Abstract

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and epilepsy represent a comorbidity that negatively influences the proper development of linguistic competencies, particularly in receptive language, in the pediatric population. This group displays impairments in the auditory comprehension of both simple and complex grammatical structures, significantly limiting their performance in language-related activities, hampering their integration into social contexts, and affecting their quality of life. The main objective of this study was to assess auditory comprehension of grammatical structures in individuals with ASD and epilepsy and compare the results among the three groups. A non-experimental cross-sectional study was designed, including a total of 170 participants aged between 7 and 9 years, divided into three groups: a group with ASD, a group with epilepsy, and a comorbid group with both ASD and epilepsy (ASDEP). The comprehension of grammatical structures was assessed using the CEG and CELF-5 instruments. Statistical analyses included MANOVA and ANOVA to compare scores between groups to verify associations between study variables. The results indicate that the group with ASD and epilepsy performed worse compared to the ASD and epilepsy-only groups, respectively. Additionally, a significant and directly proportional association was observed among all variables within the measures of grammatical structure comprehension. The neurological damage caused by epilepsy in the pediatric population with ASD leads to difficulties in understanding oral language. This level of functioning significantly limits the linguistic performance of these children, negatively impacting their quality of life and the development of core language skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The pediatric population with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and comorbid neurological conditions such as epilepsy exhibits a highly heterogeneous linguistic profile (Wiklund & Laakso, 2021). Deficits in language skills represent one of the most relevant factors determining the clinical severity of children with ASD (Hirota & King, 2023). However, when an individual with ASD also presents with epilepsy, competencies in expressive and receptive language manifest greater difficulty compared to when only one of these two disorders is present (Braconnier & Siper, 2021). Linguistic alterations in children with ASD and epilepsy can be described as a highly variable continuum, where on one hand, there are minimally verbal children (Tuchman et al., 2010) or those who do not acquire verbal language (in variable percentages of up to 50% according to different studies), and on the other hand, there are children with a level of linguistic form development that can be considered appropriate (Duffy et al., 2013), but pragmatically inadequate (Roberts et al., 2008). Within this spectrum, highly variable profiles of linguistic development can be found (Mukherjee, 2017), with children exhibiting mild language delay (Davidson & Weismer, 2017), children with severe language disorders (Eigsti et al., 2015), and those who, despite reaching their early development milestones, such as first word production or usage between 12 and 18 months, subsequently experience stagnation or regression in their language development (Ricketts, 2011).

Although communication and language in children with ASD have been extensively researched (Davidson et al., 2018; Naigles, 2013; Torrens & Ruiz, 2021), when this disorder is accompanied by epilepsy, the nature and characteristics of language deficits become an evident issue that requires further investigation (Cano-Villagrasa et al., 2023). For instance, according to the DSM-5 (APA, 2013), ASD exhibits significant alterations in the pragmatic-social dimension of expressive language. Its diagnostic criteria emphasize difficulties in establishing functional conversations and interacting with the environment, particularly in contexts where linguistic demands on the individual with ASD are higher. However, the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria do not provide a detailed description of the linguistic alterations that a child with a diagnosis of both ASD and epilepsy might present. Some authors consider ASD and epilepsy as potentially comorbid conditions (Ali, 2018; Ricketts, 2011; Tran et al., 2020) and suggest that these clinical profiles are associated with more pronounced disruptions in expressive language development (Eigsti et al., 2015). These disruptions include difficulties in phonological, semantic, morphosyntactic, and pragmatic functioning, in addition to receptive language impairments involving comprehension and following complex instructions with multiple elements (Saban-Bezalel & Mashal, 2019).

Delving into linguistic competencies related to language comprehension, most published studies report that in ASD and epilepsy, receptive language is more affected than expressive language (Asberg, 2010; Henry & Solari, 2020). However, this finding has not been fully confirmed (Roemer et al., 2019). Furthermore, the question of the discrepancy between receptive and expressive competencies is still unclear in terms of whether it should be considered a potential marker of ASD (Saban-Bezalel & Mashal, 2015) or if both receptive and expressive language difficulties are comorbid with ASD and epilepsy (Cano-Villagrasa et al., 2023).

Difficulties in language comprehension in children with ASD and epilepsy are part of a broad and complex spectrum characterized by pragmatic deficits (Eberhardt & Nadig, 2018) and executive functioning impairments that can affect verbal comprehension (Asberg et al., 2010). According to Tager-Flusberg et al. (2009), language comprehension problems in the presence of this comorbidity are particularly evident in everyday situations rather than during single-word comprehension tasks. Children with ASD and epilepsy have impairments in their ability to decode relevant contextual cues and deficits in social attention (Svindt & Surányi, 2021), while typically developing children can identify or select salient sensory and social stimuli relevant for both comprehension and communication from an early age (Boucher, 2012).

