Abstract

The purpose of this paper was to determine whether recommendations made by King & Murphy (Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 44:2717–2733, 2014) in their review of the evidence on autistic people in contact with the criminal justice system (CJS) have been addressed. Research published since 2013 was systematically examined and synthesised. The quality of 47 papers was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. Findings suggest a limited amount of good quality research has been conducted that has focused on improving our understanding of autistic people in contact with the CJS since 2013. Methodological limitations make direct comparisons between autistic and non-autistic offenders difficult. Autistic people commit a range of crimes and appear to have unique characteristics that warrant further exploration (i.e., vulnerabilities, motivations for offending).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Autism and the Criminal Justice System

The prevalence of autism has been much debated over the years, but it was estimated at approximately 1 in a 100 in England by Brugha et al. (2011). However, a recent review has suggested that the prevalence varies across the world (Chiarotti & Venerosi, 2020), with a recent study in Poland, which suggested that 5.29/1000 of children aged 0–16 years were autistic (Skonieczna-Zydecka et al., 2017) and in Spain a prevalence of 11.8/1000 autistic children aged 6–10 years was reported (Pérez-Crespo et al., 2019). It is now accepted that autistic individuals have varying degrees of strengths and challenges in relation to social communication, social interaction, and social imagination (Wing & Gould, 1979), the spectrum being considered a continuum. Following screening and a developmental interview (such as the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised; Rutter et al., 2003), as well as an observation of the person themselves engaging in specified tasks (using a measure such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Lord et al., 2000), a diagnosis of Autism can be made by a qualified clinician using the criteria from the International Classification of Diseases-10 or 11 (World Health Organization, 1992, 2019), and the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Previous research has suggested autistic adults are over-represented in some parts of the Criminal Justice System (CJS), with some evidence indicating autistic individuals are more likely to have contact with the police than the general population (Lindblad & Lainpelto, 2011; Siponmaa et al., 2001). However, estimates of the prevalence of autism within the CJS have varied considerably over the years, no doubt partly due to different methodological approaches within the research. Arguably, according to some studies, autistic people are no more or less likely to come into contact with the CJS compared to non-autistic people (Brookman-Frazee et al., 2009; Cheely et al., 2012; Hippler et al., 2010; Mourisden et al., 2008; Woodbury-Smith et al., 2006). Where criminal offending does occur, research has suggested autistic people engage in a variety of offence types, including violence (e.g., Barry-Walsh & Mullen 2004; Cheely et al., 2012), arson (Woodbury-Smith et al., 2010), sexual offending (e.g., Mouridsen et al., 2008; Långström et al., 2008; Søndenaa et al., 2014), and stalking (e.g., Stokes & Newton, 2004; Stokes et al., 2007).

King & Murphy (2014) sought to explore these issues further by conducting a systematic review of the evidence pertaining to autistic people within the CJS, which focused on summarising research conducted up to January 2013. The authors explored research on the prevalence of autism amongst people in contact with the CJS (at various stages in it), the occurrence and types of offending, and the presence of co-occurring psychiatric conditions. Findings suggested autistic people were less likely to offend than other people of the same age and gender. However, the evidence on types of crime was inconsistent, perhaps due to the poor quality of research methodology, though it seemed that ‘offences against the person’ were more common than property related offences (King & Murphy, 2014). There did also appear to be a trend of higher rates of psychosis and personality disorder diagnoses, rather than other mental health diagnoses, among autistic people in the CJS, although the samples in the studies were biased towards service-users recruited from mental health settings. The factors identified in the literature which might predispose autistic people to offend included social naiveté, misunderstanding of social situations, lack of understanding of the rules, and obsessional interests (King & Murphy, 2014).

King & Murphy (2014) highlighted the limitations of the evidence base and consequently made several recommendations including the need for consistency in the methods used to diagnose autism, and the need for further research into the experiences of autistic people who encounter the CJS. Additionally, King and Murphy argued that few researchers used representative samples, and even when they were representative, the participants came from within specific geographical locations. Only a small number of studies used comparison groups and there were differences in how offending behaviour was defined. In addition, King & Murphy (2014) identified that the lack of research on autistic female offenders was problematic and concluded that the study of the relationship between autism and offending was in its infancy.

Recent Developments in Policy

Since the publication of King and Murphy’s (2014) review, recognition of autism has increased with new law, policy and guidance having been introduced in England and Wales, including the Care Act (2014), ‘Transforming Care for people with learning disabilities—next steps’ (NHS England, 2015b), ‘Building the Right Support’ (NHS England, 2015a) and ‘Autism Spectrum Disorder in Adults’ (NICE, 2016). Further research on supporting autistic prisoners aimed to develop a set of Autism Accreditation standards within prisons (Turner et al., 2016). And the Liaison and Diversion Services (NHS England & NHS Improvement, 2019) has been gradually introduced to support vulnerable individuals who encounter the CJS (following recommendations in the Bradley report, 2009). In addition, the Police and Criminal Evidence Act Code of Practice was revised in 2019 to provide further guidance to officers when detaining, cautioning, and interviewing vulnerable suspects, including autistic people (Home Office, 2018). However, ‘Beyond the High Fence’ (NHS England, 2019) suggested the understanding around autism remained poor in forensic services, underpinned by insufficiently experienced staff, who were unable to adequately support autistic people. Reports of high levels of physical and medical restraint of autistic people were confirmed in a review of restraint, seclusion and segregation conducted by the Care Quality Commission (2020) which found that the majority (64%) of the 66 cases they investigated had autism.

Similar policy developments have been seen beyond the UK with the introduction of the Autism CARES Act (2019) in the USA and the National Call to Action to improve services issued by the Australian Advisory Board on Autism Spectrum Disorder in 2011. However, in other countries across the world there may well be even more of a need for an improved understanding of autism, with few policies and guidelines in existence.

Whilst new legislation, policies, and guidance have been introduced since King and Murphy’s (2014) review, particularly within the UK, the question remains as to whether our research knowledge and understanding of autistic individuals who encounter the CJS has progressed, whether sufficient changes have been implemented and evaluated to improve practice, and whether the experiences of autistic adults who encounter the CJS has improved.

Aims

The current review therefore aims to provide an update of King and Murphy’s (2014) paper to firstly identify whether the gaps in the research and their recommendations have been addressed, as well as to identify whether our knowledge and understanding of autistic people who encounter the CJS has improved. In reviewing literature published since the original review, authors aimed to determine a more accurate estimate of prevalence of autism in the CJS, and outline the characteristics associated with autism and offending behaviour.

Method

Design

A mixed methods systematic review of the research on autistic adults with a history of criminal offending was conducted. To provide continuity and for comparisons to be made between King & Murphy (2014) and the current update, previous search methods were duplicated.

Database and ancestry searches resulted in 47 articles that met the specific inclusion criteria. Data was extracted and a quality assessment was conducted using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (Hong et al., 2018, 2019). There are five criteria for appraising studies and ratings vary from 0* (none of the criteria are met) to 5* (all criteria are met). A data extraction template was used to record relevant information under the following heading: Title, author, year of publication, study population, number of participants, methods, data on prevalence of autism/offending, types of offending behaviour, psychiatric diagnosis, and other information. The quantitative and qualitative findings were then summarised based on the previous review conducted by King & Murphy (2014), under the following headings:

-

Prevalence of autism in offender populations.

-

Prevalence of offending behaviour in autistic people.

-

Types of offence committed by autistic people.

-

Co-morbid psychiatric diagnoses.

-

Other results.

