of ASD in minority communities (Dufour et al., 2021; Kamali et al., 2022; Kang-Yi et al., 2018). It is possible that cultural changes have contributed to the racial repatterning of ASD prevalence by encouraging more parents from minority race groups to follow up on ASD screening referrals. More research is needed to determine if the culture around ASD in minority race groups has changed and whether this is affecting reported ASD prevalence.

The patterning of ASD prevalence by neighborhood wealth has shifted throughout the US, and this shift may impact racial differences in ASD prevalence. In California, neighborhood wealth correlated with overall likelihood of ASD diagnosis before 1994 but only correlated with likelihood of ASD diagnosis among public insurance recipients from 1994 to 2000 (King & Bearman, 2011). County wealth was positively related to ASD prevalence among White children in California before 2000 but negatively related to ASD prevalence among White children after 2000 (Nevison & Parker, 2020). Similarly, parental college education and private insurance used to be associated with higher likelihood of ASD diagnosis in California, but these patterns flipped in 2009 and 2011, respectively. Californian children with public insurance and poorly educated parents are now more likely to be diagnosed with ASD than children with private insurance and well-educated parents (Winter et al., 2020). Likewise, ADDM data from the 1994 to 2002 birth cohorts suggests that ASD prevalence was higher in wealthy neighborhoods nationwide (Durkin et al., 2017), while ADDM data from the 2010 and 2012 birth cohorts concludes that neighborhood wealth had no effect on ASD prevalence (Maenner et al., 2021, 2023). Black and Hispanic Americans are more likely to live in low-income neighborhoods than White and Asian Americans (Reardon et al., 2015), and Black and Hispanic Californians are more likely to lack a college education (Hawkins, 2022) and private insurance (Finocchio et al., 2021). Therefore, the decreasing impact of neighborhood wealth on ASD prevalence along with the increasing rate of ASD diagnosis among Californians lacking a college education and private insurance may contribute to increasing ASD rates among Black and Hispanic children.

This review is limited by the heterogeneity of diagnostic criteria for autism across studies. Of the eighteen studies in this review, fourteen used either ASD or enrollment in special education services for their diagnostic criteria, one used only ASD, one used only enrollment in special education services, one used only autistic disorder, and one used autistic disorder before 2014 and ASD after 2014. ASD and PDD are equivalent diagnoses in the DSM-5 and DSM-IV, respectively, while autistic disorder is a narrower diagnosis in the DSM-IV that excludes most ASD cases. Criteria for enrollment in special education services under IDEA align closely, but not perfectly, with the DSM-5 definition of ASD. The USDOE defines autism as “a developmental disability significantly affecting verbal and nonverbal communication and social interaction, generally evident before age 3 that adversely affects a child’s educational performance” (US Department of Education, 2017). State governments can amend the USDOE definition of ASD to best serve their school districts. Therefore, enrollment in special education services for ASD isn’t always equivalent to ASD diagnosis (Sullivan, 2013).

In addition, this review is limited by discrepancies in how each study defines race groups. Two studies have a general White race group, while fifteen specify non-Hispanic White. Four studies have a general Black race group, while thirteen specify non-Hispanic Black. Fifteen studies have a general Hispanic race group, while one specifies Hispanic White and one lacks a Hispanic category. Two studies have a specific Asian race group, nine group together Asian and Pacific Islander (API) children, and six, including all ADDM reports before 2002, lack an Asian category. Only two studies include a group for AI/AN, and only one study includes a group for children of two or more races. Variations in sample size between race groups also affect the integrity of the data: in the 2008 and 2010 ADDM birth cohorts, the confidence interval for ASD prevalence among API children is so large that it overlaps with the confidence intervals for every other race group included (Maenner et al., 2020, 2021). Data from international epidemiological studies further suggest that race is socially constructed, so discussion of disease prevalence by race group reflects the structure and norms of the culture that conceptualized the race groups (Fairthorne et al., 2017; Raz et al., 2015; Roman-Urrestarazu et al., 2021; Segev et al., 2019).