Grammatical comprehension, as a specific receptive language skill required to decode verbal messages in interactions (Naigles & Tovar, 2012), represents a crucial research target in the field of ASD and epilepsy (Kalandadze et al., 2022). However, it is worth noting that few studies assess the comprehension of individuals with ASD and epilepsy through specific tasks that evaluate differences in their grammatical comprehension skills.

Several research findings suggest that syntactic deficits are apparent across individuals on the spectrum, including among older adolescents with ASD and epilepsy who have average or above-average cognitive abilities (Eigsti & Bennetto, 2007; Gonzalez-Barrero & Nadig, 2019; Loukusa et al., 2014). However, syntactic deficits tend to be localized rather than global and vary among individuals with ASD and epilepsy. For instance, some children with these two disorders display deficiencies in the comprehension of past tense verbs (Kelley et al., 2006), while others exhibit alterations in morpheme comprehension (Tovar et al., 2015). Similar to the semantic component, research suggests variability in syntactic language skills exhibited by individuals with ASD and epilepsy (Eigsti & Bennetto, 2007).

Some authors hypothesize that this variability can be explained by cognitive abilities and the severity of symptoms in ASD and epilepsy, as individuals with these conditions show deficits in syntactic language (Roberts et al., 2010; Shulman & Guberman, 2007). However, other authors have found that even among individuals with ASD and epilepsy who have better cognitive abilities, most still demonstrate specific syntactic deficits, such as the use of simplified phrases, limitations in the comprehension of complex grammatical structures, and challenges with verb tense conjugation and inflection (Eigsti & Bennetto, 2007; Kelley et al., 2006).

The discrepancy in findings likely reflects the interplay between ASD and epilepsy, as several studies have reported that this population experiences difficulties in comprehending grammatical structures related to passive voice or those with a high degree of inferential content (Roberts et al., 2010; Shulman & Guberman, 2007). Given the limited literature examining the comprehension of morphosyntactic structures in the pediatric population with ASD and epilepsy, along with methodological limitations in research in this area, there is a need to expand research in this domain to gain a better understanding of syntactic language in these disorders and the influence of syntactic language skills on other aspects of psychosocial functioning for children with ASD and epilepsy.

Therefore, the assessment of receptive skills in children with ASD and epilepsy is of crucial clinical importance for defining their language profile more clearly (Ge et al., 2023). It is considered a fundamental prognostic marker for the development of linguistic competencies (Garrido et al., 2015). In fact, children with ASD and epilepsy who have minimal ability to emit verbal information and communication exhibit greater severity of autistic symptoms and overall worse clinical outcomes (Baixauli et al., 2020) than those with only one of the two disorders, for whom the outcome might be more satisfactory (Venker et al., 2016).

For these reasons, the main objective of this study was to evaluate competencies in the comprehension of grammatical structures in the Spanish language in a group of minors diagnosed with ASD and epilepsy. Additionally, a series of specific objectives were established, including: (I) comparing performance in grammatical structure comprehension tasks, and (II) examining the relationship between the sub-scales of grammatical structure comprehension among the three participant groups. Based on the empirical evidence in the scientific literature, it was hypothesized in this study that participants diagnosed with both ASD and epilepsy would perform worse in comprehension tasks compared to the group diagnosed with ASD, followed by the group composed of individuals diagnosed with epilepsy.

Method

Participants

All participants diagnosed with ASD or epilepsy underwent evaluation in the Mental Health Unit and Pediatric Neurology service attached to their medical reference center by a multidisciplinary professional team. In these centers, a diagnostic screening assessment was conducted using the M-CHAT-R questionnaire (Robins et al., 2004). Children who scored in a way that raised suspicion underwent the ADOS-2 (Lord et al., 2008) and ADI-R (Rutter et al., 2006) protocols to confirm the diagnostic suspicion of ASD. Additionally, participants received a neurological evaluation from the neuropediatric team, which included a neurological assessment using Magnetic Resonance Imaging, sleep-deprived Electroencephalogram, and genetic tests to help confirm the diagnosis.

Finally, the following inclusion and exclusion criteria were established. Inclusion criteria were: (I) being between 7 and 9 years old, (II) having a diagnosis of ASD issued by a public hospital or health center, and (III) undergoing rehabilitation treatment at the rehabilitation clinic. Exclusion criteria were: (I) having any motor or sensory disease or disorder that hinders or prevents proper study performance, (II) not exhibiting any communication or language by 5 years of age, and (III) having mild, moderate, severe, or profound intellectual disability or an IQ score below 75 as measured by the WISC-V test (Wechsler, 2015).