Search Strategy

A systematic search of the literature was conducted on 10th December 2018 by the second author and updated on 1st April 2021 by the first author of the same electronic databases (PsychINFO, Medline, Criminal Justice Abstracts, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews) as searched by King & Murphy (2014), except for the National Autistic Society database due to its closure post 2014. In addition, a further two databases were added to broaden the search (PsychARTICLES, CINAHL Plus with Full Text) using identical search terms to find articles relating to autism and offending. Date limiters were applied to include papers from 1st January 2013 to 1st April 2021. To ensure continuity, the same search terms were used to find articles and these are provided in Table 1.

Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria applied in this review matched the King & Murphy (2014) systematic review and aimed to consolidate and evaluate current research on autism and offending. Articles were reviewed to ensure that they met the following inclusion criteria:

-

Written in English.

-

Published in peer reviewed journals.

-

Included participants with an autism diagnosis according to ICD-10/ICD-11 or DSM-IV-TR/DSM-5.

-

Participants with involvement in the CJS (those who were suspects, offenders and in contact with the CJS including contact with police, courts, probation, and prison services in addition to forensic services such as secure hospitals).

Articles were excluded for the following reasons:

-

Individuals with only apparent ‘autistic symptoms’ and no attempt to diagnose.

-

Studies that included witnesses or victims of crime, rather than suspects or offenders.

-

Single case studies, dissertations, and review papers.

-

Articles which focused on treatment.

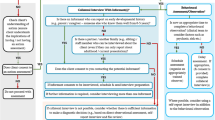

Identification of Studies

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA; Knobloch et al., 2011) was used to identify relevant studies (Fig. 1). The initial search yielded 6453 papers. After duplicates were removed, the titles and abstracts of 5512 papers were screened by the first author and 5416 papers were excluded based on the above inclusion and exclusion criteria. Therefore, the full texts of 96 papers were identified by the first author for review. Following a further review of the 96 articles against the eligibility criteria, 47 articles were included.

Data Extraction

The 47 studies were recorded, and relevant data such as author, year of publication, sample, methods, data on prevalence, types of offending behaviour, psychiatric diagnosis was extracted (see Table 2). A total of 36 publications were either cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, case control studies or descriptive studies. A total of six studies used qualitative designs and included interviews and case studies. Lastly, five studies used a mixed methods design, which included surveys and interviews.

Regarding overlapping samples, study 2 used the same sample of 269 violent offenders as both study 9 and 20. Study 7 used the same population sample of 3382 offenders as Study 15. Furthermore, study 34 used a sub-sample (n = 8) of participants recruited to study 7. Study 27 and 28 used the same sample of 35 autistic adults in two papers. Lastly, study 44 used a sub-sample of autistic adults (n = 9) and parents/carers (n = 19) as recruited to study 43. Papers with duplicate samples were included within the review as each reported unique findings. However, when calculating the total number of participants across studies, papers which made use of a previously reported sample were not included, to avoid inflating the sample size.

Quality Assessment

Whilst the King and Murphy review did not use a specific quality appraisal tool, best practice guidelines suggest one is used, therefore, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., 2018, 2019) was used for the current review. The MMAT is a 21-item checklist, used to rate the quality of quantitative (including cohort studies, cross sectional studies, longitudinal studies, case control studies and descriptive studies), qualitative, and mixed methods studies selected for review. Each article was appraised and scored using the criteria provided in the MMAT user guide (2018) by the first author and 20.8% were rated by the third author to assess reliability. Differences in ratings were found within five papers due to variation in interpretations for two criteria of the MMAT. Following discussions between the current authors, agreement on interpretation of criteria was reached resulting in complete agreement of ratings (inter-rater reliability: 100%). Studies were appraised based on five areas relating to the appropriateness of methodology, data analysis techniques and data collection techniques, the representativeness of the sample, reliability of outcome data, and the researchers’ interpretation of research findings.

Results

Quality Appraisal

Studies using only quantitative methods accounted for 36 of the 47 papers (1–11, 13–26, 29–30, 32, 35–37, 39, 45–47). Additionally, six qualitative papers were reviewed (12, 34, 38, 40, 41, 42), and five used mixed methods analyses, in which authors collected both qualitative and quantitative data predominantly from surveys (27, 28, 31 43, 44) and interviews (31). Of the 47 papers, 8 were rated as 5* (17%), 25 were rated as 4* (53%), 9 were rated 3* (19%), and 5 were rated as 2* (11%).

The quality of included papers was compromised by several methodological limitations (e.g., poor generalisability, unrepresentative samples, lack of matched comparison samples, reliance on retrospective data collection, lack of standardized instruments), which impacted study outcomes and limited the extent to which findings could be relied upon. Several authors of studies that took a qualitative approach to the research reported data collection methods that were considered inadequate (e.g., 27, 28 & 40), and/or did not support their interpretation of findings with sufficient data (e.g., 34, 40, & 42), which led to an unclear link between qualitative data sources, data collection, analysis, and interpretation (e.g., 40 & 42). In addition, several authors of quantitative studies with non-randomised comparison samples did not recruit a representative sample of participants (e.g., 1, 4, 22, 29, 30–33, 36, 45, 47). Due to an overreliance on retrospective data collection methodologies and database/documentary analyses, missing data was a consistent weakness of the included studies (e.g., 4, 18 19, 24, 32, 46). Moreover, confounding variables were rarely accounted for in the design or analysis of findings (e.g., 1, 2, 4–10, 13–17, 21, 29, 30–32, 37, 46). Only one study did include a matched comparison sample controlling for confounding variables (24). Altogether, authors recruited 606 autistic adults, 1,271 adults with intellectual disabilities and autism and a population control group of 2,973 young adults (24). Those studies that utilised a mixed methods design, did not meet the criteria for both of the different components of the methods involved.

Study Characteristics

Of the 47 studies, 19 were conducted in the UK, 6 in Sweden, 6 in the USA, 4 in the Netherlands, 3 in Norway, 4 in Canada, 2 in Portugal and 3 in Australia. Of the 47 studies, authors of 9 recruited autistic people in contact with the CJS from state/nationally representative populations (14, 16, 22, 24–28 & 35). Authors of 13 studies recruited autistic people in contact with the CJS from psychiatric inpatient services (1, 4–6, 8, 11, 30, 32, 33, 36, 37, 40 & 45), 9 from prison and/or probation services (2, 9, 12, 17, 20, 23, 34, 38 & 41), 5 from the community (29, 31, 43, 44 & 47), 4 from forensic psychiatric examinations (7, 15, 42 & 46), 2 from police services (13 & 21), 2 from a residential treatment facility (18 & 19), 1 from a forensic outpatient service (3), 1 from community and inpatient forensic services (10), and 1 from a combination of prison, probation, and psychiatric inpatient services (39).

Of the 47 studies, authors of 20 recruited males only (2, 3, 9, 11, 12, 17–20, 23, 32, 33, 36–42 & 46), while authors of one study did not report the gender of participants (22), and authors of the remaining 26 studies recruited both males and females (1, 4–8, 10, 13–16, 21, 24–31, 34, 35, 43–45, 47).

Of the 47 studies, authors of 13 reported the age of autistic offenders (n = 326) ranging from 19 to 57.3 years (M = 31.50, SD = 11.03). Of the 47 studies, authors of 23 reported the gender of autistic offenders (n = 450), and most participants were male (n = 433) rather than female (n = 17). Findings are therefore biased towards autistic males.

Of the 47 studies, authors of only three studies reported the ethnicity of autistic offenders (n = 83). Ethnicities reported were White (n = 69), Black (n = 8), Asian (n = 1), and other (n = 5).

Prevalence of Autism in the CJS

If autistic people were as likely as anyone else to be involved in the CJS we would expect the rates of autistic people in CJS populations to be about the same as the prevalence of autism in the general population (i.e., of the order of 1%).