The pattern of ASD prevalence in the US has fundamentally changed in recent years. ASD, which had been most prevalent among White children in the 1990s and early 2000s, is now more prevalent among Black, Hispanic, & API children. These results complement existing research on racial disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of ASD and raise important questions for future epidemiological studies on the relationship between ASD prevalence and race, ethnicity, social class, and socioeconomic status.

Many sociocultural and regulatory factors could have contributed to the rise in reported ASD prevalence among minority groups in the US. Younger age of diagnosis, increased education and wealth, and enhanced insurance coverage among Black and Hispanic families have significantly impacted the racial patterning of ASD prevalence in the US. At the same time, healthcare providers may be disproportionately over-diagnosing ASD in Black and Hispanic children in an effort to improve access to care. Despite the limitations in interpreting findings from studies with heterogeneous methods and outcome classifications, there is adequate consistency across studies to suggest a clear shift, where ASD prevalence among Black, Hispanic, & API children in the US born after 2010 surpassed that of White children.

Given that race is culturally defined and varies depending on social norms, the implications of this shift in prevalence are challenging to fully understand. Race often acts as a proxy for variables like genetics, access to healthcare resources, and exposure to racism. There is a need for future rigorous epidemiological studies on the genetic, sociocultural, and economic drivers of trends in ASD prevalence that include population samples representative of the racial diversity of the US population.

References

Akinhanmi, M. O., Biernacka, J. M., Strakowski, S. M., McElroy, S. L., Berry, B., Merikangas, J. E., Assari, K. R., McInnis, S., Schulze, M. G., LeBoyer, T. G., Tamminga, M., Patten, C., C., & Frye, M. A. (2018). Racial disparities in bipolar disorder treatment and research: A call to action. Bipolar Disorders, 20(6), 506–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12638.

American Psychiatric Association (1987). Pervasive Developmental Disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd edition-revised (DSM-III-R)).

American Psychological Association (2000). Pervasive Developmental Disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition-text revision (DSM-IV-TR), pp. 69–70).

American Psychological Association (2013). Autism Spectrum Disorder. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). https://www.apa.org/topics/autism-spectrum-disorder.

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Pervasive Developmental Disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.).

American Psychiatric Association (1980). Pervasive Developmental Disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed.).

Artiga, S., Hill, L., & Damico, A. (2022, December 20). Health Coverage by Race and Ethnicity, 2010–2021. KFF. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity/.

Aylward, B. S., Gal-Szabo, D. E., & Taraman, S. (2021). Racial, ethnic, and Sociodemographic Disparities in diagnosis of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 42(8), 682–689. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000996.

Azim, A., Rdesinski, R. E., Phelps, R., & Zuckerman, K. E. (2020). Nonclinical factors in Autism diagnosis: Results from a National Health Care Provider Survey. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 41(6), 428–435. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000797.

Bailey, A., Le Couteur, A., Gottesman, I., Bolton, P., Simonoff, E., Yuzda, E., & Rutter, M. (1995). Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: Evidence from a British twin study. Psychological Medicine, 25(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291700028099.

Baio, J. (2012). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum disorders—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 61(SS03), 1–19.

Baio, J. (2014). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 63(SS02), 1–21.

Baio, J., Wiggins, L., Christensen, D. L., Maenner, M. J., Daniels, J., Warren, Z., Kurzius-Spencer, M., Zahorodny, W., Rosenberg, R., White, C., Durkin, T., Imm, M. S., Nikolaou, P., Yeargin-Allsopp, L., Lee, M., Harrington, L. C., Lopez, R., Fitzgerald, M., Hewitt, R. T., & Dowling, A., N. F (2018). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 67(6), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1.

Bayne, J., Garry, J., & Albert, M. A. (2023). Brief review: Racial and ethnic disparities in Cardiovascular Care with a focus on congenital heart Disease and Precision Medicine. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 25(5), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-023-01093-3.

Brasher, S., Stapel-Wax, J. L., & Muirhead, L. (2022). Racial and ethnic disparities in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Implications for care. Nursing Clinics of North America, 57(3), 489–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2022.04.014.