Instruments and Materials

“CEG. Test de Compresión de Estructuras Gramaticales”

The CEG. Test de Comprensión de Estructuras Gramaticales (CEG; Mendoza et al., 2005) is an assessment instrument that measures the comprehension of statements and sentences with varying levels of morphosyntactic complexity in the Spanish language. It is standardized for the Spanish population between the ages of 4 and 12. This test consists of 80 multiple-choice items (four answer alternatives) distributed across 20 blocks of four items each, representing the most representative grammatical structures in the Spanish language. The internal consistency of the test has been studied using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and a reliability index of 0.9096 has been obtained. The reliability obtained for each age group was as follows: 4 years: 0.825; 5 years: 0.779; 6 years: 0.866; 7 years: 0.797; 8 years: 0.828; 9 years: 0.807; 10 years: 0.794; and 11 years: 0.842.

CELF-5. Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals − 5

The Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals − 5 (CELF-5; Wiig et al., 2013) is an individual clinical assessment instrument designed to identify, diagnose, and monitor language and communication disorders in children and adolescents aged 5 to 15 years. This individual application instrument aims to evaluate the user’s strengths and weaknesses in different aspects and dimensions of language in Spanish. This instrument consists of 14 subscales, but only two were used in this research: Sentence comprehension and Execution of instructions. These two scales are scored with 0–1 points, with 0 indicating the absence of the skill and 1 indicating its presence, except for the linguistic profile questionnaire, which consists of a structured response on a Likert-type scale of 0–4, where a score of 0 is associated with “never” and 4 with “always.” The internal consistency of the CELF-5 obtained by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.901. According to the study by Denman et al. (2017), the reliability of the test is between 72.4 and 66.7, which makes it an instrument with good psychometric quality evidence and its use is recommended.

Procedure

For the completion of this study, first, approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia (UCAM), with the code: CE052206. Next, the participant groups were configured, following the inclusion and exclusion criteria previously established for this study, and they were grouped into three experimental groups. In this way, an evaluation of the participants included two 60-minute sessions. The data from the measurement instruments were stored in protected databases, which were later analyzed by the research group members, checking the fulfillment of the research hypotheses.

Design and Data Analysis

The statistical analysis of this non-experimental cross-sectional study was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 23.0 for Windows, developed by IBM, for statistical analysis in this study. Two different statistical designs were used to carry out the analyses. First, the Kolmogorov-Smirnoff test was used to examine the normality of the distribution of the variables that make up the study, which was found to meet the normality assumption. Next, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to observe the relationship between the variables related to the comprehension of different types of grammatical structures in Spanish. This allowed for exploring the differences among the groups that make up the sample. Subsequently, analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests was performed to observe individual differences in each of the variables in the three groups. Finally, to control for Type I error, the Holm-Bonferroni correction (Holm, 1979) was applied to the statistical analyses conducted. Subsequently, post hoc analyses for multiple comparisons between the three groups (ASD, Epilepsy, and ASD and epilepsy) were performed using Bonferroni’s method (Bonferroni, 1936).

Results

A total of 170 participants aged between 7 and 9 years were selected and divided into three groups: the ASD group (n = 57), the ASD and epilepsy group (n = 53), and the epilepsy-only group (n = 60). The ASD group (ASD) consisted of 36 boys and 21 girls (Mage = 8.1; SD = 0.9) diagnosed with grade 1 ASD. The Epilepsy group (EP) comprised 41 boys and 19 girls (Mage = 8.6; SD = 0.4). The ASD and epilepsy group (ASDEP) consisted of 27 boys and 26 girls (Mage = 7.8; SD = 0.8) who also had a diagnosis of grade 1 ASD and were evaluated and diagnosed at their medical reference center. All participants were native Spanish speakers. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the participants who comprised the study’s sample group:

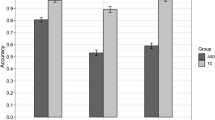

With respect to the results of the analyses, first, the Kolmogorov-Smirnoff test was performed, and its significance level was found to be greater than 0.05, indicating that there is insufficient empirical evidence to reject the null hypothesis, which suggests that the distribution of the participants’ scores follows a normal distribution. In addition, a descriptive analysis was performed to determine the mean scores (M) and standard deviation (SD) for each of the variables included in the study. Finally, the MANOVA conducted to assess differences in measures of grammatical structure comprehension among the ASD, Epilepsy, and ASD with Epilepsy groups revealed the presence of statistically significant differences (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.013, F(2,167) = 81.031, p < 0.001, η^2P = 0.888). As can be seen in Table 2, the variables in which significant differences were obtained included Inferences, Active Structure, Passive Structure, Declaratives, Reflexives, Datives, Interrogative, Exclamatory, Dubitative, Desiderative, Exhortative, Personal, Impersonal, Phrase Comprehension, and Instruction Execution (p < 0.05). The results of the ANOVAs related to the performance in the comprehension of grammatical structures are presented in Table 2.