Of the 47 studies included in the review, authors of 24 included prevalence data for autism amongst a sample of suspects or offenders (studies 1–24). A minority of studies reported using gold standard methods for diagnosing autism (2, 9, 11, 20), such as the ADI-R (Lord et al., 1994), Diagnostic Interview for Social & Communication disorders (DISCO; Wing et al., 2002) and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al., 2000; 2012). Several other studies used validated screening methods (17 and 23), including the Autism Spectrum Quotient (ASQ; Baron-Cohen et al., 2001), the Asperger’s Syndrome Diagnostic Scale (Myles et al., 2001). Other studies referred only to the ICD-10 or DSM-IV, perhaps due to a heavy reliance on retrospective case file data (e.g., 1, 4, 6–8).

Unbiased samples were recruited to a minority of studies (5, 7, 9, 12, 14, 15, 22). Most other studies recruited participants already hospitalised in psychiatric inpatient services who were therefore already identified as being a risk to either themselves or the public and as having a mental health condition (e.g., 1, 4, 6, 8 & 11). One study that recruited participants from the community, was also limited to people known to an outpatient psychiatric service (3). Even when unbiased samples were recruited, the methodological quality of these studies was limited as it was unclear how a diagnosis of autism was made and by whom (e.g., 5 & 7), or because samples of participants were limited by gender (e.g., 9 and 23), or type of offending behaviour (e.g., animal abuse or sexual offending; 19, 21).

Consequently, prevalence of autism amongst offending populations varied widely from 0.2% in a sample of offenders detained across seven prisons in New South Wales, Australia (12) to 62.8% in a sample of adolescent male offenders aged between 15 and 20 years who had been ordered by Juvenile Court into an adolescent sexual offenders’ program in the USA (19). Of the 16 studies to include prevalence data of autism derived from biased samples of offenders (n = 2926), 13.3% of offenders were reported to be autistic (n = 388; see Table 2). Of seven studies to include prevalence data of autism derived from mostly unbiased samples of offenders (n = 15,963), 3% of offenders were reported to be autistic (n = 486; see Table 2), though, none of the samples recruited can be said to be truly unbiased due to several factors, including the likelihood of prisons providing lower prevalence of autism due to people being diverted away from custody, as well as difficulties associated with the accuracy of diagnosis. The current prevalence of autism in offender populations is therefore slightly higher than the prevalence of autism in community samples, which range between 0.7 and 1.1% (Baxter et al., 2015; Brugha et al., 2016). Therefore, findings suggested autistic people may be somewhat over-represented in the Criminal Justice System, though biased samples and methodological limitations of the research conducted impact the reliability of these findings, for example, people recruited from the forensic psychiatric inpatient services often produce high prevalence rates as those referred are highly likely to have other mental health needs (King & Murphy, 2014). Moreover, it may be that suspects with limitations to their social behaviour (for example, poor eye contact) may be more likely to be seen as risky and therefore they may be more likely to receive custodial sentences. An added difficulty is that, due to varying samples and inconsistency in diagnosis assessment tools used when recruiting autistic suspects and offenders, it is difficult to make comparisons across studies.

Autistic People and their Contact with the CJS

Offending is known to be generally more common amongst teenage boys, rather than older men and girls (Farrington et al., 2021). If autistic people are as likely to offend as other people without autism, we would expect to see this reflected in figures for comparison samples of autistic and non-autistic people, matched for age and gender.

Of the 47 studies, authors of five reported on the prevalence of autistic people’s involvement in the CJS. Here it is essential for studies to have a comparison group of non-autistic people involved in the CJS for any conclusions to be drawn. None of the included studies reported a robust procedure for diagnosing autism, but instead relied on previous diagnosis, which on occasions was self-reported (e.g., 27 & 28). Study 29 did however, verify a self-reported diagnosis using the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ; Rutter et al., 2003). Studies reporting on the prevalence of involvement in the CJS for populations of autistic people were therefore of limited methodological quality due to a lack of robust assessment of autism.

Consequently, prevalence of involvement in the CJS for populations of autistic people varied widely from 0.7% in a community sample of 284 autistic adolescents and adults in Ontario, Canada (29) to 5% in a nationally representative sample of 920 autistic youth aged 15–17 years in the USA (26). Overall prevalence of involvement in the CJS across the six studies (n = 6978) was 4.3% (n = 300; see Table 2). However, what constitutes involvement in the CJS varied between studies, for example, study 26 reported on those who had been arrested, whereas study 25 reported on those convicted of at least one violent offence. Consequently, how authors define involvement in the CJS will impact on prevalence data, whereby a broader definition including any contact with the criminal justice system will increase prevalence figures as those who are arrested or questioned by the police may not go on to be convicted. A lack of research including unbiased comparison samples limits our understanding of whether those who were autistic were at more or less risk of offending in comparison to non-autistic people. Nevertheless, other studies of non-autistic adolescents (e.g., Farrington et al., 1975; 2021) suggest that these figures for autistic adolescents are much lower than for non-autistic adolescents. As reported by Farrington & Hawkins (1991), by the age of 21 years, 31% of males from working class backgrounds in England (n = 411) had a criminal conviction.

Types of Offences Committed by Autistic People

As can be seen in Table 2, types of offences committed by autistic individuals varied and included arson, property crime, sexual offending, drug offences, traffic incident/driving offences, stalking, fraud, theft, and robbery (e.g., 4, 7, 30, 31, 33, 34). Of the 47 studies included in the review, authors of 10 studies recruited a group of autistic people, as well as a comparison group of non-autistic people (1, 9, 10, 14, 24, 30, 39, 45, 47).

Authors of study 24 compared 45 autistic service-users recruited from two specialised low secure psychiatric services to 43 participants from a non-specialised low secure unit and reported autistic service-users were more likely to be younger, less likely to have a diagnosis of drug or alcohol misuse/dependence or personality disorder. Furthermore, autistic service users, when compared to non-autistic service users were less likely to have a lifetime history of physical violence or sexually inappropriate behaviour towards others or to be non-compliant with prescribed medication. They were also less likely to have a forensic history and their number of previous convictions tended to be lower (24). These findings are supported by study 10, in which findings suggested autistic people referred to forensic intellectual disability services had a lower rate of being charged with a criminal offence.

Limited research has been conducted to explore risk factors for autistic and non-autistic people for different types of offending. Authors of study 14 compared 143 autistic and 572 non-autistic juveniles with intellectual disabilities and other special educational needs involved in the CJS and reported autistic offenders were least likely to commit property offences. However, study 9 reported that at index conviction, autistic offenders were overrepresented in child sexual offending, when compared to non-autistic offenders. Though non-autistic offenders had more previous convictions (e.g., for drug related crimes), no difference in total number of prosecuted crimes was reported, although, the reliability of these findings is limited due to the sample consisting only of young male offenders detained within a prison establishment and convicted of violent offences only. Nevertheless, study 39 compared 40 autistic male offenders and 40 non-autistic offenders to a community sample of 40 autistic and 39 non-autistic people without a history of offending behaviour. Findings suggested autistic offenders scored higher for risk factors related to mental health, conduct problems, and family/childhood adversity (39).

In comparison, authors of study 30 compared autistic adults (n = 606), adults with intellectual disabilities (n = 1271), and population controls (n = 2973) and reported few group differences. Findings suggested that young autistic adults were not overrepresented in the CJS compared to their non-autistic peers and were less likely to be involved in the adult justice system than their peers. These findings are supported by the findings of study 47 in which similar rates across all forms of perpetration for autistic and non-autistic adults were reported.