Braun, K. V. N., Christensen, D., Doernberg, N., Schieve, L., Rice, C., Wiggins, L., Schendel, D., & Yeargin-Allsopp, M. (2015). Trends in the prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, intellectual disability, and Vision Impairment, Metropolitan Atlanta, 1991–2010. PLOS ONE, 10(4), e0124120. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0124120.

Chakrabarti, S., & Fombonne, E. (2005). Pervasive Developmental disorders in Preschool Children: Confirmation of high prevalence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(6), 1133–1141. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1133.

Choi, K. R., Knight, E. A., Stein, B. D., & Coleman, K. J. (2020). Autism Insurance mandates in the US: Comparison of Mandated Commercial Insurance Benefits across States. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24(7), 894–900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-020-02950-2.

Christensen, D. L., Baio, J., Braun, K. V. N., Bilder, D., Charles, J., Constantino, J. N., Daniels, J., Durkin, M. S., Fitzgerald, R. T., Kurzius-Spencer, M., Lee, L. C., Pettygrove, S., Robinson, C., Schulz, E., Wells, C., Wingate, M. S., Zahorodny, W., & Yeargin-Allsopp, M. (2016). Prevalence and characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 65(3), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6503a1.

Christensen, D. L., Maenner, M. J., Bilder, D., Constantino, J. N., Daniels, J., Durkin, M. S., Fitzgerald, R. T., Kurzius-Spencer, M., Pettygrove, S. D., Robinson, C., Shenouda, J., White, T., Zahorodny, W., Pazol, K., & Dietz, P. (2019). Prevalence and characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder among children aged 4 years—early Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, Seven Sites, United States, 2010, 2012, and 2014. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 68(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6802a1.

Cohen, S. R., & Miguel, J. (2018). Amor and Social Stigma: ASD beliefs among immigrant Mexican parents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(6), 1995–2009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3457-x.

Cook, B. L., Trinh, N. H., Li, Z., Hou, S. S. Y., & Progovac, A. (2017). Trends in racial-ethnic disparities in Access to Mental Health Care, 2004–2012. Psychiatric Services, 68(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500453.

Croen, L. A., Grether, J. K., Hoogstrate, J., & Selvin, S. (2002). The changing prevalence of Autism in California. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32(3), 207–215.

Croen, L. A., Grether, J. K., & Selvin, S. (2002b). Descriptive epidemiology of Autism in a California Population: Who is at risk? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32(3), 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015405914950.

Dababnah, S., Shaia, W. E., Campion, K., & Nichols, H. M. (2018). We had to keep pushing: Caregivers’ perspectives on Autism Screening and Referral Practices of Black Children in Primary Care. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 56(5), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-56.5.321.

Dickerson, A. S., & Dickerson, A. S. (2018). Brief report: Texas School District Autism Prevalence in Children from Non-english-speaking homes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(4), 1411–1417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3676-9.

Dickerson, A. S., Rahbar, M. H., Pearson, D. A., Kirby, R. S., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Harrington, R. A., Pettygrove, S., Zahorodny, W. M., MoyéIII, L. A., Durkin, M., & Slay Wingate, M. (2017). Autism spectrum disorder reporting in lower socioeconomic neighborhoods. Autism, 21(4), 470–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316650091.

Dufour, B. D., Albores-Gallo, L., Luna‐Muñoz, J., Hagerman, R., Miquelajauregui, A., Buriticá, E., Saldarriaga, W., Pacheco‐Herrero, M., Silvestre‐Sosa, Y., Mazefsky, A., Gastgeb, C., Kofler, H., Casanova, J., Hof, M., London, P. R., Hagerman, E., P., & Martínez‐Cerdeño, V. (2021). Hispano‐American Brain Bank on Neurodevelopmental disorders: An initiative to promote brain banking, research, education, and outreach in the field of neurodevelopmental disorders. Brain Pathology, 32(2), e13019. https://doi.org/10.1111/bpa.13019.

Durkin, M. S., & Wolfe, B. L. (2020). Trends in Autism Prevalence in the U.S.: A Lagging Economic Indicator? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(3), 1095–1096. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04322-4.