As can be observed in Table 2, Bonferroni post-hoc tests showed statistically significant differences between the ASD, Epilepsy, and ASD with Epilepsy groups in all variables included in the measures of grammatical structure comprehension (p < 0.001). Thus, the scores obtained by the Epilepsy group were higher than those of the ASD group, and these were higher compared to the ASD with Epilepsy group.

To provide a visual perspective of the mean scores obtained by the three groups in the study, a graph (Fig. 1) was created, which displays a descriptive comparison of the means obtained in each of the variables related to the comprehension of grammatical structures.

As can be observed in Table 2, the variables included in the measurements of grammatical structure comprehension show a statistically significant association and a directly proportional trend (p < 0.001). These results have been established with a 99% confidence interval (p = 0.001).

Discussion

As previously described, the main objective of this study was to explore the differences in the performance of grammatical structure comprehension among three groups of participants diagnosed with ASD, epilepsy, and ASD with epilepsy. The research hypothesis posited that the group of participants diagnosed with epilepsy alone would perform better than the group of participants with ASD, followed by those with the comorbidity of ASD and epilepsy.

The results obtained in our study indicate that participants with epilepsy demonstrate better performance than the other two groups of participants, confirming what was initially proposed in the research hypothesis for this study. Significant differences in grammatical structure comprehension skills exist between the groups. These data cannot be confirmed by other research because there are no studies that compare performance in grammatical structure comprehension in these three disorders. However, these results can be corroborated with other studies conducted with these groups independently (Asberg, 2010; Baixauli et al., 2020; Eigsti et al., 2007; Eberhardt & Nadig, 2018; Henry & Solari, 2020; Saban-Bezalel & Mashal, 2015), which confirm their contribution to the communicative problems presented by individuals with these three disorders, with varying performance in these skills depending on the specific type of diagnosis.

Regarding the pediatric population with epilepsy, there is no consensus on the specific grammar-related skills that may be affected. Some tasks that have been reported as impaired in some studies (Durrleman et al., 2015; Su et al., 2018) appear preserved in others (Bangert et al., 2019; Maltman et al., 2023). However, there seems to be a higher prevalence of poorer performance in tasks involving syntactic skills, such as completing and producing sentences, understanding ambiguous sentences, sentence-picture matching, and comprehending complex syntactic structures (Bulteau et al., 2015; Skotko et al., 2008). Although previous studies have extensively analyzed comprehension skills related to morphosyntax in these children, there is no significant data that allows for the establishment of a specific linguistic profile (Cohen & Le Normand, 1998; Ménard et al., 2000). In terms of verbal comprehension, they exhibit difficulties in understanding verbal messages, often requiring message repetition, providing correct answers/information, and reformulating messages for optimal retention and comprehension (Teixeira & Santos, 2018). In our study, we observed poor performance in variables related to grammatical structure comprehension, especially those involving or related to executive functioning skills, such as understanding inferences, reflexive statements, and executing instructions. One possible explanation for these difficulties may be attributed to the damage present in this population in areas such as the frontal lobe and the networks connecting this lobe to the temporal lobe, which is the primary area responsible for oral language comprehension (Ballester-Plané et al., 2018). People with epilepsy have slowed processing speed, which also hampers effective comprehension of grammatical statements (Caplan et al., 2009). However, even though this population experiences difficulties in these skills, their performance will be superior to what is observed in other neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD (Debiais et al., 2007).

In the case of participants diagnosed with ASD, current scientific literature indicates that these clinical profiles are associated with impairments in both language expression and comprehension. For example, Eigsti & Bennetto (2007) observed grammatical disorders in the majority of children with ASD, aged 9–17 years, in grammatical judgment tasks. In our study, the structures that are most challenging for children with ASD are those that do not follow the common structural order, subject-verb-predicate (SVP), such as coordinated sentences or relative clauses, in which all these children failed. Conversely, the easiest structures are those of SVP, with a 60% success rate, followed by attributive structures, with a 30% success rate (Barsotti et al., 2020). Swensen et al. (2007) also state that children with ASD understand sentences in this SVP order before producing continuous speech. These results demonstrate the difficulties that children with ASD face, limiting their understanding of verbal messages from the main agents in their environment, hindering functional communication, and engaging in more complex conversations beyond their personal interests or motivations. Therefore, difficulties in verbal comprehension have a negative impact on the communicative skills and quality of life of individuals with ASD, severely affecting their inclusion in developmental contexts (Tovar et al., 2015).