Few studies compared the offending behaviour of autistic and non-autistic offenders to identify unique characteristics or similarities between these populations. Similarly, few studies compared autistic offenders to autistic people without an offending history to identify unique characteristics or risk factors amongst populations. Despite conflicting evidence regarding the similarities and differences between autistic and non-autistic offenders, authors of study 45 compared autistic males (n = 15) to a matched control group of non-autistic males (n = 15) on their ability to understand and follow court proceedings and stand trial. Findings suggested that autistic adults had more difficulty understanding and following aspects of the trial process and proceedings, despite their prior experience of the courtroom process. These findings suggest autistic adults who encounter the CJS have unique needs.

Co-morbid Psychiatric Diagnosis

Authors of 33 of the 47 studies reported on comorbid psychiatric diagnosis of autistic offenders (see Table 2). Most authors recruited samples who were already in a mental health hospital or secure state facility (4, 11, 17 19, 30, 32, 33, 36 & 37), or who had been referred for forensic psychiatric assessment (7, 10, 15 & 34). Additionally, authors of five studies recruited from prison and probation services (study 2, 9, 21, 23, 38), while authors of one study recruited from the prison, probation, one approved premise and two hospitals (39), and authors of six studies included recruited participants from community samples (study 27, 28, 29, 31, 43, 44). However, in studies 32, 46 and 47, participants comprised autistic individuals who had interacted with the police for a variety of reasons (e.g., victimisation, mental health crisis) and therefore not all participants had a history of offending behaviour. Furthermore, two studies of poor methodological quality failed to report the type of forensic services in which autistic offenders were placed (40 & 42). Common psychiatric diagnoses reported included attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Tourette syndrome, intellectual disabilities, substance related disorders, psychosis, personality disorders, anxiety, mood disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Study 4 reported the prevalence of comorbid diagnosis of substance misuse and personality disorder were significantly lower in the autistic group compared to the non-autistic group. Study 33 reported the age at first contact with psychiatric services for the autistic group was lower compared to the non-autistic group, but age at first psychiatric admission was not significantly different. Further, 73.3% had psychiatric comorbidity, most commonly schizophrenia, but unlike controls, personality disorder and drug and alcohol disorders were uncommon. Additionally, a lifetime history of drug use, but not alcohol use was significantly less common for the autistic group, when compared to the non-autistic group. Study 39 reported that autistic offenders scored higher on the mental health risk factors than both typically developing offenders and typically developing non-offenders. Study 16 reported that serial offenders were more likely to have a personality disorder or autism when compared to single offenders.

Authors of five studies used a population-based cohort leading to findings that are likely to be more representative of offenders with an autism diagnosis (20, 22, 25, 26, 35). These studies showed that co-occurring intellectual disabilities and ADHD were most common, as well as psychotic disorder, drug and alcohol misuse, personality disorder, affective disorders, anxiety, tic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Authors of study 25 compared autistic and non-autistic individuals on the Swedish national crime register and found autistic individuals who also had ADHD and/or conduct disorder had an increased risk of violent criminality. Furthermore, autistic individuals with intellectual disabilities were less likely to be convicted, and autistic individuals without intellectual disability were more likely to be convicted, compared to people without any of these conditions. However, other methodological issues affecting the reliability and validity of findings include retrospective data collection, a lack of robust assessment, and female offenders being underrepresented.

Experiences of the CJS

Several studies recruited participants from the autistic community, asking them about their experiences of the police in England, Wales, and Australia (31, 43, 44). Findings suggested that over 60% of respondents were dissatisfied with their experience with the police (31 & 43). The autistic community reported a lack of police awareness and knowledge of autism, a lack of information and explanation given by the police, and delays throughout the CJS (43). Furthermore, the needs of autistic individuals were often not met, and some individuals felt victimised or discriminated against by police officers (43). Interestingly, some researchers have explored whether autistic people disclose their diagnosis to the police, with findings suggesting as many as 36% never disclosed and 25% only disclosed their diagnosis on some occasions (study 43). Furthermore, their decision to not disclose was linked to a fear of discrimination or victimisation by police officers (study 43). Studies 27 and 28 recruited 35 autistic adults, 80% of whom reported to have interacted with the police at least once in their lifetime (n = 29), including being stopped by police (n = 17), being a victim of a crime (n = 17), for a mental health crisis (n = 11), suspected of a crime (n = 8), placed in handcuffs (n = 8) and convicted (n = 2). As many as 42.3% (n = 11) of respondents reported that the police had used force during the described interaction, including restraint (36.4%, n = 4), handcuffs (36.4%, n = 4), and assault (n = 3). Furthermore, none of the respondents indicated that the officer(s) were able to identify that the person with autism was vulnerable (27 & 28).

Other researchers have explored the experiences of autistic offenders in prison establishments (e.g., 12, 34 & 41). Research has highlighted the challenges surrounding the misunderstanding of autism in relation to social interactions with staff and other prisoners, which on occasions has escalated into altercations. Difficulties coping with feelings of frustration, stress, fear, upset, confusion, anxiety, and agitation that were caused by the unpredictability of the prison environment (i.e., changes in prison routine), and noise was reported as very difficult to cope with, as well as a lack of staff understanding regarding their diagnosis of autism. In contrast, some autistic offenders (n = 6) have reported coping in prison, as it provided structure and opportunities for work and study (34). It is likely that prisons vary in their ability and willingness to support autistic offenders. For example, Her Majesty’s Young Offender Institution Feltham, Her Majesty’s Prison Parc and Her Majesty’s Prison Wakefield have received autism accreditation from the National Autistic Society demonstrating their commitment to providing support to autistic offenders (Hughes, 2019; Lewis et al., 2015).

Risk Factors for Offending

Several studies explored other risk factors associated with autistic offenders, including being male (29), single (7, 33), not having children (33), having birth defects (10), behavioural issues during childhood (14), poor educational attainment (7, 37), lack of regular employment (7, 37), poor social networks (7), having a history of verbal and physical aggression (4, 29, 32), offending/antisocial behaviour (33, 45), sexually inappropriate behaviour (33), substance misuse (31, 38), and a history of victimisation (4, 10, 19, 26, 27, 28, 31 33, 40 & 46). A range of parental and familial characteristics, such as belonging to households with lower incomes, migrant households, parental history of criminal convictions, and maternal psychiatric disorders were associated with violent criminality in autistic individuals (40). Authors of study 7 reported that 29% of the group had been in foster or institutional care as children (n = 14) and 4% had more than three changes of (non-family) carer during childhood (n = 2). Furthermore, a delayed diagnosis of autism has also been identified as a potential risk factor for offending (15, 25, 40). Several studies also reported on the motivations of autistic offenders. Common motivations included revenge, social misunderstanding, idiosyncratic rationalisations or explanations, obsessions/special interests, and social naivete (7, 15, 38).

However, autistic offenders were rarely compared to non-autistic offenders in these analyses, meaning their unique characteristics have not been identified. Nevertheless, authors of study 7 reported on a sample of 48 autistic offenders who had undergone forensic examination between 2000 and 2010 in Norway and found that 56% had no previous convictions (n = 27). Furthermore, authors of study 33 reported that a lifetime history of sexually inappropriate behaviour (n = 13) and physical violence (n = 35) were less common for the autistic offenders, when compared to non-autistic offenders. Similarly, study 9 recruited 269 violent male offenders, including 26 autistic offenders. Findings suggested there were few differences between autistic and non-autistic offenders, including prevalence of psychopathy, although, childhood placements in foster homes were overrepresented in the autistic group. Study 39 recruited arguably a more representative sample of males from an offending and non-offending population with and without autism from England and Wales from four prison establishments, two probation services, one approved premise, two secure hospitals and the community. Autistic offenders reported higher scores on the offending risk factors questionnaire (unpublished) than non-offenders and also offenders without autism. Autistic offenders scored significantly higher than the non-autistic, non-offender group on family and childhood adversity risk factors. Autistic offenders scored higher than both the autistic non-offenders and non-autistic non-offenders on the conduct problems risk factors. However, few other studies have sought to compare findings between populations, and due to biased sampling, the findings of the current review may be an overestimation of aggression and violence in autistic offenders.