Durkin, M. S., Maenner, M. J., Baio, J., Christensen, D., Daniels, J., Fitzgerald, R., Imm, P., Lee, L. C., Schieve, L. A., Van Naarden Braun, K., Wingate, M. S., & Yeargin-Allsopp, M. (2017). Autism spectrum disorder among US children (2002–2010): Socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 107(11), 1818–1826. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304032.

Education of the Handicapped Act Amendments of (1990). Pub. L. No. 101–476, 1103 (1990).

Fairthorne, J., de Klerk, N., Leonard, H. M., Schieve, L. A., & Yeargin-Allsopp, M. (2017). Maternal Race–Ethnicity, immigrant status, Country of Birth, and the odds of a child with autism. Child Neurology Open, 4, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329048X16688125.

Finocchio, L., Paci, J., & Newman, M. (2021). Medi-Cal facts and figures, 2021: Essential source of Coverage for millions. California Health Care Almanac, California Health Care Foundation.

Garb, H. N. (2021). Race bias and gender bias in the diagnosis of psychological disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 90, 102087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102087.

Garrett, W. S., Verma, A., Thomas, D., Appel, J. M., & Mirza, O. (2023). Racial disparities in Psychiatric Decisional Capacity consultations. Psychiatric Services (Washington D C), 74(1), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202100685.

Hansen, S. N., Schendel, D. E., & Parner, E. T. (2015). Explaining the increase in the prevalence of Autism Spectrum disorders the proportion attributable to changes in reporting practices. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(1), 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1893.

Hawkins, J. (2022, February 23). Young Adult College Attainment in California. Berkeley Institute for Young Americans. https://youngamericans.berkeley.edu/2022/02/young-adult-college-attainment-in-california/.

Hertz-Picciotto, I., & Delwiche, L. (2009). The rise in Autism and the role of age at diagnosis. Epidemiology (Cambridge Mass), 20(1), 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181902d15.

Hilton, C. L., Fitzgerald, R. T., Jackson, K. M., Maxim, R. A., Bosworth, C. C., Shattuck, P. T., Geschwind, D. H., & Constantino, J. N. (2009). Brief report: Under-representation of African americans in Autism Genetic Research: A rationale for inclusion of subjects representing Diverse Family structures. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(5), 633–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0905-2.

Ijalba, E. (2016). Hispanic immigrant mothers of Young Children with Autism Spectrum disorders: How do they understand and cope with autism? American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 25(2), 200–213.

Jarquin, V. G., Wiggins, L. D., Schieve, L. A., & Van Naarden-Braun, K. (2011). Racial disparities in Community Identification of Autism Spectrum disorders over Time; Metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia, 2000–2006. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 32(3), 179. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e31820b4260.

Johnson, C. P., Myers, S. M., & The Council on Children With Disabilities. (2007). Identification and evaluation of children with Autism Spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 120(5), 1183–1215. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-2361.

Kamali, M., Sivapalan, S., Kata, A., Kim, N., Shanmugalingam, N., Duku, E., Zwaigenbaum, L., & Georgiades, S. (2022). Program evaluation of a pilot mobile developmental outreach clinic for autism spectrum disorder in Ontario. BMC Health Services Research, 22, 426. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07789-7.

Kang-Yi, C. D., Grinker, R. R., Beidas, R., Agha, A., Russell, R., Shah, S. B., Shea, K., & Mandell, D. S. (2018). Influence of Community-Level Cultural beliefs about autism on families’ and professionals’ care for children. Transcultural Psychiatry, 55(5), 623–647. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461518779831.

Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2(3), 217–250.

King, M. D., & Bearman, P. S. (2011). Socioeconomic status and the increased prevalence of Autism in California. American Sociological Review, 76(2), 320–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122411399389.

Leonard, H., Glasson, E., Nassar, N., Whitehouse, A., Bebbington, A., Bourke, J., Jacoby, P., Dixon, G., Malacova, E., Bower, C., & Stanley, F. (2011). Autism and intellectual disability are differentially related to Sociodemographic background at Birth. Plos One, 6(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017875.