Finally, the pediatric population with both ASD and epilepsy displays severe impairments in receptive language skills, including the comprehension of grammatical structures in oral language (Cano-Villagrasa et al., 2023). To date, no research on grammatical structures in Spanish-speaking children with both ASD and epilepsy is available. Therefore, the results indicate that language comprehension, especially grammatical structures, is one of the areas of weakness in both ASD and epilepsy that may contribute to explaining the observed communication deficits. However, there is very little evidence regarding grammatical impairments, and this remains an open area for research (Kanner & Bicchi, 2022). In the present study, the group of participants with both ASD and epilepsy displayed the lowest performance in grammatical structure comprehension tasks among the three groups in this investigation. One of the most plausible explanations for these results is that the presence of epilepsy, in addition to the diagnosis of ASD, leads to increased difficulties in language skills, especially those related to receptive language (Stefanski et al., 2021). With impaired executive functioning, as well as in linguistic dimensions such as lexicon, morphology, and pragmatics, it is logical to assume that verbal comprehension of grammatical structures is also compromised, primarily due to difficulties in following conversations and instructions. This negatively impacts their language skills, resulting in poorer performance in such tasks compared to other profiles, such as those in the epilepsy group and the ASD group (Montouris et al., 2020). Therefore, although studies like Saban-Bezalel and Mashal (2015) suggest that the relationship between auditory comprehension and the severity of linguistic symptoms in ASD is not clear, the present study confirms that linguistic comprehension is a predictor of language difficulties in ASD.

The study has certain limitations that should be taken into account. Firstly, the small sample size raises questions about the generalizability of the results to a larger population. Additionally, variability in the ages of the participant groups could introduce elements of uncertainty in the results, as language abilities tend to evolve with age. Heterogeneity in individual conditions within each group could also influence the observed results. It is noteworthy that external factors, such as linguistic environment and prior education, were not taken into account, which could have had an impact on the participants’ performance. Finally, the specific methodology used in the tests may limit comparability with other similar studies. Despite the mentioned limitations, the study has several strengths worth considering. The formulation of a clear and precise hypothesis provided a specific direction for the research. The results obtained represent a significant contribution to the scientific corpus, shedding light on differences in grammatical comprehension in neurological contexts. Detailed analyses of the particular difficulties of each group enrich our understanding of the linguistic challenges they face. The multidisciplinary perspective of the study, considering both neurological conditions and language skills, offers valuable implications for clinical and educational practice, suggesting ways to address these difficulties from multiple areas.

In conclusion, this study highlights the diversity in grammatical structure comprehension among different participant groups: those with epilepsy, ASD, and ASD with epilepsy. The results support the notion of better performance in the epilepsy group, followed by the ASD group, while the group with both conditions exhibited the lowest performance. These discrepancies have significant implications for communication and the quality of life of those affected. Furthermore, they emphasize the need for future research to delve into the comprehension of grammatical impairments in these disorders and their relationship with other cognitive and linguistic aspects. Ultimately, these findings support the importance of developing personalized therapeutic approaches and educational programs to address the specific needs of these groups of children.

References

Ali, A. (2018). Global Health: Epilepsy. Seminars in Neurology, 38(2), 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1646947.

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Cautionary statement for forensic use of DSM-5. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

Asberg, J. (2010). Patterns of language and discourse comprehension skills in school-aged children with autism spectrum disorders. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 51(6), 534–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2010.00822.x.

Asberg, J., Kopp, S., Berg-Kelly, K., & Gillberg, C. (2010). Reading comprehension, word decoding and spelling in girls with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (AD/HD): Performance and predictors. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 45(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.3109/13682820902745438.

Baixauli, I., Roselló, B., Berenguer, C., & Miranda, A. (2020). Perfiles en comprensión lectora y en composición escrita de niños con autismo de alto funcionamiento [Profiles of reading comprehension and written composition of children with high functioning autism]. Medicina, 80(Suppl 2), 37–40.

Ballester-Plané, J., Laporta-Hoyos, O., Macaya, A., Póo, P., Meléndez-Plumed, M., Toro-Tamargo, E., Gimeno, F., Narberhaus, A., Segarra, D., & Pueyo, R. (2018). Cognitive functioning in dyskinetic cerebral palsy: Its relation to motor function, communication and epilepsy. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology: EJPN: Official Journal of the European Paediatric Neurology Society, 22(1), 102–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2017.10.006.