Furthermore, autistic people who encounter the CJS also appeared to be vulnerable to social isolation and segregation following arrest, due to difficulties associated with interpersonal skills and communication (11, 12). For example, study 26 reported that among a nationally representative sample of 920 autistic youth, 27.5% had experienced social isolation. In addition, research also suggested as many as 97.6% of autistic offenders having a history of self-harm (n = 41; study 4 & 37). Furthermore, the prevalence of self-harm in the autistic group was significantly higher than the non-autistic group (4). In contrast, study 33 found that a history of self-harm was less prevalent for autistic service-users admitted to a secure psychiatric inpatient service, compared to non-autistic service-users (n = 17), although the difference did not reach statistical significance.

A History of Victimisation

Authors of several studies identified that autistic people who encounter the CJS often have a previous history of victimisation. For example, study 4 recruited 138 service-users from a specialised forensic inpatient intellectual disabilities service and findings suggested 40.5% of autistic service-users reported being a victim of any type of abuse (n = 17), and 33.3% reported being a victim of sexual abuse (n = 14). Similarly, study 10 reported on referrals made to forensic community and secure intellectual disability services in England and Scotland and found 23.4% of autistic people had been abused as a child (n = 11). In contrast, authors of study 33 recruited a control group and compared autistic and non-autistic service users admitted to two secure psychiatric inpatient services and found a lower percentage of the autistic group had a history of childhood neglect or abuse. However, study 19 which recruited 43 male adolescents adjudicated ‘delinquent’ due to a sexual offence in a state residential facility in Pennsylvania, reported emotional abuse and neglect were more common in the autistic group compared to the non-autistic group.

Discussion

Summary of Findings and Interpretation

Findings of the current review suggested a limited amount of good quality research has been conducted that has focused on improving our understanding of autistic people in contact with the CJS since 2013. Findings suggested that as with the general population, autistic people engage in a range of offending behaviours. However, studies of autistic people who encounter the CJS are still in their infancy and our understanding of their unique characteristics and treatment needs remains limited. Much like the studies included in the previous review by King and Murphy, most of the findings from the updated literature have originated from biased samples (i.e., mental health services) and are unlikely to reflect all autistic people who may be in contact with the CJS (e.g., individuals cautioned, arrested, fined, living in the community, those convicted of minor offences, or those in custody awaiting trials). As with the previous research identified by King & Murphy (2014), study methodologies made comparisons regarding prevalence across studies difficult, particularly due to a lack of matched control groups. Limitations of the research impact on the reliability of current findings, which should therefore be interpreted with some caution.

King & Murphy (2014) reported the prevalence of autism amongst offender groups varied between 1 and 27%. Similarly, in the current review prevalence did vary considerably depending on study methodology and was limited by the use of biased samples recruited from prisons and secure mental health services. These limitations notwithstanding, the prevalence of autism in offending populations was estimated to be between 0.2 and 62.8% (studies 12 & 19).

In relation to the rather different question of the prevalence of offending within samples of autistic people, King & Murphy (2014) reported figures varied widely between 2.74 and 26%, although when reviewing studies that included a control group, results suggested autistic people committed the same number of offences or fewer offences than non-autistic people. In the current review, the prevalence of offending obtained from six samples of autistic people, was estimated to be between 0.7 and 5.7% (see Table 2). In England and Wales, the prison population as of March 2022 was 79,808 suggesting a prevalence of 0.1% (Ministry of Justice, 2022), although these figures underrepresent the number of people to encounter the CJS as suspects or offenders, excluding individuals in the community. Therefore, as concluded by King & Murphy (2014), when these rates are compared to the rates of offending amongst non-autistic people, the current evidence suggested autistic people may be no more likely than non-autistic people to engage in offending behaviour and encounter the CJS, although these findings should be interpreted with caution, given the limitations of the evidence base (i.e., unrepresentative, and biased samples, varying definitions of offending behaviour). Further, the lack of research on autistic females engaged in the CJS warrants further exploration. Such a small sample of autistic females recruited to some studies may, in part, provide some explanation for the variation in prevalence data. However, evidence continued to suggest autistic offenders engaged in a variety of offending behaviours, though the research remained biased in its focus on male autistic offenders and on violent and sexual offending with little consistency as to whether autistic people are more at risk of committing these types of offences.

As previously reported by King & Murphy (2014), comorbid psychiatric diagnoses continued to be common amongst autistic offenders, in particular ADHD, intellectual disabilities, psychosis, personality disorder and other affective disorders (e.g., 25). However, researchers have continued to recruit biased samples, predominantly from forensic psychiatric inpatient services, thus re-iterating the need for research into the prevalence of poor mental health, learning disabilities and other vulnerabilities, including autism as emphasised seven years ago in a report published by the Centre for Mental Health (Durcan et al., 2014).

Findings of the current review suggested that many characteristics associated with offending behaviour for autistic people are similar to those who are not autistic, including socio-demographic background, parental history, history of abuse, poor education attainment, lack of regular employment, and a history of aggression (e.g., studies 4, 7, 10, 29, 32, 37, 40, 47). However, some new findings have emerged since King & Murphy (2014), which have suggested that autistic offenders do have some unique characteristics that require consideration in service development and in their care and treatment. New characteristics that emerged from the current findings included evidence to suggest autistic offenders are less likely to have previous convictions related to drug offences, although they will sometimes misuse substances (e.g., study 9). Whilst few studies focused on identifying the motivations of autistic people who offend, it is suggested that some appear to be unique to this group of individuals and warrant further exploration (e.g., social misunderstandings, idiosyncratic explanations, social naiveté, and circumscribed interests; studies 7, 15 & 38), as King and Murphy also found.

More significantly, the current review highlighted new characteristics of autistic people in contact with the CJS in that they appear vulnerable to victimisation and abuse (e.g., study 4, 47), and are at increased risk of self-isolation and self-harm (e.g., 4 & 37). Further, research exploring the experiences of autistic people who encounter the CJS suggested more work is needed to address the lack of knowledge and awareness of autism amongst professionals working within the CJS (i.e., the police and prison staff). Research pertaining to judges and the court process was specifically lacking, with no studies identified that focused on these areas of the CJS. Further training is required to ensure autistic people are identified and provided with the appropriate support at all stages of the CJS. It is notable that in the UK, where the National Autistic Society accredit prisons that they consider the vulnerabilities of autistic people and their unique needs (e.g., sensory issues), unfortunately, only three of the 118 prisons in England and Wales, have received accreditation, which raises concerns about the support autistic offenders could expect to receive in a prison environment (Hughes, 2019).

Strengths and Limitations

The findings of the current review are limited by the relatively poor quality of included articles. Most studies used data retrieved from online questionnaires or file information from records and archives. Few articles collected primary data from autistic offenders. Although the current review sought to include global research on autistic offenders, the majority of research related to people in the UK and findings may therefore be unrepresentative of autistic people in other countries. Nevertheless, the current review has several strengths. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies, were reviewed, highlighting several gaps in our understanding of autistic offenders. Unlike King & Murphy (2014), an objective measure of the assessment of quality of all included articles was also utilised.