Lewsey, S. C., & Breathett, K. (2021). Racial and ethnic disparities in Heart failure. Current Opinion in Cardiology, 36(3), 320–328. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCO.0000000000000855.

Lord, C., Risi, S., DiLavore, P. S., Shulman, C., Thurm, A., & Pickles, A. (2006). Autism from 2 to 9 years of age. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(6), 694–701. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.694.

Lotter, V. (1966). Epidemiology of autistic conditions in young children. Social Psychiatry, 1(3), 124–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00584048.

Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Baio, J., Washington, A., Patrick, M., DiRienzo, M., Christensen, D. L., Wiggins, L. D., Pettygrove, S., Andrews, J. G., Lopez, M., Hudson, A., Baroud, T., Schwenk, Y., White, T., Rosenberg, C. R., Lee, L. C., Harrington, R. A., Huston, M., & Dietz, P. M. (2020). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 69(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6904a1.

Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Durkin, M. S., Esler, A., Furnier, S. M., Hallas, L., Hall-Lande, J., Hudson, A., Hughes, M. M., Patrick, M., Pierce, K., Poynter, J. N., Salinas, A., Shenouda, J., Vehorn, A., Warren, Z., Constantino, J. N., & Cogswell, M. E. (2021). Prevalence and characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 70(11), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7011a1.

Maenner, M. J., Warren, Z., Williams, A. R., Amoakohene, E., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Durkin, M. S., Fitzgerald, R. T., Furnier, S. M., Hughes, M. M., Ladd-Acosta, C. M., McArthur, D., Pas, E. T., Salinas, A., Vehorn, A., Williams, S., Esler, A., Grzybowski, A., Hall-Lande, J., & Shaw, K. A. (2023). Prevalence and characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 72(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7202a1.

Mandell, D. S., Listerud, J., Levy, S. E., & Pinto-Martin, J. A. (2002). Race differences in the age at diagnosis among Medicaid-Eligible Children with Autism. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(12), 1447–1453. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200212000-00016.

Mandell, D. S., Ittenbach, R. F., Levy, S. E., & Pinto-Martin, J. A. (2007). Disparities in diagnoses received prior to a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(9), 1795–1802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0314-8.

Mandell, D. S., Wiggins, L. D., Carpenter, L. A., Daniels, J., DiGuiseppi, C., Durkin, M. S., Giarelli, E., Morrier, M. J., Nicholas, J. S., Pinto-Martin, J. A., Shattuck, P. T., Thomas, K. C., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., & Kirby, R. S. (2009). Racial/Ethnic disparities in the identification of children with Autism Spectrum disorders. American Journal of Public Health, 99(3), 493–498. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.131243.

Manuel, J. I. (2018). Racial/Ethnic and gender disparities in Health Care Use and Access. Health Services Research, 53(3), 1407–1429. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12705.

Mazumdar, S., Winter, A., Liu, K. Y., & Bearman, P. (2013). Spatial clusters of autism births and diagnoses point to contextual drivers of increased prevalence. Social Science & Medicine, 95, 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.032.

McBain, R. K., Cantor, J. H., Kofner, A., Stein, B. D., & Yu, H. (2022). Medicaid Expansion and Growth in the workforce for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(4), 1881–1889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05044-2.

National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (2022, September 30). Overview. https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/.

Nevison, C., & Parker, W. (2020). California Autism Prevalence by County and Race/Ethnicity: Declining Trends among Wealthy whites. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(11), 4011–4021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04460-0.

Nevison, C., & Zahorodny, W. (2019). Race/Ethnicity-Resolved Time trends in United States ASD prevalence estimates from IDEA and ADDM. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(12), 4721–4730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04188-6.

Nichols, H. M., Dababnah, S., Troen, B., Vezzoli, J., Mahajan, R., & Mazefsky, C. A. (2020). Racial disparities in a sample of Inpatient Youth with ASD. Autism Research, 13(4), 532–538. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2262.

Novak, P., Anderson, A. C., & Chen, J. (2018). Changes in Health Insurance Coverage and barriers to Health Care Access among individuals with serious psychological distress following the Affordable Care Act. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 45(6), 924–932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-018-0875-9.