Bangert, K. J., Halverson, D. M., & Finestack, L. H. (2019). Evaluation of an explicit instructional approach to teach grammatical forms to children with low-symptom severity autism spectrum disorder. American Journal of speech-language Pathology, 28(2), 650–663. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_AJSLP-18-0016.

Barsotti, J., Mangani, G., Nencioli, R., Pfanner, L., Tancredi, R., Cosenza, A., Sesso, G., Narzisi, A., Muratori, F., Cipriani, P., & Chilosi, A. M. (2020). Grammatical comprehension in Italian children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Sciences, 10(8), 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10080510.

Bonferroni, C. (1936). Teoria Statistica delle classi e calcolo delle probabilita. Pubblicazioni Del R Istituto Superiore Di Scienze Economiche E Commericiali Di Firenze, 8, 3–62.

Boucher, J. (2012). Research review: Structural language in autistic spectrum disorder - characteristics and causes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 53(3), 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02508.x.

Braconnier, M. L., & Siper, P. M. (2021). Neuropsychological Assessment in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 23(10), 63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-021-01277-1.

Bulteau, C., Grosmaitre, C., Save-Pédebos, J., Leunen, D., Delalande, O., Dorfmüller, G., Dulac, O., & Jambaqué, I. (2015). Language recovery after left hemispherotomy for Rasmussen encephalitis. Epilepsy & Behavior: E&B, 53, 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.07.044.

Cano-Villagrasa, A., Moya-Faz, F. J., & López-Zamora, M. (2023). Relationship of epilepsy on the linguistic-cognitive profile of children with ASD: A systematic review of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1101535. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1101535.

Caplan, R., Siddarth, P., Vona, P., Stahl, L., Bailey, C., Gurbani, S., Sankar, R., & Shields, D., W (2009). Language in pediatric epilepsy. Epilepsia, 50(11), 2397–2407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02199.x.

Cohen, H., & Le Normand, M. T. (1998). Language development in children with simple-partial left-hemisphere epilepsy. Brain and Language, 64(3), 409–422. https://doi.org/10.1006/brln.1998.1981.

Davidson, M. M., & Ellis Weismer, S. (2017). A discrepancy in comprehension and production in early Language Development in ASD: Is it clinically relevant? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(7), 2163–2175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3135-z.

Davidson, M. M., Kaushanskaya, M., & Ellis Weismer, S. (2018). Reading comprehension in children with and without ASD: The role of Word Reading, oral Language, and Working Memory. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(10), 3524–3541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3617-7.

Debiais, S., Tuller, L., Barthez, M. A., Monjauze, C., Khomsi, A., Praline, J., & Hommet, C. (2007). Epilepsy and language development: The continuous spike-waves during slow sleep syndrome. Epilepsia, 48(6), 1104–1110.

Denman, D., Speyer, R., Munro, N., Pearce, W. M., Chen, Y. W., & Cordier, R. (2017). Psychometric properties of language assessments for children aged 4–12 years: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1515.

Duffy, F. H., Eksioglu, Y. Z., Rotenberg, A., Madsen, J. R., Shankardass, A., & Als, H. (2013). The frequency modulated auditory evoked response (FMAER), a technical advance for study of childhood language disorders: Cortical source localization and selected case studies. BMC Neurology, 13, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-13-12.

Durrleman, S., Hippolyte, L., Zufferey, S., Iglesias, K., & Hadjikhani, N. (2015). Complex syntax in autism spectrum disorders: A study of relative clauses. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 50(2), 260–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12130.

Eberhardt, M., & Nadig, A. (2018). Reduced sensitivity to context in language comprehension: A characteristic of Autism Spectrum disorders or of poor structural language ability? Research in Developmental Disabilities, 72, 284–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2016.01.017.

Eigsti, I. M., Bennetto, L., & Dadlani, M. B. (2007). Beyond pragmatics: Morphosyntactic development in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(6), 1007–1023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0239-2.

Eigsti, I. M., Stevens, M. C., Schultz, R. T., Barton, M., Kelley, E., Naigles, L., Orinstein, A., Troyb, E., & Fein, D. A. (2015). Language comprehension and brain function in individuals with an optimal outcome from autism. NeuroImage Clinical, 10, 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2015.11.014.

Garrido, D., Carballo, G., Franco, V., & García-Retamero, R. (2015). Dificultades De comprensión del lenguaje en niños no verbales con trastornos del espectro autista y sus implicaciones en la calidad de vida familiar [Language comprehension disorders in non-verbal children with autism spectrum disorders and their implications in the family quality of life]. Revista De Neurologia, 60(5), 207–214.