Implications for Policy, Practice, and Future Research

Since 2013, several policies and guidelines have emphasised the need to provide person-centred, and evidence-based support to autistic people who encounter the CJS in the UK and elsewhere. However, very little research has been conducted to evaluate their implementation. The current review suggested that further research needs to be conducted to provide a more accurate and reliable estimate of offending amongst autistic people. The few studies that focused on the experiences of autistic people in the CJS (e.g., 12, 31, 34) highlight the need for autism training for staff across the CJS, including police, prison staff, and judges. There is a need for increased recognition of autism, and increased support for autistic people in contact with CJS to improve care and treatment outcomes. Additionally, support needs to be in place for those with autism already in secure/custodial facilities to enable them to navigate the unpredictable environments and confusing social system within prison. In addition, more information and research on autistic people of other genders (e.g., female, non-binary) as well as ethnicities within the CJS are needed. Relevant strategies should be developed to ensure autistic people are identified and supported throughout all stages of the CJS. Professionals working within the criminal justice system should be trained on autism. Training should be evidence-based and empirically evaluated. The experiences of autistic people who encounter the CJS, as well as their carers should be sought and valued to ensure improvements to the care and treatment of autistic individuals in the CJS.

Conclusions

The current evidence base remains fraught with methodological limitations, with research conducted often using small unrepresentative samples. Nevertheless, findings suggested that autistic people do encounter the CJS as offenders, in addition to sometimes being victims of crime. In addition, autistic people appear largely comparable to non-autistic people, in terms of risk factors like social deprivation, though there was some evidence to suggest there are some unique characteristics which require careful consideration in the context of forensic care and treatment. Several policies and guidelines have been introduced to improve the care and treatment outcomes of autistic people in contact with the CJS but their implementation and effectiveness have not been sufficiently evaluated. Evidence suggested that autistic people have a range of vulnerabilities and require additional support, which appeared to be lacking in services where the experiences of autistic people have been examined.

References

Alexander, R. T., Chester, V., Green, F. N., Gunaratna, I., & Hoare, S. (2015). Arson or fire setting in offenders with intellectual disability: clinical characteristics, forensic histories, and treatment outcomes. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental disability, 40(2), 189–197. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2014.998182

American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

American Psychiatric Association, & American Psychiatric Association. (2013). DSM 5 (p. 70). American Psychiatric Association.

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Robinson, J., & Woodbury-Smith, M. (2005). The adult Asperger assessment (AAA): A diagnostic method. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(6), 807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-005-0026-5.

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J., & Clubley, E. (2001). The autism spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger’s syndrome/high functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005653411471.

Barry-Walsh, J. B., & Mullen, P. E. (2004). Forensic aspects of asperger’s syndrome. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 15(1), 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940310001638628.

Baxter, A. J., Brugha, T. S., Erskine, H. E., Scheurer, R. W., Vos, T., & Scott, J. G. (2015). The epidemiology and global burden of autism spectrum disorders. Psychological Medicine, 45(3), 601. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171400172X.

Billstedt, E., Anckarsäter, H., Wallinius, M., & Hofvander, B. (2017). Neurodevelopmental disorders in young violent offenders: Overlap and background characteristics. Psychiatry Research, 252, 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.03.004

Bleil Walters, J., Hughes, T. L., Sutton, L. R., Marshall, S. N., Crothers, L. M., Lehman, C., Huang, A. (2013). Maltreatment and depression in adolescent sexual offenders with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 22(1), 72–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2013.735357

Bosch, R., Chakhssi, F., & Hummelen, K. (2020). Inpatient aggression in forensic psychiatric patients with autism spectrum disorder: the role of risk and protective factors. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities and Offending Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIDOB-05-2019-0008

Bradley, K. (2009). The Bradley Report: Lord Bradley’s review of people with mental health problems or learning disabilities in the criminal justice system. London: Department of Health

Brewer, R. J., Davies, G. M., & Blackwood, N. J. (2016). Fitness to plead: The impact of autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice, 16(3), 182–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228932.2016.1177285.

Brookman-Frazee, L., Baker-Ericzén, M., Stahmer, A., Mandell, D., Haine, R. A., & Hough, R. L. (2009). Involvement of youths with autism spectrum disorders or intellectual disabilities in multiple public service systems. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 2(3), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315860902741542

Brugha, T. S., McManus, S., Bankart, J., Scott, F., Purdon, S., Smith, J., Bebbington, P., Jenkins, R., & Meltzer, H. (2011). Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders in adults in the community in England. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(5), 459–465. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.38.

Brugha, T. S., Spiers, N., Bankart, J., Cooper, S. A., McManus, S., Scott, F. J., Smith, J., Tyrer, F. (2016). Epidemiology of autism in adults across age groups and ability levels. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(6), 498–503. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.115.174649

Buitelaar, N. J., & Ferdinand, R. F. (2016). ADHD undetected in criminal adults. Journal of Attention Disorders, 20(3), 270–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054712466916.

Care Act. (2014). Chapter 23. London: The Stationery Office

Care Quality Commission (2020). Out of sight-who cares?A review of restraint, seclusion and segration for autistic people, and people with a learning disability and/or mental health condition. https://www.cqc.org.uk/publications/themed-work/rssreview

Cheely, C. A., Carpenter, L. A., Letourneau, E. J., Nicholas, J. S., Charles, J., & King, L. B. (2012). The prevalence of youth with autism spectrum disorder in the criminal justice system. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(9), 1856–1862. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1427-2.

Chiarotti, F., & Venerosi, A. (2020). Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders: A review of worldwide prevalence estimates since 2014. Brain sciences, 10(5), 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10050274

Crane, L., Maras, K. L., Hawken, T., Mulcahy, S., & Memon, A. (2016). Experiences of autism spectrum disorder and policing in England and Wales: Surveying police and the autism community. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(6), 2028–2041. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2729-1

Durcan, G., Saunders, A., Gadsby, B., & Hazard, A. (2014). The Bradley report five years on. London, England: Centre for Mental Health.

de la Gomez, G. (2010). A selective review of offending behaviour in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Learning Disabilities and Offending Behaviour, 1, 47–58. https://doi.org/10.5042/jldob.2010.0419.

Esan, F., Chester, V., Gunaratna, I. J., Hoare, S., & Alexander, R. T. (2015). The clinical, forensic and treatment outcome factors of patients with autism spectrum disorder treated in a forensic intellectual disability service. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 28(3), 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12121.

Farrington, D. P. (2019). The duration of criminal careers: How many offenders do not desist up to age 61? Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 5(1), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-018-0098-5

Farrington, D. P., Gundry, G., & West, D. J. (1975). The familial transmission of criminality. Medicine, Science and the Law, 15(3), 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/002580247501500306

Farrington, D. P., & Hawkins, J. D. (1991). Predicting participation, early onset and later persistence in officially recorded offending. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 1(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.1991.1.1.1

Farrington, D. P., Jolliffe, D., & Coid, J. W. (2021). Cohort profile: The Cambridge study in delinquent development (CSDD). Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 7, 278–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-021-00162-y.

Gibbs, V., & Haas, K. (2020). Interactions between the police and the autistic community in Australia: Experiences and perspectives of autistic adults and parents/careers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(12), 4513–4526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04510-7.

Gillberg, C., Gillberg, C., Råstam, M., & Wentz, E. (2001). The asperger syndrome (and high-functioning autism) diagnostic interview (ASDI): A preliminary study of a new structured clinical interview. Autism, 5(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361301005001006.

Girardi, A., Hancock-Johnson, E., Thomas, C., & Wallang, P. M. (2019). Assessing the risk of inpatient violence in autism spectrum disorder. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 47(4), 427–436.