Olbert, C. M., Nagendra, A., & Buck, B. (2018). Meta-analysis of Black vs. White racial disparity in schizophrenia diagnosis in the United States: Do structured assessments attenuate racial disparities? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(1), 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000309.

Owen, C. M., Goldstein, E. H., Clayton, J. A., & Segars, J. H. (2013). Racial and ethnic Health disparities in Reproductive Medicine: An evidence-based overview. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 31(5), 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1348889.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj, 71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Pedersen, A., Pettygrove, S., Meaney, F. J., Mancilla, K., Gotschall, K., Kessler, D. B., Grebe, T. A., & Cunniff, C. (2012). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum disorders in hispanic and non-hispanic White children. Pediatrics, 129(3), e629–e635. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1145.

Pham, A. V., & Charles, L. C. (2023). Racial disparities in Autism diagnosis, Assessment, and intervention among Minoritized Youth: Sociocultural Issues, factors, and Context. Current Psychiatry Reports, 25(5), 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-023-01417-9.

Pham, H. H., Sandberg, N., Trinkl, J., & Thayer, J. (2022). Racial and ethnic differences in Rates and Age of diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. JAMA Network Open, 5(10), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.39604.

Ramaswami, G., & Geschwind, D. H. (2018). Chapter 21—Genetics of autism spectrum disorder. In H. L. Paulson & C. Klein (Eds.), Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Neurogenetics, Part I (Vol. 147, pp. 321–329). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63233-3.00021-X.

Raz, R., Weisskopf, M. G., Davidovitch, M., Pinto, O., & Levine, H. (2015). Differences in Autism Spectrum disorders incidence by sub-populations in Israel 1992–2009: A total Population Study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(4), 1062–1069. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2262-z.

Reardon, S. F., Fox, L., & Townsend, J. (2015). Neighborhood Income Composition by Household Race and Income, 1990–2009. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 660(1), 78–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716215576104.

Rice, C. (2007). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum disorders—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, Six sites, United States, 2000. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 56(SS01), 1–11.

Rice, C. (2009). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum disorders—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, United States, 2006. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 58(SS10), 1–20.

Richardson, L. D., Irvin, B., C., & Tamayo-Sarver, J. H. (2003). Racial and ethnic disparities in the clinical practice of Emergency Medicine. Journal of Academic Emergency Medicine, 10(11), 1184–1188. https://doi.org/10.1197/S1069-6563(03)00487-1.

Roman-Urrestarazu, A., van Kessel, R., Allison, C., Matthews, F. E., Brayne, C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2021). Association of Race/Ethnicity and Social Disadvantage with Autism Prevalence in 7 million School Children in England. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(6), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.0054.

Sanchack, K. E., & Thomas, C. A. (2016). Autism spectrum disorder: Primary Care principles. American Family Physician, 94(12), 972–979A.

Segev, A., Weisskopf, M. G., Levine, H., Pinto, O., & Raz, R. (2019). Incidence Time trends and socioeconomic factors in the observed incidence of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Israel: A Nationwide Nested case–control study. Autism Research, 12(12), 1870–1879. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2185.

Shaw, K. A., Maenner, M. J., Baio, J., Washington, A., Christensen, D. L., Wiggins, L. D., Pettygrove, S., Andrews, J. G., White, T., Rosenberg, C. R., Constantino, J. N., Fitzgerald, R. T., Zahorodny, W., Shenouda, J., Daniels, J. L., Salinas, A., Durkin, M. S., & Dietz, P. M. (2020). Early identification of Autism Spectrum Disorder among children aged 4 years—early Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, Six sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 69(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6903a1.

Shaw, K. A., Williams, S., Hughes, M. M., Warren, Z., Bakian, A. V., Durkin, M. S., Esler, A., Hall-Lande, J., Salinas, A., Vehorn, A., Andrews, J. G., Baroud, T., Bilder, D. A., Dimian, A., Galindo, M., Hudson, A., Hallas, L., Lopez, M., Pokoski, O., & Maenner, M. J. (2023). Statewide county-level autism spectrum disorder prevalence estimates—seven U.S. states, 2018. Annals of Epidemiology, 79, 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2023.01.010.