Ge, H., Liu, F., Yuen, H. K., Chen, A., & Yip, V. (2023). Comprehension of Prosodically and syntactically marked focus in cantonese-speaking children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53(3), 1255–1268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05770-1.

Gonzalez-Barrero, A. M., & Nadig, A. (2019). Brief report: Vocabulary and grammatical skills of Bilingual Children with Autism Spectrum disorders at School Age. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(9), 3888–3897. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04073-2.

Henry, A. R., & Solari, E. J. (2020). Targeting oral Language and listening Comprehension Development for students with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A School-based pilot study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(10), 3763–3776. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04434-2.

Hirota, T., & King, B. H. (2023). Autism spectrum disorder: A review. Journal of the American Medical Association, 329(2), 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.23661.

Holm, S. (1979). A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 6, 65–70.

Kalandadze, T., Braeken, J., Brynskov, C., & Næss, K. B. (2022). Metaphor comprehension in individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Core Language skills Matter. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(1), 316–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-04922-z.

Kanner, A. M., & Bicchi, M. M. (2022). Antiseizure medications for adults with Epilepsy: A review. Journal of the American Medical Association, 327(13), 1269–1281. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.3880.

Kelley, E., Paul, J. J., Fein, D., & Naigles, L. R. (2006). Residual language deficits in optimal outcome children with a history of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(6), 807–828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0111-4.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., Risi, S., Gotham, K., Bishop, S. L., & Guthrie, W. (2008). ADOS. Escala De observación para El diagnóstico Del autismo. TEA ediciones.

Loukusa, S., Mäkinen, L., Kuusikko-Gauffin, S., Ebeling, H., & Moilanen, I. (2014). Theory of mind and emotion recognition skills in children with specific language impairment, autism spectrum disorder and typical development: Group differences and connection to knowledge of grammatical morphology, word-finding abilities and verbal working memory. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 49(4), 498–507. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12091.

Maltman, N., Hilvert, E., Friedman, L., & Sterling, A. (2023). Comparison of linguistic error production in Conversational Language among boys with Fragile X syndrome + autism spectrum disorder and autistic boys. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 66(1), 296–313. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_JSLHR-22-00078.

Ménard, A., Le Normand, M. T., Rigoard, M. T., & Cohen, H. (2000). Language development in a child with left hemispherectomy. Brain and Cognition, 43(1–3), 332–340.

Mendoza, E., Carballo, G., Muñoz, J., & Fresneda, M. (2005). CEG. Test De comprensión de estructuras gramaticales. TEA ediciones.

Montouris, G., Aboumatar, S., Burdette, D., Kothare, S., Kuzniecky, R., Rosenfeld, W., & Chung, S. (2020). Expert opinion: Proposed diagnostic and treatment algorithms for Lennox-Gastaut syndrome in adult patients. Epilepsy & behavior: E&B, 110, 107146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107146.

Mukherjee, S. B. (2017). Autism Spectrum disorders - diagnosis and management. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 84(4), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-016-2272-2.

Naigles, L. R. (2013). Input and language development in children with autism. Seminars in Speech and Language, 34(4), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1353446.

Naigles, L. R., & Tovar, A. T. (2012). Portable intermodal preferential looking (IPL): Investigating language comprehension in typically developing toddlers and young children with autism. Journal of Visualized Experiments: JoVE, (70), e4331. https://doi.org/10.3791/4331.

Ricketts, J. (2011). Research review: Reading comprehension in developmental disorders of language and communication. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 52(11), 1111–1123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02438.x.

Roberts, T. P., Schmidt, G. L., Egeth, M., Blaskey, L., Rey, M. M., Edgar, J. C., & Levy, S. E. (2008). Electrophysiological signatures: Magnetoencephalographic studies of the neural correlates of language impairment in autism spectrum disorders. International Journal of Psychophysiology: Official Journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology, 68(2), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.01.012.

Roberts, T. P., Khan, S. Y., Rey, M., Monroe, J. F., Cannon, K., Blaskey, L., Woldoff, S., Qasmieh, S., Gandal, M., Schmidt, G. L., Zarnow, D. M., Levy, S. E., & Edgar, J. C. (2010). MEG detection of delayed auditory evoked responses in autism spectrum disorders: Towards an imaging biomarker for autism. Autism Research: Official Journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 3(1), 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.111.

Robins, D. L., Casagrande, K., Barton, M., Chen, C. M. A., Dumont-Mathieu, T., & Fein, D. (2014). Validation of the modified checklist for autism in toddlers, revised with follow-up (M-CHAT-R/F). Pediatrics, 133(1), 37–45.