Glover, G., & Brown, I. (2015). People with intellectual disabilities hospitalised by courts in England. Tizard Learning Disability Review, 20(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1108/TLDR-10-2014-0034

Gomes, V., Jardim, P., Taveira, F., Dinis-Oliveira, R. J., & Magalhães, T. (2014). Alleged biological father incest: A forensic approach. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 59(1), 255–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12310.

Griffiths, C., Roychowdhury, A., & Girardi, A. (2018). Seclusion: the association with diagnosis, gender, length of stay and HoNOS-secure in low and medium secure inpatient mental health service. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 29(4), 656–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2018.1432674

H.R.1058 - 116th Congress. (2019–2020). Autism Collaboration, Accountability, Research, Education, and Support Act (CARES) of 2019. http://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1058

Hansson, S. L., Svanströmröjvall, A., Rastam, M., Gillberg, C., Gillberg, C., & Anckarsäter, H. (2005). Psychiatric telephone interview with parents for screening of childhood autism–tics, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and other comorbidities (A-TAC): Preliminary reliability and validity. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 187(3), 262–267. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.187.3.262

Haw, C., Radley, J., & Cooke, L. (2013). Characteristics of male autistic spectrum patients in low security: Are they different from non-autistic low secure patients? Journal of Intellectual Disabilities and Offending Behaviour, 4(1–2), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIDOB-03-2013-0006

Heeramun, R., Magnusson, C., Gumpert, C. H., Granath, S., Lundberg, M., Dalman, C., & Rai, D. (2017). Autism and convictions for violent crimes: Population-based cohort study in Sweden. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(6), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.011.

Helverschou, S. B., Rasmussen, K., Steindal, K., Søndanaa, E., Nilsson, B., & Nøttestad, J. A. (2015). Offending profiles of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A study of all individuals with autism spectrum disorder examined by the forensic psychiatric service in Norway between 2000 and 2010. Autism, 19(7), 850–858. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315584571

Helverschou, S. B., Steindal, K., Nøttestad, J. A., & Howlin, P. (2018). Personal experiences of the criminal justice system by individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 22(4), 460–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316685554

Hill, S. A., Ferreira, J., Chamorro, V., & Hosking, A. (2019). Characteristics and personality profiles of first 100 patients admitted to a secure forensic adolescent hospital. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 30(2), 352–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2018.1547416.

Hippler, K., Viding, E., Klicpera, C., & Happe, F. (2010). No increase in criminal convictions in Hans Asperger’s original cohort. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 774–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0917-y.

Hofvander, B., Bering, S., Tärnhäll, A., Wallinius, M., & Billstedt, E. (2019). Few differences in the externalizing and criminal history of young violent offenders with and without autism spectrum disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 911. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00911.

Home Office. (2018). Police and criminal evidence act (1984) code of practice (PACE), code C, for the detention, treatment and questioning by police officers. London: The Stationery Office.

Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221.

Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M-C., Vedel, I. (2019). Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: a modified e-Delphi study. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 111, 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.008

Hughes, C. (2019). Supporting autistic people in prison and probation services. National Autistic Society. Retrieved May 10, 2019, from https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/professional-practice/prison-probation

Jamel, J. (2008). Crime and its causes. In G. Davies, C. Hollin, & R. Bull (Eds.), Forensic psychology (p.4). West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

King, C., & Murphy, G. (2014). A systematic review of people with autism spectrum disorder and the criminal justice system. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 2717–2733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2046-5.

Knobloch, K., Yoon, U., & Vogt, P. M. (2011). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement and publication bias. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery, 39(2), 91–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2010.11.001

Långström, N., Grann, M., Ruchkin, V., Sjöstedt, G., & Fazel, S. (2008). Risk factors for violent offending in autism spectrum disorder: a national study of hospitalized individuals. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(8), 1358–1370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508322195

Larson, T., Anckarsäter, H., Gillberg, C., Ståhlberg, O., Carlström, E., Kadesjö, B., Råstam, M., Lichtenstein, P., & Gillberg, C. (2010). The autism-tics, AD/HD and other comorbidities inventory (A-TAC): Further validation of a telephone interview for epidemiological research. BMC Psychiatry, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-1

Lewis, A., Pritchett, R., Hughes, C., & Turner, K. (2015). Development and implementation of autism standards for prisons. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities and Offending Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIDOB-05-2015-0013

Lindblad, F., & Lainpelto, K. (2011). Sexual abuse allegations by children with neuropsychiatric disorders. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 20(2), 182–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2011.554339.

Lindsay, W. R., Carson, D., O’Brien, G., Holland, A. J., Taylor, J. L., Wheeler, J. R., & Steptoe, L. (2014). A comparison of referrals with and without autism spectrum disorder to forensic intellectual disability services. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 21(6), 947–954. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2014.918081.

Lord, C., Luyster, R. J., Gotham, K., & Guthrie, W. (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule, second edition (ADOS-2) manual (part II): Toddler module. Western Psychological Services. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1698-3_2011.

Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook, E. H., Leventhal, B. L., DiLavore, P. C., Pickles, A., & Rutter, M. (2000). The autism diagnostic observation schedule—Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(3), 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005592401947.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (1994). Autism diagnostic interview-revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24(5), 659–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02172145.

Loureiro, D., Machado, A., Silva, T., Veigas, T., Ramalheira, C., & Cerejeira, J. (2018). Higher autistic traits among criminals, but no link to psychopathy: Findings from a high-security prison in Portugal. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(9), 3010–3020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3576-z.

Lundstrom, S., Forsman, M., Larsson, H., Kerekes, N., Serlachius, E., Langstrom, N., & Lichtenstein, P. (2014). Childhood neurodevelopmental disorders and violent criminality: A sibling control study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 2707–2716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1873-0.

Maras, K. L., Crane, L., Mulcahy, S., Hawken, T., Cooper, P., Wurtzel, D., & Memon, A. (2017). Brief report: Autism in the courtroom: Experiences of legal professionals and the autism community. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(8), 2610–2620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3162-9

Ministry of Justice. (2022). Official statistics: Prison population figures: 2022. Retrieved May 10, from https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/prison-population-figures-2022#full-publication-update-history

Mouridsen, S. E., Rich, B., Isager, T., & Nedergaard, N. J. (2008). Pervasive developmental disorders and criminal behaviour: A case control study. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 52(2), 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X07302056.

Murphy, D. (2014). Self-reported anger among individuals with an autism spectrum disorder detained in high security psychiatric care: Do preoccupations have an influence? The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 25(1), 100–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2013.862291.

Murphy, D., Bush, E. L., & Puzzo, I. (2017). Incompatibilities and seclusion of patients with an autism spectrum disorder detained in high-secure psychiatric care. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities and Offending Behaviour, 8(4), 188–200. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIDOB-05-2017-0007

Myles, B. S., Simpson, R. L., & Bock, S. J. (2001). Asperger syndrome diagnostic scale. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2016). Autism spectrum disorder in adults: diagnosis and management (pp. 1–44). Clinical guideline. CG142. Retrieved May 10, 2019, from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg142/chapter/Update-information

Newman, C., Cashin, A., & Graham, I. (2019). Identification of service development needs for incarcerated adults with autism spectrum disorders in an Australian prison system. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 15, 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPH-11-2017-0051.