Steffenburg, S., Gillberg, C., Hellgren, L., Andersson, L., Gillberg, I. C., Jakobsson, G., & Bohman, M. (1989). A twin study of autism in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 30(3), 405–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00254.x.

Sterne, J., Hernan, M., McAleenan, A., Reeves, B., & Higgins, J. (2023). Chapter 25: Assessing risk of bias in a non-randomized study. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (6.4). Cochrane. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-25#section-25-3.

Sullivan, A. L. (2013). School-based autism identification: Prevalence, racial disparities, and systemic correlates. School Psychology Review, 42(3), 298–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2013.12087475.

US Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). The Affordable Care Act and Autism and Related Conditions [Text]. Retrieved August 9 (2023). from https://www.hhs.gov/programs/topic-sites/autism/aca-and-autism/index.html.

US Department of Education (2017, May 2). Section 300.8 (c) (1). Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/a/300.8/c/1/.

US Department of Homeland Security. (2022). 2021 Yearbook of Immigration statistics. Office of Immigration Statistics.

Valicenti-McDermott, M., Hottinger, K., Seijo, R., & Shulman, L. (2012). Age at diagnosis of Autism Spectrum disorders. The Journal of Pediatrics, 161(3), 554–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.05.012.

Velott, D. L., Agbese, E., Mandell, D., Stein, B. D., Dick, A. W., Yu, H., & Leslie, D. L. (2016). Medicaid 1915(c) home and community based services waivers for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 20(4), 473–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315590806.

Ventura, A. M. B., Hayes, R. D., & de Fonseca, D. (2022). Ethnic disparities in clozapine prescription for service-users with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 52(12), 2212–2223. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722001878.

Volkmar, F. R., Bregman, J., Cohen, D. J., & Cicchetti, D. V. (1988). DSM-III and DSM-III-R diagnoses of Autism. American Journal of Psychiatry, 145(11), 1404–1408. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.145.11.1404.

Wazana, A., Bresnahan, M., & Kline, J. (2007). The Autism Epidemic: Fact or Artifact? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(6), 721–730. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e31804a7f3b.

Winter, A. S., Fountain, C., Cheslack-Postava, K., & Bearman, P. S. (2020). The social patterning of autism diagnoses reversed in California between 1992 and 2018. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(48), 30295–30302. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2015762117.

Zeidan, J., Fombonne, E., Scorah, J., Ibrahim, A., Durkin, M. S., Saxena, S., Yusuf, A., Shih, A., & Elsabbagh, M. (2022). Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Research, 15(5), 778–790.

Zuckerman, K. E., Sinche, B., Cobian, M., Cervantes, M., Mejia, A., Becker, T., & Nicolaidis, C. (2014). Conceptualization of Autism in the latino community and its relationship with early diagnosis. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 35(8), 522–532. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000091.

Zwaigenbaum, L., Bauman, M. L., Fein, D., Pierce, K., Buie, T., Davis, P. A., Newschaffer, C., Robins, D. L., Wetherby, A., Choueiri, R., Kasari, C., Stone, W. L., Yirmiya, N., Estes, A., Hansen, R. L., McPartland, J. C., Natowicz, M. R., Carter, A., Granpeesheh, D., & Wagner, S. (2015). Early screening of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Recommendations for practice and research. Pediatrics, 136(Suppl 1), S41–S59. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-3667D.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Beatrice and Samuel A. Seaver Foundation (AR; AK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

AK is on the Advisory Board for the Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation, Ovid Therapeutics, David Lynch Foundation, ADNP Kids Research Foundation, and Ritrova Therapeutics and consults to Acadia, Alkermes, Jaguar Therapeutics, GW Pharmaceuticals, Neuren Pharmaceuticals, Clinilabs Drug Development Corporation, Scioto Biosciences, and Biogen. The remaining authors have no potential conflict of interests related to this publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gallin, Z., Kolevzon, A.M., Reichenberg, A. et al. Racial Differences in the Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. J Autism Dev Disord (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-024-06403-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-024-06403-5