Roemer, E. J., West, K. L., Northrup, J. B., & Iverson, J. M. (2019). Word comprehension mediates the link between gesture and word production: Examining language development in infant siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Science, 22(3), e12767. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12767.

Rutter, M., Le Couteur, A., & Lord, C. (2006). ADI-R: Entrevista para El diagnóstico Del autismo-revisada. TEA.

Saban-Bezalel, R., & Mashal, N. (2015). The effects of intervention on the comprehension of irony and on hemispheric processing of irony in adults with ASD. Neuropsychologia, 77, 233–241.

Saban-Bezalel, R., & Mashal, N. (2019). Different factors predict idiom comprehension in children and adolescents with ASD and typical development. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 4740–4750.

Shulman, C., & Guberman, A. (2007). Acquisition of verb meaning through syntactic cues: A comparison of children with autism, children with specific language impairment (SLI) and children with typical language development (TLD). Journal of Child Language, 34(2), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305000906007963.

Skotko, B. G., Rubin, D. C., & Tupler, L. A. (2008). H.M.‘s personal crossword puzzles: Understanding memory and language. Memory (Hove England), 16(2), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210701864580.

Stefanski, A., Calle-López, Y., Leu, C., Pérez-Palma, E., Pestana-Knight, E., & Lal, D. (2021). Clinical sequencing yield in epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, and intellectual disability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsia, 62(1), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.16755.

Su, Y. E., Naigles, L. R., & Su, L. Y. (2018). Uneven expressive Language Development in Mandarin-Exposed Preschool Children with ASD: Comparing Vocabulary, Grammar, and the Decontextualized Use of Language via the PCDI-Toddler Form. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(10), 3432–3448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3614-x.

Svindt, V., & Surányi, B. (2021). The comprehension of grammaticalized implicit meanings in SPCD and ASD children: A comparative study. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 56(6), 1147–1164. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12657.

Swensen, L. D., Kelley, E., Fein, D., & Naigles, L. R. (2007). Processes of language acquisition in children with autism: Evidence from preferential looking. Child Development, 78(2), 542–557. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01022.x.

Tager-Flusberg, H., Rogers, S., Cooper, J., Landa, R., Lord, C., Paul, R., Rice, M., Stoel-Gammon, C., Wetherby, A., & Yoder, P. (2009). Defining spoken language benchmarks and selecting measures of expressive language development for young children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 52(3), 643–652. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0136).

Teixeira, J., & Santos, M. E. (2018). Language skills in children with benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: A systematic review. Epilepsy & Behavior: E&B, 84, 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.04.002.

Torrens, V., & Ruiz, C. (2021). Language and Communication in Preschool Children with Autism and other Developmental disorders. Children (Basel Switzerland), 8(3), 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8030192.

Tovar, A. T., Fein, D., & Naigles, L. R. (2015). Grammatical aspect is a strength in the language comprehension of young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 58(2), 301–310. https://doi.org/10.1044/2014_JSLHR-L-13-0257.

Tran, S., Mathon, B., Morcos-Sauvain, E., Lerond, J., Navarro, V., & Bielle, F. (2020). Neuropathologie de l’épilepsie [Neuropathology of epilepsy]. Annales De Pathologie, 40(6), 447–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annpat.2020.08.001.

Tuchman, R., Alessandri, M., & Cuccaro, M. (2010). Autism spectrum disorders and epilepsy: Moving towards a comprehensive approach to treatment. Brain & Development, 32(9), 719–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.braindev.2010.05.007.

Venker, C. E., Kover, S. T., & Ellis Weismer, S. (2016). Brief report: Fast mapping predicts differences in concurrent and later Language abilities among children with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(3), 1118–1123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2644-x.

Wechsler, D. (2015). WISC-V. Escala de inteligencia de Wechsler para niños-V Pearson (Edición original, 2014).

Wiig, E. H., Semel, E., & Secord, W. A. (2013). Clinical evaluation of Language fundamentals–Fifth Edition (CELF-5). NCS Pearson.

Wiklund, M., & Laakso, M. (2021). Comparison of Disfluent and Ungrammatical Speech of preadolescents with and without ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(8), 2773–2789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04747-2.

Funding

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad Málaga/CBUA

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest that could influence the.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Villagrasa, A.C., Gozalbo, N.P., González, B.V. et al. The Comprehension of Grammatical Structures in a Pediatric Population with ASD and Epilepsy: A Comparative Study. J Autism Dev Disord (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-024-06291-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-024-06291-9