Newman, C., Cashin, A., & Waters, C. (2015). A hermeneutic phenomenological examination of the lived experience of incarceration for those with autism. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(8), 632–640. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2015.1014587

NHS England. (2015a). Building the right support. A national plan to develop community services and close inpatients facilities for people with learning disabilities and/or autism who display behaviour that challenges, including those with a mental health condition. Retrieved May 10, 2019, from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/ld-nat-imp-plan-oct15.pdf

NHS England. (2015b). Transforming Care for people with learning disabilities – next steps. Retrieved May 10, 2019, from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/transform-care-nxt-stps.pdf

NHS England. (2019). Beyond the high fence. Retrieved May 10, 2019, from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/beyond-the-high-fence.pdf

NHS England & NHS Improvement. (2019). Liaison and diversion standard service specification 2019. The National Liaison and Diversion Programme, NHS England & Improvement. Retrieved May 10, 2019, from national-liaison-and-diversion-service-specification-2019.pdf (england.nhs.uk)

O’Donoghue, T., Shine, J., & Orimalade, O. (2014). Characteristics of referrals and admissions to a medium secure ASD unit. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities and Offending Behaviour, 5(3), 138. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIDOB-06-2014-0008

Payne, K. L., Maras, K. L., Russell, A. J., & Brosnan, M. J. (2020). Are mental health, family and childhood adversity, substance use and conduct problems risk factors for offending in autism? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04622-0.

Payne, K. L., Maras, K., Russell, A. J., & Brosnan, M. J. (2020). Self-reported motivations for offending by autistic sexual offenders. Autism, 24(2), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319858860

Pérez-Crespo, L., Prats-Uribe, A., Tobias, A., Duran-Tauleria, E., Coronado, R., Hervás, A., & Guxens, M. (2019). Temporal and geographical variability of prevalence and incidence of autism spectrum disorder diagnoses in children in Catalonia, Spain. Autism Research, 12, 1693–1705. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2172.

Rava, J., Shattuck, P., Rast, J., & Roux, A. (2017). The prevalence and correlates of involvement in the criminal justice system among youth on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 340–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2958-3

Rutter, M., Bailey, A., & Lord, C. (2003). Social communication questionnaire. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services

Salerno, A. C., & Schuller, R. A. (2019). A mixed-methods study of police experiences of adults with autism spectrum disorder in Canada. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 64, 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2019.01.002.

Salerno-Ferraro, A. C., & Schuller, R. A. (2020). Perspectives from the ASD community on police interactions: Challenges & recommendations. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 105, 103732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103732

Sheridan, L., & Pyszora, N. (2018). Fixations on the police: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 5(2), 63. https://doi.org/10.1037/tam0000100

Siponmaa, L., Kristiansson, M., Jonson, C., Nyden, A., & Gillberg, C. (2001). Juvenile and young mentally disordered offenders: The role of child neuropsychiatric disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 29, 420–426.

Skonieczna-Zydecka, K., Gorzkowska, I., Pierzak-Sominka, J., & Adler, G. (2017). The prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in west pomeranian and pomeranian regions of Poland. Journal Applied Research Intellectual Disabilities, 30, 283–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12238.

Slaughter, A. M., Hein, S., Hong, J. H., Mire, S. S., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2019). Criminal behaviour and school discipline in juvenile justice-involved youth with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 2268–2280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03883-8.

Smith, M. C. (2021). Causes and consequences of delayed diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in forensic practice: a case series. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities and Offending Behaviour, 12(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIDOB-10-2020-0017

Søndenaa, E., Helverschou, S. B., Steindal, K., Rasmussen, K., Nilsson, B., & Nøttestad, J. A. (2014). Violence and sexual offending behavior in people with autism spectrum disorder who have undergone a psychiatric forensic examination. Psychological Reports, 115(1), 32–43. https://doi.org/10.2466/16.15.PR0.115c16z5

Stokes, M., Newton, N., & Kaur, A. (2007). Stalking, and social and romantic functioning among adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(10), 1969–1986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0344-2.

Sturup, J. (2018). Comparing serial homicides to single homicides: A study of prevalence, offender, and offence characteristics in Sweden. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offenders Profiling, 15(2), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1500.

Sutton, L. R., Hughes, T. L., Huang, A., Lehman, C., Paserba, D., Talkington, V., & Marshall, S. (2013). Identifying individuals with autism in a state facility for adolescents adjudicated as sexual offenders: A pilot study. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 28(3), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357612462060

Tint, A., Palucka, A. M., Bradley, E., Weiss, J. A., & Lunsky, Y. (2017). Correlates of police involvement among adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(9), 2639–2647. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3182-5

Turner, K., Lewis, A., Hughes, C., & Foster, M. (2016). Improving the management of prisoners with autistic spectrum disorders (ASD). Prison Service Journal, 226, 22–26

Van den Bogaard, K. J. H. M., Embregts, P. J. C. M., Hendriks, A. H. C., & Heestermans, M. (2013). Comparison of intellectually disabled offenders with a combined history of sexual offenses and other offenses versus intellectually disabled offenders without a history of sexual offenses on dynamic client and environmental factors. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(10), 3226–3234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2013.06.027.

van Wijk, A., Hardeman, M., & Endenburg, N. (2018). Animal abuse: Offender and offence characteristics. A descriptive study. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 15(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1499

Vinter, L. P., Dillon, G., & Winder, B. (2020). ‘People don’t like you when you’re different’: Exploring the prison experiences of autistic individuals. Psychology, Crime & Law. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2020.1781119

Walker, J. S. (2005). The Maudsley Violence Questionnaire: Initial validation and reliability. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(1), 187–201. Retrieved May 10, 2019, from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.04.001

Weiss, J. A., & Fardella, M. A. (2018). Victimization and perpetration experiences of adults with autism. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 203. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00203.

White, S. G., Meloy, J. R., Mohandie, K., & Kienlen, K. (2017). Autism spectrum disorder and violence: Threat assessment issues. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 4(3), 144. https://doi.org/10.1037/tam0000089

Widinghoff, C., Berge, J., Wallinius, M., Billstedt, E., Hofvander, B., & Håkansson, A. (2019). Gambling disorder in male violent offenders in the prison system: Psychiatric and substance-related comorbidity. Journal of Gambling Studies, 35(2), 485–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-9785-8.

Williams, F., Warwick, M., McKay, C., Macleod, C., & Connolly, M. (2020). Learning disability, autism and the criminal procedure (Scotland) act. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities, 14(5), 149–167. https://doi.org/10.1108/AMHID-09-2019-0028.

Wing, L., & Gould, J. (1979). Severe impairments of social interaction and associated abnormalities in children. Epidemiology and classification. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 9, 11–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01531288.

Wing, L., Leekam, S. R., Libby, S. J., Gould, J., & Larcombe, M. (2002). The diagnostic interview for social and communication disorders: Background, inter-rater reliability and clinical use. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(3), 307–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00023.

Woodbury-Smith, M. R., Clare, I. C. H., Holland, A. J., & Kearns, A. (2006). High functioning autistic spectrum disorders, offending and other law-breaking: Findings from a community sample. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 17(1), 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940600589464.

Woodbury-Smith, M., Clare, I., Holland, A. J., Watson, P. C., Bambrick, M., Kearns, A., & Staufenberg, E. (2010). Circumscribed interests and ‘offenders’ with austism spectrum disorders: A case-control study. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 21(3), 366–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940903426877

World Health Organization. (1992). The ICD-10 classifications of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: WHO.

World Health Organization. (2019). The ICD-10 classifications of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: WHO.

Young, S., González, R. A., Mullens, H., Mutch, L., Malet-Lambert, I., & Gudjonsson, G. H. (2018). Neurodevelopmental disorders in prison inmates: Comorbidity and combined associations with psychiatric symptoms and behavioural disturbance. Psychiatry Research, 261, 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.036.

Yu, Y., Bradley, C. C., Boan, A. D., Charles, J. M., & Carpenter, L. A. (2021). Young adults with autism spectrum disorder and the criminal justice system. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04805-9.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations